Defender Association of Philadelphia v. Pennsylvania Brief for Appellants and Opinion of Court

Public Court Documents

August 8, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Defender Association of Philadelphia v. Pennsylvania Brief for Appellants and Opinion of Court, 1969. 9b1b422c-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11169542-a8db-463f-aa27-6f3dd323be4b/defender-association-of-philadelphia-v-pennsylvania-brief-for-appellants-and-opinion-of-court. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

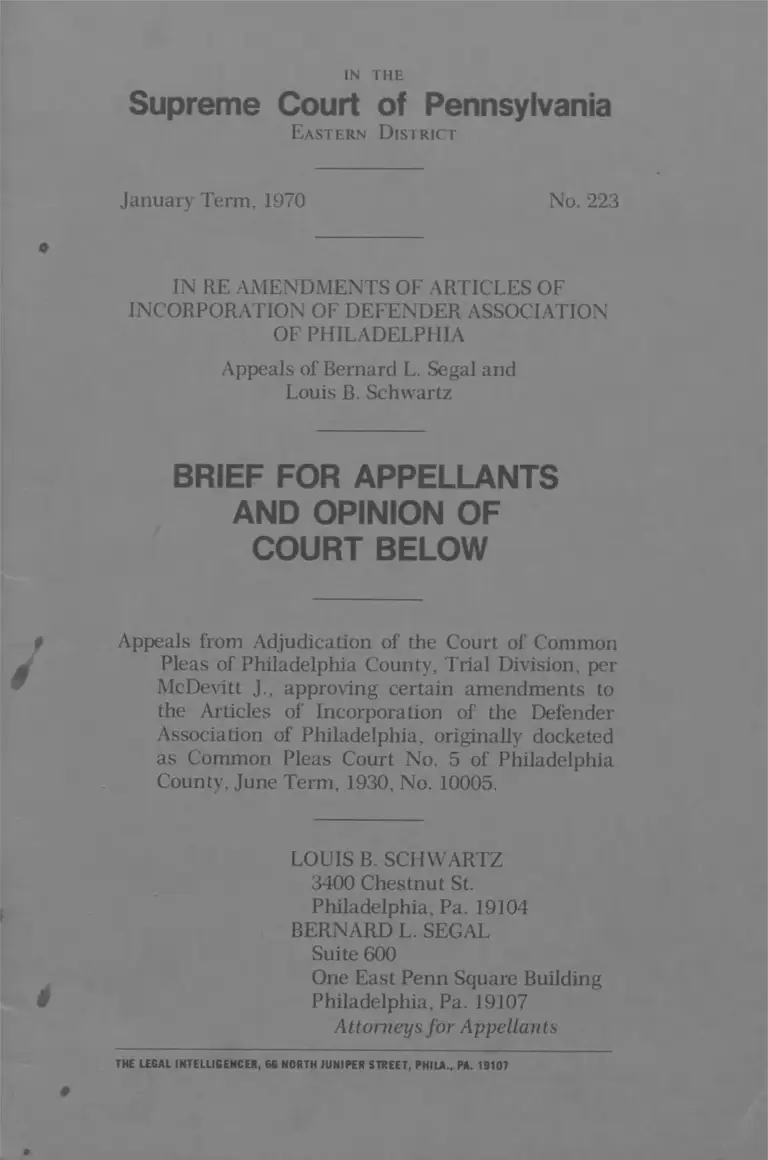

IN THE

Supreme Court of Pennsylvania

Eastern D istrict

January Term, 1970 No. 223

IN RE AMENDMENTS OF ARTICLES OF

INCORPORATION OF DEFENDER ASSOCIATION

OF PHILADELPHIA

Appeals of Bernard L. Segal and

Louis B. Schwartz

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

AND OPINION OF

COURT BELOW

Appeals from Adjudication of the Court of Common

Pleas of Philadelphia County, Trial Division, per

McDevitt J., approving certain amendments to

the Articles of Incorporation of the Defender

Association of Philadelphia, originally docketed

as Common Pleas Court No. 5 of Philadelphia

County, June Term, 1930, No. 10005.

LOUIS B. SCHWARTZ

3400 Chestnut St.

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

BERNARD L. SEGAL

Suite 600

One East Penn Square Building

& Philadelphia, Pa. 19107

Attorneys fo r Appellants

THE LEGAL INTELLIGENCER, 6G NORTH JUNIPER STREET, PHILA., PA. 19107

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Jurisdictional Statement ............................................ 1

Statement of Questions Involved............................... 2

History of the C a s e ....................................................... 3

Summary of Argument .............................................. 6

Argument ....................................................................... 9

The Central Is s u e ................................................. 9

I. As a Matter of Law, 50% Plus Influence

in the Board of Directors is Clearly

Domination by City H a ll ........................ 10

II. State and Federal Constitutions Forbid

a “Partnership” between Prosecuting Au

thorities and Counsel for the Indigent

Accused ..................................................... 11

A. The Controlling C a se s ...................... 11

B. A Manifest conflict of interest exists

where the Mayor, who will appoint

the City’s Members on the Defender

Board. Also appoints the Commis

sioner of Police and the City solic

itor ....................................................... 15

C. The conflict of interest that exists

by virtue of the Mayor’s power to

appoint the City Solicitor and also

the City’s members on the Defender

Board is further compounded by the

appointment to the Defender Board

of the City Solicitor h im self............. 18

D. The Analogy with City Hall “partner

ships” in Commercial and Develop

ment Enterprises is Wholly Inap

propriate .............................................. 19

l

TABLE OF CONTENTS— (Continued)

Page

III. “A Construction Which Is Clearly Con

stitutional is to be Preferred to One That

Raises Grave Constitutional Questions” 19

IV. When Independence of Counsel or Con

flict of Interest is in Question, It is the

Possibility, not the Actuality, of Preju

dice that is Determinative...................... 21

A. The Applicable T e s t .......................... 21

B. Political Control of Defense of the

Poor is Not a Speculative Claim but

is Based in Part on the Success of

City Hall in Forcing the Resignation

of the Acting Chief Defender En

tirely for Political M otives............... 27

V. Constitutionally Mandated Defense

Services Must Provide the Appearance

as Well as the Reality of Independence . 29

VI. Arrangements Which Exert a “Chilling

Effect” on the Exercise of Constitutional

Rights Must be Condemned on Constitu

tional and Public Interest Grounds . . . . 29

VII. “Command Influence”, Which is Barred

in Military Prosecutions, Must A Fortiori

be Excluded from Prosecution in Civil

ian Courts ................................................... 30

VIII. Professional Ethics and the Constitution

Would Demand Full Disclosure to

Clients of the Compromising “Partner

ship” with City Hall, and Intelligent

Consent by the Client. It Would be Im

practicable to Operate a Defender Or

ganization on that B a s is ........................... 32

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS— (Continued)

Page

IX. The Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corpora

tion Law; Charter Amendments Must be

“Lawful,” “Beneficial” and “Not In

jurious” ..................................................... 34

X. In Defining the Public Interest, the

Court Should Accord Great Weight to

Recent Authoritative Declarations of

Appropriate Standards for Organized

Defender Associations ............................. 36

XI. The Scope of Review on Appeal in

Equity Cases is Very Broad; it Should

Especially be so Here Where the Or

ganization of Criminal Justice is at

Stake .......................................................... 40

XII. Implications of this Case for Political

Control of Private Schools, Public Tele

vision, Welfare Payments, and Other

State Supported Operations.................... 42

Conclusion ..................................................................... 46

Adjudication ................................................................ 48

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases:

Anders v. California, 386 U.S. 738 (1 9 6 7 )........... 12, 13

Chambers v. Chambers, 406 Pa. 50, 56 (1962) . . . . 41

Commonwealth v. Grucella, 214 Pa. Superior Ct.

716 (1 9 6 9 ).............................................................. 23

Commonwealth v. Stotland, 214 Pa. Superior Ct.

