United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Consolidated Brief on Behalf of Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 14, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education Consolidated Brief on Behalf of Appellees, 1966. 383d209a-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0f4fb5af-5816-4166-a780-4efae151e350/united-states-v-jefferson-county-board-of-education-consolidated-brief-on-behalf-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

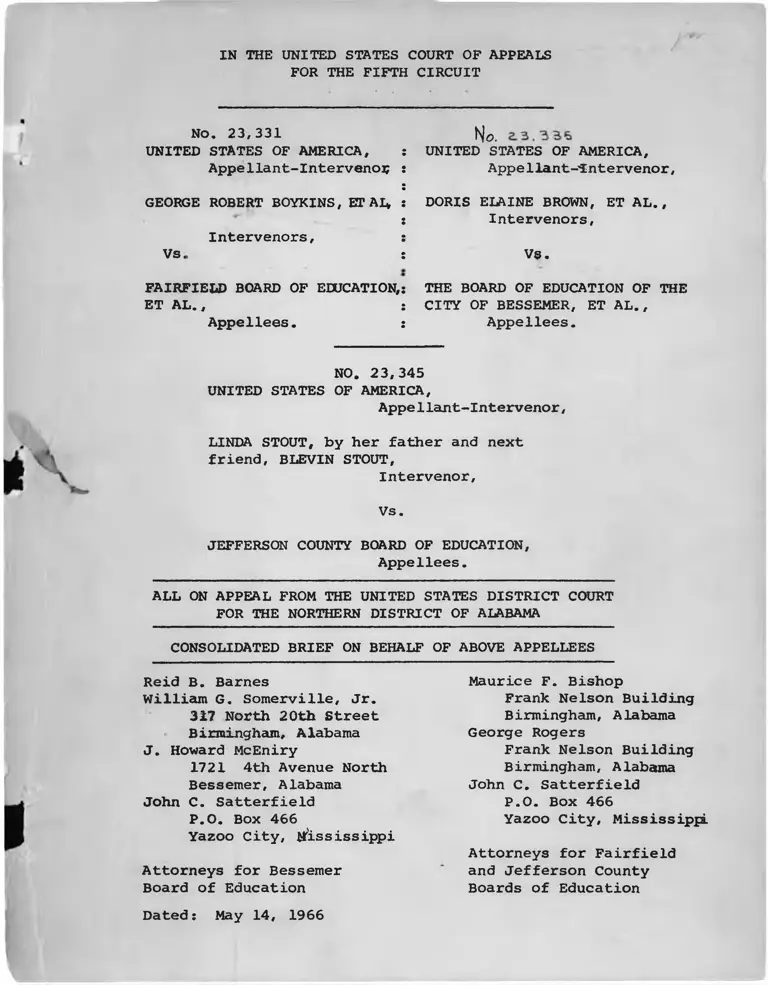

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23,331

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

AppelIant-Intervenou

GEORGE ROBERT BOYKINS, ET AI*

Intervenors,

Vs.

No.UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-'Intervenor,

DORIS ELAINE BROWN, ET AL.,

Intervenors,

Vs.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF EDUCATION,:

ET AL., :

Appellees. :

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF BESSEMER, ET AL.,

Appellees.

NO. 23,345

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appe1lant-Intervenor,

LINDA STOUT, by her father and next

friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Intervenor,

V s .

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Appellees.

ALL ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

CONSOLIDATED BRIEF ON BEHALF OF ABOVE APPELLEES

Reid B. Barnes

Willieun G. Somerville, Jr.

3i7 North 20th Street

Birmingham, Alabama

J. Howard McEniry

1721 4th Avenue North

Bessemer, Alabama

John C. Satterfield

P.O. Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi

Attorneys for Bessemer

Board of Education

Maurice F. Bishop

Frank Nelson Building

Birmingham, Alabama

George Rogers

Frank Nelson Building

Birmingham, Alabama

John C, Satterfield

P.O. Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi

Attorneys for Fairfield

and Jefferson County

Boards of Education

Dated; May 14, 1966

INDEX

\

*

4

STATEMENT OF THE CASES.................................... 3

Jefferson County Board of Education (No, 23345)...... 3

Fairfield Board of Education (No. 23331)....... ..... 11

Bessemer Board of Education (No. 23335).............. 16

ARGUMENT

A. RESPONSE TO GOVERNMENT'S ARGUMENT THAT THE PLANS

RETAIN RACIAL ASSIGNMENTS OF STUDENTS IN DESEGRE

GATED GRADES.............. 21

B. THE PLANS CONTAIN SUFFICIENT DETAILS AND PRESCRIBE

REASONABLE NOTICE..................................... 38

C. RESPONSE TO PART C OF GOVERNMENT'S BRIEF...............40

1. Necessity or Propriety in Bessemer Desegrega

tion Plan of Provision to Eliminate Inferiority

of Traditionally Negro Schools...................... 40

2. Comparative Condition of Former White and Negro

Schools in the Jefferson County and Fairfield

Systems............................................ 64

D. RESPONSE TO GOVERNMENT’S ARGUMENT THAT THE PLANS

PAIL TO CONTAIN PROVISIONS DESIGNED TO ELIMINATE

RACIAL SEGREGATION OF FACULTY AND STAFF...................69 ̂

E. RESPONSE TO GOVERNMENT'S ARGUMENT THAT THE PLANS

FAIL TO GUARANTEE TO STUDENTS WHO TRANSFER THAT

THERE WILL BE NO RACIAL DISCRIMINATION OR SEGRE

GATION IN SERVICES, ACTIVITIES AND PROGRAMS, PRO

VIDED SPONSORED BY OR AFFILIATED WITH THE SCHOOL

SYSTEM................................................ 72

F. RESPONSE TO ARGUMENT OF UNITED STATES THAT THE

PLANS SHOULD CONTAIN PROVISIONS ALLOWING NEGRO

STUDENTS IN NON-SEGREGATED GRADES TO TRANSFER TO

PREVIOUSLY WHITE SCHOOLS ............................. 73

GENERAL RESPONSE TO QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE EXTENT

TO WHICH THE COURTS SHOULD RELY UPON HEW GUIDELINES

AND POLICIES.............................................. 75

1. The 1966 Guidelines not only exceed the au

thority granted in the Act but are contrary

to its provisions and to constitutional in

tent expressed in the Act................ ,77

2. Legal nature of the "Guidelines".................. 83

3. Definition of terms utilized by Department

of Health, Education and Welfare and Depart-

ment of Justice................................... 84

The 1966 Guidelines and their adoption by

this Court would result in destruction of

generally accepted constitutional principles

applicable to desegregation of schools........... 87

The power of the Department of Health,Educa

tion and Welfare and the Commissioner of Edu

cation arise from Title VI construed in con

junction with Title rv of the Act................ 95

A

IF THE 1966 GUIDELINES ARE ADOPTED BY THE COURT AND

MADE JUDICIALLY EFFECTIVE, OR ARE RELIED UPON OR GIVEN

WEIGHT BY THE COURT IN DETERMINING PENDING AND FUTURE

CASES,THE COURT WILL THEREBY OVERRULE OR MATERIALLY

ALTER MANY OF ITS DECISIONS ENUNCIATING THE CONSTITU

TIONAL PRINCIPLES APPLICABLE TO DESEGREGATION OF

SCHOOLS.................................................. 99

1. If the 1966 Guidelines are judicially enforced

compulsory integration will be substituted for

desegregation......... 101

2. The 1966 Guidelines are designed to and will

result in the destruction of all "freedom of

choice" plans of desegregation.................. 107

3. Judicial enforcement of the 1966 Guidelines

would destroy the constitutional right of

school boards to administer their schools...... ..110

4. Enforcement of the 1966 Guidelines would

overrule decisions recognizing the duties

and responsibilities of school boards and

District Courts in violation of the express

provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964....... 112

5. The 1966 Guidelines by both affirmative and

negative provisions require compulsory trans

fer of students under "freedom of choice"

plans contrary to the Act and constitutional

principles...................................... 119

6. The immediate compulsory integration of facul

ty and school employees required by the 1966

Guidelines is not authorized by the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and is contrary to court

decisions....................................... 122

7. The 1966 Guidelines would require overruling

or materially altering decisions of this

and other courts................................ 12 5

INSOFAR AS THE 1966 GUIDELINES EXCEED AUTHORITY UNDER

THE ACT, THEY ARE VOID. INSOFAR AS THEY ARE WITHIN

THE ACT'S AUTHORITY, THEY HAVE NO MORE DIGNITY OR LEGAL

EFFECT THAN AN ADMINISTRATIVE RULING....*............... 126

11

\

A

i

TABLE OF CASES AND AUTHORITIES

CASES :

