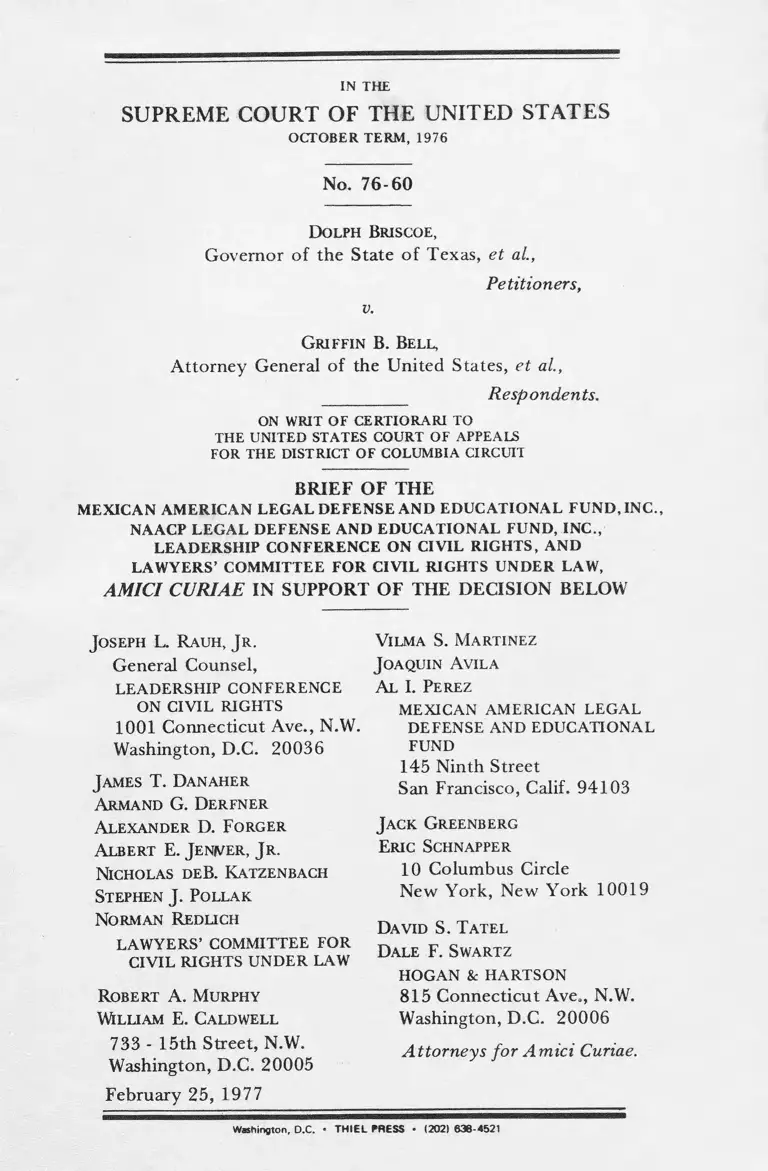

Briscoe v. Bell Brief of the Mexican Americal Legal Defense and Educational Fund, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, and Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Amici Curiae in Support of the Decision Below

Public Court Documents

February 25, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Briscoe v. Bell Brief of the Mexican Americal Legal Defense and Educational Fund, NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, and Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Amici Curiae in Support of the Decision Below, 1977. acf76293-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/108849a8-ef59-4119-8c5a-f3daa2c13f62/briscoe-v-bell-brief-of-the-mexican-americal-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-leadership-conference-on-civil-rights-and-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-amici-curiae-in-support-of-the-d. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

G r if f in B. Bell ,

Attorney General of the United States, et al.,

________ Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE ON CIVIL RIGHTS, AND

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW,

AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE DECISION BELOW

Joseph L. R a u h , J r . V il m a S. M a r t in e z

General Counsel, J o a q u in A v il a

LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE A l I. PEREZ

ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

1001 Connecticut Ave., N.W. DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

OCTOBER TERM, 1976

No. 76-60

Washington, D.C. 20036

J am es T. D a n a h e r

A r m a n d G. D e r f n e r

A l e x a n d e r D. F o r g e r

A l b e r t E. J enjver, J r .

Nic h o l a s d e B. K a t ze n b a c h

Steph en J . Po l l a k

No r m a n R e d lich

fu n d

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, Calif. 94103

J a c k G r e e n b e r g

Eric Sch n a ppe r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LAW YERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

D a v id S . T a t e l

D a l e F. S w a r t z

R o b e r t A . M u rph y

WIl l ia m E. C a l d w e l l

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

February 25, 1977

HOGAN & HA RTS ON

815 Connecticut Ave», N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Attorneys for Amici Curiae.

Washington. D .C . • T H IE L M E S S • (202) 638-4521

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1^1

INTEREST OF AMICI CU RIAE ....................................................1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.........................................................3

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................... 7

ARGUMENT

I. Texas’ arguments regarding the construction and

application of the Voting Rights Act Amend

ments of 1975 are without merit......................................... 9

II. Congress intended the 1975 Amendments to ex

tend the protections o f the Voting Rights Act of

1965 to Mexican American and black voters in

T e x a s .......................................................................... • • • 12

III. The legislative record establishes that Mexican

Americans and blacks in Texas have been sub

jected to systematic and pervasive voting dis

crimination........................................................................... 14

A. English-only elections.......................................................15

B. Registration...................................................................... 18

C. Discrimination at the p o l ls ............................................ 21

D. Discrimination against minority candidates................25

E. Dilution of minority v o te s ............................................ 28

1. Malapportionment and gerrymandering.................. 29

2. Multi-member districting............................................ 34

3. The place system, majority runoff require

ments, and at-large elections.................................... 36

4. Annexations and de-annexations ............................. 41

IV. Extension o f the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to

Texas will facilitate the elimination of other

forms of economic and social discrimination.................. 45

CONCLUSION................................................................................ 50

(i)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page

Cases:

Allee v. Medrano, 416 U.S. 802 (1974).................................... 21

American Party o f Texas v. White, 415 U.S. 767

(1974), rehearing denied, 416 U.S. 1000 (1974). ............. 27

Arroyo v. Tucker, 372 F. Supp. 764 (E.D. Pa.

1974)............................... ........................... .............................. 16

Beare v. Smith, 321 F. Supp. 1100 (S.D. Tex. 1971),

aff’d sub nom., Beare v. Briscoe, 498 F.2d 244

(5th Cir. 1 974 )........................................................................ 19

Briscoe v. Levi, 535 F.2d 1259 (D.C. Cir. 1976), cert,

granted, 45 U.S.L.W. 3416 (Dec. 6, 1976) (No.

76-60)..................................................................................... . 10

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972).................................... 25

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent School Dis

trict, 324 F. Supp. 599 (S.D. Tex. 1970), aff’d in

relevant part, 469 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) (en

banc), cert, denied, 413 U.S. 920 (1973), rehearing

denied, 414 U.S. 881 (1973)................................... 16, 47, 49

City o f Petersburg, Virginia v. United States, 354 F.

Supp. 1021 (D.D.C. 1972), aff’d, 410 U.S. 962

(1973 )........................................... -41

Connerton v. Oliver, 333 F. Supp. 201 (S.D. Tex.

1 9 7 1 ) ...........................................................................................25

David v. Garrison, Civ. Ac. No. TY-73-CA-113 (E.D.

Tex. 1975)................................................................................ 38

Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., 422 U.S. 922 (1975)......................... 11

Duncantell v. Houston, 333 F. Supp. 973 (S.D. Tex.

1 9 7 1 ) ........................................... 25

East Carroll Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424

U.S. 636 (1 9 7 6 ) ............................................................. 2

Garcia v. Carpenter, 525 S.W.2d 160 (Tex. Sup.

Ct. 1975) ..................................................................................... 27

Garza v. Smith, 320 F. Supp. 131 (W.D. Tex. 1970),

vacated and remanded for appeal to the Fifth

Circuit, 401 U.S. 1006 (1971), appeal dismissed

PageCases, continued:

for lack o f jurisdiction, 450 F.2d 790 (5th Cir.

