Champion International Corporation v. International Woodworkers of America Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund et al. as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Champion International Corporation v. International Woodworkers of America Brief for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund et al. as Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1986. 7c912e2b-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10d1733c-de4f-45d1-8f15-39b0702e7671/champion-international-corporation-v-international-woodworkers-of-america-brief-for-the-naacp-legal-defense-and-educational-fund-et-al-as-amici-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

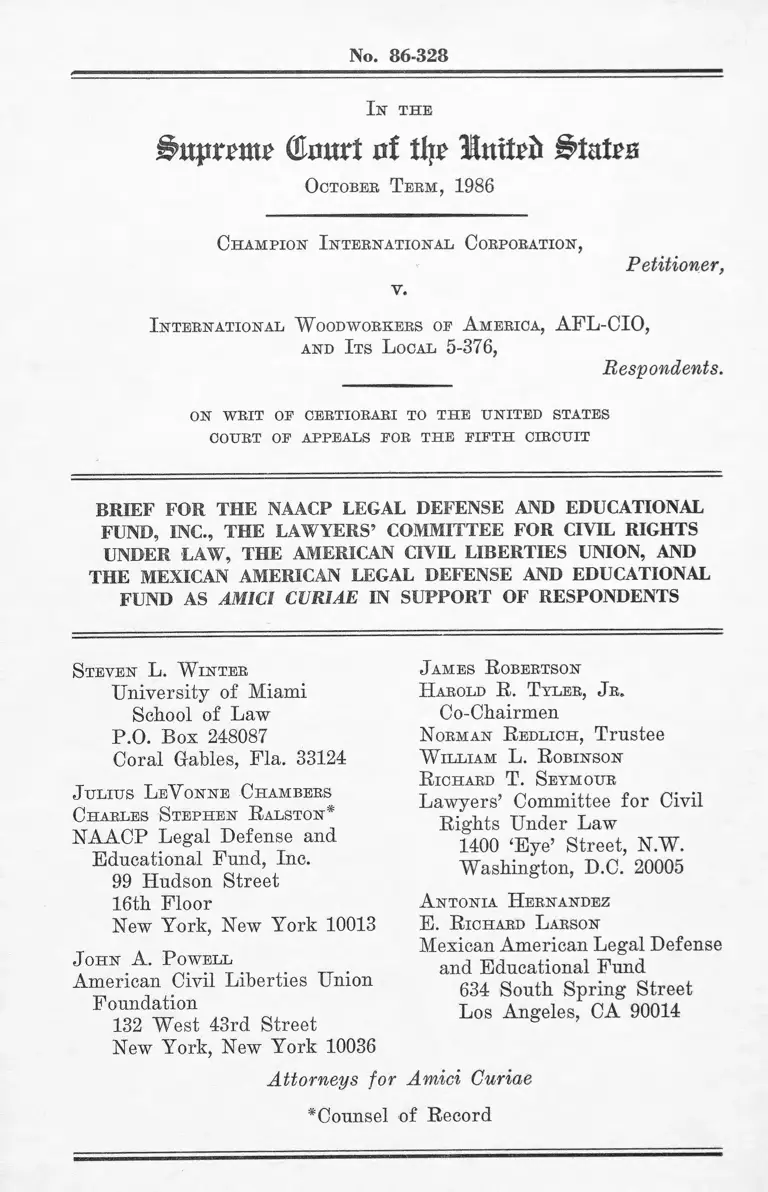

No. 86-328

I n th e

i^ttprrmr (ta rt nf tbr Ittitrti States

O otobee T eem , 1986

C h am pio n I nternational C orporation,

Y.

Petitioner,

I n ternational W oodworkers of A merica, AFL-CIO,

and Its L ocal 5-376,

Respondents.

ON w rit of certiorari to t h e united states

court of appeals for th e f if t h circuit

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

UNDER LAW, THE AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION, AND

THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

S teven L. W inter

University of Miami

School of Law

P.O. Box 248087

Coral Gables, Fla. 33124

J u liu s L eY onne C hambers

C harles S teph en R alston*

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

J ohn A. P owell

American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation

132 West 43rd Street

New York, New York 10036

J am es R obertson

H arold R. T yler , Jr.

Co-Chairmen

N orman R edlich , Trustee

W illiam Ij. R obinson

R ichard T. S eymour

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 ‘Eye’ Street, NW.

Washington, D.C. 20005

A n tonia H ernandez

E. R ichard L arson

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

634 South Spring Street

Los Angeles, CA 90014

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

*Counsel of Record

QUESTION PRESENTED

Can a prevailing civil rights

defendant recover expert witness fees as

part of costs absent adherence to the

standards of Christiansbura Garment Co.

v..__ EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978), when

Congress deliberately incorporated such

expenses in the fee shifting scheme of

the civil rights acts?

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Question Presented . . . . . . . . i

Table of Contents . . . . . . . . . . ii

Table of Authorities.............. iv

Interest of Amici . . . . . . . . . . 1

Summary of Argument . . . . . . . . . 5

ARGUMENT

I. CONGRESS INCLUDED EXPERT

WITNESS FEES AS PART

OF ATTORNEYS' FEES

UNDER THE CIVIL RIGHTO

STATUTES AND, THEREFORE,

THE SPECIFIC STANDARDS

GOVERNING FEE SHIFTING

UNDER THOSE STATUTES

MUST CONTROL.......... 11

aHH CONGRESS WAS SPECIFICALLY

AWARE OF AND LEGISLATED TO

ALLEVIATE THE SIGNIFICANT

PROBLEM OF EXPERT WITNESS

FEES IN ENACTING THE CIVIL

RIGHTS ATTORNEY'S FEES

AWARDS ACT OF 1976 . . . 15

III. CONGRESS SPECIFICALLY

INCORPORATED THE PREEXIS

TING CASE LAW THAT INCLUDED

EXPERT WITNESS FEES AS PART

OF ATTORNEYS' FEES AND

COSTS IN ENACTING SECTION

1988 . . . . . . . . . . 34

ii

IV. TO EXCLUDE EXPERT WITNESS

FEES FROM THE PURVIEW OF

SECTION 1988 WOULD SUBVERT

THE VERY PURPOSE OF THE

ACT BY MAKING IT EFFECTIVELY

IMPOSSIBLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS

PLAINTIFFS TO BRING

MERITORIOUS CLAIMS THAT

INVOLVED COMPLEX OR TECHNICAL

MATTERS, CONTRARY TO

CONGRESSIONAL INTENT . . . 49

CONCLUSION............ ............62

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

444 U.S. 405 (1975)........ 44,60

Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v.

Wilderness Society, 421 U.S.

240 (1975) . ................. passim

Bachman v. Pertschuk, 19 E.P.D.

*|9044 at 6508 (D.D.C.

1979)......................... 62

Baker v. City of Detroit, 483 F. Supp.

919 (E.D. Mich. 1979) .......... 61

Bazemore v. Friday, 478 U.S. ___,

92 L. Ed. 2d 315 (1986) 61

Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886

(1984) . . . . . . . . . . . 4,46,56

Bradley v. School Bd. of City of

Richmond, 416 U.S. 696 (1974) . . . 4

Bradley v. School Bd. of City of

Richmond, 53 F.R.D. 28 (E.D.

Va. 1971) 32,59

Bryan v. Koch, 627 F.2d 612 (2d

Cir. 1980) . . . . . . . . . . . . 59

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441

U.S. 677 (1979).............36,37,48

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S.

482 (1977) . . . . . 58

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434

U.S. 412 (1978) . . 4,7,9,12,13,31,51

iv

4,46,56

City of Riverside v. Rivera, 477

U.S.___, 91 L.Ed.2d 466

(1986) . . ..............

Copper Liquor, Inc. v. Adolph Coors

Co., 684 F.2d 1087 (5th Cir.

(1982) ........................ 49

Crawford Fitting Company v. J. T.

