Jerome Boykin Interview transcript

Oral History

25 pages

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Interview with Jerome Boykin for the Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project, conducted by Danita Mason-Hogans Conducted in collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Copied!

Legal Defense Fund Oral History Project

Jerome Boykin, Sr.

Interviewed by Danita Mason-Hogans

November 2, 2024

Houma, Louisiana

Length: 01:02:05

Conducted in collaboration with the Southern Oral History Program at University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill

LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute, NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund,

Inc.

2

This transcript has been reviewed by Jerome Boykin, Sr. the Southern Oral History Program,

and LDF. It has been lightly edited, in consultation with Jerome Boykin, Sr. for readability

and clarity. Additions and corrections appear in both brackets and footnotes. If viewing

corresponding video footage, please refer to this transcript for corrected information.

3

[START OF INTERVIEW]

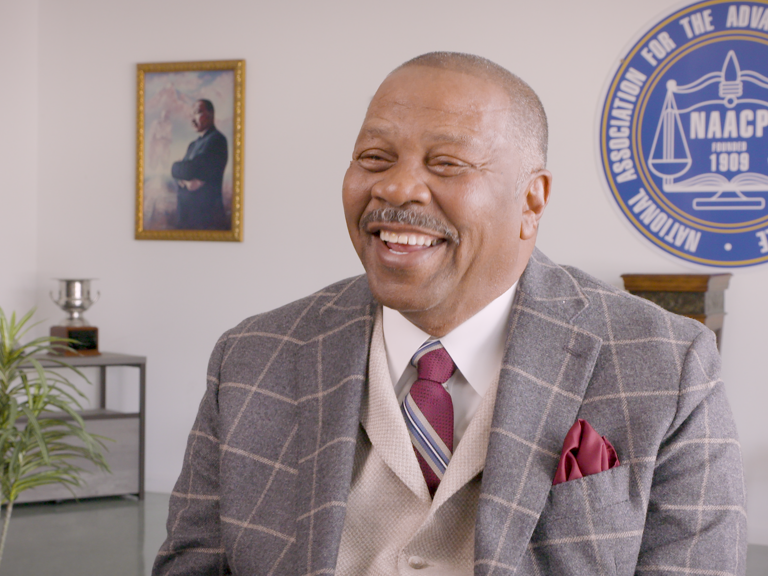

Danita Mason-Hogans: [00:00:00] I'm Danita Mason-Hogans with the Southern Oral

History Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Today is November 2nd,

2024. And I'm sitting here in Houma, Louisiana in the NAACP office with Mr. Jerome

Boykin, Sr., for an oral interview for the Legal Defense Fund. Thank you so much for

coming.

Jerome Boykin Sr.: [00:00:24] Thank you for being here.

DMH: [00:00:26] Thank you. So, Mr. Boykin, I just want to start from the beginning.

If I were taking a trip around Houma in maybe about 1963, [19]64, when you were just a

young person, what would I see here?

JB: [00:00:43] Well, you would see segregation for sure during that time where

Blacks went to all-Black school and whites went to all-white school. You would see some

businesses that had signs that posted "white only."

DMH: [00:01:04] What kind of energy was around the Black community? What were

your elders doing and your teachers?

JB: [00:01:13] I went to a segregated school. It was Southside School. It was all

Black school. All your teachers was Black. The whole faculty was Black. All of the students

was Black. And during that era, that's just the way things were at that time.

DMH: [00:01:33] Now, you went from an all-Black elementary school, and then your

father filed suit for the integrated schools. Do you remember much about that?

JB: [00:01:44] Yes, my father, Camden Boykin, and my mother, Hazel Boykin, they

were fighters in the community. They helped African Americans to register to vote. They

helped African Americans with jobs. And things just wasn't fair back then. And my parents

decided to file a lawsuit through the NAACP Legal Defense Fund to make things better for

this segregated parish, here, Terrebonne Parish.

4

DMH: [00:02:19] Do you remember anything? I think you probably would have been

about six or seven during that time.

JB: [00:02:24] Yes, I was seven years old. I do remember my mother and father

sitting down with my sister, Connie Boykin, and telling us that, "Kids, you all are going to be

going to a all-white school." And my sister and I looked at each other, "All white schools?"

[we] said, "Mama, we like the school we are going to. Why do we have to go to a all-white

school?" And she clearly told us, "Listen, you're young. You may not understand now what's

going on, but things have to change and you are going to be a part of that change, and we're

going to be right there with you. Don't be afraid. It's not going to be easy, but we're going to

be right there with you. "And my sister and I really, at the time, didn't know what to expect.

Several kids in the neighborhood's parents who came to our house and said, "I'm going to

send my son. I'm gonna send my daughter." So, we kind of felt at a little ease because we felt

we wasn't going to be the only one. But, boy, when that day came, only two other kids

showed up. It was the late Nolan Douglas, was one of the kids and also Doris Brown. So, it

was four of us that went to West Park Elementary School on that first day to integrate an all-

white school.

