Sumter v. Drummond Transcript of Record

Public Court Documents

February 23, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sumter v. Drummond Transcript of Record, 1962. 051c6960-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1119a676-d6b8-4048-b9ec-96cf834e70f2/sumter-v-drummond-transcript-of-record. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

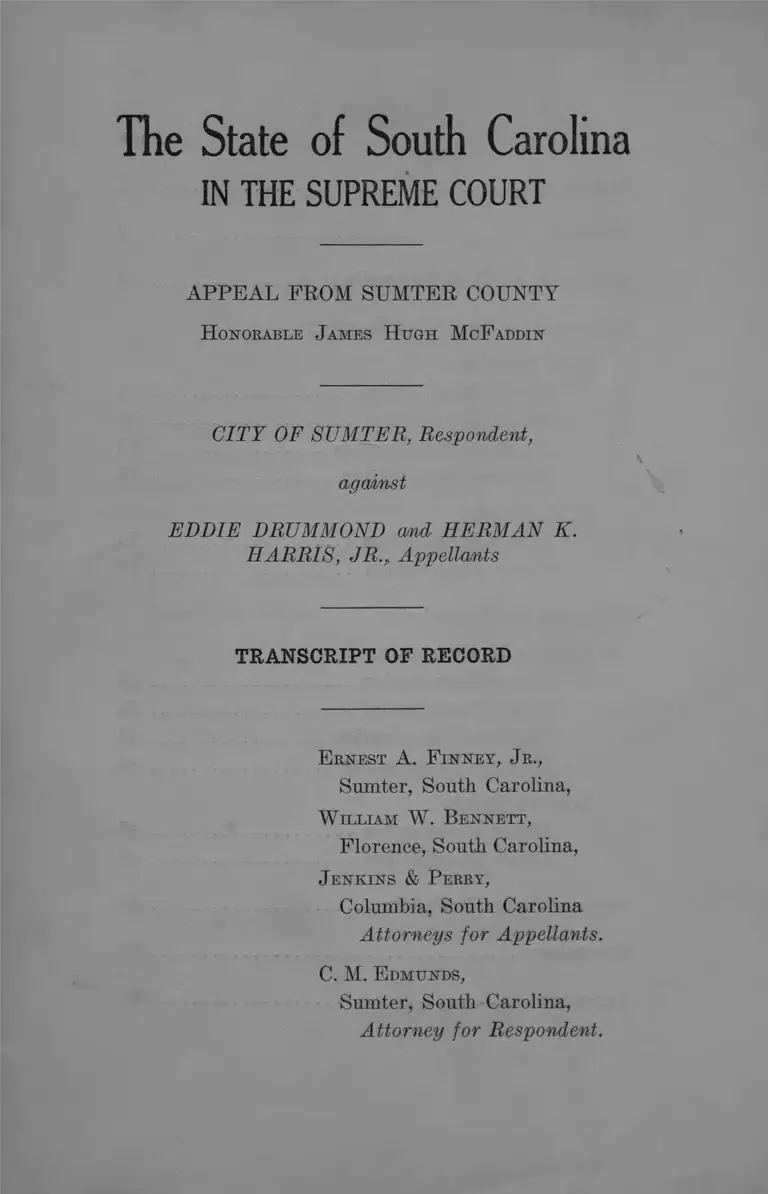

The State of South Carolina

IN THE SUPREME COURT

APPEAL FROM SUMTER COUNTY

H onorable J ames H ugh M cF addin

CITY OF SUMTER, Respondent,

against

EDDIE DRUMMOND cmd HERMAN K.

HARRIS, JR., Appellants

TRANSCRIPT OF RECORD

E rnest A. F in n ey , J r.,

Sumter, South Carolina,

W illiam W . B ennett,

Florence, South Carolina,

J enkins & P erry,

Columbia, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellants.

C. M. E dmunds,

Sumter, South Carolina,

Attorney for Respondent.

P age

Statement.................................................................... 1

Warrant ...................................................................... 2

Transcript of Trial Proceedings ............................ 4

Witnesses for the City of Sumter:

J. H. Lawson:

Direct Examination.................................... 6

Cross Examination .................................... 11

Re-direct Examination .............................. 15

Ke-cross Examination................................ 15

C. M. Brown:

Direct Examination.................................... 16

Cross Examination .................................... 18

Witnesses for Defendants:

Herman K. Harris, J r.:

Direct Examination.................................... 26

Cross Examination .................................... 31

Re-direct Examination.............................. 41

Re-cross Examination................................ 44

Mildred Welch:

Direct Examination.................................... 45

Cross Examination .................................... 46

Order of Judge McFaddin........................................ 48

Exceptions .................................................................. ^9

Agreement .................................................................. 51

INDEX

1

STATEMENT

The appellants, both of whom are Negro College

students, were arrested on February 14, 1961 and

charged with the common law offense of breach of

peace. Appellants were tried before Sumter City

Recorder Raymon Schwarz, Jr., sitting without a

jury, on March 2, 1961. At the conclusion of all the g

evidence, Judge Schwarz found each of the appellants

guilty and sentenced to pay fines of One Hundred

($100.00) Dollars each or serve thirty (30) days in

prison. Notice of Intention to Appeal was duly served

upon the City Recorder.

Thereafter, the matter was argued before Honor

able James Hugh McFaddin, Resident Judge, Third

Judicial Circuit. On February 23, 1962, Judge Mc

Faddin issued an Order, affirming the judgment of the

City Recorder. Notice of Intention to Appeal was

thereupon duly served upon the City Attorney.

4

( 1 )

2 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

AFFIDAVIT

THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA,

City and County of S umter .

Personally came before me Raymon Schwarz, Jr.

Recorder of the City of Sumter E. E. McIntosh who

being duly sworn says: That he is informed and be

lieves that at Sumter, S. C., on or about the 14th day

of February 1961, one Eddie Drummond and Herman

K. Harris, did enter the premises of Lawson’s Phar

macy, in Sumter, S. C. and did sit down for service in

said premises and did fail and refuse to leave said

premises when ordered to do so by the owner and op

erator Dr. J. II. Lawson and by said acts did breach the

peace, in violation of an Ordinance of City of Sumter,

and that deponent and others are material witness to

prove the above allegations.

, /s / E. E. M cI ntosh .

Subscribed and sworn to before me this 14th

day of February, 1961.

/ s / R aymon S chwarz, Jr. (L. S.)

Recorder.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

3

WARRANT

THE STATE OP SOUTH CAROLINA,

City and County op Sumteb .

To the Sheriff of Sumter County or to any or either of

the Policemen of the City of Sumter.

Whereas, complaint upon oath has been made before

me as Recorder of the City of Sumter, by E. E. Mc

Intosh That he is informed and believes that at Sum

ter, S. C., on or about the 14th day of February, 1961,

one Eddie Drummond and Herman K. Harris, did

enter the premises of Lawson’s Pharmacy, in Sumter,

S. C. and did sit down for service in said premises

and did fail and refuse to leave said premises when

ordered to do so by the owner and operator Dr. J. H.

Lawson and by said acts did breach the peace in vio

lation of an Ordinance of City of Sumter in such cases

made and provided.

These are therefore to authorize and command you

to arrest the witnesses above named and Eddie Drum

mond and Herman K. Harris and bring them before

me at Recorder’s Court to be dealt with according to

law.

Given under my hand and Seal this 14th day of Feb

ruary, 1961.

/ s / R aymon S chwaez, J r . (L. S.)

Recorder.

4 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

IN THE RECORDER’S COURT OP THE

CITY OF SUMTER

The above-entitled case came on for trial before The

Honorable Raymon Schwarz, Judge of the Recorder’s

Court of the City of Sumter, on Thursday, March 2,

1961, in the Recorder’s Court Room, Sumter, South

Carolina.