Gibbons, Inc., No. 86-322 . . . . 11

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 8 E.P.D.

f9444 (C.D. Cal. 1974) . . . 44,45,46

EEOC v. Datapoint, 412 F. Supp. 406

(W.D. Tex. 1976) . 44

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97

(1976) . . . . . 60

Fairley v. Patterson, 493 F.2d 598

(5th Cir. 1974).......... .. . 32,42

Foti v. Immigration and Naturalization

Service, 375 U.S. 217 (1963) . . . 40

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971)...................... 45

Hanrahan v. Hampton, 446 U.S. 754

4 (1980)...................... 48

Henkee v. Chicago, St. Paul, M & O

Ry. Co., 284 U.S. 444 (1932) . . 11

Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424

(1983) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4,46

Holy Trinity Church v. United States,

143 U.S. 457 (1892) . . . . . . 33,34

Hughes v. Rowe, 449 U.S. 5 (1980) . .12,37

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978) . 4

v

Jackson v. School Bd. of City of

Lynchburg, Civ. Act. No. 534

(W.D. Va. April 28, 1970) . . . . 33

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express

CO., 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974)................ 4

Jones v. Diamond, 636 F.2d 1364 (5th

Cir. (en banc), cert. granted

sub nom. Ledbetter v. Jones,

452 U.S. 959, amended. 453 U.S.

911, cert, dismissed. 453 U.S.

950 (1981) 43

Jones v. Wittenberg, 330 F. Supp. 707

(N.D. Ohio 1971) . . . . . . . . 33

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

Denver Colo., 439 F. Supp. 393

(D. Colo. 1977).......... 43,47

Lane v. Walker, 307 U.S. 268 (1969) . . 58

La Raza Unida v. Volpe, 57 F.R.D. 94

(N.D. Cal. 1972).......... 21,32,33

Loewen v. Turnipseed, 505 F. Supp.

512 (N.D. Miss. 1981) 43

Maine v. Thiboutot, 448 U.S. 1 (1980). 33

McPherson v. School District #186,

465 F. Supp. 749 (S.D.

111. 1978) . . . . . . . . . . . 43

NAACP V. Button, 371 U.S.415 (1963) . 55

Neeley v. General Electric,90 F.R.D.

627 (N.D. Ga. 1981).......... 43

Newman v. Alabama, 503 F.2d 1320

(5th Cir. 1974) ............. . 60

vi

4Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.,

390 U.S. 400 (1968) ............

Northcross v. Board of Ed., 611 F.2d

624 (6th Cir. 1979) . . . . 43,45,47

O'Bryan v. Saginaw County, Mich.,

No. 79-1297 (6th Cir. Jan. 6,

1981) 43

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978) . . 55

Pyramid Lake Pauite Tribe v. Morton,

360 F. Supp. 669 (D.D.C. 1973). 21

Rios v. Enterprise Ass'n Steamfitters

Local, 400 F. Supp. 993 (S.D.N.Y.

1975), aff'd. 542 F.2d 579

(2d Cir. 1976)........... 44

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d

791 (4th Cir. 1971)........... 45

Sabala v. Western Gillette, Inc., 371

F. Supp. 385 (S.D. Tex. 1974),

aff'd in part, rev'd in part on

other grounds. 516 F.2d 1251

(5th Cir. 1975), rev'd on

other grounds. 431 U.S.

951 (1977).................. 32,44

Ste. Marie v. Eastern Railroad

Association, 497 F. Supp. 800

(S.D.N.Y. 1980) ............ 47,61

Schwegman Bros. v. Calvert Distillers

Corp., 341 U.S. 384 (1951) . . . 39

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691

(M.D. Ala.), aff'd. 409

U.S. 942 (1972) ................. 33

Sledge v. J.P. Stevens, 12 E.P.D.

f11,047 (E.D.N.C. 1976) ........ 44

vii

Stanford Daily v. Zurcher, 64 F.R.D.

680 (N.D. Cal. 1974).......... 46

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) . 59

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 66 F.R.D. 483

(W.D.N.C. 1975) 46

Tennessee v. Garner, 471 U.S. ___,

85 L. Ed. 2d 1 (1985)............ 60

Thornberry v. Delta Air Lines, 25

E.P.D. f31,496 (N.D. Cal.

1980) 61

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. ,

92 L. Ed. 2d 25 (1986)........ 39,58

United States v. Bd. of School

Comm'rs, 573 F.2d 400 (7th

Cir.), cert, denied. 439

U.S. 824 (1978).......... 58

Vasquez v. Hillery, 474 U.S. ___,

88 L. Ed. 2d 598 (1986).......... 58

Welsch v. Likins, 68 F.R.D. 589 (D.

Minn.) aff'd, 525 F.2d 987 (8th

Cir. 1975)..................... 32

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of

Education, 585 F.2d 618

(4th Cir. 1978)................ 45

Wright v. McMann, 321 Supp. 127

(N.D.N.Y. 1970) 33,45

Zuber V. Allen, 396 U.S. 168 (1969). 39

viii

Statutes;

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Award

Act of 1976 .............. passim

42 U.S.C. §1988 ................ passim

Pub. L. No. 94-73 §402 ............ 17

Pub. L. No. 96-481 §204a, 94 Stat.

2327 (Oct. 21, 1980) . . . . 24,37

42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(k) 5,14

42 U.S.C. §2412.....................11

Rule 54, F.R. Civ. Proc............ 43

28 U.S.C. 1 8 2 1 ......................43

28 U.S.C. 1920 .................... 43

Other Authorities;

Awarding of Attorneys' Fees. Hearings

Before the Subcomm. on Courts. Civil

Liberties & the Administration of Justice

of the Comm, on the Judiciary, House of

Representatives. 94th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1975) .......... 21,22,23,24,25,27,28

29,30,35,52

Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards Act of

1976. Source Book: Legislative History.

Committee Print Prepared By the

Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of

the Committee on the Judiciary, United

States Senate (1976) . . 17,18,31,32,38,

39,40,41,42,51,52

ix

The Effect of Legal Fees on the Adequacy

of Representation, Hearings Before the

Subcoxnm. on Representation of Citizen

Interests of the Comm, on the Judiciary,

United States Senate, 93 Cong., 1st Sess.

(1973) . . . . . . . . . 16,20,21,26,30

H. R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976) . . 18,31,32,40,50

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1976) . . 31,38,45,50,51,57

1975 U.S Code Cong. & Ad

News 774 ....................... 17

1980 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad News 4997 . 37

x

No. 86-328

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1986

CHAMPION INTERNATIONAL CORPORATION,

Petitioner,

v.

INTERNATIONAL WOODWORKERS OF AMERICA,

AFL-CIO, AND ITS LOCAL 5-376

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United

States Court of Appeals for the

The Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE LAWYERS

COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, THE

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION

FOUNDATION, AND THE MEXICAN AMERICAN

LEGAL AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICI

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

Interest of Amici*

* Letters of consent to the filing of

this brief from counsel for the

petitioner and the respondents have been

filed with the Clerk of the Court.

2

The NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc. , [LDF] is a

non-profit corporation, incorporated

under the laws of the State of New York

in 1939. It was formed to assist Blacks

to secure their constitutional rights by

the prosecution of lawsuits. The charter

was approved by a New York court,

authorizing the organization to serve as

a legal aid society.

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law was organized in 1963 at

the request of the President of the

United States to involve private

attorneys in the national effort to

assure civil rights to all Americans.

The Committee has, over the past twenty-

four years, enlisted the services of well

over a thousand members of the private

bar in addressing the legal problems of

minorities and the poor.

3

The American Civil Liberties Union

is a non-partisan organization of over

250,000 members, dedicated to defending

the fundamental liberties guaranteed in

the Bill of Rights. Toward that end the

ACLU has acively represented aggrieved

plaintiffs before this Court and in the

lower federal courts. The continuing

availability of attorneys fees and the

related costs of complex and important

constitutional litigation is of crucial

concern to the ACLU and its continued

defense of civil liberties.

The Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund ("MALDEF") is a

national c ivil rights organization

founded in 1967. Its principal objective

is to secure, through litigation and

education, the civil rights of Hispanics

in the United States.

Attorneys for amici have handled

4

cases involving the broad range of civil

rights litigation. Amici have also

participated in many of the leading cases

involving attorneys' fees questions, both

as counsel and as amici curiae.1 and have

provided testimony before Congress on the

need to award fees and costs in civil

rights cases and on the standards that

should govern awards.

The issue raised on this appeal

concerns the standards to be applied in

awarding costs to successful civil rights

litigants and will affect the entire

1 E .a .. Newman v. Piggie Park

Enterprises. Inc.. 390 U.S. 400 (1968) ;

Bradley v. School Board of the City of

Richmond■ 416 U.S. 696 (1974); Hutto v.

Finney. 437 U.S. 678 (1978) ; Johnson v.

Georgia Highway Express Co.. 488 F.2d 714

(5 th Cir. 1974); Christiansburg Garment

Co. v. Equal Employment Opportunity

Comm. . 434 U.S. 412 (1978); Hensley v.

Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424 (1983); Blum v.

Stenson. 465 U.S. 886 (1984); City of

Riverside v. Rivera. 477 U.S. __ , 91

L.Ed.2d 466 (1986)

5

spectrum of civil rights litigation.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court and the panel of

the Fifth Circuit correctly ruled that

petitioner could not recover expert

witness fees as part of its costs. The

en banc Court reached the same result,

but for manifestly the wrong reason. The

basis of its decision would not only

cripple the private enforcement of the

civil rights laws but is also contrary to

the clear intent of Congress.

This case turns on the application

of the Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees

Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. §1988 [the

Act] and the parallel, provision in Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2 000e-5(k): Whether Congress

included expert witness fees as part of

"attorneys' fees and costs" in the fee

shifting scheme of those Acts. The

6

decision in this case will materially

affect the ability of private litigants

to vindicate the rights secured by the

broad range of civil rights legislation.

If plaintiffs in civil rights cases

cannot recoup the substantial expenses

incurred in retaining necessary expert

witnesses, they will be economically

barred from effectively pursuing their

statutory and constitutional rights.

Conversely, if unsuccessful civil rights

plaintiffs can be saddled with their

opponents' often substantial expert

witness fees, then good faith litigation

will be deterred rather than encouraged

as Congress intended.

A careful analysis of the

legislative history of the Act reveals

that Congress was aware that the economic

barriers to private enforcement of these

rights included not just the inability of

7

litigants to pay attorneys' fees, but

also the other costs of efficacious

litigation, including the significant and

sometimes prohibitive expense of expert

testimony. Congress was concerned about

the disparity in litigating strength

between civil rights plaintiffs and their

typically more wealthy opponents, such as

p u b l i c c o r p o r a t i o n s and local

governments.

In legislating, Congress carefully

crafted a statute that included expert

witness fees as part of attorneys' fees

when plaintiffs won and -- by adopting

the Christiansburq standard — shielded

good faith but unsuccessful plaintiffs

from bearing such large fee. It did this

by incorporating and endorsing the prior

case law that had included expert witness

fees as part of "attorneys' fees" to be

covered in the fee shifting provisions of

8

the Act. It made this clear by tracking

of the language of prior attorneys' fees

statutes and explicitly incorporating of

the case law under those statutes; by

explicitly adopting to the "private

attorney general" line of cases; and by

citing as illustrative cases that had

awarded expert witness fees.

Moreover, the legislative debates

make clear that proponents and opponents

of the bill alike understood that the

"attorneys' fees" covered by the Act's

fee shifting scheme included a broad

range of recoverable out-of-pocket

expenses, such as expert witness fees,

not traditionally recoverable as "costs"

under the American Rule.

This Court should affirm the mani

fested intent of Congress. A contrary

ruling would subvert the underlying

purpose of the Act. Congress passed the

9

Act to encourage citizens to vindicate

their rights in the courts, and to enable

them to do so effectively. If expert

witness fees could be imposed on losing

civil rights plaintiffs absent the

protection of the Christiansburg

standard, these plaintiffs will simply be

forced out of the courts. More

importantly, if the en banc court's

reasoning is left intact and expert

witness fees were not recoverable, they

could not be borne by the often indigent

plaintiffs.

Nor could the cost of experts be met

from the attorneys*’ fees. These fees are

based only on reasonable hourly charges

calculated to parallel market rates. If

these fees were diminished by the expense

of employing experts, they would not be

adequate to attract competent counsel as

Congress intended. The result of not

10

recogni z ing that expert fees were

included in fee-shifting will be: that

cases will not be presented effectively;

that attorneys will not be willing to

undertake representation; or that

plaintiffs will be deterred from suing in

the first place. Any of these would

defeat the very purpose of the Act.

11

argument

I. CONGRESS INCLUDED EXPERT WITNESS

FEES AS PART OF ATTORNEYS' FEES

UNDER THE CIVIL RIGHTS STATUTES AND,

THEREFORE, THE SPECIFIC STANDARDS

GOVERNING FEE SHIFTING UNDER THOSE

STATUTES MUST CONTROL_______________

Champion rests its entire argument

on the equitable discretion said to be

conferred on the district courts by

F.R.C.P. 54(d) . Putting aside the

guest ion whether Rule 54 (d) was in fact

intended by its drafters to confer such

discretion,2 it cannot possibly support

Champion's position in this case. For

Rule 54(d) contains a very explicit

disclaimer. Its authorization of the 2

2It is the position of amici that

Rule 54 was not so intended. Henkel v.

Chicago. St. Paul, M. & 0. Ry. Co.. 284

U.S. 444 (1932). Thus we agree with the

arguments made by respondents in the

companion case of Crawford Fitting

Company v, J.T. Gibbons. Inc. . No. 86-

322. As detailed in the text, however,

the specificity of the civil rights fee

shifting scheme makes the question

irrelevant to decision in this case.

12

district courts to act with respect to

costs was never intended to supplant

specific congressional schemes with

respect to fees and costs; the rule

applies to all situations "[e]xcept when

express provision is made . . . in a

statute of the United States . . , ."

Id.

It is our contention, which we

document below, that §1988 is just such

an explicit statutory scheme. Congress

deliberately included expert witness fees

in the fee shifting scheme of the civil

rights statutes so that successful

plaintiffs would be able to recover these

otherwise onerous litigation expenses and

so that unsuccessful, good faith, civil

rights plaintiffs would be shielded under

the standards of Christiansburq Garment

Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412 (1978) (Title

VII), and Hughes v. Rowe. 449 U.S. 5

13

(1980) (§1988), from bearing their

opponents' expert expenses.

Amici. therefore, support the result

reached by the court below: the

prevailing defendant in this civil rights

action may not receive expert witness

fees and other expenses as part of an

award of costs because the district court

specifically held that plaintiffs acted

in good faith and that the defendants had

not met the Christiansburq standard. But

we urge that the basis for the en banc

court's decision is manifestly incorrect

and that this Court should explicitly

affirm the judgment denying costs on the

basis of the district court and the Fifth

Circuit panel's decisions: that the

district court was correct when it held

that Christiansburq was not satisfied

because this action was not frivolous,

unreasonable, or without foundation, nor

14

was it brought in bad faith.

In the remainder of this brief,

amici address solely the issue of the

inclusion in attorneys' fees of expert

witness and other litigation costs and

show that the court of appeals erred in

concluding that expert witness fees are

not recoverable as part of "attorneys'

fees and costs" under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1988

and 2000e-5(d). We first show that

Congress specifically considered this

question when it deliberated and

formulated the fees Act in 1976. We then

show how Congress specifically acted to

include expert witness fees in the Act's

coverage. Finally, we demonstrate that

any contrary conclusion would not only

run a foul of Congress's clearly

manifested intent, but also would

undermine the basic purposes of the Act.

15

II. CONGRESS WAS SPECIFICALLY AWARE OF

AND LEGISLATED TO ALLEVIATE THE

SIGNIFICANT PROBLEM OF EXPERT

WITNESS FEE EXPENSES IN ENACTING THE

CIVIL RIGHTS ATTORNEY'S FEES AWARDS

ACT. OF. 1976._________________________

In order better to understand the

scope of the Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees

Awards Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. §1988 [the

Act], it is necessary to review the

history of that legislation, including

the hearings and events that led to its

passage. As early as 1973, the

Subcommittee on Representation of Citizen

Interests of the Senate Committee on the

Judiciary held six days of hearings on

the problems of economic barriers to

citizen access to lawyers and the courts.

Of these, two days were spent on the

question of modifying the American Rule3

3 As explicated by this Court in

Alveska Pipeline Service Co. v.

Wilderness Society. 421 U.S. 240 (1975):

At common law, costs were not

allowed; but for centuries in

16

to allow for the recovery of costs,

including attorneys' fees, by the

prevailing party in litigation. Great

attention was paid to the then mounting

case law shifting fees in civil rights

and other public interest litigation

under the "private attorney general"

theory. See The Effect of Legal Fees on

the Adequacy of Representation. Hearings

Before the Subcomm. on Representation of

Citizen Interests of the Comm, on the

Judiciary, United States Senate. 93

Cong., 1st Sess. 787-88 (1973) (Statement

England there has been statutory

authority to award costs, including

attorneys' fees. . . . "[T]he

general practice of the United

States is in oposition [sic] to it;

and even if that practice were not

strictly correct in principle, it is

entitled to the respect of the

court, till it is changed, or

modified, by statute." This Court

has consistently adhered to that

early holding.

