Marsh v The County School Board of Roanoke County Brief and Appendix for the Appellees

Public Court Documents

August 31, 1960

24 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Marsh v The County School Board of Roanoke County Brief and Appendix for the Appellees, 1960. 9d306b0e-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1191e5d2-faed-48bb-b901-2b35c92aa0f5/marsh-v-the-county-school-board-of-roanoke-county-brief-and-appendix-for-the-appellees. Accessed December 05, 2025.

Copied!

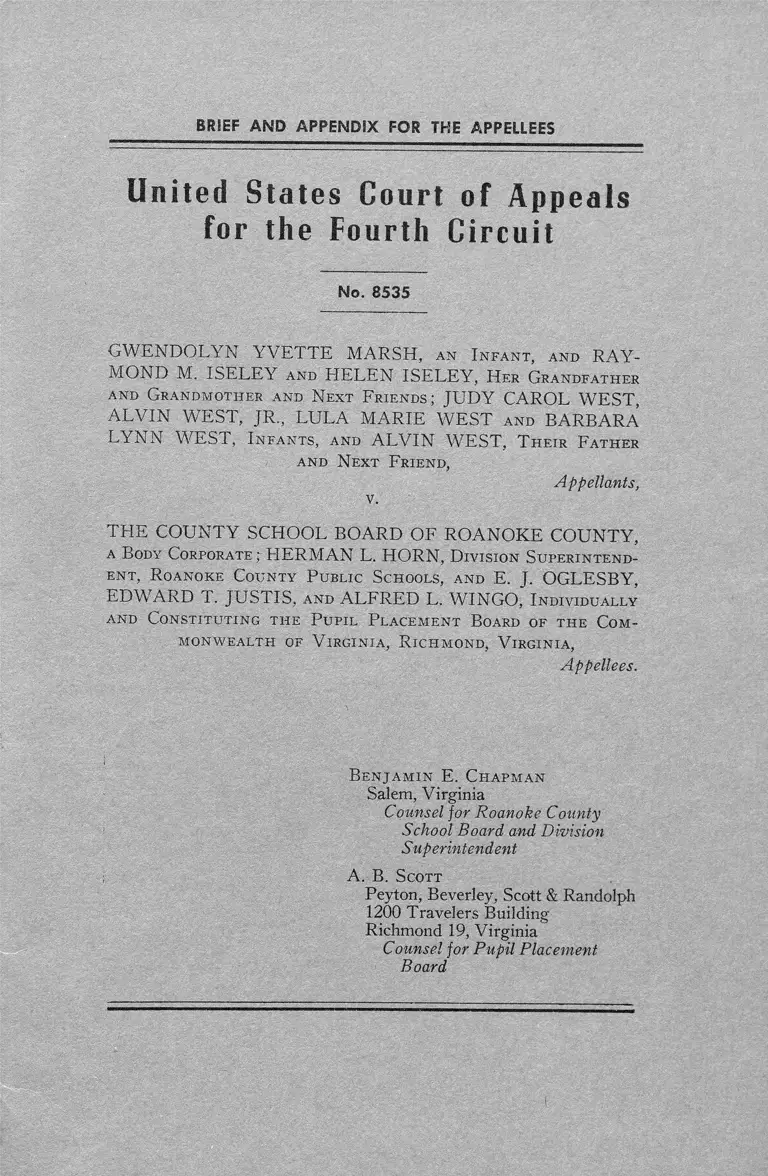

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR THE APPELLEES

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8535

GWENDOLYN YVETTE MARSH, an I n f a n t , a nd RAY

MOND M. ISELEY a nd HELEN ISELEY, H er Gra n d fa th er

and G ran d m o th er and N ext F r ie n d s ; JUDY CAROL WEST,

ALVIN WEST, JR., LULA MARIE WEST a nd BARBARA

LYNN WEST, I n f a n t s , and ALVIN WEST, T h e ir F a th er

and N ext F r ie n d ,

Appellants,

v.

