Harris v. Moon Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1997

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harris v. Moon Jurisdictional Statement, 1997. 4b3cfb6a-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/12850d0c-e586-4fe9-b0f6-bed49b592bea/harris-v-moon-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

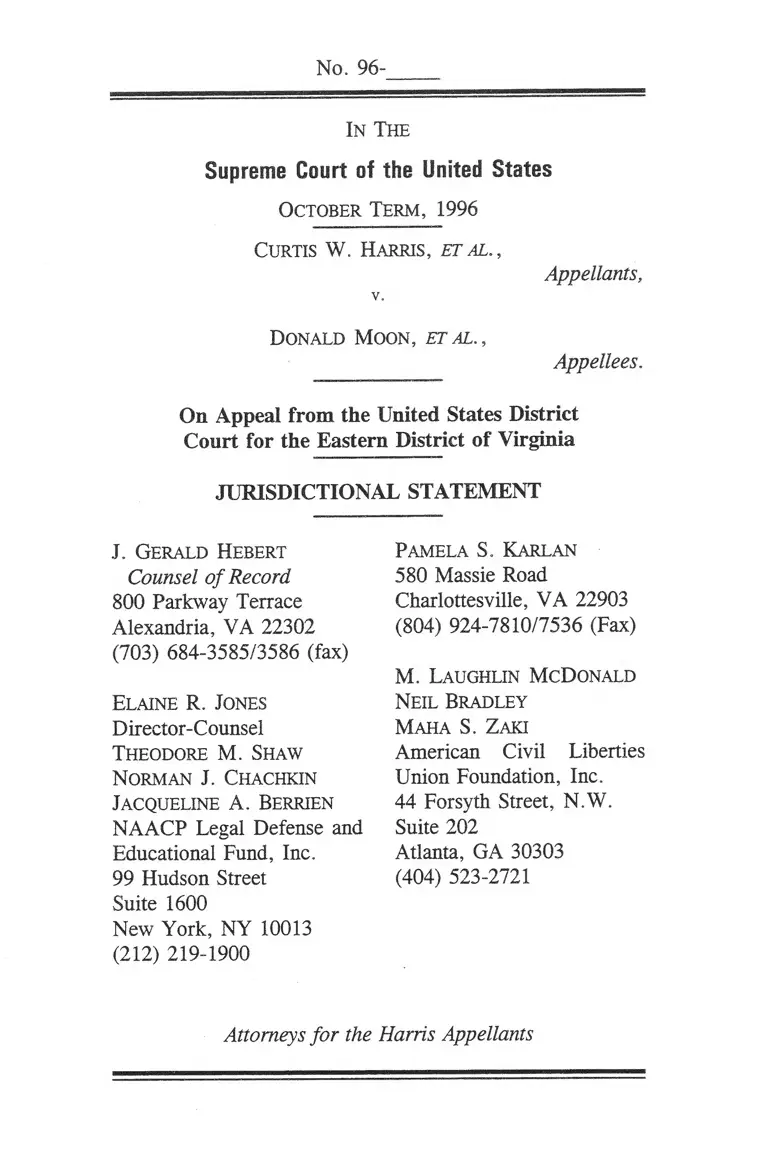

No. 96-

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1996

Curtis W. Harris, etal .,

Appellants,

V.

Donald Moon, etal .,

Appellees.

O n Appeal from the United States District

C ourt for the Eastern District of Virginia

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

J. Gerald Hebert

Counsel o f Record

800 Parkway Terrace

Alexandria, VA 22302

(703) 684-3585/3586 (fax)

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Jacqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Pamela S. Karlan

580 Massie Road

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(804) 924-7810/7536 (Fax)

M. Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Maha S. Zaki

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

Attorneys fo r the Harris Appellants

1

Q u e s t io n s P r e s e n t e d

1. Did the district court err in subjecting Virginia’s

creation of a single majority-black congressional district to

strict scrutiny?

2. Did the district court misunderstand this Court’s

test for determining if race is the predominant motivation

behind a reapportionment plan, when it ignored evidence that

the configuration of the Third Congressional District was the

product of Virginia’s actual "traditional districting princi

ples," namely (a) partisan considerations; (b) incumbency

protection; and (c) the Commonwealth’s unique and long

standing policy of splitting the Tidewater area among several

congressional districts?

3. Assuming that strict scrutiny was required, did the

district court misinterpret this Court’s analysis in Bush v.

Vera, 116 S.Ct. 1941 (1996), and Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S.Ct.

1894 (1996), when it found that the Third Congressional

District was not narrowly tailored?

4. Did the district court misunderstand the third

prong of the test announced by this Court in Thornburg v.

Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986), when it found no legally

significant racial bloc voting within the Third Congressional

District by relying on evidence of black electoral success (a)

in majority-black districts or (b) based on votes cast by white

voters in other parts of the Commonwealth?

5. Did the district court ignore the Commonwealth’s

contemporaneous strong basis in evidence for concluding that

the Voting Rights Act would require creation of a majority-

black congressional district?

11

P a r t ie s

The following were actual parties in the court below:

Donald Moon

Robert Smith

Plaintiffs;

M. Bruce Meadows, in his official capacity as Secre

tary of the State Board of Elections

Defendant;

Curtis W. Harris

Jayne W. Barnard

Jean Patterson Boone

Raymond H. Boone

Willie J. Dell

Henry C. Garrard, Sr.

Walter J. Kenney, Sr.

