Presley v. Etowah County Commission Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 30, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Presley v. Etowah County Commission Brief of Appellants, 1991. f2632c7b-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10b1da59-7654-4bcb-87bc-7fa075d85d20/presley-v-etowah-county-commission-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

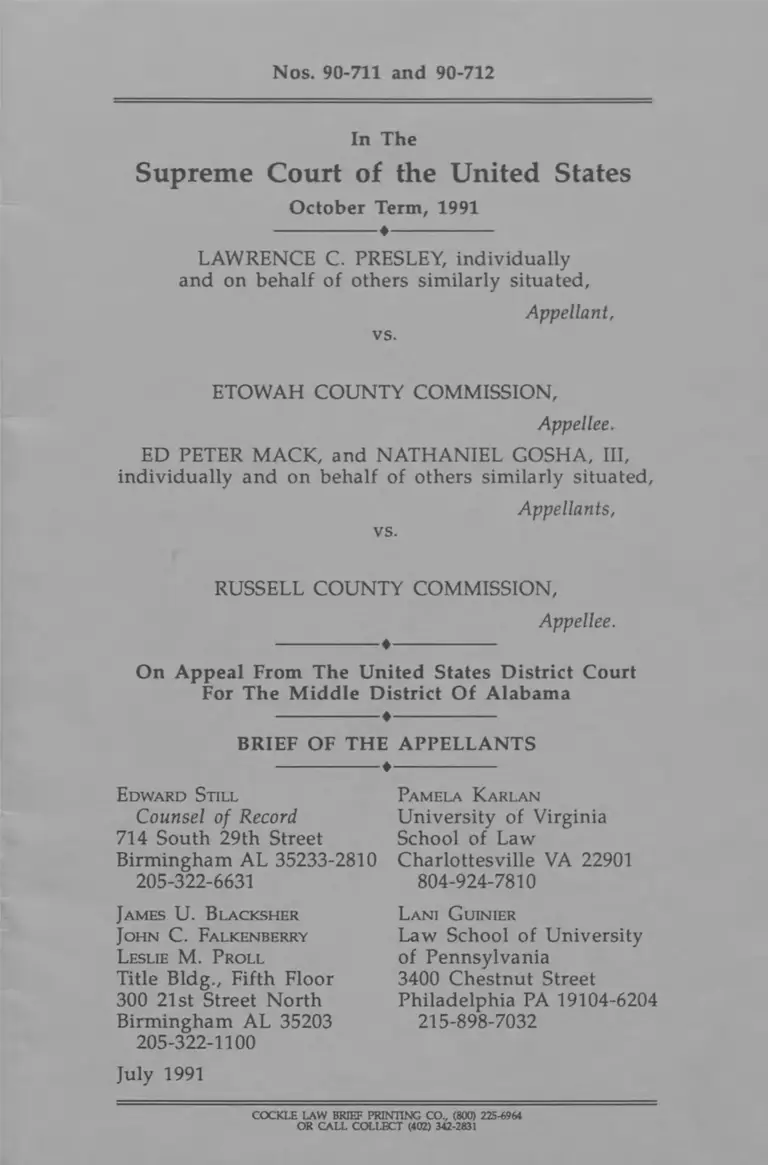

Nos. 90-711 and 90-712

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

----------------♦----------------

LAWRENCE C. PRESLEY, individually

and on behalf of others similarly situated,

vs.

Appellant,

ETOWAH COUNTY COMMISSION,

Appellee.

ED PETER MACK, and NATHANIEL GOSHA, III,

individually and on behalf of others similarly situated,

vs.

Appellants,

RUSSELL COUNTY COMMISSION,

♦

Appellee.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of Alabama

----------------♦----------------

BRIEF OF THE APPELLANTS

----------------♦----------------

E dward Still

Counsel of Record

714 South 29th Street

Birmingham AL 35233-2810

205-322-6631

James U. B lacksher

John C. Falkenberry

L eslie M. P roll

Title Bldg., Fifth Floor

300 21st Street North

Birmingham AL 35203

205-322-1100

Pamela Karlan

University of Virginia

School of Law

Charlottesville VA 22901

804-924-7810

L ani Guinier

Law School of University

of Pennsylvania

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia PA 19104-6204

215-898-7032

July 1991

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

OR CALL COLLECT (402) 342-2831

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

These consolidated cases present variations on the

following basic question: What principles govern the

power of local district courts to interdict the preclearance

process under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 USC

§ 1973c, by ruling that particular changes are beyond the

scope of the Act and need not be submitted for pre

clearance? The Act reserves to the U.S. District Court for

the District of Columbia and/or the Attorney General of

the United States plenary authority to determine whether

changes affecting voting violate § 5. Local district courts

are limited in § 5 cases to determining whether particular

changes are within the scope of the Act and to enjoining

voting changes that have not received the required pre

clearance.

1. Did the Alabama district court improperly deter

mine to be beyond the scope of § 5 a resolution or act

which removes from individual county commissioners

the power independently to manage road and bridge

work in each commissioner's respective district and

places that power in the hands of either the entire seven-

member commission or a county engineer appointed by

the entire commission?

2. Did the Alabama district court impermissibly

confuse substantive questions of § 5 violation with ques

tions about the scope of statutory coverage when it held:

11

a. that reallocations of authority of elected offi

cials "will normally have to be shown to involve officials

with different voting constituencies" before § 5 pre

clearance is required;

b. that a change in the authority of individual

county commissioners need not be submitted for § 5

preclearance if it is "insignificant in comparison" to the

county commission's authority over other matters; and

c. that, even though an unprecleared 1979 law

now shows an obvious potential for discrimination, it

need not be submitted for § 5 preclearance?

3. Did the Alabama district court overstep its lim

ited statutory authority by refusing to defer to determina

tions by the U.S. Attorney General that the changes in

question do fall within the scope of § 5 of the Voting

Rights Act and thus should be submitted for pre

clearance?

QUESTIONS PRESENTED - Continued

Ill

PARTIES IN COURT BELOW

The parties in the court below at the time of the

judgment were plaintiffs Ed Peter Mack, Nathaniel

Gosha, III, Lawrence C. Presley, and defendants Russell

County Commission and Etowah County Commission.

IV

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented............................................................. i

Parties in Court B elow ....................................................... iii

Table of C ontents................................................................. iv

Table of Authorities............................................................. vi

Opinions B elow ..................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction............................................................................... 1

Statutory Provisions............................................................. 1

Statement of the C ase ......................................................... 2

Argument................................................................................. 14

Summary of Argum ent................................................... 14

I. The district court misapplied the "potential

for discrimination" test and decided the sub

stantive issues reserved for the Attorney Gen

eral or the District Court for the District of

Columbia..................................................................... 17

A. The "potential for discrimination" test

looks to the nature of the change in the

voting law, not to its particular circum

stances in the jurisdiction............................ 18

B. Congress drafted § 5 to centralize consid

eration of substantive issues in two fora:

the District Court for the District of

Columbia and the Attorney General.......... 23

C. The local district court improperly con

sidered the substantive issues relating to

the voting law changes in the instant

appeals................................................................. 29

Page

V

2. The district court's consideration of the

merits of the Russell County changes . . 32

2. The district court’s consideration of the

merits of the Etowah County changes . . 35

D. The district court should have accorded

deference to the decision of the Attorney

General that the changes in this case must

be submitted under § 5................................ 37

II. The district court improperly departed from

this Court's prior decisions requiring a State

to preclear a transfer of responsibilities from

elected to appointed officials or changes in

powers of officials................................................... 38

A. This Court has held that the reallocation

of power from one public official to

another must be submitted for pre

clearance under § 5 ....................................... 39

B. District courts hearing similar matters

have likewise held that changes in the

a llo ca tio n of governm ental pow ers

require preclearance....................................... 40

III. The district court decision regarding Russell

County conflicts with decisions of this Court

and the regulations of the Department of Jus

tice regarding the proper "benchmark" for

comparison of an unprecleared change in elec

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

tion-related law......................................................... 42

Conclusion............................................................................... 45

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

C ases:

Allen v State Board of Elections, 393 US 544 (1969) passim

Beer v United States, 425 US 130 (1976).......................... 36

Bolden v City of Mobile, 571 F2d 238 (5th Cir 1978),

aff'g 423 FSupp 384 (SD Ala 1976), rev 446 US

55 (1980), vac and rem 626 F2d 1324 (5th Cir

1980), after remand by US Supreme Court, 542

FSupp 1050 (SD Ala 1982)............................................... 34

Broadhead v Ezell, 348 FSupp 1244 (SD Ala 1972) . . . . 34

Brown v Moore, 428 FSupp 1123 (SD Ala 1976), vac.