THE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ROANOKE COUNTY,

a B ody Corporate ; HERMAN L. HORN, D iv isio n S u p e r in t e n d

e n t , R oanoke Co u n ty P u b lic S chools, a nd E. J. OGLESBY,

EDWARD f. JUSTIS, and ALFRED L. WINGO, I ndividually

and C o n s t it u t in g t h e P u p il P l a c em en t B oard of t h e Co m

m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia , R ic h m o n d , V ir g in ia ,

Appellees.

B e n j a m in E. C h a p m a n

Salem, Virginia

Counsel for Roanoke County

School Board, and Division

Superintendent

A. B. S cott

Peyton, Beverley, Scott & Randolph

1200 Travelers Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

Counsel for Pupil Placement

Board

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

P r e l im in a r y S t a t e m e n t ..... ................... ............................... ................... 1

No I ssue of D is c r im in a t io n ............ .......................................................... 2

T h e S ole I ssue ........................ 2

R easona blen ess and V a lid ity of S ix ty -D ay R u l e .................... 3

C er ta in S ta tem en ts of A p pella n ts D en ie d ................................... 4

C o n c lu sio n ................................. 5

A ppe n d ix :

Additional Exhibits from Record............... App. 1

Defendant’s Exhibit No. 2 .......... App. 1

Defendant’s Exhibit No. 1 ........................... App. 2

Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 2 ........................ .A pp. 3

Defendant’s Exhibit No. 1 .......................................... App. 4

Additional Excerpts by Appellees from Transcript......... App. 5

Testimony of Herman L. H orn................................... App. 5

Direct Examination________ App. S

Testimony of Ernest J. Oglesby................................. App. 10

Direct Examination................................................ App. 10

Cross-Examination ...... App. 13

Redirect Examination............................... App. 14

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 8535

GWENDOLYN YVETTE MARSH, an I n f a n t , and RAY

MOND M. ISELEY a nd HELEN ISELEY, H er Gra n d fa th er

and G r a n d m o th er and N ext F r ie n d s ; JUDY CAROL WEST,

ALVIN WEST, JR., LULA MARIE WEST and BARBARA

LYNN WEST, I n f a n t s , a nd ALVIN WEST, T h e ir F a th er

a nd N ext F r ie n d ,

Appellants,

v.

THE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF ROANOKE COUNTY,

A B ody Corporate ; HERMAN L. HORN, D iv isio n S u p e r in t e n d

e n t , R oanoke C o u n ty P ublic S chools, and E. J. OGLESBY,

EDWARD T. JUSTIS, and ALFRED L. WINGO, I ndividually

and C o n s t it u t in g t h e P u p il P la c em en t B oard of t h e Co m

m o n w e a l t h of V ir g in ia , R ic h m o n d , V ir g in ia ,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLEES

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

In order that the Court of Appeals might the more readily

have a more complete picture of the case, the original

exhibits consisting of the letter from local counsel for the

appellants to the Division Superintendent of Schools of

Roanoke County under date of July 16, 1960, and of the

letters from the Pupil Placement Board to each appellant

parent, dated August 30, 1960, as well as additional excerpts

from the transcript of the testimony of witnesses during the

trial below with suitable ties in, for continuity’s sake, to the

2

same pages of the transcript and evidence printed in the

appellants’ separate appendix, are printed in the appendix

to the appellees’ brief. Reference is made to the same since

the two should be read alongside and considered together at

the appropriate places.

NO ISSUE OF DISCRIMINATION

At the very outset, let it be emphasized that the opinion

and decision of the lower court speaks eloquently enough

for itself, and involves no question of discrimination. No

statement of the case, or of the pleadings, or of the ques

tions including any so-called subsidiary issues, or of the

facts, or extraneous arguments on behalf of the appellants

can change one whit the essential complexion of this case,

and to the extent inapplicable or irrelevant, as on only super

ficial analysis they clearly are, they should be disregarded

and put aside.

THE SOLE ISSUE

The sole, plain, and simple question here is whether the

appellants sought in timely manner assignment to a specific

school desired by them for the I960 school session, and as

a corollary thereto the reasonableness and validity of the

regulation requiring them so to do at least sixty (60) days

prior to the commencement of such session.