Appearcmces:

For the City of Sumter: C. M. Edmunds, City At

torney.

For the Defendants: Ernest A. Finney Jr., and Wil

liam W. Bennett, Attorneys at Law.

PROCEEDINGS

The Court: Before we get into any of the cases that

we are trying today, I want to make a few statements.

I know that the trial of the cases we are interested

in today will have created a great deal of public in

terest, but, in order that all defendants, as well as the

City, of course, might have a fair trial, this Court in

tends to strictly enforce the rules of the court. We

will not have spectators standing at the rear or in

the halls; we will not have any talking in this court

room during the trial of the case except by those par

ticipants in the case actually concerned with the trial

of the case or cases. Of course, while the Press is wel

come, as it always is in Sumter, there will be no pic

ture-taking, any photographs taken, in this courtroom,

as it is a direct violation, according to the rules of

court.

The only transcript which will be taken will be that

—other than what you might wish to take by writing

or shorthand, or what have you—will be that which is

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

5

taken by the official court stenographer, and there will

be no recording device used by anyone else during

the trial of the case, because, of course, this would

be in conflict with the transcript, with the delegated

authority to the court stenographer to take the official

transcript of the case.

As it is customary in this court to have our colored

citizens sitting to my left, our white citizens sitting

to my right, in view of the large number of colored

people interested in the trial of this case, I am indulg

ing this rule to the extent of permitting the back three

rows on the side to my right to be utilized by colored

citizens of our community, as well as the entire side

to the left. Should there be a trend to shift the number

of colored spectators proportionately to the white

spectators, the Court, of course, would reserve the

right to restate the rule as it originally applies in this

court.

The first cases which are to be tried today are City

of Sumter v. Eddie Drummond and Harris K. Herman.

These two cases will be tried jointly.

Is the City ready, Mr. Edmunds?

Mr. Edmunds: Yes, sir.

The Court: Is the defense ready?

Mr. Finney: The defense is ready, Your Honor.

The Court: The defendants in the case of City of

Sumter v. Eddie Drummond and Harris K. Herman

are charged with a breach of the peace.

How do they plead?

Mr. Finney: Your Honor, before entering a plea, we

would like to make some motions.

We would like to move at this time that the warrant

be dismissed on the grounds that the facts as set forth

in this warrant do not, under the laws and statutes of

6 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al._________

Db. J. H . L awson

the State of South Carolina or of the City of Sumter,

21 constitute the offense of breach of the peace.

The Court: The warrant in the case sets forth that

Eddie Drummond and Harris Kardd Herman did enter

the premises of Lawson’s Drug Store and did order

soft drinks and, upon receiving the same, did sit down

in a booth in said premises and did fail and refuse to

leave said premises when ordered to do so by Dr. J.

H. Lawson, the owner and operator of said business,

and by said acts did breach the peace.

As I have stated in previous trials similar to this

22 trial, it is the opinion of the Court that, knowing the

inflammatory situation, anyone who does any act which

might tend to bring about a breach of the peace would

be guilty of breach of the peace. The burden is on

the City to prove the breach.

Motion denied.

Mr. Finney: We would like at this time to move for

the amendment of the warrant on the grounds that

there is a typographical error. It’s Herman Harris in

stead of Harris K. Herman,

a The Court: No objection?

Mr. Edmunds: No objection.

Mr. Finney: The defense is ready, Your Honor. The

plea is not guilty.

Dr. .J. H . L awson, called as a witness by the City,

being first duly sworn, was examined and testified as

follows:

Direct Examination

By Mr. Edmunds:

0. Dr. Lawson, I believe you are president of Law-

24 4son’s Pharmacy?

A. Yes, sir.

Appeal from Sumter County

SUPREME COURT 7

Dr. J. H. L awson

Q. Do you operate Lawson’s Pharmacy yourself?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. How long have you been at that particular loca

tion?

A. Eleven years; have been in business since 1935.

Q. On the 14th of February of this year were you at

your store, supervising the operation?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. I believe you have a soda fountain in the store;

is that right?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And then you have drugs and the usual things

that a drugstore carries?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. In the front portion of the store, what do you

have, sir?

A. When you enter the door, I have booths on each

side of the door, and then these aisles of merchandise,

and on the right-hand side I have a cigar case, soda

fountain, drink case, delivery counter.

Q. Those booths, about how many tables are there;

do you recollect?

A. There’s three on each side—no, I believe there’s

two on one side and three on the other.

Q. Has it been your custom in past years to sell

drugs and commodities to colored people ?

A. Yes, sir; still is.

Q. And has it been the custom for colored people

to sit at those tables in the front that you described?

A. Never has been.

Q. Have any of them ever sat there in the eleven

years you have operated the store?

A. Not except one time, when they sat down there

and were arrested for doing so.

8 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

De. J. H. L awson

0. That was on this occasion, or—

29 A. No, sir, one prior occasion about a year ago.

Q. And what has been your custom, what was your

custom on the 14th of February, ’61, in regard to sell

ing members of the colored race any soft drinks?

A. We have a room back there in which is a couch

that holds four that they can sit on and drink them,

or they can take them out the store. That’s been the

custom all these years; I ’m doing it today and have

been doing it every day, prior and since.

Q. That’s a private room, with a couch?

80 A. For the colored people.

Q. You don’t furnish that for the white race too?

A. No.

Q. And that has been the custom throughout the

years ?

A. For anyone that wanted to stay in the store and

consume the drinks.

Q. On this occasion, on the 14th, did these two col

ored boys come into your store, whose names are, or

similar to, Eddie Drummond and Harris Kardd Her-

sx man?

A. Two came in there. I don’t know their names or

anything, had never seen them before; they had never

patronized me before, to my knowledge.

Q. And what did they do?

A. Well, the two came in the front door. These two

out-of-town white men came in ahead of them with a

movie camera. One came in Aisle No. 1, came in the

front door and went down Aisle No. 1—

Q. What is Aisle No. 1, so I ’ll—

A. Over next to the fountain. The white men, they

32 were in Aisle No. 2. The other one came down Aisle

No. 3, went to the rear of the store and went over to

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

9

Dr. J. H. L awson

the wrapping counter, where he should. The man at

the wrapping counter asked him what he could serve

him and he said he would like to have a Coca-Cola. He

said “Do you want a large or a small one!” He said

he’d take a large Coke. So he ordered a large Coke in

a paper cup, and he gave it to him.

Q. Did he pay for it!

A. He paid for it. The other one stopped at the

soda fountain. One of the young ladies on duty there

asked him what he wanted. He said he wanted an

orange soda. She said “Well, you go back there where

you see the other colored man and you’ll get service.”

He said “ Do I have to go back there to get service!”

She said “ You do.” So he went back there and bought

an orange drink.

Q. Did he pay for it!

A. Yes, sir. Those two, after getting the drinks,

went across the store like they were going out the side

door on Hampton Avenue, and they turned up the last

aisle and went back to the front of the store and when

they got to the front of the store they came back across

the front and sat in the corner booth on the right-hand

side.

Q. Facing the store, it would be on the right-hand

side!

A. If you come in the front door, it would be on

the right-hand side.

Q. And that corner booth is designed to hold how

many people!

A. Six or eight people.

Q. Was anybody else sitting at that table at the

time!

A. No. They went up there and sat down. When I

saw what had happened, I went up there and I told

10 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

D r . J. H. L awson

them, I said “You cannot sit in here and drink.” They

said “We bought the drinks in here.” I said “Yes, I

know you did, but,” I said, “we do not serve colored

people in the booths and you know it as well as I know

it, so get out.”

