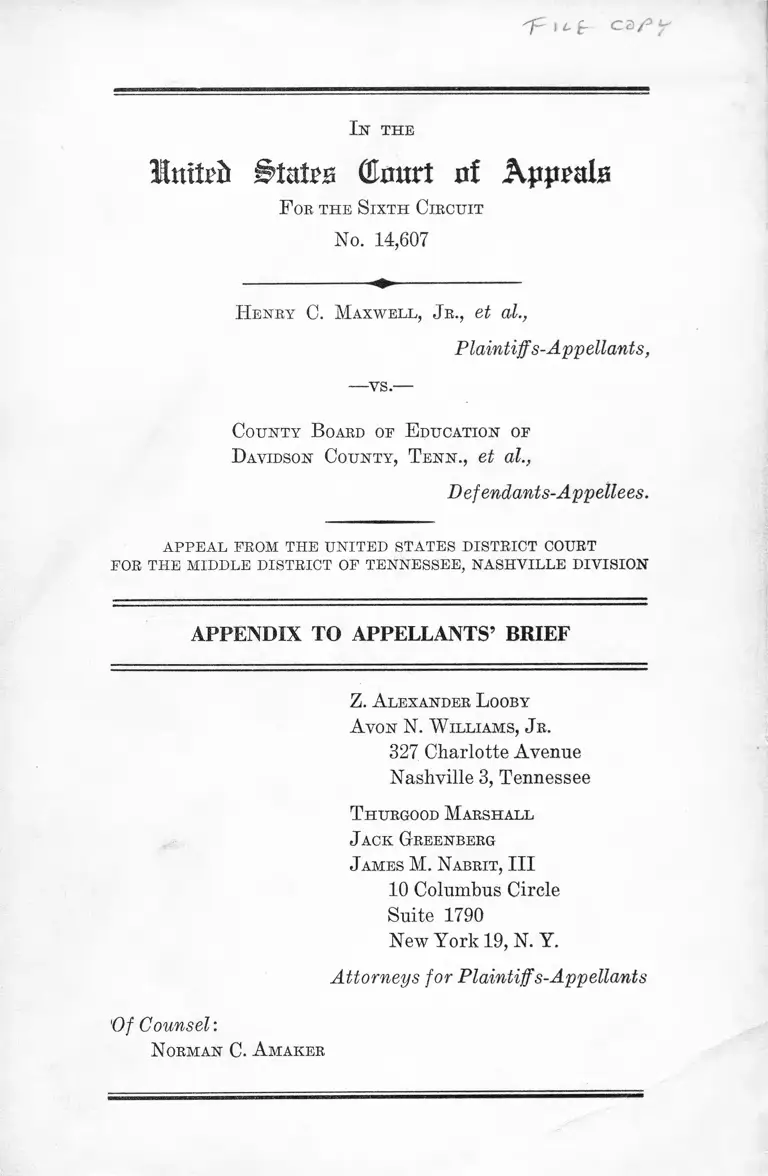

Maxwell v. Dawson County, TN Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maxwell v. Dawson County, TN Board of Education Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1961. 0a9cac38-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0f85aed3-7a79-4662-9855-6de2874f21a2/maxwell-v-dawson-county-tn-board-of-education-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

-f- i l t c a / ’ v

In t h e

Htttfrii Btn&B GImtrt nf Appeals

F ob the Sixth Circuit

No. 14,607

H enry C. M axwell, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

—-vs.—

County B oard oe E ducation or

D avidson County, T e n n ., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE, NASHVILLE DIVISION

____________________________ _______________ ___

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Z. A lexander L ooby

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood M arshall

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 1790

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

'Of Counsel:

N orman C. A maker

I N D E X

PAGE

Complaint .............................. 7a

Motion for Temporary Restraining O rder................. 26a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction ............................. 27a

Order to Show Cause .................................................... 28a

Motion to Dismiss ................................. 29a

Affidavit of J. E. Moss .................................................. 31a

Exhibit “ A ” to Affidavit ...................................... 36a

Exhibit “ B ” to Affidavit ........................................ 37a

Affidavit of Frank White ............................................ 38a

Affidavit of Melvin B. Turner...................................... 40a

Motion to Strike Certain Portions of the Complaint.. 42a

Answer .............................. ...... -....................................... 43a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing, September 26,

1960 ............................................................................... 52a

J. E. Moss ................................................................ 52a

Melvin B. Turner.................................................... 54a

J. E. Moss ................................................................ 55a

Order, October 7, 1960 .................................................. 61a

Relevant Docket Entries ............................................ la

11

PAGE

Report of the County Board of Education................. 64a

Exhibit “ A ” to Report ......... 65a

Plan ............................................................................ 69a

Specification of Objections to Plan ........................... 72a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing, October 24,

1960 ............................................................................... 77a

J. E. Moss ................................................................ 77a

Dr. Eugene W einstein............................................ 94a

Annie P. D river........................................................ 108a

Henry C. Maxwell .................................................. 110a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Judgment

November 23, 1960 ...................................................... 114a

Judgment .................................................................. 131a

Order, November 29, 1960 .............................................. 134a

Motion for New Trial and for Appropriate Relief .. 136a

Motion of Plaintiffs for Further Relief ................... 139a

Exhibit “A ” to Plaintiffs’ Motion ....................... 142a

Supplemental Answer ..................................................... 146a

Excerpts from Transcript of Hearing, January 10,

1961 .............................................. 149a

Joseph R. Garrett ...... 149a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Judgment 171a

Judgment .................................................................. 175a

Notice of Appeal ............................................................ 177a

A P P E N D I X

Relevant Docket Entries*

Civil Docket 2956

H e n r y C. M a x w e l l , Jr., et al.

—vs.—

C o u n t y B o ard o f E d u c a t io n o f

D a v id s o n C o u n t y , T e n n ., et al.,

9-19-60 Complaint filed.

9-19-60 Motion for Temporary Restraining Order-filed

by the Plaintiffs.

9-19-60 Motion for Preliminary Injunction—filed by the

Plaintiffs.

9-19-60 Order to Show Cause Why Temporary Restrain

ing Order and/or Preliminary Injunction Should

Not Issue—entered by Judge William E. Miller.

It is Ordered that the Defendants named herein

shall appear at 9 :00 A.M. on September 26, 1960

before Judge William E. Miller in U. S. District

Courtroom to show cause, etc. * * *

9-26-60 Motion to Dismiss filed by defendants. * * #

9-26-60 Affidavit of J. E. Moss filed by defendants in sup

port of Motion to Dismiss.

9-26-60 Affidavit of Frank White filed by defendants in

support of Motion to Dismiss.

Entries not relevant to this appeal have not been printed.

2a

9-26-60 Affidavit of Melvin B. Turner filed by defendants

in support of Motion to Dismiss.

9-26-60 Motion to Strike certain Portions of the Com

plaint filed by defendants. * * *

9- 26-60 Answer of defendants filed. * * *

10- 7-60 Order relative to hearing had on September 26,

1960, (1) Motions of plaintiffs for temporary re

straining order and/or preliminary injunction be

and the same is withheld at this time (2) defen

dants directed to file with the court, not later

than Oct. 19, 1960 a complete and substantial

plan which will accomplish complete desegrega

tion of public school system of Davidson County,

Tennessee (3) the plaintiffs will be furnished by

defendants with a copy of said plan and may file

objections thereto not later than October 21,

1960, the plaintiffs except to the action of the

Court in withholding action on their motions for

temporary restraining order and preliminary in

junction.

