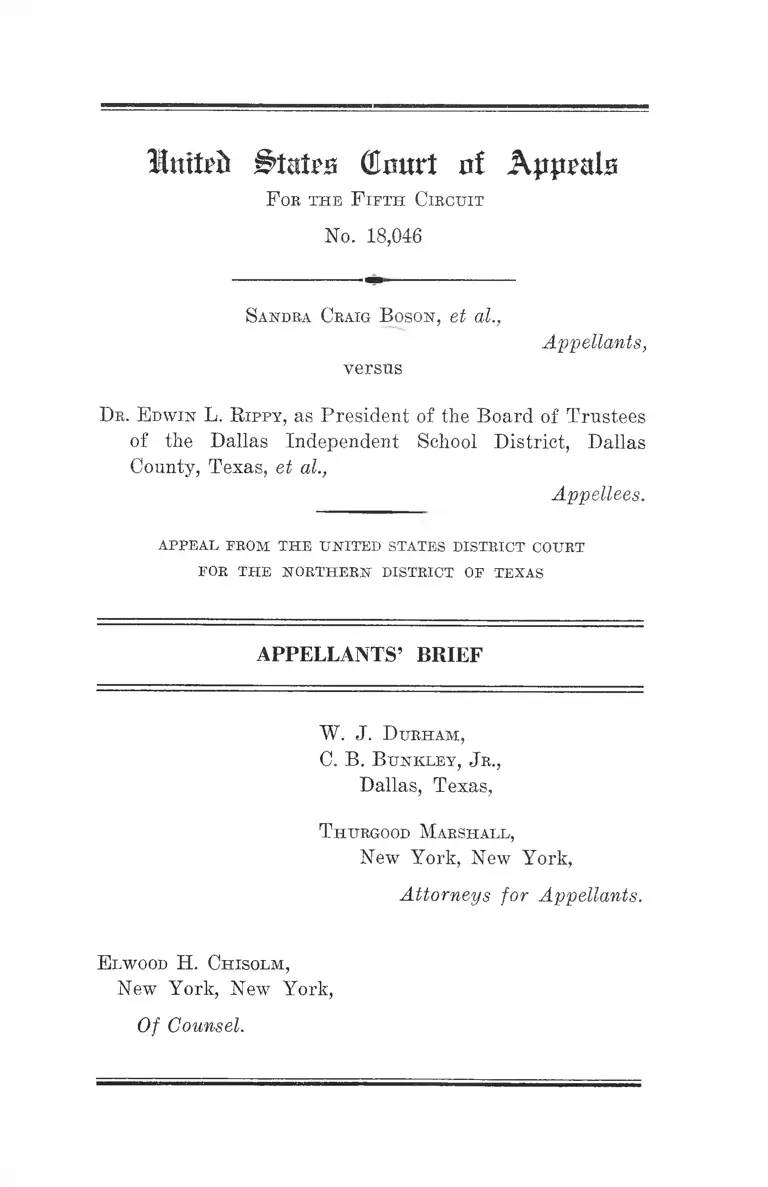

Boson v. Rippy Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boson v. Rippy Appellants' Brief, 1961. ad4cc928-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10cdf68e-aabf-4cfb-99fb-5f4f03f7acf5/boson-v-rippy-appellants-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Mmteb Stairs (timvt of Kppmlz

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 18,046

S andra Craig B oson, et al.,

versus

Appellants,

Dr. E dwin L. R ippy , as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas

County, Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

W. J. D urham ,

C. B. B unkley , J r.,

Dallas, Texas,

T hurgood Marshall,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

E lwood H. Chisolm ,

New York, New York,

Of Counsel.

I n xtvh States (Emtrt nt Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 18,046

S andra Craig Boson, et al.,

versus

Appellants,

Dr. E dwin L. R i p p y , as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas

County, Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

For the fourth time since it was initiated in July 1955

(R. 6), this cause is here on appeal. The previous proceed

ings are reported sub nom. Brown v. Rippy, 233 F. 2d 796,

reversing Bell v. Rippy, 133 F. Supp. 811, cert, denied 352

U. S. 878; Borders v. Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268, reversing Bell

v. Rippy, 146 F. Supp. 485; Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690

(R. 6-8).

On remand from the last cited decision, the District

Court, conformably with this Court’s directions and man

date, entered a “final judgment” on April 16, 1958, which

“restrained and enjoined [appellees] from requiring and

permitting segregation of the races in any school under

2

their supervision, from and after such time as may be

necessary to make arrangements for admission of children

to such schools on a racially non-discriminatory basis, as

required by the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 348 U. S. 294, and retaining

jurisdiction of the cause for such further hearings and

proceedings and the entry of such orders and judgments

as may be necessary or appropriate to require compliance

with such judgment” (R. 2-3).

