Yarbrough v. The Hubert-West Memphis School District No. 4 Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 15, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Yarbrough v. The Hubert-West Memphis School District No. 4 Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1971. 06702ba9-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1217e890-e452-43a9-ac3a-cb888641bdf2/yarbrough-v-the-hubert-west-memphis-school-district-no-4-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

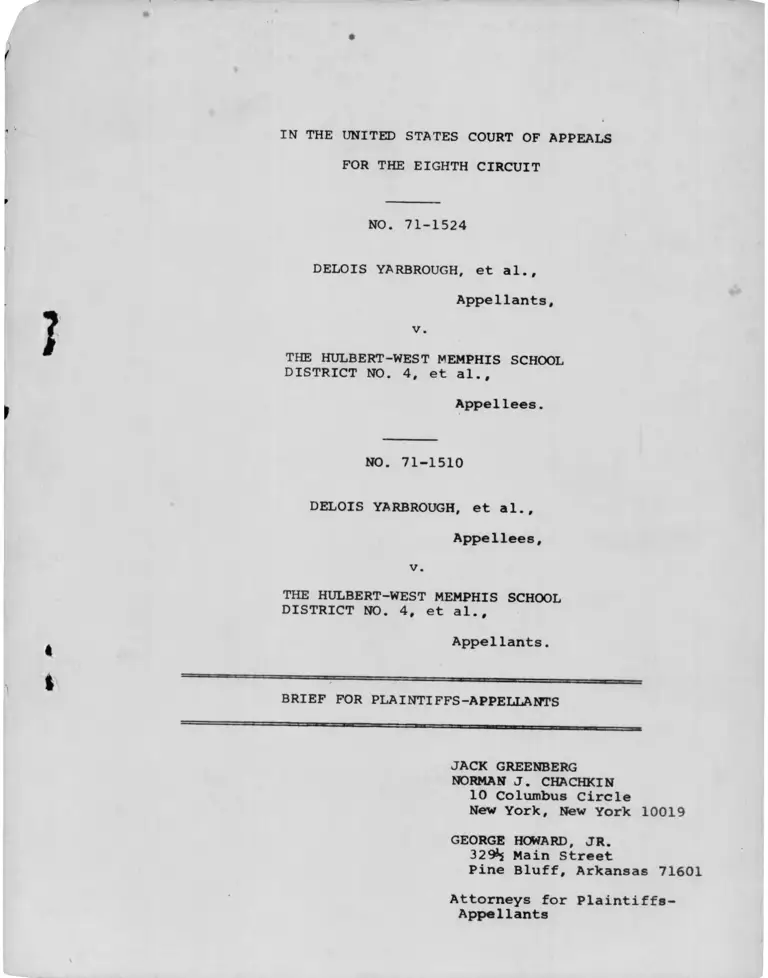

NO. 71-1524

DELOIS YARBROUGH, et al..

Appellants,

v.

THE HULBERT-WEST MEMPHIS SCHOOL

DISTRICT NO. 4, et al..

Appellees.

NO. 71-1510

DELOIS YARBROUGH, et al..

Appellees,

v.

THE HULBERT-WEST MEMPHIS SCHOOL

DISTRICT NO. 4, et al..

Appellants.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329*5 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appe Hants

INDEX

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT................

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW..........

STATEMENT....................

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT'S REQUIREMENT

THAT A THIRTY PER CENT MINORITY

ENROLLMENT BE MAINTAINED IN EACH

SCHOOL IS ILL CONCEIVED AND FAILS

TO CREATE A UNITARY SCHOOL SYSTEM

IN WEST MEMPHIS ................

CONCLUSION........

TABLE OF CASES

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock-

426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970) ...............

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, No. 71-1409

(8th Cir., Sept. 10, 1971)...................

Davis v. Board of School Commr's of Mobile

402 U.S. 33 (1971).................. [

Davis v. School District of Pontiac, 309 F.*Supp!