But it wasn't nice. We had to endure a lot of racism. And what I mean by that is, white

kids would refer to us as "n----r boy," refer to the Black girls as "n----r girls." We would get

in fights at school. At that time, we felt that the teachers could have intervened a lot quicker

than what they did. They took their time in breaking us up from fighting. The girls went

through racism also. But it was harder on the two Black males, myself and Nolan Douglas.

Matter of fact, when we went to the restroom, Nolan and I, we had to watch out for each

other while we used the restroom. Because what would happen is that all, white kids, they

would all barge in, call us "n----r," push us. And, you know, we would get into scuffles. And

then the teachers and all would come in later and stop us. When they would call us names, we

5

would go to the principal if we would see him, or go to the teacher that's on duty for recess.

And they basically just shunned us off and said, "Don't worry about it.” Turned their back.

And we basically was on our own. Now, our parents did patrol the school to where for recess

they would pass in the car and look to see, you know, what was going on with us.

DMH: [00:05:55] Mr. Boykin, I can't imagine what that must have been like to go

from your segregated school to the desegregated school. And I think you mentioned as a child

that you said you didn't want to leave your school. What did you like so much about your

school, and how was that to make that transition to another school that must have felt unsafe?

JB: [00:06:19] Well, what I liked about school, segregated African American school,

that I was going to, everybody there looked like me. Everybody there got along. It was no

problem. It was harmony among the people who I went to school there with, from the

principal to the teachers. If you needed help with anything, they would help you. There was

no name calling, and it was people that I was used to being around. It was people from my

neighborhood. It was people that I would see every day. So, it wasn't a problem, you know,

going to the segregated African American school. But something my mother told me that, at

that time, truly I didn't understand going from a comfortable environment to an environment

that was bad. One of the things I remember as a young child, the very first day of school, my

mother took my sister and I, and we had to report to the office. And, there's the parents in

there with their kids also. So, we sitting there waiting with my mother to sign the papers and

all, for us to go to the all-white school. And I'll never forget, there was a little girl, a white

girl that was with her mother and she was crying. And she said to her mother, "Mommy,

mommy, I don't want to go to school with these n-----s." And the mother told her, "Shut up,

Be quiet." And she said, "No, Mommy, Mommy, I don't want to go to school with the n-----

s." And the mama answered the little girl. And she said to her daughter, "Listen, listen, you

got to go to school with the n-----s, because the n-----s is everywhere." Yeah.

6

DMH: [00:08:40] You were seven years old when you heard this conversation?

JB: [00:08:48] Seven. And also, I remember my mother making a smart remark

behind me: "You're damn right."

DMH: [00:09:00] She said she overheard the woman say that to her?

JB: [00:09:03] Right. Right.

DMH: [00:09:06] Let's talk about your mom for a minute. You came from a very

powerful movement family. Do you remember those early days of strategy sessions, maybe

with the Legal Defense Fund people or the neighborhood people talking about this case?

JB: [00:09:25] Yes. I remember people from the neighborhood coming to the house. I

remember an attorney coming, speaking with my mom about what plans that they had in

reference to the school system. I was young. I didn't remember a whole lot about what they

talked about. But I knew as a child something was about to happen because the house was

crowded. It had other kids' parents there to have a meeting. And when I would play with

some of the kids in the neighborhood, they would talk about that we would be going to a new

school. But I didn't know all of the particulars of it. I basically just noticed as a kid that

something was different because we never had that many people at our house, and it wasn't a

party. It was just parents from the neighborhood who came and spoke with an attorney. At

that time, I do remember, remember that. I don't remember the conversations because

sometimes I would be in there, and sometimes I would be out playing.

DMH: [00:10:53] You talked about the treatment in the conversation between the

little white girl and her mother. Do you remember anything else about that first day of

school?

JB: [00:11:05] Yes. After that incident happened and my mother walked us to class—

and being there—the teacher did say, “We have a new student.” And [she] called my name.

And where I was sitting, I think in the middle part of the class. "We have a new student and

7

his name is Jerome.” And she asked the kids, you know, “Everybody say 'Hi' to Jerome." The

reaction was not welcoming. Some kids did say it under their breathe, low. But you would

think, with probably 30 kids in class, that it would be loud enough for everyone to hear. And

just sitting there and being there and stuff like that. And they wouldn't speak to you. You

basically was on your own. Even the teachers said little to you; they didn't say much.

DMH: [00:12:24] Did this continue throughout the school year, or did it get better?