Some thirteen months thereafter, on May 20, 1959 (R.

5), appellants, alleging that they still were being denied

their constitutional rights to matriculation on a racially

nonsegregated basis and that appellees by positive action

and inaction continued to require and permit the schools

under their supervision to be operated on a racially segre

gated basis for a period of time longer than necessary to

make arrangements for admission of children to such

schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, moved for

further relief in the form of an order requiring appellees

to comply forthwith with the judgment of April 16, 1958,

by immediately operating their public school system on a

nonracial, nondiscriminatory basis and specifically direct

ing appellees to permit appellants and all others similarly

situated to matriculate in such schools without regard to

race or color (R. 8-9).

On July 27, 1959, appellees filed a reply which denied

these allegations and, specially answering, asserted that

at all times they have believed in appellants’ constitutional

rights and done their best to comply with federal and state

law as well as the decisions and orders of this Court and

the Supreme Court; that they have been, and are, conduct

ing litigation with respect to the state law which, under

penalty of a withdrawal of state funds, forbids desegre

gation in any Texas school district without voter approval

3

in a local referendum; that it was physically impossible

and impracticable to desegregate immediately, at the be

ginning of the 1959 fall term, or at the middle of the 1959-

GO school year; that they have been and are keeping abreast

with desegregation elsewhere and considering these devel

opments as they seek to formulate their desegregation

plan; that they have been studying the problem continu

ously since its inception and, pending final determination

of the above mentioned litigation and final formulation of

a desegregation plan, appellants have been and will be

enjoying separate but equal educational facilities; and,

therefore, that not only has a prompt and reasonable start

been made toward desegregation in good faith compliance

with all orders of the federal courts but appellees have

acted and proceeded with all deliberate speed as required

in the Brown decision (R. 12-16).

The hearing on appellants’ motion was held on July 30

(R. 17), whereupon statements were made by counsel and

testimony produced by both sides. In the course of the

opening statement of counsel for appellants, the relief

sought on their behalf was modified to pray in the alterna

tive for an order directing appellees “to bring in a plan

for desegregation within a reasonable time, which would

provide for desegregation beginning September, 1960” (R.

22) .

The evidential facts adduced from the testimony of the

President of the School Board, Superintendent of Schools

and an assistant superintendent in charge of administra

tion are not in dispute: On June 25, 1958 (Rf 34), the

School Board instructed the Superintendent of Schools

that there would “be no alteration of the present status

regarding segregation of the races within the schools of

this district for the school year beginning September,

1958” (R. 33). No similar official statement or policy had

4

been made for the school year beginning September 1959,

“but it [was] not anticipated that there should be a change

in the status for the ensuing school year” (R. 39).

It is not physically impossible to integrate at any time

(R. 54) and the major reason why the School Board hasn’t

desegregated in Dallas is because of the conflict in state

and federal law (R. 59). To integrate beginning in Sep

tember 1959 in compliance with the mandate of federal law

would invoke application of state law; and, resultingly, it

would cut off over $2,620,000 in state funds from the Dallas

school district and have a catastrophic effect on the opera

tion of public schools (R. 54, 55, 71). However, should

desegregation be effectuated in September, 1960, appellees

could fix the budget for the 1960-61 school year despite

the loss of state funds and it would not be a problem

(R. 62).

Appellees have studied and considered at least five alter

native plans for effectuating desegregation (R. 56, 78-79)

and the Board particularly favored the stair-step plan—

a plan which it could put in operation at any time or in

due time (R. 60). But the Board has not formally adopted

any plan nor has it taken any action at all toward starting

actual desegregation at any time in the future (R. 59, 60)

except—as a preliminary to and in aid of the final plan

when adopted (R. 16)—to change several schools from

white to colored because of population shifts and changes

in the scholastic census (R. 26, 37, 81).

Meanwhile appellees have been pursuing their legal

efforts to find out whether the state withdrawal-of-funds

law applies to them (R. 40, 47); have been keeping abreast

of desegregation developments elsewhere by visiting other

communities and reading the current periodical publica

tions and other literature in the subject (R. 51-52, 57, 71-

73, 74, 77-78); have been trying to explain to the public

5

the problems which face the Board in resolving the prob

lem. of desegregation (R. 52-53); have been continuing the

annual scholastic census and study of the age-grade dis

tribution of pupils (R. 58, 66, 71-72); have been consulting

on an informal basis with teachers and administrative staff

on how to meet the problem of desegregation (R. 74-75)

and discovered that there are a number of teachers who

would prefer not teaching mixed classes (R. 68, 82-83).