10- 19-60 Beport of the County Board of Education of

Davidson County, Tennessee, with Exhibit “A ”—

Beport of the Special Committee of the Davidson

County Board of Education,—attached, filed by

the Defendants. * * *

10- 21-60 Specification of Objections to Plan filed by

County Board of Education of Davidson County,

Tennessee, * * * , filed by the plaintiffs.

11- 9-60 Transcript of the Court’s Statement from the

Bench and of Proceedings Thereafter on Motion

of Defendants to Strike,—filed.

Relevant Docket Entries

3a

11-23-60 F indings of F act, Conclusions of L aw and

J udgment— entered by Judge William E. Miller.

It is accordingly Ordered, Adjudged and De

creed as follows:

(1) That the plan submitted by the County Board

of Education of Davidson County, Tennessee is

approved, except in the following particulars:

(a) Compulsory segregation based on race

is abolished in grades One through Four of

the Davidson County Schools for the Second

Semester of the 1960-61 school year begin

ning January 1961, and thereafter for one

additional grade beginning with each subse

quent school year, i.e., for Grade Five in

September 1961, Grade Six in September

1962, etc.

(b) As respects the summer classes attended

by outstanding students, there will be no

segregation based on races, and notice of

such will be immediately given by the School

Board to all teachers in the Davidson County

School system, both Negro and white, of the

availability of these classes.

(c) The Davidson County School Board will,

prior to the beginning of the Second Semes

ter of the 1960-1961 school year, and prior

to the beginning of each school year there

after, give specific notice to the parents of

all school children of the zone in which their

children fall for the purpose of attending

classes.

Relevant Docket Entries

4a

(2) The prayer of the plaintiffs for injunctive re

lief be, and the same is hereby denied, except

with regard to those matters as to which judg

ment is hereinafter reserved.

(3) Jurisdiction of this case is retained by the

Court throughout the period of transition.

(4) Judgment is reserved on the question of the

motion to strike and those portions of the mo

tion to dismiss not hereinbefore overruled, and

on the matters raised in the complaint which are

involved in said motions.

To the foregoing action of the Court in approving

the plan submitted by defendants and in denying

plaintiffs’ prayer for injunctive relief, the plain

tiffs except. * * *

11- 29-60 Order entered by Judge William E. Miller,

Ordering that the Defendants’ Motions to Strike

and to Dismiss those portions of the Complaint

relating to teacher and personnel assignment be

and they are hereby overruled, and that the de

fendants be and they are hereby allowed twenty

days from date in which to further plead to the

Complaint. The Court reserves judgment as to

the substantive questions involved, including the

questions of granting injunctive relief, pending

a further hearing after the issues have been fully

joined between the parties. * # *

12- 2-60 Motion for New Trial and for Appropriate Re

lief filed by the Plaintiffs.

12-12-60 Motion of plaintiffs for further relief filed. * * *

Relevant Docket Entries

5a

12-13-60 Supplemental Answer, pursuant to the Court

Order entered November 29, 1960,—filed by the

Defendants. * * *

1-18-61 Transcript of the Court’s Statement from the

Bench, on January 10, 1961 at Nashville, Tennes

see—filed by the 0. C. R. * * *

1-24-61 Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Judg

ment entered. * * # Ordered that: (1) Relief

prayed for in the motion for further relief filed

by plaintiffs be and the same is denied, with the

exception that the form of the notices to parents

in the future are directed to be mailed by defen

dants to counsel for plaintiffs in advance of mail

ing, so as to give them sufficient time to file with

the Court objections to the form of said notices.

(2) The aforesaid notices to parents will be given

to those who are affected by said plan of

desegregation heretofore approved by the

Court and not to anyone else.

(3) The Motion for a New Trial and for appro

priate relief filed by .Plaintiffs is overruled

and denied.

(4) Injunctive relief with respect to the issues

heretofore reserved by the Court concerning

assignment of teachers, principals and sus

taining personnel in the schools on basis of

race is denied at this time; and the Court

further reserves ruling with respect to the

assignment of teachers, etc., including the

right of school children or their parents to

raise such question.

Relevant Docket Entries

6a

(5) This case will remain on the docket of the

Court and the Court will retain jurisdiction

during the period of transition, etc.

(6) The Motion to intervene filed in this cause by

Porter Freeman is overruled and denied.

To the foregoing action of the Court in denying

their motion for further relief and their motion

for new trial and for appropriate relief, and in

denying the relief prayed for in the complaint

with respect to said issues heretofore reserved by

the Court, the plaintiffs respectfully except.

2-20-61 Notice of Appeal filed by the Plaintiffs. * * *

2- 20-61 Appeal Cost Bond filed by the Plaintiffs. * * *

3- 28-61 Order extending time to file record on appeal

to and including May 21, 1961, entered.

5-25-61 Order received for entry from the U. S. Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit extending time

to file record on appeal to and including May 31,

1961.

5-30-61 Transcript of Proceedings, filed (four Volumes)

Relevant Docket Entries

7a

Filed: September 19, 1960

I n the

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F or the M iddle D istrict oe T ennessee

N ashville D ivision

Civil Action No. 2956

C om p lain t

-,--------

H enry C. M axwell, Jr., and B enjam in Grower M axwell,

infants, by Rev. Henry C. Maxwell, Sr., and Mrs. Flora

Maxwell, their father and mother and next friends,

Cleophtjs D river, Christopher C. D river and D eborah D.

D river, infants, by Mrs. Annie P. Driver, their mother

and next friend,

D eborah R uth Clark, an infant, by Joe E. Clark and Mrs.

Floy Clark, her father and mother and next friends,

Jacqueline D avis, Shirley D avis, George D avis, Jr., R ob

ert Davis and R ita Davis, infants, by George Davis, Sr.,

and Mrs. Robbie Davis, their father and mother and

next friends,

R obert R ickey T aylor, an infant, by Robert Taylor and

Mrs. Stella Taylor, his father and mother and next

friends,

and

R ev. H enry C. M axwell, Sr., M rs. F lora M axwell, M rs.

A nnie P. D river, Joe E. Clark, M rs. F loy Clark,

George D avis, Sr., M rs. R obbie D avis, R obert T aylor,

M rs. Stella T aylor,

Plaintiffs,

8a

versus

County B oard of E ducation of D avidson County, T en

nessee, and F rank W hite, S. L. W right, Jr., E. K.

H ardison, Jr., F erriss C. B ailey, E. D. Chappell, A u

brey M axwell and Olin W hite , Board Members, who

together, as such Board Members, constitute the County

Board of Education of Davidson County, Tennessee;

and

J. E. Moss, County School Superintendent and/or Super

intendent of Public Instruction of Davidson County,

Tennessee,

Defendants.

Complaint

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action

arises under Section 1 and also the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States; and under the Act of May 31, 1870, Chapter

14, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144, (Title 42, United States Code,

Section 1981), as hereinafter more fully appears.

The matter in controversy exceeds, exclusive of interest

and costs, the sum or value of Ten Thousand ($10,000.00)

Dollars.

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343. This action is

authorized by the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter 22, Sec

tion 1, 17 Stat. 13, (Title 42, United States Code, Section

1983) to be commenced by any citizen of the United States

or other person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress

the deprivation, under color of a state law, statute, ordi

nance, regulation, custom or usage, of rights, privileges

9a

and immunities secured by Section 1, of the Fourteenth

Amendment, or any other provision of the Constitution

of the United States, and by the Act of May 13, 1870, Chap

ter 14, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144, (Title 42, United States

Code, Section 1981), providing for the equal rights of citi

zens and of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States, as hereinafter more fully appears.