734 (E.D. Mich. 1970), aff'd 443 F.2d 573

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, ___ U.S. (1971)..

Green v. County School Board of New Kent Countv

391 U.S. 430 (1968)..................... ..

Kemp v. Beasley, 423 F.2d 851 (8th Cir. 1970)..... .

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educ 402 U.S. 1 (1971)..................

Whitley v. Wilson City Board of Educ., 427 F 2d 179

(4th Cir. 1970)....................... *......

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School District

380 F. 2d 962 (8th Cir. 1967)...............

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School District,

243 F. Supp. 65 (E.D. Ark. 1965)........... [.

15

16

13,14n

13

11,12

15

3,4,12,

16

9

2

2n, 13

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-1524

DELOIS YARBROUGH, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

THE HULBERT-WEST MEMPHIS SCHOOL

DISTRICT NO. 4, et al.,

Appellees.

NO. 71-1510

DELOIS YARBROUGH, et al..

Appellees,

v.

THE HULBERT-WEST MEMPHIS SCHOOL

DISTRICT NO. 4, et al..

Appellants.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, Hon.

Garnett Thomas Eisele, united States District Judge.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

I* Aether the district court's establishment of minimum

ratio requirements was proper.

2. Whether the plan approved by the district court

fails to establish a unitary school system in West Memphis

because it permits substantially disproportionate student

racial enrollments characteristic of the traditional racial

identity of the schools.

STATEMENT

This^school desegregation case was commenced January 28,

1965 (2a), and was last before this Court in 1967, Yarbrough

— — Hiilbert-West Memphis School District. 380 F.2d 962 (8th

Cxr. 1967), at which time this Court declined to disapprove

the school district's freedom-of-choice plan but directed

greater faculty desegregation.

November 12, 1970, new plaintiffs, members of the class

on whose behalf the action had originally been brought, sought

leave to intervene (5a-6a) alleging that faculty segregation

was continuing and that defendants had not undertaken affirma

tively to dismantle their dual school system (7a-9a). Defendants

did not oppose intervention but suggested proceedings be

stayed pending decision of the United States Supreme Court in

— Citations are to the Appendix herein.

—/ T*le Previous district court opinion is reported at 243F. Supp. 65 (E.D. Ark. 1965).

-2-

Swann v._Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educ.. 402 U.S. 1

(1971) (lOa-lla), and on December 10 the district court

granted leave to intervene (12a).

Statistical information for the 1970-71 school year

requested by the district court and counsel for the plaintiffs

showed (15a) three all-black schools in the system and two

additional schools over 99% black. Four schools had no Negro

faculty members (16a-17a); two schools had two or fewer

white teachers and four other schools had between one and four

black teachers each (ibid.). The district had closed one

formerly all-black school at the beginning of the 1970-71 school

year (18a).

Pursuant to the suggestion of the district court at an

unrecorded pretrial conference and by letter to counsel, the

school district filed a proposed plan of desegregation to

replace freedom of choice on or about February 12, 1971 (75a-

78a). This plan proposed to pair West Memphis and Wonder

Senior High Schools commencing March 6, 1971 (teaching all

students in grades 11 and 12 at the West Memphis school and

all students in grade 10 at the Wonder site); to reassign on

that date all black junior high school students living outside

the West Memphis city limits, who were previously transported

to Wonder Junior High School, to the East and West Junior

High Schools— but not to reassign any white students to Wonder

Junior High; and to implement on that date majority-to-minority

transfer rights for junior high and elementary school students

-3-

(with no guarantee of free transportation for students

exercising transfer rights).

Plaintiffs objected to the selection of West Memphis

Senior High School to house the upper grades, to the sufficiency

of the elementary and junior high school desegregation plans,

and to the sufficiency of defendants' proposed faculty reassign

ments (79a-80a). Following a further pretrial conference,

the district court required submission of a new and comprehen

sive desegregation plan but approved the board's senior high

school and faculty desegregation proposals on an interim basis

for the second semester of the 1970-71 school year (85a-86a).

