LDF Scholarships to Georgia Students Aim at Desegregation, More Black Southern Lawyers

Press Release

June 30, 1971

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 6. LDF Scholarships to Georgia Students Aim at Desegregation, More Black Southern Lawyers, 1971. c473bc8e-ba92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/107dfd06-3497-4dce-ac4e-521495eaab87/ldf-scholarships-to-georgia-students-aim-at-desegregation-more-black-southern-lawyers. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

1g

PressRelease ft ae ae ae

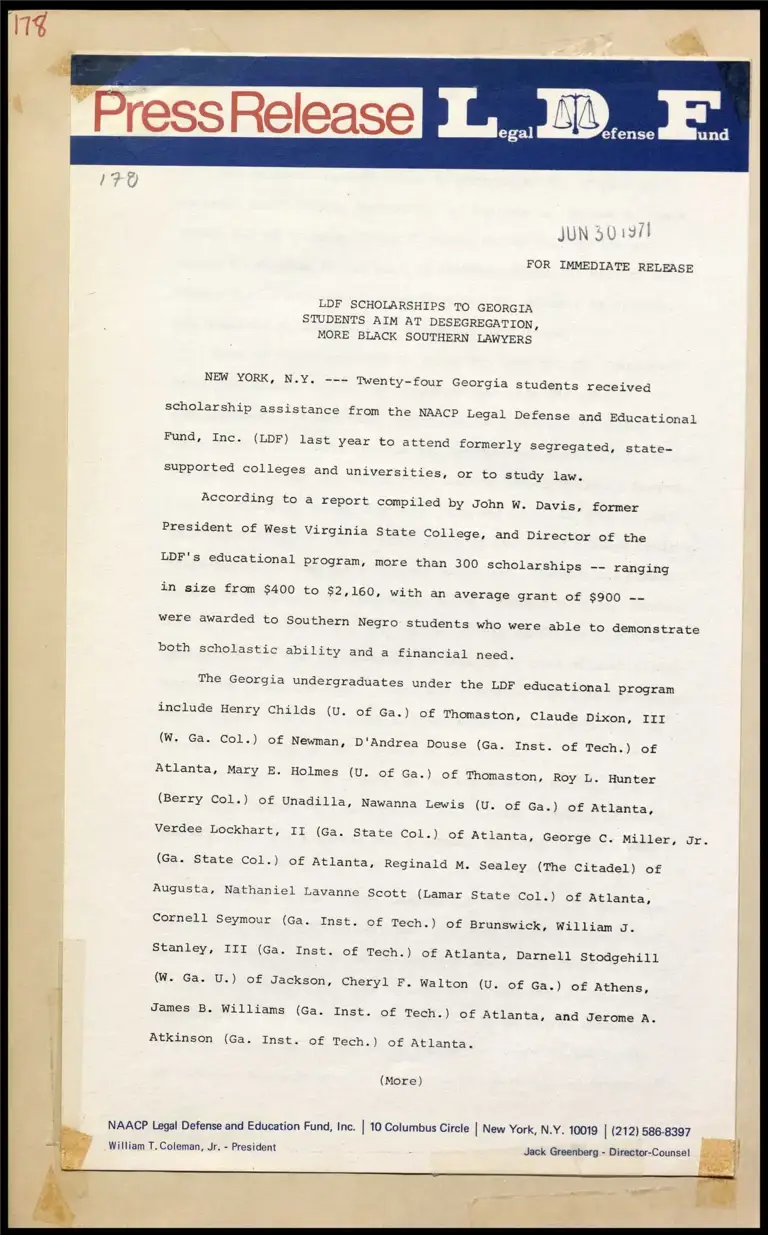

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

LDF SCHOLARSHIPS TO GEORGIA

STUDENTS AIM AT DESEGREGATION,

MORE BLACK SOUTHERN LAWYERS

NEW YORK, N.Y. --- Twenty-four Georgia students received

scholarship assistance from the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc. (LDF) last year to attend formerly segregated, state-

supported colleges and universities, or to study law.

According to a report compiled by John w. Davis, former

President of West Virginia State College, and Director of the

LDF's educational program, more than 300 scholarships -- ranging

in size from $400 to $2,160, with an average grant of $900 --

were awarded to Southern Negro students who were able to demonstrate

both scholastic ability and a financial need.