35 (1969) .............................................................. 16

Commonwealth v. Wakeley, 433 Pa. 159 (1969) . . . 23

Commonwealth ex rel. Dermendzin v. Myers, 397

Pa. 607 (1959) ..................................................... 19

Cases: Page

Commonwealth ex rel. Gallagher v. Rundle, 423

Pa. 356, 223 A.2d 736, 737 (1 9 6 6 ) .................... 11

Commonwealth ex rel. Lyons v. Day, 177 Pa. Su

perior Ct. 392 (1 9 5 5 ) .......................................... 19

Commonwealth ex rel. Washington v. Maroney,

427 Pa. 599 (1 9 6 7 ) .............................................. 21

Commonwealth ex rel. Whitling v. Russell, 406

Pa. 45, 176 A.2d 641 (1 9 6 2 ) ........................ 22,23

Crooker v. California, 357 U.S. 433 (1 9 5 8 )............. 26

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 487 (1965) . . 29

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1 9 6 3 )............. 12

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335

(1963) .................................................... 1 2 ,24 ,26 ,42

Girsh Trust, 410 Pa. 455, 467 (1 9 6 3 ) ........................ 41

Glasser v. United States, 315 U.S. 60 (1 9 4 2 )........... 24

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1 9 5 6 ) ...................... 12

Hamilton v. Alabama, 368 U.S. at page 5 5 ............. 24

Idell v. Falcone, 427 Pa. 472, 474 (1 9 6 7 ) ............... 41

Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1 9 3 8 ).................... 15

McKenna v. Ellis, 280 F.2d 592 (5th Cir. 1961) .24, 25

Middleburg v. Middleburg, 427 Pa. 114, 233 A.2d

899 (1967) ............................................................ 37

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1 9 6 6 )............... 26

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1 9 6 3 ).............. 29

Nottingham Fire Company Charter, 394 Pa. 631,

632 (1959) ............................................................ 40

O’Callahan v. Parker, 89 S.Ct. 1683 (1 9 6 9 ).............. 32

Rapp v. Van Dusen, 350 F.2d 806, 812 (3d Cir.

1965) 29

St. John C.G.C. Church v. Elko, 436 Pa. 243,254 . . 41

iv

TABLE OF CITATIONS— (Continued)

Cases: Page

Screws v. United States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945) . . . . 20

Seifert v. Dumatic Industries, 413 Pa. 395, 197

A.2d 454 (1964) ................................................... 37

Shapiro v. Thompson, 89 S.Ct. 1322, 1329 (1969) . 45

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1 9 6 3 ).................. 45

Snyder’s Case, 301 Pa. 276, 152 Atl. 33 (1930) . . . . 29

Tremont Township School Dist. v. Western Coal

Co., 364 Pa. 591 (1 9 5 0 ) ...................................... 19

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1 9 2 7 )............. 13, 14, 25

U.S. v. Berry, CM 414955, June 7, 1968 .................. 30

United States v. McLaughlin, JALS Pamphlet

27-69-1, p. 4 (December 13, 1 9 6 8 ).................... 30

United States ex rel. Ried v. Richmond, 277 F.2d

702 (2d Cir. 1 9 6 0 ) ...........................................25,26

United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41, 45 (1952) . . 20

Statutes:

Investment Company Act, 15 U.S.C.A.

§80a-2(a) (9) 11

Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corporation Law, 15 Purd.

P.S.A. §7707 ............................................ 34 ,35 ,36

Public Broadcasting Act of 1967, P.L. 90-129

47 U.S.C.A. §396(a) (6) ...................................... 44

Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, §2,

15 U.S.C.A. §79 ................................................... 11

Statutory Construction Act §52(3), 46 Purd. P.S.A.

§552 19

Uniform Code of Military Justice, Article 3 7 ........... 30

Other Authorities:

A.B.A. Project on Minimum Standards for Criminal

Justice, Standards Relating to Providing De

fense Services, §1.4 (1 9 6 7 ).............................27, 37

v

TABLE OF CITATIONS—(Continued)

Cases: Page

A.B.A. Special Committee on Evaluation of Ethical

Standards, Code of Professional Responsibility

(Preliminary Draft 1 9 6 9 )...............................32, 33

A.B.A. Standing Committee on Ethics and Pro

fessional Responsibility, Informal Opinion

No. 114 (7/24/69)................................................ 14

TABLE OF CITATIONS— (Continued)

Berdahl, British Universities and the State (U.

Cal. Press 1 9 5 9 ) .............................................. 42, 43

Carnegie Foundation, Public Television: A Program

for Action, Bantam ed. 1967, p. 37 ............. 43, 44

5 Cr. L. Rep. 1030, May 21, 1969 ............................... 12

Dimrock, The Public Defender: A Step Towards

a Police State, 42 ABAJ 219 (1 9 5 6 ).................. 40

Hansen, Judicial Functions for the Commander,

• 41 Mil. L. Rev. 1 (1 9 6 8 ) ...................................... 30

2 Loss, Securities Regulation (1 9 6 1 )........................ 11

Note, Another Look at Unconstitutional Conditions,

117 U. Pa. L. Rev. 144 (1 9 6 9 ) ......................... 45

O’Brien, Implementing the Right to Counsel in

New Jersey— A Proposed Defender System,

20 Rutgers L. Rev. 789, 818 (1 9 6 6 ) ................... 40

2P.L.E. §442(1957)

§339 41

§438 41

§442 41

Silverstein, Defense of the Poor, American Bar

Foundation (1965) ............................................... 40

Somer, Who’s “In Control”?, 21 Business Lawyer

559 (1966) ............................................................ 11

Williston, History of the Law of Business Corpo

rations Before 1860, 2 Harv. L. Rev. 105, 110

(1888) ..................................................................... 35

Zeiter, Foreword to Title 15, Purdon’s Pa. Statutes,

p. 72 ....................................................................... 35

vi

Jurisdictional Statement 1

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

The jurisdiction of this Court to hear this appeal

arises from the Act of June 24, 1895, P. L. 212 §7.4 as

amended by the Act of August 14, 1963, P.L. 819, §2,

and as amended by the Act of June 30, 1967, P.L. — ,

No. 42, §1, 17P.S. 191.4.

STATEMENT OF QUESTIONS INVOLVED

1. Are poor people’s Constitutional rights to

independent defense counsel, free of conflict of in

terests, violated by an arrangement which gives the

Mayor of Philadelphia and his law enforcement asso

ciates more than 50% control of the governing board

of the Defender Association?

(Answered in the negative by the Court below.)

2. Under the Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corpora

tion Law, can an Amendment to the Charter of the

Defender Association of Philadelphia be found “law

ful,” “beneficial” and “not injurious” when its effect is

to convert an independent legal defense into a defense

dominated by “City Hall.”

(Answered in the affirm ative by the Court below.)

3. To pass on the constitutionality and pro

priety of a shift from an independent defense agency

to a defense agency dominated by political and law

enforcement authorities, must the judicial system

wait for piecemeal retroactive attacks on convic

tion by habeas corpus and other post-conviction pro

ceedings, rather than determine whether the struc

ture of the proposed Defender organization involves

inherently impermissible conflicts of interest?

(Answered in the affirm ative by the Court below.)

4. Did not the Court below manifestly err in

failing to require, at the least, that the City’s repre

sentation on the Defender Association Board be re

stricted to the minimum necessary to safeguard the

City’s fiscal interests in view of the uncontradicted

testimony, some of it from the City’s own witnesses,

that the reorganization gave the City more control

than was warranted by any legitimate interest of the

City?

(Answered in the negative by the Court below.)

2 Statement o f Questions Involved

History o f the Case

HISTORY OF THE CASE

3

Under circumstances more fully described

below, the Defender Association of Philadelphia, a

Pennsylvania non-profit corporation engaged in de

fending indigent persons accused of crimes, filed a

petition in the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia

County seeking to amend its charter and give con

trol of 50% of the Defender Association Board to the

City. The amendment was to effectuate an agreement

between the Association and the City under which

the City would advance the constitutionally required

funds for defense of the indigent upon condition that

City authorities should gain one-half control of the

Board of Directors. Objections were filed by appel

lants and others who were former members of the

Board of the Defender Association and dues-paying

members of the Association. Judge John J. McDevitt,

3d, of the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia

County, held a hearing, and approved the amendment

in an adjudication filed August 8, 1969. The present

appeal followed.