That they did not is clearly and firmly established by the

record. Indeed, this is undisputed. Such being the case,

no action of any nature was taken on the then pending

requests, but without prejudice, clearly expressed, to any

future rights. Since no action was taken, it necessarily

follows that there was not and could not have been any

discrimination.

3

REASONABLENESS AND VALIDITY OF

SIXTY-DAY RULE

We feel that it would in no small measure impugn if not

insult the knowledge and intelligence of this Court to labor

this point seriously or at great length. Suffice it to say that

in addition to what is a matter of common everyday knowl

edge, the late District Judge Thompson said in the Pulaski

County School case that “advance knowledge of the number

of students who expect to attend said Institute (Christians-

burg Institute) should be available to the school authorities

so that they may plan and make the necessary arrangements

for the operation of each school session”. He specified

March 15 as the dead line.

And District Judge Paul in the Grayson County School

Case said:

“* * * it is always desirable and frequently necessary

that the authorities charged with the maintenance of

the schools should have some knowledge prior to the

opening of the school year as to how many students

may be expected to attend school, in order that they

may be able to outline the proper school program and

to make the preparations of various sorts for accommo

dating the number of children that may be fairly expect

ed to attend”.

Judge Paul specified that application should be made “at a

reasonable time before the beginning of the school year”.

Local counsel for the appellants in this case from its incep

tion was also the only counsel for the plaintiffs in the Pulaski

and Grayson County School Cases above referred to and

also in the appeal hearings held by the Pupil Placement

Board at Pulaski prior to the trial of the Pulaski and

Grayson County cases.

4

CERTAIN STATEMENTS OF APPELLANTS

DENIED

It is with regret and extreme reluctance that counsel for

the appellees feel compelled, in justice to the respective clients

they represent, to assert that many of the positive state

ments made on behalf of the appellants in their brief are

not only frivolous. They are misleading, inaccurate, and in

some instances even false.

That local counsel for the appellants was not aware or

should not have been aware of the sixty-day rule simply

isn’t so! Even if it was, any such claim is immaterial.

There is ample and sufficient space on the application

form for the designation of a specific school that is desired.

That this is so is best illustrated by the fact that specific

schools were designated in this case and in the companion

case involving Roanoke City.

That the sixty-day rule is discriminatory and not appli

cable to all cases regardless of race, color, or creed, or school,

simply isn’t so! Its express terms are clear enough, and

there is no evidence in the record to the contrary. The only

exceptions are cases of change of residence in order not to

work an undue hardship, and cases of necessary moves in

large numbers or en masse, which are called administrative

transfers or removals, especially to cope with an emergency.

That the applications were filed on June 16, 1960 is not

true! They were received after July 16, 1960, and were in

fact considered in August at the first ensuing meeting of the

local school board, and promptly thereafter at the first meet

ing of the Pupil Placement Board immediately following

their actual receipt.

That the appellees made no reasonable effort to publicize

the sixty-day rule is unfounded and untrue. It was circu

5

lated throughout the state and, more importantly, given to

the newspapers and to the United Press and Associated

Press. It was widely run as a news article in newspapers

throughout the state. A news item is much more apt to be

seen, noticed and taken in, than some formal notice hidden

away in the classified section usually at the back of the paper.

That even if applications are filed in time, sufficient time

is not allowed to exhaust the administrative remedies is

shown to be false, as counsel for the appellants well know,

by the results of the Roanoke City appeal hearings for the

1961 school session in August of that year, and as a result

of which the Pupil Placement Board reversed itself in six

(6) of twelve (12) instances.

That the hearing procedure is burdensome and unreason

able because Richmond is far removed from certain sections

of the state is refuted by the testimony of the chairman of

the Pupil Placement Board that effort is made to suit the

greater public convenience by balancing the numbers and

distance involved in a specific case; and by the actual facts

that hearings were held in Pulaski concerning residents of

the Counties of Pulaski and Grayson, in Waynesboro as to

residents of that city, and in Roanoke concerning residents

of such city and the adjoining county of the same name.

That the building of the Pinkard school was designed as

an escape from the possible rights of these appellants is

disproved by the fact that it was planned and discussed long

before this action was instituted.