& rem. sub nom. Williams v Brown, 446 US 236

(1980), after remand by US Supreme Court, 542

FSupp 1078 (SD Ala 1982), aff'd 706 F2d 1103

(11th Cir 1983), aff'd mem. sub nom. Board of

School Comm'rs v Brown, 464 US 1005 (1983)............ 34

Chisom v Roemer, 59 USLW 4696 (June 20, 1991)........ 26

City of Lockhart v United States, 460 US 125 (1983) . . . . 36

City of Pleasant Grove v United States, 479 US 462

(1987)....................................................................................... 36

City of Rome v United States, 446 US 156 (1980),

aff'g 472 FSupp 221 (D DC 1979) (3-judge court)

....................................................................................... 16, 28, 43

Clark v Roemer, 59 USLW 4583 (June 3, 1991)........ 24, 25

Connor v Finch, 431 US 407 (1977).................................... 29

Corder v Kirksey, 585 F2d 708 (5th Cir 1978)................ 34

County Council of Sumter County v United States,

555 FSupp 694 (D DC 1983) (3-judge co u rt)... 41

Vll

Dillard v Crenshaw County, 640 FSupp 1347, 649

FSupp 289 (MD Ala 1986)........................................passim

Dougherty County Board of Education v White, 439

US 32 (1978)...................................................................passim

Georgia v United States, 411 US 526 (1973).............. 19, 28

Hardy v Wallace, 603 FSupp 174 (ND Ala 1985) (3-

judge court).............................................................................42

Hendrix v McKinney, 460 FSupp 626 (MD Ala 1978)___34

Horry County v United States, 449 FSupp 990 (D DC

1978) (3-judge co u rt)...........................................40, 41, 42

Houston Lawyers' Ass'n v Attorney General of Texas,

59 USLW 4706 (June 20, 1991)...................................... 26

Major v Treen, 574 FSupp 325 (ED Lou 1983).............. 31

McCain v Lybrand, 465 US 236 (1984)......................... passim

McDaniel v Sanchez, 452 US 130 (1981).......................... 27

Morris v Gressette, 432 US 491 (1977).............................. 30

NAACP v Hampton County Election Commission,

470 US 166 (1985).........................................................16, 37

Perkins v Matthews, 400 US 379 (1971). 16, 19, 20, 36, 37

Reynolds v Sims, 377 US 533 (1964)................................... 39

Robinson v Pottinger, 512 F2d 775 (5th Cir 1975)....... 34

Rutan v Republican Party of Illinois,___U S ___ , 111

LEd2d 52 (1990)................................................................... 23

Sims v Amos, 340 FSupp 691 (MD Ala 1972), 365

FSupp 215 (1973) (3-judge court).....................................34

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Vlll

South Carolina v Katzenbach, 383 US 301 (1966)

.........................................................................14, 20, 24, 28, 29

Sumbry v Russell County, CA No. 84-T-1386-E (MD

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES - Continued

Page

Ala 1985)................................................................................. 13

Thornburg v Gingles, 478 US 30 (1986)...................... 28, 31

United States v Sheffield Board of Comm'rs, 435 US

110 (1978).........................................................................16, 37

Statutes and Regulations:

28 CFR § 51 .54 ...........................................................17, 36, 44

28 CFR § 51.55 (1 9 8 7 )........................................................... 32

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Section 2, 42 USC

§ 1973..................................................................... 3, 9, 21, 31

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Section 5, 42 USC

§ 1973c............................................................................... passim

Statutory H istory M aterials:

128 Cong. Rec. S6977-6982 (1 9 8 2 )..................

H.R. Rep. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. (1981).

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982)

Misc:

Dickens, Oliver Twist (1837-38)........................................... 45

Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (First

Perennial Library ed. 1990)............................................. 23

O'Connor, "The Barber," in The Complete Stories

(1971)......................................................................................... 27

. . . 2 7

. . . 27

27, 32

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the district court is unreported. The

opinion of the district court is reproduced beginning at JS

A-l. The order denying the motion to alter or amend the

judgment is reproduced beginning at JS A-42.1

----------------♦----------------

JURISDICTION

The district court denied the requested injunction on

1 August 1990 and denied the motion to alter or amend

the judgment on 21 August 1990. The appellants filed

their respective Jurisdictional Statements in this Court on

26 October 1990. This appeal is taken under 28 USC

§ 1253.

----------------- ♦ ------------------

STATUTORY PROVISIONS

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (42 USC

§ 1973c) is reproduced beginning at JS A-45. The Road

Supervision Resolution and the Common Fund Resolu

tion, adopted by the Etowah County Commission, are

reproduced at A-48 and A-50, respectively, in the Presley

Jurisdictional Statement. Alabama Act 79-652 is repro

duced beginning at A-48 in the Mack Jurisdictional State

ment.

♦

1 Unless otherwise noted, references to "JS" may be found

in either Jurisdictional Statement at the cited page.

1

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In 1964 the practice in both Etowah County and

Russell County was that (1) the County Commission was

elected at-large from residency districts; (2) the County

Commission as a whole adopted a budget that divided

the various road and bridge funds among the county

commissioners in approximately equal amounts;2 (3) each

commissioner had a free hand to determine the priorities

of road and bridge repairs in his or her district; and (4)

each commissioner oversaw the work of his or her own

road crew. The two enactments in question here change

the manner of sharing political power on the commission

from one in which each member controlled a portion of

the budget, with which he or she could satisfy constituent

demands for road repairs, to a system that gives the

white majority effective control over every decision con

cerning the road and bridge system.

Presley v Etowah

The Adoption of Single-Member Districts

Before 1986, Etowah County was governed by four

commissioners elected at large from residency districts

plus a chair elected at large. In 1986 the United States

District Court in the Middle District of Alabama found

that Alabama's general at-large statute applicable to

2 Under Alabama law, many taxes are earmarked for the

support of particular governmental functions. In these counties

the principal sources of funds for the repair and construction

of roads and bridges were the "7c gas tax" and the "Three-R

tax."

3

Etowah County Commission (and several others) was

invalid under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 19653 because

the legislation had adopted and amended the statute with a

racially discriminatory purpose.4 To remedy unlawful dilu

tion of black voting strength caused by the prior at-large

election system, later that year the Court approved a consent

decree providing for the enlargement of the Etowah County

Commissioners from five members elected at large to six

members elected from single-member districts.5 The consent

decree divided the County into six districts, with the single

member district elections held over a four-year period, as the

terms of the incumbents expired.6 Paragraph 3 of the Dillard

consent decree provided:

3 Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 USC § 1973,

provides in pertinent part:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political subdivi

sion in a manner which results in a denial of abridg

ment of the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color . . . .

