Edwards v. South Carolina Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Edwards v. South Carolina Appellants' Brief, 1961. fe16bf92-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0ef772fe-e130-4204-af89-305dad18891b/edwards-v-south-carolina-appellants-brief. Accessed February 18, 2026.

Copied!

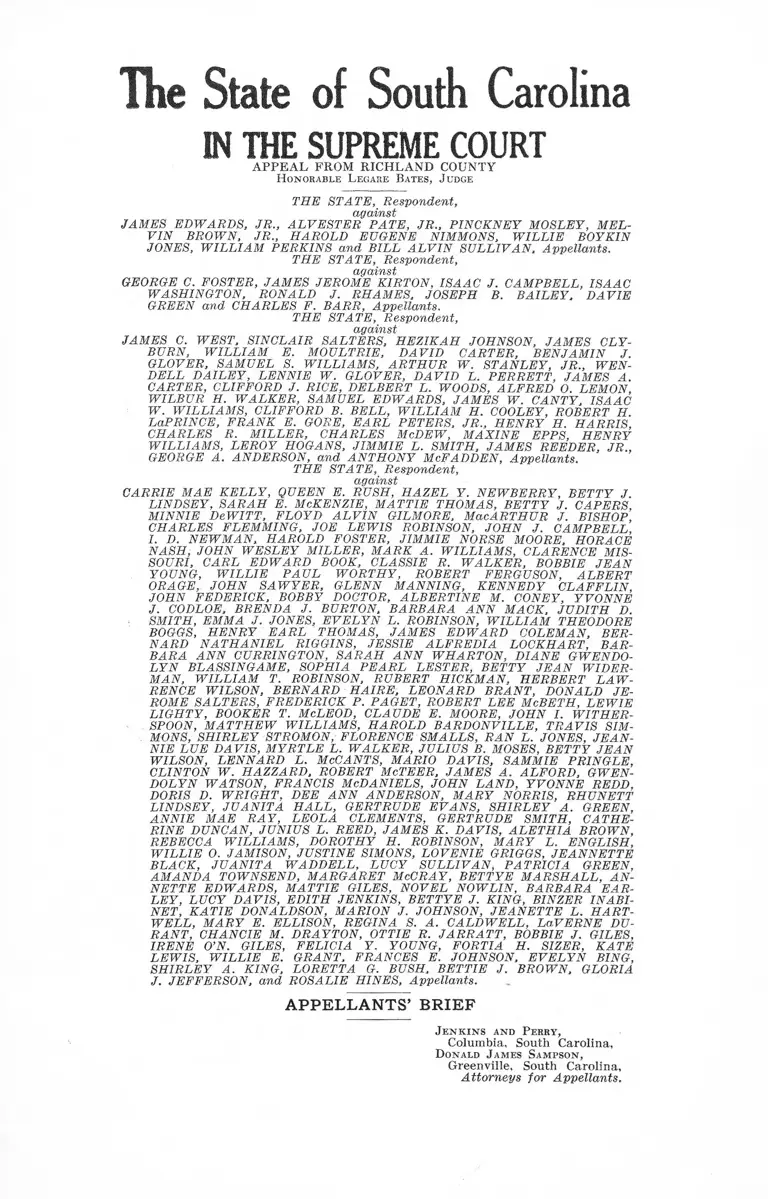

State of South Carolina

IN THE SUPREME COURT

APPEAL FROM RICHLAND COUNTY

H onorable L egare Rates, J udge

THE STATE, Respondent,

against

JAMES EDWARDS, JR., ALVESTER PATE, JR., PINCKNEY MOSLEY, MEL

VIN BROWN, JR., HAROLD EUGENE NIMMONS, WILLIE BOYKIN

JONES, WILLIAM PERKINS and BILL ALVIN SULLIVAN, Appellants.

THE STATE, Respondent,

against

GEORGE C. FOSTER, JAMES JEROME KIRTON, ISAAC J. CAMPBELL, ISAAC

WASHINGTON, RONALD J. RHAMES, JOSEPH B. BAILEY. DAVIE

GREEN and CHARLES F. BARR, Appellants.

THE STATE, Respondent,

against

JAMES C. WEST, SINCLAIR SALTERS, HEZIKAH JOHNSON, JAMES CLY-

BURN, WILLIAM E. MOULTRIE, DAVID CARTER, BENJAMIN J.

GLOVER, SAMUEL S. WILLIAMS, ARTHUR W. STANLEY, JR., WEN

DELL DAILEY, LENNIE W. GLOVER, DAVID L. PERRETT, JAMES A.

CARTER, CLIFFORD J. RICE, DELBERT L. WOODS, ALFRED 0. LEMON,

WILBUR H. WALKER, SAMUEL EDWARDS, JAMES W. CANTY, ISAAC

W. WILLIAMS, CLIFFORD B. BELL, WILLIAM H. COOLEY, ROBERT H.

LaPRINCE, FRANK E. GORE, EARL PETERS, JR., HENRY H. HARRIS,

CHARLES R. MILLER, CHARLES McDEW, MAXINE EPPS, HENRY

WILLIAMS, LEROY HOGANS, JIMMIE L. SMITH, JAMES REEDER, JR.,

GEORGE A. ANDERSON, and ANTHONY McFADDEN, Appellants.

