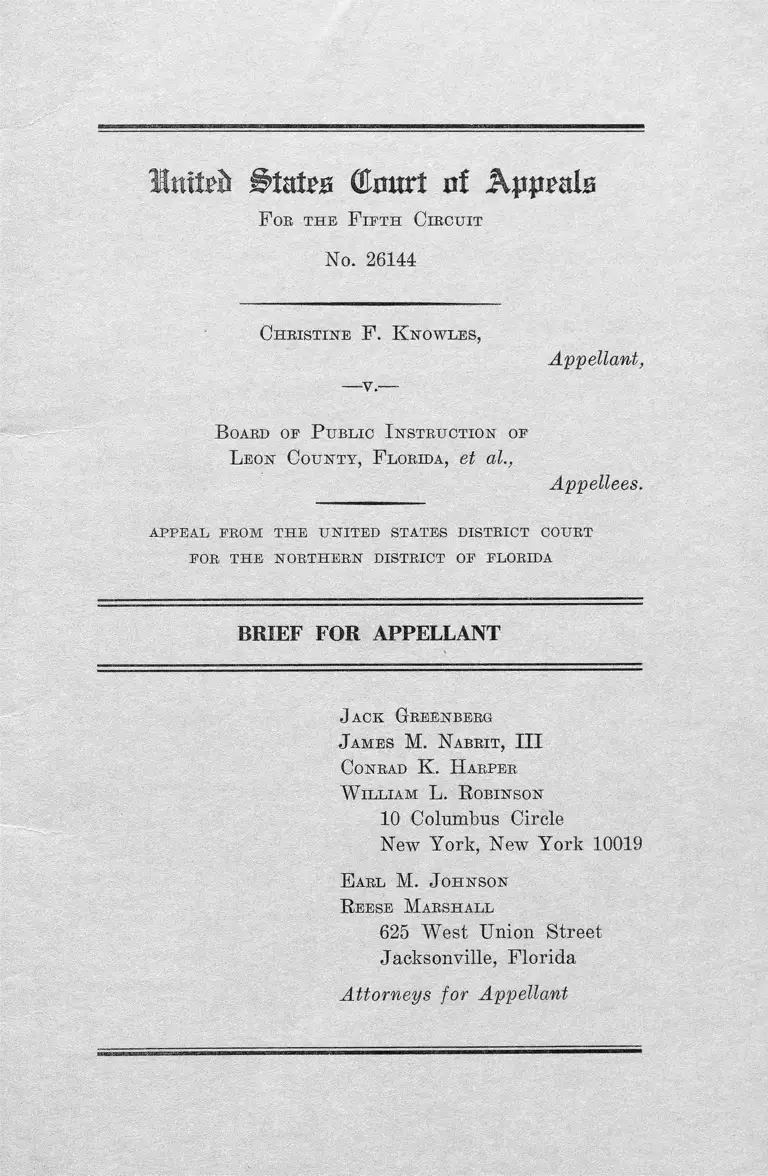

Knowles v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County, FL Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 30, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Knowles v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County, FL Brief for Appellant, 1968. 6c4a9329-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0f275bc6-6c6c-454d-8168-97b7432d4730/knowles-v-board-of-public-instruction-of-leon-county-fl-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

'MniUh S t a t e s ( t a r t n f Kppmlz

F oe the F ifth C ircuit

No. 26144

Christine F . K nowles,

Appellant,

B oard op P ublic I nstruction op

L eon County, F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

POR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Conrad K . H arper

W illiam L. R obinson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New7 York 10019

E arl M. J ohnson

R eese M arshall

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ....... ..... .......... ..... ...... ................ . 1

1. Procedural History of the Case ................. 1

2. The Board’s Employment Policies ............- 3

3. Appellant’s Attempts to Obtain Transfer ....... 5

4. The Decision of the District Court ........... ....... 9

Specifications of Error ................................... ................ 10

A rgument

I. According to the United States Constitution and

the Decisions of This Court, the Board was Re

quired to Consider the Negro Appellant’s Re

quest for Transfer to an Integrated School .... 11

1. The law in effect at the time of appellant’s

request for transfer required the board to

consider her request....... ..... ....... ..................... 11

2. The district court should have decided the

case based on the law in effect at the time

of trial ___ _____ _____ ______ _______ ____ _ 13

3. United States v. Jefferson required the board

to consider appellant’s request for transfer .... 15

4. The board was required to consider appel

lant’s request for transfer even though she

did not obtain the recommendation of a white

principal ................ ............................................. 16

PAGE

ii

II. The District Court Erred in Holding That it

Lacked Jurisdiction to Consider Appellant’s

Prayers for Reinstatement, Back Wages, Costs

and Attorneys Pees, and all Questions of Law

Respecting Her Resignation and Contractual

PAGE

Rights ................................................................... —- 18

Conclusion .................................................................................. 22

