Sulton v. Schoen Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sulton v. Schoen Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1968. 47c35d5a-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10f0321a-5d36-4f04-ad47-fe0a3ab7b476/sulton-v-schoen-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

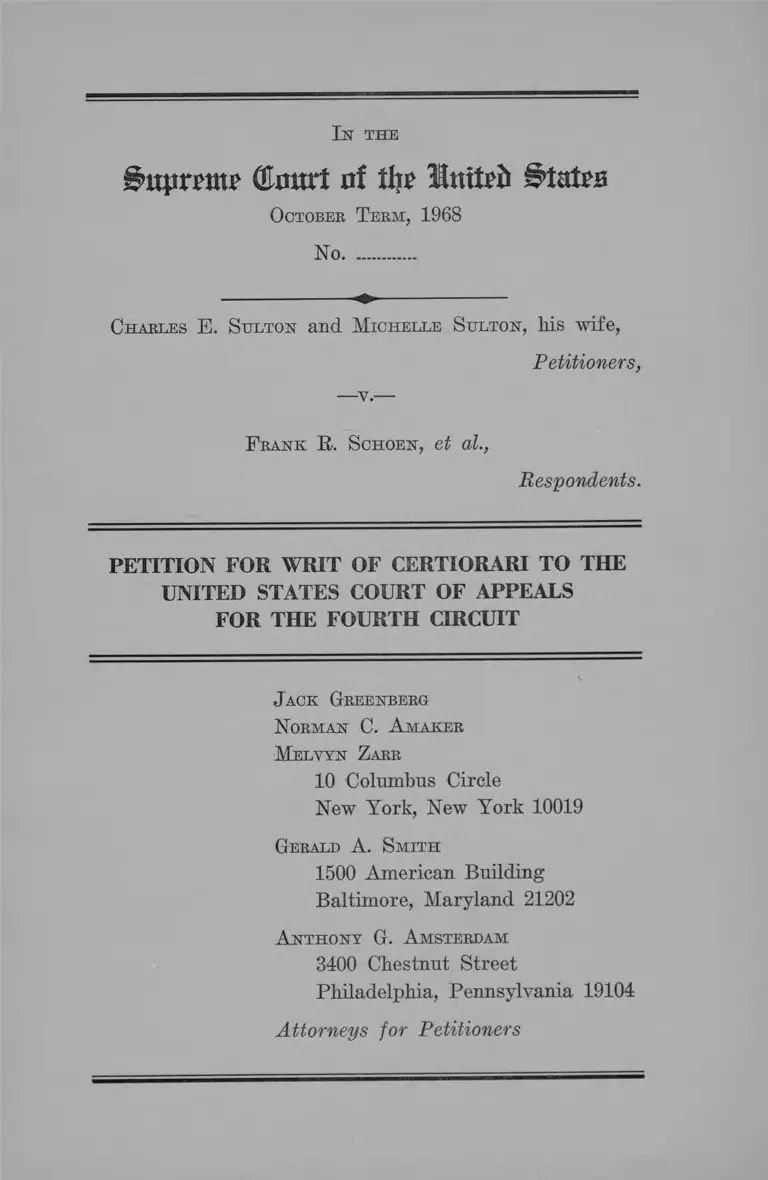

kapron? (Court of tlir $ttttr& States

October T erm, 1968

No.............

I n the

Charles E. Sulton and M ichelle Stjlton, his wife,

Petitioners,

-v.—

F rank ft. Schoen, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Jack Greenberg

Norman C. A maker

Melvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Gerald A. Smith

1500 American Building

Baltimore, Maryland 21202

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below .................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........— ....... .................- ............................... 2

Question Presented .......................................................... 2

Statutes Involved ................. ........................-.................. 2

Statement of the Case .................................................. 3

R easons eor Granting the W rit

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Correct the Court

of Appeals’ Restrictive Construction of Civil

Rights Removal Jurisdiction, Which Cripples the

Protection Due Civil Rights and Conflicts With

Decisions of This Court and the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit ................................................ 6

Conclusion...........................................................................—- I I