Q. Did they get out?

A. They didn’t move, so I put them out.

Q. How did you put them out?

A. I got each one by the coat lapel and walked him

to the front door and put him out. When I came back

the other one was still sitting there and I said “Didn’t

you hear me tell the other one to get out? You didn’t

hear me?” He didn’t answer me, so I just picked him

up and put him out.

Q. When all this was going on, was there or not any

confusion in your store at the time?

A. Yes, sir. These two men from—told me they were

from Huntley and Brinkley News, one of them did, the

pilot of the plane told me they were from there. When

I started up there and got to the front he was already

taking pictures of the colored people sitting in the

booth. So I told him—I said “Don’t take any pictures

in this store.”

Q. That was in the hearing of these colored boys?

A. Yes, sir. I said “Don’t take any pictures of this

in my store and I don’t want to see it on television or

anywhere else.” So then I went over and put the first

one out. I came back and he was still taking the pic

tures. I said “ I told you don’t take no pictures in

here.” I said “Now get out.”

Q. Did he get out?

A. Not until I put the other one out. Then when I

came back I got him out.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

11

Dr. J. H. Lawson

Q. Your store is in the limits of the City of Sumter?

A. Yes, sir.

Mr. Edmunds: You may examine.

Cross Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Dr. Lawson, did you charge these two defendants

with any offense in your store?

A. I didn’t charge them with anything.

Q. Did you sign a warrant for them?

A. No.

Q. When you helped them out of the store, did they

resist you in any way?

A. No, not to my knowledge.

Q. You took one out and you came back and took

the other one out?

A. That’s right.

Q. And there was a photographer in your store, tak

ing pictures?

A. Against my will.

Q. And you ejected him also?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you used force to eject the photographer as

well?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. Did anything else transpire between you and the

photographer?

A. Yes.

Q. What else, sir?

A. I threw the drinks of the boys on him.

Q. You took the drinks that the boys had bought

and threw it on the photographer?

A. Yes, sir.

12 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

Dr. J. H. L awson

Q. About what time of day was this, Doctor?

A. To be perfectly frank with you, I couldn’t swear.

It was before midday; I can say that much.

Q. It was in the morning?

A. It was in the morning, before dinner.

Q. Did you observe anybody doing anything at the

boys, other than you asking the boys to move ?

A. Wasn’t anybody there. I ’m the manager of the

store; nobody else to do it.

Q. There wasn’t anybody else in the store at the

time, sir?

A. Oh, yes, plenty of people.

Q. Did you hear any of these people say anything

to these boys?

A. No.

Q. Did you see any of these people do anything

toward these boys?

A. Not in my knowledge.

Q. You maintain a room in the back of the store

where you serve drinks for members of the Negro

race that wish to come in and sit down?

A. It’s been there for all these years. People eat

dinner there every day, some of the colored people

that work downtown.

Q. Were these boys orderly in your store?

A. Well, so far as stirring up—saying anything to

anybody, they did not.

Q. All right, sir. Then the answer to that question

would be that they were orderly?

The Court: Isn’t that a question for the Court? Isn’t

that what we are here trying, to determine whether it

was any disorderliness or breach of the peace?

Mr. Finney: All right, sir. We’ll ask it this way,

then—we’ll withdraw that question.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

13

Dk. J. H. L awson

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Did the boys say or do anything in your store,

sir, other than—

A. They didn’t say anything, and all they did was

sit in the booth, which they knew was the wrong thing

to do.

Q. Do you know of any law which would prohibit

them from sitting in the booth, sir?

Mr. Edmunds: I object to that question, Your Honor.

The Court: I don’t think he would be the proper

person. If there’s any law, I ’m sure the City Attorney,

if he wanted it in, would put it in and, if there is none,

you will have an opportunity to argue that to the

Court.

Mr. Finney: The only question, sir, was did he know.

I thought he could testify as to whether he had knowl

edge of such—

The Court: He’s a layman. Well, for whatever it’s

worth, I ’ll let him answer the question.

A. I really don’t know what laws are on the books.

Q. Do you know, sir, of any that would require

them—

A. I don’t know of any.

Q. You do have a custom of not serving colored at

your booths in the front of your store; is that correct?

A. It’s always been that way.

Q. And the only reason you ejected these boys was

because they were colored and were sitting in the booth

at the front of your store, sir?

A. There were white ladies up there and all and I

thought it would start a—

Q. Sir, may I ask the question again: The only rea

son you ejected these hoys was because they were col

ored and were sitting in the booths where you, by

14 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

Dr. J. H. L awson

63 custom, did not allow members of the Negro race to

sit?

The Court: I think his answer was responsive to

that, Finney. His answer, as I understood it, was that

there were white ladies up there and he was afraid

it would create a disturbance. Isn’t that definitely re

sponsive to your question? It gives another reason for

the ejection.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Did these white ladies that were present complain

to you, sir?

64 A. They have on several occasions.

Q. Did these white ladies at that time complain to

you, sir?

A. The ones that work for me have.

Q. My question is addressed to the ladies that were

occupying the booths, sir, and you said might cause

some friction. Did they complain to you, sir?

A. I had two.

Q. Did those two ladies complain to you on this

occasion, sir?

66 A. Yes.

Q. What did they tell you?

A. They told me that when they come in there for

the coffee-break they were scared and didn’t want to

be in that kind of excitement. I told them that I didn’t

think it would happen any more.

Q. And then you took it upon yourself to eject the

boys from your store?

A. Yes, sir. I put white ones out as well as colored

when they do things that’s not becoming to the store.

Q. You say you put white ones out as well as colored.

If white ones were to sit down in your booths and were

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

15

Dk. J. H. L awson

conducting themselves as these two young men were,

would you have put them out?

A. No, because they are allowed to sit in the booths;

the colored are not.

Q. Then the reason you put these two boys out was

because they were colored?

A. Yes, that was one of the reasons.

Mr. Finney: Thank you. That’s all.

Re-direct Examination

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Dr. Lawson, you said you never had seen these

colored boys before. Do you think perhaps you would

recognize them if you saw them now?

A. I doubt it.

Q. Well, let’s see. I will ask the defendants to stand

up.

A. Yes, those were the two.

Q. You recognize them?

A. Now I do. I had never seen them before the other

day. If they were in my store before, I ’ve never known

it.

Mr. Edmunds: All right. You may examine.

Re-cross Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Dr. Lawson, do you see anyone else in this court

room that was arrested in your store? Would you like

to stand up and look around? Any that had been ar

rested in your store? You said that prior to this time

you’d had some sit-ins in your store. Do you recognize

anyone else?

A. The one with the white coat, the one next to him.

Q. Those two back there?

16 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

Dr. J. H. L awson

C. M. B rown

A. Yes. This girl over here (indicating). Several of

them were arrested in there that I didn’t take out the

store because—

Q. You do recognize that young lady and these two

young men, the one with the glasses on and the one

sitting next to the wall?

A. Yes. There was more of them, but I—

Q. You recognize those three, sir?

A. Yes, that’s all. There was some others, but I

talked to the ones that was at the head of them.

Mr. Finney: Thank you very much.

(Witness excused.)

Mr. C. M. B row n , called as a witness by the City,

being duly sworn, was examined and testified as fol

lows :

Direct Examination

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Mr. Brown, you are a patrolman for the City of

Sumter?

A. I am.

Q. How long have you been with the City Police

Force?

A. Going on eleven years.

Q. And were you with the City on the 15th or 14th

of February of this year?

A. On the 14th of February, I was.

Q. And were you on duty on that day?

A. I was.

Q. Have you been in court during this hearing?

A. Yes, sir.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

17

C. M. B rown

Q. Now tell me what you know about the case against

these particular boys.

