Board of Education of the City of Bessemer v. Brown Supplemental Brief of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Education of the City of Bessemer v. Brown Supplemental Brief of Petitioners, 1967. 5ee69dcc-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/11a50d58-0e77-4d4e-bdf2-f78c273974ef/board-of-education-of-the-city-of-bessemer-v-brown-supplemental-brief-of-petitioners. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

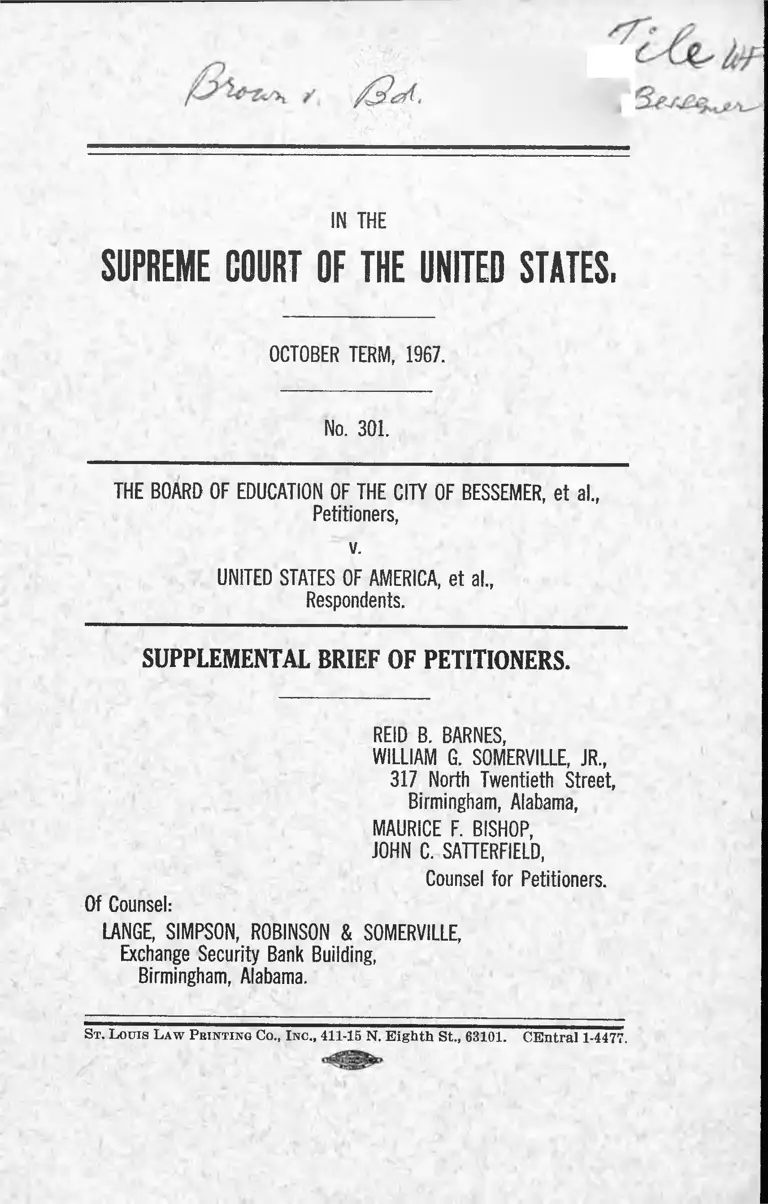

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1967.

No. 301.

TH E BOARD O F EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.,

Respondents.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF PETITIONERS.

REID B. BARNES,

WILLIAM G. SOMERVILLE, JR.,

3 17 North Twentieth Street,

Birmingham, Alabama,

MAURICE F. BISHOP,

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Of Counsel:

LANGE, SIMPSON, ROBINSON & SOMERVILLE,

Exchange Security Bank Building,

Birmingham, Alabama.

St . L ouis L aw P rinting Co., I nc., 411-15 N. Eighth St., 63101. CEntral 1-4477,

INDEX.

Page

Explanatory statement ................................................ 1

Appendix 1—Opinion in case of Monroe v. Board of

Commissioners, City of Jackson, Tenn..................... 7

Cases Cited.

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955).. 2

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), petition for certiorari filed, 0. T.

1967, No. 131 ............................................................. 2

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373

U. S. 683 .................................................................... 2

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, City of Jackson,

Tenn., Nos. 17118 and 17119 (6th Cir., decided July

21, 1967) .................................................................... 1,2

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF H E UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TERM, 1967.

No. 301.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et al„

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et a l.

Respondents.

SUPPLEMENTAL BRIEF OF PETITIONERS.

