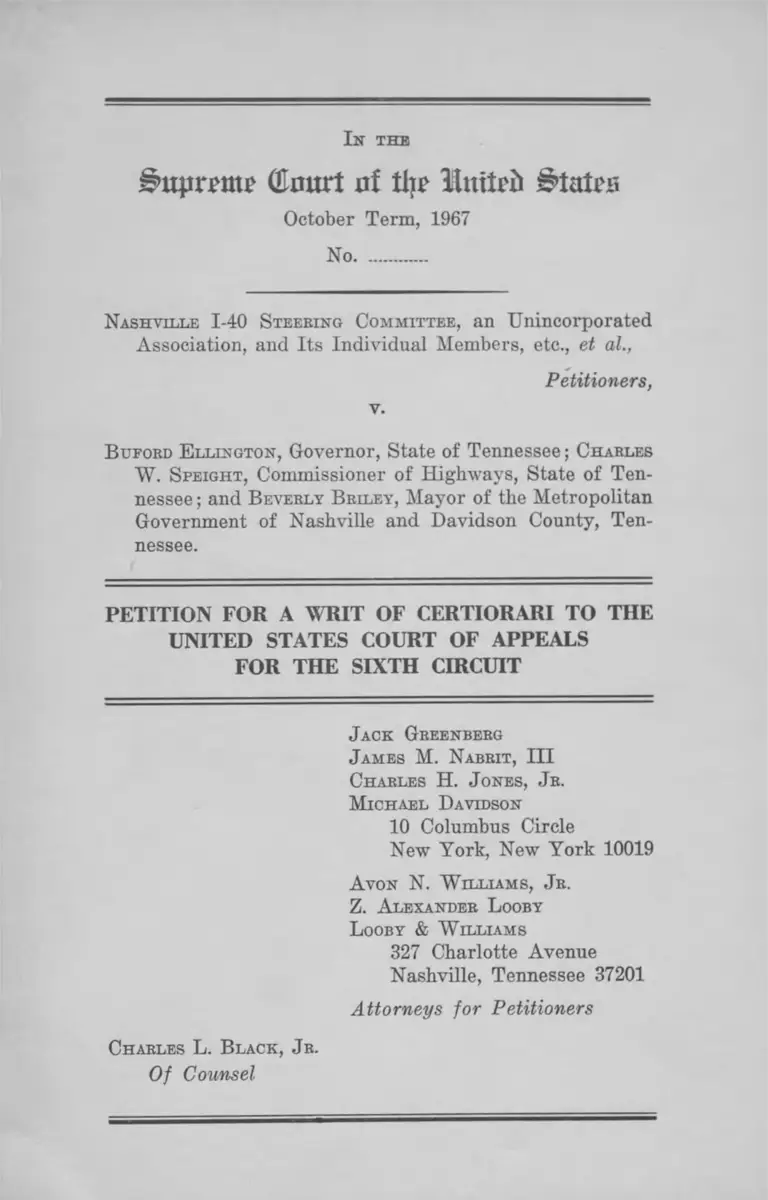

Nashville I-40 Steering Committee v. Ellington Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

December 18, 1967

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Nashville I-40 Steering Committee v. Ellington Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1967. d508a509-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/0f972e66-757d-49e0-9216-1d2ace4ea083/nashville-i-40-steering-committee-v-ellington-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(ftmtrt ai tl|? lilnitpii States

October Term, 1967

No..............

Nashville 1-40 Steering Committee, an Unincorporated

Association, and Its Individual Members, etc., et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

B uford E llington, Governor, State of Tennessee; Charles

W . Speight, Commissioner of Highways, State of Ten

nessee ; and B everly B riley, Mayor of the Metropolitan

Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Ten

nessee.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles H. Jones, Jr.

M ichael Davidson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A von N. W illiams, Jr.

Z. A lexander L ooby

L ooby & W illiams

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville, Tennessee 37201

Attorneys for Petitioners

Charles L. B lack, Jr.

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below .......................................... 2

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ......................................................... 2

Statute and Regulation Involved.................................... 3

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 5

Summary of Proceedings in the Courts B elow ..... 5

Summary of Facts ...................................................... 7

R easons foe Granting the W rit—

I. Introduction........................................................... 17

II. The Highway Route Is Racially Discriminatory

in Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment..... 21

III. There Was no Public Hearing With Proper

Notice as Required by the Federal Highway

Statute ................................................................... 23

IV. There Was no Consideration of the Economic

Effects of the Highway Route as Required by

Federal Law .......................................................... 28

V. The Balance of Equities Favors Petitioners .... 34

PAGE

Conclusion 37

11

T able of Cases

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715 ..................................................................................... 23

City of Pittsburgh v. F.P.C., 237 F.2d 791 (D.C. Cir.

1956) ................................................................................. 32

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 .............................. 22

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 .......................... 22

Harper v. State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 ....... 28

Hoffman v. Stevens, 177 F. Supp. 898 (M.D. Pa. 1959) 24

Land v. Dollar, 330 U.S. 731 .......................................... 20

Larson v. Domestic & Foreign Commerce Corp., 337

U.S. 682 ........................................................................... 20

Linnecke v. Department of Highways, 76 Nev. 26, 348

P.2d 235 (1960) ............................................................. 23, 24

Office of Communication of United Church of Christ v.

F.C.C., 359 F.2d 994 (D.C. Cir. 1966) ........................... 28

Piekarski v. Smith, 38 Del. Ch. 402, 147 A.2d 176

(1958), aff’d 153 A.2d 587 (Sup. Ct. Del. 1959) ....... 24

Road Review League v. Boyd, 270 F. Supp. 650 (S.D.

N.Y. 1967) .................................................................... 28

Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal

Power Commission, 354 F.2d 608 (2nd Cir. 1965),

cert. den. 384 U.S. 941 .................................. 6, 28, 29, 30, 31

State Highway Commission v. Danielsen, 146 Mont.

539, 409 P.2d 443 (1965) .................................................. 31

PAGE

m

PAGE

Texas East Trans. Corp. v. Wildlife Preservers, Inc.,

48 N.J. 261, 225 A.2d 130 (1966) .............................. 31,32

United States v. General Motors Corp., 323 U.S. 373 20

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 .................................. 22

Statutes I nvolved

23 C.F.R., §1.6..................................................................... 4

The Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Develop

ment Act of 1966, 80 Stat. 1255, 42 U.S.C. §3301 ....... 26

Department of Transportation Act, Sections 2(a),

4 (f), 80 Stat. 931, 49 U.S.C. §§1651(a), 1653(f) ....... 31

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1950, 64 Stat. 791 ......... 25

Section 116(c), Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, 70

Stat. 385, 23 U.S.C. §§101 et seq............. 2, 3, 5,10, 23, 24,

28, 29, 30, 32

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, 70 Stat. 385, Sec

tions 116(a), 116(b) ...................................................... 30

Federal-Aid Highway Act, of 1958, 72 Stat. 89 ........... 3

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1966, 80 Stat. 766, 23

U.S.C. §138 ..................................................................... 31

P.L. 85-767, 72 Stat. 885, 902 .......................................... 3

United States Housing Act of 1949, 63 Stat. 416, 42

U.S.C. §1455 (c) .............................................................. 26

23 U.S.C. §106..................................................................... 11

23 U.S.C. §128..................................................................... 3

IV

23 U.S.C. §304 ..................................................................... 30

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............................................................. 2

28 U.S.C. §§1331(a), 1343(3) ............................................ 5

42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1982, 1983, 2000d.................................. 5

Other A uthorities

Bureau of Public Roads Policy and Procedure Memo

randum 20-8..................................................................... 26

96 Cong. Rec. 13005, 13006 (1950) ............................ 25, 26, 31

House Committee on Public Works, 90th Cong. 1st

Sess., Highway Relocation Assistance Study (Comm.