CONCLUSION

Further discussion simply confuses and gets away from

the one fundamental issue treated above. To the extent

necessary, however, reference can also be made to the

6

points made by the appellees in the preceding case involving

Roanoke City for the same school year of 1960.

We submit that the District Judge should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

B e n j a m in E. C h a p m a n

Salem, Virginia

Counsel for Roanoke County

School Board and Division

Superintendent

A. B. S cott

Peyton, Beverley, Scott & Randolph

1200 Travelers Building

Richmond 19, Virginia

Counsel for Pupil Placement

Board

A P P E N D I X

ADDITIONAL EXHIBITS FROM RECORD

Defendant’s Exhibit No. 2

[Letterhead of Reuben E. Lawson, Attorney at Law]

July 16, 1960

Dr. Herman L. Horn, Superintendent

Roanoke County Public Schools

Salem, Virginia

Dear Dr. Horn:

Enclosed you will find, properly executed, Pupil Place

ment Forms for the following students who are seeking

admission to the school nearest their homes in Roanoke

County, Virginia, to-wit: Gwendolyn Yvette Marsh, Jean

Millicent Ferguson, Gregory Morris Ferguson, Judy Carol

West, Alvin West, Jr., Lula Marie West, and Barbara Lynn

West, all of whom seek transfers to Clearbrook Elementary

School.

You will kindly direct all communications relative to these

applications to the undersigned.

Very truly yours,

Reuben E. Lawson

REL: E

Enclosures

App. 2

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

P u p il P l a c e m e n t B oard

August 30, 1960

Defendant’s Exhibit No. 1

Airs. R. M. Iseley

Route 5, Box 823

Roanoke, Virginia

Dear Mrs. Iseley:

This is to advise that the Pupil Placement Board at its meet

ing on August 29, 1960 denied your request for the enroll

ment of your daughter, Gwendolyn Yvette Marsh, in the

Clearbrook School and continued her enrollment in the

Carver School in Roanoke County, in accordance with Pupil

Placement Board regulations requiring the submission of

such requests sixty days prior to the commencement of any

school session.

This action was taken without prejudice to your right to

make new application at least sixty days prior to the opening

date of the 1961-1962 school session, if you desire to do so.

Yours truly,

(s) B. S. Hilton

Executive Secretary

BSH :gj

CC: Mr. Plerman L. Horn, Div. Supt.

Roanoke County Schools

App. 3

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

P u p il P l a c e m e n t B oard

August 30, 1960

Mrs. Jacquelyn L. Ferguson

Route 5, Box 790

Roanoke, Virginia

Plaintiff’s Exhibit No. 2

Dear Mrs. Ferguson:

This is to advise that the Pupil Placement Board at its

meeting on August 29, 1960 denied your requests for the

enrollment of your children, Gregory Morris Ferguson and

Joan Millicent Ferguson, in the Clearbrook School and

continued their enrollment in the Carver School in Roanoke

County, in accordance with Pupil Placement Board regula

tions requiring the submission of such requests sixty days

prior to the commencement of any school session.

This action was taken without prejudice to your right to

make new applications at least sixty days prior to the opening

date for the 1961-1962 school session, if you desire to do so.

Yours truly,

Is) B. S. Hilton

Executive Secretary

BSH :gj

CC: Mr. Herman L. Horn, Div. Supt.

Roanoke County Schools

App. 4

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

P u p il P l a c e m e n t B oard

August 30, 1960

Defendant’s Exhibit No. 1

Mr. Alvin J. West, Sr.

Route 5, Box 824

Roanoke, Virginia

Dear Mr. West:

This is to advise that the Pupil Placement Board at its

meeting on August 29, 1960 denied your requests for the

enrollment of your children, Barbara Lynn, Alvin, Jr., Lula

Marie and Judy Carol in the Clearbrook School and con

tinued their enrollment in the Carver School in Roanoke

County, in accordance with Pupil Placement Board regula

tions requiring the submission of such requests sixty days

prior to the commencement of any school session.

This action was taken without prejudice to your right to

make new applications at least sixty days prior to the opening

date for the 1961-1962 school session, if you desire to do so.