The purpose of this supplemental brief is to invite to

the Court’s attention a recent decision of the 'Sixth Circuit

Court of Appeals which was decided after the filing of our

petition for certiorari. In that case, Monroe v. Board of

Commissioners, City of Jackson, Tenn., Nos. 17118 and

17119 (6th Cir., decided July 21, 1967), the Sixth Circuit

criticizes and refuses to follow the decision below of the

Fifth Circuit with regard to its newly adopted constitu

tional standards governing student assignments—which is

the principal issue as to which review is sought by our

2

petition. The Monroe opinion is printed as Appendix 1,

infra. This decision now brings the Sixth Circuit, as well

as the Fourth and Eighth Circuits, clearly into conflict

with the decision below.

In Monroe the Sixth Circuit specifically rejects the view

of the Fifth Circuit in Jefferson County that the Four

teenth Amendment and this Court’s decisions in Brown v.

Board of Education and its progeny affirmatively require

compulsory integration, that the constitutional sufficiency

of a desegregation plan depends upon its mathematical

results, and that different constitutional duties and prin

ciples apply to Southern schools previously having so-

called “de jure segregation” than to Northern schools hav

ing so-called “de facto segregation.” In doing so, the Sixth

Circuit reaffirmed the principles previously formulated by

it in Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), petition for certiorari filed, 0. T. 1967, No.

131, and applied them to two school systems in Tennessee

which, until the commencement of desegregation suits in

1963, had operated “de jure-segregated” schools. Ironic

ally, the Tennessee school systems involved are located

little more than fifty miles from schools in Alabama and

Mississippi which are governed by the contrary decision

of the Fifth Circuit.

The conflict between Monroe and the decision below is

indicated in the following excerpts from the Sixth Cir

cuit’s opinion. After noting and approving the district

court’s conclusion that “the Fourteenth Amendment

[does] not command compulsory integration of all of the

schools”,1 the Sixth Circuit holds that its interpretation of

Brown in Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Education, supra, as

1 The district court’s conclusion was based on this Court’s

opinion in Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683, on Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp 776 (E. D. S. C.

1955), and on previous decisions of the Fifth Circuit which the

decision below now overrules. See 244 F. Supp. at 356-58.

3

“prohibiting only enforced segregation” is applicable

equally to a school system which had “de jure-segregated”

schools:

We are at once aware that we were there [in Deal]

dealing with the Cincinnati schools which had been

desegregated long before Brown, whereas we consider

here Tennessee schools desegregated only after and in

obedience to Brown. We are not persuaded, however,

that we should devise a mathematical rule that will

impose a different and more stringent duty upon states

which, prior to Brown, maintained a de jure biracial

school system, than upon those in which the racial

imbalance in its schools has come about from so-called

de facto segregation—this to be true even though the

current problem be the same in each state.

It then considers and rejects the contrary view of the

Fifth Circuit in the decision below:

We are asked to follow United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 F. (2) 836 (C. A. 5,

1966), which seems to hold that the pre-Brown biracial

states must obey a different rule than those which

desegregated earlier or never did segregate. This

decision decrees a dramatic writ calling for mandatory

and immediate integration. In so doing, it distin

guished Bell v. School City of Gary, Indiana, 324 F.

(2) 209 (C. A. 7, 1963), cert. den. 377 U. S. 924, on

the ground that no pre-Brown de jure segregation had

existed in the City of Gary, Indiana, 372 F. (2) at 873.

It would probably find like distinction in our Tina

Deal decision because of Cincinnati’s long ago de

segregation of its schools. We, however, have ap

plied the rule of Tina Deal to the schools of Tennes

see. * * * However ugly and evil the biracial school

systems appear in contemporary thinking, they were,

as Jefferson, supra, concedes, de jure and were once

— 4 —

found lawful in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. 8. 537

(1896), and such was the law for 58 years thereafter.

To apply a disparate rule because these early systems

are now forbidden by Brown would be in the nature

of imposing a judicial Bill of Attainder. Such pro

scriptions are forbidden to the legislatures of the

states and the nation—U. S. Const., Art. I, Section 9,

Clause 3 and Section 10, Clause 1. Neither, in our

view, would such decrees comport with our current

views of equal treatment before the law.

The opinion concludes that:

[T]o the extent that United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, and the decisions re

viewed therein, are factually analogous and express a

rule of law contrary to our view herein and in Deal,

we respectfully decline to follow them.

The Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Circuits, together with

the Fifth, embrace most of the Southern and Border states,

which of course are those principally concerned with the

desegregation of school systems operating segregated

schools countenanced by state law when Brown was de

cided in 1954. As the Fifth Circuit’s majority opinions

below acknowledge, there certainly is no basis for ap

plication of different constitutional standards and theories

of constitutional interpretation to previously “ de jure-

segregated” schools in the Fifth Circuit than to such

schools in the Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Circuits. Whether

the decision below of the Fifth Circuit or the decisions of

the Fourth, Sixth, and Eighth Circuits are ultimately

determined to be the correct interpretation of the con

stitutional requirements of Brown v. Board of Education,

the anomaly of such disparate results should not be per

mitted to stand. Petitioners therefore respectfully re

iterate their suggestion to the Court that the questions

raised by their petition and the decision below are of such

— 5 —

far-reaching importance to the implementation of this

Court’s school desegregation decisions and to uniformity

in the framing of constitutional standards by the circuits

that their resolution by this Court through a grant of

the writ of certiorari is fully warranted.

Respectfully submitted,

REID B. BARNES,

WILLIAM G. SOMERVILLE, JR.,

317 North Twentieth Street,

Birmingham, Alabama,

MAURICE F. BISHOP,

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Of Counsel:

LANGE, SIMPSON, ROBINSON &

SOMERVILLE,

Exchange Security Bank Building,

317 North Twentieth Street,

Birmingham, Alabama.

A P P E N D I X .

APPENDIX.

Exhibit 1.

Nos. 17,118 and 17,119.

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

Brenda K. Monroe et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

v.

Board of Commissioners, City of

Jackson, Tennessee, et al., and

County Board of Education,

M a d i s o n County, Tennessee,

et al., Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the U. S.

District Court for

“■ the Western Dis

trict of Tennessee.

Decided July 21, 1967.

Before: O’Sullivan, Phillips and Peck, Circuit Judges.

O’Sullivan, Circuit Judge. In 1963 a suit was filed by

Brenda K. Monroe and others, Negro children and their

parents, to bring about the desegregation of the public

schools of the City of Jackson and of Madison County,

Tennessee.1

The District Court required the school authorities to

submit plans to accomplish desegregation and ultimately

granted the relief sought by approving parts of a submit

ted plan and ordering other steps to be taken. Separate

opinions were written, one involving the City of Jackson

schools, reported as Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of

the City of Jackson, Tennessee, et al., 221 F. Supp. 968

1 The City of Jackson is located in Madison County and the

respective school authorities are the Board of Commissioners

of the City of Jackson and the County Board of Education of

Madison County.

— 8 —

(W. D. Tenn. E. D. 1963), and the other relating to Mad

ison County Schools, reported in Monroe v. Board of Com

missioners, etc., et al, 229 F. Supp. 580 (W. D. Tenn.

E. D. 1964). Appeals to this Court from these cases were

dismissed by agreement. Obedient to the above decisions,

all grades of the schools involved have been desegregated.

The litigation with which we now deal arises from Mo

tions for Further Relief filed in the District Court by

plaintiffs. By these motions, plaintiffs, sought to accom

plish greater integration of the school children, desegrega

tion of the teaching staffs, and the enjoining of described

practices of the school authorities which were alleged to

be violative of the District Judge’s original decrees and

contrary to new developments in the law. The District

Judge, again, dealt separately with the city and the county

schools in disposing of the Motions for Further Relief.

His decision as to the city schools is reported in Monroe

v. Board of Commissioners, City of Jackson, 244 F. Supp.

353 (W. D. Tenn. E. D. July 30, 1965), and as to the

county schools in Monroe v. Board of Education, Madison

County, Tennessee, et al. . . . F. Supp. . . . (W. D. Tenn.

E. D. August 2, 1965). These are the cases before us on

this appeal; the plaintiffs are the appellants. These opin

ions, with the earlier ones reported at 221 F. Supp. 968 and

229 F. Supp. 580, swpra, set out the facts and we will re

state them only where needed to discuss the present con

tentions of the plaintiffs-appellants.

1) Compulsory Integration.

Appellants argue that the courts must now, by recon

sidering the implications of the Brown v. Board of Edu

cation decisions in 347 U. S. 483 (1954), and 349 U. S. 294

(1955), and upon their own evaluation of the commands

of the Fourteenth Amendment, require school authorities

to take affirmative steps to eradicate that racial imbalance

— 9 —

in their schools which is the product of the residential

pattern of the Negro and white neighborhoods. The Dis

trict Judge’s opinion discusses pertinent authorities and

concludes that the Fourteenth Amendment did not com

mand compulsory integration of all of the schools regard

less of an honestly composed unitary neighborhood system

and a freedom of choice plan. We agree with his con

clusion. We have so recently expressed our like view in

Tina Deal et al. v. The Cincinnati Board of Education,

389 F. (2) 55 (CA 6, 1966), petition for cert, filed, 35 LW

3394 (U. S. May 5, 1967) (No. 1358), that we will not here

repeat Chief Judge Weick’s careful exposition of the rele

vant law of this and other circuits. He concluded, “ We

read Brown as prohibiting only enforced segregation” .

