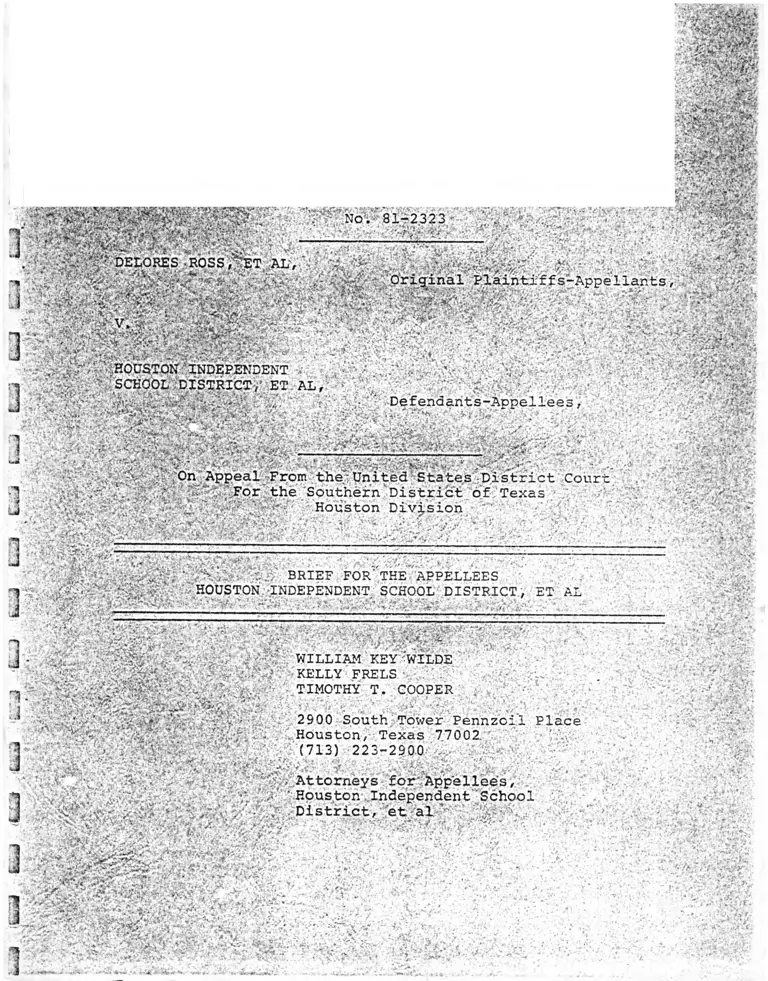

Ross v. Houston Independent School Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

May 1, 1982

79 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ross v. Houston Independent School Brief for Appellees, 1982. 307f494f-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/125979df-b20f-4b5e-8140-7c3dd449fd12/ross-v-houston-independent-school-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

J

-n

■3

3

| S g P ? •: No. 81—2323

. ■- •y'i''"'v'j'.’ i

W m S m :

...;■>«ir

J* -JraA5» 5

;?«Tr«r v̂ sSis

;V'.-. jjfe

:■ .,. , re-"-': : '■ ■ ■ •'■■■ . '••■■■ -,.■■.■ . •'- -•' .- ■'■■;■■DELORES ROSS ,^ET .AL ,

. Original Plaii

• » • * * ■ : * * ̂v* &*'• $^I&S£S&£‘ ••̂ vis v;'̂ w ??K - '••■Pi L- \:Tr. - ■ : :'> ■■■ '.-<3>»■ V* -

i-.: •»*• &>«§wSESJw • 4 ■'-'■• •:';•• :\>-UVyx

.,$ -i.;•-’rî: n \ /.■.'■»=«•?• i- ,• --■ >..*, • '-..vr; ..;

: * , ' * / • : ■ • - ' - - •• • ■ :•-rinal Plaintiffs-Appeliants,

HOUSTON ' INDEPENDENT I

SCHOOL ,DISTRICT/ ET AL,

■'11

> - *

.J

Lij

1

J

i

* m *L-

!Ss5-*Ss:'

D6t

•:v , . :. , i .-.. - '• ■ - • < * '> ! - : , ; ' ••

; . '^ V . . !V ^ ' v . 1(' ; ' ;i ^ y* \T... V’,^ ' £ -> *V • ' ;• ;

." ( * ■ .-,v • * • V; :*j' ' * W tV jij' ,_■£*.■£’S£VA -■■ ^ j,* 1 , i '- J" ’*-,.

Defendants-Appellees,

'• ‘ '/■. *■•/;•• vV ’ 'On Appeal From the'-United States District Court

- For the Southern 'District of Texas

»■'' Houston Division 1

■ : i :t,;V' BRIEF FOR" THE APPELLEES

■ HOUSTON. INDEPENDENT SCHOOL DISTRICT, ET A]

J-

T ?

..i

l|

3

T

J

SKjSJjg

:%•?/ V-̂ls ivoS

' *V>.̂V/yV,̂

WILLIAM KEY'-WILDE

| KELLY FRELS v, ,. ''

TIMOTHY T. COOPER -

2900 SouthJTower Pennzoil Place

Houston, Texas 77002.'

(713) 223-2900 .

Attorneys for Appellees,

' Houston. Independent' School

District, et al

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned, counsel of record, certifies that the

following listed persons have an interest in the outcome of

this case. These representations are made in order that the

Judges of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification

or possible recusal.

1. The Plaintiff, Delores Ross, and her mother, Mrs.

Mary Alice Benjamin;

n 2. The Plaintiff, Benva Delois Williams and her

father, Marion Williams;

3.r —

i

The Plaintiff, Ndapanda Nyamu, and her mother,

Mrs. Beneva Delois Williams Nyamu;

4. Weldon H. Berry, Jack Greenberg, James M. Nabrit,

III, Lowell Johnston and Bill Lann Lee, attorneys

for the Appellants;

H 5 • The National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People;

6 •

L*

The Houston Independent School District, whose

General Superintendent is Billy R. Reagan and

whose Superintendents are Ms. Patricia Shell, Mr.

Joseph Angle and Dr. Michael Say;

7. The members of the Board of Trustees of the

Houston Independent School District: Ray A.

Morrison, President, Mr. Tarrant Fendley, Vice-

President, Ms. Cathy Mincberg, Secretary, Mrs.

Marquis Alexander, Mr. Wiley Henry, Dr. J. C.

Jones, Mrs. Bobby Ann Peiffer, Ms. Tina Reyes, and

Mrs. Elizabeth Spates;

8 . Bracewell & Patterson, attorneys for the Appel

lees .

/

9TTCSK

Kelly Frels

1

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

£1

ij

The Defendants, the Houston Independent School Dist

rict, et al, believe that oral argument is necessary. This

case involves important issues of desegregation law pre

sented in the context of a large, mostly minority, urban

school district beset by the problems of mobility and trans

portation, demographic change, and special educational

needs. This case also involves a very belated request by

the Original Plaintiffs to change their theory of the case

and seek to institute a metropolitan remedy.

Because the issues in this case are important and in

many aspects, novel, the Defendants feel that oral argument

will prove helpful to this Court.

!

10TTCSD

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Certificate of Interested Persons .................. i

Statement Regarding Oral Argument .................. ii

Table of Contents .................................. iii

Index of Authorities ............. ................. v

Statement of the Issues ............................ 1

Statement of the Case .............................. 2

(i) Course of proceedings and disposition in

court below .............................. 2

(ii) Statement of the Facts .................... 5

Summary of the Argument ........................... 14

Argument ........................................... 15

I. INTRODUCTION ............................. 15

II. THE HISD IS A UNITARY SCHOOL DISTRICT ___ 15

A. The Remaining One Race Schools are

not Vestiges of the Formerly Dual

System .............................. 19

B. The HISD has Taken all Practicable

Steps to Desegregate the Schools .... 23

III. THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT IN DENYING

THE APPELLANTS' MOTION FOR LEAVE TO AMEND

AND TO ADD ADDITIONAL PARTIES ........... 36

A. The District Court Properly Denied

the Original Plaintiffs' Motion for

Leave to Amend Their Complaint ....... 37

B. The Proposed Additional Defendants

are not Necessary Parties .......... 47

C. The Proposed Defendants Should Not

be Joined Under Rule 21 ............ 49

Conclusion 50

Certificate of Service ............................. 51

10TTCSA

IV

INDEX OF AUTHORITIES

A. Cherney Disposal Co. v. Chicago and Suburban

Refuse Disposal Co., 68 F.R.D. 383 (N.D.