1971) ...................................................................................... 15

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285

(1969 )........................................................................................ 16

Gonzales v. Sinton, 319 F. Supp. 189 (S.D. Tex.

1970).......................................................................................... 25

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)..........................9

Graves v. Barnes I, 343 F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex.

1972) , aff’d in relevant part sub nom., White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)

................................. 18, 19, 25, 26, 33, 35, 46

Graves v. Barnes II, 378 F. Supp. 640 (W.D. Tex.

1974) , vacated and remanded for determination

o f mootness sub nom., White v. Regester, 422

U.S. 935 (1 9 7 5 ) ................................................. 26, 33, 36, 39

Graves v. Barnes III, 408 F. Supp. 1050 (W.D. Tex.

1976).......................................................................................... 36

Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U.S. 45 (1 9 3 5 )............................... 18

Guerra v. Pena, 406 S.W.2d 769 (C .C .A . Tex. 1966)............. 21

Harper v. Virginia Board o f Elections, 383 U.S. 663

(1966).................................................................. 18

Harrison v. Northern Trust Co., 317 U.S. 476 (1 9 4 3 ).......... 12

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954 )................................. 49

Hill v. Stone, 421 U.S. 289 (1975), rehearing denied,

422 U.S. 1029 (1 9 7 5 ) ........................................................... 25

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1 9 6 6 )............................. 49

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 5 6 3 (1 9 7 4 ) .................... - ..................9

Lipscomb v. Wise, 399 F. Supp. 782 (N.D. Tex.

1975) ....................................................................................... 38

Mauzy v. Legislative Redistricting Board, 471 S.W.2d

570 (Tex. Sup. Ct. 1 971 ).................................................34, 35

Morris v. Gressette, prob. juris, noted, 45 U.S.L.W.

3407 (Dec. 6, 1976) (No. 75-1538).................................... 10

National Association for the Advancement o f Colored

People v. New York, 413 U.S. 345 (1973).............................2

(iv)

National League o f Cities v. Usery, 96 S.Ct. 2465

(1976 )................................................................................... . . 11

New York v. United States, 419 U.S. 888 (1974), affg

65 F.R.D. 10 (D.D.C. 1 9 7 4 )................................................. 16

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73 (1 9 3 2 ).......... .. ....................... 18

Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927).................................. 18

Pablo Puente v. City o f Crystal City, Civ. Ac. No.

DR-70-CA-4 (W.D. Tex. April 3, 1970)............................... 25

Puerto Rican Organization for Political Action v.

Kusper, 350 F. Supp. 606 (N.D. 111. 1972),

aff’d, 490 F.2d 575 (7th Cir. 1973).......................... .. 16

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1 9 6 4 ) .................................. 46

Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976). ..................................... 11

Robinson v. Commissioners Court, Anderson County,

Civ. Ac. No. TY-CA-73-236 (E.D. Tex. Mar. 15,

1974), affd in relevant part, 505 F.2d 674 (5th

Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) ................................................................... 29, 30, 49

Sabala v. Western Gillette, Inc., 362 F. Supp. 1142

(S.D. Tex. 1973), aff’d in relevant part, 516 F.2d

1251 (5th Cir. 1975 ).............................................................. 48

Smith v. Allright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944)..................................2, 18

Smith v. Craddick, 471 S.W.2d 375 (Tex. Sup. Ct.

1971).............................................................. 34

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966)........................................................................... 10, 11, 43

Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1 9 7 4 ) ............................ 11

Sylva v. Fitch, Civ. Ac. No. SA-76-CA-126 (W.D.

Tex. Sept. 26, 1 9 7 6 )............................................................... 33

Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S. 461 (1953)......................................... 18

Torres v. SACS, 73 Civ. 3921 (S.D.N.Y. July 25,

1974).............................................. 16

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409

U.S. 205 (1 9 7 2 ) .............................- .........................................9

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1 9 7 0 ) .................................. 25

Cases, continued: *>a*’ e

Cases, continued:

Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965), rehearing

denied, 380 U.S. 989 (1965)...................................................... 9

United States v. Alpers, 338 U.S. 680 (1950).......................... 12

United States v. American Trucking Association, 310

U.S. 534 (1 9 4 0 ) ...................................................................... 12

United States v. Interim Board o f Trustees o f the

Westheimer Independent School District, et ai,

Civ. Ac. No. H-77-121 (S.D. Tex.) (pending).................. „ 42

United States v. Texas, 252 F. Supp. 234 (W.D. Tex.),

aff’d per curiam, 384 U.S. 155 (1 9 6 6 )............................... 18

Weaver v. Commissioners Court, Nacogodoches

County, Civ. Ac. No. TY-73-CA-209 (E.D.

Tex. Mar. 15, 1974)................................................................ 30

Weaver v. Muckleroy, Civ. Ac. No. 5524 (E.D. Tex.

Jan. 27, 1975).....................................................................31, 38

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971)............................... 37

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973)

.................................... 4, 5, 27, 28, 35, 36, 37

White v. Regester, 422 U.S. 935 (1 9 7 5 ).................................. 36

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973)...................................... 29

Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1 9 6 8 ).................................. 27

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1 9 7 1 )...............................10, 11

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973), aff’d sub nom. East Carroll Parish

School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636

(1976)........................................................................................ 37

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §2282 ............................ .. .........................................8, 10

42 U.S.C. §1973 et seq..................................................................... 3

42 U.S.C. § 1973b ( b ) ....................................................................10

42 U.S.C.A. §1973b (b)(l)(1976 Supp.).....................................16

42 U.S.C.A. §1973b (f)(l)(1976 S u p p .)...................................... 6

42 U.S.C.A. §1973aa-la(a) (1976 Supp.).......................................6

(v)

Page

Pub. L. No. 94-73, 42 U.S.C.A. §1973 et seq. (1976

Supp.)......................................................................................5, 6

Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 1.08a (1976-77 Supp.)

(V ernon )................................................................................... 16

Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 5.11a (Vernon).................................. 19

Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 5.18(b) (repealed) ..........................19

Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 8.13 (1976-77 Supp.)

(V ernon )...................................................................................... 15

Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 8.15 (Vernon).....................................22

TEX. CONST, art. VI, §2 (V.A.T.C. 1 966 )....................... 19

Miscellaneous:

Brief for the Petitioners................................................. 9, 10, 17

Derfner, Racial Discrimination and The Right to Vote,

216 Vand.L.Rev. 523 (1 9 7 3 )............................. 43

Greenfield and Kates, Mexican Americans, Racial Dis

crimination and The Civil Rights Act o f 1866, 63

Calif.L.Rev. 662 (1 9 7 5 )......................................................... 48

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Civil and Con

stitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judic

iary, House o f Representatives, 94th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1 9 7 5 ).........................................................................passim

Hearings Before the Senate Subcommittee on Constitu

tional Rights, Extension of the Voting Rights Act

o f 1965, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975)............................... passim

H.R. Rep. No. 94-196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) . . . passim

“ Interim Report: The Voting Rights Act in Texas” by

The Committee on Elections of the Texas House of

Representatives........................................................................... 45

Kibbe, P., Latin Americans in Texas (1946)..................... 48, 49

Letter from United States Attorney General to the

General Counsel for the Secretary o f State of

Texas, dated March 8, 1976 .................... 17

Mazmanian, Third Parties in Presidential Elections

(1974) . ........................................................................... 27

(vi)

Statutes, continued: --------

(vii)

Mittelbach, F., and Marshall, G., The Burden o f

Poverty, Mexican American Study Project,

UCLA Advance Report V (1966)........................................... 48

Moore, J., Mexican Americans, 60 (1 9 7 0 )................................. 48

Moore, J., and Mittelbach, F., Residential Segre

gation in the Urban Southwest, Mexican Amer

ican Study Project, UCLA Advance Report IV

(1966 )....................................................................................... 48

N.Y. Times, January 18, 1977 at A 1 6 .................................... 47

Miscellaneous, continued: _5

Project Report: Dejure Segregation o f Chicanos in

Texas Schools, 7 Harv. Civil Rights-Civil Liberties

L.Rev. 307 (1972)................................................................... 47

Rohan, H., The Mexican American (1968) (Staff Paper

prepared for the United States Commission on Civil

Rights) ........................................................................................49

S. Rep. No. 94-295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975).................. 13

Texas Senate Bill 300 (1 9 7 5 ) .................................................... 19

United States Attorney General, Letters of Objection

Pursuant to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act:

December 10, 1975 ...................................................

