Background on James Edmund Groppi v. State of Wisconsin

Press Release

December 3, 1970

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. Background on James Edmund Groppi v. State of Wisconsin, 1970. 46e69b52-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0ed0d62d-78ca-4382-b53c-5c6f27c7f5f8/background-on-james-edmund-groppi-v-state-of-wisconsin. Accessed February 12, 2026.

Copied!

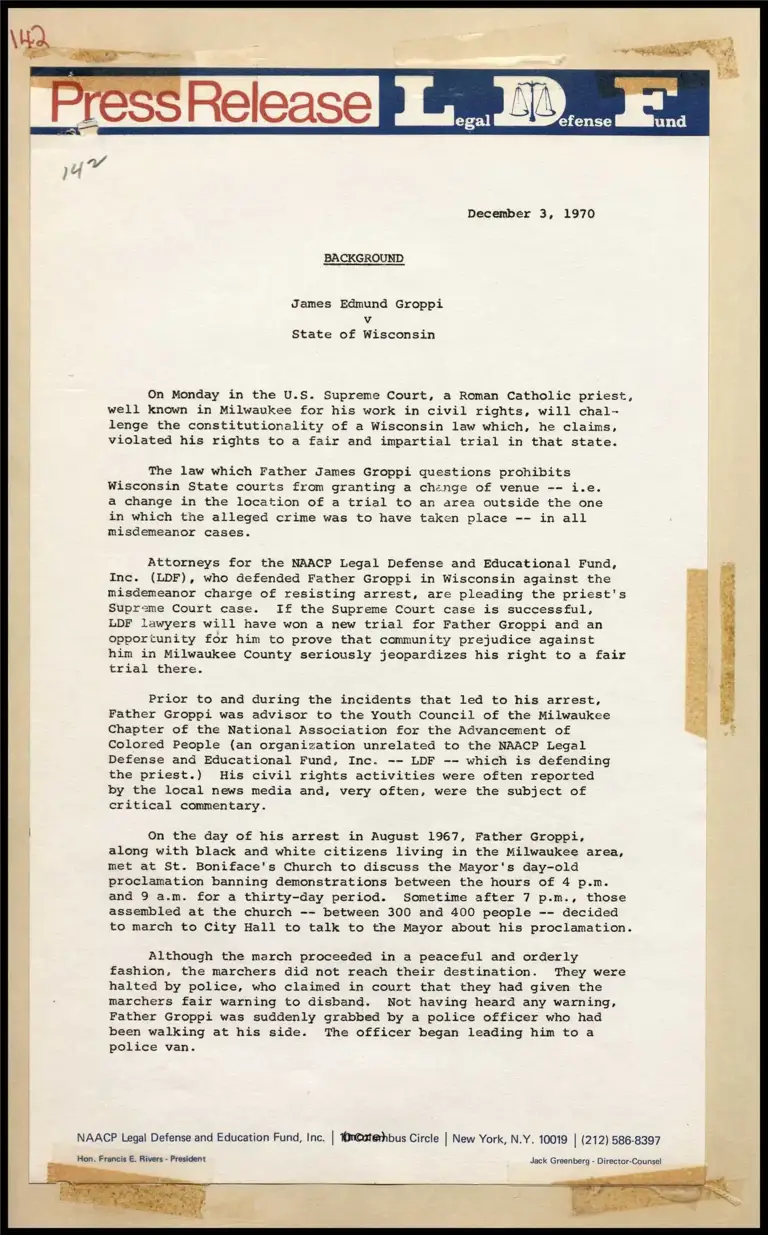

Release ® & ae ae

December 3, 1970

BACKGROUND

James Edmund Groppi

v

State of Wisconsin

On Monday in the U.S. Supreme Court, a Roman Catholic priest,

well known in Milwaukee for his work in civil rights, will chal-

lenge the constitutionality of a Wisconsin law which, he claims,

violated his rights to a fair and impartial trial in that state.