On April 2, 1971, the school district filed a tentative

"plan of desegregation" for 1971-72 which would have maintained

the pairing of the senior high schools, "gerrymandered,"

"wherever feasible and workable," elementary and junior high

school "geographic attendance zones [otherwise] drawn so as

to assign students to the school closest to their homes,

to increase integration," and assigned at least 25% minority

race faculty members to each school in the system (87a-88a).

Plaintiffs' subsequent objections noted, inter alia, the

district's failure to project enrollments or delineate zone

lines under its plan (89a-90a).

On May 21, 1971, the district court ordered the district

to file another plan for the 1971-72 school year, designed to

meet the requirements of Swann, supra. The district's final

proposal included the following: (1) pair the high schools as

-4-

in 1970-71; (2) zone junior high schools so that each would

47%, 50% and 53% black students, respectively; (3)

zone elementary schools so that two schools would enroll 23%

and 27% white students, respectively, and four schools would

enroll between 65% and 71% white students; (4) assign

faculty substantially in accord with the system-wide ratio

(93a-103a). Plaintiffs objected to the district's plan and

proposed a restructuring of grade levels in the West Memphis

school system so as to close Wedlock Elementary as an identi-

fiably black school and increase the proportion of blacks

attending the traditionally white schools in the system (104a-

107a). The matter was tried to the court on July 6, 1971

(108a-298a).

1*he contentions of the parties at the trial were relatively

simple and straightforward. Plaintiffs' expert witness. Dr.

Michael j. Stolee, whose qualifications are set out in the

testimony (227a-229a), discussed his reservations as an educator

and desegregation expert about the school district's elementary

school plan (233a). These were basically that most schools

would remain racially identifiable, with traditionally white

schools enrolling disproportionately low percentages of black

students and Wonder and Wedlock schools (both formerly black

schools) enrolling disproportionately low percentages of white

students. Dr. Stolee expressed particular concern about the

chances that the Wedlock School would actually enroll the 101

whites who were to be assigned to it; these white children

had previously been transported by the district into West

-5-

Memphis to attend white schools (268a-269a; 287a).

Stolee offered an alternative plan involving the

closing of the predominantly black Wedlock school. The white

students whom the school district would assign to Wedlock

would instead be assigned to Wonder; the black students who

formerly attended Wedlock would be distributed among the

traditionally white elementary schools in West Memphis (252a).

In order to utilize the capacity of each school without over

crowding, Dr. Stolee's plan proposed a grade reorganization,

moving from a 6-3-3 organization to a 5-3-2-2 structure (251a)

He testified that in his opinion the plan was educationally

sound and feasible for the West Memphis school district (271a)

and he pointed out that an increasing number of American

school systems are currently adopting middle school, grades 6-8

programs— the essence of his proposed grade reorganization

(234a-235a).

Defendants called the Superintendent who justified their

plan on the grounds that it provided for the minimum necessary

departure from the principles of neighborhood school zoning

while still representing increased sesegregation, that the

school district did not favor the middle school concept but

believed sixth grade students should remain in elementary

schools, that implementation of grade restructuring and more

transportation would be disruptive, that execution of Dr.

Stolee's plan would require up to five additional buses which

the school district neither had nor could afford to purchase,

and that the Wedlock School was in satisfactory condition, was

-6-

a source of community pride, and ought not to be closed (137a-

145a, 150a-151a, 156a). The only other witness for the

defendants was the principal of Wedlock for some twenty years,

who supported the Superintendent's desire not to close the

facility (222a).

Dr. Stolee estimated the chances of effectuating successful

desegregation to be greater if Wedlock were closed (233a)

and also testified that isolated, rural schools in homogeneously

low-income areas such as Wedlock (202a) do not and cannot

offer an education comparable to that available in the West

Memphis city schools (240a-241a). (The district did not

propose to assign any city children to Wedlock.) Finally, Dr.

