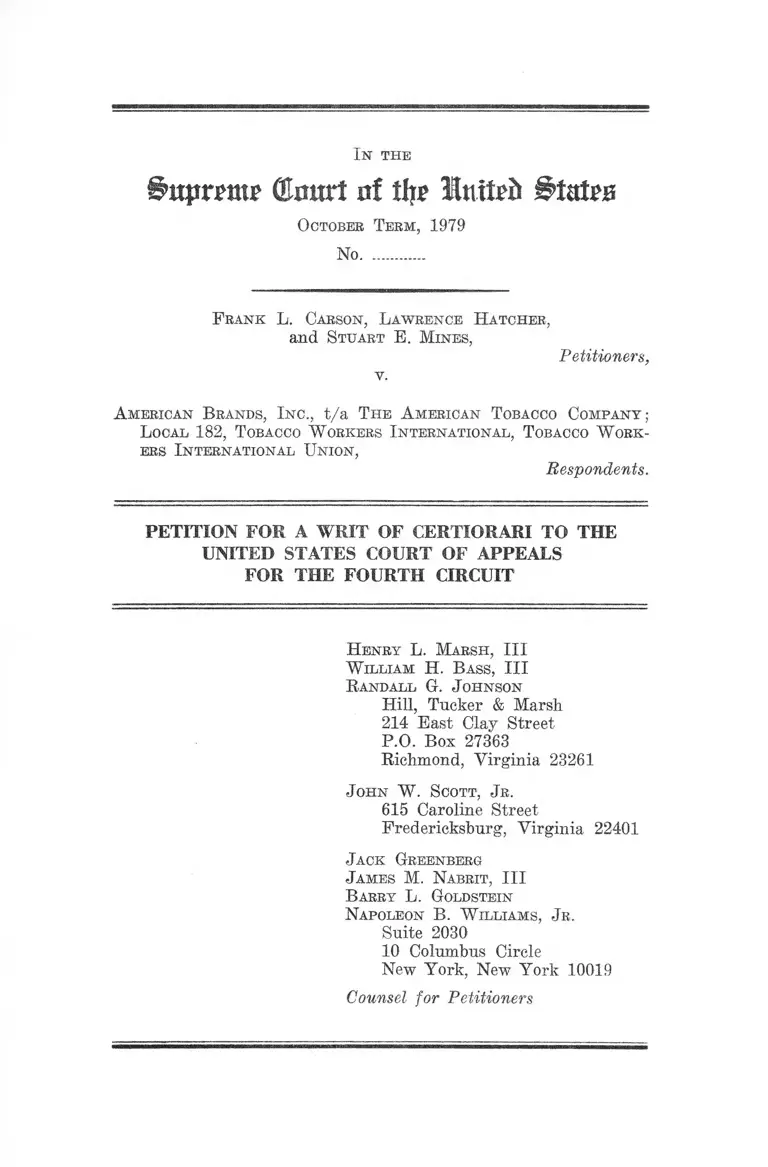

Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1979. 17d7caf4-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/10f3d57d-1554-4c5a-90c6-3e3c1fee5d7b/carson-v-american-brands-inc-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-united-states-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

In the

(Emtrt of tl|? United States

October Term, 1979

No................

F rank L. Carson, L awrence H atcher,

and Stuart B. Mines,

v.

Petitioners,

A merican B rands, Inc ., t /a The A merican Tobacco Com pany ;

L ocal 182, Tobacco W orkers I nternational, Tobacco W ork

ers I nternational Union,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

H enry L. Marsh, III

W illiam H. B ass, III

Randall G. J ohnson

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 Bast Clay Street

P.O. Box 27363

Richmond, Yirginia 23261

J ohn W . Scott, Jr .

615 Caroline Street

Fredericksburg, Yirginia 22401

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Barry L. Goldstein

Napoleon B. W illiams, Jr,

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Petitioners

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

CITATION TO OPINION BELOW.............. 2

JURISDICTION ...................................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED................................ 3

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ...................................................... 6

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................. 7

HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS WERE RAISED

BELOW ........................................................................... 15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT .............................. 16

I . THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER DENYING

THE PARTIES' JOINT MOTION IS APPEALABLE

AS A COLLATERAL ORDER UNDER

28 U.S.C. §1291 ................................................... 19

I I . THE DISTRICT COURT'S DISAPPROVAL OF

THE PROPOSED CONSENT DECREE IS

APPEALABLE AS AN INTERLOCUTORY

ORDER UNDER 28 U.S.C. §1292 ( a ) ( 1 ) ______ 24

I I I . RULE 23(e ) DOES NOT AUTHORIZE A

FEDERAL DISTRICT COURT TO DISAPPROVE

A SETTLEMENT MEETING THE REQUIREMENTS

OF WEBER ON THE GROUND THAT THE CLASS

MEMBERS ARE NOT NECESSARILY VICTIMS

OF DISCRIMINATION BY THE DEFENDANTS . . . 28

CONCLUSION .......................................................................... 33

APPEENDIX

Opinion o f the Court o f Appeals .............. la

Opinion o f the D i s t r i c t Court ................... 28a

Judgment o f the D i s t r i c t Court ................ 51a

Judgment o f the Court o f Appeals . . . . . . . 52a

- i -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

C ases :

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver C o . , 415 U.S.

36 (1974) .................................................................. 18,30

Baltimore Contractors v . Bodinger,

348 U.S. 176 (19 ) .......................... ................ 26

C a t l in v. United S ta tes , 324 U.S 229

(1945) ....................... 19

Cohen v. B e n e f i c i a l I n d u s tr ia l Loan

Corp. 377 U.S. 541 (1949) _______ 1 7 ,19 ,20 ,24

Cold Metal Process Co. v . United

Eng'r 4 Foundry C o . , 351 U.S.

445 (1956) .............................. 27

Cooper & Lybrand v. L ivesay , 437

U.S. 463 (1978) ................................................. 19,23

Eisen v. C a r l i s l e & J acqu e l in , 417

U.S 156 (1974) ................................................. .. . 19

F l inn v. FMC Corporat ion , 528 F.2d 1169

(4th C ir . 1975), c e r t , denied

424 U.S. 969 (1976) ____. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Franks v . Bowman Transporta t ion C o . ,

424 U.S. 747 (1978) ............................ 11,22

In re In te r n a t io n a l House o f Pancakes

Franchise L i t i g a t i o n , 487

F . 2d 303 (8th Cir . 1973) .......................... 16

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcast ing Co . ,

437 U.S 478 (1978) ..................................... 19, 25, 26

G i l l e s p i e v . U.S. Stee l Corp . , 379

U.S. 148 (1964) . . . . ....... ............... .................. 23

Page

li

Page

L iber ty Mutual Ins . Co. v . Wetzel ,

424 U.S 737 (1976) ............................................ 25

M ercant i le National Bank at Dal las

v . Langdeau, 371 U.S 555 (1963) .............. 23,24

Norman v. McKee, 431 F .2d 769 (9th

Cir. 1970) c e r t , denied , 401

U.S. 912 (1971) .............................................. 16

Patterson v. Newspaper & Mail Del . U. o f

N.Y. V i c . , 514 F .2d 767 (2d

Cir . 1975), c e r t , denied , 427 U.S.

911 (1976) .............. 31

Regents o f the U n ivers i ty o f C a l i f o r n i a

v . Bakke, 438 U.S 265 (1978) ............ 18,21

R usse l l v . American Tobacco Company,

528 F .2d 357 (4th C ir .

1975), c e r t , denied , 425 U.S.

935 (19757“ . .777777............................................. 13

Sears, Roebuck & Co. v . Mackey, 351 U.S.

427 (1956) ............................................. 27

Seiga l v. Merrick , 590 F.2d 35 (2d

C ir . 1978) ............................................................... 16, 17

Switzer land Cheese A s s o c i a t i o n , Inc .

v. E. Horne's Market, I n c . , 385

U.S. 23 (1966) ...................................................... 25,26

Teamsters v . United S ta tes , 431 U.S. 324

(1977) ........................................................................ 22,24

United Steelworkers o f America, AFL-CIO-

CLC v . Weber, U.S.

61 L .Ed. 2d 4 80 T 1979) 7TT.......... 7 ,1 7 ,1 8 ,2 0 ,

2 1 ,22 ,24 ,27 ,

28 ,30 ,32

- iii -

Constitutional Provisions

F i f t h Amendment to the C o n s t i t u t i o n

o f the United States ............................ .. 3,15

Statutes

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ................... ......................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1291 .......................... .. 3 ,6 ,8 ,1 6 ,

17,18, 19

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 2 (a ) (1 ) ....................... .. 3 , 6 , 8 , 1 6 ,

17 ,18 ,24 ,

25,26

42 U.S.C §1981 ...................................................... 6 ,7

T i t l e VII , C i v i l Rights Act o f 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et

s e q .......................................................... ~ 3 - 5 ,7 , 1 5 , 1 7 ,

18 ,2 2 ,2 4 ,2 7 ,

28, 30

Rules

Rule 2 3 ( e ) , Federa l Rules o f

C i v i l Procedure ................................ 6 , 7 , 1 3 ,1 5 ,

28

L e g i s l a t i v e History

Remarks o f Senator Hubert Hemphrey,

110 Cong. R e c . , 6548, concerning

T i t l e VII, C i v i l Rights Act o f

1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§§200Ge et s e q . . ............................ .................... 30

- iv -

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1979

No.

FRANK L. CARSON, LAWRENCE HATCHER,

and STUART E. MINES,

P e t i t i o n e r s ,

v .