Id. at 247, 249.

17

of Senator Tunney).

This Court's decision in A1 vesica

Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness

Society. 421 U.S. 240 (1975), gave

impetus to Congress to fashion a statute

that would shift fees in some cases. The

Senate Judiciary Committee reported out

two identical bills that provided for the

shifting of fees in civil rights

litigation, the first as part of the

renewal of the Voting Rights Act in 1975,

See Pub. L. No. 94-73 § 402, 42 U.S.C.

§1973; [1975] U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News

774, and the second, S. 2278, which

eventually passed as § 1988.4 On the 4

4Civil Rights Attorney's Fees Awards

Act of 1976. Source Book: Legislative

History. Texts, and Other Documents.

Committee Print Prepared By The

Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of

the Committee on the Judiciary, United

States Senate (1976) , p. 5. This

Committee Print collects the Senate and

House reports and the proceedings and

debates in both Houses. It will be cited

throughout as "Legis. History ____."

18

House side, the Subcommitee on Courts,

Civil Liberties, and the Administration

of Justice of the Committee on the

Judiciary held three days of hearings on

various attorneys' fees statutes which

resulted in the reporting out of a bill,

H.R. 15460 , which later passed as §1988.

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong., 2d

Sess. 3-4 (1976) . Legis. History 211-

212.

The record before Congress in these

hearings established that the economic

deterrents to civil rights enforcement,

and public interest litigation generally,

included both the problems of attorneys'

fees and the great expense of expert

testimony. Each of the first three

witnesses in the 1973 Senate hearings

raised this problem. One of these was

Dennis Flannery, one of plaintiffs'

counsel in Alveska. He testified

19

regarding the unique effects of economics

on the public interest lawyer:

When a big case such as this comes

into a private law firm, . . . expert

witnesses are contacted, fee

arrangements are made so that the

expert witness can give his full

attention to the case during the

time he is needed, research is

undertaken in a variety of areas

(even areas that are tangential to

the lawsuit, just to make sure you

have covered every aspect). . . .

Now, when a public interest

firm is involved, or when a group of

citizens or even an individual

citizen decides to take on a big

case and to present the views of the

other side in a big case . . . .

there is simply no money up front. .

. .[TJhere is very little money for

such essential things as, for

example, expert witnesses. And so

what I found . . . was that I did

not have any money at all to pay any

expert anything. And so basically

what we had to do was to write or

telephone around the country with

our hat in our hands asking

university people to give us

assistance and to take some time off

from their heavy class workload and

give us whatever assistance they

could. But at no time could we

actually say to an expert, for

example, give us three weeks, we

want you down here in Washington, we

want to go over this technical

material with you, we want you to be

20

prepared to be a witness at trial,

if we go to trial, and we realize

this takes a lot of time and we will

pay you a fee. This is precisely

what the other side was doing. But,

we could not do that . . . .

As a result, the public

interest lawyer must pare off very

important issues — that might even

be winning issues — simply because

they are either too technical or too

big, or require too much expenditure

of money.

Senate Hearings. supra, at 832-34

(Statement of Dennis Flannery). Senator

Tunney, the chairman of the subcommittee

and later the sponsor of S. 2278, was

clearly impressed by the scope of this

problem, referring to it several times in

the course of the hearings. See id. at

1108, 1127, 1128.5

5 At one point, Senator Tunney

referred to Flannery's testimony

that in a difficult case it cost

tens of thousands of dollars to be

able to conduct the case including

being able to get expert witnesses.

Senate Hearings, supra, at 1108.

21

This record was repeated in the

House. One witness testified about a

party having "to confine its activities

to cross-examination of industry

witnesses because it could not possibly

afford to put on expert witnesses of its

own. . . ." Awarding of Attorneys' Fees,

Hearings Before the Subcomm. on Courts.

Civil Liberties & the Administration of

Justice of the Comm, on the Judiciary,

House of Representative. 94th Cong., 1st

As indicated in the text, other

witnesses before the subcommittee raised

the problem of expert witness fees. J.

Anthony Kline, the lawyer in La Raza

Unida____ v. Voice. 337 F. Supp. 221

(N.D.Cal. 1971), one of the earliest

"private attorney general" cases,

described this imbalance in similar

terms. Senate Hearings. supra. at

799. Another witness described the

expenditure of $20,000 in expert witness

fees which was recouped under the

"private attorney general" theory as part

of fees and costs in Pyramid Lake Pauite

Tribe v. Morton. 360 F. Supp. 669 (D.D.C.

1973) . Senate Hearings, supra. at 812,

816.

22

Sess. 159 (1975). (Statement of Peter H.

Schuck, Consumers Union Inc.)* Others,

representing the Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law, told of

countless other cases that really

ought to be brought because they

represent a situation in which a

statute is not being enforced, but

in which they cannot be brought

because there is no lawyer for them

or because a lawyer might be willing

to take the case, but cannot afford

even the out-of-pocket expenses.

Id, at 100 (Testimony of Armand Derfner

and Mary Frances Derfner, Lawyers' Comm.

for Civil Rights). This testimony

highlighted the importance of expert

witness fees:

These . . . attorneys

private practitioners . . . -— face

an additional problem: because of

the limited resources available to

them in public interest cases, they

are rarely able to afford the

technical assistance of expert

witnesses. . . .

23

Id. at 89.® One witness went so far as

to state that if expert witness fees

were not included, "the very point of the

bills may be defeated." Id. at 136

(Statement of John M. Ferren).

In the hearings that led to the

enactment of §1988, Congress was consis

tently asked to respond to this Court' s

ruling in Alveska invalidating the

"private attorney general" line of

cases.* 7 Several witnesses referred to the

®They added:

When Congress calls upon

citizens ... to go to court to

vindicate its policies and

benefit the entire nation,

Congress must also ensure that

they have means to go to court

and to be effective once they

get there.

Id. at 90.

7 Mr. Derfner testified on behalf

of the Lawyers' Committee that:

In that light, I would like to

speak just for a second about one

specific bill before this committee

24

Final Report of the American Assembly on

Law in a Changing Society which was

convened by the American Bar Association.

which I think does deserve a great

deal of attention, and which ought

to be given priority consideration:

H.R. 9552, introduced by Congressman

Drinan. This is a civil rights

provision. It deals with specific

statutes that would be covered in

specific types of cases. It takes

up the area that was most damaged by

the Alveska decision because it is

in the civil rights area that the

Alveska decision had its most

damaging effect.

House Hearings. supra, at 95-96.

Congressman Danielson noted the piecemeal

nature of the process:

I have a feeling we are

commencing on what is going to be a

. . . quite a bit of legislation

before it is done, and that may take

about 10 years. We will probably

have to do as Mr. Crane suggested

and take care of the more immediate

needs to start with.

I d . at 7 8. Mr. Derfner later

acknowledged the importance of modifying

28 U.S.C. §2412 to shift fees when the

government has brought a frivolous case,

id. at 101, which was the next area in

which the Congress acted. Equal Access

to Justice Act, Pub. Law No. 96-481

§204a, 94 Stat. 2327 (Oct. 21, 1980).

25

It recommended "[e ]nactment of

legislation permitting courts . . . to

award attorneys' fees and expert fees,"

noting civil rights as an important area

of concern and stressing that

" [p]recisely this kind of remedial

legislation is what is urgently needed at

this time." House Hearings. supra. at

67, 126 (1975) (Statement of Charles R.

Hobbs on behalf of the American Bar

Association Special Committee on Public

Interest Practice and Statement of

Charles R. Halpern, Exec. Dir. Council

for Public Interest Law).8

8While the report spoke of a statute

that would apply to all public interest

litigation, these witnesses observed that

it makes sense to concentrate on

those areas where the need is most

dramatic. We concur with Father

Drinan in his H.R. 9552, that the

civil rights area is one where there

is an urgent need for prompt

legislation to permit attorneys' fee

awards in cases to enforce the civil

rights laws.

26

The manifest concern about expert

witness fees was part of a broader

concern for equalizing the resources of

the parties in civil rights cases. In

the Senate hearings, one witness

characterized public interest litigation

as a battle

between David and Goliath. In this

battle, however, Goliath holds the

slingshot as well as the weight

advantage...

It is important, I believe, to

emphasize here, that neither

corporations nor the law firms that

represent their interests need be

the least bit defensive about

leaving no stone unturned in putting

forward their best possible case.