January 23, 1976 ......................................................

January 26, 1976 ......................................................

April 2, 1976 ...................................................... - • •

April 16, 1976 ...........................................................

May 24, 1976 ...........................................................

July 7, 1976...........................................................

July 27, 1976 ...........................................................

October 13, 1976 ...................................................

January 13, 1977 ................ ...............................

United States Commission on Civil Rights, “ Ethnic-

Isolation of Mexican Americans in Public Schools

o f the Southwest,” Report I (1970).....................

. . 20

27, 33

. . 33

. . 42

41

31

32

32

42

47

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Staff

Memorandum, Expansion of the Coverage of

The Voting Rights Act (June 5, 1975)

................................. 15, 16, 20, 21. 22, 24. 47

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Staff

Memorandum, Summary o f Preliminary Re

search on the Problems of Participation by

Spanish Speaking Voters in the Electoral

Process (April 23, 1975)........................................................... 28

United States Commission on Civil Rights, “ Mexican

American Education in Texas: A Function of

Wealth,” Report IV (1972) .................................................... 47

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Mexican

Americans and the Administration of Justice

in the Southwest (1970)......................................................... 48

United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Vo ting

Rights Act: Ten Years After (1975).............................3, 5, 43

Young, The Place System in Texas Elections, Austin,

Texas: Institute o f Public Affairs (1965)............................. 37

40 Fed. Reg. 43746 (Sept. 23, 1975)............................................6

121 Cong. Rec. (June 2, 1975) at 4712 (Remarks of

Cong. Edwards) . ..........................................................................13

121 Cong. Rec. (June 2, 1975) at 4746 (Remarks o f

Congresswoman Jordan)............................................................ 13

(viii)

Miscellaneous, continued: ^aSe

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1976

No. 76-60

D o l p h B r i s c o e ,

Governor of the State of Texas, et al.,

G r if f in B . B e l l ,

Attorney General of the United States, ct al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE ON CIVIL RIGHTS, AND

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW,

AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE DECISION BELOW

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (MALDEF) is a nonprofit corporation dedicated

to ensuring that the civil rights of Mexican Americans

are properly protected. With offices throughout the

Southwest, in California, and in Washington, D.C.,

MALDEF provides legal assistance to safeguard the Mexi

can American community’s educational, political and

voting rights.

Protecting the voting rights of IMexican Americans has

long been one of MALDEF’s key concerns. It has repre

sented Mexican American voters throughout the South-

1

2

west, and provided technical assistance to the Congres

sional committees which held hearings on the Voting

Rights Act Amendments o f 1975. The voting rights of

Mexican American citizens in Texas have been of particu

lar concern to MALDEF. It has devoted substantial

resources to monitor and implement the 1975 Amend

ments, and through its office in San Antonio has brought

many cases under the Act and filed other actions chal

lenging discriminatory voting practices and procedures

on behalf of Mexican American voters in Texas. How

ever, MALDEF does not have sufficient resources to

challenge all such practices. Thus, continued enforcement

of the Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1975, which

are here challenged by the State o f Texas, is essential if

the voting rights o f the State’s minority citizens are to be

fully protected.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a nonprofit corporation incorporated under the

laws of the State o f New York. It was founded to assist

Negroes to secure their constitutional rights by the prose

cution of lawsuits. Its charter declares that its purposes

include rendering legal services gratuitously to Negroes

suffering injustice by reason o f racial discrimination. For

many years attorneys of the Legal Defense Fund have

represented minorities before this Court and the lower

courts in litigation to secure their constitutionally pro

tected right to vote. East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976); National Association for

the Advancement o f Colored People v. New York, 413

U.S. 345 (1973); Smith v. Allright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944).

The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights comprises

137 civil rights, fraternal, religious, labor, and civic

organizations, as well as organizations for the rights of

women and the handicapped. In its strive for civil rights

the Leadership Conference has been especially concerned

with the right to vote and has worked for the enactment

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, its successors and ex-

3

tensions, and for the full implementation and enforce

ment of these laws in the interest of the right to vote for

all Americans.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights under Law is

a nonprofit corporation organized in 1963 at the request

of the President of the United States; its Board of

Trustees includes thirteen past presidents of the Ameri

can Bar Association, three former Attorneys General, and

two former Solicitors General of the United States. The

Committee’s primary mission is to involve private lawyers

throughout the country in the quest of all citizens to

secure their civil rights through the legal process. Among

its activities has been the provision o f counsel in voting

rights cases throughout the South; in this regard, the

Committee has been particularly concerned with enforce

ment of the Voting Rights Act.

The written consent of the parties, pursuant to Rule

42(2) o f the Supreme Court of the United States, is

filed herewith.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §1973 et

seq., (hereinafter the “ 1965 Act” ), has been hailed as the

most effective civil rights legislation ever passed.1 Since

its enactment, the number o f blacks registered to vote in

the seven southern states covered by the Act has nearly

doubled, and the number of black elected officials has

increased almost tenfold.2 The Chairman of the United

*H.R. Rep. No. 94-196, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) at 4

[hereinafter “ H.R. Rep. 94-196” ].

2Senate Hearings Before the S. Subcomm. on Constitutional

Rights, Extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 94th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1975) at 121, [hereinafter “ 1975 Senate Hearings” ].Se<?

also United States Commission on Civil Rights, The Voting Rights

Act: Ten Years After (1975) at 40-52 [hereinafter “ Ten Years

After” ) .

4

States Civil Rights Commission has underscored the im

portance o f the 1965 Act:

The Voting Rights Act, as a symbol o f national

commitment and as a set of enforcement mechan

isms, has contributed greatly to the changing politi

cal circumstances o f minorities in the covered juris

dictions. Where earlier legislation proved ineffective,

the Voting Rights Act has made the 15th amend

ment a living, forceful entity in many areas. Vigor

ously enforced, the act can ensure that minority

citizens will not be deprived of their right to partici

pate in their own government.3

The 1965 Act, however, proved deficient in one major

respect: it provided no protection to Mexican Americans

and other language minorities subjected to the same

forms of voting discrimination suffered by southern

blacks. Like blacks, Mexican Americans have long been

excluded from the electoral process. In White v. Regester,

412 U.S. 755, 768 (1973), this Court affirmed the dis

trict court’s findings that:

“ [A] cultural incompatibility . . . conjoined with

the poll tax and the most restrictive voter registra

tion procedures in the nation have operated to effec

tively deny Mexican-Americans access to the politi

cal processes in Texas even longer than blacks were

formerly denied access by the white primary.”

English-only elections, intimidation, discriminatory en

forcement of electoral laws, gerrymandering, multi

member districting, and widespread use of at-large elec

tions also have denied Mexican Americans equal access to

the electoral process.4 In 1974 the disparity between

Mexican American and white registration in some areas of

3 Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Civil and Constitu

tional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Repre

sentatives, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975) at 29 [hereinafter “ 1975

House Hearings” ] .

4 See discussion, infra, at 28-42. See also H.R. Rep. 94-196 at

16-23.

5

Texas was estimated at 10-15 percent,5 and Mexican

Americans held only 2.5 percent of the State’s elected

offices even though they comprise approximately 18 per

cent o f its population.6 Blacks in Texas, who comprise

approximately 12 percent o f the State’s population, have

suffered similar treatment, with similar results.7 In 1974,

blacks held only .5 percent of the elected offices in

Texas.8

In January 1975 the United States Commission on

Civil Rights recommended that Congress expand the

1965 Act to protect the voting rights of language minor

ity citizens.9 Following the Commission’s recommenda

tion, Congress held hearings to examine the evidence of

voting discrimination against language minorities. The

voluminous hearing record documented a pattern of

voting discrim ination against Mexican Americans

throughout the Southwest similar to that which led to

enactment of the 1965 A ct.10

Confronted with such evidence, Congress voted over

whelmingly11 to enact the Voting Rights Act Amend

ments o f 1975, Pub. L. No. 94-73, 42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 et

5 1975 House Hearings at 807-09.

