Michigan Civil Rights Initiative Committee v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action Brief in Opposition

Public Court Documents

June 11, 2008

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Michigan Civil Rights Initiative Committee v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action Brief in Opposition, 2008. a1ea19a0-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10040c73-287f-421e-90eb-cb9c17b8b944/michigan-civil-rights-initiative-committee-v-coalition-to-defend-affirmative-action-brief-in-opposition. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

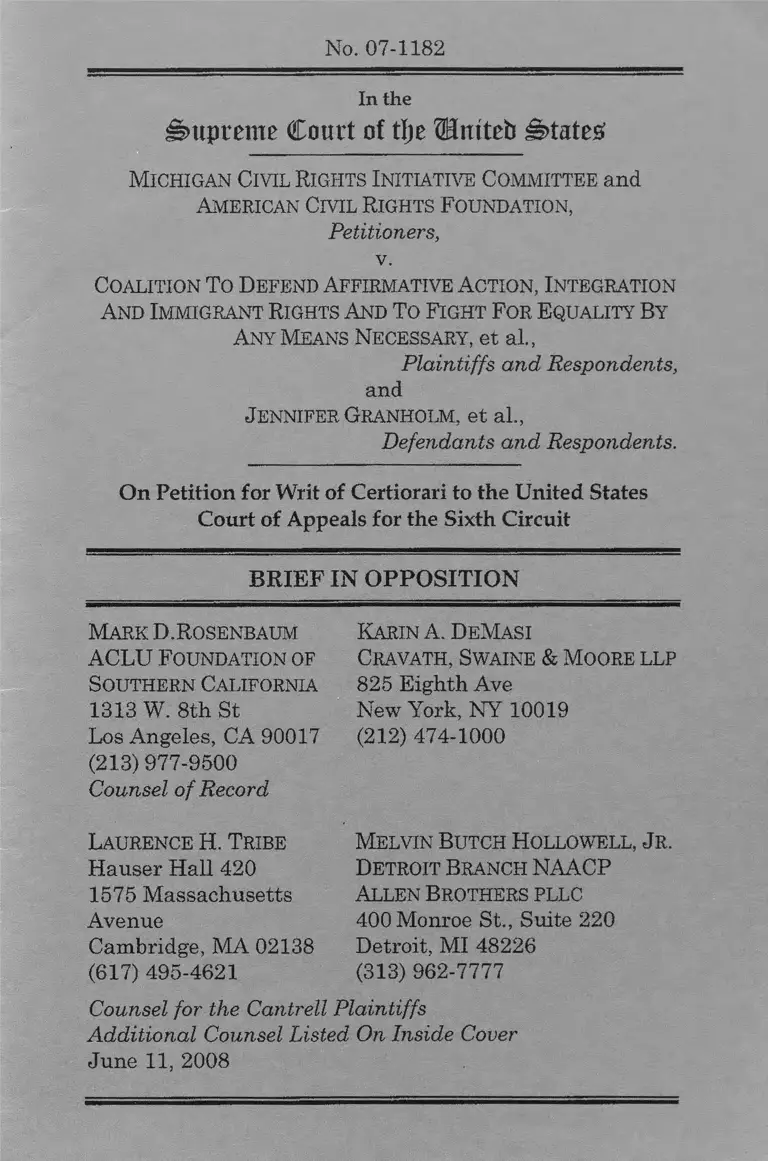

No. 07-1182

In the

Supreme Court of tfje Wniteb States?

Michigan Civil Rights Initiative Committee and

American Civil Rights Foundation,

Petitioners,

v.

Coalition To Defend Affirmative Action, Integration

A nd Immigrant Rights And To Fight For Equality By

Any Means Necessary, et al.,

Plaintiffs and Respondents,

and

Jennifer Granholm, et al.,

Defendants and Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

Mark D. Rosenbaum

ACLU Foundation of

Southern California

1313 W. 8th St

Los Angeles, CA 90017

(213) 977-9500

Counsel o f Record

Karin A. DeMasi

Cravath, Swaine & Moore llp

825 Eighth Ave

New York, NY 10019

(212) 474-1000

Laurence H. Tribe

Hauser Hall 420

1575 Massachusetts

Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

(617) 495-4621

Melvin Butch Hollowell, Jr .

Detroit Branch NAACP

Allen Brothers pllc

400 Monroe St., Suite 220

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-7777

Counsel for the Cantrell Plaintiffs

Additional Counsel Listed On Inside Cover

June 11, 2008

Kary L. Moss

Michael J, Steinberg

Mark P. Fancher

American Civtl

Liberties Union Fund

of M ichigan

60 W. Hancock Street

Detroit, MI 48201

(313) 578-6814

John Payton

Jacqueline A. Berrien

Victor Bolden

A nurima Bhargava

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Jerome R. Watson

Miller, Canfield,

Paddock and Stone,

P.L.C.

150 West Jefferson

Suite 2500

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 963-6420

Dennis Parker

Steven R. Shapiro

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, N.Y. 10004

(212) 549-2500

Erwin Chemerinsky

Duke University School of

Law

Science Drive & Towerview Rd.

Durham, NC 27708

(919) 613-7173

Daniel P. Tokaji

The Ohio State University

Moritz College of Law

55 W. 12th Ave.

Columbus, OH 43206

(614) 292-6566

Counsel For the Cantrell Plaintiffs

1

COUNTERSTATEM ENT OF THE QUESTION

PRESENTED

Should the Court abandon the settled four-

element inquiry under Rule 24(a)(2) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, substituting a per se rule

that ballot-initiative sponsors always have a right to

intervene in litigation challenging measures enacted

with their support because state governments, as a

matter of law, are categorically disqualified from

mounting an adequate defense of such measures?

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE QUESTION

PRESENTED........................................................... i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES......................................... in

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION....................................... 1

COUNTERSTATEMENT OF THE CASE...................2

REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION'........... 3

I. The Decision Below Is Consistent With Well-

Settled Law and Reflects the Sound Policy

Judgments Embodied in Rule 24(a)(2)................. 4

II. Petitioners’ Proposed Per Se Rule Would

Conflate the Elements of the Rule 24(a)(2)

Analysis, Ignore the Reality that State

Governments Can Competently Defend

Their Own Laws, and Eviscerate the

Discretion of the District Courts........................... 7

III. The “Direct and Dramatic” Inter-Circuit

Conflict Petitioners Claim to Identify Does

Not Exist........................................................ 12

CONCLUSION 15

Ill

TABLE OF AUTH ORITIES

Page(s)

Cases

Arizonans for Official English u. Arizona,

520 U.S. 43 (1997).....................................................5

Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v.

Granholm, 240 F.R.D. 368 (E.D. Mich.

2006)...................................................................... 2, 12

Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v.

Granholm, 501 F.3d 775 (6th Cir. 2007)..... passim

Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v.

Granholm, 539 F. Supp. 2d 924 (2008).................. 9

Diamond v. Charles, 476 U.S. 54 (1986)...................... 6

FM Properties Operating Co. v. City of

Austin, 71 F.3d 879, 1995 WL 727288

(5th Cir. 1995)..............................................................4

Forest Conservation Council v. U.S. Forest

Serv., 66 F.3d 1489 (9th Cir. 1995)................ 13, 14

Idaho v. Freeman, 625 F.2d 886 (9th Cir.

1980).......................................................................... 14

Izumi Seimitsu Kogyo Kabushiki Kaisha v.

U.S. Philips Corp., 510 U.S. 27 (1993).......... 1, 7, 8

Jenkins v. Missouri, 78 F.3d 1270 (8th Cir.

1996) 9

IV

Page(s)

Keith u. Daley, 764 F.2d 1265 (7th Cir.

1985).................................... ....................................4, 5

League of Latin American Citizens v.