Indeed, the adversary system, not to

mention the canons of legal ethics,

demands no less. The problem is

that under present circumstances the

corporation's citizen interest

adversaries cannot devote anything

approaching a comparable expenditure

of resources to the development of

their side of the case.

Senate Hearings, supra. at 841. The ABA

Id. at 125.

27

testified before the House subcommittee

about:

the need of the public to have both

points of view properly represented.

When the Government is involved, it

is going to give a good run to its

point of view. But too many cases

have been decided by default, the

failure to have a good presentation

on the part of the other side.

House Hearings, supra. at 79 (Statement

of Charles A. Hobbs, Member, Special

Committee on Public Interest Practice of

the American Bar Association). relative

to the civil rights plaintiff, the

opposition frequently has virtually

unlimited resources, often including

expert outside counsel. A federal,

state, or even local agency

defendant can draw upon the public

treasury, and call upon full-time

research assistants, the Federal

Bureau of Investigation or state or

local law enforcement investigators,

and the myriad of support services

which exist for the use of those

agencies. Corporate litigants

likewise often have vast resources,

subsidized by tax deductions, with

which to resist public interest

claims. the result is that,

especially in the larger public

interest case, the sides become

extremely unequal. This fact

28

subverts the American system of

justice, where two equal sides are

expected to face one another in a

vigorous adversary procedure ...

Id. at 89-90 (Statement of the Lawyers'

Committee for Civil Rights Under Law) .

Congressman Danielson of California, a

member of the subcommittee, put it

graphically:

[T]here ought to be a balancing of

the power in our court. It seems to

be fundamentally unfair that one

party is the Government with also

unlimited resources, funds,

personnel, availability of records,

availability of investigating

personnel, and whatnot; on the other

hand you have the private citizen.

What was that thing twisting slowly

in the wind? He is out there all

alone anyway and it is chilly out

there financially.

Id. at 61.

Compounding this problem is the fact

that, in addition to their already

greater resources , civil rights

defendants were able to underwrite these

extensive defenses with what is in fact

public money. This is obvious in the

29

case of governmental defendants, who are

paying litigation costs out of tax money

— including the taxes paid by plaintiffs

and their families. In the case of

corporations,

public tax dollars are in a very

real sense being used to support

that litigation. The corporation's

litigation expenses, its attorneys'

fees, its court costs and all costs

connected with the litigation are

deductible from the corporation's

income tax. and that is win or

lose, frivolous or nonfrivolous,

meritorious or nonmeritorious. So

you really have a built-in beginning

that one side that is litigating the

kind of issues I am talking about is

already being supported by public funds.

Id. at 835-3 6 (Flannery Testimony).

Accord id. at 850 (Testimony of Joseph N.

Onek, Director, Center for Law and Social

Policy);9 * id. at 861 (Derfner Statement);

9Even fee shifting does not totally

redress this imbalance, as he noted:

Furthermore, the Government

exercises no control over the

expenses it will subsidize. If

General Motors chooses to pay its

30

House Hearings. supra» at 161 (Onek

Statement).10

It was this precise testimony that

Congress heeded when it considered and

passed § 1988.

lawyers $200 an hour the Government

still pays one-half. If General

Motors pays its lawyers to eat in

the best restaurants and stay in the

finest hotels, that is okay — Uncle

Sam is going to pay half of it, no

questions asked. This is totally

different from any kind of fee award

system we might have. Under an

attorneys' fee statute the courts

would exercise control over

attorneys' fees and other costs of

litigation.

Id.

10Corporate civil rights violators

can also pass on the costs of their legal

defense to the consumer. Senate

Hearings. supra. at 8 61 (Derfner

Statement). See also House Hearings,

supra at 861 (Testimony of Reuben B.

R o b e r t s o n , III, Public Citizens

Litigation Group). 11

11 Representatives of the Lawyers

Committee on Civil Rights Under Law,

the Council for Public Interest Law,

the American Bar Association Special

Committee on Public Interest

Practice, and witnesses practicing

31

It specifically implemented the

policy of equalizing the resources of the

parties when it adopted a different

standard for fees to a prevailing

defendant. See generally Christiansbura.

supra; Hughes v. Rowe. 449 U.S. 5 (1980).

Noting that defendants are usually

governments, which "have substantial

resources available to them through funds

in the field testified to the

devastating impact of the [Alyeska]

case on litigation in the civil

rights area .... The Committee also

received evidence that private

lawyers were refusing to take

certain types of civil rights cases

because the civil rights bar,

already short of resources, could

not afford to do so. Because of the

compelling need demonstrated by the

testimony, the Committee decided to

report a bill allowing fees to

prevailing parties in certain civil rights cases.

H.R. Rep., supra. at 2-3, Legis. History

210-11. The Senate report acknowledged

that this testimony "generally confirmed

the record presented" at its hearings in

1973. S. Rep., supra. at 2, Legis.

History 8.

32

in the common treasury," H .R .Rep. ,

supra. at 7, Legis. History 215, Congress

was concerned that: "Applying the same

standard of recovery to such defendants

would further widen the gap ... and would

exacerbate the inequality of litigating

strength." Id.

It is significant that §1988 was the

legislative response to Alveska because

it was in the pre-Alveska civil rights

cases that expert witness fees were most

consistently awarded.12 It is well

12 See, ê jg. , Fairley v. Patterson,

493 F. 2d 598, 606 n. 11 (5th Cir. 1974)

(costs of preparing reapportionment plan

in voting rights case); Welsch v. Likins.

67 F.R.D. 589 (D. Minn.) aff/d . 525 F.2d

987 (8 th Cir. 1975) (§1983 suit on

rights of mentally retarded); Sabala v.

Western Gillette. Inc.. 371 F. Supp. 385,

394 (S.D. Tex. 1974) , aff'd in part,

rev'd in part. 516 F. 2d 1251 (5th Cir.

1975) (employment discrimination suit

under Title VII and §1981: attorneys' and

expert witness fees awarded under both

Title VII and "private attorney general"

theory) ; La Raza Unida v. Volpe, 337 F.

Supp. 221 (N.D.Cal. 1971); Bradley v.

School Bd. of City of Richmond. 53 F.R.D.

33

established that a

guide to the meaning of a statute is

found in the evil which it is

designed to remedy; and for this the

c o u r t p r o p e r l y l o o k s a t

contemporaneous e v e n t s , the

situation as it existed, and as it

was pressed upon the attention of

the legislative body.

Holy Trinity Church v. United States. 143

U.S. 457, 463 (1892) . Here, the very

event that precipitated the enactment of

§1988, this Courtis decision in Alveska.

2 8 ( E . D . Va . 19 7 1) ( s c h o o l

desegregation); Jones v. Wittenberg. 330

F. Supp. 707, 722 (N.D. Ohio 1971) (jail

case) ' Jackson v. School Bd. of City of

Lynchburg. Civ. Act. No. 534 (W.D. Va.

April 28, 1970) (school case); Wright v.

McMann. 321 Supp. 127 (N.D.N.Y. 1970)

(prison case: unpublished decree). See

also Sims v. Amos. 340 F. Supp. 691 (M. D.

Ala.), aff'd. 409 U.S. 942 (1972) (award

of attorneys and expert witness fees in

voting rights case under "bad faith"

exception) . La Raza. which involved

violations of environmental statutes, was

cited by Senator Kennedy during the floor

debates as an exalmple of a case

"enforc[ing] the rights promised by

Congress" that would be covered under S

1988. 122 Cong. Rec. 33314 (1976), cited

in Maine v. Thiboutot. 448 U.S. 1, 10 n.9

(1980) .

34

concerned the problem of expert witness

fee costs. See discussion, supra, at 19-

20 (Statement of Dennis Flannery); see

cases cited supra. n. 5. The

indivisibility of the attorneys' fees and

expert witness fee problem was

highlighted "in the testimony presented

before the committees of Congress." Holy

Trinity Church v. United States. 143 U.S.

at 4 64. Thus, it cannot be assumed that

Congress did not intend to include expert

witness fees when it enacted §1988. In

fact, it is clear from the congressional

reports and legislative debates that such

expenses were included.

III. CONGRESS SPECIFICALLY INCORPORATED

THE PRE-EXISTING CASE LAW THAT

INCLUDED EXPERT WITNESS FEES AS PART

OF ATTORNEYS' FEES AND COSTS IN

ENACTING SECTION 1988_______________

The testimony before the House

subcommittee set out the modus operandi

that Congress in fact adopted in

35

restoring the recoverability of fees in

civil rights cases.