Stolee said that he understood the feelings of some of the

black community around the Wedlock School but that their

emotional ties to the school and desire for its retention was

secondary to the need for desegregation, in his opinion (284a).

The district court followed neither the approach taken

by the defendants nor that suggested by the plaintiffs.

Instead, while rejecting the district's proposal as formulated

because it would maintain schools with enrollments substantially

disproportionate to the system-wide enrollment (307a), the

district court modified the plan to impose a minimum 30%

minority-race enrollment requirement at each school and indicated

it would approve the plan as modified (310a).

The school district filed revised attendance zones which

projected at least 30% black students in the formerly white

-7-

schools and at least 30% white students in the formerly black

schools (316a-317a) and the district court approved the plan

(318a). Subsequently, after the 1971-72 school year had

begun but before the filing of a report by the school district,

a group of proposed intervenors brought to the attention of

the district court and counsel the fact that the white student

enrollment at Wonder Elementary School was considerably below

30% (322-323a). The district court by letter directed the

school district to modify its plan (by transferring students

from schools in which their race is in the majority to other

schools in which their race would be in the minority, or

otherwise) so as to maintain the 30% minimum minority enroll

ment (331a-333a), and denied a stay of its order which had

been sought by the school district (324a-330a). The district

thereupon proposed modifications of its plan for implementation

on October 11, 1971 to achieve enrollment shifts (334a-339a)?

the district court approved the modifications on the day that

they were filed (340a-341a).

The report prepared by the district as of October 27, 1971

shows (342a—343a) that as of this time each elementary school

had at least a 30% minority enrollment. However, the three

formerly black elementary schools enroll 63%, 67% and 70%

black students, respectively, while three formerly white ele

mentary schools enroll 57%, 61% and 62% white students,

respectively? the entire system is now 53% black, 47% white

(335a).

-8-

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT'S REQUIREMENT THAT A

THIRTY PER CENT MINORITY ENROLLMENT BE

MAINTAINED IN EACH SCHOOL IS ILL CON

CEIVED AND FAILS TO CREATE A UNITARY

SCHOOL SYSTEM IN WEST MEMPHIS.

It should not be taken as any indication of rough-hewn

justice that all of the parties to this litigation are dis

satisfied with the district court's resolution of the contro

versy. Plaintiffs have appealed because the district court's

order sanctions— indeed contemplates— assignment of students

to the West Memphis public schools in a manner which preserves

the racial identity of those schools. The defendants have

cross appealed the decree which requires them to readjust

boundary lines and make midyear reassignments of students in

order to maintain an artificial racial composition in its

schools (325a). And a group of parents whose children have

been made the subject of that reassignment process (compare

Whitley v. Wilson City Board of Educ., 427 F.2d 179 (4th Cir.

1970)) have intervened seeking provision of transportation

for West Memphis city students reassigned to comply with the

order and maintenance of stable, integrated school populations

(323a). This case may be a rarity among school desegregation

cases in this Circuit: one in which the plaintiffs and the

defendants agree that the lower court's decree is in error.

The real issue on this appeal is what must replace that decree.

-9-

Plaintiffs argue that if this Court agrees that the lower

court's decree is defective because it maintains a pattern

of racially identifiable schools, a fortiori the Constitutional

mandate will not be satisfied by implementing the defendants'

original proposal; we would expect defendants to argue the

contrary.

In fairness to the district court, we should state that

its opinion and its later correspondence reveal substantial

doubt on the part of the court about the efficacy of the plan

approved by its order. See the court's trial comments (294a).

The opinion recognizes the problem with defendants' plan to

be the projected enrollments of 23% and 21% white students

at Wedlock and Wonder, traditionally black elementary schools

(307a). While the court states that it is imposing a higher

minority race enrollment requirement as a modification of

defendants' plan in an attempt to insure a workability which

the court doubts would be achieved by the district's plan

without modification (311a), the lower court goes out of its

way to invite the school district to adopt and submit a dif-

f^^snt plan which would "dramatically reduc[e] the imbalance"

inherent in even the modified plan and avoid the midyear

reassignments which the district court clearly foresaw as

a distinct possibility under its order (310a-311a).

