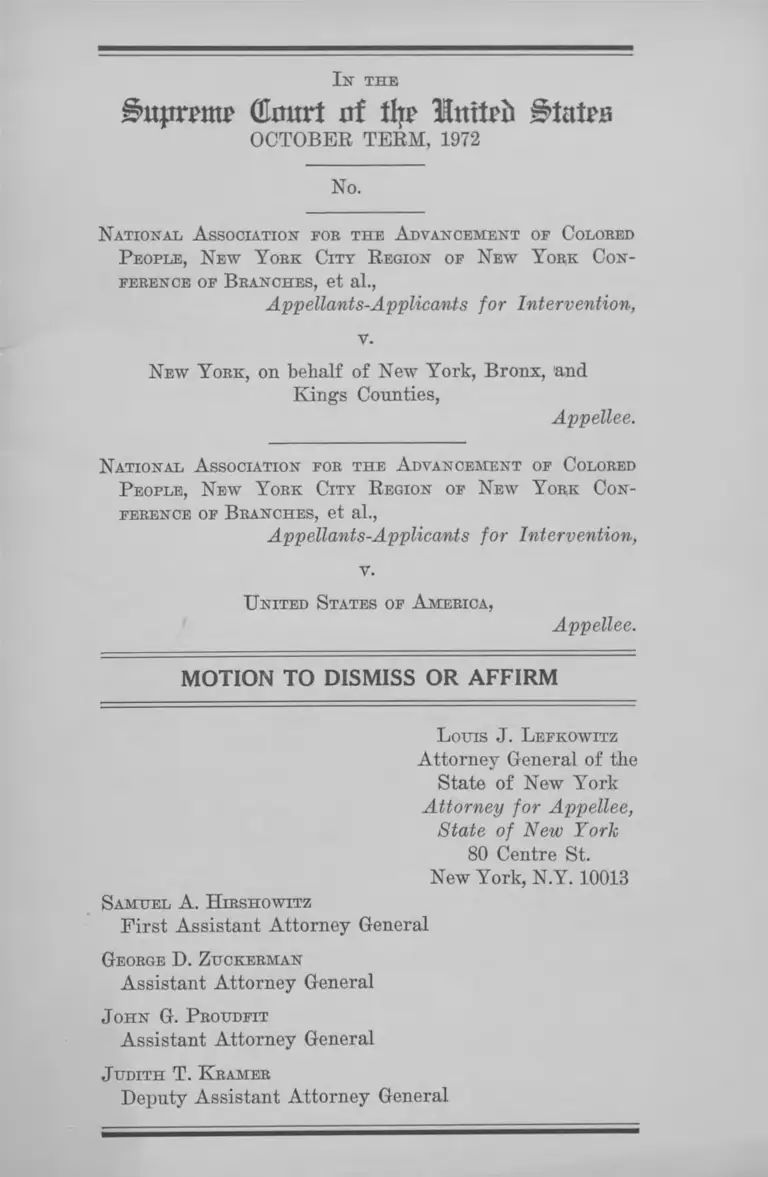

NAACP v. New York Motion to Dismiss or Affirm

Public Court Documents

August 21, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. New York Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, 1972. f3016440-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/101e4096-099a-479a-9ff3-3dd2d18fe3dd/naacp-v-new-york-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Bnpnm (Hour! nf % llmtrii t̂atra

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

In the

No.

N ational A ssociation fob the A dvancement of Colobed

P eople, N ew Y obk City R egion of New Y obk Con-

febence of B banches, et al.,

Appellants-Applicants for Intervention,

v.

New Y obk, on behalf of New York, Bronx, and

Kings Counties,

Appellee.

National A ssociation fob the A dvancement of Colobed

P eople, N ew Y obk City R egion of N ew Y obk Con-

febence of B banches, et al.,

Appellants-Applicants for Intervention,

v.

U nited States of A meeica,

Appellee.