Wilson, 131 F.3d 1297 (9th Cir. 1997)........... 11, 14

Mich. State AFL-CIO v. Miller, 103 F.3d

1240 (6th Cir. 1997)................................................ 12

Mo.-Kan. Pipe Line Co. v. Utiited States,

312U.S. 502 (1941)..................................................1

Northland Family Planning Clinic, Inc. v.

Cox, 487 F.3d 323 (6th Cir. 2007)................ 4, 6, 12

Northwest Forest Resource Council v.

Glickman, 82 F.3d 825 (9th Cir. 1996)........... .......9

Prete v. Bradbury, 438 F.3d 949 (9th Cir.

2006)...................................................................... 4, 14

Providence Baptist Church v. Hillandale

Comm., Ltd., 425 F.3d 309 (6th Cir.

2005)............................ 6

Sagebrush Rebellion, Inc. v. Watt, 713 F.2d

525 (9th Cir. 1983)................................... . 10, 11, 13

Standing Together to Oppose Partial-

Birth-Abortion v. Northland Family

Planning Clinic, Inc., 128 S. Ct. 872

(2008)............................... ......................................... . 6

United States v. Michigan, 424 F.3d 438

(6th Cir. 2005)........... 4

V

Page(s)

Washington State Building & Construction

Trades Council v. Spellman, 684 F.2d

627 (9th Cir. 1982).................................................. 13

Wisniewski v. United States, 353 U.S. 901

(1957)........................................................................ 14

Statutes & R ules

Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a)(2)........................................ passim

Fed. R. Civ. P. 59 ........................................................... 3

Mich. Comp. Laws § 14.28............................................. 8

Other A uthorities

7A C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice

and Procedure § 1904 (1972)................................. 13

Mich. Const. Art. 2, § 9 .................................................11

1

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION

The petition seeks review of a decision that is

consistent with settled law, supported by robust

policy considerations, and of a sort this Court has

long recognized to be rarely appropriate for

discretionary review.1 See Mo.-Kan. Pipe Line Co. v.

United States, 312 U.S. 502, 506 (1941) (!t[T]he

circumstances under which interested outsiders

should be allowed to become participants in a

litigation [are], barring very special circumstances, a

matter for the [trial] court”); Izumi Seimitsu Kogyo

Kabushiki Kaisha v. U.S. Philips Corp., 510 U.S. 27,

33-34 (1993) (per curiam) (noting that “ [w]hile the

decision on any particular motion to intervene may

be a difficult one, it is always to some extent bound

up in the facts of the particular case” and that

“addressing a relatively factbound issue . . . does not

meet the standards that guide the exercise of our

certiorari jurisdiction”).

For these reasons, set forth more fully below,

Respondents Chase Cantrell, et al. (the “Cantrell

Plaintiffs”) request that the Court deny the petition

for a writ of certiorari to review the opinion of the

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reported at

501 F.3d 775.

1 The Cantrell Plaintiffs file this brief at the Court’s

request; believing the petition to he without merit, they initially

waived then’ right to file an opposition brief.

2

COUNTERSTATEM ENT OF THE CASE

The underlying litigation is a constitutional

challenge to Michigan’s ban on affirmative action

(“Proposal 2”), enacted in November 2006 through

the state’s ballot initiative process. Plaintiffs are

two, separate putative classes that include students,

prospective students and faculty at Michigan’s public

universities.2 The original named defendants were

the Governor of Michigan and each of Michigan’s

three public universities.

Shortly after the complaint was filed, Michigan

Attorney General Michael A. Cox was granted leave

to intervene as a defendant in light of his statutory

duty to defend the state’s laws from constitutional

challenge and his strong support for Proposal 2. See

Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v. Granholm,

240 F.R.D. 368, 371 (E.D. Mich. 2006). The district

court also permitted the intervention of a white male

Michigan resident who sought to protect his interest

in having his then-pending law school application

decided with Proposal 2 in effect. The district court

denied motions to intervene by the ballot-question

committee that sponsored Proposal 2 (the Michigan

Civil Rights Initiative Committee (“MCRIC”)), and

two other political organizations (the American Civil

Rights Foundation (“ACRF’) and Toward a Fair

Michigan (“TAFM”)). Id. On September 6, 2007, the

Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s denial

of intervention with respect to each of those

2 These two groups, represented by separate counsel, are

referred to as the “Coalition Plaintiffs” and the “Cantrell

Plaintiffs”.

3

organizations, holding that they “lackjed] a

substantial legal interest in the outcome of this

case.” Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action v.

Granholm, 501 F.3d 775, 783 (6th Cir. 2007).

MCRIC and ACRF (“Petitioners”) unsuccessfully

sought en banc review, and now petition this Court

for a writ of certiorari.

Governor Granholm was dismissed from this

action on September 5, 2007. The remaining parties

have conducted thorough discovery, followed by

dispositive motion practice. On March 18, 2008, the

district court granted Attorney General Cox’s motion

for summary judgment and dismissed both the

Cantrell and Coalition Plaintiffs’ claims. A motion

by the Cantrell Plaintiffs to alter or amend the

judgment pursuant to Rule 59 of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure was timely filed with the District

Coui’t on April 1, 2008, and is currently pending.

REASONS FOR DENYING THE PETITION

The petition should be denied because the

decision below reflects the proper application of well-

settled law. Moreover, the petition seeks the

wholesale replacement of the intervention inquiry

under Rule 24(a)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure and invites this Court to create an

unnecessary and counterproductive per se rule - that

states can never adequately defend ballot-enacted

legislation - which is repulsive to both the dignity of

state governments and the sound discretion of the

district courts.

4

I. The Decision Below Is Consistent W ith

W ell-Settled Law and Reflects the Sound

Policy Judgm ents Em bodied in Rule

24(a)(2).

The rule in every circuit - as Petitioners do not

dispute - is that a proposed intervenor must

establish four conditions in order to obtain

intervention as of right under Rule 24(a)(2): (1) that

the motion to intervene is timely; (2) that the

proposed intervenor has a substantial legal interest

in the subject matter of the case; (3) that the

proposed intervenor’s ability to protect that interest

may be impaired in the absence of intervention; and

(4) that the parties already before the court may not

adequately represent the proposed intervenor s

interest. United States v. Michigan, 424 F.3d 438,

443 (6th Cir. 2005); see also, e.g., Prete v. Bradbury,

438 F.3d 949, 954 (9th Cir. 2006); Keith v. Daley, 764

F.2d 1265, 1268 (7th Cir. 1985).

Courts have held repeatedly that an advocacy

group that employs an initiative process to secure

enactment of a new law lacks a cognizable interest

entitling it to intervene as of right in subsequent

litigation challenging such an enactment’s validity -

unless the group itself is regulated by the law.

Coalition, 501 F.3d 775; Northland Family Planning

Clinic, Inc. v. Cox, 487 F.3d 323 (6th Cir. 2007); see

also FM Properties Operating Co. v. City of Austin,

71 F.3d 879, 1995 WL 727288, at *2 (5th Cir. 1995)

(unpublished table disposition) (affirming denial of

intervention by conservation organization

notwithstanding its argument “that as the

representative of the sponsor of the ballot initiative

[whose application was at issue], it had a per se right

5

to intervene”); Keith, 764 F.2d at 1270 (affirming

denial of intervention by pro-life advocacy group,

explaining that such a group was not entitled “to

forever defend statutes it helped enact”).3

The opinion below is firmly grounded in that

precedent. It is also consistent with this Court’s

skepticism respecting ballot initiative sponsors’

purported “quasi-legislative interest in defending the

constitutionality of the measure they successfully

sponsored.” Arizonans for Official English u.

Arizona, 520 U.S. 43, 65-66 (1997) (vacating

judgment appealed from on other grounds, but

adverting to “grave doubts” as to whether ballot

initiative sponsors had standing to pursue an appeal

in view of the fact that “this Court has [njever

identified initiative proponents as Article-III-

qualified defenders of the measures they advocated”).