Subsequently, when modification of the plan during the

course of the present school year was made necessary because

the projected enrollments at several schools failed to materia

-10-

lize, the court again reminded the parties that it would

have welcomed submission of a different plan by the defendants,

although it felt barred from considering a new plan at the

time because the matter had been appealed (333a). And in

approving the board's modifications, the district court said

that "[t]he problem that has developed was clearly foreseeable

back in June and July, and was in fact foreseen and discussed

at the earlier hearing" (341a).

Yet the district court somehow felt obligated to approve

a plan based upon defendants' alleged concepts of neighborhood

zoning and a 6-3-3 grade structure while recognizing that

even as modified in accordance with its order, the plan would

bring about "minimum" desegregation (310a):

Before even considering any other plan, it is

incumbent upon the Court to examine the pro

posal of the school board. if that plan [even

barely] meets constitutional requirements, the

Court should look no further. It is for the

school board, not the Court, to establish

educational policy. And it is not for the

Court to pick and choose among various plans

where each meets constitutional requirements (307a).

This passive attitude is startling, and we submit, led the

court into accepting a plan which its instincts correctly

told it would not work. There was ample authority to support

the district court's obligation to select a plan which did

away with the pattern of racially identifiable schools in West

Memphis, and which achieved more than "minimum" desegregation.

In Green v. County School Board of New Kent County. 391 u.S.

430, 439 (1968), the Supreme Court said:

-11-

The obligation of the district courts, as it

always has been, is to assess the effectiveness

of a proposed plan in achieving desegregation

... in light of the circumstances present and

the options available in each instance. it is

incumbent upon the school board to establish

that its proposed plan promises meaningful and

immediate progress toward disestablishing state-

imposed segregation. it is incumbent upon the

district court to weigh that claim in light of

the facts at hand and in light of any alternatives

whi_ch may be shown as feasible and more promising

in their effectiveness--- Of course, where other,

more promising courses of action are open to the

board, that may indicate a lack of good faith;

and at the least it places a heavy burden upon

the board to explain its preference for an

apparently less effective method.

Whatever doubts there may have been, whatever ambiguities may

have resided in the Green language, the directive of Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educ.. 402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971)

is clear; the court must select that plan among the alterna

tives presented to it which achieves the greatest amount of

desegregation. But the district court here deferred to the

defendants' expressed desire to maintain what it characterized

as a modified neighborhood school plan (309a). As the Supreme

Court has suggested, such deference is ill-placed when desegre

gation is not thereby maximized:

As we have held, "neighborhood school zoning,"

whether based strictly on home-to-school distance

or on "unified geographic zones" is not the only

constitutionally permissible remedy; nor is it

P^r se adequate to meet the remedial responsibili

ties of local boards. Having once found a viola

tion, the district judge or school authorities

should make every effort to achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation, taking

into account the practicalities of the situation.

A district court may and should consider the use

°f all available techniques including restructuring

°f attendance zones and both contiguous and non—

-12-

contiguous attendance zones. See Swann, supra,

at 22-31. The measure of any desegregation plan

is its effectiveness.

Davis v. Board of School Commr's of Mobile. 402 U.S. 33, 37

(1971). (emphasis supplied in part).

Furthermore, this is a school system in which there ought

to be a strong presumption against a "neighborhood school"

zoning plan which achieves anything less than maximum desegre

gation. School site location and school construction establish

school "neighborhoods" for the purposes of assignment of students.

In West Memphis, where a strict biracial school system was

enforced until the 1965-66 school year without exception,

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School District. 243 F. Supp.