Certificate of Service....................-..................................... 23

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

American Steel Foundries v. Tri-City Central Trades,

257 U.S. 184 (1921) ................. ............................... -.... 14

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, Florida, 306 F.2d 862 (1962) ........ ............ 11,12

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Florida

v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (1964), cert, denied 377

U.S. 924 ............................................ .................... -....... - 11

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965) ................................. -...................................... .....11,21

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 249, 299-301

(1954) .................................................... -.......................... 21

Crump v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

County, Florida, 368 U.S. 278 (1961) .......... ....... . 18

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) ................—- 14

Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S. 493 (1967) ............... 18

Hurn v. Oursler, 289 U.S. 238 (1932) 21

Jackson v. Godwin, No. 25299 (5th Cir. July 23, 1968) 17

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 (1966) ....... ....... 14

Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965) .................14,15

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors Louisiana State Uni

versity, 150 F. Supp. 900 (E.E>. La.), aff’d 252 F.2d

378 (5th Cir. 1958), cert. den. 358 U.S. 819 ............... 17

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) ..................... ......... 14

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962) ______ 17

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) ....... ............. 14

Osborne v. Bank of United States, 22 U.S. (9 Wheat)

738 (1824) ......... ..... ............ ....... ...... ......... .................. 19

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348 F.2d

1010 (1965) .......... .................. ......................................... 12

Public Utilities Commission of Ohio v. United States

Fuel Gas Co., 317 U.S. 456 (1943) ___________ ____ 14

Raney v. Gould School District Board of Education,

36 L.W. 4483, 4484 (1968) ............ ........... .................. 21

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 199-200 (1965) ...........13,21

Siler v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 213 U.S.

175 (1909) ............... ................ ......... ........................ . 19

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (1965) (Singleton I) .............. . 12

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d at 869 (Singleton II) .......... ............ 12,13

Spevack v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967) ......................... . 18

IV

Clifford N. Steele, et al. v. Board of Public Instruction

PAGE

of Leon County, Florida, et al., No. 24650 ..... ......... 1, 2

Transamerica Insurance Co. v. Bed Top Metal, 384

F.2d 752, 753-754 n. 1 .................... .......... ................. 19,20

United Mine Workers v. Gibbs, 383 U.S. 715, 725

(1966) ........................................................... .................... 20

United States v. Alabama, 362 U.S. 602 (1959) ..... ..... 13

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed en banc,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert, den, sub nom

Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 389

U.S. 840 (1967) ........... ...... ...... ............. 2,13,14,15,16,17

United States v. Ramsey, 353 F.2d 650 (5th Cir. 1960) 14

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch)

103 (1801) ........... ................ ................................ ........... 14

Other Authorities:

General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the

Civil Bights Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation

of Elementary and Secondary Schools, HEW, Office

of Education, April, 1964. 45 C.F.R. §181 12

F oe the. F ifth C ircuit

No. 26144

Christine F . K nowles,

-v.—

Appellant,

B oard of P ublic I nstruction of

L eon County, F lorida, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from the dismissal of a complaint

alleging racial discrimination by the Board of Public In

struction of Leon County, Florida in the employment of

a Negro teacher, Mrs. Christine F. Knowles.

1. Procedural History of the Case

On August 19, 1966, Mrs. Christine Knowles (herein

after referred to as appellant) filed in the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Florida an

intervenor’s complaint and motion to intervene in the case

of Clifford N. Steele, et al. v. Board of Public Instruction

of Leon County, Florida, et al., a pupil desegregation case

then pending in this court. (E. 1-6, 6-7). The complaint

2

alleged, inter alia, that defendants in violation of the

United States Constitution: followed a policy of maintain

ing segregated faculties in the Leon County public schools

(R. 4 ); maintained a policy of requiring applicants for

teaching positions to obtain the recommendation of the

principal of the school where they will teach prior to

employment as a means of maintaining segregated facul

ties (R. 4 ); and refused to transfer appellant, a qualified

Negro teacher, to a predominantly white school because

of appellant’s race (R. 4). The complaint prayed that a

preliminary injunction be issued compelling defendants:

to assign appellant to a teaching position in a school at

tended predominantly by white students; to cease main

taining segregated faculties and to submit a plan to dis

establish the system of segregated faculties (R. 5-6). On

September 15, 1966, the district court entered an order

granting appellant’s motion to intervene but holding in

abeyance the motion for preliminary injunction because

the Steele case was then on appeal to this court (R. 22).