111. 1975), rev'd on other grounds, 484

F.2d 751 (7th Cir. 1973), cert, denied,

414 U.S. 1131, 94 S.Ct. 870 (1974)............... 39

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277 (8th

Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 449 U.S. 826.

101 S.Ct. 88 (1980).............................. 37

Axnco Engineering Co. v. Bud Radio, Inc. 38

F.R.D. 51 (N.D. Ohio 1965)...................... 48,49

Anderson Moorer, 372 F.2d 747 (5th Cir. 1967)..... 49

Barr Rubber Products Co. v. Sun Rubber Co.,

425 F.2d 1114 (2nd Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

400 U.S. 878 , 91 S.Ct. 118 (1970)___777777..... 49

Beloit Corporation v. Kusters, 13 F.R. Serv.

2d 174 (S.D.N.Y. 1969)........................... 41

Benger Laboratories. Ltd. v. R. K. Laros Co.,

24 F.R.D. 450 (E.D. Pa. 1959) .77777.777 ........ 49

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294,

75 S.Ct. 753 (1955).......................... 14,16,35

Calhoun v̂ _ Cook, 522 F.2d 717- (5th Cir. 1975)....... 32,37

Calhoun v. Cook, 525 F.2d 1203 (5th Cir. 1973)....... 24

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education,

377 F.Supp. 1123, (M.D. Ala. 1974), aff'd,

511 F.2d 1374 (5th Cir. 1975), cert.“denied,

423 U.S. 986, 96 S.Ct. 394 (5th Cir. 1975)...... 32

Chromalloy American Corporation v. Alloy

Surfaces Co., Inc., 351 F.Supp. 449 (D.

Del. 1972)___ 7777............................... 45

Conklin v . Joseph C. Hofgesang Sand Company,

Inc. , 565 F. 2d 405 (6th Cir. 1977)............. 42,44

County of Marin v. United States, 150 F.Supp.

619 (N.D. Cal. 1957), rev'd on other

grounds, 356 U.S. 412, 78 S.Ct. 880 (1958)...... 39

v

Data Digests, Inc. v. Standard & Poor's

Corporation, 57 F.R.D. 42 (S.D.N.Y. 1972)....... 41

Daves v. Payless Cashways, Inc., 661 F.2d

1022 (5th Cir. 1981)............................. 42

Davis v . Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33, 91 S.CtT

1289 (1971)....................................... 23

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board, 570 F.2d 1260 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 439 U.S. 1114, 99 S.Ct.

1016 (1979)....................................... 17

Dunn v. Koehring Company, 546 F.2d 1193

(5th Cir. 1977).................................. 41

Dyke v. Gulf Oil Corp., 601 F.2d 557 (Emerg.

C .A . 1979)........................................ 48

Eckels v. Ross, 402 U.S. 953, 91 S.Ct.

1614 (1971)....................................... 3

Fair Housing Development Fund Corporation

v. Burke, 55 F.R.D. 414 (E.D.N.Y. 1972)...... 47,49,50

Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178, 83 S.Ct.

227 (1962)................................ 36,38,39,46

Freeman v . Continental Gin Company, 381

F.2d 459 (5th Cir. 1967)........................ 39,40

Goss v. Revlon, Inc., 548 F.2d 405 (2nd Cir.

1976), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 968, 98

S.Ct. 514 (1977)................................. 43

Green v. County School Board of New

Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 88 S.Ct.

1689 (1968)....................................... 16

Hall v . Aetna Casualty and Surety Co., 617

' F . 2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1980)........................ 39

Harkless v . Sweeney Independent School

District, 554 F.2d 1353 (5th Cir. 1977).......... 38

Hayes v . New England Millwork Distributors,

Inc. , 602 F. 2d 15 (1st Cir. 1979)................. 43

vi

Horton v . Lawrence County Board of Education,

578 F . 2d 147 (5th Cir. 1978)................. 18,19,23

Johnson v . Sales Consultants, Inc., 61

F.R.D. 369 (N.D. 111. 1973)...................... 45

Kuhn v . Philadelphia Electric Company, 85

'F.R.D. 86 (E.D. Pa. 1979)........................ 45

La Chemise La Coste v. General Mills,

Inc., 53 F.R.D. 596 (D. Del. 1971),

aff'd 487 F. 2d 312 (3rd Cir. 1972)............... 47

Ladwig v. Travelers Insurance Company, 254

F . 2d 840 (5th Cir. 1958)......................... 41

Lamar v. American Finance System of Fulton

County, Inc., 577 F.2d 953 (5th Cir.

1978)............................................. 41

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 7117, 94

S.Ct. 3112 (1974)................................ 43

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 97 S.

Ct. 2749 (1977).................................. 34

Pasadena City Board of Education v.

Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 96 sTct.

2697 (1976)....................................... 19

Plaquemines Parish School Board v. United

States, 415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969).............. 34

Pollux Marine Agencies Inc. v. Louis

Dreyfus Corporation, 455 F.Supp. 211

(S.D. N.Y. 1978)................................. 38

Quality Education for all Children,

Inc. v. Board, 385 F.Supp. 803 (N.D.

111. 1974)........................................ 16

Reisner v. General Motors Corporation,

511 F.Supp. 1167 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)................. 41,45

Ross Eckels, 317 F.Supp. 512 (D.C.

Tex. 1970).................................... 2,5,24

Ross v. Eckels, 434 F.2d 1140 (5th Cir.

1970)........................................... 2,5,24

Vll

—Ti

1 ■;L'J

i Ross v. Eckels, F.Supp. (S.D. Tex.. No.

10,444 , Aug. 6, 1971)..........................

n1 i\... J

j

Ross v. Peterson, 5 Race Rel. L. Reo. 703

(S.D. Tex. 1960), aff’d sub nom., HISD

v. Ross, 282 F.2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960) .

stay and cert, denied, 364 U.S. 803,

81 S.Ct. 27 (1960).......................

' . j

Ross v. Rogers, 2 Race Rel. L. Reo. 1114

(S.D. Tex. 1957)..........................

n

Salwen Paper Company v. Merrill Lynch,

Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc., 79 F.R.D.

130 (S.D. N.Y. 1978)..........................

Sims v. Mack Truck Corporation, 488 F.Supp.

592 (E.D. Pa. 1980).......................

r Stout v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 537 F.2d 800 (5th Cir. 1976).......

1 ■:{

l -J

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board Of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S.Ct. 1267 (1971)....

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir.

1978).....................

passim

1 f. 17

; .ji j Tasby v. Wright, 520 F.Supp. 683 (N.D.

Tex. 1981).........................

1 i Thomson Newspapers, Inc. v. Toledo

Typographical Union, 20 F.R. Serv.

2d 78 (E.D. Mich. 1974)..................

Troxel Manufacturing Company v. Schwinn

Bicycle Company, 489 F.2d 968 (5th

Cir. 1973)........................

United States v. Board of Education of

Valdosta, Georgia, 576 F.2d 37 75th

Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 439 U.S. 1007,

99 S.Ct. 622 (1978).............................. 18

United States v. Board of School

Commissioners, 506 F.Supp. 657 (N.D.

Ind. 1979) aff’d in part, 637 F.2d 1011

(7th Cir. 1980)....................... 28

vixi

United States v. Texas, 447 F.2d 441 (5th

Cir. 1971) (C .A . 5281)........................... 43

Vaca Sipes, 386 U.S. 171, 87 S.Ct. 903

(1967)............................................ 43

Washburn v . Madison Square Garden Corp.,

340 F.Supp. 504 (S.D.N.Y. 1972)................. 46

WISP HISD, 583 F.2d 712 (5th Cir. 1978)........... 3

Zenith Radio Corporation v. Hazeltine

Research, Inc., 401 U.S. 321, 91 S.

Ct. 795 (1971)................................... 38

Zucker v. Sable, 426 F.Supp. 658 (S.D.N.Y.

1976)............................................. 41

MISCELLANEOUS

Bell, Brown v . Board of Education and the

Interest Convergence Dilemma, 93 Harv.

L. Rev. 518 (1980)............................... 35

3A Moore's Federal Practice § 19.07-9 [2]

(1982)............................................ 48

6 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice &

Procedure §1484 (1971)........ 7 ................. 38

6 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice &

Procedure: Civil §1487 (1971)................... 45

7 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice &

Procedure: Civil §1688 (1971)..7............... 49,50

10TTCSC

ix

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 81-2323

DELORES ROSS, et al §

§

Appellants §

§

v* §

§HOUSTON INDEPENDENT §

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al §

§Appellees §

Appeal From the United States District Court For The

Southern District of Texas, Houston Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

Statement of the Issues

1. Whether the District Court was correct in finding that

the HISD is a unitary school district, specifically finding that

the remaining one race schools are not vestiges of a former dual

system and that all practicable steps have been taken to eliminate

the vestiges of a dual system.