6Id. at 276.

^1975 House Hearings at 276, 360-61, 367-69. See also

White v. Regester, supra. There are more blacks living in Texas than

in any of the southern states covered by the 1965 Act, Texas has

almost 1.5 million minority residents over the age of 25, or three

times the number of minorities in the largest of the southern

covered jurisdictions. 1975 House Hearings at 360.

^1975 House Hearings at 248, 276.

9Ten Years After, at 355a.

111See generally H.R. Rep. 94-196 at 16-23. See also 19/5

Senate Hearings at 96-97, 1975 House Hearings at 399-405.

11 The House vote was 341 yeas, 70 nays; the Senate vote 77

yeas, 12 nays.

6

seq. (1976 Supp.) (hereinafter the “ 1975 Amend

ments” ). Congress found that . . voting discrimination

against citizens of language minorities is pervasive and

national in scope,” that “ through the use o f various prac

tices and procedures, citizens o f language minorities have

been effectively excluded from participation in the elec

toral process,” and that “ in many areas of the country,

this exclusion is aggravated by acts of physical, economic

and political intimidation.” 42 U.S.C.A. § § 1973b(f)(l),

1973aa-la(a) (1976 Supp.).

In September, 1975, the Attorney General and the

Director o f the Census determined that the entire state of

Texas is subject to Title II of the 1975 Amendments. 12

As a consequence, Texas and all political subdivisions

within it may no longer conduct English-only elections

and, like the Southern states covered by the Voting

Rights Act since 1965, may not enforce changes in elec

toral laws or procedures without first establishing to the

satisfaction o f the Attorney General or a three-judge dis

trict court in the District of Columbia that the change

does not have a discriminatory purpose or effect. The

1975 Amendments also made applicable to Texas the pro

visions of the 1965 Act which authorize the Attorney

General to assign federal examiners and observers to

register eligible voters and observe the conduct of elec

tions.

Extension o f the Voting Rights Act to Texas has given

its Mexican American and black citizens reason to hope

that they may finally be able to participate in the elec-

1240 Fed. Reg. 43746 (Sept. 23, 1975).

7

toral process in a free and unimpaired manner, and there

by protect their full range o f political and civil rights.

Texas, however, now seeks to avoid this result, arguing

that the Attorney General and Director of the Census, to

whom Congress delegated enforcement responsibility,

made technical errors in the interpretation and applica

tion of the coverage formula of the 1975 Amendments.

The decisions below, as well as the brief herein of the

Attorney General and Director of the Census, demon

strate that the arguments Texas makes are without merit.

Accordingly, this brief will not repeat the Attorney Gen

eral’s arguments. Rather, Section I discusses several addi

tional reasons why Texas’ arguments are without merit,

and Sections II and III demonstrate that the Attorney

General’s interpretation of the statute is consistent with

one of the primary purposes of the 1975 Amendments,

namely, the extension of the protections of the Voting

Rights Act to Mexican American and black voters in

Texas. Finally, Section IV demonstrates that extension of

the Act to Texas will better enable its minority citizens

to eliminate discrimination in education, housing and

other areas.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The brief for the Attorney General and Director of the

Census demonstrates that petitioners’ arguments regard

ing the construction and application of the Voting Rights

Act Amendments o f 1975 are without merit. The con

struction of the statute by the Attorney General and the

Director of the Census should be given great deference

because Congress has delegated to them responsibility for

enforcing it. Section 4(b) of the statute expressly pre

cludes judicial review of findings of fact by the Attorney

General and the Director o f the Census made to deter

mine which jurisdictions are covered by the 1975 Amend

ments. This Court does not have jurisdiction to hear

8

petitioners’ constitutional argument because it was not

presented to a three-judge district court as required by

28 U.S.C. §2282.

The Attorney General’s construction of the 1975

Amendments implements a primary Congressional pur

pose, namely, the extension of the protections of the

Voting Rights Act of 1965 to minority voters in Texas.

The legislative history of the Amendments demonstrates

that Texas was among the jurisdictions Congress intended

to be covered by the preclearance and related provisions

of the 1965 Act. The legislative record reveals that

English-only elections, discriminatory enforcement of

registration and election laws, overt discrimination

against minority voters and candidates, and sophisticated

devices which dilute minority votes have combined to

exclude Mexican Americans and blacks from participa

tion in the Texas political system. Congress found that

these practices are strikingly similar to those which

existed in the South prior to the enactment of the Voting

Rights Act o f 1965. As in the South, case-by-case litiga

tion challenging voting discrimination in Texas has not

been effective; political jurisdictions intent on discrimina

tion have either ignored court decrees or evaded them by

adopting new but equally discriminatory practices. For

these reasons, Congress intended to extend the provisions

of the Voting Rights Act to Texas. Thus, petitioners’

arguments, which if accepted would exclude it from the

Act’ s coverage, should be rejected.

Extension o f the Voting Rights Act to Texas will help

to eliminate other forms o f discrimination. Mexican

Americans in Texas have long suffered discrimination in

education, housing, employment and law enforcement.

Congress recognized that these forms of discrimination

can best be eliminated by guaranteeing Mexican Ameri

cans the right to vote and an equal opportunity to partici

pate in the State’s political system.

9

ARGUMENT

I .

TEXAS’ ARGUMENTS REGARDING THE CONSTRUC

TION AND APPLICATION OF THE VOTING RIGHTS

ACT AMENDMENTS OF 1975 ARE WITHOUT MERIT.

Texas contends that the Attorney General miscon

strued the phrase “ test or device” as used in Section 4(b)

by failing to consider the factors set forth in Section 4(d)

relating to suits to terminate coverage. Brief for the Peti

tioners at 13-17 (hereinafter “ Pet. Br,” ). It also contends

that the Director of the Census misconstrued the phrase

“ such persons” as used in Section 4(b) to mean voting

age citizens rather than registered voters. Pet. Br. at 8-13.

As the Attorney General’s brief shows, judicial deci

sions and the legislative history o f Section 4(b) establish

that these arguments are without merit. The Attorney

General’s and Director of the Census’ construction of

Section 4(b) is especially important because Congress has

delegated to them responsibility for enforcing the Act.

This Court has stated that “ When faced with a problem

of statutory construction, this Court shows great defer

ence to the interpretation given the statute by the offi

cers or agency charged with its administration.” Udall v.

Tallman, 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965), rehearing denied, 380

U.S. 989 (1965).13 Such deference is particularly appro

priate where, as here, the enforcing agencies’ construction

of the statute is consistent with their prior practices. Traf-

ficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409 U.S. 205,

210 (1972); Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563, 571 (1974)

(Stewart, J., concurring).

Texas also contends that, assuming the Director of the

Census correctly construed Section 4(b), he improperly

D Accord, Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 433-34

(1971).

10

applied it in determining the number o f voting age citi

zens in the state by miscounting the number of non

citizens of voting age. Pet. Br. at 22-26. This argument,

however, disregards the last sentence of Section 4(b),

which states:

The determination or certification of the Attorney

General or o f the Director o f the Census under this

section . . . shall not be reviewable in any court and

shall be effective upon publication in the Federal

Register. [42 U.S.C. §1973b(b)].

In South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 322

(1966), this Court upheld the constitutionality of this

provision, and emphasized that it precludes judicial re

view of Census Bureau statistical findings like those Texas

now challenges.14

Finally, Texas argues that the principles of Younger v.

Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971), and related cases entitled it

to a predetermination hearing. Pet. Br. at 18-21, 26-28.