369 F. (2) at 60. We are at once aware that we were there

dealing with the Cincinnati schools which had been de

segregated long before Brown, whereas we consider here

Tennessee schools desegregated only after and in obedi

ence to Brown. We are not persuaded, however, that we

should devise a mathematical rule that will impose a dif

ferent and more stringent duty upon states which, prior

to Brown, maintained a de jure biracial school system,

than upon those in which the racial imbalance in its

schools has come about from so-called de facto segrega

tion—this to be true even though the current problem be

the same in each state.

We are asked to follow United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, 372 F. (2) 836 (CA 5, 1966), which

seems to hold that the pre-Brown biracial states must

obey a different rule than those which desegregated ear

lier or never did segregate. This decision decrees a dra

matic writ calling for mandatory and immediate integra

tion. In so doing, it distinguished Bell v. School City of

Gary, Indiana, 324 F. (2) 209 (CA 7, 1963), cert, den. 377

U. S. 924, on the ground that no pre-Brown de jure seg

regation had existed in the City of Gary, Indiana. 372 F.

— 10 —

(2) at 873. It would probably find like distinction in our

Tina Deal decision because of Cincinnati’s long ago de

segregation of its schools. We, however, have applied the

rule of Tma Deal to the schools of Tennessee. In Mapp

v. Board of Education, 373 F. (2) 75, 78 (CA 6, 1967),

Judge Weick said,

“ To the extent that plaintiffs’ contention is based

on the assumption that the School Board is under a

constitutional duty to balance the races in the school

system in conformity with some mathematical for

mula, it is in conflict with our recent decision in Deal

v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F. (2) 55 (6th

Circ. 1966).”

However ugly and evil the biracial school systems appear

in contemporary thinking, they were, as Jefferson, supra,

concedes, de jure and were once found lawful in Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896), and such was the law for

58 years thereafter. To apply a disparate rule because

these early systems are now forbidden by Brown would

be in the nature of imposing a judicial Bill of Attainder.

Such proscriptions are forbidden to the legislatures of the

states and the nation—U. S. Const., Art. I, Section 9,

Clause 3, and Section 10, Clause 1. Neither, in our view,

would such decrees comport with our current views of

equal treatment before the law.

This is not to say that Tennessee school authorities can

dishonestly construct or deliberately contrive a system for

the purpose of perpetuating a “ maximum amount” of its

pre-Brown segregation. Northeross v. Board of Educa

tion of City of Memphis, 33 F. (2) 661, 664 (CA 6, 1964).

But to the extent that United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, and the decisions reviewed therein,

are factually analogous and express a rule of law contrary

to our view herein and in Deal, we respectfully decline to

follow them.

— 11 —

2) Gerrymandering.

Appellants assert that while giving surface obedience

to the establishment of a unitary zoning system and free

dom of choice, the school officials of the City of Jackson

had been guilty of “ gerrymandering” in order “ to pre

serve a maximum amount of segregation.” Were this true,

it would be violative of the law. Northcross v. Board of

Education of City of Memphis, 302 F. (2) 818, 823 (CA

6, 1962), cert. den. 370 U. S. 944, and Northcross v. Board

of Education of City of Memphis, 333 F. (2) 661, 664 (CA

6, 1964). The District Judge in the instant matter did

hold that as to some boundary lines “ there appears to be

gerrymandering.” Monroe v. Board of Commissioners,

City of Jackson, supra, 244 F. Supp. at 361. As to these in

stances, he ordered changes in the school zone lines. Id.

at 361, 362. But, as to the junior high schools, he con

cluded,

“ that the proposed junior high school zones proposed

by defendants do not amount to gerrymandering.”

244 F. Supp. at 362.

Without making our own recitation of the relevant evi

dence, we express our agreement with the District Judge.

3) Faculty Desegregation.

In the accomplishment of desegregation in the involved

schools, there remain some that are attended only by

Negro and other only by white children. The teaching

staff conforms substantially to this pattern—all Negro

teachers in the all Negro schools and all white teachers

in the all white schools. Little attention was paid to the

teaching staff in the early desegregation cases. Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, did not speak on it, nor did

the early relevant decisions from this circuit. In Mapp v.

Board of Education of Chattanooga, 319 F. (2) 571, 576

(CA 6, 1963), however, we ordered restored to the com-

— 12 —

plaint there involved allegations and prayers for relief

relating to assignment of teachers and principals, hut

ordered also that “ decision of the legal question presented

await development of the progress of the plan approved.”

319 F. (2) at 576. And we further concluded that “ within

his discretion, the District Judge may determine when, if

at all, it becomes necessary to give consideration to the

question. . . . ” Ibid.