4 Dillard v Crenshaw County, 640 FSupp 1347, 649 FSupp

289 (MD Ala 1986).

5 Dillard v Crenshaw County, CA No. 85-T-1332-N (MD Ala,

12 November 1986). The Commission has been expanded to

seven members until 1993, to allow the at-large chairman to

complete his term.

6 Districts 5 and 6 were the only ones to elect representa

tives in the special, court-ordered elections in December 1986.

Commissioners Presley and Williams took office in January

1987. Single-member district elections were held in Districts 2

and 3 in the regular 1988 elections, and in Districts 1 and 4 in

1990. All the Old four were re-elected.

4

When the District 5 and 6 Commissioners

are elected in the special 1986 election, they

shall have all the rights, privileges, duties and

immunities of the other commissioners, who

have heretofore been elected at-large, until their

successors take office.

New District 5 is the only district that is majority

black. Plaintiff Presley, who is black, was elected by the

voters of District 5 in a special election in December 1986;

Billy Ray Williams, who is white, was elected from Dis

trict 6. All five of the pre-1986 incumbent commissioners

were white. According to the 1990 Census, the population

of Etowah County is 13.8% black.

The Former System for Road Work

Under the at-large election system, the commission

ers met one day a week to carry out the few legislative

responsibilities they had as a body. During the other 90

percent of their official time, they were physically present

in their respective districts running their respective road

and bridge operations. Hitt Depo. at 10-11.7 The chair

was the only commissioner who worked at the court

house. The chair managed the courthouse buildings and

grounds and supervised the financial records but had no

part in the road and bridge operations. Hitt Depo. at 15,

24.

The four associate commissioners were "road" com

missioners; their residency districts were administrative

7 The case was submitted to the three-judge court on

depositions and exhibits, so there is no formal transcript of a

trial.

5

"road" districts, and each had virtually unfettered

authority to run the road and bridge operations in his

district (all Etowah County commissioners have been

males). Each road commissioner had sole management

authority over all construction and repair of roads,

bridges and the like in his district, including equipment,

employees, and road subcontracts. Hitt Depo. at 10-11.

Each commissioner had a shop in his district and con

trolled his own budget; road and bridge funds were

divided equally among the four road districts. Hitt Depo.

at 20-25. Some decisions such as contracts had to be

approved by the entire commission, but the commission

always deferred to the choices of the commissioner in

whose district the work would be performed, according

to the testimony of Chairman Hitt. JA 54. Chairman Hitt

had lost his supervisory powers over the road and bridge

budget as a result of a local act passed in 1985. Hitt Depo.

at 17, 20.

The construction and maintenance of roads and

bridges is the one area of county government over which

the county commission has effective political discretion.

The commission has no taxing authority. JA 64. It is

completely dependent on revenues established by state

law and mostly received from state agencies. JA 55-57. A

review of the county's budget shows that virtually all the

general fund and all other special funds are dedicated to

predetermined spending requirements and/or are con

trolled by other elected officials, such as the sheriff, the

probate judge, tax assessor, etc. E.g., PI. Ex. L.

6

The Reaction of the Incumbents to the New Commissioners

When the District 5 and 6 commissioners took their

seats in January 1987, the four incumbent at-large com

missioners ("the Old Four") refused to yield any of their

road and bridge powers, notwithstanding the require

ment of the Dillard decree. The Old Four continued to

operate as though there were no new members of the

commission. The Old Four agreed on the road and bridge

budget among themselves and submitted it directly to the

county clerk, Commission Chairman Hitt testified. Hitt

Depo. at 29. They informed the new members (by a "To

Whom It May Concern" letter) that the commissioners for

Districts 1 through 4 "agree to do the maintenance on all

the county roads in District 5 and District 6. . . . " PI. Ex.

Y.8 In effect, the Old Four commissioners banished Pre

sley, Williams, and Chairman Hitt to political limbo.

Chairman Hitt testified that Presley was left with no

administrative duties at all. Hitt Depo. at 74.

The 1987 Resolutions

The Old Four formalized their monopoly over road

and bridge operations in the resolutions at issue in this

action, adopted 25 August 1987. One resolution ("the

Road Supervision Resolution"), adopted over the objec

tions of the new commissioners, provides that each of the

Old Four commissioners "shall oversee and supervise the

8 The case was submitted to the district court on deposi

tions and exhibits, so there is no record citation to the intro

duction and admission of exhibits as usually required by

Supreme Court Rule 24.5.

7

road workers and the road operations assigned to the

road shop[s] located in District 1[, 2, 3, and 4]" and "shall

jointly oversee, with input and advice of the County

Engineer, the repair, maintenance and improvement of

the streets, roads and public ways of all of Etowah

County." Road Supervision Resolution, 1-4, and 7 (jS

A-48). The resolution used the numbers of the old rural

districts, even though one of the road shops is now

located in Presley's District 5. That resolution assigned

Commissioner Presley to "oversee and supervise mainte

nance employees and the repair, maintenance and opera

tion of the Etowah County Courthouse" and the other

new com m issioner to "oversee and supervise the

employees of the Engineering Department of Etowah

County and the operations of that department." Road

Supervision Resolution, n 5 and 6 (JS A-48). It further

directed the two new commissioners to "jointly oversee

the maintenance and operations of the Etowah County

Farmers Market." Road Supervision Resolution, H 8 (JS

A-48). Even though one of the four road shops is now

physically located in the majority black district repre

sented by appellant Presley, the District 2 commissioner

continues to supervise it.

The second resolution ("the Common Fund Resolu

tion ), also adopted over the objections of Presley and

Williams, formalized the control of the Old Four commis

sioners over the entire road and bridge budget. Continu

ing the pre-resolution and pre-D illard practice of

allocating the road and bridge budget equally among all

commission districts would have required six shares

instead of four. So the Old Four resolved to discontinue

formal allocation of the budget among the districts. They

8

instituted a new common fund that the Old Four would

control jointly, as a formal matter, and that they could

reallocate among themselves informally.

[A] 11 monies earmarked and budgeted for

repair, maintenance and improvement of the

streets, roads and public ways of Etowah

County [shall] be placed and maintained in

common accounts, not be allocated, budgeted or

designated for use in districts, and [shall] be

used county-wide in accordance with need, . . . .

Common Fund Resolution, H 1 (JS A-49). This second

August 1987 resolution made the Old Four's monopoly

explicit by assigning control of the road work to "the

road workers of Etowah County operating out of the four

present road shops located in the County." Common

Fund Resolution, *1 2 (JS A-49). The remnants of the

formal allocation of the road and bridge budget among

Districts 1-4 were retained in a grandfather clause, which

preserved the control of each at-large incumbent over any

unspent FY 1986-87 monies in his road district budget.

Common Fund Resolution, f 3 (JS A-49).

Each September when the commission adopts the

annual county budget, the "no" votes of Presley and

Williams have no effect whatsoever on the Old Four's

plans for road and bridge operations. PI. Exs. Q, M and L.

The Old Four make up the road and bridge budget

among themselves, send it directly to the county clerk

bypassing the Chairman and District 5 and 6 commission

ers, and then vote their budget through with their solid,

four-vote majority. JA 58; Hitt Depo. at 29, 32-34; PI. Exs.

Q, M, and L. Informally, the Old Four continue the old

practice of allocating control over equal shares of the

road and bridge budget among themselves. JA 76-77.

9

The Old Four divided $1.4 million among their four

districts in FY 1987, $1.9 million in FY 1988, and $2.1

million in FY 1989. JA 76. Each of the Old Four has

virtually unfettered authority over his one-fourth of the

road and bridge budget. Each decides how the money is

to be spent, whom to hire, whom to promote, and with

whom to contract. JA 58-59; Hitt Depo. at 32, 63, 68-69;

Presley Depo. at 10-11. The county clerk continues to

report the amount of road and bridge funds spent in each

of the four former districts, with no road and bridge

expenditures in Districts 5 and 6. The District 5 and 6

commissioners must come, hat in hand, to one of the Old

Four to plead their case for road work within their dis

tricts. Hitt Depo. at 71; Presley Depo. at 23-32.