THE STATE, Respondent,

against

CARRIE MAE KELLY, QUEEN E. RUSH, HAZEL Y. NEWBERRY, BETTY J.

LINDSEY, SARAH E. McKENZIE, MATTIE THOMAS, BETTY J. CAPERS.

MINNIE DeWITT, FLOYD ALVIN GILMORE, MacARTHUR J. BISHOP,

CHARLES FLEMMING, JOE LEWIS ROBINSON, JOHN J. CAMPBELL,

I. D. NEWMAN, HAROLD FOSTER, JIMMIE NORSE MOORE, HORACE

NASH, JOHN WESLEY MILLER, MARK A. WILLIAMS, CLARENCE MIS

SOURI, CARL EDWARD BOOK, CLASSIE R. WALKER, BOBBIE JEAN

YOUNG, WILLIE PAUL WORTHY, ROBERT FERGUSON, ALBERT

ORAGE, JOHN SAWYER, GLENN MANNING, KENNEDY CLAFFLIN,

JOHN FEDER1CK, BOBBY DOCTOR, ALBERTINE M. CONEY, YVONNE

J. CODLOE. BRENDA J. BURTON, BARBARA ANN MACK, JUDITH D.

SMITH, EMMA J. JONES, EVELYN L. ROBINSON, WILLIAM THEODORE

BOGGS, HENRY EARL THOMAS, JAMES EDWARD COLEMAN, BER

NARD NATHANIEL RIGGINS, JESSIE ALFREDIA LOCKHART, BAR

BARA ANN CURR1NGT0N, SARAH ANN WHARTON, DIANE GWENDO

LYN BLASSINGAME, SOPHIA PEARL LESTER, BETTY JEAN WIDER-

MAN, WILLIAM T. ROBINSON, ROBERT HICKMAN, HERBERT LAW

RENCE WILSON, BERNARD HAIRE, LEONARD BRANT, DONALD JE

ROME SALTERS, FREDERICK P. PAGET, ROBERT LEE McBETH, LEWIE

EIGHTY, BOOKER T. McLEOD, CLAUDE E. MOORE, JOHN I. WITHER

SPOON, MATTHEW WILLIAMS, HAROLD BARDONVILLE, TRAVIS SIM

MONS, SHIRLEY STROMON, FLORENCE SMALLS, RAN L. JONES, JEAN-

NIE LUE DAVIS, MYRTLE L. WALKER, JULIUS B. MOSES, BETTY JEAN

WILSON, LENNARD L. McCANTS, MARIO DAVIS, SAMMIE PRINGLE,

CLINTON W. HAZZARD, ROBERT McTEER, JAMES A. ALFORD, GWEN

DOLYN WATSON, FRANCIS MCDANIELS, JOHN LAND, YVONNE REDD,

DORIS D. WRIGHT, DEE ANN ANDERSON, MARY NORRIS, RHUNETT

LINDSEY, JUANITA HALL, GERTRUDE EVANS, SHIRLEY A. GREEN,

ANNIE MAE RAY, LEOLA CLEMENTS, GERTRUDE SMITH, CATHE

RINE DUNCAN, JUNIUS L. REED, JAMES K. DAVIS, ALETH1A BROWN,

REBECCA WILLIAMS, DOROTHY H. ROBINSON, MARY L. ENGLISH,

WILLIE 0. JAMISON, .JUSTINE SIMONS, LOVENIE GRIGGS, JEANNETTE

BLACK, JUANITA WADDELL. LUCY SULLIVAN, PATRICIA GREEN,

AMANDA TOWNSEND, MARGARET McCRAY, BETTYE MARSHALL, AN

NETTE EDWARDS, MATTIE GILES, NOVEL NOWLIN, BARBARA EAR-

LEY, LUCY DAVIS, EDITH JENKINS, BETTYE J. KING, BINZER INABI-

NET, KATIE DONALDSON, MARION J. JOHNSON, JEANETTE L. HART

WELL, MARY E. ELLISON, REGINA S. A. CALDWELL, LaVERNE DU

RANT, CHANCIE M. DRAYTON, OTTIE R. JARRATT, BOBBIE J. GILES,

IRENE O'N. GILES, FELICIA Y. YOUNG, FORTIA H. SIZER, KATE

LEWIS, WILLIE E. GRANT. FRANCES E. JOHNSON, EVELYN BING,

SHIRLEY A. KING, LORETTA G. BUSH. BETTIE J. BROWN, GLORIA

J. JEFFERSON, and ROSALIE HINES, Appellants.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J e n k in s and P erry ,

Columbia, South Carolina,

D onald J ames Sa m pso n ,

Greenville, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellants.