T able oe Cases

Achtenberg v. Mississippi, 393 F. 2d 468 (5th Cir. 1968) 9

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) ............. .....6,7,9

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966) .................. 6

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ............. ....... 10

u

PAGE

New York v. Davis, Second Circuit, No. 32989, decided

March 28, 1969 .............................................................. 6, 8

Walker v. Georgia, 381 U. S. 355 (1965) ............ 8

Walker v. Georgia, 5th Cir., Nos. 26271 and 26332 ..... 8

Walker v. Georgia, 405 F. 2d 1191 (5th Cir. 1969) ....9,10

Wilson v. Republic Iron and Steel Co., 257 U. S. 92

(1921) ................................................_..................... ...... 10

Wyche v. Louisiana, 394 P. 2d 927 (5th Cir. 1967) .... 9

Statutes I nvolved

28 U. S. C. §1254(1) .................................................... 2

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) .................................................. 2,3,9

42 U. S. C. §3617 .......................... ............................ 3,5,7

I n the

# upn w Qlmtrt nf tl?e Ittiteii States

October Term, 1968

No.............

Charles E. Sulton and Michelle Sulton, his wife,

Petitioners,

—v.—

P rank R. Schoen, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit entered May 9, 1969.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit affirming the district court’s order of

remand is unreported and is set forth in the Appendix,

p. la, infra.

The opinion of the United States District Court for the

District of Maryland is unreported and is set forth in the

Appendix, p. 3a, infra.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit was entered May 9, 1969.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1254(1) to review the Court of Appeals’ affirm

ance of the district court’s order remanding respondents’

civil action against petitioners to the state court from

which it was removed pursuant to the federal civil rights

removal statute, 28 U. S. C. §1443(1).

Question Presented

Are the Court of Appeals’ restrictions on civil rights

removal jurisdiction consistent with decisions of this Court

and the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit?

Statutes Involved

This case involves the operation of 28 U. S. C. §1443(1)

as it pertains to the protection afforded rights conferred

by 42 U. S. C. §3617.

1. 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) provides:

§1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prose

cutions, commenced in a State Court may be removed

by the defendant to the district court of the United

States for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

3

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot en

force in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof; . . .

2. 42 U. S. C. §3617 (enacted as §817 of the Fair Hous

ing Act of 1968) provides:

§3617. Interference, coercion, or intimidation; en

forcement of civil action.

It shall be unlawful to coerce, intimidate, threaten,

or interfere with any person in the exercise or enjoy

ment of, or on account of his having exercised or en

joyed, or on account of his having aided or encouraged

any other person in the exercise or enjoyment of, any

right granted or protected by section 3603, 3604, 3605,

or 3606 of this title. This section may be enforced by

appropriate civil action. [Pub. L. 90-284, Title VIII,

§817, Apr. 11, 1968. 82 Stat. 89.]

Statement of the Case

Petitioner Charles E. Sulton, a Negro, lives with his

wife Michelle, who is white, in a home in an otherwise

all-white subdivision known as Captain’s Cove in Oxon

Hill, Prince George’s County, Maryland (R. 6).

On September 13, 1968, their immediate neighbors, re

spondents herein, claiming that the Sultons were a nui

sance, brought suit against them in the Circuit Court of

Prince George’s County, seeking $300,000.00 in damages

and injunctive relief. In support of their claim for dam

ages, respondents alleged that, since the Sultons had

4

moved into the neighborhood, they had caused or permitted

“loud and offensive sounds, including threats, name call

ing, insults and cursing . . . telephone calls, gesturing and

untrue accusations to the police, as well as by shining

lights into the plaintiffs’ windows . . . ” (R. 17).

In support of their claim for injunctive relief, respon

dents, suing on their own behalf and on behalf of other

white neighbors, alleged that, since the Sultons had moved

into the neighborhood, they had engaged in “name calling,

insulting, cursing, gesturing, assaulting, making untrue

accusations against the neighbors to the police, the build

ing inspector, the electrical inspector, the FBI, the Senate

of the United States, the House of Representatives of the

United States and the Defense Department of the United

States, and shining lights during the night into their win

dows” (R. 20).