Armstrong v. Board of Education

of Birmingham

323 F.2d 333 (5th Cir.1963).............. 28, 29, 32, 74, 102

Armstrong v. Board of Education

of Birmingham

333 F.2d 47 (5th Cir. 1964).......... 2, 3, 25, 28, 29, 30, 32

Augustus V. Escambia County

306 F.2d 862 (5th Cir. 1962)......................... 107, 122

Avery v. Wichita Falls Ind.

School Dist.

241 F.2d 330 (5th Cir. 1957).............................. 103

Bivins V. Board of Public Education

and Orphanage for Bibb County

342 F.2d 229 (5th Cir. 1965).............................. 108

Blatt Co. V. United States

305 U.S. 367, 83 L.Ed.l67 (1938)......................... 134

Boson V. Rippy,

285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960)............................... 102

Bradley v. School Board of City

of Richmond

382 U.S. 103, 15 L.Ed.2d 187 (1965)............. 69, 121, 123

Brov?n V. Board of Education of Topeka

347 U.S. 294 (1954).......................................74

Brov>n V. Board of Education of Topeka

349 U.S. 294 (1955),...................................... 112

Calhoun v. Latimer

321 F.2d 302 (5th Cir.1963)................ 27, 107, 111, 114

Calhoun v. Latimer

377 U.S. 263 (1964).................................. 61, 114

Chattanooga Auto Club v. Commissioner

182 F.2d 551 (6th Cir. 1950).............................. 132

Cooper V. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1 (1958)........................................113

iii

Davis V, Board of School Conun*rs

of Mobile

333 F,2d 53 (5th Cir.1964)............................... 117

Dodson V, School Board of City

of Charlottesville

289 F.2d 439 (4th Cir.,1961)............................. 117

Goss V. Board of Education of

Knoxville

373 U.S. 783 (1963)........................ 61, 109, 114, 118

Hackett v. Coniinissioner

159 F.2d 121 (1st Cir.1946).............................. 131

Helverinq v. Edison Bros, Stores, Inc.

133 F.2d 575 (8th Cir.1943).............................. 134

Kemp V. Beasley

352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir.1965)........................... 21, 129

Lockett V. Board of Education of

Muscogee County

342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir.1965)............ 21, 25, 108, 116, 123

Manhattan G.E, Company v. Conanissioner

297 U.S. 129............... 133

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada

305 US. 337 (1938).........................................51

Price V. Denison Independent School

District

348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir.1965).................. 6, 16, 22, 116

Rogers v. Paul

382 U.S. 198, 15 L.Ed.2d 265 (1965).......... 55, 61, 73, 123

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board

of Education

162 F.Supp.372 (N.D. Ala.1958),

Aff'd. 358 U.S. 101.........................................30

Singleton v. Jackson Separate

Municipal School District

348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.1965)..................... 3, 6, 16, 22

Singleton v. Jackson Separate

Municipal School District 22, 23, 27,

355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.1964)......... 30, 39, 70, 73, 120, 128

iv

Stell V, Savannah Chatham County

Board of Education

333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir.1964)...... 2, 25, 26, 27, 38, 107, 117

United States v, Bennett

186 F,2d 407 (5th Cir.1951)............................... 131

United States v, Higinson

238 F.2d 439 (1st Cir.1956)............................... 133

U.S. V. Lov;ndes County Board of

Education

Civil Action No, 2328-N (M.D.Ala. 1966).................... 33

U.S, V, Mississippi Chemical Corp,

326 F.2d 569 (5th Cir.1964),.............................. 130

Watson V. Memphis

373 U.S. 526............................................. 114

^STATUTES:

20 U.S.C. 11-15, 16-28.................................... 36

20 U.S.C. 15i-15q, 15aa-15jj, 15aaa-15ggg................... 36

20 U.S.C. 30-34........................................... 37

Title 52, §61(4), Ala,Code of 1940 (Recomp.1958)...... 30, 74

42 U.S.C. §2000(h) (2) (24-29)...............................11

* Various sections of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 are cited

and discussed throughout the brief. Because of the frequency

of citation of these provisions, they are not contained in the

table of statutes.

V,

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 23,331

UNITED STATES OF AI^RICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

GEORGE ROBERT BOYKINS,

ET AL.,

Interveners,

vs.

FAIRFIELD BOARD OF

EDUCATION, ET AL.,

Appellees.

NO. 23,335

UNITED STAiES OF AMERICA,

Appellant-Intervenor,

DORIS ELAINE BROWN, ET AL.,

Interveners,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

CITY OF BESSEMER, ET AL.,

Appellees.

NO. 23,345

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appe 11 an t-I nte rven er,

LINDA STOUT, by her father and next

friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Intervener,

vs.

JEFFERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Appellees.

ALL ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

CONSOLIDATED BRIEF ON BEHALF OF ABOVE APPELLEES

PREFATORY STATEMENT

The entire argioment and approach of the negre

plaintiffs and the government is directed to the assumed in

dolence, and not to the proven industry of this Court. They

urge that the "multifarious local difficulties" and "variety

of obstacles incident to the transition from segregation to

integration should be surrendered by the Court to the United

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW), and,

with that abdication of judicial power, they suggest the Court

may avoid, and perhaps forget the problems.

They seek to substitute compulsion for freedom, and

direction for choice. They would have this Court embark upon

an era of compulsory integration which is just as unconstitu-

i/tional and discriminatory as compulsory segregation.

2/These appeals relate to three of the four largest

school systems in Jefferson County. The District Court ex

pressed the opinion that the systems should, and all have

followed substantially identical general plans for desegre

gation .

This brief is filed on behalf of the school boards of

i/ In Stell V. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education

(5th Cir. 1964), 333 F. 2d 55, 59, the court took occasion

to note that:

"No court has required a 'compulsory racially inte

grated school system to meet the constitutional man

date that there be no discrimination on the basis of

race in the operation of the public schools. See Evers

V. Jackson Municipal Separate School District (5th Cir.

1964) 328 F. 2d 408, and cases there cited. The inter

diction is against enforced racial segregation.’"

2/ Birmingham being the other. Its plan for desegrega

tion has been before this Court in Armstrong v.

Board of Education (5th Cir. 1964), 333 F. 2d 47.

- 2-

Jefferson County (No. 23,345), Bessemer (No. 23,335) and

Fairfield (No. 23,331) which serve contiguous areas in Jeffer

son County, Alabama. Their plans are substantially identical

with and "track" the grade designation directions of this

Court in Singleton v.Jackson Municipal Separate School

District (5th Cir. 1965), 348 F. 2d 729, and Price v. Denison

Independent School District (5th Cir. 1965) 348 F. 2d 1010.

The government brief is supplemented by four volumes

of appendices, the last of which (IV) contains a suggested form

of decree which the government asks this Court to make applic

able to all desegregation cases in this Circuit, without re

gard to, and in violation of the prior recognition by this

Court that:

" . . . the long-standing order of responsi

bility is 'first the school authorities,

then the local district court, and lastly

the appellate courts.' Ri.ppv v. Borders

(5th Cir. 1957), 250 F. 2d 590, 693." 3/

For convenience of the Court, this brief generally

will follow the format of the brief filed on behalf of the

government.

