O'Day v. McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Company Plaintiff's Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

November 6, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. O'Day v. McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Company Plaintiff's Reply Brief, 1992. 3f1cf414-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0efcaae3-ceeb-4255-bba2-7702905d4d92/oday-v-mcdonnell-douglas-helicopter-company-plaintiffs-reply-brief. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

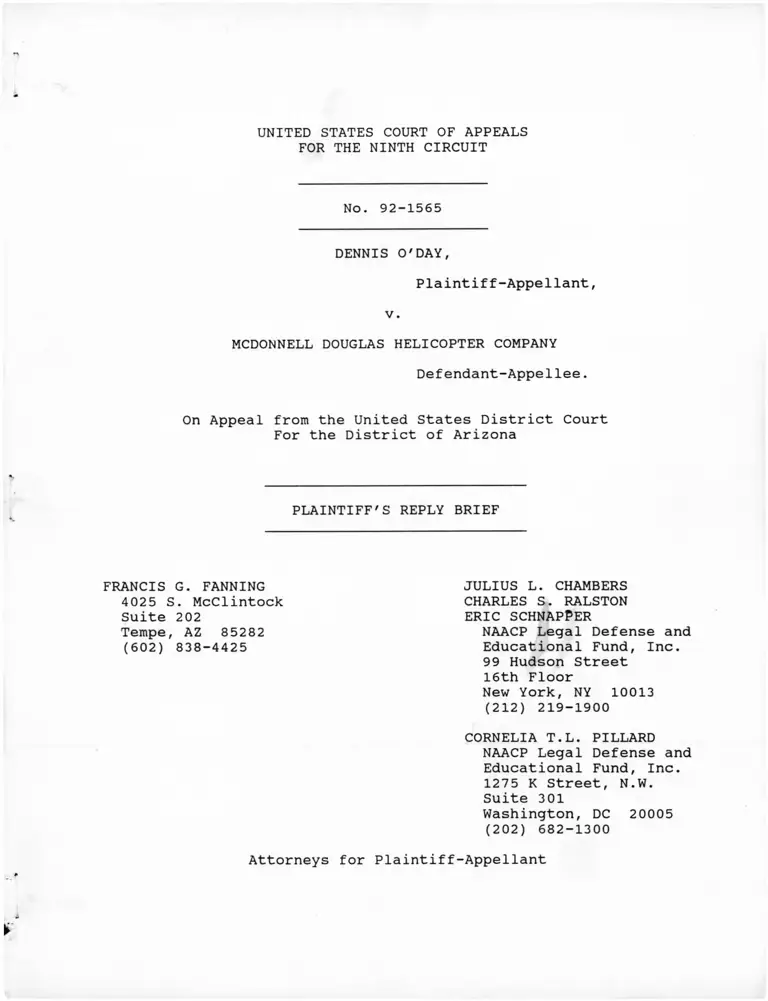

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 92-1565

DENNIS O'DAY,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

MCDONNELL DOUGLAS HELICOPTER COMPANY

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the District of Arizona

PLAINTIFF'S REPLY BRIEF

FRANCIS G. FANNING

4025 S. McClintock

Suite 202

Tempe, AZ 85282

(602) 838-4425

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES S. RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

No. 92-1565

DENNIS O'DAY,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

MCDONNELL DOUGLAS HELICOPTER COMPANY

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the District of Arizona

PLAINTIFF'S REPLY BRIEF

FRANCIS G. FANNING

4025 S. McClintock

Suite 202

Tempe, AZ 85282

(602) 838-4425

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES S. RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...................................... ii

A R GUMENT.............................. 1

I. MIXED MOTIVE ANALYSIS UNDERMINES RATHER THAN SUPPORTS

THE DECISION OF THE DISTRICT COURT .................... 2

A. Under The 1991 Civil Rights Act, A Mixed Motive is

a Partial Remedial Bar, Not a Complete Defense . . 3

B. After-Acquired Evidence Cannot Entirely Eliminate

O'Day's Backpay Claim ........................... 5

II. RECENT CIRCUIT COURT CASES SUPPLY ADDITIONAL AUTHORITY

IN SUPPORT OF REMAND.....................................11

A. This Court Should Follow The Approach of the

Eleventh Circuit in Wallace v. Dunn Construction

Co. . Inc. .........................................11

B. Even Recent Cases Relying on Summers v. State Farm

Mutual Auto Ins. Co. Recognize The Right of a

Plaintiff in O'Day's Circumstances to Obtain

R e l i e f .............................................13

III. MDHC'S CONTENTION THAT NO REMEDY IS FEASIBLE HERE IS

CONTRARY TO THE ADEA'S MANDATE TO FASHION THE MOST

COMPLETE RELIEF POSSIBLE ............................ 16

IV. O'DAY'S CONDUCT IN COPYING THE EMPLOYEE RANKINGS WAS

PROTECTED ACTIVITY .................................... 19

CONCLUSION...................................................21

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGES

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody.