Print No. 9, July 1967) .................................................. 18

H.R. Rep. No. 2436, 84th Cong., 2nd Sess., 36 (1956) .... 25

New York Times, November 13, 1967, Late City Edi

tion, p. 1, “U. S. Road Plans Periled by Rising Urban

Hostility.” ......................................................................... 17

New York Times, December 31, 1967, page E-7, “White

Roads Through Black Bedrooms.” .............................. 18

Rand-McNally Highway Atlas of the United States,

43rd Ed. 1967 ................................................................... 7

Reich, The Law of the Planned Society, 75 Yale L. J.

1227 (1966) ..................................................................... 18

S. Rep. No. 2044, 81st Cong., 2nd Sess., 8 (1950) ........... 25

Senate Subcommittee on Public Roads, Hearings to

Review Policies Relating to Urban Highway Plan

ning Design and Location ............................................ 18

PAGE

V

Stern and Gressman, Supreme Court Practice, 3rd Ed.,

PAGE

U. S. Department of Housing and Urban Development,

Urban Renewal Manual, §10-1...................................... 26

4 Wigmore on Evidence, 3d Ed., §1352 .......................... 33

9 Wigmore on Evidence, 3d Ed., §2534 .......................... 33

In t h e

^uprrmp (Unurt uf tlir Ituitrii Stairs

October Term, 1967

No..............

Nashville 1-40 S teebing Committee, an Unincorporated

Association, and Its Individual Members, etc., et al,

v.

Petitioners,

B ufokd E llington, Governor, State of Tennessee; Charles

W. S peight, Commissioner of Highways, State of Ten

nessee ; and B everly B riley, Mayor of the Metropolitan

Government of Nashville and Davidson County, Ten

nessee.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit, entered in the above entitled case on

December 18, 1967.1 1

1 The petitioners are Nashville 1-40 Steering Committee, an unincor

porated association, and its members, Flournoy A . Coles, Jr., Chairman;

and Mansfield Douglas, III , Newt A . Solomon, Inman Otey, Flem B.

Otey, III , Harold M. Love, William H. Fort, N. E. Douglas, J. L. Camp

bell, A . L. Porter, J. E. Vaughn, H. H. Turpen, Eleanor Landreau, Paul

Puryear, Leonard Beech, Parker Coddington, Louis Aatdl, Andrew White,

Nelson Fuson, E. H. Mitchell, Noella Mitchell, Henry Tomes, N. Samuel

Jones, Marian Fuson, D. W . Williams, L. L. Dickerson, Webster Cash,

James L. Garrett, Odessa Hoggatt and Martha Ragland.

2

Citations to Opinions Below

The memorandum opinion of the District Court, filed

November 2, 1967, is unreported and is printed in the ap

pendix, infra pp. la-3a. The opinion of the Court of Ap

peals is not yet reported and is printed in the appendix,

infra pp. 4a-16a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

December 18, 1967 (appendix p. 18a, infra). The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. Section

1254(1).

Questions Presented

Whether petitioners are entitled to an injunction re

straining the construction in North Nashville, Tennessee,

a predominantly Negro area, of a three mile section of an

interstate highway which traverses Tennessee, on the

ground that:

(1) The route is racially discriminatory, in violation of

the due process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States;

(2) State highway officials failed to comply with Section

116(c) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 (70 Stat.

385) by not having a public hearing with proper notice on

the proposed route;

(3) State highway officials failed to comply with Section

116(c) mandating a consideration of the “economic effects”

of proposed highway location.

3

Statute and Regulation Involved

1. Section 116(c) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of

1956, 70 Stat. 385, provides as follows:2

Sec. 116. Declarations Of Policy With Respect To

Federal-Aid Highway Program.

• • •

(c) Public Hearings.—Any State highway depart

ment which submits plans for a Federal-aid highway

project involving the bypassing of, or going through,

any city, town, or village, either incorporated or un

incorporated, shall certify to the Commissioner of Pub

lic Roads that it has had public hearings, or has af

forded the opportunity for such hearings, and has

considered the economic effects of such a location:

Provided, That, if such hearings have been held, a copy

2 The currently applicable law, which the court below said does not

differ materially from the 1956 version quoted above, is found in 23

U.S.C. §128. The amendments to the 1956 version were added by the

Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1958, 72 Stat. 89. The laws were recodified

and Title 23 was enacted into positive law by P.L. 85-767, 72 Stat. 885,

902. The current 23 U.S.C. §128 states:

§128. Public hearings.— (a) Any State highway department which

submits plans for a Federal-aid highway project involving the by

passing of, or going through, any city, town, or village, either in

corporated or unincorporated, shall certify to the Secretary that

it has had public hearings, or has afforded the opportunity for such

hearings, and has considered the economic effects of such a loca

tion. Any State highway department which submits plans for an

Interstate System project shall certify to the Secretary that it has

had public hearings at a convenient location, or has afforded the

opportunity for such hearings, for the purpose of enabling persons

in rural areas through or contiguous to whose property the high

way will pass to express any objections they may have to the pro

posed location of such highway.

(b) When hearings have been held under subsection (a), the State

highway department shall submit a copy of the transcript of said

hearings to the Secretary, together with the certification. (Aug. 27,

1958, P.L. 85-767, 72 Stat. 902.)

4

of the transcript of said hearings shall be submitted

to the Commissioner of Public Roads, together with the

certification.

2. Title 23, C.F.R., §1.6 Federal-aid highway systems.

(a) Selection or designation. To insure continuity

in the direction of expenditures of available funds,

systems of Federal-aid highways are selected or desig

nated by any State that desires to avail itself through

its State highway department of the benefits of Federal

aid for highways. Upon approval by the Administrator

of the selections or designations by a State highway

department, such highways shall become portions of

the respective Federal-aid highway systems, and all

Federal-aid apportionments shall be expended thereon.

(b) Revisions. A State highway department may

propose revisions, including additions, deletions or

other changes, in the routes comprising the approved

Federal-aid highway systems. Any such revision shall

become effective only upon approval thereof by the

Administrator upon a determination that such revision

is in the public interest and consistent with Federal

laws. There is no predetermined time limit for the

submission of the full selection of the systems.

(c) Selection considerations. Each Federal-aid sys

tem shall be so selected or designated as to promote

the general welfare and the national and civil defense

and to become the pattern for a long-range program

of highway development to serve the major classes of

highway traffic broadly identified as (1) interstate or

interregional; (2) city-to-city primary, either interstate

or intrastate; (3) rural secondary or farm-to-market;

and (4) intraurban. The conservation and development

of natural resources, the advancement of economic

5

and social values, and the promotion of desirable land

utilization, as well as the existing and potential high

way traffic and other pertinent criteria are to be con

sidered when selecting highways to be added to a

Federal-aid system or when proposing revisions of a

previously approved Federal-aid system.

(d) * * *

(e) * * ‘

(Published in the Federal Register, 25 F.R. 4162, May

11, 1960).

Statement of the Case

Summary o f Proceedings in the Courts Belou)

Petitioners seek an injunction restraining consrtuction of

a three-mile segment of Interstate Highway 40 (hereinafter

called 1-40) which has been routed so as to pass through a

Negro neighborhood in Nashville, Tennessee known as

North Nashville. The proceedings below were greatly ex

pedited. The complaint filed October 26,1967, in the District

Court for the Middle District of Tennessee, alleged federal

jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §§1331 (a) and 1343(3) and 42

U.S.C. §§1981,1982,1983 and 2000d. Petitioners assert that

the proposed route is racially discriminatory in violation of

their Fourteenth Amendment rights and also that the

state highway department failed to comply with Section

116(c) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 by not giv

ing proper notice of a public hearing on the proposed route

and by not adequately considering the “ economic effects”

of the proposed route in accordance with federal statutory

requirements. Petitioners are a group of thirty business

men, ministers, faculty members of Fisk, Meharry and

Vanderbilt Universities, officials of civic and civil rights

organizations, and residents of North Nashville who formed

6

an association to oppose the proposed routing of 1-40. Re

spondents are the Governor of Tennessee, the State Com

missioner of Highways and Nashville’s Metropolitan

Mayor.