The Jefferson County Board of Edu.cation Case -

______________No. 23.345______________________

STAj’̂ jMENT OF TOE CA3S

This is a class action filed on June 4, 1965, by

one negro student through her father against the elected

^ From Armstrong v. Board of Education of the City of

Birmingham. 323 F. 2d 333, 337.

-3-

members of the Jefferson County Board of Education (School

Board) seeking a preliminary and permanent injunction frc»n re

quiring segregation of the races in any county school and to

require the Board to make arrangements for the admission of

students to such schools on a racially non-discriminatory

4/basis (9-20) School Board filed a verified

answer on June 22, 1965 (20-22) and by agreement the case

was submitted for final injunctive relief (77) on the complaint

and verified answer, the testimony of Dr. Kermit Johnson,

superintendent of schools, and exhibits thereto. The District

Court noted (25);

"... the evidence is undisputed that no

application has ever been filed seeking the

transfer of a Negro pupil to any school with

in the system attended by white pupils, as

authorized by the Alabama Sc.Jiool Placement

Law, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, in its opinion ordering the issuance

of an interlocutory injunction in Armstrong,

et â l. V. M . of Ed., Birm.. Ala.. et al..

323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963), held: ‘The

burden of initiating desegretation does not

rest on Negro children or parents or on

whites, but on the School Board.*..."

The District Court enjoined the School Board from requiring

segregation of the races in any school under their supearvision

and ordered them to submit a desegregation plan.

4/ Figures in parenthesis throughout this brief refer to

transcript pages of the respective case unless other

wise specifically indicated.

-4-

( 1)

The Original Desegregation Plan

Pursuant to said order the School Board on June 30,

1965, filed a detailed plan providing for desegregation of

the (30-37):

First, Ninth, Eleventh and Twelfth Grades

for the 1965 - 1966 school year.

Second, Third, Eighth and Tenth Grades

for the 1966 - 1967 school year.

Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Grades for

the 1967-1968 school year.

All students entering school for the first time in September,

1965, and thereafter would be assigned to the school of their

choice. Widespread publicity was given to the plan.

On July 9, 1965, the single negro plaintiff filed ob

jections to the plan. On July 12, 1965, the United States

filed its motion for leave to intervene as a party plaintiff.

On the same date the motion was granted (42-43) and the Govern

ment filed objections to the plan for desegregation (44-45).

The School Board responded to all objections and outlined in

detail the reasons which prompted each part of the plan (46-

51), further noting that fifteen negro students had filed

applications to transfer to formerly all v;hite schools of which

fourteen were approved and one denied for admittedly proper

reasons without regard to race (50). After a hearing on the

plan, the objections thereto and the response of the School

Board, the plan was approved without material alteration by

order of the District Court entered July 22, 1965 (52-53).

-5-

From that order the plaintiffs appealed on July 23, 1965 (54-

55). Without notice, brief or argument the case was remanded

to the District Court (56-57):

"... for further consideration in the light

of Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, et al., .. Fed,2d ..,

Mo. 22527, decided by this Court on

June 22, 1965, and Price v, Denison Inde

pendent School District Board of Educa

tion, et al., .. Fed. 2d .., No. 21632,

decided by this Court on July 2, 1965."

(2)

The Approved Amended Desegregation Plan

Pursuant to Order of this Court_________

The Government then moved in the District Court to

enter an order "in confomity with the mandate" of this Court

(58-59), and the School Board filed an amended plan for de

segregation in conformity with said mandate "tracking" the

grade desegregation directions of this Court (Singleton v.

Jaqkeop. Municipal Separate School District. 348 F. 2d 729-

5 Cir.1965, and Price v. Denison Independent School District

Board ot Education. 348 F. 2d 1010- 5 Cir.1965) and providing

for desegregation of the:

First, Seventh, Ninth, Eleventh and Twelfth

Grades for the school year commencing

September, 1965.

Second, Third, Eighth and Tenth Grades for the

school year commencing September, 1966.

Fourth, Fifth and Sixth Grades for the school

year commencing September, 1967.

And extending the time to file applications to transfer and

for a more extended and publicized notice of the plan (66-69),

- 6-

which, as thus amended, was approved by Honorable Seybourn H.

Lynne, Chief Judge, on August 27, 1965 (70-71). On October 25,

1965, the Government appealed but the negro plaintiff did not

appeal from this order (72).

On November 23, 1965, on motion of the Government

the time within which to file the record in this Court was ex

tended and subsequently was extended again. Not until April 8

1966, did the individual plaintiff who brought the suit move

to intervene in this Court. The intervention was allowed.

Brief Statement Of Facts

Dr. Kermit A. Johnson, B.S., M.A., Ph. D., Superin

tendent, County Schools (79) testified that 114 county schools

(86) attended by 18,000 negro and 45,000 white students serve

all the territory in Jefferson County except the five munici

palities (Birmingham, Bessemer, Fairfield, Tarrant City, and

Mountain Brook) which have city school systems- The county

schools are organized on a 6-3-3- plan, generally six years

elementary school, three years of junior high and three years

of senior high (80) . Children entering the county system for

the first time go to the school of their choice accompanied

by a parent and enroll (87). They fill out no other applica

tion forms until and unless they desire to change schools (87),

The students are accepted at the school of their choice ex

cept for occasional situations when overcrowding would result

(88). The county has never established any attendance or

-7-

zone lines (88). Dr. Johnson testified that (91):

"They are given the privilege of going

to the school which they prefer, if that

school is not overcrowded - ..."

There are 2,268 teachers in the county system of which ap

proximately 600 are negro (118). The School Board has a negro

director and assistant director of schools (122). The school

population served by the School Board is increasing at the

rate of 1,500 to 2,000 students a year with the greater in

crease in white students (128). In an effort to keep pace

with this growth, 600 new classrooms have been constructed in

the past six years with 12 to 15 additional construction pro

jects now underway (129).

In the opinion of Dr. Johnson it would be difficult for

white or colored teachers to hold their positions and

effectively contribute to education of classes of the oppo

site race under present conditions (139). No colored or

white teacher has ever requested transfer to a school at

tended principally by members of the opposite race (140).

Teachers are employed and retained on the basis of their qua

lifications, their acceptance at the school, and whether they

can successfully teach and discipline their classes (145).

The county schools have never operated on a geographi

cal zone plan (160). The parent of every child entering

school for the first time has the freedom to chose the school

he desires his child to attend (162).

- 8 -

(3)

Co-Ordination of Plan with Those of Other

______School Boards in the County________

An earnest effort was made to coordinate the plan

with those of other school systems in Jefferson County since

each has some transfers from the other (169). About 1,500 stu

dents residing in Birmingham attend county schools and approxi

mately an equal number of county students attend city schools

(214, 239). Accordingly it is desirable that identical plans

be placed in effect to cover the contiguous systems (214).

Government counsel inquired of Dr. Johnson what the

School Board proposed to do if a large number of negroffi ajpplied

for a transfer to an already overcrov;ded white school. Dr.

Johnson noted that (211):

"This might necessitate asking some white

children to withdrav; from that school and

go to a school where there v;as room."

We then inquired and we here repeat v;hether that is the desire

and position of the Government (212).

Ecaialitv of Schools

Of the 26 negro schools presently over capacity 20

will be relieved as the result of a building program already

underway. The Board has under construction additional facili

ties to eliminate overcrowding in 20 of the 26 colored schools

where that condition exists (240). That is not true of the

43 formerly white schools that are and will continue to be

overcrowded (240). Many of the negro schools in Jefferson

County are superior to formerly white schools in the same area.