422 U.S. 405 (1975) .................................... 17

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby.

477 U.S. 242 (1986) .................................... 18

Davis v. City and County of San Francisco. No. 91-15113,

1992 WESTLAW 251513 (9th Cir. Oct. 6 1992)................ 4

Kelly v. American Standard. Inc..

640 F. 2d 974 (9th Cir. 1981).............................. 4

Melnvk v. Adria Laboratories.

1992 U.S.DIST LEXIS 10584 (W.D.N.Y. July 2, 1992) ........ 4

Mount Healthy City Board of Ed. v. Doyle,

429 U.S. 274 (1977) ...................................... 3

Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins. 490 U.S. 228 (1989) . . . . 3, 7

Reed v. Amax Coal Company, 971 F.2d 1295 (7th Cir. 1992) . . 14

Rose v. National Cash Register Corp..

703 F. 2d 225 (6th Cir. 1983)............................ 17

Smallwood v. United Airlines. Inc.,

728 F. 2d 614 (4th Cir. 1984)............................ 15

Smith v. General Scanning, Inc..

876 F. 2d 1315 (7th Cir. 1989) ...................... 13 , 14

Summers v. State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company,

864 F. 2d 700 (10th Cir. 1988) ...................... passim

Sutton v. Altantic Richfield. 646 F.2d 407 (9th Cir. 1981) . . 5

Wallace v. Dunn Construction Co., Inc..

968 F. 2d 1174 (11th Cir. 1992)...................... passim

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. § 2201 4

29 U.S.C. § 623 (d) ........................................ 9

Pub. L. 102-166, 105 Stat. 1071

(Civil Rights Act of 1991).............................. 2-5

ii

ARGUMENT

The parties agree that the existence of an ADEA claim should

not give an employee an advantage that he would not have had in

the absence of discrimination. Brief of Defendant-Appellee, at

4-15; Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant, at 16.1 Plaintiff-appellant

Dennis 0'Day does not seek to be protected from any action

McDonnell Douglas Helicopter Corporation ("MDHC") would have

taken against him if MDHC had not discriminatorily refused him

promotions and discharged him based on his age. MDHC refuses,

however, to concede the logical corollary of the same principle,

which is that an employer should not gain economic advantage or

additional prerogatives over an employee because the employee

suffers discrimination and files a claim.

MDHC asserts that after-acquired evidence of a legitimate,

nondiscriminatory reason for discharge eliminates a

discrimination plaintiff's right to backpay at a point earlier

than the salary cutoff point of an employee in similar

circumstances who was not subject to employment discrimination.

Moreover, MDHC insists that its discriminatory decisions denying

0'Day promotions and discharging him must be deemed appropriate

based on conduct by O'Day which (a) did not occur until after the

challenged promotion denials, and therefore cannot logically

provide any basis for them whatsoever, (b) would not even have

even happened had MDHC not discriminated, and which (c) MDHC 1

1 Hereinafter, citations to defendant-appellee MDHC's

brief appear as "Deft's. Br. at _," and citations to the opening

brief of plaintiff-appellant Dennis O'Day's appear as "Pltf's.

Br. at ."

cannot prove was such serious misconduct under MDHC policy that

it would in the absence of discrimination have caused the

discharge of an experienced, exemplary employee like O'Day.

The appropriate application of the after-acquired evidence

doctrine requires precisely what MDHC decries (see Deft's. Br. at

12) — a fact-specific remedial analysis which strikes a balance

between an employer's prerogative to make legitimate employment

decisions and an employee's right to be free from illegal

discrimination. This is the analysis that the Eleventh Circuit

recently adopted in Wallace v. Dunn Construction Co.,_Inc., 968

F.2d 1174, 1181 (11th Cir. 1992). This Court should follow

Wallace. Because the district court failed to determine

liability and to conduct an appropriate remedial analysis, the

decision must be reversed and the case remanded. I.