This leisurely postponement of consideration of faculty

desegregation appealed to the Fourth Circuit, when in

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia,

345 F. (2) 310, 320, 321 (CA 4, 1965), it said:

‘ ‘ The possible relation of a reassignment of teachers

to protection of the constitutional rights of pupils

need not be determined when it is speculative. When

all direct discrimination in the assignment of pupils

has been eliminated, assignment of teachers may be

expected to follow the racial patterns established in

the schools. An earlier judicial requirement of gen

eral reassignment of all teaching and administrative

personnel need not be considered until the possible

detrimental effects of such an order upon the adminis

tration of the schools and the efficiency of their staffs

can be appraised along with the need for such an

order in aid of protection of the constitutional rights

of pupils.”

But the Supreme Court declared this would not do, and

in Bradley v. School Board, 382 U. S. 103 (1965), re

manded the case to require the Richmond School Board

to proceed with study and resolution of the faculty in

tegration question, stating:

“ There is no merit to the suggestion that the

relation between faculty allocation on an alleged

racial basis and the adequacy of the desegregation

plans is entirely speculative.” 382 U. S. at 105.

13 —

The Bradley opinion was followed by Rogers v. Paul,

et al., 382 U. S. 198 (1965); once again the Supreme Court

remanded the cause for consideration of the faculty de

segregation problem.

The District Judge in the matter now before us did

hear some evidence on the question of faculty desegrega

tion and concluded:

“ We do not believe that the proof of the plaintiffs

is sufficiently strong to entitle them to an order re

quiring integration of the faculties and principals.”

244 F. Supp. at 364.

He did, however, attack a then current policy of the

school authorities whereby white teachers and Negro

teachers, “ simply because of their race,” were respec

tively assigned only to schools whose pupils were all or

predominantly of that teacher’s race. The order imple

menting his decision contained the following:

The application of plaintiffs for an order requir

ing integration of faculty is at this time denied. How

ever, the policy of defendants of assigning white

teachers only to schools in which the pupils are all or

predominantly white and Negro teachers only to

schools in which the pupils are all Negro is by this

order rescinded to the extent that white teachers, who

so desire, will not be barred from teaching in schools

in which the pupils are all or predominantly Negro,

and Negro teachers, who so desire, will not be barred

from teaching in schools in which the pupils are all

or predominantly white.

To implement this change in policy, defendants

must forthwith, as to substitute teachers, and each

year beginning with the year 1966-67, as to all

teachers, publicize it and obtain from each teacher

an indication of willingness or an indication of objec

tion to teaching in a school in which the pupils are

all or predominantly of the other race. All teachers

•—14 —

who indicate such a willingness will be assigned to

schools without consideration of the teacher or the

pupils, but all other usual factors may be considered

in assigning teachers. Nothing in this order, however,

will be construed as requiring the assignment of an

objecting teacher to a school in which the pupils are

all or predominantly of the other race or will be con

strued as requiring a refusal to employ or a dismissal

of a teacher who objects to teaching in such a school.

This change in policy will be effective as to substitute

teachers during the remainder of the school year

1965-66 and as to all teachers beginning with the

school year 1966-67.”

We note that this order was handed down before

Bradley v. School Bd., supra, and we are constrained to

hold that it does not commit or require the school author

ities to adopt an adequate program of faculty desegre

gation which will pass muster under the implied com

mand of the Bradley case. Whatever Bradley’s clear

language, we cannot read it otherwise than as forbidding

laissez faire handling of faculty desegregation. It implies

that the accomplishment of that goal cannot be left to the

free choice of the teachers and that the Board must

exercise its authority in making faculty assignments so as

to assist in bringing to fruition the predicted benefits of

school desegregation.

No Supreme Court decision, however, has as yet pro

vided a blue print that will achieve faculty desegregation.

The United States Office of Education has indicated that,

in some affirmative way, school boards must act to correct

past discriminatory practices in the assignment of

teachers.2 But its recommendations do not have the force

2 Ҥ 181.13 Faculty and Staff

(a) Desegregation of Staff. The racial composition of the

professional staff of a school system, and of the schools in the

system, must he considered in determining whether students are

15 —

of law; neither does it provide clear guidelines to make

easy the job of school boards in dealing with this problem.

It will be difficult to eliminate the forcing of people into

places and positions because of race and at the same time

compulsorily assign a school teacher on the basis of his or

her race.

It is sufficient for us to say now that the formula an

nounced by the District Judge, leaving the decision of

integration of the faculties to the voluntary choice of the

subjected to discrimination in educational programs. Each

school system is responsible for correcting the effects of all

past discriminatory practices in the assignment of teachers and

other professional staff.