The Court o f Appeals properly rejected this argument

because it amounted to a constitutional challenge to the

Voting Rights Act which could only be heard by a three-

judge court pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2282. Briscoe v.

Levi, 535 F.2d 1259, 1265-66 (D.C. Cir. 1976).

Even if this Court had jurisdiction to hear petitioners’

constitutional challenge, it is important to note that the

cases Texas cites neither limit Congress’ authority under

14It should be noted that the scope of review issues presented

in this case are different than those presented in Morris v. Gres-

sette, prob. juris, noted, 45 U.S.L.W. 3407 (Dec. 6, 1976) (No.

75-1538). Morris involves issues regarding the scope o f review

o f Attorney General determinations pursuant to the preclearance

provisions o f Section 5, whereas this case involves initial coverage

determinations pursuant to Section 4(b). Section 5, unlike Section

4(b), does not in any way limit the scope o f judicial review.

11

the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to protect

the voting rights of racial and language minorities, nor

provide any basis for Texas’ assertion that it was entitled

to a predetermination hearing. For example, Younger v.

Harris, supra, involved the power of federal courts to

enjoin state court proceedings, and by its terms has no

applicability to situations where state court proceedings

are not pending. Steffel v. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452

(1974); Doran v. Salem Inn, Inc., 422 U.S. 922 (1975).

In National League o f Cities v. Usery, 96 S.Ct. 2465

(1976), upon which petitioners also rely, this Court held

that Congress may not wield its power under the Com

merce Clause to enact statutes which “ impair the States’

‘ability to function effectively within a federal system,’ ”

96 S.Ct. at 2474, so as to ‘ “ devour the essentials of state

sovereignty,” ’ 96 S.Ct. at 2476, unless, of course, “ the

federal interest is demonstrably greater” under a “ balan

cing approach.” 96 S.Ct. at 2476 (Blackman, J., con

curring). National League o f Cities has no appli

cability where, as here, Congress has exercised its

authority under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amend

ments to protect the voting rights of minorities in Texas

and elsewhere against well-documented, widespread

attack. This Court has held that the extension of similar

protections to black voters in the South does not un

constitutionally infringe state sovereignty. South Carolina

v. Katzenbach, supra. Moreover, twelve years of experi

ence since the enactment o f the Voting Rights Act

demonstrates conclusively that it has not “ impair [ed] the

[states’ ] ability to function effectively within a federal

system.” In fact, federal laws guaranteeing voting equal

ity preserve the federal system and protect the sover

eignty of the people.

Similarly, nothing in Rizzo v. Goode, 423 U.S. 362

(1976), affects the power of Congress to enact legislation

under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. That

12

decision merely overturned a federal court injunction

which this Court held ran against city officials who had

not themselves committed any constitutional violation.

Here, however, Congress has acted to protect the voting

rights o f Mexican Americans and other language minori

ties, and has limited the applicability of the statute to

those jurisdictions where severe voting discrimination has

been documented.

II.

CONGRESS INTENDED THE 1975 AMENDMENTS TO

EXTEND THE PROTECTIONS OF THE VOTING RIGHTS

ACT OF 1965 TO MEXICAN AMERICAN AND BLACK

VOTERS IN TEXAS.

It is a well accepted principle o f statutory construction

that courts interpret legislation to effectuate Congress’

intent. In United States v. American Trucking Associa

tion, 310 U.S. 534, 542 (1940), this Court held that, “ In

the interpretation o f statutes, the function of the courts

is easily stated. It is to construe the language so as to give

effect to the intent o f Congress.” 15

The legislative history of the 1975 Amendments

demonstrates that Congress intended to extend the pro

tections o f the 1965 Act to Mexican American voters in

the Southwest, and that it was particularly concerned

about widespread voting discrimination in Texas. The Re

port o f the House Judiciary Committee states:

The state o f Texas . . . has a substantial minority

population, comprised primarily o f Mexican Amer

icans and blacks. Evidence before the Subcommittee

documented that Texas also has a long history of dis

criminating against members o f both minority

15Accord., United States v. Alpers, 338 U.S. 680 (1950); Harri

son v. Northern Trust Co., 317 U.S. 476 (1943).

13

groups in ways similar to the myriad forms of dis

crimination practiced against blacks in the South. . . .

Outright exclusion and intimidation at the polls are

only two of the problems they face. . . .The central

problem documented is that of dilution of the vote

. . . . As one witness noted, ‘As the Mexican American

or Black voter appears to threaten potentially local

power structures, a wide variety of legal devices are

employed to intimidate, exclude and otherwise deny

voting rights to minority citizens.’ 16

The House Report further indicates that voter turnout in

Texas in recent Presidential elections has been below 50%

of the voting age population, and that “ the only reason

the state was not covered by the Voting Rights Act of

1965 or by the 1970 Amendments was that it has em

ployed restrictive devices other than a formal literacy re

quirement.” 17

The House Report,18 various tables included in the

record,19 and numerous statements during the Congres

sional debates20 indicate that Texas was among the juris

dictions Congress intended would be covered by Title II

of the 1975 Amendments.21 The House Report also

16H.R. Rep. 94-196 at 17-19. The Report of the Senate

Judiciary Committee on the Voting Rights Act Amendments of

1975 is virtually identical to the House Report. S. Rep. No.

94-295, 94th Cong., 1st Sess. (1975).

17H.R. Rep. 94-196 at 17.

18/d. at 24.

19E.g„ id, at 62-63.

20See, e.g., 121 Cong. Rec. (June 2, 1975) at 4712,jRemarks of

Cong. Edwards); Id. at 4746 (Remarks of Congresswoman Jordan).

21 The legislative record also indicates that Congress intended

Title II coverage to be triggered for the entire state of Alaska,

certain counties in California, and certain areas of Arizona, Florida,

Colorado, New Mexico, Oklahoma, New York, North Carolina,

South Dakota, Utah, Virginia and Hawaii. H.R. Rep. 94-196 at 24.

14

states that Congress intended to reserve Title II coverage

for those jurisdictions where “ severe voting discrimination

was documented.” 22 As shown below, the legislative

record contains extensive evidence of severe voting dis

crimination against Mexican Americans and blacks in

Texas. Thus, in order to effectuate Congress’ intent, as

well as for the reasons set forth in the Attorney General’s

brief, the arguments Texas makes, which if accepted

would exclude it from the coverage of Title II, should be

rejected.

III.

THE LEGISLATIVE RECORD ESTABLISHES THAT

MEXICAN AMERICANS AND BLACKS IN TEXAS HAVE

BEEN SUBJECTED TO SYSTEMATIC AND PERVASIVE

VOTING DISCRIMINATION.

The legislative record reveals voting discrimination in

Texas on a scale paralleling that which existed in the

South prior to the enactment of the 1965 Act. English-

only elections, discriminatory enforcement of registra

tion and election laws, overt discrimination against mi

nority voters and candidates, and sophisticated devices

which dilute minority votes have combined to exclude

Mexican Americans and blacks from participation in the

Texas political system. The record also demonstrates

that widespread voting discrimination persists in Texas

notwithstanding the fact that many discriminatory prac

tices have been invalidated by federal courts; like the

southern states, Texas has evaded the effect of court

orders by adopting new modes o f discrimination.

at 3. Title II incorporates the preclearance provisions of

Section 5, authorizes the employment of federal examiners and

observers by the Attorney General, and requires bilingual elections.

Title III of the 1975 Amendments, which applies in areas where

“ discrimination was less egregious,” merely requires bilingual elec

tions. Id.

15

A. English-only elections

The 2.2 million Mexican Americans in Texas comprise

approximately eighteen percent of the State’s population.