The hearings in the court below established that

the Defender Association of Philadelphia has for

thirty-five years provided defense services for in

digent persons accused of crimes. It acquired a

national reputation and was properly character

ized in testimony in this case as a “model” in the field.

(R. 134-136.) It was controlled by a Board of Direc

tors numbering 50, elected by the membership and

representing a broad spectrum of public-spirited

citizens. Its financing came from the United Fund,

membership dues, and occasional contributions. As

the demand for services expanded, under the impact

of Gideon v. W ainwright, these sources of financing

became inadequate. The City of Philadelphia began

4

to supplement its income. Funds also came from the

Ford Foundation and from the Poverty Program

of the Federal Government. These latter sources of

support dwindled by the beginning of 1969. (R. 65-70.)

The City saw the necessity of increasing its contri

bution to the level of $1,250,000. (R. 76.) City author

ities determined, under these circumstances, to

assume total control of the Defender operation, and

introduced a bill in Council to create a Public De

fender, to be appointed by the Mayor. (R. 587.) The

Defender Association “fought back”, not to preserve

itself or any particular form of organized defense

of the indigent, but to protect the principle of inde

pendence of defense counsel from prosecution-linked

domination.

There resulted a “compromise”, embodied in a

contract between the City and the Defender Associa

tion. The compromise envisioned a “partnership” in

control of the defense. City Hall would designate 10

directors. The Defender Association would desig

nate 10. These 20 would designate an additional 10.

(R. 59.) On its face, this arrangement gives City Hall

50% control of the Defender Association. In prac

tice, it would give City Hall total domination, owing

to the likelihood that highly-motivated political

appointees would attend and vote en bloc at all crit

ical points, especially in the selection of the Chief

Defender and in establishing personnel policy. Prac

tical domination would also be assured by the normal

division of opinion among “independent” directors

combined with the expectable political and economic

links to City Hall of many directors having no overt

connection with the political authorities.

Testimony in this case established City Hall’s

purpose and power to dominate, through the force-

out of the then Defender for political reasons, which

History o f the Case

History o f the Case 5

was made a condition of negotiations between the

City and the Defender Association, and through the

course of negotiations in which even the minimal

safeguards in the contract were extracted from a

reluctant City administration.

Uncontradicted testimony in this case, including

testimony of the petitioners’ own witnesses, estab

lished that the degree of control allotted to the City

exceeds any legitimate interest the City could have

in the premises. (R. 38-65, 145-147, 227-231). Uncon

tradicted testimony established that the City’s legiti

mate interests could be fully protected by contract

stipulations regarding the service to be performed,

audits and other purely fiscal supervision, and con

tinuance of the policy already firmly established of

“goldfish-bowl” operation with a standing invitation

to any interested official to attend directors’ meet

ings. Uncontradicted testimony established that full

information about the Defender operation has al

ways been made available, and that no City official

had ever claimed otherwise. (R. 341.)

The amendments to the Defender Association

charter, the subject of the present appeal, were de

signed to carry out the contract executed by the

Association under the gun of the City’s threat to cut

off funds completely. Approval by the membership

of the Association was by a close vote of 19-16. The

tenuousness of the “independent” position in the pro

posed organization is exposed by an analysis of the

amended articles: virtually every feature of the or

ganization and operation of the “new” Defender Asso

ciation, including its contract with -the City, could

be altered or abandoned without the concurrence

of a single director representing the Association.

The only power unequivocally remaining in the

Association’s directors is the power to fix the annual

dues of members.

6 Summary o f Argument

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The Constitutional right to effective assistance

of counsel requires that poor defendants have lawyers

about whom there can be no question of undivided

loyalty. No client who could afford to retain his own

lawyer would think of hiring one who was under the

control of, or substantially linked to, the police or the

prosecutor; it is a denial of equal protection and due

process of law to force such lawyers upon the indigent.

The Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corporation Law,

15 P.S. §7707 imposes three independent require

ments for amendments to non-profit charters; the

amendments must be “lawful,” “beneficial,” and

“not injurious to the community.” None of these

requirements is met here. The amendment, depriving

the poor of independent counsel, is unlawful and

unconstitutional, as shown above, because it denies

effective assistance of counsel, equal protection, and

due process. The reorganization of the Defender

Association, far from being a “beneficial” change, is

detrimental, inasmuch as it impairs the former inde

pendence of the Defender Association. The amend

ment is “injurious to the community” for the fore

going reasons and also because it undermines confi

dence in the system of justice, especially by the poor

and minority groups, thus enhancing the probabilities

of resort to violence rather than law. The fact that

the Defender Association secured City financial

support by selling its independence does not make up

for this “injury.” The City could not constitutionally

deny adequate funds for defense. Its promise to do

what it was bound, in any event, to do is no legal

consideration for giving up independence of defense

counsel. However coerced the Defender Association

Summary o f Argument 7

felt itself to be, the Courts are not bound to accept

and sanction such an illegal and bad bargain.

It is well settled, contrary to the decision below,

that the constitutional right to counsel free of con

flict of interest is not to be tested by a showing of

actual prejudice (i.e., on retrospective review of

actual trials), but by appraising the potential for

something less than zealous protection of defendant’s

rights. Middleburg v. Middleburg, 427 Pa. 114 (1967);

Com m onwealth ex rel. Whitling v. Russell, 406 Pa.

45 (1962); Gideon v. W ainwnght, 372 U.S. 335

(1963); Glasser v. U.S., 315 U.S. 60 (1942); McKenna

v. Ellis, 280 F.2d 592 (5th Cir. 1961). Cf. P. 63 (opinion

of the court below). Moreover, the Non-Profit Corpo

ration Law explicitly requires the courts to appraise

the future effect of proposed charter amendments.

Accordingly, it was fundamental error for the Court

below to dismiss as “speculative” all evidence and

demonstration by the Objectors that the reorganiza

tion was fraught with peril to the independence and

zeal of defense counsel, p. 63 (opinion of the court

below).

The proposed reorganization of the Defender

Association is unlawful and injurious for the addi

tional reason that it violates the American Bar Asso

ciation’s Code of Professional Responsibility and

Standards for Providing Defense Services. These

inveigh against “diluted” or “divided” loyalty, or

“political pressures,” and demand that defense of the

indigent be “free from political influence”— totally

free, not 50% free.

The City’s legitimate fiscal interests can be fully

safeguarded without domination of the Defender

Board, through audits, standing invitations (as here

tofore) to City officials to attend all meetings, in

spect books, and the like. If deemed appropriate, two

or three City officials might, as in the past, serve on

8 Summary o f Argument

the Board of Directors without City domination of

the Board. Accordingly, the crucial finding of fact by

the court below, No. 19, that “No feasible alternative

to the proposed system has been shown,” is absolutely

contrary to the evidence, (p. 55). If this Supreme

Court reverses and remands with instructions to con

fine the City’s representation to the minimum re

quired to safeguard the City’s fiscal interests, no

problem of feasibility whatsoever will be encountered.

Finding No. 19 really translates into a conclusion that

“The City won’t pay unless it has its way.” We believe

that the rule of law and respect for the judiciary

still survive in this Commonwealth; if the Court de

fines the Constitutional obligation, the City will pay.

ARGUMENT

Argument 9

The Central Issue.

The central issue posed by this litigation is

whether the government, which is constitutionally

required to finance defense of the indigent, shall also

m anage the defense or exercise large influence over

the defense.

The issue is not whether it would be beneficial

for the Defender Association to have the $1,250,000

which the City has offered. Of course it would be

beneficial. Eut no Court has authority or informa

tion enabling it to review appropriations. It does

not know whether $1,250,000 is too much or too little.

It certainly will have no power in the future to say

whether amounts annually appropriated by the City

are sufficient to make it a good or bad bargain for

the Defender Association to sell its independence.