JB: [00:12:30] It got better as far as making friends with some of the white kids that

would call you the n-word. Some of the white kids that would fight with you. Going there

and experiencing that--it was so many white kids that would want to fight you and say ugly

stuff to you. It wasn't the whole school, but it was so many you would think it was the whole

school. It was just that many. And as time went on, some of the white kids end up becoming

friends with you, liking you a little more to where they wasn't calling you a name. The two

people that we had, as far as the two males, some ended up coming on our side.

DMH: [00:13:27] You mentioned the patrols. Was that folks in the neighborhood?

JB: [00:13:32] Yeah, it was. My mother would do it. My father and the other two

kids' parents, Doris Brown and Nolan Douglas. The parents would take turns and just patrol

the school, and they never stopped, just pass to see exactly what was going on.

DMH: [00:13:52] What other things did your mom do to encourage you to be in that

tough situation?

JB: [00:13:58] Well, she did tell me that I was too young to really, fully understand.

And that one day that I would truly understand what was going on. I didn't want to go to

school. And I mean, who would want to go to school under those circumstances? So, as a kid,

you know, I would tell her, "Mom, I don't like that school. They call you names and all. And

I don't want to go to that school." And she would say, "Listen, you have to go to that school.

So, you might as well make up your mind. This have to happen. I know you're young, you

8

don't understand, but one day you will. And the purpose of sending you to that school is to

make it better for everybody."

DMH: [00:14:49] Do you remember anything about those attorneys from the Legal

Defense Fund? Did you spend much time with them or was it primarily with your parents that

they had these discussions?

JB: [00:14:59] Well, what I remember about it the attorneys, that they were white

attorneys who came to the house and speaking with my parents about making this happen.

And the reason why knowing they was there for that, because my mother told me, you know,

"We have these lawyers who is going to help us, and they are good lawyers, and they want to

do the right thing." And she also said that, "These are some of the best lawyers." I have

always remembered that, "Some of the best attorneys in the world."

DMH: [00:15:40] So what were your impressions as a little kid when you see these

two white lawyers come into your house?

JB: [00:15:45] I mean, it gets your attention, you know, like something very

important is going on when you see lawyers.

DMH: [00:15:56] Did you hear your parents discuss any strategies? I know that you

said that initially there were a lot more people in the neighborhood who had said they were

going to go.

JB: [00:16:10] Yeah, I had my mother and father talk about this often. They were

disappointed to the fact that they felt that we had probably 30 to 40 kids that was going to go

that day to integrate the school. And up till the last day, like I said, it was only my sister and I

and two other kids. The four of us showed up to go and integrate the schools. I remember my

mother saying that she spoke to some of the parents and asked them just "Why? Why did you

all wait till the last minute to back out when we had a plan to do this together?" Some of them

said that they felt that some of the whites in the community wouldn't keep them on the job.

9

They would be considered troublemakers. Things were going good in the town, and that they

would be considered troublemakers by interrupting the "good old boy" racist system that at

that time that we had. And they felt that the whites wouldn't give them work and they

wouldn't have a financial income if they are blackballed in the community because they send

they child to an all-white school to integrate it.

DMH: [00:17:53] But y'all did win?

JB: [00:17:55] Yes.

DMH: [00:17:56] What was that like? Was there a celebration during that time? Do

y'all remember talking with the lawyers? What was that like?

JB: [00:18:02] I remember my mother and I were talking with the attorneys, and my

mother was happy at the fact that we still went forward in spite of more than 90% of the

people backing out of it. And my mother always said, "If it's only two going to integrate it,

it's going to be my two, if no one else shows up." As a kid, I didn't have any other choice, to

be honest. My choice was not go to that school if I could have made that decision myself. But

of course, my mother made that choice for me. And looking back on it now, I'm happy that

we did.

DMH: [00:18:50] So, Mr. Boykin, you're saying you'd rather face white supremacy

than making your mom mad? [laughter]

JB: [00:18:55] [laughter] Yeah. It's hard to say anything and do anything any

different when you don't have any other choice. At that age, seven years old.

DMH: [00:19:07] So, do you know if your parents kept in contact with the attorneys?

JB: [00:19:14] I know there was a lot of talking with the attorneys. She had a good

relationship, her and my father, with the attorneys from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. My

mother was so proud to make that happen. And one of the things my mother liked was the

fact that she had attorneys that was willing to make this happen.

10

DMH: [00:19:46] How old were you, Mr. Boykin, when you lost your father?

JB: [00:19:50] I lost my father the very next year. I was eight years old. My father

drowned, him and another friend of his, on a fishing trip.

DMH: [00:20:05] That must have been a very, very difficult time.

JB: [00:20:07] I was. It was difficult.

DMH: [00:20:11] But in spite of that, you started working very early, right, you had a

paper route?

JB: [00:20:19] Yeah. Matter of fact, that was my very first job. I had a paper route. I

established a paper route in my neighborhood and went around and got subscribers and built

my own paper route from the ground up. I started the very first paper route in my

neighborhood.