Finally, appellees professed a willingness to initiate the

local referendum on desegregation provided for under

state law if the Court or appellants desired it (R. 48).

Having heard this evidence the District Court rendered

an opinion from the bench (R. 93-105), denying appellants

any further relief. Subsequently, on August 4, the court

below entered an order which set forth findings that ap

pellees had not only made a prompt and reasonable start

but have proceeded toward good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date with the May 17, 1954, ruling of

the Supreme Court and the judgments of this Court, as

well as the orders entered pursuant thereto (see pp. 1-2,

supra) ; that appellees’ actions constituted good faith im

plementation of all governing constitutional principles;

that some further time should elapse before the District

Court decides on a definite date for desegregation, but

that appellees should initiate the local referendum as pro

vided by state law and take such other steps and studies

as are possible to comply with the present decisions of the

Federal Courts (R. 108-109); and thereupon it specifically

denied appellants’ prayer for an order directing and re

quiring immediate desegregation, but retained jurisdiction

for the proceedings which are to be resumed on April 4,

1960 (R ,110).

6

Specification of Errors

1. The court below erred in finding and concluding as a

matter of law that appellees had made a prompt and

reasonable start and have proceeded toward good faith

compliance at the earliest practicable date with the May

17, 1954, ruling of the Supreme Court and the judgments

of this Court, as well as the orders entered pursuant

thereto, and that appellees’ actions constituted good faith

implementation of all governing constitutional principles.

2. The court below erred in denying appellants’ alter

native prayer for further relief on the ground that some

further time should elapse before the District Court de

cides on a definite date for desegregation and that mean

while appellees should initiate the local referendum as

provided by state law and take such other steps and studies

as are possible to comply with the present decisions of the

Federal Courts.

Argument

Simply stated, the two specifications of error relied upon

present a single question: Does the order entered by the

court below on the record of these proceedings square

with the decisions and directions of this Court on previous

appeals in this case, other apposite rulings of this Court,

courts of coordinate jurisdiction and the Supreme Court?

Appellants submit that this question must be answered in

the negative.

In Borders v. Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268 (1957), this Court,

on evidence strikingly similar to that in this record, held

that appellees must desegregate the public schools in the

Dallas Independent School District. See Dallas Independ-

7

ent School District v. Edgar, 255 F. 2d 455, 456-457 (5th

Cir. 1958). The Court in Borders v. Rippy also made it

clear that appellees must make the necessary arrange

ments to promptly meet their responsibility in the prem

ises, that the court below must ascertain whether appellees

have failed in any respect and that, if they have, it must

require actual good faith compliance with the mandate to

desegregate. 247 F. 2d, at 272; Rippy v. Borders, 250 F.

2d 690, 693, 694 (1957). See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S.

1, 7; Allen v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward Cty.,

Va., 266 F. 2d 507, 510-11 (4th Cir. 1959), cert, denied 4

L. ed. 2d 72, and 249 F. 2d 462, 465 (1957), cert, denied

355 U. S. 953; Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97, 107 (8th Cir.

1958); County School Board of Arlington County, Va. v.

Thompson, 252 F. 2d 929, 930 (4th Cir. 1958), cert, denied

356 U. S. 958; School Board of City of Charlottesville v.

Allen, 240 F. 2d 59, 64 (4th Cir. 1956), cert, denied 353

U. S. 910, 911; Avery v. Wichita Falls Independent School

District, 241 F. 2d 230, 233, 234 (5th Cir. 1957), cert, denied

353 U. S. 938; Jackson v. Rawden, 235 F. 2d 93, 95-96 (5th

Cir. 1956), cert, denied 352 IT. S. 925.

The opinion in Borders v. Rippy was rendered almost

two and a half years ago; Rippy v. Borders was decided

less than six months later; and on April 16, 1958, the

District Court pursuant thereto enjoined appellees from

requiring and permitting racial segregation in the Dallas

public schools from and after such time as may be neces

sary to make arrangements to effectuate racially non-

discriminatory admission of children to such schools (R.