The Present Suit

Commissioner Presley, representing a class of black

citizens in Etowah County, sued to enjoin the enforce

ment of the two resolutions unless they were precleared

under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act.9 A three-judge district

9 Appellants Presley, Mack, and Gosha and William Amer

ica (Escambia County commissioner) had earlier brought suit

under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act and Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. Presley claimed that the two Etowah county

resolutions were being administered in a discriminatory way.

Mack and Gosha claimed that the county unit plan in Russell

County was being administered in a discriminatory way. Later,

when they discovered that the resolutions and the change to

the county unit plan had not been submitted for preclearance,

they amended their complaint to ask for relief under § 5. Their

other claims (under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act) are still

pending in the district court. Commissioner America dismissed

his claims against Escambia County.

10

court issued an injunction against only the Road Supervi

sion Resolution. The district court held that "the potential

for discrimination posed by" the Road Supervision Reso

lution "is blatant and obvious;" that the "resolution strip

ped the voters in districts 5 and 6 of any electoral

influence over . . . commissioners" responsible for road

management, JS A-20. It therefore enjoined the enforce

ment of the Road Supervision Resolution unless Etowah

County obtained preclearance of it within 60 days, JS

A-28. Etowah County has not submitted the Road Super

vision Resolution to the Attorney General or the District

Court for the District of Columbia.

The district court, in a split opinion, held that

Etowah County did not need to submit the Common

Fund Resolution for preclearance for the following rea

sons:

It is true that the reallocation of authority

embodied in the common fund resolution

involved officials with different voting constitu

encies. . . . We conclude, however, that the real-

location of authority embodied in the common

fund resolution was, in practical terms, insig

nificant in comparison to the entire Commis

sion's authority, both before and after the

disputed change, to allocate funds among the

various districts, and thus to effectively autho

rize or refuse to authorize major road projects

on the basis of a county-wide assessment of

need.

JS A-18-19. One district judge dissented from this conclu

sion, JS A-32 et seq. Judge Thompson focused on the way

in which the commissioners actually used their powers

and concluded, "A commissioner's real authority lies

. . . in how those funds are used after they are allocated."

11

JS A-32. The district court unanimously agreed that the

Road Supervision Resolution should be enjoined unless it

were submitted for preclearance. ]S A-20-21 and A-27.

Mack v Russell County

Alabama Act 79-652 transferred from the Russell

County Commissioners to the Russell County Engineer

all functions, duties, and responsibilities for roads, high

ways, bridges, and ferries. This centralized control is

called "the unit system" in Alabama. Before the Act pas

sed, each commissioner had controlled the road work in

his or her own district.

Despite its transfer of important governmental func

tions from the supervision and control of elected county

commissioners to the (appointed) county engineer, nei

ther the County Commission nor any State official sub

mitted Act 79-652 for preclearance. The Department of

Justice made a written request in 1989 that it be submit

ted. When the County refused to do so, the appellants

Mack and Gosha brought this action.

At the time the 1979 act was adopted, the Russell

County Commission consisted of five commissioners

elected at large from four residency subdistricts; three

rural districts had one commissioner each and Phenix

City (the largest city in the county) had two seats on the

commission. The commissioners residing in the rural dis

tricts exercised exclusive discretion and control over the

road shops, road equipment, materials, expenditures and

employees in their respective districts. Each commis

sioner was responsible for maintaining a county work

shop and for maintaining a road crew. Belk Depo. at 18;

12

Adams Depo. at 16. Before the adoption of the unit sys

tem, each "commissioner had a road crew that he was in

charge of and that he - even though he had a foreman,

you know, he made the assignments and pretty generally

called the shots on what work was done and where and

so forth." Adams Depo. at 11. Former Representative

Charles Adams was the primary sponsor of Act 79-652.

Each commissioner also controlled hiring, firing, and

assignment of personnel in his or her road shop. Belk

Depo. at 12. This amounted to substantial employment

authority, because the road and bridge system is a major

employer in Russell County government. Adams Depo. at

22. Road and bridge expenditures represent the majority

of the county's budget and of public monies over which

the county government exercises discretionary authority.

The budget of the county engineer is $1.8 million. McGill

Depo. I at 18. Before implementation of Act 79-652,

appropriations from the budget were made on the basis

of road and bridge districts. McGill Depo. I at 18, 19, 22.

In May 1979, the Russell County Comm ission

adopted a resolution that placed all county road construc

tion, maintenance, personnel and inventory under the

supervision of the County Engineer and requested the

Russell County legislative delegation to enact this change

as law. Def. Ex. 1, Belk Depo. In July 1979 the Alabama

Legislature passed Act 79-652, which converted the pro

cess for governing the road and bridge budget and opera

tions to a "unit system." The Act provides:

All functions, duties and responsibilities for the

construction, maintenance and repair of public

roads, highways, bridges and ferries in Russell

13

County are hereby vested in the county engi

neer, who shall, insofar as possible, construct

and maintain such roads, highways, bridges and

ferries on the basis of the county as a whole or

as a unit, without regard to district or beat lines.

The Russell County Commission is now composed of

seven commissioners elected from single-member dis

tricts, under a consent decree entered 17 March 1985, in

Sumbry v Russell County, CA No. 84-T-1386-E (MD Ala).

The decree provided for elections from single-member

districts beginning in 1986 and was designed to remedy

unlawful dilution of black voting strength caused by the

prior at-large election system. Nathaniel Gosha, III, and

Ed Peter Mack, the first black county commissioners in

Russell County history, were elected in 1986 from Dis

tricts 4 and 5, respectively, each of which has a black

voter majority. According to the 1990 Census, the popula

tion of Russell County is 38.6% black.

Commissioners Mack and Gosha (appellants in this

Court) petitioned the district court for an injunction to

restrain appellee Russell County Commission from

implementing Act 79-652, unless the statute receives pre

clearance under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 USC

§ 1973c.10 The district court ruled Russell County did not

have to submit Act 79-652 for preclearance. JS A-16-18.

Judge Thompson dissented, partly on the grounds that

the at-large commissioners were de facto accountable to

the voters in their respective districts. Thus, he argued,

there had been a shift of responsibility from district com

missioners to an appointed at-large official. JS A-34-35.

----------------- «------------------

10 See footnote 9.

14

ARGUMENT

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits a

covered State or locality from implementing any change

in its standards, practices, or procedures with respect to

voting until it obtains preclearance - that is, a determina

tion that the proposed change has neither the purpose

nor the effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on

account of race - from the Attorney General of the United

States or the District Court for the District of Columbia.

The purpose of § 5 was "to shift the advantage of time

and inertia from the perpetrators of the evil to its vic

tims," South Carolina v Katzenbach, 383 US 301, 328 (1966).

A local three-judge district court must determine

only whether the voting change in question has a "poten

tial for discrimination." Dougherty County Board of Educa

tion v White, 439 US 32, 42 (1978). This Court intended for

local district courts to limit their inquiry to the nature of

the voting-law change, not to search for discrimination in

the circumstances of the particular factual situation.

Congress drafted § 5 to centralize consideration of

the substantive preclearance issues in two fora: the Dis

trict Court for the District of Columbia and the Attorney

General. To reverse the time-consuming, expensive, and

legally burdensome case-by-case method of challenging

proliferating changes in voting practices case by case,

Congress also placed all the burdens of proof and delay

on the covered jurisdictions. The district court below

fundamentally frustrated this statutory enforcement

scheme and exceeded its jurisdiction by engaging in sub

stantive consideration of the merits of the changes in

15

question and placing the burden of proof on the private

plaintiffs.