Melvin R. Simpson

Gerald T. Zerkin

Defendant-Intervenors.

I l l

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s

Page

Questions Presented ........................................................... i

Parties in the Court Below ............................................... ii

Table of Contents ................................ iii

Table of Authorities .......................................................... iv

Opinion Below ................................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................... 2

Statutory Provisions .................... 2

Statement of the Case ............................................ .. 2

The Questions Presented Are Substantial . . . . . . . . 12

I. Race was not the predominant factor in

the creation and configuration of the

Third District ............................................... 15

A. The Commonwealth’s section 5 submission

submission provides no evidence of racial

predominance ............................................... 15

B. The Commonwealth’s concern to avoid retro

gression in amending the 1991 plan provides

no evidence of racial predominance in the

initial adoption of the plan ...................................... 16

C. Race was only one of a constellation of

factors in the creation of the Third District . . . 18

IV

II. The Third District satisfies even strict scrutiny

because it is an appropriate response to Virginia’s

obligations under section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act ......................................... 24

A. Virginia had a strong basis in evidence for

believing there was legally significant white

bloc voting within the area where it located

the Third D is tr ic t ................................ 26

B. The Third District satisfies this Court’s

requirement that a remedial district be

located where the potential section 2

violation is found . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Conclusion . . . . ............................................ 30

Appendix ........................................................... A-l

V

T a b l e o f A u t h o r it ie s

Pages

Cases

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976) .................. 15

Brown v. Saunders, 159 Va. 28 ( 1 9 3 2 ) ............ 19,21

Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct. 1941 (1996) . 12,13,18,26,29,30

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55 (1980) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

City of Petersburg v. United States, 354 F.

Supp. 1021 (D.D.C. 1972), a ff’d, 410

U.S. 962 (1973) . ................................... .. .................... 6

City of Richmond v. United States, 422

U.S. 358 (1975) 6

Collins v. City of Norfolk, 883 F.2d 1232

(4th Cir. 1989), cert, denied, 498 U.S.

938 (1990) 6

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986) . . . . . . . . 18

First Virginia Bank v. Commonwealth, 212

Va. 654 (1972) .2 0

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1 9 7 3 ).................. 10

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345 (E.D.

N.C. 1984), a ff’d, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) . . . . . . . . . 27

Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528 (1 9 6 5 ) .................. 7

VI

Harris v. City of Hopewell, No. 82-0036-R

(E.D. Va. Jan. 5, 1983) ............................................... . 7

Jamerson v. Womack, 244 Va. 506 (1992) . .4,8,21-22,24

Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983) . . . 3,19

McDaniels v. Mehfoud, 702 F. Supp. 588

(E.D. Va. 1988) .............. ............... .. .......................... 6

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1995) . . . 12,18

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts

v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Reno v. Bossier Parish School Bd.,

65 U.S.L.W . 4308 (May 12, 1997) ............... 15,25

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) . . . . . 10,12,13,22

Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S.Ct.

1894 (1996) ................................. 12,13,16,24,26,27,28,29

State Corporation Comm’n v. Camp, 333

F. Supp. 847 (E.D. Va. 1971) ....................................20

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986) . . 4,25

United States v. City of Newport News, Civ.

No. 4-94CV155 (E.D. Va. Nov. 4, 1994) . . . . . . . 7

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964) ........................ 19

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

U.S. Const, amend XIV ..................... .. ............................. 2

V ll

28 U.S.C. § 1253 ............................................ 2

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 2

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ............................................ 2,4,12,25

Voting Rights Act of 1965, § 5

42 U.S.C. § 1973c ................................... .. 2,15,16

Va. Const. Art. II, § 6 ....................... ....................... ... . 21

1991 Va. Acts of Assembly, Special

Session II, Ch. 6 .......................... ....................... .. 2

1993 Va. Acts of Assembly, Ch. 983 ............................. 2

Other Authorities

Congressional Quarterly’s Politics in

America 1994, (P. Duncan ed. 1994) ................. 11

Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi,

Expressive Harms, "Bizarre Districts, " and

Voting Rights: Evaluation Election-District

Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92

Mich. L. Rev. 483 (1993) .................... ....................... 11

Peter Schuck, The Thickest Thicket: Partisan

Gerrymandering and Judicial Regulation o f

Politics, 87 Colum. L. Rev. 1325 (1987) . . . . . . . 10

Virginia Senate Committee on Privileges

and Elections, Resolution No. 1

(Feb. 22, 1991) .................................................. 4-6,19

1984-1985 Op. Atty Gen. Va. 128 (Oct.

4, 1984) ............................................................. .. 20

No. 96-

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term , 1996

Curtis W. Harris, etal .,

Appellants,

V.

Donald Moon, etal .,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

O p in io n B e l o w

The February 7, 1997, opinion of the three-judge district

court is contained in the Appendix to the Jurisdictional

Statement filed in No. 96-1779, Meadows v. Moon1 [hereaf

ter "Moon J.S. App."], at pages 3-33; it is reported at 952 F.

Supp. 1141 (E.D. Va. 1997), and is also available on LEXIS

at 1997 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 1560. The district court’s order

dated February 7, 1997, granting declaratory and injunctive

relief is contained in the Moon J.S. App. at pages 1-2.

1 M. Bruce Meadows is the Secretary o f the Virginia State

Board of Elections. He was sued in his official capacity. The

appellants in this appeal are a group of private citizens who live

within the challenged Third Congressional District. They participated

as defendant-intervenors in the litigation below.

