Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

Public Court Documents

August 29, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Brief for Petitioner-Appellant, 1983. 8c37a796-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10a1fe7a-15ec-4c65-a832-95739370f704/brief-for-petitioner-appellant. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

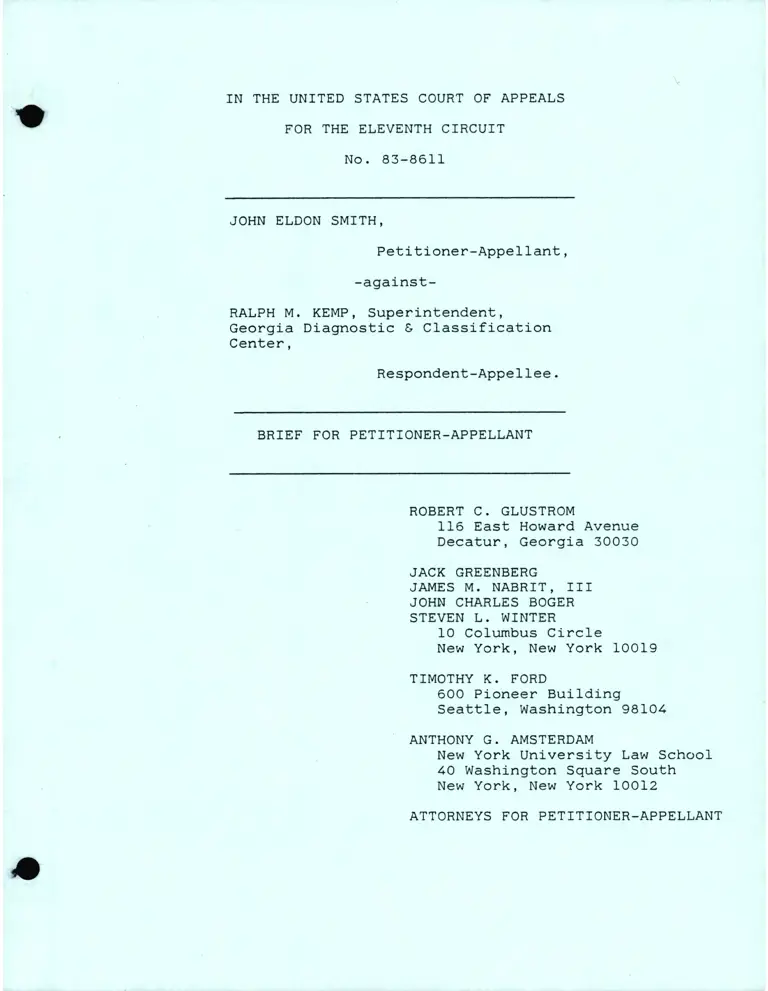

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 83-8611

JOHN ELDON SMITH,

Petitioner-Appe 1 1 ant,

-against-

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgla Dlagnostic & Classificatton

Center,

Respondent-AppeIlee .

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

ROBERT C. GLUSTROM

116 East Howard Avenue

Decatur, Georgia 30030

JACK GREENBERG

JAIVIES M. NABRIT, III

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

STEVEN L. WINTER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T MOTHY K. FORD

600 Pioneer Bullding

Seattle, Washington 98104

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

New York Untverslty Law School

40 Washlngton Square South

New York, New York 1OO12

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

STATEMENT REGARDTNG PREFERENCE

This is an appeal from the denial of habeas corpus

relief sought under 28 U.S.C. $$zZaf-2251 from the judgment

of a state court. This appeal should be given preference in

processing and dlsposition pursuant to Rule 12 and Appendix

One (a)(S) of the Rules of this Court. In its letter to

counsel of August 25,1983, the Court has indicated lts lnten-

tlon to process this case under the expedited procedures out-

lined in Barefoot v. Este11e, u.s. ,51 u.s.L.w.5189

(u.s., June 28, 1983) (mo. 82-6080).

STATEMENT REGARDING

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Fl(.LT ]iltLNUT- I

1V

Page

20

STATEMENT

STATEMENT

OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

OF THE CASE

( i ) Course of Prior Proceedings

( fi ) Statement of Facts

( ii.i ) Standard of Review

SUMW\NY OF ARGUMENT

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

ARGUMENT

11

l2

I. The Dlstrict Court Erred (f) In

Applying 52251(d) Presumptions Of

Correctness To State Factfindlngs,

And ( il ) In Denying Petitioner A

Federal Evidentiary Hearing On His

Giglio v. Unlted States C1aim, When

Tne State Hearing Had Not Been Fu1I

And Fair, And Had Been Marred By

Extraneous, Intimldating Pressures

Brought To Bear On A Key Witness

The District Court Misunderstood

The Factual Record And Thus Failed

To Consider Or Resolve Petitioner's

Uncontradicted CIaim That The State

Had Concealed From Petitioner's Jury

A Material Threat By Which It Induced

Key Testimony Against Petitioner

The Dlstrict Court Erred By Applying

Res Judicata And Walver Principles To

ffie?frGffiether Petitioner' s

Arbitrariness,/Raci-a1 Di scriminatlon

Clalms, Reasserted Promptly Upon The

Receipt Of Newly Available Evidence,

Should Be Entertalned By The Federal

Courts

L2

II.

III.

L1

IV. The District Court Erred By

Rejecting Petitioner's Merltorious

Jury Claim Without Affording Him

A Reasonable Opportunity To

Demonstrate "Cause" And "Prejudice"

Under Federal Standards For Counsel's

Failure To Assert It Earlier 35

CONCLUSION.. 12

l- l- l_

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

*Alcorta v. Texas, 355 U.S. 28 (1957)....

Alvarez v. Estelle, 531 F.2d 1319 (5th Cir. t976)....

Baldwin v. Blackkrurn, 635 F.2d 942 (5th Cir. 1981I . . .

Barefoot v. Estelle, U. S. ,51 U.S.L.W.5189(u.s. June 28, rg'E3) (No. tr0080).

Barr v. City of Co1umbia, 378 U.S. 146 (1964) ........

Blanton v. Blackburn, 494 F. Supp. 895 (M.D. La. 1980)

aff,'d, 654 F.2d 718 (5th Cir. 1981)..

Boone v. Paderick, 541 F.2d 447 (4th Cir. 1976)

Chambers v. Mississippi, 410 U.S. 284 (1973)

Cuyler v. Su11ivan, 446 U.S. 335 (1980)

Duren v. Missouri, 439 U.S. 357 (1979 )....

Page

22

8

36, 39

8,38, 39

I9

38

37

13,39

40

215,7 ,g rl2r20 r2L

23 ,24

28

1

20 ,27

30

38

8

].

4l

22

22

Engle v. Isaac, 456 U.S. 107 (1982)

Estes v. Texas,381 U.S.532 (1965)

Fay v. Noia , 37 2 U. S. 301 ( 1963 )

Fletcher v. Beto, 431 F.2d 575 (5th Cir.

Francj-s v. Henderson, 425 U.S. 536 (1976)

t970).......

Galtieri v. Wainwright, 582 F.2d 348 (5th Cir.

1978)(en banc)....

*Giglio v. United States, 405 U.S. 150 (197il.

Goodwin v. Balkcom, 684 E.2d 794 (IIth Cir. l9B2),

cert. denied, U. S. , 16 L.Ed. 2d

Golns v. A119ood, 391 F.2d 692 (5rh Cir. 1968)

Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95 (1979 )....

*Guice v. Fortenbexyy, 661 F.2d 496 (5th Cir.

1981) (en banc)....

Hardwi-ck v. Doolittle, 558 F. 2d 292 (5th Cir.

1977l' , cert. denied, 434 U.S. 1039 (1978).......

36

1V

Jackson v. Virginia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979 )....

Jiminez v. Estel 1e, 557 F.2d 506 ( 5th Cir. 1977 ) . . . . .

Jurek v. Este1Ie, 623 F.2d 929 (5th Cir. 1980),

cert. denied, 450 U.S. 1011 (1981)....

*I4achetti v. Lina

cert. denied

@-

han, 679 F.2d 236 (11th Cir. 1982)

, u.s. , 74 L.Ed. 2d g7g

Page

I ,28

39

8.

10 , 35 ,38 ,41

36

25,34

29,30

8 ,26 , 28 ,30 ,34 ,37

8,30 ,31,33,37

28

26

8,10 ,26,29,29,3L,3:

3/* r36

19

5,25r31

1.

/.

/*

4

5

29

Marks v. Este11e, 591 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1982)

*l,lcC1eskey v. Zant, No. C8l-2434A (N.D. Ga. )

*Paprskar v. Estel1e, 612 F.2d 1003 (5th Cir.

*Potts v. Zant, 638 F.2d 727 (5th Cir. 1981),

1980)..

cert.

deni-ed, 454 U.S. 877 (1982)

*Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266 (1948)....

Rose v. t"litcheI1, 443 U.S. 545 (1979 ) .. . .

Salinger v. Loisel, 265 U.S. 224 (1914)....

*Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. I (1963).

Sheppard v. Maxwell, 384 U.S. 333 (1965)....

Simpson v. Wainwright, 48B F.2d 494 (5th Cir. 1973)..

Sincox v. Este1le, 571 F.2d 876 (5th Cir. 1978 ) .. . . . .