Specifically the Sixth Circuit in the instant case

explained that Petitioners “have only a general

ideological interest in seeing that Michigan enforces

Proposal 2”, noted that “neither the MCRI[C] nor the

ACRF maintains that it or its members are

specifically regulated by those portions of Michigan’s

constitution amended by Proposal 2” and held that

“ [a]n interest so generalized will not support a claim

3 As discussed more fully infra at Section III, the “direct

and dramatic” circuit split Petitioners claim to identify with

respect to this issue (Pet. at 17) rests entirely on a single

paragraph, arguably dicta, in one case from the Ninth Circuit.

6

for intervention as of right.” 501 F.3d at 782

(internal quotation marks omitted).4

This settled rule is supported by sound policy.

There are compelling reasons not to enact a

presumptive right for ballot sponsors to intervene in

litigation challenging measures whose enactment

they supported. Most fundamentally, our political

system allocates to the state primary responsibility

for defense and enforcement of the law. Northland,

487 F.3d at 345 (“ [T]he public interest in [an enacted

measure’s] enforceability is entrusted for the most

part to the government.”); Diamond v. Charles, 476

U.S. 54, 65 (1986) (explaining that “the power to

create and enforce a legal code, both civil and

criminal[,] is one of the quintessential functions of a

State” and that only the State has a “direct stake . . .

in defending the standards embodied in that code”)

(internal citations and quotation marks omitted).

See also Providence Baptist Church v. Hillandale

Comm., Ltd., 425 F.3d 309, 317 (6th Cir. 2005).

Moreover, as discussed more fully below, Rule

24(a)(2) is designed to give the district courts

4 The Sixth Circuit also noted that another panel of that

Court had recently reached the same conclusion in a nearly

identical case. See Northland, 487 F.3d at 345 (affirming denial

of intervention to the sponsor of a citizen-initiative process

resulting in enactment of Michigan’s Legal Birth Definition Act,

holding that the organization’s “legal interest can be said to be

limited to the passage of the Act rather than the state’s

subsequent implementation and enforcement of it.”) This Court

denied a petition for certiorari by the proposed intervenor in

that case on January 7, 2008. Standing Together to Oppose

Partial-Birth-Abortion v. Northland Family Planning Clinic,

Inc., 128 S. Ct. 872 (2008).

flexibility and discretion in addressing the

“factbound” question of which persons or entities are

appropriately situated to participate in any

particular litigation. See Izurni, 510 U.S. at 34. That

question is as germane to a constitutional challenge

to a ballot-enacted measure as it is to any other form

of litigation.

II. Petitioners’ Proposed Per Se Rule W ould

Conflate the Elem ents o f the Rule 24(a)(2)

Analysis, Ignore the Reality that State

Governm ents Can Com petently Defend

Their Own Laws, and Eviscerate the

D iscretion of the District Courts.

As Petitioners openly concede, their theory for

why this Court should grant review rests upon a

conflation of at least two of the four well-established

elements of the intervention analysis under Rule

24(a)(2). See Pet. at 24 (insisting that “the adequacy

with which Petitioners' interests will be represented

effectively determines the substantiality of those

interests”). As noted above, a movant must establish

four elements to intervene as of right: (1) timeliness;

(2) cognizable legal interest; (3) potential impairment

of that interest; and (4) inadequacy of representation

by those already parties. See infra Part I.

Petitioners, however, contend that ballot

initiative sponsors always have a legally cognizable

interest in litigation challenging enactments they

have supported because the government can never be

trusted to enforce and defend such laws itself. Thus,

by conflating the “interest” and “adequacy” elements

of the intervention analysis, Petitioners’ rule would

eliminate the “factbound” inquiry contemplated by

8

Rule 24(a)(2).5 See Izumi, 510 U.S. at 33-34. This

represents both a radical and unsupported departure

from the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and a

disparagement of public servants who. like Attorney

General Cox, competently and zealously defend the

laws as they are sworn to do.

The Attorney General intervened in this

litigation with the express purpose of ensuring a

“vigorous defense” of Proposal 2. Cox Mot. to

Intervene, at 5, 7, l l . 6 As “the state’s chief law

enforcement officer”, the Attorney General “has not

only a duty to ensure that the laws of the State are

followed, but also a duty to defend those laws as

enacted . . . by the People of Michigan themselves,

when those laws are challenged” . Id. at 13-14. See

also Mich. Comp. Laws § 14.28.

And Attorney General Cox has steadfastly

fulfilled that role. From his first appearance in this

litigation, the Attorney General has actively

defended Proposal 2. He contested nearly 90% of

Plaintiffs’ Joint Proposed Stipulation Of Facts,

5 Petitioners’ amicus Mountain States Legal Foundation

would apparently have the Court abrogate the four-factor test

(and hence Rule 24(a)(2)) altogether, in favor of a “bright line

rule that an initiative’s sponsors may, as a matter of right,

intervene in litigation challenging the constitutionality of their

[sic] enactment”. Amicus Curiae Brief of Mountain States

Legal Foundation In Support of Petitioners at 10. That self-

serving suggestion, of course, could not be implemented without

amending Federal Rule 24 and overturning decades of well-

reasoned precedent.

6 A copy of the Attorney General’s Motion to Intervene is

appended hereto.

9

opposed both the Cantrell and Coalition Plaintiffs’

motions for class certification, and actively

participated in discovery. Moreover, the Attorney

General’s representatives have briefed, argued and

now won a motion for summary judgment as to all

claims presented by both sets of plaintiffs. Coalition

to Defend Affirmative Action v. Granholm, 539 F.

Supp. 2d 924 (2008). It is beyond legitimate dispute

that Attorney General Cox has zealously represented

the interests of all those who support Proposal 2 -

including Petitioners - and there is every reason to

believe that he will continue to do so in the event

that further proceedings take place in the district

court or in the Sixth Circuit.7 Moreover, petitioners

have not identified, even at this late stage, a single

factual assertion or legal argument omitted by the

7 Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm, who was

initially named as a defendant, has been critical of Proposal 2.

However, the Governor has never taken an active role in the

litigation, and was voluntarily dismissed from the action on

September 5, 2007 in light of the Attorney General’s

intervention. Petitioners also make much of a temporary (and

extremely short-lived) stipulated injunction entered by the

district court in the first weeks of the litigation. Pet. at 7, 23-

24. However, the practical and logistical considerations that

motivated the Attorney General to agree to that stipulation do

not undermine his ability to defend Proposal 2. See Northwest

Forest Resource Council v. Glickman, 82 F.3d 825, 838 (9th Cir.

1996) (holding that disagreement between a current party and

proposed intervenor over whether the district court should

enter a permanent injunction was “not central to [the]

declaratory judgment action” and “only a difference in strategy”

too “minor” to raise an inference of inadequate representation);

Jenkins v. Missouri, 78 F.3d 1270, 1275 (8th Cir. 1996) (“A

difference of opinion concerning litigation strategy . . . does not

overcome the presumption of adequate representation.”).

10

Attorney General that they would have proffered in

the course of this litigation.

The per se rule advocated by Petitioners is as

unworkable in practical terms as it is inconsistent

with the reality that state governments can - and as

in this case, frequently do - mount a robust defense

of legislation enacted through an initiative process.

To begin with, Petitioners do not identify which

supporters of a ballot initiative should in their view

have a per se right to intervene such litigation.

Petitioner ACRF, for instance, is an out-of-state,

nationwide organization devoted to the elimination

of affirmative action across the nation. It is not an

official ballot-question'committee. A presumption

that such organizations are entitled to intervene

would constitute a blanket license for virtually any

advocacy group to inject itself into litigation

addressing ballot-enacted legislation of concern to

them.

