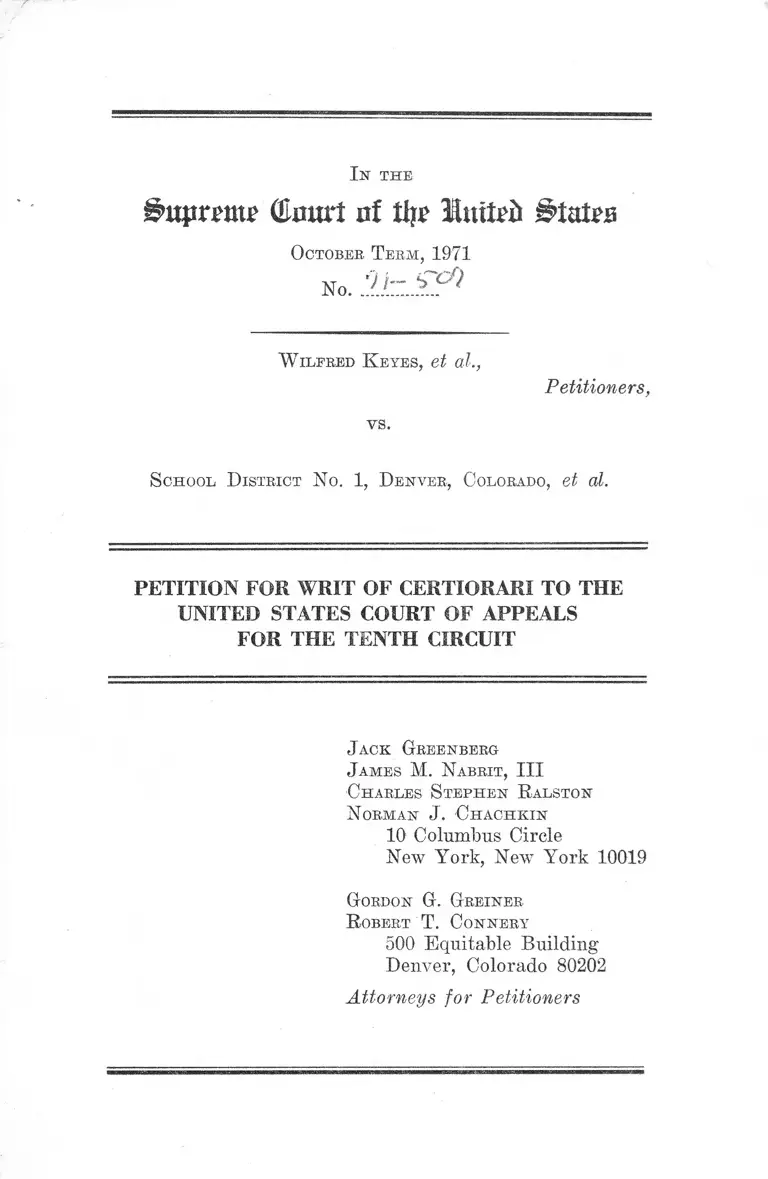

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1971. a9a341f9-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1045d357-2415-4c82-a799-33ee995c45aa/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(ta r t nf % Imteii

O ctober T e r m , 1971

No. I t

W ilfred K ey es , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

S chool D istrict N o. 1, D en v er , C olorado, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J a m es M. N a brit , I I I

C harles S t e p h e n R alston

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

G ordon G. Gr e in e r

R obert T . C o nnery

500 Equitable Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions Below.............................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved...... 2

Question Presented ....................................... 2

Statement of the Case ................................................. 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve Con

flicts in Principle Among the Lower Courts .... 14

II. Other Inequalities in the System, Coupled with

Racial Segregation, Provide Further Reason

for Requiring the Only Workable Remedy:

Racial Integration ...................... 22

Conclusion ...................................................................... 26

T able op A ttthobities

Cases

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953) ..................... 5n

Bell v. School City of Gary, 324 F.2d 209 (7th Cir.

1963), cert. den. 377 U.S. 924 (1964) .....................15,15n

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970), 438

F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971), Civ. No. 35257 (E.D. Mich.,

Sept. 27, 1971) ........ ............................................ ..14,

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103

(1965)

PAGE

20

IX

Brewer v. School Board of Norfolk, Va., 397 F.2d 37

(4th Cir. 1968) .......................................................... 18

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 20

Calhoun v. Cook, Civ. No. 6298 (N.D. Ga., July 28,

1971) ....................................................................... 16n, 18

Chandler v. Ziegler, 88 Colo. 1 (1930) ......................... 5n

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 288 F.2d

853 (6th Cir.), cert. den. 350 U.S. 1006 (1956) .......... 14

Davis v. Board of School Commr’s of Mobile, 402 U.S.

33 (1971) .................................................................. 17n

Davis v. School District of City of Pontiac, 309 F.

Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970), aff’d 443 F.2d 573 (6th

Cir. 1971) ........................................................14,17,18,21

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), cert. den. 389 U.S. 847 (1967) ...... 15

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ....... . 20

Downs v. Board of Educ. of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988

(10th Cir. 1964), cert, den., 380 U.S. 914 (1965) ....13,15,

15n

PAGE

Gomperts v. Chase, —— U.S. ----- , No. A-245 (Sept.

10, 1971) ..................................................................14, 25n

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Va., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) .......................................15n, 21

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir.

1971) (reh. en banc granted) ................................... 20

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D.C. 1967),

aff’d sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C.

Cir. 1969) ................................................................... 25n

Jackson v. Goodwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1969) .... 20

Ill

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School Dist., Civ.