On April 12, 1967, this court dismissed the appeal,

Steele v. Board of Public Instruction of Leon County,

Florida, No. 24650, because it was clear that the district

court would enter an order conforming to the decree

entered by this court in United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), affirmed

en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967), cert. den. sub nom

Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S.

840 (1967). On May 1, 1967, the district court issued a

Jefferson decree. Section V III of the decree enjoined the

defendants from maintaining segregated faculties; but the

court did not grant any relief for the appellant.

December 1, 1967, appellant filed a motion for further

relief requesting the court to issue an order directing that:

appellant be reinstated as a teacher in the Leon County

3

school system; assigned to a school attended by predomi

nantly white students and pay appellant her back wages

(R. 23-25).

A trial was held on February 26, 1968 (R, 123) and

February 28, 1968 the district court entered an order

rendering judgment for the defendant and dismissing the

complaint, without prejudice to filing in the State courts, on

the grounds that appellant had no constitutional right to

receive a transfer to a school of her choice and the orders

of the court did not require faculty desegregation until

May 1, 1967. The court also held that appellant’s prayers

for reinstatement, back salary, costs and attorneys fees

and all questions of law respecting her resignation and

rights under her contract were matters of state law out

side its jurisdiction (E. 192-193). Appellant filed a motion

for new trial on March 7, 1968 asserting that: the court

erred in holding that it lacked jurisdiction to grant appel

lant’s prayers for reinstatement, back salary, costs and

attorneys fees; the court’s refusal to consider questions of

law relative to appellant’s resignation and contract rights

effectively precluded adducing evidence tending to show

racial discrimination (R. 193). The motion for new trial

was denied on March 8, 1968 (R. 195). Appellant filed a

notice of appeal on April 8, 1968 (R. 196).

2. The Board’s Employment Policies

During the 1964-65 school year the board maintained a

policy of assigning teachers on the basis of race (E. 141).

Superintendent Ashmore testified that:

“We followed the Florida criterion which said there

would be no integration.” (R. 141).

In the 1965-66 school year, there was no faculty integra

tion in the public schools of Leon County (E. 92, 102, 136).

4

For the 1966-67 school year, one white teacher was em

ployed at Concord, a predominantly Negro elementary

school (R. 92, 102, 137).

Applicants seeking a teaching position in the Leon County

school system first file a written application with the As

sistant Superintendent in charge of personnel, Sterling

Bryant (R. 108). Usually Mr. Bryant interviews the ap

plicant and completes a file on the applicant by acquiring

references and checking their certification (R. 108). When

vacancies occur, the assistant superintendent refers the

principals to teachers available to fill the vacancy (R. 31,

103, 108, 119-120, 141). The principal recommends one of

these teachers to the superintendent’s office. The superin

tendent submits the teacher’s name to the board and the

board approves employment of the teacher (R. 103, 141).

The board’s policy governing teacher transfers, in effect

throughout this litigation, required the teacher seeking

transfer to obtain a recommendation approving the transfer

from the respective principals, the principal of the school

where she is then teaching and the principal of the school

to which she desires transfer (R. 38, 39, 113). The recom

mendations are submitted to the superintendent who ap

proves the transfer (R. 38).

After the district court’s Jefferson decree was entered

on May 1, 1967, the board ignored its usual employment

transfer procedures in attempting to meet its affirmative

duty to disestablish faculty desegregation (R. 113). The

assistant superintendent surveyed the teachers to determine

which teachers were willing to transfer to an integrated

school (R. 114). When the survey was completed, the

assistant superintendent referred the willing teachers to

the various principals and coordinated the effort to de

segregate the faculties (R. 114-116).

5

3. Appellant’s Attempts to Obtain Transfer

Appellant was employed under continuing’ contract as a

business education teacher at the all-Negro Lincoln High

School from 1959 until August, 1966 (B. 54, 56, 164).

During the spring of 1965, at the request of her principal,

Mr. F. D. Lawrence, appellant attended a meeting with a

group of white business education teachers which resulted

in the decision to submit a proposal to the State Depart

ment of Education for a vocational office education pro

gram to be established in the business education depart

ment at Lincoln (B. 164-165). Appellant took two courses

at Florida A. & M. University to become qualified to teach

in the program (E. 165).

March 31, 1966, Mr. F. D. Lawrence received a copy of

the notice disapproving the proposal for a vocational office

education program at Lincoln High School (E. 166). A l

though the superintendent received written notice that the

proposal had been disapproved in December of 1965 (E.

52, 166), he did not inform Mr. Lawrence of the dis

approval until March 31, 1966 (E . 166); and Mr. Lawrence

informed appellant of the disapproval on the next day,

April 1, 1966 (B. 166).

Subsequent to disapproval of the Lincoln proposal, ap

pellant attended another integrated meeting of business

education teachers (E. 166). At this meeting, the county

coordinator of education informed the teachers to quickly

submit their proposals because the superintendent would

honor them on a “ first come first served” basis (E. 166).