2

Ju r is d ic t io n

The district court entered judgment on February 7,

1997, See Moon J.S. App. at 1-2. Appellants filed their

Notice of Appeal to this Court on March 7, 1997. That

notice is contained in the Appendix to this Jurisdictional

Statement at pages A-l to A-2 [hereafter Harris J.S. A pp."].

On May 1, 1997, Chief Justice Rehnquist granted appellants’

request for an extension of time to and including May 30,

1997, to file their Jurisdictional Statement. No. A-767, This

Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1253.

C o n s t it u t io n a l a n d St a t u t o r y

P r o v is io n s In v o l v e d

This case involves the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, which is reprinted in Moon J.S.

App. at 38; sections 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973 and 1973c, which are

reprinted in Moon J.S. App. at 40, 53-55; and two Virginia

statutes — 1991 Va. Acts of Assembly, Special Session II,

Ch. 6, and 1993 Va. Acts of Assembly, Ch. 983, which are

reprinted in Moon J.S. App. at 60-78.

St a t e m e n t o f t h e C a s e

This case involves a constitutional challenge to Vir

ginia’s 1991 congressional apportionment.2 The plaintiffs

2 The plan enacted in 1991 was the subject of "technical"

amendments in 1992 and 1993 intended to "reduce the number of split

precincts for localities and to conform the lines to new local precincts

and new local and state legislative election district lines." Joint

Exhibits at 1691 [hereafter "Jt. Exh."]. Most of these changes were

"initiated by local requests," connected with the ease of electoral

3

(appellees in this Court) are two voters who live within the

Third Congressional District. They challenged the plan as an

unconstitutional racial gerrymander.

According to the 1990 census, Virginia’s total population

was 6,187,358, of whom 1,162,994 (18.8%) were black.

Most of the Commonwealth’s black residents (59.17%) lived

in majority-black census blocks; nearly one quarter (24.29%)

lived in census blocks that were more than 90% black. By

contrast, more than one third of Virginia’s non-black resi

dents (34.31%) lived in a census block that did not contain

a single African American. See Declaration of William S.

Cooper f t 8,9 (Attachment 22 to Defendant-Intervenors’

Brief in Opposition to Motion for Summary Judgment).

The 1990 census resulted in Virginia receiving one

additional House seat, bringing the size of its congressional

delegation to eleven. Thus, Virginia had the duty not simply

to readjust boundary lines between districts to respond to

population shifts, but actually to create at least one complete

ly new congressional district, thereby necessarily altering

many of the Commonwealth’s other districts as well.

The 1991 apportionment took place under four condi

tions that had not obtained in prior reapportionment cycles.

First, this Court’s intervening decision in Karcher v. Dag

gett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983), required near-absolute population

equality among districts. This requirement would inevitably

force the Commonwealth to relax any policy of trying to

avoid splitting political subdivisions.3 Second, Congress’

administration, see id. at 1715.

Indeed, the population deviations in Virginia’s 1981 apportion

ment plan — which had fewer subdivision splits than its 1991 plan —

were far larger than the deviations in the New Jersey congressional

4

intervening amendment of section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, and this Court’s decision in

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986), meant that even

an apportionment plan that was not purposefully discriminato

ry or retrogressive might nonetheless violate federal law if it

resulted in a dilution of the voting strength of a geographical

ly compact, politically cohesive group of black voters. As a

matter both of the Supremacy Clause and of positive state

law, Virginia had an obligation to avoid violating amended

section 2. See Jamerson v. Womack, 244 Va. 506, 511

(1992). Third, Virginia’s 1991 redistricting would be the

first in a generation where one political party (the Demo

crats) controlled both the General Assembly and the gover

norship, thus offering an opportunity for largely uncon

strained political gerrymandering. Fourth, computer technol

ogy and more finely honed census data allowed for far finer

line drawing — with attendant boundary irregularities — than

had been possible in 1980 or before. See Trial Tr. at 326-28

[hereafter "Tr."].

Before beginning the reapportionment process, the

Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections adopted a

resolution ("Resolution No. 1"), setting out five "criteria"

and four "policy considerations" that redistricting plans ought

to achieve. Jt. Exh. 1. The five criteria were mandatory,

while the four policy "considerations" were simply that —

factors the assembly should weigh in the redistricting process

to the extent they did not interfere with the criteria. See

Jamerson, 244 Va. at 514 (explaining, as a matter of state

law, the difference between constitutionally compelled

criteria and policy considerations).

The first criterion was "[ejqual [representation," by

apportionment that triggered Karcher’s requirement of heightened

scrutiny.

5

which the senate meant equal population for each district, ft.

Exh. 1. The second criterion was "[mjinority [representa

tion, which the senate defined to mean that " [d] istrict plans

shall not dilute minority voting strength and shall comply

with §§ 2 and 5 of the Voting Rights Act." Id. (emphasis

added). The third criterion was compactness, which was

defined in the following terms:

Districts shall be reasonably compact. Irregular

district shapes may be justified because the district

line follows a political subdivision boundary or

significant geographic feature.

Id. at 2. The fourth criterion was contiguity, and here the

senate provided that

Contiguity by water is acceptable to link territory

within a district in order to meet the other criteria

stated herein and provided that there is reasonable

opportunity for travel within the district.