The Sultons removed the case to the United States Dis

trict Court for the District of Maryland pursuant to 28

U. S. C. $1443(1), the federal civil rights removal statute,

claiming that the suit was completely baseless and yet

another stratagem in the neighbors’ persistent campaign

to force them—because of Mr. Sulton’s race—from the

white neighborhood (R. 8-9). Included in this campaign

have been the direction of shotgun fire, cherry bombs and

other explosive devices at the Sultons’ home; the destruc

tion of a wire fence separating their home from the home

of respondents Wood; the staining of the Sultons’ canvas

awnings by the placing of wild berries thereon; the utter

ing of racial epithets at the Sultons; the making of mali

cious charges of the Sultons’ misconduct to the police and

other officials of Prince George’s County; and the making

of false and malicious reports of misconduct to the United

5

States Department of Defense, where Mr. Sulton is em

ployed, and to the Immigration and Naturalization Service

(Mrs. Sulton is a naturalized citizen) (E. 6-7).

The Sultons claimed that this campaign of harassment

to force them from the white neighborhood deprived them

of rights under §817 of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, set1

forth, p. 3, supra, which protects from interference, coer

cion, or intimidation the quiet enjoyment of housing covered

by the Act.

The district court refused to afford petitioners an evi

dentiary hearing to prove their claims and disallowed re

moval on the pleadings, holding (E. 109; App. p. 11a,

infra) :

No federal law permits a man to disturb and harass

his neighbors and no federal law prohibits a neigh

bor from suing a neighbor to enjoin a possible nui

sance. Yet, if the Sulton claim is true, if his neigh

bors are attempting to harass and deprive him of

his right to own and enjoy his home in that community

because of his race or his interracial marriage, then a

grave injustice is being done to him. But Sulton has

made no allegation, nor do I think he can in good

faith make an allegation, that the judges and/or

other officials of the State of Maryland, particularly

of Prince George’s County, have exhibited conduct

which could possibly be construed as evidence that his

federal civil rights will inevitably be denied by them.

The district court granted a stay of its remand order

pending appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit. That court, on May 9, 1969, vacated the stay and

summarily affirmed the district court’s judgment on the

6

district court’s opinion and the opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York v. Davis,

Second Circuit, No. 32989, decided March 28, 1969, petition

for writ of certiorari filed April 28, 1969, No. 2006 Misc.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE W RIT

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Correct the Court of

Appeals’ Restrictive Construction of Civil Rights Re

moval Jurisdiction, Which Cripples the Protection Due

Civil Rights and Conflicts With Decisions of This Court

and the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

The district court refused petitioners an evidentiary

hearing to prove their case for removal for two reasons:

1. Petitioners made no allegation that the Maryland

courts would refuse to fairly entertain their federal claims;

and, 2

2. “ No federal law permits a man to disturb and harass

his neighbors” (R. 109; App. p. 11a, infra).

The first ground of decision is plainly inconsistent with

this Court’s decisions in Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780

(1966) and Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966).

Petitioners made no such allegation because this Court

has squarely held that §1443(1) “does not require and

does not permit the judges of the federal courts to put

their brethren of the state judiciary on trial” (Peacock,

supra, 384 U. S. at 828). In Rachel, supra, this Court

allowed removal quite without regard to the fairness of

the judges and/or other officials of the State of Georgia

or the possibility that the removal petitioners there

7

“might eventually prevail in the state court” (384 U. S.

at 805).

Rather, this Court held in Rachel that civil rights re

moval jurisdiction is available in the service of rights

granted by a law providing for equal civil rights when

ever these rights are denied by the mere pendency of a

state criminal prosecution.1

The second ground of the district court’s decision is

more troublesome because of its cryptic brevity.

Petitioners did not claim in the district court, nor do

they claim here, a federal right to disturb and harass their

neighbors. Quite the contrary. Petitioners claimed that

the suit against them was completely baseless and yet

another device in the white neighbors’ campaign to resegre

gate the neighborhood, in violation of the Sultons’ rights

under the Fair Housing Act of 1968.2

Indeed, the district court conceded that if the Sultons’

version of the facts were true, a “grave injustice” was

being done them. Nonetheless, the district court refused

petitioners an evidentiary hearing to prove their version

of the facts.