DMH: [00:20:43] Would you tell us a little bit about Mr. Miller?

JB: [00:20:45] Mr. Miller was a gentleman that I met early on in my life. He was the

guy that was in the community that would work a lot of the young kids, including myself. Mr.

Miller was a guy that owned a lot of rental property. And he needed kids in the neighborhood

to paint for him, to cut grass, to do things that he needed to do at his property. Mr. Miller had

several rental properties, and I was one of the kids that would go to his house early, early in

the morning and get in the truck and haul off to work in the neighborhood.

DMH [00:21:31] I am really struck by how you were surrounded by such strong,

positive role models for you. And how were you paying attention to what was going on with

your mother and your father fighting for civil rights and Mr. Miller having that strong work

ethic, how did that impact you?

JB [00:21:51] Yes, I think several people impacted my life, but I got to see my

mother, out of all the people that impacted my life. My mother was a strong Black woman.

And she didn't--she wasn't afraid. At all.

11

DMH [00:22:16] So. I'm wondering how much of your mom's strength went with

you, and that determination when you decided to join a career in law enforcement early on?

JB [00:22:28] Yes, I got my job at my mother's house, because the sheriff came over

to visit her. And my mama told the sheriff, "My son need a job. He just got out of high

school. So, the sheriff said, "Sure, we need people like that." And that's where I got started. I

ended up going to the Police Academy and graduating and becoming a member of the

Sheriff's Department. Even doing that, I was in for a rude awakening because being a Sheriff

Deputy was something that I always wanted to do, to be honest with you. Because I felt the

sheriff should be someone who would uphold the law, do the right thing, treat everybody

nice. But once I started working there, I was in for a rude awakening. I found out that even a

lot of the deputies that I even worked for, when they would be in a squad room talking, either

before going on patrol or after a shift, you would hear them refer to Black people as "n----r

this" and "n----r that." One of the things that I did as a Sheriff Deputy, I would complain to

my superiors and tell them that I didn't appreciate working with people that's not going to be

fair to everyone and working with people that's not going to treat everyone right. And I just

had concern being an African American law enforcement officer after hearing some deputies

say stuff like that. What concern I had was, the fact that, here's the guy that's making these

racial statements, is the same guy that I would have to depend on backing me up if my life is

in danger. So, it was some of the things that I went through working for the Sheriff'’s

Department.

DMH [00:24:44] I think your mom wanted you to join the department and

encouraged you to get the job. What were her thoughts about some of the things that you

were going through?

12

JB [00:24:54] She told me it was a part of life, and that you have to fight for what you

believe in. And she said, "Jerome, it's not what names people call you. It's what names you

answer to." And that always stuck with me.

DMH [00:25:15] I think your mom was a very determined woman, and it seems like

she had expectations of fair treatment. Could you talk a little bit about that?

JB [00:25:23] Yes. I think I got a lot of that from my mother because coming up, she

had always been a fighter. You know, you're either right, or you're wrong. She fought racial

discrimination all of her life, and my mother didn't have fear. If someone wasn't treated right

in the community, you know, she would go down to the courthouse and talk to the judge, talk

to who she needed to talk to, about whatever incident that may have happened in the

community. She just, for a Black woman, she did not have fear at all.

DMH [00:26:14] How did your interaction with the police department, your

experience in law enforcement, how did that impact, or, did it impact, your decision to

become president of the NAACP? Could you talk a little bit about how those two things?

JB [00:26:31] I think growing up as a boy, going to a segregated school, integrating

an all-white school, being involved in the Sheriff's Department and facing racism as a young

Black man, all my life, I felt I knew many of the problems in the community because I lived

it all my young life. So, I felt that it was time that I would be in a position that I can help the

community as a whole.

DMH [00:27:11] So beginning in 2014, you worked with the Legal Defense Fund,

and this time you are an adult. LDF filed a lawsuit on behalf of Terrebonne Parish Branch of

the NAACP for individual African American voters. The local cooperating attorney was

Ronald L. Wilson, who was working with the Legal Defense Fund, and was working with

Leah Aden. The suit was filed under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and the 14th

Amendment to the US Constitution, and they were aimed at six unsuccessful legislative

13

attempts in 30 years of advocacy. The suit claimed that the at-large system, in combination

with racial bloc voting, prevented Black voters from electing the candidate of their choice.

So, would you kind of summarize that for me, and then tell us about the voting rights and the

civil rights battle and the role of the Legal Defense Fund, as well as their efforts?

JB [00:28:16] Yes, the Legal Defense Fund came in because we had a serious

problem here in Terrebonne Parish with at-large voting. We was able to prove through an

expert that Terrebonne Parish had polarized voting, which means that when African

American candidates ran for office and white candidates ran for office, that Blacks would

vote for Black candidates and whites would vote for white candidates. And we was able to

prove that, at that time, we wasn't able to elect any African American candidate at-large. We

had some in the past. We have [had some who] ran for mayor, some who ran for sheriff,

some who ran for census, some even who had ran for judge. And we wasn't able to elect an

African American at-large, because of the polarized voting that we had here in Terrebonne

Parish.