AMERICAN BRANDS, INC. , T/A THE

AMERICAN TOBACCO COMPANY; LOCAL 182,

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL,

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Frank L. Carson, Lawrence Hatcher, and Stuart

E. Mines, p e t i t i o n f o r a wri t o f c e r t i o r a r i to

review the judgment o f the United States Court o f

Appeals f o r the Fourth C i r c u i t , entered on Septem

ber 14, 1979, d i sm iss in g an appeal by p e t i t i o n e r s

from an o r d e r , e n t e r e d June 2, 1977, by the

2

U n ite d S t a t e s D i s t r i c t Court f o r the E a s t e r n

D i s t r i c t o f V i r g in ia , Richmond D iv i s i o n , denying a

j o i n t motion by the p a r t i e s to approve and enter a

consent decree .

CITATION TO OPINION BELOW

The o p i n i o n o f the Court o f A p p ea ls i s

r e p o r t e d at 606 F .2d 420 and i s s e t f o r t h in

th e A p p e n d ix . The o p i n i o n o f the D i s t r i c t

Court i s reported at 446 F.Supp. 790 and i s set

out in the Appendix.

JURISDICTION

The judgment o f the Court o f Appeals d i s m is

s i n g th e a p p ea l was e n t e r e d on September 14,

1979. See Appendix. Fol lowing th i s d is m is s a l ,

p e t i t i o n e r s f i l e d a motion with th is Court f o r an

exten s ion o f time in which to f i l e a p e t i t i o n f o r

a w r i t o f c e r t i o r a r i . On December 6, 1979, the

Court granted the motion and ordered the time f o r

p e t i t i o n e r s t o f i l e a wri t o f c e r t i o r a r i extended

u n t i l , and in c lu d in g , February 11, 1980.

J u r i s d i c t i o n o f t h i s Court is invoked pur

suant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(1 ) .

3

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case in vo lves the F i f t h Amendment to the

C o n s t i t u t i o n o f the United S tates ,

This case a lso in vo lves the f o l l o w in g fe d e r a l

s t a t u t e s :

a. 28 U.S.C, §1291

The c o u r t o f a p p e a ls s h a l l have

j u r i s d i c t i o n o f appeals from a l l f i n a l

d e c i s i o n s o f the d i s t r i c t cou r ts o f the

United S tates , the United States D is

t r i c t Court f o r the D i s t r i c t o f the

Canal Zone, the D i s t r i c t Court o f Guam,

and the D i s t r i c t Court o f the V i r g i n

I s lands , except where a d i r e c t review

may be had in the Supreme Court.

b . 28 U.S.C. §1292(a)

The c o u r t o f a p p e a l s s h a l l have

j u r i s d i c t i o n o f appeals from:

(1 ) I n t e r l o c u t o r y orders o f the

d i s t r i c t courts o f the United S tates ,

the United States D i s t r i c t Court f o r the

D i s t r i c t o f the Canal Zone, the D i s t r i c t

Court o f Guam, and the D i s t r i c t Court o f

the V i r g i n I s l a n d s , o r o f the ju d g e s

t h e r e o f , g rant ing , con t in u in g , modi fy

ing, r e fu s in g or d i s s o l v i n g in ju n c t i o n s ,

o r r e f u s i n g t o d i s s o l v e o r m o d i f y

i n j u n c t i o n s , e x c e p t where a d i r e c t

review may be had in the Supreme Court.

c . 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2

( a ) I t s h a l l be an u n l a w f u l

employment p r a c t i c e f o r an employer—

(1 ) t o f a i l or r e fu se to h i r e or

to d ischarge any i n d i v i d u a l , o r o t h e r

wise to d i s c r im in a te against any i n d i v i

dual with resp ec t t o h is compensation,

t e r m s , c o n d i t i o n s , o r p r i v i l e g e s o f

employment, because o f such i n d i v i d u a l ’ s

r a c e , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex , o r n a t io n a l

o r i g i n ; or

( 2 ) t o l i m i t , s e g r e g a t e , o r

c l a s s i f y h i s employees or a p p l i ca n ts f o r

e m p l o y m e n t i n any way w h i c h w o u l d

depr ive o r tend to depr ive any i n d i v i

dual o f employment o p p o r t u n i t i e s o r

otherwise adverse ly a f f e c t h i s s tatus as

an e m p lo y e e , b e c a u s e o f such i n d i v i

d u a l ' s ra ce , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex , or

n a t ion a l o r i g i n .

( c ) It s h a l l be an unlawful employment

p r a c t i c e f o r a l a b o r o r g a n i z a t i o n - -

( 1 ) t o e x c l u d e o r t o e x p e l

from i t s membership, or otherwise

t o d i s c r i m i n a t e a g a i n s t , any

i n d i v i d u a l b e c a u s e o f h i s r a c e ,

c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex , o r na t ion a l

o r i g i n ;

(2 ) t o l i m i t , segregate , or

c l a s s i f y i t s membership or a p p l i

cants f o r membership, or to c l a s

s i f y or f a i l or re fu se to r e f e r f o r

employment any in d i v i d u a l , in any

way which would depr ive or tend to

depr ive any in d iv id u a l o f employ

ment o p p o r t u n i t i e s , or would l i m i t

s u c h e m p l o y m e n t o p p o r t u n i t i e s

- 5 -

or otherwise adverse ly a f f e c t h i s

s t a t u s as an em ployee o r as an

a p p l i ca n t f o r employment, because

o f such i n d i v i d u a l ' s ra ce , c o l o r ,

r e l i g i o n , sex , or n a t io n a l o r i g i n ;

or

( 3 ) t o c a u s e or a t tem p t to

cause an employer to d i s c r im in a te

aga inst an in d iv id u a l in v i o l a t i o n

o f t h i s s e c t i o n .

( j ) N o th in g c o n t a i n e d in t h i s s u b

chapter s h a l l be in te rp r e te d to requ ire

any employer, employment agency, labor

o r g a n iz a t i o n , or j o i n t labor-management

committee s u b je c t t o th i s subchapter to

g r a n t p r e f e r e n t i a l t r e a t m e n t to any

in d iv id u a l or to any group because o f

th e r a c e , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , s e x , or

n a t ion a l o r i g i n o f such in d iv id u a l or

group on account o f an imbalance which

may e x i s t w i th r e s p e c t t o the t o t a l

number or percentage o f persons o f any

r a c e , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex , or n a t ion a l

o r i g i n e m p l o y e d by any e m p l o y e r ,

r e f e r r e d or c l a s s i f i e d f o r employment by

any employment agency or labor o rg a n iza

t i o n , admitted to membership or c l a s

s i f i e d by any l a b o r o r g a n i z a t i o n ,

o r a d m i t t e d t o , o r employed i n , any

a p p ren t i cesh ip o r o ther t ra in in g pro

gram, in c o m p a r i s o n w i t h the t o t a l

number or percentage o f persons o f such

r a c e , c o l o r , r e l i g i o n , sex , or n a t ion a l

o r i g i n in any community, S tate , s e c t i o n ,

or o ther area, or in the a v a i la b l e work

f o r c e in any community, S tate , s e c t i o n ,

or o ther area.

d • Rule 2 3 ( e ) , Federal Rules o f C i v i l Pro

cedure “ “ ‘

A c l a s s act ion s h a l l not be d i s

m i s s e d o r c o m p r o m i s e d w i t h o u t t h e

approval o f the c o u r t , and n o t i c e o f the

p r o p o s e d d i s m i s s a l s h a l l be g i v e n t o

a l l members o f the c la s s in such manner

as the court d i r e c t s .

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the Court o f Appeals erred in

ho ld ing that p e t i t i o n e r s were not e n t i t l e d under

28 U.S.C. §§1291 and 1 29 2 (a ) (1 ) to appeal a d en ia l

by the d i s t r i c t c ou r t o f a j o i n t motion by the

p a r t i e s to approve and enter a proposed consent

d e c r e e e n j o i n i n g d e f e n d a n t s from e n g a g in g in

unlawful d i s c r im in a to r y a c t i o n s under T i t l e VII o f

the C i v i l R ig h t s A c t o f 1964, as amended, 42

U .S .C . § § 2 0 0 0 e , e t s e q . , and 42 U .S .C §1981?

2. Whether the f e d e r a l d i s t r i c t cou r t below

erred in ho ld ing that the due proc ess c lause o f

the F i f t h Amendment to the C o n s t i tu t i o n o f the

United States and T i t l e VII o f the C i v i l Rights

Act o f 1964, p r o h i b i t federa l courts from j u d i

c i a l l y approving , in the absence o f d i s c r im in a t i o n

by defendants against p l a i n t i f f s and other c la ss

members, proposed consent decrees prov id ing f o r

7

remedial use o f r a c e - c o n s c i o u s a f f i r m a t iv e a c t i o n

program in accordance with requirements set f o r th

in United Steelworkers o f America, AFL-CIO-CLC v.

W eber , ___ J J .S . ___61 L .Ed . 2d 480 ( 1 9 7 9 ) ?

3. Whether the d i s t r i c t cou r t below app l ied

proper c r i t e r i a , or otherwise abused i t s d i s c r e

t i o n , under Federal Rules o f C i v i l Procedure 23(e)

in r e f u s in g to approve a proposed sett lement by

the p a r t i e s o f a T i t l e VII c l a s s a c t i o n ?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

General . On October 24, 1975, p e t i t i o n e r s ,

p r e s e n t and fo r m e r s e a s o n a l em p lo y e e s a t the

Richmond Leaf Department o f the American Tobacco

Company, a su b s id ia ry o f American Brands, I n c . ,

which is l o c a te d in Richmond, V i r g in ia , f i l e d a

complaint on b e h a l f o f themselves and other black

employees at the Richmond Leaf Department. The

complaint charged that defendant American Brands,

I n c . , defendant Tobacco Workers' In te r n at io n a l

Union , and d e f e n d a n t L o c a l 182 o f the T o b a cc o

Workers' In te r n at io n a l Union, in v i o l a t i o n o f the

C i v i l Rights Act o f 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e, et

s e q . , and 42 U.S.C §1981, d i s c r i m i n a t o r i l y denied

b l a c k w o r k e r s h i r i n g , p r o m o t i o n , and t r a n s f e r

o p p o r t u n i t i e s and d i s c r i m i n a t o r i l y r e s t r i c t e d

_ 8 -

b l a c k w o r k e r s t o low p a y i n g and o t h e r w i s e un

d e s i r a b le j o b s .