I. MIXED MOTIVE ANALYSIS UNDERMINES RATHER THAN

SUPPORTS THE DECISION OF THE DISTRICT COURT

A principal authority on which MDHC relies is the "mixed-

motive" doctrine, which MDHC contends provides a complete

defense. Its reliance is misplaced for two main reasons. First,

section 107 of the 1991 Civil Rights Act applies here, and that

section provides that where legitimate as well as discriminatory

reasons motivated a challenged employment decision, the plaintiff

is still entitled to a remedy. Second, although the legitimate

factors within a mixed motive may limit a plaintiff's remedy from

the time of the adverse employment decision, a legitimate factor

revealed through after-acquired evidence can only limit the

2

remedy from the time the factor is first known. Thus, while

backpay may be wholly unavailable in a mixed motive case, some

back pay should generally be awarded in an after-acquired

evidence case.

A. Under The 1991 Civil Rights Act, A Mixed

Motive is a Partial Remedial Bar, Not a

Complete Defense_______________________

Congress last year amended mixed-motive doctrine in section

107 of the 1991 Civil Rights Act. Far from supporting MDHC's

position, the current mixed motive standard as set forth in the

1991 Act unequivocally requires reversal of the district court's

decision. MDHC contends that under the constitutional mixed-

motive analysis of Mount Healthy City Bd. of Ed._v_._Doyle, 429

U.S. 274 (1977), as applied to Title VII in Price Waterhouse v.

Hopkins. 490 U.S. 228 (1989), "proof of an employer's lawful

reasons for an adverse employment action will deprive the

plaintiff of any remedy for unlawful discrimination, despite

uncontradicted proof that the employer harbored an unlawful

motive for its adverse employment action." Deft's. Br. at 10.

This is simply not an accurate statement of the law. Where an

employer can prove that it had lawful as well as discriminatory

reasons for a challenged employment decision, section 107 of the

1991 Act provides that the court "may grant declaratory relief,

injunctive relief ... and attorney's fees and costs demonstrated

to be directly attributable" to the pursuit of the discrimination

claim. 1991 Civil Rights Act, section 107, Pub. L. 102-166, 105

3

Stat. 1071; see opening Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant, at 14-15.

Under the 1991 Act, even if MDHC proved that it would have fired

Dennis O'Day for copying the employee rankings, O'Day would still

be entitled to a declaration that MDHC unlawfully discriminated,

an injunction against future discrimination, and fees and costs

for proving that MDHC discriminated. Moreover, if O'Day proved

that the discrimination was willful, he would additionally be

entitled to liquidated damages.2

Although MDHC relies on the mixed motive doctrine enunciated

in the Price Waterhouse case, it nonetheless contends that

section 107 of the 1991 Civil Rights Act, which was enacted

specifically to amend Price Waterhouse, is inapplicable to ADEA

claims. Deft's. Br. at 7, n.4; id. at 11, n.5. MDHC cannot have

it both ways. By the same token that Price Waterhouse, developed

in the context of Title VII claims, applies to this ADEA case, so

does the 1991 Act. See, e.g. . Melnyk v. Adria Laboratories, 1992

U.S.DIST LEXIS 10584 at *28, n. 5 (W.D.N.Y. July 2, 1992)

(applying § 102 of 1991 Civil Rights Act to both Title VII and

ADEA). Both Title VII and ADEA have parallel structures and

remedial purposes, and the doctrine developed under one statute

2 Even if the plaintiff is not entitled to the full

backpay award by which liquidated "double damages" are measured

under the ADEA, full liquidated damages can be appropriate. The

purpose of liquidated damages, unlike backpay, is not to make the

employee whole, but to serve as a deterrent against particularly

egregious discrimination. Kelly v. American_Standardt— Inc..., 640

F.2d 974, 979 (9th Cir. 1981). An employee's misconduct may mean

that less backpay is required to return him to where he would

have been but for the discrimination, but it does not diminish

the extent of the employer's illegal motive.

4

is routinely applied under the other. See. e.q., Sutton v.

Altantic Richfield. 646 F.2d 407 (9th Cir. 1981) (applying

McDonnell Douglas v. Green standards, developed under Title VII,

to ADEA case).

Contrary to MDHC's assertion, Deft's. Br. at 7, n. 4, the

1991 Civil Rights Act does apply to pending cases such as this

one. This Court recently determined that "the language of the

Act reveals Congress' clear intention that the majority of the

Act's provisions be applied to cases pending at the time of its

passage." Davis v. City and County of San Francisco, No. 91-

15113, 1992 WESTLAW 251513 (9th Cir. Oct. 6, 1992). The only

provisions which this Court held do not apply are those which are

expressly excepted from the general rule of immediate

application. See 1991 Civil Rights Act, §§ 109(c), 402(b). MDHC

itself has conceded that if the 1991 Act applies, "complete

avoidance of liability is no longer guaranteed...." Deft's. Br.

at 11, n.5. Davis reguires application of the 1991 Act here.