The bulk of the nonstatutory

private attorney general cases in

the past few years were cases under

the Civil Rights Laws. These cases,

as well as cases under specific

attorneys' fee provisions of recent

civil rights laws, provided Congress

and the courts with a thorough

education in attorneys' fees in this

area, and resulted in a detailed

body of law on technical questions.

. . . There is thus a clear record

to support the proposition that a

generic provision governing the

entire area should be superimposed

upon the existing patchwork of

specific provisions.

One of the bills before this

Subcommittee, H.R. 9552 . . . would

allow a court, in its discretion, to

award a t t o r n e y s ' fees to a

prevailing party in suits to enforce

the civil rights acts which Congress

has passed since 1866. This bill

follows the language of section 402

of the Voting Rights Act, and of

Titles II and VII of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act. All of these acts

depend heavily upon private

enforcement, and fee awards are an

essential remedy if private citizens

are to have a meaningful opportunity

to vindicate these important

Congressional policies.

House Hearings. supra. at 85. (Lawyers'

36

Committee Testimony).

The committee reports and the

legislative debates make clear that

Congress used the precise language of

Titles II and VII 13 and intentionally

13 Because Congress adopted the

language of earlier statutes, resort to

the "plain meaning" of the words used in

§ 1 9 8 8 w o u l d be p a r t i c u l a r l y

inappropriate. See Cannon v . University

of Chicago. 441 U.S. 754, 717 (1979),

discussed, infra. at p.48.

To take a few words from their

context and with them thus isolated

to attempt to determine their

meaning, certainly would not

contribute greatly to the discovery

of the purpose of the draftsman of

the statute.

Thus, the fact that Congress did not

expressly include expert witness fees, as

it did in other statutes, is not

controlling. Because Congress legislated

in the context of the existing statutory

scheme of attorneys' fees provisions, it

had to adopt the precise wording of those

statutes in order to incorporate the case

law and standards developed under those

provisions. This Court has on several

occasions gone beyond the plain meaning

of the statutory language to look to the

legislative history of Civil Rights

statutes, including §1988, in order to

ascertain their correct publication.

37

Cannon, supra (implied cause of action

under Title IX); Hughes v . Rowe. 449 U.S.

5 (1980) ; Christiansburg Garment Co. v.

E.E.Q.C.. 434 U.S. 412 (1978) (higher

standard for award of fees to prevailing

defendant).

This conclusion is also reenforced

by the legislative history of a later

statute which specifically provides for

expert witness fees. In 1980, Congress

passed the Equal Access to Justice Act,

Pub. Law No. 96-481 §204 (a) , 94 Stat.

2327 (Oct. 21, 1980), amending 28 U.S.C.

§2412. This statute provides for fee

shifting in cases brought by the United

States when its position is not

reasonable in law or f act and

specifically includes expert witness

fees. It is more restrictive than §1988,

placing a ceiling on hourly rates (absent

special circumstances) and positing a

higher standard for recovery of fees. In

passing this statute, which was first

discussed during the hearings and debates

that led to the passage of §1988, n. 7,

supra. Congress was ‘ aware of the

interplay between §2412 and §1988. It

specifically provided that, where both

apply, the broader provisions of §1988

take precedence because "Congress has

indicated a specific intent to encourage

vigorous enforcement ...." H.R. Rep. No.

96-1418 at 18, [1980] U.S. Code Cong. &

Ad. News 4997. Thus, Congress's explicit

incorporation of expert fees in §2412

cannot be read to imply that the failure

to include express language to that

effect in §1988 indicates a contrary

38

adopted the prior case law under these

statutes and the "private attorney

general'*’ theory as recommended at the

hearings. As explicated in the Senate

Report:

S . 2278 follows the language of

Titles II and VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§2000a-3 (b) and §2000e-5(k), and

section 402 of the Voting Rights Act

Amendments of 1975, 42 U.S.C.

§19731(e). . It is intended

that the standards for awarding fees

be generally the same as under the

fee provisions of the 1964 Civil

Rights Act.

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

2, 4 (1976). Legis. History 8, 10.14

intent. Rather, if Congress intended to

include expert fees in the narrower

statute — which was designed merely to

remove deterrents from contesting

unreasonable litigation, then the broader

— -which was one designed to foster the

vigorous assertion of fundamental rights

— cannot be read to exclude it.

14 importance of the committee

report in establishing congressional

intent is well established: "A committee

report represents the considered and

collective understanding of those

Congressmen involved in drafting and

39

Senator Kennedy, one of the sponsors of

the bill, 15 further indicated that the

bill "is intended simply to expressly

authorize the courts to continue to make

the kinds of awards of legal fees that

they had been allowing prior to the

Alveska decision." Legis. History 23.

Similarly, in the House, both

Representatives Railsback and Bolling

noted that the bill merely codified and

restored the pre-Alveska law. Legis.

History 242, 247.

During the floor debate on the House

studying proposed legislation." Zuber v,

Allen. 396 U.S.168, 186 (1969); Thornburg

v. Ginales. 478 U.S. ___, 92 L.Ed.2d 25,

42 n. 7 (1986) .

15 In Schweqman Bros. v . Calvert

Distillers Coro.. 342 U.S. 384 (1951),

this Court noted that: "It is the

sponsors that we look to when the meaning

of the statutory words is in doubt." Id.

at 394-95. S ince Senator Kennedy’s

remarks as sponsor are wholly consistent

with and complementary to the bulk of the

legislative history, they possess added

weight.

40

side, Congressman Drinan, the billf s

sponsor and the author of the committee

report, 16 amplified on the comments in

that report. See H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. 5-5 (1976); Legis.

History 213-214.

T h e C i v i l R i g h t s

Attorney's Fee Awards Act of 1976,

S .2278 (H.R. 15460) is intended to

restore to the courts the authority

to award reasonable counsel fees to

the prevailing party in cases

initiated under certain civil rights

acts. The legislation is

necessitated by the decision of the

Supreme Court in Alyeska Pipeline

Service Corp. against Wilderness

Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975). . . .

Prior to the Alyeska decision,

the 1ower Federal Courts had

regularly awarded counsel fees to

the prevailing party in a variety of

cases instituted under the sections

16 M r . Drinan's exposition is

especially authoritative since he was a

member "of the House Judiciary Committee

responsible for . . . [these] matters,

author and chief sponsor of the measure

under consideration, and a respected

congressional leader in the whole area. .

. " Foti v. Immigration_____and

Naturalization Service. 375 U.S. 217, 23

n. 8 (1963).

41

of the United States Code covered by

§2278___

The Alveska decision ended that

practice, which this bill seeks to

restore. . . .

The language of S.2278 tracks

the wording of attorney fee

provision in other civil rights

statutes such as correction 7 06 (k)

of Title VII -- employment -- of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

phraseology employed has been

reviewed, examined, and inter

preted by the courts, which have

developed standards for its applica

tion. These evolving standards

should provide sufficient guidance

to the courts in construing this

bill which uses the same term. I

should add that the phrase

"attorney's fee" would include the

values of the lecral services

provided by counsel, including all

incidental and necessary expenses

incurred in furnishing effective and

competent representation.

(Comments of Congressman Drinan; Legis.

History 252-255 (emphasis added)).

Congressman Drinan's comments are

particularly important for two reasons.

First, they indicate the explicit intent

of Congress in passing the Act to adopt

the existing case law under Titles II and

42

VII. 17 More importantly, they indicate

that, in restoring the pre-Alyeska

practice Congress was conscious that

e x p e r t witness fees and other

out-of-pocket expenses had been

recoverable even though they were not

traditional "costs." See cases cited,

supra. at n. 12. These non-statutory

costs had been treated by the pre-Alyeska

cases in just the way Congressman Drinan

explained they would be handled under the

Act:

Costs not subsumed under federal

statutory provisions normally

granting such costs against the

adverse party ... are to be included

in the concept of attorneys' fees.

Fairley v. Patterson, supra. 493 F. 2d at

17 Congressman Anderson, one of the

floor managers of the bill, also made

this point at the opening of the floor

debates. Legis. History 236.

43

606 n. 11.18

In 1976 when Congress debated and

passed the Act, there was little doubt

that expert witness fees had been

recoverable under the "private attorney

general" cases as discussed above and

were recoverable under the attorneys'

fees provision of Title VII on which the

18 The incorporation of these

non-statutory costs as part of

"attorneys' fees" is particularly

noteworthy in light of the confusion in

the cases regarding the effect of 28

U.S.C. §§1920 and 1821 on the recover

ability of expert witness fees. Compare

Nprthcross v. Board of Ed.. 611 F.2d 624,

642 (6th Cir. 1979) (recoverable under

§1920)> Keyes.v,. School.District No. 1,

Denver Colo.. 439 F. Supp. 393, 417-18

(D. Colo. 1977) (same); with Neely v.