A f t e r the conduct o f ex te n s iv e d i s c o v e r y , the

d i s t r i c t c o u r t , on March 1, 1977, c e r t i f i e d a

c l a s s c o n s i s t i n g o f (1 ) b lack persons, c u r r e n t ly

and former ly employed who were seasonal employees

o f the American Tobacco Company's Richmond Leaf

Department on or a f t e r September 9, 1972, and (2 )

b lack persons who app l ied f o r seasonal employment

at the American Tobacco Company's Richmond Leaf

Plant on or a f t e r September 9, 1972.

The p a r t i e s reached a sett lement o f p l a i n

t i f f s ' c la im s , entered in to a proposed consent

d e cr e e , and j o i n t l y moved f o r approval and entry

o f the proposed d ecr ee . The d i s t r i c t court denied

the motion on June 1, 1977.

On May 14, 1979, the United States Court o f

Appeals f o r the Fourth C i r c u i t ordered the merits

o f the a p p ea l t o be d e t e r m in e d en ban c . On

September 14, 1979, however, the Court o f Appeals

ordered the appeal dismissed on the ground that

the order appealed from below was not appealable

w i t h i n t h e in tendm ent o f 28 U .S .C . §§1291 and

1292. Chief judge Haynsworth and c i r c u i t judges

Winter and Butzner d is sen ted in an op in ion ho ld ing

that the order was appealab le and that the consent

decree should have been approved.

- 9 -

H istory o f Rac ia l D i s c r im in a t io n . American

Brands, I n c . , employs 150 seasonal employees and

100 r e g u la r , or f u l l - t i m e , employees to process

and s t o r e l e a f t o b a c c o at the Richmond L e a f

Department o f th e Am er ican T o b a c c o Company in

Richmond, V i r g in ia . The seasonal employees, a l l

o f whom are b l a c k , work b e tw een s i x and n in e

months d u r in g the y e a r . By c o n t r a s t , r e g u l a r

employees, o f whom 34% are white , work throughout

th e y e a r . — ̂ Both the s e a s o n a l and r e g u l a r em

ployees are represented by defendant Local 182,

Tobacco Workers ' In te r n a t io n a l Union ( h e r i n a f t e r

"T .W . I .U . " ) .

P r io r to September 16, 1963, union j u r i s d i c

t i o n o v e r j o b p o s i t i o n s at the Richmond L e a f

Department was d iv ided betweeen Local 182 o f the

T .W . I . U . and L o c a l 214 o f th e T .W . I .U . The

former, whose membership was then a l l white , had

e x c l u s i v e j u r i s d i c t i o n over regu lar job c l a s s

i f i c a t i o n s . Loca l 214 's membership was l im ited

1/ The f o l l o w in g t a b le represents the r a c i a l

c o m p o s i t i o n o f the em p lo y e e s at the Richmond

Leaf Department from 1968-1976:

Year Regular Employeed Seasonal Employees

Whites Blacks Whites Blacks

1968 41 52 0 116

1970 40 59 0 175

1973 40 56 0 176

1976 37 57 0 135

10

to b lack employees who were seasonal workers at

the Richmond Leaf Department,

While the e x i s t e n c e o f two separate unions at

the Department was o f f i c i a l l y t e r m in a t e d on

September 16, 1963, the p r e - e x i s t i n g patterns o f

r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n , h o w e v e r , c o n t i n u e d in

e f f e c t at the Richmond Leaf Department as a con se

quence o f r e g u la t i o n s and procedures e s t a b l i s h i n g

the system o f s e n i o r i t y and t r a n s fe r r i g h t s o f

employees .

S e n i o r i t y and T r a n s f e r R i g h t s . P r i o r t o

September 16, 1963, permanent job vacanc ies were

f i l l e d by c a n v a s s i n g th e e m p loy ees w i t h i n the

barga in ing un it o f the union having j u r i s d i c t i o n

o f the j o b s in which t h e v a c a n c i e s e x i s t e d .

This procedure b e n e f i t t e d the white members o f

Local 182 in the com pet i t ion f o r permanent jo b

p o s i t i o n s .

F o l l o w i n g the 1963 m erger o f the L o c a l s ,

the ru les governing the f i l l i n g o f vacancies in

the f u l l - t i m e p o s i t i o n s continued to exc lude or

d i s a d v a n t a g e the b l a c k w orkers who had been

d i s c r i m i n a t o r i l y ass igned to seasonal p o s i t i o n s .

When management r e q u e s t s a j o b t r a n s f e r o f a

r e g u l a r em ployee t h a t em p lo y e e d o e s not l o s e

s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s , but when management requests a

seasonal employee to t r a n s fe r to f u l l - t i m e work

11

that employee l o s e s h is s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s . More

over , when a regu lar worker t ra n s fe r s from one

f u l l - t i m e jo b to another one the employee re t a in s

a l l o f h i s s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s , but when a seasonal

worker t r a n s fe r s to a f u l l - t i m e jo b he lo ses a l l

2/

o f h i s s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s . — Furthermore, a seasonal

w o r k e r who t r a n s f e r s t o a f u l l - t i m e p o s i t i o n

almost always must enter at a b o t t o m - l e v e l p o s i

t i o n because the regu lar workers have the f i r s t

opportu n ity to move to the vacanc ies in f u l l - t i m e

p o s i t i o n s ; a c c o r d in g ly , i f a seasonal worker i s

employed in a seasonal p o s i t i o n above the e n t r y -

l e v e l , he f r equent ly w i l l be required to s u f f e r a

sh ort - te rm pay cut in order to move in t o a f u l l

time p o s i t i o n . The im pos i t ion o f these p e n a l t i e s ,

the l o s s o f s e n i o r i t y and the p o s s i b l e red u c t ion

in sh ort - te rm pay, serve to lock in the e f f e c t s o f

the h i s t o r i c a l d i s c r i m i n a t o r y p r a c t i c e s which

e x i s t e d a t the Richmond L e a f D i v i s i o n . For

example, as o f February 13, 1976 only one o f the

16 p o s i t i o n s o f watchman was h e l d by a b l a c k

employee.

2/ The t r a n s f e r r in g seasonal worker l o s e s not

only h is " c o m p e t i t i v e " s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s , e . g . ,

r i g h ts f o r job s e c u r i ty and promotion, but a lso

h i s " b e n e f i t " s e n i o r i t y r i g h t s , e . g . , r i g h t f o r

s i ck leave and v a c a t io n , except f o r ret irement

b e n e f i t s . Cf. Franks v . Bowman Transportat ion

C o . , 424 U.S. 747, TT5T5TT

- 12

The h i s t o r i c a l p r a c t i c e s o f d i s c r im in a t i o n

have continued to l im i t the employment o p p o r tu n i

t i e s o f b lack workers f o r su p erv iso r y as w e l l as

hour ly j o b s . Almost invarably the Company s e l e c t s

i t s s u p e r v i s o r y e m p lo y e e s f rom i t s f u l l - t i m e

s t a f f . The Company has never promoted a seasonal

w o rk e r d i r e c t l y t o a s u p e r v i s o r y p o s i t i o n .

The c o n t i n u a t i o n o f the e f f e c t s o f the p ast

s e g r e g a t iv e p r a c t i c e s has r e s u l t e d in the s e l e c

t i o n o f a d i s p r o p o r t i o n a t e l y small group o f the

Company 's b l a c k e m p lo y e e s as s u p e r v i s o r s . As

o f A p r i l , 1976, on ly 20/£ o f these p o s i t i o n s were

f i l l e d by b la c k s .

P r o p o sed Consent D e c r e e . D i s c o v e r y c o n

ducted by the p a r t i e s f o l l o w in g the commencement

o f t h i s lawsuit showed d ra m a t ic a l ly the degree to

which p a r t i c u l a r j o b c l a s s i f i c a t i o n s c o u l d be

i d e n t i f i e d by ra ce . I t a l so showed the extent to

which s e n i o r i t y ru les and t r a n s fe r ru les impinged

on the ca p a c i ty o f defendants to e r a d i c a te the

v e s t i g e s o f p a s t r a c i a l d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . The

part i e s , o f c o u r s e , had d i f f e r i n g views on the

extent to which such l i n g e r i n g e f f e c t s e x i s t . To

r e s o l v e t h e i r d i s a g r e e m e n t and t o s e t t l e the

co n t r o v e r s y , the p a r t i e s n eg o t ia ted a proposed

consent decree s e t t l i n g a l l c laims outstanding

be tw een them and p r e s e n t e d i t t o the d i s t r i c t

13

c o u r t , i n a c c o r d a n c e w i th Rule 2 3 ( e ) o f the

Federa l Rules o f C i v i l Procedure.

One o f the p r i n c i p a l fea tures o f the proposed

consent decree was a s e n i o r i t y c lause re q u ir in g

current and future employees to be c r e d i t e d with

a c t u a l t ime worked at the p l a n t as s e a s o n a l

e m p l o y e e s . A n o t h e r f e a t u r e o f the p r o p o s e d

c o n s e n t d e c r e e a l l o w e d s e a s o n a l em p lo y e e s to

t r a n s fe r to permanent j o b p o s i t i o n s as vacanc ies

o ccurred prov ided , o f c o u r s e , no regu lar employees

d e s i r e d the p o s i t i o n s . These p r o v i s i o n s were

patterned a f t e r the r e l i e f fashioned f o r seasonal

workers in R usse l l v. American Tobacco Company,

supra , 528 F .2d 357, 362-64 (4th C ir . 1975), c e r t .

d e n i e d , 425 U .S . 935 ( 1 9 7 6 ) . Under the f i r s t

above-mentioned fea ture o f the proposed consent

d ecr ee , seasonal workers are allowed to maintain

t h e i r s e n i o r i t y upon t r a n s f e r to regu lar p o s i

t i o n s . Under the second f e a tu r e , seasonal employ

ees are permitted to b id on vacanc ies in c l a s s

i f i c a t i o n s , such as watchmen, which were once

reserved f o r whites .