Under the 1991 Act, the district court decision must be reversed,

and the case remanded for a determination of liability and an

appropriate remedy.

B. After-Acguired Evidence Cannot Entirely

Eliminate O'Dav's Backpay Claim________

The second reason that MDHC's reliance on the mixed-motive

doctrine is misplaced is that, unlike a nondiscriminatory reason

in a mixed-motive case, an after-discovered reason cannot cut off

backpay relief from the moment of of the disputed decision

5

onward, but only has the potential to limit backpay from the time

the nondiscriminatory reason is later discovered. In mixed-

motive cases, the legitimate motive is an actual cause of the

challenged employment decision, motivating the employer when the

decision is made. An after-acquired nondiscriminatory reason, in

contrast, is by definition not a reason that motivated the

employer at the time of the employment decision; rather, such a

reason emerges only later. Thus, provided that discrimination

can be proved, some backpay relief is required here, and the

district court therefore erred in granting summary judgment.

MDHC's contends, precisely to the contrary, that:

an employer's legitimate basis for terminating the

plaintiff accrues at the moment the employee engages in

the serious misconduct, not when the employer first

learns of it. Therefore, such misconduct, ab initio,

extinguishes the right to any remedies for harm the

plaintiff suffers thereafter as a result of unlawful

discrimination.

Deft's Br. at 14. This theory does not support remand in this

case, is unfair to discrimination plaintiffs, and should be

rej ected.

One reason that MDHC's theory of an "ab initio" backpay bar

— i.e. a bar that operates retroactively to the time of the

alleged misdeed — is incorrect in this case is that it assumes

that MDHC could bear a factually impossible burden of proof. If

he proves discrimination, O'Day is presumptively entitled to a

remedy. MDHC then has the opportunity to prove that it would

have taken the challenged adverse action in any event, and

O'Day's relief is only reduced to the extent that MDHC bears that

6

burden. But MDHC simply cannot prove that, in the absence of its

own age discrimination against O'Day, it would have discovered

immediately that O'Day copied employee rankings and would have

fired him outright.3

MDHC cannot prove it would have fired O'Day because the

asserted nondiscriminatory reason for such firing would not even

have occurred if MDHC had not discriminated. It is uncontested

3 MDHC asserts that it need only prove what it would have

done by a preponderance of the evidence. Deft's. Br. at 18.

MDHC arrives at this conclusion by applying a rejected mixed

motive analysis, and applying it out of context. This Circuit

employs the higher clear-and-convincing evidence standard to a

defendant who seeks to limit the remedies to which a victim of

proven discrimination is presumptively entitled. See Pltf's.

Br., at 17 (citing cases).

Price Waterhouse, upon which MDHC relies, analyzed the mixed

motive question as one of liability, not remedy, and therefore

used the lower preponderance standard. Price Waterhouse itself,

however, approved the use of the clear and convincing standard at

the remedy phase. 490 U.S. at 253-54; see Brief of Amicus EEOC,

at 21 n. 8. Section 107 of the 1991 Civil Rights Act has since

made clear that the mixed motive issue is properly analyzed not

as a defense to liability, but as a potential remedial bar —

which is precisely how the Supreme Court in Price Waterhouse

acknowledged this Circuit had analyzed the issue. 490 U.S. at

238, n.2. Therefore, in light of section 107 of the 1991 Act,

the higher proof standard should apply to mixed motive cases.

In any event, the after-acquired evidence doctrine is

distinct from the mixed motive analysis even under Price

Waterhouse. As the Supreme Court there made clear, the only

motives that bear on liability are the actual motives present at

the time of a disputed employment decision. Price Waterhouse,

490 U.S. at 241; see Pltf's. Br. at 13. After-acquired evidence

relates to motives necessarily not present at the time, and thus

necessarily presents a remedial and not a liability issue,

subject to the higher proof standard.

The decision of the Eleventh Circuit in Wallace erroneously

holds that the appropriate standard is preponderance of the

evidence, and should not be followed in this regard. 968 F.2d at

1181, n.ll.

7

that the very reason that O'Day sought to review the employee

rankings was that he had been discriminatorily denied promotions.