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

Louis J. L efkowitz

Attorney General of the

State of New York

Attorney for Appellee,

State of New York

80 Centre St.

New York, N.Y. 10013

Samuel A. H ibshowitz

First Assistant Attorney General

Geobge D. Zuckebman

Assistant Attorney General

John G. Pboudfit

Assistant Attorney General

Judith T. K bameb

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

INDEX

PAGE

Statement.......................................................................... 2

Appellants have failed to establish that the Court be

low abused its discretion in denying appellants’

motion to intervene or that their appeal presents

a substantial federal question................................. 4

Conclusion ........................................................................ 12

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Allen Company v. National Cash Register Company,

322 TT.S. 137 ............................................................ 6

Apache County v. United States, 256 F. Supp. 903

(D.D.C. 1966) .......................................................... 5

Camacho v. Rogers, 199 F. Supp. 155 (S.D.N.Y. 1961) 9

Cardona v. Powers, 384 U.S. 672 ................................. 9

Gaston County v. United States, 288 F. Supp. 678

(D.D.C. 1968)............................................................ 5

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 ......................... 8

Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of Elections,

S.D.N.Y. 72 Civ. 1460 ............................................. 9

Sierra Club v. Morton, 401 U.S. 907 ........................... 6

Socialist Worker Party v. Rockefeller, 314 F. Supp.

984 (S.D.N.Y. 1970) ................................................. 9

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 3 0 1 .............. 9

n INDEX

Statutes:

page

42 USC § 1973(b) Section 4(a) of Voting Rights Act

of 1965 as amended by Public Law 91-285 .. 2, 4, 5, 7, 9

42 USC § 1973(c) Voting Rights Act of 1965 § 5 . .2, 5, 7, 9

Rule 24, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure . .............. 5, 6

New York State Constitution, Article I, § 1 .............. 2

New York Election Laws 150, 168 ......................... 2

In the

irtp m ttp Glmirt n f tltr llnxtvh States

OCTOBER TERM, 1972

--------------------♦--------------------

No.

---------------------- ♦----------------------

N ational A ssociation for the A dvancement of Colored

P eople, N ew Y ork City R egion of N ew Y ork Con

ference of B ranches, et al.,

Appellants-Applicants for Intervention,

v.

N ew Y ork, on behalf of New York, Bronx, and

Kangs Counties,

Appellee.

N ational A ssociation for the A dvancement of Colored

P eople, N ew Y ork City R egion of N ew Y ork Con

ference of B ranches, et al.,

Appellants-Applicants for Intervention,

v.

U nited States of A merica,

Appellee.

- ---------------------------------------------♦ ----------------------------------------------

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

Pursuant to Rule 16 of the Revised Rules of this Court,

appellee State of New York, on behalf of New York, Bronx

and Kings Counties, moves to dismiss or affirm on the

grounds that the questions presented by this appeal are

not justiciable and/or are so unsubstantial as not to re

quire further argument.

2

Statement

This action was commenced by the service of a complaint

by the appellee State of New York on the appellee United

States of America on December 3,1971.* The relief sought

in the complaint was for a declaratory judgment under

§4 (a ) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Public Law 89-

1101, 70 Stat. 438, 42 U.S.C. 1973(b) as amended by

Public Law 91-285, 94 Stat. 315, that during the ten preced

ing years, the voting qualifications prescribed in the laws of

New York did not deny or abridge the right to vote of any

individual on account of race or color, and that the provi

sions of §§ 4 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act were, therefore,

inapplicable in the Counties of New York, Bronx, and Kings

in the State of New York.

The aforementioned counties had come within the pur

view of the Voting Rights Act, because of a determination

made by the Bureau of Census that in 1968 less than 50%

of the persons of voting age residing in those counties had

voted in the Presidential election,** and since New York

State, during the years prior to 1970, imposed a literacy

requirement as a qualification for voting. N.Y. State

Const. Art. II, § 1; N.Y. Election Law ^ 150, 168.

On March 10, 1972 the United States filed an answer to

the amended complaint which did not deny the allegations

* An amended complaint dated December 16, 1971 was subse

quently filed.

** The percentage of the voting age population who voted for

president in 1968 was determined by the Bureau of the Census to

be 45.7% in New York County, 47.4% in Bronx County and

46.4% in Kings County. When the number of voters who partici

pated in the 1968 general election in New York but who did not

vote for the office of president is added, the percentage of voting

age population who voted in the 1968 election would be 47.7% in

New York County, 49.6% in Bronx County and 48.5% in Kings

County. Amended Compl., para. 14.

3

of said complaint except that with respect to a few specific

allegations concerning the administration of the literacy

test, the answer stated that defendant was without knowl

edge or information sufficient to form a belief.