The district court below acknowledged that " 'real-

location[s] of authority' among government officials or

bodies may constitute changes affecting voting under sec

tion 5." JS A-10 (emphasis added). The district court

should have proceeded no further once it found that the

changes at issue had "the nature of the changes in election

practices . . . which required preclearance. . . . " McCain v

Lybrand, 465 US 236, 250 n.17 (1984) (emphasis added).

Every change affecting voting is required by statute to

receive preclearance, even one that seems innocent of

discriminatory purpose or effect. Only the D.C. District

Court and the Attorney General are empowered to

declare the change free of discrimination. The District

Court foreclosed that consideration.

The changes in this case reallocate significant power

from each commissioner to the whole commission (acting

by majority vote) or to an official appointed by the whole

commission. This Court has held that such power real-

locations must be submitted for preclearance under § 5.

Allen v State Board of Elections, 393 US 544 (1969); McCain

v Lybrand, 465 US 236 (1984).

The reasons cited by the Alabama district court for

refusing to require Section 5 preclearance of the chal

lenged changes went beyond the narrow question of the

Act's scope and impermissibly involved the local court in

substantive issues of whether violations exist: (1) the

Russell County change affected officials responsible to

the same electoral constituency; (2) one Etowah County

16

change seemed relatively insignificant to the court major

ity; and (3) even though the Russell County change has

an obvious discriminatory impact today, the potential for

discrimination would not have been as obvious in 1979

when the law was enacted. The district court's analyses

were wrong even as matters of substantive law. But these

are questions Congress has reserved exclusively for the

District of Columbia court and the Attorney General, and

the Alabama district court exceeded its statutory author

ity even by considering them.

The district court should have accorded deference to

the decision of the Attorney General that the changes in

this case must be submitted under § 5. This Court has

held that the Attorney General's decisions on coverage of

the Act are entitled to great deference and has specifically

relied upon the Attorney General's decisions to apply § 5

to certain election-law changes. United States v Sheffield

Board of Comm'rs, 435 US 110 (1978); NAACP v Hampton

County Election Commission, 470 US 166, 179 (1985);

Dougherty County Board of Education v White, 439 US 32, 39

(1978); Perkins v Matthews, 400 US 379, 390-94 (1971).

The Russell County Commission had changed to a

"unit system" in 1979, but had never submitted the

change for preclearance. In 1985 the Commission changed

from at-large elections to single-member districts. In

assessing the 1979 unprecleared change, the court below

looked only at the conditions immediately "before and

after the 1979 change," JS A-21, when the county commis

sion was still elected at large. In City of Rome v United

States, 446 US 156 (1980), this Court explained that when

a change is not submitted until years after its enactment,

the change is to be analyzed in light of the now-existing

17

system rather than in light of the system existing at the

time the unprecleared change was enacted. The Justice

Department regulations are to a similar effect. 28 CFR

§ 51.54(b).

I. The district court misapplied the "potential for dis

crimination" test and decided the substantive issues

reserved for the Attorney General or the District

Court for the District of Columbia.

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 prohibits a

covered State or locality from implementing any change

in its standards, practices, or procedures with respect to

voting until it obtains from the Attorney General of the

United States or the District Court for the District of

Columbia a determination that the proposed change has

neither the purpose nor the effect of denying or abridging

the right to vote on account of race.11 "The legislative

11 Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42 USC

§ 1973c, provides, in pertinent part:

Whenever a [covered] State or political subdivi

sion . . . shall enact or seek to administer any voting

qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard,

practice, or procedure with respect to voting differ

ent from that in force or effect on November 1,

1964, . . . such State or subdivision may institute an

action in the United States District Court for the

District of Columbia for a declaratory judgment that

such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice,

or procedure does not have the purpose and will not

have the effect of denying or abridging the right to

vote on account of race or color, . . . and unless and

(Continued on following page)

18

history [of § 5] on the whole supports the view that

Congress intended to reach any state enactment which

altered the election law of a covered State in even a minor

way." Allen v State Board of Elections, 393 US 533, 566

(1969).

A. The "potential for discrimination" test looks to

the nature of the change in the voting law, not to

its particular circumstances in the jurisdiction.

Under the § 5 case law, a local district court must

determine only whether the voting change in question

has a "potential for discrimination." Dougherty County

Board of Education v White, 439 US 32, 42 (1978). If such a

potential exists the local court's responsibility is at an

end: it must simply enjoin the practice; it cannot deter

mine whether the potential has been realized. In this case

the district court improperly used the "potential for dis

crimination" standard as an inquiry into the plaintiffs'

likelihood of success on the merits.

This Court's decisions on "potential for discrimina

tion" reveal that it intended the local district courts make

an inquiry into the nature of the voting-law change,

rather than into the circumstances of the particular fac

tual situation. This Court first used the "potential for

discrimination" rubric in Dougherty, 439 US 32, 42 (1978):

(Continued from previous page)

until the court enters such judgment no person shall

be denied the right to vote for failure to comply with

such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice,

or procedure . . . .

19

"Thus, in determining if an enactment triggers § 5 scru

tiny, the question is not whether the provision is in fact

innocuous and likely to be approved, but whether if has a

potential for discrimination." The first clause of that for

mulation negates any inquiry into the eventual outcome

of the preclearance process. The Court made this point

even more forcefully by the cases it cited in support of its

proposition: Georgia v United States, 411 US 526, 534

(1973); Perkins v Matthews, 400 US 379, 383-385 (1971);

Allen v State Board of Elections, 393 US 544, 555-556, n 19,

558-559, 570-571 (1969). See, Dougherty, 439 US at 42.

In Georgia v United States, the Court held that redis

tricting - by its nature, without regard to its particular

circumstances - possesses a potential for discrimination.

The Perkins Court approvingly quoted the originating

district judge in the case on the role of the local three-

judge district court:

The only questions to be decided by . . . the

three judge court to be designated, is whether or

not the State of Mississippi or any of its political

subdivisions have acted in such a way as to

cause or constitute a voting qualification or pre

requisite to voting or standard, practice or pro

cedure with respect to voting within the

meaning of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which

changed the situation that existed as of Novem

ber 1, 1964 . . . .

Perkins, 400 US at 384. The Perkins Court expanded on

this point by holding that the local district court may not

consider

what Congress expressly reserved for consider

ation by the District Court for the District of

20

Columbia or the Attorney General - the deter

mination whether a covered change does or

does not have the purpose or effect "of denying

or abridging the right to vote on account of race

or color."

Perkins, 400 US at 385.

In Allen the Court held that a change from district to

at-large voting could effect a dilution of voting power;

that a change from election to appointment for an office

"could be made either with or without a discriminatory

purpose or effect;" that increasing the requirements for

independent candidates to gain a ballot position has a

"substantial impact" on voting; and that a new procedure

for casting write-in votes "is different from the procedure

in effect when the State became subject to the Act." Allen,

393 US at 569-570. This Court did not, however, deter

mine for itself whether the Mississippi and Virginia

changes at issue in Allen and its companion cases were in

fact discriminatory; that job was properly left, in the first

instance, to either the Attorney General or the District

Court for the District of Columbia.

In summary, these cases looked to whether the type

of change might cause dilution of the black vote some

where under some circumstances. If it is possible for the

local court to hypothesize some circumstances under

which the change might cause dilution, then the jurisdic

tion cannot avoid the simple burden of submitting its

election-law change to the Justice Department or District

Court for the District of Columbia.