DMH [00:29:29] So I believe the Black residents of Terrebonne are about 19 to 20%

of the population?

JB [00:29:37] Right.

DMH [00:29:39] Could you just talk a little bit about that history of

disenfranchisement, and why this system of at-large did not work for the African American

citizens?

JB [00:29:50] Because of polarized voting, over the 30 or 40 years, like I said earlier,

African Americans voted for African Americans and whites voted for white candidates. And

without the federal government coming in saying that you have to have African Americans to

serve on school boards and also serve on the councils, we wouldn't have any African

Americans serving in office.

14

DMH [00:30:25] So let me make sure that I understand this right. At-large voting

would mean that you would only have 20% of the vote, so if white folks get 70% of the vote,

you would never be able to have anybody?

JB [00:30:39] You couldn't win because of polarized voting. You know, we voted for

African American candidates, and they voted for white candidates. Those numbers at large

could not work out. Just looking at the numbers game itself. And that's a reason why the

federal government came in and was able to create these minorities opportunity districts for

the council and for the school board.

DMH [00:31:11] Could you talk about an opportunity district and what that is?

JB [00:31:14] Well, an opportunity district is a district that’s made up of roughly at

least 50% of the voters in that district would be African American in order to have a fair

chance of an African American being elected to that district. And that would be the purpose

of creating what they call an opportunity district. It would give an African American an

opportunity to win. It won't guarantee an African American win, but it would give a better

opportunity, [as] opposed to the at large voting.

DMH [00:31:55] So could you describe your interactions with the Legal Defense

Fund attorneys as an adult? How do they work with the community for this case?

JB [00:32:04] Leah Aden was one attorney that I dealt directly with. I mean, they

came into the community, spoke to people in the community. They were able to bring in

experts to take a look at voting in this area. And the experts decided, based on their expert

opinion, that it was clear that Terrebonne Parish had polarized voting. I think Leah did a

wonderful job with the attorneys that she worked with, with the NAACP Legal Defense

Fund, and we won our case in federal court with Judge Brady. The judge did rule that

Terrebonne Parish shouldn't have just at large voting. They should adopt an opportunity

district to give an African American candidate an opportunity to run for office and win. But

15

as you know, once we won on a trial level in court, it was appealed by the Attorney General's

office, and we end up losing this case based on the appeal. Now, the Appeal Courts that heard

the Terrebonne case, we know we had an uphill battle because they were known to rule in

racist ways when it comes to these types of districts being created for minorities.

DMH [00:34:09] Let's talk about what you had to do in 2020, when they reversed the

decision, and what you had to prove and what you had to talk about, the situations that folks

were living here in, and the type of people who were governing and making decisions for

people around here. That played a large part into your eventual victory. Could you talk a little

bit about that?

JB [00:34:33] As far as what part?

DMH [00:34:35] Maybe the judge, the judge that was very racist and demonstrably

racist. I think y'all pulled out some stuff that the judge had been doing that was—

JB [00:34:53] Well, as far as the system went, we had a local judge. He's retired now,

Judge [Timothy] Ellender was a District Judge. He dressed up one day for Halloween. He put

on an orange jumpsuit. He painted his face black. He put on an African American Afro wig.

His wife or girlfriend dressed as a correctional officer. He was in handcuffs, and she was

leading him, stating, basically, "You got to stop all that stealing and killing and stuff that

you're doing in our community." Matter of fact, we filed a complaint against that judge, and it

went up to the Supreme Court, and he was suspended off of the bench for six months to a

year without pay.

DMH [00:35:53] I think you described it as a "David and Goliath" type of situation,

from like the normative practices that were going on in Houma and really some of the things

that you had to face and overcome in this legal battle.

JB [00:36:07] Right. One of the things, too, in law enforcement that I experienced

that deals with the court system, sometimes I would have to be in court, and it was obvious,

16

some of the cases that would go up before it was my turn, and you would see African

Americans where--the judges, the time that they would give them, opposed to their white

counterpart, to where African Americans would receive more time, basically for the same

crime, than their white counterpart. And that was one of the things that I experienced as a

Sheriff Deputy.

DMH [00:36:51] Well, your experience as a Sheriff Deputy seems like it really

helped you, as you were governing the NAACP, as you were NAACP president.

JB [00:36:59] Right.

DMH [00:37:00] Could you talk a little bit about how that prepared you to talk about

what was legal, what wasn't legal, and some of the things that you experienced?