When suit was filed the District Court promptly held an

evidentiary hearing on a motion for preliminary injunction.

The District Court denied relief, finding that although peti

tioners proved that “ the proposed route will have an ad

verse effect on the business life and educational institutions

of the North Nashville community” and that “ the considera

tion given to the total aspect of the link on the North Nash

ville community was inadequate,” there was no proof of

“ a deliberate purpose to discriminate” racially (2a). The

Court rejected plaintiffs’ statutory arguments stating that

they were matters to be decided by the Bureau of Public

Roads of the Department of Transportation (la ). The ac

tion was dismissed as to the Mayor of Metropolitan Nash

ville and Davidson County (la ).

To preserve the status quo pending appeal a panel of the

Sixth Circuit on November 13, 1967, restrained the Com

missioner of Highways from proceeding with construction

of the road segment or awarding contracts. After an ex

pedited appeal, the Court of Appeals affirmed, except as to

the order dismissing the cause against Mayor Briley which

was reversed (15a-16a). The per curiam opinion rendered

December 18, 1967, upheld petitioners’ standing to main

tain the action, relying upon Scenic Hudson Preservation

Conference v. Federal Power Commission, 354 F.2d 608

(2nd Cir. 1965), cert. den. 384 U.S. 941 (6a-7a). The Court

ruled that the notice of the public hearing on the road was

given in “an unsatisfactory way” and that the incomplete

transcript of the hearing “leaves much to be desired,” but

nevertheless declined to grant relief stating that due to ex

tensive publicity no literate citizen of the community could

7

have been unaware of the approximate location of the high

way (7a). The petitioners’ statutory argument that the

highway department failed to consider the economic effects

of the proposed location was rejected by the court, which

relied upon the certification of a state official that economic

effects had been considered and “ the presumption of regu

larity of public records and compliance by public officials

with duties imposed upon them by statute” (12a). Notwith

standing this holding, the court below in another portion

of its opinion quoted with approval the trial judge’s finding

that “ The proof shows that the consideration given to the

total impact of the link of 1-40 on the North Nashville com

munity was inadequate” (14a). As to the equal protection

claim, the Court said the record failed “ to show any intent

or purpose of racial discrimination” and rejected peti

tioners’ argument that they were not required to prove

discriminatory motive (12a).

Finally, the Court ruled that the District Judge had dis

cretion to deny relief considering the balance of the equi

ties (13a-14a).

Summary o f Facts

This lawsuit involves a proposed three mile long segment

of interstate highway route 1-40 located within the city of

Nashville, Tennessee.3 It is a small part of a thousand mile

system of interstate roads planned in Tennessee (Tr. 54-55),

and the forty-one thousand mile national interstate system

3 Route 1-40, when completed, will stretch from Greensboro, North

Carolina to Barstow, California. Rand-McNally Highway Atlas of the

United States, 43rd Ed. 1967, inside front cover. The court of appeals

states that the section in question is 3.6 miles long (4a). By so stating

the court probably included a section of the inner loop between a pro

posed interchange at 11th and 12th Avenues North and the Cumberland

River. Petitioners are not asking that the construction of this section—

which is not a part of 1-40— be enjoined. (See map, plaintiffs ex

hibit 31.)

8

planned under the Federal-Aid Highway program. The

disputed route is designed to connect the westbound leg

of the highway leading toward Memphis with an “ inner

loop” circling the center of Nashville and connecting other

interstate roads. The disputed segment also forms the

northern part of a designed outer half-loop road (Plf. Exh.

4). It cuts across the heart of the section called North Nash

ville, the principal Negro area of the City. Jefferson Street

is the axis of the Negro ghetto (Tr. 32-33,180, 262).

There are 234 Negro owned businesses in North Nash

ville, or more than 80% of the Negro owned and operated

businesses in the entire county (Tr. 32, 250), and most of

them are on Jefferson Street (Tr. 33, Plf. Exh. 8, p. 9).

These businesses have capital assets of about $4,680,000

and an annual gross volume of business averaging

$11,700,000 (Tr. 251). The undisputed evidence was that

virtually all these Negro businesses will either be destroyed

or seriously damaged by the proposed route and its ac

companying arterial roads which will take the property

occupied by many, and will disrupt those that remain by

fragmenting and restricting their service areas and sep

arating them from their customers (Tr. 33). Relocation will

be impossible for many of the businesses because there is

little other commercially zoned property in Negro areas

and racial discrimination will bar them from white areas

(Tr. 254-255). The testimony also showed that in other

areas of the City the interstate highway plans had been

designed to minimize or avoid damage to white-owned

businesses (Tr. 27-28).4

Three Negro institutions of higher learning, Fisk Uni

versity, Meliarry Medical College and Tennessee A&I State

4 In fact, petitioners’ expert witness, a city planner, testified that the

natural beneficiaries of the destruction of the Negro owned businesses will

be white owned establishments north of the proposed route (Tr. 34).

9

University, having substantial capital plants and large en

rollments (Tr. 202-03, 222-23, Plf. Exh. 28) will also be

damaged by the highway plans. The interstate route will

separate Tennessee A&I State University on the northwest

from Fisk and Meharry on the northeast, isolating Ten

nessee A&I in a narrow strip between 1-40 and the Cum

berland River, and isolating Fisk and Meharry between

1-40 and the industrial and downtown sector to the south

(Tr. 30-31). Major arterial routes planned in connection

with the interstate highway will further damage the insti

tutions by separating Fisk and Meharry, and channeling

heavy traffic through their campus areas (Plf. Exh. 26).5

The highway will also damage a new neighborhood health

center planned by Meharry Medical College by isolating

the population it serves (Tr. 224). Fifty-one Negro

churches in North Nashville would be detrimentally affected

by the 1-40 route: the property of two churches has been

taken for the route and two others have been notified that

their buildings will be taken (Tr. 232); the other 47 will be

separated from 20 to 75 percent of their memberships

(Tr. 234).

Whereas the effects of the highway program on Negro

institutions were not considered, the effects of the program

on white institutions were carefully appraised. As part of

a reevaluation of its interstate highway program in Nash

ville, including the major arterials serving the interstate

system, the state highway department undertook an exten

sive parking study of the City’s white University Center

(Vanderbilt University and Peabody and Scaritt Colleges)

(Plf. Exh. No. 7). Moreover, the state highway department

plans to coordinate its highway plans with several local

urban renewal projects, relocate a state highway, and re

6 The State Department of Highways and the Metropolitan Govern

ment jointly planned major arterial routes and their relationship to the

interstate highway program. (See plaintiffs exhibit No. 5.)

10

move all through traffic from the white University Center

area (Plf. Exh. No. 5, pp. 10-11). It is planning to do so

while planning at the same time to intensify traffic in the

Negro university area.

Both courts below agreed that the damage to the Negro

institutions of North Nashville had been amply demon

strated. The Court of Appeals wrote that:

. . . the District Judge found that “ [p]laintiffs have

shown that the proposed route will have an adverse

effect on the business life and educational institutions

of the North Nashville community. The proof shows

that the consideration given to the total impact of the

link of 1-40 on the North Nashville community was

inadequate.” He pointed out that the business section

of Jefferson Street will be “gravely affected.” This

Court agrees with these conclusions. For example, it

is shown that the blocking of other streets will result

in a heavy increase in traffic through the campus of

Fisk University and on the street between this univer

sity and Meharry Medical College. A public park used

predominantly by Negroes will be destroyed. Many

business establishments owned by Negroes will have to

be relocated or closed (14a).

