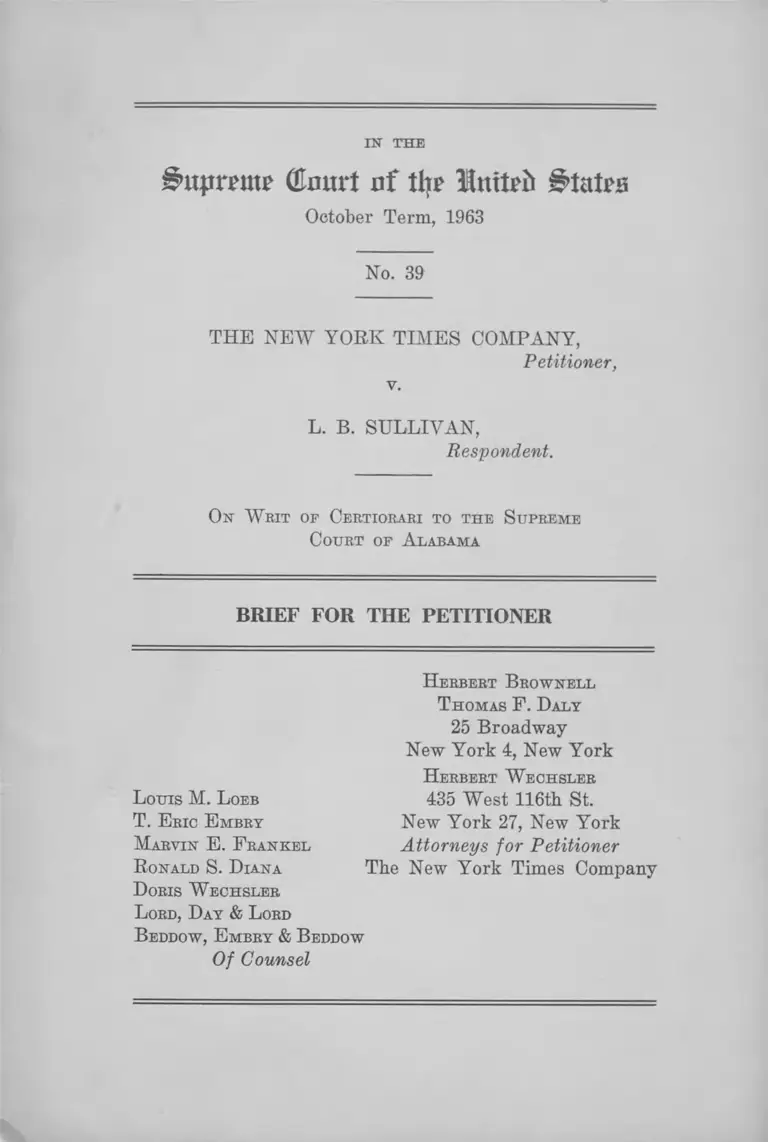

The New York Times Company v. Sullivan Brief for the Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The New York Times Company v. Sullivan Brief for the Petitioner, 1963. ec23f982-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/123b5e47-6415-4892-9d25-bbcae212eca7/the-new-york-times-company-v-sullivan-brief-for-the-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

ĵ upremp Court of ttjr Inttefc States

October Term, 1963

No. 39

THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY,

Petitioner,

v.

L. B. SULLIVAN,

Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the Supreme

Court of A labama

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

H erbert B rownell

T homas F . Daly

25 Broadway

New York 4, New York

Louis M. L oeb

T. E ric E mbry

Marvin E . F rankel

R onald S. D iana

D oris W echsler

L ord, Day & L ord

B eddow, E mbry & B eddow

Of Counsel

H erbert W echsler

435 West 116th St.

New York 27, New York

Attorneys for Petitioner

The New York Times Company

INDEX

PAGE

Opinions B e l o w --------------------------------------------------------------- 1

JuBISDICTION______________________________________________ 1

Questions Pkesented-------------------------------------------------------- 2

Stat e m e n t________________________________________________ 3

1. The Nature of the Publication------------------------------ 4

2. The Allegedly Defamatory Statements----------------- 6

3. The Impact of the Statements on Respondent’s

Reputation____________________________________ 10

4. The Circumstances of the Publication----------------- 15

5. The Response to the Demand for a Retraction — 18

6. The Rulings on the M erits-------------------------------- 22

7. The Jurisdiction of the Alabama Courts------------ 25

Summary op A rgument--------------------------------------------------- 28

A rgument

I The decision rests upon a rule of liability for

criticism of official conduct that abridges freedom

of the p re ss___________________________________ 38

First: The State Court’s Misconception of the

Constitutional Issues________________________ 39

Second: Seditious Libel and the Constitution — 41

Third: The Absence of Accommodation of Con

flicting Interests------------------------------------------- 51

Fourth: The Relevancy of the Official’s Privilege 55

Fifth: The Protection of Editorial Advertise

ments -------------------------- 57

II Even if the rule of liability were valid on its face

the judgment rests on an invalid application------- 58

n

First: The Scope of Review ___________________ 59

Second: The Failure to Establish Injury or

Threat to Respondent’s Reputation__________ 60

Third: The Magnitude of the Verdict__________ 66

III The assumption of jurisdiction in this action by

the Courts of Alabama contravenes the Constitu

tion ___________________________________________ 69

First: The Finding of a General Appearance_70

Second: The Territorial Limits of Due Process 77

Third: The Burden on Commerce_____________ 86

Fourth: The Freedom of the P ress____________ 88

Conclusion ________________________________________ 90

A ppendix A _____________________________________________ 91

A ppendix B _____________________________________________ 97

PAGE

Citations

Cases:

A. & G. Stevedores v. Ellerman Lines, 369 U. S. 355 69

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616------------------- 48

Aetna Insurance Co. v. Earnest, 215 Ala. 557 ----------- 74

Affolder v. New York, Chicago & St. L. R. Co.,

339 U. S. 96_____________________________________ 69

Age-Herald Publishing Co. v. Huddleston, 207 Ala. 40 83

Alabama Ride Company v. Vance, 235 Ala. 263 ------ 39

Alberts v. California, 354 U. S. 476------- ------------------- 48

Associated Press v. United States, 326 U. S. 1 --------- 58

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Ry. v. Wells, 265 U. S.

101 _____________________________________________ 87

Baldwin v. G. A. F. Seelig, Inc., 294 U. S. 511______ 87

PAGE

Bantam Boohs, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U. S. 5 8 ____49, 57, 69

Barr v. Matteo, 360 U. S. 564 ____________________55, 56

Barrows v. Jachson, 346 U. S. 249________________ 40, 58

Barry v. McCollom, 81 Conn. 293 ____________ 55n.

Bates v. Little Roch, 361 U. S. 516_______________ 50, 68

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250 ______29, 40, 41, 48

Blankenship v. Blankenship, 263 Ala. 297 __________ 73

Blount v. Peerless Chemicals (P. R.) Inc., 316 F. 2d

695 ____________________________________________ 78

Boucher v. Clark Pub. Co., 14 S. D. 7 2 _____________ 54n.

Boyd v. Warren Paint & Color Co., 254 Ala. 687 ____ 73

Bradford v. Clark, 90 Me. 298 ______________________ 54n.

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 _______________ 57

Brewster v. Boston Herald-Traveler Corp., 141 F.

Supp. 760 ______________________________________ 80

Bridges v. California, 314 U. S. 252 ___________ 30, 42, 43,

44, 48, 59

Buckley v. Neiv York Times Co., 215 F. Supp. 893 _79

Calagaz v. Calhoon, 309 F. 2d 248 _________________ 81

Canadian Pacific Ry. Co. v. Sullivan, 126 F. 2d 433,

cert, denied, 316 U. S. 696 _______________________ _ 76

Cannon v. Time, Inc., 115 F. 2d 423 ------------------------ 79

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ______29, 42, 43, 67

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 TJ. S. 238____________ 40

Catron v. Jasper, 303 Ky. 598 -------------------- :-----------55n.

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 _______ 40

Charles Parker Co. v. Silver City Crystal Co., 142

Conn. 605 ______________________________________ 54n.

Chicago & N. W. Ry. v. Nye Schneider Fowler Co.,

260 U. S. 3 5 ____________ _______________________ 68

Chicago, B. & Q. Railroad v. Chicago, 166 TJ. S. 226 69

iv

PAGE

City of Albany v. Meyer, 99 Cal. App. 651---------------- 50

City of Chicago v. Tribune Co., 307 HI. 595 -----------50, 56

Coleman v. MacLennan, 78 Kan. 711---------------------- 54n.