Yours truly,

(s) B. S. Hilton

Executive Secretary

BSH:gj

CC: Mr. Herman L. Horn, Div. Supt.

Roanoke County Schools

App. 5

ADDITIONAL EXCERPTS BY APPELLEES

FROM TRANSCRIPT

Testimony of Herman L. Horn

DIRECT E X A M IN A T IO N

[tr. PP. 33-37]

Q What was your reason for recommending—did you

have a reason for recommending that these transfers be

denied?

A Yes, sir.

M r . C h a p m a n : I object to that, sir—to the question. I

think it is irrelevant. The applications are in that show

the dates and they speak for themselves.

T h e Court : What is the relevancy of his reason ? What

bearing does it have ?

M r . N a b r it : Your Honor, to answer that, probably I

should state my position. It is our position that the Pupil

Placement Board in actual practice operates too routinely,

ratifies the action that is really taken locally; that the local

people exercise any real effective judgment in actual practice

here in Roanoke County. Now, I recognize that any reasons

that Mr. Horn may have had for making a recommendation

which he did not communicate would be of dubious value.

T h e Co u r t : That application itself is in evidence. All

I see on there is the recommendation as to school, which

pupil should be assigned. And this application is signed by

the Assistant Superintendent.

M r . N a b r it : Y es, sir.

T h e Co u r t : And it says “Carver School.” No question

that that is the recommendation. What difference does it

make why they recommended it. He is bound by the recom

App. 6

mendation, whether it is good or bad. In other words, he

may be wrong in his recommendation. But even though he

had a good reason for it, if he is wrong in his recommenda

tion, that wouldn’t change it, would it ?

M r . N a b r it : Well, Your Honor, Plaintiffs’ basic con

tention in this case is that there is racial discrimination. I

don’t know how much of this you want me to state now. I

realize it is not the appropriate time to argue the case. But

we feel that the reasons the administrative body give for

their own action are relevant.

T h e C ourt : Well, the body that has the power to assign

it might be an appropriate question under certain circum

stances as far as the Pupil Placement Board is concerned.

Am I incorrect that the Pupil Placement Board of Virginia,

under the existing law, is the one that assigns pupils in this

County and the local School Board doesn’t have anything

to do with it under the law; isn’t that correct ? I know you

don’t think the law is correct, but that is what it requires;

does it not ?

M r . N abrit : I don’t know if I could agree with the State

that the local people don’t have anything to do with it. They

have something to do. But under the law of assignment, it

is invested in the Pupil Placement Board.

T h e Court : All right. If it is invested in them, regard

less of what he might do, other than to influence them, if he

could, the power is in the Pupil Placement Board.

M r . N a b r it : We don’t dispute that, sir.

T h e Court : How much he recommends, what difference

does that make ?

M r . N a brit : Because we can establish and the testimony

already indicates that the Pupil Placement Board follows his

recommendation s.

T h e Court : Assuming that to be true—

M r . N a b r it : And to connect that up, the local assign

ment system is based upon a set of school zones, determined

upon the basis of race and those are—

T h e C o u r t : In this particular case, on these applica

tions, the Pupil Placement Board has not acted thereon;

isn’t that correct ?

M r . C h a p m a n : That is correct.

T h e C o u r t : They haven’t acted on them. That is what

the record shows.

M r . N a b r it : I don’t think that is entirely true. One

child, a beginner, the Placement assigned her to Carver

School.

T p i e Court : The others ?

M r . N a brit : The others, the Board.

T h e Co u r t : Isn’t it a fact now whether they have that

right—that is what you are asking me to determine. Well,

isn’t it a fact that the Pupil Placement Board refused to act

on these applications because they were not timely filed,

according to their indications? In other words, they were

not filed within 60 days. Isn’t that correct?

M r . N a b r it : That is correct.

T h e Co u r t : Now, if they have the right—and that is

one of the questions that we have to determine. You set a

cut-off date for assignment. That is one thing. If they do

not have the right and do not act on it, how can the Super

App. 7

App. 8

intendent be charged with discrimination when he has no

power to do anything about it ?