-9-

For example, the Wenonah (formerly negro) school has a gym

nasium, modern lunch room facilities, spacious library

facilities, whereas Lipscomb (a formerly white school) in the

same neighborhood has no gymnasium, no modern lunch room

facilities and no library. That example could be repeated

over and over (241). It is true as the negro plaintiff argued

(9) that negro schools do not play football at night but this

is due solely to the fact that negro administrative and

supervisory personnel have strongly advised against night

ball games for negro students and confessed that "they can't

control the discipline" (242).

Dr. Myron Liberman was presented as a witness for

the plaintiff. He testified that he was a consultant on

race relations for the New Rochelle,New York system for six

4/

months (253). He admitted that he had never talked with

any representative of the School Board, had never been in Ala

bama until the night preceding his testimony (268). He advo

cated geographical zoning. Obviously this witness lacked any

information or knowledge upon which to base any intelligent

appraisal of the local situation. For example, he compared

the Rosedale School with Shades-Valley without noting that

the recreational area of the Rosedale School recently had been

condemned for a Federal interstate highway, that many of the

additional facilities at Shades Valley were constructed by a

^ If so the results are reported in the integration

conscious Life Magazine of May 6, 1966, page 94

- 10 -

special local tax voted by the white residents in the area

served and that additions were made possible by contributions

from and other groups v/ithout the expenditure of tax

funds. We recognize that this does not exempt any school or

area from constitutional requirements but it does account for

the nature and character of this school plant.

The Fairfield Board of Education Case -

________No. 23,331__________________

Statement of the Case

This suit was filed on March 21, 1965, by negro

plaintiffs against the Fairfield Board and its members seeking

an injunction to prohibit the operation of a racially segre

gated school system and to compel adoption of a plan for the

desegregation of the nine public schools of the system serving

3,938 students, of which 1779 are v;hite and 2,159 are negro.

Without objection the United States was permitted to inter

vene pursuant to Section 902 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C., Section 2000 (h) (2) (24-29).

The Original Plan

Following hearing and pursuant to court order the

Board filed a detailed plan providing for desegregation of

the (48-58):

First, Ninth, Eleventh and Tv;elfth Grades

for the 1965 school year.

Second, Third, Eighth and Tenth Grades for

the 1966 school year.

Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Grades for

the 1967 school year.

- 11-

The Amended Plan

Objections were filed to the plan by the plaintiffs

and the United States. Thereafter the Board filed an amended

plan (59-64) providing for desegregation of the s

First, Seventh, Eighth, Tenth and Twelfth

Grades for the 1965 school year.

Second, Third, Ninth and Eleventh Grades

for the 1966 school year.

Fourth, Fifth and Sixth grades for the 1967

school year.

On September 7, 1965, the District Court entered an

order, approving the plan, as amended (65-72). On October 22,

1965, the United States (but not the original negro plaintiffs)

appealed fromthe order of the District Court approving the

Board's amended plan (73-74). By appropriate order, at the

request of the Government, the time was extended to file the

transcript of record.

The plan provides 'that application forms are made

available at the offices of the principal of each school

and are to be filed in accordance with existing regulations

at the office of the superintendent in Fairfield with assurances

that they will be promptly handled. Students who do not apply

for transfer will remain assigned to the schools to which

they are now attending. Students entering the system for

the first time can apply for assignment to the school of their

choice without regard to whether the student's grade has been

desegregated. Wide publicity was given and notice of the- 12-

detailed provisions was published three times in a daily

newspaper circulated throughout the area.

Brief Statement of Facts

Prior to filing the subject suit the Fairfield Board

had never received an application from a colored student for

transfer to a formerly white school (77, 113) and no teacher

or supervisory personnel had requested transfer to a school

formerly attended by members of the opposite race. Provisions

had been made and publicized of the availability of such

transfer applications which would originate with the pupil or

teacher (119). The District Court ordered the School Board to

file a plan for desegregation of its schools, and the plan,

above noted, was filed in response to this order. Before

the plan was ever prepared or filed, the Justice Department

stated it desired to object thereto (81).

The brief filed by the negro plaintiff (19) failed

to note that the Fairfield system is in the process of

organizing into a 6-3-3 system (86) with a new building

and three year junior high school to be available for

students at the beginning of the 1966 school term (88).

The schools historically serving the Fairfield area with the

grades in each at the time of hearing and the pupil-teacher

ratio as set out in Plaintiff's Exhibit 1, v;ere as follov7S

(178):

-13-

Formerly Negro

Grades 1 - 6 Elementary

Englewood 1 - 2 3

Robinson 1 - 3 3

Formerly VJhxte

Donald 1 - 2 6

Forest Hill 1 - 2 6

Glen Oaks 1 - 2 9

Grades 7 - 8 - Jr. High

Interurban Heights 1 - 3 4 Fairfield Jr. High 1-28

Grades 10 - 12 - Sr. High

Fairfield Industrial 1 — 20 Fairfield 1 — 18

It is noted that the lowest pupil—teacher ratio in

the elementary schools was formerly colored, and that there

is no wide disparity in any of the schools.

The negro plaintiffs are in error in suggesting

that the plant facilities proyided for negro students are in

ferior to those proyided for white students (their brief p.20).

The white schools do have playground equipment, shrubbery

and some black-topped areas all of which were provided by

interested PTI\ organizations without any cost to the school

board (98). During the past two years PTA organizations

have raised and contributed to the Fairfield Board for improve

ment of specific schools the sum of $42,500 (111) of which

$40,000 was contributed by PTAs at formerly white schools

and $2500 by colored PTAs at formerly colored schools (112) .

The construction program of the Fairfield Board covering the

period from the 1953-1954 school year through the 1964-1965

school year shows a total expenditure for formerly white

-14-

schools of $784,000 and a total for formerly colored schools

of $941,000 (103) or $157,000 more for formerly colored than

for formerly white schools. Many facilities of the formerly

negro schools are superior to those of the formerly white

schools. For example, the library at the Fairfield Industrial

High School is far more adequate and modern in design and

in capacity than the library at the formerly white Fairfield

High School (105). The same situation is true with respect

to the auditorium, buildings and other facilities. Additional

examples were not developed in accord with and conformity to

the statement (and ruling) of the District Court that such

evidence in this proceeding was immaterial. Admittedly,

the Englewood (formerly colored) school has been a problem to

the Board. Students have poured concrete in the urinals,

filled the vent pipes with slag, removed doors from the rooms,

destroyed windows in the building (109) making it difficult

for the Board to keep it in the condition desired (110).

Notice of the Fairfield plan was published three

times in a daily newspaper of general circulation throughout

the area, and in addition was carried on all news, radio, and

television media. The application forms are simple and pro

vide for desegregation of choice. The requirement that first

grade students report to the school to v/hich they would have

reported prior to any plan of desegregation was incorporated

with the feeling that such applications, originally filed with

their own race, would receive prompt, considerate attention.

-15-

STATEMENT OF THE CASE IN BEHALF OF APPELLEES

(Bessemer School Board, et al. No. 23335)

The Bessemer School Board plan of desegregation is shown

at pages 43 (the original plan submitted to the District Judge)

64 (the order of the Court approving it with modifications), 81

(the amendment to the plan submitted by the Board following the

order of vacation and remandment of the Fifth Circuit dated

August 17, 1965, R.71), and 85 (the order of the District Court

dated August 27, 1965, finally approving the plan as amended,

the order from which this appeal is taken).