Communications Assn. v. Douds, 339 U. S. 382 ------- 51

Constantine v. Constantine, 261 Ala. 4 0 ----------------- 74

Craig v. Harney, 331 U. S. 367 -----------------------------44, 59

Crowell-Coilier Pub. Co. v. Caldwell, 170 F. 2d 941 — 67

Dagnello v. Long Island Rail Road Company, 289 F.

2d 797 _________________________________________ 69

Dailey Motor Co. v. Reaves, 184 N. C. 260 ---------------- 74

Davis v. Farmers Co-operative Co., 262 U. S. 312 —35, 76,

87, 88

Davis v. O’Hara, 266 U. S. 314-----------------------------74, 75

Davis v. Wechsler, 263 U. S'. 2 2 ------------------------------ 75

Dean Milk Co. v. City of Madison, 340 U. S. 349 — 52, 87

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 --------------------------- 42

Dennis v. United States, 341 U. S. 494 --------------48, 51, 54

Denver & R. G. W. R. Co. v. Terte, 284 U. S. 284

35, 76, 87

Dimick v. Schiedt, 293 U. S. 474 ----------------------------- 69

Dozier Lumber Co. v. Smitli-Isburg Lumber Co., 145

Ala. 317 _______________________________________ 72

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160---------------------- 87

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 — 29, 42, 48, 59

Erlanger Mills v. Cohoes Fibre Mills, Inc., 239 F.

2d 502 ________________________________________ 80, 88

Ex parte Cullinan, 224 Ala. 263 ---------------------- 34, 71, 72

Ex parte Haisten, 227 Ala. 183-----------------------------71, 74

Ex parte Spence, 271 Ala. 151-------------------------------- 76n.

Ex parte Textile Workers Union of America, 249

Ala. 1 3 6 _____________________________________ 72, 76n.

V

PAGE

Ex parte Union Planters National Bank and Trust

Co., 249 Ala. 461_______________________________ 76n.

Fairmount Glass Works v. Cub Fork Coal Co., 287

U. S. 474 _______________________________________ 69

Farmers Union v. WDAY, 360 U. S. 525 __________ 56

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391________________________ 76n.

Ferdon v. Dickens, 161 Ala. 181___________________ 39

Fisher’s Blend Station v. Tax Commission, 297 U. S.

650 _____________________________________________ 87

Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U. S. 380 ____________________59, 62

Ford Motor Co. v. Hall Auto Co., 226 Ala. 385 _____76n.

Fowler v. Curtis Publishing Co., 182 F. 2d 377 ____60n.

Friedell v. Blakeley Printing Co., 163 Minn. 226 ___54n.

Gayle v. Magazine Management Co., 153 F. Supp. 861 80

General Trading Co. v. State Tax Comm’n., 322 U. S.

335 ____________________________________________ 85

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Comm., 372 U. S. 539_52, 89

Gough v. Tribune-Journal Company, 75 Ida. 502____54n.

Gregoire v. Biddle, 177 F. 2d 579 __________________ 55

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233 ------- 67

H. P. Hood & Sons v. DuMond, 336 U. S. 525 ______ 87

Hanson v. Denckla, 357 U. S. 235 _________ 35, 37, 77, 78,

80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85

Harrub v. Hy-Trous Corporation, 249 Ala. 414______ 72

Hartmann v. Time, Inc., 166 F. 2d 127, cert, denied,

334 U. S. 838 ___________________________________ 80n.

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 IT. S. 242 ___________________ 59

Hope v. Hearst Consolidated Publications, Inc., 294

F. 2d 681_______________________________________ 61

Howland v. Flood, 160 Mass. 509___________________55n.

Hughes v. Bizzell, 189 Okla. 472 ____________________55n.

VI

Hutchinson v. Chase & Gilbert, 45 F. 2d 139________ 82

Insult v. New York, World-Telegram Corp., 273 F. 2d

166, cert, denied, 362 U. S. 942 -----------------------------80n.

International Milling Co. v. Columbia Transportation

Co., 292 U. S. 511________________________________ 87

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U. S. 310

35, 36, 77, 78, 79, 82, 88

Johnson Publishing Co. v. Davis, 271 Ala. 474 -----------39,

62n., 67, 72

Julian v. American Business Consultants, Inc., 2 N. Y.

2d 1 ____________________________________________ 60n.

Kilpatrick v. Texas & P. By. Co., 166 F. 2d 788 — 81n., 86

Kingsley Pictures Corp. v. Regents, 360 IT. S. 684_51, 59

Kirkpatrick v. Journal Publishing Company, 210

Ala. 1 0 _________________________________________ 39

Konigsberg v. State Bar of California, 366 U. S.

36 _____________________________________________40,52

Kyser v. American Surety Co., 213 Ala. 614------------ 74

L. D. Reeder Contractors of Ariz. v. Higgins Indus

tries, Inc., 265 F. 2d 768 ________________________ 78, 80

Lampley v. Beavers, 25 Ala. 534 ------------------------71, 76n.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 --------------------------------- 50

Lawrence v. Fox, 357 Mich. 134 ------------------------------- 54n.

Life & Casualty Co. v. McCray, 291 U. S. 566 --------- 68

Tjouisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. N. A. A. C. P., 366

U. S'. 293 _______________________________________ 50

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 IT. S. 444 ------------------------------ 58, 84

Mattox v. News Syndicate Co., 176 F. 2d 897, cert,

denied, 338 U. S. 858 ____________________________ 80n.

McBride v. Crowell-Coilier Pub. Co., 196 F. 2d 187 — 60n.

McGee v. International Life Ins. Co., 355 U. S. 220

36, 37, 84

PAGE

Vll

PAGE

McKnett v. St. Louis <& San Francisco Ry., 292 U. S.

230 _____________________________________________ 73n.

Michigan Central R. R. Co. v. Mix, 278 U. S. 492 _35, 76,

87

Miller Bros. Co. v. Maryland, 347 U. S. 340 ________ 85

Mills v. Denny, 245 Iowa 584 _______________________55n.

Minnesota v. Barber, 136 U. S. 313________________ 87

Missouri Pacific Ry. Co. v. Tucker, 230 U. S. 340 ____ 68

Montgomery v. Philadelphia, 392 Pa. 178___________55n.

Moore v. Davis, 16 S. W. 2d 380 ___________________54n.

N. A. A. C. P. v. Alabama, 357 U. S. 449 __40, 67, 69, 70, 75

N. A. A. C. P. v. Button, 371 U. S. 415______29, 41, 42, 43,

48, 57, 65, 89

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U. S. 697 ___________________ 40

Neiman-Marcus v. Lait, 13 F.R.D. 311_____________ 60n.

Neiv York Times v. Parks and Patterson, No. 687,

October Term, 1962, No. 52, this T erm __________ 3n.

New York Times Company v. Conner, 291 F. 2d

492 _________________________________________ 73n.,92

Noral v. Hearst Publications, Inc., 40 Cal. App. 2d

348 _____________________________________________ 60n.

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 _____________ 32, 59, 62

O’Hara v. Davis, 109 Neb. 615_____________________ 75

Olcese v. Justice’s Court, 156 Cal. 8 2 ______________ 74

Overstreet v. Canadian Pacific Airlines, 152 F. Supp.

838 ____________________________________________ 88

Pantsivowe Zaklady Graviozne v. Automobile Ins.

Co., 36 F. 2d 504 ________________________________ 77

Parks and Patterson v. New York Times Company,

195 F. Supp. 919, rev’d, 308 F. 2d 474___________ 3n.

Parsons v. Age-Herald Pub. Co., 181 Ala. 439 ______ 39

Partin v. Michaels Art Bronze Co., 202 F. 2d 541____ 78

Vlll

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U. S. 331 --------------30, 40,44,

59, 60, 65

Perkins v. Benguet Mining Co., 342 U. S. 437 ---------35, 78

Peterson v. Steenerson, 113 Minn. 87 ---------------------- 55n.

Phoenix Newspapers v. Choisser, 82 Ariz. 271 ------- 54n.

Polizzi v. Cowles Magazines, Inc., 345 U. S. 663 ------ 85

Ponder v. Cobb, 257 N. C. 281_____________________54n.

Putnam v. Triangle Publications, Inc., 245 N. C. 432 79

Rearick v. Pennsylvania, 203 U. S. 507 ------------------- 82

Roberts v. Superior Court, 30 Cal. App. 714----------- 74

Robinson v. California, 370 U. S. 660 ---------------------- 68

Roth v. United States, 354 U. S. 476 --------------- 29, 40, 42

St. Louis, I. Mt. & So. Ry. Co. v. Williams, 251

U. S. 6 3 _______________________________________ 68

St. Mary’s Oil Engine Co. v. Jackson Ice and Fuel

Co., 224 Ala. 152______________________________ 72, 73

Salinger v. Cowles, 195 Iowa 873 --------------------------- 54n.