An estimated 50 percent of the Mexican American popu

lation speak only Spanish, and an estimated 90 percent

speak Spanish at home. Nevertheless, until 1975, Texas

printed all registration and other electoral materials, in

cluding ballots, in the English language only.24 To make

matters worse, Texas statutes long prohibited assistance

at the polls to Spanish speaking citizens and others illit

erate in English. In Garza v. Smith, 320 F. Supp. 131

(W.D. Tex. 1970), vacated and remanded for appeal to

the Fifth Circuit, 401 U.S. 1006 (1971), appeal dismissed

for lack o f jurisdiction, 450 F.2d 790 (5th Cir. 1971),

the court invalidated these statutes, stating:

We cannot perceive how exercise of the ‘ funda

mental right to vote,’ which Texas undeniably grants

to all illiterates who meet the qualifications pre

scribed by the state constitution, can be more than

an empty ritual if the right itself does not include

the right to be informed of the effect that a given

physical act of voting will produce. [320 F. Supp.

at 137] .

Despite the Garza decision and the fact that Texas stat

utes now require that assistance be given non-English

speaking and illiterate voters,25 election officials in a

number of Texas counties continue to refuse to provide

or allow it.26 Congressional witnesses testified that these

2^1975 House Hearings at 804.

2AId. at 806.

^T ex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 8.13 (1976-77 Supp.) (Vernon).

^United States Commission on Civil Rights, Staff Memoran

dum, Expansion of the Coverage of the Voting Rights Act, 21-23

[footnote continued]

16

practices have impaired the voting rights of Texas citizens

illiterate in English just as effectively as literacy tests long

abridged the voting rights of southern blacks.27 This

testimony is substantiated by federal court decisions

which have struck down English-only elections in areas

where substantial numbers o f non-English speaking voters

reside.28

Texas now argues that a newly enacted bilingual elec

tion statute29 has corrected the discriminatory impact of

(June 5, 1975), [hereafter “June 1975 CRC Staff Memorandum” ] ;

1975 House Hearings at 819. The June 1975 CRC Staff Memoran

dum was prepared at the request of Senator Tunney, Chairman of

the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Senate Judiciary

Committee.

27E.g., 1975 House Hearings at 78, 369, 806.

2%See, e.g., Arroyo v. Tucker, 372 F. Supp. 764 (E.D. Pa.

1974); Torres v. SACS, 73 Civ. 3921 (S.D.N.Y. July 25, 1974);

Puerto Rican Organization For Political Action v. Kusper, 350 F.

Supp. 606 (N.D. 111. 1972), aff’d,490 F.2d 575 (7th Cir. 1973). See

also New York v. United States, 419 U.S. 888 (1974), aff’g 65

F.R.D. 10 (D.D.C. 1974) (an election conducted only in English

where significant concentrations of Spanish speaking voters reside

is a discriminatory “ test or device” ). The discriminatory impact of

English-only elections in Texas is caused in part by the segregated

and unequal education provided Mexican Americans. Infra, at

46-47. In enacting the 1975 Amendments, Congress found that:

Citizens of language minorities . . . are from environments in

which the dominant language is other than English. In addi

tion they have been denied equal educational opportunities

by state and local governments, resulting in severe disabilities

and continuing illiteracy in the English language. 42 U.S.C.A.

§ 1973b(b)(l) (1976 Supp.).

The legislative record and judicial decisions establish that

these conditions are particularly serious in Texas. E.g., 1975 House

Hearings at 803-04, 864; Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Independent

School District, 324 F. Supp. 599 (S.D. Tex. 1970), aff’d in rele

vant part, 469 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) (en banc),cert, denied, 413

U.S. 920 (1973), rehearing denied, 414 U.S. 881 (1973). In <Gas-

ton County v. United States, 395 U.S. 285 (1969), this Court

recognized the relationship between education disparities and

voting discrimination.

79Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 1.08a (1976-77 Supp.) (Vernon).

17

English-only elections. Pet. Br. at 14. However, Congress

viewed the use of English-only elections as evidence of

prior discrimination requiring the application of the

Voting Rights Act. The fact that Texas now claims to

have ended English-only elections no more eliminates the

need for the application of the Act to it than the end of

literacy tests eliminated the need for the Act in the

South.

In any event, several witnesses testified that the bi

lingual election law was passed to dissuade Congress from

extending the Voting Rights Act to the state, 30 and as

drawn provides little if any assistance to Spanish speaking

voters. For example, Congresswoman Jordan testified that

the law exempts from its requirements 102 of Texas’ 254

counties and “ countless precincts within the remaining

counties if the precinct contains less than 5% of persons

of Spanish origin. Nobody knows how many Mexican

Americans are passed over by this exclusion.” 31 Con

gresswoman Jordan also emphasized that “ . . . more

importantly, by excluding precincts within counties from

coverage, local officials are provided an incentive to

gerrymander precinct lines . . . and thereby escape the re

quirement that bilingual ballots be provided.” 32

3(~* 1975 Senate Hearings at 457, 462-63, 913.

31Id. at 246.

32Id. By letter dated March 8, 1976, to the General Counsel for

the Secretary of State of Texas, the Attorney General indicated

that he would not object to implementation of the Texas bilingual

election law. The letter notes, however, that Section 4(f)(4) of the

Voting Rights Act applies to the entire State of Texas, and requires

that effective bilingual materials and assistance be provided at all

stages of the electoral process and within all Texas counties, “ in

cluding those that are allowed, but not mandated, to comply with

the provisions of the Texas bilingual election law.” Another

Congressional witness testified that subdivision 2(c)(3) of the

Texas Bilingual Election Statute:

[footnote continued]

18

B. Registration

The history o f registration in Texas provides stark evi

dence of systematic efforts to ignore and evade the effect

of judicial decrees entered to remedy voting discrimina

tion against Mexican Americans and blacks. The process

began several generations ago when it took five lawsuits

over a twenty-five year period to eliminate the white

primary.33 But those decisions did not end the State’s

effort to exclude minorities from the electoral process. In

1966, Texas was one o f the few states which still imposed

a poll tax. In United States v. Texas, 252 F. Supp. 234

(W.D. Tex.), aff’d per curiam, 384 U.S. 155 (1966), the

tax was invalidated;34 the district court found that the

tax had been enacted to disenfranchise minority citizens.

252 F. Supp. at 245.

In the wake o f this decision, the Texas legislature

enacted what one federal court has described as “ the

most restrictive voter registration procedures in the

nation. . . .” Graves v. Barnes I, 343 F. Supp. 704,

731 (W.D. T ex. 1972), affd in relevant part sub nom.,

White v. Reg ester, supra. This new law required

. . . provides that ballots can either be printed in bilingual

form or, at the decision of local officials, the election ma

terials could continue to be printed only in English if a trans

lation ballot were posted. . . .

. . . it is quite common to hold more than one election at the

same time — thus requiring the voter to consider as many as

three or more separate ballots. There was great concern on

the part o f the Mexican American leaders . . . that this post

ing alternative would only add to the confusion present on

Election Day. [1975 Senate Hearings at 456].

33Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927); Nixon v. Condon,

286 U.S. 73 (1932); Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U.S. 45 (1935);

Smith v. Allright, 321 U.S. 649 (1944); Terry v. Adams, 345 U.S.

461 (1953).

34See Harper v. Virginia Board o f Elections, 383 U.S. 663

(1966).

19

annual registration and prescribed a four-month registra

tion period ending nine months prior to November elec

tions.35 In Beare v. Smith, 321 F. Supp. 1100 (S.D. Tex.

1971), aff’d sub nom., Beare v. Briscoe, 498 F.2d 244

(5th Cir. 1974), these requirements were held to violate

the equal protection clause because they disenfranchised

over a million Texans otherwise qualified to vote. 321

F. Supp. at 1108. See also Graves v. Barnes I, supra.

Following Beare v. Smith, the Texas registration law

was again modified, this time to authorize an automatic

three-year registration renewal whenever a voter voted in

a state or county election.36 The law also required that

notice be sent to all persons whose registration was ex

piring, but witnesses testified that the reregistration

forms were in English only, and that a high proportion

of Mexican Americans were required to reregister because

past discrimination had inhibited them from voting.37

In 1975, after the Voting Rights Act was extended to

Texas, the state again amended its registration procedures

to require a purge of all currently registered voters.38

The purge was never implemented because the Attorney

General, acting pursuant to Section 5, objected on the

ground that it would have a discriminatory impact on

blacks and Mexican Americans. The letter of objection

states:

. . . We cannot conclude that the effect of the total

purge to initiate the reregistration program will not

be discriminatory in a prohibited way.

