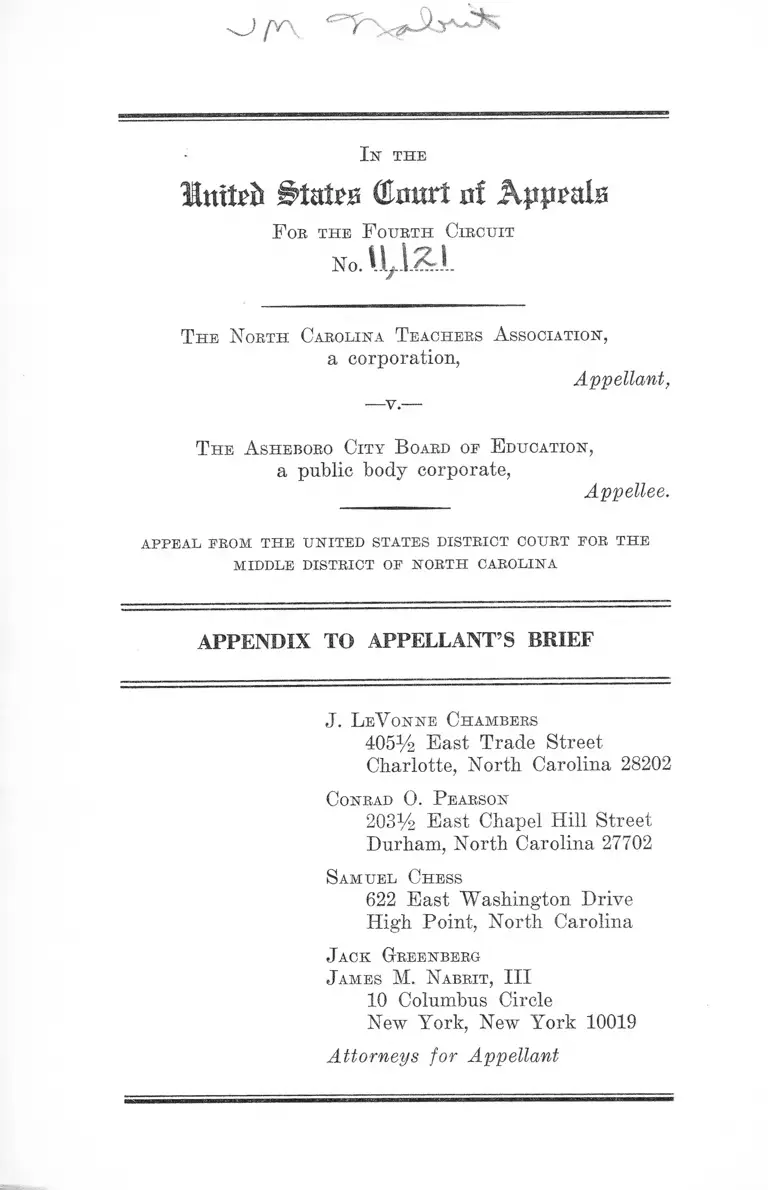

North Carolina Teachers Association v. Asheboro City Board of Education Appendix to Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. North Carolina Teachers Association v. Asheboro City Board of Education Appendix to Appellant's Brief, 1966. 109d4ac6-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10a5b276-8ade-44dd-a445-6dbee883c64c/north-carolina-teachers-association-v-asheboro-city-board-of-education-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Imtrfr Court of Appmh

F oe the F ourth Ciecijit

No. % \ Z ?\ .

T he North Carolina Teachers A ssociation,

a corporation,

Appellant,

-v.-

T he A sheboro City B oard of E ducation,

a public body corporate,

Appellee.

A P PE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FOE T H E

M IDDLE D ISTR IC T OF N O R T H C A R O LIN A

APPENDIX TO APPELLANT’S BRIEF

J. L eV onne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Conrad O. P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina 27702

Samuel Chess

622 East Washington Drive

High Point, North Carolina

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

PAGE

Motion for Preliminary Injunction.....-....................... 7a

Consent Order Extending Time to Answer.............. 8a

Answer and Motions of Defendant .............................. 9a

Response of Plaintiff.................................................... 17a

Memorandum of October 19, 1965 ............................. 21a

Consent Order of November 23, 1965 ...................... 22a

Motion for Leave to Amend Complaint -.................... 24a

Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference ........... -........ - 27a

Interrogatories dated July 10, 1965 ......-.........-........ 34a

Answer to Interrogatories ............................................ 37a

Interrogatories dated January 10, 1966 ......... —......... 77a

Answer to Interrogatories —............... .... — ..........- 78a

Interrogatories dated February 23, 1966 .................. 83a

Answer to Interrogatories ........ ...............................- 87a

Discovery Deposition of Guy B. Teachey.................. 96a

Memorandum of May 9, 1966 ..................................... 223a

Complaint ..................................... ......................... -........ l a

PAGE

Transcript of Hearing May 3, 1966 ................... —- 224a

Plaintiff’s Witness

Guy B. Teachey—

Direct ........ 230a

Cross ................ 315a

Redirect ............... 355a

Transcript of Hearing May 4, 1966 ............ -................ 374a

Plaintiff’s Witness

E. Edmund Reutter, Jr.—

Direct ....... 375a

Cross ................................ 403a

Motion to Intervene .................................................. 421a

Response to Motion to Intervene ............................. 425a

Stipulations ............ ...... .................. .......................... . 430a

Order Allowing Intervention .................................. 432a

Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Opinion 433a

Judgment ..... 456a

Notice of Appeal........................ 456a

Designation of Record on Appeal ......... ...... ............. 457a

ii

IN THE

United States itetrirt (tart

EOE T H E

Middle D istbict of North Carolina

Greensboro D ivision

Civil Action No. ------

T he North Carolina Teachers A ssociation, a corporation,

Plaintiff,

v.

T he A sheboeo City B oard of E ducation,

a public body corporate,

Defendant.

Complaint

I

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28, U. S. C. §1343(3) and §1343(4), this being a suit

in equity authorized by law, Title 42 IT. S. C. §1983, to be

commenced by any citizen of the United States or other

person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the dep

rivation under color of statute, ordinance, regulation,

custom or usage of a State of rights, privileges and im

munities secured by the Constitution and the laws of the

United States. The rights, privileges and immunities

sought herein to be redressed are those secured by the

Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the Consti

tution of the United States.

2a

II

This is a proceeding for a preliminary and permanent

injunction, enjoining the Asheboro City Board of Educa

tion, its members and its Superintendent from continuing

the policy, practice, custom and usage of discriminating

against the plaintiff, its members and other Negro citizens

of the City of Asheboro, North Carolina, because of race

or color.

III

The plaintiff in this case is the North Carolina Teachers

Association, a professional teachers association, organized

as a private, nonprofit, membership corporation pursuant

to the laws of the State of North Carolina. Plaintiff has

a membership of approximately 12,500, most of whom are

Negro teachers, teaching in the public schools of North

Carolina, including the City of Asheboro Public School

System. One of its objectives is to support the decisions

of the United States Supreme Court on segregation in

public education and to work for the assignment of students

to classes and teachers and other professional personnel

to professional duties within the public school systems

without regard to race, and to work against discrimination

in the selection of such professional personnel. Plaintiff

is the medium by which its members express their views

on issues affecting public education and their employment.

By virtue of this group association individual members

are enabled to express their views and to take action with

respect to controversial issues relating to racial discrim

ination. Plaintiff asserts here the right of its members

teaching in the City of Asheboro School System not to

be hired, assigned or dismissed on the basis of their race

or color.

Complaint

3a

IV

The defendant in this case is the City of Asheboro

Board of Education, a public body corporate, organized

and existing under the laws of the State of North Caro

lina. The defendant Board maintains and generally super

vises the public schools of the City of Asheboro, North

Carolina, making assignment of students, hiring, assigning

and dismissing teachers and professional school personnel

pursuant to the direction and authority contained in the

State’s constitution and statutory provisions. As such, the

Board is an arm of the State of North Carolina, enforcing

and exercising State laws and policies.