In a d d i t i o n , th e p r o p o s e d c o n s e n t d e c r e e

con ta in ed , in Part I I I , s e c t i o n 5, an a f f i r m a t iv e

a c t i o n p r o v i s i o n to reduce a h i s t o r i c a l underrep

r e s e n t a t i o n o f b la c k s which had e x i s t e d in the

14 -

su perv iso ry p o s i t i o n s . This p r o v i s i o n provided

t h a t :

The Richmond Leaf Department adopts a goa l o f

f i l l i n g the product ion superv isory p o s i t i o n s

o f Foreman and A s s i s ta n t Foreman with q u a l i

f i e d b lacks u n t i l the percentage o f b lacks

in such p o s i t i o n s equals 1/3 o f the t o t a l o f

such p o s i t i o n s . The d a t e o f December 31,

1980 i s h e r e b y e s t a b l i s h e d f o r the accom

plishment o f t h i s g o a l .

Furthermore, the consent decree e l iminated

the requirement that seasonal workers must serve a

p r o b a t i o n a r y p e r i o d when they t r a n s f e r t o a

f u l l - t i m e p o s i t i o n . F i n a l l y , the decree conta ined

a genera l i n j u n c t i o n p r o h i b i t i n g the defendants

from d i s c r i m i n a t i n g a g a i n s t b l a c k w ork ers and

a r e p o r t in g p r o v i s i o n re q u ir in g the Company to

submit f o r a th ree -year per iod s p e c i f i c rep or ts

d e t a i l i n g compliance with the Decree.

A l l o f the p a r t i e s found that these p r o v i

s ions represented , in l i g h t o f the h i s t o r y o f the

Richmond Leaf Department, a sett lement that was

r e a s o n a b l e , j u s t , and f a i r to a l l c o n c e r n e d .

Despite t h e i r agreement, the d i s t r i c t c o u r t , by

o rder f i l e d June 2, 1977, denied the j o i n t motion

o f the p a r t i e s to approve and enter the proposed

consent d ecree .

15

HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS WERE RAISED BELOW

A j o i n t motion was made by the p a r t i e s to the

d i s t r i c t court to approve and e n ter , pursuant to

the r e q u i r e m e n t s o f Rule 2 3 ( e ) o f the F e d e r a l

Rules o f C i v i l Procedure, the proposed consent

d e c r e e . The m o t i o n was d e n i e d . The d i s t r i c t

court o f f e r e d se v e ra l reasons in support o f i t s

r e f u s a l to grant the motion. F i r s t , the court

s ta te d that T i t l e VII o f the C i v i l Rights Act and

the due process c la u se o f the F i f t h Amendment to

the C o n s t i t u t i o n p r o h i b i t e d the c o u r t and the

d e f e n d a n t e m p lo y e r s and u n io n s from award ing

p r e f e r e n t i a l treatment to employees based upon

r a c e e x c e p t upon a showing o f p a s t o r p r e s e n t

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n . S e co n d , t h e c o u r t s a i d the

p r o p o s e d c o n s e n t d e c r e e was f a t a l l y f l a w e d in

s e e k in g t o p r o v i d e p r e f e r e n t i a l t r e a t m e n t f o r

b lack employees who were not shown to have been

v i c t im s o f d i s c r im in a t i o n . The court s ta ted that

the a b s e n c e o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n was e s t a b l i s h e d

by the f a c t t h a t the p r o p o s e d c o n s e n t d e c r e e

c o n t a i n e d a p r o v i s i o n in which the d e f e n d a n t s

denied that t h e i r a c t ion s had been d i s c r im in a to r y .

The issue o f the a p p e a la b i l i t y o f the d i s

t r i c t c o u r t ' s o rder was ra i se d when, upon appeal,

t h e Court o f A p p e a ls f o r the Fourth C i r c u i t

16

dismissed the appeal on the ground that the order

was n o n a p p e a l a b l e under 28 U .S .C . §§1291 and

1292 ( a ) ( 1 ) .

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The p e t i t i o n should be granted because o f a

c o n f l i c t between the c i r c u i t s . The importance

and complexity o f the i s su es are demonstrated by

the convening o f an en banc court and by the fact

that the o ther two C i r c u i t Courts o f Appeals which

have e x p l i c i t l y con s id ered the i ssues have ren

dered c o n f l i c t i n g d e c i s i o n s . The Fourth C i r c u i t

s p e c i f i c a l l y noted that i t s d e c i s i o n was in accord

w i th t h a t o f the Second C i r c u i t in S e i g a l v .

M err i ck , 590 F . 2d 35 (2d C ir . 1978) and contrary

to the d e c i s i o n o f the Ninth C i r c u i t in Norman v.

McKee, 431 F .2d 769 (9th C ir . 1970) c e r t . d e n ie d ,

401 U.S. 912 (1971 ) . The Fourth C i r c u i t ' s d e c i

s i o n a l s o c o n f l i c t s w i th the d e c i s i o n o f the

Eighth C i r c u i t in Re In te r n a t io n a l House o f Pan-

cakes Franchise L i t i g a t i o n , 487 F .2d 303 (8th C ir .

1973). The Second C i r c u i t in Seigal v. Merrick ,

supra , l i k e the Fourth C i r c u i t , e x p l i c i t l y s ta ted

tha t i t s d e c i s i o n t h e r e was i n c o n f l i c t w i th

Norman v . McKee, supra .

C i r c u i t Judges, Winter, Butzner, and Chief

Judge Haynswort’n d i s s e n te d below, h o ld in g that the

17

o r d e r was a p p e a l a b l e under § 1 2 9 2 ( a ) ( l ) as an

i n t e r l o c u t o r y o r d e r r e f u s i n g an i n j u n c t i o n .

The p e t i t i o n should a lso be granted because

o f the importance o f the i ssues r a i s e d . Two of

the i ssues concern a p p e a la b i l i t y o f orders under

the f e d e r a l a p p e a l s s t a t u t e s . The t h i r d , and

f i n a l , i s su e concerns the a b i l i t y o f l i t i g a n t s

to s e t t l e T i t l e VII c l a s s a c t i o n s , pursuant to

Rule 23(e ) o f the Federal Rules o f C i v i l Proce

dure, in accordance with c r i t e r i a set f o r th by

t h i s Court in U n i ted S t e e l w o r k e r s o f A m er ic a ,

AFL-CIO-CLC v . Weber, supra.

The f i r s t issue on a p p e a la b i l i t y i s whether a

d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s r e f u s a l to approve a proposed

consent decree i s ap pea lab le , notwithstanding the

" f i n a l i t y " requirement o f 28 U.S.C. §1291, under

the " c o l l a t e r a l o r d e r " d o c t r in e d escr ibed in Cohen

v . B e n e f i c i a l I n d u s t r i a l Loan C o r p . , 337 U.S.

----------------------------------------- j j ----------------------- — --------------------------- ---------------------

541 ( 1 9 4 9 ) . — The s e c o n d i s s u e r a i s e d in t h i s

p e t i t i o n i s whether such an order i s appealable

under 28 U .S .C . § 1 2 9 2 ( a ) ( l ) i f the p r o p o se d

consent decree in c lu d es , as h e re , a request fo r

i n j u n c t iv e r e l i e f and i f the c o u r t ' s d isapprova l

o f the decree i s based upon i t s determination that

a p p r o v a l i s p r o h i b i t e d by f e d e r a l law. The

3 / On t h i s i s s u e , the d e c i s i o n in Norman

v. McKee, supra , i s in c o n f l i c t with the d e c i s i o n

in Seigal v . M err i ck , supra , and with the d e c i s i o n

by the Court o f Appeals below.

18

answers to these quest ions turn upon the proper

i n t e r p r e t a t i o n and a p p l i c a t i o n o f 28 U.S.C. §§1291

and 1292 ( a ) ( 1 ) . This C ou r t 's response to these

i s s u e s w i l l be o f c r u c i a l i m p o r t a n c e to the

a b i l i t y o f l i t i g a n t s to s e t t l e ac t ions and the

e f f e c t u a t i o n o f Congress ional and j u d i c i a l p o l i

c i e s fa v o r in g sett lement o f a c t i o n s by l i t i g a n t s

themselves. A c c o r d : Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

£2.’ » U.S 36, 44 (1974 ) ; Regents o f the Uni-

v e r s i t y o f C a l i f o r n i a v . Bakke , 438 U.S 265,

364-65 (1978) (Opinion o f J u s t i c e s Bennan, White,

Marshall , and Blackmun).

The C o u r t ' s r e s o l u t i o n o f th e t h i r d i s s u e

w i l l dec ide whether the d e c i s i o n in Weber, supra,

can be used by l i t i g a n t s in pending a c t i o n s as a

b a s i s f o r sett lement o f p r iv a t e T i t l e VII a c t i o n s .

In p a r t i c u l a r , i t w i l l r e s o lv e the quest ion o f

w h eth er a d i s t r i c t c o u r t can s e i z e upon the

p a r t i e s ’ i n c l u s i o n , in a proposed consent order ,

o f an excu lpatory c la u s e , whereby defendant is

p e r m i t t e d to deny any d i s c r i m i n a t i o n a g a i n s t

p l a i n t i f f , as a bas is f o r denying approval o f a

consent decree which is in s t r i c t compliance with

Weber.

19

I.

THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER DENYING THE

PARTIES' JOINT MOTION IS APPEALABLE AS

A COLLATERAL ORDER UNDER 28 U .S .C . §1291.

P e t i t i o n e r s agree that the p o l i c y o f 28 U.S.C.