By contrast, a principal virtue of the four-part

test under Rule 24(a)(2) is the flexibility it affords

the district courts to control the identity and number

of the parties before them. See Sagebrush Rebellion,

Inc. v. Watt, 713 F.2d 525, 526 & n.2 (9th Cir. 1983)

(allowing intervention by the national office and five

local chapters of the National Audubon Society, five

Idaho non-profit environmental organizations and

four individual residents partly on the basis that

“ [throughout these proceedings intervenors have

asserted a unitary interest and spoken with one

voice” and cautioning that “ [njothing in this opinion

should be interpreted as approving participation by

11

the intervenors on any other basis”).8 Petitioners

would propose to strip the district courts of that

discretion with respect to such groups.

Indeed, a per se federal rule purporting to

delineate the categories of initiative supporters

entitled to intervene is impossible because each state

that permits legislation through referendum has its

own set of procedures for placing issues on the ballot.

Michigan law, in fact, provides for two such

procedures - each of which contemplates different

roles for sponsors, citizens, and the legislature.

Mich. Const. Art. 2, § 9. Moreover, Petitioners and

their amici appear to advocate for a perpetual right

to intervene - i.e. no matter how great the lapse of

time between a measure’s enactment and the

initiation of litigation challenging it.

The fatal complexity of any effort to deploy

Petitioners’ proposal in practice is matched only by

the absurdity of Petitioners’ premise that every

8 Moreover, the very evil that Petitioners purportedly seek

to remedy - conflicted and/or inadequate defense of popularly-

enacted legislation - is already expressly envisioned and

protected against by the current, well-settled rule. See

Sagebrush Rebellion, 713 F.2d at 528-29 (approving

intervention as defendant by advocacy group where legitimate

concern existed about the likelihood of zealous advocacy by a

government defendant who had been director of the legal

foundation representing the plaintiff prior to his appointment

as Secretary of the Interior); compare League of Latin American

Citizens v. Wilson, 131 F.3d 1297, 1305-07 (9th Cir. 1997)

(distinguishing Sagebrush Rebellion and noting that then-

California Governor Pete Wilson - a staunch advocate of the

ballot-measure there at issue - was well-qualified to supervise

its constitutional defense).

12

member of every state’s government is categorically

unable to defend any piece of ballot-enacted

legislation. This Court should reject Petitioners’

invitation to discard the fundamental presumption

that elected government officials can, at least in

many instances, both defend and enforce the laws of

their states.

III. The “Direct and Dram atic” Inter-Circuit

Conflict Petitioners Claim to Identify Does

Not Exist.

For all their efforts to manufacture a “direct and

dramatic [inter-Circuit] conflict. . . of major national

significance”, Pet. at 17, Petitioners manage to cite

only a single Ninth Circuit opinion holding that a

ballot-initiative sponsor was entitled to intervene as

of right in post-enactment litigation challenging a

measure it had supported.9 That opinion,

9 In an effort to imply that the Sixth Circuit’s own law is

somehow unsettled, Petitioners suggest that Northland and the

opinion below depart from Mich. State AFL-CIO u. Miller, 103

F.3d 1240 (6th Cir. 1997). As both the courts below recognized,

no such conflict exists. In Miller, the Sixth Circuit allowed the

Michigan Chamber of Commerce to intervene in litigation

challenging newly-enacted state campaign finance laws. But as

the Sixth Circuit has now repeatedly explained, Milter is

distinguishable because the intervening party was “an entity

also regulated by at least three of the four statutory provisions

challenged” in the litigation. Id. at 1247. See also Northland,

487 F.3d at 345 (pointing out that pro-life advocacy

organization that had sponsored citizen-initiative process,

unlike the Chamber of Commerce in Miller, was “not itself

regulated by any of the statutory provisions at issue here”); see

also Coalition, 501 F.3d 782. The district court distinguished

Miller on the same grounds. Coalition, 240 F.R.D. at 375.

13

Washington State Building & Construction Trades

Council v. Spellman, 684 F.2d 627 (9th Cir. 1982),

contains virtually no discussion of the rule it

announces - which was arguably dicta in any event,

since the same opinion simultaneously affirmed a

judgment on the merits identical to that sought by

the putative intervenors. Spellman’s entire

“analysis” of this issue is as follows:

“Denial of [the initiative sponsor’s] motion

to intervene was error and accordingly we

reverse as to that holding. Rule 24

traditionally has received a liberal

construction in favor of applicants for

intervention. 7A C. Wright & A, Miller,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 1904

(1972). [T]he public interest group that

sponsored the initiativeQ was entitled to

intervention as a matter of right under Rule

24(a). However, while we sustain [the

proposed intervenor’s] appeal, this reversal

does not require a new trial because the

holding of the case would not be changed.”

Id. at 629-30. The opinion contains no other

discussion of the intervention issue.

Petitioners’ other cases from the Ninth Circuit

do not concern intervention by ballot-initiative

sponsors and therefore are inapposite. See Forest

Conservation Council v. U.S. Forest Serv., 66 F.3d

1489 (9th Cir. 1995) (allowing intervention by state

and county in suit to enjoin implementation of

certain logging regulations); Sagebrush Rebellion 713

F.2d at 525 (allowing intervention by Audubon

Society and certain other entities in challenge to

14

regulatory action by the Department of the Interior);

Idaho v. Freeman, 625 F.2d 886 (9th Cir. 1980)

(allowing intervention by women’s rights

organization in legal challenge to procedures for

ratifying the Equal Rights Amendment). Notably,

Forest Conservation Council, Sagebrush Rebellion

and Freeman all involved challenges to rulemaking

or ratification procedures - none involved a challenge

to the validity of a law or regulation as enacted. Id.

In fact, other cases from the Ninth Circuit - not

cited in the petition - deny intervention to initiative

sponsors in Petitioners’ circumstances, consistent

with the result below. Wilson, 131 F.3d at 1297

(affirming denial of intervention by sponsors of

initiative intended to deny government benefits to

undocumented immigrants); see also Prete, 438 F.3d

at 959-60 (holding that grant of intervention to

sponsor and supporter of Oregon ballot initiative was

erroneous but, under the circumstances, harmless).

The present action is plainly an inappropriate

vehicle for resolution of any inconsistency within

Ninth Circuit caselaw. See Wisniewski v. United

States, 353 U.S. 901, 902 (1957) (per curiam)

(holding that “doubt about the respect to be accorded

to a previous decision of a different panel [of the

same Court of Appeals] should not be the occasion”

for a writ of certiorari).

15

CONCLUSION

For all of the foregoing reasons, the petition

should be denied.

June 11, 2008

Respectfully Submitted,

/S/Mark D. Rosenbaum

Mark D. Rosenbaum

ACLU Foundation of Southern

California

1313 W. 8th Street

Los Angeles, CA 90017

(213) 977-9500

Counsel of Record

Laurence H. Tribe

Hauser Hall 420

1575 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

(617) 495-4621

Karin A. DbMasi

Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP

825 Eighth Avenue

New York, NY 10019

(212) 474-1000

16

Melvin Butch Hollowell, Jr .

Detroit Branch NAACP

Allen Brothers PLLC

400 Monroe Street, Suite 220

Detroit, MI 48226

(313) 962-7777

Kary L. Moss

Michael J. Steinberg

MarkP. Fancher

American Civil Liberties Union

Fund of Michigan

60 W. Hancock Street

Detroit, MI 48201

(313) 578-6814

John Payton

Jacqueline A. Berrien

Victor Bolden

Anurima Bhargava

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 965-2200

Dennis Parker

Steven R. Shapiro

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

125 Broad Street

New York, N.Y. 10004

(212) 549-2500

17

Erwin Chemerinsky

Duke University School of Law

Science Drive & Towerview Rd.