Subsequently, on March 17, 1972, the appellee New

York moved for summary judgment. Appellees’ moving

papers included an affidavit from Winsor A. Lott, chief

of the Bureau of Elementary and Secondary Educational

Testing of the New York State Education Department

which annexed copies of all the literacy tests that were

used during the years 1961 through 1969 and which at

tested to the fact that less than 5% of the applicants who

have taken these tests have failed. It was also estab

lished that in 1968, less than 5% of the applicants who

took the literacy test in each of the three affected coun

ties failed. Amended Compl., para. 12, see also Exh. “ 1”

to the answer of the defendant United States of America.

Affidavits in support of the motion for summary judgment

were also submitted by representatives of the Boards of

Elections in each of the three affected counties attesting

to the manner in which satisfaction of literacy was estab

lished prior to 1970 when the literacy test was suspended,

and attesting to registration drives that were conducted

during the 1960’s, particularly in predominantly black and

Puerto Rican areas of New York City seeldng to encourage

minority members to register.

After a four-month investigation by attorneys from the

Department of Justice which included an examination of

registration records of selected persons in New York,

Bronx and Kings Counties, interviews with election and

registration officials and interviews with persons familiar

with registration activity in black and Puerto Rican

neighborhoods in those counties (Juris. State., p. 8a), an

affidavit was filed on April 4, 1972 by David L. Norman,

Assistant Attorney General in charge of the Civil Rights

Division. The Norman affidavit stated that on the basis

of that investigation conducted by the Department of

4

Justice “ there was no reason to believe that a literacy

test has been used in the past 10 years in the counties of

New York, Kings and Bronx with the purpose or effect

of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of

race or color, except for isolated instances which have

been substantially corrected and which, under present

practice cannot reoccur.” Accordingly, the United States

consented to the entry of the declaratory judgment.

Although the nature of this action was public knowledge

shortly after it was filed with the Department of Justice

(an article concerning the nature of the action appeared

in the New York Times on February 6, 1972), appellees

did not move to intervene as defendants in this action

until April 7, 1972. On April 11, 1972 appellee New York

filed an affidavit and memorandum in opposition to the

motion to intervene. On April 13, 1972 the three-judge

federal court denied without opinion appellant’s motion

to intervene and granted appellee New York’s motion for

summary judgment.

On April 24, 1972 appellants moved to alter the prior

judgment. The motion was denied on April 25, 1972.

Thereafter appellants filed a notice of appeal with this

Court with respect to the order denying this application

to intervene on April 13, 1972 and the order denying

their motion to alter judgment.

APPELLANTS HAVE FAILED TO ESTABLISH

THAT THE COURT BELOW ABUSED ITS DIS

CRETION IN DENYING APPELLANTS’ MO

TION TO INTERVENE OR THAT THEIR

APPEAL PRESENTS A SUBSTANTIAL FED

ERAL QUESTION

Section 4(a) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and as

amended by the Voting Rights Act of 1970 provides a state

or subdivision with the right to request declaratory judg

5

ment so that it may be exempted from the compliance re

quirements of § 5. See cases cited in Gaston County v.

United States, 288 F. Supp. 678, 679 n. 1 (D.D.C. 1968).

The determination as to whether the test or device, which

triggered the applicability of § 4, has been used to deny

or abridge an individual’s right to vote on account of race

or color rests with the United States District Court, al

though the United States Attorney General may consent

to the entry of such a judgment.

The Voting Rights Act “makes no express provision

for intervention” , but “ rather contemplates that the At

torney General will protect the public interest in defend

ing section 4(a) actions.” Apache County v. United States,

256 F. Supp. 903, 906 (D.D.C. 1966). While there is no

statutory or absolute right to intervene in ^4(a) actions,

the district courts have recognized the right of private

parties to seek permissive intervention pursuant to FRCP

Rule 24(a)(2) where the requirements of that section have

been satisfied and where the applicant for intervention

can establish that the Attorney General has been derelict

or deficient in protecting the public interest. But “ such

intervention is not to be permitted except upon a strong

showing.” Apache County v. United States, supra, at 908.

Upon the record before it, the District Court had no

choice other than to deny appellants’ motion for inter

vention where (1) appellants did not establish that they

had standing, (2) the motion was not timely and would

have seriously disrupted New York’s electoral processes,

(3) appellants have other adequate legal means of pro

tecting their interests, and (4) where appellants failed

to establish that the Justice Department had not ade

quately protected the public interest or (5) that New York’s

literacy test had denied any individual the right to vote

on account of race or color.

6

Every one of the named individual appellants were and

are duly registered voters in the State of New York. Ap

pellants’ papers submitted to the District Court fail to

establish how any of these individuals would be directly

injured by the entry of the declaratory judgment in this

action.