INDEX

P age

Questions Involved..................................................... 1

Statement.................................................................... 2

Argument:

Question I ........................................................... 5

Question II ....................................... 15

Question III ....................................................... 17

Question III-A .................. 17

Question III-B ............................................ 20

Conclusion .................................................................. 22

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. Did the Court err in refusing to hold that the

State failed to prove a prima facie case and failed to

establish the corpus delicti? (Exceptions 1, 2.)

2. Did the Court err in refusing to hold that the ar

rests and convictions of appellants deprived them of

the right of freedom of speech, and the right peaceably

to assemble and to petition the Government for a re

dress of grievances, in violation of Article I, Section 4

of the Constitution of South Carolina? (Exception 3.)

3. Did the Court err in refusing to hold that the

arrests and convictions of appellants deprive them of

rights guaranteed to them by the First and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution? (Ex

ception 4.)

A. Appellants’ activities are protected to them by

Article I of the First Amendment to the United

States Constitution.2

B. The arrests and convictions deny to appellants

due process of law, in violation of their rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution.3

2 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

STATEMENT

This is an appeal from an Order of Honorable Le-

gare Bates, Senior Judge, Richland County Court,

dated July 10, 1961, affirming convictions of appellants

in the City Magistrate’s Court of the City of Colum

bia.

On the morning of March 2, 1961, a group of Ne

groes, including appellants, held a meeting at Zion

Baptist Church, a Negro church located in the City of

Columbia, South Carolina. Witnesses for appellants

described the purpose of the meeting as follows (Tr. p.

136, f. 542):

“Q. Will you state the purpose of the meeting?

A. The purpose of the meeting was to reaffirm

our beliefs concerning segregation and the gen

eral principle of discrimination in order that we

may proceed from there and go to the State House

grounds.”

And, again, at Tr. p. 202, f. 807:

“A. I came to Columbia accompanied by sev

eral students from my area to a student meeting

and, in that meeting, the students discussed, in

part, racial discrimination as existed in South Car

olina and particularly in Columbia. They also dis

cussed the fact that the Legislators were in ses

sion, at that time, and decided to point out their

feelings, as it relates to segregation, by a proces

sion to the State Capitol * *

Upon learning of the meeting, the City Manager and

the Chief of Police of the City of Columbia went to the

church and inquired of the purpose of the meeting.

Pursuant to information acquired, these said officials

ordered members of the various law enforcement

SUPREME COURT_____

Appeal from Richland County

3

agencies of the City of Columbia and of Richland Coun

ty to take up positions on the State Capitol grounds

and, further, the City Manager and the Chief of Police

went to the same area. In addition to the foregoing,

various officials and officers of the South Carolina Law

Enforcement Division and the legal aide of the Gov

ernor of South Carolina were present.

At approximately 12:00 o’clock noon, groups of

Negroes were observed approaching the State Capitol

grounds, proceeding from the direction of Zion Bap

tist Church in an easterly direction along the southern

sidewalk of Gervais Street. Each group, numbering ap

proximately twenty, was composed of approximately

fifteen to twenty persons. The persons walked two

abreast; there being a distance of approximately one-

fourth to one-third of a block between each group.

Various persons in the groups carried placards upon

which were written words expressing some protest

against racial discrimination, which placards were

voluntarily removed prior to the carriers entering the

Capitol grounds.

As each group of these persons approached the

horseshoe area in front of the State Capitol grounds,

it was halted by the Governor’s legal assistant who,

after inquiring into the purpose of the presence of

these persons in the area and advising as to what they

would be allowed to do (Tr. p. 162, ft. 645-647), per

mitted them to proceed onto the grounds of the State

Capitol. During the course of later events, the number

of persons in and around this area, in addition to the

police officers and the participants in the group activi

ties, increased to approximately two hundred.

Approximately forty-five minutes after the first of

the groups entered the Capitol grounds, the City Mana-

4 SUPEEME COUET

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

ger ordered the leader of the groups that all persons

1S participating in the group movement must vacate the

grounds within fifteen minutes or suffer arrest (Tr. p.

15, f. 58). Upon their refusal to leave as ordered, ap

pellants, numbering some one hundred eighty-seven

persons, were arrested.

Appellants were charged with Breach of the Peace.

Trial by jury was waived, and appellants were tried,

in four separate trials, on March 7th, 13th, 16th and

27th, 1961, by the Columbia City Magistrate of Eieh-

land County. It was stipulated that all testimony pre-

4 sented in the first two trials would be substantially the

same in subsequent trials, and all such testimony was

ordered incorporated in the records of the subsequent

trials. The same stipulation and order were made re

garding testimony presented in the third trial.

Appellants were found guilty as charged, and sen

tences ranging from fines of ten ($10.00) dollars or

service of five days, to one hundred ($100.00) dollars

or thirty days were imposed. Thereafter, by stipula

tion, the appeals from the four trials were consolidated

and argued as one before Honorable Legare Bates,

15 Senior Judge, Eichland County Court. In the Order

from which appeal is taken, the judgments of the Mag

istrate’s Court were affirmed. Due and timely notice of

appeal from this Order was given.