Sclienck v. United States, 249 U. S. 4 7 ------------------- 51

Schlinkert v. Henderson, 331 Mich. 284 -------------------55n.

Schmidt v. Esquire, Inc., 210 F. 2d 908, cert, denied,

348 U. S. 819___________________________________ 79

Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147----------------------------- 58

Scripto v. Carson, 362 U. S. 207 --------------------------- 37, 84

Seaboard Air Line Ry. v. Hubbard, 142 Ala. 546 ------ 72

Service Parking Corp. v. Washington Times Co.,

92 F. 2d 502 _________________________________60n., 61

Sessoms Grocery Co. v. International Sugar Feed

Company, 188 Ala. 232 -------------------------------------- 71

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ----------------------------- 40

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U. S. 479 ---------------------- 52, 68, 89

Sioux Remedy Co. v. Cope, 235 U. S. 197---------------- 88

PAGE

PAGE

Smith v. California, 361 U. S. 147__________ 54, 57, 67,

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761______

Southern Pac. Co. v. Guthrie, 186 F. 2d 926_________

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U. S. 513________43, 52, 54, 67,

Staub v. City of Baxley, 355 U. S. 313______________

Street d Smith Publications, Inc. v. Spikes, 120 F. 2d

895, cert, denied, 314 U. S. 653 ___________________

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ____________ 42,

Sweeney v. Patterson, 128 F. 2d 457 _______________

Sweeney v. Schenectady Union Pub. Co., 122 F. 2d

288, aff’d, 316 U. S. 642 ________________________

Talley v. California, 362 U. S. 6 0 ______________ 58, 84,

Terminal Oil Mill Co. v. Planters W. & G. Co., 197

Ala. 429 ________________________________________

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U. S. 1 ________________

Thompson v. Wilson, 224 Ala. 299 __________________

Times Film Corporation v. City of Chicago, 365 U. S.

43 _____________________________________________

Travelers Health Assn. v. Virginia, 339 U. S. 643 _37,

Trippe Manufacturing Co. v. Spencer Gifts, Inc., 270

F. 2d 821 _______________________________________

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U. S. 8 6 _______________________

United States v. Associated Press, 52 F. Supp. 362

42,

United States v. Classic, 313 U. S. 299 ____________

United States v. Smith, 173 Fed. 227 ______________

Valentine v. Christensen, 316 U. S. 52______________

Vaughan v. Vaughan, 267 Ala. 117_________________

Ward v. Love County, 253 U. S. 1 7 _________________

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S'. 4 9 _____________________

89

88

69

89

75

79

66

52

53

89

71

42

74

40

84

80

41

43

41

82

57

74

76

59

X

Weston v. Commercial Advertiser Assn., 184 N. Y.

PAGE

479 _____________________________________________ 60n.

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U. S. 183---------------------- 54

Whitaker v. Macfadden Publications, Inc., 105 F. 2d

44 _____________________________________________ 79

Whitney v. California, 274 TJ. S. 357 ________ 31, 33, 56, 67

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 _______________ 68

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S. 375 _______________ 30, 44, 59

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U. S. 284 ___________________ 75

WSAZ, Inc. v. Lyons, 254 F. 2d 242 ---------------------- 85

Zuber v. Pennsylvania R. Co., 82 F. Supp. 670 ______ 76

Zuck v. Interstate Publishing Corp., 317 F. 2d 727 _83

Constitution and Statutes

United States Constitution:

Commerce C lause_________________________ 2, 25, 34, 37,

38, 76, 86

Full Faith aud Credit Clause________________ 37, 40, 86

First Amendment___________________2, 24, 29, 31, 38, 41,

42, 44, 51, 52, 54, 57, 58, 59, 62,

65, 66, 68, 69, 83, 84, 88, 89, 90

Seventh Amendment--------------------------------------------- 69

Fourteenth Amendment____________________2, 24, 25, 29,

34, 38, 39, 42, 77

28 U.S.C. 1257 ( 3 ) ________________________________ 1

Act of July 14, 1798, Secs. 2, 3; 1 Stat. 596 ________ 46, 49

Act of July 4, 1840, c. 45, 6 Stat. 802 ______________ 47

Acts of June 17, 1844, cc. 136 and 165, 6 Stat. 924

and 931 ________________________________________ 47

XI

Alabama Statutes:

Alabama Code of 1940, Title 7 § 188 ------------------- 25, 73

Alabama Code of 1940, Title 7 § 1 9 9 (1 )-------------- 25,73

Alabama Code of 1940, Title 13 § 126____________ 75

Alabama Code of 1907, Title 7 § 9 7 --------------------- 73

PAGE

Foreign Statutes:

Defamation Act, 1952, 15 & 16 Geo. 6 & 1 Eliz. 2,

ch. 66, § 5 ______________________________________ 62n.

Miscellaneous:

Chafee, Free Speech in the United States (1941) — 48

Cooley, Constitutional Limitations (8th ed. 1927) — 48

4 Elliot’s Debates (1876)__________________42, 45, 47, 56

1 Harper and James, The Law of Torts (1956) 54n., 55n.

3 Jones, Alabama Practice and Forms (1947) (Supp.

1962) __________________________________________ 72

Levy, Legacy of Suppression (1960)---------------------- 46

6 Moore’s Federal Practice (2d ed. 1953)__________ 69

Prosser on Torts (2d ed. 1955)---------------------- 55n., 60n.

Smith, Freedom’s Fetters (1956)__________________ 46

1 Williston on Contracts (3d ed. 1957)____________ 81

25A.L.R. 2 d ______________________________________ 74

4 Annals of Congress_____________________________ 56

8 Annals of Congress____________________________ 46-47

Government by Injunction, 15 Nat. Corp. Rep. (1898) 51

H.R. Rep. No. 86, 26th Cong., 1st Sess. (1840)_____47n.

Report of the Committee on the Law of Defamation

(1948) cmd. 7536 _______________________________ 62n.

Report with Senate hill No. 122, 24th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1836) _________________________________________ 48

Restatement, T o r ts__________________________ 55n., 60n.

Kalven, The Law of Defamation and the First

Amendment in Conference on the Arts, Publish

ing and the Law (U. of Chi. Law S ch ool)_______ 44n.

Leflar, The Single Publication Rule, 25 Rocky Mt. L.

Rev. (1953) _____________________________________80n.

Noel, Defamation of Public Officers and Candidates,

49 Col. L. Rev. (1949)__________________________ 54n.

Prosser, Interstate Publication, 51 Mich. L. Rev.

(1953) __________________________________________ 80n.

Developments in the Law: Defamation, 69 Harv. L.

Rev. (1956) _____________________________________54n.

Note, 29 U. of Chi. L. Rev., 569 (1962)_____________ 80n.

42 Harv. L. Rev., 1062 (1929)_____________________ 77

43 Harv. L. Rev., 1156 (1930)_____________________ 77

X ll

PAGE

IK THE

(Enurt of tht Mniteb States

October Term, 1963

No. 39

THE NEW YORK TIMES COMPANY,

Petitioner,

v.

L. B. SULLIVAN,

Respondent.

O n W rit of Certiorari to the S upreme

Court of A labama

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONER

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 1139)

is reported in 273 Ala. 656, 144 So. 2d 25. The opinion of

the Circuit Court, Montgomery County, on the petitioner’s

motion to quash service of process (R. 49) is unreported.

There was no other opinion by the Circuit Court.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama (R.

1180) was entered August 30,1962. The petition for a writ

of certiorari was filed November 21, 1962 and was granted

January 7, 1963. 371 U. S. 946. The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. 1257 (3).

2

Questions Presented

1. Whether, consistently with the guarantee of freedom

of the press in the First Amendment as embodied in the

Fourteenth, a State may hold libelous per se and actionable

by an elected City Commissioner published statements crit

ical of the conduct of a department of the City Government

under his general supervision, which are inaccurate in some

particulars.

2. Whether there was sufficient evidence to justify,

consistently with the constitutional guarantee of freedom

of the press, the determination that published statements

naming no individual but critical of the conduct of the

“ police” were defamatory as to the respondent, the elected

City Commissioner with jurisdiction over the Police De

partment, and punishable as libelous per se.

3. Whether an award of $500,000 as “ presumed” and

punitive damages for libel constituted, in the circumstances

of this case, an abridgment of the freedom of the press.