2. This action is a proceeding under Title 28, United

States Code, Sections 2201 and 2202, for a judgment de

claring the rights and other legal relations of plaintiffs

and all other persons, similarly situated, eligible to attend

elementary and secondary schools owned, maintained and

operated by the County Board of Education of Davidson

County, Tennessee, in and for said County and State, and

demanding an injunction, for the purpose of determining

and redressing questions and matters of actual contro

versy between the parties, to-wit:

(a) Whether the custom, policy, practice or usage of

defendants in excluding plaintiffs and other persons simi

larly situated, from elementary and secondary schools

owned, maintained and operated by the County Board of

Education of Davidson County, Tennessee, solely because

of their race or color, and in operating a compulsory racially

segregated school system in and for said County and State,

pursuant to Sections 49-3701, 49-3702, and 49-3703, Ten

nessee Code Annotated, 1955, and that portion of Section

12 of Article 11 of the Tennessee Constitution which makes

it unlawful for white and colored persons to attend the

same school, and pursuant to any other law, custom, policy,

practice, or usage, violates the Equal Protection and Due

Process Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

Complaint

10a

3. Plaintiffs bring this action pursuant to Rule 23, (a)

(3) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure as a class action

for themselves and on behalf of all other persons similarly

situated, who are so numerous as to make it impracticable

to bring them all before the Court and who seek a common

relief based upon common questions of law and fact.

4. Plaintiffs are Negroes and are citizens of the United

States and of the County of Davidson and State of Ten

nessee. All adult plaintiffs are parents and/or guardians

of the infant plaintiffs, and reside with the infant plain

tiffs, in Davidson County, Tennessee. All of the infant

plaintiffs are school children, eligible to attend the public

schools of Davidson County, and have been attending said

schools, and can satisfy all requirements for admission to

the public schools maintained and operated by the defen

dant, County Board of Education, in and for Davidson

County, Tennessee, including the schools to which they

respectively applied as hereinafter shown.

5. (a) The defendant, County Board of Education of

Davidson County, Tennessee, is composed of the following

Board Members, the defendants, Frank White, S. L.

Wright, Jr., E. K. Hardison, Jr., Ferriss C. Bailey, E. D.

Chappell, Aubrey Maxwell, and Olin White, who, together,

constitute the County Board of Education of Davidson

County, Tennessee, and who are hereinafter referred to as

defendant, County Board of Education.

(b) Said defendant, County Board of Education, exists

pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the State of Ten

nessee as an administrative department or agency of the

State of Tennessee, discharging governmental functions,

and is by law, a body corporate or a continuous body or

Complaint

11a

entity, and is being sued herein as such corporate or con

tinuous body or entity.

(c) All of said defendants, above named as Board Mem

bers of defendant County Board of Education, are citizens

and residents of the State of Tennessee, and are being sued

herein in their official capacities as such Board Members,

and are also being sued herein as individuals.

(d) Defendant, J. E. Moss, is County School Superin

tendent or Superintendent of Public Instruction of David

son County, Tennessee and holds office pursuant to the

Constitution and laws of the State of Tennessee as an

administrative officer of the free public school system of

Tennessee. He is a citizen and resident of the State of

Tennessee, and is made defendant herein and sued in his

official capacity as stated hereinabove, and is also being

sued herein as an individual.

6. The State of Tennessee has declared public education

a State function. The Constitution of Tennessee, Article

11, Section 12, provides:

“ Knowledge, learning, and virtue, being essential to the

preservation of republican institutions, and the dif

fusion of the opportunities and advantages of educa

tion throughout the different portions of the State,

being highly conducive to the promotion of this end,

it shall be the duty of the General Assembly, in all

future periods of this Government, to cherish liter

ature and science.”

Pursuant to this mandate the Legislature of Tennessee

has established a uniform system of free public education

in the State of Tennessee according to a plan set out in the

Complaint

12a

Tennessee Code Annotated, 1955, Sections 49-101 through

49-3806, and supplements and amendments thereto. The

establishment, maintenance and administration of the pub

lic school system of Tennessee is vested in a Commissioner

of Education, a State Board of Education, County Super

intendents of Public Schools, and County and City Boards

of Education.

7. The public schools of Davidson County, Tennessee

are under control and supervision of defendant, County

Board of Education and defendant, J. E. Moss, acting as

an administrative department, division or agency, and as

an agent of the State of Tennessee. Said County Board of

Education is charged and vested with the administration,

management, government, supervision, control and conduct

of public schools within said County, and is vested with

all powers and duties pertaining to, connected with, or in

any manner incident to the proper conduct and control of

the public schools of said County. Said County Board of

Education is under a duty to enforce the school laws of the

State of Tennessee; to maintain an efficient system of public

schools in Davidson County, Tennessee; to determine the

studies to be pursued, the methods of teaching, and to

establish such schools as may be necessary to the complete

ness and efficiency of the school system. Defendant, J. E.

Moss, as Superintendent, has the immediate control of the

operation of the public schools of said County and is the

administrative agent for the defendant, Board of Educa

tion, and serves as a member of its executive committee.

8. Plaintiffs allege that the defendants herein, acting

under color of the laws of the State of Tennessee and

County of Davidson, have pursued and are presently pursu

ing a policy, custom, practice and usage of operating a com-

Complaint

13a

pulsory racially segregated school system in and for the

County of Davidson, State of Tennessee. The racially segre

gated school system operated by defendants consists of

a primary system of elementary, junior high, and high

schools limited to attendance by white children of the

County of Davidson. Said schools are staffed by white

teachers, white principals and white sustaining personnel.

Said white schools are located in various parts of the

County and, regardless of location, these schools may be

attended by white children only. The defendants also main

tain a secondary system of “ colored schools” or “Negro

schools” limited to attendance by Negro children. These

schools are likewise located in various parts of the County

and, regardless of location, are limited to attendance by

Negro children. These schools are staffed entirely by Negro

personnel; the teachers are all Negroes; the principals are

all Negroes; and the sustaining personnel are all Negroes.

This compulsory racially segregated school system is based

solely upon race and color; attendance at the various

schools is determined solely upon race and color and the

assignment of personnel is determined solely upon the

race and color of the children attending the particular

school and the race and color of the personnel to be as

signed. A dual set of school zone lines is also maintained.

These lines are based solely upon race and color. One set

of lines relates to the attendance areas for the Negro

schools and one set to the attendance areas for the white

schools. These lines overlap where Negro and white school

children reside in the same residential area. For many

years the defendants have adopted, maintained and en

forced, and they still maintain and enforce this custom,

policy, practice or usage of compulsory racial segregation

in the schools of Davidson County, Tennessee pursuant to

Complaint

14a,

which they have required and are still requiring all Negro

children, including the infant plaintiffs, to attend said

schools designated exclusively for Negro children.

9. From time to time since 1954 or 1955, Negro citizens

and residents of Davidson County have requested defen

dants to cease operating a compulsory racially segregated

public school system in Davidson County, Tennessee, and

to comply with the decision of the United States Supreme

Court in the School Segregation Cases. Defendants have

continued, however, to pursue the policy, practice, custom

and usage of operating a compulsory racially segregated

school system in Davidson County, Tennessee, and have

failed and have refused to formulate or adopt any plan

for desegregating the public school system of Davidson

County.