16

5SUPREME COURT_____

Appeal from Richland County

ARGUMENT

Question I

Did the Court err in refusing to hold that the State

failed to prove a prima facie case and failed to estab

lish the corpus delictif (Exceptions 1 and 2.)

In general, the term “breach of the peace” is generic

and includes all manner of violations of public peace

and order. In this State, the definition of the crime

known as breach of the peace follows the general rule.

In Lyda v. Cooper, 169 S. C. 451, 169 S. E. 236, a lead

ing case, this Court defines the term as “ a violation of

public order, a disturbance of public tranquility, by any

act or conduct inciting to violence.” The Court con

tinued: “ By ‘peace’ as used in the law in this connec

tion is meant the tranquility which is enjoyed by the

citizens of a community7, where good order reigns

among its members, * * *. It is not necessary that the

peace be actually broken to lay the foundation of a

prosecution for this offense. If what is done is unjusti

fiable, tending with sufficient directness to break the

peace, no more is required.”

A careful analysis of the Court’s definition shows the

nature of the offense to be two-fold. First, it may con

sist of violent acts which actually break the peace.

Second, it may consist of unlawful or unjustifiable acts

which themselves tend with sufficient directness to

break the peace.

The American cases (see annotation in 40 A. L. R.

959) subscribe to the rule of the early English case,

Beatty v. GiUbanks (1882), L. R. 9 Q. B. Div. 308,

holding that there is no authority for the proposition

“ that a man may be convicted for doing a lawful act

if he knows that his doing it may cause another to do

6 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

an unlawful act.” In this case, certain religious fol

lowers paraded in the streets peaceably and were at

tacked by mobs who did not hold similar views. The

paraders were convicted in the trial court of a breach

of the peace, on the ground that they could reasonably

foresee that their parading would provoke others to

commit violence. The convictions were overthrown,

upon the rule above mentioned.

The instances in which a parade or demonstration

has been held to be a breach of the peace are cases in

which the conduct of the paraders was itself riotous or

criminal. In Mackall v. Ratchford, 27 C. C. A. 50, 48

U. S. App. 411, 82 Fed. 41, the paraders stationed

themselves at intervals of three to five feet along both

sides of the only road leading from the mine opening

to the non-striking miners’ homes with the evident in

tent to intimidate the non-strikers. In Cook v. Dolan.,

19 Pa. Co. Ct. 401, the action of the paraders amounted

to a trespass and was accompanied by intimidating

language and gestures. In People v. Sinclair, 149 N. Y.

S. 54, 151 N. Y. S. 1138, the parade was accompanied

by threatening and abusive language in violation of

a state statute prohibiting threatening, abusive, or in

sulting behavior on a public street. In each of these

cases, convictions for breach of the peace were sus

tained because the actions of the paraders had lost the

characteristics of a legitimate parade and, while them

selves not violent, their actions were unlawful and

tended with sufficient directness to cause others to

breach the peace.

It is submitted that each conviction for the breach of

the peace must rest upon the particular facts in each

case. For example, in the Lyda Case, supra, the de

fendant not only trespassed upon private property, but

broke into another’s closet in order to repossess per-

Appeal from Richland County

SUPREME COURT 7

sonal property. In that case, the offending conduct was

both unlawful and unjustifiable and tended with suf

ficient directness to break the peace.

Appellants activities did not constitute “a violation

of public order, a disturbance of public tranquility, by

any act or conduct inciting to violence” ; their behavior

was not unlawful or “unjustifiable, tending with suf

ficient directness to break the peace.”

Appellants walked along the public streets in single

and double file, in groups of from fifteen to thirty (Tr.

p. 23, ff. 91-92; p. 48, ff. 189-190); they were well be

haved and orderly (Tr. p. 29, f. 114; p. 48, f. 191; p. 110,

f. 437; p. 183, f. 731); they obeyed traffic regulations

(Tr. p. I l l , f. 442). The Chief of Police testified that

the public sidewalks were not blocked bv appellants

(Tr. p. 52, f. 206), that no complaint was made to him

by anyone wishing to use the walkways that such per

son was prevented from passing (Tr. p. 52, f. 208), and

that, to his knowledge no vehicular traffic was blocked

in the horseshoe area (Tr. p. 53, ff. 209-211). Further

more, testimony throughout the record is to the effect

that the main use of the horseshoe area is to provide

parking space for State House personnel.

Testimony from all witnesses for both the State and

appellants is that the appellants were not loud or

boisterous at any time prior to having been given an

ultimatum by the City Manager to leave the State

Capitol grounds within fifteen minutes or face arrest

(Tr. p. 16, ff. 61-62; p. 51, f. 202; p. 59, f. 234; p. 139,

f. 556; pp. 173-174, ff. 691-695). The lone exception to

the foregoing is the testimony of the State’s witness,

Shorter. His testimony is in direct conflict with all

other testimony and the surrounding circumstances so

much so that it is unworthy of consideration.