2-3). More than a year had elapsed after entry of this

order, during which appellees had taken no effective action

toward actual compliance with it, and contemplated none

in the future (R. 33, 39), before appellants, agreeably with

this Court’s admonition in the last cited decision that “the

school authorities should be accorded a reasonable further

8

opportunity to meet their primary responsibility in the

premises,” 250 F. 2d, at 694, sought an order requiring

immediate compliance. Under these circumstances, we sub

mit, the order of the court below in the proceedings now

under consideration is inconsonant with its obligation

under applicable decisions and the constitutional mandate.

See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7; Allen v. County School

Bel. of Prince Edward County, Va., supra, 266 F. 2d 507,

510-511; School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v.

Allen, supra, 240 F. 2d 59, 64.

So far as can be gleaned from the opinion delivered by

the District Judge from the bench (R, 93-105) and the

order entered thereafter (R. 108-110), the reasons which

guided him in denying appellants the original as well as

amended prayers for relief and in deferring decision on

setting a definite date for desegregation until April 1960,

if then, were findings that the appellees believe in constitu

tion and laws and courts of the United States and Texas;

that they have not only made a prompt and reasonable start

but are also proceeding toward a good faith compliance at

the earliest practicable date with the first ruling of the

Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases and. the

judgments of this Court, as well as the judgment last

entered below pursuant thereto; and that appellants’

actions, i.e., their litigation to find out whether the Texas

withdrawal-of-state funds law applies to them and their

continuing study of the problem of desegregation, con

stitute good faith implementation of all governing con

stitutional principles (R. 104-105, 108-109).

But this Court has already ruled in this case that such

actions by appellees do not constitute good faith imple

mentation of the controlling constitutional principles,

cannot operate as a defense for unlimited delay, and can

not relieve either appellees or the court below of their

9

constitutional duties and responsibilities. Borders v.

Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268, rehearing denied 247 F. 2d 272.*

See Dallas Independent School District v. Edgar, 255 F.

2d 455; Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690. See also Jackson

v. Raw den, supra, 235 F. 2d 93; McSwain v. County

Board of Education, 138 F. Supp. 570 (E. D. Tenn. 1956);

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177, 181 (E. D. Ky. 1955).

Similarly in a previous decision in this case, this Court

has already rejected as “insufficient” a finding that ap

pellees have made “a prompt and reasonable start” and

are proceeding toward “a good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date” with the May 17, 1954, ruling

in the School Segregation Cases where the record then,

as now (R. 33, 39), revealed that appellees had approved

an official statement sanctioning no alteration in the pres

ent segregation of the races within the schools and one

of them testified categorically that no change in this

status was contemplated for the future. Borders v. Rippy,

247 F. 2d 268, 271-72. What the Court said in Borders

v. Rippy may for emphasis be repeated here: “Faith by

itself, however, without works, is not enough.”

Finally, as for the finding that appellees believe in law

and courts, appellants suggest that such belief is of a piece

with good faith and is also “insufficient.”

* Both the court below and appellees appear to read this per curiam on

petition for rehearing as encouraging, if not directing, the school authorities

to pursue their legal remedies in litigation such as Dallas Independent School

District v. Edgar, 255 F. 2d 455 (5th Cir. 1958) and the similar action now

pending in the state courts. Bather this Court’s advice was: “If, however,

it should be [that this Act is enforced against the Dallas Independent School

District], then the Board of Trustees of the School District and the persons

carrying out the order to be issued by the district court [to require actual

desegregation] are not without their legal remedies.” And for vindication see

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E. D. Ark. 1959), aff’d 28 U. S. L.

Week 3188 (December 11, 1959) (Nos. 458 & 471) ; James v. Duckworth, 170

F. Supp. 342 (E. D. Va. 1959), aif’d 267 F. 2d 224 (4th Cir. 1959), cert,

denied 4 L. ed. 2d 76; Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S. E. 2d 636 (1959) ;

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959); Soxie School District

No. 46 of Lawrence County, Ark. v. Brewer, 137 F. Supp. 364 (E. D. Ark.

1956), aff’d 238 F. 2d 91 (8th Cir. 1956).

10

CONCLUSION

W herefore appellants pray that the judgment below be

reversed and that the court below be instructed to enter an

order requiring appellees to bring in a plan for desegrega

tion within a reasonable time, which would provide for

desegregation beginning in September 1960.

Respectfully submitted,

W. J. D urham ,

C. B. B unkley , J r.,

Dallas, Texas,

T hurgood Marshall,

New York, New York,

Attorneys for Appellants.

E lwood H. Chisolm ,

New York, New York,

Of Counsel.