65 (E.D. Ark. 1965), most of the schools presently operating

were constructed after 1954 in racially homogeneous "neighbor

hoods" and designed to serve students of the predominant

race residing in such "neighborhoods" (169a-175a). The Super

intendent admitted that white schools were planned and built

in white communities and black schools were planned and built

in black communities (176a). Under such circumstances, a

"neighborhood" plan is almost necessarily foredoomed to failure.

Cf. Davis v. School District of Pontiac. 309 F. Supp. 734

(E.D. Mich. 1970), aff'd 443 F.2d 573 (6th Cir.), cert, denied

___ U.S. ___ (1971) .

The prospects for success of any such plan are also dimmed

by the deliberate location of public housing projects designed

for predominant occupancy by one race adjacent to schools

serving students of that race (178a-181a). And the district's

-13-

claims for its "neighborhood school system" are vitiated by

its consistent disregard of "neighborhood zone lines" in the

past in order to achieve segregation. As recently as 1970-71,

white students outside the city limits who were living closer

to the Wedlock school than any other district facility were

transported at school district expense to white schools inside

West Memphis.

The solution adopted by the district court erroneously

attempts to maintain a "neighborhood school" system that never

was; it does not meet constitutional standards because it

sets up artificial ratios which result in racially identifiable

schools.

The October 27, 1971 attendance figures submitted by the

3/

defendants show that the three formerly black elementary schools.

Wonder, Jackson and Wedlock, have black enrollments signifi-

1/cantly greater than those of other schools in the system. On

1 / This Court may consider the actual effects of defendants'

modified plan, as implemented, in measuring its constitutional

sufficiency. See Davis v. Board of School Commr's of Mobile.

402 U.S. 33, 37 (1971). The lower court's opinion, in fact,

indicates that the court anticipated reconsidering this matter

if the plan as implemented did not achieve the expected desegre

gation (309a). However, the district court has now taken the

position (332a-333a) that it cannot change its order while the

case is on appeal. Plaintiffs, who were put to a Hobson's

choice of accepting what they considered to be an insufficient

order in the hope that the district court would change its

order in the fall, or appealing that insufficient order and

divesting the district court, in its view, of jurisdiction to

change its order, are thus enduring a non-unitary and unconsti

tutionally constituted school system because of litigation

delays— even though there is reason to suspect that the district

court may have concluded that the plan now in effect fails to

meet constitutional standards. Plaintiffs attempted to persuade

the district court of its power to act (see Appendix A) but as

yet to no avail.

4/ Under defendants' plan, Jackson Elementary was projected to

be majority-white (317a), but because the school district under-

-14-

the other hand, the formerly white Weaver and Richland elemen

tary schools enroll 62% and 61% white students, respectively.

The other formerly white schools are 49%, 53% and 57% white

(344a). we submit that this plan, and these results, do not

shake loose the racial identities which the defendants have

over the years affixed to the schools. Those schools which

remained all-black during operation under freedom of choice

will have a distinctively and consistently higher black

enrollment than other schools in the system. Similarly, many

of the traditionally white schools remain sharply distinguish

able because of their relatively lower black enrollments.

We intend no disagreement with this Court's statement in

Kemp v. Beasley, 423 F.2d 851, 857 (8th Cir. 1970) that "[w]e

certainly can conceive of a fully desegregated system where

percentages do vary from school to school and where even one

school might have a black majority and another a white majority

but still, when all factors are fairly and unemotionally

considered, the system is 'unitized' within the Supreme Court's

Alexander requirement." That is not this case, or this plan,

which deliberately sets out to achieve minimal desegregation

in a fashion which maintains the pattern of higher black enroll

ments at traditionally black schools and vice versa, and thus

preserves constitutionally invalid patterns of school assign

ment. See Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock. 426 F.2d 1035

(8th Cir. 1970).

4/ cont'd

estimated movement into one of the black housing projects

adjacent to the school (328a), it continues a heavily black school.