Durham, NC 27708

(919) 613-7173

Daniel P. Tokaji

The Ohio State University

Moritz College of Law

55 W. 12th Avenue

Columbus, OH 43206

(614) 292-6566

APPENDIX

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Document 8 Filed 12/14/2006 Page 1 of 18

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

COALITION TO DEFEND AFFIRMATIVE Case No, 2:06-CV-15024

ACTION. INTEGRATION AND IMMIGRANT

RIGHTS AND FIGHT FOR EQUALITY BY AN Y Hon. David M. Lawson

MEANS NECESSARY (BAM N ). UNITED FOR

EQUALITY AND AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

LECAL DEFENSE FUND. RAINBOW PUSH

COALITION. CALVIN JEVON COCHRAN.

LASHELLE BENJAMIN, BEAUT1E MITCHELL.

DENESHA RICHEY. STASIA BROWN. MICHAEL

GIBSON. CHRISTOPHER SUTTON, LAQUAY

JOHNSON. TURQOISE WISE-KINO, BRANDON

FLANN1GAN. JOS1E HUMAN, ISSAMAR

CAM ACH O. KAHLEIF HENRY. SHANAE

TA TU M . M ARICRUZ LOPEZ, ALEJANDRA

CRUZ. ADARENE HOAG. CANDICE YOUNG.

TRISTAN TA YLO R. WILLIAMS FRAZIER

JERRELL ERVES. MATTHEW GRIFFITH,

LACRISSA BEVERLY, D'SHAWNM

FEATHERSTONE. DANIELLE NELSON, JULIUS

CARTER. KEVIN SMITH. KYLE SMITH, PARIS

BU TL ER TOUISSANT KING. A1ANA SCOTT.

ALLEN VONOU, RANDIAH GREEN. BRITTANY

JONES. COURTNEY DRAKE. DANTE DIXON,

JOSEPH HENRY RED. AFSCME LOCAL 207.

AFSCME LOCAL 2 14. AFSCME LOCAL 312.

AFSCME LOCAL 836. AFSCME LOCAL 1642.

AFSCME LOCAL 2920. and the DEFEND

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION PARTY.

JENNIFER GRANHOLM, in her official capacity as

Governor o f the State o f Michigan, the REGENTS

OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, the

BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF MICHIGAN STATE

UNIVERSITY, the BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF

W AYN E STATE UNIVERSITY, and the

TRUSTEES OF any other public college or

university, community college, or school district.

Defendants

and

The REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

MICHIGAN, the BOARD OF TRUSTEES OF

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY and the BOARD

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DMl-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 2 of 18

OF GOVERNORS OF WAYNE STA TE

UNIVERSITY.

Cross-Plaintiffs

vs.

JENNIFER GRANH O LM . in her official capacity as

Governor o f the State o f Michigan.

Cross-Defendant.

___ _______ /

George B. Washington (P26201)

Shanta Driver (P65007

SCHEFF & W ASHINGTON, P.C.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

645 Griswold. Suite 1817

Detroit Ml 48226

(313)963-1921

James E. Long (P53251)

Brian O. Neil (P 63511)

Michigan Department o f Attorney General

Attorneys for Defendant Granholm

P.O. Box 30758

Lansing. Mi 48909

(517) 373-1111

Leonard M. Niehoff(P36695)

Philip J. Kessler (P15921)

Christopher M. Taylor (P63780)

BUTZEL LONG. P.C.

Attorneys for Defendant/Cross-

Plaintilfs. the Regents o f the University

o f Michigan, Ihe Board o f Trustees o f

Michigan State University, and the

Board o f Governors o f Wayne State

University

350 S. Main Street, Suite 300

Ann Arbor. Ml 48104

(734)995-3110

Margaret A. Nelson (P30342)

Heather S, Meingast (P55439)

Joseph E. Potchen (P49501)

Michigan Dept o f Attorney General

Attorneys for Intervening D e f C ox

P.O. Box 30736

Lansing, M l 48909

(517)373-6434

ATTORNEY GENERAL MICHAEL A. COX'S MOTION TO INTERVENE AS A

DEFENDANT IN THE COMPLAINT FILED BY PLAINTIFFS, AND IN THE CROSS

CLAIM FILED BY THE DEFENDANT UNIVERSITIES

N OW COMES Attorney General Michael A . Cox, by his attorneys, Margaret A . Nelson,

Heather S. Meingast, and Joseph E. Potchen, Assistant Attorneys General, and in support o f his

motion to intervene states as follows:

2

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Document 8 Filed 12/14/2006 Page 3 of 18

!, On November S. 2006, Plaintiffs filed with this Court a complaint for injunctive

and declaratory relief raising a facial challenge to newly adopted art i , § 26 o f the Michigan

Constitution, better known as Proposal 2. The complaint alleges equal protection and First

Amendment challenges under the federal constitution. The complaint also asserts that § 26 is

preempted by the Civil Rights Act o f 1866, Titles VI and V ll and, the Civil Rights Act o f 1964,

and Title XI o f the education Amendments o f 1972. Plaintiffs request that this Court declare §

26 unconstitutional under the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause o f the

Fourteenth Amendment and permanently enjoin defendants from eliminating any affirmative

action plans and granting any other relief it determines appropriate.

2. The complaint names as defendants Governor Jennifer Granholm, in her official

capacity, the Regents o f the University o f Michigan, the Michigan State University Board o f

Trustees, and the Wayne State University Board o f Governors.

3. Although Plaintiffs filed their suit the day after the election, they did not serve the

Governor until December 8. 2006.

4. The Defendant Universities then filed their cross claim on December 11, 2006.

The cross claim asserts a violation o f the Universities' alleged First Amendment right o f

academic freedom to admit a class that best meets their academic goals during the current

admissions cycle i f the Universities are required to implement § 26 upon the section's effective

d a te - 12:01 a.m. December 23. 2007.'

5. The Universities assert they have already begun both their admissions and

financial aid cycles, with some decisions being made prior to the passage o f § 26. They allege

that to implement § 26 now, in the middle o f that cycle, would require them to apply different

polices to applicants within the same cycle and different polices than they have announced as 1

1 Sea Const 1963. art 12. § 2 providing for the effective date o f § 26.

3

Case 2:06-ov-15024-DML-RSW Document 8 Filed 12/14/2006 Page 4 of 18

applicable to this cycle. The Universities also allege that the amendment's exceptions applicable

to federal programs, federal law, and the federal constitution apply to their admissions policy and

effectively exempt them from the amendment's provisions.

6. The Universities request a judgment declaring that under federal law the

Universities may continue to use their existing admissions and financial aid policies through the

end o f the current cycle, and otherwise declaring their rights and responsibilities under the

Amendment in tight o f federal law.

7. The Universities also filed a motion for preliminary injunction and requested an

expedited hearing in the matter. The Universities seek a preliminary injunction enjoining the

application o f § 26 to preserve the status quo and allow the Universities to continue to use their

existing admissions and financial aid policies through the end o f the current cycle or until the

Court enters its declaratory judgment. Alternatively, i f the Court cannot rule by December 22,

2006. the Universities ask this Court to enter a temporary restraining order pending a ruling on

the preliminary injunction.

8. On December 11.2006, Governor Granholm formally requested that the Attorney

General provide her with legal representation in this suit as provided for by the state constitution

and statutes.2 Recognizing a potential legal conflict because o f the differing poiitical positions

taken by the Governor and the Attorney General on Proposal 2, now Const 1963, art I, § 26,

Governor Granholm requested the creation o f a conflict wall to assure the independence o f her

assigned legal team. (See Exhibit 1) Governor Granholm also indicated she will not oppose the

Attorney General’s intervention in this matter.

- See Const 1963. art 5. §§ 3. 21; MCL 14.28.

4

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 5 of 18

9. In acknowledgement o f a legal conflict, and pursuant to the Governor's request,

the Attorney General has assigned an independent team o f Assistant Attorneys General and

established a conflict wall.