Any effort to reconstruct what would have happened had MDHC not

discriminated against O'Day accordingly must conclude that O'Day,

with his long record of good service to MDHC and lack of any

disciplinary problems, would not have copied the rankings and

would not have been fired at all. This case is quite

significantly distinct in this regard from Summers v. State Farm

Mutual Auto. Ins. Co. 864 F.2d 700 (10th Cir. 1988), in which an

employee's chronic pre-discrimination misconduct happened to be

uncovered during the course of litigation of his discrimination

claim. Here, the asserted "misconduct" was triggered by the

discrimination. MDHC has introduced no proof that O'Day would

have copied employee rankings and been fired for it in the

absence of the challenged promotion denials.

Even in the factual context of Summers. where misconduct

independent of the pursuit of a discrimination claim came to

light during litigation, the ab initio backpay bar MDHC proposes

unfairly assumes the early discovery which MDHC has the burden to

prove. A plaintiff's backpay period "should not terminate

prematurely unless [the defendant] proves that it would have

discovered the after-acquired evidence prior to what would

otherwise be the end of the backpay period in the absence of the

allegedly unlawful acts and [the] litigation." Wallace, 968 F.2d

at 1182. MDHC proffered no such proof in the district court.

The approach MDHC proposes would also create an unfair

8

double standard against discrimination complainants. An example

makes this clear: One employee violates a company rule on

January 1, 1990 and the violation is not discovered until

December 31, 1990, when the employee is discharged for the

violation. The employer cannot require the employee to pay back

the salary for the entire year on the ground that, if the

violation had been discovered in January, the employee would have

been discharged then; rather, the offending employee's salary

terminates as of the end of the year, on his actual discharge

date. If a second employee committed the same violation on

January 1990, was discriminatorily discharged in June, and his

violation came to light also on December 31, 1990, however,

defendant's proposed version of the after-acquired evidence rule

provides that the discrimination victim — who committed the same

infraction which was later discovered by the employer on the same

day as the first employee's infraction — loses his right to seek

backpay for the June to December period. A doctrine

systematically disfavoring charging parties in this way is

contrary to the statutory mandate of ADEA, and of federal anti-

discrimination law generally, which seeks to ensures that

discrimination victims suffer no adverse consequences from

pursuing discrimination claims. See 29 U.S.C. § 623(d) (ADEA

provision prohibiting reprisal).

Moreover, even assuming that MDHC were correct that the date

of the misconduct itself rather than the date of discovery is the

cutoff for backpay, reversal is required here because the

9

misconduct MDHC alleges in this case did not even occur until

after the challenged discriminatory promotion denials. O'Day

challenged promotions denied as early as April 1990, and did not

copy the employee rankings until June. Thus, plaintiff has a

discrimination claim and a corresponding right to seek backpay

and other relief which are not even arguably affected by the

photocopying which MDHC asserts justified the discharge. This

chronology distinguishes the facts of this case from after-

acguired evidence cases cited by MDHC which deal, for example,

with resume and application fraud. Indeed, the fact that O'Day's

promotion discrimination claims accrued prior to the alleged

misconduct distinguishes this case from Summers. where the

employee's misconduct predated the employer's discrimination.

The district court erroneously ignored O'Day's promotion claims

in granting summary judgment for MDHC, and this reason alone

reguires reversal.

The rationale for denying backpay in mixed motive cases is

that an employee who would have been fired for independent

reasons does not need backpay to restore him to where he would

have been absent discrimination; if he would have been out of a

job in any event, backpay compensation may be inappropriate.

"Simply put," federal anti-discrimination law "does not limit an

employer's freedom to make decisions for reasons that are not

unlawful." Wallace. 968 F.2d at 1174. However, MDHC advocates

what is, in effect, a doctrine of "constructive early discovery"

of nondiscriminatory reasons for discharge, applicable only to

10

charging parties. This proposal must be rejected because it

promises to place employees who violate company policies and who

also have legitimate discrimination claims in a worse position

than employees who violate policies but have no such claims.

II. RECENT CIRCUIT COURT CASES SUPPLY ADDITIONAL AUTHORITY

IN SUPPORT OF REMAND

A. This Court Should Follow The Approach of the

Eleventh Circuit in Wallace v. Dunn Construction

Co., Inc.

Since O'Day filed his initial brief, the Eleventh Circuit in

Wallace v. Dunn Construction Co.. 968 F.2d 1174, issued a lengthy

and carefully reasoned opinion repudiating the Summers doctrine

on which the district court relied. The court in Wallace stated

"we reject the Summers rule that after-acquired evidence may

effectively provide an affirmative defense to Title VII

liability." Id. at 1181. Summers "is antithetical to the

principal purpose of Title VII — to achieve equality of

employment opportunity by giving employers incentives to self

examine and self-evaluate their employment practices and to

eliminate, so far as possible, employment discrimination." Id.

at 1180 (citations and quotations omitted).4 The court in

Wallace accordingly held that after-acquired evidence of employee

misconduct may only be used to deny front pay and reinstatement,

and to limit a successful plaintiff's backpay entitlement to that

4 As MDHC itself comments, Courts consistently have

recognized the same underlying remedial purpose" for both Title

VII and the ADEA. Deft's. Br. at 7.

