United States v. The Board of Education of the City of Bessemer Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 25, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. The Board of Education of the City of Bessemer Brief for Appellant, 1966. aa66404b-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11631604-3e67-41e4-8587-bf9d9ea8e30f/united-states-v-the-board-of-education-of-the-city-of-bessemer-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

r d R -

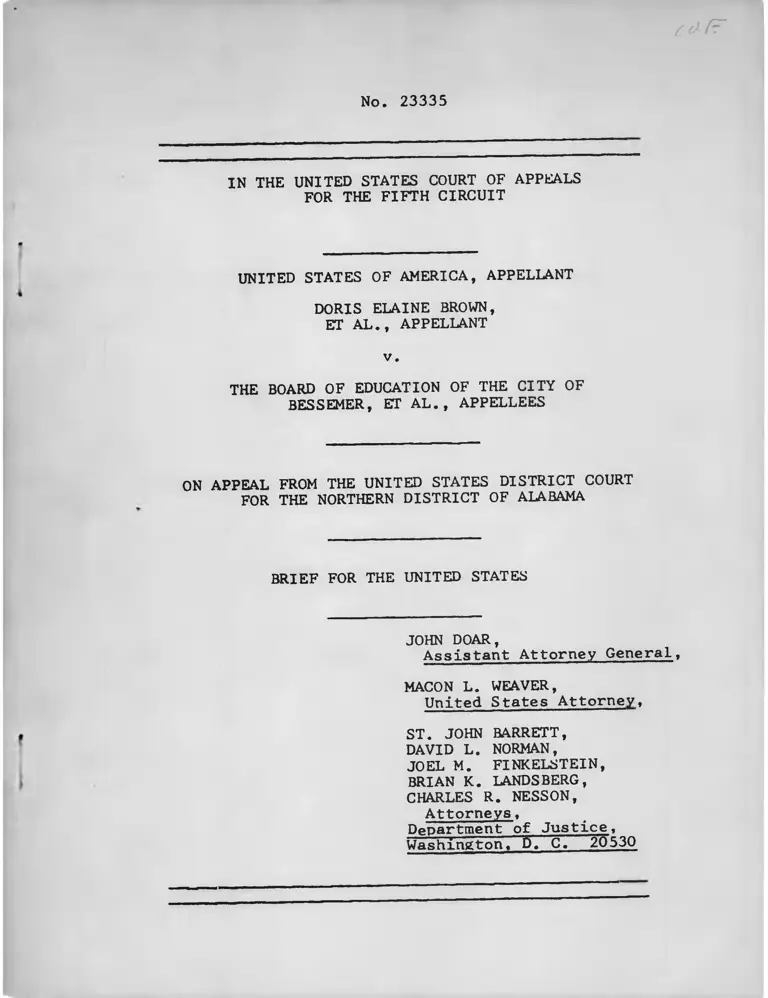

No. 23335

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLANT

DORIS ELAINE BROWN,

ET AL., APPELLANT

V.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

BESSEMER, ET AL., APPELLEES

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

JOHN DOAR,Assistant Attorney General,

MACON L. WEAVER,United States Attorney,

ST. JOHN BARRETT,

DAVID L. NORMAN,

JOEL M. FINKELSTEIN,

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG,

CHARLES R. NESSON,

Attorneys.Department of Justice,

Washington. D. C. 20530

INDEX

Page

Statement of the Case----------------------- 1

Specification of Error---------------------- 6

Argument------------------------------------ 8

A. The plan retains racial assignments

of students in grades purportedly

desegregated.---------------------- 8

B. The plan fails to provide specific

standards, procedures, and notice

for the exercise by students of the

right to attend desegregated

schools.--------------------------- 12

C. The Plan fails to contain provisions

designed to eliminate the inferiority

of schools traditionally attended by

Negroes.--------------------------- 15

D. The plan fails to contain a provision

designed to eliminate the racial seg

regation of faculty and staff.-------- 18

E. The plan fails to guarantee to students

who transfer that there will be no racial discrimination or segregation

in services, activities, and programs, provided, sponsored by or affiliated

with the school system.-------------- 20

F. The plan fails to contain a provision

allowing Negro students in non-deseg-

regated grades to transfer to schools

from which they have been excluded

because of race.---------------------21

Relief-------- ----------------------..... . 22

Conclusion------------------------------------^0

GASES

Page

Anderson v. Canton Municipal Separate

School District, Civil Action No.

3700 (J) TĈ TS.D. Miss., August 5,

1965)---- -------------------------------- 16

Baird v, Benton County Board of Education,

iCivil Action No. 6531 (N.D. Miss., August

3, 1965)----- ---------------------------- 16

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (C.A. 5,

— r W T --- ...........-..................... 19

Beckett. United States v. School Board of

the City o^ Norfolk, Virginia, Civil

Action No. 22li+ (E.D. VaT March 17, 1966)- 30

Beckett v. School Board of the City of

Norfolk, Civil Action No. 2214 CE.O. Va.,

1̂ 66)'— ------- --------------------- — 33

Bradl^ v. School Board, Richmond, Va.,

345 F. 2d 3l0 (C.A. k] 1965) vacated and

remanded 382 U.S. 103 (1965);------------ 11

Bradley v. School Board, Richmond, Virginia,

■ 3B2"U.S. 103“ ( - - .... ..... 18

Bradley v. School Board, Richmond, Civil

Action No"̂ 3333 (E.D. Va. 1966)---------- 34

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S.

533 (1954)..... ...... ... .........-..... 9

Brown v. County School Board of Frederick

County, Virginia, 245 F. Supp. 546, 56b

(W.b. Va., 1^65)..... .................. - 19

Bush V. Orleans Parish School Board, 308

F. 2d 591 (C.A. 5, 1962) — ....... ........ 10

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

CTvil Action No, 23T^f(H7D7*3STaT7"35arcTi

22, 1966)......... -.............-........ 16

11

Cases--Continued Page

Carr. United States v. Montgomery

CountV Board of 'EducationT Civil Action "«o. (^.b.'~ATa..

March 22, 1966).......................... 30

Carroll v. Bolivar County Board of

Education. Civil Action tJo. 6531 (N,d7 ̂ iss,, August 27, 1965)---16

Dowell V, School Board of Oklahoma

glty. 2t*H F. Supp. 971 cW.D. Okla.

T ^ ) ........ -......-................... 32

Gilliam v. School Board of the City

of ttooewell. Virginia, Civil Action

Wo. 3S5U ('E.P. Vl."l-966)................. 33

Green v. School Board of City of

— IToanoke. SOU F. 53 118, I2i cu.A.

U , 1 9 S 7 ) ................................................................................................................. 1 0

Harris. United States v. BullockCountv Board of Education, Civil ActionWei. 2673-TrWrD. Al'^7^?5?ch 11, 1966).... 30

Kemo' V. Beasley, 352 F. 2d lU, 22 (C.A.

*^*17 1963)---— -........................... 9

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta

County, Virginia, 299 F. Supp. at 2^6

(W.D.^^a.; T% FT-........................ 19

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta

“ T^unty, P. Supp. 239 CW.D. 7a.7"1966' ) - - ................................................. - ................................................................................. 25

Lee. United States v. Macon County Board

ot ^ucatlon. Civil Action No.

W.D. Ala'.; March 11, 1966)............ — 30

Lockett V. Board of Education of Muscogee "County. 3^2 P. 2a"275, 258 (C.A-.~57 W U )- 9

McGhee. United States v. Nashville Special

Sctiool District No. 1. Civil Action Wo.WIDT'Ark., March' 3, 1966)........... 30

111

Cases--Continued Page

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

■35^"U.S. 637 ----- - -— ---- ----- 20

Miller v. Clarendon County School

District No. 2, D.C.S,C. Civil

Action No. 8752 decided April 21,

1966....... ........... -.....-......... 25

Northcross v. Board of Education of"nSitv oT~Memphis, 302 3d ~81'5~Cc.A.