2. Whether the District Court correctly exercised its

discretion in denying the Original Plaintiffs' Motion for Leave to

Amend their Complaint, filed well after the hearing on unitary

status, wherein they sought to invoke a totally new theory of

liability involving numerous new parties.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

(i) Course of Proceedings and Disposition in Court Below

Initially filed in 1956, this case alleged that the Houston

Independent School District ("HISD" or "District") unconstitution

ally operated a segregated school district. The District Court

entered an order declaring the dual school system to be unconsti

tutional. Ross v. Rogers, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1114 (S.D. Tex.

1957). In 1960, the District Court ordered the implementation of

a grade per year desegregation plan. Ross v. Peterson, 5 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 703 (S.D. Tex. 1960), af f' d sub nom. , HISD v. Ross,

282 F. 2d 95 (5th Cir. 1960), stay and cert, denied, 364 U.S. 803,

81 S.Ct. 27 (1960).

Other orders_ designed to speed up the desegregaion process

were implemented in 1965. In July 1967, the United States inter

vened as a Plaintiff. On September 5, 1967, the District Court

adopted a freedom of choice desegregation plan.

In 1969 the Original Plaintiffs and the United States made a

motion for further relief, and the District Court ordered the

implementation of an equi-distant zoning plan along with other

requirements. Ross v. Eckels, 317 F. Supp. 512 (D.C. Tex. 1970).

The Plaintiffs appealed, and this Court affirmed the District

Court's decision as to the zoning of the elementary schools, but

modified its order by pairing 24 elementary schools, rezoning

another, and implementing a geographic capacity plan for the

secondary schools. Ross v, Eckels, 434 F. 2d 1140 (5th Cir.

1970) .

-2-

The HISD immediately implemented the plan ordered by the

Fifth Circuit except for the pairing of elementary schools. The

HISD filed an Application for Writ of Certiorari with the United

States Supreme Court to reverse the pairing order. At that time,

the Supreme Court had before it the case of Swann v. Charotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 91 S. Ct. 1267 (1971)

(hereinafter "Swann"). On April 20, 1971, Swann was decided, and

on May 3, 1971, the HISD's Application for Writ of Certiorari was

denied. Eckels v. Ross , 402 U.S. 953, 91 S. Ct. 1614 (1971).

While the Writ of Certiorari was pending, the District Court

entered its Amended Decree of September 18, 1970, which, as later

modified, is the order under which the HISD operates today.

(Record, Docket No. 257, hereinafter "R. No."). A motion by the

to modify the pairings was denied, and the schools were fully

paired in 1971-72.

"̂he failure of the pairings to maintain the desired integra

tion together with unhappiness in the HISD community led the HISD

to appoint a community task force to study alternatives to the

Pa^r^n<?s* As a result of this task force's recommendations, the

HISD proposed the Magnet School Plan to the District Court as an

alternative to the pairings. The plan was unopposed by any party

and was approved by the District Court on July 11, 1975. In the

the District Court also depaired the 24 elementary schools.

(R. No. 371).

The controversy over the formation of the proposed Westheimer

Independent School District (WISD) was a protracted affair of

eight year's duration which ended with this Court upholding the

-3-

District Court's injunction in 1978. WISP v. HISD, 583 F.2d 712

(5th Cir. 1978) .

The Hispanic intervenors first sought to intervene in 1971,

and intervention was granted in 1975 . (R. No. 373). No finding

of discrimination against Hispanics by the HISD has ever been

made. The Houston Teachers Association (HTA) was granted leave to

appear as amicus curiae in 1977. (R. No. 634).

On June 9, 1978, the District Court ordered the HISD to file

a plan for achieving unitary status. (R. No. 709). That plan was

filed August 9 , 1978 , (R. No. 712) , and a hearing concerning the

plan was held on September 29, 1978. A hearing began on June 4,

/

1979, concerning whether the HISD had reached unitary status. At

that trial, which lasted 17 days during June and October, 1979,

all parties were given a full opportunity to present any evidence

concerning the status of HISD's desegregation efforts. The

Original Plaintiffs presented no proposed findings and no evidence

to the District Court.

On September 28, 1979, the District Court ordered the Texas

Education Agency (TEA) to study the challenges faced by HISD and

other urban school districts and to develop a plan to meet these

challenges and provide for voluntary cooperation and sharing of

educational opportunities. (R. No. 763). As a result of this

, the TEA filed its plan for voluntary educational

cooperation on March 31, 1980. (R. No. 780a). The Voluntary

Interdistrict Education Plan (VIEP) is currently in operation in

Houston and Harris County.

-4-

On May 15 , 1980 , the United States filed a Motion for Leave

to Amend its Complaint and a Motion to add 22 surrounding school

districts plus several other governmental entities to the case.

(R. No. 784). The HISD and many of the parties sought to be added

opposed the Motion. (R. No. 787). On June 9, 1980, the Original

Plaintiffs filed virtually the same Motion as the United States

had filed the previous month. (R. No. 792). Those Motions were

t>Y the District Court on June 10 and 11, 1981 for the same

reasons. (R. Nos. 804 and 807) . Both the United States and the

Plaintiffs filed Motions to Alter or Amend the District

s decisions, (R. Nos. 810 and 808) , and the HISD opposed

both Motions. (R. Nos. 821 and 813).

On June 17, 1981, the District Court entered an order de

claring the HISD to be a unitary school district and denying the

Motions to Alter or Amend its prior decisions concerning the

amendment of the complaint and addition of other parties. (R.

No. 818)

(ii) Statement of Facts

The history of desegregation in the HISD from 1956 through

1969 is contained in Ross v_̂ Eckels, supra, 317 F. Supp. at

513-515. As stated previously, this Court modified the District

Court's 1970 decree and ordered a comprehensive plan for the HISD.

I

In approving the equidistant zoning plan for the elementary

schools, this Court stated that there would be 15 all or virtually

all black elementary schools remaining in the HISD. Ross v.

Eckels, supra, 434 F.2d at 1148. Numerous one race white

-5-

elementary schools were approved under the Fifth Circuit's

affirmance of the District Court's plan. 317 F. Supp. at 525-530.

The pairing of the 24 elementary schools, however, resulted

largely in pairing Hispanic and black students and required the

busing of those students. (Transcript of June and October, 1979,

Hearings, pp. 1456 , 1457 , hereinafter "Tr."; R. No. 818, p. 5).

The pairings were not popular with the patrons of the HISD and

eventually resulted in a decrease in the number and percentage of

anglo students attending the paired schools because in most

instances a significant number of anglo students moved from the

attendance areas. (Tr., pp. 1456, 1457, 1976). The failure of

the pairing to maintain integration over its five-year history

prompted the HISD's General Superintendent, Mr. Billy R. Reagan,

to recommend to the Board of Education that a tri-ethnic community

task force be appointed to consider an alternative to the

pairings. As a result, on November 25, 1974, the HISD's Board of

Education authorized the naming of the Task Force for Quality

Integrated Education (QIE) . The Task Force for QIE was asked to

develop a program that would: (1) stall or stop the flight of

residents from urban schools by offering quality education, (2)

promote integration, (3) offer more educational opportunities for

students of the District, and (4) bring about an alternative to

the pairing of schools which was not meeting the needs of the

District. (Tr. pp. 1737-1742; R. No. 361, p. 3).

The tri-ethnic Task Force for QIE spent many hours in study,

research and discussion from the time of formation until its

report was presented to the Board of Education on February 24,

-6-

1975. The Task Force for QIE, through sub-committees, conducted

an intense review of the District's operations, conducted com

munity hearings and visited other school districts which were

operating under desegregation orders which utilized the various

techniques enumerated in Swann. Numerous consultants were made

available to the Task Force for QIE, including representatives of

the Community Services Department of Justice Department. (Tr.

pp. 1737-1742; R. No. 361, p. 3; Transcript of September 29, 1978,

Hearing, hereinafter "1978 Tr.", pp. 196-198). The other parties

to the lawsuit were continually kept abreast of developments and

given the opportunity to provide input. The Task Force for QIE

recommended the development and implementation of a program of

magnet schools.