V

Defendant, acting under color of authority vested in it

by the laws of the State of North Carolina, has pursued

and is presently pursuing a policy, practice, custom and

usage of operating the public school system of the City

of Asheboro, North Carolina, on a racially discriminatory

basis, to w it:

A. Defendant has in the past initially assigned all Negro

students to Negro schools, and all white students to white

schools.

B. Defendant has made and is presently making as

signments of principals, teachers and other professional

personnel on the basis of race and color. Negro principals,

teachers and other professional personnel are assigned

to schools reserved for Negro students.

C. Effective with the beginning of the 1965-66 school

year, defendant proposes to discontinue grades seven (7)

through twelve (12) of the all-Negro school, Central High

Complaint

4a

School, transferring the Negro students, who reside within

the City School District to the school formerly reserved

for white students, and pursuant to its policy and practice

of making racial assignments of teachers, defendant has

dismissed all of its Negro teachers and professional per

sonnel in the grades affected solely on the basis of their

race. In addition, because of the prospective transfer of

other Negro students to formerly all-white schools, defen

dant has dismissed several of its Negro teachers in the

elementary grades solely on the basis of their race. De

fendant refuses to eliminate its racial policies regarding

teachers and professional personnel and continues to hire,

assign and dismiss such personnel solely on the basis of

their race and color.

VI

Plaintiff and its members have made reasonable efforts

to communicate their dissatisfaction with defendant’s ra

cially discriminatory practices, but without effecting any

change. Plaintiff and its members are irreparably injured

by the acts of defendant complained of herein. The con

tinued racially discriminatory practices of defendant in

hiring, assigning and dismissing teachers and professional

personnel violate the rights of plaintiff and its members

secured to them by the Due Process and Equal Protection

Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, and Title 42 U. S. C. §§1981, 1982

and 1983.

The injury which plaintiff and its members suffer as a

result of the actions of the defendant is and will continue

to be irreparable until enjoined by this Court. Any other

relief to which plaintiff and its members could be remitted

would be attended by such uncertainties and delays as to

Complaint

5a

deny substantial relief, would involve a multiplicity of

suits, cause further irreparable injury and occasion dam

age, vexation and inconvenience to the plaintiff and its

members.

W herefore, plaintiff respectfully prays that this Court

advance this cause on the docket and order a speedy hear

ing of the action according to law and, after such hearing,

enter a preliminary and permanent decree, enjoining the

defendant, its agents, employees and successors and all

persons in active concert and participation with them

from hiring, assigning and dismissing teachers and profes

sional on the basis of race and color, from dismissing,

releasing, refusing to hire or assign the Negro teachers

and professional school personnel at Central High School

on the basis of race or color, and from continuing any other

practice, policy, custom or usage on the basis of race or

color.

Plaintiff further prays that this Court retain juris

diction of this cause pending full and complete compliance

by the defendant with the order of the Court, that the

Court will allow it its costs herein, reasonable counsel fees

and grant such other, further and additional or alternative

relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable and just.

Respectfully submitted,

Complaint

Conrad 0 . P earson

203% East Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

F loyd B. M cK issick

213% West Main Street

Durham, North Carolina

6a

Complaint

J. L evon ne Chambers

405% East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

Jack Greenberg

Derrick A. B ell, J r.

James Nabrit, I I I

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiff

7a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction

Plaintiff, upon its complaint filed in this case, moves the

Court for a preliminary injunction pending final hearing

and determination of this case, enjoining the defendant,

its agents, servants, employees, successors, and all persons

in active concert and participation with them from dis

missing, refusing to hire or assign Negro teachers, now

teaching at Central High School, on the basis of race or

color and from hiring, assigning and dismissing teachers

and professional personnel on the basis of race.

Plaintiff further prays that the Court will retain juris

diction of this cause pending full and complete compliance

by the defendant with the order of the Court, that the

Court will allow it its costs herein, reasonable attorney

fees, and grant such other, further, additional or alternative

relief as may appear to the Court to be equitable and just.

8a

Consent Order

T his cause coming on to be heard and being heard be

fore the undersigned Clerk of the United States District

Court, and it appearing to the Court that counsel for the

plaintiff has consented to an extension of time to answer

for the defendant for twenty (20) days.

Now, thebeeobe, it is hereby obdebed that the defendant

be and it is hereby granted an extension of time of twenty

(20) days in which to answer or otherwise plead in this

cause.

9a

T he Defendant, A nswebing the Complaint of the

P laintiff, and R equesting T hat T his A nswer B e Used

as an A ffidavit in Support of the Motions H erein A l

leged and as Notice of Said Motions, for I ts Motions

and A nswer A lleges :

First Defense

This action should be dismissed for that:

(a) The Complaint fails to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted.

(b) Under the allegations of the Complaint Plaintiff

would be entitled to no relief under any state or set of

facts which could be proved in support of its claim or

allegations.

(c) Under the allegations of the Complaint Plaintiff has

no possible right to relief on any theory, under any dis

cernible circumstances and there is an utter lack of law

and alleged facts.

(d) For that the circumstances upon which Plaintiff at

tempts to base its cause of action are governed by State

law under the Federal Rules of Decision Statute (28

USCA 1652) and, therefore, Defendant did not owe Plain

tiff any statutory or other legal duty.

(e) The Complaint discloses that Defendant acted within

the scope of its legal, lawful rights and pursuant to valid

State Statutes and acts of the Defendant could not amount

to a violation of any rights of the Plaintiff.

(f) Plaintiff has no legal, statutory or constitutional

right to public employment and cannot be deprived of any

rights related thereto.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

10a

(g) The Defendant lias never had any legal or contrac

tual relationships with the Plaintiff and therefore the Plain

tiff is not a proper party to maintain this action and there

fore for a defect of Party Plaintiff this action should be

dismissed.

Second Defense

That for the reasons set forth in the First Defense, the

Defendant specifically moves that this alleged cause of ac

tion be dismissed.

Third Defense

The Defendant adopts and realleges the matters and

things set forth in the First Defense and further alleges

that the contracts of the teachers for the benefit of whom

this action is instituted had expired and terminated in ac

cordance with valid statutory law of the State of North

Carolina and therefore the Defendant moves the Court for

judgment upon the pleadings in favor of the Defendant

and to the end that Plaintiff’s alleged claim and cause of

action be dismissed.

Fourth Defense

The Defendant, by its Attorneys of Record hereby move

the Court to enter summary judgment for the Defendant,

in accordance with the provisions of Rule 56(b) and (e) of

the Rules of Civil Procedure, on the ground that the plead

ings, answer of the Defendant used as an affidavit, and

other exhibits, show that the Defendant is entitled to judg

ment as a matter of law. That Defendant will bring this

motion on for hearing before the District Judge of the

United States Court for the Middle District of North Caro

lina at the Federal Courtroom in Greensboro, North

Answer and Motions of Defendant

11a

Carolina, or at such other place as this proceeding or action

is set for hearing, or at such time as the Court may direct.

The Defendant alleges in support of said motion for sum

mary judgment the following:

(a) The Defendant adopts and realleges the matters set

forth in the previous defense of this Answer.

(b) That there are no genuine issues of material facts

existing which are determinative of any duty or right which

the Defendant owes the Plaintiff, and as a matter of law

Defendant is entitled to a summary judgment.

(c) That there are no genuine, relevant and material

facts as to deprivation of any constitutional rights of the

teachers in whose behalf the Plaintiff attempts to maintain

this action for that the circumstances upon which Plaintiff

attempts to base its alleged claim or cause of action are

governed by State law and, the Defendant having acted

within the scope of its legal rights according to State law

and State Statutes, no cause of action inures to the Plain

tiff in behalf of said teachers.