6) cert. den. J70 U.S. 9̂+̂+ (1966)-------- 10

Norwood V. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798

(C.A. 8, 1961)----------------- ----- ---- 10

Price V. Denison Independent School district Board of Education, 348

F. 2d IdlO, (C.A. 5, 1965)^------ ------2

Price V. Denison Independent School District.“348 F.' 2d 1010, 1013-1/+

(C.A. 5, 1965)------------ -------.......- 23

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965),

t e “U . S . T W (1965).... -................. 18

Scott V. Walker. F. 2d ___ (C.A. 5,No. 20814 decided March 31, 1966)--------- 28

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

SchoolDistrict, 348 F. 2d 729 QC.A.5, I965y-— -------------- 2

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 355 F. 2d 865 (C.A.

5, 1966)------ 18

Singleton V . Jackson Municipal Separate

School "District, supra at 870— ----------- 18

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

SchoolDistrict, 335 F. 3a 865, 869, (C.A.5, 1 9 6 6 ) ........ 21

Stell V. Savannah-Chafham County Board of

Education. 333 F. 2d 55. 65 (C.A. 5, 1964)- 11

Stell V. Savannah-Chatham County Board of

Education, 333 !f . 2d 55 (C.A. 5, 1964)--- 13

IV

Cases--Continued Page

United States v. Carroll County Board

of Education, Civil Action No. GC d5UL

(N.D. Miss. , January 20, 1965)----------- 17

United States v. Duke, 332 F. 2d 759,

768-69, TcTa . 57T^6ii)-..... ------------- 19

United States v. Lowndes County Board

of Education, Civil Action No. 2328-N

(M.D. Ala. , Feb. 11, 1966).... ....... . 30

United States v. Palmar, ___ F. 2d ___C.A. 5, (No. 216U6, decided February 8,

1966)------------------------------------ 28

United States v. Ward, 3k9 F. 2d 795

(C.A. 5,'"1T65)--------------------------- 28

Wright V. County School Board of Greenville

County, Civil Action No. 5763 (E.D. Va.,

January 27, 1966)------------------------ 25

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

Civil Rights Act of 196i+, Section 902------ 2

Code of Alabama, 19U0 (Recompiled 1958)---- 5, 10

Miscellaneous:

Alabama Pupil Placement Law---------------- 10

Revised Statement-------- -------------- H» 1^* 19» 20

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 23335

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, APPELLANT

DORIS ELAINE BROWN,

ET AL., APPELLANT

V ,

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

BESSEMER, ET AL., APPELLEES

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Procedural history and status. On May 24,

1965, Negro plaintiffs, residing in Bessemer, Alabama,

instituted a school desegregation suit against the

Board of Education of the City of Bessemer and its

members in the District Court for the Northern District

of Alabama (R. 11-19). The United States Intervened

pursuant to Section ^02 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. 2000h-2 (R. 20-21). Upon finding that the

Board maintained a racially segregated school system,

the district court entered an order requiring the

Board to submit a plan for desegregation (R. 37-42).

On July 30, 1965, the court entered an order

approving with modifications the Board's plan (R. 64-6?).

The plaintiffs and the United States appealed and, on

August 1 7, 1965, this Court vacated the district court

order and remanded the case for further consideration

in light of Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 348 F. 2d 729 (C.A. 5, 1965) and

Price V. Denison Independent School District Board

of Education, 348 F. 2d 1010 (C.A. 5, 1965). Upon

remand, the Board filed an amendment to its school

desegregation plan which was approved by the court

on August 27, 1965 (R. 85-86). The plaintiffs and

the United States noted an appeal to this Court (R. 87-88)

Summary of the desegregation plan. The plan

purports to desegregate the 1st, 4th, 7th, 10th and

12th grades in September, I965 (R- 45, 64-65, 80-82);

the 2nd, 3rd, 8th and 11th grades in September, I966

(R. 45, 65); and the 5th, 6th, and 9th grades in

- 2 -

Septemoer, 196? (R. ^5, 65, 81-82). Pupils in grades

reached by the plan, except the 1st grade, may apply

between May 1st and 15th "to a school heretofore

attended only by pupils of a race other than the

race of the pupils in whose behalf the applications

are filed" (R. 43-45).

Children entering the first grade are required to

report to a designated school in the vicinity of their

residence -- a designated Negro school for Negro children

and a designated white school for white children. There,

the parents of the child may fill out an application

requesting that the child be reassigned to any school

serving first graders in the district" (R. 43-45).

1/ The district court in approving the Board's plan

"excepted the provision governing the initial assign

ment of pupils to the first grade. Because_school was

scheduled to open within four days of the district

court's order, the court did not order the Board to

amend its plan but Instead, ordered the Board to re

study this feature of the plan and report to the court

on or before December 31, 1965 (R- 85-86). The Board,

however, has not reported to the court.

- 3 -

Assignments and transfers under the plan are

to be processed and determined by the Board pursuant

to its regulations so far as is practicable (R. +̂3-

46), The Board’s regulations provide that the parent

of an applicant must appear in person at the office

of the Superintendent to obtain an application form

which, when received by the Superintendent, will be

reviewed by the Board (R, 254, 260), Before the

transfer application will be granted, the regulations

require the applicant to be evaluated in light of

2 Jthe criteria of the Alabama Pupil Placement Law

(R, 254, 259-60, 261-62),

Students who do not apply for transfer or

whose transfers are denied remain assigned to the

schools to which they are presently assigned or are

assigned to schools in accordance with the custom

and practice that prevailed in the school system

prior to the institution of this suit (R, 45-46),

Students entering the Bessemer school system

for the first time who wish to attend a school the

majority of whose students are of a race different

2/ Title 52, section 61(4) of the Code of Alabama,

T540, (Recompiled 1958),

- 4 -

from the applicant may obtain applications from the

school of their choice which arc, after completion,

processed by the Superintendent (R, 83),

The plan contains no section requiring the

Board, for the school years 1966-1967 and 1967-1968,

to notify the public and students eligible to

exercise rights under it of its provisions.

- 5 -

SPECIFICATION OF ERROR

A.

B.

The district court erred by entering an order

approving a school desegregation plan which;

Retains racial assignments of students

in grades purportedly desegregated.

Falls to provide specific standards,

procedures, and notice for the exercise

by students of the right to attend

desegregated schools,

C. Fails to contain provisions designed

to eliminate the inferiority of schools

traditionally attended by Negroes,

Fails to contain a provision designed to

eliminate the racial segregation of

faculty and staff.

Fails to guarantee to students who

transfer that there will be no racial

discrimination or segregation in

services, activities and programs

provided, sponsored by or affiliated with

the school system, and

D.

E.

- 6 -

F. Falls to contain a provision allowing

Negro students in non-desegregated

grades to transfer to schools from

which they have been excluded because

of race.

- 7 -

ARGUMENT

A. The plan retains racial assignments of students

in grades purportedly desegregated

1. The court below found that a dual school

system existed in Bessemer in which students had

been assigned to schools on the basis of race

(R. 38-39). It is essential, if a school desegregation

plan is to conform to the requirements of the Fourteenth

Amendment, that it abolish the racial assignment of

students in desegregated grades. The plan approved by

the district court, however, simply provides that

students in desegregated grades may apply for transfer

to a school previously attended by students of another

race and that, except where such application is made

and accepted, "all pupils in all grades of the Bessemer

System will remain assigned to schools to which they

are assigned or will be assigned to schools in accordance

with the custom and practice for assignment prior to

the entry of the judgment of the district court in this

case . . . . " (R. 45-46). In addition, the plan fails

to abolish the racial assignment of children not yet

in school by providing that Negro children entering the

- 8 -

first grade are to report to Negro schools and white

children entering the first grade are to report to

white schools, and that "upon such registration, an

application may be made by the parents for the

child's assignment to any school (whether formerly

attended by white children or only by Negro children)"

(R. 47).

In short, the plan retains the dual school system

based on race and places the burden of transfer on Negro

students in allegedly desegregated grades to leave the

Negro schools to which they were assigned. It violates

the Fourteenth Amendment because it retains the dual

school system (Brown v. Board Of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954). Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County,

342 F. 2d 225, 228 (C.A. 5, 1964)) and fails to provide

a non-racial basis for assignment of students in

desegregated grades who fail to apply for transfer

(Kemp V. Beasley, 352 F. 2d l4, 22 (C.A. 8, I965)).