As a result of the Task Force's report, the HISD's Board of

Education appointed a tri-ethnic Administrative Task Team to

develop the Magnet School Plan for presentation to the HISD Board

and the Court. The major goals of the Magnet School Plan were to

provide quality education, increase the percentage of students

attending integrated schools, and decrease the number of one race

schools. (R. No. 361). This plan was approved by the District

Court on July 11, 1975, (R. No. 371), and Phase I was implemented

at the beginning of the 1975-76 school year. Phases II and III of

the Magnet School Plan were implemented in 1976-77 and in 1977-78.

The HISD has yearly evaluated and made changes in order to make

the Magnet School Plan more effective in meeting the expressed

purposes of the plan.

-7-

Since the implementation of the September 18 , 1970 Amended

Decree, it has not been necessary for the District Court to ever

be called upon to order the HISD to take action in meeting newly

enunciated judicial standards applicable to desegregation. The

development of the Magnet School Plan is one example. Several

other examples of the HISD's commitment to providing equity of

access to education are also illustrative. When the Supreme Court

found Hispanics to be a separate minority which could be subject

to discriminatory action as an identifiable ethnic group, the

District took several actions even though there has never been a

finding of discrimination against Hispanics as a separate ethnic

group within the HISD. First, in order to prevent ethnic

isolation of Hispanic students, the District amended its

majority-to-minority transfer provisions to include Hispanics and

provided free transportation for the transferring students.

Secondly, the District recognized Hispanic teachers as a separate

ethnic group for purposes of assignment, again to prevent the

ethnic isolation of Hispanic teachers.

A most significant example of the HISD's commitment to

achieving and maintaining a desegregated school system was its

opposition to the proposed Westheimer Independent School District

(WISD) . First in 1970-73 and then in 1976 to 1978 , the HISD

shouldered the laboring oar in the opposition to this divisive and

disruptive movement. The Original Plaintiffs did participate to

some degree in fighting the proposed WISD in 1970-73 , but did

virtually nothing in 1976-78. While the HISD's opposition to the

WISD was not supported by many groups in the Houston community,

-8-

the HISD did not capitulate in its efforts to prevent a result

that would have fostered racial and ethnic isolation and would

have seriously depleted the tax base of the HISD which, in turn,

would have delimited the educational opportunities for the

remaining students, the overwhelming majority of whom would be

minority.

During the 1970's the HISD developed many educational and

support programs to improve the educational opportunities for all

students. Operation Fail Safe, a parental involvement program,

was initiated in 1977 to help improve the achievement of students

who were having difficulties in school. (Tr. pp. 1828-1834; HISD

Exhibit Nos. 86-88, Hearing of June and October, 1979, hereinafter

"Ex. No."; See R. No. 755 for Exhibit List of HISD for 1979

Hearing) . The Basic Skills Program was instituted to help all

students improve their academic performance. These programs and

others reversed an eight year downward trend of test scores at the

elementary level and resulted in achievement of national norm

scores for grades one through six in 1978. (HISD Ex. 103).

In 1977, to assure minority participation in the District's

governance, the HISD converted from at large membership on the

school board to single member districts. (Tr., pp. 1710-1714).

Additional financial and educational resources were utilized

at various schools with high concentrations of students from low

socio-economic backgrounds and/or low achieving students. The

District embarked on an intensive nation-wide search for qualified

teachers for critical subjects such as math, science, bilingual

education, and special education. In 1978, the HISD also

-9-

instituted the Second Mile Plan, an incentive pay plan designed to

reduce teacher turnover and stabilize faculties. All of these

activities were accompanied by the implementation of the magnet

schools, Majority-to-Minority (M to M) transfers, faculty

desegregation, the facilities improvement program, desegregration

of extracurricular activities, expansion of transportation

provided to students, and other aspects of the 1970 Court Order.

In 1979 , the HISD operated a total of 226 schools — 170

elementary, 34 junior high or middle schools and 22 senior high

schools. (R. No. 747 , p. 14). The student enrollment for the

1978-1979 school year, was 201,960 students, of whom 45% were

black, 24.2% Hispanic and 30.8% anglo or other. (R. No. 747,

P* 14) . This compares to a student ethnic percentage in

1969-1970, the year before the comprehensive Court Order, of 33.5%

black, 13.4% Hispanic and 53.1% anglo or other. (HISD Ex. No. 6,

Hearing of September 29, 1978, hereinafter "1978 Ex. No."), The

present enrollment for 1981-82 is 44.3% black, 29.7% Hispanic, and

26% anglo or other, (with 2.6% of anglo being Asian-Americans).

(See Appendix "A", the current enrollment figures). In 1979, the

projected ethnic enrollment for 1985-86 was 48.8% black, 31.4%

Hispanic and 19.8% anglo or other. (R. No. 747, p. 14). Because

of a dramatic influx of Hispanic families into the Houston area,

those projections have now been revised to reflect a projected

enrollment in 1985-86 of approximately 38% black, 42% Hispanic,

and 20% anglo or other.

The number of one race schools has decreased greatly since

the implementation of the Court Order in 1970. (Ex. Nos. 57, 58,

-10-

60 , 63 , 64 , 65 , 66). On a bi-racial basis, there were 162 one

race schools in 1970-71 and 122 such schools in 1978-79. On a

tri-ethnic basis there were 133 one race schools in 1970-71 and

101 such schools in 1978—79. (Ex. No. 64) . This substantial

decrease in one race schools, which results in over one half of

the schools being integrated, has taken place in spite of the fact

that in 1978-79 under 30% of the students in the District were

anglo.

During this same period, the students availing themselves of

the tri-ethnic transfer (M to M) has steadily increased from 2,388

in 1970-1971 to 12,759 in 1978-79. (Ex. No. 96).

By 1979, the Magnet School Plan was expanded to 48 campuses:

31 elementary, 7 junior high schools and 10 high schools. In

1978-79, a total of 7,557 students transferred to the magnet

schools, and of these 3,411 are black, 1,544 Hispanic and 2,602

white. (Ex. No. 68) . The total number of students attending

schools with magnet programs, excluding the cluster centers, was

42,093. The cluster centers also provided part-time programs for

another 27,300 students with 7,200 participating in the Outdoor

Learning Centers, 17,700 taking part in the Anderson, Briargrove,

Port Houston and Sinclair centers, and 2,400 attending the People

Place Center. The total number of students impacted by the magnet

school programs in 1979 in the HISD was 69,393. (Ex. No. 68).

The maps submitted by the HISD at the 1979 hearings, showing

the elementary school zones for 1969-70, 1970-71, 1975-76 and

1978-79, dramatically reflect the growth in the minority popula

tion attending the HISD schools. (Ex. Nos. 35-50). These maps

-11-

also show the extensive natural integration of neighborhoods being

experienced in Houston, together with the effects of the Dis

trict's efforts to further integrate the schools through the

tri—ethnic transfers and the Magnet School Plan. These graphic

depictions are augmented by the study of Dr. Barton Smith of the

University of Houston, whose study was based on census tracts and

zip code zones. (Ex. No. 70).

These various maps and other evidence demonstrate that

noncontiguous pairings would have to be employed to achieve a

greater degree of desegregation without disturbing the naturally

integrated schools or those integrated through the tri-ethnic or

magnet school transfers. A review of the maps and existing

transportation routes reveals that the time and distance of travel

from one noncontiguous zone to another in congested Houston

traffic would be extensive and beyond any conceivably reasonable

requirements. (Ex. Nos. 35-50; 1978 Ex. Nos. 21-26A).

When considering the various desegregation plans submitted in

1969 and 1970, the District Court made projections of student

enrollment for each school within the HISD. The student

attendance at most of the schools the first year of the plan,

1970-71, was within the projections. Some one race black schools,

however, did not attain the 10% white enrollment projected. The

overwhelming reason for this was that the white students either

moved, attended private school, or simply did not attend school.

(Tr., pp. 1456 , 1457) .

The HISD resisted political and other challenges designed to

change the Court approved zone lines and enacted and enforced a

-12-

strict policy requiring the students to attend their designated

schools. See, Ross v^ Eckels (S.D. Tex., No. 10,444, August 6,

1971) . The District Court found that the HISD did all that was

practical in the circumstances to enforce the requirements of the

Court Order relating to student attendance. (R. No. 818, p. 27).

While the 1970 projections of this Court and the District

Court were not met in some schools, this is more than offset by

the overwhelming number of schools which have become integrated

which this Court did not project would be integrated. (Ex.

Nos. 62 and 66). Many of these schools have become integrated by

the changing housing patterns of Houston. (Tr., pp. 571-790).