Although the district court did not elaborate its reason

ing, the Court of Appeals apparently based its affirmance 1 2

1 The courts below assumed for purposes of decision that §817 is

a law providing for equal civil rights which immunizes from state

prosecution the quiet enjoyment of fair housing rights. Briefing

of this issue can await plenary consideration.

2 This assumes, of course, that the housing in question is covered

by §§803-06 of the Pair Housing Act. The courts below so assumed,

and this Court should, as it did in Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780,

805, n. 31 (1966), direct the district court, on remand, to determine

coverage.

8

on the reasoning of New York v. Davis, supra, decided

after the district court’s decision and now pending on writ

of certiorari in this Court, No. 2006 Misc.

In Davis, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

held that civil rights removal jurisdiction is limited to

cases in which the state proceeding openly and specifically

attacks conduct protected by a federal law providing for

equal civil rights. Thus, the Second Circuit read Rachel

as sustaining removal because the state prosecution of

Rachel for trespass openly and specifically attacked the

mere presence of Negroes in an establishment covered by

Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Under the Davis

analysis endorsed below, if Rachel had been charged with,

say, creating a nuisance in the restaurant by using loud

and offensive language, then this Court would have dis

allowed removal, while refusing him an evidentiary hear

ing to prove that the state charges were a baseless ploy

designed to harass him for the purpose of denying him

his rights to equal public accommodations.

Petitioners urge that certiorari be granted to correct this

misreading of Rachel, which offers a plain and easy path

to evasion of the protection due civil rights.3

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has con

sistently blocked this path to evasion, and its decisions are

in direct conflict with the decision below. Most recently,

3 This danger of evasion is not merely speculative. Mardon R.

Walker, who sought nondiscriminatory treatment in the place of

public accommodation involved in Rachel and whose trespass con

viction was reversed by this Court in Walker v. Georgia, 381 U. S.

355 (1965), was reindicted after this reversal on the same facts for

a crime other than trespass (malicious mischief). She removed her

prosecution to the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Georgia, which afforded her an evidentiary hearing but

disallowed removal. See Walker v. Georgia, Fifth Circuit, Nos.

26271 and 26332, appeals pending.

9

in Walker v. Georgia, 405 F. 2d 1191 (5th Cir. 1969), the

removal petitioner, a Negro, was charged with assault

against some white persons outside a restaurant. He al

leged in his removal petition that the charge was false and

simply fabricated by those persons to keep the restaurant

segregated. The district court refused to resolve the fac

tual dispute, and the Court of Appeals held this to he

error, in language particularly pertinent here (405 F. 2d

at 1192):

The [district] court stated that it was expressing

no opinion one way or the other as to what actually

happened when appellant sought service at the res

taurant and during the altercation which followed.

Rather, we perceive that the Court heard evidence

only to the point of determining whether the state was

in good faith contending that Walker committed acts

which were not immune from state prosecution. The

Court went on to hold that the conduct charged, mainly

assault, was not so immune. This, the Court could not

do, without resolving the facts surrounding the alter

cation with respect to assault vel non . . . We reiterate

what we said in Wyche [v. Louisiana, 394 F. 2d 927

(5th Cir. 1967)],4 i.e., that it is not the state charge

4 In Wyche, the removal petitioner was charged with aggravated

burglary and he removed, claiming that the charge was motivated

by an attempt to prevent his enjoyment of a truck stop covered

by Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The Court of Appeals

reversed the district court’s refusal to afford the removal petitioner

an evidentiary hearing. See also Achtenberg v. Mississippi, 393

F. 2d 468 (5th Cir. 1968) (vagrancy prosecution held removable).

No different rule applies to civii cases. Section 1443 does not

distinguish between “ civil actions or criminal prosecutions.” Nor

could it reasonably do so : a different result could not have been

reached in Rachel if the restaurateur had brought a civil suit

against Rachel seeking to restrain him on grounds of race from

“ trespassing” in the restaurant.