Since the purpose of § 5 was "to shift the advantage

of time and inertia from the perpetrators of the evil to its

victims," South Carolina v Katzenbach, 383 US 301, 328

21

(1966), the meaning of the holding in Dougherty becomes

clear. The plaintiffs need only show that the enactment is

of a type that could be discriminatory. The plaintiff is not

required to show that the new enactment actually is

discriminatory; if that were the standard, every § 5

enforcement proceeding would be turned into a § 2 case.

In these cases, if the district court had looked only at

the nature of the changes, rather than at possible justifica

tions for the changes, the district court would have con

cluded there was a potential for discrimination in the

following ways:

(1) Just as the voting power of the black electo

rate is submerged when at-large elections are used where

there is racially polarized voting,12 the change from a

district road system to a unit system may dilute the

voting power of a black electorate concentrated in a sin

gle district. In an at-large election, blacks may be unable

to elect representatives of their choice; if the county

adopts single-member districts for elections and a unit

system for road work, black voters may be unable to have

their elected representatives carry out the policies desired

by the black electorate.

(2) Changing from individual district decisions

to group (i.e., commission) control over all decisions sub

merges the political power of the district constituency by

making such decisions dependent upon the votes of six

12 For this reason a change from district to at-large elec

tions must be precleared. Allen, 393 US 544.

22

commissioners, five of whom were not answerable to the

voters in the particular district.13

(3) If a minority group was able to turn to one

sympathetic person on a county commission, and the

commissioner was able to respond to the minority's par

ticularized needs, a change to group decision making

would submerge the power of that commissioner, with

out regard to the method of election of commissioners.

(4) Under district-based decisions, individual

commissioners could use their road budgets to bargain

with other commissioners for constituent services of all

sorts. The change to group-based decision making

changes that balance of power, so that the commissioners

representing black voters have no bargaining power

unless the commissioners of the white districts are

divided on an issue. As Justice Scalia, joined by the Chief

Justice and Justices O'Connor and Kennedy, recently

noted in his dissent,

Patronage, moreover, has been a powerful

means of achieving the social and political inte

gration of excluded groups. . . . The abolition of

patronage, however, prevents groups that have

only recently obtained political power, espe

cially blacks, from following this path to eco

nomic and social advancement.

13 The last three aspects of the appropriation and expendi

ture process can also be found in the block grant programs of

the federal government. Under such programs a fund of money

is divided among the several States, with each State deciding

how the money is to be spent within that State. The recipient of

the block grant (a State or one commissioner) has the freedom

to respond to local constituents in deciding how to spend the

block grant within the State or commission district.

23

Every ethnic group that has achieved

political power in American cities has used

the bureaucracy to provide jobs in return

for political support. It's only when Blacks

begin to play the same game that the rules

get changed. Now the use of such jobs to

build political bases becomes an "evil"

activity, and the city insists on taking con

trol back "downtown."

Rutan v Republican Party of Illinois,___U S ___ , 111 LEd2d

52, 88 (1990) (citations omitted).14

This case is about an analogous form of political

power: the ability of commissioners to act with relative

autonomy within their own districts so they may provide

services useful to their black constituents, but which a

white-majority commission or county engineer may not

provide to black constituents.

B. Congress drafted § 5 to centralize consideration

of substantive issues in two fora: the District

Court for the District of Columbia and the

Attorney General.

Congress has given a "substantial" watchdog respon

sibility to the U.S. District Court for the District of

Columbia and the Attorney General of the United States

to ensure that covered jurisdictions do not implement

changes affecting voting unless and until state or local

14 Zora Neale Hurston, an African American writer, made

the same point in one of her novels: "Yo' common sense oughta

tell yuh de white folks ain't goin' tuh 'low [a colored man] tuh

run no post office." Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watch

ing God 37 (First Perennial Library ed. 1990).

24

officials demonstrate they are free from discriminatory

purpose or effect. The Section 5 preclearance process "is

perhaps the most stringent . . . and certainly the most

extraordinary" of the new remedies adopted by Congress

in 1965 "to 'banish the blight of racial discrimination in

voting' once and for all." McCain v Lybrand, 465 US 236,

244 (1985), quoting South Carolina v Katzenbach, 383 US

301, 308 (1966). For the express purpose of radically

reversing the time-consuming, expensive, and legally

burdensome method of challenging proliferating changes

in voting practices case by case, Congress designed a

novel preclearance procedure that was supposed to place

all the burdens of proof and delay on the covered juris

dictions. McCain v Lybrand, 465 US at 243-44. The sheer

number of such changes and the recalcitrance of covered

jurisdictions, which have failed or refused even to submit

many changes for preclearance, has seriously strained the

Attorney General's limited resources.

This Court recently acknowledged that the Attorney

General cannot and usually does not monitor each juris

diction to make sure all changes affecting voting are

being submitted for preclearance. Clark v Roemer, 59

USLW 4583, 4586 [slip opinion at 11-12] (June 3, 1991).

Consequently, private citizens have been forced into the

role of policing covered jurisdictions simply to get

changes submitted under Section 5 and to prevent their

implementation prior to preclearance. Private litigants

must turn to the local federal district courts for this

limited, threshold enforcement function. Allen v State

Board of Elections, 393 US 544 (1969).

Local district courts who overstep their narrowly

restricted roles in Section 5 actions "upset[] this ordering

25

of responsibilities under § 5[,] diminish covered jurisdic

tions' responsibilities for self-monitoring under § 5

and . . . create incentives for them to forgo the submission

process altogether." Clark v Roemer, 59 USLW at 4586 [slip

opinion at 11-12]. The district court's rulings in the

instant cases encourage covered jurisdictions to give

themselves the benefit of the doubt about the need to

preclear changes in the powers of government officers.

Even requests for submission by the Attorney General

can be ignored with impunity. Private citizens will have

to institute three-judge court actions and bear the burden

of convincing local district judges that something

approaching a likelihood of significant discrimination

exists before the covered jurisdictions need begin the

preclearance process. Meanwhile, the changes already

will have been implemented, making it likely the local

district court will permit implementation to continue dur

ing the preclearance process. See Clark v Roemer, 59 USLW

at 4584 [slip opinion at 4],

As the majority opinion below demonstrates, the use

by local district courts of the "potential for discrimina

tion" inquiry is threatening to create a burgeoning new

body of Section 5 caselaw, one that is largely independent

of, but parallel to, the substantive principles developed

by the decisions of the D.C. District Court and the deci

sions and regulations of the Attorney General. All three

of the district judges below agreed that it is usually

impossible to dissociate "potential for discrimination"

inquiries, as they understand them, from substantive

analyses of discrimination in fact. JS A-22 n.21 (majority

opinion) and A-30 (Thompson, ]., dissenting). Unless this

Court acts decisively to stop it, most future developments

26

in Section 5 law will take place in local district courts,

which lack jurisdiction to make substantive determina

tions about the nature or scope of violations. Private

plaintiffs rather than covered jurisdictions bear the bur

den of proving discriminatory circumstances. Covered

jurisdictions will be able to avoid bearing the burdens of

time and inertia.

In Houston Lawyers' Ass'n v Attorney General of Texas,

59 USLW 4706 (June 20, 1991), this Court emphasized (in

a § 2 context) the importance of separating "the threshold

question of the Act's coverage" from substantive issues

about whether a violation has occurred. Id. at 4708 [slip

op. at 6]. See also Chisom v Roemer, 59 USLW 4696, 4698

[slip op. at 9] (June 20, 1991).15 Complex factual issues

and policy considerations are properly reserved for plen

ary evidentiary proceedings to determine whether the

Act has been violated. Engaging these issues at the

threshold of coverage procedurally frustrates the broad

remedial purpose of the Voting Rights Act. This is so

particularly in the § 5 context, where Congress has explic

itly restricted authority to determine violations to the

D.C. District Court and the Attorney General, leaving

local district courts with the limited responsibility of

facilitating the work of the D.C. fora by requiring covered

jurisdictions to submit all changes that may affect the

voting rights of protected minorities.