2. The plan is further defective because it permits

Negro students who wish to attend a school previously

attended solely by white students to do so only after

filing applications "in accordance with regulations of

the Board" (R. 43-45); this requirement is not imposed

on white students already attending such schools who wish

- 9 -

to remain there. The regulations provide that

the parent of an applicant must appear in person

at the office of the Superintendent to obtain an

application form which, when received by the

Superintendent, will be reviewed by the Board

(R, 25U, 260). Before the transfer application

may be granted, the regulations require the appli

cant to be evaluated in light of the criteria

contained in the Alabama Pupil Placement Law.

(R. 25U, 259-60, 261-62). The imposition on

Negroes wishing to attend white schools of any

requirement not applied to white students attending

those schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment. Bush

V. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F.2d 491 (C.A. 5,

1962); Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, 304

F.2d 118, 123 (C.A. 4, 1962); Northcross v. Board of

Education of City of Memphis, 302 F.2d 818 (C.A. 6)

cert. den. 370 U.S. 944 (1962); Norwood v. Tucker,

287 F.2d 798 (C.A. 8, 1961).

/ Title 52, Section 61(4) of the Code of Alabama,

40 (Recompiled 1958).

- 10 -

3. The Boardj in submitting a plan, as it was

entitled to do, elected to employ a method by which

the choice of schools was, at least on the surface,

to be made by the students. But the Board submitted

and the court approved nothing more than a transfer

plan superimposed on a system of racial assignments.

To be free of racial discrimination, a free choice

plan must provide at the very minimum: (1) that all

students in desegregated grades be given an opportunity

to exercise a choice of schools (Bradley v. School Board,

Richmond, Va., 3^5 F- 2d 310 (C.A. 4, 1965)5 vacated and

remanded 382 U.S. 103 (I965); Revised Statement, 45 CFR

18 1.4"^^ (2) that where the number of applicants apply

ing to a school exceeds available space, preferences

will be determined by a uniform non-racial standard

(Stell V. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education, 333

F. 2d 55, 65 (C.A. 5, 1964)j Revised Statement, 45 CFR

18 1.49)j and (3) that where a student does not exercise

his choice, he will be assigned to a school under a uniform

non-racial standard (Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d l4, 22 (C.A,

8, 1965); Revised Statement, 45 CFR l8l.45). The Bessemer

plan fails to meet any of these standards.

Jt/ The Department of Health, Education and Welfare recently announced new school desegregation guidelines.

31 Fed. Reg. 5623-34, April 9, 196b. They are cited as

Revised Statement and appear in an attachment to this

brief.

- 11 -

B, The plan fails to provide specific standards,

procedures, and notice £or the exercise by

students of the right to attend desegregated

school^

The plan fails to specify how or where

applications for transfer can be obtained, what

information must be placed on the forms, who may

execute the forms, what criteria will be applied

in ruling on applications, or the method of

assigning students whose transfers are denied.

In addition, the plan is silent as to the rights

of non-residents attending school xn Bessemer.

Specificity in free choice plans is

particularly important. Without a description

of the procedures to be utilized by Negroes

seeking to extricate themselves from Negro

schools, or the standards to be applied to

applicants, both white and Negro, exercising

their right to choose their school, neither the

court nor the parties can determine if the

choice afforded by the Board will be truly free.

If objections are to be made to the manner in

5 / The Bessemer system serves some non

residents .

- 12 -

which the Board administers the plan, they will

have to wait until the plan is in actual opera

tion. This means that the right of Negro children

to be admitted to public schools without regard

to race or color might be further postponed.

Moreover, omitting basic information from

the plan can only result in students and their

parents being inadequately notified of their

rights under the plan and of the manner in which

_6_/such rights may be exercised. If a free choice

plan is to live up to the standards announced by

this Court, it must give students entitled to a

choice of schools a clear opportunity to exercise

that choice. Stell v. Savannah Chatham County

Board of Education, 333 F.2d 55 (C.A. 5, 19o4).

6/ The plan contains no notice provisions

for the school years following 1965-66.

- 13 -

It cannot do this without spelling out the

procedures under which Negro students are to

seek reassignment to desegregated schools and

without notifying the students and their parents

z_/of such procedures. See the Revised Statement,

45 CFR 18 1.42-18 1.53.

7 / For example, for the 1965-86 school year

with a total enrollment of approximately 2920

white students and 5284 Negro students, 13 Negro students attend schools with white students

See the Affidavit attached to the Memorandum in

Support of the Motion to Consolidate and Expedite

Appeals filed by the United States in this case.

- 14 -

c. The Plan fails to contain provisions designed

to eliminate the inferiority of schools

traditionally attended by Negroes.

In the court below the Government introduced evi

dence and statistical tables showing that the facilities,

curricula and pupil-teacher ratios in some Negro schools

were markedly inferior to tlxose in all white schools (R.

133-145; 152-153; 166-168; 187-194; 218-235; Intervenor's

Exhibits 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 15; PI. Ebc. 21).

An expert on school facilities examined all .schools

in the system and rated them on a uniform scale of 100 points

(R. 187-202). His ratings averaged 71 points for white school

facilities and 50 points for Negro school facilities (R.

193-194). Although there are no white students in

Bessemer attending schools in frame structures, (R. 139),

Negro children in two schools are housed in frame

structures (R. 139-142). In one such structure some

classrooms are divided by partitions that go three-

quarters of the way to the ceiling (R. 140). Some Negro

students have classes in rooms lit by bare bulbs suspended

from the ceiling (R. 140, 142) and heated by coal stoves

(R, 142; Intervenor’s Exhibits 4, 14, 15), The statisti

cal tables attached to this brief show other measures

of the inferiority of the Negro schools in Bessemer.

This evidence, we believe, demonstrates the

need for relief that will equalize the educational

facilities traditionally attended by Negroes. Although

- 15 -

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), required th^t

school boards move to eliminate the segregation of schools

and to that extent repudiated the "separate but equal" doctrine,

it did not remove the constitutional obligation of the school

boards, during the transition period, to provide Negroes with

an education equal to that provided white children. Thus,

in Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, Civil Action

No. 2072N (M.D. Ala., March 22, 1966), Judge Johnson ordered

the Board to close seven inferior Negro schools before September

1966 and 14 more such schools by September 1967. He further

ordered the Board to provide remedial education to eliminate the

effects of .past discrimination. In Baird v, Benton County

Board of Education, Civil Action No. 6531 (N.D. Miss., August 3,

1965), Judge Clayton ordered the Board to provide uniform

curricula and to equalize per pupil expenditures of comparable

grade levels. And in Carroll v. Bolivar County Board of

Education, Civil Action No. 6531 (N.D. Miss., August 27, 1965),

he granted similar relief ordering the Board not only to

provide uniform curricula and equal per pupil expenditures at

comparable grade levels but also to maintain teacher-pupil

ratios at substantially the same levels for comparable grades.

In Anderson v. Canton Municipal Separate School District, Civil

Action No. 3700 (J) (C) (S.D, Miss., August 5, 1965), Judge

Cox ordered the Board to install adequate flush type toilet

- 16 -

± yfacilities in an ill-equipped Negro school. See also,

United States v. Carroll County Board of Education, Civil

Action No. GC 6541 (N.D. Miss., January 20, 1966).

It is particularly important when the Board chooses

to desegregate under a plan which depends upon students

choosing their schools that the schools available in the

system be substantially equal. The continuing inferiority

of schools traditionally attended by Negroes perpetuates the

racial identity of those schools. If the dual system is

to be completely abolished, inferior schools which are

readily identifiable as Negro schools must be eliminated.

8 / Subsequently, Judge Cox modified his order, upon the motion

of the Board and the stipulation of the plaintiffs, by allowing

the Board to close the ill-equipped school and move the children

into another plant (Order of August 21, 1965).

- 17 -

D , The plan fails to contain a provisiondesigned to eliminate the racial segre

gation of faculty and staff.

The inclusion of a provision in the plan designed

to eliminate race as a factor in the emplo5mient and alloca-

tion of faculty and staff at this late date is essential.

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

355 F. 2d 865 (C.A. 5, 1966); Bradley v. School Board,

Richmond. Virginia, 382 U.S. 103 (1965); Rogers v.

Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965). As the Court wrote in

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

supra at 870;

In view of the necessity ttiat the Jackson

School system be totally desegregated by

September 1967, we regard it as essential

that the plan provide an adequate start

toward elimination of race as a basis for

the employment and allocation of teachers,

administrators, and other personnel.

A desegregation plan, if it is to comply with

the rule announced in Singleton v, Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, supra, must (1) require the

Board to cease its practice of hiring and placing

teachers on the basis of race and (2) define a program

designed to correct the effects of past discriminatory

9/ The district court found that the Board staffed

"schools by assigning white personnel to white schools

and Negro personnel to Negro schools (R.39), but denied relief even though the Superintendent testified that the

non-racial assignment of new teachers would be feasible

(R. 121).

- 18 -

IQ_/ See the Revisedhiring and assignment practices.

Statement 45 CFR 181.13.

Where a school board is operating under a plan

utilizing a freedom of choice (or transfer) method, the

desegregation of faculty and staff is particularly

important. As the district court said in Kier v.

County School Board of Augusta County, Virginia, 249

F. Supp. at 246 (W.D. Va. 1966):

It is not enough to open the

previously all-white schools to

Negro students who desire to go there while all-Negro schools con

tinue to be maintained as such.

Inevitably, Negro children will

be encouraged to remain in ’’their

school," built for Negroes and

maintained for Negroes with all Negro teachers and administrative

personnel, ii/ See Bradley v.

School Bd., 345 F. 2d at 324

(dissenting opinion). This

encouragement may be subtle but

it is nonetheless discriminatory.The duty rests with the School Board to overcome the discrimi

nation of the past, and the long established image of the long

established image of the "Negro

school" can be overcome under freedom of choice only by the presence

of an integrated faculty.

10/ As the Court said in United States v. Duke, 332 F. 2d

739, 768-69 (C.A. 5, 1964):

An appropriate remedy ... should undo the

results of past discrimination as well as pre

vent future inequality of treatment. A court

of equity is not powerless to eradicate the

effects of former discrimination,

11/ By maintaining a segregated or substantially segregated

faculties and staffs, the board has, in effect, labeled its

schools "white" and "Negro." Brown v. County School Board of Frederick County, Virginia, 24b F. Suppi b46, bbO (W,u, va,,

1965); cf. Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750 (C.A, 5, 1961),

E ̂ The plan fails to guarantee to students who

transfer that there will be no racial dis

crimination or segregation in servxces,

activities, and programs, provided, sponsored

by or affiliated with the school system^

The plan is silent as to the elimination of racial

discrimination in services, activities and programs

sponsored by or affiliated with the school to which

Negro students may transfer. Valid plans must guarantee

the absence of racial discrimination or segregation in

connection with all programs related to the student's

12/attendance. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 355 F.2d 865, 870 (C.A. 5, 1966); Revised

Statement, 45 GFR 181.14. This is particularly true under

a freedom of choice (or transfer) system for any such dis

crimination or segregation would inevitably inhibit free

choice.

It is essential, therefore, that the plan specifies

the availability of all activities, services and programs

on a nonracial basis and provide that any disqualifica

tions or waiting period which might otherwise apply to

newly enrolled students will not apply to students

exercising their right to obtain a desegregated educa

tion. Revised Statement, 45 CFR 181.14 (b)(1).

12/ Indeed, before Brown, where the state provided one

school for both races, it was prohibited from discriminating

on the basis of race in connection with the school services,

facilities and programs. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents,

339 U.S. 637 (1950).

- 20 -

F . The plan fails to contain a provision

allowing Negro students in non-desegregated

grades to transfer to schools from which

they have been excluded because of race.

In Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 355 F. 2d 865, 869 (C.A. 5, 1966),

the Court wrote:

The school children in still-segregated

grades in Negro schools are there by assign

ment based on their race. This assignment

was unconstitutional. They have an absolute

right, as individuals, to transfer to schools

from which they were excluded because of

their race.

It is true that this Singleton decision was

rendered after the order of the district court in this

case was issued. But, since the Singleton transfer rule

is based on a constitutional principle, and is not merely

an aspect of transitional relief, it should have been

included in the plan. In any event, it is, of course,

proper for this Court now to require its inclusion in

the plan.

- 21 -

RELIEF

In Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 3^8 F. 2d ?29 (C.A. 5, 1965), this

Court said that "The time has come for foot dragging

public school boards to move with celerity toward de

segregation," The Court also said (3^8 F. 2d at 731)

We attach great weight to the standards

established by the Office of Education.

The Judiciary has of course functions

and duties distinct from those of the

executive department, but In carrying

out a national policy we have the same

objective. There should be a close

correlation, therefore, between the

Judiciary's standards In enforcing the

national policy requiring desegregation

of public schools and the executive

department's standards In administering

this policy. Absent legal questions, the

United States Office of Education Is better qualified than the courts and is the

more appropriate federal body to weigh administrative difficulties inherent in

school desegregation plans.

If in some district courts Judicial guides

for approval of a school desegregation

plan are more, acceptable to the community

or substantially less burdensome than H.E.W. guides, school boards may turn to the federal

courts as a means of circumventing the H.E.W.

requirements for financial aid. Instead of a

uniform policy relatively easy to administer, both the courts and the Office of Education

would have to struggle with Individual

- 22 -

school systems on an ad hoc basis. If

Judicial standards are lower, recalcitrant

school boards in effect will receive a

premimum for recalcitrance; the more the

intransigence, the bigger the bonus.

The Court emphasized that (3^8 F* 2d at 731)*

"As to details of the plan, the Board should be guided

by the standards and policies anno\inced by the United

States Office of Education in establishing standards

for compliance with the requirements of Title VT of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964."

In Price v. Denison Independent School District,

348 P. 2d 1010, 1013-14 (C.A. 5, 1965), this Court re

peated its language in Singleton regarding the weight

to be given the standards of the Office of Education

and then went on to say:

More than that, we put these standards to work. To avoid the temptation to recalci

trant or reluctant school systems to seek

Judicial approval of a token plan as the

basis for Federal aid under alternative

(1) for court plans, the Court held the Jackson plan inadequate and directed that

a plan modeled after the Commissioner of Education's requirements (note 11, supra)

be submitted for the fall of I965-66.

This signals what will be a frequent approach

to these cases as they.come to District Courts

and thereafter this Court. These executive standards, perhaps long overdue, are welcome.

To many, both on and off the bench, there was great anxiety in two major respects with the

Brown approach. The first was that probably

for The one and only time in American

- 23

constitutional history, a citizen --

was compelled to postpone the day of

effective enjoyment of a constitutional

right. In Ross v. Dyer, 5 Cir., 1963^

312 F. 2d I'̂ TI 194, we recognized that

under "a stair-step plan Negroes not in

the eligible classes continue to suffer

discriminatory treatment." That there

can be a moratorium on the enjoyment of

such rights runs counter to our notions

of ordered liberty. Second, this in

escapably puts the Federal Judge in the

middle of school administrative problems

for which he was not equipped and tended to

dilute local responsibility for the highly

local governmental function of running

a community's school under law and in .

keeping with the Constitution.

By the 1964 Act and the action of HEW, administration is largely where it ought

to be--in the hands of the Executive and

its agencies with the function of the

Judiciary confined to those rare cases

presenting justiciable, not operational

questions.

The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in

Kemp V. Beasley, 352 F. 2d l4 (C.A. 8, 1965), discussed

this Court's ruling in Singleton insofar as it relates

to reliance upon the H.E.W. guidelines. While agreeing

"that these standards must be heavily relied upon to

determine what desegregation plans effectively eliminate

discrimination," the Court of Appeals for that circuit

equally emphasized the responsibility of a federal court

to exercise its own judgment in determining constitutional

issues." The court states its conclusion as follows,

(352 F. 2d at 1 9):

- 24 -

Therefore, to the end of promoting

a degree of uniformity and discouraging

reluctant school boards from reaping a

benefit from their reluctance the courts

should endeavor to model their standards

after those promulgated by the executive.

They are not bound, however, and when

circvimstances dictate, the courts may

require something more, less or different

from the H.E.W. guidelines.