April 26, 1966, appellant made inquiries of the State

Department of Education concerning procedures for sub

mission of project proposals and specifically the Lincoln

High School proposal (E. 47, 50, 167). April 26, 1966,

appellant also wrote the superintendent asking for his

6

comments on her letter to the State Department of Edu

cation and requesting a transfer to one of the better

equipped schools, Leon, Rickards or Lively Technical where

her skills would be employed more effectively (R. 46, 144,

167). She wrote:

“Please give me your comments and reactions to the

attached letter at your earliest convenience.

“In regards to the attached letter and in compliance

with ‘The 1966 Title VI Guidelines,’ I wish to make a

request to be transferred to one of the better equipped

schools—Leon, Rickards or Lively Technical Day Pro

gram. I feel that this transfer will enable me to bet

ter implement my training by using and working with

the proper equipment.”

July 11, 1966, the superintendent replied to appellant’s

request for comments without commenting on her request

for a transfer to a predominantly white school (R. 41-43).

During the summer, Principal Lawrence repeatedly

called appellant to determine her plans for the next school

term (R. 167). Appellant informed him that her plans

depended on hearing from the superintendent about her

request for transfer (R. 167). July 11, 1966, Mr. Lawrence

wrote the superintendent recommending appellant for a

position as teacher of Vocational Office Education at Lin

coln High School (R. 41, 168). July 21, 1966, appellant

wrote the superintendent inquiring about the status of

her request for a transfer and reiterated her belief that

such a transfer would enable her to make greater use of

her training and experience (R. 40, 168). July 22, 1966,

Superintendent Ashmore wrote appellant to inform her

that there were no plans to assign her to another school

and that it was long-standing policy to require teachers

who desire transfers to obtain recommendations approving

7

the transfer from the principals of the respective schools

(R. 38, 44, 168).

On July 25, 1966, appellant requested a recommenda

tion approving her transfer from Principal Lawrence

(R. 38, 39, 168-169), who replied that he had no objec

tions to the transfer but informed her of the Board’s

policy requiring her to obtain the recommendation of the

principal at the school to which she sought transfer (R. 37-

38, 168-169).

Initially, appellant did not write the white principals of

Leon, Lively or Rickards requesting a recommendation

for transfer because she felt that requiring her to obtain

a white principal’s recommendation was discriminatory

(R. 169-170). However, appellant later wrote the white

principals of Leon, Lively and Rickards requesting a

recommendation to their school (R. 170). She received

letters from all of them indicating that no vacancies

existed at their school and that her letter was being

referred to the Assistant Superintendent in charge of

personnel (R. 170-171).

August 19, 1966, appellant filed her complaint in this

cause alleging racial discrimination in the hiring and as

signment of teachers in Leon County (R. 1-7). August 22,

1966, appellant wrote Mr. Lawrence indicating that she

could not accept the position of vocational office education

teacher pending disposition of her complaint scheduled

for hearing in the United States District Court, Septem

ber 8, 1966 (R. 36-37). August 29, 1966, the superinten

dent wrote appellant indicating that the board expected

her to teach vocational office education during the school

year 1966-67 (R. 34-35). August 30, 1966, appellant wrote

the superintendent resigning as a teacher in the Leon

County school system pending the district court’s deck

8

sion on her application for transfer (R. 34). Her letter

stated :

“ The denial of my application for transfer to one of

the better equipped white schools is presently under

appeal to the U.S. District Court for the Northern

District of Florida. I cannot accept any position in

the public schools in Leon County before the decision

of the said court.

You are further notified of my resignation as a

teacher in the Leon County public school system pend

ing the determination of the U.S. District Court in

the above mentioned case.” (R. 34)

September 1, 1966, the superintendent wrote appellant

that the Board accepted her resignation effective as of

August 31, 1966 (R. 33). September 11, 1966, appellant

wrote the superintendent pointing out the district court’s

failure to decide her complaint on September 9 as sched

uled and requested a transfer to any school in the county

except Lincoln High School (R. 32). September 21, 1966,

the superintendent wrote appellant indicating that since

the Board had accepted her resignation and she was no

longer a part of the school system, appellant must obtain

prior to reemployment a recommendation from the princi

pal of one of the Leon County schools to fill an existing

vacancy (R. 31). October 17, 1966, appellant wrote the

superintendent informing him that the Board accepted

her temporary resignation without qualification of any

kind: She also indicated she would write principals of

the predominantly white schools requesting employment

and requested notification of any vacancy at any of their

schools (R. 29-30). October 27, 1966, the superintendent

responded that no vacancy existed in appellant’s field of

certification (R. 28-29).