Id. The final criterion was "[political [fairness"; it provid

ed that a districting plan was unacceptable if it had "the

purpose and effect of denying any group of persons who

share a common political association a fair opportunity to

participate in the political process." Id.

The four "policy considerations" were, first, that plans

should be drawn so as to avoid splitting political subdivisions

"to the extent practicable"; second, that consideration be

given "to preserving communities of interest"; third, that

precincts serve as the basic building block for districts when

it might be necessary to split political subdivisions; and

fourth that "existing districts and incumbency" might be

taken into account. Id.

6

At least during this century, Virginia had never had a

majority-black congressional district, and no black candidate

had been elected to Congress. In 1986, Bobby Scott — a

popular black state senator who represented a predominantly

white state senate district — had run for Congress as the

Democratic nominee from the First Congressional District,

but had lost, receiving less than 8 percent of the white votes

cast. See Moon J.S. App. at 84. In light of the Common

wealth’s substantial (and geographically concentrated) black

population, the continuing prevalence of racial bloc voting,

pressure from a politically active black community, and the

Voting Rights Act’s requirements, there was widespread

agreement among all the participants in the redistricting

process that the Commonwealth should draw a majority-black

district if it could be done without sacrificing other important

state interests.

There was a strong contemporaneous basis in evidence

for this consensus. Members of the General Assembly were

aware of the facts surrounding the Bobby Scott congressional

campaign, as well as of the fact that Scott was the sole black

state legislator — in either house — to have been elected from

a majority-white jurisdiction at any time in the 1980’s. They

were aware as well of a series of judicial findings of racial

bloc voting in the Richmond, Petersburg, Tidewater, and

Southside regions stretching back to City o f Petersburg v.

United States, 354 F. Supp. 1021, 1025-26 (D.D.C. 1972),

a ff’d, 410 U.S. 962 (1973), and City o f Richmond v. United

States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975), and extending to the present

day, see, e.g., Collins v. City o f Norfolk, 883 F.2d 1232 (4th

Cir. 1989), cert, denied, 498 U.S. 938 (1990); McDaniels v.

Mehfoud, 702 F. Supp. 588 (E.D. Va. 1988) (Henrico

County). In addition, since the 1981 round of redistricting,

many communities within those regions had settled section 2

vote dilution lawsuits and had agreed to draw majority-black

districts. See, e.g., United States v. City o f Newport News,

7

Civ. No. 4-94CV155 (E.D. Va. Nov. 4, 1994) (consent

decree); Harris v. City o f Hopewell, No. 82-0036-R (E.D.

Va. Jan. 5, 1983). These settlements had been approved by

local federal courts and precleared by the Department of

Justice. Moreover, members were aware of the presence of

many of the other "Senate Report" factors on which courts

rely in assessing section 2 claims — such as Virginia’s long

history of official racial discrimination touching on the right

to vote, see, e.g., Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528

(1965); vast socioeconomic disparities between blacks and

whites; and the virtual inability of black candidates to get

elected in majority-white jurisdictions. In fact, Bobby Scott

and Governor L. Douglas Wilder were the only examples in

the twentieth century of black candidates successfully

winning major office from majority-white constituencies.

As experienced politicians, members of the General

Assembly were aware of the special circumstances and

advantages both men had enjoyed, including multiple white

candidates in their early elections, Tr. at 302; incumbency (in

Scott’s later race), see id. at 304; the presence of a coattail

effect from a popular running mate and predecessor (in

Wilder’s races for Lieutenant Governor and Governor,

respectively), Jt. Exh. 2065-69; unusually high black turnout,

PI. Exh. 22; Def. Exh. 1; Tr. 436-40; and the salience of

abortion as a wedge issue in Wilder’s gubernatorial race.

And political data before them showed that Wilder’s white

support was substantially weaker in the very areas where a

black district would be created. He got a lower percentage

of the vote in white precincts in the area where the Third

District was located than he got statewide. See Tr. at 434;

Def. Exh. 1. Even though Virginia did not face direct

pressure from the Department of Justice, see Moon J.S. App.

at 20-21, the General Assembly knew, at the time it drew the

1991 plan, that there was a substantial likelihood of a

successful section 2 lawsuit if it failed to draw a single

8

majority-black district in a state that was nearly 20% black.

Mary Spain, counsel to the Privileges and Elections Commit

tee, had specifically advised its members of the relevant

requirements under the Voting Rights Act, including the issue

of whether a majority-black district was required. See, e.g.,

Jt. Exh. 14-A, at 9-10; Tr. at 237-38.

Every plan considered on the floor of the General

Assembly — whether proposed by Democrats, Republicans,4

or nonpartisan groups - contained at least one majority-black

district. Moon J.S. App. at 6. All of the plans located their

majority-black district in roughly the same areas. The most

plausible plans extended from Richmond in the center of the

Commonwealth towards the Tidewater area — a distance of

approximately 100 miles and well within the traditional size

and extent of Virginia’s congressional and legislative dis

tricts. See Tr. at 339; Jamerson, 244 Va. at 509 (approving,

as compact within the meaning of Virginia’s constitutional

requirements, state senatorial districts that stretched 145 and

165 miles from west to east).