10. At the beginning of the school term, that is, to-wit;

on 2 September, 1960, the infant plaintiffs, Henry C. Max

well, Jr., and Benjamin Grover Maxwell, presented them

selves with their parents, and made proper and timely

applications for admission to G-lencliff Junior High School

and/or Antioch High School, but they were denied admis

sion by defendants to said said schools, solely on account

of plaintiffs’ race or color. On the same date, the infant

plaintiffs, Cleophus Driver, Christopher C. Driver, and

Deborah D. Driver, presented themselves, together with

their mother, and made proper and timely application for

admission to the Bordeaux Elementary School. In addi

tion, the plaintiff, Joe E. Clark, father of Deborah Ruth

Clark, also presented himself at that time and made proper

and timely application for admission of his daughter, the

infant plaintiff, Deborah Ruth Clark, to the Bordeaux E le-

Complaint

15a

mentary School. All of said plaintiffs were refused and

denied admission by defendants to the said Bordeaux Ele

mentary School, solely on account of plaintiffs’ race or

color. All of said infant plaintiffs reside in the zones of

the respective schools to which they applied, and would

have been admitted had they been white children. The

plaintiffs, Reverend & Mrs. Henry C. Maxwell, Sr. were

accompanied by the plaintiff, Mrs. Robbie Davis, whose

five minor children, the infant plaintiffs, Jacqueline Davis,

Shirley Davis, George Davis, Jr., Robert Davis, and Rita

Davis, are presently residing closer to a school designated

by the defendants as a “ Negro” school. However, Mrs.

Davis accompanied Reverend & Mrs. Maxwell, and she and

her husband, George Davis, Sr., and their minor children,

as well as the plaintiffs, Robert Taylor and wife, Stella

Taylor and their minor child, Robert Rickey Taylor, who

also is in the zone of and attends a “Negro” school, join

in this action for the reason that their said children are

being denied their right to enjoy a non-discriminatory

public education by reason of the compulsory racially

segregated public school system wdiich the defendants are

maintaining and operating in and for Davidson County,

Tennessee, as more fully shown hereinafter.

(a) Defendants’ requirement of compulsory racial segre

gation imposes unreasonable burdens upon the infant

plaintiffs and other Negro children similarly situated, who

live near and in the zone of readily accessible schools

Avhich white children living in the same area are permitted

to attend, but plaintiffs and all other Negro children are

refused admission to these schools and required to travel

great distances to “ Negro” schools, solely because of their

race or color. For instance, the infant plaintiffs, Henry

C. Maxwell, Jr., and Benjamin Grover Maxwell, who are

Complaint

16a

just entering Junior High School this year, reside within

a radius of two or three miles of Glencliff Junior High

School and Antioch High School, to either of which they

would be admitted if they were white, but because they

are Negroes, they and other Negro children similarly situ

ated, must walk a half mile or more each morning to a

school bus pick-up point, where they are picked up and

transported twelve miles all the way across town to a

“ Negro” school, and must make the return trip each eve

ning, arriving home at dusk. Similarly, the Driver and

Clark children named hereinabove as infant plaintiffs, and

all other Negro children, similarly situated, who reside in

their neighborhood, are within walking distances of the

Cumberland Junior High School and the Bordeaux Ele

mentary School, which latter school was destroyed by fire

on 9 September 1960, as hereinafter shown; but these chil

dren and all other Negro children similarly situated, are

required to travel by bus a distance of five or six miles or

more to Haynes School, designated by defendants as a

“ Negro” school. This unnecessary burden imposed upon

the infant plaintiffs, and other Negro children similarly

situated, solely because of race or color, subjects said chil

dren to unwarranted physical and health hazards, depriv

ing them in many instances of opportunities for athletic

and cultural development, and reduces their opportunities

for educational instruction and study. In addition, it places

an unwarranted burden upon the parents of the infant

plaintiffs and other Negro children, requiring them to arise

in the early hours of the morning in order to get them off

to school and depriving said parents, in many instances,

of their companionship and services in the afternoon, by

reason of the fact that many of them, particularly those

residing in the area of the Maxwell children, do not reach

Complaint

17a

home until late in the evening. Defendants refuse to admit

the infant plaintiffs to the schools as aforesaid, solely on

account of their race or color, the defendant, J. E. Moss,

having stated explicitly to one or more of the adult plain

tiffs that they were denied admission for this reason, and

that the Board of Education is committed to a policy of

compulsory segregation. As a matter of fact, the defen

dant, Board of Education, has officially stated its policy

of compulsory racial segregation by a motion passed and

entered upon the minutes of the Board at a meeting held

on 8 September, 1960, which reads substantially as fol

lows :

“We have fully considered the request of certain

Negro citizens who are parents of children in the

Davidson County School System to admit 4 children

as students in the Bordeaux Elementary School and 2

students to be admitted to Gleneliff High School.

Heretofore, numerous substantial Negro citizens of

this county have expressed their desire that their chil

dren attend Negro schools; and they also expressed

their pride in their own schools and confidence in their

teachers.

The Negro schools in Davidson County are in excel

lent condition and most of the schools have been built

within the last 10 years and the Negro schools are

equal in every respect to the white schools.

The request has been made by the parents of six

children from three Negro families. This request was

made after the current school year had started and

after all plans for transportation, zoning of students,

distribution of school books, etc., had been fully com

pleted for the county-wide system.

Complaint

18a

It is therefore moved that the Davidson County

Board of Education decline the request so made and

in making this motion, it is our feeling that we are act

ing in the best interest of the six Negro children men

tioned above.”

Plaintiffs aver that the class work in the Davidson

County School System, contrary to the foregoing statement

of the defendants, began on Tuesday, September 6, 1960,

some four days after the plaintiffs had presented them

selves and made application to the defendants for admis

sion to the schools requested, and were denied. Plaintiffs

further aver that some of the adult plaintiffs appeared at

the office of the defendant, J. E. Moss, on 31 August, 1960,

approximately two days prior to registration on 2 Sep

tember 1960, and sought an interview with the defendants,

at which time, one of the adult plaintiffs stated explicitly

that they were there requesting integration of the David

son County School System. Plaintiffs were informed by

said office that they would be given an appointment with the

defendant, J. E. Moss, for that purpose on Thursday, 1

September 1960. However, on the last mentioned date,

they were further informed by said defendant’s office, that

he would not see them until Tuesday, 6 September, 1960.

Plaintiffs thereupon presented themselves to the respec

tive schools for admission on registration day, 2 September,

1960, as aforesaid.

On the morning of 9 September, 1960, following said

action by the Board on 8 September, 1960, the Bordeaux

Elementary School was destroyed by fire. Although defen

dants have not made any public announcement as to the

disposition of the exclusively white school population of

said school, it is apparent from the defendants’ foregoing

Complaint

19a

policy, that they will continue to operate a compulsory

racially segregated school system and that new re-assign

ment of the students in said school will be made on this

basis.

(b) Plaintiffs aver that while some of them sought and

seek admission of their children to the respective schools

to which they applied as aforesaid, same being within their

zones, all of the plaintiffs further insist that the operation

of a compulsory racially segregated school system in David

son County violates rights of the plaintiffs and members of

their class which are secured to them by the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Federal Constitution. The compulsory racially segre

gated school system is predicated on the theory that

Negroes are inherently inferior to white persons and, con

sequently, may not attend the same public schools attended

by white children who are superior. The plaintiffs, and

members of their class, are injured by the policy of assign

ing teachers, principals and other school personnel on the

basis of the race and color of the children attending a

particular school and the race and color of the person to be

assigned. Assignment of school personnel on the basis of

race and color is also predicated on the theory that Negro

teachers, Negro principals and other Negro school person

nel are inferior to white teachers, principals and other

white school personnel and, therefore, may not teach white

children. Thus all of the plaintiffs are affected and injured

by defendants’ aforesaid policy, practice, custom, or usage,

whether they are thereby excluded from a white school

nearer their homes, or whether, on the other hand, they

are required to attend a school nearer their homes but

which is designated and stigmatized as a “ Negro” school,

Complaint

20a

from which all children of other racial extractions are

excluded.