General Electric. 90 F.R.D. 627 (N.D.

Ga. 1981) (not recoverable under §192 0) ;

with Jones v. Diamond. 636 F.2d 1364 (5th

Cir. 1981) (en banc) (recoverable under

§1988) ; O'Bryan v. Saginaw Mich.. No.

79—1297 (6th Cir. Jan. 6, 1981) (same) ;

McPherson v. School District #186. 465 F.

Supp. 749, 763 (S.D. 111. 1978) (same) ;

with Loewen v. Turnipseed. 505 F. Supp.

512, 519 (N.D. Miss. 1981) (recoverable,

but theory under which awarded is unclear) .

44

Act was modeled.-3-9 Indeed, the award of

expert witness fees to the prevailing

party in Title VII litigation was so well

established that it often went

unchalleged. Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, 8 E.P.D. 1 9444 at p . 5048

("These charges were not challenged by

defendants and are valid"). In

innumerable cases, the lower courts had

awarded such fees without discussion.

See. e.g.. Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody. 19

19EE0C v. Dataooint. 412 F. Supp.

406, 409 (W.D. Tex. 1976), vacated and

rem'd on other grounds. 570 F. 2d 1264

(5th Cir. 1978); Rios v. Enterprise

Steamfitters Local. 400 F. Supp. 993, 997

(S.D.N.Y. 1975), aff'd. 542 F. 2d 579 (2d

Cir. 1976) ; Davis v. County of Los

Angeles. 8 E.P.D. 19444 (C.D. Cal. 1974);

Sabala v. Western Gillette, Inc., 371 F.

Supp. 385, 394 (S.D. Tex. 1974), aff'd in

part, rev'd in part on other grounds. 516

F. 2d 1251 (5 th Cir. 1975) (After the

passage of the Act, Sabala was reversed

by this Court on other grounds. 431 U.S.

951 (1977) ) . See also Sledge v. J.P.

Stevens. 12 E.P.D. 111,047 (E.D.N.C.

1976) (prospective award of fees for

plaintiffs' expert necessitated by

defendants' computerized records).

45

444 U.S. 405 (1975); Griggs,v ,̂.,,DaKe.Power

fiat., 401 U.S. 424 (1971); Robinson v,

LgXlllflr,d.,.-C.aEPL/ 444 F. 2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971).20

The Senate left little doubt about

the case law it intended to incorporate.

The appropriate standards, see

Johnson...v,.Georgia Highway Express.

488 F. 2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974), are

correctly applied in such cases as

Stanford..Dai.lv v , Zurcher, 64 f .r .d .

680 (N.D.Cal. 1974); Davis v. Countv

.gj„LdS-AngeI.e.§., 8 e .p .d . ^9444 (c .d .

Cal. 1974); and Swann v. Charlotte

Mecklenber.g,,. goa.rd._PX_..Education, 66

F.R.D. 483 (W.D.N.C. 1975). These

cases have resulted in fees which

are adequate to attract competent

counsel, but which do not produce

windfalls to attorneys.

S. Rep. No. 94-1101, supra. at 6; Legis.

History 12. These cases were carefully

chosen to include both statutory — Davis

20 Research reveals no reported pre-

1976 Title VII cases in which expert

w i t n e s s f e e s w e r e d i s c u s s e d a n d

disallowed. For post-Act decisions

compare Whealsc.-^__ParbflB— glfag..B d .___ofEd. . , 585 F. 2d 618 (4th Cir. 1978), with

Northeross.v, ... jBd . .of ..Ed. of Memphis, 611

F.2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979).

46

and Swann, supra. — and non-statutory

"private attorney general" — - Stanford

Daily. supra. -- fee awards and to

include a broad range of attorneys' fee

issues: fee computation standards, hourly

rates, bonus awards for the continuation

of the litigation or excellence of

results, expert witness fees, paralegal

and out-of-pocket expenses.21 Davis, in

fact, is one of the pre-Act Title VII fee

awards which specifically included expert

witness fees. And in Swann. more than a

third of the $29,972.33 in costs awarded

by the district court constituted expert

witness fees and expenses.22

21This Court has repeatedly noted

Congress' citation to these three cases

and has relied on them in interpreting

the Fees Act. City of Riverside v.

Rivera. 477 U.S. ___, 91 L.Ed.2d 466, 480

(1986) ; Blum v. Stenson. 465 U.S. 886,

893-894 (1984); Hensley v. Eckerhart, 461

U.S. 424, 430-431 (1983).

22 Amicus NAACP Legal Defense Fund

was of counsel in Swann.

47

Thus, there can be little doubt that

Congress acted deliberately and

intentionally to incorporate an existing

body of case law which clearly allowed

for the inclusion of expert witness fees

and all m a n n e r of r e a s o n a b l e

out-of-pocket expenses23 as part of "fees

and costs." 24

2 3 As phrased by a supporter,

Congressman Seiberling: "All we are

trying to do in this bill is . . . to get

compensation for their legal expenses in

meritorious cases." Id. at 245.

24 Because the legislative history

makes clear that expert witness fees,

like all other out-of-pocket expenses,

are ordinarily recoverable, it would be

contrary to the legislative purpose to

require a higher standard for the

recovery of these expenses. Some of the

lower court opinions have been read to

require that expert testimony be "vital,"

"essential," or "helpful and important."

See Northcross v. Bd. of Ed. . 611 F. 2d

624, 642 (6th Cir. 1979); Ste. Marie v.

Eastern Railroad Association. 497 F.Supp.

800, 813-14 (S.D.N.Y. 1980), rev' d on

other grounds. 650 F.2d 395 (2d Cir.

1981); Keyes v. School District. 439

F.Supp. 393, 418 (D. Colo. 1977) . Amicus

does not agree with such a reading of

these cases. These expenses must

48

In summary:

The provision for counsel fees

in §1988 was patterned upon the

attorney's fees provisions

contained in Titles II and VII

of the Civil Rights Act of

1964....

Hanrahan v. Hampton. 446 U.S. 754, 758 n.

4 (1980) .

The drafters ... explicitly

assumed that it would be

interpreted and applied as

[these provisions] had been

during the preceeding twelve

years.... It is always

appropriate to assume that our

elected representatives, like

other citizens, know the law;

in this case, because of their

repeated references to [these

provisions and the case law],

we are especially justified in

presuming both that those

representatives were aware of

the prior interpretation

and that that interpretation

reflects their intent.

Cannon v. University of Chicago. 441 U.S.

ordinarily be included under §1988, which

was intended to encourage vigorous and

effective pursuit of one's civil rights,

see Pt. IV, infra. Of course, courts

always retain the power to disallow an

expert expense, or any other, if it is

not "reasonable."

49

677, 696-97 (1979).

IV. TO EXCLUDE EXPERT WITNESS FEES FROM

THE PURVIEW OF SECTION 1988 WOULD

SUBVERT THE VERY PURPOSE OF THE ACT

BY MAKING IT EFFECTIVELY IMPOSSIBLE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS PLAINTIFFS TO BRING

MERITORIOUS CLAIMS THAT INVOLVED

COMPLEX OR TECHNICAL MATTERS,

CONTRARY TO CONGRESS• INTENT______

The real issue in this case is what

Congress intended, in the civil rights fee

acts. Thus, whatever standards apply

under F.R.C.P. 54(d), §§ 1920 and 1821—

including prior approval by the trial

judge or findings that the expert

testimony was "necessary or helpful . . .

or indispensable," see Copper Liquor,

Inc., v. Adolph Corrs, Co.. 684 F.2d

1087, 1100 (5th Cir. 1982) — they relate

not at all to the standards and policies

that control decision under § 1988 and

Title VII. Congress was concerned with

encouraging good faith civil rights

litigants to bring suit. Congress was

concerned with equalizing the legal

50

resources available to the parties.

Accordingly, it both adopted the prior

case law including expert witness fees as

recompensable expenses and imposed a

stringent standard before these expensive

items could be shifted to the

unsuccessful plaintiff.

Congress was clear about its purpose

in passing the Act: It was "designed to

give such persons effective access to the

judicial process.. . ." H. Rep. No. 94-1558

at 1; Legis. History 209. As stated by

Senator Kennedy: "Congress clearly

intends to facilitate and to encourage

the bringing of actions to enforce the

protections of the civil rights laws."