Some of the proposed majority-black districts were more

compact than the district ultimately chosen. See, e.g. Moon

J.S. App. at 80; Tr. at 347-48. But these districts had

unacceptable side effects. Some of the side effects are

familiar to this Court from other cases — for example, plans

placed more than one incumbent in the same district or

caused politically undesirable ripple effects in adjoining

districts, see, e.g., Tr. at 349, 351. These sorts of effects

are fairly typical of any plan that seeks to create a new

district, rather than simply to adjust the boundaries of pre

4 Evidence at trial suggests that one Republican-sponsored plan

created a majority-black district largely as cover for an attempt to

strip white Democratic incumbents of their constituencies. See Tr. at

224-27.

9

existing districts.

But there was one side effect that needs to be highlight

ed, for it makes Virginia unique among the states whose

reapportionment plans have come before this Court. Much

of Virginia’s economy depends on defense spending. In

particular, military installations and contractors are the

economic lifeblood of the Hampton Roads area. The

installations are located relatively close together. Someone

unfamiliar with the realities of congressional politics might

propose the creation of a geographically compact district

containing these various facilities. But Virginia has a

longstanding policy of taking precisely the opposite approach,

and dividing the Tidewater region among more than one

district. Virginia concluded, from long experience, that it

benefits the Commonwealth to locate military facilities in a

number of districts, thereby increasing the number of

representatives with bases in their districts who serve on

relevant House committees. For example, during public

hearings on the various proposed plans, Delegate Melvin

raised the concern that Norfolk Naval Shipyard and Newport

News Shipbuilding "not be in the same district," Jt. Exh. 14-

D at 27, and Delegate Cooper explained that it was "crucial"

to "mak[e] sure we have enough congressional voice" by

making sure "some shipyards are in the third" while other

facilities were in other districts, Id. at 39-40. See also Tr.

at 241-42; 251-52; 343-44; 346. Moreover, it was especially

important, given Congress’ direct control over military

spending, to preserve the seniority of various representatives

who served on Armed Forces Subcommittees, such as First

District Rep. Herb Bateman (R-Newport News); Second

District Rep. Owen Pickett (D-Virginia Beach); and Fourth

District Rep. Norman Sisisky (D-Petersburg).

Thus, in the very area of the state where there was a

heavy concentration of black voters that would necessarily be

10

one building block of any majority-black district, Virginia

had traditional districting principles that militated against a

mechanical quest for compactness. Put simply, fetishistic

adherence to abstract topological compactness would subordi

nate the Commonwealth’s "traditional districting principles."

Since Virginia conducted its reapportionment before this

Court’s decision in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993)

[Shaw I \ , and the existing case law suggested that compact

ness was in no sense a federal constitutional requirement,

see, e.g., Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 752 (1973),

the General Assembly had no reason to hesitate in trading off

some measure of geographic compactness in order to more

fully realize a constellation of other goals.

The tradeoff was a logical necessity since "[mjore

constraints [in the districting process] imply fewer possible

solutions," Peter Schuck, The Thickest Thicket: Partisan

Gerrymandering and Judicial Regulation o f Politics, 87

Colum. L. Rev. 1325, 1335 (1987). The General Assembly

split the city of Newport News, for example, because the city

was home to both a powerful incumbent (Bateman) and the

most likely candidate for the new seat (now-Rep. Bobby

Scott). See Tr. at 264. Other irregularities were the product

of desires to preserve Representative Sisisky’s base in

Petersburg and Representative Bliley’s base in Richmond.

See Tr. at 349, 359.

But the legislature did not sacrifice regularity of bound

aries more to create the Third District than it did for entirely

non-racial reasons in other regions of the Commonwealth.

In Northern Virginia, for example, the Democratic-controlled

assembly created a second new district. (It managed to

create a second open district by taking then-Representative

George Allen, a Republican who represented a district in the

center of the Commonwealth, out of his district and relocat

ing him into the district of a more senior Republican incum

11

bent. See Tr. at 359.) The new district, which was purpose

fully drawn to give the Democrats an opportunity to pick up

a seat, was extremely irregular, having a "shape that vaguely

recalls the human digestive tract." Congressional Quarterly’s

Politics in American 1994, at 1602 (P. Duncan ed. 1994).5

With respect to dispersion scores — one standard measure of

compactness - both the First and the Ninth Districts were

more irregular than the Third District. See Tr. at 133.

Similarly, the newly drawn Third Congressional District

was more compact than at least one district that had been

used in the 1981 reapportionment plan, despite the fact that

the 1981 plan as a whole was more compact than the 1991

plan.6 See Richard H. Pildes & Richard G. Niemi, Expres

sive Harms, "Bizarre Districts," and Voting Rights: Evalua

tion Election-District Appearances After Shaw v. Reno, 92

Mich. L. Rev. 483, 573 (1993). And in even earlier

apportionments, congressional districts had stretched from

Richmond to Williamsburg and from a Richmond suburb to

Hampton, Virginia Beach, and the Eastern Shore. See Tr. at

339, 376-77.

Nor did the 1991 plan either unnecessarily "pack" black

voters into the Third District or "maximize" black representa

tion. The plan left several pockets of black voters in

adjacent white districts, rather than extending the Third

District’s boundaries to encompass them. Tr. at 361. And

5 The shape of the Eleventh District is in no sense a product of

the shape of the Third District. The two districts are separated from

each other by parts of several other districts.

6 For example, in the post-1980 plan, the majority-white First

District was contiguous only across water; to get from one part of the

district to another on land required going through the Second District.

Tr. at 129.