The Board's amendment to the plan (R.81) approved by the

Court's final judgment put into effect a plan providing that

for the school year commencing in September, 1965, the fitst,

fourth, seventh, tenth and twelfth grades were desegregated for

the school year commencing September, 1965. The second, fifth,

eighth and eleventh grades were desegregated for the school

year commencing September, 1966 and the third, sixth and ninth

grades were desegregated for the school year commencing in

September, 1967. The final amendment and order of the Court,

effectuated a three-year desegregation plan, conforming as far

as grades were concerned to the Singleton (first) and Price

decisions, 348 F.2d 729, 348 F.2d 1010, respectively, decided

on June 22, and July 2, 1965, respectively. The form of the

notice to be given, specified as a part of the Court's first

order (R.66) that all applications filed in the office of the

Superintendent of Education located at 412 North 17th Street,

-16-

(spelled out in the notice) for assignment or transfer "to a

school theretofore attended only, or predominently, by pupils

of a race other than the race of pupils in whose behalf the

applications were filed, would be processed and determined by

the Board, without discrimination as to race or color.

As to the first grade, it was specified in the plan, the

Court's order, and the notice that Negro children entering the

first grade would report on the first day of September, 1965,

to each of the four elementary schools named in the plan.

Carver, Dunbar, Hard and 22nd Street Schools; that upon "regis

tration" meaning, we say, reporting, an application might be

made by the parents for the child's assignment to any school

whether formerly attended only or predominently by white chil

dren or by Negro school, and an attack is made upon the plan

in that regard. However, not knowing the identity of the first

grade children (who of course had never been enrolled by the

schools) it was determined best by the Board and approved by

the Court that they report to the particular school to which

they would have reported prior to any plan of desegregation.

It was known that they had to report somewhere and it is to be

assumed that it would be best for them to report to a school

rather than to the office of the Board. The plan does not

state that they would be first enrolled in the school to which

they reported but merely that they would be registered and

that their parents immediately could ask for assignment either

to that particular school or to another, whether formerly

-17-

white or colored. This feature of the plan will be more par

ticularly discussed in the argument under Section A.

It is stated on p.3 of appellant's brief, footnote, that

the District Court in approving the plan "excepted" the pro

vision governing the initial assignment to the first grade.

No such language was used. The actual language is shown at

R.86, wherein the Court stated that the defendants were re

quired to restudy such plan and report their conclusions on

or before December 31, 1965, meaning necessarily for ensuing

school years. The appellant states, same page, that the Board

has not reported to the Court.

The true fact is that the defendants (appellees), after

the taking of the present appeal, filed a statement with the

Court stating in effect that since the United States had elec

ted to appeal from the Court's order of August 27, 1965, it

was assumed that no report was due to be filed or submitted

pending disposition of the appeal unless further directed by

order of the Court. (See index to Record, p.lO) We do not

find this statement printed, but evidently it was transmitted

as a part of the record. No further directions were given by

the District Court and these appellees therefore assumed that

the District Court thought that since the entire matter had

been thrown into the Court of Appeals, it would be futile, to

say the least, for the District Court to attempt to proceed

further; and it was doubtful whether the appeal deprived the

Court of jurisdiction so to proceed. Had the matter been left

-18-

to the District Court, a full report would have been made and

undoubtedly the entire administrative problem relating to the

assignment of pupils in the first grade would have been ironed

out anew.

On p.13 of appellant's brief, in footnote, it is stated

that the plan contains no notice provisions for the school

years following 1965-1956. This statement is entirely inac

curate. The amended plan which, along with the original plan,

(as modified by the District Courts first order of July 30,

1965, R.64) makes provision with reference to notice for all

years under the plan subsequent to the year commencing in Sep

tember, 1965, as to all desegregated grades, the form of the

notice to conform to that specified in the District Court's

original order, varying necessarily only as to dates. While

some mention is made, we believe, in one of the briefs that

publication only one time was required, it will be noted from

the original order, R.64, adopted by the amended plan, that

there were to be at least three publications "in a news paper

of general circulation in the City of Bessemer." This proce

dure was followed.

The plan as amended further provides that students enter

ing the Bessemer school system for the first time "shall ob

tain application from the school of their choice which shall

be completed, delivered to and promptly processed by the

Superintendent without regard to race or color." (R.83).

We think that at some place in briefs there is a com-

-19-

plaint that there was no provision for students entering the

system for the first time (other than the first graders). In

any case, the provision to which we refer is set out in the

amended plan, R.83.

The plan in its various aspects, and in the effect there

of, will be referred to and discussed in our argument in the

appropriate portions thereof, but we here point out that the

rights of choice to be exercised under the plan were accorded

both initially and on an annual basis.

In the brief of the United States, it is stated that both

the plaintiffs and the government noted an appeal from the

order of August 27, 1965. We submit that this is an inaccurate

statement. The only notice of appeal ever filed by the plain

tiffs was from the order of July 30, 1955 (R.69). While later

an appeal bond was filed by plaintiffs (R.87), this neces

sarily was merely to perfect the appeal already taken. No no

tice of appeal by plaintiffs was ever filed or served, as far

as the order of August 27 is concerned. In fact, the plain

tiffs, who seek to "intervene" in the appeal, purport to state

in their intervention petition, which was allowed, that it was

through inadvertence that no appeal was taken. While this

fact may be of no particular significance, it is nevertheless

a fact upon which the record should be set straight.

Hence, when we refer to "appellant" or to appellant's

brief, we are referring to the brief of the United States

only. - 20 -

ARGUMENT

A..

The first argument made in the brief for the United

States is that the plan for desegregation retains racial as

signment for students in grades purportedly desegregated. The

principal basis of this argument apparently is (1) the objec

tion that the plan approved by the District Court simply pro

vides that students in desegregated grades may apply for trans-

f ^ to a school previously attended by students of another race

and that (2) the children entering the first grade are to re

port to formerly all Negro schools nearest their homes and

white children report to formerly all white schools and that

upon registration thereat an application may be made by the

parents for assignment to any school.

The appellant concludes that the plan therefore retains

"the dual school system", and cites not only the Brown case,

but also Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County, 342

F.2d 225, 228 (C.A. 5, 1964) and Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14,

22 (C.A. 8, 1965).

We first cliscuss the situation pertaining to the election

of pupils already in the schools (not those entering the first

grade or those otherwise coming into tha system for the first

time) to transfer to another school. Appellant's complaint

evidently is, although it does not specifically say so, that

requiring pupils already in segregated grades and in segregated

schools at the time a plan for desegregation is put into effect

21

to apply for a transfer to a desegregated school and grade,

even though under circumstances that do not make the right of

transfer onerous and without regard to race or color, consti

tutes the maintenance of a "dual system" and is, therefore, a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in itself.

Implicit in that contention, we suppose (taking into con

sideration what the appellant's brief says in other places and

also the contention for the putting into effect of the 1966

HEW'Guidelineis that each year each child must make an af

firmative choice, whether white or colored, as distinguished

from a permissible choice. We have found no decision of this

Court up to now which, in our opinion, supports this view (and

we think the same may be said of the 1965 HEW "Guidelines").

Let us take the last decision, the second Singleton case, Sin

gleton V. Jackson Separate Municipal School District, 355 F.2d

865. While admittedly the decision there was that the "stan

dards promulgated by" HEW should be imposed in the plan in

order to make it sufficient (the question as to what, if any,

weight should be given to such standards, especially the 1966

standards, promulgated since Price and Singleton [two Single-

ton cases]), the opinion on the question with which we are now

dealing, and which is the subject of other portions of this

brief relating to the contention of the appellant which we are

now discussing, refutes that contention. We illustrate this

and other points involved.

In the first instance, if the government is now contending

22

that there should be an iminediate desegregation of all grades,

whether on a freedom of choice basis or not, such a contention

was rejected in the Singleton opinion (See III(1)(2), p.870).

Another objection by the United States to the Jackson,

Mississippi plan was that it failed to provide for the desegre

gation of all services, programs and activities. With refer

ence thereto, the Court said (p.870, Hda.3) ;

"The United States objects that the plan fails

to provide for the desegregation of all services,

programs, and activities. The Board adequately

answers this objection by stating that all public

services, buses, and other transportation facili

ties, and all programs and activities ‘shall be

available to all pupils duly enrolled [in a school]

without regard to race, color, and national origin'."