11

period before the defendant can prove it would have discovered

the late-emerging non-discriminatory reason for the adverse

employment action. 968 F.2d at 1182. Under Wallace. after-

acquired evidence is not a defense against liability, nor does it

eliminate entitlement to partial backpay, declaratory relief,

liquidated damages, and fees and costs where otherwise

appropriate. Id. at Id. at 1180-83.

This Circuit should reject the Summers rationale and follow

Wallace. The Court there properly recognized that Summers places

an employment discrimination plaintiff in a worse position than

if he had not been a member of a protected class:

The Summers rule does not encourage employers

to eliminate discrimination. Rather, it

invites employers to establish ludicrously

low thresholds for "legitimate" termination

and to devote fewer resources to preventing

discrimination because Summers gives them the

option to escape all liability by rummaging

through an unlawfully discharged employee's

background for flaws and then manufacturing a

"legitimate" reason for the discharge that

fits the flaws in the employee's background.

968 F.2d at 1180. The Wallace ruling, in contrast to Summers,

strikes a proper balance between the interest of the employer in

not being forced to continue the employment of an employee whose

conduct is unacceptable, and the employee's interest in not being

subjected to unlawful discrimination. It properly takes into

consideration the time lapse between the occurrence of the non-

discriminatory reason for termination and the later discovery of

that reason. It follows generally the rationale of the 1991

amendments to Title VII, and does nothing to unduly compromise

12

the legitimate interests of employers. It is clearly the more

appropriate approach to the issue of after acquired evidence of

misconduct.

B. Even Recent Cases Relying on Summers v. State Farm

Mutual Auto Ins. Co. Recognize The Right of a

Plaintiff in 0'Day's Circumstances to Obtain

Relief___________________________________________

In Smith v. General Scanning, Inc.. 876 F.2d 1315 (7th Cir.

1989), the Seventh Circuit was faced with the issue of an after

acquired defense of resume falsification in an age discrimination

case. The Smith decision makes two significant points. First,

the court recognized that it is improper to give any

consideration to after-acquired evidence at the liability stage

of a case. The Smith court rejected the argument that the after

acquired evidence prevented the Plaintiff from making a prima

facie case of discrimination:

By narrowly focusing on Smith's initial burden as it

concerned his qualifications, the district court was

distracted from the real issue in this case. At issue

is the lawfulness of Smith's termination. His resume

fraud clearly had nothing to do with that; it surfaced

only after Smith was terminated and after this suit was

commenced. Whether GSI discriminated against Smith

must be decided solely with respect to the reason given

for his discharge, namely the RIF and reorganization.

His resume fraud is, for this purpose, irrelevant.

876 F.2d at 1319. As in Smith. O'Day has presented a prima facie

case of discrimination and the district court has assumed for

purposes of its decision that discrimination occurred.

A second point made in the Smith opinion that supports

remand in this case is that proof of an after-acquired non

13

discriminatory reason for a discharge can only bar backpay from

when the reason is discovered, and not "ab initio" as MDHC

contends. The Smith court noted:

. . . Had we concluded that GSI violated the

ADEA when it terminated Smith, the question

of reinstatement and backpay liability would

arise. In that case, it would hardly make

sense to order Smith reinstated to a job

which he lied to get and from which he

properly could be discharged for that lie.

See Summers v. State Farm Mutual Automobile

Insurance Company. 864 F.2d 700, 704-05, 708

(10th Cir. 1988). The same would be true

regarding any backpay accumulation after the

fraud was discovered. (Emphasis added)

876 F.2d at 1319, n.2.

The Seventh Circuit established another important limitation

on the Summers doctrine in Reed v. Amax Coal Company, 971 F.2d

1295 (7th Cir. 1992). In defense against plaintiff's claim of

racially discriminatory discharge, the defendant pointed to a

false statement on his employment application and argued that

Summers supported summary judgment in its favor. Rejecting that

argument, the court stated:

The Summers case is not as broad as Amax

would have us believe. Summers and analogous

cases require proof that the employer would

have fired the employee, not simply that it

could have fired him. We must require

similar proof to prevent employers from

avoiding Title VII liability by pointing to

minor rule violations which may technically

subject the employee to dismissal but would

not, in fact, result in discharge.