10

which controls; rather, what appellant was actually

doing with respect to the exercise of his federally pro

tected rights. (Emphasis added.)

Not only does the decision below offer those who would

deny federal civil rights an easy device to defeat the fed

eral jurisdiction enacted to protect these rights, but it is

inconsistent with accepted practice in the federal courts

in dealing with removal petitions, whether in civil rights

cases or others. That practice does not leave the federal

courts powerless to inquire, by the taking of evidence if

necessary, into the true nature and circumstances of the

cause sought to be removed, whatever its paper coating

in the state courts. See Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1,

33-35 (1906) ; Wilson v. Republic Iron and Steel Go., 257

U. S. 92, 97-98 (1921).5 Under the Fourth Circuit’s read

ing of Rachel, the only way the protection of the civil

rights removal jurisdiction would be available to the Sul-

tons was if their neighbors had sued to evict them for

integrating the neighborhood. But there is no such cause

of action in Maryland, so, petitioners claim, the neighbors

employed what law was available to the same illicit end.

This is a serious and important claim, and petitioners

should have a chance to prove it.

5 Petitioners do not ignore language in Greenwood v. Peacock,

384 U. S. 808, 826-27 (1966), which seems to suggest that removal

may he defeated by the plaintiffs’ choice of cause of action. But,

in the context of the Court’s holding that the removal petitioners

there had not invoked a federal equal civil rights statute which

protected their conduct and entitled them to removal, this dictum

cannot be regarded as overturning the long-settled rule that, absent

an evidentiary hearing, the factual allegations of the removal peti

tion are to be taken as true. Kentucky v. Powers, supra.

11

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioners pray that the

writ of certiorari be granted.

Kespectfnlly submitted,

Jack Greenberg

Norman C. A maker

Melvyn Z arr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Gerald A. Smith

1500 American Building

Baltimore, Maryland 21202

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104

Attorneys for Petitioners

A P P E N D I X

APPENDIX

Opinion and Judgment of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

P oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 13,395

F rank R. Schoen, and D oeothy L. Schoen, his wife, and

E rnest M. W ood and Janice G. W ood, his wife, and

F eank R. Schoen, D oeothy L. Schoen, E rnest M.

W ood, Janice G. W ood, for themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Appellees,

versus

Charles E. Sitlton and M ichelle Stjlton, his wife,

❖

Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

District of Maryland, at Baltimore. Edward S. Northrop,

District Judge.

--------------- * ---------------

(Argued May 8, 1969 Decided May 9, 1969.)

--------- »•«---------

B e f o r e :

B oreman, W inter and Craven, Circuit Judges.

Melvyn Zare (Jack Greenberg, Norman C.

Amaker, Anthony G. Amsterdam and Gerald

A. Smith on brief), for Appellants, and

E lsbeth L. B othe and R onald A. W illoner,

for Appellees.

--------- *---------

2a

P ee Cueiam :

This is an appeal from an order of the District Court

for the District of Maryland remanding the case to the

Circuit Court of Prince George’s County, Maryland, from

which it had been removed to the court below on petition

of the appellants.

We affirm on the opinion of the district court, Frank R.

Schoen et al. v. Charles E. Sulton et al., Charles E. Sulton

et al. v. Frank R. Schoen et al., ------ F. Supp. ------ (D.

Md.), Civil Action No. 19922, March 14, 1969. See also

New York v. David Davis, opinion by Judge Friendly,------

F. 2d ------, 37 Law Week 2584 (2 Cir. March 28, 1969).

Affirmed.

3a

Opinion and Judgment of the United States District

Court for the District of Maryland

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or the D istrict of Maryland

No. 19922 Civil Action

F rank R. Schoen and Dorothy L. Schoen, his wife and

E rnest M. W ood and Janice G. W ood, Ms wife and

F rank R. Schoen, D orothy L. Schoen, E rnest M.

W ood, Janice G. W ood, for themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Charles E. Stilton and M ichelle Sulton, his wife.