Although the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit has not had occasion to consider the effect

of the H.E.W. standards, district courts in that

circuit have relied on them. See Kj.er v. County

School Board of Augusta County, 2k9 P. Supp. 239

(W.D. Va., 1966)3 Wright v. County School Board of

Greenville County, Civil Action No. U263 (E.D. Va.,

January 27, 1966)3 Miller v. Clarendon County School

District No. 2, Civil Action No. 8752 (D. of S.C.,

April 21, 1966). In Miller, the most recent of these

cases, the District Court for the District of South

Carolina said, with reference to the H.E.W. standards:

Those standards have been adopted and approved generally in other forums in

this circuit [citing Kler and Wright].The orderly progress of desegregation

is best served if school systems de

segregating under court order are re

quired to meet the minimum standards promulgated for systems that desegregate

voluntarily. Without directing absolute adherence to the "Revised Standards"

guidelines at this Juncture, this court

will welcome their inclusion in any new,

amended, or substitute plan which may be

adopted and submitted.

- 25 -

This case, as well as each of the other school

desegregation cases now before this Court, illustrate

the need for this Court to review present judicial

enforcement methods to the end that the orderly transi

tion to desegregation can be accomplished with a minimum

of expenditure of judicial energy and with a maximum

correlation between current desegregation standards and

current desegregation practices. We suggest that this

end can best be realized by the adoption of a specific

decree to be entered in these cases by the district

courts. This is neither a fundamental change in

judicial approach nor a departure from established

standards for desegregation. It would place in the

courts, as it must under our constitutional system the

primary responsibility for declaring the rights of the

parties, and it would look to the Office of.Education,

rather than to the school boards, for administrative

guidelines affecting desegregation so that (1) the

court will not be "in the middle of school administra

tive problems," (2) uniformity in solving operational

problems may be achieved, and (3) an efficient method

of supervising school board performance can be realized.

This Court in cases involving voter discrimination

has approved the same type of relief here being urged.

- 27 -

See United States v. Ward 3^9 F* 2d 795 (C.A. 5̂ 19^5

and Unite(^States v. P a l m e r ___F. 2 d ____C.A. 5,

(No. 21646, decided February 8, 1966). In the Ward

case the Court in adopting the former decision there

proposed (349 F. 2d at 805) said:

[G]ood administration suggests that the

proposed decree be indicated by an

Appendix, not because of any apprehension

that the conscientious District Judge

would not faithfully impose every condition

so obviously implied, but rather because of factors bearing upon administration itself.

It is, not possible, or even desirable, of

course to achieve absolute uniformity.

But in this ever growing class of cases which have their genesis in unconstitutional

lack of uniformity as between races, courts

within this single circuit should achieve a relative uniformity without further delay.

Similarly in a recent decision involving jury discrimination

this Court has emphasized "the desirability of achieving

uniformity of the handling of the substantial number of

cases arising in this Court dealing with the same

questions of law." Scott v. Walker, ___ F. 2d _____

(C.A. 5, No. 208i4 decided March 31, I966).

The necessary function of the court in desegregation

cases is to guarantee that methods adopted for de

segregation do not fall below constitutional limits.

It is not necessary to this function that the courts

define every administrative detail necessarily involved

- 28 -

in day-to-day school administration. Under Title VT

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 the Executive Branch

of the federal government must guarantee the fair use

of federal funds hy prescribing the ordinary administra

tive details inevitably involved in any workable de

segregation plan. For the courts to look to the

regulations and guidelines of the Office of Education

does not involve the abdication of any Judicial function,

but instead is a rational method of enforcement of law

under a uniform national policy.

Those regulations and guidelines are the product

of the expertise of the Office of Education. They reflect

the experience and knowledge of persons involved in the

day-to-day administration of the schools. The courts do

not have the staff, the facilities, or the time to under

take with the same precision the function of defining the

workings of the desegregation mechanism.

With these considerations in mind we submit

to the Court the proposed decree set forth in the

appendix filed in connection with this brief and the

- 29 -

six other school desegregation cases before this

Court to which the government is a party. The

substantive requirements of the proposed decree

derive from the Fourteenth Amendment and the

I

decisions of the courts. The administrative

details are largely drawn from the Guidelines. j y

1V Recent court-approved plans which draw on the new

guidelines are; Carr. United States v. Morrtg^r^ojmty

Board of Education, Civil Action Wo. 2072-N (k.D. Ala., ̂

TErdh"?2TTg56^T ree. United States v. Macon County _Bga^

of Education, Civil Action Wo. 6o4-E (M.D. ^

1966) (entered by consent); Harris, J • Bu^ock

Countv Board of Education, Civil Action iJo. 2C73-NATa7; MarCmi, 1900) (entered by consent); United Stat^

V. Lowndes County Board of Educatiqri, Civil Actipn No.232ti-N (M.D. Ala., February il, l^SS) (entered by consent);

McGhee, United States v. Nashville Special School Dis^i£t No. 1, CivillTc^tTornio. 962 (W.D. Ark., March 3, lyob) f n̂te-red by consent); Becket t , United States v. School Board

of the city of Norfolk .Virginia, civi± aculon No. 2214

(W.D. Va;,^^cTTT7, T cM.ller V. Clarendon County School District No. 2, D.C.S.O.,

TTIvnrAction 'No. 0762 decided April 'di, lyoo.

- 30 -

We have urged that thia Court direct the dis

trict courts in these seven cases to enter a specific

decree along the line proposed herein. The records

in these cases fully support such relief. With the

use of this method of iadividual enforcement there

will no longer be occasion for the periodic submis

sion by school boards of "desegregation plans," the

hearing of objections to the plans and the submis

sion of amended plans. Instead, the school boards

will clearly understand thair obligations, and will

report to the court on a periodic basis. It may be

that supplementary enforcement proceedings will

occasionally be necessary, but hearings should be

less frequent and should produce more effective

results in bringing c'lrrent practices and current

standards closer. There will also be a higher prob

ability that desegregation will proceed more uniformly

among school districts tmder court orders and between

such school districts and those desegregating on a

voluntary basis under the supervision of the Office

of Education.

The courts would continue to have the final

responsibility for fixing constitutional standards

and for compliance with its decrees. The option is

- 31 -

still open to any school board to come into court to

prove that extraordinary circumstances compel modi

fication of one or another of the provisions of the

decree. The private plaintiffs and the United States

also retain their right, as they must, under our con

stitutional system and Title IV of the Civil Rights

Act of 196U, to come into cotirt when necessary to

seek modification of or compliance with any provision

in the decree.

Special mention should be made of the faculty

provisions in the proposed decree and of the district

covirt decisions that have decreed specific and

detailed relief on this subject.

Principally within the past year, district

courts have been grappling with the problem of fram

ing practical and effective relief for the desegrega

tion of faculty. Some courts in framing their decrees

have focused upon the specific results to be reached

by reassignment of teachers who had theretofore been

assigned solely upon the basis of their race. Dowc_U

V. School Board of Oklahoma City, 2Uk P. Supp. 971

(W.D. Okla. 1965). Kier v. County School Board of

Augusta County. Virginiat 2^9 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va.

- 32 -

1966). The orders entered in these cases required

that the defendant school boards assign any employed

teachers and reassign already-employed faculty sc

that the proportion of each race assigned to teach

in each school will be the same as the proportion

of teachers of that race in total teaching staff in

the system, or at least, of the particular school

level in which they are employed. This type of re

lief is justified on the ground that if faculty

members had in the past been assigned without regard

to race stich assignments would, as a matter of

mathematical probability, have yielded this same

result.

Other district courts in framing their decrees

on faculty desegregation have not been specific as

to the number of teachers of each race that should

be assigned to each school in order to remove the

effects of past discriminatory assignments. These

courts have focused upon the mechanics to be followed

in removing the effect of past discrimination rather

than upon the result as such. Thus, in Becket_t v.

School Board of the City of Norfolk, Civil Action

No. 221U (E.D. Va., 1966); Gilliam v. School Board

- 33 -

of the City_of_Hopej<ellt Vtrgini^j Civil Action No.

355U (E.D. Va, 1966); and Bradley v. School Board

of City of Richmond. Civil Action No, 3353 (E.D, Va.