Legis. History 197. An important

consideration was to provide "fees which

are adequate to attract competent

counsel. . . ." S . Rep. No. 94-1011 at 6,

Legis. History 12; H. Rep. No. 94-1558 at

51

9; Legis. History 217. The bill's

sponsor echoed the testimony given in the

House, cited supra. at 22, n. 6:

When Congress calls upon

citizens — either explicitly or by

construction of its statutes — to

go to court to vindicate its

policies and benefit the entire

Nation, Congress must also insure

that they have the means to go to

court, and to be effective once they

get there. ... We cannot hope for

vigorous enforcement ofour civil

rights laws unless we, in the words

of the Knight [v. Auciello] court,

"remove the burden from the

shoulders of the plaintiff seeking

to vindicate the public right." That

is what this bill does, and why it

is so vital.

Legis. History 200 (Remarks of Senator

Tunney).

If expert witness fees had not been

included in the fee shifting scheme of

the Act, it would have failed in its

fundamental purpose to encourage and make

effective civil rights litigation.

W i th out the protection of the

Christiansburg standard, good faith

52

plaintiffs would be deterred by the

spectre of having to shoulder their

opponents' often large expert witness

fees. On the affirmative side, civil

rights plaintiffs would be deterred

because they could not hope to finance

the successful presentation of their

cases. This would hardly "facilitate and

encourage the bringing of actions,"

particularly in the "typical case," where

plaintiffs are indigent and "there is no

damage claim from which" to subsidize

costs. Legis. History 3 (Remarks of

Senator Tunney in introducing the bill).

As one witness admonished the House

subcommittee, costs "such as expert

witness fees and travel expenses", must

be included lest

the very point of the bills ... be

defeated for cases in which typical

though nontaxabale litigation costs

are likely to be heavy, and the

plaintiff has no prospect of

financing them absent a reasonable

53

hope of recovering them from the

defendant.

House Hearings, supra. at 136 (Statement

of John M. Ferren).

It might be that, if expert

witness fees were not recoverable, the

necessary experts simply would not be

hired. But this would defeat the

congressional purpose to provide for

effective access to the courts. This was

the very point of the witnesses who

testified before Congress about the

necessity of providing for the recovery

of expert witness fees. See supra, Pt.

II. In echoing their concern for

providing for effective access, Congress

should not be presumed to have discarded

the substance of that concern.

Finally, there exists a third

possible result of not including expert

witness fees: that these items of

expense would be borne by the attorneys

54

themselves. But this could not be what

Congress intended, for Congress knew that

attorneys had been unable to litigate

meritorious issues because of their

inability to meet these expenses. See

Statement of Dennis Flannery discussed,

supra. at 19 - 20. Moreover, to expect

attorneys to pay these often significant

expenses out of the fees awarded would

interfere with another of Congress's

specific objectives: to provide fees

sufficiently high to motivate capable

counsel to accept civil rights cases.25

25private attorneys would face two

problems. First. the expenses could

equal or even exceed any attorney's fee

that might be awarded. Indeed, most

practitioners would probably prefer not

being paid for their time rather than not

being reimbursed for out-of-pocket

expenses. Second. the advancing of costs

without any obligation on the part of the

clients to reimburse, would run afoul of

ethical rules against maintenance of

litigation. See ABA Code of Professional

Responsibility, DR 5-103(B). Although

the application of such rules to civil

rights cases is of doubtful legality (see

55

Congress was aware that civil rights

lawyers were not receiving copious awards

under the other fee provisions.* 26 These

NAACP V. Button. 371 U.S. 415, 420

(1963)), the very real threat of a

disciplinary proceeding (see, e.g., In re

Primus. 436 U.S. 412 (1978)) would be a

strong deterrent.

26 As observed by Senator Kennedy

during the debates:

The Senator from Alabama cannot

name one lawyer in this country who

has become wealthy because of his

work on the protection of the civil

rights of this Nation. I ask him to

name one — and his silence in this

particular situation, I think,

responds full well.

We are not talking about the

kinds of attorneys' fees that were

included in the antitrust bill. You

do not get rich from protecting the

civil rights of citizens whether

they are in my own city of Boston or

in Birmingham.

Legis. History 92. Senator Tunney

amplified on this point:

In fact, a 1975 study undertaken by

Leslie Helfman of the Antioch Law

School indicates that of the 140

most recent cases decided prior to

Alyeska, civil rights cases ranked

near the bottom with fees averaging

56

fees are intended to parallel market

rates in an effort to attract counsel.

Blum v. Stenson. 465 U.S. 886 (1984). If

they were discounted by the cost of

expert witnesses, they would no longer be

competitive with fees available in

commercial and other non-civil rights

litigation.

It is important to recognize, as did

Congress when it passed the Act, that

even with fee shifting the economics of

civil rights cases are substantially

different than most other areas of

practice. Ordinarily, there are no large

damage awards from which the client can

cover litigation expenses such as expert

witness fees. See city of Riverside v.

Rivera. 477 U.S. _____ , 91 L. Ed. 466

$37 per hour compared to $181 per

hour for the highest ranking field

of antitrust law.

Id. at 138.

57

(198 6) . Many civil rights cases seek

injunctive relief only. Sen. Rep. at 6.

Legis. History 12. This is in sharp

contrast to cases taken for a contingent

fee. In personal injury cases and most

treble damage antitrust cases, the damage

awards are often large enough for the

attorney to pay for large expense items

such as experts and still retain a

reasonable fee. See Legis. History 200-

201 (Remarks of Senator Kennedy). In

ordinary commercial cases the fee is

based on an hourly rate and the client is

billed for expenses such as expert

witness fees.

The significance of the expert

witness fee issue to the purposes of the

Act cannot he overstated: This case will

have a significant impact on the entire

range of civil rights litigation. And as

the decisions of this Court and of the

58

lower courts demonstrate, civil rights

cases often involve complex issues of law

and fact.27 For example, an issue of

discrimination in jury selection or some

other area might require a statistical

expert. See Castaneda v. Partida. 430

U.S. 482 (1977) and Vasouez v. Hillerv.

474 U.S. ___, 88 L.Ed.2d 598, 606 (1986).

Voting rights cases require an array of

expert testimony covering a variety of

matters. Thornburg v. Gingles. 478 U.S.

__, 92 L.Ed. 2d 25, 48 (1986) ("The

investigation conducted by the District

27 As this Court has noted, the

civil rights statutes and the amendments

on which they are based ■"prohibit

sophisticated as well as simple-minded

modes of discrimination." Lane v .

Walker. 307 U.S. 268, 175 (1969) . Cases

often require sophisticated proof for

" [ i ] n an age when it is unfashionable

. . . to openly express racial hostility,

direct evidence of overt bigotry will be

impossible to find." United States v.

Bd. of School Corom'rs. 573 F.2d 400, 412

(7th Cir.) , cert, denied. 439 U.S. 824

(1978) .

59

Court into the question of racial bloc

voting ... relied principally on

statistical evidence presented by

[plaintiffs'] expert witnessess ....").

And indeed, such testimony is essential

to prove the necessary elements of a vote

dilution case. Id. at 45-46. School

cases often require expert testimony.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Ed. . 402 U.S. 1, 9-10 (1971) ; Bradley.

supra. 53 F.R.D. at 44 ("It is difficult

to imagine a more necessary item of

proof...."). A Title VI case challenging

race discrimination in a hospital system

that receives federal funds could not be

presented effectively without calling a

specialist in health planning. See Brvan

v . Koch. 627 F. 2d 612, 617-618 (2d Cir.

1980). A prisoner could not establish

d e l i b e r a t e indifference in the

maintenance of an inadequate health care

60

system without being able to present

testimony of doctors and medical care

delivery specialists. See Estelle v.

Gamble. 429 U.S. 97 (1976) ; Newman v .

Alabama. 503 F. 2d 1320 (5th Cir. 1974).

Expert witness testimony may be crucial

to establish that the conduct of police

officers deviates from accepted norms.

Tennessee v. Garner. 471 U.S. ___, 85

L.Ed.2d 1, 14 (1985).

Cases under Title VII indicate the

importance of expert testimony to the

workings of that Act. It would be

difficult for most plaintiffs to

challenge a discriminatory employment

test under Albemarle Paper Co. v, Moodv.

422 U.S. 405 (1975) , without the aid of