(d) That the teachers involved in this action were for

merly employed by the Defendant to teach in the public

schools administered by the Defendant under written, legal

contracts which were entered into on a yearly basis as re

lated to the school year and each of such contracts expired

or terminated under the statutes and law’s of the State of

North Carolina, there was no legal duty on the part of the

Defendant Board of Education and its officers and agents

to employ said teachers for another or prospective school

year, and said teachers never had any right of employment

or re-employment in the public schools of the Defendant;

that under the Rules of Decision Statute enacted by the

Answer and Motions of Defendant

12a

Congress it is the duty of the Court to enforce the State

law which governs the rights and duties of the parties.

(e) That the Defendant, the Asheboro City Board of

Education, is an agent of the State and an instrumentality

of government, as well as a body politic, and is, therefore,

not subject to the provisions of T itle VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, and therefore the Defendant is immune

from any action or proceeding such as this claim of the

Plaintiff in behalf of said teachers; and the Defendant in

these circumstances owes the Plaintiff and said teachers no

duty and is therefore not liable to the Plaintiff or to said

school teachers who are the real parties in interest in this

action.

Fifth Defense

The Plaintiff having prayed for equitable relief has failed

to show a failure on the part of the Defendant to perform

a clear, legal duty so as to provide grounds for equitable

relief and a valid basis for a proper decree in equity; that

the teachers in whose behalf the Plaintiff attempts to main

tain this action have no valid and enforceable right to pub

lic employment, their contracts having been for a definite

period of time and having expired, and said teachers are

not entitled to any exceptional or superior prerogative and

privileges because they happen to be members of the Negro

race; that the rights and privileges as to employment or

re-employment of said public school teachers are governed

by the laws of the State of North Carolina and these laws

have been observed and complied with by the Defendant;

that the pupils in the schools of said teachers were assigned

to other public schools in order to comply with T itle VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and there is therefore no

equitable basis for the extraordinary relief of injunction or

Answer and Motions of Defendant

13a

otherwise; that the laws of the State of North Carolina

govern and. control in this case under the Rules of Decision

Statute and Plaintiff is not entitled to any form of equitable

relief.

Sixth Defense

That the Defendant has a constitutional right to enter

into contracts of employment with public school teachers,

including the teachers herein affected and has a constitu

tional right in its judgment and discretion to refuse to re

employ these teachers or any other teachers in its public

school system; that any attempt on the part of the Plain

tiff to force or compel the Defendant to again enter into a

new contract or to re-employ the teachers herein concerned

is a violation of the constitutional rights of the Defendant,

is a violation of due process clause of the Fifth Amend

ment to the Federal Constitution; and is therefore in viola

tion of the equal protection and due process clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and further is in violation of the

Law of the Land clause as set forth in Article I, Section 17,

of the Constitution of North Carolina and further is an im

pairment of the Defendant’s right to contract; that such

constitutional infringement of the Defendant’s constitu

tional rights and such deprivation of the Defendant’s privi

leges and immunities are here alleged as a bar to the

Plaintiff’s right to recover in this action.

Seventh Defense

T he Defendant Specifically A nswering the V arious

P aragraphs of the Complaint F or I ts A nswer Alleges :

(1) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 1 of the

Complaint, it is admitted that the Federal Statutes desig

Answer and Motions of Defendant

14a

nated in said paragraph are set forth in the United States

Code, but it is denied that they have any application to the

Defendant or that any constitutional rights of the Plaintiff

or the teachers which are the subject of this action have

been violated or abridged or that any unconstitutional dis

crimination has been enforced or administered by the De

fendant; the allegations of Paragraph 1 are therefore un

true and are denied.

(2) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 2, it is de

nied that Plaintiff is entitled to any preliminary or per

manent injunction or that the Defendant has discriminated

against the Plaintiff or its members; the allegations of

Paragraph 2 are untrue and are denied.

(3) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 3, it is ad

mitted that the Plaintiff is a non-profit corporation having

a professional membership of teachers and organized under

the laws of this State; it is denied that the teachers involved

in this action were dismissed on the basis of race or color or,

in fact, that said teachers were dismissed at all; that, except

as herein admitted, the allegations of Paragraph 3 are un

true and are denied.

(4) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 4, it is ad

mitted that the Asheboro Board of Education is a public

body corporate organized and existing under the laws of

the State of North Carolina; it is admitted that the Defend

ant Board supervises and administers the public schools

of the City of Asheboro according to the laws and Constitu

tion of the State of North Carolina; that, except as herein

admitted, the allegations of Paragraph 4 are untrue and

are denied.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

15a

(5) Answering the allegations of Paragraph 5, the De

fendant alleges that the action taken by it was done and

performed in an effort to comply with T itle IV of the Civil

Bights Act of 1964; it is denied that the Negro teachers in

the grades affected were dismissed because of race or were

in fact dismissed at all; the Defendant had not re-employed

said teachers because their contracts had expired and the

Defendant had no need for same; that failure to re-employ

public school teachers because of transfers of students and

consolidation of schools has happened all through the State

for many years and has affected both white and Negro

teachers; that, except as herein admitted, the allegations of

Paragraph 5 are untrue and are therefore denied.

(6) The allegations of Paragraph 6 are untrue and are

therefore denied.

W.HEREFORE, HAVING F uLLY ANSWERED PLAINTIFF^ COM

PLAINT, the Defendant P rays T hat the Court H old, R ule,

A djudge and Decree as F ollows :

(a) That this action be dismissed as to this Defendant.

(b) That the Court grant the motions of the Defendant

to dismiss this action, for judgment on the pleadings and

the motion that the Court enter a summary judgment in

favor of the Defendant.

(c) That the Court hold that the Complaint does not

state a claim upon which relief can be granted and that the

Court has no jurisdiction over the Defendant and the sub

ject matter of this action.

(d) That Plaintiff has no legal capacity or status to main

tain this action.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

16a

(e) That there is not sufficient equitable basis for the

granting of a permanent injunction of a mandatory nature

or of any other nature.

(f) That this verified answer be treated as an affidavit

for the purpose of the motions alleged herein and in pass

ing upon the injunctive relief demanded by the Plaintiff.

(g) That no costs or fees be awarded or charged against

the Defendant and that the Defendant recover its costs to

be taxed by the Clerk of this Court, and that the Defendant

have such other and further relief as to the Court may seem

proper and just.

Answer and Motions of Defendant

F erree, A nderson", Bell & Ogburn

By / s / H ugh R. A nderson

Attorneys for Defendant

Asheboro, North Carolina

17a

Comes now the plaintiff, by its undersigned attorneys,

and, in response to the several motions of defendant, shows

the Court as follows:

I

This action was initally filed by corporate plaintiff on

June 8, 1965, seeking a preliminary and permanent injunc

tion against the racially discriminatory practices of defen

dant in dismissing and refusing to hire members of cor

porate plaintiff in the public schools under defendant’s

jurisdiction. Along with its complaint and motion for pre

liminary injunction, plaintiff filed a brief in support of its

motion. Defendant has filed an answer, moving

(1) to dismiss the action

(a) for failure to state a claim for relief; and con

tending

(b) and (c) that plaintiff would be entitled to no

relief;

(d) that defendant owes plaintiff no legal duty under

28 IT. S. C. §1652;

(e) that defendant acted within its legal rights;

(f) that plaintiff has no legal, statutory or contrac

tual right to public employment;

(g) that defendant has had no legal or contractual

relation with plaintiff and that plaintiff is not

a proper party to maintain the action;

(2) to dismiss the action because the contracts for teach

ers were only for one year which expired;

Response

18a

(3) for summary judgment on the pleadings, affidavits

and exhibits, realleging the matters set forth in (1)

and (2) above and alleging that defendant, being

an agent of the State, was not subject to the provi

sions of Title YII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964;

(4) To dismiss the action because defendant has a consti

tutional right to enter into contracts for employment

with public school teachers and that the action here

would violate defendant’s right of due process under

the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States as an impairment of defendant’s right

to enter into contracts.

