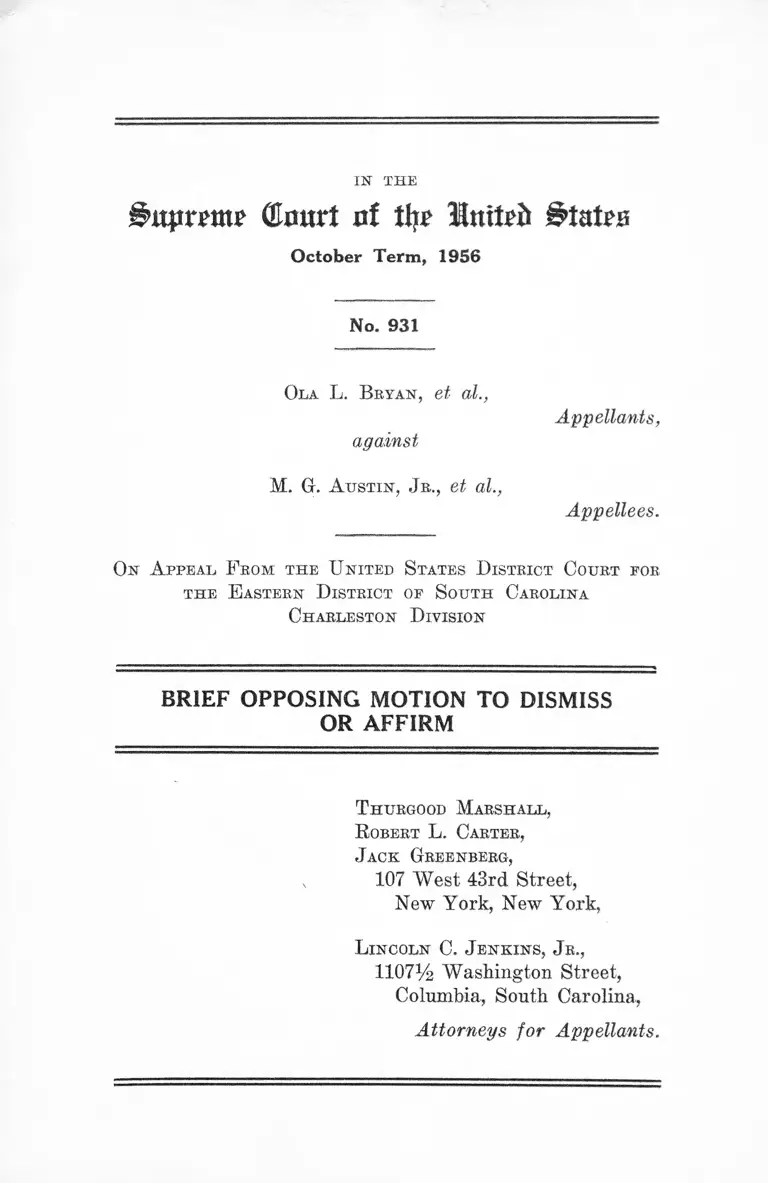

Bryan v Austin Jr Brief Opposing Motion to Dismiss or Affirm

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bryan v Austin Jr Brief Opposing Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, 1957. 24301701-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/101cc026-2600-4d4b-8343-cf67b334a4cf/bryan-v-austin-jr-brief-opposing-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

kapron* (Emirt ni % United States

October Term, 1956

IN THE

No. 931

Ola L. Bryan, et al.,

against

M. 6 . A ustin, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

Appellees.

O n A ppeal F rom the United States District Court for

the E astern D istrict of South Carolina

Charleston D ivision

BRIEF OPPOSING MOTION TO DISMISS

OR AFFIRM

Thurgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

J ack Greenberg,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.,

1101V% Washington Street,

Columbia, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellants.

IN THE

&ttpranp dtfttrt at tljp MmtTii

October Term, 19S6

No. 931

------------------ o----------------—

Ola L, Bryan, et al.,

against

Appellants,

M. G. A ustin, J r ., et al.,

Appellees.

O n A ppeal From the United States District Court for

the Eastern D istrict op South Carolina

Charleston D ivision

— ---------------------------o - — ------- -— -—

BRIEF OPPOSING MOTION TO DISMISS

OR AFFIRM

The Cause Is Not Moot.

Appellants’ Jurisdictional Statement was tiled April

22. On April 23, Act No. 741, whose constitutionality is

one of the issues in this case, was repealed by the South

Carolina Legislature. On April 24th, Governor Timmer

man signed the repealer. Appellees now contend that this

move made by one of their number (the State has appeared

herein by its Attorney General) moots the case.

But this tactic does not convert the case into one in

which this Court “ cannot affect the rights of the litigants

in the ease before it,” St. Pierre v. United States, 319 U. S.

41, 42, nor does the repeal of Act. No. 741 create a circum

stance in which “ [a] 11 possibility or threat of the [prior

2

situation] has disappeared now,” Berry v. Davis. 242 U. S.

468, 470. The threat is the same: Appellees’ answer as

serts and the record otherwise demonstrates (R. 64-68;

Motion to Dismiss or Affirm p. 2) that prior to Act No.