The issue is not “public” vs. “private” defenders.

The Defender Association has been and certainly will

continue to be a “public” defender in the sense that

private interest and profit considerations are totally

excluded, all operations are fully exposed to public

scrutiny, and public accountability in the form of

audits and inspections is unquestioned. The issue is

how public defense is to be organized in Philadelphia;

specifically whether it is “beneficial” to change from

a fully independent board, insulating the defense from

City Hall and prosecution-linked influences, to a

board dominated by these latter powers.

There is in this case no attack upon or incon

sistency with the “public defender” provisions o f state

law. Appellants do not argue that every county

must imitate Philadelphia’s distinctive and experi

enced “voluntary” defender plan. Public defenders

10 Argument

may and should be established outside the metropoli

tan areas where no effectively financed defense has

existed. This Court’s decision in the present case

will affect them (and countless public defender organ

izations to be established throughout the country)

only insofar as it indicates the necessity and desir

ability of some measures to protect defense opera

tions from compromising, injurious and unconstitu

tional links with governing and prosecuting powers.

It is significant in this connection that the present

proposals for Philadelphia are unique in subjecting

the appointment and operation of the Defender to a

Mayor who also appoints the Police Commissioner and

the City Solicitor, the latter a prosecutor of certain

categories of criminal cases. In other counties, the

County Commissioners who designate the public de

fender have no such direct links with police and

prosecution. Public defenders elsewhere are insulated

in various ways, e.g., by boards of trustees.

I. As a Matter of Law, 50% Plus Influence in the

Board of Directors is Clearly Domination by

City Hall.

The subtle channels of political control, combined

with the vast economic influence exercised by the

government through its tax, purchasing, and regula

tory powers, present an extraordinary threat to the

independence of the Defender Association. The 50%

overt influence of the City that is spelled out in the

constitution of the Board of Directors is only that

part of the iceberg that shows above the water. Below

is the more dangerous bulk of the navigation hazard.

In the world of business regulation, no one doubts the

efficacy of “control” achieved with far less than 50%

ownership of a business. Thus 10% ownership of the

Argument 11

voting securities of a corporation is presumptively

control under the Public Utility Holding Company

Act of 1935, §2. 15 USCA §79b(a)(8). The Invest

ment Company Act adopts the figure 25%. 15 USCA

§80a-2(a)(9). See generally, 2 Loss, Securities Reg

ulation (1961) 770 (2d ed. 1961).

“It has been generally recognized since long

prior to 1933 that practical control of a corporation

does not require ownership of 51% of its voting

securities— or anything like that amount. We

have already noticed in the opening chapter the

rarity of control by majority ownership so far

as the country’s largest corporations are con

cerned, and the frequency of control by manage

ment with little or no voting power.”

See also Sommer, W ho’s “In Control’’?, 21 Business

Lawyer 559 (1966).

II. State and Federal Constitutions Forbid a

“ Partnership” between Prosecuting Author

ities and Counsel for the Indigent Accused.

A. The Controlling Cases

The Constitutional right to effective assistance

of counsel will be violated under the proposed

“partnership” between City Hall and independent

directors. The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania has

stated quite clearly, “It is unchallenged that the

Sixth Amendment guarantee of effective assistance

requires the service of a lawyer who is not obligated

to serve conflicting interests at the same time.

Comm, ex rel. Gallagher v. Rundle, 423 Pa. 356,

(1966). At the recent National Defender Conference,

jointly sponsored by the United States Department

of Justice, the American Bar Association, and the

12 Argument

National Defender Project of the National Legal Aid

and Defender Association, Attorney General John N.

Mitchell said:

“There is one point in which we all agree— the

prosperous, the educated, and the experienced

criminal defendant should not have a substantial

advantage over the poor, the illiterate, and the

novice”, (reported in 5 Cr. L. Rep. 1030, May

21, 1969).

It is obvious that no one who could afford an inde

pendent attorney would take one who was in “partner

ship” with the government that was prosecuting him.

Numerous decisions of the Supreme Court of the

United States establish that the poor are not to be

fobbed off with a second-class defense; they are en

titled to equality of defense. This means equality as

respects independence as well as equality in other

respects, regardless of demonstrated “prejudice” from

lack of counsel,1 counsel on appeal regardless of

appellate court’s opinion that it would not be “help

ful”,2 and provision of a transcript on appeal.3 The

strict requirement of undivided loyalty to the client

is demonstrated by Anders v. California, 386 U.S.

738 (1967), where the Supreme Court invalidated a

conviction because appeal counsel appointed for the

indigent defendant was allowed to withdraw after

filing a letter to the effect that his client’s appeal had

"no merit.” The California courts had refused to ap

point another attorney who would present the client’s

position as an active advocate. Mr. Justice Clark’s

opinion declared that this refusal “lacks that equality

that is required by the Fourteenth Amendment.” The

1. Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963).

2. Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 (1963).

3. Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956).

Argument 13

case is especially notable and apt in the present con

nection because the Supreme Court rejected argu

ments based on reliance upon the professional integ

rity of counsel. See dissenting opinion, 386 U.S. at 747:

“I cannot believe that lawyers appointed to

represent indigents are so likely to be lacking in

diligence, competence, or professional honesty.

Certainly there was no suggestion in the present

case that the petitioner’s counsel was either in

competent or unethical.”

The high probability that appointed counsel would

behave honorably and competently, and that his “no

merit” letter could be trusted was treated as an

inadequate substitute for uncompromising advocacy

such as a fee-paying client would get.

The Anders holding is all the more striking when

viewed against the background of the duty which the

California courts laid upon them selves to review the

transcript and independently confirm that only friv

olous issues were raised and that counsel’s “no merit”

letter was correct. Thus neither the assumed pro

fessional reliability of lawyers nor the duty of courts

to prevent prejudice arising from lawyers’ neglect

saves a conviction where counsel was not manifestly

and unequivocally on the side of his client.

In Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510 (1927), dis

cussed in further detail below, the Supreme Court

invalidated a conviction mainly because the village

mayor who tried the case was compensated from

“costs” imposed in case of conviction. But the Court

also saw another important element of unconstitu

tional impropriety in the fact that the village, as

distinct from the mayor personally, had a financial

stake in the proceedings. The Ohio statutes provided

that half the fines in liquor cases would be payable to

14 Argument

the villages for expenses of enforcing the liquor law.

The Court took cognizance of the fact that the mayor

“is charged with the business of looking after the

finances of the village” so that he would be indirectly

interested in imposing higher fines:

With his interest, as mayor, in the financial con

dition of the village, and his responsibility

therefore, might not a defendant with reason say

that he feared he could not get a fair trial . . .

from one who would have so strong a motive to

help his village by conviction and a heavy fine?

(273 U.S. at p. 533).

The relevance of this potential financial bias in

the present case is clear. Many decisions by a public-

defender entail expenses for the community, notably,

refusal to plead guilty, demand for jury trial, and zeal

ous prosecution of appeals. Conscientious work as

defense counsel may expose the need for greater

expenditures for prosecution, courtroom facilities,

probation service and jails. It defies belief that City

representatives on the Board of the Defender Associa

tion would ignore budgetary implications of decisions

of this sort. And even if, “being men of the highest

honor and the greatest self-sacrifice”, they did manage

to ignore it, the question remains whether defendants

and the community would believe it. R. 412, 543-546;

567. Recent events have highlighted the vital neces

sity for the centers of justice to avoid the appearance

as well as the substance of evil. See the advisory

opinion of the American Bar Association’s Committee

on Professional Ethics in the matter of Justice Fortas,

1969.4

4. A.B.A. Standing Committee on Ethics and Profes

sional Responsibility, Informal Opinion No. 1114 (7/24/69.).