12

it contained fewer black voters than many of the alternative

plans, including some plans that were arguably more com

pact. See Jt. Exh. 7, Attachment 15, at 14-15. Moreover,

although there were alternative plans that proposed two

majority-black districts, giving blacks rough proportionality

(18.18% of the districts with 18.8% of the population), or

proposed a heavily black "influence" district in addition to a

majority-black seat, see id ., the legislature squarely rejected

these suggestions in favor of a plan that better accommodated

the constellation of state interests involved in reapportion

ment.

The Questions Presented Are Substantial

This case raises important questions regarding how

courts should evaluate claims of overly race-conscious

redistricting under the equal protection clause. This Court’s

decisions in Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) [Shaw 7],

Miller v. Johnson, 115 S.Ct. 2475 (1995), Shawv. Hunt, 116

S.Ct. 1894 (1996) [Shaw II], and Bush v. Vera, 116 S.Ct.

1941 (1996), set out a two-stage process for analyzing such

claims. In the first stage, a plaintiff bears the burden of

showing that "race was the predominant factor" behind the

challenged plan. Miller, 115 S.Ct. at 2488. To show that

race was "predominant" requires showing that the legislature

"subordinated traditional race-neutral districting principles ...

to racial considerations." Id. In sum, the first stage is

comparative. It requires a court to ask whether race was

more important than other factors in the districting process.

In the second stage, which a court reaches only if the

plaintiff has met this burden, the question is whether the plan

"can be sustained nonetheless as narrowly tailored to serve a

compelling governmental interest." Id. at 2482. Among the

interests this Court has found compelling is compliance with

section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973. See

13

Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1969 (O’Connor, J., concurring); id. at

1975 (Stevens, J., joined by Ginsburg & Breyer, JJ.,

dissenting); id. at 2007 (Souter, J., joined by Ginsburg &

Breyer, JJ., dissenting). A state meets its burden of justify

ing the challenged district if it shows (1) that it had a "strong

basis in evidence" to believe that creation of a majority-black

district was necessary to comply with section 2, see, e.g.,

Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1960 (opinion of O ’Connor, J.); Shaw I,

509 U.S. at 656, and (2) that the district it drew both is

"reasonably" compact, see Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1961 (opinion

of O ’Connor, J.), and "substantially addresses the § 2

violation," Shaw II, 116 S.Ct. at 1907.

The district court botched both stages of this inquiry.

The district court never should have applied strict scrutiny in

the first place because Virginia did not subordinate its

traditional redistricting principles to race. In contrast to

other states whose plans have come before this Court,

Virginia has a well-established, hierarchically organized set

of redistricting principles. These principles take into account

Virginia’s distinctive interests and reflect a particularized

conception of "compactness" and "contiguity" that respects

the Commonwealth’s geography. But the district court

discarded Virginia’s actual principles in favor of inventing its

own notions of what compactness requires. Having misun

derstood both the historical practices and contemporary

realities, the district court got things exactly backward: it

failed to see that the Third District was the product of a

process in which incumbency, partisanship, and the desire to

preserve a large and influential Tidewater delegation all

played a more significant role than race.

Moreover, even if the district court had been correct in

its decision to apply strict scrutiny, its consideration of

whether the Third District was narrowly tailored to achieve

a compelling state interest was infected by a series of legal

14

and factual errors. With regard to the question whether the

state had reason to fear a a meritorious section 2 lawsuit, the

court completely misapplied the third Gingles factor, which

asks whether there is outcome-determinative white bloc

voting. Because the district court mangled the third prong of

Gingles, it failed to comprehend Virginia’s strong basis in

evidence for drawing a majority-black district.

As for narrow tailoring, here too the district court’s

opinion misapplied the relevant legal standard to a misunder

stood set of facts. In Shaw II, this Court explained that

narrow tailoring means that the "remedial district" should be

located in the region of a state where the potential section 2

violation can be shown. See 116 S.Ct. at 1906-07. The

Third District is located in precisely such a place. It

connects jurisdictions with persistent, well-known, and often

judicially recognized racial bloc voting. The district court’s

finding to the contrary rested entirely on its conclusion that

not every jurisdictions that had been sued was within the

Third District and that some jurisdictions were only partially

within the district. This conclusion fails to appreciate, first,

that the Third District is located entirely within areas where

repeated voting rights problems occurred, and second, that

the parts of the jurisdictions that were put within the Third

District were precisely the parts where the victims of the

section 2 violations lived.

Finally, even if the district court had reached the right

result for the wrong reasons, its decision still warrants full

consideration by this Court. The district court’s numerous

legal and factual errors threaten to infect the remedial

process, and this Court should correct them in order to make

sure both that the district court does not improperly intrude

on the Commonwealth’s districting prerogatives and that the

vital interests of Virginia’s black citizens are properly taken

into account.

15

I. Race was not the predominant factor in the

creation and configuration of the Third District

The district court’s conclusion that race predominated in

the creation of the Third District rests on three premises.

First, the court believed that the Commonwealth "admit[ted]

as much" in the course of obtaining section 5 preclearance.

Moon J.S. App. at 11. Second, the court saw direct evidence

of legislative intent in documents prepared in the course of

responding to changes proposed by the Governor and making

technical amendments to the 1991 plan. See Moon J.S. App.

at 12-13. Finally, the district court inferred from the shape

of the Third District that race had predominated over

traditional districting principles of compactness, keeping

political subdivisions intact, and respecting communities of

interest. See Moon J.S. App. at 14-18. None of these

premises stands up to careful examination.