Since appellants are assuming that they have the same

rights as the original parties in this action, they must be

held to the same standards in determining whether they

have proper standing. “ Mere concern without a more

direct interest cannot constitute standing in the legal

sense” sufficient to challenge the exercise of responsibility

of the Justice Department in this action. Sierra Club v.

Morton, 401 U.S. 907.

(2)

Although the institution of this action was public knowl

edge since the filing of a complaint on December 3, 1971

and was mentioned in prominent newspaper articles (see

New York Times, Feb. 6, 1972), appellants did not move

to intervene until April 7, 1972. Appellants’ contention

that it waited until the Justice Department’s defense was

completed before seeking to intervene is a patently base

less excuse for delay. I f such a contention were to be sus

tained, it would require a plaintiff to win two separate

rounds in every lawsuit: first against the named defend

ant, and secondly against the intervenors who were watch

ing from the sidelines until the defense’s case was com

pleted.

In determining whether to exercise its discretion to per

mit intervention, a district court must also consider

“ whether the intervention will unduly delay or prejudice

the adjudication of the rights of the original parties.”

FRCP Rule 24 (b ); see Allen Company v. National Cash

Register Company, 322 U.S. 137.

(1)

7

The granting of appellants’ motion to intervene at the

time it was brought would have seriously disrupted New

York’s electoral process. A legislative redistricting

statute providing for new assembly and senate districts

in the State of New York based on 1970 census figures

was enacted in January, 1972 and new congressional dis

tricts were provided by a statute enacted in March, 1972.*

The State of New York was aware of the fact that a

detailed Justice Department investigation into the con

sequences of each of the new assembly, senate and con

gressional lines in three large counties within New York

City might require several months to complete which would

have prevented the use of the new district lines in the

Spring, 1972 primary elections. Since there was no ques

tion that the filing requirements of $ 5 of the Voting Rights

Act were due to the statistical presumptions imposed by

§4 rather than by any evidence that New York’s literacy

test had discriminated against any individual by reason

of race or color, the present lawsuit was instituted to

prevent any delay in having the legislative and congres

sional districts at stake in the 1972 elections governed

by 1970 census figures.

The delay sought by appellants’ belated intervention

would have unquestionably resulted in the holding of

primary and general elections in New York State based

on population figures that were 12 years out of date.

( 3)

The denial by the District Court of appellants’ motion

for intervention has not prevented them from their pur

portedly ultimate objective of protecting the voting rights

of black citizens. I f they believe that any of the new

* Correct 1970 census figures for the State of New York were

not supplied to the New York Joint Legislative Committee on Re

apportionment by the United States Bureau of the Census until

October 15, 1971.

8

assembly, senate or congressional district lines were the

product of racial discrimination and violative of the

Fourteenth and/or Fifteenth Amendments they may seek

remedial relief in a civil rights action in one of the federal

district courts in the State of New York. Cf. Gomillion v.

Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339. Indeed, there is no reason why

appellants could not have amended their present action in

the Southern District of New York (NAACP v. New York

City Board of Elections, 72 Civ. 1460) to seek such relief

unless their reluctance to do so results from a lack of

evidence to support such charges.

(4 )

Appellants have failed to sustain their heavy burden of

proof of showing that the Justice Department was

derelict or deficient in protecting the public interest in its

defense of this action. Cf. Apache County v. United States,

supra.

The Justice Department conducted a four-month investi

gation into the allegations of the complaint before con

senting to the entry of a declaratory judgment. As noted

in the affidavit of the Assistant Attorney General in charge

of the Civil Rights Division (Juris. State. 8a-lla),

attorneys from the Department of Justice examined regis

tration records of selected persons in each covered county,

conducted interviews with election and registration officials

and interviews with persons familiar with registration

activity in black and Puerto Rican neighborhoods in those

counties. In answer to the Justice Department’s request,

the Board of Elections supplied the Department with

selected election districts in each of the three affected

counties that were predominantly white, predominantly

black, predominantly Puerto Rican and districts that

contained mixed populations. The Justice Department was

unable to uncover any evidence that would indicate that

the predominantly black or Puerto Rican districts suffered

9

as a result of the imposition of English language literacy

tests or were treated any differently than predominantly

white election districts.