§1291 d i s f a v o r i n g appeals from nonf ina l orders i s

sa lu tary and must be re sp e c te d . Cooper & Lybrand

v . L i v e s a y , 437 U.S 463 , 471 (1 9 7 8 ) ; Gardner

v. Westinghouse Broadcast ing Co. , 437 U.S. 478,

480 (1978 ) . J u d i c i a l orders which do not r e s u l t

in a judgment terminat ing the e n t i r e a c t i o n are

g e n e r a l ly not f i n a l judgments with in the in tend

ment o f §1291. C a t l in v . United S t a t e s , 324 U.S.

229 (1945) . The purpose o f the f i n a l i t y r e q u i r e

ment is to prevent the d e b i l i t a t i o n o f j u d i c i a l

adm in is trat ion caused by piecemeal reviews o f a

s in g l e con tr oversy . Eisen v , C a r l i s l e & Jacque-

l_in_, 417 U.S 156, 170 (1974). C at l in v. United

S t a t e s , 324 U.S. at 233. See Cohen v. B e n e f i c i a l

I n d u s tr ia l Loan Corp. , supra , 337 U.S. at 546.

This p o l i c y , however, i s not f r u s t r a te d by p e r

m it t in g appeals on c e r t a i n c o l l a t e r a l orders that

cannot be reviewed e f f e c t i v e l y on appeal from a

f i n a l judgment. Cohen v. B e n e f i c i a l In d u s tr ia l

Loan Corp. , supra , 337 U.S. at 546.

To insure that cou r ts do not use th is excep

t i o n perm it t ing appeals o f c o l l a t e r a l orders to

d e fea t the obvious in tent o f the s t a t u t e , th is

Court has he ld that the e x cep t ion i s only a p p l i c

able t o the small c l a s s o f orders which

- 20

f i n a l l y determine claims o f r i g h t separab le

from and c o l l a t e r a l t o , r i g h t s a sser ted in

the a c t i o n , too important to be denied review

and too independent o f the cause i t s e l f to

r e q u i r e t h a t a p p e l l a t e c o n s i d e r a t i o n be

d e f in ed u n t i l the whole case is ad ju d ica ted .

Cohen, supra , 337 U.S. at 546.

The c o l l a t e r a l order d o c t r in e i s a p p l i c a b le

i f ( 1 ) the m e r i t s o f the c o l l a t e r a l o r d e r are

separate and independent from the meri ts o f the

a c t i o n i t s e l f , ( 2 ) th e c o l l a t e r a l o r d e r has

f i n a l l y determined the " c o l l a t e r a l ” r i g h t s , (3 )

s e r i o u s and i r r e p ar ab le in ju ry has been caused by

the c o l l a t e r a l o rd e r , and (4 ) the c o l l a t e r a l order

cannot be e f f e c t i v e l y reviewed on appeal.

The order o f the d i s t r i c t court below s a t

i s f i e s each o f these four c r i t e r i a . The d i s t r i c t

c o u r t ' s order denying approval o f the proposed

consent decree determined c o n c l u s i v e l y and f i n a l l y

f o r the p a r t i e s h e r e i n w h eth er an a f f i r m a t i v e

a c t i o n plan s a t i s f y i n g the requirements o f Weber

can be used as the b a s i s f o r s e t t l i n g the l i t i g a

t i o n . In Weber, t h i s Court upheld the v a l i d i t y o f

an a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n p la n p r o v i d i n g r e m e d ia l

r e l i e f to m i n o r i t i e s who worked in occupat ions

which had t r a d i t i o n a l l y been c l o s e d to them. This

Court no ted t h a t the p la n approved in Weber

between the United Steelworkers o f America and

Kaiser Aluminum & Chemical C o r p . , l i k e the one

h e r e , d i d not r e q u i r e the d i s c h a r g e o f w h i t e

21

workers or o therwise u n n e c e ss a r i ly trammel upon

the i n t e r e s t s o f white employees. Moreover, the

p lan, again l i k e h ere , was vo luntary and designed

t o b r e a k down t r a d i t i o n a l p a t t e r n s o f r a c i a l

s e g re g a t io n and h i e r a r c h y . A d d i t i o n a l l y , the plan

in Weber, l i k e the plan here , d id not c r e a t e an

a bso lu te bar to the advancement o f white employ

ees . I t was temporary and was created to e l im in

ate a mani fest r a c i a l balance and not to maintain

r a c i a l ba lance . F i n a l l y , both the plan in Weber

and the plan envis ioned by the consent decree did

n o t r e q u i r e a p e r c e n t a g e o f b l a c k e m p loy ees

g rea ter than that o f b lacks in the labor f o r c e .

In approving the v a l i d i t y o f the Kaiser plan,

th i s Court he ld that the v a l i d i t y o f the plan was

independent o f whether Kaiser or United S t e e l

workers had d i s c r im in a te d against b lacks and was

independent o f whether any o f the b lack employees

who were to b e n e f i t from the plan were themselves

v i c t i m s o f d i s c r i m i n a t i o n by e i t h e r K a i s e r o r

4 /

U n ited S t e e l w o r k e r s . — The p r o p o s e d c o n s e n t

d e c r e e r e j e c t e d by the d i s t r i c t c o u r t b e l o w

had an a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n component e x a c t l y l i k e

4 / To t h i s extent the d e c i s i o n in Weber tracks

the d e c i s i o n in Regents o f the U nivers i ty o f Ca l i f

o r n i a v . B a k k e 4 38 uTsT 265 (1 9 78 ) where the

Court approved the l im ite d use o f r a c e - c o n s c i o u s

plans without r e s t r i c t i n g t h e i r use to v i c t im s o f

d i s c r im in a t i o n by the o r i g i n a t o r s o f the plans.

22

the p lan in Weber. Moreover, the s o le bas is f o r

the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s r e j e c t i o n o f the proposed

decree was the in c l u s i o n o f an a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n

plan in the absence o f p r o o f o f d i s c r im in a t i o n

by de fendants against p l a i n t i f f s and the c l a s s

members.

Thus, in r e j e c t i n g the decree , the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t made a f i n a l determinat ion o f the p a r t i e s '

r i g h t to s e t t l e the a c t i o n with a j u d i c i a l decree

i n c o r p o r a t i n g a program o f a f f i r m a t i v e a c t i o n

based upon Weber. The op in ion o f the d i s t r i c t

cou r t that a l e g a l impediment e x i s t e d to approval

o f the consent decree was a f i n a l determinat ion

which was not c o n d i t i o n e d upon any fu r th er a c t i o n

be ing taken by one or both o f the p a r t i e s . The

i s sues thereby dec ided by the d i s t r i c t court were

separate and independent o f the i ssues r a i s e d in

the T i t l e VII a c t i o n s i n c e , in order to p r e v a i l in

that a c t i o n , the p e t i t i o n e r s must show that they

and the members o f the c l a s s are v i c t i m s o f

d i s c r i m i n a t i o n by d e f e n d a n t s . See Franks v .

Bowman Transportat ion Co. , 424 U.S. 747 (1976);

Teamsters v . United S t a t e s , 431 U.S. 324 (1977).

M o r e o v e r , th e o r d e r o f the d i s t r i c t c o u r t

below cannot be e f f e c t i v e l y reviewed upon appeal

from a f i n a l judgment in t h i s case s in ce such a

judgment would merely conf irm that the p e t i t i o n e r s

had l o s t the very r i g h t which they were seeking to

- 23

p r o t e c t , namely the r i g h t to s e t t l e the a c t i o n

without going to t r i a l . The order w i l l unques

t i o n a b ly cause i r r e p ar ab le in ju ry to p e t i t o n e r s

and respondents s in ce i t r eq u ires them to conduct

an u n n e c e s s a r y , e x p e n s i v e , and t im e - c o n s u m in g

t r i a l .

S a n c t i o n i n g an a p p e a l in t h i s c a s e i s not

i n c o n s i s t e n t w i th the d e c i s i o n in C ooper and

Lybrand v , L iv e s a y , 437 U.S 463 (1978) , where the

Court, in not perm it t ing an appeal o f a d i s t r i c t

c o u r t ' s den ia l o f a c la s s c e r t i f i c a t i o n order ,

warned against a p p e l la t e cour ts in d i s c r im in a t e ly

th ru s t in g themselves in to the t r i a l p r o c e s s . 437

U.S at 476. What i s at issue here i s the v a l i d i t y

o f a r u l e o f law p r o m u lg a te d by the d i s t r i c t

court which a s s e r t s that the p r i n c i p l e s en u n c ia t

ed in Weber cannot l a w f u l ly be in corpora ted in to a

c l a s s a c t i o n s e t t l e m e n t . I t i s n o t an i n d i s

cr iminate in t r u s i o n in to the t r i a l p rocess to say

t h a t the o r d e r embodying t h i s r u l e o f law i s

rev iewable upon appeal.

The co n s id e r a t i o n s favor in g a p p e a la b i l i t y in

t h i s c a s e p a r a l l e l t h o s e in G i l l e s p i e v . U . S .

S tee l Corp. , 379 U.S 148 (1964 ) , where the Court

a llowed an appeal from a ru l in g o f the d i s t r i c t

cou r t s t r i k i n g var iou s a l l e g a t i o n s o f the com

p l a i n t p e r m i t t i n g r e c o v e r y , and in M e r c a n t i l e

National Bank at Dallas v. Langdeau, 371 U.S. 555

(1963) , where an appeal was permitted o f an order

by the Texas Supreme Court r e j e c t i n g the d e fen

d a n t ' s venue o b j e c t i o n s . These cases re cogn ized

that a c o l l a t e r a l o rder i s appealable when the

m eri ts o f the c o l l a t e r a l co n tr o v e rsy are separate

and apart from the meri ts o f the main a c t i o n . — ̂

In l i g h t o f t h i s C ou r t 's d e c i s i o n in United States

S t e e l w o r k e r s o f A m e r i c a , AFL-CIO-CLC v , Weber,

supra , the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s o rder d isapprov ing the

p r o p o s e d c o n s e n t d e c r e e d o e s not i n v o l v e the

important fa c t u a l and l e g a l i ssues r a i s e d in the

T i t l e VII a c t i o n . See Teamsters v . United S tates ,

supra.