Numerous others have, however, become integrated because of the

HISD's encouragement of tri-ethnic transfers and because of the

magnet schools. There were only five one race white elementary

schools in the District in 1978-79. (Ex. No. 64). At the present

time there are only 2 such schools, and one of them, Briargrove,

serves as a Cluster Center under the desegregation plan. (See

Appendix "A"). In fact, the approved transfers for the 1982-83

school year will result in a single one race white school

(Ashford, located on the far western edge of the HISD) and rela

tively few schools with over 35% or 50% white students. (See

Appendix "B").

A number of formerly all white schools have become one race

black schools. Each of these schools changed racial composition

by virtue of housing patterns or other factors over which the HISD

had no control. None of these schools became one race due to

discriminatory acts by the HISD. (Tr., pp. 571-790).

-13-

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The HISD has done all that is practicable to desegregate the

schools. Its faithful implementation of the zoning plans and

M-to-M transfers, approved by this Court, along with its initia

tion of the Magnet School Plan, has significantly decreased the

racial isolation in the HISD. The number of one race schools has

been decreased greatly in spite of declining anglo enrollment.

The District Court correctly held that the remaining one race

schools in the HISD are not vestiges of a former dual school

system. The District Court also correctly held that even if the

one race schools were vestiges, the implementation of the

techniques mentioned in Swann is not practicable in the HISD

because of a variety of factors.

The HISD's implementation of various educational programs

assures equal access to educational opportunities as is the

mandate of Erown.

The Original Plaintiffs' Motion for Leave to Amend their

Complaint and to Add Additional Parties comes too late. The

Original Plaintiffs waited to file their Motion, at the very

least, more than three years after they were apprised that

interdistrict transfers of black students occurred in Harris

County. They waited over seven months after the the 1979 hearing

concerning HISD's desegregation status to file their Motion.

Indeed, they only sprang to life when it became apparent that HISD

was a unitary school district. The belated attempt to avoid such

a ruling, along with prejudice to the HISD, were sufficient

reasons for the District Court to deny their Motions.

-14-

ARGUMENT

I.

INTRODUCTION

twenty—six years, this desegregation case comes to this

Court for a decision concerning whether the HISD has done all that

is practicable to purge itself of the vestiges of its former dual

school system. After considering the many actions voluntarily

undertaken by the HISD to eradicate the vestiges of the dual

system and provide equity of access to education, the many

demographic changes in the HISD, and the attendant practical

problems of implementing a desegregation plan in such a location,

the District Court determined that the HISD is a unitary school

district and has done all that is practicable to eliminate the

vestiges of its former dual system.

II.

THE HISD IS A UNITARY SCHOOL DISTRICT

The Original Plaintiffs challenge only the student assignment

portion of the District Court's Memorandum and Order of June 17,

1981. No challenge is made of the District Court's findings

concerning faculty assignment, transportation, extra curricula

activities or facilities. Those issues will not, therefore, be

addressed in this Brief. Suffice it to say that the District

Court's findings are correct and supported by ample evidence.

The crux of the Original Plaintiffs' argument is that more

racial mixing of students must be undertaken by the HISD. In

Section I of their Brief, the Original Plaintiffs recite many

-15-

standards concerning student assignment which have been discussed

in various contexts. The Original Plaintiffs conclude that the

HISD is not unitary because it has not attempted to utilize all

the student assignment techniques mentioned in Swann. (Brief for

Appellants, p. 25, hereinafter "Brief").

The Original Plaintiffs' contention that utilization of

pairing, rezoning, clustering, and/or cross-town busing is re

quired is erroneous. Swann does not say that utilization of the

techniques discussed is required; it merely says their utilization

is permissible. To infer such an inflexible requirement is

directly contrary to the long line of cases which hold that local

conditions must be analyzed and considered in fashioning an ap

propriate remedy because no two desegregation .cases are alike.

Green v • County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 88

S.Ct. 1689 (1968); Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75

S.Ct. 753 (1955) hereinafter "Brown II"); Quality Education for

a11 Children, Inc, v. Board, 385 F.Supp. 803 (N.D.I11. 1974). As

the Supreme Court has stated:

There is no universal answer to complex problems of

desegregation; there is obviously no one plan that will

do the job in every case. The matter must be addressed

in light of the circumstances present and the options

available in each instance. Green v. County School

Board of New Kent County, supra, 391 U.S. at 439“! 88

S.Ct. at 1695. ’

Accord, Swann, supra.

The Original Plaintiffs also cite Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d

1010 (5th Cir. 1978) for the proposition that the techniques of

Swann must be considered prior to a declaration of unitary status

and that time and distance studies must be undertaken. First,

-15-

this Court had already remanded Tasby specifically for considera

tion of the Swann techniques. Second, the general approach taken

by this Court is that practicable alternatives must be examined if

a substantial number of one race schools remain. No specific

alternatives are mandated. Davis v . East Baton Rouge Parish

SchoQl Board, 570 F.2d 1260 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 439

U.S. 1114, 99 S.Ct. 1016 (1979).

Notwithstanding the Original Plaintiffs' arguments, in the

case sub judice there has been utilization of some of the Swann

techniques and a great deal of consideration given to possible

utilization of other Swann techniques by both the HISD and the

District Court. As will be more fully discussed later, the tech

niques of rezoning, pairing and clustering have been utilized in

the HISD; and these and other techniques such as non-contiguous

pairing and further mandatory transfers have been considered by

the HISD and the District Court on several occasions. The

uncontroverted and extensive evidence submitted to the District

Court in 1979 supports its finding that further expansion of such

techniques are not practicable in the HISD. Never in the past

decade have the Original Plaintiffs asked for any modifications in

the present desegregation plan, and never have they made any

proposals for improvement or modification of the plan. In fact,

at the hearing held in 1979, the Original Plaintiffs presented not

one shred of evidence that the HISD was not unitary or that

utilization of other student assignment methods was practicable.

In contrast, the HISD made a lengthy presentation and submitted

overwhelming evidence that unitary status had been achieved.

-17-

The several cases cited by the Original Plaintiffs regarding

utilization of various tools such as pairing (Brief, p. 24) are in

no way relevant to this case because those cases all involve

school districts that are much smaller than the HISD, have dif

ferent demographics and mobility rates than the HISD, and involve

vastly different circumstances and problems.

In constructing a unitary school system, it is not required

that there be a racial balance in all of the schools. Swann v.

Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education, supra, 402 U.S. at 24,

91 S.Ct. at 1280; Horton v . Lawrence County Board of Education,

578 F .2d 147 (5th Cir. 1978); United States v. Board of Education

of Valdosta, Georgia, 576 F.2d 37 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied,

439 U.S. 1007, 99 S.Ct. 622 (1977).

The United States Supreme Court has recognized that difficult

problems may exist in "metropolitan areas with dense and shifting

population, numerous schools, congested and complex traffic

patterns." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 14, 91 S.Ct. at 1275 . The

Court has also observed that in "metropolitan areas minority

groups are often found concentrated in one part of the city", and

"certain schools may remain all or largely of one one race until

new schools can be provided or neighborhood patterns change."

Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 25, 91 S.Ct at 1280, 1281.

Where the presence of one race schools is due to factors such

as changing housing patterns, the school district is not respon

sible for integration or desegregation of those schools. Horton

Xjl Lawrence County Board of Education, supra. Even in former dual

systems, one race schools may remain if the district explains that

-18-

r~!

their composition is not the result of action by the school

district or if nothing practicable can be done to integrate them.

Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 26, 91 S.Ct. at 1281. A school district

also cannot be required to rearrange its attendance boundaries

each year to ensure a particular racial balance in the schools.

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424 , 96

S.Ct. 2697 (1976); Horton v.

LJ supra.

1 A. The Remaining One Race

1 j Formerly Dual System

The Original Plaintiffs begin their argument with conclusory

allegations regarding the number of black students in HISD attend

ing 90% minority schools and the number of one race black schools

in the HISD. (Brief, p. 26). The Original Plaintiffs then claim

that the HISD argued that white flight was the cause of the

"continuing existence of previous patterns of racial segregation"

in the HISD. (Brief, p. 26). From these premises, the Original

Plaintiffs argue that the HISD has not done all it can reasonably

do to reduce the number of one race schools.

First, the Original Plaintiffs reference no portion of the

Record to support their allegation that the HISD made such a white

flight argument. There is no such reference because no such

argument was made by the HISD. In fact, Mr. Billy Reagan, General

Superintendent, testified at length that the present composition

of the HISD was due in large part, not to white flight, but to

differences in birth rates. (1978 Tr. , pp. 37 , 207-215). While

the Original Plaintiffs might like the Record to reflect that HISD

-19-

case.made such a white flight argument, that is simply not the

The District Court, likewise, did not "adopt" this view.