II

To all said motions of defendant, plaintiff says and al

leges :

(1) That the First Defense of defendant is denied;

(2) That the Second Defense of defendant, realleging the

allegations of the First Defense, is denied;

(3) That the Third Defense of defendant is denied;

(4) That the Fourth Defense of defendant is denied;

(5) That the Fifth Defense of defendant is denied;

(6) That the Sixth Defense of defendant is denied.

F urther A nswering and R esponding to the M otions of

Defendant, P laintiff Says and A lleges:

I

That by this action, plaintiff seeks an injunction against

defendant’s use of race and color in employing and assign-

Response

19a

mg teachers and school personnel in the Asheboro City

School System, Such practices by defendant are clearly

violative of the rights of Negro teachers and school person

nel, members of corporate plaintiff. See Alston v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940);

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, ------

F. Supp. ------ (Civil No. 64-C-73-R, W. D. Va., June 3,

1965).

XI

That while the contracts of employment between defen

dant and Negro teachers and school personnel ran for one

year, defendant followed a practice of automatically renew

ing such contracts upon indications by employees of a desire

to remain in the system; that members of plaintiff corpora

tion indicated a desire to remain in the system but defen

dant refused to renew their contracts on the basis of race

and color in violation of their rights under the due process

and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States. See Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, supra.

I l l

Plaintiff has alleged, and defendant denied, that defen

dant has refused to rehire members of corporate plaintiff

on the basis of race and color and has employed and as

signed other teachers and school personnel on the basis

of race. There are thus genuine, relevant and material facts

in dispute and no basis for summary judgment. Rule 56,

FRCP; Barron & Holtzoff, Federal Practice & Procedure

§§1232.2, 1234 (1958).

Response

20a

IY

Plaintiff is a proper party to seek the relief prayed for

in its complaint and motion for preliminary injunction.

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, supra;

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, supra; Pierce v.

Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510; NAACP v. Alabama, 357

U. S. 449; Swann v. Charlotte-MecHenburg Board of Edu

cation%, ------ F. Supp. ------ (Civil No. 1974, W. D. N. C.,

July 14, 1965).

W herefoee, plaintiff prays that the motions of defendant

be denied and that plaintiff be granted relief as prayed in

its complaint and motion for preliminary injunction.

Response

21a

Memorandum of October 19, 1965

This matter was scheduled for Initial Pre-Trial Con

ference in the United States Courtroom, Post Office Build

ing, Greensboro, North Carolina, on Wednesday, Octo

ber 13, 1965. There was no attorney present for either of

the parties to the action.

The Court was advised that Mr. Hugh Anderson, counsel

for the defendant, was ill and confined in the hospital;

that counsel for the plaintiff had consented, subject to

Court approval, that the case he continued and not heard

on this date.

By reason of the illness of Mr. Anderson, the Pre-Trial

Conference scheduled for this date is continued until a

later date to be set by the Clerk and notice given to the

parties.

I, Graham Erlacher, Official Reporter of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of North

Carolina, do hereby certify that the foregoing is a true

transcript from my notes of the entries made in the above-

entitled Case No. C-102-G-65 before and by Judge Eugene

A. Gordon, on October 13, 1965, in Greensboro, North Caro

lina, and I do hereby further certify that a copy of this

transcript was mailed to each of the below-named attorneys

on October 19, 1965.

22a

Consent Order of November 23, 1965

I k the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOB THE

Middle Distbict of North Carolina

Greensboro Division

Civil Action C-102-G-65

North Carolina Teachers A ssociation,

a corporation,

Plaintiff,

vs

T he A sheboro City B oard of E ducation,

a public body corporate,

Defendant.

Consent Order

T his Cause coming on to be heard and being heard before

the undersigned Judge of the United States District Court,

and it appearing to the Court that counsel for the plaintiff

has consented to an extension of time for the hearing of

the initial pre-trial conference, for the defendants, for a

time to be set by the Clerk of the United States District

Court for the Middle District of North Carolina.

Now, T herefore, it is hereby Ordered that the defen

dants be and they are hereby granted an extension of time

for the hearing of the initial pre-trial conference, said time

23a

Consent Order of November 23, 1965

to be set by the office of the Clerk of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina.

E ugene A . Gordon

Judge of the United States District Court

Consented and A gree to :

J. Levonne Chambers

J. Levonne Chambers, Of Counsel for Plaintiff

F erree, A nderson, B ell & Ogburn

By J ohn N. Ogburn, J r.

John N. Ogburn, Jr., Attorneys for Defendant

24a

Motion for Leave to Amend Complaint

Come now the plaintiff by its undersigned attorneys and

respectfully move the Court for leave to amend its com

plaint, heretofore filed in the above subject cause, by adding

the following paragraph to the prayer for relief immedi

ately following the first paragraph thereof;

That all teachers found by the Court to be denied employ

ment in violation of their rights under the Due Process and

Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment

be reinstated as teachers in the School System in the same

or comparable position.

25a

Counsel for each of the parties in the above-entitled ac

tion, pursuant to notice, appeared on the llt,h day of

February, 1966, for an initial pre-trial conference. Julius

L. Chambers, Esquire, appeared as counsel for the plain

tiff, and Hugh R. Anderson, Esquire, and Hal H. Walker,

Esquire, appeared as counsel for the defendant.

After conferring with counsel for the parties, the fol

lowing order is entered on initial pre-trial conference:

(1) It is Ordered that each of the parties commence

forthwith the processes of appropriate discovery, and that

same be completed on or before the 12th day of March,

1966. In this connection, it was observed that discovery had

already been initiated by the parties.

(2) It is further Ordered that if a party does not com

plete the processes of discovery on or before the aforesaid

date, such party shall be precluded from thereafter attempt

ing discovery, unless by leave of court first granted upon

a showing of good cause as to why the processes of discov

ery were not completed within the time above specified.

(3) It is suggested that counsel for each of the parties

meet and confer within ten days from the date of this

order in a good faith effort to (1) stipulate as many factual

issues as possible, (2) discuss and agree upon discovery

schedules, and (3) consider other matters that might tend

to conserve time, reduce expenses, and expedite the eventual

trial of the factual and legal issues in dispute.

(4) The parties advise that it is not contemplated that

any third-party complaint or impleading petition will be

filed.

Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference

26a

(5) It is stipulated that the party defendant has been

properly served with process.

(6) It is stipulated and agreed that the Court has juris

diction of the parties and of the subject matter.

(7) It is stipulated and agreed that the parties to the

action have been correctly designated.

(8) It is stipulated and agreed that there is no question

concerning misjoinder or non-joinder of parties.

(9) It is stipulated that there is no necessity for the

appointment of a fiduciary to represent any party to the

action.

(10) The Court has ruled on all pending motions.

(11) A trial by jury has not been demanded within the

time provided by the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and

it is Ordered that the case be placed on the non-jury docket.

(12) To the extent presently known, the parties esti

mated that the trial would consume approximately one day.

(13) The parties were advised that it was anticipated

that the Final Pre-Trial Conference would be held in ap

proximately the month of April, 1966, and that the case

would be calendared for trial on or about May, 1966.

E ugene A. Gordon

United States District Judge

Order on Initial Pre-Trial Conference

27a

Pursuant to the provisions of Rule 16 of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rule 22, a final pre-trial

conference was held in the above-entitled cause on the 1st

day of April, 1966.

J. LeVonne Chambers appeared as counsel for plaintiff.

Hal H. Walker and Hugh R. Anderson of the law firm of

Walker, Anderson, Bell & Ogburn appeared as counsel for

defendant.

1. It is stipulated that all parties are properly before

the Court, and that the Court has jurisdiction over the

parties and the subject matter.

2. It is stipulated that all parties have been correctly

designated, and there is no question as to misjoinder or non

joinder of the parties.