-15-

The question of remedy is more difficult. Obviously, at

the time of the hearing before the district court, the Stolee

plan promised to achieve greater desegregation and should

properly have been ordered implemented under the Swann standard.

However, Dr. Stolee's proposal was designed for immediate

implementation at little cost (271a) and it had the weakness

of leaving Wonder Elementary School only 35% white (253a).

Dr. Stolee himself expressed concern that Wonder, which would

be the only school with such a low proportion of white students

assigned to it, might not hold its enrollment (269a) but the

Superintendent (in defending the district's plan which would

have resulted in even smaller white minorities at Wedlock and

Wonder) predicted no white withdrawal at all (162a, 293a).

Inasmuch as the report filed by the school district shows a

considerable disinclination on the part of white students to

attend disproportionately black schools in West Memphis, it

could hardly be said at this juncture that even the Stolee

plan, without further modification, would bring about a com

pletely unitary school system.

Dr. Stolee recognized, for example, that a formerly

black school with nearly 50% white or black students assigned

to it would be more likely to remain stable (287a). And in

a school system as small as West Memphis, there is no warrant

for even a single school substantially disproportionate in

racial composition. While a total desegregation plan might

require acquisition of additional transportation facilities

-16-

(see 188a-196a), state aid would increase proportionately

(185a) and transportation within the city of West Memphis

would alleviate burdens presently caused by the operation of

the desegregation plan (273a). This Court has approved

plans which require the purchase of transportation capability,

Clark v.— Board of Educ. of Little Rock. No. 71-1409 (8th cir.,

September 10, 1971) (en banc), and there is no reason why

such a requirement ought not be imposed here. On remand,

the district court should be directed, therefore, to require

the submission and implementation, upon approval, of a plan

which completely desegregates the public schools of West Memphis

and eliminates their continuing racial identifiability root

and branch, through the use of whatever techniques are required

including the transportation of West Memphis city students

in order to achieve desegregation.

WHEREFORE, appellants respectfully pray that the judgment

be reversed and the cause remanded to the district court for

the submission and implementation of a constitutional plan to

achieve a fully unitary school system in the public schools

of the Hulbert-West Memphis School District.

CONCLUSION

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

-17-

J

GEORGE HOWARD, JR.

329*5 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas 71601

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 15th day of November, 1971,

I served two copies of the Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants in

this matter upon G. Ross Smith, Esq., 1100 Boyle Building,

Little Rock, Arkansas 72201, attorney for defendants, and John

I* Purtle, Esq., 300 Spring Building, Little Rock, Arkansas

72201, attorney for intervenors, via united States Mail, first

class, postage prepaid.

-18-

October 21, 1971

Hon. c;. Thomas Uisele

Unite' 1 states District Judqe

Pont O tfi.oe 3o:z 3604 "

Little Hock, Arkansas 72203

Dear Judge Eisele*

*C: No. J-65-C-3, Xirbroueh v. Huihorfc-ve-ttep7u» -chooi

to of p o n t i f f

"*»* ru.pph.t3 school n l ^ S ^ L ^ r ?.lnn fiiftd * « »

rodif 1 l'r< 1?3ithrvhr M s e ^ t o T h °?j? ^ lrna to *ho Plan as

the court is correct the t tho ri”^ 1*1 ? lnn* think b titutea a new plan h ^oc.if.ication hardly con-

chance to root the r.^tio r J ^ J * Cr "2 adrrini3trative court's order. reqi.arcrents set down in the

tire f v O r ^ c ^ x V t ^ ^ o ^ c c o ^ i d c r ^ appropril,t* approach to de5e^ r p t<on Jhlch entire plan and the

respect, vo vould r e - ^ t f u l W M 1 represents, m this

-pressed in this * * , ” * * * *cross appeal tcrc *■'... • • s. a. tho epocri and

rncadity or change in its entirftv Z ? t l 0 ? of thie court to

tlon in a school district if ♦•vie plna of ^Heeretjn-

plan is not working as cant, ~ « ? % C?Urt conclude» that the

tinuing oblication to^inaure^h thiS court*s con-

rights of the Nearo fc the constitutional

only to further orders‘ ^forced extends not

court's jurisdiction h»f !i y protective of the

stitute new nndftffective^lan^f^^fK the court to sub

working, even if theyare on^^rvf0? those vh*ch are not X t-.Choct^v Countv 5<ie IMited rtates