A. When I got there at Mr. Lawson’s it was about

eleven-twenty-five in the morning; it was on Tuesday,

I believe, February the 14th. Mr. Lawson was outside

the door and those two boys right there—

Q. The same ones that stood up a while ago?

A. Yes, sir, the second one and the third—and two

white fellows with movie projectors, they was there,

and these fellows here turned around when Dr. Lawson

brought them out the door and Mr. Lawson told them

to go on. So the two colored fellows walked on off and

the two white fellows were still there arguing. I got

Mr. Lawson quieted down and got him back in the

store. There was a big crowd there, they was all in

the street, a lot of people standing around. I watched

those two boys and they went in Mitchell’s Drug Store.

Q. Alderman’s, or Mitchell’s?

A. Alderman’s. They went in Alderman’s.

Q. That’s right across the street from Lawson’s?

A. Yes, sir, right on the southwest corner. They

went back there to the fountain and they bought two

Coca-Colas, bottled Cokes, and then they went and sat

down in the first booth as you go in to the fountain, the

first booth, and that’s where we got them out of there.

Q. You arrested them and put them in jail?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, when you went in Lawson’s, where were

these boys?

A. They was coming out the door, Mr. Lawson was

bringing the last one out the door at the time.

Q. Approximately—I know you didn’t count them;

you didn’t have time to—approximately how many

18 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

C. M. B rown

people were gathered up there, in and outside the

store ?

A. I would say fifty or better, Mr. Edmunds. The

street was full of them. We finally got them quietened

down.

Q. Did you see Dr. Lawson put one or both of the

white men out of the store.

A. I seen him when he threw the Pepsi-Cola in one

of them’s face and camera and all, and I saw him put

oue of those boys yonder out, too. He’d done put one

of them out when I got there.

Mr. Edmunds: You may examine him.

Cross Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Officer, you said that as soon as you got Dr.

Lawson quieted down you went hack into the store

and went across the street?

A. I watched those two boys. Dr. Lawson was pretty

upset and so were the people around.

Q. Did you ever go into Dr. Lawson’s store?

A. I did.

Q. What did you see happen in there, sir?

A. Well, there was a lot of people standing around,

that’s the only thing. I didn’t see none of the excite

ment in there; it was outside.

Q. Then you don’t know that there was any excite

ment in there, do you, sir?

A. Well, there was bound to he, with all those people.

Q. Did you see it?

A. I didn’t see it. I seen some of it outside the door.

Q. You said it was eleven-twenty in the morning, sir?

A. Eleven-twenty-five.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

19

C. M. B rown

Q. At that time of morning Dr. Lawson has his 73

counter open, serving the public, doesn’t he?

A. That’s right.

Q. And you did not go inside, did you?

A. I didn’t go inside—I went inside after this hap

pened.

Q. Did you go inside before or after you arrested

the two defendants?

A. I went in there afterward.

Q. After you had arrested the two defendants?

A. That’s right. 74

Q. Did you take the to jail?

A. That’s right.

Q. So everything that you saw happened on the

street; is that correct, sir?

,A. No, the door was open and he was bringing one

of them out the door at the time, like to pushed one of

them over me, one of them he was coming out the door

with.

Q. You said there were some people there. Would

you care to estimate how many police officers were n

there ?

A. Two.

Q. There were only two officers?

A. That’s right.

Q. Who was the other officer?

A. Sergeant Conner.

Q. You and Sergeant Conner brought the defend

ants to jail?

A. I did.

Q. That means that no police officer stayed around

there while you were going to the jail?

20 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

C. M. B rown

A. That’s right. There was one more stayed there.

We got one there at the time and one stayed there; I

don’t know which one it was, but one stayed there.

Q. There were three policemen on the scene, then?

A. No, there wasn’t but two at the time and when

the excitement started another police officer came up,

Officer Durant.

Q. You said the excitement started. What was the

excitement?

A. The people crowding in the street and all,

around on the sidewalk, blocked the sidewalk.

Q. What about the throwing of the Coca-Cola into

the cameraman’s face?

A. I seen that.

Q. You saw that?

A. That’s right.

Q. The cameraman was where then?

A. Shooting pictures of Dr. Lawson.

Q. Where, sir?

A. Coming out—backing out the door.

Q. He was in the street when the Coke—he was out

the door then?

A. No, he was right in the edge of the door, backing

out.

Q. Right in the edge of the door?

A. That’s right, backing out.

Q. Did you hear any person say anything inflamma

tory?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Did you see anybody make any threatening ges

tures ?

A. No, I didn’t.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

21

C. M. B rown

Q. Did you see these two defendants do anything

threatening to anybody?

A. I seen them walk out, that’s all, one of them come

out the door.

Q. Did you hear them say anything inflammatory!

>A. No, they didn’t say nothing.

Q. Then do you know of any act, of your own knowl

edge, that they did which was threatening to anybody?

Mr. Edmunds: Your Honor, that comes right back

to this same proposition. We haven’t got a jury here

and, in that event Your Honor is the judge and the jury

and that, I think, is for the jury and the judge, as a

matter of fact and a matter of law.

The Court: I think the way the question was phrased,

anything inflammatory, would be proper. If he had

asked as to breach of the peace or disorderly, I would

exclude it.

Mr. Edmunds: I may be wrong, but I thought he said

did he see them commit any act that was inflammatory.

Is that what you said?

Mr. Finney: Or threatening.

The Court: That would be a fact, not a conclusion. I

believe I will permit the question.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Did you see these defendants commit any act that

was threatening?

A. I didn’t.

Q. Did you hear them say anything that was in

flammatory?

A. No, they didn’t say anything.

Q. Did anyone in Alderman’s ask you to arrest

them?

22 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

C. M. B rown

A. The girl said they sat down without permission;

they were supposed to be out, she didn’t want them in

there.

Q. All she said to you was that they’d sat down with

out permission?

A. And that they wasn’t supposed to sit there.

Q. You are a police officer?

A. I am.

Q. Do you know of any law which would require

them not to be in there, sir?

A. The only law, they ain’t supposed to sit down

86 where the whites sit, that’s all.

Q. Do you know of any law, sir?

A. As a rule, I don’t.

Q. Then the answer would be you do not know of any

law, sir?

A. I don’t know of any.

Q. You do know that there is a custom that the

whites and Negroes do not sit down at the same lunch-

counter?

A. That’s right.

87 Q. So at the time the girl told you that they were

sitting where they did not have permission to sit, did

you ask them to leave?

A. No, we got them on the book on account of they

caused all that disturbance in Lawson’s; that’s what

we arrested them for actually, breach of the peace.

Q. Did you see them cause any disturbance in Law

son’s, sir?

A. We saw the crowd and that’s what it was—that’s

where it was at, and that’s the only reason we arrested

them.

88 Q. Could the crowd have been caused, sir, by the

throwing of the pop in the newsman’s face?

SUPREME COURT 23

Appeal from Sumter County

C. M. B rown

A. No, it couldn’t have—

Q. But yo did see that overt act, didn’t you?

A. I seen that and seen one of them come out with

Dr. Lawson.

Q. But you did not see them doing anything, did you,

sir?

A. No; the only thing I seen them doing wrong was

in there.

Q. Then the only thing they were doing wrong was

violating a custom; is that correct?

A. That’s right.

Q. So you arrested them for violating a custom?

A. That’s right.

Q. And that was your only reason?

A. For breach of the peace.

Q. And the violation of a custom?

A. That’s right.

Q. You realize that the City of Sumter is a part of

the State of South Carolina?

A. Yes.

Q. And that you are an official of the City of Sum

ter?

A. That’s right.

Q. And, in your duty, you were aiding in the mainte

nance of a custom?

A. That’s right.

Q. Now this custom is based solely upon race, isn’t

it, sir?

A. That’s right.

Q. And that is the only reason you arrested these

two defendants?