11. The defendants rely on the following provisions of

the Tennessee Constitution and Statutes, which read as

follows:

Constitution of 1870, Act 11, Sec. 12:

“ . . . No school established or aided under this section

shall allow white and negro children to be received as

scholars together in the same school.. . . ”

Tennesse Code, 1955, Sections:

“ 49-3701. Interracial Schools prohibited.—It shall be

unlawful for any school, academy, college, or other

place of learning to allow white and colored persons

to attend the same school, academy, college, or other

place of learning. (Acts 1901, ch. 7, sec. 1; shan., sec.

6888a 37; Code 1932, sec. 11395).

“ 49-3702. Teaching of mixed classes prohibited,—It

shall be unlawful for any teacher, professor, or educa

tor in any college, academy, or school of learning, to

allow the white and colored races to attend the same

school, or for any teacher or educator, or other per

son to instruct or teach both white and colored races

in the same class, school, or college building, or in any

other place or places of learning, or allow or permit

the same to be done with their knowledge, consent, or

procurement, (Acts 1901 ch. 7, sec 2; shan., sec 6888a

38; Code 1932, sec 11396.)

“49-3703. Penalty for violations.—Any person violat

ing any of the provisions of this chapter, shall be

guilty of a misdemeanor, and, upon conviction, shall

Complaint

21a

be fined for each offense fifty dollars ($50.00), and im

prisonment not less than thirty (30) days nor more

than six (6) months. (Acts 1901, ch. 7, sec 3; shan.,

sec 6888a39; mod. Code 1932, sec 11397.)”

12. The infant plaintiffs and all other persons similarly

situated, in Davidson County, Tennessee, are thereby de

prived of their rights guaranteed by the Constitution and

laws of the United States.

Plaintiffs aver that the said constitutional and statutory

provisions and all other laws, customs, policies, practices

and usages of the State of Tennessee requiring or per

mitting segregation of the races in public education, fall

within the prohibited group which the Supreme Court of

the United States holds must yield to the Fourteenth

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States, and

are of no force and effect.

Plaintiffs therefore aver that the said custom, policy,

practice or usage of defendants in excluding plaintiffs and

other persons, similarly situated, from elementary and

secondary schools, owned, maintained and operated by the

County Board of Education of Davidson County, Ten

nessee, solely because of their race or color, and in operat

ing a compulsory racially segregated public school system

in and for said County, pursuant to said constitutional and

statutory provisions and any other law, custom, policy,

practice or usage of the State of Tennessee requiring or

permitting segregation of the Negro and white races in

public education, deprives plaintiffs and all others simi

larly situated of the equal protection of the laws in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States, and is therefore unconstitutional and

void and affords defendants no legal excuse to deprive

plaintiffs of their rights herein prayed.

Complaint

22a

13. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and affected,

on whose behalf this suit is brought, are suffering irrep

arable injury and are threatened with irreparable injury

in the future by reason of the acts herein complained of.

They have no plain, adequate or complete remedy to re

dress the wrongs and illegal acts herein complained of,

other than this suit for a declaration of rights and an in

junction. Any other remedy to which plaintiffs and those

similarly situated, could be remitted would be attended

by such uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial

relief, would involve multiplicity of suits, cause further

irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation and in

convenience, not only to the plaintiffs and those similarly

situated, but to defendants as governmental agencies.

Plaintiffs aver that as of the date of this complaint, the

classes in the public schools of Davidson County have been

in session only three days and that there is no reason why,

in view of the foregoing circumstances, their children should

not be immediately admitted to the said schools on a non-

discriminatory basis this school term. They further aver

that they will suffer irreparable injury in the future, un

less defendants are restrained by the temporary restrain

ing order and injunction of this Court for the reasons set

out hereinabove, and also, for the reason that, as aforesaid,

the defendants have explicitly indicated that they intend

to continue their compulsory segregation policy; and if the

plaintiffs and other Negro children similarly situated, are

not granted immediate relief now, they will be subjected

to the inherent evil and inequality of compulsory racial

segregation in the public schools for an indefinite period

of time, and immediate and lasting harm and damage will

result not only to them, but also to white children who

are thereby being indoctrinated daily with concepts of

themselves as a master or superior race while infant plain-

Complaint

23a

tiffs will be subjected daily to the said indoctrination clas

sifying them as an inferior race.

14. There is between the parties an actual controversy

as hereinbefore set forth.

W herefore, Plaintiffs respectfully pray:

The Court issue forthwith a temporary restraining order

against the defendants, immediately restraining and en

joining them and each of them, their agents, employees,

servants or attorneys, from refusing to admit the infant

plaintiffs to the said Glencliff Junior High School, Antioch

High School, and Bordeaux Elementary School, according

to their respective applications as set out hereinabove,

or any other public school operated by defendants in and

for Davidson County, Tennessee, on account of plaintiffs’

race or color, pending further orders of the Court.

The Court issue a preliminary injunction, restraining and

enjoining defendants and each of them, their agents, em

ployees, servants or attorneys, from refusing to admit

plaintiffs, and other persons similarly situated, to Glen

cliff Junior High School, Antioch High School, and Bor

deaux Elementary School, according to their respective

applications as set out hereinabove, or any other public

schools maintained and operated by defendant County

Board of Education in and for Davidson County, Ten

nessee, because of their race or color, pending further or

ders of the Court.

The Court adjudge, decree and declare the rights and

legal relations of the parties to the subject matter here

in controversy in order that such declaration shall have

the force and effect of a final judgment or decree.

The Court enter a judgment or decree declaring that the

custom, policy, practice or usage of defendants in main-

Complaint

24a

taining and operating a compulsory racially segregated

public school system in Davidson County, Tennessee, and

in excluding plaintiffs and other persons, similarly situ

ated, from Gleneliff Junior High School, Antioch High

School, and Bordeaux Elementary School, according to

their respective applications as set out hereinabove, or any

other public schools maintained and operated by defen

dant County Board of Education in and for Davidson

County, Tennessee, solely because of race, pursuant to the

above quoted portion of Article 11, Section 12 of the Con

stitution of Tennessee, Sections 49-3701, 49-3702, and

49-3703 of the Tennessee Code, 1955, and any other law,

custom, policy, practice and usage, violates the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution, and is there

fore unconstitutional and void.

The Court issue a permanent injunction forever restrain

ing and enjoining defendants and each of them, their

agents, employees, servants or attorneys, from maintaining

or operating a compulsory racially segregated public school

system in and for Davidson County, Tennessee, and from

refusing to admit plaintiffs, and other persons similarly

situated, to Gleneliff Junior High School, Antioch High

School, and Bordeaux Elementary School, according to

their respective applications as set out hereinabove, or

any other public schools maintained and operated by defen

dant, County Board of Education in and for Davidson

County, Tennessee, because of their race or color.

In addition to the immediate and preliminary relief

prayed hereinabove in behalf of the named infant plain

tiffs individually, the plaintiffs pray that this Court also

expeditiously enter a decree directing defendants to pre

sent a complete plan, within a period of time to be deter

mined by this Court, for the reorganization of the entire

Complaint

25a

school system of Davidson County, Tennessee, into a uni

tary, nonracial school system which shall include a plan

for the assignment of children on a nonracial basis, the

assignment of teachers, principals and other school per

sonnel on a nonracial basis, the drawing of school zone

lines on a nonracial basis, the allotment of funds, the con

struction of schools, the approval of budgets on a nonracial

basis, and the elimination of any other discriminations in

the operation of the school system or in the school cur

riculum which are based solely upon race and color. Plain

tiffs pray that if this Court directs defendants to produce

a desegregation plan that this Court will retain jurisdiction

of this case pending Court approval and full and complete

implementation of defendants’ plan.