There was also substantial evidence to support the trial

court finding (quoted above) that there was “ inadequate”

consideration of the adverse effect of the route on the com

munity. Boute 1-40 was planned as a part of the interstate

system of highways begun under the Federal-Aid Highway

Act of 1956 (70 Stat. 385, Tit. 23 U.S.C. §§101 et seq.).

Even before the 1956 law was passed, but in anticipation

of it (Tr. 371), planning of the interstate roads within

Nashville was begun by a city-county planning agency,

which commissioned the engineering firm of Clarke and

11

Rapuano to undertake a study and propose routes (Plain

tiffs Exhibits 35, 36). Except for the link now in question,

the routes finally adopted, including the basic inner and

outer loop plans, were substantially the same as those rec

ommended in 1955 by Clarke and Rapuano (Compare

Plaintiffs Exhibit 31 with Exhibits 35 and 36). But the

Clarke and Rapuano recommendations for the road seg

ment which would serve the function of the presently dis

puted segment were quite different from the plan subse

quently adopted. Clarke and Rapuano’s Memphis leg would

have continued on a straight line following the shortest

distance to the to the center of the city until it joined the

inner loop (Plaintiffs Exhibit Nos. 35 and 36). This route

would have produced none of the adverse effects on the

North Nashville Negro community. It would not have

affected the Negro businesses or the educational institutions

in the manner of the present proposed route. The consult

ing engineer’s report recommending the route stated that

it was based on many factors, including a consideration of

“ the density of population” , the “ land use pattern” , and

“ existing neigborhoods” (Plaintiffs Ex. Nos. 35 and 36).

Shortly thereafter the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act placed

initial responsibility for determining interstate system

highway routes in the hands of state highway departments

(23 U.S.C. §106). The Tennessee highway department ap

proved the present route plan in 1957, after consultations

with the Nashville planning agency, federal officials, and

the Clarke and Rapuano firm which was also hired by the

state highway department in a consulting role. It has

never been explained why the original Clarke and Rapuano

route for the Memphis leg connecting with the inner loop

was abandoned. In place of the straight line into the center

of the city originally proposed, there was substituted the

present route which veers off into the Negro community.

12

At the trial in this case, a high state highway official

at first denied knowledge of the existence of the original

Clarke and Rapuano route (Tr. 372-373), and admitted it

only when confronted with the maps and minutes of three

meetings he attended to discuss the route.6 No state official

offered any explanation for abandoning the original route

and substituting the new route. Petitioners’ expert witness

(Mr. Yale Rabin, a city planner) examined the files of the

Metropolitan planning agency (which participated in all

stages of the planning of the highway) and found no docu

ments explaining the change (Tr. 486). Despite persistent

questioning, Mr. Leon Cantrell, the highway location engi

neer, never really said why the route was changed to go

through the Negro community. First he said that the rea

sons for the change would “ take me a week to tell you”

(Tr. 385). When pressed for specifics he said that “all of

our studies pointed to the fact that it was the most sound

thing that we could do towards making the improvement

through the city” (Tr. 388). He finally said that he meant

studies by the Planning and Research Department (Tr.

388-389). Counsel persisted and questioned the State High

way Department’s planning and research director, Mr.

Clarence Harmon, about the existence of such studies. Mr.

Harmon admitted that his files contained no such studies

about the economic impact of the present route on the

North Nashville community. Mr. Harmon testified as

follows:

Q. Yes. Is there any information in your files at

all with regard to the—any economic studies made

by the State Department of Highways, State Highway

Department, with regard to the North Nashville area!

A. Not that I can recall at this time, Mr. Williams

(Tr. 466-467).

6 Plaintiffs exhibit No. 34 is a record of records on July 11, July 12

and July 13, 1955.

13

At one point in his testimony, Mr. Harmon indicated

such studies might exist, but he quickly retracted that

testimony when asked to produce the volumes:

Q. Will you bring them down after lunch and could

you at lunchtime pinpoint the data which show—

which shows the economic impact— A. (Interposing)

No. There is none that shows economic impact.

Q. All right, sir. Then, there is no data that reflects

the economic impact of the location of this highway

on the Negro community in North Nashville, is there?

A. No, sir. That’s right. There isn’t (Tr. 471).

The Tennessee State Highway Department held a public

hearing on the proposed interstate system for Nashville

at 9:30 a.m. on May 15, 1957 (Plaintiffs’ Ex. No. 1). There

have been no public hearings on these roads in the suc

ceeding ten years. The court below held that the notice

of the hearing, by posting in several post offices and

delivering copies to the Mayor and County Judge was

“unsatisfactory . . . especially when for some unexplained

reason the notice announced the hearing for May 14, and

it actually was held the following day, on May 15” (10a).

There were no notices at all posted in the Negro sections of

town (9a). The largest local newspaper carried no mention

of the hearing and three reporters (one of whom is now city

editor of the Nashville Tennessean) who covered the high

way story at the time and wrote numerous articles about

the highway testified that they did not know or write

anything about the hearing (Tr. 128, 137, 143). The hear

ing was recorded by a tape recorder and later transcribed.

The court below said that the hearing manuscript:

. . . leaves much to be desired as a manuscript of

a public hearing, since the recording device failed

to pick up many questions from the audience. The

manuscript contains only the statements and answers

14

of the Commissioner and other representatives of

the highway department and what was said from the

platform where the microphones were located (10a).

There was no discussion during the hearing of the impact

of the road on the North Nashville community. Since the

transcript contains no names of private citizens who asked

questions, none could be called as witnesses to explain

what occurred at the hearing, or what did not occur. The

District Court “ assumed” that petitioners had made out a

prima facie case of lack of proper notice as the colloquy

quoted in the margin indicates.7

Two days after the hearing, on May 17,1957, an attorney

for the highway department signed a certificate which he

attached to the hearing transcript stating that he had read

the transcript, and that the highway department had con

sidered the economic effects of the location of the project

and was of the opinion the project was properly located.

Subsequently, in 1958, federal officials approved the plan

and authorized the expenditure of federal funds to acquire

land in the area now in question (Tr. 418). However, not

until 1965 and 1966 did the state highway department move

to acquire land in the area (Tr. 419, 421), and not until

1967 did the board take the final steps leading toward

awarding a construction contract (Tr. 438).

7 Mr. Williams: Well, Your Honor, if Your Honor pleases, I have a

whole lot more. I have some additional witnesses on this question of

notice.

The Court: Well, I ’m not interested in any further ones on the ques

tion of notice. I tell you quite frankly, Mr. Williams, as far as I can

tell about the law on this notice thing that that raises a question between

the Federal Government and State as to paying the money. That seems to

be the way the cases have been decided and have nothing to do with any

thing further.

So, let’s just assume that you have established by certain proof subject

to their coming in if they want to offer something else, you have made

out a prima facie case on that for whatever value it may have (Tr. 145).

15

Throughout the decade from 1957 to 1967 Negro citizens

of North Nashville from time to time protested the plan

to various officials. (Tr. 118-119, 151-158, 180, 258, 265,

267-268, 286-287, 315-316). From 1957 to 1967 every pro

test and every inquiry was met with official statements by

city as well as highway department officers that the high

way plans were “ preliminary,” were “not final,” and were

“ subject to change,” and that the exact location of the road

was still uncertain. At least seven plaintiffs’ "witnesses

testified to such responses to their inquiries; the seven

included two Negro councilmen representing the affected

areas (Harold Love and John Driver) (Tr. 112-113, 118,

294-295), three civic organization leaders (Mrs. Blackman,

Mrs. Caruthers and Mrs. Fuson) (Tr. 169, 184-185, 312),

a businessman (Mr. Otey) (Tr. 258, 285), and a Fisk Uni

versity faculty member (Mr. Vaughn) (Tr. 306-307). None

of them were able to discover the precise route of 1-40

through North Nashville, although among them they talked

with and heard speeches by officials in both the city and

state agencies involved in the highway planning.