8 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

There is no place in this record any showing of vio

lence or threat of violence, either by or against any of

these appellants. It would appear that the strongest

support of any contention of violence would be the

summation of the City Manager’s testimony by counsel

for the State (Tr. p. 17, f. 66):

“ * * * He hasn’t said anything was going to

happen.

He said it appeared to him that in those circum

stances that something could happen.” (Italics

added.)

The public did not appear unduly disturbed. At one

point the State’s witness testified that “ the crowd

could be best described as curious as to what was going

on.” (Tr. p. 31, f. 123.) There is no evidence in the rec

ord of a contrary attitude. With reference to the be

havior of appellants, this same witness testified (Tr. p.

185, IT. 737-739):

“ Q. Of your own knowledge, do you know of any

of these Negro defendants in this group or other

groups who you would call trouble makers?

A. Not in the sense that I was using the word

previously, no.

Q. You don’t know, of your own knowledge, of

any instance when they have participated in any

act of violence !

A- No.

Q. Do you know of any instance where they have

urged any act of violence?

A. No, I do not.

Q. I believe you are generally familiar with the

overall movement, as expressed by these defend

ants, throughout the City of Columbia for the past

year?

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Richland County

9

A. I am quite familiar with it.

Q. Do you know, of your own knowledge, of any

violence on the part of any of those Negro par

ticipants in those activities?

A. No, I do not.

Q. And would you say that these defendants are

typical of the other persons involved in the same

group, in your experience throughout the past

year ?

A. Yes, I would.”

Other witnesses testified as follows (Tr. pp. 140-141,

ft. 557-561):

“Did you personally interfere with anybody in

the use of the sidewalks and the streets on that

day?

A. By no means.

Q. Did you personally interrupt any vehicular

traffic on the streets that day?

A. I did not.

Q. Are you aware of any of your comrades who

were with you on that date who interfered with

the use of the streets by other citizens?

A. If they did, it was not brought to my at

tention.

Q. Is it true that a large number of onlookers

gathered while you were there on the State House

grounds ?

A. Adjacent to the State House, yes.

Q. Did you pay any particular attention to

them ?

A. Well, only generally. I just generally saw

them.

Q. Did you hear any remarks being made by any

who may have been in the audience there?

10

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

SUPREME COURT

A. No, I didn’t.

Mr. Coleman: I didn’t catch that question.

Mr. Jenkins: I asked him if he heard any re

marks being made by any other persons who were

in the audience that day. I meant by persons in

the audience, the onlookers, persons not actually

engaged in the group with you.

A. If they said something, I didn’t hear it.

Q. Did you observe any overt action on their

part which would put you in fear that you would

be in danger of being injured or anything of that

sort?

A. My composure was not hampered by any one.

Q. You mean by that, nobody frightened you by

any action ?

A. None whatsoever.

Q. Did you observe any of your comrades or

persons with you who appeared to be apprehensive

that they would be attacked by any person?

rA. If they felt it, they didn’t show it.

Q. By the group, I mean any of the onlookers

who may have been there ?

A. No.”

It is significant that all of the State’s witnesses, with

two exceptions, are trained, experienced police officers.

Of the exceptions, one is a trained city manager of

long years of experience and the other is a newspaper

reporter of extensive experience. Yet, these witnesses

can identify, from a total of one hundred eighty-seven

persons, only four of these appellants as having com

mitted any specific act which gave rise to the charges

and convictions. The following is the testimony con

cerning the acts of breach of the peace by those identi

fied:

Appeal from Richland County

SUPREME COURT 11

“ Q. Insofar as the defendant Carter is con

cerned, the misconduct on his part was that he

harangued, did you say?

A. He was a very active fellow that morning, in

addition to organizing, keeping them all in line,

issuing instructions, generally, to them upon my

instructions to him, to have the group dispersed,

then he proceeded with his harangue or whatever

you wish to call it.” (Tr. p. 183, f. 729.)

# * #

“Q. Now I ask you this, Mr. Barnett, do you re

call having seen any of these particular defendants

blocking the traffic or the sidewalks ?

A. Oh, yes.

Q. Could you identify them?

A. Oh, yes.

Q. Would you care to identify them by pointing

out and having them stand up?

A. Well, I can identify Carter and Ms lieuten

ant or captain, Charles McDew, back there, the

Reverend Glover.”

The witness testified that these appellants on two oc

casions blocked traffic on the sidewalks. (Tr. pp. 193-

194, ff. 771-773.)

Appellants Williams and Carter were identified by

Chief Campbell as having committed some act of

breach of the peace, but the record is not clear as to

what the act was. (Tr. p. 196, f. 782.)

This testimony points to the “guilt” of appellant Mc

Dew (Tr. p. 198, ff. 789-790):

“A. McDew attends school in Orangeburg and

he’s on the third seat, back on the left. I can identi

fy him as particularly breaching the peace. He led

the first group and was very belligerent as he went

12

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

SUPBEME COUBT

around, wanting to go through the walkways, criss

cross, in double file, which I asked him not to do.