Plaintiffs further pray that the Court will allow them

their costs herein and such further, other or additional

relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable and just.

Z. A lexander L ooby and

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood M arshall and

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 1790

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Complaint

(Duly verified.)

26a

Filed: September 19,1960

Come the plaintiffs, named in the caption hereinabove,

and move the Court to issue forthwith a temporary re

straining order against the defendants in this cause, im

mediately restraining and enjoining them and each of

them, their agents, employees, servants, or attorneys, from

refusing to admit the infant plaintiffs to Glencliff Junior

High School, Antioch High School, and Bordeaux Ele

mentary School, according to their respective applications

as set out in the complaint, or any other public school or

schools operated and/or maintained by said defendants

in and for Davidson County, Tennessee, on account of

plaintiffs’ race or color, pending further orders of the

Court.

And for grounds of said motion, the said plaintiffs

specify the matters and things alleged in their Complaint

filed herewith, all of which are incorporated herein by

reference and made a part of this motion.

Respectfully submitted,

Z. A lexander L ooby and

A von N. W illiams, Jr.,

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood M arshall and

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 1790

New York 19, New l rork,

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

M o tio n fo r T em p o ra ry R estraining O rd er

27a

Filed: September 26, 1960

Come the plaintiffs, named in the caption hereinabove,

and move the Court to issue a preliminary injunction

against the defendants in this cause, restraining and en

joining said defendants and each of them, their agents,

employees, servants or attorneys, from refusing to admit

the plaintiffs and other persons similarly situated, to Glen-

cliff Junior High School, Antioch High School, and Bor

deaux Elementary School, according to their respective ap

plications as set out in the complaint, or any other public

school or schools maintained and operated by the defen

dant County Board of Education of Davidson County,

Tennessee, in and for said County and State, because of

their race or color, pending further orders of the Court.

And for grounds of said motion, the said plaintiffs

specify the matters and things alleged in their complaint

tiled herewith, all of which are incorporated herein by

reference and made a part of this motion.

Respectfully submitted,

Z. A lexander L ooby and

A von N. W illiams, Jr.,

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T hurgood M arshall and

Jack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 1790

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

M o tio n fo r P relim in ary In ju n ction

28a

Order to Show Cause Why Temporary Restraining Order

and/or Preliminary Injunction Should Not Issue

Filed: September 26, 1960

In the above cause the plaintiffs having filed their verified

complaint together with Motions for a temporary restrain

ing order and a preliminary injunction against the defen

dants, for the purpose of immediately restraining and en

joining them and each of them, their agents, employees,

servants or attorneys, from refusing to admit the infant

plaintiffs, and other persons similarly situated, to Gflen-

cliff Junior High School, Antioch High School, and Bor

deaux Elementary School, according to their respective

applications as set out in the complaint, or any other pub

lic school or schools maintained and operated by the said

defendants in and for Davidson County, Tennessee, on ac

count of plaintiffs’ race or color, pending further orders of

the Court; and said motions being supported by the al

legations contained in the complaint properly referred to

and made a part thereof.

It is therefore Ordered that the defendants named in

the caption of the complaint in this cause, and each of them,

appear before the Honorable William F. Miller, H. S. Dis

trict Judge, at 9 :00 A.M., on Sept. 26, 1960, in U. S. Dis

trict Courtroom, Nashville, Tennessee, and show cause

why the aforesaid temporary restraining order and/or pre

liminary injunction should not issue.

W m. E. M il l e r

XJ. 8. District Judge

Vol. 23. Page 997September 19, 1960.

29a

Filed: September 26, 1960

The defendants jointly move to dismiss the complaint

filed against them in this cause upon the following grounds:

1. The complaint seeks extraordinary relief and pur

ports to be sworn to, but the jurat of the Notary Public

fails to contain any notarial seal, all as required by law.

2. The complaint seeks to attack and have declared un

constitutional and void Article II, Section 12, of the Con

stitution of Tennessee, and Sections 49-3701 through 49-

3703 of the Tennessee Code of 1955, without either the

State of Tennessee or its representative, the Attorney

General of the State of Tennessee, being made a party

thereto.

3. The complaint purports to be brought as a class

action by certain infant school children on behalf of all

other persons similarly situated without any showing that

there are other persons similarly situated who seek to at

tend any of the public schools of Davidson County, Tennes

see, which they are not now attending, or who would be

qualified to attend any such schools.

4. The complaint seeks to obtain a reorganization of

the entire school system of Davidson County, Tennessee,

insofar as teachers, principals and other school personnel

are concerned; whereas, no such persons are parties to the

complaint.

And the Defendants, and All of Them, Further Move to

Dismiss the Complaint Insofar as Extraordinary Relief

By Way of Temporary Restraining Orders and/or Pre

liminary Injunctions for the Reasons That:

1. These plaintiffs are seeking equitable relief of an

extraordinary nature and by their own admission have

M o tio n to D ism iss

30a

been guilty of laches in failing to make any application for

admission to the schools of Davidson County, Tennessee,

which they seek to attend until after all pupil assignment,

school zones, transportation facilities and the like had been

determined for the school year 1960-1961.

2. These plaintiffs are seeking equitable relief of an

extraordinary nature and have been guilty of laches over

the past several years in failing to seek admission to the

schools of Davidson County, Tennessee, which they seek to

attend and now seek to obtain such admission by means of

the exercise of such extraordinary relief through this Hon

orable Court.

And the Individual Defendants Move to Dismiss the Com

plaint Insofar as the Same is Filed Against Them

Individually for the Reason:

1. No action on the part of these defendants as in

dividuals has been recited in the complaint as the basis

for a complaint on the part of the plaintiffs, and, on the

contrary, such action as is complained of is under the

allegations of the complaint the official action of such

defendants.

Shelton L uton

County Attorney for

Davidson County, Tennessee

Davidson County Courthouse

Nashville 3, Tennessee

H aelan D odson, Jb.

1106 Nashville Trust Building

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Defendants

Motion to Dismiss

31a

Filed: September 26, 1960

J. E. Moss, being first duly sworn, deposes as follows:

That he is sixty-one (61) years of age and is a resident

of Davidson County, Tennessee, and has been superin

tendent of Davidson County Schools since 1949. That as

such he is the administrative head of the public schools of

Davidson County, Tennessee, and acts under the supervi

sion of the Davidson County School Board.

That the public schools of Davidson County have,

throughout his lifetime, been operated on a segregated

basis with separate schools for white and negro students.

That neither prior to nor since the decision of the Supreme

Court of the United States in 1955 in the case of Brown v.

The School Board has any request been made to him or of

him by any negro pupil or the parents of any negro pupil

in Davidson County, Tennessee, for the operation of the

schools of Davidson County on an integrated basis prior to

September 2, 1960. That neither has any group of negroes

or whites, by petition, letter, verbal communication or

otherwise, requested of the Davidson County School Board

that the schools of Davidson County be operated on an in

tegrated basis insofar as he is advised and that, in the event

any such request had been made, such would have in the

normal course of the operation of the School System been

communicated to him. That, on the contrary, on more than

one occasion delegations of negro pupils, or the parents of

negro pupils, have requested, either verbally or in writing,

that the School System of Davidson County be continued

on a segregated basis. That in September of 1955 the

County Board of Education of Davidson County was pre

sented with a petition for a new school building in the

Goodlettsville, Tennessee, area, which petition was signed

by the officers and practically all members of the Good-

A ffidavit o f J. E. M oss in S u p p o rt o f M otion

32a

lettsville Colored P. T. A. That this request contained the

express statement, “ We do not want integration in Good-

lettsville.” A copy of this said petition is attached hereto

as Exhibit “ A ” to this affidavit and the original of the same

is on file in the office of the Davidson County School Board.