A. The Commonwealth’s section 5 submission

provides no evidence of racial predominance

With regard to the district court’s reliance on statements

made by the Commonwealth during the preclearance process,

as this Court has made clear, the sole question to be an

swered in a section 5 preclearance proceeding is whether the

proposed change will have a racially discriminatory purpose

or effect. See Reno v. Bossier Parish School Bd., 65

U.S.L.W . 4308 (May 12, 1997); Beerv. United States, 425

U.S. 130, 141 (1976). Thus, the central focus of a section

5 inquiry is on the racial fairness of the plan, and not on

whether or how it responds to non-racial concerns. To

obtain preclearance, a state simply must focus on how its

plan fully respects black voting strength. Discussions of the

extent to which a plan serves a state’s interests in incumbent

protection, delegation seniority, boundary regularity, or any

other non-racial factor are relevant only to the extent that

16

they might explain why a state declined to draw a particular

majority-black district. Cf. Shaw II, 116 S.Ct. at 1904

(relying on the North Carolina General Assembly’s explana

tions for why it had not drawn a second majority black

district as persuasive evidence of a lack of discriminatory

purpose). Contrary to the district court’s view, it is not the

slightest bit " [s]trikin[g]," Moon J.S. App. at 11, that the

Commonwealth did not discuss its consideration of non-racial

factors in its redistricting process. Given the primacy of

legislative authority over redistricting, those factors were

frankly none of the Justice Department’s business, as long as

they did not prevent the Commonwealth from treating blacks

fairly. Since Virginia’s plan fully respected minority voting

strength, and it felt no pressure to "maximize" black voting

power, Moon J.S. App. at 20 — unlike Georgia or North

Carolina — the Commonwealth quite properly saw no need to

justify its choices with regard to other considerations.

B. The Commonwealth’s concern to avoid retro

gression in amending the 1991 plan provides

no evidence of racial predominance in the

initial adoption of the plan

Similarly, the district court’s reliance on statements

made after enactment of the 1991 plan to show a predominant

racial purpose misapprehends the evidence. Having received

preclearance for the 1991 plan, Virginia was under a section

5 obligation not to make any retrogressive changes. Thus,

it was entirely proper for the General Assembly to provide

that technical adjustment should not reduce the black popula

tion within the Third District. See Moon J.S. App. at 12.

That section 5 requires attention to race in making changes

logically says nothing about whether the plan being changed

was overly race-conscious. The internally inconsistent nature

of the district court’s analysis is illustrated by its treatment of

the 1992 and 1993 amendments. Here is what the district

17

court said:

Although a primary reason for adjusting the dis

tricting plan’s boundaries before the 1992 and 1994

elections was to reduce the number of split pre

cincts in the plan, the technical amendment resulted

in an increase in the Black percentage of the total

population to 64.08% and the Black percentage of

the voting age population to 61.24% in District 3.

Moon J.S. App. at 13 (emphases added). Even to call the

increased black percentage de minimis — let alone a purpose

ful attempt to enhance black voting strength — would

exaggerate its magnitude: the amendments increased the black

percentage of the voting-age population by 0.07 percent.

Given this infinitesmal effect, it makes no sense to say that

race played a predominant role in the 1992 and 1993 bound

ary changes. As as the district court itself recognized, the

primary purpose of the amendments was to avoid precinct

splits — precisely the state interest it later identifies as one

the plan seemed to subordinate. The change in black

percentage within the district was a byproduct, a "result," of

this entire legitimate purpose. Cf. Personnel Administrator

o f Massachusetts v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 279 (1979)

("discriminatory purpose" implies more than "awareness of

consequences"; it implies that an action was taken "at least

in part ‘because o f,’ not merely ‘in spite o f,’" its adverse

effects). If the 1992 and 1993 changes were explicable for

non-racial reasons, then as a matter of pure logic they cannot

provide probative evidence that the 1991 plan had a predomi

nantly racial motivation.

18

C. Race was only one of a constellation of fac

tors in the creation of the Third District

This Court has clearly recognized "the presumption of

good faith that must be accorded legislative enactments"

regarding the sensitive subject of redistricting, Miller, 115

S.Ct. at 2488. Of course, the Virginia General Assembly

was aware of the racial composition of the districts it drew

and it intended to create a majority-black district. But that

intention is not enough to trigger strict scrutiny. Rather,

strict scrutiny becomes appropriate only if the plaintiff proves

that "the legislature subordinated traditional race-neutral

districting principles, including but not limited to compact

ness, contiguity, respect for political subdivisions or commu

nities defined by actual shared interests, to racial consider

ations." Id.

The logical starting point for this inquiry, then, is to ask

what a state’s traditional districting practices in fact are,

since it is otherwise impossible to determine whether race

outweighed them. States "may avoid strict scrutiny by

retaining their own traditional districting principles," Vera,

116 S.Ct. at 1961 (emphasis added). The equal protection

clause provides no warrant for courts to decide, as a matter

of "gauzy sociological considerations," City o f Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 U.S. 55, 75 n.22 (1980) (plurality opinion),

what districting principles a state should have.7 Only once

a court properly comprehends a state’s actual practices is it

7 For example, if a state had a traditional, politically motivated

practice of splitting urban areas among districts in order to maximize

suburban influence, cf. Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986)

(Indiana repeatedly split Marion County among several districts in

each of which its voters formed a minority), then a court could infer

nothing about the predominance of race from the fact that a plan split

cities.