No. C-70-1331 SAW (N.D. Cal., July 9, 1971), stay

denied sub nom. Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, -----

U .S.----- , No. A-203 (Aug. 25, 1971) ....................... 14

Kennedy Park Homes Assn., Inc. v. City of Lacka

wanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970), cert, den., 401

U.S. 1010 (1971) .......... ......................................... . 20

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 396 U.S. 1215

(1969) ......................................................................... 4n

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, No. 30154

(5th Cir., June 29, 1971) ............................................ 20

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) .....................20, 25n

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hills

borough County, Civ. No. 3554-T (M.D. Fla., May

11, 1971) ......... ........................................................ 16n, 21

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, Civ. No. 3564

(E.D. Tenn., July 26, 1971) .... .............. ................... 16n

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1963) .............. 25n

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of Regents, 339

U.S. 637 (I960) ......................................................... 25

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 360 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

371 U.S. 828 (1962) ........................... ........................ 21

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) 25

Oliver v. Kalamazoo Board of Education, No. K88-71

(W.D. Mich., Aug. 19, 1971) (oral opinion) aff’d

No. 71-1700 (6th Cir., Aug. 30, 1971) ..................... 15

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ........ ................... 21

Serrano v. Priest, No. L.A. 29820 (Supreme Ct. Cal.,

Aug. .30, 1971) ............................................................ 25n

PAGE

IV

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948) ........................ 5n

Sipuel v. Univ. of Okla. Board of Regents, 332 U.S.

631 (1948) .................................................................. 25

Soria v. Oxnard School District, 328 F. Supp. 155 (C.D.

Cal. 1971) .................................................................... 15

Spangler v. Pasadena City Board of Educ., 311 F.

Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970) ...................................... 14

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Educ., 318 F.2d

425 (5th Cir. 1963), 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1.964) ...... 24n

Steward v. Cronan, 105 Colo. 393 (1940) ..................... 5n

Stout v. Jefferson County Board of Education, No.

29886 and 30387 (5th Cir., July 16, 1971) .............. 20

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971) .....................................14n, 15n, 16n, 18, 20

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) ........................ 25

Taylor v. Board of Education of New Rochelle, 191

F. Supp. 181 (S.D. N.Y.), appeal dismissed, 288 F.2d

600 (2d Cir.), 195 F. Supp. 231 (S.D. N.Y.), aff’d

294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 940

(1961) .....-................................................................. 14,18

United States v. Board of Educ., Tulsa, 429 F.2d 1253

(10th Cir. 1970) ................................................... 15n, 18n

United States v. Board of School Comm’rs of In

dianapolis, Civ. No. IP-68-C-225 (S.D. Ind., Aug.

18, 1971) ............................................................ 15,15n, 19

United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp.

786 (N.D. 111. 1967), aff’d 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir.

1968), on remand, 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969),

aff’d 432 F.2d 1147 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, den., 402

U.S. 943 (1971) .......................................................18,21

PAGE

V

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, No. 70-188,

O.T. 1970 .................................................................... 20

Federal Statutes

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) ..............................,........................ 3

28 U.S.C. §1343(4) ....................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. §1983 ............................................................ 3

Other Authorities

Coleman, Equality of Educational Opportunity (1966) 21n

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A Report of the

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1967) ................. 21n

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (1968) ....................................................... 21n

PAGE

I n th e

(tatrt of % WmUb States

O ctober T e r m , 1971

No...... ..........

W ilfr ed K ey es , et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

S chool D istr ic t No. 1, D en v er , C olorado, et al.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit entered in

this matter on June 11, 1971. /

Opinions Below

The June 11,1971 opinion of the Court of Appeals, whose

judgment is herein sought to be reviewed, is reported at 445

F.2d 990 and is reprinted in the separate Appendix to this

Petition, pp. 122a-158a. The prior opinions of the United

States District Court for the District of Colorado, also

reprinted in the Appendix, are reported as follows: (1)

July 31, 1969, granting petitioners’ motion for preliminary

injunction, 303 F. Supp. 279 (Appendix, pp. la-19a); (2)

August 14, 1969, on remand to make preliminary injunction

more specific and consider applicability of portion of Civil

2

Rights Act of 1964, 303 F. Supp. 289 (Appendix, pp. 20a-

43a); (3) March 21,1970, opinion on merits granting perma

nent injunction, 313 F. Supp. 61 (Appendix, pp. 44a-98a);

and (4) May 21, 1970, opinion on relief or remedy, 313

F. Supp. 90 (Appendix, pp. 99a-121a).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered June

11, 1971. On September 8, 1971, Mr. Justice Marshall en

tered an order extending the time for the filing of this

petition to and including October 9, 1971. The jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which

provides as follows:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of

the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the

United States; nor shall any State deprive any person

of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law;

nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws.

Question Presented

Whether school authorities who have over several decades

created and aggravated school segregation and minimized

school integration, and whose policies and practices system

atically afford white students greater educational oppor

3

tunities than black or Spanish-surnamed students attend

ing segregated schools, must take all possible affirmative

steps to eliminate segregation throughout their school sys

tem and otherwise equalize educational opportunity.

Statement of the Case

This is a school desegregation action brought by Denver

Schoolchildren and their parents on June 19, 1969 pursuant

to 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and (4). While

the litigation followed a newly elected school board’s can

cellation of a partial desegregation plan adopted by the

predecessor board, the complaint sought the complete de

segregation of the Denver public school system and provi

sion of equal educational opportunities to all Denver

schoolchildren.1

T he D enver School District

The respondent school district is coterminus with the

City and County of Denver, Colorado. During the 1968-69

school year—immediately preceding this lawsuit and prior

to implementation of the preliminary injunction (303 F.

Supp. 279, 289)-—the school district operated 118 schools2 *

serving 96,577 children. Denver students include significant

1 Petitioners’ Complaint alleged, inter alia (First Count, Second

Cause of Action) (emphasis supplied) :

B. By the following described acts, among others, defendants

and/or their predecessors have over the years and are at

present deliberately and purposefully attempting to create,

foster and maintain racial and ethnic segregation within

the School D istrict; . . .

C. These various actions of said defendants have effected in

the School District a significant segregation of pupils by

race and ethnicity. . . .

2 Nine senior high schools, 17 junior high schools and 92 ele

mentary schools.