Smith v. Balkcom, U. S. , 103 S.Cr. 181 (1982)

Smith v. Balkcom, 660 F.2d 573 (5th Cir. 1981),

modified, 671 F.2d 858 (1982)....

Smith v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 910 (1976)....

Smith v. Hopper, 436 U.S. 884 (1978)....

Smj-th v. Hopper , 240 Ga. 93 , 239 S.E.2d 510 (19771 . . .

Smith v. State, 236 Ga. 12, 222 S.E.2d 308 (1976) ....

Smith v. Zant, 250 Ga. 645, 301 S.E.2d 32 (1983).....

Spinkellink v. Wainwright, 528 F.2d 582 (5th

Cir. 1978) ....

30

39

5

v

Spivey v. Zant, 661 F.2d 464 (5th Cir. 1981), cert.

denied, U.S, , 73 L.Ed. 2d 1374

@)-.._. _.

Stewart v. Ricketts, 451 F. Supp. 911 (M.D. Ga.

r978)

Stone v. Powel1, 428 U.S. 465 (1976)....

Sumna v. I{ata (I I ) , 455 U. S. 591 (I982 ) (per

curiam)

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 ( 1975) . . . .

*Thomas v. Zant, 697 F.2d 977 (lIth Cir. 1983) ......

*Townsend v. Sain, 37 2 U.S. 293 (1963)....

United States v. Ivy, 644 F.2d 479 (5th Cir. 1981)..

United States v. Sanfilippo, 564 F.2d 176 (5th

Cir. 1977 ) ....

United States v. Sutton, 542 F.2d 1239 (4th Cir.

t916 ) ....

*Vaughan v. EstelIe, 671 F.2d L52 (5t.h Cir. 1982) ...

In re Wainwright, 67 I F.2d 951 (IIth Cir. 1982).....

Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72 (1977 )....

Vlaley v. Johnston, 316 U.S. 101 (1942) ....

Page

28

38

27

13

37 , /+O

19, 33 , 37

I, g, L3 r27 ,31

37

22,23,24

9,2!

32,36

19,27

8 , 10 ,27 ,38 , /"! ,12

26

Statutes

28 U.S.C. 52241 ...

28 U.S.C. S2254 (d)

Ga. Code Ann. 550-127 (11

i

L2,13

40

vl

rN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 83-8611

JOHN ELDON SMTTH,

Peti t j. oner-Appe I 1 ant,

-against-

RALPH M. KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagrnostlc E Classification

Center,

Respondent-Appe1lee.

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Can petitioner's state postconviction hearing be

deemed "fuII and fair" under Townsend v. Sain,372 U.S. 293 (1963)

when relevant evidence was excluded and extraneous pressure and

1ega1 intimidation were brought to bear on a key witness who had

previously given sworn testi-mony favorable to petitioner?

2. Was the admission in a public meeting by a now-

deceased assistant district attorney who participated in pre-

trial discussions with a key witness against petitioner and who

assisted in petit j.one_r's prosecution t.hat it was

"necessary" to give that key witness life lmprisonment in exchange

for his testimony, admissible and relevant evidence in this capital

proceeding under Georgia law, under the Federal Rules of Evidence

and/or under federal constitutional princi-ples outllned in such

cases as Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95 (lgZg) or Chambers v.

Mississippi , /*LO U.S. 284 (L973)?

3. Should petitloner have been afforded access to the

parole fj-Ie of John Maree, the key witness agalnst him at trial,

to determine whether that file contained evidence directly relat-

ing to, or like1y to lead to the dj-scovery of,other evidence re-

flective of the pretrial agreement or understandlng that forms

one princlpal foundation of petitioner's Giglio claim?

4. Does the evidence in the state court record viewed

as a whole -- principally the self-serving statements of an

admitted murderer seeking parole and the recantations of an

attorney facing bar discipllnary charges because of his prior

sworn statements support the finding that John Maree made no

promises in exchange for his trial testi-mony against petitioner?

5. Did the State's statements to John Maree and his

attorney that Maree would be tried fi-rst and that a death sentence

would "most likely" be sought against him unless he testified

against petitioner, but that dispositlon of his case would be

left open if he did testify, constitute a sufficient inducement

or understanding to requlre disclosure to petitioner's jury in

light of Maree's testimony on cross-examination and the District

Attorney' s closlng argument?

6. Can "abuse of the writ" under Rule 9(b), whether

viewed as inexcusable neglect or as deliberate bypass, be found

in the failure of an indigent petitioner to present complex and

comprehensl ve social scientific evidence during his initial

state and federal habeas proceedings in L976 or L979 respectlvely,

which was indisputably not available to him or to counsel until

mid-L982?

2

7. Was petitioner entitled, dt a minimum, to a federal

evidentj-ary hearing on whether his reassertion of his arbitrari-

ness/racial dj-scrimination claims constituted an abuse of the writ

under RuIe 9(b)?

8. Can the undisputed allegations of petitloner's

trial attorneys that they lacked any knowledge of a Supreme Court

case decided only six days prior to petitioner's trial constitute

"cause" for their fallure to assert a challenge to a Georgia statute

later shown to be unconstitutlonal?

9. Can a state court constitutionally choose to enforce

its contemporaneous objection statute and refuse to adjudicate the

claim of one of two similarly sltuated co-indictees, while adjudicating

the other on its merits, where the result might be to permit peti-

tioner's co-j-ndictee to receive a new trial and petitioner, tried

from the same unconstitutionally comprised jury pool, to be

executed?

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

(i) Cp,rrEe_ qf Prior Proceg!!.ngs

Petitioner was convicted of two counts of murder in

the Superior Court of Bibb County, Georgia on January 30, 1975.

The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed petitioner's conviction

and sentences on January 6,1976 in Smith v. State, 236 Ga. 12,

222 S.E.2d 3O8 (1976). The Supreme Court of the United States

denled a petition for certiorari on July 6, L976. Smith v.

Georgia, 128 U.S. 91O (1976). A timely petition for rehearing

was denied on October 4, 1976. Smith v. Georgia, 429 U.S. 87/*

(1e76).

On October 22, L976, petitioner filed a petition for a

writ of habeas corpus in the Superior Court of Tattnall County,

Georgia. That court entered an unpublished order on March 16,

1977, dismissing the petition. The Supreme Court of Georgia

affirmed on October 18, L977 in Smith v. Hopper, 21O Ga. 93,

239 S.E.2d 5tO (L977). The Supreme Court of the United States

denled a petition for certiorari on June 5, 1978. Smith v.

Hopper, 436 U.S. 95O (1978). A tlmely petition for rehearing

was denied on October 2, 1978. Smith v. Hopper, 439 U.S. 884

(re78).

Petitioner then filed a petition for a writ of habeas

corpus in the United States District Court for the Middle District

of Georgia, Macon Division, oo February 2L, 1979. The District

Court referred the case to a United States lvlagistrate, who entered

4

proposed findings of facts and conclusions of law on September

9, 1980, recommending a denial of all relief. The District Court

thereafter denied rellef on November 26, 1980 in an unreported

order and judgment.

This Court affirmed on November 2, 1981 in Smith v.

Balkcom, 660 F.2d 573 (stfr cir. Unit B 1981). The opinion was

modifled on rehearing

Supreme Court of the

on October 5, 1982.

(1es2).

, 67 I F.2d 858 ( Strr Cir. Unit B 1982 ) . The

United States denied a petition for certlorari

Smlth v. Balkcom, U.S. , IO3 S.Ct. 181

On June 25, 1-982, while his federal appeal was pending,

petitloner filed a successive petition for a writ of habeas corpus

in the Superior Court of Butts County, raislng three newly avaj-1abIe

federal constitutional claims. The Superior Court immediately

dismissed the writ without fulI consideration of the merits. Peti-

tioner appealed to the Georgia Supreme Court which, oh September

16, L982, entered an unpublished order remanding the case for an

"evldentiary hearing on the issues raised in the Petition. "

On remand, after a brief hearing on waiver issues, the

Superior Court entered an unpublished order on November 15, L982,

denying petitioner an evidentJ-ary heari-ng on the merits of his

constitutional clai.ms and dismlssing them both as successlve and

as waived under o.C.c.A. Sg-t+-sI (Michie 19s2). The Georgia

Supreme Court reversed on March I, 1983, and aga5-n remanded the

case to the Superior Court, directing an evidentiary hearing on

petltioner's prosecutorlal mlsconduct claim under Glglio v. United

states , 4o5 u.s. 15o (1972) . Smith v. Zant, 25O Ga. 645, 301 S.E.

2d 32 (1e83).

J

The Superior Court held an evidentiary hearing on May

10 and June 10, 1983. On August 5, 1983, the Superior Court

entered an unpublished order denying relief. The Supreme Court

of Georgia denied an applicatlon for a certificate of probable

cause to appeal in a per curiam order entered August f6, 1983.

On August L7 , 1983, petitioner filed a petition for a

writ of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Georgia, Macon Division. The Court entertained

oral argument from counsel on the petition the same day. On

August 18, 1983, petitioner filed a motion for an evidentiary

hearing. On August 19, 1983, the District Court entered one

order denying the motlon for an evidentiary hearing and a second

order dismissing the petition, denying a certificate of probable

cause, denying leave to proceed in forma pauperis, and denying a

stay of execution pending appeal.