With regard to cognizable minority groups in Texas,

namely, blacks and Mexican Americans, a study of

35TEX. CONST, art. VI, §2 (V.A.T.C.) (1966); Tex. Elec.

Code Ann. art. 5.11a (Vernon).

36Tex. Elec. Code Ann. art. 5.18(b) (1975) (repealed).

37E.g., 1975 House Hearings at 806; 1975 Senate Hearings at

745.

38Texas Senate Bill 300 (1975).

20

their historical voting problems and a review of sta

tistical data, including that relating to literacy, dis

closed that a total voter registration purge under

existing circumstances may have a discriminatory

effect on their voting rights. Comments from in

terested parties as well as our own investigation,

indicate that a substantial number o f minority regis

trants may be confused, unable to comply with the

statutory registration requirements of Section 2, or

only able to comply with substantial difficulty.

Moreover, representations have been made to this

office that a requirement that everyone register

anew, on the heels o f registration difficulties experi

enced in the past, could cause significant frustration

and result in creating voting apathy among minority

citizens, thus, erasing the gains already accomplished

in registering minority voters.39

Finally, numerous witnesses testified that Mexican

Americans and blacks in Texas are subjected to discrim

inatory treatment by local registrars. The abuses de

scribed include failure to place the names of duly regis

tered minorities on the voting lists, unavailability of voter

registration applications for registration drives, refusals to

appoint minorities as deputy registrars,40 and discrimina

tory enforcement of residence requirements.41

39Letter of objection dated December 10, 1975.

40E.g., 1975 House Hearings at 854; 1975 Senate Hearings at

245, 767, 1004-1007. See also H.R. Rep. 94-196 at 16; June 1975

CRC Staff Memorandum at 21-24.

41E.g., 1975 Senate Hearings at 245-46, 947-49. Texas courts

have characterized residency as an “ elastic” concept which is

extremely difficult to define and dependent primarily upon the

intention o f the applicant. This “ elasticity,” coupled with the

presumption under Texas law that decisions of local officials

[footnote continued]

21

C. Discrimination at the polls

Civil Rights Commission reports and other testimony

document widespread physical and economic intimida

tion of minority voters. Again and again, witnesses indi

cated that official harassment and fear of economic

reprisals deter minority voting as well as registration in

Texas.42

Civil Rights Commission observers reported physical

intimidation and harassment of minority poll watchers

and voters, and instances of police officers making “ ex

cessive and unnecessary appearances” at predominantly

Mexican American precincts and threatening Mexican

American voters.43 After Mexican Americans in Pearsall

had conducted a drive to encourage absentee voting, the

sheriff “ went to the homes o f the Mexican Americans

who had voted or were going to vote absentee intimi

dating them by warning that they had to be out of the

area on election day. . . d’44 Law enforcement officers in

Pearsall have also frequented predominantly Mexican

American precincts and taken pictures of those voting.45

Other witnesses described economic intimidation of

minority voters, including threatened loss of jobs, credit,

and business.46 A telegram to the Department of Justice

from the Chairman of the Texas Advisory Committee to

will be overturned only if contestants meet a heavy burden of

proof, facilitates discriminatory application of registration require

ments. See Guerra v. Pena, 406 S.W.2d 769 (C.C.A. Tex. 1966).

^E .g ., 1975 House Hearings at 483-85, 521-23, 819-20,

853-56; 1975 Senate Hearings at 751-54; 967-71; H.R. Rep.

94-196 at 18.

43June 1975 CRC Staff Memorandum at 24-28.

441975 House Hearings at 522. See also 1975 Senate Hear

ings at 947.

45 1975 Senate Hearings at 948. See also Allee v. Medrano,

416 U.S. 802 (1974).

46E.g., 1975 House Hearings at 521-22.

22

the Civil Rights Commission stated that the Committee

had received complaints that “ voters have been eco

nomically intimidated by threats of financial loss for

failure to support certain candidates.” 47 48 The Civil Rights

Commission study o f Uvalde County reported that fear

of job loss and reduction o f welfare benefits is a major

J . . . 4Qdeterrent to Mexican American political participation. 0

Economic and physical intimidation of minority voters

is facilitated by certain features of Texas election law,

including the often unbridled discretion vested in local

officials. A former Texas Secretary o f State noted:

The underlying problem is economic or physical

intimidation at the local level o f minority voters

who are predominantly in lower income groups.

Texas statutes place all election duties upon local

officials. Even if the Secretary of State has access to

information concerning intimidation or improper

influence of a voter, the office has no statutory

authority to take even minimal action. In addition,

the [state] Attorney General can intervene only

where irregularities involve more than one coun

ty.49

Other witnesses testified that a Texas “ stub law”

which requires voters to sign a ballot stub facilitates elec

tion challenges which intimidate Mexican American and

black voters.50 The testimony describes the opening of

471975 House Hearings at 819.

48June 1975 CRC Staff Memorandum at 33.

491 9 75 Senate Hearings at 247-48. See also n. 41, supra.

50Texas Election Code Ann. Art. 8.15 requires that a voter sign

a ballot stub containing a serial number corresponding to the serial

number on the ballot. The stubs and ballots are deposited in

separate boxes. If an election is challenged both boxes may be

opened and the stubs used to trace ballots to the voters who cast

them.

23

ballot boxes, the subpoenaing of minority voters, and the

tracing of their votes followed by economic reprisals, all

of which have a chilling effect on minority political par

ticipation.51 In Pearsall, for example, a petition chal

lenging election results stated precisely the number of

votes being challenged and the reasons each vote was

allegedly invalid. Specific allegations of this type could

not have been made unless the ballot box had already

been opened. Approximately 200 Mexican American

voters were subpoenaed (no whites were subpoenaed),

and the challenged votes were ultimately declared in

valid.52 In the course of a similar election challenge in

Cotulla over 150 voters were subpoenaed, all of whom

were Mexican Americans.53 The discriminatory impact

of such election challenges was summarized during the

Congressional hearings:

The manner in which these investigations are carried

out as perceived by the Mexican American com

munities involved has the effect of discouraging

further registration and voting. The effect is intimi

dation—the result is fear of exercising the constitu

tionally guaranteed right to vote.54

The legislative record also indicates that the stub law

operates as a literacy test because it requires voters to

sign their ballot stubs. One witness described an election

won by a Mexican American candidate by 65 votes. The

results were challenged, the stub box opened, a deter

mination made that approximately 100 Mexican Ameri-

s lE.g., 1975 House Hearings at 363-64, 485, 521-22; 1975

Senate Hearings at 731-33, 946-49.

521975 Senate Hearings at 946-47.

E.g., id. at 948-49.

4̂ 1975 House Hearings at 404.

24

can voters had signed their stubs with an “ X ,” and the

opposing white candidate was declared elected.55

Official intimidation, harassment, and discrimination

infect all stages of the voting process in Texas. Election

officials in La Salle, Uvalde and Frio Counties denied

assistance to non-English speaking voters even after Texas

laws were amended to require it.56 Other witnesses de

scribed excessive demands for personal identification re

quired only o f Mexican American voters,57 challenges to

the residence of voters whom election officials felt might

vote for the Raza Unida candidate, harassment of Raza

Unida campaign workers even though they were working

the polls outside the distance markers,58 selective invali

dation o f ballots cast by minority voters, last minute un

announced changes in voting times and locations,59 and

the location of polling places in areas traditionally off-

limits to or inconvenient for minorities. For example, in

Jefferson County, which is approximately 25% black,

polling places were located in a rod and gun club which

had a totally white membership, and in a white school in

an all-white section of a precinct.60 In Villa Coronado,

voting officials refused to set up a polling place in a Mexi

can American neighborhood where 75% of the district’ s

551975 House Hearings at 732.

56Id. at 818.

57E.g., id. at 810, 820; 1975 Senate Hearings at 767-69.