3. Plaintiff’s contentions are:

That prior to and since the Brown decision the de

fendant Board has followed a policy of hiring and as

signing teachers and school personnel on a racial basis;

that Negro teachers and professional school personnel

through the 1964-65 school year were employed and

assigned to the all-Negro Central High School, and

white teachers and professional school personnel to

the all-white schools; that in attempting to comply with

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the defendant

Board adopted a plan providing for the closing of the

high school grades (grades 9-12) at the all-Negro Cen

tral High School and the return of county Negro stu

dents to county schools; that the defendant accordingly

discontinued the former teaching positions in the high

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

28a

school grades and reduced the teacher allotment in

other grades of the all-Negro school, that pursuant to

defendant’s policy and practice of hiring and assign

ing teachers on a racial basis, defendant dismissed and

refused to rehire nine Negro teachers in the all-Negro

Central High School without according these teachers

due process and equal protection of the laws as secured

to them by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

4. Defendant’s contentions are :

A. That there are no genuine, relevant or material

facts as to the deprivation of any constitutional rights

of the teachers in whose behalf the plaintiff attempts

to maintain this action for that the circumstances upon

which plaintiff attempts to base its alleged claim are

governed by the laws of the State of North Carolina,

and the defendant has acted within the scope of its

legal rights according to the laws of the State of North

Carolina in such cases made and provided.

B. That the teachers involved in this action were

formerly employed by the defendant School Board to

teach in the public schools administered by the defend

ant under valid written contracts which were entered

into on a yearly basis as related to the school year in

volved, 1964-65, and that each of said contracts expired

or terminated under the statutes and laws of the State

of North Carolina, and that there was no legal duty on

the part of the defendant, Board of Education, and its

officers or agents to employ said teachers for another

school year, and further that said teachers did not have

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

29a

any legal right of employment or re-employment in the

public schools of the defendant.

C. That plaintiff does not state a claim in law or

fact upon which the relief sought can be granted, and

further that plaintiff has failed to show wherein equita

ble relief should be granted to plaintiff and plaintiff

has failed to show a default or failure on the part of the

defendant to perform a legal duty such as would pro

vide grounds for equitable relief and a proper decree

in equity.

D. That the defendant, being a public body corporate

organized and existing under the laws of the State

of North Carolina, has, during the time set forth in

the complaint, complied with the requirements of the

law in supervising and administering the public schools

of the City of Asheboro according to the laws and Con

stitution of the State of North Carolina, and that any

contractual relation that had existed between any

teachers and this defendant had terminated and ex

pired and any such teachers were not entitled to em

ployment by the defendant School Board.

5. Plaintiff’s exhibits to be offered at trial:

A. Answers to interrogatories, dated July 23, 1965.

B. Deposition and attached exhibits of Guy B.

Teachey.

C. Deposition of T. Henry Bedding.

D. Answers to interrogatories, dated January 20,

1966.

E. Answers to interrogatories, dated March 5, 1966.

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

30a

6. It is stipulated and agreed that defendant’s counsel

have been furnished a copy of each exhibit identified by

plaintiff.

7. It is stipulated and agreed that each of the exhibits

may be received in evidence without further identification

or proof.

8. Defendant’s exhibits to be offered at trial:

A. Depositions and answers to interrogatories in this

proceeding.

9. It is stipulated and agreed that plaintiff’s counsel has

been furnished a copy of each exhibit identified by the

defendant.

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

10. It is stipulated and agreed that each of the exhibits

identified by the defendant is genuine and, if relevant and

material, may be received in evidence without further iden

tification or proof.

11. List of names and addresses of all known witnesses

that plaintiff may offer at trial, together with a brief state

ment of what counsel propose

of each witness:

Names and addresses

A. E. Edmund Reutter, Jr.

Professor of Education

Columbia University

New York, New York

to establish by the testimony

Statement of facts to be

established

General policies regarding

hiring and assigning school

personnel including person

nel in the Asheboro City

School System. The dis-

31a

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

Names and addresses

B. Guy B. Teachey

Superintendent

Asheboro City Schools

Asheboro, North Carolina

C. T. Henry Redding

Chairman

Asheboro City Board of

Education

Asheboro, North Carolina

D. Pearline L. Palmer

Charlotte, North Carolin

Statement of facts to be

established

criminatory affect of appli

cation of criteria and pro

cedure employed by the

Asheboro City School Board.

Procedure followed in hir

ing and assigning of teach

ers and school personnel in

the Asheboro City School

System, including Negro

teachers not rehired for the

1965-66 school year.

Policies and procedures fol

lowed by the Asheboro City

School Board in hiring, as

signing and dismissing

teachers and school person

nel.

Qualifications as teacher in

public schools.

12. List of names and addresses of all known witnesses

that defendant may offer at trial, together with a brief

statement of what counsel propose to establish by the

testimony of each witness:

Statement of facts to be

Names and addresses established

A. Guy B. Teachey Practices and policies con-

Superintendent eerning the defendant School

32a

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

Names and addresses

Asheboro City Schools

Asheboro, North Carolina

B. Jefferson R. Snipes

Morganton City Schools

Morganton,

North Carolina

Statement of facts to fee

established

Board relating to employ

ment of teachers and school

personnel.

(To be offered as adverse

witness)

Qualifications of individual

teachers and personnel at

Central High School during

the 1964-65 school year.

13. There are no pending or impending motions, and

neither party desires further amendments to the pleadings.

14. Additional consideration has been given to a separa

tion of triable issues, and counsel for all parties are of

the opinion that a separation of the issues in this par

ticular would not be feasible.

15. Plaintiff contends that the contested issues to be

tried by the Court are as follows:

A. Whether the School Board’s practice in hiring, assign

ing and dismissing teachers and school personnel vio

lates the rights of plaintiff and members of plaintiff

association guaranteed to them by the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

B. Whether the School Board in dismissing and refus

ing to rehire Negro teachers formerly teaching in the

Central High School deprived them of their rights to

33a

due process and equal protection of the laws as guar

anteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

16. Defendant contends that if any issue arises from

the pleadings, or the evidence, the sole question involved

is whether the School Board has violated the constitu

tional rights of any teachers employed by the defendant

School Board during the school year 1964-65.

17. Counsel for the parties announced that all witnesses

are available, and the case in all respects is ready for trial.

The probable length of trial is estimated to be one and

one-half days.

18. Counsel for the parties represent to the Court that

in advance of the preparation of this order, there was a

full and frank discussion of settlement possibilities as re

quired by Local Rule 22(k), and that prospects for settle

ment appear to be remote. Counsel for plaintiff will im

mediately notify the Clerk in the event of a material

change in settlement prospects.

Order on Final Pre-Trial Conference

34a

To: Hugh R. Anderson, Esq.

Ferre, Anderson, Bell & Ogburn

Law Building

Asheboro, North Carolina

Plaintiffs request that the defendant, the Asheboro City

Board of Education, answer under oath in accordance writh

Rule 33 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the fol

lowing interrogatories:

1. Please list for each public school in the Asheboro

School District for the 1965-66 school year:

(a) Grades served in each school;

(b) Number of Negro pupils assigned to each school

as of the most recent date for which figures are

available;

(c) Number of white pupils in attendance at each

school as of the most recent date for which figures

are available;

(d) The planned pupil capacity of each school;

(e) Average class size for each school;

(f) Number of Negro teachers and other administra

tive or professional personnel employed at each

school during the 1964-65 school year;

(g) Number of Negro teachers and other administra

tive or professional personnel employed at each

school for the 1965-66 school (most recent avail

able figures);

(h) Number of white teachers and other administra

tive or professional personnel employed at each

school during the 1964-65 school year;

Interrogatories, dated July 10, 1965

35a

(i) Number of white teachers and other administra

tive or professional personnel employed at each

school for the 1965-66 school year.

2. List the course offerings or curriculum for each school

during the 1964-65 school year.

3. List the course offerings or curriculum planned for

each school during the 1965-66 school year.