- 24 -

I I .

THE DISTRICT COURT'S DISAPPROVAL OF THE

PROPOSED CONSENT DECREE IS APPEALABLE AS AN

INTERLOCUTORY ORDER UNDER 28 U.S.C. §1292

( a ) ( 1 ) .

Read l i t e r a l l y , § 1 2 9 2 ( a ) ( l ) , p rov id in g f o r

appeals o f i n t e r l o c u t o r y orders o f d i s t r i c t cou r ts

g r a n t i n g o r r e f u s i n g i n j u n c t i o n s , i s c l e a r l y

a p p l i c a b l e t o the o r d e r o f the d i s t r i c t c o u r t

be low. It was so he ld by the d i s s e n t in g judges

5J A p p l i c a t i o n o f Cohen req u ires that the m er i ts

o f the c o l l a t e r a l o rder not be "enmeshed in the

fa c t u a l and l e g a l i ssues compr is ing the p l a i n

t i f f ' s cause o f a c t i o n . " Mercant i le Nat. Bank v .

Langdeau, supra , 371 U. S at 558.

- 25

below. They h e ld that the order o f the d i s t r i c t

j u d g e was an i n t e r l o c u t o r y o r d e r r e f u s i n g an

i n ju n c t i o n . The con trary d e c i s i o n o f the m a jo r i ty

was based upon t h e i r b e l i e f that d e c i s i o n s o f th is

Court have put a g l o s s on the p la in meaning o f the

s t a t u t e . See Switzerland Cheese A s s o c i a t i o n , Inc .

v . E. Horne 's Market, I n c . , 385 U.S. 23 (1966 ) ;

L iber ty Mutual Ins . Co. v , W etz e l , 424 U.S 737

(1976 ) ; Gardner v, Westinghouse B roadcast ing Co . ,

437 U.S. 478 (1978) .

The m a j o r i t y o f the Court o f A p p ea ls h e l d

t h a t t h e s e d e c i s i o n s l i m i t the a p p l i c a t i o n o f

§ 1 2 9 2 (a ) (1 ) to orders that are " i n t e r l o c u t o r y " in

a s p e c i a l sense o f the meaning o f the term i n t e r

l o c u t o r y . Cases such as S w i t z e r l a n d Cheese

A s s o c i a t i o n , I n c , v . E. H o r n e ' s M arket , I n c . ,

supra ( d i s a l l o w in g an appeal o f an order denying

a motion f o r summary judgment request ing in ju n c

t i v e r e l i e f ) and L i b e r t y Mutual I n s , Co. v .

W e tz e l , supra (denying appeal o f a judgment f i x i n g

l i a b i l i t y w h i l e p o s t p o n i n g d e t e r m i n a t i o n on a

r e q u e s t f o r permanent i n j u n c t i v e r e l i e f ) were

c i t e d as a u th o r i ty f o r t h i s p r o p o s i t i o n .

P e t i t i o n e r s contend that th is C ou r t 's d e c i

s ions have set f o r th the f o l l o w in g c r i t e r i a f o r

a p p l i c a t i o n o f 1 1 2 9 2 ( a ) (1 ) . F i r s t , the order must

be p r e l i m i n a r y , i . e . , one tha t i s made b e f o r e

t r i a l and i s u n c o n d i t i o n a l . Switzerland Cheese

26

A s s o c i a t i o n v . E. Horne's Market, In c . , supra , 385

U.S at 25. Second, the order must do more than

merely d i r e c t the case to proceed to t r i a l . I d . ,

385 U.S. at 25. A ls o , Baltimore C on trac to rs , I n c .

v. Bod inger , 348 U.S 176 (1955) (an order r e f u s in g

to stay r e f e r r a l o f an issue from a r b i t r a t i o n is

not appea lab le under 1 1 2 9 2 ( a ) ( 1 ) ) .

T h i r d , th e o r d e r must s e t t l e , e i t h e r t e n

t a t i v e l y or f i n a l l y , some a spects o f the m er i ts o f

the c la im s . Switzerland Cheese A s s o c ia t i o n v . E.

H o r n e ' s M arket , I n c . , s u p r a , 385 U.S a t 25;

Gardner v . Westinghouse Broadcast ing Co. , supra ,

437 U.S. at 481-82. Fourth, the order must "pass

on the l e g a l s u f f i c i e n c y o f the c la im f o r i n j u n c -

t i v e r e l i e f . " Gardner, supra, 437 U.S. at 481.

F i f t h , the o r d e r must h a v e an " i r r e p a r a b l e "

e f f e c t . I d . , 437 U.S. at 480. F i n a l l y , the order

must not be one which can be reviewed "both p r i o r

to and a f t e r f i n a l judgment. " Id.

Whether t h e s e s i x c r i t e r i a a r e the p r o p e r

ones f o r d e t e r m i n i n g the a p p e a l a b i l i t y o f an

i n t e r l o c u t o r y decree under 51292 (a ) (1 ) and whether

an order re fu s in g approval o f a proposed consent

o r d e r e n co m p a ss in g a r e q u e s t f o r i n j u n c t i v e

r e l i e f s t a t i s f i e s these c r i t e r i a are important

i s s u e s a f f e c t i n g s u c c e s s f u l a d m i n i s t r a t i o n

o f 5 1 2 9 2 (a ) (1 ) .

27

P e t i t i o n e r s contend that each o f these s ix

c r i t e r i a i s s a t i s f i e d by the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s

decree d isapprov ing the proposed consent decree .

There i s no d ou b t t h a t the d e c r e e h e r e i n was

p re l im in ary , u n c o n d i t i o n a l , and that i t dec ided

something other than that the p a r t i e s must go to

t r i a l . The o r d e r e f f e c t i v e l y d e c i d e d t h a t an

a f f r im a t i v e a c t i o n plan i d e n t i c a l to that in Weber

cou ld not be used, absent p r o o f o f d i s c r im in a t i o n ,

as a b a s i s f o r sett lement o f a T i t l e VII a c t i o n .

Thus, the order had the l e g a l e f f e c t o f p rec lud ing

defendants from withdrawing t h e i r de fense o f p r i o r

d i s c r im in a t i o n , or from admitt ing the o ccurrence

o f such d i s c r im in a t i o n , and cont inu ing the l i t i g a

t i o n on that b a s i s . In t h i s l i g h t , the order o f

the d i s t r i c t c o u r t , when cons idered from the per

s p e c t i v e o f i t s l e g a l impact on de fendants ' a b i l i

ty to modify or withdraw t h e i r d e fen se , i s an a lo

gous to the s i t u a t i o n s in Sears , Roebuck & Co. v .

Mackey, 351 U.S. 427 ( 1 9 5 6 ) (appeal i s a l low ab le

from order d i sm iss in g two o f p l a i n t i f f ' s c la im s)

and in Cold Metal Process Co. v. United Eng'r &

Foundry Co. , 351 U.S. 445 (1956) (appeal al lowed

o f o r d e r d i s m i s s i n g c o u n t e r c l a i m where i t was

based on t ra n sa c t i o n s s im i la r t o those in p l a i n

t i f f ' s c l a i m s ) .

- 28 -

The o r d e r d i s a p p r o v i n g the c o n s e n t d e c r e e

touched on the merits o f p l a i n t i f f s ' c laims in a

u n iq u e and s i g n i f i c a n t way. I t p r e l i m i n a r i l y

re s o lv e d the i s sue o f the l e g a l s u f f i c i e n c y o f

the T i t l e VII cla ims by h o ld in g that the h i s t o r y

o f de fen d an ts ' employment p r a c t i c e s and p o l i c i e s

d i d not d i s c l o s e an a d e qu a te l e g a l b a s i s f o r

conc lud ing that defendants had ever d is cr im inated

against b la c k s . Although t h i s aspect o f the order

might c o n c e iv a b ly be rev iewable upon appeal from a

f i n a l judgment, that aspect o f the judgment which

depr ived the p a r t i e s o f the oppor tu n ity to fash ion

a sett lement in accordance with Weber cannot be so

reviewed. F i n a l l y , the order had an i r r ep ar ab le

e f f e c t on the p a r t i e s by f o r c i n g them to undergo

an expens ive , unwanted, and unwarranted, t r i a l .

I l l

RULE 2 3 ( e ) DOES NOT AUTHORIZE A FEDERAL

DISTRICT COURT TO DISAPPROVE A SETTLEMENT

MEETING THE REQUIREMENTS OF WEBER ON THE

GROUND THAT THE CLASS MEMBERS ARE NOT NECES

SARILY VICTIMS OF DISCRIMINATION BY THE

DEFENDANTS

The p a r t i e s ' e v a lu at ion o f d i s c o v e r y data and

th e i r assessement o f the m er i ts , e s ta b l i s h e d a

b a s i s f o r s e t t l e m e n t o f the a c t i o n on terms

r e a s o n a b l e and f a i r . The n e g o t i a t i o n s f o r

the sett lement were complex and d i f f i c u l t . For

29

two m on th s , from F e br u ar y 1977 to March 1977,

counsel labored at t ry in g to f ind terms which were

a c c e p t a b l e to a l l a f f e c t e d . In the p r o p o se d

d e c r e e , each p a r t y s t a t e d th a t i t was n o t a d

m i t t in g that i t p re v io u s ly s ta ted p o s i t i o n was

6 /

wrong.— Based upon the data d i s c l o s e d through

d i s c o v e r y , r e a s o n a b l e s e t t l e m e n t r e q u i r e d the

c o r r e c t i o n o f the v e s t i g e s o f e a r l i e r d i s c r im in a

t i o n . The proposed consent decree purported to do

t h i s by undoing the e f f e c t s o f the d i s c r im in a to ry

p r a c t i c e s . Defendants were s p e c i f i c a l l y en jo ined

to take a c t i o n which had the e f f e c t o f r e v e r s in g

the d i s c r im in a to r y r u l e s .