Congress excluded local district courts from § 5's

enforcement mechanism because it wanted to centralize

15 The question before the Court in Chisom involved only

the scope of coverage of § 2, making it unnecessary to address

the elements of proving a violation or providing a remedy.

27

in Washington a uniform body of case precedents. It also

distrusted the ability of district courts in the covered

jurisdictions to afford sufficient weight to the national

voting rights priorities embodied in § 5's extraordinarily

intrusive procedural and substantive measures.16 The

institutional difficulties Congress feared in local courts

are apparent in the split decision below. The majority

below simply was unprepared to accept the plain lan

guage of § 5's sweeping command, reaffirmed by this

Court's decisions, when it engaged in a balancing of the

white community's "goodgovermint"17 agenda with the

right of blacks to have effective and responsive represen

tatives.18 The district court majority confessed that in

16 In McDaniel v Sanchez, 452 US 130, 151 (1981), this Court

stated, "Because a large number of voting changes must neces

sarily undergo the preclearance process, centralized review

enhances the likelihood that recurring problems will be

resolved in a consistent and expeditious way." The next year,

Congress rejected proposals to allow local district courts to

hear § 5 suits. S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 58-59

(1982); H.R. Rep. 227, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 36 (1981). The

Senate overwhelmingly rejected an amendment which would

have allowed any "appropriate district court" to hear suits

under § 5 of the Act. 128 Cong. Rec. S6977-6982 (1982).

17 Flannery O'Connor, "The Barber," in The Complete Sto

ries 15, 20 (1971).

18 As examples of the district court's intrusion into the

merits of the Russell County Commission's rationales for its

changes, note the following: the district court majority held the

potential for diminution of blacks' voting rights "pales," JS

A-19, in comparison with legitimate local government reforms

that discouraged "corruption in Russell County's road opera

tions," JS A-3, that replaced political "horse-trading," JS A-19,

with more efficient systems that "consolidated the road shops

. . . and streamlined the road work force," JS A-4, and that

(Continued on following page)

28

balancing the concern of freeing covered jurisdictions

from unnecessary federal interference against what this

Court has called "the prophylactic purpose" of § 5,19 it

was opposed to "automatically expanding, where in

doubt, the scope of [§ 5] coverage" JS A-22 n.20.

When it drafted § 5 of the Voting Rights Act, Con

gress exercised its enforcement powers under § 5 of the

Fourteenth Amendment and § 2 of the Fifteenth Amend

ment and made political policy decisions about the

proper fora for enforcing the preclearance provisions.20

Federal courts are bound to respect this legislative choice

and to enforce it both in letter and in spirit. Local district

courts still have important roles to play enforcing other

provisions of the Voting Rights Act, particularly § 2,

where private litigants bear the burden of convincing

local judges, conducting "intensely local appraisals," that

existing practices impair blacks' access to the political

process. Thornburg v Gingles, 478 US 30 (1986). But Con

gress has placed a clear responsibility on covered juris

dictions that seek to change existing practices that may

affect the voting rights of black citizens; they must bear

(Continued from previous page)

changed budget-setting priorities "from a system of designat

ing funds on a district-by-district need basis to one of desig

nating funds on a county-wide need basis without regard to

district lines," JS A-7. Each of these is a determination which is

left by § 5 to the District of Columbia court or the Attorney

General.

19 McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. at 245.

20 South Carolina v Katzenbach, 383 US 301 (1966); Georgia v

United States, 411 US 526 (1973); City of Rome v United States,

446 US 156 (1980).

29

the burdens of proof, time, and inertia in a national

forum before implementing these changes. McCain v

Lybrand, 465 US 236, 243 (1984), citing South Carolina v

Katzenbach, 383 US 301, 328 (1966). The danger of the

decisions below and other § 5 decisions like them from

local district courts21 is that the carefully crafted and

demanding preclearance enforcement scheme designed

by Congress will be seriously, perhaps fatally, side

tracked. If so, black citizens in covered jurisdictions will

lose what arguably has been the most powerful and effec

tive mechanism for safeguarding the right to vote ever

enacted.

C. The local district court improperly considered

the substantive issues relating to the voting law

changes in the instant appeals.

The district court in the instant case, referring to this

Court's opinion in McCain v Lybrand, 465 US 236, 250 n.17

(1985), quickly acknowledged that, as " 'reallocation[s] of

authority' among government officials or bodies," the

Russell County and Etowah County changes at issue here

"may constitute changes affecting voting under section

5." JS A-10 (emphasis added). This conclusion by itself

was enough to trigger § 5, and the local district court

should have proceeded no further. Every change affecting

voting is required by statute to receive preclearance, even

one that seems innocent of discriminatory purpose or

effect. Only the D.C. District Court and the Attorney

21 See, e.g., Connor v Finch, 431 US 407 (1977), listing the 14-

year history of the recalcitrance of a Mississippi three-judge

district court.

30

General are empowered to declare the change free of

discrim ination. Congress established the procedure

requiring the Attorney General to object within sixty days

of submission to serve as "a speedy alternative method of

compliance" that would not "unduly delay implementa

tion of nondiscriminatory legislation. . . . " McCain v

Lybrand, 465 US at 246, quoting Morris v Gressette, 432 US

491, 503 (1977).

Put differently, the threshold question of coverage

was fully resolved once the district court below found

that the changes at issue had "the nature of the changes in

election practices . . . which required preclearance. . . . "

McCain, 465 US at 250 n.17 (emphasis added). By extend

ing its inquiry into the factual circumstances of these

particular changes in quest of "the potential for discrimi

nation," the court below necessarily entered the realm of

"substantive consideration" about the existence of a vio

lation reserved for the D.C. fora (as the district court

actually admitted when it launched its search for the

proper "benchmark for comparison," JS A-9). Some real-

locations of governmental authority may have no con

ceivable adverse impact on minority voting rights or may

be so attenuated in their impact on voting rights that,

notwithstanding the fact they affect the powers of elected

representatives, they undoubtedly do not violate § 5. But

that is not for the local district court to say.

There is no escaping the conclusion that the district

court in this case went far beyond the question of § 5

coverage, that is, whether each challenged change was a

"standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting,"

42 USC § 1973c. Rather, the court impermissibly deter

mined, on the facts of these cases, that violations of law

31

were unlikely. Nothing makes this clearer than the major

ity opinion's disclaimers of having prejudged plaintiffs'

§ 2 claims against the very same voting practices that

remain for the single-judge court. The majority said it had

not reached the issues of whether the unit system "has in

fact been administered with the purpose or effect of racial

discrimination," JS A-18 n.17, or "whether black voters

are denied equal voting rights under the governmental

regimes currently prevailing in Russell or Etowah Coun

ties." JS A-21-22 n.20. It claimed only to have decided

"whether the disputed changes in this case have any

potential impact on voting sufficient to raise them to the

level of 'changes affecting voting.' " Id. Since, as the

district court correctly held in this case, appellants are

not foreclosed from showing at a full trial on their § 2

claims, that the changes in Russell and Etowah Counties

have resulted in a dilution of their voting strength, then

as a matter of logic the district court erred in finding that

there was no potential for discrimination.