4

numbers of Negro (12.0-15.2%) and Spanish-surnamed

(15.2-23.1%) children.3

During the 1968-69 school year (prior to this suit) there

was substantial segregation of students in the Denver pub

lic schools, as shown by the following table:

Students White Black

Spanish-

surnamed

Attending Students Students Students

Schools: No. % No. % No. %

0-25.0% white 1778 2.8% 10110 74.2% 6174 31.6%

25.1-50.0% white 2931 4.6% 797 5.8% 3885 19.9%

50.1-75.0% white 12075 19.0% 1848 13.6% 5469 28.0%

75.1-100% white 46635 73.5% 877 6.4% 4001 20.5%

63419 13632 /v 19529 '2*

T he Evidencet

This pattern of segregated schooling had persisted for a

considerable time in Denver.4 Much of the evidence demon-

3 The following table shows the distribution of Denver school-

children by race and grade level:

White £<. 4 Negro •' • ' Spanish-

surnamed*

No. % No. % No. %

Sr. High (10-12) 14,852 72.8 2,442 12.0 3,091 15.2

Jr. High (7-9) 14,855 68.8 2,893 13.4 3,858 17.8

Elementary (K-6) 33,678 61.7 8,304 15.2 12,594 23.1

* Statistics include children of “Other” races in this category;

such children constitute 1 % of total student enrollment in

school district.

4 Perception of the problem led previous school boards to appoint

two committees to recommend solutions, see n. 8 infra, and to adopt

the plan to desegregate several Denver schools which was annulled

by the new board on June 9,1969 and then reinstated by the district

court’s preliminary injunction. The district court’s order was itself

vacated by the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

and subsequently reinstated by order of Mr. Justice Brennan. See

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969).

5

strated Denver’s use of the now familiar galaxy of tech

niques by which boards and administrators have sought to

preserve school segregation.

Prior to 1950, almost every secondary school and several

elementary schools in Denver had “mandatory” attendance

zones immediately surrounding them and larger “optional

zones” between them; students living in an “optional zone”

were permitted to attend either school serving it (PX 20

at p. A-12).| While there are no records in evidence show

ing the use made of this device prior to 1950, thereafter it

caused continued attendance of minority-race students at

predominantly minority-race schools and avoidance of such

schools by white students (H. 63, 78, 112-14; PX 401, 406).

Before 1950, the black and Spanish-surnamed population

of Denver generally occupied older portions of the central

city.* 6 Negroes were concentrated in a well-defined area sur

rounding the “Five Points,” 303 F. Supp. at 282, Appendix

at p. 4a. Most of the public schools located within this area

were predominantly, if not completely, Negro. Ibid.

Virtually all of the city’s Negro high school students at

tended Manual High School although their numbers were

small enough that the high school was not majority-black;

the school also enrolled many Spanish-surnamed students

but at that time was the only high school in the Denver

6 Citations to the transcript of tile hearing on preliminary in

junction held in July, 1969 will be given as “P.H. ——.” Citations

to the transcript of the February, 1970 hearing on the merits will

be given as “H. ——.” Citations to the transcript of the May, 1970

hearing on relief will be given as “R.H. ----- .” Exhibits will be

identified by reference to the party below introducing them; i.e.,

“P X -----and “DX —— ” for plaintiffs’ and defendants’ exhibits,

respectively.

6 Prior to this Court’s decisions in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1

(1948) and Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 (1953), Colorado

courts enforced racially restrictive covenants. E.g., Chandler v.

Ziegler, 88 Colo. 1 (1930) ; Stewards. Cronan, 105 Colo. 393 (1940).

6

school system with a minority of white students (H. 78,

PX 401).

At the same time and until at least 1964, it was the policy

xof the Denver school authorities to assign black and Spanish-

surnamed teachers to the schools in which black and Spanish-

surnamed students were concentrated.7 The result was that

while no school had a majority of black or Spanish-surnamed

teachers, almost all of these teachers were concentrated

in a few schools, while most schools had no minority-race

teachers (H. 2011-14). This concentration in fact continued

through the 1968-69 school year just prior to the institution

of this suit (PX 254, 256, 258).

Following 1950, Denver’s population increased markedly.

Undeveloped areas were settled and new territory added to

the city by a larg’e number of annexations. Schools were

constructed in these areas; they opened as and have re

mained virtually entirely white. Both the Spanish-surnamed

and black communities expanded, the latter along a narrow

corridor eastward from the “Five Points” area. 303 F. Supp.

at 282, Appendix at p. 4a.

Respondents’ school construction policies traced these

patterns and accelerated the isolation of students into ra

cially identifiable schools: In 1953 the system replaced

Manual High School'—already minority-white and enroll

ing almost all of the city’s Negro high school students—

with a new facility located two blocks away, serving the

7 The school district defended this policy, despite its segregation

of school faculties, on the ground that it furnished successful “role

models” for minority race students to emulate (H. 2013-14). The

district court found, however, that the system’s faculty assignment

policies were generated by a fear that the white community would

not accept the placement of minority-race teachers in white schools,

303 P. Supp. at 284, Appendix at p. 9a-10a. On appeal, the Tenth

Circuit ignored this finding and instead accepted the school dis

trict’s justification. 445 F.2d at 1007, Appendix at p. 150a.

7

same mandatory attendance area and limited in size to serve

only the black and Spanish-surnamed students in that area

or anticipated to be added thereto by population growth

(H. 78, 296; PX 401). In 1960 the Barrett Elementary

School was built in a black neighborhood at the extreme

eastern edge of the Negro residential area but its size was

restricted and its boundaries manipulated—its easternmost

boundary ran along its playground—to conform to existing

residential patterns and insure that it would be a black

school from its opening (303 F. Supp. at 282; Appendix at

p. 5a). The Manual and Barrett sites were selected and

constructed over the opposition of representatives of the

black community.8

Changes in attendance areas of Denver public schools,

for the ostensible purpose of relieving overcrowding at

various schools, also resulted in maintaining or exacerbat

ing segregations: In 1952, optional areas were instituted

between an overcrowded, increasingly black elementary

school (Columbine) and adjacent, underutilized, totally

white facilities (Harrington and Stedman)—relieving the

overcrowding slightly by permitting the white students at

Columbine to withdraw (H. 106-07, 112-14; PX 406). In

1956 overcrowding at East High necessitated adding part

of the Manual-East optional area to the mandatory zone for

a still-under-capacity Manual. However, the change in

8 Similar opposition to the announced 1962 plan to build a junior

high school at the Barrett site, in fact, led to the appointment of

the first of two committees to investigate “the present status of

educational opportunity in the Denver Public Schools, with atten

tion to racial and ethnic factors. . . . ” That committee, reporting

in 1964, “criticized the Board’s establishing of school boundaries

so as to perpetuate the existing de facto segregation ‘and its re

sultant inequality in the educational opportunity offered’.” 303 P.