741 ’s adoption, as a prerequisite to employment, they

required reply to questions concerning NAACP member

ship and the applicants’ views concerning desegregation;1 *

appellees’ answer also states that following the statute’s

enactment they would have conditioned employment on

reply to such questions even had there not been a statute:

“ 13. That the inquiries contained in the employ

ment application tendered to all of the teachers in

Orangeburg School District No. 7 are similar to

those made of the teachers in the District in Sep

tember, 1955 prior to the enactment of the South

Carolina statute approved on the 17th of March,

1956. On information, advice and belief, the in

quiries contained in the employment application are

consistent with the aforesaid statute, but substan

tially the same information had been solicited prior

to the enactment of this statute and would have been

solicited of applicants had no such statute been en

acted.” (R. 15) (Emphasis supplied.)

Appellants’ prayers for relief requested not only in

junctions against the enforcement of Act No. 741, but also

against the asking of the illegal questions as a prerequi

site to employment:

“ 3. That this Court enter preliminary and final

injunctions restraining defendants from otherwise

refusing to continue the employment of plaintiffs

solely because of their membership in the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo

ple, or their attitude towards school segregation.

1 In 1955 at least some of the appellants completed such a ques

tionnaire under protest while the school term was in session (R. 64).

3

“ 4. That this Court enter preliminary and final

injunctions restraining defendants from inquiring

into plaintiffs’ beliefs and associations as a condi

tion of continued employment.

“ 5. That this Court enter preliminary and final

injunctions restraining defendants from refusing to

continue the employment of plaintiffs because they

have refused to disclose whether or not they are

members of the National Association for the Ad

vancement of Colored People or what their attitudes

may be towards the integration of the races in the

public schools.” (R. 10)

The repeal of Act No. 741 does not forbid appellees

to ask these constitutionally objectionable questions, nor

does it furnish any other relief and the relief prayed for

has not otherwise been given.

Act No. 324, 1957, the statute which repealed Act No.

741 also enacted a new prerequisite to employment by the

State which indicates that the repeal was in fact illusory:

“ Section 1. State, County, and municipal offi

cers, departments, boards and commissions, and all

school districts, in this State, shall require applica

tions in writing for employment by them, upon such

application forms as they may severally prescribe,

which shall include information as to active or hon

orary membership in or affiliation with all member

ship associations and organizations.” 2 3

3 Act No. 324’s intention is transparent and has been described

as an attempt to accomplish by another means the result sought in

Act No. 741. See The State, Section C, p. 1, April 25, 1957, Colum

bia, South Carolina.

( “ Governor S igns NAACP L egislation

“ Gov. Timmerman yesterday signed legislation repealing one

law and substituting another aimed at barring members of the

4

This statute has not been invoked in this ease and ap

pellants submit that therefore a ruling on its validity is

not essential to the disposition of the instant proceedings.

But this Court could pass upon its validity now, Abie

State Bank v. Bryan, 282 U. S. 765, 777, 781. Act No. 324

in its attempt to accomplish in veiled fashion the same

result overtly sought by Act No. 741 resembles the legis

lative maneuvers taken by South Carolina following this

Court’s decision in Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649. By

eliminating reference to race from the primary election

statutes while retaining their requirements in different

legal formulations, South Carolina hoped to thwart this

Court’s rulings. These new statutes were condemned in

Rice v. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 (4th Cir., 1947), aff’d 333

National Assn, for the Advancement of Colored People from

public employment in the state.

“ The step makes moot Federal Court action by the NAACP

against the 1956 statute.

* * * *>>)

and The State, Section A, p. 10, May 7, 1957, Columbia, South

Carolina.

( “ T rustees’ A ttention Called to L aw on M embership

L ists

“ By the Associated Press

“ The South Carolina State Department of Education is call

ing the attention of school trustees throughout the state to a

new law aimed at barring members of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People from public employ

ment— especially from teaching jobs.

lit * *

“ There is nothing in the law naming the NAACP, but the

general assembly has made it clear that members of the integra

tion-seeking organization are anathema in public jobs.

* *

5

U. S. 875 and Brown v. Baskin, 80 F. Supp. 1017, a il’d 174

F. 2d 391 (4th Cir., 1949).8

Where a change in law does not furnish relief or where

power still exists to require acts complained of this Court

has held that a case does not become moot. McOrain v.

Daugherty, 273 U. S. 135, 181-182; United States v. B,ock

Royal Cooperative, 307 U. S. 533, 555-556; F. T. C. v. Good

year Tire R. Co., 304 IT. S. 257, 260; see Groesbeck v.

Duluth S.S. & A. R. Co., 250 U. S. 607, 609; Fiswick v.

United States, 329 U. S. 211, 220-221. Indeed, in the in

stant case there is not even the temporary suspension of

power which existed in the McGrain and Rock Royal cases.