This is not a situation where black citizens can hope

to use a § 2 action effectively to override the Attorney

General's decision to grant § 5 preclearance to a chal

lenged voting change.22 Instead, a federal court has held

that, regardless of what evidence is later adduced, the

change could not possibly cause discrimination. Moreover,

in § 5 proceedings, a change should be denied pre

clearance if racial discrimination inheres in the practice

22 Cases in which private citizens won § 2 cases after the

Attorney General had interposed no § 5 objection include

Major v Treen, 574 FSupp 325 (ED Lou 1983), and Thornburg v

Gingles, 478 US 30 (1986).

32

itself, regardless of whether the change has aggravated

the discriminatory impact.23

1. The district court's consideration of the

merits of the Russell County changes

The district court plunged into the forbidden consid

eration of substantive violations when it assessed the

1979 Russell County change, not to determine whether it

affected voting, but to decide whether or not there had

been a "change in the potential for discrimination against

minority voters." JS A-16 (emphasis in original). Without

the aid of a plenary evidentiary hearing, the court made a

factual determination that black voters lost no significant

influence over road and bridge operations when manage

ment was transferred from the commissioner residing in

their district to an engineer appointed by the commission

majority. JS A-16-17.

Once it crossed into violation-assessment territory,

the district court majority then refused to apply the sub

stantive standards announced by the Attorney General.

Without a word of explanation, the court completely

ignored the rule of "substantive consideration" it had

23 28 CFR § 51.55(b)(2) (1987): "In those instances in which

the Attorney General concludes that, as proposed, the submit

ted change is free of discriminatory purpose and retrogressive

effect, but also concludes that a bar to implementation of the

change is necessary to prevent a clear violation of amended

section 2, the Attorney General shall withhold section 5 pre

clearance." This was adopted after Congress endorsed a simi

lar standard. S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 12 n. 31

(1982).

33

recognized earlier in its opinion, that the challenged

change must be compared with the precleared practices

in effect at the time of submission, not those in effect at

the time of enactment. JS A-9-10. The potential for dis

crimination against black Russell County voters if road

and bridge authority was shifted from a single-member

district commissioner to the county engineer "is too

obvious to require discussion." JS A-16. But the court

found irrelevant a court-ordered single-member district

election system that had been precleared in 1985, because

it was not used in 1979 when the unit system change was

made.

By ruling that the 1979 unit system change was

beyond the scope of § 5, the district court relieved the

Russell County government of its statutory burden of

demonstrating that it had neither the purpose nor the

effect of diluting black electoral strength - and foreclosed

the opportunity for black citizens to convince the Attor

ney General or the District Court for the District of

Columbia that it did have such purpose or effect. The

decision thus pretermits consideration of possible factual

circumstances like the following:

(1) Even though all the road commissioners had

been elected in countywide voting, the district residency

requirement by custom and practice made them partic

ularly responsive to the voters in their residency districts,

and as a practical matter black voters, most of whom

reside in one district, lost political influence over road

and bridge operations when authority was shifted to the

county engineer.

34

(2) The county commissioners and local legislators

anticipated in 1979 the coming court-ordered change to

single-member districts that would allow black voters to

elect one or more representatives of their choice. As of

1979 the Fifth Circuit recently had affirmed the district

court judgment striking down at-large elections in

Mobile,24 and district courts had ordered single-member

districts in several Alabama jurisdictions, including the

State legislature.25 The District Court found in Dillard, 640

FSupp at 1356-57 - a case in which Etowah County Com

mission was a defendant - that the Alabama legislature

was well aware of the potential electoral strength of

blacks and had enacted laws on a variety of occasions so

that blacks would not have electoral influence even if

they obtained full and free access to the ballot. The trans

fer to the county engineer of authority over road and

bridge operations was intended to head off the possibility

that a black commissioner would have run these opera

tions in his or her own district - which would have been

24 Bolden v City of Mobile, 571 F2d 238 (5th Cir 1978), aff'g

423 FSupp 384 (SD Ala 1976), rev 446 US 55 (1980), vac and rem

626 F2d 1324 (5th Cir 1980), after remand by US Supreme

Court, 542 FSupp 1050 (SD Ala 1982); Brown v Moore, 428

FSupp 1123 (SD Ala 1976), vac. & rem. sub nom. Williams v

Brown, 446 US 236 (1980), after remand by US Supreme Court,

542 FSupp 1078 (SD Ala 1982), aff'd 706 F2d 1103 (11th Cir

1983), aff'd mem. sub nom. Board of School Comm'rs v Brown,

464 US 1005 (1983).

25 Corder v Kirksey, 585 F2d 708 (5th Cir 1978); Robinson v

Pottinger, 512 F2d 775 (5th Cir 1975); Hendrix v McKinney, 460

FSupp 626 (MD Ala 1978); Sims v Amos, 340 FSupp 691 (MD

Ala 1972), 365 FSupp 215 (1973) (3-judge court); Broadhead v

Ezell, 348 FSupp 1244 (SD Ala 1972).

35

the case after the Dillard decree became effective in 1985.

In this event, the county would have adopted the 1979

change to a county "unit system" for an unlawfully dis

criminatory purpose.

2. The district court's consideration of the

merits of the Etowah County changes

Similarly, the district court's absolution of the 1987

Common Fund Resolution rammed through by the four

holdover commissioners in Etowah County, over the vig

orous objections of the new single-member district com

missioners, foreclosed plenary consideration of the

following evidentiary scenarios:

(1) Even if, in theory, the power of a single commis

sioner to control road and bridge spending within his

district seems "minor and inconsequential" in compari

son to the total commission's power to allocate funds

among the districts, in fact and in practice it was a critical

component of the four holdovers' road and bridge

monopoly, which the district court found to have a "bla

tant and obvious" potential for discrimination, JS A-20.

(2) Like the Russell County situation, Etowah

County's white commission majority adopted the com

mon fund resolution for the racially discriminatory pur

pose of preventing the representative of black voters from

controlling even a part of the road and bridge budget.

The Etowah Common Fund Resolution is different

from the "benchmark" to which any new enactment must

36

be compared.26 In this case, the benchmark would be the

Dillard decree, under which the commissioners elected

from Districts 5 and 6 "shall have all the rights, privi

leges, duties and immunities of the other commissioners,

who have heretofore been elected at large, until their

successors take office." At the time the Dillard decree

became effective, commissioners had the power to make

resource-allocation decisions for their districts. The 1987

resolutions, together and separately, deprive the commis

sioner elected by blacks of that power.

The district court in this case strayed over the line

into the territory reserved for the D.C. District Court and

the Attorney General by deciding, with regard to Etowah

County, that "the reallocation of authority embodied in

the common fund resolution was, in practical terms,

insignificant. . . . " The district court did not hold that the

Common Fund Resolution lacked the "potential for dis

crimination," but that it was insignificant. This Court has

dealt in the past with election changes that might strike

some as "insignificant" - the transfer of a polling place,

Perkins, changes in personnel regulations, Dougherty, the

extension of city limits to include uninhabited territory,

City of Pleasant Grove v United States, 479 US 462 (1987) -

but this Court has held firm to the standard first

expressed in Allen that even "minor" changes affecting

elections and voting must be precleared.

26 28 CFR § 51.54(b). See also, supplemental information to

§ 5 regulations, 52 Fed Reg 486, 487 (6 Jan. 1987), citing Beer v

United States, 425 US 130, 140-42 (1976); City of Lockhart v

United States, 460 US 125, 131-36 (1983).

37

D. The district court should have accorded defer

ence to the decision of the Attorney General

that the changes in this case must be submitted

under § 5.

A decision of a local district court to deny an injunc

tion under § 5 is a de facto preclearance of the election law

change. Since the Attorney General has the primary

enforcement responsibility under § 5, his decisions about

the coverage of the Act ought to be given great deference.

In United States v Sheffield Board of Comm'rs, 435 US 110

(1978), this Court held it should accord deference to the

Attorney General's interpretation of the Act's coverage,