A. Not solely. For breach of the peace is what I did

it for. on account of disturbance and all the people

around—

24 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

C. M. B rown

Q. But you did not see them commit any overt act,

did you, sir?

A. I didn’t see them do anything in there.

Mr. Finney: Thank you, sir.

(Witness excused.)

Mr. Edmunds: That concludes the City’s case, Your

Honor.

MOTIONS

The defendants move to quash the warrant or, in

the alternative, to dismiss the warrant on the ground

that the statute and laws under which the same is

brought are unconstitutional in that they constitute

an infringement on the rights of these defendants in

the exercise of their rights as guaranteed them by the

Fourteenth and First Amendments to the United

States Constitution, in that the said statutes and/or

laws under which the said warrant is brought deprives

the defendants of their constitutional rights as guar

anteed by said provisions of the United States Con

stitution.

Motion denied.

The defendants move to quash the warrant or, in

the alternative, to dismiss the warrant on the ground

that the statute and/or laws under which the warrant

charging them is brought is violative of the rights of

these defendants as guaranteed them under Article I,

Sections 4 and/or 5, of the Constitution of the State of

South Carolina.

Motion denied.

The defendants move to dismiss or, in the alterna

tive, for a directed verdict on the ground that the evi

dence shows conclusively that the arresting officers

acted for the purpose of assisting the management of

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

25

Lawson’s Drug Store and/or Alderman’s Drug Store

in Sumter, South Carolina, to maintain a custom of

discrimination against the defendants, all Negroes, in

the operation of lunch-counter facilities solely on the

basis of race or color, such conduct on the part of such

police officials, agents of the State, being prohibited

by the guarantees safeguarded to the defendants under

the Due-Process and Equal-Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitu

tion.

Motion denied.

The defendants move to dismiss or, in the alterna

tive, for a directed verdict on the ground that the evi

dence shows that by this prosecution this Court is

being used in the furtherance of a policy or custom of

racial distinction based upon race or color alone, in

the operation of lunch-counter facilities in Lawson’s

Drug Store in Sumter, South Carolina, any such ac

tivity on the part of this Court, an instrumentality of

the State, being prohibited by the Due-Process and

Equal-Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution.

Motion denied.

The defendants move to dismiss or, in the alterna

tive, for a directed verdict upon the ground that the

City of Sumter has failed to establish by competent

evidence the corpus delicti.

Motion denied.

The defendants move to dismiss or, in the alterna

tive, for a directed verdict upon the ground that the

City of Sumter has failed to establish by competent

evidence a prima facie case.

Motion denied.

26 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

H erman K . H arris, Jr., one of the defendants, being

101 first duly sworn, was examined and testified as fol

lows :

Direct Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. What is your name!

A. Herman Harris.

Q. Where are you from!

A. Lancaster, South Carolina.

Q. What are you doing in Sumter!

102 A. I am a student at Morris College.

Q. What’s your classification!

A. Sophomore.

Q. On or about February the 14th, 1961, did you

have occasion to go into Alderman’s Drug Store!

A. Yes.

Q. When you got into Alderman’s Drug Store, tell

the Court what happened.

A. When I got into Alderman’s Drug Store I bought

a soda.

103 Q. Where did you buy the soda!

A. Over at the counter.

Q. What happened after you bought the soda!

A. The fellow with me, we went over and sit down

and we sat there for about approximately two minutes

and two officers came to us. Well, they said “What are

you doing sitting here!” We just looked at them, so

the}T took us by the arm and brought us out.

Mr. Edmunds: Let me interrupt. Where are you

talking about!

104 Mr. Finney: Alderman’s.

Mr. Edmunds: All right

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

27

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

By Mr. Finney: 10B

Q. He took you by the arm and led you out?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did he tell you you were under arrest?

A. No. I asked him, I said “What are you arresting

me for?” He said “ You know you don’t have any busi

ness being in here.” They brought us on down the

street and through the alley there and they stayed be

hind us, told us to come in the blue door. We came on in

and stopped and waited on them. They told us to come

on in. We stopped again. They said go into this room

back there. 10

Q. Which room?

A. That room over there.

Mr. Finney: I would like for the record to indicate

that he is showing the room where the booking station

is at Police Headquarters—I guess that’s what you call

it.

The Court: That’s right.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Did anyone in Alderman’s Drug Store say any

thing to yon? Did the waitress say anything to von! im

A. No.'

0. Did anyone come over and ask you to leave!

A. No.

Q. Did the officer ask you to leave?

A. No.

Q. Was there anyone sitting at the table—what were

you sitting at, the table or a counter?

A. We were sitting at a table.

Q. Was anyone sitting at that table?

A. No one but Mr. Drummond and T. ]08

Q. Was there anyone else at any of the other tables?

A. Yes.

28 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

Q. And no one said anything to you!

A. No.

Q. Did the officer tell you to leave!

A. No, sir.

Q. When you got to the desk back here, what hap

pened then!

A. The officer behind the desk told us to empty our

pockets. So we took everything out of our pockets and

put it on the table. Then he said—

Mr. Edmunds: Your Honor, I object on the ground

that this is no part of the charge here.

110 The Court: Objection sustained. It’s after the actual

occurrence with which the defendant is charged and I

don’t see the relevancy of it.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. When you went into Alderman’s Drug Store did

you say anything to anybody!

A. No, sir.

Q. Did you ask the lady at the counter for what you

wanted!

A. Yes, sir.

111 Q. Did you pay for it!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you get your change back!

A. We gave her a dime for each soda.

Q. Were you—I don’t want you to brag on yourself,

but were you well-dressed, or were you neat!

A. Yes, sir, I suppose.

Q. Were you disorderly in any manner!

A. No, sir.

Mr. Edmunds: I object.

The Court: Tht’s a conclusion that I ’m going to have

to decide. I ’m going to strike that.

112

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

29

H erman K . H aebis, Jr.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Did you do any overt act!

A. No, sir.

Q. Did you go in Lawson’s Drug Store immediately

before you went in Alderman’s?

A. Yes.

Q. While in Lawson’s Drug Store did you buy any

thing?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. What did you buy!

A. I bought an orange soda.

Q. Did you pay for the orange soda?

A. Yes, sir, I did.

Q. What happened after you paid for the orange

soda?

A. I came up the aisle on the left-hand side going out

of the store and sat down at the booth.

Q. Did anyone say anything to you?

A. No.

Q. Did Dr. Lawson come up to you?

A. We sat there for apprixamtely two or three min

utes and someone said “ Dr. Lawson, Dr. Lawson”, and

this elderly gentleman came and grabbed me by my

arm and he said “Nigger, get out” , and I didn’t say

anything. He used obscene language and said “Did you

hear me tell you to get out?”

Mr. Edmunds: I object to his statement there. Let

him say what he said.

The Court: Objection sustained.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. What did he say to you? Don’t say “ obscene” ;

say what he said, if you remember.

A. He said “You God-damned son-of-a-bitch, didn’t

you hear me say get out?” and he grabbed me by my

30

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K. H arris, Jr.

right arm and pulled me out, and Mr. Drummond stood

up also. The man that served us the soda pushed Mr.

Drumond and—

Q. Dd you see him push him?

A. Yes, sir. So this elderly gentleman—I guess he

was Mr. Lawson—pushed us out the store. After he

pushed us out of the door, then he pushed the other

guys out, the camerman. He went back to get my

orange soda and he threw it all over the man, and he

was cursing those men.

Q. Did he give you your money back for your orange

soda?

A. No, sir, he did not.

Q. Did you do anything to resist Mr. Lawson when

he put you out of his store ?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Did you see anyone else do anything in Mr. Law

son’s store?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Did you see Mr. Lawson when he threw the

orange soda at or on the cameraman ?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you know anything about the cameramen

were going to be here?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. And you saw nobody do anything except Mr.