4. Whether the assumption of jurisdiction in a libel

action against a foreign corporation publishing a newspaper

in another State, based upon sporadic news gathering ac

tivities by correspondents, occasional solicitation of adver

tising and minuscule distribution of the newspaper within

the forum state, transcended the territorial limitations of

due process, imposed a forbidden burden on interstate com

merce or abridged the freedom of the press.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

The constitutional and statutory provisions involved are

set forth in Appendix A, infra, pp. 91-95.

3

Statement

On April 19, 1960, the respondent, one of three elected

Commissioners of the City of Montgomery, Alabama, in

stituted this action in the Circuit Court of Montgomery

County against The New York Times, a New York corpo

ration, and four co-defendants resident in Alabama, Ralph

D. Abernathy, Fred L. Shuttlesworth, S. S. Seay, Sr., and

J. E. Lowery. The complaint (R. 1) demanded $500,000 as

damages for libel allegedly contained in two paragraphs

of an advertisement (R. 6) published in The New York

Times on March 29,1960. Service of process was attempted

by delivery to an alleged agent of The Times in Alabama

and by substituted service (R. 11) pursuant to the “ long-

arm” statute of the State. A motion to quash, asserting

constitutional objections to the jurisdiction of the Circuit

Court (R. 39, 43-44, 47, 129) was denied on August 5, 1960

(R. 49). A demurrer to the complaint (R. 58, 67) was over

ruled on November 1, 1960 (R. 108) and the cause proceeded

to a trial by jury, resulting on November 3 in a verdict

against all defendants for the full $500,000 claimed (R. 862).

A motion for new trial (R. 896, 969) was denied on March

17,1961 (R. 970). The Supreme Court of Alabama affirmed

the judgment on August 30, 1962 (R. 1180).* The Circuit

* Libel actions based on the publication of the same statements in

the same advertisement were also instituted by Governor Patterson

of Alabama, Mayor James of Montgomery, City Commissioner Parks

and former Commissioner Sellers. The James case is pending on

motion for new trial after a verdict of $500,000. The Patterson,

Parks and Sellers cases, in which the damages demanded total

$2,000,000, were removed by petitioner to the District Court. That

court sustained the removal (195 F. Supp. 919 [1961]) but the

Court of Appeals, one judge dissenting, reversed and ordered a re

mand (308 F. 2d 474 [1962]). A petition to review that decision on

certiorari is now pending in this Court. New York Times Company

v. Parks and Patterson, No. 687, October Term, 1962, No. 52, this

Term.

4

Court and the Supreme Court both rejected the petition

er’s contention that the liability imposed abridged the free

dom of the press.

1. The Nature of the Publication.— The advertisement,

a copy of which was attached to the complaint (R. 1, 6), con

sisted of a full page statement (reproduced in Appendix

B, infra p. 97) entitled “ Heed Their Rising Voices” , a

phrase taken from a New York Times editorial of March

19, 1960, which was quoted at the top of the page as fol

lows: “ The growing movement of peaceful mass demon

strations by Negroes is something new in the South, some

thing understandable . . . Let Congress heed their rising

voices, for they will be heard.”

The statement consisted of an appeal for contributions

to the “ Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the

Struggle for Freedom in the South” to support “ three

needs—the defense of Martin Luther King—the support of

the embattled students— and the struggle for the right-to-

vote ’ ’. It was set forth over the names of sixty-four individ

uals, including many who are well known for achievement

in religion, humanitarian work, public affairs, trade unions

and the arts. Under a line reading “ We in the South who

are struggling daily for dignity and freedom warmly en

dorse this appeal” appeared the names of twenty other

persons, eighteen of whom are identified as clergymen in

various southern cities. A New York address and telephone

number were given for the Committee, the officers of

which were also listed, including three individuals whose

names did not otherwise appear.

The first paragraph of the statement alluded generally

to the “ non-violent demonstrations” of Southern Negro

5

students “ in positive affirmation of the right to live in

human dignity as guaranteed by the TT.S. Constitution and

the Bill of Bights.” It went on to charge that in “ their

efforts to uphold these guarantees, they are being met by

an unprecedented wave of terror by those who would deny

and negate that document which the whole world looks

upon as setting the pattern for modern freedom . . .

The second paragraph told of a student effort in

Orangeburg, South Carolina, to obtain service at lunch

counters in the business district and asserted that the

students were forcibly ejected, tear-gassed, arrested en

masse and otherwise mistreated.

The third paragraph spoke of Montgomery, Alabama

and complained of the treatment of students who sang on

the steps of the State Capitol, charging that their leaders

were expelled from school, that truckloads of armed police

ringed the Alabama State College Campus and that the

College dining-hall was padlocked in an effort to starve

the protesting students into submission.

The fourth paragraph referred to “ Tallahassee, At

lanta, Nashville, Savannah, Greensboro, Memphis, Rich

mond, Charlotte and a host of other cities in the South,”

praising the action of “ young American teenagers, in face

of the entire weight of official state apparatus and police

power,” as “ protagonists of democracy.”

The fifth paragraph speculated that “ The Southern

violators of the Constitution fear this new, non-violent

brand of freedom fighter . . . even as they fear the

upswelling right-to-vote movement,” that “ they are deter

mined to destroy the one man who more than any other,

symbolizes the new spirit now sweeping the South—the

6

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., world-famous leader of

the Montgomery Bus Protest.” It went on to portray the

leadership role of Dr. King and the Southern Christian

Leadership Conference, which he founded, and to extol the

inspiration of “ his doctrine of non-violence” .

The sixth paragraph asserted that the “ Southern vio

lators” have repeatedly “ answered Dr. K ing’s protests

with intimidation and violence” and referred to the bomb

ing of his home, assault upon his person, seven arrests

and a then pending charge of perjury. It stated that

“ their real purpose is to remove him physically as the

leader to whom the students and millions of others—look

for guidance and support, and thereby to intimidate all

leaders who may rise in the South” , concluding that the

defense of Dr. King “ is an integral part of the total strug

gle for freedom in the South.”

The remaining four paragraphs called upon “ men and

women of good will” to do more than “ applaud the creative

daring of the students and the quiet heroism of Dr. King”

by adding their “ moral support” and “ the material help

so urgently needed by those who are taking the risks, facing-

jail and even death in a glorious re-affirmation of our Con

stitution and its Bill of Rights” .

2. The Allegedly Defamatory Statements.— Of the ten

paragraphs of text in the advertisement, the third and a

portion of the sixth were the basis of respondent’s claim

of libel.

(a) The third paragraph was as follows:

“ In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang

‘ My Country, ’Tis of Thee’ on the State Capitol steps,

their leaders were expelled from school, and truck

7

loads of police armed with shot-guns and tear-gas

ringed the Alabama State College Campus. When the

entire student body protested to state authorities by

refusing to re-register, their dining hall was padlocked

in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

Though the only part of this statement that respondent

thought implied a reference to him was the assertion about

“ truckloads of police” (R. 712), he undertook and was per

mitted to deal with the paragraph in general by adducing

evidence depicting the entire episode involved. His evidence

consisted mainly of a story by Claude Sitton, the southern

correspondent of The Times, published on March 2, 1960

(R. 655, 656-7, PL Ex. 169, R. 1568), a report requested

by The Times from Don McKee, its “ stringer” in Mont

gomery, after institution of this suit was threatened (R.

590-593, PI. Ex. 348, R. 1931-1935), and a later telephoned

report from Sitton to counsel for The Times, made on

May 5, after suit was brought (R. 593-595, PL Ex. 348, R.

1935-1937).

This evidence showed that a succession of student

demonstrations had occurred in Montgomery, beginning

with an unsuccessful effort by some thirty Alabama State

College students to obtain service at a lunch counter in

the Montgomery County Court House. A thousand students

had marched on March 1, 1960, from the College campus

to the State Capitol, upon the steps of which they said

the Lord’s Prayer and sang the National Anthem before

marching back to the campus. Nine student leaders of the

lunch counter demonstration were expelled on March 2

by the State Board of Education, upon motion of Governor

Patterson, and thirty-one others were placed on probation

(R. 696-699, Pl. Ex. 364, R. 1972-1974), but the singing

8

at the Capitol was not the basis of the disciplinary action

or mentioned at the meeting of the Board (R. 701). Ala

bama State College students stayed away from classes

on March 7 in a strike in sympathy with those expelled

hut virtually all of them returned to class after a day and

most of them re-registered or had already done so. On

March 8, there was another student demonstration at a

church near the campus, followed by a march upon the

campus, with students dancing around in conga lines and

some becoming rowdy. The superintendent of grounds

summoned the police and the students left the campus, but

the police arrived as the demonstrators marched across

the street and arrested thirty-two of them for disorderly

conduct or failure to obey officers, charges on which they

later pleaded guilty and were fined in varying amounts

(R. 677-680, 681, 682).