Petitj-oner filed a notice of appeal on August 19, 1983,

and filed in this Court, oo August 22, 1983, dh appli-cation for a

certificate of probable cause to appeal, Eh applicatlon for leave

to proceed in forma pauperls and for a certificate of good falth,

and an application for a stay of execution. This Court heard oral

argument from counsel on August 23, 1983 and lssued an order later

on August 23rd, grantlng a certificate of probable cause to appeal,

leave to proceed in forma pauperis, and a stay of execution.

Respondent applied on August 24, 1983 to the Hon. Lewis

F. Powell, Jr., Associate Justice of the Supreme Court and Circult

Justice for the Eleventh Circuit, seeking to vacate this Court's

order of August 23, 1983. Justice Powell entered an order on

6

August 24th declining to vacate this Court's order. Kemp v. Smith,

A.- ,_U.S._ (August 24, 1983).

In a letter to counsel dated August 25, 1983, this Court

solicited any further briefings or other materials by August 29,

1983. Thls brief is submltted pursuant to that letter.

( ii ) Statement of Facts

A detailed statement of those facts most relevant to

petitioner's constitutional claims is set forth in Petitloner's

Memorandum of Law in Support of his Application for Certificate

of Probable Cause, a Stay of Execution, and for Leave to Proceed

fn Forma Pauperis (hereinafter "Pet. Mem."), filed in this Court

on August 23, 1983. (See Pet. Mem., 3-23). In view of counsel's

desire not to burden the Court with needlessly repetitive written

submissions, and in light of the Court's letter of August 25,

1983 relaxing the normal rules governing the form of briefi.g,

petitioner incorporates his prior statement of facts fully by

reference. Additional facts will be referred to as necessary

during the course of petitioner's argument.

( iii ) Standard of Review

(a) Petiti.oner's contentions related to his federal

constitutional claims under GlgIio v. United States , /,O5 U.S.

(Lg72) , including his "orra. u court did

not afford him a full and fair hearing,(ii) that the state court's

findings are not supported by the record, (iii) that he was entitled

to a federal evldentiary heari.g, and (iv) that the uncontradicted

record facts, misread by the District Court, make out a violation

of the Due Process Clause, dI1 involve questions of federal law or

7

mixed questions of fact and Iaw, on which this Court must

ently reassess the application of federal 1aw to the facts

See, e.g., Cuy1er v. Sulllvan, /*46 U.S. 335, 31*l-12 (1980)

independ-

of record.

; Jackson

v. Virqinia, 44.3 U.S. 3O7, 318 (1979); Jurek v. Estel1e, 623 F.2d

-

929, 931--32 (Sth Cir. 1980)(en banc), cert. denied, 45O U.S. 10Il

(1s81).

(b) Petitioner's contentions related to his arbi-trariness/

racial dj.scrimination clalms require this Court independently to

reassess the applicatlon of federal habeas corpus law to the prion

record. See, e.g,-, Sanders v. Unlted States, 373 U.S. I (1963);

Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266 (1948); Potts v.. Zant, 638 F.2d 727

(5th Cir. 1981), cert. denied, 454 U.S. 877 (1982)

(c) ,Petitioner's contentions related to his jury claims

requ].re

federal

v. Isaac

this Court independently to reassess the application of

habeas corpus law to the prior record. See, e.g., Engle

, 456 U.S. LO7 (1982); Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72

(L977); Baldwin v. Blackburn, 635 F.2d 942 (stn Cir. 1981).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The District Attorney's failure to reveal to petitioner's

trial jury certain inducements given for the testimony of a key wit-

ness, even after the witness gave misleading testimony to peti-

tioner's jury concernlng his motivation for testifying, vj-olated

petitioner's rlghts to due process established by Giglio v. United

States, 4o5 U.S. 150 (L972). The District Court erred first by

refusing to hold an evidentiary hearing concerning one of these

lnducements a pretrial understanding that the witness would

8

receive life sentences in exchange for his testimony and then

by applying a "presumption of correctness" to state factfindings

based upon a state evidenti-ary hearing that did not meet 28 U.S.C.

$2254(d) standards. Because the state court had excluded relevant

evidence sought by petitloner, and because the state court had

permitted the persistent intrusion of bar disciplinary concerns

to shape and influence the state hearing, the District Court

should have rejected any "presumption of correctness" and instead

have held the fu1I and fair evidentlary hearing to which peti-

tioner was entitled under Townsend v. Saj.n, 372 U.S. 293 (1963).

The District Court also erred by misreadlng the state

court record, overlooking the factual predicate for petitioner's

second Giglio claim -- that the key witness against petitloner

was lnduced to testify by the District Attorney's threats that,

otherwise, he would be tried before petitioner and might receive

a death sentence. Since under Giglio, there is "no difference

between concealment of a promlse of leniency and concealment of

a threat to prosecute," United States v. Sutton, 5/"2 F.2d 1239,

L242 (qtn Cir. 1976), this inducement should not have been con-

cealed by the witness when pressed on cross-examlnation by defense

counsel, nor should the District Attorney have furthered the mis-

lmpression given petitioner's jury during his closing argument.

The District Court apparently applied the wrong legal

standard ln summarily rejecting petitioner's constitutional claim

that Georgia is imposing capital sentences in an unconstitutionally

arbitrary and racially discriminatory pattern. Res judicata

principles do not bar relitigation of issues on federal habeas,

and the principles codified under Rule 9(b), prohibiting "abuse

-9

of the writ, " do not apply to one, such as petitioner, who can

demonstrate either that his claim has never been fulIy liti-gated

and determlned on the merits or, at a minlmum, that he now has

newly available evidence in support of his claims, and that

neither inexcusable neglect ror deliberate bypass explain his

inability to offer this evidence during earlier habeas proceed-

ings. See Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963). If the

District Court entertalned any doubt as to whether petitioner had

abused the writ, it was obligated to afford him a fair heari-ng,

on notice, to rebut any charge of abuse.

The District Court also erred in dismissi-ng peti-tioner's

clearly merltorj-ous claim of jury dlscrimlnatlon, see Machetti v.

Lj-nahan, 679 F.2d 236 (1llth Cir. 1982), on grounds of waiver,

without permitting petitioner a reasonable opportunity to demonstrate

"cause" for his failure to comply with state procedural rules and

"prejudice" resulting from the constitutional violation. In fact,

petitioner can readily demonstrate that the "cause" was an un-

anticipated change in the law which was not known to petitioner's

trial attorneys. Moreover, in view of the Georgia court's incon-

slstent enforcement of its procedural rules in this case and that

of petitioner's co-indictee, comity does not require the federal

courts to honor Georgia's claim of waiver. FinalIy, even the

Supreme Court's opinion in Walnwright v. Sykes, /*33 U.S. 72 (L977),

which first mandated compliance with state waiver rules in the

interest of federalism and comity, indicated that no "cause"-or

,"prejudice" need be proven if there would otherwise be a "mis-

carriage of justice." Because petj-tioner's jury pool was clearly

10

unconstitutional, because his capitally sentenced co-indictee

had already received a new trial on that ground, itwould be a

miscarriage of justice arbitrarily to enforce a state procedural

rule to deny petitioner relief here.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

Petitioner appeals to this Court, pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

52253, from a final order and judgment fo the United States Dlstrict

Court for the Middle Dlstrict of Georgia, Macon Dlvision, entered

August 19, 1983. This Court granted a certificate of probable

cause to appeal on August 23, 1983.

11

ARGUMENT

Petitioner has already submitted a memorandum of law

to this Court in support of his applications for a certificate

of probable cause, for a stay of execution, and for leave to

appeal in forma pauperis. That memorandum has addressed at

some length the merits of petitioner's three principal claims

with a view to establishing that they demonstrate serious constl-

tutional deficiencies in the conduct of his state trial. To avoid

unnecessary repetition, as in hls Statement of Facts, supra, peti-

tioner i-ncorporates those arguments here by reference. The

additional arguments in this brief will be addressed principally

to those 1ega1 errors made by the Dlstrict Court 1n its resolutj-on

of petitioner's claims.

I

THE DTSTRICT COURT ERRED ( i ) IN APPLYTNG

S2254(d) PRESUMPTIoNS oF CoRRECTNESS To

STATE FACTFINDINGS, AND (ii) TN DENYING

PETTTIONER A FEDERAL EVIDENTIARY HEARING

ON HIS GIGLIO V. UNITED STATES CLAIM,

WHEN TH BEEN FULL

AND FAIR, AND HAD BEEN MARRED BY EXTRANEOUS,

TNTIMIDATTNG PRESSURES BROUGHT TO BEAR ON

A KEY WTTNESS

Petitioner maintains that the District Attorney who

prosecuted him shared a pretrial understanding with a key eyewitness,

undisclosed to petitioner's jury, which helped to i-nduce his testi-

mony against petitioner. (See Pet. Mem., 3-15, 24-4L). The

Attorney General disagrees, urging that the state Superior Court's

"findings of fact and conclusions of law are entitled to the pre-

sumption of correctness under 28 U,S.C. $ZzSl(d)." Section 2254(d)

-L2

presumptions, of course, even if applicable, would not extend to

the ultimate 1ega1 issues, which must be addressed and resolved

under federal standards by this Court. Sumner itself made clear

this distinctlon:

"The ultimate [issue] is a mixed

question of law and fact that is not

governed by $Zzsl. In decidj-ng this

questlon, the federal court may give

different weight to the facts as found

by the state court and may reach a

different conclusion in light of the

1egal standard. "

Sumner v. Mata (rI), /*55 U.S. 591, s97 (fgez) (per curiam).