Charles E. Sulton and M ichelle Sulton, his wife,

— v.—

F rank R. Schoen and D orothy L. Schoen, his wife and

E rnest M. W ood and Janice G. W ood, his wife, J ohn

Crowley and Roberta Crowley, his wife; Mrs. H arry

K een ; J oe K een ; L. H. Mattingly and K itty Mat

tingly, Ms wife; T homas O’L oughlin and L ibbie

O’L oughlin, his wife; F rederick F. P fluger and A udra

P fluger, his wife; R oland R obison and J oyce R obi

son, Ms wife; H oward R udnick and Eva R udnick, his

wife; R oger Shoch and A nn Shoch, M s wife; A. R.

W ren and Betty W ren, his wife and W illiam F. R obie

and K athleen R obie, M s wife.

Filed: March 14, 1969

4a

R onald W illoner, College Park, Maryland, and

E lsbeth L evy B othe, Baltimore, Mary

land, for plaintiffs and counter-defendants,

ScJioen and Wood.

Gerald A. Smith , Baltimore, Maryland, for de

fendants and counter-plaintiffs.

Northrop, District Judge:

This controversy began when the plaintiffs, who are

neighbors of the defendants, filed suit to enjoin a nuisance

in the Circuit Court of Prince George’s County.1 Defen

dants petitioned to remove the ease to this court pursuant

to 28 U. S. C. §1443(1). After removal to this court the

defendants answered and counterclaimed against the origi

nal plaintiff and other neighbors. The gist of this entan

glement is that Schoen and other neighbors who originally

joined in his complaint allege that Sulton and his wife,

an interracial couple, have caused incessant turmoil in

their neighborhood including arguing, bickering, and

assaulting various neighbors culminating in false accusa

tions to the local police, the FBI, and other agencies of

the government. Defendants allege in their counterclaim

and by way of defense that it is the plaintiffs and other

neighbors, motivated by racial prejudice to their marriage,

who have threatened and harassed them with firecrackers,

racial epithets, and other harassing action including false

accusations to the Department of Defense (where Sulton

works) and the United States Immigration and Naturali

zation Service (Mrs. Sulton, French by birth, is a natural

1 As can be seen by the statement of fact, and as represented by

counsel for both sides, this neighborhood conflict has been develop

ing for some time prior to the institution of suit.

5a

ized citizen). Schoen and the other original plaintiffs now

seek to challenge the propriety of removal of this case to

the federal court.

Removal was pursuant to the civil rights’ removal pro

visions of §1443(1) of Title 28 which read:

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prosecu

tions, commenced in a State court may be removed by

the defendant to the district court of the United States

for the district and division embracing the place

wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot en

force in the courts of such State a right under any

law providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of

the United States, or of all persons within the juris

diction thereof . . . .

It is the position of Schoen that this case can properly

be removed only if two qualifications are present: (1) the

cause of action instituted in the state court is one which

infringes upon civil rights specifically granted or protected

by a federal law, and (2) these rights will be denied or

cannot be enforced in the state courts. Defendant Sulton

and his wife would have us hold that the bringing of this

suit in the state court is in itself a denial of the civil

rights of the defendants. Sulton contends that this suit

has been brought or motivated by racial prejudice to

harass Sulton and his wife and, thus, the suit itself is in

violation of the defendants’ federal civil rights to own and

enjoy property and home as guaranteed by 42 U. S. C.

§1982 and 42 U. S. C. §3617 (§817 of the Fair Housing

6a

Act of 1968).2 Defendant also argues that this court must

hold an evidentiary hearing (which, as a practical matter,

would involve hearing the entire substantive case) to de

cide if the Schoen suit is motivated by racial prejudice.

According to the defendants, if this court so finds racial

motivation, it must halt or insure the cessation of further

state court proceedings against the Sultons. Counsel for

Sulton concedes that under the procedure he has outlined,

if the court determines the suit is not racially motivated,

then the case must be returned to the state court. In sup

port of his theory, defendant primarily relies upon two

cases, Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) and City of

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808 (1966).