A majority of the student body was probably involved

at one time or another in the protest but not the “ entire

student body” . The police did not at any time “ ring”

the campus, although they were deployed near the campus

on three occasions in large numbers. The campus dining

hall was never “ padlocked” and the only students who

may have been barred from eating were those relatively

few who had neither signed a pre-registration application

nor requested temporary meal tickets (R. 594, 591).

The paragraph was thus inaccurate in that it exagger

ated the number of students involved in the protest and

the extent of police activity and intervention. If, as the

respondent argued (R. 743), it implied that the students

were expelled for singing on the steps of the Capitol, this

was erroneous; the expulsion was for the demand for

service at a lunch counter in the Courthouse. There was,

9

moreover, no foundation for the charge that the dining hall

was padlocked in an effort to starve the students into sub

mission, an allegation that especially aroused resentment in

Montgomery (R. 605, 607, 949, 2001, 2002, 2007).

(b) The portion of the sixth paragraph of the state

ment relied on by respondent read as follows:

“ Again and again the Southern violators have

answered Dr. K ing’s peaceful protests with intimi

dation and violence. They have bombed his home,

almost killing his wife and child. They have assaulted

his person. They have arrested him seven times—for

‘ speeding’, ‘ loitering’ and similar ‘ offenses’. And

now they have charged him with ‘ perjury’— a felony

under which they could imprison him for ten years.”

As to this paragraph, which did not identify the time

or place of the events recited, but which respondent read to

allude to himself because it also “ describes police action”

(R. 724), his evidence showed that Dr. K ing’s home had in

fact been bombed twice when his wife and child were at

home, though one of the bombs failed to explode—both of

the occasions antedating the respondent’s tenure as Com

missioner (R. 594, 685, 688); that Dr. King had been ar

rested only four times, not seven, three of the arrests pre

ceding the respondent’s service as Commissioner (R. 592,

594-595, 703); that Dr. King had in fact been indicted for

perjury on two counts, each carrying a possible sentence of

five years imprisonment (R. 595), a charge on which he sub

sequently was acquitted (R. 680). It also showed that

while Dr. King claimed to have been assaulted when he

was arrested some four years earlier for loitering outside

a courtroom (R. 594), one of the officers participating in

arresting him and carrying him to a detention cell at

1 0

headquarters denied that there was a physical assault (R.

692-693)— this incident also antedating the respondent’s

tenure as Commissioner (R. 694).

On the theory that the statement could be read to charge

that the bombing of Dr. K ing’s home was the work of the

police (R. 707), respondent was permitted to call evidence

that the police were not involved; that they in fact dis

mantled the bomb that did not explode; and that they did

everything they could to apprehend the perpetrators of

the bombings (R. 685-687)—also before respondent’s

tenure as Commissioner (R. 688). In the same vein,

respondent testified himself that the police had not bombed

the King home or assaulted Dr. King or condoned the

bombing or assaulting; and that he had had nothing to

do with procuring K ing’s indictment (R. 707-709).

3. The Impact of the Statements on Respondent’s Rep

utation.—As one of the three Commissioners of the City of

Montgomery since October 5, 1959, specifically Commis

sioner of Public Affairs, respondent’s duties were the

supervision of the Police Department, Fire Department,

Department of Cemetery and Department of Scales (R.

703). He was normally not responsible, however, for day-

to-day police operations, including those during the Ala

bama State College episode referred to in the advertise

ment, these being under the immediate supervision of

Montgomery’s Chief of Police—though there was one

occasion when the Chief was absent and respondent super

vised directly (R. 720). It was stipulated that there were

175 full time policemen in the Montgomery Police Depart

ment, divided into three shifts and four divisions, and

24 “ special traffic directors” for control of traffic at the

schools (R. 787).

11

As stated in respondent’s testimony, the basis for his

role as aggrieved plaintiff was the “ feeling” that the ad

vertisement, which did not mention him or the Commission

or Commissioners or any individual, “ reflects not only on

me but on the other Commissioners and the community”

(R. 724). He felt particularly that statements referring to

“ police activities” or “ police action” were associated with

himself, impugning his “ ability and integrity” and reflect

ing on him “ as an individual” (R. 712, 713, 724). He also

felt that the other statements in the passages complained

of, such as that alluding to the bombing of King’s home,

referred to the Commissioners, to the Police Department

and to him because they were contained in the same para

graphs as statements mentioning police activities (R. 717-

718), though he conceded that as “ far as the expulsion of

students is concerned, that responsibility rests with the

State Department of Education” (R. 716).

In addition to this testimony as to the respondent’s

feelings, six witnesses were permitted to express their

opinions of the connotations of the statements and their

effect on respondent’s reputation.

Grover C. Hall, editor of the Montgomery Advertiser,

who had previously written an editorial attacking the ad

vertisement (R. 607, 613, 949), testified that he thought he

would associate the third paragraph “ with the City Gov

ernment—the Commissioners” (R. 605) and “ would natur

ally think a little more about the police commissioner” (R.

608). It was “ the phrase about starvation” that led to the

association; the “ other didn’t hit” him “ with any particu

lar force” (R. 607, 608). He thought “ starvation is an

instrument of reprisal and would certainly be indefensible

. . . in any case” (R. 605).

12

Arnold D. Blackwell, a member of the Water Works

Board appointed by the Commissioners (R. 621) and a busi

nessman engaged in real estate and insurance (R. 613),

testified that the third paragraph was associated in his

mind with “ the Police Commissioner” and the “ people on

the police force ’ ’ ; that if it were true that the dining hall

was padlocked in an effort to starve the students into sub

mission, he would “ think that the people on our police

force or the heads of our police force were acting without

their jurisdiction and would not be competent for the posi

tion” (R. 617, 624). He also associated the statement about

“ truck-loads of police” with the police force and the Police

Commissioner (R. 627). With respect to the “ Southern

violators” passage, he associated the statement about the

arrests with “ the police force” but not the “ sentences

above that” (R. 624) or the statement about the charge of

perjury (R. 625).

Harry W. Kaminsky, sales manager of a clothing store

(R. 634) and a close friend of the respondent (R. 644), also

associated the third paragraph with “ the Commissioners”

(R. 635), though not the statement about the expulsion of

the students (R. 639). Asked on direct examination about

the sentences in the sixth paragraph, he said that he “ would

say that it refers to the same people in the paragraph that

we look at before” , i.e., to “ The -Commissioners” , includ

ing the respondent (R. 636). On cross-examination, how

ever, he could not say that he associated those statements

with the respondent, except that he thought that the refer

ence to arrests “ implicates the Police Department . . . or

the authorities that would do that—arrest folks for speed

ing and loitering and such as that” (R. 639-640). In gen

eral, he would “ look at” the respondent when he saw “ the

Police Department” (R. 641).

13

H. M. Price, Sr., owner of a small food equipment busi

ness (R. 644), associated “ the statements contained” in

both paragraphs with “ the head of the Police Department” ,

the respondent (R. 646). Asked what it was that made him

think of the respondent, he read the first sentence of the

third paragraph and added: “ Now, I would just auto

matically consider that the Police Commissioner in Mont

gomery would have to put his approval on those kind of

things as an individual” (R. 647). I f he believed the state

ments contained in the two paragraphs to be true, he would

“ decide that we probably had a young Gestapo in Mont

gomery” (R. 645-646).

William M. Parker, Jr., a friend of the respondent and

of Mayor James (R. 651), in the service station business,

associated “ those statements in those paragraphs” with

the City Commissioners (R. 650) and since the respondent

“ was the Police Commissioner” , he “ thought of him first”

(R. 651). I f he believed the statements to be true, he testi

fied that he would think the respondent “ would be trying to

run this town with a strong arm— strong armed tactics,

rather, going against the oath he took to run his office in a

peaceful manner and an upright manner for all citizens of

Montgomery” (R. 650).

Finally, Horace W. White, proprietor of the P. C. White

Truck Line (R. 662), a former employer of respondent (R.

664), testified that both of the paragraphs meant to him

“ Mr. L. B. Sullivan” (R. 663). The statement in the adver

tisement that indicated to him that it referred to the re

spondent was that about “ truck-loads of police” , which

made him think of the police and of respondent “ as being

the head of the Police Department” (R. 666). I f he be

14

lieved the statements, he doubted whether he “ would want

to be associated with anybody who would he a party to

such things” (R. 664) and he would not re-employ respond

ent for P. C. White Truck Line if he thought that “ he al

lowed the Police Department to do the things the paper say

he did” (R. 667, 664, 669).