Mr. Leon Cantrell, an engineer for the Tennessee high

way department for more than 45 years, described the route

selection process. He said that first the engineer estab

lishes “a corridor through which to make some studies”

(Tr. 390). Then a “preliminary location or preliminary

line is projected. That doesn’t necessarily mean that is

where it is going to be” (Tr. 391). Eventually the line is

finalized. He said, “You don’t get the line tied down until

just about the time it is ready to let the contract. I f you

tie it down more quickly than that, you will be ill-advised”

(Tr. 391). Cantrell said that the 1957 plans were corridor

locations (including, specifically, the maps published in

newspapers at that time (Tr. 396-397)) and that a “ corridor

could be from five hundred feet to a mile wide” (Tr. 372-

1 6

373), although normally in an urban area it would be

“within several blocks” (Tr. 398).

The highway department’s right of way acquisition en

gineer, J. K. Bilbrey, testified that the state got authority

to acquire real estate along the route from 35th Avenue

to 18th Avenue on July 15, 1958 (Tr. 419). But acquisition

of the bulk of the parcels did not begin until October 15,

1965 (Tr. 420). Similarly, with respect to the segment

from 18th Avenue to the Cumberland River, acquisition was

authorized in September 1958, but except for a few parcels

acquisition did not begin until May 13, 1966 (Tr. 420-

421).

Mr. Bilbrey testified that in an area from 48th Avenue

to the River (an area larger than, but including the dis

puted segment) all but 90 of 1,100 parcels had been acquired

by the State, at an overall cost between nine and ten million

dollars (Tr. 412-413). Many of the business properties

along Jefferson Street still stand and are in operation

although some demolition work has begun (Tr. 426). Some

residential property already acquired by the City is also

still occupied (for example, see. Tr. 193).

This lawsuit was filed October 26,1967, when the highway

department announced imminent plans to let a construction

contract for the road segment. The plaintiffs had been un

successful in efforts to persuade the federal and local

authorities to postpone letting contracts for a 90 day period

of further study and negotiation (Tr. 155-158). They were

unable to get such a delay notwithstanding a unanimous

resolution of the Nashville and Davidson County Metro

politan Council supporting their request (Tr. 296, Plaintiffs

Ex. 33).

17

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Introduction.

The crisis of the cities is compounded of many elements.

This case is of great importance for it affords the oppor

tunity of applying the rule of law and the Constitution

to some of them. In particular, the case involves the

impact which the vast federal highway program has had

on urban areas and legal rules which would regulate that

program’s impact on minority communities.

Homer Bigart of the New York Times recently has

written that the federal road building program has com

pounded the “misery of the dispossessed:”

The program has sent great rivers of concrete

creeping like lava through residential neighborhoods

and commercial areas, dislocating families, schools,

churches and businesses. Parks have been torn up,

historic sites engulfed. Because the slums afford the

easiest and cheapest corridors, it was the ghetto fam

ilies that were most often uprooted.

Whenever the slums were black, the misery of the

dispossessed was compounded. Imprisoned in the core

city by de facto housing segregation, the dispos

sessed Negroes were usually unable to obtain other

dwellings except at much higher rent. This was a

contributing factor to the racial tensions that ex

ploded in last summer’s riots. (New York Times, No

18

vember 13, 1967, Late City Edition, page 1, “U. S.

Road Plans Periled by Rising Urban Hostility.” )8

It is estimated that 146,950 households will be displaced

by federally aided highway construction in the three year

period from July 1, 1967, to June 30, 1970. Similarly,

16,679 businesses and non-profit organizations will be dis

placed. The vast majority are in urban centers.9 A Senate

committee began hearings to consider the problem of urban

highway location on November 14, 1967. (Senate Subcom

mittee on Public Roads, Hearings to Review Policies Re

lating to Urban Highway Planning Design and Location).

Professor Charles A. Reich has written vividly about

suburban housewives, elderly widows, men in business suits

and off-duty policemen attempting to bar the way of bull

dozers about to wreck historic homes and cut down age

old trees to push interstate highways forward. Reich,

The Law of the Planned Society, 75 Y a l e L. J. 1227 (1966).

Professor Reich observes that:

. . . it seems increasingly difficult for the citizen

to make effective contact with government. Citizens

are rarely informed when the agency makes its deci

sion ; their first notice is often the roar of a bulldozer.

8 More recently, the same newspaper reported:

. . . in a surprisingly large number of other American cities

[i.e., other than Washington, D. C.]— New York, Philadelphia, Balti

more, Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, New Orleans, Nashville, San

Francisco and Seattle— the angry cries of similar neighborhood

groups have helped bring the bulldozers to a halt or diverted them.

As a result, a vast re-thinking of highway concepts is underway at

top government levels. (New York Times, December 31, 1967, page

E-7, “White Roads Through Black Bedrooms.” )

9 House Committee on Public Works, 90th Cong., 1st Sess., Highway

Relocation Assistance Study (transmitted by Secretary of Transportation

to Congress) (Comm. Print No. 9, July 1967).

19

Even when notice is available many agencies have no

regular procedures for hearing citizens’ protests. Nor

are agencies easily controlled through elections; . . . .

Nor does there appear to be much hope of relief

from the law and the courts. . . . the courts almost

uniformly refuse to interfere. Lawyers who practice

before government agencies and students of admin

istrative law are often as baffled as local demonstrators

(id. at 1229).

Rules of law exist— as this petition demonstrates—to deal

with these issues reguarly and according to standards.

This petition asks that those rules be applied. In the in

stant case, both courts below went to unusual lengths to

express a sense of agreement with petitioners’ position.

Judge Gray expressed grave doubts about the “wisdom of

the selection” of the 1-40 route (3a). The Court of Appeals

“ regretted” that petitioners’ requests for delay and more

study were not granted (14a) and speculated that “ there

yet may be hope that some of the severe damage to the

Negro community and institutions can be reduced if not

relieved in their entirety” in view of reported statements

of federal officials about conducting further studies (15a).

But both courts deferred to the wisdom of the highway

engineers— (“ The routing of highways is the prerogative

of the executive department of government, not the judi

ciary” (12a; emphasis added)— and denied relief. Funda

mentally, the courts below did not acknowledge the func

tion of law and the Constitution as relevant to petitioners’

problem. With respect, the root fallacy of the lower

courts’ view of this case is encapsulated in the quoted

sentence. All powers of every department of government,

whether concerning highways or anything else, must be

exercised in conformity with the Constitution and laws.

2 0

The word “prerogative,” with its unfortunate history, can

not carve out an exception.

Petitioners submit that the courts of the United States

have a role defined by law in such controversies, where,

as here, state officials have, by any reasonable appraisal,

plainly engaged in racial discrimination in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment and have failed to conform to re

quirements laid down by the Congress for the protection of

citizens in petitioners’ situation.

This case should be reviewed despite its non-final status

because there are “ important and clear cut issue [s] of law

fundamental to the further conduct of the case . . . [which]

would otherwise qualify as a basis for certiorari.” Stern

and Gressman, Supreme Court Practice, 3rd Ed., pp. 148-

149, citing United States v. General Motors Corp., 323

U.S. 373, 377; Land v. Dollar, 330 U.S. 731, 734, n. 2;

Larson v. Domestic <& Foreign Commerce Corp., 337 U.S.

682, 685, n. 3. Any appraisal of the exercise by the Dis

trict Court of its equitable discretion must take into ac

count the lower court’s erroneous view of the law. It is

by no means clear that the trial court would have exercised

“discretion” to deny all relief if the court had understood

the law and the Constitution to be as petitioners urge. In

any event, the trial court had no “ discretion” to refuse to

redress a plain violation of the Constitution.

I f review here is denied, the damage which petitioners

seek to avoid will in all likelihood be completed before

litigation on an application for final injunction is concluded.

21

n.