M r . N a brit : Well, sir, I think the problem we have here

is that when the Board fails to act, it in effect reassigns the

pupil. When the Board refuses to consider an assignment,

the child still goes to—

T he C ourt : Since I am hearing it without a jury, at the

same time I will let him answer the question. But I don’t

know how it could be relevant, because let’s assume that he

recommended that these children be sent to the school they

applied for. Let’s assume that he did that. Of course, he

didn’t but let’s assume he did. He recommended that. But

the Board that has the power and the duty of assigning

children would not entertain it because it wasn’t filed in

time. Would his recommendation in their favor have any

more bearing if it was just the opposite ? Don t we get back

to the pertinent question as to whether or not the State

Pupil Placement Board has a right or whether they used

subterfuge to deny these children of their rights ? Let him

answer the question.

M r . N a b r it : I think his recommendation would bear on

racial discrimination.

T h e Court : What reason did you have ? First let me ask

you: These recommendations are signed by E. B. Broad

water, Assistant Superintendent. That is not you?

T h e W it n e s s : No, sir.

T h e C o u r t : Did you make any written recommenda

tions ?

T h e W it n e s s : No. Mr. Broadwater signed them at my

request.

App. 9

T h e Court : As an assistant ?

T h e W it n e s s : M y responsibility. I m ade the decision.

%

[t r . p . 47]

Q Everyone that comes in goes to school in the zone;

doesn’t he?

A I would think that is pretty generally true, yes.

Q Can you take Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 2, the map, and make

an indication for the Court as to where these people, what

neighborhood these people live in ?

T h e C ourt : I believe it is conceded that these applicants

live near and within the zone, that is, the white school zone,

and he testified to that before.

M r. N a brit : I thought Your Honor might want to know

where they were on the map so the map would be more

useful.

M r. C h a p m a n : Your Honor might recall, in Richmond,

that they actually live closer to a school called Ogden than

they do to Clearbrook, We admit they live where they live.

And Clearbrook, located where it is, is closer that Carver.

T h e Court : I don’t have any objections to spotting it on

the map. Now, it is very clear to the Court that these chil

dren live closer—put it in the record last time—to Clear

brook School than they do to the Carver School and some

of them, not all, live closer to Ogden than they do to Clear

brook.

* * *

App. 10

Testimony of Ernest J. Oglesby

DIRECT E X A M IN A T IO N

[t r . PP. 112-114]

A Then it is handled by the Placement Board.

Q Your Board has provisions for still further proceed

ings when you reject, turn down assignment requests? You

have protests proceedings, don’t you ?

A If we reject any request made to us by a parent for

any reason whatsoever, we notify the parents in writing

from our Board that they have within IS days to apply for

a hearing.

Q Do you notify through—■

A I don’t know the exact administrative machinery. We

notify the parent. We see that they get notification. The

parent knows that he has 15 days to ask for a hearing. If

he asks for a hearing, he gets a hearing. And we will make

that hearing as easy as we can for him by going to the

community where the parent lives to have the hearing rather

than forcing him to come to Richmond at his expense and

all his troubles.

Q Since you have been in office, how many such protest

hearings have you had ?

A We have had two.

Q You had two ?

A Two hearings.

Q What community ?

A One in Richmond; one in Waynesboro.

Q Now—

T h e Co u r t : Have you had any requests for protest

hearings that you didn’t hear ?

App. 11

T h e W it n e s s : No, sir. We have had none that we did

not grant. I assure you, sir, that we will always grant any

requests of that kind and make it as easy as possible for a

parent to have a perfectly fair hearing on it.

B y M r . N a br it :

Q Now, Mr. Oglesby, when you notify a parent that

his request for transfer is denied and he has the right to

apply for this hearing, does your Board always notify him

why this request was rejected ?

A I can’t answer that. I am not familiar enough with

the letter that goes to the parent.

Q Do you have any formal rules on this ?

A No.

Q Regulations ?

A Not that I know of.

Q Do you have any rules with respect to the hearings ?

M r . S c o t t : I f M r. N a b rit will fam iliarize him self w ith

the law, I don’t th ink it is in the law itself.

