Wiggins v. Haynes Opinion

Public Court Documents

September 2, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wiggins v. Haynes Opinion, 1970. c4460c17-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0ed5faa5-c33f-4181-b7ea-d419e1d47769/wiggins-v-haynes-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

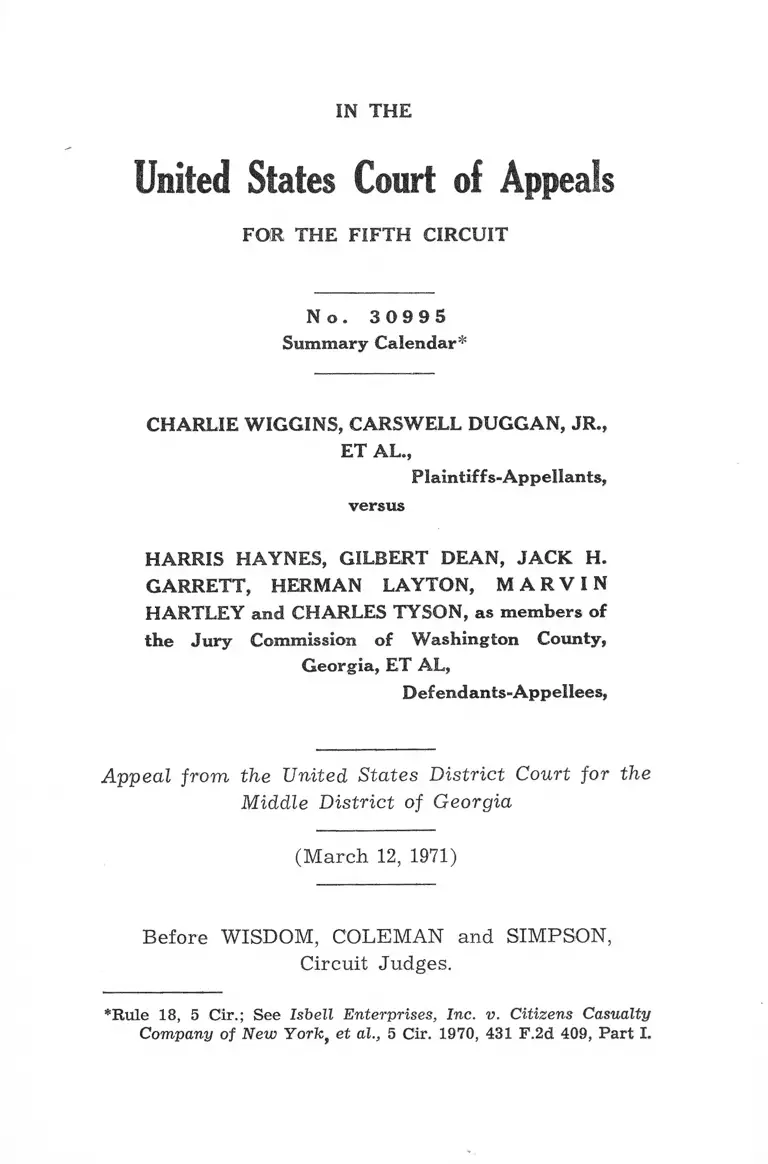

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 3 0 9 9 5

Summary Calendar*

CHARLIE WIGGINS, CARSWELL DUGGAN, JR.,

ET AL.,

P laintif f s-Appellants,

versus

HARRIS HAYNES, GILBERT DEAN, JACK H.

GARRETT, HERMAN LAYTON, M A R V I N

HARTLEY and CHARLES TYSON, as members of

the Jury Commission of Washington County,

Georgia, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Georgia

(March 12, 1971)

Before WISDOM, COLEMAN and SIMPSON,

Circuit Judges.

*Rule 18, 5 Cir.; See Isbell Enterprises, Inc. v. Citizens Casualty

Company of New Yorkf et al., 5 Cir. 1970, 431 F.2d 409, Part I.

2 WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL

PER CURIAM: Plaintiffs-appellants brought this

action in the district court alleging racial discrimina

tion in the composition of the grand and traverse jury

lists for Washington County, Georgia, and in the ab

sence of Negro jury commissioners for the county. The

district court, noting changes made by the county in

the selection of jury commissioners and compilation

of jury lists subsequent to the filing of the suit but

prior to the ruling of the court, concluded in an opinion

dated September 2, 1970, that the defendants had not

discriminated on the basis of race. (See Appendix A).

Accordingly, the district court denied the prayers for

relief. We have examined the briefs and the record

and have determined that the evidence supports the

findings and conclusions of the district court.

AFFIRMED.

APPENDIX A

(Style and number omitted)

BOTTLE, Chief Judge:

In this class action the plaintiffs attack the jury lists

and the method of selecting jurors and the method

of naming jury commissioners in Washington County,

Georgia. The five first named defendants were jury

commissioners at the time the complaint was filed.