10. These unique circumstances, however, compel the Attorney Genera! to seek leave

to intervene in both the complaint and cross claim filed in this matter in order to ensure that the

Court is presented with the full range o f arguments on the questions presented, and so that a

vigorous defense o f the constitutionality o f § 26 may be had.

11. Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure 24, states:

(a) Intervention o f Right. Upon timely application anyone shall be permitted to

intervene in an action :. . . (2) when the applicant claims an interest relating to the

. . . transaction which is the subject o f the action and the applicant is so situated

that the disposition o f the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the

applicant's ability to protect that interest, unless the applicant's interest is

adequately represented by existing parties.

(b) Permissive intervention. Upon timely application anyone may be permitted to

intervene in an action :. . . (2 ) when an applicant's claim or defense and the main

action have a question o f law or fact in common. When a party to an action relies

for ground o f claim or defense upon any statute or executive order administered

by a federal or state governmental officer or agency or upon any regulation, order,

requirement, or agreement issued or made pursuant to the statute or executive

order, the officer or agency upon timely application may be permitted to intervene

in the action, in exercising its discretion the court shall consider whether the

intervention will unduly delay or prejudice the adjudication o f the rights o f the

original parties. [Emphasis added.]

12. Again the Attorney General, as the state’ s ch ief law enforcement officer, has not

only a duty to ensure that the laws o f the State are followed, but also a duty to defend those laws

as enacted by the Legislature, or as in this case by the People o f Michigan themselves, when

5

Case 2:06-cv-15024-0 ML-RSW Documents filed 12/14/2006 Page 6 of 18

those laws are challenged!.3 Concomitant with those duties is the Attorney General’ s right under

Michigan law to intervene in any matter to protect state interests.4 * 6

13. The Attorney General thus has a substantial legal interest in this matter relating to

his duty to defend the constitutionality o f § 26 on behalf o f the State o f Michigan, which interest

will not be adequately represented through Governor Granholm’ s participation in this suit.

14. The United States Court o f Appeals for the Sixth Circuit recognized in Associated

Builders & Contrs, Saginaw Valley Area Chapter v Perry that the Attorney General has broad

authority to intervene in matters affecting the public’ s interests, and that he should only be

prohibited from doing so when it would prove inimical to the public interest. s In that case, the

Sixth Circuit determined that then Attorney General Frank Kelley should have been allowed to

intervene as o f right and appeal a district court decision that held a state statute preempted by

federal law where the defendant Director o f the Department o f Labor and Governor did not

appeal, hut rather "permitted the thirty-year-old [statute] to go to its demise without fully

exercising their right to object.”4 The Court concluded that the State’ s interests were not

adequately represented by the decision not to appeal because substantial questions o f law existed

as to whether the state statute was in fact preempted by federal law. and that these circumstances

warranted the Attorney General’ s intervention and appeal in the matter.7

15. The circumstances here are analogous to those presented in Associated Builders

and support the Attorney General’ s intervention. While this case does not yet involve an appeal

3 Const 1963, art 5, §§ 3 ,21 ; MCL 14.28.

4 See MCL 14.101 See also Attorney General v Public Service Comm. 243 Mich App 487. 496-

497; 625 N\V2d 16 (2000).

2 Associated Builders & Contrs., Saginaw Valley Area Chapter v Perry, 115 F3d 386, 390 (CA

6. 1997).

6 Associated Builders, 115 F3d at 390.

7 Associated Builders, 115 F3d at 390-392.

6

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 7 of 18

and Governor Granholm remains an active party to the suit, it is clear that the State’ s interests as

a whole will not be adequately represented through the Governor’ s participation.

16. The Attorney General should thus be allowed to intervene as a matter o f right in

this case under FR Civ P 24(a) to ensure that the State’ s interests are adequately presented via a

vigorous defense o f the constitutionality o f § 26.

17. Alternatively, the Attorney General should be permitted to intervene under FR

C iv P 24(b) because his defense o f § 26 - that it withstands constitutional scrutiny under the First

Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment - will have questions o f fact or law in common

with the main action and original parties as required by the rule. His motion is timely and

permitting the Attorney General’ s intervention will in no way unduly delay or prejudice the

adjudication o f the rights o f the original parties since this suit is still in its initial phase.

Accordingly, intervention should be granted in accordance with FR Civ P 24(b).

18. Under LR 7 ,1(a). Attorney General Cox has sought concurrence in the motion to

intervene from all counsel to the parties in this action. The Governor does not oppose the

Attorney General's intervention. Counsel for the Universities was unable to respond before

speaking with his clients. Counsel for the Plaintiffs does not oppose the Attorney General's

intervention.

WHEREFORE, for the reasons set forth above and in the accompanying brief Attorney

General Michael A . C ox requests that this Court grant his Motion to Intervene pursuant to Fed R

Civ P 24(a) and (b).

7

Case 2:Q6-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 8 of 18

ATTORNEY GENERAL MICHAEL A. COX’S MEMORANDUM OF LAW

IN SUPPORT OF MOTION TO INTERVENE IN THE COMPLAINT

FILED BY PLAINTIFFS, AND IN THE CROSS CLAIM FILED BY THE

DEFENDANT UNIVERSITIES

CONCISE STATEMENT OF ISSUE PRESENTED

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24 accords persons (he opportunity to intervene in a

matter either as of right or by permission. Here, the Attorney General has a substantial

legal interest in the matters presented to this Court in the complaint and cross claim, which

challenge the constitutionality of Const 1963, art 1, § 26 and which interest will not be

adequately represented through Governor Granholm's participation in the suit thus

warranting his intervention as of right. Alternatively, the Attorney General should be

permitted to intervene because his defense of § 26 - that it withstands constitutional

scrutiny under the First Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment - will have questions

of fact or law in common with the main action and original parties. Should this Court

therefore exercise its discretion and allow the Attorney General to intervene either as of

right or by permission in the underlying complaint and cross claim?

CONTROLLING OR MOST APPROPRIATE AUTHORITY

Associated Builders & Contrs., Saginaw Valley Area Chapter v Perry, 115 F3d 386 (CA 6,

1997)

Attorney General v Public Service Comm, 243 Mich App 487,496-497; 625 NW 2d 16 (2000)

Jordan v Michigan Conference o f Teamsters Welfare Fund, 207 F3d 854, 863 (CA 6, 2000)

Linton v Commissioner o f Health & Evn't, 973 F2d 1311, 1319 (CA 6, 1992)

Michigan State v Miller, 103 F3d 1240, 1248 (C A 6, 1997)

Michigan State AFL-CIO v Miller. 103 F3d 1240, 1245 (C A 6, 1997)

Providence Baptist Church v Hillandale Comm, Ltd., 425 F3d 309, 313 (CA 6. 2005)

Stupak-Thrall v Glickman. 226 F3d 467, 471 (C A 6.2000)

United States v Michigan, 424 F3d 438, 443-444 (CA 6, 2005)

8

Case2:06-cv-15Q24-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 9 of 18

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

On Novem ber 8.2006. Plaintiffs filed with this Court a complaint for injunctive and

declaratory relief raising a facial challenge to newly adopted art 1, § 26 o f the Michigan

Constitution, better known as Proposal 2.8 The complaint alleges equal protection and First

Amendment challenges under the federal constitution. The complaint also asserts that § 26 is

preempted by the C ivil Rights Act o f 1866. Titles VI and VII and, the Civil Rights Act o f 1964,

and Title XI o f the education Amendments o f 1972. Plainti ffs request that this Court declare §

26 unconstitutional under the First Amendment and the Equal Protection Clause o f the

Fourteenth Amendment and permanently enjoin defendants from eliminating any affirmative

action plans and granting any other relief it determines appropriate. The complaint names as

defendants Governor Jennifer Granholm, in her official capacity, the Regents o f the University

o f Michigan, the Michigan State University Board o f Trustees, and the Wayne State University

Board o f Governors. Although Plaintiffs filed their suit the day after the election, they did not

serve the Governor until December 8,2006.