He stopped on each walkway and insisted that he

do so. I told him he could go through in single file,

in smaller groups, that’s McDew.”

It would appear that this appellant breached the

peace by insisting that he had the right to walk on the

sidewalks.

No other appellant is identified as having committed

any specific act of breach of the peace. In fact, no wit

ness identifies any of the other appellants as having

done anything at all, other than be arrested. Other than

that they were arrested, there is no evidence in the

record that they were even present in the general area

of the State Capitol grounds, with the exception of a

few. More than one hundred eighty appellants were

convicted on no evidence whatsoever other than that

they were arrested in the area of the State Capitol

grounds; simply that and nothing more.

Feiner v. New York , 71 S. Ct. 303, 340 U. S. 315, is

not contrary to the general rules pertaining to in

stances of breach of the peace. As in all such cases,

Feiner is controlled by the facts particular to the cir

cumstances. The State Court found as a matter of fact

as follows: The speaker made disparaging remarks

concerning individuals and a veterans organization;

the crowd openly took sides and openly expressed its

partisanship; crowd grew restless, there was pushing,

shoving and milling around; pedestrians were forced

to walk in the street to get by the crowd; vehicular

traffic was almost blocked; the mood of the crowd be

came openly hostile; one person made threats to the

policeman that he would do violence if the speaker were

not stopped and people in the crowd openly expressed

Appeal from Richland County

SUPREME COURT__ 13

doubt that the policemen (two) could control the

crowed.

But even those things were not controlling of the

finding of guilty, nor of the upholding of the lower

court decision by the United States Supreme Court.

The crux of the ruling was the finding that the speaker

obviously was endeavoring to arouse Negroes against

whites, urging that Negroes rise up in arms and fight.

The United States Supreme Court, divided in this

opinion five-four, stated: “ A State may not unduly sup

press free communication of views, religious or other,

under the guise of conserving desirable conditions.

Cantwell v. State of Connecticut, supra, 310 U. S. at

page 309, 60 S. Ct. at page 905, 84 L. Ed. 1213. But we

are not here faced with such a situation. It is one thing

to say that the police cannot be used as an instrument

for the suppression of unpopular views, and another to

say that, whereas here the speaker passes the hounds of

argument or persuasion and undertakes to incitement

to riot, they are powerless to prevent a breach of the

peace.” (Italics added.)

Contrast, then, the conduct of the defendant in

Feiner and the surrounding circumstances with the

conduct of appellants in the instant case and the en

vironment out of which the charge of breach of the

peace stems.

Of the 187 appellants, less than six are identified by

the State as having done any of the specific acts which

the State alleges is a breach of the peace. One appel

lant, the recognized leader of the movement, when or

dered by the City Manager to warn the group that un

less they left within fifteen minutes they’d suffer ar

rest, is described as having relayed the information in

the manner of a religious chant, to have “harangued”

the group (Tr. pp. 165-166, f. 660). Two are said to

14

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

SUPREME COURT

have blocked traffic, and another insisted upon his right

to walk on a sidewalk. Otherwise, appellants are identi

fied only as having been arrested.

Appellants walked in small groups, one or two

abreast, a third of a block between each group. They

spoke to no one; no one spoke to them, except some

remarks of encouragement. There is no evidence in the

record that anyone was blocked in passing along the

walkways. There was no disruption of vehicular traffic.

The horseshoe is a parking lot for State employees; it

is no passageway for the general public. True, evidence

shows that vehicles would have been inconvenienced by

the crowd in the circle, but there is no evidence that

any vehicle attempted to move in the horseshoe, that

the police tried to disperse the crowd there or that they

would not have moved if requested.

Had not each group of appellants been stopped

by the police as they reached the entrance to the

Capitol grounds, there would have been no con

gregating among the groups of participants. The

police themselves brought about the situation they then

used as one of the grounds for the charges against the

appellants. The crowds of onlookers'were not unruly,

were not hostile, voiced no threats, moved along when

told b}r police; there was no shoving, no pushing, no

milling about. There was no expressed opinion that

the number of officers present could not handle the

situation. Indeed, the City Manager, the principal

character for the State, both on the day of the occur

rence and as its star witness at the trials, testified as

follows (Tr. p. 167, f. 666):

“Q. You had ample time, didn’t you, to get

ample police protection, if you thought such was

needed on the State House grounds, didn’t you?

A. Yes, we did.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Richland County

15

Q. So if there were not ample police protection

there, it was the fault of those persons in charge

of the Police Department, wasn’t it!

A. There was ample police protection there.”

Here there was no violence, nor threat of violence;

no incitement to riot, nor likelihood of same.

It is submitted that the State, having proved no con

duct on the part of any appellant, or by the group, of

a violent nature that actually broke the peace, and hav

ing proved no unlawful or unjustifiable acts which

themselves tend with sufficient directness to break the

peace, has failed to establish th corpus delicti and

failed to prove a prima facie case.