The Highway Route Is Racially Discriminatory in

Violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

If respondents had expressly provided that this span of

1-40 “be so located as to injure as much Negro business

and other property, and as little white property as possi

ble,” no court would hesitate to strike it down. Petitioners’

proof, accepted by both courts below, showed a close ap

proximation, in effect, to the route that would have been

followed had the quoted directive been in force. The courts

below erred by applying an erroneous requirement that

petitioners, in addition to this practical equivalence, prove

a racially discriminatory “motive” or “ intent” where they

plainly established the racially discriminatory effect of the

highway routing. They proved, and the courts below ac

knowledged that they proved, that the highway link sub

stantially harmed Negroes. It is uncontradicted that the

interstate highway plan visits no such harm on white com

munities, businesses, churches and educational complexes.

There was uncontradicted evidence of affirmative efforts

made by the highway planners to avoid such damage to

whites. Moreover, a practical alternative route portending

no harmful effects for Negroes was available, was first

recommended by engineering consultants, and was cast

aside for no recorded or explained reason. None of the

state highway planners offered any reason to justify the

route chosen, or any explanation for the decision to visit

such incalculable harm on the Negro community. Can such

an overwhelming case of racial discrimination escape con

demnation because the state officials have not confessed a

racial motivation?

No such proof of motivation has been found necessary in

several classic cases of racial discrimination in this Court,

22

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356; Guinn v. United States,

238 U.S. 347; and Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339.

Yick Wo, who had a wooden laundry building, was con

victed under a law forbidding the operation of laundries

without official permission, except in brick or stone build

ings. In the city there were 320 laundries, 310 of them

were wooden, and 240 were operated by Chinese persons.

Yick Wo and 200 of his Chinese countrymen were denied

permission to maintain laundries. He and 150 Chinese

persons were arrested under the law and the 80 laundry

operators who were not Chinese were left unmolested. The

discrimination was condemned because there was “practi

cally . . . unjust and illegal discrimination between persons

in similar circumstances” (118 U.S. at 374). The effect was

to discriminate against Chinese laundry operators, and that

was enough without proof of hostile motivation.

Similarly, the discriminatory effect of the “grandfather

clause” condemned in the Guinn case, supra, was sufficient

to settle the matter. The government did not prove the

motive of the legislators; it won by showing that the prac

tical effect of the laws was to prevent Negroes from voting.

And in Gomillion v. Lightfoot, supra, where the interest of

Negroes was unmistakably attacked without their ever be

ing named, the Court found the conclusion of discrimina

tion irresistible from factual allegations simply describing

the effect of the challenged law on Negroes, e.g., excluding

them all, and not excluding whites, from Tuskegee.

We believe the discrimination showing in the instant case

is as plain as in Yick Wo, Guinn and Gomillion.

It is plain that Negroes have been treated in a manner

extremely detrimental to their interests, that the burden

falls upon them unequally, and that no justification for the

imposition appears. Whether the cause is arbitrariness, in

23

difference or deliberate hostility, the result of unequal treat

ment is constitutionally prohibited, as “ it is of no consola

tion to an individual denied the equal protection of the laws

that it was done in good faith.” Burton v. Wilmington

Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 725.

in.

There Was no Public Hearing With Proper Notice

as Required by the Federal Highway Statute.

The Tennessee Highway Department failed to comply

with the requirement established by the Congress in §116 (c)

of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 that a state

highway department submitting a plan for a federal-aid

highway project certify “ that it has had public hearings,

or has afforded opportunity for such hearings, and has

considered the economic effects of such a location.” Peti

tioners contended that the highway department failed to

give any adequate notice of the hearing held on May 15,

1957. The district judge stated during the trial that he

assumed petitioners had made a prima facie case on the

notice question (see note 7, supra). The Court of Appeals

expressly held that the Tennessee Highway Department

used “an unsatisfactory way to give notice of a public

hearing” (Appendix 10a).10

Both courts below rejected petitioners’ arguments based

on the hearing requirement but did so on different rea

soning. Accordingly, we discuss first the District Court

reasoning and then that of the Court of Appeals.

10 Compare the scanty notice in the present ease with the elaborate ef

forts by another state highway department to give notice which are re

ported in Linnecke v. Department of Highways, 76 Nev. 26, 348 P.2d 235,

236-237 (1960) (notice by publication in newspaper, by extensive press

coverage and by distribution of 30,000 pamphlets describing the freeway

to utility users).

24

District Judge Gray stated in his oral findings and

conclusions that:

The court finds as a matter of fact that a hearing

was held and holds that the questions of insufficiency

of notice, inadequacy of the hearing, and of the tran

script thereof are questions addressing themselves to

the Bureau of Public Roads of the Department of

Transportation (la ) .11

But there is no warrant for the refusal of the court to

implement the Congressional policy expressed in §116(c).

The court’s reasoning is bottomed on the absence of a

state law requirement of a hearing and thus defeats the

Congressional policy. The plain purpose of the Congress

in enacting the public hearing requirement was to provide

an opportunity for citizens and communities affected by

the roads to have a voice before highway plans were

presented by the States to the federal authorities for ap

proval. This is the common sense interpretation of §116(c)

and it is adequately supported by the legislative history.

Section 116(c) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956,

70 Stat. 385, was enacted to broaden a pre-existing require- 11

11 Judge Gray cited and relied on three lower court decisions which had

expressed the view that citizens could not complain about the failure of

highway officials to afford a hearing. Hoffman v. Stevens, 177 F. Supp.

898, 903 (M.D. Pa. 1959); Piekarski v. Smith, 38 Del. Ch. 402, 147 A.2d

176 (1958), aff’d 153 A.2d 587 (Sup. Ct. Del. 1959); Linnecke v. Depart

ment of Highways, 76 Nev. 26, 348 P.2d 235 (1960). These courts rea

soned that since state authorities under state law could condemn land for

highways without conducting public hearings, a failure to comply with

the federal statutory requirement of a public hearing was a matter which

could be corrected only by the federal administrative officials withholding

federal funding. The line of reasoning is exemplified by Hoffman v.

Stevens where the court said: “Under Pennsylvania law and policy, ab

sent federal aid, such hearings are not required or held. A t best, failure

to afford a hearing might give rise to a dispute between the Secretary of

Commerce and the Pennsylvania Department of Highways as to the alloca

tion and use of federal funds” (177 F. Supp. at 903).

25

ment which had been enacted in a 1950 highway act.1!

The legislative history of the 1950 provision requiring

public hearings (§13 Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1950,

64 Stat. 791)12 13 plainly demonstrates a purpose to insure

“ that the residents of the cities or towns are given the

opportunity to express their views” on highway locations

(S. Rep. No. 2044, 81st Cong., 2nd Sess., 8 (1950)). The

debate on an amendment to delete the hearing provision

in the Senate shows that the proponents of the bill wanted

local citizens to have an opportunity to be heard in protest

against the decisions of highway engineers. 96 Cong. Rec.

13005-13006 (1950), remarks of Senators Saltonstall,

Chavez and Kerr.14

12 The Conference Committee Report on the 1956 act stated that “this

provision continues and broadens the existing requirements in § 13 of

the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1950” (H.R. Rep. No. 2436, 84th Cong.,

2nd Sess., 36 (1956).

13 “Any State highway department which submits plans for a Federal-

aid highway project involving the bypassing of any city or town shall

certify to the Commissioner of Public Roads that it has had public hear

ings and considered the economic effects of such location.”

14 The debate included the following exchange:

Mr. K err: Is the effect of the language in the bill that the State

highway department shall certify that they have given the folks

affected an opportunity to have a hearing?

Mr. Chavez: That is all that is asked. At least let them have

a day in court.

Mr. Kerr: Does that interfere with States’ rights?

Mr. Chavez: It gives States’ rights.

Mr. Kerr: Does it interfere with local rights?

Mr. Chavez: It gives the local citizens rights.