9

Appellant was unemployed until the middle of Decem

ber, 1966 (R. 171). She worked at Florida A. & M. Hos

pital for two and one half months from January to March

15, 1967 (R. 171-173). Appellant was unemployed from

March 15 to April 10, 1967 (R. 173). Appellant has been

employed at the Florida State Correctional Institution (al)

from April 10, 1967 to the present (R. 171, 69).

4. The Decision of the District Court

At the close of appellant’s case, the court granted ap

pellee’s motion to dismiss from the bench (R. 187). The

court ruled that a teacher does not have a constitutional

right to request a transfer and receive favorable action

upon that request (R. 186). Appellant’s attorney pointed

out that this case involved the question of racial discrimi

nation and that the Board was at least obligated to con

sider the application for transfer to an integrated school

(R. 189). The court ruled that the orders of the district

court did not require the Board to consider teacher ap

plications for transfer to an integrated school until entry

of the Jefferson decree on May 1, 1967 (R. 190) ; and the

district court held that the decisional law of this court

in effect at the time appellant requested transfer ex

pressly exempted the Board from the obligation to con

sider teacher applications for transfer to an integrated

school (R. 190). Early in the trial, the district court cited

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, Florida, 306 F.2d 862 (1962), as the decision

exempting the Board from the duty to desegregate facul

ties (R. 139).

The court, also from the bench, granted appellee’s mo

tion to strike the prayer for an injunction requiring the

Board to cease employing teachers on the basis of race

and submit a plan for desegregation of faculties because

that relief was ordered in the Jefferson decree (R. 183).

10

February 28, 1968, the district court, entered an order

dismissing the complaint because appellant had no con

stitutional right to teach at a school of her choice and

faculty integration was not required before entry of the

Jefferson decree on May 1, 1967 (R. 192). The order

also held that “ the other matters raised by [appellant’s]

pleadings including her prayer for reinstatement, pay

ment of back salary, costs and attorneys fees, and all

questions of law respecting her resignation and rights

under her contract of employment are matters outside”

its jurisdiction (R. 192-193).

Specifications of Error

1. The district court erred in dismissing the complaint

of the Negro appellant on the grounds that:

a) faculty segregation was permissible at the time of

appellant’s request for transfer to a white school;

b) a Negro teacher has no constitutional right to re

ceive consideration of her request for transfer

from an all-Negro to an all-white or integrated

school.

2. The district court erred in holding that appellant’s

prayers for reinstatement, payment of back salary, costs

and attorneys fees and all questions of law respecting her

resignation were matters of state law outside its jurisdic

tion.

11

A R G U M E N T

I.

According to the United States Constitution and the

Decisions of This Court, the Board was Required to

Consider the Negro Appellant’ s Request for Transfer to

an Integrated School.

1. The law in effect at the time of appellant’ s request for

transfer required the board to consider her request

The court dismissed the complaint, in part, because

in its view the law in effect at the time of appellant’s

request for transfer did not require the board to deseg

regate the faculty. The court relied on this court’s deci

sion in Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Es

cambia County, Florida, 306 F.2d 862 (1962) as permitting

the district court to defer ruling on the issue of faculty

desegregation (R. 139).

Augustus did express the view that the district court

could in its discretion postpone consideration and deter

mination of the faculty desegregation issues as presented

by Negro pupils. However, decisions of this court and

the Supreme Court had completely undercut Augustus

at the time appellant requested transfer in April of 1966.

In Board of Public Instruction of Duval County, Florida

v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (1964), cert, denied 377 TJ.S. 924,

this court affirmed an order prohibiting assignment of

teachers on a segregated basis. In Bradley v. School

Board of Richmond, 382 TJ.S. 103 (1965), the Supreme

Court reviewed a decision holding, like Augustus, that

the district court could defer ruling on faculty deseg

regation until segregation in the assignment of pupils

had been eliminated. The court summarily remanded the

case to the district court holding that it was improper

for the court to approve a desegregation plan without

12

considering the impact of faculty assignment on a racial

basis. The Court stated:

“We hold that petitioners were entitled to such full

evidentiary hearings upon their contention. There is

no merit to the suggestion that the relation between

faculty allocation on an alleged racial basis and the

adequacy of the desegregation plans is entirely specu

lative. Nor can we perceive any reason for post

poning these hearings: Each plan had been in opera

tion for at least one academic year; these suits had

been pending for several years; and more than a

decade has passed since we directed the desegrega

tion of public school faculties ‘with all deliberate

speed,’ Brown v. Board of Education. . . . Delays

in desegregating school systems are no longer toler

able.” 382 U.S. at 105.