Unlike the employer in Summers. Amax never

proved that it would have fired Reed for

lying on his application; it only proved that

it could have done so. Amax did not, for

instance, provide proof that other employees

were fired in similar circumstances. . . .

14

We, therefore, may not affirm for the reasons

given by the District Court.

971 F.2d at 1298 (citations omitted). In this case, there is no

evidence that O'Day would have copied the rankings in the absence

of MDHC's discrimination. If, however, there were such proof,

the evidence MDHC submitted might permit, but certainly would not

require, a reasonable jury to find that MDHC had authority to

fire O'Day. MDHC's evidence, however, like the evidence in Reed.

did not include any showing of what MDHC actually would have

done. The absence of any evidence regarding the actual

interpretation and application of MDHC's rules alone requires

reversal.

The Fourth Circuit, too, has addressed this issue in a

manner that counsels remand here. In contending that Smallwood

v. United Airlines. Inc.. 728 F.2d 614 (1984) (Smallwood II).

cert, denied. 469 U.S. 832 (1984), supports the decision of the

district court in this case, MDHC mischaracterizes that decision.

Deft's. Br. at 11, n.6; id. at 12, n.7. Smallwood did not

completely deny relief to the plaintiff, but rather granted

injunctive relief. Id. at 617-18. The Court denied backpay and

instatement in the job the which plaintiff had applied because it

held that the defendant proved it would not have hired the

plaintiff in any event had he not suffered hiring discrimination

and his application been fully processed.

In sum, in cases in this Circuit, see Pltf's Br. at 11-12,

15

17, as well as in the Eleventh, Seventh, and Fourth Circuits,

militate in favor of remand of this case to the district court

for determination of an appropriate remedy. Moreover, for the

reasons set forth above at 7-9, even under the rationale of

Summers and of other cases following its approach, remand in this

case is required.

III. MDHC'S CONTENTION THAT NO REMEDY IS FEASIBLE HERE IS

CONTRARY TO ADEA'S REQUIREMENT OF FULL RELIEF FOR

UNLAWFUL AGE DISCRIMINATION

MDHC suggests that, even assuming O'Day suffered unlawful

discrimination, he should receive no relief because it would be

too complicated to fashion the appropriate remedy. MDHC does not

dispute that the after-acquired evidence doctrine announced in

Summers is a doctrine not about liability but about potential

limits on remedies. Deft's. Br. at 11 (discussing denial of

remedy under Summers where defendant was presumptively liable for

discrimination). The Company defends the district court's

dismissal of plaintiff's entire case, however, by asserting that

plaintiff is not entitled to even a partial remedy, so there is

no point in determining liability. Deft's. Br. at 12-13. The

basis of MDHC's assertion that no partial remedy is warranted,

however, is simply that "piecemeal" remedies should be denied.

MDHC concedes that requiring the courts to "sift through each

available remedy under the ADEA (or Title VII) and determine the

appropriate balance between the plaintiff's and employer's

interests" is an approach that logically "might make sense" under

16

the "remedy-driven" Summers doctrine. Deft's. Br. at 11-12. The

reason that MDHC offers against such an approach is simply that

it would require a "case-by-case" approach to remedy, giving

district courts an "unenviable" task of fashioning remedies on a

fact-specific basis. Id.

Defining an appropriate remedy for discrimination, once it

is proved, is not only eminently feasible, but is the statutory

mandate. MDHC dismisses the Wallace court's success in

fashioning an appropriate remedy in the context of that case as

the result of "tortured" analysis. Deft's. Br. at 12. Such

argument by epithet, however, cannot justify the failure of the

district court in this case to acknowledge that MDHC did not

disprove 0'Day's entitlement to any remedy.

Assuming that MDHC discriminated, plaintiff is presumptively

entitled to a remedy. See. e . q. . Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody.

422 U.S. 405, 418-22 (1975). Even if MDHC partially overcomes

that presumption by proving that O'Day would have been terminated

at once when MDHC learned that he had copied the employee

rankings, several of his ADEA remedies would be unaffected by

such proof.5 Specifically, O'Day would retain at least an

5 MDHC contends that it "has established enough for a

jury, without more, to find that plaintiff would have been

terminated for his misconduct." Deft's. Br. at 22. That is

simply not true. MDHC has never suggested that plaintiff would

have copied the employee rankings had he not been

discriminatorily denied a promotion. Moreover, whether O'Day

might have been terminated does not bear on his promotion claims,

which the district court also erroneously dismissed. In any

event, in order to be entitled to summary judgment on an issue on

which it bears the burden, what MDHC would have had to prove was

(continued...)