The only required deference is thus to state findings

of hlstorical fact -- if none of the statutory exceptlons to S2254(d)

apply and if the District Court has properly chosen not to

exercise its plenary power, E, U,., Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S.

293, 3LL-1,2 (1963); Francis v. Henderson, 425 U.S. 536, 538-39

(1976), to try the facts anew. fn this case, petitioner presented

to the District Court three reasons why 52254(d)'s presumptions

should not apply: (i) that the fact-finding procedure employed

by the state court was not adequate to afford a full and fair

hearing ($zzs+(d)(z)); (ii) that the material facts were not

adequately developed at the state hearlng ($ZZSI(d)(3)); and

( iii ) that the applicant did not receive a fu1l, fair and adequate

hearing in the state court proceedings ($ZZSI-(d) (6) ) (pea. Arg.,

L/

at 70) .- In support of the first two grounds, petltioner pointed

l/ Each reference to

Eounsel to the United

will be indicated by

the transcrlpt

States District

the abbreviation

of the oral arqument of

Court, held August L7 , 1983,

"Fed. Arg. ".

I3

to the state court's 'refusal to admit testimony indicating that

the Assistant District Attorney involved in petitj-oner's trial

had later admitted the "necessity" of giving the State's witness

a life sentence to obtain his testimony against petitioner (Fed.

Arg. , L2-L7; see Pet. Mem., 15-16, 31-35). The second inadequacy

was the state court's refusal to give petitioner access to the

parole file of State's wj-tness John Maree, even though the file

may welI have contained evidence of a pretrial understanding, or

may have led counsel, famillar with all the facts, to such evidence

2/

( ped. Arg. , 7O-72; see Pet. Mem. 16 , 36-37 ) .-

whlch

became

state

The final inadequacy of the state proceedings, one

was systemic and not isolated, was the extent to whj-ch they

transformed by the precipitous filing and prosecutj-on of

3/

bar charges against Fred Hasty,- into a defense of Mr,

2/ The District Court did order that the Maree file be produced

For lnspection in camera and be sealed as part of the record. in

this case. CouEe]Ilffiot be conf ident, however, that an in camera

inspection by a District Court whose total exposure to ttri-s issr:e

exceeded no more than three days could permit assessment of prob'a- -

tive value to petitioner's case of the contents of such a fi1e.

3/ The response filed by Mr. Hasty to the bar charges indicate

that the actions against hlm were plainly barred by Georgia's four-

year statute of Iimitations on dlsci-plinary proceedings. ( See

Transcript of May 10, 1983 Hearing, Resp. Ex. 3, at 143-4/*; Pet.

Ex. L4, at 2A6.)

-L4

Hasty's case, not a measured and orderly review of petitioner's

consti-tutional cIai.ms. The frequent interjections of Hasty's

retained counsel underlined the evident cross-purposes of the

hearing:

BY MS. BOLEYN: That's all the questions we have,

Your Honor. I think Mr. Watkins would like to be

heard from at this time.

BY THE COURT: A11 right, Mr. Watklns.

BY MR. GLUSTROM: Your Honor, ffidy I object? I

believe that this is an evidentiary hearing conducted

by the State. Mr. Watkins is here j-n a private

capacity representing Mr. Hasty. The issue 1s

whether there's been a Giglio violation. We're not

here to try the Bar complalnt. And I don't believe

that Mr. Watklns would have any standing to cross

examine a witness. I believe that's the Assistant

Attorney General's unless he has some special

appointment from the State. I don't believe he

has any standing to cross examine any witness at

this hearing.

BY THE COURT: Is that your purpose, to cross

examine him, Mr. Watkins?

BY MR. WATKINS: I want to find out about Mr.

Hasty's place in this. I'm trying to protect

his rights.

BY THE COURT: Counsel objected, but I don't see

BY MR. WATKINS: AII I want to do is get at the

truth.

BY THE COURT: --that Mr. Boger would have anything

that he would not want to reveal at this time.

You're speaklng for him. You're on the floor. Mr.

Boger's on the witness stand. But, I want to hear

from Mr. Boger on it. Mr. Boger, do you object to

answering questions from Mr. Watkins?

BY MR. GLUSTROM: Your Honor, mdy I interject and

speak on behalf of Mr. Boger on this matter? My

objection is not that Mr. Boger has an objection

to reveali-ng information. He is willing to answer

any questions that the State's attorney asks him.

My objection is to a private attorney who does not

have standing i-n this court asking those questions.

If the State would like to ask any questions of Mr.

Boger, w€ wil] be more than glad to cooperate. My

I5

May 10,

only obj ection is to who is asking the questions.

BY MR. WATKINS: Your Honor, that's not a valid

ob j ectlon. That ' s j ust an ob j ect j-on to having

someone come in and seek the truth of this matter.

I'm here trying to protect Mr. Hasty's interests

because he's an i-ntegral part of -- they are accuslng

him of all kinds of disciplinary violations. And it's

the basis of their case.

1983 Hearing, 1O-1L.

BY MR. WATKINS: Your Honor, I have heard nothing

that's valid after all that rigamarole that keeps

Mr. Fred Hasty's lawyer from seeking to find the

truth on his behalf whenever he gets up to testify.

f have brought this disci-plinary file here f

didn't bring it. The State Bar brought it. And

I want it to be in evidence. And I want to ask

him about it. It's things that he's called on

us for. He's tried to see my client privately

without letting me know it. He's got something to

hide. I'm telling you. And I think it's just

aLmost beyond reason to say that Fred Hasty's

attorney can't take what steps he can to protect

his client when this man gets on the wj-tness

stand. I need to questi-on him seriously about

it. I have a place just like any other attorney

involved in this case because this is the very

heart of this case. That's al-I there is to it.

BY THE COURT: Let me hear from you again.

BY MR. GLUSTROM: Okay. It is obvious that Mr.

Watkins wants to try the disciplinary case today.

This is not the procedure. He can call Mr. Boger

at such time as the State has disciplinary proceed-

ings against his client. The purpose of this hearing

as mandated by the Supreme Court is to gather evidence

on Giglio, on a Gi-g1io violation -- not on a possible

disciplinary violation by Mr. Hasty. This is not the

proper forum for it. And the proper questions must

be asked by the State Attorney General's office

who represent the State, not Mr. Hasty. There's

a proper time for Mr. Watkins to cross examine Mr.

Boger, and that is at the disciplinary hearlng.

rd. , 44-45.

]6

Id., at 46

rd., 62-63

BY MR. WATKINS: Why is he so afraid for me to

ask him some questions, Your Honor? He hasn't said

why, I'd like to know why they're scared of me.

BY MR. GLUSTROM: Your Honor, Rdy I respond? Mr.

Watki-ns' name does not appear on any pleadings in

this case. The Court has never recognized his presence

in here. And he is simply -- granted, he's sittj-ng

at the table of the prosecuti-on, but that does not

give him any type of authority to cross examine any

witnesses in this hearing. He si-mpIy legally has

no standing . Mr. Hasty's disciplinary proceed-

ings are not at j-ssue here.

BY MR. GLUSTROM:

a Your best estimate

ago?

is it was three or four months

A [WILLIS SPARKS]: Let me see if I have any note

at aII. f don't think I do.

BY MR. WATKINS: That letter that I --

BY MR. GLUSTROM: Your Honor, fidy I say something?

ft is my opinion very firmly that if Mr. Watkins

continues to interject into this hearing that

irreversible error will be committed, that Mr.

Smj-th's constitutional rights will be violated

and thls whole hearing will have to be redone.

And I just strongly urge Your Honor to please

1et the State's attorneys represent the State.

BY THE COURT: We1I, I think what he was trying

to do was attempt to identify that date. f don't

know that was interjecting anything else. But,

Iet's proceed, Mr. Watkins, if you'1I just wait

a minute and let's see if he can determine the

date.

-L7

BY MR. BOGER:

a With the letter that you received in January

of 1983, was there appended anything denominated

a personal and confidential memorandum of complaint

that would set forward the complaint made against

you?

A IFRED HASTY]: Yes, there was.

a I'Il ask the court reporter to mark Petitioner's

Exhibit 13, a two page Cocument appended to which

are a two page document entitled "Affidavit, Fred

M. Hasty, " and some transcript testimony of the

materials, the total runs to

BY MR. WATKINS: Now, Your Honor, I understood Mr.

Boger to say that this is a formal complaint; am

I correct? You sald that, Mr. Boger.

BY MR. BOGER: Your Honor, I don't know how to

respond to counsel's question.

BY THE COURT: Is this a formal complaint or not?

BY MR. BOGER: I asked Mr. Hasty a question and he

said that something he received is an answer.

BY THE COURT: Something appended to it.

BY MR. BOGER: What I said was personal and confi--

dential memorandum of complaint. Those are the words

I used.

BY THE COURT: A11 right. Let him see if he can iden-

tify it and then I'1I hear from --

BY MR. WATKINS: This is all I want understood.