Upon consideration of defendants’ theory and his au

thorities, the court emphatically agrees with the plaintiff

that the case must be remanded to the state courts. While

all citizens have a right to be free from vexatious litigation

and, assuming without deciding that plaintiffs have a right

under federal civil rights’ legislation to be free from legal

and other harassments in owning and enjoying their home,

the mere fact that one party believes that a suit has been

brought to vex him is not cause to remove that case to

federal court. To remove a case to federal court one must

have more than an infringement of a federally-protected

2 This section reads: Interference, Coercion, or Intimidation. It

shall be unlawful to coerce, intimidate, threaten, or interfere with

any person in the exercise or enjoyment of, or on account of Ms

having exercised or enjoyed, or on account of his having aided or

encouraged any other person in the exercise or enjoyment of, any

right granted or protected by section 3603 (803), 3604 (804), 3605

(805), or 3606 (806). This section may be enforced by appropriate

civil action.

7a

civil right; there must be showing that the state courts

will not fairly enforce that right, Baines v. City of Dan

ville, 357 F. 2d 756 (4th Cir. 1966); Maryland v. Brown,

—-—- F. Supp.------ (I). Md. 1968 [Criminal No. 28193 de

cided January 23, 1969]. See also House v. Dorsey, Misc.

No. 504 decided by the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit on November 22, 1968.2a

Here there has been no showing and no allegation that

the courts of Prince George’s County, Maryland, or any

other county3 are racially prejudiced as to the defendants

so as to deny their legitimate federal civil rights or any

other rights which they seek to enforce. If after hearing

the evidence in this case, the state court determines that

the Schoen suit has been brought to vex and harass de

fendants and is motivated by racial prejudice, it has full

judicial power to remedy that wrong. Indeed, whatever

decision the state court may reach in this matter, as a

local court it is in far better position to judge the injunc

tive needs, if any, of these people and to enforce any rem

edy it might choose to grant.

Rachel and Peacock, contrary to the defendants’ argu

ment, support the position this court has taken. In Rachel

the defendants alleged that they were indicted in a Georgia

state proceeding for criminal trespass resulting from their

peaceful efforts to obtain service at privately owned Ala

bama restaurants open to the general public, but not to

members of the Negro race, and that these arrests occurred

2a See also Naimaster v. NAACP, ------ F. Supp. ------ (D. Md.

1969), decided March 5, 1969, by C. J. Thomsen.

3 Upon written oath of either party this case may be removed

to another county in Maryland, Rule 542, Maryland Rules of Pro

cedure, Volume 9B of the Annotated Code of Maryland.

8a

solely in the context of racial discrimination. The Court

agreed that if the allegations were true, removal was war

ranted because

“ [T]he removal petition alleges, in effect, that the de

fendants refused to leave facilities of public accommo

dation, when ordered to do so solely for racial reasons,

and that they are charged under a Georgia trespass

statute that makes it a criminal offense to refuse to

obey such an order. The Civil Rights Act of 1964, how

ever, as Hamm v. City of Rock Hill, 379 U. S. 306

(1964), made clear, protects those who refuse to obey

such an order not only from conviction in the state

courts, but from prosecution in those courts. . . . Hence

if as alleged in the present removal petition, the de

fendants were asked to leave solely for racial reasons,

then the mere pendency of the prosecutions enables the

federal court to make the clear prediction that the

defendants will be ‘denied or cannot enforce in the

court of [the] State’ the right to he free of any ‘at

tempt to punish’ them for protected activity. . . . The

burden of having to defend the prosecutions is itself

the denial of a right explicitly conferred by the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 as construed in Hamm v. City of

Rock Hill, supra.” 384 H. S. at 804-5.

In Peacock, the defendants alleged that while engaged in

civil rights’ activities in Greenwood, Mississippi, they

were arrested and prosecuted for obstructing the public

streets. They claimed these arrests were solely caused by

state and city policies of racial discrimination. But the

Court speaking, as it did in Rachel, through Mr. Justice

Stewart denied removal and explained:

9a

“ In Rachel the defendant relied on the specific pro

visions of a pre-emptive federal civil rights law . . .

that under the conditions alleged, gave them (1) the

federal statutory right to remain on the property of

a restaurant proprietor after being ordered to leave,

despite a state law making it a criminal offense not to

leave, and (2) the further federal statutory right that

no State should even attempt to prosecute them for

their conduct. . . . The present case differs from

Rachel in two significant respects. First, no federal

law confers an absolute right on private citizens—on

civil rights advocates, on Negroes, or anybody else—

to obstruct a public street, to contribute to the delin

quency of a minor, to drive an automobile without a

license, or to bite a policeman. Second, no federal law

confers immunity from state prosecutions on such

charges.” 384 IT. S. at 826.