The law which Father James Groppi questions prohibits

Wisconsin State courts from granting a chenge of venue -- i.e.

a change in the location of a trial to an area outside the one

in which the alleged crime was to have taken place -- in all

misdemeanor cases.

Attorneys for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (LDF), who defended Father Groppi in Wisconsin against the

misdemeanor charge of resisting arrest, are pleading the priest's

Supreme Court case. If the Supreme Court case is successful,

LDF lawyers wiil have won a new trial for Father Groppi and an

opportunity for him to prove that community prejudice against

him in Milwaukee County seriously jeopardizes his right to a fair

trial there.

Prior to and during the incidents that led to his arrest,

Father Groppi was advisor to the Youth Council of the Milwaukee

Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People (an organization unrelated to the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. -- LDF -- which is defending

the priest.) His civil rights activities were often reported

by the local news media and, very often, were the subject of

critical commentary.

} On the day of his arrest in August 1967, Father Groppi,

along with black and white citizens living in the Milwaukee area,

met at St. Boniface's Church to discuss the Mayor's day-old

proclamation banning demonstrations between the hours of 4 p.m.

and 9 a.m. for a thirty-day period. Sometime after 7 p.m., those

assembled at the church -- between 300 and 400 people -- decided

to march to City Hall to talk to the Mayor about his proclamation.

Although the march proceeded in a peaceful and orderly

fashion, the marchers did not reach their destination. They were

halted by police, who claimed in court that they had given the

marchers fair warning to disband. Not having heard any warning,

Father Groppi was suddenly grabbed by a police officer who had

been walking at his side. The officer began leading him to a

police van.

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | Wor@aterhbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

Hon. Francis E. Rivers - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

oe

The priest went limp and two other officers were called in to

assist in carrying him to the wagon. What ensued laid the basis

for the charge of resisting arrest.

While he was being carried to the van by the three officers,

one at his head and one holding each leg, Father Groppi began

kicking his feet in a motion similar to pedaling a bicycle. At

his trial, the three officers testified that he hollered to the

policeman holding his left leg -- Officer Buchanan -- to let go

of it and that he used profanity. They further testified that

one of the priest's kicks caught Buchanan in the chest and sent

him down on one knee.

Several marchers and news reporters who were in the vicinity

of the incident testified that they heard no such profanity nor

did they see Officer Buchanan get kicked or fall to one knee.

Father Groppi, who maintains his innocence, claims that all

during the time he was being carried, Officer Buchanan had been

digging his fingernails into his foot: that his kicking was

only an attempt to wiggle his foot free of Buchanan's hold. Some

of the defense witnesses bore out the priest's story saying that

they heard Father Groppi complaining about the gouging of his

foot while he was being carried.

The priest also testified that none of the officers who

carried him to the van would give him information on Buchanan's

identity. Noticing that Buchanan wasn't wearing a badge during

the arrest, Groppi had asked for his name. One of the other

officers replied, "that if for you to find out."

Father Groppi, who was convicted by a Milwaukee jury of

resisting arrest, was given a six months suspended sentence,

placed on two years probation, and fined $500 plus court costs.

An additional six months sentence would have to be served, the

court said, if the priest did not pay the fine within 24 hours.

The Supreme Court of Wisconsin later affirmed the conviction and

the sentence.

Several times during his court ordeal, Father Groppi

requested that the location of the trial be moved to another

county, claiming that local prejudices precluded his getting a

fair trial there. The lower court and the Wisconsin Supreme Court

continually denied him a change of venue, quoting State law which

prohibited their granting his request.

In the U.S. Supreme Court, LDF attorneys will contend that

no matter how great or small the charges against Father Groppi,

and regardless of whether there is sufficient local prejudice to

warrant granting him a change of venue in Wisconsin, the State

law which flatly denies any criminal defendant his right to an

impartial jury violates the Sixth Amendment and the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment.

=30=