5&E.g., 1975 House Hearings at 820; 1975 Senate Hearings at

741-43, 967-71. The Raza Unida party is one of three political

parties that Texas law officially recognizes. It is supported pre

dominantly by Mexican American voters.

5^1975 House Hearings at 810,860. See generally June 1975

CRC Staff Memorandum at 24-27.

6°June 1975 CRC Staff Memorandum at 26.

25

population resided, thus forcing those voters to travel

seven miles in order to cast their ballots.61

D. Discrimination against minority candidates

Mexican Americans and blacks in Texas have also been

denied an equal opportunity to run for elective office.

Until 1972, a filing fee discriminated against minority

candidates just as effectively as the poll tax discriminated

against minority voters. Over 35% of the Mexican Ameri

cans and blacks in Texas are impoverished.62 In Bullock

v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972), this Court invalidated

Texas’ filing fee system on the ground that it denied less

affluent citizens an equal opportunity to run for office.

Several courts on similar grounds have invalidated re

quirements that a candidate own real property within the

district in which he or she is running.63 In Pablo Puente

v. City o f Crystal City, Civ. Ac. No. DR-70-CA-4 (W.D.

Tex. April 3, 1970), the court found that a requirement

that city council members be property owners discrim

inated against Mexican Americans.64 Likewise in Graves

v. Barnes I, supra, the court found that the cost o f con-

611975 House Hearings at 856. See also 1975 Senate Hearings

at 947, where evidence was given that when the polling place in

Pearsall, Texas was located in the Mexican American part of town,

voting participation among Mexican Americans rose to the highest

levels ever; when the polling place was relocated in the white sec

tion of town, Mexican American participation dropped by 400

votes.

6~ Infra, at 47.

63E.g., Connerton v. Oliver, 333 F. Supp. 201 (S.D. Tex.

1971); Duncantell v. Houston, 333 F. Supp. 973 (S.D. Tex. 1971);

Gonzales v. Sinton, 319 F. Supp. 189 (S.D. Tex. 1970). See also

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970).

64 A Texas law that only persons who have rendered property

for taxation may vote in bond issue elections was invalidated in

Hill v. Stone, 421 U.S. 289 (1975), rehearing denied, 422 U.S.

1029 (1975).

26

ducting electoral campaigns in at-large state legislature

races in Bexar County was so excessive that it inhibited

the recruitment and nomination or election of Mexican

American candidates. 343 F. Supp. at 731.

The expense o f running in at-large elections is not the

only reason their widespread use throughout the state65

discriminates against minority candidates. One witness

testified that considerably fewer minority candidates

compete in the Demo era tic primary in at-large districts

because of a common sense realization that their pros

pects o f winning at-large races are slim.66

Testimony also established that in nine major Texas

counties studied, candidates most often were selected

either by slate-making groups, such as organized labor or

businessmen, or by a more informal process which re

quires the candidate to have access to social, business,

educational and professional associations.67 Minorities

have been denied access to both processes. In Graves v.

Barnes II, 378 F. Supp. 640, 649 (W.D. Tex. 1974) va

cated and remanded for determination o f mootness

sub nom. White v. Regester, 422 U.S. 935 (1975),

the court found that in Jefferson County endorse

ment by a local labor organization usually leads to

election, but that the local organization had never

slated a black man or woman. The court noted

“ When called upon to explain their lack of enthusiasm

for black candidates, the local labor leaders reported to

the state . . . [organization] and the local black com

munity that they would not support a black person

because o f the racial hostility of their predominantly

white membership.” 68

6^Infra, at 37.

661975 House Hearings at 436. See Graves v. Barnes I, supra, at

731-32.

671975 House Hearings at 436.

68The hearing record also describes a discriminatory tactic

adopted by the City Council of Uvalde, which met and decided in

27

The long and pervasive history of discrimination

against minority candidates by traditional, well-estab

lished political organizations has encouraged minorities to

establish new political parties.* 69 This development, how

ever, has not escaped the attention of Texas officials

intent on perpetuating discrimination against minority

candidates and voters. After American Party o f Texas v.

White, 415 U.S. 767 (1974), rehearing denied, 416 U.S.

1000 (1974), invalidated a Texas law which denied minor

party candidates a place on absentee ballots, a new law

was passed prohibiting minor political parties from hold

ing primary elections. Texas reimburses the costs of con

ducting primary elections, but not the costs of holding

conventions. The'Attorney General objected to this new

law because its impact would fall “ only on one party, the

Raza Unida party, and significantly limit the opportunity

for Mexican Americans to nominate, on an equal basis

with others, a candidate of their choice.” 70

There is also substantial evidence of racially based cam

paign tactics in Texas. In White v. Regester, supra, this

Court emphasized the district court’s finding that the Dal

las Committee for Responsible Government, a white

dominated organization that effectively controls Demo

cratic party slating in Dallas County, had as recently as

1970 relied upon “ racial campaign tactics in white pre

secret not to put on the ballot the name of a duly qualified Chi-

cano candidate for the Council. The candidate filed an action in

state court. The court found that his constitutional rights had been

violated. 1975 House Hearings at 854. See also Garcia v. Carpenter,

525 S.W.2d 160 (Tex. Sup. Ct. 1975) (arbitrary refusal to place

Mexican American candidate’s name on the ballot as a candidate

for mayor).

69See Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968). See generally

Mazmanian, Third Parties in Presidential Elections (1974).

70Letter of objection dated January 23, 1976.

28

cincts to defeat candidates who had the overwhelming

support o f the black community.” 412 U.S. at 767. One

Congressional witness described thirty-second spots on

Spanish radio stations which warned Mexican American

voters that if they did not comply with all election laws,

they could be sent to jail or fined $500.71 Another wit

ness said that racial campaigning was evident in nine

major Texas counties studied, and that such campaigning

is particularly discriminatory given racially polarized

voting patterns in at-large election districts.72

Finally, the Civil Rights Commission advised Congress

that it found economic and physical intimidation of

minority candidates in Texas. One candidate who re

ported that he had suffered harassment on the job told a

Commission interviewer:

“ . . . you see why we have such a difficult time even

convincing some Chicanos to file for office, the fear

for their jobs, fear of all kinds of pressure.” 73

E. Dilution of minority votes

The hearing record also documents continuous efforts

by Texas officials to subject minority voters and candi

dates to “ sophisticated” discriminatory devices such as

malapportionment, gerrymandering, at-large elections,

majority runoff requirements and the place system, all of

which dilute the value of the vote. The House Judiciary

Committee concluded that blatant intimidation and other

7^1975 House Hearings at 806.

12Id. at 454-55.

73 1975 Senate Hearings at 999. See generally United States

Commission on Civil Rights, Staff Memorandum, Summary of Pre

liminary Research on the Problems o f Participation by Spanish

Speaking Voters in the Electoral Process, April 23, 1975. Num

erous witnesses described many instances o f outright intimidation

of minority candidates. E.g., 1975 House Hearings at 521, 826-27,

854, 861; 1975 Senate Hearings at 735, 753-56, 774.

29

forms o f discrimination against Mexican American and

black voters in Texas

are not the only barriers obstructing equal oppor

tunity for political participation . . . The central

problem documented is that o f dilution of the vote

-arrangements by which the vote of minority elec

tors are made to count less than the votes of the

majority. 74

1. Malapportionment and gerrymandering

The record is replete with descriptions of malappor-

tioned or gerrymandered electoral districts in Texas. 5 In

1969 and again in 1974 the Commissioners Court in

Anderson County reapportioned and redistricted the

county’s four precincts.76 In Robinson v. Commissioners

Court, Anderson County, Civ. Ac. No. TY-CA-73-236

(E.D. Tex. March 15, 1974, affd in relevant part, 505

F.2d 674 (5th Cir. 1974), 77 the district court held that

“ Since the Commissioners Court did not rely on available

1970 census data in effecting the modification of the

precinct lines, but rather placed exclusive reliance upon

voting registration figures, the reapportionment is dis

torted.” The court also found that the realignment fol