The board was also required to put an end to faculty

segregation under this court’s decisions in Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d

729 (1965) (Singleton I), 355 F.2d 865 (1966) (Single-

ton I I ) ; Price v. Denison Independent School District,

348 F.2d 1010 (1965). Singleton I and Price adopted the

standards established by H.E.W. as the minimum stan

dards for school desegregation.1 In Singleton II, this

court required further action toward faculty desegrega

tion than merely holding joint faculty meetings and a

joint inservice program.

Finally it must be noted that in this case the complaint

alleging faculty assignment on the basis of race was filed

by an individual Negro teacher. While Augustus and

1 General Statement of Policies Under Title VI of the Civil Eights

Act of 1964 Respecting Desegregation of Elementary and Secondary

Schools, HEW, Office of Education, April, 1964. 45 C.F.R. §181.

13

other cases held that the district court could postpone

consideration of the broad question of faculty desegrega

tion presented as part of a pupil desegregation case, it

has never been held that the district court could avoid

ruling on a complaint brought by an individual Negro

teacher alleging that racial considerations controlled her

teaching assignment. It seems patently clear that the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion and Section 601 of the 1964 Civil Eights Act prohibit

the board from refusing to consider because of race an

individual Negro teacher’s request for transfer to a predom

inantly white school. Cf. Rogers v. Paid, 382 U.S. 198,

199-200 (1965); Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 355 F.2d at 869, holding that Negro children

in still segregated grades in Negro schools had an ab

solute right, as individuals to transfer to schools from

which they were excluded because of their race.

2. The district court should have decided the case based on

the law in effect at the time of trial

The district court dismissed the complaint partially on

the ground that this court’s decision in United States v.

Jefferson was not controlling (R. 192). In reaching this

novel conclusion unsupported by any authority, the dis

trict court reasoned that the filing of the complaint in

August, 1966, four months before the Jefferson panel

opinion (December 29, 1966) and seven months before

the Jefferson en banc opinion (March 29, 1967) was not

timely to invoke Jefferson’s requirements (R. 139, 162,

190)—notwithstanding the fact that trial was had in Feb

ruary, 1968, almost a year after the en banc opinion in

Jefferson.

It is firmly established that appellate courts must apply

the law as it is at the time of their decision, rather than.

14

the law in effect at the time the complaint was filed or

at the time of the decision below. Linkletter v. Walker,

381 U.S. 618, 627 text and n. 11 (1965); United States

v. Alabama, 362 U.S. 602 (1959); Public Utilities Com

mission of Ohio v. United States Fuel Gas Co,, 317 U.S.

456 (1943); American Steel Foundries v. Tri-City Central

Trades, 257 U.S. 184 (1921); United States v. Ramsey,

353 F.2d 650 (5th Cir. 1960); United States v. Schooner

Peggy, 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 103 (1801). It follows that

district courts must apply the law in effect at the time

of the trial, rather than the law in effect at the time the

complaint was filed or at the time the alleged transgres

sion occurred.

In holding Jefferson inapplicable to events which oc

curred before the decision was announced, the district

court made an implicit analogy to recent decisions of the

Supreme Court holding several of its earlier criminal law

decisions to be non-retroaetive. The Supreme Court, how

ever, has never accepted the notion that the applicability

of new rulings should depend on when the facts occurred.

See, Linkeletter v. Walker, swpra, holding Mapp v. Ohio,

367 U.S. 643 (1961) non-retroactive and restricting its

applicability to trial after the Mapp decision; Johnson

v. New Jersey, 384 U.S. 719 (1966) holding Escobedo v.

Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964) and Miranda v. Arizona, 384

U.S. 436 (1966) non-retroactive and restricting their ap

plicability to cases in which the trial began after the deci

sions were announced. Thus, even under the most restric

tive statement of the non-retroactivity principle accepted

by the Supreme Court to date, in Johnson, the Jefferson

decision would apply to the present case. In Linkeletter

the Supreme; Court, unlike the district court here, specif

ically rejected the suggestion that the new ruling should

apply as of the date on which the Mapp facts occurred:

15

“Nor can we accept the contention of petitioner that

the Mapp rule should date from the day of the seizure

there, rather than that of the judgment of this court.

The date of the seizure in Mapp has no legal signif

icance. It was the judgment of this court that changed

the rule and the date of that opinion is the crucial

date. In the light of the cases of this court this is

the better cutoff time.” See United States v. Schooner

Peggy, supra. 381 U.S. at 639.

3. United States v. Jefferson required the board to consider

appellant’s request for transfer

In United States v. Jefferson, this panel carefully ana

lyzed the legislative history of Section 604 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and concluded that Section 604 does

not exempt school boards from the obligation to desegre

gate faculties under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

court noted that:

“Faculty integration is essential to student desegrega

tion. To the extent that teacher discrimination jeop

ardizes the success of desegregation, it is unlawful

wholly aside from its effect upon individual teachers.”