That, pursuant to the request contained in said Exhibit

“A ” and in keeping with the over-all plans of the David

son County School Board, a new school was constructed in

the Goodlettsville, Tennessee, area serving the areas of.

Ridgetop and Goodlettsville. That in May of 1954, the

Davidson County School Board had under consideration

the construction of a consolidated school for negroes either

in the Neeley’s Bend area in the Eleventh Civil District

of Davidson County, or in the Hermitage area in the Fourth

Civil District of said County. At that time a large delega

tion of negroes from the Neeley’s Bend area appeared be

fore the School Board requesting that the school be built

in the Neeley’s Bend community and, when they were ad

vised by the School Board that a new white school had just

been built in that area, the group responded, in substance,

that they did not want their children to go to school at a

white school, but wanted a negro school on a completely

segregated basis. That, in other instances, various groups

of negroes and individual negroes have stated to affiant

and to others in affiant’s presence that they did not de

sire integrated schools, but, rather, wanted the schools

continued on a segregated basis.

Affiant further states that the data set forth on the at

tached sheet as Exhibit “ B” to this affidavit correctly re

flects the information contained thereon as reflected by the

records of the Davidson County Board of Education.

Affiant further states that negro children are housed in

better and more modern buildings than white children,

Affidavit of J. E. Moss in Support of Motion

33a

since, for the most part, they are in new units. All of the

school buildings housing negro children have been built

within the past twelve (12) years excepting the Early

School in the Eighth Civil District of Davidson County and

a portion of Haynes High School located in the Twelfth

Civil District. These latter two units, however, have been

modernized and are above average in the County for

schools. Affiant further states that all of the facilities

in both the negro and white schools are modern and com

parable. Affiant further states that negro schools operate

on the same fiscal policy as white schools in that the alloca

tion of funds is on a per pupil basis with both races receiv

ing funds under the same formula and that equal opportuni

ties are afforded as to courses of study, text books, instruc

tional material and equipment. Affiant further states that

the teacher-pupil ratio for the negro pupils is 29.35 pupils

per teacher and the ratio in the white schools is 28.92 pupils

per teacher.

Affiant further makes oath that, in the spring of each

year before the conclusion of the school year, a pre-school

spring registration is held in order to give information

as to the number of students and location of the same for

the next school year. That Henry C. Maxwell, Jr. and Ben

jamin Grover Maxwell, both of whom are plaintiffs in the

instant suit, completed their elementary schooling in the

spring of 1960 at the Providence Public School. That dur

ing the spring registration in 1960 both of these pupils

registered at Haynes High School for attendance there

during the school year 1960-1961. That Cleophus Driver,

Christoper C. Driver and Deborah D. Driver, plaintiffs in

the instant case, were students at Haynes Elementary

School during the school year 1959-1960 and, having re

ceived no advice of their intention to move or change their

Affidavit of J. E. Moss in Support of Motion

34a

schools, their names were carried forward as expected to

be in attendance at Haynes Elementary School during the

school year of 1960-1961. That the same situation with

respect to Deborah Ruth Clark existed as with the Driver

children. That the method of anticipation of attendance

during the school year 1960-1961 was the same for the

children listed as plaintiffs in the instant case as it was

for all of the other children in Davidson County, Tennessee,

similarly situated. That, in the spring of each year, the

principals of each of the schools make their requests or

requisitions to the School Board for the books which they

will need during the ensuing year and, at that time, make

their requests for rooms, temporary housing facilities, when

needed, and for their teachers, all for the next school year

and, based upon these requests, the Board of Education pre

pares and submits its request to the County Court for

school funds for the next year. Of course, there are in

stances where students, for various reasons, change from

one school to another, but such is not permitted by affiant

or the School Board without some justification and any

alteration of the planning and programming by any sub

stantial group of students changing schools would com

pletely disrupt and disorganize the school system. Affiant

further states that any attempt on his part, or on the part

of the Davidson County School System, to change from a

segregated school system to an integrated school system

on August 31, 1960, or thereafter, without substantial pre

liminary planning, would have been chaotic in the adminis

tration of the school system.

That since the unfortunate incident of the burning of

the Bordeaux Elementary School on September 9, 1960,

your affiant and the School Board have been making every

effort, through the use of makeshift classrooms, repair

Affidavit of J. E. Moss in Support of Motion

35a

work, use of temporary facilities such as churches and the

like, and transportation of pupils to schools operated by

the City of Nashville, to furnish facilities for the student

body of this school. This situation has created and is con

tinuing to create great confusion, hardship and difficulty

on pupils, parents and school officials, and any further

problems in the operation and administration of this school

at this time would be highly undesirable.

Further this affiant saith not.

J. E. Moss

Affidavit of J. E. Moss in Support of Motion

Sworn to and subscribed before me, this 26th day of

September, 1960.

H elen M. H utchison

Notary Public.

My commission expires:

Oct. 19, 1960

(Seal)

36a

EXHIBIT “A ” TO AFFIDAVIT OF J. E. MOSS

Agenda Goodlettsville, Term.

Sept. 12,1955

County Broad of Ed.

We the parents want a better and more comfortable

school in Goodlettsville. We want a consolidated school

with Bidgetop, Amqui, & Edenwold communities.

We do not want Integration in Goodlettsville.

We need a janitor for at least five months, since there is

not a child in school old enough for the responsebility of

the job.

We want cool water in summer months.

We need a new school because it’s impossible for one

teacher to teach (8) eight grades under present conditions

and give our children the attention and justice they deserve

Signed by Goodlettsville Colored P. T. A.

Mrs. Alice Cantrell—pres.

Mrs. Beulah Cartwright—Asst. Sec.

Mrs. Mattie Cartwright Sec.

Mrs. Beatrice Vaughn

Mrs. Lula Joyner

Mrs. Jessie H. Jones

Mrs. Bessie Patton

Mrs. Mamie Washington

Mrs. Bobbie Washington

Mrs. Sadie Bell Cartwright

Mrs. Ester Louise Matthews

Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Mathews

Mrs. Hattie M. Stanton

Mrs. Mary Sue Cantrell

Mrs. Rizzie Mae Joyner

Mrs. Willie Johnson

Mrs. Maud Joyner

Ernest Matthews

37a

EXHIBIT “ B” TO AFFIDAVIT OF J. E. MOSS

Data on D avidson County S chools

Total number of white children 44,415

Total number of negro children 2,348

Total number of County students 46,763

Total number of negro elementary schools 7

Total number of negro high schools 1

Total number of white elementary schools 62

Total number of white high schools 16

Percentage of white children 95

Percentage of negro children 5

Number of white teachers 1,536

Number of negro teachers 80

Number of white central office supervisors 20

Number of negro central office supervisors 1

Percentage of negro central office supervisors 5

Trend of population for the last five years:

White Negro Total

1956 35,270 2,001 37,271

1957 37,551 2,032 39,583

1958 40,152 2,089 42,241

1959 42,614 2,281 44,895

1960 44,415 2,348 46,763

Percentage increase in the last five years-—white 26

Percentage increase in the last five years-—negro 17

Average salary 1959-60

Negro women

White women

Negro men

White men

$4,665.30

$4,380.97

$4,849.96

$4,529.35

* Taken from annual report to State Department

38a

Filed: September 26, 1960

Frank White, being duly sworn, deposes and says:

That he is a resident of Davidson County, Tennessee,

and has been all his life ; that he served as Chairman of the

Davidson County School Board from September of 1958

until September 22, 1960, and has served as a member of

the Davidson County School Board for more than twenty

years.