6 / Thus, the f i n a l d r a f t o f the agreement pro

v ided that

Defendants ex p r e s s ly deny any v i o l a t i o n

o f the F o u r t e e n t h Amendment o f the U nited

States C o n s t i tu t i o n , T i t l e VII o f the C i v i l

Rights Act o f 1964, as amended, or any o ther

equal employment law, r e g u l a t i o n or order .

T h is D e cre e and Consent h e r e t o does not

c o n s t i t u t e a f i n d i n g o r a d m is s i o n o f any

unlawful or d i s c r im in to r y conduct by d e fen

dants .

P l a i n t i f f s ’ consent to t h i s Decree does

not c o n s t i t u t e a f in d in g or admission that

any o f the employment p r a c t i c e s o f the

Richmond L e a f Department o f the American

T o b a c c o Company, a d i v i s i o n o f American

Brands, I n c . , are unlawful.

- 30

The a c t i o n o f the d i s t r i c t court in r e j e c t i n g

f o r the reasons which i t did the p a r t i e s ' j o i n t

motion f o r approval o f the proposed consent decree

has s e r i o u s l y undermined t h i s C o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n in

United Steelworkers o f America v. Weber, supra , as

w e l l as undermined the s u c c e s s fu l implementation o f

Congress ional p o l i c i e s fa v or in g vo luntary s e t t l e

ment o f d i s c r im in a t i o n c a se s . See Alexander v .

Gardner-Denver C o . , supra, 415 U.S. at 44. In i t s

recent d e c i s i o n in Weber, t h i s Court took great

pains to emphasize to p r iv a te p a r t i e s covered by

T i t l e VII that they c o u ld , without fea r o f be ing

he ld in v i o l a t i o n o f T i t l e VII , v o l u n t a r i l y nego

t i a t e and implement r a c e - c o n s c i o u s , remedial plans

whenever those plans were prop er ly designed so that

they d id no more than c a rr y out the e s s e n t i a l pur

poses o f T i t l e VII.

Those purposes are b a s i c a l l y as f o l l o w s : (1 )

to break down o ld patterns o f r a c i a l h ie r a r c h y ;

(2 ) t o "open employment o p p o r tu n i t i e s f o r Negroes

in o c c u p a t i o n s w hich have b e e n t r a d i t i o n a l l y

c l o s e d to them," Remarks o f Senator Hubert Hum

phrey, 110 Cong. Rec . 6548; (3 ) to e l im in ate i n

stances o f mani fest r a c i a l b a la n c e ; and (4 ) to

p r o h i b i t undue e f f o r t s to maintain r a c i a l b a l

ances . This Court he ld in Weber that a f f i r m a t iv e

a c t i o n p la n s e f f e c t u a t i n g t h e s e p u r p o s e s were

31

l a w f u l as l o n g as t h e y d i d not u n n e c e s s a r i l y

trammel upon the in t e r e s t s o f white employees by

r e q u i r i n g t h e i r d i s c h a r g e or by c r e a t i n g an

a bso lu te bar to t h e i r advancement or by perm itt ing

a g rea ter percentage o f m in or i ty employees to be

b e n e f i t t e d under the plan than which e x i s t s in

the l o c a l l a b o r f o r c e . Such p la n s were a l s o

r e q u i r e d t o be te m p o r a r y s i n c e o t h e r w i s e they

would f o r e s e e a b ly opera te to maintain an improper

r a c i a l ba lance .

A l th o u g h a d e c i s i o n on the c o r r e c t n e s s

o f the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s d isapprova l o f the pro

p o s e d c o n s e n t d e c r e e n e c e s s a r i l y r a i s e s the

genera l issue o f what c r i t e r i a are to govern an

e x e r c i s e o f the d i s t r i c t c o u r t ' s power to accept

o r r e j e c t s e t t l e m e n t s under Rule 2 3 ( e ) , s e e

Fl inn v.FMC Corporat ion , 528 F.2d 1169 (4th Cir.

1975), c e r t , d e n ie d , 424 U.S. 969 (1976 ) ; P a t te r

son v . Newspaper & Mail D e l . U. o f N.Y. & Vic . ,

514 F . 2d 767 (2d C ir . 1975), c e r t , d e n ie d , 427

U.S 911 (1976 ) , the only s p e c i f i c i s sue which must

be determined here is the power o f the d i s t r i c t

c o u r t to d i s a p p r o v e a p r o p o s e d c o n s e n t o r d e r

merely because i t prov ides f o r an a f f i r m a t iv e

a c t i o n plan based on p r i n c i p l e s approved in Weber

and i n s t i t u t e d on b e h a l f o f m in or i ty employees who

32

have not been shown to be v i c t im s o f d i s c r im in a

t i o n by de fendants .

Put another way, the p r e c i s e qu est ion which

has to be d e c i d e d i s w hether Rule 2 3 ( e ) can

be u t i l i z e d by a d i s t r i c t court to e f f e c t i v e l y

" o v e r r u l e " t h i s C o u r t ' s d e c i s i o n in Weber and to

f r u s t r a t e f e d e r a l p o l i c i e s f a v o r i n g v o l u n t a r y

s e t t l e m e n t o f l e g a l d i s p u t e s . Subsumed under

t h i s q u e s t i o n i s the q u e s t i o n o f w h eth er the

d i s t r i c t c o u r t , under the gu ise o f e x e r c i s i n g i t s

d i s c r e t i o n under Rule 2 3 ( e ) , can determine, as

i t d i d , t h a t , as a m a t t e r o f f e d e r a l la w , t h e

implementation o f a remedial scheme o f p r e f e r e n

t i a l employment f o r m i n o r i t i e s based upon p r in

c i p l e s se t f o r th in Weber i n f r in g e thereby , in the

absence o f p r o o f o f d i s c r im in a t i o n by defendants

against m in or i ty employees, upon the c o n s t i t u

t i o n a l r i g h t s and s t a t u t o r y r i g h t s o f w h i t e

e m p l o y e e s . P e t i t i o n e r s c o n t e n d th a t such an

a c t i o n by a d i s t r i c t cou r t i s an abuse o f power

under Rule 23(e) which re q u i re s immediate c o r r e c

t i o n .

33

C O N C L U S I O N

For Che reasons set f o r t h h ere in , p e t i t i o n e r s

request that t h e i r p e t i t i o n be granted.

R e s p e c t f u l l y submitted,

HENRY L. MARSH, I I I

WILLIAM H, BASS, I I I

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

H i l l , Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

P.0. Box 27363

Richmond, V i r g in ia 23261

JOHN W. SCOTT, JR.

615 Caro l ine Sreet

F reder icksburg , V i r g in ia 22401

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

Suite 2030

10 Columbus C i r c l e

New York, New York 10019

COUNSEL FOR PETITIONERS

APPENDIX

Decisions of the Courts Below

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F o b t h e F o u r t h C ir c u it

No. 77-2260

F r a n k L . C a r s o n , L a w r e n c e H a t c h e r , S t u a r t E. M i n e s ,

v.

A p p e lla n ts ,

A m e r ic a n B r a n d s , I n c ., t / a T h e A m e r ic a n T o b a c c o C o m

p a n y ; L o c a l 1 8 2 , T o b a c c o W o r k e r s I n t e r n a t i o n a l ,

T o b a c c o W o r k e r s I n t e r n a t i o n a l U n i o n ,

A p p e lle e s .

Appeal from the United States District Court

For the District of Richmond, Virginia

Decided En Banc September 14, 1979

Reported at 606 F.2d 420

Before

H a y n s w o r t h , C h ie f J u d ge,

a n d W i n t e r , B u t z n e r , R u s s e l l , W i d s n e r ,

H a l l a n d P h i l l i p s , C ircu it J u d ges.

K. K. H a l l , C ircu it J u d g e :

Plaintiffs seek an interlocutory appeal under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1292(a)(1) of the district court’s refusal to enter a con

sent decree agreed to by the named parties in a Title VII

class action.

l a

2a

Tlie suit is based on claims of race discrimination and

is brought against employer and union on behalf of black

workers and black applicants for employment at an Amer

ican Tobacco Company plant in Richmond, Virginia, The

decree would grant money damages and hiring and senior

ity preferences to black employees and would set a goal re

quiring the employer to give preference to blacks in hiring

for supervisory positions until a certain number of qualified

blacks were employed. The decree was negotiated by repre

sentative plaintiffs, and it provides for notice to all class

members.

The named plaintiffs contend that this relief is injunctive

in nature, and, because the district court refused to enter

the decree, its order is immediately appealable under

§ 1292(a)(1) as a denial of injunctive relief. We disagree.

The district court’s order refusing entry of the decree

does not deny any relief, whatever its nature. It merely

requires the parties to either revise the decree or proceed

with the case by trial or motions for summary judgment.

The immediate consequence of the order is continuation of

the litigation and, because the merits of the decree can be

reviewed following final judgment, we think it is not an

appealable order under § 1292(a) (1). Accordingly, we dis

miss the appeal.

I .

In F lin n v. F M C C orp ora tion , 528 F.2d 1169 (4th Cir.

1975), cert, den ied , 424 U.S, 967, 96 S.Ct. 1462, 47 L.Ed.2d

734 (1976), we heard the appeal of individual class plain

tiffs alleging that the district court abused its discretion

by entry of a consent decree in a Title VII sex discrimina

tion class action. There, the overwhelming majority of

class members had voted to adopt the decree, and the dis-

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

3a

trict court entered it on the “eve of trial.” With scholarly

care, Judge Russell surveyed various interests supporting

entry of the decree and posited the rule that, when a dis

trict court is presented with a consent decree, it should

view the merits of the decree in light favorable to its

entry. That is, it should, without requiring technical per

fection or legal certitude, determine whether the law and

the facts of record argu ably support its terms. Under this

standard, he identified factors which the district court

should consider in exercising its discretion. These included

“the extent of discovery that has taken place, the stage of

the proceedings, the want of collusion in the settlement,

and the experience of counsel who may have represented

plaintiffs in the negotiation.” Id . at 1173.