Question II

Did the Court err in refusing to hold that the arrests

and convictions of appellants deprived them of the

right of freedom of speech, and the right peaceably to

assemble and to petition the government for a redress

of grievances, in violation of Article I, Section 4 of the

Constitution of South Carolina? (Exception 3.)

Appellants were arrested upon the State Capitol

grounds after refusing to heed the ultimatum of the

Columbia City Manager that they leave the grounds

within fifteen minutes. Appellants avowed purpose for

being on the Capitol grounds, which purpose was al

ready known to the governmental officials (Tr. p. 42,

f. 166; p. 82, f. 327), was to call to the attention of the

State Legislature, other State officials and the public

their dissatisfaction with discriminatory laws, cus

toms and usages, based on race or color, and to attempt

to persuade the cessation of such lawrs, policies and

practices (Tr. p. 136, f. 542; pp. 138-139, ff. 549-554;

p. 202, ff. 807-808; p. 206, ff. 821-822). In furtherance

16 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

of tlieir aim appellants proceeded to walk, in orderly

fashion, to the State Capitol grounds. Some carried

placards that displayed the general purpose of the

group (Tr. p. 142, f. 563). Once upon the Capitol

grounds, they proceeded in disciplined fashion along

the paved walkways. They directed no disparaging

remarks to anyone; they made no overt signs of vio

lence or incitement to violence; there was no showing

of fear, violence or apprehension on the part of any

spectator (Tr. pp. 204-205, ff. 816-817). The uncontra

dicted testimony of one witness is as follows (Tr. p.

204, f. 814):

“ Q. Reverend Glover, did you pay any particu

lar attention to the onlookers, who were around

the area?

A. Most of them, as I observed, some faces were

smiling, perhaps a gesture of good faith, and on

one occasion two or three persons approached with

an intention of shaking hands.”

Only after being issued an ultimatum, and in some

cases only after arrest, did they break into singing. The

songs were patriotic or religious; the singing orderly

and controlled.

The right of the people by organization to co-op

erate in a common effort and by a public demonstra

tion or parade to attempt to influence public opinion

in a peaceable manner and for a lawful purpose is

regarded as among the fundamental rights of citizens

(Shields v. State (Wis. 1925), 204 N. W. 486, 40 A.

L. R. 954; Chicago v. Trotter (1891), 136 111. 430, 26

N. E. 359). Various courts have spoken of this right

as existing immemorially (In re Frazee., 63 Mich. 396,

30 N. W. 72). Certainly it has been given official sanc

tion and recognition in the English common law (Beat-

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Richland County

17

ty v. Gillbwiks, supra), and by a substantial number of

the Supreme Courts of the several States (State ex

rel. Garrabad v. Deering, 84 Wis. 585, 54 N. W. 1104;

Anderson v. Wellington, 40 Kans. 173, 19 Pac. 719

and State v. Hughes, 72 N. C. 25).

The rights as expressed by the courts are guaran

teed appellants by the Constitution of South Caro

lina.1 We view it as significant that counsel has been

unable to find any reported South Carolina case deal

ing with a denial to any citizen these constitutional

freedoftis.

Question III

Did the Court err in refusing to hold that the ar

rests and convictions of appellants deprive them a

rights guaranteed to them by the first and Fourteenth

Amendments to the United States Constitution? (Ex

ception 4.)

A. Appellants’ activities are protected to them by

Article I of the First Amendment to the United

States Constitution.2

The record in this case proves the following: Ap

pellants, being aggrieved by certain discriminatory

laws, customs and usages, based solely on race or

color, formed small groups and proceeded from a cen

tral meeting point to the State Capitol grounds, where

the State Legislature was in session, for the purpose

of seeking redress of their grievances. Appellants,

1 Article 1, Section 4, Constitution o f South Carolina provides:

The General Assembly shall make no law respecting an establish

ment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridg

ing the freedom of speech or of the press; or the right of the

people peaceably to assemble and to petition the Government or

any department thereof for a redress of grievances.

2 Congress shall make no law * * * abridging the freedom of

speech, or of the press; or the right o f the people peaceably to as

semble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.

18 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

some of whom carried placards expressing the dissat

isfaction of the group, were orderly in every respect;

they obeyed traffic signals, walked in single or double

file; there is no evidence that there was any bodily

contact, or threat thereof, between appellants and

anyone else. The record does not support the conten

tion that any person was prevented from using the

streets or sidewalks by the actions of the appellants,

nor is there evidence that any vehicular traffic was

halted. Appellants made no overt act or threat, di

rected no remarks or abuse towards anyone whomso

ever ; nor did anyone direct any such activity towards

appellants. Appellants sang songs, patriotic and re

ligious, in an orderly and controlled fashion, only after

having been threatened with arrest if they didn’t

leave within fifteen minutes, and in some cases, only

after arrest.

The Supreme Court of the United States has on

numerous occasions upheld the right of citizens to

peaceably assemble to give expression to their griev

ances and to petition for a redress thereof. U. 8. v.