No formal complaint has been filed and transmitted

to the Supreme Court and until that happens, there

is no formal complaint. This is only a memorandum.

BY THE COURT: A11 right.

BY MR. WATKfNS: To which he has responded.

BY MR. BOGER: Your Honor, I'd like a continuing

objection that any interruptions by counsel for Mr.

Hasty that go toward elaborating on testimony rather

than simply --

BY THE COURT: I can't see that that would hurt

your client, Mr. Boger. If you do, tell me about it

now -- to just clarify something that protects his

client.

_I8

BY MR. BOGER: This is a proceeding primarily

involved -- indeed soIe1y involved with Mr.

Smith's life or death issue of his trial. We

have tried to accomodate Mr. Hasty and hls

lawyer, but this is not a Bar proceeding. And

Mr. Hasty's lawyer is not entitled to interject

matters into this case which may be relevant to

Mr. Hasty's Bar proceeding, but are not relevant

to Mr. Smith's trial. That's my objection. I

think there's a due process foundation for it.

BY THE COURT: I'11 overrule you at this point

on this document.

Id., lI5-17. Not only did Mr. Watkins personally interject himself

throughout the state proceedi-h9s, but he had collaborated with

state bar offj-cials to ensure that they would be present in the

courtroom, taking notes for disciplinary proceedings on Fred

Hasty's recantatj-on (see May 10, 1983 Hearing, Pet. Ex. 15,16 e t8).

These j-ntrusj-ve diversions created a "carnival atmosphere,"

Sheppard v. Maxwell-, 384 U.S. 333, 358 (1966) far removed from

the "judicial serenity and calm to which Ipetitloner] was entitled,"

Estes v. Texas, 381 U.S. 532,536 (f965). The effect on the

witnesses, especial-ly on Fred Hasty's crucial testimony, could

hardly have been more detrj-mental to petitioner's interests. It

is unnecessary to conclude that these constant distractions inflic-

ted injuries of constitutional di-mension in order to find that

such a hearing could not meet the "fair hearing" requirement of

Townsend v. Sain, supra, 372 U.S. at 3I3.

Under all of these circumstances, it was error for the

District Court to rely so1e1y upon 52254(d) (F'ea. Order, 3*5) and

to refuse to hold a further factual hearing before determining the

meri-ts of petitioner's cfalm. See Thomas v. Zant, 697 F.2d 977,

982-88 (IIth Cir. L982); In re Wainwright, 678 F.2d 951 (lfth Cir.

-19

L982); Guice v. Fortenberry, 661 V.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1981)(en banc).

II

THE DISTRICT COURT MISUNDERSTOOD THE FACTUAL

RECORD, AND TI{US FAILED TO CONSIDER OR RESOLVE

PETITIONER'S UNCONTRADICTED CLAIM THAT THE STATE

HAD CONCEALED FROM PETITIONER'S JURY A MATERIAL

THREAT BY WHICH IT INDUCED KEY TESTIMONY AGAINST

PETITIONER

Petitioner asserted a second Giglio violation in his

argument to the state court, one that does not depend upon a

credibj-Iity choice among the witnesses. (See June 13, 1983 Hearing,

117-50). Both John Maree and his trial counsel Wi11is Sparks

agreed, and Fred Hasty did not deny, that Distrj.ct Attorney Hasty

had threatened to try Maree, as the strongest case, first, most

likely seeking a death sentence against him if he did not testify

against peti-tioner. If he would testify, however, Hasty woul-d leave

open his disposi-tion of Maree' s case. Petitj-oner has contended,

in light of the testimony of Maree and Fred Hasty's closing argument,

that his due process rights were violated by Hasty's failure to

disclose this inducement for Maree's testimony to the jury (pet.

Mem. , I3-15, 25-3L) .

Neither the Superior Court nor the Supreme Court of

Georgia ever expressly addressed this clai-m, and the Attorney

$eneral suggested both to the District Court (fea. Arg., at 59)

and to this Court in oral argument on August 23, 1983 that Maree

had not been threatened by Fred Hasty until after petitioner's

tria1. The District Court so found, concluding that "the threaten-

i-ng conversation occurred after petitioner's trial and before

the second trial . and could not possibly be relevant," (Fed.

Order, at 7). In fact, the April 7, 1985 affj-davit of John Maree,

-20

submitted by the Attorney General in state habeas proceediilgs,

contaj-ned a sworn account by Maree of his "discussions wj-th then

District Attorney Fred M. Hasty" which took place "prior to the

trial of John Eldon Smith" (May lO, 1983 Hearing, Resp. Ex. 1,

at f38). In that account, Maree averred:

"That the only statement made pertaining

to any trial was that if I did not agree

to testify, that then D.A. (Fred Hasty)

would assign my case to an assistant district

attorney for prosecution and that a death

sentence would most likely be sought."

Id. Maree confirmed the accuracy of this affidavit on cross-examina-

tion during the June 13th hearing. (June 13, 1983 Hearing, at 36).

The District Court, therefore, clearly misunderstood the

state court record and, consequently, failed to rule on the merits

of this c1aim. Petitioner has elsewhere set forth argument and case

citations establi-shing that, under the principles of Gi.91io, there

is "no di-fference between concealment of a promise of leniency and

concealment of a threat to prosecute," United States v. Sutton,

542 F.2d 1239, L2/*2 (4th Cir. 1976) (see Pet. Mem. 25-3l-). The mis-

representation imparted to petitioner's jury began when Maree, oh

cross-examinati-on, denied being promised anything by state prosecu-

tors: "The only thing that was promised to me was protection for

my family and myself," (Tria1 Tr. at 37O; November 8, Ig82 Hearing,

at 570 ) . In fact, Maree knew that if he had not testified against

petitioner, he would have been tried first; his cooperation was

induced by Fred Hasty's agreement to leave the disposltion of

Maree's case open until after petitioner,s trial. Although not

as startling as a hard-and-fast deal , "Io]ne can hardly i-magj-ne

a more compelllng fact that the jury should have had in order

-2L

to properly evaluate whether a witness of doubtful credibility

was in fact being credible in his trial testimony, " United States

v. Sanfilippo, 564 F.2d l-76, L79 (Sth Cir. L977), since it gave

Maree the greatest possible incentive to testify i-n a manner detri-

mental to petitj-oner and pleaslng to the District Attorney. Indeed,

courts have recognized that often, "the more uncertain the agreement,

the greater the incentive to make the testimony pleasing to the

promisor, " Blanton v. Blackburn, 49/* F. Supp. 895, 9Ol (tut.O. La.

I98O) aff'd, 654 F.2d 7LB (5th Cir. 198I); accord, Boone v. Paderick,

5/,L F.2d 447, 45L (4th Cir. 1976).

Maree furthered the misimpression his testimony gave to

the jury as defense counsel pressed him on cross-examinatj-on:

"Q. How about in respect to your liberties,

your freedom?

A. Nothing has ever been said of that."

Id. In truth, Maree had been told by the District Attorney that a

death sentence the ultimate deprj-vation of liberty -- "most likely"

faced him unless he testified for the State. The fact that this

testimony may not have been technj-cal1y perjurous, of course, is

not decisive. The Supreme Court has condemned "testimony Ithat],

taken as a whole, erave the jury [a] false impressioh," Alcorta

v. Texas, 355 U.S. 28,31 (1957), even if not literal1y faIse.

The jury's impression that Maree was testifying without

any inducement from the District Attorney was further heightened

by Hasty's own closing argument, in which he assured the jury:

"As District Attorney of this Clrcuit I teII you that those other

two defendants will be tried and I te11 you if I have anything to

do with i.t those two defendants wi.lI be convicted of Murder"

-22

(May IO, 1983 Hearing, Pet. Ex. 10, at 165-66). The clear

impressi-on deliberately conveyed to the jury was that Fred Hasty

intended to prosecute both Rebecca Machetti and John Maree just

as petitioner was being prosecuted -- brought before a jury for

trial on murder charges, and if convicted, to face a death

sentence. Yet Fred Hasty has since stated, and has never re-

tracted the statement, that "earlier in my mind, I had known that

if [Maree] testifj-ed that I was going to make a recommendation of

concurrent life sentences," (May 1O, 1983 Hearing, TT-78), Thus

Hasty knew to a certainty that Maree would never be "tried" for

murder, since Hasty himself ful1y intended, even as he made his

closing argument to petitioner's jury, to offer hi-m a plea to life

imprisonment.

This Court has observed that a Giglio violation j-s often

sealed when a prosecutor recalls to a jury's mind and capl-tallzes

in closing argument on the misleading testimony of a key witness.

See, e.g., United States v. Sanfilippo, 564 F.2d l-76, 179 (Stn Cir.

L977). Hasty's argument continued with mock speculation concerning

Maree's possible motives for testifying, closing with the observa-

tion, "you have to understand in his testimony that he is hoplng

to save himself from the electric chair. It is the human reaction.

It j-s natural for him to hope that, but he told You, and i can tell

you, there have been no promises." (May IO, 1983 Hearing, Pet. Ex.

IO, at 166). In truth, while no explicit promise had been made,

Hasty knew that Maree's testimony had been induced by far more than

a "natural" human hope, but by the sure and certain knowledge

imparted to hlm directly by the Distri-ct Attorney that if he

-23

would not testify, he would be tried first, and perhaps face

a death sentence.