If appellants were in possession of any evidence that

individuals were subjected to discrimination by reason of

their race or color in the conduct of the literacy tests,

they could have presented such evidence to the Justice

Department. None of appellants’ papers indicate that

they are in possession of such evidence.

(5 )

Certainly, the mere fact that New York imposed an

English literacy requirement cannot be cited as evidence

of racial discrimination. The right of a state to impose

an English literacy requirement has been sustained by

this Court. Lassiter v. Northampton County Board of

Elections, 360 U.S. 45. Although New York’s literacy re

quirements may no longer be enforced to the extent that

they are inconsistent with 42 USC $ 1973(b)(c), courts

have refused to declare that New York’s literacy require

ments constituted a denial of equal protection. Camacho

v. Rogers, 199 F. Supp. 155 (S.D.N.Y. 1961); Socialist

Worker Party v. Rockefeller, 314 F. Supp. 984, 999

(S.D.N.Y., 1970); Cardona v. Power, 384 U.S. 672.

It may be remembered that when South Carolina at

tacked the constitutionality of the 1965 Voting Bights Act

on the grounds that § 4 actions would place an impossible

burden of proof upon states and political subdivisions,

this Court noted that the Attorney General had pointed

out during hearings on the Act that “ an area need do no

more than submit affidavits from voting officials, asserting

that they have not been guilty of racial discrimination

through the use of tests and devices during the past five

years, and then refute whatever evidence to the contrary

may be adduced by the Federal Government.” South

Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 332.

10

The State of New York clearly met its burden entitling

it to a declaratory judgment.

The affidavit of Winsor A. Lott, which contains copies

of all literacy tests that were given by the State of New

York from 1961 to 1969 shows that the literacy tests con

sisted of a short paragraph in simple English followed by

eight questions which could be answered in one or a few

words. The answers were found in the paragraph. No

outside knowledge was required. The tests were distrib

uted with corresponding answer keys geared to minimize

the discretion of the graders. Anyone with a minimal

amount of English comprehension should have been able

to pass the test. The evidence established that over 95%

of the applicants each year who took the literacy test

passed it throughout the State and in each of the three

affected counties.

The failure of any person to register and vote in the

Counties of New York, Bronx and Kings is and was in

no way related to any purpose or intent on the part of

the officials of those counties or the State of New York

to deny or abridge the right of any person to vote on

account of race or color.

Indeed, the named counties have in the past actively

encouraged the full participation by all of its citizens in

the affairs of government.

Central registration takes place throughout the year at

the Board of Elections. Local registrations are also con

ducted every October for a three or four day period. In

each county in New York City and in each election district

in each county are polling places designated for local reg

istration. See affidavit of Alexander Bassett, sworn to

March 16, 1972, p. 3.

To further expand the number of registrants in New

York, since 1966, if the prospective registrant demonstrated

11

by certificate, diploma or affidavit that be had completed

the sixth grade in a public school in, or private school

accredited by any State of the Commonwealth of Puerto

Bico, in which the pre-administrative language was Span

ish, he was permitted to register without proof of literacy

in English. July 28, 1966, Op. Atty. Gen., 121. The At

torney General of New York set forth guidelines recom

mending that the affidavits be printed in English and

Spanish to avoid language difficulties. In 1967, this became

the practice (See affidavit of Bassett, supra, p. 2).

Moreover, beginning in 1964, New York City embarked

upon an intensive effort to gather new voters at consid

erable expense. Every year since, except 1967, the Board

of Elections has sponsored summer registration drives to

encourage more people to register. In 1964, registrations

were conducted in local firehouses throughout the City

(Affidavit of Beatrice Berger, sworn to March 17, 1972). In

1965, mobile units were sent out into very populated areas

containing a high density of blacks. Thereafter, local

branches of the Board of Elections were set up throughout

the City. These branches were specifically set up also in

areas with a high population of black residents. With

each new voter registration drive came a waive of pub

licity in the news media requesting citizens to register

(Berger affidavit, p. 2).

Thus, far from discriminating against new voters by

reason of race or color, the State of New York has actively

sought to encourage members of minority groups to regis

ter and vote.

12

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the within motion to dis

miss or affirm should be granted.

Dated: New York, New York, August 21, 1972.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis J. L eekowitz

Attorney General of the

State of New York

Attorney for Appellee,

State of New York

Samuel A. H irshowitz

First Assistant Attorney General

George D. Z uckerman

Assistant Attorney General

John G. Proudfit

Assistant Attorney General

J udith T. K ramer

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

(52103)