Mr. Kerr: Is the local right it gives them the right to be heard?

Mr. Chavez: Yes; the right to be heard.

Mr. Saltonstall: Mr. President, will the Senator from New

Mexico yield?

Mr. Chavez: I yield.

Mr. Saltonstall: Let us assume that a State highway depart

ment has a certain fund of its own for use in its own bailiwick

with regard to the location of a road. Would not the intrusion of

26

The hearing is supposed to give the citizen an opportunity

to communicate with state and federal planners.15 16 As the

Bureau of Public Roads Policy and Procedure Memorandum

20-8 (Def. Exh. 2, para. 3-h) makes clear, the transcript of

the public hearings are sent to the federal officials so that

they may be satisfied that the State has considered the

economic effects of the roads.16 Petitioners were deprived

of an opportunity to communicate their views to either the

state or federal officials at the time the important decisions

the Federal Government be in effect an interference with the

State’s rights?

Mr. Chavez: N o; we insist that the local people have a right to

he heard.

Mr. Kerr: The only thing that is required is that the officials

certify that that have given the people a chance to be heard, is it

not?

Mr. Chavez: W e do not even ask that they agree with them,

but they should be heard. Now they say, “W e are going to change

this highway,” and the folks of the community have nothing to say

about it. (96 Cong. Rec. 13006 (1950); emphasis added.)

15 Increasingly, Congress and the Executive Branch provide for com

munity participation in a variety of federal programs primarily affect

ing cities. See The United States Housing Act of 1949, 63 Stat. 416, 42

U.S.C. $ 1455(c) (Public hearing before urban renewal). Regulations

provide further protections for minority groups. U.S. Department of

Housing and Urban Development, Urban Renewal Manual, § 10-1. See

also, The Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of

1966, 80 Stat. 1255, 42 U.S.C. $ 3301 et seq.

16 An amendment to Policy and Procedure Memorandum 20-8 issued

June 16, 1959, contains a more complete statement of the purpose of

public hearings:

The objective of the public hearings is to provide an assured

method whereby the State can furnish to the public information

concerning the State’s highway construction proposals, and to af

ford every interested resident of the area an opportunity to be

heard on any proposed Federal-aid project for which a public

hearing is to be held. At the same time the hearings afford the

State an additional opportunity to receive information from local

sources which would be of value to the State in making its final

decision as to which of possibly several feasible detailed locations

should be selected. (P.P.M. 20-8(1))

27

were made by the failure to hold a hearing with proper

notice. In addition, the hearing was held many years before

there was any actual move to construct the highway and

the public had no reasonable way of keeping informed of

the decision processes between the governmental agencies

during the ten year period, 1957-1967. Thus, in this addi

tional respect, the State Highway Department failed to

hold a hearing affording a meaningful way for citizens to

communicate their views to the decision makers.

The opinion of the Sixth Circuit states an additional

ground for denying relief on the hearing question. This is

that:

. . . Although the notices were unsatisfactory, we are

convinced that the District Judge would have been

justified in concluding that no literate citizen of the

Nashville community could have been unaware since

1957 of the proposed route of the interstate highway,

including the approximate location of the section now

under attack.

The court pointed to newspaper clippings, maps, public

speeches and publicity about the proposed routes and the

fact that some of the appellants knew the general area of

the proposed route. We urge with deference that this treat

ment entirely misses the point. If there is a federal statu

tory requirement that citizens be given an opportunity to

express their views in a public hearing, newspaper publicity

about the proposed routes is no substitute for a hearing.

Of course, newspaper publicity giving notice of the hearing

would be a different matter, but there was none. It may be

relevant with respect to other issues involved in the case

(see part V infra) that the petitioners had an opportunity

to know about the proposed routes from newspaper arti

cles, but this cannot at all affect their right to have had a

proper public hearing.

28

The respondents have argued that petitioners have no

standing to object even if the highway department com

pletely flouted the hearing requirement of §116 (c). We

submit that the Court of Appeals properly rejected this

claim citing Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v.

Federal Power Commission, 354 F.2d 608 (2nd Cir. 1965),

where conservationists were allowed standing to contest

orders of the Federal Power Commission although they as

serted no economic interest. See Office of Communication of

United Church of Christ v. F.C.C., 359 F.2d 994 (D.C. Cir.

1966). And, of course, petitioners do have a demonstrable

economic interest in view of the threatened destruction of

businesses and harm to their universities. See also, Road

Review League v. Boyd, 270 F. Supp. 650, 660-661 (S.D.

N.Y. 1967).

IV.

There Was no Consideration of the Economic Effects

of the Highway Route as Required by Federal Law.

Petitioners have contended in Part II, supra, that the

Fourteenth Amendment makes unlawful the decision taken

when the highway was routed so as to destroy or deeply

to injure the Negro community of Nashville, as such, for

the benefit of the remaining—that is to say, the white—

segment. Petitioners contend here that, at a minimum,

the Fourteenth Amendment requires that such an action

not be taken without adequate consideration of its effects.

“Equal protection of the laws” , a concept applicable with

special force in the field of race (see, e.g., Mr. Justice

Harlan dissenting in Harper v. State Board of Elections,

383 U.S. 663, 682, n. 3), ought to require at the least that

protection which comes from fair and enlightened delib

29

eration. No less, it would seem, ought to be held required

by the due process clause, occurring as it does in an amend

ment which, again, specifically thrusts in the direction of

racial discrimination and injury. The lower courts have

found and the record amply shows that such deliberation

was, if not entirely lacking, present in such minimal amount

as to be “ inadequate.” “ Inadequate” consideration of the

claim of a Negro community not to be wiped out is doubly

“ inadequate” to the Fourteenth Amendment.

Closely connected is the failure of the respondents to

follow the sense of the statutory requirement that it be

certified that consideration has been given to the economic

effects of highway routing. In the context of the present

case this requirement ought to be held to compel considera

tion of racially discriminatory economic effects.

The Tennessee Highway Department failed to comply

with the requirement of Section 116(c), supra, that the

Department certify that it “has considered the economic

effects of such a location” of a road. The trial judge found

that the consideration of the economic effects of the route

on the North Nashville community was “ inadequate,” and

the Court of Appeals opinion quotes this finding and ex

pressly states agreement with it (14a). But on this issue

also the courts denied relief.

The trial court made no detailed findings on this question

because it saw it as relating to the wisdom of the route,

which the court said it was powerless to review. The Court

of Appeals’ opinion partly reflects this same view, express

ing the necessity for judicial deference to “ executive pre

rogative” as if it were a sovereign prerogative. Under

§116(c) the courts below should have inquired whether the

State Highway Department gave careful consideration to

the economic effects of their plan as Congress commanded.

In Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference v. Federal Pow

30

er Commission, 354 F.2d 608 (2nd Cir. 1965), cert. den. 384

U.S. 941, the Court reviewed Commission action approv

ing a proposal to build a power facility notwithstanding

conservationists’ objections. The landmark decision re

turned the case to the Commission for a new hearing saying

that the record on which the Commission decided the issue

was incomplete, that the Commission ignored relevant fac

tors and failed to make a thorough study of possible alter

natives. The Court said, “While the courts have no

authority to concern themselves with the policies of the

Commission, it is their duty to see to it that the Commis

sion’s decisions receive that careful consideration which

the statute contemplates” (354 F.2d at 612). Analogous

reasoning should govern the instant case. The requirement

of section 116(c) cannot reasonably be deemed satisfied by

“ inadequate consideration” of the economic effects of a

road as was found in this case. The Congressional scheme

for the roads program is subverted rather than supported

by the failure of the courts to inquire whether the state

highway departments are carefully considering the eco

nomic effects of highway routes. This is an important

policy of the Congress expressed in the very section of the

basic law containing the declarations of Congressional in

terest about accelerating the interstate highway system

and speeding its completion17 and also a Congressional

policy of encouraging and developing small businesses.18

The decision below defers to the engineers. Congress was

concerned with protecting the citizens from some of the

highway engineers. Opposing a move to delete the public

hearing requirement from the highway law, Senator Chavez

said:

17 See Sections 116(a) and 116(b) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act

of 1956, 70 Stat. 385.