1966), the courts approved consent decrees setting

forth in detail the considerations that would control

the school administrators in filling faculty vacan

cies and in transferring already-employed faculty^

members in order to facilitate faculty integration.

1^/ The faculty provisions in the HopeweU^^se,

v^ch were filed with the district court on April 8,

1966, read as follows:

The School Board of the City of Norfolk

recognizes its responsibility to employ,

assign, promote and discharge teachers

and other professional personnel of the

Norfolk City Public School System without

regard to race or color. It further recognizes its obligation to take all reasonable steps to eliminate existing

racial segregation of faculty that has

resulted from the past operation of a

dual school system based upon race or

color:

In order to carry out these responsi

bilities, the School Board has adopted

the following program:

1, Teachers and other professional

personnel will be employed solely on the

basis of qualifications and without

regard to race or color.

(Cont. on following page.)

- 3 k -

In yet other cases» the district court, while

emphasizing the necessity of affirmative steps to

undo the effects of past racial assignments of

faculty and while requiring some tangible results,

14 / (Gont. from preceding page.)

2. In the recruitment and employment

of teachers and other professional per

sonnel, all applicants and other prospective employees will be informed

that the City of Norfolk operates a racially integrated school system and

that the teachers and other professional

personnel in the System are subject to

assignment in the best interest of the

System and without regard to their race

or color.

3. The Superintendent of Schools

and his staff will take affirmative steps

to solicit and encourage teachers

presently employed in the System to accept transfers to schools in which the

majority of the faculty members are of a race different from that of the teacher to be transferred. Such transfers will

be made by the Superintendent and his staff in all cases in which the teachers

are qualified and suitable, apart from

race or color, for the positions to

which they are to be transferred.

4. In filling faculty vacancies which

occur prior to the opening of each school

year, presently employed teachers of the

race opposite the race that is in the

majority in the faculty at the school

(Cont. on following page.)

- 35 -

has not been specific either regarding the mechanics

or the specific results to be achieved. Sec Harri^

V, Bullock County Board of Educationt Civil Action

No, 2073-N (M.D. Ala. 1966); United States v. Lpwn^^

Board of Education. Civil Action No. 2328-N (M.D.

Ala. 1966); Carr v. Montgomery County Board of

I k / (Cont. from preceding page.)

where the vacancy exists at the time of the vacancy wxll be preferred in filling

such vacancy. Any such vacancy^wxll be

filled by a teacher whose race is the

same as the race of the majority on the

faculty only if no qualified and suxt—

able teacher of the opposite race xs

available for transfer from within the

System.

5, Newly employed teachers will be

assigned to schools without regard to

their race or coior» provided^ that if there is more than one newly employed

teacher who is qualified and suitable

for a particular position and^the race

of one of these teachers is different

from the race of the majority of the

teachers on the faculty where the

vacancy exists, such teacher wxll be assigned to the vacancy in preference

to one whose race is the same.

- 36 -

15/

ESdxicat^n, Civil Action No, 2072-N (M.D, Ala, 196^,

In the Monteomery case the court’s decree con

tained the following provisions on faculty desegregation

Race or color will henceforth not be a

factor in the hiring, assignment, reassign

ment, promotion, demotion, or dismissal of

teachers and other professional staff, with the exception that assignments shall

be made in order to eliminate the effects

of past discrimination. Teachers, prin

cipals, and staff members will be assigned

to schools so that the faculty and staff

is not composed of members of one race.

In the recruitment and employment of

teachers and other professional personnel,

all applicants or other prospective em

ployees will be informed that Montgomery

County operates a racially integrated

school system and that members of its

staff are subject to assignment in the

best interest of the system and without

regard to the race or color of the

particular employee.

The Superintendent of Schools and his

staff will take affirmative steps to solicit and encourage teachers presently

employed to accept transfers to schools

in which the majority of the faculty members are of a race different from that

of the teacher to be transferred.

Teachers and other professional staff

will not be dismissed, demoted, or passed

over for retention, promotion, or re

hiring on the ground of race or color.In any instance, where one or more teachers

-or other professional staff members are

to be displaced as a result of desegregation or school closings, they shall

(Cont, on following page,)

- 37 -

The proposed decree set forth in the appendix

Incliides a faculty provision in general terms. It

does not seem desirable for this Court to compel*

exact uniformity as to how faculty desegregation

should be accomplished in every school district

within the Fifth Circuit, The appellate court should

not prescribe a detailed faculty provision from

which a district court could not depart. District

courts should be free to add specifics to meet the

particular situation. By its decree, this Court will

only be recognizing that there may be differences

between large and small school districts and between

urban and rural school districts.

At the same time, the decree does require

that a reasonable beginning be made and that a

reasonable program be achieved in the actual desegre

gation of the faculty. The decree makes it clear

that the school officials are (1) restrained from

15/ (Cont. from preceding page.)

be transferred to any position in the

system where there is a vacancy for which

they are qiialifled.

- 38 -

practicing racial discrimination in the hiring and

assignment of new faculty members, and (2) are

required to take affirmative steps to correct exist

ing results of past racial assignments.

This, we believe, is the minimum to be re

quired in any school desegregation decree, "nie

district courts, however, would be open to the

plaintiff and to the United States to seek more

specific relief if the facts warrant it.

- 39 -

(INCLUSION

Deference to local responsibility for the

administration of school systems is a long established

principle in the law of school desegregation one

that continues to be valid today. However, we think

it disserves the principle of local responsibility

to place upon school boards the difficult and

technical task of articulating judicial standards

and formulating workable mechanics for free choice

plans. The result is too often an inadequate plan

which necessitates further abrasive involvement

of the federal courts in local school affairs.

Instead, we iirge the Court to make the legal obliga

tions of local officials as clear as possible and to

utilize the expertise of HEW in the formulation of

free choice mechanics. Local responsibility can then

be turned to the far more productive tasks of admin

istration and performance.

Respectfully submitted.

JOHN DOAR,Assistant Attorney General,

MACON L. WEAVER,United States Attorney,

ST. JOHN BARRETT,

DAVID L. NORMAN,

JOEL M. FINKELSTEIN,

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG,

CHARLES R. NESSON,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington. D. C. 20530

ATTACHMENT

This attachment consists of tables

which were presented to the Court below

as summaries of evidence showing the

disparity between the educational oppor

tunities afforded white and Negro students

in Bessemer.

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

Capacity and Enrollment Summaryj[[̂ /

SCHOOL

White

Bessemer High School Bessemer Jr. H. S.

Arlington Elementary

Jonesboro Elementary

Jonesboro AnnexSpecial Education

Vance Elementary

Westhills Elementary

TOTAL

CAPACITY ENROLLMENT NUMBER OF STUDENTS

800 652

Under

Caoacity

148

Over

Capacity

800 735 65

U50 405 45

480 420 60

100 87 13

75 44 31

300 268 32

180 185 5

3185 2796 394 5

389 - Net Available Places in White Schools

Negro

Abrams Elementary 600 626 26

Abrams Secondary 1050 1064 14

Carver Elementary 800 873 73

Carver Secondary 750 785 35

Special Education 15 11 4 29Dunbar Elementary 700 729 48Dunbar Secondary 250 202

Special Education 15 11 4 35Hard Elementary 600 635 26Hard Secondary 210 184

TOTAL 4990 5120 82 212

130 - Net Over-enrollment in Negro Schools.

259 - Net Available Places in Entire School System

Compiled from PI. Ex. #21, Special Report Prepared for the Super-

intendent-Bessemer Board of Education.

- 1-

ARTS

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

Electives Taught at

Public High SchoolsJ^/

Grades 10-12

BESSEMER CARVER

Band Band

Glee Club ChoirMusic

Art I

Art II

Art III Speech I

Speech IIPlay Production III

ABRAMS

Band

P.S. Music

LANGUAGE French I

French II

Spanish I

Spanish II

Spanish III

French French

MATHEa4ATICS

SCIENCE

Algebra I

Algebra II Plane Geometry

Plane Geometry II

General Math I

General Math II

General Math III

Business Math III

Plane and Solid Geo.