Supp. at 283, Appendix at p. 6a. The second group made its report

in 1967 and “noticed the intensified segregation in the northeast

schools and recommended that there be no more schools constructed

in northwest Denver.” Ibid.

8

corporated only the established black residential portion

of the optional area (H. 291, 296) although enlarging the

Manual High zone still more would have better utilized

both schools’ capacity, made better use of public trans

portation lines (which ran directly from the remaining

optional area to Manual) and also resulted in desegregation

(H. 281-86). A change similar in operation and effect was

made the same year between the two feeder junior high

schools for Manual and East: Cole (black)8 9 and Smiley

(white), respectively. Both proposals were resisted before

the school board by representatives of the black community

because they would segregate.10 Similarly, in 1962 and

1964, boundary changes for Stedman Elementary School

(where Negro enrollment was increasing) were made, pur

portedly to relieve overcrowding. But only predominantly

white areas of the Stedman zone were shifted to white

schools; alternative rezoning plans which would both have

avoided concentration of black students at Stedman as well

as have relieved its capacity problem were rejected (303

F. Supp. at 285, Appendix at p. 11a). Finally, Boulevard

Elementary School was turned into a school enrolling a

majority of Spanish-surnamed students in 1961 when, in

8 As in the case of Manual, Cole enrolled almost all of the school

system’s black junior high school students at this time.

10 The school district had previously constructed an addition to

relieve overcrowding at Smiley in 1952 rather than adjust its

boundary with Cole, which was then underutilized (PX 215, 215A).

The same thing occurred in 1958 when Smiley was again enlarged

(PX 215).

Overcrowding at East High School was relieved by the construc

tion of a new George Washington High School in 1960, while

Manual remained underutilized (PX 210). The new George Wash

ington High attendance boundaries took only whites from East

(PH 547-49; PX 20, Map No. 7). In 1964 the adjustment in the

East-George Washington boundary, supposedly made to create a

more heterogeneous school population at George Washington (PH

547-49), took 200 white students and only 9 black students from

East (PX 585-86).

9

response to a decrease in capacity caused by the demolition

of an older section of the facility, a white portion of its

attendance area was transferred to the adjacent and over

whelmingly white Brown Elementary School (H. 115-26).

There were also boundary alterations apparently un

related to any pressing capacity problems. For example, in

1962 all optional zones surrounding Morey Junior High

School were eliminated. White portions of the former op

tional zones between Morey and Byers, to its south,11 were

added to the Byers zone; black areas between Cole12 or

Baker13 (to the north) and Morey were added to Morey,

resulting in the immediate transformation of the school

enrollment from majority- to minority-white (313 F. Supp.

at 71-72, Appendix at pp. 63a-64a). Similarly, Anglo areas

were transferred from Hallett to Phillips in 1962 and 1964;

in the latter year, this was accompanied by the transfer of

a black area from Stedman to Hallett (PX 75, 76). Again,

the effect was to accelerate and emphasize the rapid trans

formation of Hallett into a racially isolated minority school.

When Denver first utilized mobile classrooms in 1964,

28 of 29 such portable buildings were located in the increas

ingly black Park Hill area,14 * where they effectively con

tained an expanding black population (303 F. Supp. at 285;

Appendix at p. 11a). At the same time, overcrowding in

other (but predominantly white) schools in Denver was

met by school board transportation of students—sometimes

11 At this time Byers was an all-white junior high school while

Morey, prior to the changes discussed in text, was predominantly

white.

12 See n. 9 supra.

13 Baker was predominantly white but with a significant minority-

race enrollment.

14 The remaining portable was placed at a school attended by a

majority of Spanish-surnamed students (PX 101).

10

across the width of the school district—to other (white)

schools where capacity -was available (P.H. 540-41)16 despite

somewhat closer available capacity at (predominantly

minority) schools in the central or core city (P.H. 544).

The school district’s excuse for busing* whites to only white

schools was its desire to maintain low pupil-teacher ratios

at minority schools in order to offer compensatory pro

grams; its explanation for the creation of extra capacity

for black students in black Park Hill schools by the addi

tion of portables was that black parents surveyed at the

time preferred it to one-way busing back to the core city

area (H. 479-81).

Finally, when in 1964 the district eliminated all optional

attendance zones (in accordance with the recommendation

of the committee investigating educational opportunity for

minority students, see n.8 supra, which found that optional

areas intensified segregation), it substituted a “limited open

enrollment” policy. The only limit of this policy was the

availability of space in the various schools; it was the

equivalent of free choice and under it Denver permitted

wholesale minority-to-majority transfers until it was finally

repealed in 1969! (H. 126-32; PX 99, 100).

The result was a school system marked by intense racial

and ethnic separation.16 The proof also demonstrated to the

satisfaction of the district court that the Denver public

schools were also systematically disadvantaging their black

16 Much of the overcrowding was due to annexations of additional

areas contiguous to existing schools. But, even after new schools

were constructed in the annexed territory, the space in the former

receiving schools was not used to accommodate—and integrate—

the overcrowding in the Park Hill schools. Thus, whereas prior

to the construction of the Traylor Elementary School, some 400

white students were bused across the district to the University

Park School, after Traylor w*as completed, only 36 Park Hill stu

dents were transferred to University Park (PH. 543).

16 Cf. p. 4 supra.

11

and Spanish-surnamed students educationally. Most of

these students attended all- or predominantly minority

schools which lacked various tangible measures of educa

tional quality. The facilities themselves were generally

among the oldest and smallest in the district, the faculty

generally had less teaching experience in the system than

faculties at white schools, and the faculty turnover rates

at these schools were highest (303 F. Supp. at 284-85; 313

F. Supp. at 79-80; Appendix at pp. 9a-10a; 80a-81a). At the

same time, various objective measures of educational attain

ment indicated that the students in these schools were

suffering: they had higher dropout rates and consistently

(and drastically) lower mean achievement test scores than

other schools. Finally, expert testimony offered by plain

tiffs explained these results not just in terms of the tangible

differences among the schools, but the intangible effects of

school board policies—-such as the concentration of the less-

experienced minority-race teachers in these schools—as

well: low pupil and teacher morale, feelings of isolation

and inferiority affecting motivation, etc.