That at no time prior to September 2, 1960, was any re

quest ever communicated to the Davidson County School

Board to his knowledge, either formally or informally, for

a desegregation of the Public School System of Davidson

County, and that if such had been communicated he would

probably have known of it and, during the last two years

as Chairman of the School Board, would have been the

person on the School Board to whose attention such would

have been directed. That plans for the assignment of

teachers, pupils, books, transportation facilities and hous

ing facilities for a school year are made in the spring next

preceding the school year and that any attempt to make a

complete change in the same at the beginning of the school

year as would be necessitated by desegregation of the

schools would be practically impossible without a complete

disruption of the entire school program.

That rather than there being requests for desegregation

of the School System, the only communications which have

been addressed to the School Board by either negroes or

whites have been requests for a continuation of segregated

schools. That two specific instances of such requests were

in connection with the request of the Neeley’s Bend group

of negroes and the Goodlettsville Colored P. T. A., both

A ffidavit o f F ran k W h ite in S u p p ort o f M otion

39a

of which are correctly reflected in the affidavit of J. E.

Moss, which is adopted as to these particulars by affiant.

Affiant further makes oath that any attempt to evolve

a plan of desegregation of the Davidson County Public

School on an orderly basis would require substantial plan

ning, data accumulation and the like by the School Board

and its staff and would consume a several months’ period

of time.

Further affiant saith not.

F rank P. W hite

Affidavit of Frank White in Support of Motion

Sworn to and subscribed before me, this 26th day of

September, 1960.

H elen M. H utchison

Notary Public.

My commission expires:

Oct. 19,1960

( S e a l )

40a

Filed: September 26,1960

Melvin B. Turner, being duly sworn, deposes and says:

That he is forty-five (45) years of age, is a resident of

Davidson County, Tennessee, and is transportation super

visor for the Davidson County Schools. That as such it is

his duty and responsibility to provide public school bus

transportation for all pupils attending Davidson County

Public Schools who are eligible for or require such public

transportation. That the Davidson County School System

operates ten (10) routes serving negro school children

and eighty-seven (87) routes serving white school children.

That the percentage of negro children transported by public

school buses of the Davidson County system is 55% and

that of white children transported by such system is 48%

of the total respective enrollments.

Affiant, further states that, by reason of the minimum

distance requirement for public school bus transportation,

children living several miles from school have an advan

tage over those living near the school in that a child living-

less than one and one-quarter miles from school must

walk or furnish his own transportation while those living

farther than said distance are furnished public transporta

tion by the County School System. That a child living ten

or twelve miles from school is delivered in a safe, modern

bus in approximately the same time it would take a child

living a mile from school to walk the distance; that the

child on the bus is protected from the traffic hazards to

which the pedestrian child would be subjected.

That affiant knows where the plaintiffs Maxwell reside,

which residence is approximately four-tenths of a mile

from Nolensville Road and up a dead-end street; that the

Affidavit o f M elv in B . T u rn e r in S u p p o rt o f M otion

41a

County public school bus which transports white students

to Antioch High School would use the same pick-up point

were there any white students to pick up at this corner

where infant plaintiffs Maxwell take the negro school bus.

That even though the distance from plaintiffs Maxwells’

said residence to Haynes High School is greater than that

to Antioch High School, the actual time consumed en route

by bus is approximately the same; that this results from

the fact that the route travelled by the bus to Haynes

High School is more direct and requires fewer stops than

that to Antioch High School.

That the infant plaintiffs Driver and Clark live approxi

mately one mile from Bordeaux Elementary School, which

fact would preclude them from being eligible for public

school bus transportation; that said infant plaintiffs Driver

and Clark, in riding the County School System bus from

their home to Haynes High School, as they have been

doing, consume no more than the amount of time which it

would take them to walk from their said residence to Bor

deaux Elementary School.

Further this affiant saith not.

M elvin B. T urner

Affidavit of Melvin B. Turner in Support of Motion

Sworn to and subscribed before me, this 26th day of

September, 1960.

My commission expires:

Oct. 19,1960

(Seal)

H elen M. H utchison

Notary Public.

42a

Motion to Strike Certain Portions of the Complaint

Filed: September 26, 1960

The defendants, and each of them, move to strike cer

tain portions of the complaint as follows:

1. The defendants move to strike that portion of Para

graph 10 of the complaint which reads as follows:

“ The plaintiffs, and members of their class, are injured

by the policy of assigning teachers, principals and

other school personnel on the basis of the race and

color of the children attending a particular school and

the race and color of the person to be assigned. As

signment of school personnel on the basis of race and

color is also predicated on the theory that Negro

teachers, Negro principals and other Negro school per

sonnel are inferior to white teachers, principals and

other white school personnel and, therefore, may not

teach white children.”

2. The defendants move to strike that portion of the

complaint set forth as a part of the sixth ground of relief

asked and specifically being that part reading as follows:

“ which shall include . . . the assignment of teachers,

principals and other school personnel on a nonracial

basis.”

Shelton L uton

County Attorney for

Davidson County, Tennessee

Davidson County Courthouse

Nashville 3, Tennessee

H arlan D odson, Jr.

1106 Nashville Trust Building

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Defendants

43a

Filed: September 26,1960

The defendants, and each of them, for answer to the

complaint filed in this cause and answering say:

1, 2 and 3.

The defendants admit the averments of Sections 1, 2 and

3 of the complaint.

4.

Defendants assume that the allegations of Section 4 of

the complaint are true, but neither admit nor deny the

averments since they are without sufficient information to

respond thereto.

5.

These defendants admit the allegations of Section 5 of

the complaint.

6.

These defendants admit the factual averments of Sec

tion 6 of the complaint, but neither admit nor deny the

plaintiffs’ conclusions based thereon.

7.

These defendants admit the allegations of Section 7 of

the complaint.

8.

These defendants admit that they are and have been

operating racially segregated schools as the school system

of Davidson County, Tennessee, but they deny that the

Negro schools are a secondary system of schools. Subject

A n sw er

44a

to the explanations and exceptions hereinafter set forth,

these defendants admit the other allegations of Section 8

of the complaint.

9.

These defendants expressly deny the allegations of the

first sentence of Section 9 of the complaint, and, on the con

trary, would show to the Court that the requests which

they have had from Negro citizens and residents of David

son County prior to September 2, 1960, have been for a

continuation of racially segregated schools.

10.

These defendants admit that on September 2, 1960, the

infant plaintiffs, Henry C. Maxwell, Jr., and Benjamin

Grover Maxwell, presented themselves with their parents

and made application for admission to the Gleneliff Junior

High School, but these defendants deny that such applica

tion was made timely or that it was made to the Antioch

High School and deny that they could have been admitted

to the Gleneliff Junior High School, whether white or

Negro, but admit that they were denied admission to the

Gleneliff Junior High School by reason of race or color.

These plaintiffs were seeking admission to the ninth grade

of Gleneliff Junior High School. These defendants further

admit that the infant plaintiffs, Cleophus Driver, Chris

topher C. Driver and Deborah D. Driver, presented them

selves with their mother and made application for admis

sion to the Bordeaux Elementary School, Cleophus Driver

seeking to enter the sixth grade, Christopher C. Driver

seeking to enter the fourth grade and Deborah D. Driver

seeking to enter the second grade, but they deny that such

application was timely. These defendants further admit

Answer

Answer

that the plaintiff, Joe F. Clark, presented himself at the

Bordeaux Elementary School and sought admission of his

daughter, Deborah Ruth Clark, to the fifth grade thereof,

but they deny that this application was timely. These de

fendants are not advised as to the children of the plaintiff,

Mrs. Robbie Davis, or as to the child of Rebert Taylor