4. Please list for each school in the Asheboro School

District for the 1964-65 school year:

(a) The name, educational training, and years of ex

perience of each teacher and administrative or

professional personnel;

(b) The course or courses taught by each teacher

5. Please state for each school in the Asheboro School

District for the 1965-66 school year:

(a) The name of each teacher administrative and

professional personnel whose contract was re

newed for the 1965-66 school year;

(b) The name, educational training, years of experi

ence, and course or courses to be taught by each

teacher, administrative or professional personnel,

who was employed for the first time by the Board

for the 1965-66 school year;

(c) The reason or reasons for not renewing the con

tract of each teacher, administrative or profes

sional personnel who was employed by the School

Board during the 1964-65 school year and not

during the 1965-66 school year;

Interrogatories, dated July 10, 1965

36a

6. State the number and position of each teacher ad

ministrative or professional vacancy, if any, to be

filled by the Board for the 1965-66 school year.

7. State whether the Board has adopted a policy or

resolution providing for employment and assignment

of all teachers, principals and professional personnel

on a nonracial basis.

P lease take notice that a copy o f such answers must be

served upon the undersigned within fifteen (15) days after

service.

This the 10th day of July, 1965.

Interrogatories, dated July 10, 1965

Answer to Interrogatories by Guy B. Teaehey, Super

intendent, Asheboro City Schools and Ex Officio

Secretary, Asheboro City Board of Education

The answers to the interrogatories appearing below

were given by Mr. Guy B. Teaehey, Superintendent, Ashe

boro City Schools and Ex Officio Secretary, Asheboro City

Board of Education, and appear as follows:

1. Question :

Please list for each public school in the Asheboro School

District for the 1965-66 school year :

a. Grades served in each school;

b. Number of Negro pupils assigned to each school as

of the most recent date for which figures are avail

able;

c. Number of white pupils in attendance at each school

as of the most recent date for which figures are avail

able;

d. The planned pupil capacity of each school;

e. Average class size for each school;

f. Number of Negro teachers and other administrative

or professional personnel employed at each school

during the 1964-65 school year;

g. Number of Negro teachers and other administrative

or professional personnel employed at each school

for the 1965-66 school (most recent available figures);

h. Number of white teachers and other administrative

or professional personnel employed at each school

during the 1964-65 school year;

38a

i. Number of white teachers and other administrative

or professional personnel employed at each school

for the 1965-66 school year.

1. A nswer :

The answer to Question 1, a. through i., together with

the answers to Questions 2 and 3, are shown on the at

tached Schedule “A ”, which is incorporated herein by refer

ence.

2. Question :

List the course offerings or curriculum for each school

during the 1964-65 school year.

2. A nswer :

The answer to Question 2 is shown on the attached

Schedule “A ” .

3. Question :

List the course offerings or curriculum planned for each

school during the 1965-66 school year.

3. A nswer :

The answer to Question 3 is shown on the attached

Schedule “A ” .

4. Question :

Please list for each school in the Asheboro School Dis

trict for the 1964-65 school year:

a. The name, educational training, and years of experi

ence of each teacher and administrative or profes

sional personnel;

Answer to Interrogatories by Guy B. Teachey

39a

b. The course or courses taught by each teacher

4, A nswer :

The answer to Question 4 is shown on the attached

Schedule “B”, which is incorporated herein by reference

and which is a Directory of the personnel of the Asheboro

City Schools for the year 1964-65. The teachers, adminis

trative ; and professional personnel are shown in Column 2.

Column 1 shows the educational training with Master’s

degree being signified by an M ; Bachelor’s degree by a B ;

an A certificate by an A ; Graduate Class by a G; Adminis

trator’s certificate by the abbreviation Adm.; and Advanced

Administrator’s certificate by the abbreviation Adv. Adm.

The classes taught by the respective teachers are also

shown in Column 2.

5. Question :

Please state for each school in the Asheboro School Dis

trict for the 1965-66 school year:

a. The name of each teacher administrative and profes

sional personnel whose contract was renewed for the

1965-66 school year;

b. The name, educational training, years of experience,

and course or courses to be taught by each teacher,

administrative or professional personnel, who was em

ployed for the first time by the Board for the 1965-66

school year;

c. The reason or reasons for not renewing the contract

of each teacher, administrative or professional per

sonnel who wras employed by the School Board during

the 1964-65 school year and not during the 1965-66

school year;

Answer to Interrogatories by Guy B. Teachey

40a

5 . A nswer :

The teachers whose contracts were renewed for the 1965-

66 school year are indicated in the attached Schedule “B”

therein Column 3 by an X. The name, educational train

ing, years of experience, and course or courses to be taught

by teachers for the first time for 1965-66 are shown on

the attached Schedule C, which is incorporated herein by

reference. The reasons for not renewing the contracts of

the respective teachers are shown on the attached Schedule

B within Column 4. The following code of abbreviation

indicates the reason:

Resigned indicated by a capital R, resignation requested,

indicated by the abbreviation R-R, resigned for pregnancy

indicated by R-P, retired, age indicated by abbreviation

Ret, principal’s recommendation indicated by PR, offer of

contract by Board refused by teacher indicated by OR, no

vacancy in teacher’s field, by capital NY.

6. Question :

State the number and position of each teacher adminis

trative or professional vacancy, if any, to be filled by the

Board for the 1965-66 school year.

6. A nswer :

The following positions remain to be filled by the Ashe-

boro City Board of Education for the 1965-66 school year.

4 Primary grade teachers

1 Elementary grade teacher

1 Secondary reading instructor

2 Mathematics teachers

Answer to Interrogatories by Guy B. Teachey

41a

1 Administrative Assistant

1 Carpentry instructor, vocational

7. Question :

State whether the Board has adopted a policy or resolu

tion providing for employment and assignment of all

teachers, principals and professional personnel on a non-

racial basis.

7. A nsweb :

Yes, the Asheboro City Board of Education has adopted

a policy by resolution for employment and assignment of

all teachers and professional personnel on a non discrimina

tory basis.

Answer to Interrogatories by Guy B. Teachey

/ s / G u y B. T eachey

Guy B. Teachey

Superintendent, Asheboro City Schools

Ex Officio Secretary, Asheboro City Board

of Education

Schedule “A”

(See Opposite)

Asheboro City Schools

Asheboro, N. 0.

-My 17, 1965

School 1 - 1

Asheboro High

.Grades

3565-66

10-12

b.Negro

Pupils

72 ^

c.White

Pupils

> r n lv U

921

d.Pupil

Capacity

1000

e.Av.Class

Size

25

I .Negro

Teachers

196U-65

g,Negro

Teachers

1965-66

1

h. White

Teachers

196U-65

1*0

i . White

Teachers

1965-66

1*0

2.1961*-1965 3

Curriculum

1 . College Prep.

2 . Business Ed.

3 . General(¥oc.)

.1965-1966

Curriculum

1 . College Prep.

2 . Business Ed.

3 . General(Voc.)

Asheboro Junior High 8-9 89 735 850 27 - 1 30 32 2nd-3rd yrs,

Junior High

2rd-3rd yrs.

Junior High

Balfour 1-6 6 1*07 1*20 29 l(p t) 16 15 Complete

Elementary

Complete

Elementary

Central 1-6 237 35 285 28 21* 11 l(p t) i 1. Complete Elem.

2. College Prep.

3 . Business Ed.