T he R ulings Below

The district court ruled, 303 F. Supp. 279, 289, Appendix,

pp. la, 20a, that the respondents had acted unconstitu

tionally in cancelling their prior desegregation plan, and

that schools in the northeast Denver (Park Hill) area which

would have been affected by the plan were segregated be

cause of the school district’s “segregation policy.” The

court, therefore, preliminarily enjoined respondents to im

plement the terms of their original plan, as originally

scheduled, commencing with the 1969-70 school year.17’18

17 However, the district court stated explicitly that the school

board could still adopt and implement another plan “embodying

the underlying principles” of the withdrawn plan, if it so desired.

18 See n. 4 supra.

12

These findings were carried forward in the district court’s

opinion on permanent relief, 313 F. Supp. 61, Appendix,

p. 44a. However, as to other Denver schools, the district

court ruled that there had been no sufficient showing of a

segregation policy, although the court admitted that “[a]s

to these schools, the result is about the same as it would

have been had the administration pursued discriminatory

policies. . . . ” 313 F. Supp. at 73; Appendix at pp. 66a-67a

(emphasis supplied). The same practices regarding school

construction, boundary changes, additions to existing

schools, minority teacher assignments, optional areas and

open enrollment which led the court to conclude that a

“segregation policy” was enforced in the Park Hill area

were nevertheless viewed by the district court, in their ap

plication to other Denver schools, as isolated individual

occurrences not demonstrative of a pattern nor indicative

of any policy.

The Court of Appeals agreed with the district court both

as to segregation policy in Park Hill and as to the lack

thereof affecting other Denver schools. 445 F.2d at 990-

1002, 1005-07; Appendix, pp. 122a-139a, 147a-150a.

The district court also found that schools which had in

excess of 70% black or 70% Spanish-surnamed student

enrollments19 were failing to offer their students educational

opportunities equal to those afforded white students in

other Denver public schools. 313 F. Supp. at 83, Appendix

at p. 89a. Both because the court concluded that the segre

gated character of the school was the basic (but not exclu

sive) cause of this unequal offering, 313 F. Supp. at 81,

Appendix at pp. 86a-87a, and also because the court found

(after a further hearing on the question of remedy alone)

that desegregation was an essential element of any adequate

19 Some in the Park Hill area and some not.

13

remedy for these conditions, 313 F. Supp. at 96-97, Appen

dix at p. 112a, the district court enjoined respondents to

desegregate and otherwise equalize the educational offering

at these schools.

The Court of Appeals apparently expressed no disagree

ment with the district court’s findings, but balked at approv

ing its order because to do so would, it said, amount to

requiring desegregation of schools which the district court

found had not been segregated by official policy. This, said

the Court of Appeals, would require that it overrule Doivns

v. Board of Educ. of Kansas City 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir.

1964), cert, denied, 380 U.S. 914 (1965), and it declined to

do so.20

20 The Court of Appeals accepted the lower court’s finding that

leaving the schools segregated would mean continued lack of edu

cational opportunities for their students, as well as the finding that

to achieve equal opportunities would require desegregation as

well as compensatory programs (both of which the district court

ordered). But it then held that since desegregation alone would

not suffice, it should not be required at all. (445 F.2d at 1004,

Appendix at p. 144a).

14

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Resolve Conflicts in

Principle Among the Lower Courts.

The issue in this case is not de facto versus de jure seg-

J regationv1 Whatever the term “de facto” may mean, this

case involves a school district in which segregation has

been brought about by regular, systematic and deliberate

__choice of the school authorities.

This is the first case of this sort before this Court from

an area where officially required segregation was not pre

viously authorized by statute. Gf. Gomperts v. Chase, No.

A-245 (September 10, 1971) (Mr. Justice Douglas, Circuit

Justice). But the lower courts have had a significant amount

of litigation involving segregation imposed by government

—but not by State law. E.g., Taylor v. Board of Educ. of

New Rochelle, 191 F. Supp. 181 (S.D.N.Y.), appeal dis

missed, 288 F .2d 600 (2d Cir.), 195 F. Supp. 231 (S.D.N.Y.),

aff’d 294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 368 U.S. 940 (1961);

Clemons v. Board of Educ. of Hillsboro, 288 F.2d 853 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 350 U.S. 1006 (1956); Spangler v. Pasa

dena City Bd. of Educ., 311 F. Supp. 501 (C.D. Cal. 1970);

Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 309 F. Supp. 734 (E.D.

Mich. 1970), aff’d 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir. 1971); Bradley v.

Millihen, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970), 438 F.2d 945 (6th

Cir. 1971), Civ. No. 35257 (E.D. Mich., September 27,1971);

Johnson v. San Francisco Unified School Dist., Civ. No.

C-70-1331 SAW (N.D. Cal., July 9, 1971), stay denied sub

nom. Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson,----- U.S.------No. A-203

(August 25, 1971) (Mr. Justice Douglas, Circuit Justice); *

81 In Swann, this Court referred to “so-called ‘de facto segrega

tion.’ ” 402 U.S. at 17.

15

Soria v. Oxnard School Dist., 328 F. Supp. 155 (C.D, Cal.

1971); Oliver v. Kalamazoo Bd. of Educ., No. K88-71 (W.D.

Mich., August 19, 1971) (oral opinion), aff’d, No. 71-1700

(6th Cir., August 30, 1971); cf. United States v. Board of

School Comm’rs of Indianapolis, Civ. No. IP-68-C-225

(S.D. Ind., August 18, 1971).

Such cases are, of course, different from the so-called

“de facto” suits. See Bell v. School of Gary, 324 F.2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377 U.S. 924 (1964); Deal v.

Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert,

denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967); cf. Downs v. Board of Educ.

of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, denied,

380 U.S. 914 (1965).22

The cases in which the lower courts have determined

that a school district has maintained a policy of segrega

tion should be governed by the same rules, regardless of

geography or the source of the official segregation, as cases

where the initial source was State law. But there is a

division among the lower courts; and this is reflected in

22 These suits involved a variety of different claims—including,

in some of them, a claim not raised here and expressly reserved in

Swann (402 U.S. at 23) : “whether a showing that school segrega

tion is a consequence of other types of state action, without any

discriminatory action by the school authorities, is a constitutional

violation requiring remedial action by a school desegregation de

cree” (emphasis supplied). The reference in text is to that claim,

rejected by the Courts of Appeals, and not to the factual claims—

also rejected on the records in those cases—that a segregation pol

icy was enforced by the school board.

We submit parenthetically that Bell and Downs, which involved

the disestablishment of relatively recent prior state-imposed dual

school structures, would probably have been decided differently in

light of Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) and Swann. Compare Bell v. School City of Gary, 324

F.2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963) with United States v. Board of School

Comm’rs of Indianapolis, Civ. No. IP-68-C-225 (S.D. Ind., August

18, 1971); compare Downs v. Board of Educ. of Kansas City, 336

F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964) with United States v. Board of Educ.,

Tulsa, 429 F.2d 1253 (10th Cir. 1970).

16

the opinions of the courts below in this case, applying

different rules to different geographical parts of the same

school system. Whereas this Court and the lower courts

require desegregation throughout a southern school district

where segregation was imposed by law (even though it

persists only in certain portions of that district), the lower

courts here (and in some other places) have confined de

segregation to discrete areas where particular segregating

deeds have been uncovered and identified.23

Consideration of the Park Hill area schools separately

from the rest of the Denver school system resulted from

the lower courts’ insistence that petitioners demonstrate a

segregating act at every school in order to justify relief.

23 A similar position has been taken by some lower courts in

interpreting Swann’s directive that “ [t]he courtfs] should scruti

nize such [remaining black] schools, and the burden upon the

school authorities will be to satisfy the court that their racial

composition is not the result of present or past discriminatory

action on their part.” 402 U.S. at 26. See, e.g., Mapp v. Board of

Educ. of Chattanooga, Civ. No. 3564 (E.D. Tenn., July 26, 1971)'-

Calhoun v. Cook, Civ. No. 6298 (N.D. Ga., July 28, 1971).’But we

do not understand Svoann to require a complex sociohistorical

analysis of residential patterns by district courts in order to deter

mine the relative impact of segregated schools’ influence upon seg

regated housing patterns, and segregated housing patterns’ influ

ence upon school segregation. If that were indeed necessary, there

would be no need of the presumption against one-race schools’which

Swann announces—and announces precisely for the reason that the

school-related and other influences upon housing patterns in a

school district cannot be neatly separated and evaluated as inde

pendent causal factors. The inquiry is whether the effects and

vestiges of segregation were ever disestablished with the thorough

ness required by the remedial principles announced in Swann; if

not, then all remaining vestiges must be eliminated. We submit

that the District Court stated the correct rules in Mannings:

There is no evidence of any substantiality in the record sup

porting the position that segregation in Hillsborough County

is attributable in any measurable degree to voluntary housing

patterns or other factors unaffected by school board activity.

pAs indicated earlier, the record makes plain that prior to and

since 1954 certain schools in Hillsborough County have been

17

This narrow focus facilitated compartmentalized considera

tion of different areas of the district.24 But the court’s

concern should have been school authorities’ actions any

where in the district creating or maintaining racial and

ethnic segregation. As the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit said—correctly, we submit-—in reviewing a similar

case, Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, 443 F.2d 573, ___

(6th Cir. 1971), a fg 309 F. Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970):

We observe, as did the District Court, that school loca

tion and attendance boundary line decisions, for the

past 15 years, more often than not tended to perpetuate

segregation. Attempted justification of those decisions

in terms of proximity of school buildings, their ca

set aside for black students and others for white students^

With exceptions these schools remain racially identifiable. Over

the years defendants have submitted numerous plans for de

segregation, not one of which has altered the naked fact that

most blacks attend schools which are inordinately black where

as most whites attend schools in which there are no blacks or

only miniscule numbers of blacks. The Court has been unable

to locate a single instance in the record where defendants took

positive steps to end segregation at a black school and there

after segregation returned fortuitously. Indeed, no serious at

tempt has ever been made to eliminate the many black schools.

Based on experience, the Court concludes that what resegre

gation there has been is a consequence of the continued exist

ence of schools identifiable as white or black.

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough County,

Civ. No. 3554-T (M.D. Fla., May 11, 1971) (slip opinion at p. 39).

Where a policy of segregation is established for which the con

stitutionally required corrective action has not been taken, the pre

sumption against one-race schools is not rebutted by a claim that,

independent of the discriminatory school board action, other fac

tors might have produced the segregated situation.

24 Just as in Davis v. Board of School Comm’rs of Mobile, 402

U.S. 33 (1971), this Court indicated that the scope of the inquiry

into remedy should be system-wide, so we submit should the scope

of the inquiry into the matter of constitutional violation be system-

wide.

18

pacity, and safety of access routes requires inconsis

tent applications of these criteria. Although, as the

District Court stated, each decision considered alone

might not compel the conclusion that the Board of

Education intended to foster segregation, taken to

gether, they support the conclusion that a purposeful

pattern of racial discrimination has existed in the Pon

tiac school system for at least 15 years.

Accord, United States v. School Dist. No. 151, 286 F. Supp.

786 (N.D. 111. 1967), aff’d 404 F.2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1968), on

remand, 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969), aff’d 432 F.2d

1147 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 943 (1971);

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, supra.

In finding actionable segregation in the Park Hill schools,

the courts below applied the rule declared in Brewer v.