On Decem ber 11,2006, the defendant Universities filed a cross claim with this Court

against defendant Governor Granholm seeking declaratory and injunctive relief. The cross claim

asserts a violation o f the Universities' alleged First Amendment right o f academic freedom to ,

admit a class that best meets their academic goals during the current admissions cycle i f the

Universities are required to implement § 26 upon the section's effective date - 12:01 a,m.

December 2 3 ,2007.9 The Universities assert they have already begun both their admissions and

s The amendment passed overwhelmingly on November 7,2006, with 2,141,010 citizens voting

in favor o f the proposal, and 1,555.691 citizens voting against the proposal, or by 57.9 % to

42.1 %, See lillm/f'mihoecfr.ricrtisa.coni/election/resuils/OfiGEN,1'90000002.hlml.

’ See Const 1963, art 12, § 2 providing for the effective date o f § 26.

9

Case 2:06-cv-15Q24-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 10 of 18

imancial aid cycles, with some decisions being made prior to the passage o f § 26. They allege

that to implement § 26 now, in the middle o f that cycle, would require them to apply different

polices to applicants within the same cycie and different polices than they have announced as

applicable to this cycle. The Universities also allege that the amendment's exceptions applicable

to federal programs, federal law, and the federal constitution appfy to their admissions policy and

effectively exempt them from the amendments provisions. The Universities request a judgment

declaring that under federal law the Universities may continue to use their existing admissions

and financial aid policies through the end o f the current cycle, and otherwise declaring their

rights and responsibilities under the Amendment in light o f federal law.

The Universities also filed a motion for preliminary injunction and requested an

expedited hearing in the matter. The Universities seek a preliminary injunction enjoining the

application ot § 26 to preserve the status quo and allow the Universities to continue to use their

existing admissions and financial aid policies through the end o f the current cycle or until the

Court enters its declaratory judgment. Alternatively, i f the Court cannot rule by December 22.

2006. the Universities ask this Court to enter a temporary restraining order pending a ruling on

the preliminary injunction.

On December 11, 2006, Governor Granholm formally requested that the Attorney

General provide her with legal representation in this suit as provided for by the state constitution

and statutes."1 Recognizing a potential legal conflict because o f the differing political positions

taken by the Governor and the Attorney General on Proposal 2 , now art 1. § 26. Governor

Granholm requested the creation o f a conflict wall to assure the independence o f her assigned 10

10 See Const 1963. arts, §§ 3, 21: MCI. 14.28.

10

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Document 8 Filed 12/14/2006 Page 11 of 18

legal team. Governor Granholm also indicated she will not oppose the Attorney General's

intervention in this matter.

In acknowledgement o f the legal conflict, and pursuant to the Governor's request, the

Attorney General has assigned an independent team o f Assistant Attorneys General and

established a conflict wall.

These unique circumstances, however, compel the Attorney General to seek leave to

intervene in both the complaint and cross claim filed in this matter in order to ensure that the

Court is presented with the full range o f arguments on the questions presented, and so that a

vigorous defense o f the constitutionality o f § 26 may be had.

il

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 P age12o f18

ARGUMENT

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24 accords persons the opportunity to intervene in

a matter either as of right or by permission. Here, the Attorney General has a

substantial legal interest in the matters presented to this Court in the complaint and

cross claim, which challenge the constitutionality of Const 1963, art 1, § 26 and

which interest will not be adequately represented through Governor Granhoim's

participation in the suit thus warranting his intervention as of right. Alternatively,

the Attorney General should be permitted to intervene because his defense of § 26 -

that it withstands constitutional scrutiny under the First Amendment and the

Fourteenth Amendment - wifi have questions of fact or law in common with the

maiu action and original parties. This Court should therefore exercise its discretion

and allow the Attorney General to intervene either as of right or by permission in

the underlying complaint and cross claim.

A. Standard of Review

The decision whether to grant a motion to intervene lies within the discretion o f the

district court."

B. The Attorney General should be allowed to intervene as of right under FR

Civ 24(a).

Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure 24. states:

(a) intervention o f Right. Upon timely application anyone shall be permitted to

intervene in an action :. . . (2) when the applicant claims an interest relating to the

. . . transaction which is the subject o f the action and the applicant is so situated

that the disposition o f the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the

applicant's ability to protect that interest, unless the applicant's interest is

adequately represented by existing parties.

Four criteria must be met tor intervention as a matter o f right: (1) the application is

timely; (2) the party must have a substantial legal interest in the case; (3) the party must

demonstrate that its ability to protect that interest will be impaired in the absence o f intervention;

and (4) there must be inadequate representation o f that interest by the current party.11 12 I f any o f

11 Providence Baptist Church >' Hillandale Comm, Lid.. 425 F3d 309, 313 (CA 6, 2005).

12 See Michigan Stale AFL-CIU v Milter, 103 F3d 1240, 1245 (CA 6, 1997).

12

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 P age13o f18

these criteria are not satisfied, a motion to intervene must he denied.13 The Sixth Circuit has

adopted a "rather expansive notion o f the interest sufficient to invoke intervention."14

A proposed intervenor's burden in showing inadequate representation o f its interests is

minimal.15 A showing o f possible inadequate representation is sufficient to meet such burden.16 *

Despite such a minimal burden, "applicants for intervention must overcome the presumption o f

adequate representation that arises when they share the same ultimate objective as a party to the

suit."11 The Sixth Circuit has adopied a three-part test to determine if the existing parties

adequately represent the interests o f a proposed intervenor.18 19 The Sixth Circuit has held that a

movant fails to meet his burden o f demonstrating inadequate representation when ( I ) no

collusion is shown between the existing party and the opposition; (2) the existing party does not

have any interests adverse to the intervenor; and (3) the existing party has not failed in the

fulfillment orits duty.16

In reviewing these factors, it is apparent that the Attorney General's motion to intervene

is timely filed as the present lawsuit is in its initial phase. Moreover, the Attorney Genera! has a

substantial legal interest in this matter that will not be adequately represented by the existing

parties. The Altorney General, as the state’ s ch ief law enforcement officer, has not only a duty to

ensure that the laws o f the Slate are followed, but also a duty to defend those laws as enacted by

the Legislature, or as in this case by the People o f Michigan themselves, when those laws are

13 Smpak-Thrall v Glickman, 226 F3d 467. 47i (CA 6. 2000).

14 Michigan Slate AFL-C.IO. 103 F3d at 1245.

15 Linton i> Commissioner o f Health & Evn't, 973 F2d 1311, 1319 (CA 6. 1992).

16 Linton. 973 F2d at 1319.

11 United Slates v. Michigan, 424 F3d 438.443-444 (CA 6. 2005).

18 Jordan v Michigan Conference o f Teamsters Welfare Fund. 207 F3d 854. 863 (C A 6. 2000).

19 Jordan. 207 F3d at 863.

13

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 14 of 18

challenged."0 Concomitant with those duties is the Attorney General’ s right under Michigan law

to intervene in any matter to protect state interests.20 21 The Attorney General thus has a substantial

legal interest in this matter relating to his duty to defend the constitutionality o f § 26 on behalf o f

the State o f Michigan, which interest will not be adequately represented through Governor

Granholm’ s participation in this suit.

In Associated Builders & Contrs, Saginaw Valley Area Chapter v Perry the United States

Court o f Appeals for the Sixth Circuit recognized the Attorney General's broad authority and

duty to represent the interests o f the State22:

in Michigan exrel. Kelley v CR Equipment Sales, Inc, 898 F Supp 509, 513-14

(W D Mich 1995), District Judge Benjamin Gibson, discussing the same Attorney

General involved in the instant case, said:

"Michigan's Attorney General has broad authority to prosecute actions when to do

so is in the interest o f the state. First. Michigan statutory law provides as follows:

The attorney general shall prosecute and defend all actions in the supreme court,

in which the state shall be interested, or a party ... and may, when in his own

judgment the interests o f the state require it. intervene in and appear for the

people o f this state in any other court or tribunal, in any cause or matter, civil or

criminal, in which the people o f this state may be a party or interested. Mich.