Since then the Judge of the Superior Court has named

a new commission of six members and they have been

substituted as parties defendants as follows: Harris

WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL 3

Haynes, Gilbert Dean, Jack H. Garrett, Herman Lay-

ton, Marvin Hartley and Charles Tyson.

Count One attacks specifically the jury lists and al

leges that the failure of the defendants to enroll plain

tiffs and the members of their class on the jury lists

“is the result of the deliberate and systematic exclu

sion and limitation by defendants of the number of

Negro citizens resident in Washington County who are

called for service on juries.”

Count Two attacks specifically the composition of

the jury commission and alleges that plaintiffs and

their class have never been named to the commission

“because of the pattern and practice of racial exclu

sion and segregation of blacks in Washington County,

Georgia, including the entire process of jury selec

tion,” and alleges further that within memory the

Judges of the Superior Court of Washington County,

Georgia have never appointed a black person to serve

on the commission.

The prayers are, in substance, that the jury com

mission be dissolved; that the Superior Court Judge

be required to appoint plaintiffs and members of their

class as members of a new jury commission; and that

the present jury lists be dissolved and new jury lists

be compiled.

Shortly after this suit was filed the Supreme Court

decided Turner v. F ouche,____U. S ._____ , 24 L. ed

2d 567 (1970), which disposes of Count Two of the com

plaint by holding that a mere failure to appoint black

commissioners in the past does not establish discrim-

4 WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL

illation and would certainly constitute no justification

for federal courts’ instructing a state court to make

such appointments even assuming that under any cir

cumstances a state court judge’s discretion could be

so controlled. The evidence in this case fails to show

any intentional discrimination in the matter of appoint

ment of jury commissioners. Indeed, it so happens that

in appointing a new commission shortly after this suit

was filed the Judge of the Superior Court named to

that commission two black members and four white

members.

The pertinent facts with respect to this jury selection

process are as follows: According to the 1960 census

blacks constitute 49.5 per cent of the adult population

of the county. After the filing of this suit the Judge

of the Superior Court inquired as to the number

of names on the registered voters’ list used in the last

preceding general election, this being the list which

commissioners are required to use in compiling jury

lists, Ga. Code Ann. 59-106, and was informed that this

list contained 3,417 black voters and 5,789 white voters,

the percentage of black being 37. He learned also that

in the last jury revision the old list of names obtained

from the tax digest had been retained and simply sup

plemented by new names from the registered voters’

list, and he knew therefore that under the holding of

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U. S. 545, 17 L. ed 2d 599 (1967)

a new jury list had to be compiled. Accordingly, he

appointed the new commission and this commission

immediately went to work in compiling a new list. They

held six or eight meetings as a body and worked on

their task on the following days: January 13, 29, Feb

WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL 5

ruary 16, 17, 18, 20, 23, 24, 25, 27, March 2, 3, 4, 6, 9, 10,

and 17, 1970. At the beginning of their work they were

instructed by the Judge of the Superior Court who

read to them the appropriate statutes including Ga.

Code Ann. 59-106, which reads as follows:

“Revision of jury lists. Selection of Grand

and traverse jurors: ■— At least biennially

or, if the judge of the superior court shall di

rect, at least annually, on the first Monday in

August, or within 60 days thereafter, the board

of jury commissioners shall compile and main

tain and revise a jury list of intelligent and up

right citizens of the county to serve as jurors.

In composing such list the commissioners shall

select a fairly representative cross-section of

the intelligent and upright citizens of the coun

ty from the official registered voters’ list

which was used in the last preceding general

election. If at any time it appears to the jury

commissioners that the jury list, so composed,

is not a fairly representative cross-section of

the intelligent and upright citizens of the coun

ty, they shall supplement such list by going

out into the county and personally acquainting

themselves with other citizens of the county,

including intelligent and upright citizens of any

significantly identifiable group in the county

which may not be fairly representative there

on.

“After selecting the citizens to serve as jur

ors, the jury commissioners shall select from

the jury list a sufficient number of the most ex

6 WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL

perienced, intelligent and upright citizens, not

exceeding two-fifths of the whole number, to

serve as grand jurors. The entire number first

selected, including those afterwards selected

as grand jurors, shall constitute the body of

traverse jurors for the county, except as other

wise provided herein, and no new names shall

be added until those names originally selected

have been completely exhausted, except when

a name which has already been drawn for the

same term as a grand juror shall also be drawn

as a traverse juror, such name shall be re

turned to the box and another drawn in its

stead.”

He explained to them that in the selection of jurors

they were not restricted to the voters’ list but could

use such references as telephone books and R.E.A.

lists. He explained also that there were some Men-

nonites in the county who, according to his informa

tion, did not register to vote. He provided for each

of the six commissioners a complete copy of the old

voters’ list. He did not pass on to them his informa

tion as to the white and black ratio on the voters’ lists.