Argument 15

It is not material that the present case concerns

defense counsel rather than judge. Johnson v. Zerbst,

304 U.S. 458 (1938), the landmark case establishing

that lack of counsel renders a conviction subject to

collateral attack, treated absence of counsel as “fail

ure to complete the court” resulting in loss of jurisdic

tion. And, from a practical point of view, a defendant

needs a lawyer whom he can trust absolutely even

more than a completely impartial judge. Intimate

confidentiality is a feature of the client-attorney

relationship; it is not so of the judge-defendant re

lationship. The zealous defense lawyer can often

manage to avoid subjecting his client to trial before

an unsympathetic judge, be watchful against expres

sions of bias from the bench, and seek remedies by

appeal.

B. A Manifest Conflict o f Interest Exists Where

the Mayor, W ho Will Appoint the City’s Mem

bers o f the Defender Board, Also Appoints the

Com m issioner o f Police and the City Solicitor.

The intolerable effect of linking Defender ser

vices to City Hall is glaringly apparent when it is

recognized that the Mayor will appoint the princi

pal antagonists in the field of law enforcement

and in the defense of indigent persons accused of

crime at one and the same time.

Under the amendments to the Defender Associa

tion charter the Mayor will appoint all of the City’s

representatives to the Defender Board, and thereby

influence, if not control, the appointment of the Chief

Defender. At the same time, however, the Mayor

under the Philadelphia Home Rule Charter appoints,

through the Managing Director, the Commissioner of

Police. Equally disturbing is the fact that the Mayor

16 Argument

also appoints the City Solicitor, who is the prosecu

tion lawyer for violations of numerous criminal-type

ordinances, such as violations of the Mayor’s Procla

mation,5 and various anti-gun, knife and weapons

ordinances.

The amendments approved by the Court below in

simplest form allow the Mayor of Philadelphia to

appoint the lawyers on both sides of litigation involv

ing indigents accused of offenses, as well as the

principal enforcement officer, too.

The total unacceptability of this arrangement

is fully exposed by Police Commissioner Rizzo’s state

ment, reported on page 1 of the Philadelphia Bulletin

for June 10, 1969. Speaking before City Council’s

Committee on Public Safety, he declared his inten

tion to stop police payroll deductions for the benefit

of the United Fund because the United Fund sup

ports the Legal Aid Society. Organizations that

“fight the Police Department . . . won’t get a

penny,” he stated. On June 16, 1969, the Board of

Governors of the Philadelphia Bar Association

adopted the following resolution in response to this

threat to independent, loyal legal representation of

the poor:

“WHEREAS, the Philadelphia Commissioner

of Police has publicly charged the Legal Aid

Society of Philadelphia with harassing the police

force and processing complaints against police

officers, a charge which investigation indicates to

be unfounded in fact, and

WHEREAS, the Board of Governors deems

such charge an attack upon the freedom of the

lawyer to represent his client,

5. See Commonwealth v. Stotland, 214 Pa. Superior Ct.

35 (1969).

Argument 17

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED,

That the Philadelphia Bar Association through

its elected Board of Governors supports and en

courages every lawyer in the exercise of his pro

fessional responsibility to represent any client

or group of clients in regard to any just cause of

action no matter how unpopular; and,

FURTHER RESOLVED, That the Philadel

phia Bar Association deplores any action or

statement by any government official who at

tempts to discourage or interfere with the opera

tion or activities of a non-profit corporation

providing legal services to the community merely

because the lawyers employed thereby, acting in

good faith and within the confines of ethical con

duct, zealously represent their clients in matters

deemed embarrassing to, or which involve claims

against, a government entity or individuals

employed thereby.”

The continuing disposition of police, prosecution,

and political authorities to exert their influence even

upon the judiciary is attested by the events of late

August, 1969, as reported in the Philadelphia Bulletin,

August 27, p. 42, and August 29, p. 1. Under a head

line, “Rizzo Sets Up Meeting with Judge Carroll,”

the report describes a meeting in the Mayor’s office,

attended by the District Attorney, the Commissioner

of Police, and several judges, at which the judges

were pressed to change their sentencing policies.

This meeting, too, evoked protest from the Philadel

phia Bar Association. These events are not in the

record below, since they occurred after the hearing in

this case, and accordingly cannot serve as direct evi

dence for consideration by this Court. They are

mentioned here merely to illustrate by concrete

18 Argument

example the dangerous potential for interference

with the Defender Association, if City Hall presides

over the destinies of the Association.

This potential for interference was candidly

summed up by Richard A. Sprague, First Assistant

District Attorney of Philadelphia, and a witness called

by the objectors. Sprague testified from the vantage

point of 11 years in responsible positions in the Dis

trict Attorney’s office, and from nearly three years

experience prior to that as an Assistant Defender.

He declared:

. . I’m aware of the extent to which, say, the

Police Department, people from the City Ad

ministration, are interested in—from the Prose

cutor’s side, we call it the war on crime. And to

the extent that the Police, through whatever

levels of people in the Administration, could

perhaps have a say over policies by those defend

ing people we’re warring on, and there in my

opinion will be a reaching into that area an

intimidation, getting people to back off certain

action that they might otherwise take. And I

think and I feel that the people employed unfor

tunately are not always the most resolute and

if they’re aware of the powers over them, they

might not take as forthright a stand as they

otherwise would if they were completely inde

pendent.” (R. 321-322.)

C. The Conflict o f Interest that Exists by virtue

o f the Mayor’s pow er to appoint the City Solic

itor and also the City’s m em bers on the Defender

Board is further com pounded by the appoint

ment to the Defender Board o f the City Solicitor

h im self

As if to further underscore the failure of the City

to recognize the conflict of interest arising from the

Argument 19

Mayor’s influence over the appointment of the Chief

Defender through his appointment of members of the

Defender Board as well as his own power of appoint

ment over the City Solicitor, on January 29, 1970

the City Council confirmed the Mayor’s appointment

of Edward Bauer, the incumbent City Solicitor of

Philadelphia, to the Board of the Defender Associa

tion.

D. The Analogy with City Hall “partnerships”

in Com m ercial and Development Enterprises

is Wholly Inappropriate.

Testimony in this case established that the ne

gotiators thought in terms of Philadelphia Industrial

Development Corp. and other enterprises in which

the City and powerful commercial or financial groups

jointly embarked on port development or other pro

prietary projects. (R. 437-439). It is evident that these

collaborations present no Constitutional issues. No

fundamental private rights are at stake. Moreover,

there is in such partnerships a notable parity of power

that is absent in the present case where the City will

be the source of virtually all the funds.

III. “ A Construction Which Is Clearly Constitu

tional is to be Preferred to One That Raises

Grave Constitutional Questions.”

The quotation is from Com m onwealth ex rel.

Lyons v. Day, 177 Pa. Superior Ct. 392 (1955), citing

§52(3) of the Statutory Construction Act, 46 P.S.

§552. But it is hornbook law. See, for example, Com

m onwealth ex rel. Dermendzin v. Myers, 397 Pa. 607

(1959); Tremont Township School Dist. v. Western

Coal Co., 364 Pa. 591 (1950). The Supreme Court of

20 Argument

the United States follows the rule. In Screws v. United

States, 325 U.S. 91 (1945), the Supreme Court gave

the Civil Rights Act a narrow specificity not to be

found on its face, lest it be unconstitutionally vague,

saying:

If such a construction [i.e., the broader con

struction] is not necessary, it should be avoided.

This Court has consistently favored that interpre

tation of legislation which supports its constitu

tionality. . . . That reason is impelling here

so that if at all possible §20 may be allowed to

serve its great purpose— the protection of the

individual in his civil liberties.

In United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41, 45

(1952), the doctrine was summed up as follows:

“Accordingly, the phrase “lobbying activities”

in the resolution must be given the meaning

that may fairly be attributed to it, having special

regard for the principle of constitutional adju

dication which makes it decisive in the choice of

fair alternatives that one construction may raise

serious constitutional questions avoided by

another. In a long series of decisions we have

acted on this principle. In the words of Mr. Chief

Justice Taft, “ [i]t is our duty in the interpre

tation of federal statutes to reach a conclusion

which will avoid serious doubt of their constitu

tionality.” Richm ond Co. v. United States, 275

U.S. 331, 346. Again, what Congress has written,

we said through Mr. Chief Justice (then Mr.