School Bd. of Norfolk, Virginia, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968), enforced in, for example, Davis v. School Dist. of

Pontiac, Michigan, 309 F. Supp. 734 (E.D. Mich. 1970),26

and accepted by this Court in Swann, 402 U.S. at 7, 20-21,

that school officials may not through school construction

and the drawing of attendance boundaries which follow

racial residential patterns, create segregated schools. E r

roneously, however, the lower courts did not apply that

rule when they considered other Denver schools, but ex

cused segregatory acts on the grounds that they were “re

mote in time” and that intervening population shifts, not

such acts, resulted in the present racially or ethnically

identifiable status of affected schools. 313 F. Supp. at 75,

445 F.2d at 1006, Appendix at pp. 71a-72a, 148a-149a. Cf.

Calhoun v. Cook, supra. While population shifts are of

course a factor, so also are the school authorities’ dis- 25

25 See, e.g., United States v. Board of Educ., Tulsa, 429 F.2d

1253 (10th Cir. 1970).

19

criminatory practices, see Indianapolis, suprctr—and no

court is equipped to make (nor are litigants equipped to

present a sufficient basis for) the fine sociological judgment

as to the relative influence of the two factors upon the

present racial complexion of a school.26

During the 1950-1960 period, the school district was

locating and constructing new schools on the expanding

periphery of the district, away from black population cen

ters, and thus providing easy refuge for white students

who desired to avoid attendance at the minority schools

the district was helping to create. When both aspects of

the policy are considered, we think it hard to imagine that

the school district’s segregatory acts did not play a role,

perhaps the major role, in creating the existing segregated

schools in Denver.

The courts below also excused segregation in the Denver

core city area because they held that while the effect was

clear, petitioners had failed to prove intent. 313 F. Supp.

26 As the district court in the Detroit (Bradley v. Milliken) case

recently put i t :

We recognize that causation in the case before us is both

several and comparative. The principal causes undeniably

have been population movement and housing patterns, but

state and local governmental actions, including school board

actions, have played a substantial role in promoting segre

gation. . . .

6. Pupil racial segregation in the Detroit Public School System

and the residential racial segregation resulting primarily from

public and private racial discrimination are interdependent

phenomena. The affirmative obligation of the defendant Board

has been and is to adopt and implement pupil assignment

practices and policies that compensate for and avoid incorpo

ration into the school system the effects of residential racial

segregation. The Board’s building upon housing segregation

violates the Fourteenth Amendment. See, Davis v. Sch. Dist.

of Pontiac, supra, and authorities there noted.

Bradley v. Milliken, Civ. No. 35257 (E.D. Mich., September 27,

1971) (typewritten opinion at pp. 22, 24).

20

at 75, Appendix at p. 71a, 445 F.2d at 1006, Appendix

at p. 149a. See Petition for Writ of Certiorari, Wright v.

Council of the City of Emporia, O.T. 1970, No. 70-188. This

is an obvious failure to apply the traditionally stringent

equal protection doctrine that the state must justify, by

showing a compelling interest,27 conditions amount to racial

classifications, regardless of intent. Loving v. Virginia, 388

U.S. 1 (1967); Kennedy Park Homes Ass’n, Inc. v. City of

Lackawanna, 436 F.2d 108 (2d Cir. 1970) (per Mr. Justice

Clark), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 1010 (1971); Hawkins v.

Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir. 1971) (rehearing

en banc granted)-, Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th

Cir. 1969); Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 30154

(5th Cir., June 29, 1971); Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of

Educ., No. 29886 and 30387 (5th Cir., July 16, 1971). No

specific intent was required by the courts below in finding

that respondents had caused the Park Hill area segrega

tion.

Finally, we submit, and in clear contradiction to estab

lished law, the Court of Appeals chose to ignore (despite

F.E. Civ. P., Rule 52) the deliberate pattern and policy

of the school district, continuing until at least 1964, of as

signing minority race teachers to schools in which minority

students were concentrated because it gave minority stu

dents role models to emulate. 445 F.2d at 1007, Appendix

at p. 150a. Other courts have long rejected any such pro

posed educational justification for unconstitutional segre

gation. E.g., Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256, 258 (8th Cir.

1960). And it is clear that such faculty assignment prac

tices are violative of the Fourteenth Amendment. Swann,

supra, 402 U.S. at 18; Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond,

27 We doubt that any such interest exists to justify segregation

in the public schools. Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483

(1954). Compare 445 F.2d at 1006, Appendix at p. 148.

21

382 U.S. 103 (1965); Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ;

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430, 435 (1968). In

deed, a school district’s faculty assignment policies are a

reliable indication of its overall policy goals since there can

be no independent justification (such as that claimed for

“neighborhood schools”) for a pattern of racial assign

ments, all teachers being subject to assignment by the dis

trict at its discretion. See, e.g., United States v. School

Dist. No. 151, supra; Davis v. School Dist. of Pontiac, supra;

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 360 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 371

U.S. 828 (1962).

The simultaneous application of contradictory standards

by the courts below leads to anomalous results. Thus, for

example, both Manual and Barrett were built in black

neighborhoods at the extreme eastern edges of their manda

tory attendance zones, which zones were drawn so as to

exclude white residential areas. Barrett Elementary School

opened all black; Manual High (a larger facility) enrolled

nearly all the city’s black high school students and was the

only minority-white school in Denver when it opened. Yet

the tests of intent, remoteness and intervening cause, and

popular consensus, were deemed relevant only to Manual

but not to Barrett.

To desegregate a few schools but leave others as they

are, against the background of segregation brought about

by the school authorities, will do nothing to assuage the

difficulty. Instead, this partial solution, like the partial

solutions of free choice and limited rezoning, will result

only in further impaction of the existing segregation.

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsborough

County, supra, n. 23.28

28 See, e.g., Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, A Report of

the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights (1967) ; Report of the Na

tional Advisory Committee on Civil Disorders (1968) ; Coleman,

Equality of Educational Opportunity (1966).

22

The courts below limited the remedy by applying to the

same lawsuit conflicting rulings of other courts which have

passed upon similar matters. Thus this case is affected

more than any other by those conflicts, which should be

resolved by this Court in order to establish a uniform

approach to school desegregation, North and South.

II.

Other Inequalities in the System, Coupled with Racial

Segregation, Provide Further Reason for Requiring the

Only Workable Remedy: Racial Integration.