372 F.2d at 383.

The panel also specified the constitutional requirements

for faculty desegregation including the right of individual

teachers to be free from discrimination in their employ

ment. 372 F.2d 886, n. 104. In this regard the law of

the Fifth Circuit is the same as that of the Fourth and

Eighth Circuits. Indeed the panel in Jefferson relied on

prior decisions of the Fourth and Eighth Circuits in con

cluding that individual teachers have a constitutional right

to be free from racial discrimination in their employment.

372 F.2d 884-886.

16

In the model decree attached to the Jefferson opinions,

the court directed that specific steps be taken with regard

to teacher desegregation which would require the board

to consider appellant’s request for transfer. In Section

V III of the decree, the court ordered:

F aculty and S taff

(a) Faculty Employment. Race or color shall not be

a factor in the hiring, assignment, reassignment, pro

motion, demotion, or dismissal of teachers and other

professional staff members, including student teachers,

except that race may be taken into account for the

purpose of counteracting or correcting the effect of

the segregated assignment of faculty and staff in the

dual system. . . .

(b) Dismissals. Teachers and other professional staff

members may not be discriminatorily assigned, dis

missed, demoted, or passed over for retention, promo

tion or rehiring on the ground of race or color. . . .

372 F.2d at 900, 380 F.2d at 394 (emphasis added).

4. The hoard was required to consider appellant’s request

for transfer even though she did not obtain the recom

mendation of a white principal

As noted in the statement of the case, the superintendent

informed appellant shortly before school opened that she

must obtain the recommendation of the principal of the

school to which she desired a transfer. Appellant ad

mitted at trial that initially she did not attempt to obtain

the recommendation of one of the white principals. Thus

we must consider whether the board was obligated to

consider appellant’s application for transfer despite her

failure to obtain a recommendation from one of the white

principals.

This court has on several occasions struck down rules

and regulations which on their face appear to be non-

discriminatory but which in practice and effect place a

heavy burden on Negroes and not on whites, thus oper

ating in a racially discriminatory manner. Jackson v.

Godivin, No. 25299 (5th Cir. July 23, 1968) and cases cited

therein; Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962);

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors Louisiana State Univer

sity, 150 F. Supp. 900 (E.D. La.), aff’d 252 F.2d 378 (5tli

Cir. 1958), cert. den. 358 U.S. 819.

In Meredith v. Fair, this court took judicial notice of

Mississippi’s policy of maintaining segregation in its

schools and colleges. The court then held the University

of Mississippi’s requirement that each applicant for ad

mission obtain alumni certificates of recommendation de

nied Negro applicants their equal protection of the law

because it placed a heavy burden on qualified Negro

students and no burden on qualified white students. In

the present case, the superintendent admitted that the

board followed an official policy of maintaining segre

gated faculties during the 1964-65 school year; there was

no faculty desegregation in the 1965-66 school year. In

this context, the rule requiring appellant to obtain the

recommendation of a white principal before considering

her request for transfer obviously imposed a heavy burden

on the Negro appellant not faced by whites. A white

principal would have to go contrary to the traditional

policy of segregated faculties and perhaps expose himself

to reprisals in approving appellant’s transfer to his school.

In this regard, it is significant that the superintendent

modified the policy of requiring recommendations in com

mencing the desegregation of faculties pursuant to Jeffer

son. The policy requiring appellant to obtain the prior

18

recommendation of a white principal denied appellant equal

protection of the law.

Nor can the board be permitted to defeat appellant’s

constitutional rights by asserting that she is no longer

a part of the school system. Appellant submitted a clearly

conditional resignation and it was accepted by the board

without qualification. Gf., Garrity v. New Jersey, 385 U.S.

493 (1967); Spevach v. Klein, 385 U.S. 511 (1967); Crump

v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County, Florida,

368 U.S. 278 (1961).

II.

The District Court Erred in Holding That it Lacked

Jurisdiction to Consider Appellant’ s Prayers for Rein

statement, Back Wages, Costs and Attorneys Fees, and

all Questions o f Law Respecting Her Resignation and

Contractual Rights.

The distinct court erroneously assumed that it had no

jurisdiction to decide appellant’s claims for reinstatement,

back wages, costs and attorneys fees (R. 192-93). The

court reasoned, in ruling from the bench, as follows:

“ there are other issues here that have to do with the

contract, a teacher’s contract, continuing from ’59

on down, all having to do with tenure or whether the

resignation was conditional or final or tentative, having

to do with matters of pay, and all of those things.

Everyone of those matters are strictly and solely

within the purview of the State Courts of Florida.