18 Section 116(d) of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956, 70 Stat.

386, now codified as 23 U.S.C. 5 304.

31

Little towns and villages are being ruined because

every 2 or 3 years an engineer lias an idea that the

automobiles going to the next town should be able to

reach it 5 minutes sooner. We should consider the

economy of the folks living along the highway. (96

Cong. Rec. 13006 (1950)).

Several relevant recent Congressional enactments demon

strate the view of Congress—consonant with the Scenic

Hudson decision—that highway planners must consider

alternative plans so as to minimize the harm inflicted upon

the variety of interests affected by highway construction.

Such provisions were contained in Section 15 of the Fed

eral-Aid Highway Act of 1966, 80 Stat. 766, 771, 23 U.S.C.

§138 (Preservation of parklands), and in the Department

of Transportation Act, sections 2(a) and 4 ( f ) ; 80 Stat.

931. 934, 49 U.S.C. §§1651(a), 1653(f). The last mentioned

provision states:

(f) . . . After the effective date of this Act, the Secretary

shall not approve any program or project which re

quires the use of any land from a public park, recrea

tion area, wildlife and waterfowl refuge, or historic

site unless (1) there is no feasible and prudent alter

native to the use of such land, and (2) such program

includes all possible planning to minimize harm to

such park, recreational area, wildlife and waterfowl

refuge, or historic site resulting from such use.

Indeed, two significant state court decisions recognize

the necessity of judicial scrutiny over plainly arbitrary

actions which disregard alternative methods of minimiz

ing harm. In State Highway Commission v. Danielsen, 146

Mont. 539, 409 P.2d 443 (1965), a planned highway route

was enjoined. In Texas East Trans. Cory. v. Wildlife Pre

serves, Inc., 48 N.J. 261, 225 A.2d 130 (1966), a case in

32

volving an underground gas transmission pipeline, the

court held:

Existence of an alternate route for a pipeline which

will reasonably serve the utility’s purpose, and which

if utilized will avoid visiting on the condemnee’s land

the significantly disproportionate damage which the

originally intended route would cause, is a matter

which rationally relates to the issue of arbitrariness.

. . . That a court has no authority to command the

alternative does not mean that it cannot reject the orig

inal proposal. 235 A.2d at 137.19

Implicit in the §116(c) requirement that the economic

effects of highway location be considered is the require

ment that state highway departments act non-arbitrarily

and consider alternatives to routes which will cause dis

proportionate harm to portions of communities affected by

highway planning.

The Court of Appeals opinion seeks to avoid these argu

ments by pointing out that the Commissioner of Highways

announced that the purpose of the public hearing held

May 15, 1957, was to hear statements concerning the eco

nomic effects of the route, and that the attorney for the

department signed a certificate that the department had

considered the economic effects. The court said that the

District Court had no practical way of determining to what

extent the highway offiials considered the economic effects,

and that it was proper to rely on a presumption of regular

ity of the public records—the certificate—and of compliance

by public officers with their statutory duties.

This view might be reasonable if the record was merely

silent on whether the economic effects were considered.

19 See also. City of Pittsburgh v. F.P.C., 237 F.2d 791 (D.C. Cir.

1956).

33

But this record establishes the negative proposition. It

shows, by testimony out of the mouths of the respondents,

that the economic effects were not considered. The Director

of Research and Planning for the Highway Department

testified that no studies appraising the economic effects of

the route through the North Nashville community existed

in the files of the department (Tr. 466-467, 471). To be

sure, the former commissioner did, as the opinion below

says, point to exhaustive studies of the highway proposals

by a reputable firm. But these Clarke and Rapuano studies

(Plf. Exhs. 35, 36) recommended a route which did not

pass through the Negro neighborhood and would have had

none of the disastrous effects on the Negro community that

the route finally approved will have. Thus, the commis

sioner said that he relied on his expert engineers to locate

the route; the location engineer Cantrell said he relied on

the Department of Research and Planning; the head of that

department said there were no studies in the files; and the

outside consulting firm’s report reflecting a conservation of

community values, recommended an alternate route not

passing through the Negro ghetto. Additionally, the 1957

public hearing transcript (Plf. Exh. 1) contains not the

slightest mention of the impact of the route on the North

Nashville business districts, churches, or universities. Thus,

the presumption that the certificate was true and of com

pliance by officials with their statutory duties was plainly

rebutted by the officials and their records.20

20 Professor Wigmore says that the presumption of due performance

of official duty “is more often mentioned than enforced; and its scope as

a real presumption is indefinite and hardly capable of reduction to rules”

(9 Wigmore on Evidence, 3d Ed., 4 2534, p. 488). Wigmore also rejects

the notion that a certificate could be deemed conclusive as against testi

mony on oath. “In many other instances the suggestion has been made

that an official certificate should be taken as a conclusive testimony to

the facts certified but this suggestion has been almost invariably repudiated

by the courts” (4 Wigmore on Evidence, 3d Ed., § 1352, p. 708).

34

"We pray that the Court grant review to redress a severe

wrong to petitioners, to implement a plain Congressional

policy, and to guide the lower courts in finding their proper

role with respect to one important aspect of the crisis21

situation facing urban Americans.

y .

The Balance of Equities Favors Petitioners.

In this concluding section we discuss briefly several

“ equity issues” which might be regarded as relevant to

a decision of the case. None of these “equity issues” were

very clearly relied upon by the trial court as a ground of

decision. However, some have been raised by the respon

dents and others were mentioned by the Court of Appeals.

First, the respondents have raised the defense of laches.

They rely upon the fact that during the past two years

the State has acquired title to all but a few of the parcels

of land along the projected route of the highway. The

District Court opinion did not really decide whether,

under all the circumstances, petitioners had exercised

reasonable diligence in bringing their case to court. The

court stated merely that:

Their failure to initiate a substantial protest against

the route of this highway until very recently can not

be explained except by the assumption that the impact

of the location was not realized until that time.

This somewhat unclear finding is entirely consistent with

petitioners’ testimony that they were unable to learn until

recently the precise location of the road and that their

21 Congress has found and declared “that improving the quality of

urban life is the most critical domestic problem facing the United States.”

Section 101 of the Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development

Act of 1966, 80 Stat. 1255, 42 U.S.C. §3301 et seq.

35

many inquiries produced only vague and indefinite ex

planations of the governmental plans along with continu

ing disarming reassurances that plans were not yet final.

The highway location engineer testified that the route was

a “corridor plan” and then a “preliminary plan” until

very recently since it was not the practice to finalize high

way plans until just before construction contracts are

awarded. There is no evidence that petitioners had any

notice of what was going on during the multi-stage proc

esses by which the highway department moved to begin

the highway over the period of a decade following the

public hearing.

Petitioners did bring suit before the highway depart

ment obligated itself by contract to construct the road.

Thus, no third party’s contract rights are at stake. There

is no evidence that petitioners were able to determine the

harmful consequences of the proposed route until the

final plans were approved in the fall of 1967, shortly be

fore they filed suit. The general route of the road was

published in a newspaper in 1957, but most of the harmful

consequences were the result of subsequent decisions made

without notice to the public. For example, the decisions

that will insure destruction of the business section of Jef

ferson Street are the decisions to build the 1-40 route just

north of Jefferson Street (taking the back of the business

properties) and also to widen Jefferson Street as an ar

terial road (taking the front of these businesses). This

type of detail, which vitally affects the situation, was not

known by petitioners for any appreciable period of time

before suit was filed. It is not fair to say that petitioners

“ slept on their rights” so as to be barred from equitable

relief.

Despite the land acquisitions by the State, some forms