Trigonometry III

Algebra I

Algebra II Geometry

Business Math

Advanced Math

Algebra

Algebra II Geometry

General Math

Advanced Gen. Math.

Advanced Gen. Math.

Advanced Modern Math.

General Biology

C. P. Biology

Chemistry II

Physics III

Advanced Gen.

Biology

Chemistry

PhysicsPhysical Science

General Science

Science Advanced Gen.Sci.

Biology

Chemistry

Physics

Physical Science

Science

Adv.Gen.Sci.I

Adv.Gen.Sci.il

- 2 -

BESSEMER CARVER ABRAMS

HISTORY World History World History

Social Studies

World History

Social Studies

VOCATIONAL Diversified Occup^

Distributive Ed.

Home Econ. II

Home Econ. Ill

Library Science

Typing I

Typing II

Bookkeeping II Bookkeeping III

Shorthand I

Shorthand II

Shorthand III

Office Practice III

Auto Mechanics

Machine Shop

★★Diversified 0c._/

Home Econ.

Typing

Cosmetology

Electronics

Industrial Arts

Shoe Repair

Diversified Occup.

Home Econ.

Home Econ. Adv.

Library Science

Typing

Auto Mechanics

Printing

TailoringUpholstery

MISCELLANEOUS Reading Lab I

Reading Lab II

Reading Lab III

Student Council

^ Compiled from Intervenor’s Exhibit #7, Accreditation Application,

1964-65, for each school.

Information obtained from the records of the Superintendent of

Education of the City of Bessemer.

- 3 -

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

Pupil-Teacher Ratios^J^

SCHOOL PUPIL-TEACHER RATIO

White

Bessemer High School (10-12)

Bessemer Junior H. S, (7-9)

Arlington Elementary (1-6)

Jonesboro Elementary (1-5)

Jonesboro Annex (6)

Special Edxication

Vance Elementary (1-6)

Westhills Elementary (1-6)

23.3

2k,527.0

26.3

29.0

11.0 26.8

30.8

AVERAGE 2k,l*/

Negro

Abrams Elementary (1-6)

Abrams High School (7-12)

Carver Elementary (1-6)

Carver High School (7-12)

Special Education

Dunbar Elementary (1-6)

Dunbar Secondary (7-8)

Special Education

Hard Elementary (1-6)

Hard Secondary (7-8)

32.9

25.3

34.9

29.1

11.0

34.7

25.3

11.0

33.4

26.3

AVERAGE 30.1*/

V Information compiled from Special Report Prepared for

Superintendent, Bessemer Board of Eiducation, PI. Ex. #21,

- 4 -

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

Insured Valuation of Bessemer City School Buildings— /

SCHOOL VALUATION

White

Bessemer High School

Bessemer Junior H. S.

Arlington Elementary

Jonesboro Elementary

Jonesboro Annex

Vance Elementary Westhills Elementary

$ 986,824

657,643

197,227

520,275

109,605

166,500

99,000

TOTAL $2,737,074

Negro

Abrams High School

Abrams Elementary

Carver School

Dunbar School

Hard School

$452,500153,832

544,119

328,170

280,000

TOTAL $1,758,621

INSURED VALUATION PER PUPILicic /

White $978.92

Negro $345.43

* / Compiled from Intervenor's Elxhibit #8, Statement of Values

of Buildings and Contents, 1963.★★/ Based on enrollment given in Special Report Prepared for

Superintendent-Bessemer Board of Education, Pl.'s Ex. #21.

- 5 -

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

School Inventory Svanmary by Tsrpe of Equipment— ^

TYPE OF EQUIPMENT VALUATION PER PUPIL

V^ite Schools Negro Schools (2^96 students) (5120 students)

1. Furniture and Kitchen Equipment $39.79

2. Books, Maps Charts, etc. 28.30

3. Audio-Visual Eqiiipment 12.09

Machines, Tools, Vocational Equip. 22.35

5. Drapes, Curtains, Mats, Physical

Education Equipment 3.37

6. Music Equipment 3.13

7. Miscellaneous 5.03

$9.40

9.60

1.95

7.36

2.66

2.79

3.20

TOTAL $114.06 $36.96

*_/ Information compiled from School Inventory of Bessemer City

Schools, 1965, svnnmary sheet for each school. There is some

inconsistency in the method used by the schools for classify

ing their inventory into these seven categories.

- 6 -

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

School Inventory Summary by School Totals—* /

SCHOOL ESTIMATED VALUE VALUE PER PUPIL

White

Bessemer High School (10-12)

Bessemer Junior H. S. (7-9)

Arlington Elementary (1-6)

Jonesboro Elementary (1-5)

Jones Annex (6 & sp)

Vance Elementary (1-6)

Westhills Elementary (1-6)

$167,3W.60

58,702.40

17.836.50

42.794.50

13,177.00

8,761.00

10,304.25

$256.66

79.87

44.04

101.89

100.59

32.69

55.70

TOTAL $318,919.25 $114.06 V

Negro

Abrams High School (7-12) $68,603.82 $64.48Abrams Elementary (1-6) 5,748.81 9.18

Carver School (1-12) 64,029.36 38.36Ehanbar School (1-8) 30,895.90 32.80Hard School (1-8) 19,938.71 24.35

TOTAL $189,216.50 $169.17

* / Information compiled from School Inventory of Bessemer City

Schools, 1965, summary sheet for each school. Averages are

based on total number of students of each race in the system.

- 7 -

BESSEMER SCHOOL SYSTEM

Book - Pupil Ratio

SCHOOL NUMBER OF BOOKS ENROLLMENT BOOK-PUPIL RATIO

White

Bessemer High School 8785 652 13.5

Negro

Abrams High School 5799 1061+ 5.5

Carver High School 3975 785 5.1

/ Information obtained from Intervenor's Exhibit #7, Applica

tions for Accreditation; also Plaintiff's Exhibit #21,

Special Report Prepared for the Superintendent-Bessemer Board

of Education.

- 8 -

REVISED STATEMENT OF POLICIES

FOR SCHOOL DESEGREGATION PLANS

UNDER TITLE VI OF THE

CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964

M arch 1966

U .S . D E P A R T M E N T O F H EA LT H , E D U C A T IO N , A N D W ELFARE

O ffice o f Education

Subpart ¥ —Desegregation Plans Not Reaching All Grades for the 1966-67 School Year

§ 181.71 Opportunity to Transfer in Grades Not Reached

by Plan

In any school system in which, for the school year 1966-67, there are grades not yet reached by the desegregation plan, tlie school system must arrange for students to attend school on a desegregated basis in each of the special circumstances described in (a), (b), (c), and (d) below. This opportunity must be made available in such a way as to follow, to the maximum extent feasible, the desegregation procedures in grades generally reached by the plan, according to the type of plan in effect.(a) T r a n s fe r f o r a C o u rse o f S tu d y . A student must be permitted to transfer to a school in order to take a course of study for which he is qualified and which is not available in the school to which he would otherwise be assî ed on the basis of his race, color, or national origin.(b) T r a n s f e r to A t t e n d S c h o o l W i t h R e la t iv e . A student must be permitted to transfer in order to attend the same school or attendance center as a brother, sister, or other relative living in his household, if such relative is attending a school as a result of a desegregation plan and if such school or attendance center offers the grade which the student would be entering.(c) T r a n s fe r f o r S tu d e n ts R e q u ir e d T o G o

O u ts id e S y s te m . A student must be permitted to transfer to any school within the system which offers the grade he is to enter if he would otherwise be required to attend school outside the system on the basis of his race, color, or national origin.(d) T r a n s fe r f o r O th e r R e a so n s . A student must be permitted to transfer to a school other than the one to which he is assigned on the basis of his race, color, or national origin if he meets whatever requirements, other than race, color or national origin, the school system normally applies in permitting student transfers.

§ 181.72 Students New to the System

Each student who will be attending school in the system for the first time in the 1966-67 school year in any grade not yet generally reached by the desegregation plan must be assigned to school under the procedures for desegregation that are to be applied to that grade when it is generally reached by the desegregation plan.