Lawson ?

A. The young man that served us the soda came up

and pushed the young man who was with me; said

“Nigger, didn’t you hear Mr. Lawson say get out of

here?”

Q. So the only persons you heard or saw do any

thing were Mr. Lawson and the young man who served

the soda?

SUPREME COURT_______________

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

31

H erman K. H arris, Jr.

A. There was a young lady there too.

Q. What did she say or do?

A. She was trying to calm this elderly gentleman

they call Mr. Lawson down.

Q. When you say “ calm him down” , what was he

doing?

A. Well, he was cursing and throwing this soda out

on the street on this man and she told him “ Come back

inside, Doctor; don’t get upset.”

Q. When you got on the street did you see anybody

else, did you see many people around?

A. No, sir.

Q. Did you see the officer that just testified?

A. Yes, sir, he and another officer.

Mr. Finney: Your witness.

Cross Examination

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Your name is Herman Harris?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Do you know of any other reason, except just a

mere coincidence, that those camera people came in

that store just the same time you did, or thereabouts?

Mr. Finney: I object, Your Honor. I think that that

calls for a conclusion beyond the knowledge of the

witness that has not been established.

The Court: Well, if the witness doesn’t know, he

can say so. It might be that he had heard. I wouldn’t

know whether it was beyond his knowledge or not.

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Did you know or have any knowledge at that

time that the meeting of you and your friend checked

almost simultaneously with the coming in of the men

32 SUPBEME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al._________

H erman K. H arris, Jr.

with the moving-picture cameras, except a mere co-

L25 incidence1?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Did you know that they were going to be there?

A. No.

Q. Were you told that they were going to be there?

A. No, sir.

Q. Their being there was a complete surprise to

you?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Had you ever been in Lawson’s before this oc-

126 casion?

A. I don’t think so.

Q. You don’t know whether you had or not?

A. No, sir, I hadn’t been in there.

Q. What day of the week was this?

A. The 14th of February, if I recall correctly.

Q. And what day of the week would that be?

A. I don’t know.

Q. Do you have classes every morning of the week

out at Morris College?

127 A. You ask me do I have classes?

Q. Yes.

A. No, sir.

Q. What mornings do you have classes out there?

A. Monday, Wednesday, Friday.

Q. What do you do Tuesdays, Thursdays and Satur

days?

A. Tuesday I have a class at ten o’clock.

Q. That lasts how long?

A. Ten to eleven, and that afternoon I have one from'

one to two, and Thursdays I have only one and that’s

ten to eleven.

128

SUPREME COURT 33

Appeal from Sumter County

H erman K. H arris, J r.

Q. Did you cut any classes in order to come to Law

son’s on this particular day?

A. No, I didn’t.

Q. Do you have to get permission from anybody in

authority out at Morris College to leave the campus?

Mr. Finney: Your Honor, we object to this. I think

it’s going too far afield. I realize it’s cross examination,

but it has no relation, no bearing, upon this charge of—

The Court: I think I see what Mr. Edmunds is lead

ing to, that he’s attempting to delve into whether there

was any possibility of any intention to come into town

purposely to get arrested. Is that what you are—

Mr. Edmunds: That’s my purpose, and if I don’t

link it up I expect Your Honor would strike it.

The Court: I overrule the objection.

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. How did you come to town on this particular

morning ?

A. I came to town in a car.

Q. Whose car?

A. I ’m not positive whose car it was.

Q. How many of you rode in the car?

A. Approximately five.

Q. Did you come with Drummond?

A. Yes, we did; we were together.

Q. And you came for a particular purpose, did you

not?

Q. Did you not come to down to go into Lawson’s

so that you would be arrested?

A. No; no, sir.

Q. Did you not come to town to go into Lawson’s to

sit down at what they call a sit-in demonstration ?

A. No, sir.

34 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K. H arris, J r .

133 Q- the people that you rode to town with in the

car enter into a sit-in demonstration anywhere else in

town on this particular morning?

A. The person that drove the car?

Q. Anybody else in the car with you?

A. I don’t know what you mean by—

Q. Just give me the names of the people you rode

to town with.

A. Mr. Moore, Mr. Drummond, myself, Mr. Andrew

Pollard.

Q. How do you spell that last name?

134 A. I don’t know.

Q. Well, is it P-a-r-k, or Parler, or what?

A. Pollard.

Q. P-o-l-l-a-r-d?

A. I don’t know; it’s not my name.

Q. You say you are a sophomore at college?

A. Yes, sir, I am.

Q. Did you not know on this particular morning that

there were going to be sit-ins in several places in the

city?

1 3 5 i -x-rA. No, sir.

Q. Did you not know that you would not be allowed

to sit down at those front counters in Lawson’s?

A. Would you restate the question, please?

Q. You had no trouble hearing your lawyer. Why

can’t you hear me? Did you not know that you were

not allowed, and would not be allowed, to sit down at

those counters in Lawson’s?

A. No, sir, I did not.

Q. You did not?

A. No, sir. There was no sign to say where I could

sit.

136

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

35

H erman K. H arris, Jr .

Q. Well, have you been coming downtown during

the two years you have been here!

A. This is my first year here in Sumter.

Q. When did you come here—in September?

A. Yes, sir, I did.

Q. From September until February did you come

downtown and sit down at counters that sell food in

Sumter?

A. Well, no.

Q. You did not; you never tried it before?

A. No, sir.

Q. Well, tell me this: Why didn’t you sit down at

the counter when you first went into the drug store

and then ask for service?

A. Isn’t it the policy that you go back and order

your drinks before you sit down?

The Court: Don’t answer the question with a ques

tion. Just answer the question.

The Witness: Well, I wanted to get my soda first

and sit down.

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q! Why?

A. Because I though that was the policy.

Q. You did?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You don’t think that people sit down at coun

ters in cafes and so forth and a waitress comes up and

asks what they want and they serve them?

A. I don’t know, sir.

Q. But you did not sit down there when you first

went in, did you?

A. No, sir.

Q. You went back to the wrapping counter on the

right-hand side as you go in the store, did you?

36 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

A. I guess you’d call it the wrapping counter. I

don’t know what it was.

Q. And you asked for an orange drink, I believe!

A. May I say something!

Q. Just answer my question.

A. No, sir.

Q. What did you ask for!

A. Well, I went to the counter and the lady stand

ing there, she never did wait on me, and we went on

down to another, possibly five feet, and a young man

waited on me.

142 Q. And you bought an orange drink from him!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. You paid him a dime for it!

A. I did.

Q. Was Drummond right by you!

A. Yes, he was.

Q. And what did he order!

A. I don’t recall directly, but it was soda in a cup.

Q. Yours was in a glass and not in a cup!

A. Yes, it was in the bottle.

143 Q- Now when you and Drummond got your drinks

and paid the man didn’t you head back through the

store toward the entrance on Hampton Avenue!

A. No, sir.

Q. Where did you go after you got your soda!

A. We came on up the aisle.

Q. Which aisle!

A. The aisle on the left-hand side, coming out of

the store.

Q. The aisle right by the soda fountain!

A. Yes.

144 Q. And you went up there and you sat yourselves

down at a booth!

SUPREME COURT 37

Appeal from Sumter County

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And that was the booth in the corner that would

hold some six to eight people, I believe?

A. That’s right.

Q. Did Dr. Lawson come up and tell you you weren’t

supposed to be sitting there and to get out, or words

to that effect?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And, just like he says, you didn’t get out, did

you? You just looked at him and said nothing?

A. He didn’t say that.

Q. What did he say?

A. He came up and first thing he did was start

cursing and grabbed my arm and pulled me out; that’s

the way he said get out.