Second, the Original Plaintiffs' arguments regarding the

numbers of minority students in one race schools is neither

relevant nor helpful in discussing the issues. In citing con-

clusory figures to bolster their total lack of evidence before the

District Court, the Original Plaintiffs ignore the hundreds of

pages of testimony and many exhibits which explain the composition

of HISD's schools and why some of them remain one race.

The District Court specifically found that the "one race

schools remaining in the HISD are not vestiges of the dual sys

tem." (R. No. 818, p. 30) . This finding is supported by the

Record. The testimony of Mr. John Eaton, Assistant Superintendent

for Administrative Services, traced in great detail the historical

evolution of Houston housing patterns, in several cases beginning

in the 1830's. (Tr., pp. 488-505). His testimony delineated a

long history of certain heavy concentrations of black and Mexican-

American residents within HISD and the City of Houston. A review

of that testimony, given in conjunction with Exhibit 34, substan

tiates that the former black schools (under the dual system) which

have remained predominantly black are located in virtually all

black areas which have become much larger and that the schools

which have changed from predominantly white to predominantly black

are located in areas of the HISD which have had a change in

housing patterns.

The HISD also presented this evidence in the form of maps

(Ex. 35-50) and school profiles (Ex. Nos. 54 a-d, 55 and 56)

-20-

prepared by Mr. Lon Wheeler, Executive Director of Pupil Transfer.

The maps depict the changes in housing and attendance patterns

which have occurred in the HISD since 1968-69 (Tr., pp. 520-550).

The school profiles furnish a detailed history of attendance at

each school by ethnicity, indicate whether the court projections

of 1970 were met and why, and explain the reasons each school is

one race or integrated. (Tr. , pp. 571-790; Ex. Nos. 54 a-d, 55,

and 56).

All of the 21 schools cited by the Original Plaintiffs as

being all black schools since 1960 are explained by the evidence

presented by the HISD. Fourteen of those schools, Dunbar, Easter,

Fairchild, Grimes, Highland Heights, Rhodes, Sanderson, Wesley,

Key, Ryan, E. 0. Smith, Kashmere, Worthing and Yates, were rezoned

or paired in 1970 and were projected to be desegregated on a

bi-racial basis. 317 F.Supp. at 528 , 529; 434 F.2d at 1148.

Eight of the schools, Blackshear, Clinton Park, Douglass,

Langston, Reynolds, Sunnyside, and Whidby, were projected by this

Court to remain virtually all black. 434 F.2d at 1148.

testimony of Messrs. Eaton and Wheeler establishes that

all of the 21 schools questioned by the Original Plaintiffs are

now located in all black areas of the City. (Tr. , pp. 571-790;

Ex. Nos. 54a, 54b, 54c, 54d). The present racial makeup of these

schools, then, is not the result of -the former dual system, but is

due to the concentration of the black population in certain areas

of the HISD. The testimony of Messrs. Eaton and Wheeler explains

that many of the remaining one race black schools were at one time

integrated or projected to be integrated, but all are now one race

-21-

because of housing patterns. (Tr. , pp. 571-790; Ex. Nos. 54 a-d,

55, and 56).

The District Court specifically found that HISD did every

thing practical to insure that students attended their assigned

schools. (R. No. 818, p. 27). The pairings simply did not work

because the anglo students (and many Hispanics) went to private

schools, moved to other districts, or simply did not go to school.

(Tr., pp. 1456, 1457, 1976; R. No. 818, p. 25).

Dr. Barton Smith, a professor of economics at the University

of Houston, also testified concerning his study of the changes in

the geographic distribution of the black and Hispanic population

within the HISD. (Tr., pp. 1135-1397). His study (HISD Ex. No.

70) and testimony corroborates Messrs. Eaton and Wheeler's tes

timony. Among Dr. Smith's conclusions were the following:

Clearly most areas within the Houston Independent School

District are now at least partially integrated due to

significant improvements in minority access to housing

throughout the district . . .

. . . areas of Black and Hispanic concentration appear

to cross with a major north-south Black corridor and and

east-west Hispanic corridor that intersects approxi

mately at the CBD [central business district] . This

means that many schools are apt to have significantly

less than 90% Blacks or Hispanics, but over 90% minori

ties (both Black and Hispanic) . . . traditional minori

ty areas appear to be becoming more concentrated and

consolidated. The latter phenomenon means that simply

because of the demographic changes that are occurring

more minority dominated (one race) schools may emerge

■ while at the same time all White/ Non-Hispanic schools

are gradually disappearing completely. (Ex. No. 70, pp.

25-27). ^

Mr. Eaton also testified that there was no factor that contained

any racial or ethnic group in any area of the HISD. (Tr., p. 497).

-22-

of this evidence was in no way contradicted or questioned

by any party. The Original Plaintiffs introduced no evidence at

the 1979 Hearing. In fact, the Original Plaintiffs did not even

attempt to challenge these facts in their Brief to this Court.

Instead, they attempt to obfuscate the issues by misstating the

HISD position.

Since the remaining one race schools are not vestiges of the

former dual system, there is no legal requirement for further

actions with respect to those schools. Swann, supra; Horton v.

Lawrence County Board of Education, supra.

B. The HISD Has Taken All Practicable Steps to Deseareaate the

Schools -------------2-------

Even if the District Court had found that some of the re

maining one race schools in the HISD were vestiges of the former

dual system, it also found that further actions to eliminate some

or all of the one race schools would not be practicable. The

Original Plaintiffs' complaint, however, is that all the

techniques mentioned in Swann have not been utilized in HISD and

that the reasons for not utilizing them are inadequate. The

Original Plaintiffs' factual assumptions and assertions, however,

as well as their legal analysis, are simply incorrect.

First, there is no requirement in Swann that all of the

techniques discussed in the case be utilized in any particular

case. Practicable and realistic steps must be taken. Davis v.

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S. 33, 91

S.Ct. 1289 (1971). As this Court stated in upholding the deter

mination that Atlanta had become a unitary school district:

-23-

It would blink reality and authority, however, to hold

the Atlanta School System to be nonunitary because

further racial integration is theoretically possible and

we expressly decline to do so.

Calhoun v̂ _ Cook, 525 F.2d 1203 (5th Cir. 1973) .

Second, as was previously stated, the utilization of the

various techniques discussed in Swann, and now proposed by the

Plaintiffs, has, in fact, occurred and has been

considered on several other occasions. The first occasion was

during the development of the 1970 Court Order. The initial plan

proposed by the Original Plaintiffs was one which would have

attempted to place a set ratio of white students in each of the

schools and would have required massive cross-town busing. This

plan was rejected by the District Court. Ross v. Eckels, 317 F.

Supp. 512 (S.D. Tex. 1970). (See pp. 515 and 516 for the District

Court's discussion of the practical problems of this approach.)

This Court also rejected the Original Plaintiffs' proposal and

ordered the pairing of 24 elementary schools. This Court

implicitly determined that these pairings, along with a geographic

capacity plan at the secondary level, which still left 15

virtually all black elementary schools and many one-race white

schools, were the only practicable additions to the District

Court's implementation of an equi-distant zoning plan. Ross v.

Eckels, 434 F.2d 1140 (5th Cir. 1970) (See pp. 1147-48).

Due in large part to the rapid changes in residential

patterns which occurred after this Court's 1970 decision, the

P^itings of the 24 elementary schools in 1971 resulted largely in

the pairing of minority students. (Tr., pp. 1456, 1456, 1976).

-24-

The pairings did not significantly reduce the amount of racial

isolation in the HISD. Accordingly, in 1975, the HISD established

a task force of community and school people to examine possible

alternatives to the pairings and to examine other means of

increasing integration. This task force spent many hours studying

various possibilities. The task force was given a review of the

various techniques of desegregation - specifically including

Pa-f r-f / both contiguous and non—contiguous, and clustering — by

Mr. Kelly Frels, one of the HISD's attorneys. (Tr., p. 1741; HTA,

Exhibit 12) . Other cities were visited and many other plans

studied. (R. No. 361). Mr. Billy Reagan, who instituted the task

force in late 1974, related that:

. . . after the task force started functioning in

November that sometime in mid-December Mr. Frels did

present the task force a detailed briefing on alter

natives and the way the alternatives would have to

function. And those alternatives included additional

pairing, additional zoning, and the different types of

remedies that were available that could be submitted to

the ̂ Court as an alternative . . . the task force did

deliberate on a number of issues, and their recom

mendations reflect that they deliberated on a number of

alternatives. And I do know that they did visit, I

guess, eight or ten other school systems in the country,

Atlanta, Memphis, I believe, San Francisco, Chicago,

Cleveland, and the school systems - large metropolitan

school systems or metropolitan areas that had either

undergone or were attempting to undergo some sort of

desegregation plan. (Tr., p. 1741).