Cir. 1969T: Khi'I~ t ro t3̂ ftt1.rVl» 417 F.2d sTa (5th

for exmrple, isplerrentatio^ 2?W 0n?*r requiring, semester of the current- rj.~v.JLo ̂ fective with the second

proposed J ' ^ , , r r r' °f

»ppenl and oros3 ,.PPeilPvli1l,cK°haCer>S : r k rrlL r t ^ .

f if P C M o n C - A "

Hon. G. Thomas Eisele 2- October 21, 1971

,Voui d ^ nothing to prevent tin* p a rtie s fron *rcmiiicr

3 L E h ^ T » " I ^ H n ?* > * % • ' " r * « r

% p r * f 1f P - g| - - ' ^ a s ja | * f 39 p - 2 ° " i i 9?6iS ac i ; r ,T 5 ^ l 7 !Cl.^ u 25a i6r.m Oxr. 1971). '*

? af ure o f th i® case in p a rtic u la r suggest the

c h a S thoan inea3 ° e tha c o u r t ‘ s View th at i t ^ L y not

o f the S S e ? i " P f oe»tx y *n e f fe c t curing the pendency

raci illv 1 y’ f°r ««• *•»•* "■ -.<•*»<»«

•vste* h in ttu V m t h ^ p h ia s c .o a l

the nlan mi ayreoa at i.nc present tliun th *t

tne plan si.ixuu no longer ue continued in e f f e c t because

— s not working, taea the only effect: of waiting forI7i .... i . . .the appeal will be to fnvfcl»im4 4- -----_ _ «

• f

uni+ -»*•«» __------ u,:iJy realisation of a

in vioT->tion°o ,**VLs,:c:n in tha w*st Jwohia iiehooi district3S6 U l ? ^ r--Xr.J‘oi»^.Coianvy Hoard of fic.uc

the court L ' t ’- .Jt Vcuic ^ c ^ra^rooVraVeTol5

r * er ail,Ce * * * P^txes are di*~ eatinn -i ii:, Z ? paragraph 2 of defendants* *m>li-

29, 1971. y filed in fch;l<* c‘'«ao on or about September

For these reasons, we respectfully su'-'v— t th-*r *•’«« court vacate it:: crier c£ ju ... . » L « . . * Jne30 1^71 , ' * "■ — d *̂ t® on.or or ouly

t s n s i s : ™ ^ thB ™«

tion J L Cl°3Xnqf VH «-»»*•«* to bring to the court*o attoa-

!L_?_iACr̂ “g iron: ranainos v. board of>.̂...—l truetion of F illnbornnch r^*»*v r*A "Vv> V S W "

(M.D. Fla. , M-y 11, ' l^TTnrrSor----- l~ f 554

and^«^7?9re9at:i0n Pl9n Wil1 be successful addJ5 rf>3°vrC^ tion vhere « few whites are

rfna?«t?r>5OIT er4ly bK'ck scho° l8 vhich otherwise reraain intacti in a plan vhich anticipate*

retention of ioentifiably black schools will

t?7l* Partial desegregation results in white

flight, resort to private schools, and other

maneuvering* vhich frustrate the course of

justice. Successful desegregation must extend

throughout the school system and. be done in

Hon. G. Thoras risele -3 October 21/ 1971

such n v,-!y tint the. tactics which impede court orders rendered futile."

Very truly your3.

I

Horvnn J. Chschkin Attorney for Plaintiffs

HJCinu

CC G. Ross Smith, Ei-q.

Johsi P u r tie , Eaq.

George Howard, £*<7.