Justice) Stone, “must be construed with an eye

to possible constitutional limitations so as to

avoid doubts as to its validity.” Lucas v. Alex

ander, 279 U.S. 573, 577. As phrased by Mr. Chief

Justice Hughes, “if a serious doubt of constitu-

Argument 21

tionality is raised, it is a cardinal principle that

this Court will first ascertain whether a con

struction of the statute is fairly possible by which

the question may be avoided.” Crowell v. Benson,

285 U.S. 22, 62, and cases cited.”

So here we ask the Court to interpret the Penn

sylvania Non-Profit Corporation Law so as to avoid

grave constitutional questions and in favor of in

dividual liberty including the right to counsel free

of conflict of interests.

IV. When Independence of Counsel or Conflict of

Interest is in Question, It is the Possibility,

not the Actuality, of Prejudice that is Deter

minative.

A. The Applicable Test.

The Court below was clearly in error in adopting

the view, which pervades all findings and discussion

in the adjudication below, that the obvious conflict of

interest in City Hall domination of the defense did not

itself vitiate the proposed reorganization. The Court

thought that apprehensions on this account were

“speculative” and premature; that possible harm to

defendants might be averted if, as former Defender

Herman I. Pollock testified, the non-City directors

“continue to fight to keep the Association indepen

dent.” R 592. The Court below was satisfied to await

the outcome of this “fight”, and to undertake the dif

ficult task of determining whether the vigor of de

fense had actually been undermined in particular

cases on habeas corpus.

But that test of actual harm is the proper rule

only when inquiring w hether an independent counsel,

fr ee o f conflict o f interest, has done his jo b with rea

sonable com petence. That is the teaching of Com mon

wealth ex rel. W ashington v. Maroney, 427 Pa. 599

22 Argument

(1967), a case which shows how difficult it is to pass

on adequacy of counsel by hindsight. An altogether

different rule applies in Pennsylvania, as elsewhere,

when the issue is conflict of interest. Com monwealth

ex rel. Whitling v. Russell, 406 Pa. 45:

If, in the representation of more than one de

fendant, a conflict of interest arises, the mere

existence of such a conflict vitiates the proceed

ing, even though no actual harm results. The

potentiality that such harm may result, rather

than that such harm did result, furnishes the

appropriate criterion. As pointed out by Judge

Montgomery in his dissenting opinion, the Supe

rior Court in Pile v. Thom pson, 62 Pa. Super.

400, well stated: . . . The rule is not intended

to be remedial of actual wrong, but preventive of

the possibility of it. (ital. in original)

* * *

One of the most important factors in a criminal

trial is the attitude of the defendant’s counsel

and often the strength of the defendant’s cause,

unfortunately, is judged and gauged by the abil

ity demonstrated by defendant’s counsel. We can

not say that counsel in the instant case was not

effective. But could he not have been more effec

tive, and more able to utilize the evidence, if he

had not been burdened by the chore of defending

two defendants whose positions were inconsistent

and at variance?

The Whitling decision serves notice that convic

tions obtained in disregard of potential conflict of

interest of defense counsel may be invalidated later

in habeas corpus proceedings, fully vindicating the

concerns of District Attorney Specter who testified

in this case against the “partnership” concept in the

Argument 23

proposed amendments to the charter of the Defender

Association. (R. 285-291, 302, 304.)

It should be of significance to this Court that the

only witnesses with prosecution experience called to

testify in the court below were called by the objectors.

All these witnesses vigorously opposed the arrange

ment approved by the court below because of their

belief that it raised substantial questions of conflict

of interest. In addition to the testimony of District

Attorney Specter, there was testimony from Richard

A. Sprague, First Assistant District Attorney who

had served as an Assistant Defender for three years

(R. 321-323); from Edmund E. DePaul, former Chief

of the Criminal Division of the United States Attor

ney’s office for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania

who had served for 11 years as a Senior Assistant

Defender (R. 412-414); and from Martin Vinikoor,

a Chief Assistant District Attorney and former

Acting Defender and First Assistant Defender (R.

343-345).

Com m onwealth v. W akeley, 433 Pa. 159 (1969),

is entirely consistent with the Whitling case and with

appellants’ position here. There the Court sustained a

conviction against defendant’s objection that his

lawyer had been assistant district attorney at the

time of defendant’s indictment. As the opinion points

out, any effect this could possibly have had on the de

fense would have been favorable to defendant; the

state was the only party that could conceivably have

been hurt by such a “switching of sides”. The opinion

also recognizes the inevitability and desirability of

individual lawyers changing roles from defense to

prosecutor and vice versa from time to time. Cf.

Com m onwealth v. Grucella, 214 Pa. Superior Ct. 716

(1969). Thus, a defense lawyer’s form er association

with the district attorney’s office is not a per se dis

24 Argument

qualification. If the defense lawyer has job prospects

in the district attorney’s office, more serious question

of conflict of interest arises, as shown in McKenna v.

Ellis, below, but the situation is still utterly distin

guishable from the present and persistent prosecution

influence on defense envisioned by the reorganization

of the Defender Association here in issue.

The very essence of Gideon v. Wainwright, 372

U.S. 335 (1963), was to make the right to counsel

absolute rather than, as theretofore, dependent on a

showing of harm from lack of counsel. Cf. Mr. Justice

Clark’s concurring opinion, 372 U.S. at 347, rejecting

any distinction between capital and non-capital cases,

and quoting from Hamilton v. A labama, 368 U.S. at

p. 55. “When one pleads guilty to a capital charge

without benefit of counsel, we do not stop to determine

whether prejudice resulted.” This is clearly evident

in the conflict of interest cases. In Glasser v. United

States, 315 U.S. 60 (1942), the Supreme Court re

versed a conspiracy conviction on the ground that the

trial judge had appointed defendant’s lawyer to repre

sent also a co-defendant where there was a potential

conflict of interest between the two clients. The re

versal was notwithstanding substantial basis for

finding that defendant (a former assistant U.S. At

torney) and his lawyer had waived objections to the

appointment. The Court’s opinion declares (at pages

75-76):

“To determine the precise degree of prejudice

sustained by Glasser . . . is at once difficult

and unnecessary. The right to have the assistance

of counsel is too fundamental and absolute to

allow courts to indulge in nice calculations as to

the amount of prejudice arising from its denial.”

(itals. supplied)

Argument 25

The Court cited for this proposition Turney v. Ohio,

273 U.S. 510 (1927), where Chief Justice Taft, speak

ing for a unanimous bench, reversed Turney’s convic

tion of a liquor offense on the ground that he was tried

before a village mayor who, under state law, was

compensated for conducting such summary trials out

of “costs” taxed against convicted defendants. This

pecuniary interest in conviction was held to disqualify

the mayor, on due process grounds, notwithstanding

the argument that men of the highest honor and

the greatest self-sacrifice could carry it on with

out danger of injustice. Every procedure which

would offer a possible temptation to the average

man . . . or which might lead him not to hold

the balance nice, clear and true between the state

and the accused denies the latter due process of

law. (273 U.S. at 532)

McKenna v. Ellis, 280 F.2d 592 (5th Cir. 1961),

reversed a conviction where the trial court had ap

pointed two young attorneys to represent defendant,

both of them candidates for jobs with the district at

torney. The court declared, at page 599:

We interpret the right to counsel as the right to

effective counsel. We interpret counsel to mean

not errorless counsel, and not judged ineffective

by hindsight, but counsel reasonably likely to

render and rendering reasonably effective

assistance. We consider undivided loyalty of

appointed counsel to client as essential to due

process.

United States ex rel. Reid v. Richmond, 277 F.2d

702 (2d Cir., 1960), which sustained the constitu

tionality of the old Connecticut public defender sys

tem, is utterly distinguishable from the present case,

26 Argument

and is in any event rendered obsolete in view of subse

quent constitutional developments. The Connecticut

Public Defender was not appointed by a prosecution-

linked mayor, but by judges. Judges had historically

appointed individual counsel to represent indigents,

and it was natural to turn to them as the appointing

power when a defender organization was to be

created. Besides, judges had always recognized, even

prior to Gideon v. Wainwright, their responsibility

to safeguard an unrepresented—and indeed even a

represented— defendant’s rights in a criminal case.