Moreover, here the harm of segregation is compounded

by educational inequality of other sorts. The district court

found that the educational opportunities available to mi

nority race students relegated to predominantly minority

schools in Denver were far below the general level of edu

cation in the district. The court applied traditional equal

protection analysis and found this practice created a racial

classification of students in Denver for which no compel

ling justification could be demonstrated. Therefore, the

court required both desegregation and provision of special

programs at these schools in order to equalize educational

opportunity for their students. The district court took this

step not on the basis of any untested assumptions but af

ter careful consideration of the testimony offered by the

parties at a hearing directed toward establishing the ap

propriate remedy for the constitutional deprivation.

The Court of Appeals reversed this part of the district

court’s order. We think the Court of Appeals misconstrued

the basis of the district court’s ruling, but, moreover, its

own opinion drains the concept of equal educational oppor

tunity (recognized by this Court in Brown) of its meaning

by declaring segregation-related inequalities irremediable

23

in the federal courts unless that segregation is proved to

have been caused entirely by school authorities.

We have argued above that both the Court of Appeals

and the district court applied erroneous legal principles in

ascertaining the existence and extent of state-imposed seg

regation in the Denver public schools, and what remedy

must follow. If we are correct, then the schools which were

ordered desegregated by the district court because they

were failing to offer an equal educational opportunity must

be desegregated anyway. We believe, however, that irre

spective of the Court’s conclusion on that subject, the dis

trict court’s order—that tangible inequalities should be

remedied by desegregation — was otherwise proper and

should have been affirmed.

The district court’s finding of unequal educational oppor

tunity rested upon petitioner’s demonstration that (a)

there were certain tangible, measurable differences in the

school system’s allocation of resources to predominantly

minority schools, e.g., teacher experience differentials in

favor of white schools and generally older and smaller

facilities at minority schools; (b) there were as well tangi

ble, measurable differences in educational outcome measures

between the same two groups of schools, e.g., character

istically lower achievement test scores and higher pupil

dropout rates at minority schools and a progressive re

gression in the academic progress of the minority child

from lower to higher grade levels in the minority schools;

and (c) the weight of expert opinion was that measured

differences in educational outcomes of the sort found in

Denver were not the result of differences in innate ability

but of the composition of the student body at predomi

nantly minority schools. Petitioners’ expert witnesses29

29 Dr. Dan Dodson, Dr. Neil Sullivan, Dr. James Coleman and

Dr. Robert O’Reilly.

24

testified at length about the intangible30 educational dis

advantages which result from racially concentrated minor

ity group schools. In sum, petitioners’ expert witnesses

testified that the observed inequalities were due to factors

within the control of the. school system, including the com

position of the student bodies at various schools.

The district court concluded that no compelling justi

fication for the systematic deprivation of educational

opportunity31 to minority race students32 had been

30 The testimony was undisputed that segregation produces feel

ings of isolation, inferiority and powerlessness in the minority chil

dren; produces low academic expectancy among teachers which

then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of low achievement; pro

duces low morale among both pupils and teachers, and a high rate

of teacher turnover as most teachers sought to escape these schools

at the first opportunity.

81 Petitioners have never claimed nor did the district court’s deci

sion in any way rest upon some notion that educational opportunity

was solely related to, or demonstrated by, an equivalent perform

ance by every student. Obviously students will have, on an indi

vidual basis, different aptitudes and will perform, ideally, to the

full extent of their varying capabilities. What is significant about

the tangible measures of output here, such as achievement test

scores, is two things. First, they establish a consistent and system

atic differential between white schools and minority schools of such

magnitude as to vitiate any suggestions that the observed pattern

is merely the result of the interplay of different individual capaci

ties. Cf. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Education, 318 F.2d

425 (5th Cir. 1963), 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964). Second, they

confirm the testimony of petitioners’ expert witnesses that such

segregated schools characteristically produce educationally unde

sirable effects upon the children and the teachers and can be ex

pected to adversely affect the educational opportunity afforded the

students.

32 The “70%” limitation of the district court as well as his re

fusal to require relief to schools which had less than 30% white

students but also less than 70% black or 70% Spanish-surnamed

students, were of the court’s own fashioning. Although petitioners

raised the combined minority-race school issue on appeal to the

Tenth Circuit, that court did not pass upon it and a remand for

that purpose upon disposition of this cause upon this Petition

would be appropriate.

25

shown,33 and the court, therefore, ordered corrective mea

sures—including desegregation (which petitioners’ expert

witnesses had testified was essential if the major cause

of the inequality—segregated schools—was to he elim

inated).

Thus, the district court’s order gave substance to the

constitutional guarantee of equal educational opportunity.

Cf. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U.S. 637

(1950); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950); Sipuel v.

Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948); Missouri ex rel.

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938). The Court of Ap

peals, however, imposed a purely extraneous limitation

upon this remedy for a constitutional deprivation. To some

extent, the Court of Appeals’ ruling is based upon a mis

construction of the district court’s ruling but, even accept

ing its reading of the lower court opinions, the Court of

Appeals has plainly held that there is no remedy for the

unconstitutional deprivation of educational opportunity to

minority race students if execution of that remedy would

conflict with a school system’s adherence to the “neighbor

hood school” assignment policy.

On either ground, the decision is wrong and ought to be

reviewed by this Court because of the national implica

tions of a ruling that the Constitution provides no remedy

for the racially unequal provision of education by the

state.34

33 Cf. Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ; McLaughlin v.

Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1963); Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401

(D.D.C. 1967), aff’d sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175

(D.C. Cir. 1969). See also Comperts v. Chase,----- U .S .-------, No.

A-245 (Sept. 10, 1971) (Mr. Justice Douglas, Circuit Justice).

34 But see Serrano v. Priest, No. L.A. 29820 (Supreme Ct. Cal.,

August 30, 1971) (en banc).

26

CONCLUSION

W h er efo r e , p e t i t io n e r s r e s p e c tfu l ly p r a y t h a t a w r i t o f

c e r t io r a r i be g r a n te d .

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Green berg

J am es M. N abrit , III

N orman J. O h a c h k in

C h a rles S t e p h e n R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

G ordon G. Gr e in e r

R obert T. C onnery

500 Equitable Building

Denver, Colorado 80202

Attorneys for Petitioners

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219