Thus, even though the plan involved did not specifically

refer to the factor of services, programs and activities, this

Court evidently treated such an omission as cured by the

board's "assurance". This is a matter which will be treated

in another portion of this brief.

Another objection made by the United States in Sinaleton;

That the plan does ro t provide for the elimination of race in

the employment and retention of teachers, staff personnel, etc.

Admittedly, our plan does not cover this factor, and this will

be discussed in another portion of this brief.

With reference to other objections made by the United

States in the Sinqleton case, the opinion states, p.870, Hdn.5;

"The United States objects to the failure of the

Board to require all students to make an affirmative

choice of school. The Board's answer is that there

is no compulsory school attendance law in Mississip-

23

pi; however, children in the desegregated grades

have a free choice of schools." [Emphasis by

the Court]

"At this stage in the history of desegregation

in the deep South a 'freedom of choice plan is an

acceptable method for a school board to use in ful

filling its duty to integrate the school system.

In the long run, it is hardly possible that schools

will be administered on any such haphazard basis.

Although this Court has approved freedom of choice

plans, we have conditioned our approval on proper

notice to the children and their parents and also

on the abolition of the dual geographic zones as

the basis for assignment. As we said in Lockett;

'We approve the use of a freedom of choice

plan provided it is within the limits of

the teaching of the Stell and Gaines cases.

We emphasize that those cases require that

adequate notice of the plan to be given to

the extent that Negro students are afforded

a reasonable and conscious opportunity to

apply for admission to any school which they

are otherwise eligible to attend without re

gard to race. Also not to be overlooked is

the rule of Stell that a necessary part of

any plan is a provision that the dual or bi-

racial school attendance system, i.e., sepa

rate attendance areas, districts or zones

for the races, shall be abolished contempo

raneously with the application of the plan

to the respective grades when and as reached

by it. Cf. Augustus v. [Board of Public In

struction of] Escambia County [Florida], 5

Cir.306, P.2d 862, supra. And onerous re

quirements in making the choice such as are

alluded to in Calhoun v. Latimer, 5 Cir., 1963,

321 F.2d 302, and in Stell may not be re

quired.'" [Emphasis ours]

The Court's rejection of the objections dealt with in the

above excerpt from the opinion appears to us to be clear.

We assert that the statement made in appellant's brief.

5.

At this point we have not had the opportunity to examine spe

cifically the terms involved in any plans or plans involved.

24

p.9, that the plan retains the dual school system, and violates

the Fourteenth Amendment by reason thereof, is not supported

by the decisions of this Court, including Lockett, cited in

support thereof.^*

Under the Fifth Circuit decisions, what is meant by the

term "dual system"? The meaning is shown in the quotation

from Lockett as embracing separate areas, districts or zones

for the races, a discussion of which will be amplified below.

Stell, the identical language is used in defining a dual

school attendance system (Hdn.l7, p.64).

In Armstrong, similar language is used, to-wit (p.51,333

F.2d) :

"The dual or bi-racial school attendance system,

that is, any separate attendance areas, districts

or zones, shall be abolished as to each grade to

which the plan is applied and at the time of the

application thereof to such grades, and thereafter

to additional grades as the plan progresses. Bush

V. Orleans Parish School Board, (5th Cir. 1962)

308 F.2d 491."

6.

Other decisions of the Fifth Circuit are Stell v. Savannah

Chatham County Bd. of Ed.,333 F.2d 55, Armstrong v. Board of

Education of City of Birmingham, 333 F.2d 47, as well as

Lockett V. Board of Ed. of Muscogee County Sch. Dist., Ga.,

342 F.2d 225.

25

In the Bessemer plan for desegregation, there is no es

tablishment or requirement of any dual zone or separate zone,

pertaining to the right of Negro pupils to attend formerly all

white schools. This is also true of the Jefferson County and

Fairfield plans. There is no prohibition against the colored

student's attending a proper grade in a formerly all white

school merely because the formerly all Negro school which he

attends is closer to his place of residence or is within a dif

ferent locality from that of the "white" school which he de

sires to attend. He is given in effect a freedom of choice,

upon request, to attend any such school in the isystems.

While all students in desegregated grades are not required to

make an affirmative or mandatory choice, in order to remain in

the school to which they are previously assigned, nevertheless,

under the plan they are given a choice after notice, of their

rights to leave the school and enter another of their choice.

While the pupils are not directed to sign a form choosing one

way or another,

"Negro pupils are afforded a reasonable and con

scious opportunity to apply for admission to anv

school for which they are otherwise eligible

without regard to their race or color, and to

have that choice fairly considered by the enrol

ling authorities. This is the first step. The

School boards must give timely notice of this

fact, and in such manner and terms as to bring

home to Negro students notice of the rights that

are to be accorded them. Cf. the notice given

in Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of

Escambia County, 5 Cir., 1962, 306 F.2d 862."

The above words are quoted from Stell, at p.65, 333 F.2d.

26

While Stell requires that any plan of assignment "and

transfer" must be applied without regard to race in an even-

handed manner (p.65) and that "Onerous requirements such as

the notarization of applications for assignment or transfer

are not to be condoned", and holds, for example, that "testing

criteria", as in Calhoun v. Latimer (especially where applied

only to Negro students seeking transfer and assignment) are

not permissible, nevertheless, where onerous requirements do

not exist, a plan will not be struck down where the right of

transfer is available and is extended. We think that such a

principle runs through all of the decisions of this Court, and

we construe none of them as being to the contrary.

Also, while the right of choice is permissible and not

mandatory, the pupil staying where he is unless he requests a

transfer, this right of transfer is at least an annual one,

and all, we say, that was required even by the 1965 Guidelines.

The compulsory or mandatory annual freedom of choice was first

prescribed in the 1966 Guidelines and doubtless more stringent

and complicated requirements will be implemented not later

than the year 1967, and at least annually thereafter.

We revert to the last quotation made from Singleton, se

cond case, in this brief, to the effect that in a court plan

of desegregation the failure of the plan to specify a contin

gency of overcrowding, or otherwise, is by no means fatal, the

idea being that much is to be left to the supervision of the

District Judge whose ever watchful eye is over the case. The

27

situation might be different where the plan is a voluntary one

submitted to the official of an executive department in Wash

ington, far removed from the situs of the school system.

The plans in the Jefferson County, Bessemer and Fairfield

Board cases are essentially the same, and were patterned es

sentially after the plan submitted following final hearing in

the District Court in Armstrong v. the Board, the Birmingham

case.

In the Armstrong opinion, second case, allusion was made

to the first Armstrong decision involving an application to

the Fifth Circuit for an injunction pending appeal, 323 F.2d

333. In that first decision directing the desegregation of

at least one grade, reference was made to the plan submitted

pursuant thereto which in essence was the same as the plan

finally submitted following final judgment (after the second

decision of the Fifth Circuit), as far as the provisions for

an application for transfer, in the desegregated grade, from

a previously all Negro school (in which the applicant was ne

cessarily enrolled) to the formerly all white school are con

cerned. The language of Armstrong, second, referring to this

first plan, aided by necessary implication, shows that it was

in effect approved, although it contained the exact provision

that except as provided in the plan, students should remain

assigned to the school to which they had been assigned accord

ing to tradition and custom, prior to any decision in the case.

Such a provision, of which the government strenuously com-

28

plains, is similar to that contained in the three Cases now

on appeal to this Court.