The Mayor and the Commissioner of Police of Phila

delphia have no such historic or practical responsibil

ity. To the contrary, they are properly the commun

ity’s agents for the enforcement of law.

The obsolescence of the Richm ond decision is

evident from several considerations. First, the right to

counsel has become more absolute since 1960. The

Richmond court cited and relied on Crooker v.

California, 357 U.S. 433 (1958), in holding that Reid

had no absolute right to counsel at pretrial phases of

the prosecution, e.g., when he gave a confession in re

sponse to interrogation while in police custody. The

Richmond court quoted Crooker’s declaration that de

fendant must show “prejudice” from denial of counsel

under these circumstances. But Gideon v. Wain

wright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963) and Miranda v. Arizona,

384 U.S. 436 (1966), have swept away such notions.

In the second place, since 1960 the nation and

the legal profession have begun to recognize that there

is a difference between appointing individual counsel

and appointing a public defender insofar as the role of

the judiciary is concerned. When a variety of

individual lawyers are appointed by different judges,

appointed counsel presumably has a broad clientele,

including paying clients perhaps in the civil field as

Argument 27

well as the criminal field. He is thus considerably

more independent of the appointing judge than is a

professional public defender. It is for this reason that

the ABA Minimum Standards for Criminal Justice

emphasize that the “plan” as well as individual de

fender attorneys be “subject to judicial supervision

only in the same manner and to the same extent as

are lawyers in private practice.” 6 Notably, in Con

necticut, the 1969 Public Defender legislation aban

dons the old system under which local trial judges ap

pointed a local defender. Instead, a state-wide chief

defender is appointed by a commission that is com

posed of the Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court,

the Chief Court Administrator of the State, the Chief

Judge of the Superior Court, the Chief Judge of the

Circuit Court, and two trial court judges designated

by the Chief Judge of the Circuit Court. The Com

mission also appoints local defenders and assistant

defenders upon nomination of the chief defender, and

promulgates regulations, guidelines, and standards

for administration of the defender system. The Com

mission selecting public defenders for Connecticut

is, therefore, effectively insulated not only from poli

tical patronage and links to prosecution forces, but

also from pressures of the trial judges themselves.

B. Political Control o f Defense o f the Poor is Not

a Speculative Claim but is Based in Part on the

Success o f City Hall in Forcing the Resignation

o f the Acting C h ief Defender Entirely fo r Political

Motives.

The court below, in characterizing the concern

of the objectors over political control as “specula

6. A.B.A. Project on Minimum Standards for Criminal

Justice, Standards Relating to Providing Defense Services

§1.4 (1967).

28 Argument

tive”, chose to entirely overlook the evidence pro

duced in the hearings as to the circumstances

surrounding the “resignation” of Martin Vinikoor as

Acting Chief Defender early in 1969.

The evidence established without contradiction

that the City refused to discuss with the Defender As

sociation additional appropriations so long as Vini

koor remained at the head of the Defender staff.

There was no complaint by the City that Vinikoor

lacked the qualifications for the position. To the con

trary, he was eminently well qualified with a back

ground that included substantial experience as both

an assistant district attorney and as a private criminal

defense lawyer, and as a former Secretary of the

Criminal Procedural Rules Committee of this Court.

However, Vinikoor when in private practice had

refused to support the incumbent Mayor of Philadel

phia in his campaign for re-election in November,

1967, and had, in fact, sought election to City Council

on the ticket of the opposite political party. For this

action in 1967 the City set as a condition precedent

to any negotiations with the Defender Association

for appropriations the resignation of Vinikoor as Act

ing Chief Defender. Under that pressure he resigned.

Following Vinikoor’s resignation the City con

cluded the agreement with the Association resulting

in the Charter amendments that are now before this

Court.

Despite the fact that there was no challenge

at all to these facts, which so clearly demonstrate

the way the City is prepared to pursue its political

objectives even when dealing with the organization

handling the defense of the poor, the court below

chose erroneously to characterize the objections

raised by the appellants as merely “speculative.”

Argument 29

V. Constitutionally Mandated Defense Serviees

Must Provide the Appearance as Well as the

Reality of Independence.

An important function of providing defense coun

sel is to build confidence in the fairness of the judicial

process. It is not merely that the outcome of a particu

lar case may be skewed where there is a lawyer on one

side and none on the other. It is that underprivileged

groups in the community come to view courts and law

with cynicism and hatred when the conduct of the

courtroom seems one-sided, as where there is no de

fense counsel or an “official” defense counsel. All con

victions become tainted in their eyes, even though the

outcome of many individual cases would be found on

close examination to be perfectly just.

The importance of avoiding the “appearance of

evil” is attested by cases like Rapp v. Van Dusen, 350

F.2d 806, 812 (3d Cir. 1965) (“not only actual im

partiality [of a judge], but also the appearance of de

tached impartiality”); and Snyder’s Case, 301 Pa. 276,

152 Atl. 33 (1930) (“avoiding even the appearance of

evil”).

VI. Arrangements Which Exert a '“Chilling Effect”

on the Exercise of Constitutional Rights Must

he Condemned on Constitutional and Public

Interest Grounds.

The rule against “chilling effects” has been fre

quently invoked. A striking instance is NAACP v.

Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963), where a Virginia regula

tion of the conditions of law practice was held uncon

stitutional because of the chilling effect on First

Amendment rights: “First Amendment freedoms need

breathing space to survive.” (at p. 433) And so do

Sixth Amendment rights of vigorous defense. Com

pare Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 487 (1965)

(federal injunction against threatened state prosecu-

30 Argument

tion allowed notwithstanding general rule against

such interference where rights might be vindicated by

defense to prosecution, because of “chilling effect on

free expression of prosecutions initiated and

threatened”).

VII. “ Command Influence,” Which is Barred in

Military Prosecutions, Must A Fortiori be

Excluded from Prosecution in Civilian Courts.

Stanford Shmukler, Esq., then Chairman of the

Philadelphia Bar Association Committee on Criminal

Justice, testified for the objectors in this case.

R. 364 et seq. Drawing on his experience in the Judge

Advocate Corps, he pointed to the dangers of “com

mand influence” in the sphere of military trials, where

the necessities of war and discipline might have led to

considerable tolerance of command influence, espe

cially considering that service men inevitably must

yield many of the freedoms that a civilian enjoys. To

the credit of the armed services, every effort has been

made to achieve independence for the military tribu

nals including counsel for the defendant. See Article

37 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice; U.S. v.

Berry, CM 414955, June 7, 1968, digested in Judge

Advocate Legal Service, Pamphlet 27-68-18, page 4

(“Appearance of Command Influence Raises Re

buttable Presumption” of unlawful command influ

ence despite finding of lack of prejudice); United

States v. McLaughlin, digested in JALS Pamphlet 27-

69-1, p. 4, Dec. 13, (1963) (routine command memo

assigning three out of a panel of 12 duly assigned

officers, for purposes of allocating trial duties, held

unlawful command influence); Hansen, Judicial

Functions fo r the Com mander, 41 Mil L. Rev. 1

(1968). Relevant quotations from this last source in

clude the following:

Argument 31

[p. 20] “The principal objection voiced by

witnesses during the committee hearings on the

Code concerned the power of the commander to

appoint the members of the court-martial. To

these witnesses “control is exercised by reason

of the fact the participants in the courts— the

judges, the prosecutors, and the defense coun

sel—are subject to the full command of the offi

cers who appointed them, and that their service

careers are in his hands. Accordingly, the only

way to prevent the court members from being

improperly influenced in their judicial activity

by the commander, as they saw it, was to dis

continue the commander’s power to appoint the

court, and remove him from any responsibility

in this area of military justice.