1*. General

Complete

Elementary

F e y e tte v ille Street 7 31* 391 1*30 30 - - 15 16 1st year

Junior High

1st year

Junior High

Lindley Park 1-6 U 10*0 1*75 28 - . 18 17 Complete

Elementary

Complete

Elementary

L o flin , Donna Lee 1-6 - 500 525 28 - - 19 19 Complete

ELementary

Complete

Elementary

McCrary, Charles VI. 1-6 32 518 575 29 - - 21 21 Complete

Elementary

Complete

Elementary

Teachey, Guy B. 1-6 - 527 550 28 - - 20 21 Complete

Elementary

Complete

Elementary

43a

44a

A mended P lan fob Compliance

with

T itle YI op the Civil R ights A ct op 1964

ADOPTED B Y

T he A shebobo City R oabd of E ducation

A shebobo City S chool A dministrative U nit

A shebobo, North Carolina

ON

J une , 1965

The Asheboro City Board of Education hereby records

its intent to comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 and adopts the amended plan described below,

including policies and procedures, which will govern school

organization and pupil and staff assignment in the Ashe

boro City School Administrative Unit. All previous plans

are hereby amended in thenr entirety and superseded

hereby.

I. General Policy

(A) The race, color, or national origin of pupils

shall not be a factor in the assignment to a

particular school or class within a school of

teachers, administrators, or other employees

who serve pupils.

(B) Steps shall also be taken toward the elimina

tion of segregation of teaching and staff per

sonnel in the schools resulting from prior

assignments based on race, color, or national

origin.

(C) No discrimination based on race, color or

or national origin with respect to services,

Schedule “A ”

45a

facilities, activities, and programs sponsored

by or affiliated with the schools of this sys

tem shall be practiced at any time.

(D) Transportation by bus or other means, when

furnished, shall be provided in a single system

without discrimination based on race, color, or

national origin.

(E) Steps will be taken through staff meetings,

class discussions, parent-teacher meetings, and

press releases to prepare pupils, teachers,

staff personnel, and the community for the

changes which will be involved in desegregat

ing the school system.

(F) The entire text of this plan will be published

conspicuously in a newspaper having general

circulation in the school administrative unit

once a week for three successive weeks, and

notice shall be given to parents and guardians

by mail at the time pupil assignments are

made in sufficient time to enable them to under

stand and take advantage of their rights to

initial assignment, reassignment or transfer

for the next school year. Copies of such notice

shall be furnished the Office of Education,

U. S. Department of Health, Education and

Welfare.

II. Policy Governing Assignment of Pupils to Schools

(A) Elementary Schools, grades 1-6

1. Each pupil in grades 1-6 will be assigned,

initially and/or otherwise, to the school

designated to serve the geographic attend

Schedule “A ”

46a

ance zone in which he resides, said zone

lines having been drawn to follow the

natural boundaries or perimeters of a com

pact area surrounding the school.

2. A request for reassignment or transfer of

any pupil to a school outside the zone of

residence made by parent or guardian

within 15 days of the date on which assign

ment notice is mailed will automatically

be approved without regard to race, color,

or national origin within the capacity of

the classroom facilities of the school as

determined by standards of the Southern

Association of Colleges and Schools on a

first, second, third, etc. choice basis. In

the event that such capacity would be ex

ceeded if all requests for transfer to a par

ticular school were granted, priority will

be given to those applying for transfer to

that school who reside closest to the school,

without regard to race, color or national

origin. In addition, consideration will be

given to requests for reassignment and

transfer submitted after 15 days of the

date on which assignment notice is mailed

and this will be done without regard to

race, color or national origin, but the ap

proval thereof will not be automatic.

3. At the beginning of any school year after

(but not including) the 1965-1966 school

year, any pupil who in the previous school

year attended a school outside his zone of

residence shall have the right to transfer

Schedule “A ”

Schedule “A ”

and attend the school in Ms zone of resi

dence.

(B) Secondary Schools, grades 7-12

1. Each pupil in grades 7-12 will be assigned,

initially and/or otherwise, to a single

school designated to serve unit-wide the

grade in which he is placed without regard

to race, color, or national origin.

2. Request for reassignment or transfer of

any pupil in grades 7-12 can in no circum

stances be approved.

(C) Pupils to Be Assigned

1. Assignment to Asheboro Schools will be

made only to pupils who reside within the

Asheboro School Administrative Unit, and

pupils who do not reside within the Unit

will not be permitted to attend schools

within the school district.

2. Assignment or reassignment of pupils who

live within the Asheboro City Administra

tive Unit will in no event be made to

schools in another school administrative

unit.

(D) Notice of Assignment

1. Notice of assignment of all pupils eligible

for assignment and who are enrolled in a

school of the system at the end of any

school term will be made by mail to parents

48a

or guardians with report cards within the

week following the close of school.

2. Notice of original assignment shall be made

by mail to parents or guardians of all ap

plicants eligible for original assignment on

or before July 15 of each year. Notice of

assignment of pupils whose applications

are received after July 15 will in each case

be made by mail or by direct personal

delivery at the Office of the Superintendent

or school immediately upon receipt of ap

plication.

III. Background Actions, Policies, and Interpretations

(A) On February 11, 1965, the Board took actions

to:

1. Discontinue secondary grades (7-12) at

Central High School and operate Central

School as an elementary school effective at

the end of the 1964-1965 term.

2. Discontinue the assignment of any pupil

to an Asheboro school if said pupil is not

a resident of the Asheboro school adminis

trative unit.

3. Establish geographic zones as attendance

areas for each of six elementary schools.

4. Authorize approval of requests for change

of assignment made on behalf of any pupil

in grades 1-6 only.

(B) Under policy adopted as shown above, 80 ele

mentary and 65 secondary pupils who in

Schedule “A ”

49a

former years would have been assigned to

Central High School have been or will be as

signed to the Randolph County Schools for

next term. These transfers and the applica

tion of a single teacher allotment formula to

the Asheboro school system will reduce the

number of teaching positions in the Asheboro

system by at least five, probably six.

(C) Under a single assignment policy at the sec

ondary level all pupils in grades 7-12, without

regard to race, color, or national origin, will

attend the same schools in the Asheboro school

unit.

IV. Other Procedures for Administering Pupil Assign

ment Policy

(A) All policy described herein is fully in effect as

of date of adoption of this plan and/or earlier

date(s), and is intended to achieve complete

desegregation of the school system by the be

ginning of the 1965-1966 school term.

(B) A single brief form, “Request for Change of

Pupil Assignment” , will be required for trans

fer or reassignment of pupils in grades 1-6.

Forms may be secured from the Office of the

Superintendent in person or by mail. Requests

will be approved as set forth above if pre

sented within 15 days of date of assignment

notice.

(C) Pupils who move into the school unit during

the summer or during the school term will be

assigned upon application of parent or guard

Schedule “A ”

50a

ian with all rights described above in full

effect. Pupils who move residence within the

unit during the school term or during summer

months may continue with the assignment held

or request a change at will. Pupils who move

residence away from the school unit at any

time must transfer to another school system

immediately thereafter.

(D) Appeals from assignment will not be neces

sary ; requests for transfer of pupils in grades

noted above will be approved up to capacity

of school requested as indicated.

(E) Transportation will be provided to each pupil

eligible for transportation to the school to

which he is assigned on the secondary level or

to the school serving the attendance zone of

his residence at the elementary level.

V. Racial Composition—Elementary Schools

The Board realizes that, despite good faith efforts to

develop an equitable zoning arrangement, there is

some racial imbalance in the zones set up for the

1965-1966 school year for the Balfour School (pre-

dominently white student body), and Lindley Park

School and Donna Lee Loflin School (all white stu

dent body), and for the Central School (predomi

nantly negro student body), as set forth in the “Racial

Date” chart annexed hereto. To a certain extent, the

imbalance at the Lindley Park School will be reduced

due to the assignment to that school of four negro

students (three of whom attended that school during

the 1964-1965 school year) whose requests for trans

Schedule “A ”

51a

fer to that school have been granted. The Board will

study the feasibility of adjusting school zone lines

to correct this situation and believes it may find a

satisfactory solution to this problem effective with

the 1966-1967 school year. The Board will advise the

U. S. Office of Education promptly in the event that

it adopts a different zoning arrangement. In any

event, the rezoning would be designed to further

desegregate the schools of this district.