Q. Didn’t he tell you “Boy, don’t you know you got

no business here? Now get out” ?

A. No, sir, he had me when he was telling me that.

Q. Well, did you get out?

A. Well, yes, I got out.

Q. Didn’t he get you by the lapel of your coat and

pull you out?

A. He had my arm. No, sir, he didn’t have my lapel.

Q. And that’s exactly what you expected to happen,

wasn’t it?

A. No, sir.

Q. By that time you realized, then, that you weren’t

allowed to sit at the counter in Lawson’s and ask for

service or sit down and drink; is that right?

A. I suppose so.

Q. Very definitely—isn’t that so? From the lan

guage you say he used, could he have used any

stronger language?

A. I don’t think he could have.

SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

Q. All right. So you went right across the street to

Lawson’s and pulled the same trick, didn’t you!

A. Alderman’s!

Q. Alderman’s, yes.

A. Yes, sir.

Q. When you had just been thrown out of Lawson’s!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Didn’t the young lady tell you you weren’t sup

posed to sit in Alderman’s and ask you to get out and

you didn’t do it!

u» A - Tes> sir’

Q. And just momentarily after that the police came

in and arrested you, didn’t they!

A. That’s right.

The Court: Let me ask you one question. Have you

heard of any other Morris College students in the last

several months being arrested for using the counters

or booths in other stores on Main Street in the city o£

Sumter!

The Witness: Yes, sir, I ’ve heard about that.

161 The Court: When you told Mr. Edmunds that you

knew that it wasn’t prohibited to sit down at these

places—I’m not trying to quote—that wasn’t entirely

accurate; you had knowledge of other people being

arrested for the same thing that you did—is that cor

rect!

The Witness: Yes, sir, I heard about it, read

about it.

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Do you deny in this proceeding and to the Court

o that you weren’t intentionally participating in what

162 you read in the papers about sit-in demonstrations!

A. Would you restate the question, please!

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

39

H erm an K . H arris, Jr.

Q. Do you deny that you weren’t knowingly partici

pating on this occasion in what we commonly call—

you say you read the newspapers—a sit-in demon

stration ?

A. Yes.

Q. You deny that!

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Then you say that you were perfectly innocent

in your actions in this matter!

A. I do, sir.

Q. That you sincerely thought that you could either

have sat down there and been served or do as you did,

get your drink and go and sit down and drink it!

Mr. Finney: Your Honor, we object to the question.

It is long and involved and actually leading to the wit

ness. I realize this is cross examination—

The Court: On cross examination I think it’s a

proper question. Objection overruled.

Will you read the question, Mr. Reporter!

(Pending question read by the reporter.)

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. What’s your answer to that?

A. Yes, sir.

The Court: Let me ask you this: Why did you think

that you would receive any different treatment from

the treatment other students that you knew about had

received ?

The Winess: Will you repeat the question, please?

The Court: I will. Why did you think you would

receive any treatment from the treatment other stu

dents you had read about had already received before

you?

40 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

The Witness: Well, Your Honor, I thought that,

just being free, a person could buy something, if he

could buy anything else in the store—

The Court: That’s not an answer to my question, I

don’t believe. Did you understand the question!

The Witness: I don’t think so.

The Court: You have testified that you had heard

that other Morris College students had been arrested

for doing exactly what you had on this day; is that

right!

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: And you have further testified that you

felt that you could go in and sit down and do these

things without any fear of being bothered whatsoever;

is that right!

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: How do you reconcile the two state

ments, that others had been arrested for doing exactly

what you did, how is it you felt that you could do it

and be above the law and not be arrested!

The Witness: Because I didn’t think that was the

law, arresting a person for sitting down like that.

The Court: Had you read further in the paper that

these other Morris College students had been con

victed for breach of the peace!

The Witness: No; frankly, I don’t know what that

means.

The Court: Do you know that they had been tried

and found guilty of something as a result of what they

did!

The Witness: No, sir.

The Court: You didn’t know that!

The Witness: No, sir.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

41

H erman K. H arris, J r .

The Court: But you knew they had been arrested?

The Witness: Yes, sir.

The Court: And you didn’t think you would be ar

rested for doing exactly the same thing they had done?

The Witness: No, sir, I didn’t.

The Court: Mr. Edmunds, I didn’t mean to inter

rupt your examination.

Mr. Edmunds: That’s all right.

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. I believe you were saying that you felt that they

were free and would have the right to do what they

did without being arrested; isn’t that what you said?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And you resented the fact that those others had

been arrested and convicted, did you not?

A. Would you restate the question, please?

Q. You resented the fact that the ones you read

about had been arrested and convicted?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Then you thought you would try it and see how

you came out?

A. No, sir.

Q. You were going to demand your rights as you

considered them to be; is that right?

A. I think that would be right, yes, sir.

Mr. Edmunds: That’s all.

Re-direct Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Since the Court and prosecuting attorney have

gone into what happened before and since, have you

heard of any change in the policy of any stores in the

42 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et at.

H erman K. H arris, J r .

166 city of Sumter since your arrest, as to serving mem

bers of the Negro race at lunch counters?

A. I think so.

Q. And what is that change which you have heard

of?

Mr. Edmunds: Your Honor, I know both Counsel

Finney and myself have gone into Alderman’s, which

was part and parcel of it, and what happened before

and his intent would be part and parcel of it and,

therefore, relevant, but if, considerably subsequent to

the time of this particular occurrence, there has been

some change, it could not, if it please the Court, affect

the question of his intent or his feelings in the matter

or his actions on this occasion, if it happened even a

day after this took place.

Mr. Finney: Your Honor, we ask the question be

cause of the fact that the point has been raised as to

the question of the enforcement of this custom and

did he know. Of course, we take the position that this

is a maintenance of a custom and customs can change,

and the Court went into that realm and we were merely

167 trying to show that there has been, in fact, a change

of custom perhaps in this locality.

The Court: Let me hear a little bit more before I

rule on the question. I think your first question cer

tainly is not objectionable, but I agree with Mr. Ed

munds that the time element is very important in this

kind of question.

Mr. Finney: I don’t remember what the question

was now, but—

The Court: I think I can almost rephrase it for you:

Have you heard of any change in custom?

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

43

H erman K. H arris, Jr.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Have you heard of any change in custom in the

city of Sumter since the beginning of this year?

A. I think so, yes, sir.

Q. What was your knowledge of that?

The Court: Before I ’m going to let him answer I ’m

going to want it tied down as to when he heard of it

and when the change of custom took place.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Do you know when you heard of this change?

The Court: Let me ask a question that might clarify

it. Did you hear of this change before you were ar

rested or after you were arrested?

The Witness: After I was arrested.

The Court: I am going to rule the line of question

ing out. It could not have had any effect on his inten

tion at the time.

Mr. Finney: All right, sir.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. As a student, do you know that customs do

change; before you were arrested, did you know that

customs have a habit of changing?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you know of any law which would prohibit

your sitting down, at a lunch counter or at a table in

Lawson’s or Alderman’s?

A. No, sir.

Mr. Finney: That’s all.

44 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

H erman K . H arris, Jr.

us Re-cross Examination

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Did you know of any law that when you go into

a private place of business and they ask you to leave

that you are required by law to leave promptly?

A. If it’s private, yes, sir.

Re-direct Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. What type of store is Lawson’s?

174 A. It’s a drug store.

Q. Do they have other counters in there?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Did you see members of the public in there at

the time you went in there?

A. The public, yes, sir.

Q. Did you see members of the public in Alderman’s

also?

A. Yes, sir.

(The witness excused.)

175 Mr. Edmunds: Do you want to stipulate that the

other witness will testify likewise? It suits me, if

you do.