In Armstrong, it is further said, with reference to the

discretion to be imposed in the trial court, and of the confi

dence that was placed in him:

"Applicants will not be required to submit to

undue delay in the consideration of their ap

plications, or to burdensome or discriminatory

administrative procedures."* * * * * * * *

"The United States District Court has wisely

retained jurisdiction of this case for the pur

pose of permitting the filing of supplemental

complaints in case of any unconstitutional ap

plication of the Alabama Pupil Placement Law^^̂J

against the plaintiffs, or others similarly si

tuated, or with respect to any other unconsti

tutional action on the part of defendants (Su

perintendent, Board of Education, etc.) against

them. Such complaints may be submitted as a

class action as authorized by F.R.Civ.P.23,

thus avoiding the necessity of time consum

ing delays on the part of those who complain,

and also avoiding repeated and extended hear

ings in the District Court.

All of this shows that mere details which might otherwise

be considered necessary in an HEW voluntary plan, should be

left to the judgment of the trial court, available for quick

We have underscored these words because of the attack made

in appellant's brief, p.lO, upon the plan merely upon the

ground that the regulations of the Board (evidently implement

ed by testimony of the Superintendent) prescribed that the

"Alabama Pupil Placement Law" would be employed in considering

applications for transfer.

8 .

The Court noted that the provision in the District Court's

decree that the District Court would exercise its discretion

in directing the further implementation of the plan and in

hearing any complaint which might be presented.

29

hearings, as also pointed out' in Singleton.

The Court in Armstrong saw no objection whatsoever to a

consideration of the Alabama Pupil Placement Law, Title 52,

§61(4), Code of Alabama (Recomp.1958), in considering applica

tions. Incidentally, this law, first passed in 1956 and re

passed in 1957, along with Alabama constitutional provisions,

effected a repeal of all Alabama statutes requiring segrega

tion of the races in schools and authorized the school boards

in effect to entertain and grant applications of individuals

on a non-racial basis. It was upheld on its face in Shuttles-

worth V. Birmingham Board, 162 F.Supp. 372, 374, affirmed, 358

U.S. 101, as pointed out in Armstrong.

It is not to be presumed, therefore, that because refer

ence is made to the Alabama Pupil Placement Law in the testi

mony of the Superintendent, or in regulations of the Board

pertaining to transfers, the right to transfer will be made

onerous or will be made to depend upon criteria which are not

permissible. The distinguished Trial Judge in Armstrong has

warned all boards that the law is not to be applied in an un

constitutional manner and that he will immediately hear com

plaints to that effect.

Since it appears to be the fashion these days to make re

ference to everything that might be considered relevant to the

case, whether it is in the record on appeal or not (appellantis

brief, p.l4, ftn.7, Bessemer case, the enrollment of the Bes-

30

semer schools for the school years 1955-66 is given as 5284

Negro students - 2920 v/hite students, with 13 Negro students

attending schools with white children), we take the liberty of

stating that, although few Negro students applied to attend

formerly all white schools, none was turned down. This con

stitutes an assurance from the Board that care will be taken

that there be no unconstitutional application of the placement

law or any other in processing applications for assignment or

transfer. Fifteen applications for transfer were filed with

the County Board. Fourteen were approved, and one was denied

on admittedly valid grounds having no relation to race.

Further reference to cases pertaining to freedom of

choice plans for desegregation, some of which are referred to

in this portion, will be made in that part of the brief which

specifically discusses the question of what weight, if any,

should be given to the effect of the standards of the HEW, as

implemented by the 1966 Guidelines.

We have already referred to the possible or probable mo

tives governing the Board in the administration features per

taining to processing of first grade students. As stated,

administratively they must report somewhere and the meet sim

ple procedure would be to allow them to report to the school

which by tradition and custom the members of their race have

reported before. Assurance is given that their parents will

be fully informed of their right to attend a formerly all

31

white school by the principal and teachers in charge of the

registration. They v;ill then be allowed to make a free choice.

In the first Armstrong plan (referred to and considered by the

Court in the second Armstrong decision), there ware provisions

that except as provided in the plan, pupils would be assigned

to the schools to which they had been traditionally assigned

before desegregation. It was never thought that there was any

thing wrong with this provision. As far as the first grade is

concerned, the plan is not intended to go that far. It is in

tended that there merely be a place to report for registrat ion

with an immediate choice to attend another school.

It is difficult, we submit, to instruct parents to take

first graders to any school in the system which they prefer.

The administrative difficulties are apparent. It is the in

tention of the Board that, while a general policy of freedom

of choice has always been in effect, it is preferable that the

children be persuaded to go to school in a particular locality

if possible. This does not mean that any attempt will be made

in the future to persuade any Negro child to go to a school

attended by the members of his race merely because he lives

closer to that school.

We note in Vol.IV, Appendix to briefs of the United

States under B, annotations to proposed decree, and under sub

section (d) entitled "Mandatory Exercise of Choice" only four

cases, three of which are decisions of the U.S. District Court

32

Middle District of Alabama, and one of which is a consent de

cree of the District Court of the Eastern District of Virginia.

We have examined a copy of the three orders which were

not consent decrees and find that in each of them, on the ques

tion of so-called mandatory exercise of choice, the provisions

of the 1966 Guidelines were obviously adopted. We say this be

cause essentially the same language in that regard is used.

While the order in one of these cases, U.S. V. Lowndes County

Board, dated February 10, 1966 (the 1966 Guidelines are stated

to have come into effect in March, 1966) may have been ren

dered prior to the official date of effectiveness of the 1966

Guidelines, these Guidelines were certainly in the mill at

that time and evidently urged upon the Court by the Department

of Justice; in view of the language of the Guidelines. All of

this leads us to wonder whether, when the Department of Justice

urges upon this Court the "expertise" of HEW in the matter of

formulating a uniform plan for the desegregation of all schools

in the South, it is really talking about the so-called "exper

tise" of the Department of Justice itself. It is understand

able that those who are employed in the education branch of

the Department of HEW, supposedly having some knowledge in the

field of education in order to be there, should be called ex

perts along that line, but it is less understandable how, in

the short span of time between the passage of Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, they could have become experts in

33

the matter of integrating schools.

The standards and Guidelines of HEW will be more fully ex

plored near the end of this brief, but we wish to make our po

sition plain now that, since they involve a statute (Title VI)

having to do with the expenditure of tax money and not the de

segregation of schools under the Fourteenth Amendment, these

standards and Guidelines should not be given any more effect

than that of expert testimony which might be introduced in a

desegregation case. Viewed in that light, they should be ad

mitted only upon the supporting testimony of the so-called ex

perts, to cross examine whom the defendants should be entitled.

While Title VI, the 1964 Civil Rights Act, covers every

conceivable activity (including numerous ones having no rela

tion to the Fourteenth Amendment), it conferred no power per

taining to the desegregation of schools which did not exist

prior to the passage of the Act itself. As to school desegre

gation, it is limited by Title IV, the only Title which estab

lishes a "national policy" as far as school desegregation is

concerned. This can be demonstrated by the language of Title

IV (schools are not mentioned in Title VI as such) and also by

the debates and statements shown in the Congressional Record.

The pertinent provision of Title IV is as follows;

"...provided that nothing herein shall empove r any

official or court of the United States to issue any

order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any

school by requiring the transportation of pupils or

students from one school to another or one school

34

district to another in order to achieve such racial

balance, or otherv/ise enlarge the existing pov;er of

the court to insure compliance with constitutional

standards."

The language itself effectively demonstrates that on this

subject the powers of a court are not enhanced over and above

the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment itself and the

statements by the floor leader in the Congressional Record de

monstrate that this limitation is effective (upon executive

departments) as far as Title VI is concerned when applied to

9desegregation of schools. *

Senator Pastore, Floor Leader for Title VI said:

"Let me advise Senators that the failure of a district

court to desegregate the schools will not jeopardize the

school lunch program; it absolutely will not. Even if a

community does not desegregate/ that will not jeopardize

the school lunch program - unless in that particular

school the white children are fed, but the black children

are not fed; and I refer Senators to page 33 of the bill,

which states very, very clearly: 'which shall be consist

ent* - in other words, the orders and rules - 'shall be

consistent with the achievement of the objectives of the

statute authorizing financial assistance.'