JB [00:37:08] Well. Being a Sheriff's Deputy and experiencing all of the racism that I

did doing that and coming up as a young child under racism. I've been Black all my life, and

I've experienced racism all my life. What it helped me with, knowing some of the problems

that you have in a community when you experience stuff on a different level, from a child to

an adult. That's the reason why we were successful here at the NAACP fighting racism in the

community. Because I've lived in the community all my life. I experienced racism all my life.

So, I was able to know exactly what we needed to attack in our community. And one of the

other things that we attacked was the Mardi Gras krewes here in Terrebonne Parish, too,

where when I was president, none of the Mardi Gras krewes included African Americans.

And one of the things when we sent a letter down to the president of the krewes to meet with

them in reference to that. Their argument was, "Hey, you don't tell us what to do. We are a

private entity. You know, I can bring you our bylaws to show you just how private we are.

So, you don't have anything to do with us." But they didn't realize what we were getting at.

So, meeting with them and hearing them say that they are private and we don't have anything

to do with them. One of the things that we said, as far as our position in reference to them

17

being private, we said, "Okay, sure, you are private, but you're not as private as you think you

are." So, "Mr. Boykin, what are you talking about? I have my bylaws here!" I said, "Well,

that's your bylaws. I say if you're so private, why don't you parade on private property?" I

said, "The streets that you parade on is paid for by taxpayers. So, when you talk about being

private--" and I said, "Another thing, when you're parading on our streets, the police

protection that's there on the street. Guess what? It's paid for by taxpayers' dollars." I said

"Also, the mess that you leave on the street and the garbage collectors that pick it up, guess

who is paying for them? It's paid for by taxpayers' dollars." So, my argument was, you're not

as private as you think you are.

DMH [00:40:00] I think that's so excellent. What I would like for you to do, is talk

about how powerful that whole system of krewes is. For people like me from North Carolina,

we don't know about krewes and how--I know that Mardi Gras is such a big industry down

here. Would you just talk about the whole krewes system, how that is, and a little bit of the

history of it?

JB [00:40:24] The power of krewes is the fact that the people who are members of the

krewes are your judges, are your people that owns your car dealerships, attorneys, and these

are people that make decisions on people's lives. So, you would wonder, "Why would people

like that be a part of a Mardi Gras krewe?" They yet discriminate against people that they

have to deal with or come in contact with. So, when I'm asked questions, "Why deal with the

krewes?" My answer is any type of discrimination is wrong. There's no such thing as, "Some

discrimination is not as bad as others." All discrimination is wrong. And it was our job to root

out all discrimination that we possibly can. And that was one of the reasons why we fought

the Mardi Gras krewes and was able to win and to also have it to where all the krewes now

are integrated. And one of the other things, in reference to the krewes, that I felt was wrong

when it comes to discrimination. If you had a young child that was in the high school, junior

18

high band or a high school band, that child can march for four years in the parade with that

krewe. But once he or she become 18 years old, he or she cannot become a member of the

same krewe that they've been parading with for four years. That just ain't right.

DMH [00:42:08] Why would they say that? Why would why would that be in place?

JB [00:42:12] The thing with that is, our argument was the fact that, if you were in

junior high school, because they all march in the parade. And if you do that from junior high

to high school, once you graduate from high school, the same krewe you've been parading

with for four years, you can't even become a member of that krewe. That just ain't right.

DMH [00:42:35] Well, what reason did they give that you couldn't do that?

JB [00:42:40] What reason? They can discriminate without a reason. And what I

mean by that is, some of them ask for, if you want to become a member of a certain krewe,

you fill out an application, you turn in your picture along with your application. So, it's easy

to know who you are. They have your picture. And the ones that don't ask for pictures,

wherever you go and bring your application to, or whoever you go to, to get an application,

that they know who you are. It was a "good old boy" system for many, many years. And my

thing was, "It's okay for us to help pay for your party, but we can't be a part of the party that

we helped pay for?"

DMH [00:43:30] Mr. Boykin, you certainly inherited your mom's fearlessness. And

talk a little bit about how you have been so fearless in these situations and where that comes

from.

JB [00:43:45] Like I said, it comes from my mother and growing up in the household

that I did, with someone who was so fearless, someone who spoke her mind, regardless to

who she spoke to, when she felt she was right. There was nothing that was going to stop her

from telling you exactly how she felt.

19

DMH [00:44:06] Do you think that there has to be a certain level of fearlessness to

fight social justice? And did you see that with your fights and use that within your fights in

the NAACP? And did you see that in your attorneys?

JB [00:44:19] Oh yes. You have to be fearless if you're going to challenge, if you're

going to speak truth to power. You know, and one of the things being in the NAACP, like I

told you earlier, helped me a lot. And one of the ways it helped me is the fact that, I knew

financially, I had to create businesses that would financially support my family. Because if I

had to depend on the powers to be, for a job, to receive financial help. How can you fight

someone that you need financially? How can you go all out and fight someone when you're

dependent on financial support from them? So, the fact that I was able to establish two

businesses helped me a lot, being more independent. And being more independent, it gave me

an advantage to do what I needed to do as president of the local NAACP.