Mr. Finney: All right.

I think we want to put one additional witness on the

stand to clarify one point. The defense calls Mildred

Welch.

176

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

45

M ildred W elch

M ildred W elch , called as a witness by the defend^

ants, being first duly sworn, was exam ined and testi

fied as fo llo w s :

Direct Examination

By Mr. Finney:

Q. What is your name?

A. Mildred Welch.

Q. Did you hear the gentleman who identified him

self as Dr. Lawson testify this morning?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. Did you see Dr. Lawson point you out as a per:

son who was arrested in his drug store?

A. Yes.

The Court: Let me ask this: What’s the relevancy

of this?

Mr. Finney: Challenging the credibility of the iden

tification.

The Court: On a collateral matter?

Mr. Finney: Yes, sir.

The Court You can’t test it on a collateral matter.

Mr. Finney: Your Honor, he has identified these

gentlemen as persons and he identified others on the

stand who had been arrested, and he testified—

The Court: What do you say, Mr. Edmunds?

Mr. Edmunds: I have no objection.

The Court: All right, you may proceed.

By Mr. Finney:

Q. Did you hear Dr. Lawson identify you as an in

dividual who had been arrested in his drug store?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Are you a student at Morris College?

A. No, I am not.

Q. Have you ever been arrested in Dr. Lawson’s

drug store?

46 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

M ildred W elch

A. No, I haven’t.

Q. Did you attend Morris College at one time?

A. Yes, I did.

Q. Have you ever participated in a demonstration

in Dr. Lawson’s drug store?

A. No, sir.

Q. Or any other demonstration in and about the city

of Sumter?

A. No, sir.

Mr. Finney: Thank you. Your witness.

Cross Examination

By Mr. Edmunds:

Q. Have you been arrested anywhere in town in the

last six months?

A. No, sir.

Q. Do you go to Morris College?

A. No, sir.

Q. Where do you live?

A. I reside at 210 Brown Street.

Q. What’s your business?

A. I teach.

Q. What do you teach?

A. I ’m not teaching at the present time.

Q. What do you do now for a living?

A. Sitting down—

Mr. Edmunds: Sitting down? You can go back there

and sit down.

The Court: Sitting down, or sitting in?

The Witness: Sitting down at home.

(The witness excused.)

The Court: Anything in reply for the City, Mr.

Edmunds?

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

47

Mr. Finney: I think, as Mr. Edmunds has already

indicated, we will stipulate that if we were to call the

other defendant he would testify—

Mr. Edmunds: That he would testify to the same

things.

Mr. Finney: Your Honor, at this time we would like

to get an agreement from Mr. Edmunds that we re

new our motions made at the end of the City’s case.

Mr. Edmunds: That’s all right.

MOTIONS

It is stipulated that the defendants at this point re

new each and all of the motions heretofore made at the

close of the City’s case, and that each and all of the

said motions are denied.

JUDGMENT

The Court found each of the defendants guilty as

charged and imposed fines of one hundred dollars or

the service of thirty days as to each of the defendants.

MOTIONS

It is stipulated that the defendants at this point

move for arrest of judgment or, in the alternative, for

a new trial upon each and every of the grounds as

signed in the motions heretofore made prior to the

plea, at the close of the City’s evidence and at the close

of all of the evidence, and that each and all of said

motions are denied.

Mr. Finney: We wish to give oral notice of inten

tion to appeal and will file written notice.

(Thereupon, the trial of the above-entitled case was

concluded.)

48 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

ORDER

These defendants were convicted by the Recorder of

the City of Sumter for breach of the peace under a

warrant setting forth that they did enter the store of

S. H. Kress, a private mercantile establishment, and

they sat down at the lunch counter and were requested

to leave by the manager or his agent and that they

refused to leave, for which they were subsequently ar

rested and found guilty of breach of the peace.

The exceptions raise the issue that the Recorder

erred in refusing the motion to quash the warrant

upon the grounds that the facts therein stated did not

constitute a breach of the peace, that the arrest of the

officer constituted state action, that the statutes and

ordinances under which the warrant was issued, which

are unconstitutional in that they infringe upon the

rights of the defendants as guaranteed by the first and

fourteenth amendments of the Constitution of the

United States, and article one, sections four and five

of the Constitution of South Carolina; and that the

defendant has been denied the right of freedom of

speech and assembly as guaranteed by the first amend

ment of the Constitution of the United States; and

that the evidence fails to make out a prima facie case

against the defendants; and motion for direction of

verdict should have been granted. These same ques

tions are presented as errors for motion of arrest of

judgment and of a new trial.

The facts are undisputed and briefly stated, the de

fendants are colored and went into a private store,

made a purchase and sat down at the lunch counter

and were requested by manager or his agent to leave

and that they refused to leave. Trial and prosecution

for breach of the peace followed.

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

49

It may now be said to be the settled law of this state

that one who enters a private establishment and re

fuses to leave at the request of the management or

agent is guilty of trespass and breach of the peace and

that no constitutional rights guaranteed by either the

United States Constitution or South Carolina Consti

tution have been violated. (State v. Bouie, Feb. 13,

1962.

The exceptions are, therefore, without merit and the

conviction of the Court below is affirmed, and

It is so ordered.

J ames H tjgh M cF addin,

Judge of Third Judicial Circuit.

Manning, S. C.,

February 23, 1962.

EXCEPTIONS

1. The Court erred in overruling appellants’ motion

to quash the information and dismiss the warrant,

made upon the ground that the warrant does not set

forth or allege facts sufficient to constitute a breach

of the peace.

2. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the City

of Sumter failed to establish the corpus delicti or

prove a prima facie case, in that:

(a) It was not shown that appellants engaged

in conduct which was unlawful.

(b) It was not shown that appellants committed

acts which directly tended to breach the peace.

(c) It was not shown that appellants committed

acts or engaged in conduct which incited others to

violence.

(d) It was not shown that appellants committed

acts of violence.

50 SUPREME COURT

City of Sumter v. Drummond et al.

(e) It was not shown that appellants engaged in

obscene conduct.

(f) It was not shown that appellants uttered

profane language.

(g) It was not shown that appellants conducted

themselves in disorderly fashion.

3. The Court erred in refusing to hold that appel

lants were convicted upon a record devoid of any evi

dence of the commission of any of the essential ele

ments of the crime charged, in violation of appellants’

right to due process of law, guaranteed by the Four

teenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

and by Article I, Section 5, Constitution of the State

of South Carolina.

4. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence shows conclusively that by arresting appellants,

the officers were aiding and assisting the owners and

managers of Lawson’s Pharmacy in maintaining their

policies of segregating or excluding services to Ne

groes at their lunch counters on the ground of race

or color, in violation of appellants’ right to due proc

ess of law and equal protection of the law, secured by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution.

5. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence shows that by arresting appellants, the officers

deprived them of their rights to freedom of expression

and freedom of speech, protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Consti

tution.

6. The Court erred in refusing to hold that the evi

dence offered against appellants, all Negroes, estab

lishes that at the time of their arrests, they were at

tempting to use a facility, the lunch counter of Law-

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Sumter County

51

son’s Pharmacy, open to the public, which was denied

them solely because of race and color, in violation of

the due process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution.

AGREEMENT

It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between

counsel for the appellants and respondent that the

foregoing, when printed, shall constitute the Tran

script of Record herein and that printed copies thereof

may be filed with the Clerk of the Supreme Court and

shall constitute the Return herein.

C. M. E dmunds,

Sumter, S. C.,

Attorney for Respondent.

E rnest A. F in n ey , Jr.,

Sumter, S. C.,

W illiam W . B ennett ,

Florence, S. C.,

J enkins & P erry,

Columbia, S. C.,

Attorneys for Appellants.