It is these deliberately orchestrated misimpressions that

constitute the Gig11o violation in this case. The District Court

stressed during oral argument that petitioner's experienced trial

counsel, Floyd Buford and Garland Byrd, undoubtedly sensed that some

understanding motivated Maree's testimony (Rea. Arg., at 20). Yet,

this Court has plainly recognized that "It]he defendant gains

nothing by knowing that the Government's witness has a personal

interest in testifying unless he is able to impart that knowledge

to the jury," United States v. Sanfilippo, supra, 56/* F..2d at I78.

It was petitioner's jury that was entitled to ful1 knowledge of the

threats and inducements under which Maree testified. The nondisclosure

of those inducements violated petitioner's due process rights under

Giglio v. United States, and requires that he be afforded a new trial.

21

III

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED BY APPLY]NG

RES JUDICATA AND WAIVER PRINCIPLES TO

oETTRTAffiETHER PETTTToNER' s

ARBITRARINESS,/RAC IAL DI SCRIMINAT ION

CLAIMS, REASSERTED PROMPTLY UPON THE

RECEIPT OF NEWLY AVAILABLE EVIDENCE,

SHOULD BE ENTERTATNED BY THE FEDERAL

COURTS

The Dlstrict Court summarily rejected petitloner's

claim that the death penalty has been imposed in the State of

Georgia in an arbitrary and racj-ally discriminatory pattern

with the observation that "consideration of those . issues

4

is foreclosed in this Court" (Fed. Order, at 3).- tn its final

order, the District Court cited without analysis an assorted and

somewhat puzzling collection of state and federal statutes and

cases in support of its holding. The initial citation to this

Court's adjudication of petitioner's similar claims in Smi.th v.

Balkcom, 67I F.2d 858 (Stn Cir. 1982)(on rehearing), as well as

the failure ever to address questions of possible "inexcusable

4 Petitioner submitted an affidavit to the District Court out-

T:-n:-ng the evidence he sought to introduce in support of this

claim (Affidavit of John Charles Boger, dated August L7, 1983,

flll3-5 ) . He also made an extensive of f er of proof to the District

Court during oral argument on August 17th (Fed.Arg., 26,29-35).'

Final1y, he submitted a written motfon to the District court,

seeking an evidentiary hearing. As petitioner noted, the testimony

and exhibits from the two-week Mccleskey v. Zaat, hearing, which

setsforthpetitioner'Sproof:.ffitthen,andsti11

are not, transcribed for written submission to the Court. However,petitioner unsuccessfully offered live testimony to the District

Court in lieu of documentary evidence.

25

neglect" or "deliberate bypaSS, " strongly suggests that the District

Court resolved petitioner's claim on res judicata grounds, drawing

upon the contention by the Attorney General during oral argument

before the District Court on August 17,1983, that "It]he Court

has already litigated that lclaim] and it$ just precluded

at this point." (rea. Arg., at 67).

If this is so, the District Court clearly overlooked

"the familiar rule of law that a denial of an application for

habeas corpus is not res judicata with respect to subsequent applica-

tlons." Potts v. zant, 638 F.2d 727, 738 (5th Cir. unit B), cert.

denied, 451 u.S. 87"7 (1981). In Sanders v. United Statel 373 U.S.

I (1963), the Supreme Court noted that even "[a]t common 1aw, the

denial by a court or judge of an application for habeas corpus

was not res judicata, " id. at 7 . This carefully preserved excep-

tion to ordinary ci-viI rules that govern final-ity draws its justi-

fication from concerns vital in petiticner's case:

"IC]onventional notions of finality of

litigation have no place where life or

1i-berty j.s at stake and infringement of

constitutional rights is alleged. If

'government Iis] always ItoJ be

accountable to the judicj-ary for a manrs

imprisonment,' Fay v. Noia supra (szz U.S.

at /*O2) , access to the courts on habeas

must not thus be impeded. The inappi-ica-

bility of res'judicata to habeas, then,

is inherent in the very role and function

of the writ."

Id. at 8. See, e.g., Waley v. Johnston, 316 U.S. 1OI (L942)i

Salinger v. Loisel, 265 U.S. 224, 23o (1914).

In its order denyi-ng an evidentiary hearing the District

Court pointed to a related notion, that "Congress did not intend

26

section 2251 to be used as a vehicle for presenting additional

evidence to this court where a petitioner had an opportunity, "

oF, as the Court later phrased it, "a fuI1 and fair opportunity,"

to "present such evidence to the State courts," (Fed. Hrg. Order,q

at I).- As a general statement of habeas corpus principle, the

District Court's conclusion is manifestly in error:

"[T]he acts of February 5, L867 . in

extending the federal wrii to state prisoners

descrlbed the power of the federal courts to take

testimony and determine the facts de novo in

the largest terms The language of Congress,

the history of the writ, the dec j.sions of this

Court, all make clear that the power of inquiry

on federal habeas corpus is p1enary."

Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293, 311-12 (1963); accord, Wainwri-ght

v. Sykes , /*33 U.S. 72, 79-80 (L977); Gui.ce v. Fortenberry, 661 F.2d

496, 5OO (Sth Cir. 1981)(en banc); In re Wainwright, 678 F,2d 951,

953 (1f th Cir. L982). The Dlstrict Court's language mlght possibly

be seen as drawing upon another source of support, the Iimitation

placed by the Supreme Court on the relitigation of Fourth Amendment

claims in federal habeas proceedings. Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S.

465 (1976). If a habeas applicant has been afforded an "opportunity

for a fuI1

the state

* Each reference to the order

dourt, entered August 19, 1983,

an evidentlary hearing, will be

"Fed. Hrg. Order."

and fair litigation" of his Fourth Amendment claim in

courts, Stone forecloses relitigation in the federal

courts. Id . at, 191. Yet the Supreme Court has firmly resisted

of the United States District

denying petitioner's motion for

indicated by the abbreviation

- zt

all calls to expand Stone's "full and fair opportunity" rationale

to limit habeas consideration of constitutlonal violations outside

the Fourth Amendment context, see, e.9., Rose v. Mitchel1, 413 U.S.

5/*5, 559-64 (f979); Jackson v. Virgi_nia, 1/,3 U.S. 3O7, 32L (1979),

and there j-s strong evidence to suggest that the Supreme Court will

not subject Eighth Amendment violations to any such restriction.

See, e.9., Goodwin v. Balkcom, 684 F.2d 794 (fIth Cir. 1982), cert.

denled, _U.S. _, 76 L.Ed.2d 364 (1983); Spivey v. Zant, 661 F.2d

/,64 ( 5th Cir. 1981 ) , cert. denj-ed, u.s. , 73 L.Ed.2d L374 (1982).

The proper standard, petitioner submits, for assessing

whether petitioner's arbitrariness/racial discrlmination claims

should be adjudicated on their merits by the federal courts is

set forth in Rule 9(b) of the Rules Governing Section 2254 Cases.

Rule 9(b) limits the relitigation of a federal claim only if 1t

6/

would constitute an absue of the writ. "To determine whether given

conduct constitutes abuse of the writ, . reference to pre-Rule 9

case law is necessary. Rule 9(b) dj-d not in any way change the

standards that govern habeas corpus petitioners in the federal

courts. Rather, the Rule restates principles that had previously

been judicially developed." Paprskar v. Estelle, 612 F.2d 1003,

lOO5 (Stn Cir. 1980); accord, Potts v. Zant, 638 F.2d 727, 739

(Stn Cir. Unit B 1981). The foundation case in understanding the

abuse of the writ doctrine is Sanders v. United States, supra,

q The Di-strict

Efrough it made no

here. (rea. order

Court cited Rule 9(b

written attempt to

, dt 2).

) :-n dismissing this c1aim,

analyze its applicability

-28

which catalogues the various circumstances under which charges of

abuse may arise.

fn the present case, although the District Court per-

mitted petltioner to submit available documentary evidence in hj-s

initial habeas application, it denied him any opportunity for an

evidentiary hearlng on his claims. (See Order, entered January 1I,

198O)(denying petitioner's moti-on for an evidentiary hearing).

Instead, the District Court referred the case to a United States

Magistrate, who rejected petitioner's arbitrariness,/discrimination

claims as a matter of law, relying upon Spinkellink v. Walnwright,

578 F.2d 582,6O6 n.28 and 614 o.4O (Stfr Cir. 1978) for the propo-

sition that unless "petitioner shows some specific act or acts of

discrimination against him or that the facts and circumstances

of his case are so clearly underserving of capital punishment that

to i-mpose it woul-d be patently unjust and would shock the conscience,"

no relief is warranted. (Magistrate's Proposed Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law, dated September 9, I98O, at 6). The

District Court conflrmed the magistrate's recommendation in a one-

page order, entered November 26, 1980.