"We have a school lunch program, and its purpose is to

feed, not to desegregate the schools; therefore, that

would not be consistent. But if a school district did not

desegregate, it could no longer get federal grants,let us

say, to build a dormitory - not unless it integrated; and

a hospital could not receive 50 percent of the money with

which to build a future addition unless it allowed all

American citizens who are taxpayers and who produce the

tax funds that would be used to build the addition, to

have access to the hospital.

"So we must remember that the shutting-off of a grant

must be consistent with the objectives to be achieved. A

school lunch program is for the purpose cf feeding the

school children. If the white children are fed, but the

bjack children are not fed, that is a violation of this

law." (110 Cong.Rec., p.13936, June 19, 1964) * * * * * * * *

35

The footnote demonstrates that the Department of Health,

actingEducation and Welfare and every other executive department/un-

der Title VI are limited by Title IV and given no power to en

large upon the bare prohibition of the Core titution itself

(Fourteenth Amendment) regardless of the power they may have

assumed, as far as school desegregation is concerned.

Furthermore, by the terms of the Civil Rights Act itself,

application of discrimination is limited to the single ac

tivity, or program, in which it is charged that discrimination

P^^cticed. For example, under the Acts providing for grant

in aid to education existing at the time of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, the grants in aid were not general ones to the

schools but only to those providing aid for a particular pro

gram. One has already been mentioned in the footnote, the

school lunch program (administered by the Department of Agri

culture) . Another is in the Acts granting federal aid for vo

cational training under 20 U.S.C. 11-15, 16-28, 20 U.S.C. 15i-

9. (Con't)

"Both Senators Pastore and Humphrey (D.Minn.) declared that

school desegregation would not effect the school lunch program

and that the matter of desegregation of schools properly would

come under the provisions of Title IV of the Act, which is di

rected specifically at integration of schools." (This state

ment is taken from Operations Manual, Civil Rights Act of 1964 p.94]

* * * * * * * * *

"A further proviso is added to this section which provides

that nothing herein shall empower an official or court of the

United States to require the transportation from one school

district to another in order to achieve racial balance, or

otherwise enlarge the existing power of the court to insure

compliance with constitutional standards." (Cong. Rec. 12381-5

June 5, 1964 - Senator Dirksen)

36

15-q, 15aa-15jj, 15aaa-15ggg, and 20 U.S.C. 30-34, training

which, as shown by the record in the Bessemer case, for exam

ple, is confined exclusively to the high schools and even to

particular grades in high schools. We say that the Congress

did not intend to confer upon an executive department the pow

er to require a plan for the desegregation of an entire school

system, merely to abolish discrimination in a particular pro

gram, and the Congress did not intend, therefore, that the

"expertise" of the HEW be employed for that purpose.

9. (Con't)

See, also, "Humphrey Explanation (Title VI)", Cong.Rec.

12288-9. * * * *

"Mr. BYRD of West Virginia. Can the Senator from Minnesota

assure the Senator from West Virginia that under title VI

school children may not be bused from one end of the community

to another end of the community at the taxpayers' expense to

relieve so-called racial iiribalance in the schools?

Mr. HUMPHREY. I do.

Mr. BYRD of West Virginia. Will the Senator from Minnesota

cite the language in title VI which would give the Senator

from West Virginia such assurance?

Mr. HUMPHREY. That language is to be found in another title

of the bill, in addition to the assurances to be gained from a

careful reading of title VI itself.

Mr. BYRD of West Virginia. In title IV?

Mr. HUMPHREY. In title IV of the bill."

* * * *

"Mr. JAVITS. * * * * * Taking the case of the schools to

which the Senator is referring, and the danger of envisaging

the rule or regulation relating to racial imbalance, it is ne

gated expressly in the bill, which would compel racial balance;

Therefore, there is no case in which the thrust of the statute

under which the money would be given would be directed toward

restoring or bringing about a racial balance in the schools.

If such a rule were adopted or promulgated by a bureaucrat,and

approved by the President, the Senator's State would have an

open and shut case under section 603. That is why we have pro

vided for judicial review. The Senator knows as a lawyer that

we never can stop anyone from suing, nor stop any Government of

ficial from making a fool of himself,or from trying to do some

thing that he has no right to do,except by remedies provided by

law. So I believe it is that set of words which is operative."

37

B

The Plans contain sufficient details

and prescribe reasonable notice____

The negro plaintiffs and the Government are in error

in stating that the plans "fail to specify how or when the

,applications for transfer can be obtained." To the contrary

the plans specifically provide that the forms may be obtained

from the offices of the Superintendent of Education, whose

address is given and further that parents of first grade

students may file notice of their choice and obtain forms at

the schools in their neighborhood. The forms simply provide

for indication of choice and were framed to avoid any "onerous

requirements" as directed by this Court in Stell v. Savannah-

Chatham County Board of Education, 333 F. 2d 55. In a separate

section (hpp. iO/ we discuss in detail the abdication decree

suggested by the Government, Section II (d) of which details

with public notice of the pj^oposed plan, we find no objection

to this paragraph, except as to the requirement that notices

be sent to every home. Subsection (f) suggests that the

notice required be sent by "First class mail - together with

a return envelope addressed to the superintendent." Appar

ently they recognize that the proper and suitable place to

file the application is the office of the superintendent. To

require a letter to be sent to every home, as hereinafter

noted would constitute unreasonable and excessive cost to

many local boards already faced with the difficult task of

-38-

living within a limited budget in an era of continued

inflation.

The present plans require that notice be published

on three separate occasions in a daily newspaper and already

are given to and carried by all news, radio and television

media. This Court has set out with exactitude its notice

requirements in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District (5th Cir. 1-26-66) 355 F. 2d 865, 871, as follows:

"The plan does not provide for individual

notices to students and their parents. The

Board does provide for publication of the

Plan August 16, 23, and 30 in a newspaper

having a general circulation throughout

the district'so as to give all pupils and

their parents or guardians notice of the

rights that are accorded them, and such

publications will also inform them where

copies of the form for exercising their

rights may be readily obtained.' In clari

fying the plan, the Board added that it

would use newspaper, radio, and television

facilities to inform pupils and their parents

of their rights; that the entire plan would

be published; and that office telephone numbers

of the general administrative staff would be

listed for calls for information. We regard

such notice as adequate."

The subject plans are in accord with this requirement.

The Singleton case does not require and in fact

pointed out that "the plan does not provide for individual

notices to students and their parents." To require the local

school boards initially or annually to undertake the burden

of preparing and mailing out the hundreds of thousands of

letters proposed by the Government is unreasonable and would

constitute a tremendous waste of public time and money.

-39-

c.

RESPONSE TO PART C OF APPELLANT'S BRIEF

1. Necessity Or Propriety In Bessemer

Desegregation Plan Of Provision To Elim

inate Inferiority Of Traditionally Negro

Schools.

This part of the brief pertains only to No. 23335, the

suit against the Bessemer Board of Education, and is in reply

to the contentions of the government on pages 15 through 17 of

its brief that the formerly colored schools in the Bessemer

system are inferior to the formerly all-white schools and that

the Bessemer desegregation plan is defective in that it does

not contain provisions designed to correct the inferiority of

schools traditionally attended by negroes. We expect to de

monstrate that as to the Bessemer Board of Education the fact

ual assertions in Section C of the government's brief are in

accurate and misleading, and that the relief requested by the

government in this regard, both in the brief and in Part VI

of its proposed decree, is not only unnecessary and indeed in

large part impossible, but also beyond and inconsistent with

anything thus far required by any appellate-court decision of

which we are aware. As hesitant as we are to burden this brief

and the Court with factual details concerning the relative

attributes of the schools, the misleading tendencies of the

government's factual assertions and statistical tables and the