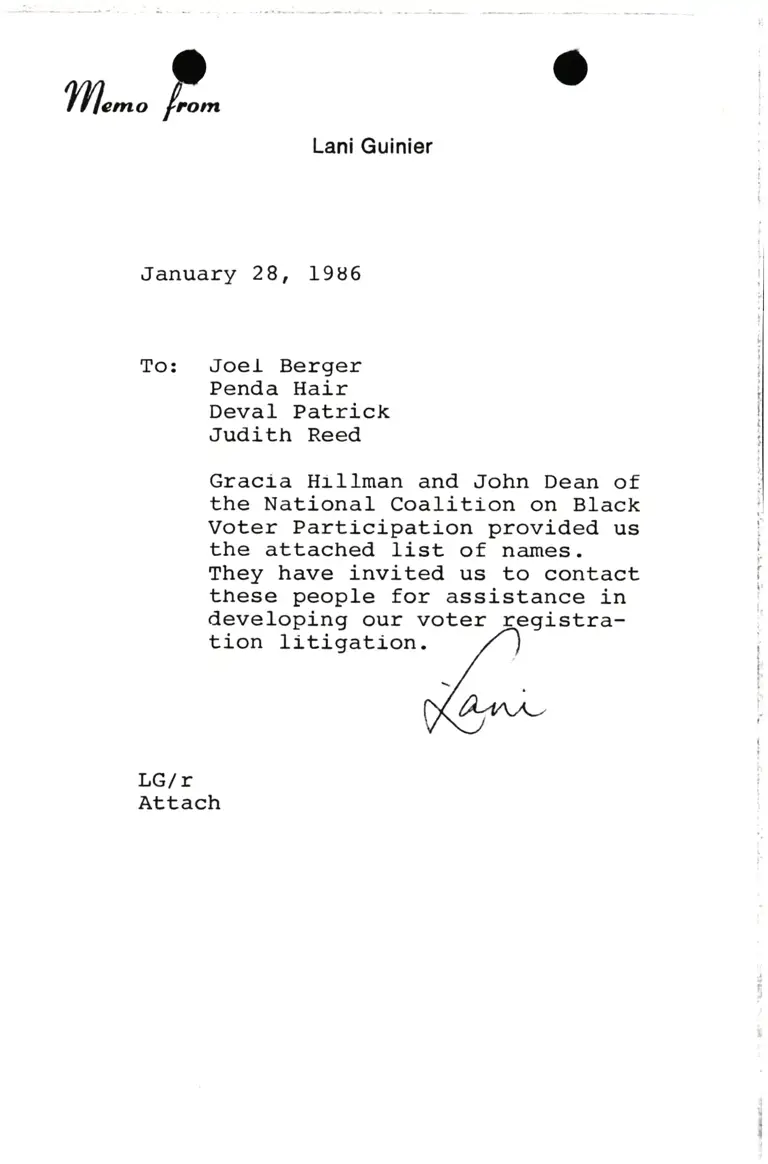

Memorandum from Lani Guinier to Joel Berger, Penda Hair, Deval Patrick, and Judith Reed

Correspondence

January 28, 1986

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Memorandum from Lani Guinier to Joel Berger, Penda Hair, Deval Patrick, and Judith Reed, 1986. 6b09bd6d-e992-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11290ccb-3db6-41a1-85e0-df2432af3a65/memorandum-from-lani-guinier-to-joel-berger-penda-hair-deval-patrick-and-judith-reed. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

T/l",no E^

Lani Guinier

January 28, 1986

To: Joel Berger

Penda Hair

Deval Patrick

Judith Reed

Graci-a Hrllman and John Dean of

the National Coalition on Black

Voter Participation provided us

the attached list of names.

They have invited us to contact

these people for assistance in

developing our voter Eegistra-

tion titiiation. /)

-

/

-/Kry

LG/ r

Attach

n

I