After all of these actions were taken, it was determined that

the magnet school concept had the promise of being the most

successful and beneficial. A hearing was held before the District

Court in 1975 concerning this proposal, but, for whatever reason,

the Original Plaintiffs and their counsel, Mr. Weldon Berry, did

not attend that hearing. (Another attorney attended for a short

-25-

time and informed the Court that the Original Plaintiffs did not

oppose the plan). After the hearing, the District Court approved

the depairing of the 24 schools and the implementation of the

Magnet School Plan. (R. No. 371).

The use of the techniques mentioned in Swann was again

considered by the District Court in its Order of July 17, 1981.

The Original Plaintiffs presented no evidence whatsoever to rebut

the HISD's presentation and offered no proposed plan or any

further practicable steps which could be undertaken. The District

correctly analyzed the possible use of the Swann techniques

and, because of their impracticability, rejected them.

While the Original Plaintiffs highlight the fact that 70% of

the black students attend 90% minority schools, they themselves

show that the number of 90% black schools has decreased since

1969-70 from 66 to 55 and the percentage of black students attend

ing 90% black schools has decreased from 70% to 56%. (Brief,

pp. 19, 20). This progress has occurred in spite of the fact that

the percentages of black and Hispanic students attending the HISD

has increased dramatically since 1969-70. In 1969-70, the anglo

percentage was approximately 53% (1978 Ex. No. 6) , and for the

1981-82 school year, the percentage of anglo or other students in

the HISD is .only 26 percent. (See Appendix "A").

The Original Plaintiffs contend that the District Court did

not make specific findings regarding the practicability of other

desegregation techniques (Brief, p. 26). Apparently they did not

read pages 20 through 32 of the District Court's June 17, 1981

Order, wherein the Court explains in great detail why further

-26-

court intervention would be impracticable. Those findings are

supported by the voluminous amounts of uncontroverted evidence

submitted by the HISD.

%

In its findings, the District Court first stated that the

demographic makeup of the HISD has changed substantially since the

implementation of the 1970 Court Order and that the number of one

race schools has been reduced considerably since that time. The

Court went on to cite testimony from various witnesses regarding

the problems associated with the suggestions of pairing or other

similar possibilities. For example, Mr. Billy R. Reagan testified

in the 1979 hearing that pairing of schools had previously been

tried and had failed. (Tr., pp. 1773-74). "Knowing what I know",

Mr. Reagan said, " [to advise the Court to] to create a pairing

situation, I would consider myself to be guilty of malpractice in

education... I think that folly would prove totally disastrous.

I think you would have the same results that you had in our first

experiment with pairing." (Tr., pp. 1772-1774). Mr. Joseph

/ Superintendent for Area Administration, also so testified.

(Tr., pp. 1456, 1457).

The housing pattern maps (Ex. Nos. 35-50) show and the

District Court found that, because of the natural integration

which has occurred in many areas of the HISD (R. No. 818, p. 24),

the schools which would need to be paired are those on the extreme

western and eastern ends of the HISD (i.e. , some of the schools

depicted on the time and distance studies). Otherwise, naturally

integrated schools would be disturbed. The need for and

desirability of not disturbing desegregated schools has been

-27-

recognized by the courts. United States v. Board of School

Commissioners, 506 F.Supp. 657 (N.D. Ind. 1979) aff'd in part, 637

F• 2d 1011 (7th Circ. 1980); Tasby v. Wright, 520 F.Supp. 683 , 705

(N.D. Tex. 1981). The United States' witness, Dr. Gary Orfield,

testified that already desegregated schools should generally not

be disturbed. (Tr. , p. 2245) . He even went on to assert his

belief that "pairing adjacent schools is a very misguided policy."

(Tr., p. 2256) .

The Original Plaintiffs also contend that no time and dis

tance studies were undertaken. As with many of their arguments,

this is erroneous. At the September 29, 1978, hearing, several

specific examples of the time and distance of representative runs

throughout the HISD were analyzed and explained. (1978 Ex.

Nos. 21-26A; 1978 Tr. , pp. 86-99). These representative studies

show, as the District Court found, that the travel time between

those areas in the central and east ends of the HISD and the west

end of the HISD is considerable.

Mr. Reagan also testified that "due to the fantastic increase

in congestion in the city, that we are extending our time about 15

to 17 minutes per [bus] route per year." (1978 Tr. , p. 99). He

went on to state that "transportation is the number one concern of

the parent in terms of the time and the distance" and that "our

number one complaint about our magnet program, and also our M to

M... is transportation." (1978 Tr., p. 91). Since this testimony

and these exhibits are damaging to their case, the Original

Plaintiffs have valiantly tried to ignore them. They cannot,

-28-

however, be ignored, and they support the District Court's

findings.

Citing the testimony of Dr. Gary Orfield, a witness for the

United States, the Original Plaintiffs allege that there was

"ample credible evidence" that other desegregation tools could

work. (Brief, pp. 28, 29). Dr. Orfield, however, based his bald

assertion that "more could be accomplished" in HISD on an

admittedly incomplete and cursory review of pupil enrollment

statistics. He admitted that he had not fully studied the HISD's

case and was in no position to propose a plan for the HISD (Tr. ,

p. 2300, 2360, 2377). He admitted that his comparison of several

other districts utilizing magnet schools with the HISD was not

relevant to the HISD's situation. (Tr., p. 2380). He admitted

that it was impossible to desegregate all of the HISD schools to a

level he would consider adequate. (Tr., p. 2310, 2320). He

admitted that he did not know the pupil assignment requirements of

the HISD and stated that "You [HISD] may have a freedom of choice

plan for all I know." (Tr., p. 2372). Dr. Orfield admitted that

the comparative study he utilized to claim that HISD's

desegregation efforts were not successful was not a comprehensive

study and included many school districts with dramatically

different demographics and problems than the HISD. (Tr.,

pp. 2376-2382). In short, Dr. Orfield's testimony was, in the

words of one of the court appointed counsel for the children in

the HISD, like that of "the man that was passing the funeral. He

didn't know the deceased, but decided to stop and say a few words

anyway." (Tr., p. 2257).

-29-

Dr. Orfield's testimony gave no support for the development

of any mandatory pairing or other such plan. It was based on an

incomplete review of numbers and reflects an academician's theo

retical hope and desire for greater racial mixing of students. A

review of his testimony makes it eminently clear that Dr. Orfield

has a personal desire to mix students, whether or not it is

legally necessary or practicable and with no regard for the

educational consequences. Problems of implementation and the

possibility of resegregation apparently do not concern him. In

summary, his testimony does not support the Original Plaintiffs'

argument that more can be done. Even if Dr. Orfield's ideas

concerning his optimum desegregation levels - 50% white and 50%

minority - were attempted, the impact on the HISD would be

negligible, if not harmful. (Ex. No. 114).

The Original Plaintiffs seek to bolster the paucity of

evidence supporting their position by referring to a "study" done

by Mark Smylie of Vanderbilt University (Brief, p. 29) . The

Original Plaintiffs did not see fit to produce this person as a

witness at trial and subject him to cross examination, and this

belated attempt to introduce evidence should be ignored. Even a

cursory review of the "study", however, shows it to be an invalid

exercise. The study asserts that the implementation year of the

KISD's desegregation plan (1970) was 1980. Given such a funda

mental error in the premise of the "study", any "conclusions" made

by the study are incorrect and irrelevant.

The Original Plaintiffs also argue that concern over white

flight is not a valid reason for not pursuing their desired, but

-30-

unspecified, mandatory plan of mixing of students. Once again,

the Original Plaintiffs do not correctly state either the law or

the HISD's position. This Court has, of course, held that while

concern over white flight cannot be used to avoid desegregation,

consideration of ways to minimize white boycotts and of the

problem of resegregation are valid factors to consider when trying

to analyze various acceptable alternatives. Stout v . Jefferson

County Board of Education, 537 F.2d 800 (5th Cir. 1976).