Thus, under Sanders v. United States, it is reasonable

to categorize petitioner's arbitrariness/discrj-mination claims as one

"earlier presented but not adjudicated on the merits," 373 U.S. at

17. If they are so viewed, "full consideration of the merits of

the new application can be avoided only if there has been an

abuse of tHe writ," id. The Court in Sanders offered various

examples of abuse, including a petitioner who "deliberately withholds

one of two grounds for federal relief," or who "deliberately

29

abandons one of his grounds at the first hearing," or whose

"only purpose is to vex, harass, or de1ay," id. at 18. Since

this Circuit has interpreted "'[t]he "abuse of the wrlt" doctrine

Ito be] of rare and extraordinary application.' Paprskar v. Estelle,

612 F.2d at 1OO7; Hardwick v. Doolittle, 558 F.2d 292, 296 (5th

Cir. L977), cert. denied, 134 U.S. LO49 (1978); Simpson v. Wainwright,

188 F.2d 494, 495 (Stn Cir. 1973)," potts v. Zant, supra, 638 F,2d

at 711, and has held that, even in the presence of abuse, "[i]f a

petitioner is able to present some 'justifiable reason' explaining

his actions, reasons which make j-t fair and just for the trial

court to overlook' the alIegedly abuslve conduct, the trial court

should address the successive petition," id. at 741, nolhlng in

peti-tioner's conduct can be deemed to constitute the kind of

"abuse" contemplated by Sanders.

Under these standards, indeed, it is clear that the State has

not even met its burden to plead any abuse of the writ by petitioner

with the "clarity and particularity," Price v. Johnston, supra,

334 U.S. at 292, required by the Supreme Court. Although the

Attorney General has made general allegations of abuse during

oral argument (fea. Arg.,66-68), and in its brief to the

Distri-ct Court (Resp. Br. at IO)("It]he specific abuse pled

is that this is a successive federal habeas corpus petition which

raises one issue previously determined adversely to the Petitioner,

i.e., that the death penalty in Georgia is imposed arbitrarily

and discriminatorily), at no time has he alleged that petitioner

deliberately withheld available evidence or otherwise engaged in

the conduct proscribed by Sanders or Price. Thus no abuse can

be found, and the Distri-ct Court erred by not proceeding to the

merits.

30

Even if petitioner's clalms were categorized under the

first branch of Sanders, as among those claims "determined adversely

to the applicant . on the merits," Sanders v. United States,

supra, 373 U.S. at 15, "i-t is open to the application to show

that the evidentiary hearing on the prior application was not

full and fai.r," id., l6-L7. The Supfeme Court, in defining a

"full and fair hearing" under Sanders, expressly referred to its

"fulI and fair" hearing standards previously enunciated in

Townsend v. Sain, supra. Since, under Townsend, a hearing cannot

be deemed "fuII and fair," (and thus an evidentiary hearing must

be held ) 1f "there is a substantial allegation of newly discovered

evidence," or if "the materi-aI facts were not adequately developed,"

Townsend v. Saj-n, supra, 373 U.S. at 313, petitioner's unrefuted

contenti-on that he obtained access to comprehensive new social

scientific evidence, directly relevant to this Court's criteria

laid down in Smith v. Balkcom, 67L F.2d 858 (Sttr Cir. 1982) (on

rehearing) only in mid-L982, long after his initial federal habeas

petition had been presented and adjudicated by the District Court

(see Fed. Arg. 25-26, 29-38; Affidavit of John Charles Boger,

dated August L7, 1983, at fl1l2-3), means that he satisfies this

7/

branch of Sanders as wel1.- See generally Price v. Johnston,

J/ At one point,the Attorney General has argued that "there is no

new evidence, rather, only a new analysis by an expert witness for

the Petitioner," (nesp. Br., at 15). The assertion is fa1se. Peti-

tioner's 1979 evidence was derived from a limited data base, the

Supplementary Homicide Reports submitted by loca1 police to the FBI.

These data contained very little information on any crime or defendant.

By contrast, the evidence Professor Baldus has assembled are derived

from the official files of the Georgia Department of Offender Rehab-

ilitation, the Georgia Department of Pardons and Paroles, and the

Georgia Supreme Court. These data include a never-before-assembled

I cont'd. i

3I

supra, 331 U.S. at 29O ("we cannot assume that petJ-tioner has

acquired no new or additional j-nformation since the time of the

trial or the first habeas corpus proceeding"); Vaughan v. Estelle,

67L F.2d L52, 153 (5th Cir. L982)("if a petitioner's unawareness

of facts which might support a habeas application is excusable,

or his failure to understand the )-egal significance of the known

facts is justifiable, the subsequent filing is not an abuse of

u

the writ" ) .-

FinalIy, if the District Court, applying the appropriate

legal standard, had entertained any genuine doubt on this record as to

whether petitloner may have abused the writ or violated RuIe 9(b),

it was obligated to hold an evidentiary hearing after fair notice

to petitioner. Abuse of the writ

"is a matter whi-ch should be determined

in the first instance by the District Court.

And it is one on which petitioner is entitled

to be heard either at a hearing or through an

amendment or elaboration of his pleadi-ng.

L/ cont' d.

wealth of information on each crime and defendant, much of it

gathered by the Department of Pardons and Paroles directly from

field interviews with police and prosecutors in each case.

!/ The Supreme Court in Sanders also noted that "the applicant

may be entitled to a new heari-ng upon showing an interveni-ng change

in the lahrr" Sanders v. United States, supra, 373 U.S. at 17.

Petitioner has contended throughout these successive proceedi-ngs

that this Court's modification of lts legal standard for the

evaluation of statistical proof of discrimination in

capital sentencing, which occurred only upon the rehearing of

his appeal, left him unable to adduce appropriate evidence until

long after he had left the District Court. (See Fed. Arg., 26-

29; Pet. Mem. 17-18).

-32

Appellate courts cannot make factual

determlnations which may be decisive

of vital rights where the crucial facts

have not been developed. "

Price v. Johnston, supra, 33/* U.S. at 29L; cf ., Thomas v. Zant,

697 F.2d 977,986 (Ilth Cir. 1983). Respondent's suggestion.

that "the hearing held before this Court on August 17, 1983

provided Petiti-oner with a full and fair opportunity to present

any evidence rebutting the allegation made by the Respondent

that this successive federaL habeas corpus petition constitutes

an abuse," (nesp. Br., at 10), is obviously wi-thout legal or

factual foundation. The hearing, as petitj.oner noted at the

outset, had been ca1Ied on short notice less than seven

hours (fed. Arg., at 6). Petitioner received no prior notice

of the subject matter of the hearing, and counsel announced at

the outset his understanding that peti-tioner's "application for a

stay [of execution was to be] the principle [sic] question

this afternoon before the Court," (Fed. Arg., :.-2). More

specifically, petitioner had received no prior notice, either

from the District Court or from the Attorney General, that

abuse of the writ would be pleaded or addressed duri-ng the hearing.

Indeed, petltioner did not receive respondent's written answer plead-

ing abuse of the writ unt11 August 23, 1983, six days after the

August lTth hearing. (See Affidavi-t of John Charles Boger, dated

Atrggst 23, 1983I. Furthermore, as the Attorney General was weII

aware, counsel for petltioner had been deeply engaged in a two-

week evidentiary heaning in the Northern District of Georgia at the

time of the August ITth oral argument, with absolutely no fair

opportunity to prepare to rebut charges of abuse of the writ, even

-33

had notice been timely given by the Attorney General (see Fed.

Arg., dt 30). These circumstances hardly qualify as the "broad"

right granted to any habeas petitioner by this Clrcuit to "rebut

or explain any alleged abuse . once the government has met its

burden by pleadj-ng abuse of the writ," Potts v. Zant' supra, 638

F.2d at 747-78 especially when the Attorney General has yet to

plead "with particularity" any facts that might amount to an

abuse.

In sum, oh the present record, petiti-oner believes

that this Court could properly conclude that no genuine Rule 9(b)

abuse has been pleaded or even seriously suggested by the Attorney

General, and that the District Court should be requi-red to adjudi-cate

the merits of petitioner ' s arbitrariness/discrimination claims either

after a fuII evidentiary hearing or upon an expansion of the record

under Rule 7 to include the record in McCleskey v. Zant, No. 8I-

2134A (N.D. ca. ), as suggested by petitioner (effiaavj.t of John

Charles Boger, dated August L7, 1983, 1l{14-6). Alternatively, this

Court could remand for an evidentiary hearing on the question of

possible abuse of the writ under RuIe 9(b), Sanders v. United

States, and other relevant cases. What the Court cannot properly

do is to affirm the District Court's order which summarily dismlssed

these substantial federal constitutional claims in reliance upon

inapplicable legal standards.

-34

IV

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED BY REJECTING

PETITIONER'S MERITOR]OUS JURY CLAIM

WITHOUT AFFORDING HIM A REASONABLE

OPPORTUNITY TO DEMONSTRATE "CAUSE'' AND

"PREJUDICE'' FOR ANY PROCEDURAL DEFAULT

As petitioner has shown elsewhere, (Pet. Mem., 2l-23,

47), the jury pool from which his trial jury was selected plainly

and substantlally underrepresented women, thereby violatj-ng his

Sixth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendment jury rights. Machetti v.

Linahan, 679 F.2d 236 (llth Cir. L982), cert. denied, U.S.

74 L.Ed.2d 978 (1983). Although respondent apparently refuses

to concede that this Court's opinion in Machetti resolves peti-

tioner's jury claim, he nevertheless is at a loss to explain

how petltj-oner's jury, drawn within a month of Rebecca Machetti's

own trial from the same jury pool in the same county and selected

according to the same unconstitutlonal "opt-out" statute, might

evidence a 36 percent underrepresentation of women and yet be

free of that statutory infirmity. The merits of this claim,

therefore, seem clearcut.