None of the six witnesses testified that he believed any

of the statements that he took to refer to respondent and

all hut Hall specifically testified that they did not believe

them (R. 623, 636, 647, 651, 667). None was led to think

less kindly of respondent because of the advertisement (R.

625, 638, 647, 651, 666). Nor could respondent point to any

injury that he had suffered or to any sign that he was held

in less esteem (R. 721-724).

Four of the witnesses, moreover, Blackwell, Kaminsky,

Price and Parker, saw the publication first when it was

shown to them in the office of respondent’s counsel to equip

them as witnesses (R. 618, 637, 643, 647, 649). Their testi

mony should, therefore, have been disregarded under the

trial court’s instruction that the jury should “ disregard . . .

entirely” the testimony of any witness “ based upon his

reading of the advertisement complained of here, only after

having been shown a copy of same by the plaintiff or his

attorneys” (R. 833). White did not recall when he first

saw the advertisement; he believed, though he was not sure,

that “ somebody cut it out of the paper and mailed it ” to

him or left it on his desk (R. 662, 665, 668). Only Hall,

whose testimony was confined to the phrase about starving

students into submission (R. 605, 607), received the publi

cation in ordinary course at The Montgomery Advertiser

(R. 606, 726-727).

15

4. The Circumstances of the Publication.—The adver

tisement was published by The Times upon an order from

the Union Advertising Service, a reputable New York ad

vertising agency, acting for the Committee to Defend

Martin Luther King (R. 584-585, 737, PL Ex. 350, R. 1957).

The order was dated March 28,1960, but the proposed type

script of the ad had actually been delivered on March 23

by John Murray, a writer acting for the Committee, who

had participated in its composition (R. 731, 805). Murray

gave the copy to Gershon Aaronson, a member of the Na

tional Advertising Staff of The Times specializing in “ edi

torial type” advertisements (R. 731, 738), who promptly

passed it on to technical departments and sent a thermo-fax

copy to the Advertising Acceptability Department, in

charge of the screening of advertisements (R. 733, 734, 756).

D. Vincent Redding, the manager of that department, read

the copy on March 25 and approved it for publication (R.

758). He gave his approval because he knew nothing to

cause him to believe that anything in the proposed text was

false and because it bore the endorsement of “ a number of

people who are well known and whose reputation” he “ had

no reason to question” (R. 758, 759-760, 762-763). He did

not make or think it necessary to make any further check

as to the accuracy of the statements (R. 765, 771).

When Redding passed on the acceptability of the adver

tisement, the copy was accompanied by a letter from A.

Philip Randolph, Chairman of the Committee, to Aaron

son, dated March 23 (R. 587, 757, Def. Ex. 7, R. 1992) and

reading:

“ This will certify that the names included on the

enclosed list are all signed members of the Committee

16

to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for

Freedom in the South.

“ Please be assured that they have all given us per

mission to use their names in furthering the work

of our Committee.”

The routine of The Times is to accept such a letter from

a responsible person to establish that names have not been

used without permission and Bedding followed that prac

tice in this case (R. 759). Each of the individual defend

ants testified, however, that he had not authorized the Com

mittee to use his name (R. 787-804) and Murray testified

that the original copy of the advertisement, to which the

Randolph letter related, did not contain the statement “ We

in the South . . . warmly endorse this appeal” or any

of the names printed thereunder, including those of these

defendants. That statement and those names were added,

he explained, to a revision of the proof on the suggestion

of Bayard Rustin, the Director of the Committee. Rustin

told Murray that it was unnecessary to obtain the consent

of the individuals involved since they were all members

of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, as indi

cated by its letterhead, and “ since the SCLC supports the

work of the Committee . . . he [Rustin] . . . felt that

there would be no problem at all, and that you didn’t

even have to consult them” (R. 806-809). Redding did not

recall this difference in the list of names (R. 767), though

Aaronson remembered that there “ were a few changes

made . . . prior to publication” (R. 739).

The New York Times has set forth in a booklet its “ Ad

vertising Acceptability Standards” (R. 598, PI. Ex. 348,

Exh. F, R. 1952) declaring, inter alia, that The Times does

17

not accept advertisements that are fraudulent or deceptive,

that are “ ambiguous in wording and . . . may mislead”

or “ [ajttacks of a personal character” . In replying to

the plaintiff’s interrogatories, Harding Bancroft, Secre

tary of The Times, deposed that “ as the advertisement

made no attacks of a personal character upon any indi

vidual and otherwise met the advertising acceptability

standards promulgated” by The Times, D. Vincent Redding

had approved it (R. 585).

Though Redding and not Aaronson was thus responsible

for the acceptance of the ad, Aaronson was cross-examined

at great length about such matters as the clarity or am

biguity of its language (R. 741-753), the court allowing the

interrogation on the stated ground that “ this gentleman

here is a very high official of The Times” , which he, of

course, was not (R. 744). In the course of this colloquy,

Aaronson contradicted himself on the question whether the

word “ they” in the “ Southern violators” passage refers

to “ the same people” throughout or to different people,

saying first “ It is rather difficult to tell” (R. 745) and

later: “ I think now that it probably refers to the same

people” (R. 746). Redding was not interrogated on this

point, which respondent, in his Brief in Opposition, deemed

established by what Aaronson “ conceded” (Brief in Oppo

sition, p. 7).

The Times was paid “ a little over” $4800 for the pub

lication of the advertisement (R. 752). The total circu

lation of the issue of March 29, 1960, was approximately

650,000, of which approximately 394 copies were mailed

to Alabama subscribers or shipped to newsdealers in the

State, approximately 35 copies going to Montgomery

County (R. 601-602, PI. Ex. 348, R. 1942-1943).

18

5. The Response to the Demand for a Retraction.— On

April 8, 1960, respondent wrote to the petitioner and to the

four individual defendants, the letters being erroneously-

dated March 8 (R. 588, 671, 776, Pl. Ex. 348, 355-358, R.

1949,1962-1968). The letters, which were in identical terms,

set out the passages in the advertisement complained of by-

respondent, asserted that the “ foregoing matter, and the

publication as a whole charge me with grave misconduct and

of [sic] improper actions and omissions as an offiical of the

City of Montgomery” and called on the addressee to “ pub

lish in as prominent and as public a manner as the fore

going false and defamatory material contained in the

foregoing publication, a full and fair retraction of the

entire false and defamatory matter so far as the same

relates to me and to my conduct and acts as a public official

of the City of Montgomery, Alabama.”

TJpon receiving this demand and the report from Don

McKee, the Times stringer in Montgomery referred to

above (p. 7), petitioner’s counsel wrote to the respondent

on April 15, as follows (R. 589, PI. Ex. 363, R. 1971) :

Dear Mr. Commissioner:

Your letter of April 8 sent by registered mail to

The New York Times Company has been referred for

attention to us as general counsel.

You will appreciate, we feel sure, that the state

ments to which you object were not made by The New

York Times but were contained in an advertisement

proffered to The Times by responsible persons.

We have been investigating the matter and are

somewhat puzzled as to how you think the statements

in any way reflect on you. So far, our investigation

19

would seem to indicate that the statements are sub

stantially correct with the sole exception that we find

no justification for the statement that the dining hall

in the State College was “ padlocked in an attempt to

starve them into submission.”

We shall continue to look into the subject matter

because our client, The New York Times, is always

desirous of correcting any statements which appear in

its paper and which turn out to be erroneous.

In the meanwhile you might, if you desire, let us

know in what respect you claim that the statements in

the advertisement reflect on you.

Very truly yours,

L ord, Day & L ord

The respondent filed suit on April 19, without answering

this letter.

Subsequently, on May 9, 1960, Governor John Patterson

of Alabama, sent a similar demand for a retraction to The

Times, asserting that the publication charged him “ with

grave misconduct and of [sic] improper actions and omis

sions as Governor of Alabama and Ex-Officio Chairman of

the State Board of Education of Alabama” and demanding

publication of a retraction of the material so far as it re

lated to him and to his conduct as Governor and Ex-Officio

Chairman.

On May 16, the President and Publisher of The Times

wrote Governor Patterson as follows (R. 773, Def. Ex. 9,

R. 1998):

Dear Governor Patterson:

In response to your letter of May 9th, we are en

closing herewith a page of today’s New York Times

which contains the retraction and apology requested.

20

As stated in the retraction, to the extent that any

one could fairly conclude from the advertisement that

any charge was made against you, The New York

Times apologizes.