In the case sub judice the District Court specifically found

that the use of other techniques, such as non-contiguous pairing,

would be counterproductive to desegregation efforts. (R. No. 818,

pp. 23-27). The HISD presented significant evidence concerning

this very real problem. (Tr., p. 977, 1457,. 1716, 1771-1779,

1976 , 1977 , 2852-2854; Ex. No. 70) . Instead of analyzing the

HISD s case correctly or making any evidentiary presentation, the

Original Plaintiffs sat mute at the 1979 hearings and now seek to

make a case by citing a plethora of platitudes which have no

bearing on the HISD's situation.

The Atlanta case is very similar to this one. In Atlanta a

plan was approved by this Court and the school system declared

unitary in spite of the fact that many of the techniques of Swann

had not been used. This Court stated:

Appellants^ urge that existing precedent will not allow

us to affirm this adjudication of unitary status to a

school district which has never utilized noncontinuous

pairing, has never bussed white children into pre

dominant black schools and in which over 60% of its

schools are all— or substantially all— black. These

contentions appear to be supported by substantial

precedent. However, for today and in Atlanta, the

unique features of this district distinguish every prior

-31-

school case pronouncement. . . . The district court also

found that Atlanta's remaining one-race schools are the

product of its preponderant majority of black pupils

rather than a vestige of past segregation. These

findings are not clearly erroneous. The aim of the

Fourteenth Amendment guarantee of equal protection on

which this litigation is based is to assure that state

supported educational opportunity is afforded without

regard to race; it is not to achieve racial integration

in public schools. (Citations omitted.) Conditions in

most school districts have frequently caused courts to

treat these aims as identical. In Atlanta, where white

students now comprise a small minority and black citi

zens can control school policy, administration and

staffing, they no longer are. See Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburq Board of Education (Part V) , 402 uTs-: T “at

122, 91 S.Ct. 1267 at 1279, 28 L.Ed.2d 554 at 570

(1971). Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F.2d 717,719 (5th Cir. 1975). ~ ----

In approving a desegregation plan which allowed many one

race schools to remain, an Alabama district court found that

the one race schools were located "deep in black residential

areas." Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, 377

F.Supp. 1123 , 1132 (M.D. Ala. 1974), aff'd, 511 F.2d 1374

(5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 423 U.S. 986 , 96 S.Ct. 394

(1975). Since the schools continued to exist without any

discriminatory actions by the school district, the plan was

approved. The court found that the one race schools could

not be practically and workably desegregated. The court

emphasized that the system as a_ whole is to be examined to

determine whether it is unitary - "individual schools are not

looked to for that purpose." 377 F.Supp. at 1138. The Carr

court went on to find that the six indicia of a unitary

school district - faculty, staff, transportation, extracur

ricular activities, facilities, and student body — were met.

-32-

It is, then, not surprising that in their Brief the

Orig'inal Plaintiffs completely ignored the issue of

educational opportunities in the HISD. Since access to equal

educational opportunities was at the heart of Brown I, the

HISD feels the issue is of major importance. The Original

Plaintiffs apparently do not. The Original Plaintiffs'

counsel, Mr. Weldon Berry, clearly enunciated their lack of

concern about the quality of education several times during

the 1979 hearing. At one point, Mr. Berry alluded to the

fact that if the HISD had somehow "properly" mixed students,

the District Court would not have to listen to "the avalanche

of statistical data regarding the quality of your educational

program." (Tr., p. 2099). In response to this observation,

Judge Robert O'Conor stated: "This Court is interested in

the quality of education." (Tr., p. 2099).

Ift its Order, the District Court found that the academic

achievement of- HISD students had greatly improved "due to the

importance the District attaches to providing equal access to

quality education." (R. No. 818, p. 30) . The evidence

presented by the HISD proves this point. Mr. Reagan

testified at length concerning the implementation of the

Basic Skills Program (1978 Tr. , p. 65; Tr., p. 1802), the

formation of Operation Fail Safe (Tr., pp. 1828-1834; HISD

Ex. Nos. 86-88), the monitoring programs to measure student

achievement (1978 Tr. , pp. 51-56; Tr. , pp. 1900-1910; HISD

Ex. Nos. 99-101) , expenditures per pupil at various schools

(Tr., pp. 1785-87; Childrens' Ex. Nos. 1 and 2), diagnostic

-33-

reading programs (Tr. , p. 1807), efforts to increase student

attendance (Tr., pp. 1808-1820; HISD Ex. No. 83 and 84), the

Schools Facility Improvement Program, a $300 million dollar

effort (1978 Tr. , pp. 99-158; Tr., pp. 1720-1730), evaluation

of faculty members, (Tr., pp. 1870-1880; Ex. Nos. 92 and 93),

achievement score improvements (Ex. 103), the development of

fundamental schools (Tr., pp. 1940-1942), and socioeconomic

factors affecting achievement (Tr., p. 1914).

Mr. Larry Marshall, Deputy Superintendent for

Alternative Education, testified at length concerning various

educational components which have been developed for all

student and specifically for minority students. (Tr., p.

1498-1605). Ms. Faye Bryant, Assistant Superintendent for

Magnet Schools, testified about their development and their

educational components. (Tr., pp. 942-1134). Mr. Angle

testified about the implementation of the Second Mile Plan

designed to stabilize faculties at schools with high turnover

rates, and about the factors which have led to the HISD's

reaching unitary status. (Tr., pp. 1398-1497).

While the Original Plaintiffs evince no interest in the

educational quality of the HISD's programs, it has been held

that remedial educational programs may be ordered by the

courts as part of a desegregation plan in order to ' help

remedy the past vestiges of segregation and to provide equal

educational opportunities. Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S.

267, 97 S.Ct. 2749 (1977); Plaquemines Parish School Board v.

United States, 415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969). In the case sub

-34-

judice, the District Court has not had to order the HISD to

develop these various programs. The HISD has undertaken them

voluntarily in an effort to assure equal educational

opportunities for all students.

A recent law review article by a prominent black law

professor, Derrick Bell, is instructive of the need to

consider the quality of education. Professor Bell notes that

the usual remedies in major school cases have not guaranteed

black children a better education than in pre-Brown days. He

goes on to observe:

This approach to the implementation of Brown, however,

has become increasingly ineffective; indeed, it has in

some cases been educationally destructive. A preferable

method is to focus on obtaining real educational effec

tiveness which may entail the improvement of presently

desegregated schools. . . .

. . . But successful magnet schools may provide a lesson

that effective schools for blacks must be a primary goal

rather than a secondary result of integration. . . .

If the decision [Brown] . . . is to remain viable, those

who rely on it must exhibit the dynamic awareness of all

the legal and political considerations that influenced

those who wrote it.

Bell, Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest - Conver

gence Dilemma, 93 Harv. L. Rev. 518, 530-533 (1980).

The development of a quality integrated educational

program has been achieved in the HISD, a large, urban school

district, in spite of the fact that the demographics have

changed dramatically, in spite of the high mobility rate of

students, in spite of those who would dissect the district

along racial lines, and in spite of all the outside forces

which mitigate against such an achievement. The

-35-

accomplishments of the HISD have been made without prodding

by the courts because of a real commitment to providing a

quality education available to all students and to doing all

that is practicable to provide an integrated environment.

Silent for almost ten years, the Original Plaintiffs, armed

with no evidence, ask this Court to cavalierly ignore the

facts of the case, the work of the HISD, and the

practicalities of the situation in order to make a futile and

counterproductive attempt at the forced mixing of students.

The Constitution does not require such futile and damaging

efforts and neither should this Court.

III.

THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT IN DENYING THE APPELLANTS'

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO AMEND AND TO ADD ADDITIONAL PARTIES

The Original Plaintiffs have several complaints regarding the

District Court's denial of their Motion for Leave to Amend their

Complaint to add additional parties. As with their analysis of

the unitary status issue, the Original Plaintiffs once again

incorrectly analyze the law and seek to divert attention from

their own lack of diligence.

The Original Plaintiffs initially make several general

statements regarding their belated motion. The Original

Plaintiffs' reference to the language of Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S.

178, 83 S.Ct. 227 (1962), on page 34 of their Brief, is misleading

inappropriate. The Original Plaintiffs' attempt to convince

this Court that their failure to timely seek leave to file an

-36-

Amended Complaint is a mere "technicality" or "misstep" is pure

sophistry designed to bolster an untenable position.

The Original Plaintiffs' assertion, in footnote 7, that

Calhoun v\ Cook, supra, 522 F.2d 717 (5th Cir. 1975), stands for

the proposition that it would be error to declare the HISD unitary

if an interdistrict case was pending, is incorrect. In Calhoun,

this Court made no such finding, but merely stated that final