“This suggestion was not new in the his

torical development of the commander’s power

and has been consistently resisted by the military

establishment as an impracticable provision

which would hinder those responsible for the

conduct of military operations. This latter view

was accepted by Congress and recognition given

to the fact that acts which are rights in the

civilian community may constitute direct chal

lenges to the commander’s authority to success

fully accomplish his assigned mission:

Take the business of telling off the

boss, that is an inalienable right of an Amer

ican citizen. If you tell off the sergeant or

commissioned officer, that is a military of

fense. In civilian life, if you do not like your

job, you quit it. If you do not like your job in

the Army and quit, that is called desertion

in wartime and it carried very serious con

sequences. In civilian life if people decide

they do not like the working conditions and

32 Argument

walk off jointly, that is a strike. In the Army

or in the Navy, that kind of action is mutiny,

which is one of the most serious offenses.

“However, retention of the commander’s

position as a convening authority was not a com

plete vote of confidence since the remainder of

the committee’s efforts were expended in an at

tempt to provide additional safeguards against

the abuse of his power.”

Cf. O'Callahan v. Parker, 395 U.S. 258 (1969), which

denied court martial jurisdiction for a crime against a

civilian committed by a soldier on leave, pointing to

the importance of preserving maximum trial rights

of accused:

Strides have been made toward making courts-

martial less subject to the will of the executive

department which appoints, supervises and ulti

mately controls them. But from the very nature

of things, courts have more independence in

passing on the life and liberty of people than do

military tribunals. (395 U.S. at p. 263)

VIII. Professional Ethics and the Constitution

Would Demand Full Disclosure to Clients of

the Compromising “ Partnership" with City

Hall, and Intelligent Consent hy the Client.

It Would he Impracticable to Operate a De

fender Organization on that Basis.

The least that would be required of a prosecution-

linked defender organization, from the point of view

of professional ethics and constitutional law, would

be full disclosure to each client of the conflict of in

terest in City Hall’s partnership in the Defender Asso

ciation. This is clear even in civil cases. The American

Bar Association Special Committee on Evaluation of

Ethical Standards, has just published a “Code of

Argument 33

Professional Responsibility” (Preliminary Draft,

1969). Speaking of “potentially differing interests” of

multiple clients (Paras. 12 et. seq.), the committee

warns against “diluted” or “divided” loyalty, states

that “all doubts” should be resolved against repre

sentation of potentially conflicting interests, and in

sists upon the client’s being given “opportunity to

evaluate his need fo r representation free o f any po

tential conflict and to obtain other counsel i f he so

desires.” The lawyer is required to explain the “im

plications” of common representation before securing

his client’s consent, and to advise the client of “other

circumstances” that might cause the client “to ques

tion the undivided loyalty of the lawyer.” “Regardless

of the belief of a lawyer that he may properly repre

sent multiple clients, he must defer to a client who

holds the contrary belief and withdraw from repre

sentation of that client.”

Speaking of the effect on lawyers’ independence

of “desires of third persons” (Paras. 19 et seq.), the

Committee says:

A lawyer subjected to outside pressures [“often

subtle, and a lawyer must be alert to their exis

tence”] should make full disclosure of them to

his client. The Committee notes the special lia

bility to “political” pressures where the lawyer

is being paid by someone other than his client.

What is so emphasized in civil cases must a fo r

tiori be true in criminal defense, where effective as

sistance of counsel is a fundamental Constitutional

right.

It is obviously unwise and impractical to operate

a defender organization on the basis of disclosures to

and waiver by often ignorant prisoners with no effec

tive alternatives. It would take far too much time;

the process would degenerate into an ineffectual

34 Argument

formality of giving prisoners written explanations and

waiver forms; much suspicion would be generated by

the very process of seeking to allay it; and numerous

convictions would be opened to collateral attack. Such

consequences clearly preclude a finding in this case

that the proposed amendments of the Association’s

articles are and will be “lawful, beneficial, and not

injurious.”

IX. The Pennsylvania Non-Profit Corporation

Law; Charter Amendments Must he “Lawful,”

“ Beneficial” and “ Not Injurious.”

The issues posed by the Pennsylvania Non-Profit

Corporation Law, 15 P. S. §7707, are whether the

proposed amendments are “lawful,” “beneficial,” and

“not injurious to the community.” 7 This legislation

contemplates the broadest inquiry into the public

interest. The non-profit corporation has traditionally

been regarded in Pennsylvania as the private profit

corporation used to be regarded, i.e., as an instrument

for carrying out public policy in the best way.8 The

7. Section 7707 is the section applicable to this case. An

alternative procedure for amending charters of non-profit

corporations was authorized by Act 31, Laws 1969. This Act

did not take effect until September 17, 1969, long after the

hearing and judgment below. It was prospective in operation,

applying to corporations then “proposing to amend,”

“elect [ing] to proceed under this section,” and advertising

in a manner prescribed by the new section 14. A decision by

this Court that reorganization of the Defender Association in

the manner proposed would be unconstitutional, unlawful,

or injurious would, of course, be effective to preclude any

amendment of that character by whatever procedure may be

available, since it would plainly lay open to collateral attack

all convictions obtained with the participation of prosecution-

linked defense counsel.

8. Originally, in Pennsylvania as in England, all corpora

tions were regarded as public agencies carrying out particular

Argument 35

Court has the power and duty to shape and constrain

these public agencies, especially when the question

at issue is the relationship which the non-profit cor

poration will have with the City of Philadelphia—it

self an instrument of government—and especially

when the crux of the controversy has to do with the

independence of defense lawyers who are officers of

the Court.

“Beneficial” in 15 P.S. §7707 means that the pro

posal must improve matters. The legislature did not

take a neutral attitude towards corporations designed

to serve public purposes, exempt from taxation, and

subject to supervision by state officials. It required

a demonstrated need for and benefit from the found

ing of a non-profit corporation or any substantial al

teration of its structure or purposes. Thus the burden

is on the applicants to show that a structure which

gives to City Hall at least half the governing power

over indigent defense is an improvement over the

previous wholly independent Defender Association.

The requirement under 15 P.S. §7707 demands

that the proposal be “beneficial” and “not injurious to

the community.” The plain meaning of this conjunc

tion is that there is not to be a balancing of benefits

and detriments, but an absence o f injurious elements.

governmental purposes thought of as “special government” in

distinction from the general government carried out by

municipal corporations. Williston, History of the Law of Busi

ness Corporations Before 1860, 2 Harv. L. Rev. 105, 110

(1888). Chartering was by the legislature in Pennsylvania

until it vested this discretion in the Supreme Court as re

spects “non-profit” organizations. The jurisdiction was later

vested in the Court of Common Pleas, which to this day ex

ercises supervision over this branch of “special government,”

while the chartering of private profit corporations has become

a routine administrative task substantially divorced from the

notion of public responsibility. See Zeiter, Foreword to Title

15, Purdon’s Pa. Statutes, at p. 72.

36 Argument

If all that had been intended was a “net benefit ’ cri

terion— more benefit than detriment— there would

be no need for the words “and not injurious to the

community.” Therefore, it is the responsibility of

the Court to prune out of an otherwise beneficial

arrangement any elements which are "injurious to

the community,” such as dominance of defense by

prosecution-linked officials, loss of client confidence,

risk that convictions will be collaterally attacked,

and likely resentment by underprivileged segments

of the population promotive of cynicism and public

disorder.

The requirement that amendments to charters of

non-profit corporations be affirmatively beneficial is

highlighted by contrast with the provision as to ori

ginal organization of such corporations, 15 P.S.

§7702. There it is stated only that the purposes must

be “lawful and not injurious.” By contrast, the addi

tion of the word “beneficial” in §7707 indicates a high

er standard for amendments than for original in

corporation. And this makes sense since, as in the

present case, people who have united in a charitable

or other non-profit enterprise may be disunited when

it comes to a fundamental alteration of the arrange

ment. It should be altogether clear that the revised

enterprise is “beneficial” and not too remote from the

original plan. In our case the present amendments,

adopted by a close vote of 19-16, radically alter the

original enterprise, from an independent defender