DMH [00:45:30] Will you talk a little bit about--the young people say, "Game

recognize game." Could you talk a little bit about that fearless spirit that you saw with the

attorneys, with the Legal Defense Fund?

JB [00:45:45] Oh when they came, and they spoke, and based on the history of the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund, I knew we were in good hands with the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund. Based on their history, based on what they did for us here in Terrebonne

Parish, I had no doubt in my mind whatsoever, that I knew that we had some of the best

minds that we needed to fight racism here in Terrebonne Parish.

DMH [00:46:25] One of the things that I appreciate so much is your work with the

NAACP, with raising scholarships, but you not only raise scholarships for young people, you

also raise scholarships for people who were incarcerated. Would you talk a little bit about

your scholarship and your giving?

20

JB [00:46:42] The deal with the scholarships, we give away over $33,000 a year [to]

kids graduating from high school, going to college, which I think is very important. What

better way to raise money than to raise money for education? And that's the reason why we

do what we do when it comes to our youth chapter. We want to make sure that we raise that

money every year for those kids to go to college. One of the other things with my law

enforcement background, I was able to get four people out of prison who had a life sentence.

Cases that I knew they shouldn't have been convicted and found guilty of, but I was able to

go before the pardon board, fight for their freedom and get their freedom.

DMH [00:47:44] I think that's some wonderful work that you do, and sometimes you

partner with people. I think you can partner with a famous person, Master P, in doing some

work in the community. Could you talk little bit about that?

JB [00:47:56] Yeah, we had Master P. Matter of fact, I met Master P through his

brother Silk. His brother Silk and I were close friends. I met Master P, and now Master P and

I are more close than Silk and I! But I had Master P down as a guest speaker, and from that

day, we became best of friends. Master P is someone I talk to two or three times a week. We

get Master P down here in Terrebonne Parish to do a back-to-school giveaway at one of the

poorer schools in the parish. We get him down here to also do a Christmas giveaway to the

kids at Oaklawn Middle School here in Terrebonne Parish. And to be honest, I’ve learned a

lot from Master P, being friends with him, talking about finance, talking about different

businesses. And he's really a bright guy, to be honest with you. And he's been doing good

things. And what I like about him, and people wouldn't know this about Master P, Master P

talk about God all the time. And I've found out being close friends with him, how much he

love God and how much he believe in God. And I think that has helped Master P a lot, his

religion.

21

DMH [00:49:40] Mr. Boykin, what do you think is the lasting impact of your work

with the NAACP? The schools are desegregated because of the efforts that your parents

started. What do you think that your lasting impact has been with the NAACP?

JB [00:49:57] I think my lasting impact is going to be that I did all that I can do as

president of this great organization, that we fought the powers to be and won. And as long as

I'm president, we're going to continue to fight racism here in Terrebonne Parish. And I don't

plan on stopping.

DMH [00:50:22] What do you consider to be the legacy of the school integration

efforts that your father started? What do you think that legacy is?

JB [00:50:32] I think it's going to go on for forever. Without the lawsuit, who knows,

we still may be segregated. And the thing is, back in that era, for someone to have the nerves,

and the wisdom, and the guts to do what my parents did to integrate the schools here in

Terrebonne Parish, I think is going to have a lasting effect on this community.

DMH [00:51:10] Could you talk a little bit about the legacy of the Legal Defense

Fund for going across the country to do this type of work, with school integration, we don't

often think of it, those of us who were not part of a segregated school system. If you were

talking to somebody and you were talking about how important this work was that the Legal

Defense Fund did for school desegregation, what would you say to them?

JB [00:51:44] In all honesty, I don't know where we would be without the NAACP

Legal Defense Fund, as African Americans in this country. I don't even want to think about it.

DMH [00:52:04] So, what do you think about school desegregation now?

JB [00:52:09] I'm glad that it happened. We still need to change some things in our

system when it comes to schools. But I'm glad it happened years ago when the Legal Defense

fund came to Terrebonne Parish and filed this suit on our behalf. As time goes on, things is

22

going to change, I think, even for the better. We have come a long way, and yet we still have

a long ways to go. In all honesty, it ain't perfect, but it's better than what it used to be.

DMH [00:52:50] So, what do you think is the area that really needs the most focus in

civil rights legislation right now?

JB [00:53:00] When it comes to civil rights legislation? It's so much. Voting rights.

You know, we still have the John Lewis Bill. Here we are, 2024, [and] Congress still hasn't

passed it yet. That's very important. And it's odd that in 2024, we still have to talk about

voting rights.

DMH [00:53:29] Do you think that's the area that's most needed, where change is

most needed, or are there other areas where you think change is most needed?