Cruikshank, 92 U. S. 542, 23 L. Ed. 588; Hague v. CIO,

307 U. S. 496; 83 L. Ed. 1425; Thornhill v. Alabama,

310 U. S. 88, 84 L. Ed. 1093.

In U. S. v. Cruikshank, supra, the Court said:

“ The right of the people to assemble for the

purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress of

grievances, or for anything else connected with

powers or the duties of the national government,

is an attribute of national citizenship, and, as

such, under the protection of, and guaranteed by,

the United States. The very idea of a government,

republican in form, implies a right on the part of

its citizens to meet peaceably for consultation in

Appeal from Richland County

respect to public affairs and to petition for a re

dress of grievances * *

Quoting this statement with approval, in Hague v.

CIO, supra, the Court added: “ No expression of a

contrary view has ever been voiced by this court. ’ ’

In Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 84 L. Ed.

1213, the Court made an analysis of the relationship

between First Amendment rights and breach of peace.

After stating that one may be guilty of the offense if

he commits acts or makes statements likely to provoke

violence and disturb good order, even though same be

not intended, the Court said: “ Decisions to this effect

are many hut examination discloses that, in practically

all, the provocative language which was held to he a

breach consisted of profane, indecent, or abusive re

marks directed to the person of the h e a r e r (Italics

added.)

In Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1, 93 L. Ed.

1131, the Court re-emphasized the rule, clearly stated

in Cantwell v. Connecticut, supra, that “ freedom of

speech, though not absolute, is nevertheless protected

against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely

to produce a clear and present danger of a serious

substantive evil that rises far above public inconven

ience, annoyance or unrest.” Further, Cantwell holds

that the danger of substantive evils sufficient to justi

fy impairment of constitutional rights of freedom of

speech, assembly and religion and punishment for al

leged violation thereof must be more clearly shown

where the punishment is based on common-law con

cepts (as in the instant case), than where it is specif

ically sanctioned by a legislative declaration of state

policy. (See Hague v. CIO, supra,, where the United

States Supreme Court struck down a city ordinance

SUPREME COURT 19

20 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

as patently permitting the absolute denial of the right

of assembly.)

The Supreme Court, in Bridges v. California, 314

U. S. 252, 303; 86 L. Ed. 192, 203, laid down this rule:

“ What finally emerges from the ‘ clear and present

danger’ cases is a working principle that the sub

stantive evil must be extremely serious and the degree

of imminence extremely high before utterances can be

punished.” In the instant case, the only “ substantive

evil” shown by the record is the possibility of con

gesting pedestrian and vehicular traffic along a rel

atively small area. The only “ degree of imminence”

was, as respondent’s counsel sununed up the testi

mony of his chief witness, that “ it appeared to him

that in those circumstances that something could hap

pen.” (Italics added.) (Tr., p. 17, f. 66.)

We reiterate, Feiner v. New York., supra, sets forth

no contrary view to the general rules of the Cantwell,

Terminiello, Hague and Bridges cases. Feiner turns

on “ The findings of the state courts as to the existing

situation and the imminence of greater disorder * *

B. The arrests and convictions deny to appel

lants due process of law, in violation of their

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment to

the United States Constitution,3

It is submitted that this record is devoid of any

evidence that appellants engaged in any conduct of

any kind likely in any way to adversely affect the

good order and tranquility of the State of South Car

olina. At most, there is some showing of slight incon

venience and annoyance. Certainly there is no show-

8 * * * nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or

property, without due process of law. United States Constitution,

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1.

21

________ Appeal from Richland County

ing of a “ danger of substantive evils sufficient to jus

tify impairment of constitutional rights of freedom

of speech, and assembly and punishment for alleged

violation thereof.”

There being no support for these convictions in

the record, they are void as denials of due process.

Thompson v. City of Louisville, infra. “ Just as ‘ con

viction upon a charge not made would be sheer denial

of due process’, so it is a violation of due process to

convict and punish * * * without evidence of

# * * guilt.’ ’ Thompson v. City of Louisville., 362

U. S. 199, 80 S. Ct. 629 (1960).

________________ SUPREME COURT

82

22 SUPREME COURT

The State v. James Edwards, Jr., et al.

CONCLUSION

It is submitted, that the State has failed, first, to

meet the test of this Court that the necessary elements

to support a conviction of breach of the peace are acts

violent in themselves, or unlawful or unjustifiable acts

which themselves tend with sufficient directness to

break the peace; and, second, to meet the test as laid

down by the Supreme Court of the United States that

the acts complained of must present a substantive

evil that in itself must be extremely serious and the

degree of imminence extremely high before First and

Fourteenth Amendment rights can be abridged by a

conviction for breach of the peace.

For the reasons herein stated, the judgments of

the County Court of Richland County affirming the

judgments of the Columbia City Magistrate of Rich

land County should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J e n k in s & P e r k y ,

Columbia, S. C.,

D o n ald J a m e s S a m p s o n ,

Greenville, S. C.,

Attorneys for Appellants.