T h e Court : All this witness is saying: he didn’t know.

He wasn’t familiar with the exact form of the letter. The

objection is overruled.

Go ahead.

B y M r . N a brit :

Q I asked you if your Board had adopted any rules and

regulations for the conduct of protest pursuant to the

statute ?

A Well, we adopted this rule. So I am not sure whether

that rule was one adopted by the previous Board. But we

have a rule that they have 15 days to protest. If they ask

for the protest, we then proceed to go there and have a

App. 12

hearing and give them every chance to present the facts.

Now, I don’t know what you mean by procedure otherwise.

We try to have a fair hearing and give them every opportu

nity to bring out all of the facts.

Q You don’t have any written set of rules governing

your conduct at hearings, right?

A No, we don’t have any regular set rules governing our

conduct. We try to act in a fair way, trying to bring out

the truth and see what the truth is and to see whether the

protest granted and our ruling changed.

Q Now, Mr. Chairman, are you aware of any announce

ments by your Board relating to announcement or communi

cation to local school authorities relating to school zones,

separate zones for Negro and white children?

A No, we haven’t had any announcement of that kind.

We had been asked to approve, in the case of Waynesboro,

certain * * *

* * *

[ t r . p p . 123-124]

T h e C o u r t : In other words, if they moved on July the

second, they would be entitled to go to school the next year

and the Pupil Placement Board would assign those students ?

T h e W it n e s s : Yes. It is my intention—

M r . S cott : The regulation so specify.

T h e Court : I want to get it in the record. We have been

talking about this question for two hours.

M r . N a br it : I have no fu r th e r questions.

M r . C h a p m a n : I have no questions.

T h e Court : Do you have any questions ?

Mr. S cott : Yes.

App. 13

C R O SS-E X A M IN A TIO N

B y M r . S c o t t :

Q Doctor, you said that since you have been on the

Board, there have been two appeals to your Board ?

A Two cases of hearings.

Q Of hearings.

A We turned down no appeals.

Q What were the results of those hearings ?

A We granted one. We declined one. The one that was

declined, as you know—you want me to explain ?

Q That is all I want to know. Now, you refer to a

recommendation of the local school board or local school

authorities. To what extent do you pay attention?

A I would say, Mr. Scott, that in only one of the cases

where we put Negro children into a predominantly white

school last year did we have—by the wildest imagination—

could be described as being the recommendation of the local

school board: that in every other case, this Board acted on

its own and certainly contrary to any formal recommenda

tions of any kind made by any local school board. Now, we

talk it over and we try to find out everything we could about

the situation, about the quality of the children and the kind

of work they do and the rest of that, but those integrations

that we did in the school last year were done by the Pupil

Placement Board and certainly not on the recommendation

of the local school board.

Q Do you consider that you are controlled by recom

mendations of the local school board?

A I don’t think we are controlled by anybody on earth.

* * *

App. 14

REDIRECT E X A M IN A T IO N

[ t r . p . 133]

M r . N a br it : I didn’t understand the witness to say that

it makes any difference. We were talking about a limited

category of pupils.

T h e Co u r t : I understood him to say that if the local

board had a school board that interfered with their meas

urement of distance, if it reverted to that, they decided the

matter on distance; is that correct ?

T h e W it n e s s : That is correct, sir.

M r . N a b r it : Y ou w ouldn’t accept a school b o a rd ’s rec

om m endations on the basis o f zones? Y ou would ignore it?

T h e C o u r t : No, no. He said where there was a dispute

between the school board’s recommendation and the appli

cant. Now, it didn’t make any difference what the school

board recommended. He then hears the case. In case of

agreement, the State Board leaves them where the parent

and the School Board mutually agree they want to go.

Mr. N abrit : Mutually agree, sir?

T he Court : I thought a mutual agreement—if they are

in accord, why wouldn’t it be a mutual agreement? If there

is no dispute, it is bound to be a mutual agreement. But

everybody has a right to disagree with * * *

* * *

Printed Letterpress by

L E W I S P R I N T I N G C O M P A N Y • R I C H M O N D , V I R G I N I A