(b) New assignments. Race, color, or national origin may not

be a factor in the hiring or assignment to schools or within

schools of teachers and other professional staff, including stu

dent teachers and staff serving two or more schools, except to

correct the effects of past discriminatory assignments.

(d) Past assignments. The pattern of assignment of teach

ers and other professional staff among the various schools of

a system may not be such that schools are identifiable as in

tended for students of a particular race, color, or national

origin, or such that teachers or other professional staff of a

particular race are concentrated in those schools where all,

jor the majority, of the students are of that race. Each school

system has a positive duty to make staff assignments and re

assignments necessary to eliminate past discriminatory assign

ment patterns. Staff desegregation for the 1966-67 school year

must include significant progress beyond what was accom

plished for the 1965-66 school year in the desegregation of

teachers assigned to schools on a regular full-time basis. Pat

terns of staff assignment to initiate staff desegregation might

include, for example: (1) Some desegregation of professional

staff in each school in the system, (2) the assignment of a

significant portion of the professional staff of each race to par

ticular schools in the system where their race is a minority

and where special staff training programs are established to

help with the process of staff desegregation, (3) the assign

ment of a significant portion of the staff on a desegregated

basis to those schools in which the student body is desegre

gated, (4) the reassignment of the staff, of schools being closed

to other schools in the system where their race is a minority,

or (5) an alternative pattern of assignment which will make

comparable progress in bringing about staff desegregation suc

cessfully.

— 16 —

teachers, does not obey current judicial commands. We,

therefore, remand this phase of the litigation to the Dis

trict Judge to reconsider upon a further evidentiary hear

ing the matter of faculty desegregation.

4) Desegregation of Teachers Organizations.

It appears that at the time of the hearing in the District

Court there existed in Tennessee two voluntary organiza

tions, the Tennessee Education Association, whose mem

bership was confined to white teachers, and the Tennessee

Education Congress, made up of Negro teachers. Tradi

tionally, the School Board allowed separate holidays to

permit the members of these organizations to attend so-

called ‘ ‘ teacher in-training ’ ’ programs. The District Judge

dealt with this subject as follows:

“ Plaintiffs also seek an order prohibiting segrega

tion of teacher in-service training. Although the proof

is not completely clear, it appears that the only such

segregation that remains results from the fact that the

white teachers and the Negro teachers are members

of separate professional organizations. It appears

without dispute that defendants do not control the

policies of these organizations. In any event, as here

tofore indicated, the Mapp case, supra, holds that

plaintiffs have no standing to assert any constitutional

claims that the teachers may have and may assert a

claim for teacher desegregation only in support of

their constitutional right, as pupils, to an abolition of

discrimination based on race. The assertion by plain

tiffs that what remains of segregation in teacher in-

service training has an effect on their right as pupils

is, on the proof in this case extremely tenuous. We

deny this application for relief.” 244 F. Supp. at 365.

The evidence on this subject is too meager to permit us

to evaluate the extent to which the school authorities par

ticipated in or aided the activities of these separate

— 1 7 —

teacher organizations, and the degree to which member

ship by the teachers in them would, in turn, affect the

rights of the pupils. It appears, however, that these in-

service training programs for teachers are conducted pur

suant to state law, and are financed with public funds.3

We make clear that the plaintiff pupils do have standing

to assert that the existence of separate teacher organiza

tions based on race and the school authorities’ coopera

tion with their separated activities such as the in-training

program “ impairs the students’ rights to an education

free from any consideration of race.” Mapp v. Board,

supra, 319 F. (2) at 576. If the District Judge’s above

quoted language can be read as a contrary holding, it is

error. We also remand this issue to the District Judge for

further consideration.

5) The Jackson Symphony Orchestra.

It appeared that the Jackson Symphony Association,

with permission of the school authorities, arranged for a

program by the Jackson Symphony Orchestra at one of

the Jackson schools. The ladies in charge of this event in

vited the children in several grades of the Jackson City

Schools, the County schools, and the Catholic schools.

Those students included some from the all-white schools,

and some from the schools, public and parochial, contain

ing both Negro and white students. Students in all-Negro

schools were not invited for the two performances in

volved. Testimony by one of the ladies of the Symphony

Association denied any discriminatory motivation in the

selection of the pupils, suggesting that the capacity of the

auditorium was exhausted by those invited and in at

tendance. She said,

“ If we had room, we would have had every child in

town there—fourth, fifth and sixth grades of every

school, but we didn’t have room.”

8 See e. g., Chap. 76, Term. Public Acts, 1965, Sec. 24.

18 —

The school authorities had nothing to do with the mat

ter of who was to he chosen to attend the concert. Its

only participation was to allow the use of the auditorium.