Federal Courts are not set up for it, it can’t be, and

won’t be, to solve those kind of individual contractual

relationships. It is an entirely different aspect of the

case.” (R. 186).

19

In its written order dismissing appellant’s complaint with

out prejudice to her right to proceed in state courts, the

court held as “ outside [its] jurisdiction,” appellant’s

“prayer for reinstatement, payment of back salary, costs

and attorneys fees, and all questions of law respecting her

resignation and rights under her contract of employment.”

(R. 192-193).

The district court wholly misapprehended its duty under

controlling decisions of this court and the Supreme Court

by dismissing appellant’s claims. The district court failed

to recognize that its jurisdiction necessarily extends to

all aspects of this case because only the federal cause of

action—racially motivated failure to transfer a Negro

teacher to a white school—was involved. The doctrine

enunciating this view of federal jurisdiction was estab

lished as long ago as Osborne v. Bank of United States,

22 U.S. (9 Wheat) 738 (1824), and affirmed in Siler v.

Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 213 U.S. 175 (1909).

This court recently emphasized the broad reach of federal

jurisdiction, in an analogous situation by noting, in Trans-

aw,erica Insurance Co. v. Red Top Metal, 384 F.2d 752,

753-754 n. 1, that:

The claim based on supplying labor material and the

claim for attorney’s fees are not separate grounds

for the same cause of action; not “ different avenues

seeking to reach the same end * * * alternative theories

of recovery for a single wrong” . The claim for at

torney’s fees is one ingredient of the supplier’s claim

for protection of his statutory right under the Miller

Act.

Jurisdiction admittedly attached when suit was filed

on the Miller Act bond. The district court therefore

continued to have jurisdiction, regardless of the dis

20

position of the labor-and-material element of the

claim. Even, if it be assumed that the right, to at

torneys’ fees is state-created and severable from the

principal claim, the district court would have jurisdic

tion to decide the question. “ The Federal questions

* * * gave the circuit court jurisdiction, and, having

properly obtained it, that court had the right to decide

all the questions in the case, even though it decided

the Federal questions adversely to the party raising

them, or even if it omitted to decide them at all, but

decided the case on local or state questions only.”

Siler v. Louisville & Nashville Railroad Co., 1909,

213 U.S. 175, 29 S. Ct. 451, 53 L.Ed. 753. See Osborne

v. Bank of United States, 1824, 9 Wheat 738, 6 L.Ed.

204, 384 F.2d at 754 n. 1.

Furthermore, even assuming appellant’s claim for rein

statement and various monetary awards were affected by

or subject to state law, the doctrine of pendent jurisdiction

vests power in district courts to decide state law claims as

a matter of federal constitutional law. The Supreme Court

recently made this clear in United Mine Workers v. Gibbs,

383 U.S. 715, 725 (1966), where it held:

“ Pendent jurisdiction, in the sense of judicial power,

exists whenever there is a claim ‘arising under [the]

Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and

Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their

Authority . . . ,’ US Const, Art III, §2, and the rela

tionship between that claim and the state claim permits

the conclusion that the entire action before the court

comprises but one constitutional ‘case.’ The federal

claim must have substance sufficient to confer subject

matter jurisdiction on the court. Levering & Garri gues

Co. v. Morrin, 289 US 103, 77 L.Ed. 1062, 53 S. Ct.

21

549. The state and federal claims must derive from a

common nucleus of operative fact. But if, considered

without regard to their federal or state character, a

plaintiff’s claims are such that he would ordinarily

be expected to try them all in one judicial proceeding,

then, assuming substantiality of the federal issues

there is power in federal courts to hear the whole.”

383 U.S. at 725 (footnotes omitted).

The district court’s failure to accord appellant a hearing

on claims deemed state lawT issues deprived her of a federal

forum for vindication in contravention of Gibbs and Hum

v. Oursler, 289 U.S. 238 (1932). Since the rights of pupils,

to desegregation include faculty desegregation, Rogers v.

Paul, supra, and Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

supra, this refusal is all the more unjustified in light of the

requirement that district courts retain, jurisdiction of school

desegregation cases until the dual system has been dis

established, Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 249,

299-301 (1954); Raney v. Gould School District Board of

Education, 36 L.W. 4483, 4484 (1968).

22

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, the Order entered by

the district court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Conrad K. H arper

W illiam L. R obinson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E arl M. J ohnson

R eese Marshall

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

Attorneys for Appellant

23

Certificate of Service

This is to certify that on the 30th day of August, 1968

I served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellant upon

C. Graham Oarothers, Esq. of Ausley, Ausley, McMullen,

Michaels, McG-eh.ee & Carothers, Post Office Box 391, Talla

hassee, Florida, by mailing a copy thereof to him at the

above address via United States mail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Appellant

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C.«gi!S»»219