As was said in United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight

Association, 166 U. S. 290, 308-309, where a contested course

of conduct was abandoned during the litigation:

“ ‘ The defendants cannot foreclose those rights

nor prevent assertion thereof * * * ;by any such ac

tion as has been taken in this case.’ ” * * 4

8 A similar maneuver was employed by South Carolina in Clark

v. Flory, 141 F. Supp. 248 (E. D. S. C., 1956) (upon filing of com

plaint for desegregating public beach, State closed it). But compare

with Department o f Conservation and Development v. Tate, 231

F. 2d 615 (4th Cir., 1956) ; cert. den. 352 U. S. 838.

4 The elision in the quotation omits reference to the fact that

the government was the plaintiff in that case. But that the nature

of the parties is not determinative was established in Southern P.

Terminal Co. v. Interstate Commerce Comm., 219 U. S. 498, 516,

where, as in this case, the government was the defendant: “ that the

government is the respondent, not complainant, does not lessen or

change the character of the interests involved in the controversy,

or terminate its questions.”

6

Decision following such limited alteration8 in the legal

relationships of the parties is especially appropriate where

issues of great public importance are involved. McGrain v.

Daugherty, supra.

None of the cases cited by appellees are apposite, for

none deal with an unconstitutional exercise and assertion

of power anteceding and surviving a statute which but

complemented that power, and was not necessary to it:

Mills v. Green, 159 U. S. 651 concerned an election which

was concluded before judicial action could affect it; Board

of Flour Inspectors v. Glover, 160 U. S. 170, which merely

cites Mills v. Green, apparently deals with a statute, repeal

of which terminated the dispute between the parties; in

Dinsmore v. Southern Express Co., 183 U. S. 115, 120 it

was held that “ the plaintiffs do not need any relief, be

cause the act of 1901 accomplishes the result they want” ;

in Metzger Motor Car Co. v. Parrot, 233 U. S. 36 the state

court’s holding that the statute was unconstitutional ah

initio under the state constitution erased tort liability (and

this Court, following the state court reversed). In Berry

v. Davis, 242 U. S. 468, 4701 Justice Holmes rested the dis

missal on the ground that “ All possibility or threat of the

operation has disappeared now.” In United States v.

Alaska Steamship Co., 253 IT. S. 113, 116 the complainants

did “ not now need an injunction to prevent the Commis

sion from putting in force bills of lading in the form pre

sented. ” Natural Milk Producers Association v. City and

County of San Francisco, 317 U. S'. 423 was a case in which

the appellants had not challenged an exercise of power

which was effective after repeal of the ordinance assailed

at the outset.

6 Compare with United States v. United States Steel Corp., 251

U. S. 417, 445, where it was held that “ [t]here is no evidence that

the abandonment was in prophecy of or dread of suit; and the illegal

practices have not been resumed, nor is there any evidence o f an

intention to resume them, and certainly no ‘dangerous probability’

of their resumption. * * * ”

7

This ease should be heard on the appeal and jurisdic

tional statements filed heretofore by appellants. The sub

stantive questions remaining in the case are essentially

the same as when the Notice of Appeal was filed and are

“ subsidiary question[s] fairly comprised” in the question

presented in the Jurisdictional Statement (Rule 15(c)(1)).

All of the jurisdictional prerequisites have been fulfilled.

As discussed more fully in the Jurisdictional Statement,

there has been a denial of injunction by a properly con

stituted three-judge court as required by 28 U. S. C. § 1253.

“ The jurisdiction of the District Court so constituted and

of this Court upon appeal extends to every question in

volved, whether of state or federal law, and enables the

court to rest its judgment on the decision of such of the

questions as in its opinion effectively dispose of the case.”

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378, 393-394.

There Is No Reason Why Relief Should Not Be Granted.

The motion to dismiss or affirm apparently argues that

it is within the unfettered discretion of a district court

to deny application for interlocutory injunction. That the

exercise of discretion is bound by law is demonstrated in

the Jurisdictional Statement where it is shown that it is

as much an abuse of discretion to fail to exercise jurisdic

tion which is given as it is to usurp jurisdiction which

does not exist (Cohens v. Virginia, 6 Wheaton 264, 404;

United States v. Corrick, 298 U. S. 435). Moreover, the

argument is made in the motion to dismiss or affirm that

an interlocutory injunction will be given only to preserve

the status quo. That this is not so is demonstrated in

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University v.

Wilson, 340 U. S. 909, aff ’g 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La.,

1950), in which this Court affirmed a. judgment awarding

an interlocutory injunction ordering the admission of re

spondent therein to the Law School of Louisiana State

University.

8

The only consequence of Act No. 741’s repeal is that

even the illusory reasons for denial of relief have been

eliminated from the ease. There is no longer a statute

to be construed by state courts; the so-called administrative

remedy granted by the defunct statute has been repealed.

Therefore, the questions presented remain justiciable and

substantial. Nothing that has occurred herein and no argu

ment of appellees impairs appellants ’ position taken in the

Jurisdictional Statement.

Wherefore for the foregoing reasons appellees’ mo

tion to dismiss or affirm should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

T hubgood Marshall,

R obert L. Carter,

Jack Greenberg,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

L incoln C. Jenkins, Jr.,

1107% Washington Street,

Columbia, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Supreme Printing Co.. Inc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2326