VT. Policy Governing Employment/Assignment of Staff

and Professional Personnel

(A) Employment and/or assignment of staff mem

bers and professional personnel shall be based

henceforth on factors which do not include

race, color, or national origin and shall be on

a noil-discriminatory basis. Factors to be con

sidered will include training, competence, ex

perience and other objective means of making

evaluation.

VII. Certification

This is to certify that the above Plan for Compliance

was adopted by the Asheboro City Board of Educa

tion in special session on June , 1965.

(Signature) ......................................... ..... ........

Chairman, Board of Education

Schedule “A ”

(Signature) ......... .......................................... .

Secretary and Superintendent

(Date)

52a

Schedule “A ”

(See Opposite) iSF

ASHEBORO CITY SCHOOLS

ASHEBGRO, N. C.

RACIAL DATA

School 1964-1965 1965-1966

Grades Pupils

W N

Teachers

W N ,

Grades Pupils

W N

Teachers

W N ?

Asheboro High 10-12 868 2 40 10-12 927 73 40 1 2

Asheboro J r. High 8-9 689 30 8-9 736 90 29 3

Balfour 1-6 410 16 1-6 418 5 15 1

Central 1-12 581 24 1-6 30 248 10 2

Fayetteville Street 7 432 15 7 397 36 14 2

Lindley Park 1-6 451 3 19 1-6 440 17 1

L oflin , Donna Lee 1-6 506 20 1-6 514 19 1

McCrary, Chas. W. 1-6 526 23 1-6 552 28 19 3

Teachey, Guy B. 1-6 522 20 1-6 542 19 2

Totals: 4404 586 183 24 4556 480 172 12 16

Note: ( 1) Enrollment projection for 1965 -1966 is based on assignments made June

1965 plus anticipated initial assignments of pupils which will be made

on July 15, 1965; it does not reflect movement of pupils from or into

the school unit.

(2) All pupils in grades 7 through 12 will attend the same schools in

1965-1966 without regard to race, color, or national origin.

(3) Staff appointments, incomplete at this time, will be made without

regard to race, color, or national origin.

53a

54a

Schedule “ B”

(See Opposite) I=ip

Asheboro City Schools

Asheboro, North Carolina

~ j . -2 -

•1

ASHEBORO HIGH SCHOOL (continued) — j . j L

L aJ

A. &

3. V

Mrs. Joyce Harrington, English

3lU Shamrock Road /

Phone 625-6694 L : i$■ y

Mrs. Ernestine B. Presnell, Business Education

316 Ridgecrest Road Y

Phone 625-3851*

/ . ?

A. A

> 2 -

Elizabeth Ann Holbrooks, English

825 South Cox Street 0

Phone '* ». ?

M. Reid Prillaman, Guidance Counselor

1*11* Brookwood Drive Y*

Phone 629-1578 C

/ . * !

t.C-

Alec J. Hurst, Admin. A sst., History

828 Oakmont Drive

Phone 629-U932 %

/. B

t . A

j. af

Mrs. Ruby T. Rich, Biology y

853 South Cox Street r*

Phone 625-21*89

/• a

a. A

#•3

Donald Gray Jarrett, Jr., Spanish

936 South Park Street y

Phone 625-21*82 ^

/• 8

»• /)

3. ©

Linda C. Sloop, Homs Economics a

202 South Main Street . f\

Fhone 625-3893

J. 3

Mrs. Wilda B. Kearns, ICT Coordinator

647 Maple Avenue V

Phone 625-3010 r

/ . *

3 /J

Mrs. Ruby B. Smith, Math

251 South Elm Street /> -

Phone 625-1*175

M

2 . A

3.1*

Merle E. Lancaster, Biology

526 West Kivett Street ^

Phone 625-1*994

' i . 1

3./S

William J. Smith, History y

1*08 Dublin Road A

Phone 625-561*8

t j l

3,7

Mrs. Erma T. Long, Math v

181*4 Raleigh Road '

Phone 625-2462

I* M

i.a'

Lee J. Stone, Business, Biology

5l6 West Kivett Street X

Phone 625-2090

/. 5

2 . A

r /

Billy R. Lovette, Dist. Education

Thomasville A

Phone

*• A

5.3*

Edward R. Sugg, Industrial Arts

1021* Pepperidge Road X

Phone 625-5078

7, B

*- A

3. ©

Route 1*, Box 312A

Phone 873-2621*

Business ̂ education Social Studies

I, B Mrs. Anne H. Moore, Business Education

I , A 1020 Greystone Road Y

J . /y Phone 625-1*919

̂ B E. C. Morgan, Math ^

S>. A Route 5 r

J .ly Phone 629-1221*

o Max D. Morgan, Physical Education

101U Oakdale Street

<*>7 Phone 625-5852

Route 1, Denton

Phone UN9-2819

I. $ Donald Thomas, History

V A 908 C liff Road

3 ./y Phone 629-1276

/• g Joe V. Trogdon, Industrial Arts y

A. A 31U Croomcrest Road A

3- 2. Phone 625-1781*

/ . AJ William F. VanHoy, Jr., Social Studies

6* 1507 Mackie Avenue Y

J.*3 Phone 629-1318 f

/• B Patricia Faye Parrish, English

2. A 61*0 East Kivett Street

I .0 Phone 625-4120

{• a

3> V Phone 629-1157

Morris B. Whitson, Math, Biology

70l* Highland Street ^

55a

Schedule “B”

56a

(See Opposite) ISP

ASHEBCRO CITY SCHOOLS

OFFICE OF SUPERINTENDENT

Guy B. Teachey, Superintendent

613 South Park Street

Phone 625-2682

ASHEBCRO, NORTH CAROLINA

DIRECTORY

1961i-1965

& /■ 1

Mrs. Kay R. Craven, Secretary

l86l Howard Avenue

Phone 625-5086

CJ. 3 Coms-u

/. e

*■ A

Charles H. Weaver, Asst. Superintendent J . Q

826 Avondale Road

Phone 625-52U9

Johnny R. Parker, Dir. of Elem.

255 West Liberty Street

Phone 629-9691

Instr.

Mrs. Mildred F. Chrisco, Mm. Secretary

939 C liff Road

Phone 625-5U72

Mrs. Anna C. Shaw, Secretary

1615 Bray Boulevard

Phone 625-5901

Mrs. Marie H. Malpass, Att. Counselor

1035 Shamrock Road

Phone 625-^860

Garrett Cox, Superv. of Maintenance

301; Stowe Street

Phone 625-2595

Carl H. Skeen, Superv. of Cafeterias

111 West Central Avenue

Phone 625-6968 ' '

Mrs. Marion Bailey, Cafeteria Clerk

601; Oakmont Drive

Phone 625-5U1i9

(Jj &L2

/ f C y .p ASHEB0R0 HIGH SCHOOL

/* J) Keith C. Hudson, Principal

i As?. South Elm Street

j | ’ Phone 625-6185

Col. 3 CotM

/ a r - u

• a

3 . f o

I . fA

A - <5

I • /

J. 8

l. A

3.37

/. hf

1. C

7. &

*•. A

i . n

h i

M

%,c

j j i

I'B

}J $

1*1t.c

i . t

/. a

x.A

Mrs. Linda S. Baxter, English^

Route 5, Box Ul2 r

Phone 629-150U

Helen Bostick, French

103 South Main Street

Phone 625-2927

Warren B. Buford, J r., Social Studies

737 Britt Avenue _

Phone 629-1035 A

Katherine Buie, Librarian ^

Franklinville A

Phone 82i;-2835

Mrs. Kittie J. Caveness, Latin, English

Franklinville X

Phone

Mrs. Walker W. Derr, Math .

222 Bossong Drive A

Phone 625-5U01;

Mrs. Mildred T.

Route 2

Phone 625-75U3

Faircloth, English

X

Joseph B. Fields, Band

751 Spencer Avenue

Phone 629-9671;

Mrs. Lena R. Flenniken, English

1103 Arrowwood Road

Phone 625-3608

David B.

Ramseur

Phone

Gallemore, English