§ 181.73 General Provisions Applicable

A student wdio has transferred to a school under § 181.71 above, or entered a school under § 181.72 above shall be entitled to the full benefits of § 181.14 above (relating to desegregation of services, facilities, activities and programs) and to any and all other rights, privileges, and benefits gener

ally conferred on students who attend a school by virtue of the provisions of the desegregation plan.

§ 181.74 Notice

Each school system in which there will be one or more grades not fully reached by the desegregation plan in the 1966-67 school year must add a paragraph describing the applicable transfer provisions at the end of the notice distributed and published pursuant to § 181.34 above or §§ 181.46 and 181.53 above, as is appropriate for the type of plan adopted by the school system. The text of the paragraph must be in a form prescribed by the Commissioner. The school system must make such other changes to the notice as may be necessary to make clear which students will be affected by attendance zone assignments or free choice requirements.In addition, for the letter to parents required in § 181.46, school systems with free choice plans which have not desegregated every grade must use a letter describing the plan and will enclose with the letter sent to parents of students in grades not desegregated a transfer application instead of a clioice form. For the letter to parents required in § 181.34, school systems with geographic zone plans must send to each parent of students in grades not desegregated a letter describing the plan and a transfer application. The text for these letters and the transfer application must be in a form prescribed by the Commissioner.

§ 181.75 Processing of Transfer Applications

Applications for transfer may be submitted on the transfer application form referred to in § 181.74 above or by any other wanting. If any transfer application is incomplete, incorrect or unclear in any respect, the school system must make eveiw reasonable effort to help the applicant perfect his application. Under plans based on geographic zones, and under plans based on free choice of schools, the provisions of § 181.42 as to whether a student or his parent may make a choice of school, shall also determine whether a student in a grade not yet generally reached by desegregation may execute a transfer application.

§ 181.76 Reports and Records

In each report to the Commissioner under §§ 181.18, 181.35, and 181.55 above, the school system must include all data, copies of materials distributed and other information generally required, relative to all students, regardless of whether or not their particular grades have been generally reached by the plan. Similarly the system must retain the records provided for under §§ 181.19, 181.35, and 181.55 above with respect to all students.

[§§ 181.77 through 181.80 reserved]

10

U S. G O V ERN M EN T PR IN TIN G O FF IC E : 1966 0 - 2 1 0 - 0 6 0

GEOGRAPHIC PLANS

TEXT FOR NOTICE TO BE PUBLISHED IN NEWSPAPERS, DISTRIBUTED

WITH LETTERS TO PARENTS, AND OTHERWISE MADE FREELY AVAIL

ABLE TO THE PUBLIC

(As required by § 181.34 of the Statement of Policies)

(School System Name and Office Address)

NOTICE OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION PLAN UNDER TITLE VI OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OF 1964

T H IS N O T IC E IS M ADE A V A ILA B LE TO IN F O R M YOU A BO U T T H E D E SE G R E G A T IO N O F O U R SCH O O LS. K E E P A

COPY O F T H IS N O T IC E . IT W IL L A N S W E R MANY Q U E ST IO N S A B O U T SCHOO L D E SE G R E G A T IO N .

1. D esegrega tion P la n in E f e c t

The_________________public school system is being desegregated under a plan adopted

(Name of school system)in accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The purpose of the desegregation plan is to eliminate from our school system the racial segregation of students and all other forms of discrimination based on race, color, or national origin. Your school board and the school staff will do everything they can to see to it that the rights of all students are protected and that our desegregation plan is carried out successfully.

2. N o n -R a c ia l A tten d a n c e Z on es

Under the desegregation plan, the school each student will attend depends on where he lives. An attendance zone has been established for each school in the system. All students in the same grade who live in the same zone will be assigned to the same school, regardless of their race, color, or national origin and regardless of which school they attend now.

3. T ra n sfe r to S ch oo l in A n o th er Z one

A student may transfer from the school to which he is assigned only under the following conditions:

[S ta te here the co n d itio n s , i f a n y , u n d e r w h ich tra n sfe r w i l l be g ra n ted . T h ey m u s t he co n s is ten t w ith the

tra n sfe r p r o v is io n s s ta ted in § 1 8 1 .3 3 o f the S ta tem en t o f P o lic ie s .] Transfers for any other reasons will not be permitted.

4. N o tif ic a tio n o f A s s ig n m e n t

On_________________the parent, or other adult person acting as parent, of each student

(Date)enrolled in this system will be sent a letter telling him the name and location of the school to which the student will be assigned for the coming school year. The letter will also give information on any school bus service provided for the student’s neighborhood. A copy of this notice will be enclosed with each letter. The same letter and notice will be sent out on the above date for all children the school system expects to enter the school system for the first time next year. This includes children entering first grade or kindergarten. [D elete “or kindergarten” i f n o t offered.] If the school system learns of a new student after the above date, it wall promptly send the student’s parent such a letter and a copy of this notice.

5. M a p s S h o w in g A tten d a n c e Z on esMaps showing the boundary lines of the attendance zones of every school in the school system are freely available for inspection by the public at the Superintendent’s office. Individual zone maps are available at each school.

6. R e v is io n o f A tte n d a n c e Z o n es B o u n d a r ie sAny revision of attendance zone boundaries will be announced by a prominent notice in a local paper at least 30 days before the change is effective.

7. A U O ther A s p e c ts o f Schools D esegrega ted

All school-connected services, facilities, athletics, activities and programs are open to each student on a desegregated basis. A student assigned to a new school under the provisions of the desegregation plan wall not be subject to any disqualification or w'aiting period for participation in activities and programs, including athletics, which might otherwise apply because he is a transfer student. All transportation furnished by the school system will also operate on a desegregated basis. Faculties will be de

segregated, and no staff member will lose his position because of race, color, or national origin. This includes any case where less staff is needed because schools are closed or enrollment is reduced.

8. A tten d a n c e A c ro s s School S y s te m L in e s

No arrangement will be made or permission granted by this school system for any students living in the community it serves to attend school in another school system, wmere this would tend to limit desegregation, or where the opportunity is not available to all students without regard to race, color, or national origin. No arrangement will be made or permission granted, by this school system for any students living in another school system to attend public school in this system, where this would tend to limit desegregation, or where the opportunity is not available to all students v\dthout regard to race, color, or national origin.

9. V io la tio n s T o B e R ep o rted

It is a violation of our desegregation plan for any school official or teacher to influence, threaten or coerce any person in connection with the exercise of any rights under this plan. It is also a violation of Federal regulations for any person to intimidate, threaten, coerce, retaliate or discriminate against any individual for the purpose of interfering with the desegregation of our school system. Any person having any knowled̂ of a^ violation of these prohibitions should report the facts immediately by mail or phone to the Equal Educational Opportunities Program, U.S. Office of Education, Washington, D.C., 20202 (telephone 202-962-0333). The name of any person reporting any violation will not be disclosed without his consent. Any other violation of the desegregation plan or other discrimination based on race, color, or national origin in the school system is also a violation of Federal requirements and should likewise be reported. Anyone with a complaint to report should first bring it to the attention of local school officials, unless he feels it would not be helpful to do so. If local officials do not correct the violation promptly, any person familiar with the facts of the violation should report them immediately to the U.S. Office of Education at the above address or phone number.

U .S . G O V E R N M E N T PR IN T IN G O FF IC E : I R M 0 — 2IO -O V7

FREE CHOICE PLANS

TEXT FOR NOTICE TO BE PUBLISHED IN NEWSPAPERS, DISTRIBUTED

WITH LETTERS TO PARENTS, AND OTHERWISE MADE FREELY

AVAILABLE TO THE PUBLIC

(Required by § 181.46 and 181.53 of the Statement of Policies)

(School System Name and Office Address)

NOTICE OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION PLAN UNDER TITLE VI OF THE CIVIL RIGHTS

ACT OF 1964

T H IS N O T IC E IS M .\D E A V A ILA B LE TO IN FO R M YOU A BO U T T H E D E SE G R E G A T IO N O F OUR SCHOO LS. K E E P A

COPY O F T H IS N O T IC E . IT W IL L A N SW ER MANY Q U E STIO N S A BO U T SCHOOL D E SE G R E G A T IO N

1. D eseg ra tio n P la n in E;ffect ̂ The________________ public school system is being desegregated under a plan adopted in