The Court went on to hold:

“ To sustain removal of these prosecutions to a

federal court upon the allegations of the petitions in

this case would therefore mark a complete departure

from the terms of the removal statute, which allow

removal only when a person is ‘denied or cannot en

force’ a specified federal right in the courts of [the]

State, and a complete departure as well from the con

sistent line of this Court’s decisions . . . . The civil

rights removal statute does not permit the judges of

the federal courts to put their brethren of the state

judiciary on trial. Under §1443(1), the vindication of

the defendant’s federal rights is left to the state courts

except in the rare situations where it can be clearly

10a

predicted by reason of the operation of a pervasive

and explicit state or federal law that those rights will

inevitably be denied by the very act of bringing the

defendant to trial in the state court.” 384 U. S. at

828-29. (Emphasis supplied.)

Thus, the clear teachings of Rachel and Peacock are

that the two requirements of §1443(1) must be met to

justify removal under the federal civil rights removal

statute. Those two requirements are (1) a right guaran

teed by federal law, which (2) is denied or cannot be en

forced in the State courts. In Rachel the Court held that

the two requirements would be met and removal would be

justified if the allegations were true because under a unique

federal statute not only was it a federal civil right to be

served in a place of public accommodation, but it was

also a federal civil right to be free from prosecution for

seeking to exercise that right. Thus, the indictment by

the state court in violation of the defendants’ right to be

free from prosecution was evidence or proof that the de

fendants would “be denied or cannot enforce” their federal

civil rights in the state courts.

In Peacock, which is more akin to the alleged situation

here, the Court found the two requirements were not met

because there was and is no federal right to obstruct a

public street, and there is certainly no federal right to

be free from arrest and prosecution under such charges.

As Mr. Justice Stewart noted, if it was true that the

arrests and prosecutions of the defendants were based on

racial prejudice, where an attempt to deprive the defen

dant of civil rights guaranteed by federal law, then a

grave injustice had been done, but the question then before

11a

the Court was limited to the removability of this case

under §1443(1). To that the Court’s answer was emphatic:

“Unless the words of this removal statute are to be dis-

garded and the previous consistent decisions of this

Court completely repudiated, the answer must clearly

be that no removal is authorized in this case.” 384

U. S. at 831.

The same is true here. No federal law permits a man

to disturb and harass his neighbors and no federal law

prohibits a neighbor from suing a neighbor to enjoin a

possible nuisance. Yet, if the Sulton claim is true, if his

neighbors are attempting to harass and deprive him of

his right to own and enjoy his home in that community

because of his race or his interracial marriage, then a

grave injustice is being done to him. But Sulton has made

no allegation, nor do I think he can in good faith make an

allegation, that the judges and/or other officials of the

state of Maryland, particularly of Prince George’s County,

have exhibited conduct which could possibly be construed

as evidence that his federal civil rights will inevitably

be denied by them.

In conclusion, the court notes that if the defendant’s

theory were accepted, federal court would have to hold,

at the very least, evidentiary hearings in every case

brought in the state court which the defendant alleged was

motivated by racial prejudice. Such a result, aside from

the immense administrative problems it would pose, would

sound the destruction of the independent state judiciary

system and would establish a federal judiciary that was

never intended by the Constitution or by Congress.

12a

Wherefore, in consideration of the matters set forth in

the above opinion, it is this fourteenth day of March, 1969,

Ordered that the plaintiffs’ motion to remand this case

to the Circuit Court of Prince George’s County, Maryland,

is hereby Granted.

E dward S. Northrop

United States District Judge

RECORD PRESS, INC., 95 MORTON ST., NEW YORK, N. Y. 10014, (212) 243-5775