17

entitlement to (1) backpay up to the time when he would have been

discharged based on the after-acquired evidence; (2) declaratory

relief that MDHC discriminated; (3) liquidated damages if the

discrimination was willful; (4) an injunction against future

discrimination; and (5) attorneys fees and costs.

MDHC argues that a district court has broad discretion in

selecting legal and equitable remedies so long as the relief

granted is consistent with the purposes of the ADEA. Deft's. Br.

at 8-9. This argument appears to be an attempt to shift the

standard of review on appeal from the summary judgment standard

to review for abuse of discretion. MDHC's argument turns on its

head the reasoning of Albemarle. As the Supreme Court stated:

Congress' purpose in vesting a variety of

"discretionary" powers in the courts was not to limit

appellate review of trial courts, or to invite

inconsistency or caprice, but rather to make possible

the "fashion[ing] [of] the most complete relief

possible.

420 U.S. at 421. An abuse of discretion argument is clearly

inapplicable here. The court never considered the evidence in a

full adversarial hearing, but rather ruled on summary judgment.

The well established standard of review on summary judgment is de

novo. The importance of this non-deferential standard is

underscored in cases under ADEA, where the jury has authority to 5

5(...continued)

not that a jury could have agreed with its version of the facts,

but that no reasonable jury could have disagreed. Anderson v.

Liberty Lobby. 477 U.S. 242, 250 (1986). This it has failed to

do. Contrary to MDHC's assertion, there is no requirement that

plaintiff introduce evidence to controvert MDHC's showing where

that showing is simply inadequate to meet MDHC's burden.

18

order remedies. Rose v. National Cash Register Corp., 703 F.2d

225 (6th Cir. 1983). The effect of the court's grant of summary-

judgment was to take the case from the jury, and such a decision

should be reviewed not with deference to the district court, but

with special attention to plaintiff's right to a jury, and to as

complete a remedy as possible for the discrimiantion he suffered.

IV. O'DAY'S CONDUCT IN COPYING THE EMPLOYEE RANKINGS WAS

PROTECTED ACTIVITY

The conduct which MDHC contends justifies denial of all

relief in this case not only fails to provide such justification,

but ifc itself protected conduct under the ADEA. O'Day discovered

employee rankings highly relevant to his discrimination claims,

and copied them in the reasonable belief that he needed to do so

in order to preserve them for use in prosecuting his claims. Far

from being conduct worthy of penalty, this conduct is protected.

Indeed, MDHC's assertion that it converted O'Day's "layoff"

status to "terminated" when it discovered that he had copied

these documents amounts to an admission of unlawful reprisal

under the ADEA. O'Day's photocopying is not only a wholly

invalid basis for defeating his claims, but is an illegal basis

for discharge as well.

MDHC asserts that O'Day could not have reasonably feared

that the rankings would be destroyed because he did not know

before he looked in Edwards' desk that, in addition to this own

file — which Edwards had earlier shown to him — he would also

find the rankings. Deft's. Br. at 26. However, the fact that

19

O'Day did not know of the existence of the rankings beforehand is

in no way inconsistent with his belief, once he did discover

them, that they might soon be deposited in one of the

conspicuously located MDHC shredding bins. The reasonableness of

O'Day's conduct, as well as the validity, if any, of MDHC's

contention the O'Day's conduct was disruptive to MDHC's business,

are on this record fact questions for the jury.

20

CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, and the reasons stated in

the initial Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant, Dennis O'Day,

respectfully requests that the Court reverse the decision of the

District Court and remand this matter for a trial on the merits

of O'Day's claims.

Tempe, Arizona 85282

(602) 838-4425

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

CHARLES S. RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

CORNELIA T.L. PILLARD

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellant

November 6, 1992

21

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

were

COPIES of the foregoing Reply Brief of Plaintiff-Appellant

mailed this (p day of November, 1992 to:

Tibor Nagy, Esq.

SNELL & WILMER

1500 Citibank Tower

One South Church Avenue

Suite 1500

Tucson, Arizona 85701-1612

Attorney for Defendants/Appellees

Robert J. Gregory

EEOC OFFICE OF GENERAL COUNSEL

1801 L Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20507

Robert E. Williams

Douglas S. McDowell

Ann Elizabeth Reesman

MCGUINESS & WILLIAMS

1015 Fifteenth Street, N.W.

Suite 1200

Washington,

BY