The Attorney General has also contended, however, that

petitioner's assertion of this jury claim constitutes a RuIe 9(b)

abuse of the writ, since it "could have been presented in Petitioner'

e/

first federal habeas corpus petition, " (Resp. Br. , Ert 10).- The

Attorney General discounts petitioner's contention that since the

9,/ The Attorney General alternati-vely

h-as "deliberately bypassed his right to

(Resp. Br. , at 13) .

alleges that petitioner

present this claim"

-35

Iegal doctrine under which Georgia's "opt-out" statute was held

unconstitutional was not announced until Duran v. Missouri, 439

U.S. 357 (1979) in 1979, there was no abuse in failing to assert

the claim pretrial. The Attorney General argues that abuse can

be found "even if the legal theory upon which Petj-tioner now bases

hj-s challenge to the jury composition, may have altered over the

years" (Resp. Br., at 15).

Yet the Supreme Court, as petitj-oner has shown in the

previous section, has indi-cated that no abuse of the writ should

be found if a petitioner can show "an intervening change j-n the

law or some other justification for having failed to raise a

crucial point or argument," Sanders v. United States, supra, 373

U.S. at L7. This Circuit has clearly followed the Supreme Court's

teaching, holdlng in Goins v. Allgood, 391 F.2d 692 (5th Cir.

1968), for example, that when at the time of the petitioner's

capital trial it appeared the Equal Protection CIause was satisfied

by the mere token inclusion of blacks on a grand jury, petj-tioner

Goins was entitled to raise a claim of systematic exclusion of

blacks on a successive federal habeas petition after federal jury

1aw Iater was clarified. See Marks v. Estelle, 691 F.2d 73O, 733

(Stn Cir. L982)("Mark's petition. . . asserts a right that did

not exist untiJ- L972 . to assert a constitutional right [at

triall he didn't have . would require a degree of diligence

much higher than reasonable"); Vaughan v. Este11e, 67L F.2d L52,

153 (5th Cir. 1982)("if a petltioner's unawareness of facts

which might support a habeas application 1s excusable, or if hi.s

36

O failure to understand the legal significance of the known facts

is justiflable, the subsequent filing is not an abuse of the writ");

United States v. Ivy, 644 F .2d 479 n.l ( Stfr Cir. 1981) ( " [w]hile

successive repetitious petitions . need not be entertained,

a petitioner is entitled to a new hearing on a ground previously

litigated if there has been an intervening change in the 1aw" ) ;

Fletcher v. Beto, 431 F.2d 575, 576 (stfr Cir. I97o)("Ia]t the

time appellant's previous petitions were filed it was not widely

known that a constitutionalty invalid prior convicti.on could be

attacked in a habeas proceeding" ) .

Here, rvhere a Sixth Amendment right to a representative

jury was announced in Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522 (1975) only

six days prior to petitioner's trial, and where specific consti-

tutional di-saooroval of "opt-out" statutes came only in L979,

Iong after peti'bioner had completed state habeas proceediDgs, no

genuine abuse of the writ -- no "inexcusable neglect" or "deliberate

bypassrr -- can be suggested. Since petitioner informed the District

Court that petiti-oner ' s trial counsel explicitly disclaimed

either knowledge or appreciation of the Supreme Court's holding

in Taylor v. Louisiana prior to petitioner's trial (Fed.Arg.41-

/*8), at a minimum, he was entitled to "an opp6rtunity to present

evidence rebutting the government's pleading," Potts v. Zant, supra,

638 F.2d aL 717; Price v. Johnston, supra, 334 U.S. at 29L; cf .

Thomas v. ZanL, 697 F.2d 97'7, 983 (IIth Cir. 1983), if the Distrlct

Court had any serious question about whether the writ was being

abused.

-37

The District Court appeared to dismiss petitioner's jury

c1aim, however, solely on waiver grounds, holding that the state

court's opini-on finding that this issue was "now foreclosed

Iis] in all respects valid and supported by decisions of the

Supreme Court of the United States and the Fifth and Eleventh

Circuits" (Fed. Order, at 2). Despite the Attorney General's

strenuous argument that a "finding of waiver under state law

should be credited by [the District] Court,"

(Resp. Br., at L7), state waj-ver principles are si-mpIy not

concl-usive of whether a federal waiver should be found, see, .e .9.., Fay

v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 439 (1965); Alvarez v. Estelle, 53I F.2d 1319,

L32L (Stfr Cir. 1976), and none of the federal cases cited by the

ryDistrict Court announce an absolute rule precluding a federal

court from reaching the merits of a constitutional claim deemed

waived under state law. To the contrary, those cases hold that

"[t]here are . exceptions to the wai-ver bar of Francis,"

Stewart v. Ri-cketts, supra, 15l- F. Supp. at 916, "if the petitioner

can show that the waiver was 'for cause' [and] show actual

prejudice." Accord, Francis v. Henderson, 425 U.S.536, 542 (1976);

Wainwright v. Sykes, 133 U.S. 72, 87 (1977); Engle v. lsaac, 456

u.s. Lo7, L29 (1982).

lO/ Tennon v. Ricketts, 574 F.2d 1243 (Stfr Cir. 1978); Stewart v.

H'fckffi 911, sL3-L1 (rrr.o. Ga. 1978) ; Mac6mi-

lTffil ozs F.2d, 236, 238 n.4 (r1th cir. r9B2); andffiT.

Henderson, 425 U .5. 536 , 54L-12 ( 1976 ) .

38

The supreme court has not ltself "decideId] whether

the novelty of a constitutional- claim ever establj-shes cause for

a failure to object," Engle v. Isaac' Supra, /*56 U.S. at ]3I, although

it has indicated that it "might hestltate to adopt a rule that would

require trial counsel either to exercise extraordinary vision or to

object to every aspect of the proceedings in the hope that some

aspect might mask a latent constitutional constitutional claim, " id.

This Circuit, however, has addressed this question, and has adopted

the rule that a recent change in law, not known to an attorney and

thus not asserted in timely fashion, can establish sufficient "cause"

to excuse compliance with a state procedural statute. See, €.9.,

Harris v. Spears, 600 F.2d 639 (5th Cir. 1979); Sincox v. EsteIIe,

57L F.2d 876 (5th Cir. 1978); cf. Jiminez v. Este1le, 557 F.2d 506

(stn Cir. ls77).

In this case, as noted,

si-x days before peti.tioner' s trial

principle was not announced until

Duren v. Missouri, in FebruarY of

the law began to change in 1976,

. The controlling consti-tutional

the Supreme Court's oPinion in

1979, nearly two Years after Peti--

tL/

tj-oner,s state habeas proceeding had been dismissed.-Under these

LI/ During oral argument before this Court on August 23, 1983

'ffiage Hatchett asked whether irrespective of possible "catlse"

for trial- counsel's failure to raise a jury challenge suff j-cient

"cause" existed to justify the fail-ure of present counsel to raise

the jury claim in state habeas corpus proceedings. The answer is

threefold. Petj-tioner's state habeas proceedings were brought in

October of Lg76 and concluded in March of L977, two years before

Duren v. Missouri was decided. Thus the law permitting such a

@yetc1ear1ydeveIopedLnl977.Secondly,peti-

tioner's habeas counsel, volunteers unfamlliar with Bibb County, had

no knowLedge of the facts that would establish an underrepresentation

of women. Only after local counsel in Rebecca Machetti's case, work-

ing independently almost a year later, gathered extensive statistical

evidence, did the factual predi-cate for the claim become apparent.

FinalIy, the Georgia statute governing state habeas procedures in

_39

I cont'd. ]

circumstances, the District Court should either have found "cause"

on the record before it or, if it harbored doubts about the trial

attorneys' affidavits averring a lack of knowledge of Taylor v.

Louisiana, (fed. Arg., at /*8), should have ordered a federal hearing

on "cause" and "prejudice." Instead, the District Court appeared

to rely on its own extra-record acquaintance with petitioner's trial

counsel to discount any possibility that counsel may not have realized

the possibility of asserting a Sixth Amendment challenge on petitioner's

behalf (feA. Arg., 47-48)("R1oyd Buford was the United States Attorney

and I was the Assistant U.S. Attorney . where the Fifth Circuit

threw out the jury box of this Court. If you read those cases, I

think you will discover that Mr. Buford . knew as much about

jury challenges as about anybody in the United States" ) . When

informed that Mr. Buford and Mr. Byrd had executed affidavits

averring their unfamiliari-ty with Taylor, the District Court

responded, "I can't believe that." (Fed. Arg., at 48).

11l cont'd.

L976 and L977, Gd. Code Ann. S5o-127(1), expressly prohibited the

assertion of jury challenges in state habeas proceedings. When peti-

tioner sought to file hls federal petition in 1979, there had thus

been no exhaustion of this claim as requi-red by Galtieri v. Wainwright,

582 F.2d 348 (Sth Cir. L978)(en banc),and the claim could not be pi-eaded.

It is possible, despite these three considerations, that petitioner's

habeas counsel were ineffective for failure to assert the jury cIaim.