Faithfully yours,

Orvel Dryfoos

The publication in The Times (PI. Ex. 351, R. 1958),

referred to in the letter, appeared under the headline

“ Times Retracts Statement in A d ” and the subhead “ Acts

on Protest of Alabama Governor Over Assertions in Segre

gation Matter” . After preliminary paragraphs reporting

the Governor’s protest and quoting his letter in full, in

cluding the specific language of which he complained, the

account set forth a “ statement by The New York Times”

as follows:

The advertisement containing the statements to

which Governor Patterson objects was received by The

Times in the regular course of business from and paid

for by a recognized advertising agency in behalf of a

group which included among its subscribers well-

known citizens.

The publication of an advertisement does not con

stitute a factual news report by The Times nor does

it reflect the judgment or the opinion of the editors of

The Times. Since publication of the advertisement,

The Times made an investigation and consistent with

its policy of retracting and correcting any errors or

misstatements which may appear in its columns, here

with retracts the two paragraphs complained of by the

Governor.

The New York Times never intended to suggest by

the publication of the advertisement that the Honor

21

able John Patterson, either in his capacity as Governor

or as ex-officio chairman of the Board of Education of

the State of Alabama, or otherwise, was guilty of

“ grave misconduct or improper actions and omission” .

To the extent that anyone can fairly conclude from the

statements in the advertisement that any such charge

was made, The New York Times hereby apologizes to

the Honorable John Patterson therefor.

The publication closed with a recapitulation of the names

of the signers and endorsers of the advertisement and of

the officers of the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King.

In response to a demand in respondent’s pre-trial in

terrogatories to “ explain why said retraction was made

but no retraction was made on the demand of the plaintiff” ,

Mr. Bancroft, Secretary of The Times, said that The

Times published the retraction in response to the Gov

ernor’s demand “ although in its judgment no statement in

said advertisement referred to John Patterson either per

sonally or as Governor of the State of Alabama, nor re

ferred to this plaintiff [Sullivan] or any of the plaintiffs

in the companion suits. The defendant, however, felt that

on account of the fact that John Patterson held the high

office of Governor of the State of Alabama and that he

apparently believed that he had been libeled by said ad

vertisement in his capacity as Governor of the State of

Alabama, the defendant should apologize” (R. 595-596, PI.

Ex. 348, R. 1942). In further explanation at the trial,

Bancroft testified: “ We did that because we didn’t want

anything that was published by The Times to be a re

flection on the State of Alabama and the Governor was, as

far as we could see, the embodiment of the State of

Alabama and the proper representative of the State and,

22

furthermore, we had by that time learned more of the

actual facts which the ad purported to recite and, finally,

the ad did refer to the action of the State authorities and

the Board of Education presumably of which the Governor

is ex-officio chairman . . . ” (R. 776-777). On the other hand,

he did not think that “ any of the language in there re

ferred to Mr. Sullivan” (R. 777).

This evidence, together with Mr. Bancroft’s further

testimony that apart from the statement in the advertise

ment that the dining hall was padlocked, he thought that

“ the tenor of the content, the material of those two para

graphs in the ad . . . are . . . substantially correct” (R. 781,

785), was deemed by the Supreme Court of Alabama to lend

support to the verdict of the jury and the size of its award

(R. 1178).

6. The Rulings on the Merits.—The Circuit Court held

that the facts alleged and proved sufficed to establish lia

bility of the defendants, if the jury was satisfied that the

statements complained of by respondent were published

of and concerning him. Overruling a demurrer to the com

plaint (R. 108) and declining to direct a verdict for peti

tioner (R. 728-729, 818), the court charged the jury (R.

819-826) that the statements relied on by the plaintiff were

“ libelous per se” ; that “ the law implies legal injury from

the bare fact of the publication itself” ; that “ falsity and

malice are presumed” ; that “ [gjeneral damages need not

be alleged or proved but are presumed” (R. 824); and

that “ punitive damages may be awarded by the jury even

though the amount of actual damages is neither found nor

shown” (R. 825). While the court instructed, as requested,

that “ mere negligence or carelessness is not evidence of

actual malice or malice in fact, and does not justify an

23

award of exemplary or punitive damages” (R. 836), it re

fused to instruct that the jury must be “ convinced” of

malice, in the sense of “ actual intent” to harm or “ gross

negligence and recklessness” to make such an award (R.

844). It also declined to require that a verdict for respond

ent differentiate between compensatory and punitive dam

ages (R. 846).

Petitioner challenged these rulings as an abridgment

of the freedom of the press, in violation of the First and

the Fourteenth Amendments, and also contended that the

verdict was confiscatory in amount and an infringement

of the constitutional protection (R. 73-74, 898, 929-930, 935,

936-937, 945-946, 948). A motion for new trial, assigning

these grounds among others (R. 896-949), was denied by

the Circuit Court (R. 969).

The Supreme Court of Alabama sustained these rulings

on appeal (R. 1139, 1180). It held that where “ the words

published tend to injure a person libeled by them in his

reputation, profession, trade or business, or charge him

with an indictable offense, or tends to bring the individual

into public contempt,” they are “ libelous per se” ; that

“ the matter complained of is, under the above doctrine,

libelous per se, if it was published of and concerning the

plaintiff” (R. 1155); and that it was actionable without

“ proof of pecuniary injury . . ., such injury being im

plied” (R. 1160-1161). It found no error in the trial

court’s ruling that the complaint alleged and the evidence

established libelous statements which the jury could find

were “ of and pertaining to” respondent (R. 1158, 1160),

reasoning as follows (R. 1157):

“ We think it common knowledge that the average

person knows that municipal agents, such as police and

24

firemen, and others, are under the control and direction

of the city governing body, and more particularly under

the direction and control of a single commissioner. In

measuring the pei'formance or deficiencies of such

groups, praise or criticism is usually attached to the

official in complete control of the body.”

The Court also approved the trial court’s charge as “ a

fair, accurate and clear expression of the governing legal

principles” (R. 1167) and sustained its determination that

the damages awarded by the verdict were not excessive

(R. 1179). On the latter point, the Court endorsed a state

ment in an earlier opinion that there “ is no legal measure

of damages in cases of this character” (R. 1177) and held

to be decisive that ‘ ‘ The Times in its own files had articles

already published which would have demonstrated the

falsity of the allegations in the advertisement” ; that “ The

Times retracted the advertisement as to Governor Pat

terson, but ignored this plaintiff’s demand for retraction”

though the “ matter contained in the advertisement was

equally false as to both parties” ; that in “ the trial below

none of the defendants questioned the falsity of the alle

gations in the advertisement” and, simultaneously, that

“ during his testimony it was the contention of the Secre

tary of The Times that the advertisement was ‘ substan

tially correct’ ” (R. 1178).

Petitioner’s submissions under the First and the Four

teenth Amendments (assignments of error 81, 289-291, 294,

296, 298, 306-308, 310; R. 1055, 1091-1094, 1096-1097, 1098)

were summarily rejected with the statements that the

“ First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution does not pro

tect libelous publications” and the “ Fourteenth Amend

ment is directed against State action and not private

action” (R. 1160).

25

7. The Jurisdiction of the Alabama Courts.—Respond

ent sought to effect service in this action (R. 11) by deliv

ery of process to Don McKee, the New York Times stringer

in Montgomery, claimed to be an agent under § 188, Ala

bama Code of 1940, title 7 (Appendix A, infra, pp. 91-92),

and by delivery to the Secretary of State under §199(1),

the “ long-arm” statute of the State (Appendix A, infra,

pp. 92-95). Petitioner, appearing specially and only for this

purpose, moved to quash the service on the ground, among

others, that the subjection of The Times to Alabama juris

diction in this action would transcend the territorial limi

tations of due process in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, impose a burden on interstate commerce for

bidden by the Commerce Clause and abridge the freedom

of the press (R. 39, 43-44, 47; see also, e.g., R. 129).