These lists incidentally contained no racial identifica

tion or any other identification with respect to any

voter, simply his or her name and the Georgia militia

district in which he or she resided, there being 21 of

such districts. Bach district was assigned to one or

more commissioners who studied the voters’ list with

respect to said district and prepared and submitted

to the entire commission proposed names from such

d i s t r i c t . The Commissioners confined themselves

WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL 7

pretty largely to the voters’ list although some names,

perhaps a dozen about equally white and black, were

selected from other sources. On one occasion the com

missioners inquired of the Judge whether or not they

were to work on a percentage basis as to white and

black and the statute was again read to them, Ga.

Code Ann. 59-106, and it was observed that the statute

does not require percentages. They were told that they

were to work for a fairly representative cross-section

of the intelligent and upright citizens of the county.

They undertook to do the best job they could under

the mandate of this code section. They were told by

the Judge to comprise a list of approximately 800 jur

ors which was estimated to be sufficient to last until

or through August, 1971, when the next revision is con

templated. When the commission finished its work they

had comprised a list of traverse jurors, 562 white and

206 black. From that traverse list they proceeded in

accordance with the code section to compile a grand

jury list of 221 white and 70 black. Thus on the traverse

list blacks represent 26% and on the grand jury list

they represent 24%. In compiling this jury list the com

missioners were not concerned primarily, if at all, with

racial percentages. Indeed, they did not know the per

centage of whites and blacks on the list when it was

completed and did not ascertain those figures until

counsel for the defendants after a pre-trial conference

in this case called upon them for that information.

Then, for the first time, it was computed with the re

sults above stated — traverse jury 26% black, grand

jury 24% black.

Significantly, some jurors, both traverse and grand,

8 WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL

were obtained from each of the 21 districts. The per

centages of blacks per district range from a high of

55% in Strange District to a low of 0% in a few districts

in which there are no black residents. The largest dis

trict is Sandersville which furnished 176 white and 96

black traverse jurors, the black percentage here being

36%.

If there were no evidence in this case except the

1960 census figures indicating a black population avail

ability of 49.5% and a traverse jury black representa

tion of 26% one might readily suspect discrimination.

In view of all the facts as above found, however, this

court finds as a fact that there was no racial discrim

ination. It has long been settled that “neither the jury

roll nor the venire need be a perfect mirror of the

community or accurately reflect the proportionate

strength of every identifiable group.” Swain v. Ala

bama, 380 U. S. 202, 208, 13 L. ed 2d 759, 766 (1965).

It is, indeed, “impossible to meet a requirement of

proportionate representation.” Idem. In Carter v.

Greene County, ____ U. S. ____ , 24 L. ed 2d 549, 564,

Mr. Justice Douglas, dissenting in part, said: “Jury

selection is largely by chance; . . . . The law only re

quires that the panel not be purposefully unrepresen

tative” and quoted with approval a Washington Post

editorial in part as follows: “Quotas are understand

ably abhorrent to those seeking to do away with dis

crimination.” Thus the Superior Court Judge in the

case at bar correctly advised the commissioners that

they were not required to work on a percentage basis

and that they were, in the words of the statute, to “se

lect a fairly representative cross-section of the intelli

WIGGINS, ET AL v. HAYNES, ET AL 9

gent and upright citizens of the county.” The statute’s

requirement that citizens be “intelligent and upright

citizens” in order to be eligible for jury service was

sanctioned and approved by the Supreme Court in Car

ter v. Greene County, supra. See also Turner v.

Fouche, supra. The evidence fails to disclose that black

citizens were in any manner discriminated against by

the commissioners in the application of these require

ments.

Accordingly, all prayers of the complaint are denied

and counsel for the defendants may prepare an appro

priate judgment and present the same after affording

counsel for the plaintiffs an opportunity for suggestions

as to form.

This 2nd day of September, 1970.

(Signed) W. A. BOOTLE

CHIEF JUDGE

This is to certify that I have this date mailed a copy

of the within to Mr. Thomas M. Jackson, 655 New

Street, Macon, Go. 31201; to Mr. Jack Greenberg, Mr.

Norman Amaker, 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New

York 10019; to Mr. Howard Moore, Jr., Mr. Peter E.

Rindskopf, Suite 1154 Citizens Trust Company Bank

Bldg., Atlanta, Ga. 30314; to Mr. Denmark Groover,

Jr., P. O. Box 755, Macon, Ga. 31202;

This 2nd day of September, 1970.

(Signed) DOROTHY F. MOTES

Dorothy F. Motes

Deputy Clerk

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts—Scofields’ Quality Printers, Inc., N. O., La.