While it would be impermissible for school authorities to

allow use of school facilities for entertainment that was

discriminatory, nothing was developed by the evidence to

cause us to criticize the District Judge’s conclusion that

the “ defendants were not motivated by racial considera

tions” in their handling of this matter. Monroe v. Board

of Commissioners, supra, 244 F. Supp. at 365.

Another issue discussed by the District Judge, . . . F.

Supp. at . . . , the so-called “ split season,” has been ren

dered moot by the elimination of the practice.

The cause is remanded to the District Judge for further

consideration of the matter of faculty desegregation and

teacher in-service training, and is otherwise affirmed.

y ,. ' y

■ i . & . Y .

: y y

'■y — ^ / a a ' y ■ :

• • ’ • J*' '' l -' - : 'o - . ' t-4." '

■ : A " : ■■•:;>'■ 7 !

• • \ . •.’ •• • , * ■ ' '

' ■. Y i >K.- ••■ »*• y ,* '.

A 1 IAY Y .' •7. . . '

: Y i>;_ *-

■> ;v>rur*:- v‘‘: '"Y i : > -

tv?!*

/•• A -

••'YY :-‘V-

!?*w~ i -r\i■\ ■•■ - • \'p ;■ ■ 7/5®$:»- •, • •••'A , U •

' \ * ....... .

Y. »■ i t ? ; *. s-4'Yv* ■• ’ : '/< ■* ' , i-‘ . % . ,, .- v . v -4 , ■•' '•» •', \--;v ;',;>y ' vc: Y ,. <v y - y \v ■ ■ ■■ ■ • "• V- - *. ; v-

tY t-^X Y Y Y Y y

X Y ■■■•. V ' Y " Y - . .ys>; -k 1

Y

. >-YC">v.

,-Y

b Y : l ? v > Y ; Y

' ,S

. Y ■YY’iXY■ ■ Y\. ■:■■■■

■ *' - -V

Y": v;-. v,. H'1 V/v

Y ; -■ * Y ' l ,

; \ i> 4 : v / t " Y ^

' - r y~ , , '

'aYaSfe ■ ■ - :

, : V y '' M ‘ : v .

V « v f ^ is - ' ' T,.

*V / Y - Y V -

7

r ~ŷ S'

■ 'tY .-a '

I \ Y ,

Y - V ',i: ^ rv

Js ?

*\ \ ■ A ,•> - '<<■ A &. —xt- • *’ -f-S. ■*

.......... K Y Y k Y ' ,

;*?<■: A ' :• Y', -Y ' Y :'YY'.Yy Y Y ^ Y Y 'r

y y ' ;a a x ' Y ' r ; ' s v > C - 7 V

S '/ Y K Y'7 'v 7 t ; '. y ~ K

f'.' ;.C C -• .. ; r v

-*i YY.Y: - - ■.. »h r-v Y Y v '7 ;

;-Y- ^ ' r

■■ . . . .

Yr ' £ 7 7 L Y Y , . ;

• '7 ' ' Y ’ Y /y .̂ \Y &

Y Y Y ; ; ' 7 > - y y r \ ■ x : ’ >J.; ^ -7Y: > 1 ■

X r 4 .x\£:Y

'Yy :c£)

Y X Y Y / Y > y 'y ;y| ; A a

‘ Y , .

• M

... ■•■! 'TA-.

If - ■■.

'■ . ' '..'7'r A

Y i / Y Y ^YY-Y^Vs ' ' ; ;

^ Y y ’1 c

■ > l Y - V m

. ' '..>V ?

■ ■ • ■i?~, v, :Y> i

YY. y ''-Y:?:y ^ : y A y ’ t e ' a l ^

~ P s \.t

A , «

,.;iv s i l

' • ■■■ ' , ■ ■- ' B v i -

• . V - , ■ ■ • - • •• f i \ ' .'■. -r.- v

. . . . - . . :

T: •,

c

I ^

. Y'"::

r 1 f , -Y •' - ' .’' A ' ' A " >

■7 . -

Y y Y Y x

' 'Y f *»f~v •\ . yy. /

V - v * •r '-' ’ «s , r v-'-

. . * ■ ; v ,

i Y Y Y Y

- .\v , ■?;>■ 7 - ' %>:

Y'A\:' y .b-v*

4?i ,■ v ^ ; :V 1 yY(', Y ’

. 4 ^ •• ^ - 1 ̂ - ^ v' N* "-r'A ' i

;Y-y ;.v ^ 'n!'

. ¥ r'.

•> . ---. x . \ |

• }

"Y

'■A:'

. ,

■ ( ■ f p K Y Y v : # . ' . \ r

- § | y y .' • Y ' - A y

- Y X ! V > Y ^ •

Y . ' A

' r-Y r f y ; i y

h Y Y

. . # s >: ■■■

VcAS •"> -?Ef.