Com p. Laws Ann. § 14.28 (West 1994). In addition, 'the attorney general has a

wide range o f powers at common law.' Mundy v McDonald, 216 Mich 444,450;

185 NW 877 (1921). Thus, the Attorney General 'has statutory and common law

authority to act on behalf o f the people o f the State o f Michigan in any cause or

matter, such authority being liberally construed.' Michigan State Chiropractic

Ass'n v Kelley, 79 Mich App 789; 262 NW2d 676, 677 (1977)(citations omitted);

see also Mundy. 216 Mich at 450. 185 NW 877 (Attorney General has broad

discretion 'in determining what matters may, or may not. be o f interest to the

people generally.’).

The Court should only prohibit the Attorney General from intervening or bringing

an action when to do so ’is clearly inimical to the public interest.' in re

20 Const !963, art 5, § § 3 .2 1 ; MCL 14.28.

21 See M CL 14.101 See also Attorney General v Public Service Comm. 243 Mich App 487. 496-

497: 625 NW2d 16 (2000).

~ Associated Builders & Contrs., Saginaw Valiev Area Chapter v Perry, 115 F3d 386, 390 (C A

6. 1997).

14

Case 2;0S-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 15 of 18

Intervention o f Attorney Gen.. 326 Mich 213; 40 NW2d 124. 126 (1949) (citation

omitted); see also Michigan Stale Chiropractic Ass'n. 262 NW 2d at 677.

Although a procedural distinction exists between intervention and initiating an

action, 'there is merger o f purpose, by reason o f public policy, when the interests

o f the State call for action by its ch ief law officer and there is no express

legislative restriction to the contrary.' In re Lewis' Estate, 287 M ich. 179. 184,

283 N.W. 21 (1938).” See also Humphrey v Kleinhardt, 157 FRD 404, 405 (W D

Mich 1994).

In that ease, the Sixth Circuit determined that then Attorney General Frank Kelley should have

been allowed to intervene as o f right and appeal a district court decision that held a state statute

preempted by federal law where the defendant Director o f the Department o f Labor and

Governor did not appeal, but rather “ permitted the thirty-year-old [statute] to go to its demise

without fully exercising their right to object.” 23 The Court concluded that the state’ s interests

were not adequately represented by the decision not to appeal because substantial questions o f

law existed as to whether the state statute was in fact preempted by federal law, and that these

circumstances warranted the Attorney General’ s intervention and appeal in the matter24:

The existence o f a substantia! unsettled question o f law is a proper circumstance

for allowing intervention and appeal. Where such uncertainty exists, one whose

interests have been affected adversely by a district court's decision should be

entitled to "receive the protection o f appellate review." A failure to seek such

protection may constitute inadequate representation warranting intervention.

"Although diligent prosecution may not require an appeal in every case . . . appeal

. . . should be liberally granted where the judgment o f the trial court raises

substantial and important questions o f law in relation to its correctness."

* * *

[The Attorney General's] burden o f demonstrating inadequacy o f representation

was minimal, not heavy. Unlike the questionable status o f the Electrical

Contractors’ Association in Perry I, [the Attorney General], representing the State

o f Michigan, has standing to argue the question o f ERISA preemption o f a state

statute.

The circumstances here are analogous to those presented in Associated Builders and support the

Attorney General’ s intervention. While this case does not yet involve an appeal and Governor

23 Associated Builders. 115 F3d at 390.

24 Associated Builders. 115 F3d at 390-392.

15

Case2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Document 8 Filed 12/14/2006 P age16o f18

Granholm remains an active party to the suit, it is clear that the State’s interests as a whole will

not be adequately represented through the Governor’ s participation given the conflict in legal

positions. Although there is no apparent collusion between the Governor and the plaintiffs or

the Universities as cross plaintiffs, it is expected that the Governor's legal position will more

closely align with the positions asserted by the plaintiffs and cross plaintiffs in this case. Under

these circumstances, the Attorney General has met his minimal burden o f showing possible - if

not probable - inadequate representation in the defense o f the constitutionality o f § 26 without

his intervention. Indeed. Governor Granholm has acknowledged the conflict between the

respective posilions. and does not oppose the Attorney General's intervention. For these reasons,

this Court should exercise its discretion and allow the Attorney General to intervene as o f right.

C. Alternatively, the Attorney General should be permitted to intervene under

FR Civ 24(b).

Federal Rule o f Civil Procedure 24, states:

b) Permissive Intervention. Upon timely application anyone may be permitted to

intervene in an action :. . . (2) when an applicant’s claim or defense and the main

action have a question o flaw or fact in common. When a party to an action relies

for ground o f claim or defense upon any statute or executive order administered

by a federal or state governmental officer or agency or upon any regulation, order,

requirement, or agreement issued or made pursuant to the statute or executive

order, the officer or agency upon timely application may be permitted to intervene

in the action. In exercising its discretion the court shall consider whether the

Should this Court determine that the Attorney General is not entitled to intervene as o f

right, he asks that this Court permit him to intervene under FR Civ P 24(b). Again, the Attorney

General's motion is timely since this lawsuit is in its infancy. In addition, the Attorney General's

defense o f § 26 - that it withstands constitutional scrutiny under the First Amendment and the

Fourteenth Amendment - will have questions o f fact or law in common with the main action and

16

Case 2:06-cv-15024-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 17 of 18

original parties as required by the rule.25 Finally, permitting the Attorney General’s intervention

will in no way unduly delay or prejudice the adjudication o f the rights o fth e original parties

since this suit is stiil in its initial phase and no substantive proceedings have taken place.

Accordingly, the Attorney General should permitted to intervene in accordance with FR Civ P

24(b).

CONCLUSION AND RELIEF SOUGHT

For the reasons set forth above and in the accompanying motion, Attorney General

Michael A. C ox respectfully requests that this Court exercise its discretion and grant his motion

to intervene in the complaint and cross claim filed in this matter pursuant to either FR Civ P

24(a) or (b).

Respectfully submitted,

Michael A. Cox

Attorney General

s/Margaret A. Nelson

Margaret A. Nelson (P 30342)

Heather S. Meingast (P55439)

Joseph Potchen (P4950I)

Assistant Attorneys General

Attorneys for Intervening Defendant Cox

Public Employment, Elections & Tort

P.O. Box 30736

Lansing, M l 48909

Dated: December 14,2006

25 See. e.g. Michigan State v Miller. 103 F3d 1240. 1248 (C A 6, 1997). where the Sixth Circuit

concluded that the Michigan Chamber o f Commerce should have been permitted to intervene in

a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality o f slate campaign finance laws because "[t]he

Chamber's claim that the 1994 amendments arc valid presents a question o f law common to the

main action."

17

Case 2:06-cv-15Q24-DML-RSW Documents Filed 12/14/2006 Page 18 of 18

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on December 14 ,2 0 0 6 .1 electronically filed the foregoing paper with the

Clerk o f the Court using the ECF system which will send notification o f such filing o f the

following: ATTORNEY GENERAL MICHAEL A. COX'S MOTION TO INTERVENE AS

A DEFENDANT IN THE COMPLAINT FILED BY PLAINTIFFS, AND IN THE CROSS

CLAIM FILED BY THE DEFENDANT UNIVERSITIES WITH BRIEF IN SUPPORT

s/Margarei A. Nelson

Margaret A. Nelson (P30342 )

Assistant Attorney General

Dept o f Attorney Genera!

Public Employment. Elections & Tort Div.

P.O- Box 30736

Lansing, MI 48909-8236

(517)373-6434

F.mail: nelsonma@michigan.gov

mailto:nelsonma@michigan.gov