Plaintiffs argue that the district court erred in failing to

consider the proposed decree under the liberal standards of

F lin n 1 and that its refusal to enter the decree is immedi

ately appealable. Although we think the district court

should have reviewed the proposed decree under F lin n , we

do not think its refusal to approve the decree is a matter

properly within our jurisdiction prior to final judgment.

In F lin n , the district court’s en try of the decree termi

nated the action, whereas here the district court’s order

refusing it has no such effect—it continues the proceedings,

making our review of it an interlocutory appeal.

II.

As a general rule appeals of right from interlocutory

trial court decisions are not favored. '28 U.S.C. § 1291.

1 Counsel in this ease failed to cite Flinn to the district court in

their three separate memoranda of law filed in support of the pro

posed decree and failed to move the court following its order to

reconsider in light of that case. Instead, they immediately brought

this appeal.

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

4a

B a ltim o re C on tra cto rs , In c . v. B o d in g er , 348 U.S. 176, 75

S.Ct. 249, 99 L.Ed. 233 (1955); C o o p ers $ L y b ra n d v. L iv e -

sa y , 437 U.S. 463, 98 S.Ct. 2454, 2459, 57 L.Ed.2d 351 (1978);

G a rd n er v. W estin g h o u se B roa d ca stin g C o., 437 U.S. 478,

98 S.Ct. 2451, 2453, 57 L.Ed.2d 364 (1978). They disrupt

the trial process, slow the course of litigation and create

unnecessary multiple appeals. A single appeal following

final judgment facilitates orderly litigation and comprehen

sive appellate review of all issues presented, many of which

are dependent upon or related to other issues in the suit.

After final judgment, the fact issues have been settled in

the appropriate forum, and appellate review can he dis

positive of all issues in the case. S ee, C o o p ers & L yb ra n d

v. L iv esa y , 98 S.Ct. at 2460-61.

In the interests of justice, appeals of right from inter

locutory orders are allowed when the delay in hearing an

appeal after final judgment poses some irreparable conse

quence, G ard n er v. W estin g h o u se B roa d ca stin g C o., 98 S.Ct.

at 2453, or when the issue to be determined is sufficiently

collateral to the ongoing litigation that no disruption of the

trial process will attend early appellate review, se e C ohen

v. B en eficia l In d u stria l L oa n C orp ., 337 U.S. 541, 546-47, 69

S.Ct. 1221, 93 L.Ed. 1528 (1949); C o o p ers & L yb ra n d v.

L iv esa y , 98 S.Ct. at 2459.

Special statutory exceptions to the final judgment rule

are set forth in 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a). Plaintiffs argue that

characterization of the refused relief as “injunctive” is

sufficient to meet the plain terms of § 1292(a)(1), which

reads in pertinent part,

The court of appeals shall have jurisdiction of appeals

from: (1) Interlocutory orders of the [district courts]

granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

5a

injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify injunc

tions. . . .

But a mere labeling of relief is not sufficient. S ee C ity

o f M orga n tow n , W . Va. v. R o y a l In s . C o., 337 U.S. 254, 258,

69 S.Ct. 1067, 93 L.Ed. 1347 (1949). Courts look to the

consequence of postponing appellate review following final

judgment and weigh the need for immediate appeal against

the important judicial interests militating against piece

meal review. S ee G ard n er v. W estin g h o u se B roa d ca stin g

C o., 98 S.Ct. at 2454; C o o p ers & L y b ra n d v. L iv esa y , 98

S.Ct. at 2460. This test is applied to appeals in class actions

as well as to those in ordinary litigation.2 Under this test,

we find no appeal of right from orders refusing consent

decrees at any time before final judgment.

III.

The consequence of the district court’s order is not ir

reparable. No right is forfeited as a result of delayed

review. Here, injunctive relief was not finally denied; it

was merely not granted at this stage in the proceedings.

S ee L ib e r ty M u tu al In su ra n ce C om p a n y v. W e'tsel, 424 U.S.

737, 744-45, 96 S.Ct. 1202, 47 L.Ed.2d 435 (1976)/ Like the

denial of a motion for summary judgment which, if granted,

would include injunctive relief, the denial of this consent

decree decided “only one thing—that the case should go to

2 A s the Court noted in Coopers Lybrand v. Livesay, 98 S.Ct.

at 2459:

There are special rules relating to class actions and, to that

extent, they are a special kind of litigation. Those rules do not,

however, contain any unique provisions governing appeals.

The appealability of any order entered in a class action is de

termined by the same standards that govern appealability in

other types of litigation.

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

6a

trial.” S w itzerlan d C h eese A sso c ia tio n , In c . v. E . H o rn e ’ s

M a rk e t , In c ., 385 U.S. 23, 25, 87 S.Ct. 193, 195, 17 L.Ed.2d

23 (1966).

In G ard n er v. W estin g h o u se B roa d ca stin g C o., 437 U.S.

478, 98 S.Ct. 2451, 57 L.Ed.2d 364 (1978), the Supreme

Court held that the pretrial denial of class certification in

a Title YII case was not appealable under § 1292(a)(1) as

a. denial of injunctive relief. In that case, which involved

allegations of sex-based discrimination, the complainant

sought broad injunctive relief for the class similar to the

relief proposed in the decree before us. The Court reasoned

that the pretrial order denying class certification was not

one of irreparable consequence since it could be reviewed

at any stage of the proceedings either before or after final

judgment, did not affect the complainant’s personal claim

for injunctive relief, and did not pass on the legal sufficiency

of any claim for injunctive relief. Id . 98 S.Ct. at 2453-54

and notes 7, 8 and 9 (citing S w itzerla n d C h eese ).

TV.

The analogous consequences of a district court’s disap

proval of a settlement in a class action and its refusal to

grant summary judgment were considered by the Second

Circuit in S eiga l v. M err ick , 590 F.2d 35 (2nd Cir. 1978).

The issue there was whether, in a stockbroker derivative

action, the court’s order refusing settlement was appealable

before final judgment.

Relying upon the analysis in C o o p ers & L y lr a n d v. L iv e -

sa y , 437 U.S. 463, 98 S.Ct. 2454, 57 L.Ed.2d 351 (1978), a

case decided the same day as G ardner, the S eiga l court

discussed the judicial and private interests always present

where the rights of represented and unrepresented indi

viduals may be compromised by the court’s approval of a

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

7a

settlement. The court explained the purpose of requiring

class action settlements to be presented to district courts

under Fed.E. Civ.Proe. 23.1.

[A]n order disapproving a settlement . . . is based,

in part, upon an assessment of the merit of the posi

tions of the respective parties, and permits the parties

to proceed with the litigation or to propose a different

settlement.

A settlement in an ordinary civil litigation is nor

mally the sole concern of the parties. In stockholder

derivative actions, on the other hand, because of the

vicarious representation involved, the court has a duty

to perform before an action can be “settled.” . . . This

approval cannot be a rubber stamp adoption of what

the parties alone agree is fair and equitable.

S eiga l v. M errick , 590 F.2d at 37-38. The court pointed out

that disallowing appeals of right from each refusal to enter

a settlement had the practical effect of enhancing the dis

trict court’s control over the litigation.

[T]he denial of one compromise does not necessarily

mean that a “sweetened” compromise may not be ap

proved. The management of a derivative suit gives

the trial judge a chance not only to disapprove a com

promise but to edge the parties toward more equitable

terms.

Id. at 39.

The S eiga l court reasoned that a rule allowing appeals

of right from orders refusing entry of settlements was

unjustified. It would interrupt the litigation and thrust ap

pellate courts indiscriminately into the trial process with

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

8a

out appreciable benefit to class members whose interests

were to be protected.

Therefore, the court concluded that such an order was

not appealable before final judgment. S ee , Note, “ R ecen t

D ev e lo p m e n ts : A p p ea la b ility o f D is tr ic t C ou rt O rd ers D is

a p p rov in g P ro p o se d S ettlem en ts in S h a reh o ld ers D ep r iv a -

t iv e S u its,” 32 Yand. L.E. 985, 998-1001 (1979). C on tra ,

N orm a n v. M c K e e , 431 F.2d 769, 772-74 (9th Cir. 1970) cert,

denied , I S I v. M e y ers , 401 U.S. 912, 91 S.Ct. 879, 27 L.Ed.2d

811 (1971).

V.

We think this Title VII interlocutory appeal should be

dismissed. Our review of this pretrial order has halted the

litigation for over two years pending review of the district

court’s exercise of discretion. Given this disruption and

the difficult burden on appeal of demonstrating an abuse

of discretion, plaintiffs have identified no consequence re

quiring appellate review before final judgment. We per

ceive none. Instead, we think our review is best left to

follow final judgment.

Under the F lin n analysis, the named parties may present

a proposed decree to the district court in any form and at

any stage in the proceedings. If one decree is refused an

other may be proposed. At any time the district court can

reconsider its refusal to enter a decree. S ee C oh en v. B e n e

ficial In d u stria l L oa n C o rp o ra tio n , 337 U.S. at 547, 69 S.Ct.

1221.

When a district court objects to the terms of a decree,

alternative provisions can be presented, and perhaps a dis

approved decree may be entered with further development

of the record. If the district court refuses a decree because

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

it is presented too early in the litigation, it may be later

approved, perhaps following a decisive vote by class mem

bers. Whatever the district court’s reasons for refusing a

decree, appeals of right from those refusals would encour

age an endless string of appeals and destroy the district

court’s supervision of the action as contemplated by Fed.R.

Civ.Proc. 23(e).