The evidence adduced upon the litigation of the motion

(R. 130-566) established the following facts:

Petitioner is a New York corporation which has not

qualified to do business in Alabama or designated anyone

to accept service of process there (R. 134-135). It has no

office, property or employees resident in Alabama (R. 146,

403-404, 438-439). Its staff correspondents do, however, visit

the State as the occasion may arise for purposes of news

gathering. From the beginning of 1956 through April, 1960,

nine correspondents made such visits, spending, the courts

below found, 153 days in Alabama, or an average of some

thirty-six man-days per year. In the first five months of

1960, there were three such visits by Claude Sitton, the

staff correspondent stationed in Atlanta (R. 311-314, 320,

PL Ex. 91-93, R. 1356-1358) and one by Harrison Salis

bury (R. 145, 239, PI. Ex. 117, R. 1382). The Times also

had an arrangement with newspapermen, employed by

Alabama journals, to function as “ stringers” , paying

26

them for stories they sent in that were requested or

accepted at the rate of a cent a word and also using them

occasionally to furnish information to the desk (e . g R. 175,

176) or to a correspondent (R. 136-137, 140, 153, 154). The

effort was to have three such stringers in the State, includ

ing one in Montgomery (R. 149, 309) but only two received

payments from The Times in 1960, Chadwick of South Mag

azine, who was paid $155 to July 26, and McKee of The

Montgomery Advertiser, who was paid $90, covering both

dispatches and assistance given Salisbury (R. 140, 143, 155,

159, 308-309, 441). McKee was also asked to investigate the

facts relating to respondent’s claim of libel, which he did

(R. 202, 207). The total payments made by petitioner to

stringers throughout the country during the first five

months of 1960 was about $245,000 (R. 442). Stringers are

not treated as employees for purposes of taxes or employee

benefits (R. 439-440, 141-143).

The advertisement complained of in this action was

prepared, submitted and accepted in New York, where the

newspaper is published (R. 390-393, 438). The total daily

circulation of The Times in March, 1960, was 650,000, of

which the total sent to Alabama was 394 — 351 to mail sub

scribers and 43 to dealers. The Sunday circulation was

1,300,000, of which the Alabama shipments totaled 2,440

(Def. Ex. No. 4, R. 1981, R. 401-402). These papers were

either mailed to subscribers who had paid for a subscription

in advance (R. 427) or they were shipped prepaid by rail

or air to Alabama newsdealers, whose orders were unsolic

ited (R. 404-408, 444) and with whom there was no con

tract (R. 409). The Times would credit dealers for papers

which were unsold or arrived late, damaged or incomplete,

the usual custom being for the dealer to get the irregu

larities certified by the railroad baggage man upon a card

27

provided by The Times (R. 408-409, 410-412, PI. Ex. 276-

309, R. 1751-1827, R. 414, 420-426), though this formality

had not been observed in Alabama (R. 432-436). Gross

revenue from this Alabama circulation was approximately

$20,000 in the first five months of 1960 of a total gross

from circulation of about $8,500,000 (R. 445). The Times

made absolutely no attempt to solicit or promote its sale

or distribution in Alabama (R. 407-408, 428, 450, 485).

The Times accepted advertising from Alabama sources,

principally advertising agencies which sent their copy to

New York, where any contract for its publication was made

(R. 344-349, 543); the agency would then be billed for cost,

less the amount of its 15% commission (R. 353-354). The

New York Times Sales, Inc., a wholly-owned subsidiary

corporation, solicited advertisements in Alabama, though

it had no office or resident employees in the State (R. 359-

361, 539, 482). Two employees of Sales, Inc. and two em

ployees of The Times spent a total of 26 days in Alabama

for this purpose in 1959; and one o f the Sales, Inc. men

spent one day there before the end of May in 1960 (R. 336-

338, Def. Ex. 1, R. 1978, 546, 548-551). Alabama advertis

ing linage, both volunteered and solicited, amounted to 5471

in 1959 of a total of 60,000,000 published; it amounted to

13,254 through May of 1960 of a total of 20,000,000 lines (R.

342-344, 341, Def. Ex. 2, R. 1979). An Alabama supplement

published in 1958 (R. 379, PI. Ex. 273, R. 1689-1742) pro

duced payments by Alabama advertisers of $26,801.64 (R.

380). For the first five months of 1960 gross revenue from

advertising placed by Alabama agencies or advertisers

was $17,000 to $18,000 of a total advertising revenue of

$37,500,000 (R. 443). The gross from Alabama advertising

and circulation during this period was $37,300 of a national

total of $46,000,000 (R. 446).

28

On these facts, the courts below held that petitioner was

subject to the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court in this

action, sustaining both the service on McKee as a claimed

agent and the substituted service on the Secretary of State

and rejecting the constitutional objections urged (E. 49,

51-57, 1139, 1140-1151). Both courts deemed the news

gathering activities of correspondents and stringers, the

solicitation and publication of advertising from Alabama

sources and the distribution of the paper in the State to

constitute sufficient Alabama “ contacts” to support the

exercise of jui'isdiction (R. 56-57, 1142-1147). They also

held that though petitioner had appeared specially upon the

motion for the sole purpose of presenting these objections,

as permitted by the Alabama practice, the fact that the

prayer for relief asked for dismissal for “ lack of jurisdic

tion of the subject matter” of the action, as well as want of

jurisdiction of the person of defendant, constituted a gen

eral appearance and submission to the jurisdiction of the

Court (R, 49-51, 1151-1153).

Summary of Argument

I

Under the doctrine of “ libel per se” applied below, a

public official is entitled to recover “ presumed” and puni

tive damages for a publication found to be critical of the

official conduct of a governmental agency under his general

supervision if a jury thinks the publication “ tends” to

“ injure” him “ in his reputation” or to “ bring” him “ into

public contempt” as an official. The publisher has no de

fense unless he can persuade the jury that the publication

is entirely true in all its factual, material particulars. The

29

doctrine not only dispenses with proof of injury by the

complaining official, but presumes malice and falsity as

well. Such a rule of liability woi’ks an abridgment of the

freedom of the press.

The court below entirely misconceived the constitutional

issues, in thinking them disposed of by the propositions

that “ the Constitution does not protect libelous publica

tions” and that the “ Fourteenth Amendment is directed

against State action and not private action” (B. 1160). The

requirements of the First Amendment are not satisfied by

the “ mere labels” of State law. N. A. A. C. P. v. Button,

371 U. S. 415, 429 (1963); see also Beauharnais v. Illinois,

343 U. S. 250, 263-264 (1952). The rule of law and the judg

ment challenged by petitioner are, of course, state action

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.

If libel does not enjoy a talismanic insulation from the

limitations of the First and Fourteenth Amendments, the

principle of liability applied below infringes “ these basic

constitutional rights in their most pristine and classic

form.” Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229, 235

(1963). Whatever other ends are also served by freedom of

the press, its safeguard “ was fashioned to assure unfet

tered interchange of ideas for the bringing about of politi

cal and social changes desired by the people.” Roth v.

United States, 354 U. S. 476, 484 (1957). It is clear that the

political expression thus protected by the fundamental law

is not delimited by any test of truth, to be administered by

juries, courts, or by executive officials. N. A. A. C. P. v.

Button, supra, at 445; Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S.

296, 310 (1940). It also is implicit in this Court’s decisions

that speech or publication which is critical of governmental

or official action may not be repressed upon the ground that

30

it diminishes the reputation of those officers whose conduct

it deplores or of the government of which they are a part.

The closest analogy in the decided cases is provided by

those dealing with contempt, where it is settled that concern

for the dignity and reputation of the bench does not support

the punishment of criticism of the judge or his decision,

whether the utterance is true or false. Bridges v. Cali

fornia, 314 U. S. 252, 270 (1941) ; Pennekamp v. Florida,

328 U. S. 331, 342 (1946); Wood v. Georgia, 370 U. S. 375

(1962). Comparable criticism of an elected, political official

cannot consistently be punished as a libel on the ground that

it diminishes his reputation. I f political criticism could be

punished on the ground that it endangers the esteem with

which its object is regarded, none safely could be uttered

that was anything but praise.

That neither falsity nor tendency to harm official reputa

tion, nor both in combination, justifies repression of the

criticism of official conduct was the central lesson of the

great assault on the short-lived Sedition Act of 1798, which

the verdict of history has long deemed inconsistent with the

First Amendment. The rule of liability applied below is

even more repressive in its function and effect than that

prescribed by the Sedition A ct: it lacks the safeguards of

criminal sanctions; it does not require proof that the de

fendant’s purpose was to bring the official into contempt or

disrepute; it permits, as this case illustrates, a multiplica

tion of suits based on a single statement; it allows legally

limitless awards of punitive damages. Moreover, reviving

by judicial decision the worst aspect of the Sedition Act,

the doctrine of this case forbids criticism of the govern

ment as such on the theory that top officers, though they are

31

not named in statements attacking the official conduct of

their agencies, are presumed to be hurt because such cri

tiques are “ attached to” them (R. 1157).

Assuming, without conceding, that the protection of

official reputations is a valid interest of the State and that

the Constitution allows room for the “ accommodation” of

that interest and the freedom of political expression, the

rule applied below is still invalid. It reflects no compromise

of the competing interests; that favored by the First

Amendment has been totally rejected, the opposing interest

totally preferred. If there is scope for the protection of

official reputation against criticism of official conduct,