The Georgia undergraduates under the LDF educational program

include Henry Childs (U. of Ga.) of Thomaston, Claude Dixon, III

(W. Ga. Col.) of Newman, D'Andrea Douse (Ga. Inst. of Tech.) of

Atlanta, Mary E. Holmes (U. of Ga.) of Thomaston, Roy L. Hunter

(Berry Col.) of Unadilla, Nawanna Lewis (U. Of Ga.) of Atlanta,

Verdee Lockhart, II (Ga. State Col.) of Atlanta, George C. Miller, gr.

(Ga. State Col.) of Atlanta, Reginald mM. Sealey (The Citadel) of

Augusta, Nathaniel Lavanne Scott (Lamar State Col.) of Atlanta,

Cornell Seymour (Ga. Inst. of Tech.) of Brunswick, William J.

Stanley, III (Ga. Inst. of Tech.) of Atlanta, Darnell Stodgehill

(W. Ga. U.) of Jackson, Cheryl F. Walton (U. Of Ga.) of Athens,

James B. Williams (Ga. Inst. of Tech.) of Atlanta, and Jerome A.

Atkinson (Ga. Inst. of Tech.) of Atlanta.

(More)

NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, Inc. | 10 Columbus Circle | New York, N.Y. 10019 | (212) 586-8397

oe William T. Coleman, Jr. - President Jack Greenberg - Director-Counsel

LDF SCHOLARSHIPS

PAGE TWO

Law students include Jason R. Archambeau (U. of Ga.) of

Augusta, Jerry Boykin (Mercer U.) of Monticello, Marvin N. Clark

(Emory U.) of Atlanta, Ivory K. Dious (U. of Ga.) of Athens,

Marvin C. Mangham (U. of Ga.) of Atlanta, Samuel R. Martin, Jr.

(Emory U.) of Atlanta, Charles Peterson (U. of Ga.) of Atlanta,

and Augustus D. Aikens (Fla. State U.) of Quitman.

Most of these students -- those who have not yet completed

their educations -- will be eligible next term for similar

scholarships. In addition, LDF hopes to increase the number of

scholarships available through its two-pronged educational program:

the Herbert Lehman Education Fund and the Lawyer Training Program.

The Herbert Lehman Education Fund was begun in 1964 by LDF

when its litigation had brought about strict court rulings against

state-financed, segregated higher education. Through the Lehman

Fund, LDF provides incentives for black students to enter formerly

all-white colleges and universities, at the same time providing

incentives for the institutions -- usually in need of scholarship

monies -- to accept them. There are currently 122 students under

this program which has given out 586 scholarships (more than 60 to

Georgia students) in its 7 years of operation.

The Lawyer Training Program, on the other hand, was a spin

off of the Lehman Fund to correct the critical shortage of black

lawyers which has hampered LDF's efforts to reach out into many

rural areas.

According to LDF, black lawyers now comprise only about one

per cent of the legal profession. The most hopeful estimates of

the black lawyer/population ratios show one black lawyer for every

21,230 black Americans. But in some rural sections of the country

-- especially the South and Southwest -- it is feared that the

disparity heightens to one black lawyer for every 37,000 black

Americans. White Americans have no problems obtaining sympathetic

LDF SCHOLARSHIPS

legal assistance:

for every 600 white Americans.

PAGE THREE

the national average indicates one white lawyer

In its first year of operation, the Lawyer Training Program

assisted some 212 law students (including the 8 Georgia students)

and will continue to provide them with scholarships until they

complete their three years of law training.

year (1971-72),

made available. This process --

each year -- will continue until

adding 1,500 blacks to the legal

According to Dr. Davis, the

provide scholarships to more and

law, but will place many of them

an additional 300

For the next school

3-year law scholarships will be

of adding 300 new scholarships

the LDF's seven year goal of

profession is met.

Legal Defense Fund will not only

more young men and women studying

in summer jobs in its New York

office and in offices of cooperating attorneys around the country,

and, to those who show real promise, offer them a post-graduate

year at the Fund's head office, then help them to set up practice

in any area sorely in need of a black lawyer.

The cost of the Lawyer Training Program for a seven-year

period is expected to run well over $16,000,000.

=<

For further information contact:

NOTE:

and Educational Fund,

Dr. John W. Davis or

Sandy O'Gorman

(212) 586-8397

Please bear in mind that the NAACP Legal Defense

Inc. is a completely

separate and distinct organization, even though

we were established by the NAACP and retain those

initials in our name. Our correct designation

is NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

frequently shortened to LDF.