* • • • ,/.• -.A • . . . • v •» f O ’ - ̂ • ,V ■ : , ' • •• t >.••

' '-■ i . r. s- . „ .- . ■_>-;> •• -V- ’ 'X •"

— ■ . W * ■" ; . / / >' .- < ' .

. 't'Y Y -:' : \ .'.!■■

/ ... ‘ .*•' t. . ' V. .< •;

. - V . V

’ rY;-'>v C-v:'Y' YY:

' M ■ Y 4 ‘- Y Y l

.. ., .J ..... ... ■ .. -,: ' ■ >*' 7--.

Y ' r •'■.■.■■-■ b : , ^ Y - ' ^ Y Y

> f

.; V ■• ., ;. Yi 'y?.' ;-x;. ■.» / >■'7 \ ̂V> A , " ?,.VA;X

; - ...• A - - .'Y-, ■ ■ ■:.; ^ :■ ■■' YYYY Y K 'sY Y Y i <>:Y Y Y ' Y Y -:Y y ■;

■. ■; ■ ■ v . i- , ' • .. ■ ' v. \ ' .v . . 7>.... 1 ■ ■ Y ' ■ ■ ■i.iKtY'

. , .'., •' J t-C .' / r ;

• - V . .. v. x'- - ? v :

’ y • ^ - ' ' : <

■ • V- •'' - H - r ‘>' -Y>.

•i. •••;■> v x> > ; - -y *' -v -̂ . <*?/)■. .• >• y y < y y /\ ? Y --y i j y y

y 'Y y y y y u ? . m .

, .■ . , . , . £ < ■ ' ; . r ] - . ■- •■•

. A "* V - ' Y -Y v. • • 7 , - 'v 'A 'H 'rK l ■*,' ;Y Y ' Y Y .'. 7. 7 j . 3.J .-.V/i-V * v*.*: ‘ r»:.

-V " YY

ks*Y' \ '•; ' . i y v

. ' --1 Y ■> . >. : ■\.Y ' /■ ■■. Y, . -.*• - • ‘ •'' }:

7 / - " 'x :Y “V f A v '- Y ^ ; ‘^7 ’ ' Y 'V

Y ' Y -■ Y . ' - - Y . . Y ; - ' , . . ; Y - : a 1

x » . / . v - . ' r * . . .

' 11 >•*

i ‘ Y A V r ,’i .

• 7 ’ ••*• V'*""-- -.C: '' ■ A Y Y'*' YJ. *'■ "■Y -Y • •...' tv ., •'

Y- • v"-'. - . 7\Y-/. - . ,- vA >.'• „

' - -

f ' 4 '

' ;.v 7 L :V:'7.-.. a A

y 7 Y

" t 'WS' w9

Y ' ^ Y y ' xY I Y YY7 >.Y [Yy Y Y Y

*■*” v 1 / -r , ''•'A */ U

, ■ - . Y ' . Y"' Y Y . :.

m t '■ Y Y n ' Y Y ;Y.Y , .

' V ■•.. ' Y ' ' - ■ .

̂ ’ r

.'r• ■ , ’■ ■'■'.-'■Y v\; Y Y r l Y . b % Y <- , * Y v; ;;•; ■- Y7..Y' ‘ .-, Y-)•Y ' ' Y - ' aa . 7 . v i ' ? * Y Y Y ~ Y ! t s Y . c / x Y Y Y Y

% ' ■. Y ' A . ■ v :- V -J- Y. • ' " .-• • • '•< V- Y vY \ -Y- . . X.. v, . -sbY-r 7Y A A lY>v"'-' Y -V »->!■•: '

_

. :. ' . ■- ' . - - " ‘ ' . ; . .

- :

'■ - ■ : .Y : : .Y ; ■ - y Y "rY ‘ aYYx-Y- x:AY

H i p !s M 1 ;vY" >yy '- -;y

.. ' X '-:.n

Y : Y ,Y Y Y Y■/' a- ■ .•>'•. ■' 7, - Y Y-YYa-^I'A3- ™ V ■

■■■■'■ : a '■ y'< - • -v;. a yvV ■■

■ ' ■ Y Y Y • - .. 7 - . ■ . =

•Vx.yYY .Y. y, Y

■Y.' - ^ wVC''YYf.t:! o >/ • ;; • v-~ •..:.,• /«Y' 'Ytt-1'' ’ ' ...AYwYr' ' H. s-

" • ■ • L '' ' r~ . ;• m '• v Mx . -Iy \ •:. . - a ̂*\k 5T. A '

’

‘ - . c Y '...:• . >>> - i ■ •■. Y H . X 1 ■ k \ : ■ Y - < b Y Y ' 4 , ;. b € . £ Y - y Y Y