JB [00:53:36] I think it's other areas. When it comes to the killing of unarmed Black

men. It's not just one thing. It's other things that we need to continue to, you know, to fight

for, even when it comes to fair housing. 2024! You know, even when you talk about health

care. It’s still a lot of things that we need to fight for.

DMH [00:54:12] So, what else do you think you'd like to accomplish as the president

of the NAACP with your work in the local community in terms of civil rights and social

justice?

JB [00:54:27] My job never changed. From the beginning until I retire, it's to continue

to fight for equal rights for everyone.

DMH [00:54:46] What do you think the LDF can do to continue to do meaningful

work in the community?

JB [00:54:50] I think the NAACP Legal Defense Fund continue to do the things that

they've been doing all along. And that's to continue to go around the country and fight racism

through the court system head on, as it's been doing for many, many years. Like I said,

23

without the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, I often wonder, "Where would we be as people?

Where would we actually be if we didn't have them?"

DMH [00:55:27] Mr. Boykin, one thing I really appreciate is your sense about things.

I think you have such a good keen sense about things. So, we look in the past, we talked

about what you're doing now.

JB [00:55:40] Right.

DMH [00:55:42] What is your sense about how this legal framework, how the work

of the Legal Defense Fund and the NAACP, what kind of work do you think is going to be

needed later on in the 21st century?

JB [00:56:00] I think, even with what's going on now, I think our Supreme Court is

more political than it has ever been in the history of the Supreme Court. When we talk about

civil rights and other rights, one of the main things to we're fighting [for] is women's rights,

where, in America, women today have less rights than their grandparents had. And it's really

a sad day in America when a court give a president immunity to basically do what he want to

do. You know, I think that the NAACP Legal Defense Fund is needed more now than ever.

When you have a court that, in my opinion, is going the wrong way.

DMH [00:57:18] Now. I'm going to ask you-- Did you want to say something?

JB [00:57:21] No.

DMH [00:57:22] Now I want to ask you, when you say "I'm proud to be from Houma,

I love where I'm from," Tell me what you love about it and why you're proud to be from here.

JB [00:57:34] This is where I was born and raised. Here in Houma, Louisiana. It's not

a perfect community. I don't know of a perfect community anyway. But it's good to be in the

community. And when you want to change things in your community, that's not right, you get

involved and you fight the good fight, to help make it right when it's not right. But I still say

this is a good community. Do we have problems? Yes. Are we perfect? No, we're not. But I

24

still plan to stay here and fight the good fight as long as I can fight it. To make it better for

my kids and grandkids. Someone made it better for me. I need to make it better for others.

DMH [00:58:32] Mr. Boykin, if a young person were to say to you, "All that civil

rights stuff was back in the past, I don't feel like I need to join the NAACP, I don't need the

Legal Defense Fund." What would you say to them?

JB [00:58:47] What I would say to them is that. That is someone to me with bad

understanding. And what I would say to them is, here we are 2024 and we can't get the John

Lewis Voting Rights Bill passed. In 2024. And what I would say to them, your mother, your

wife have less rights today than your grandfather, your grandmother. When it comes to

women's. Less rights. A woman should have the right to choose what happens to her body.

And I never heard anything when it came to men having a right to choose about their body.

But yet we single out women having a right to choose. So, if someone would say that to me, I

would say to them that, they don't understand.

DMH [59:45] Okay, so you explain it like that, Mr. Boykin, I understand, I'm going

to sign up, I'm going to join. What can you give me from your fearlessness? What kind of

things do I need to gird myself up as a young person? Using some of the tools that you have

with the Legal Defense Fund and the NAACP and your tenacity and your strength. If you’re

putting the armor on, what would it be?

JB [01:00:24] What it would be if someone would want to join, a young kid—and I

sign up kids all the time—I'd say, "One day, you could become president of the NAACP.

You need to join us to find out what we do, how we do it. Come in as a young man as I did

and help make your community better." Saying you would do this, or you would do that and

not get involved, but have a lot to say, doesn't help your community. If something is not right,

you join an organization to make it better, to bring in new ideas. I don't know everything.

Some of the ideas that I've gotten was from some of the young kids that I've spoken to, to be

25

honest with you. Because a lot of our youth do have good ideas. We just have to listen to

them and not think we know it all. Just like they can learn from us, as an adult we can learn

from them.

DMH [01:01:33] Love that. Mr. Boykin, what did I not ask you that you would like to

speak on? What's important to you to speak on?

JB [01:01:43] I think you covered everything that you wanted to cover! I think you

had a plan and you implemented your plan!

DMH [01:01:52] Well I'll take that as a great compliment! [inaudible] I enjoyed our

conversation.

JB [01:01:58] Yeah, me too.

DMH [01:01:59] Thank you so much, Mr. Boykin.

JB [01:02:00] No, thank you. I appreciate you.

DMH [01:02:03] Thank you.