19

in the position to ask whether achievement of nonracial goals

was improperly sacrificed to create a majority-black district.

One of the most striking aspects of the district court’s

decision is its failure even to cite or mention, let alone

address, Virginia’s list of redistricting principles.

Unlike the other states whose plans have come before

this Court, Virginia had articulated a well-developed set of

redistricting principles. Resolution No. 1, which essentially

codified state constitutional law and practice extending in part

back to the 1930’s,8 not only listed a series of mandatory

"criteria" and subordinate, less binding "considerations," but

also defined what Virginia meant by such terms as "compact

ness" and "contiguity." See supra page 5. As a matter of

positive state law, Virginia viewed avoiding the dilution of

minority voting strength as of equal importance with three

other mandatory criteria — ensuring equal population, and

achieving reasonable compactness and contiguity. And it

thought that avoiding dilution was more important than five

considerations, including keeping political subdivisions intact,

8 Although Virginia adhered to a loose equal population standard

as long ago as Brown v. Saunders, 159 Va. 28 (1932), it had a long

and sorry history of racial discrimination touching the right to vote

that had only recently been repudiated. It would be cruelly perverse

to conclude that the fact that racial fairness is a relative latecomer to

the list makes it less a "traditional" districting principle.

Moreover, the relative elevation over time of equal population

to primacy of place on any list of redistricting criteria necessarily

subordinates other districting principles. Thus, it makes no sense to

compare the number of split political subdivisions today to those in

plans prior to 1983, and Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983),

let alone those that antedated Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1 (1964).

In Virginia, congressional districts can no longer be built exclusively

out of intact jurisdictions.

20

preserving communities of interest, and protecting incum

bents. Nothing in this Court’s jurisprudence undermines

Virginia’s full authority to adopt and rank the potential

districting principles as it did.

There is not even a scintilla of evidence in the record

from which a court could conclude that race predominated

over either equal representation or contiguity. As to the

former, the total percentage deviation of the 1991 plan was

40 persons, producing a total percentage deviation of 0.00%,

see Moon J.S. App. at 79. Race clearly did not predominate

over equal representation.

Nor, given Virginia’s longstanding definition of contigu

ity, did race subordinate contiguity. As a matter of Virginia

law, territory connected only by water is contiguous. See,

e.g . , State Corporation Comm’n v. Camp, 333 F.Supp. 847,

851 (E.D. Va. 1971) (holding that Norfolk is contiguous with

Hampton and observing that the General Assembly’s aware

ness of "the many rivers separating cities and counties in

Virginia is a foregone conclusion. They are, indeed, natural

geographic boundaries for cities and counties throughout

Virginia"); First Virginia Bank v. Commonwealth, 212 Va.

654, 655 (1972) (holding that the cities of Norfolk and

Portsmouth, which are separated by the Elizabeth River, are

contiguous); 1984-1985 Op. Atty Gen. Va. 128 (Oct. 4,

1984) (determining that "land areas which are separated only

by a body of water, with no territory of like kind between

them, may be considered ‘contiguous’" for purposes of

election laws regarding voter registration). In the past,

Virginia had drawn congressional districts contiguous only

over water. See Tr. at 339-40. Since all of Virginia’s

eleven congressional districts satisfy the state’s decades-old

definition of contiguity, any finding that contiguity was

subordinated to race would be clearly erroneous.

21

The only mandatory criteria that could even conceivably

have been compromised by the creation of the Third Con

gressional District is compactness. And here, too, the

district court’s analysis was remarkable for its glaring

disregard of Virginia’s traditional definition of compactness.

In Jamerson, the Supreme Court of Virginia made pellucidly

clear that compactnessness is not synonymous with preserva

tive of communities of interest or use of subdivision bound

aries:

[T]he use of the words "contiguous and compact,"

as joint modifiers of the word "territory" in Article

II, § 6,9 clearly limits their meaning as definitions

of spatial restrictions in the composition of electoral

districts. Indeed, when we were dealing with the

reapportionment policies of minimizing the splitting

of counties and cities and of recognizing existing

communities of interest in Brown v. Saunders, [159

Va. 28 (1932),] we did not mention them as a part

of this constitutional requirement, as the complain

ants contend. Instead, we simply referred to these

policies as a "custom" and as a consideration in

reapportionment of electoral districts.

244 Va. at 514 (internal citation omitted). But much of the

district court’s compactness analysis in this case focused on

the question of how many jurisdictions were split — precisely

the question that the Supreme Court of Virginia had held was

irrelevant to the compactness criterion. This Court has

9 Art. II, § 6 of the Virginia constitution provides, in pertinent

part, that "[e]very electoral district shall be composed of contiguous

and compact territory and shall be so constituted as to give, as nearly

as is practicable, representation in proportion to the population of the

district," and is the state constitutional foundation on which the "equal

representation" criterion is based.

22

squarely stated that compactness is not an independent

question of federal law, see Shaw I, 509 U.S. at 647, and

thus the district court had no justification for ignoring

Virginia’s 60 year-old practice of considering compactness

without regard to political subdivisions.

Considered in this way, the Third District is compact.

First, it is more compact both than other districts drawn in

the 1991 plan and than districts in previous apportionments.

Second, the Third Congressional District is entirely compara

ble to the shapes of the Fifteenth and Eighteenth State

Senatorial Districts, both of which the Supreme Court of

Virginia found to be sufficiently compact as a matter of state

law. See Jamerson, 244 Va. at 515, 518 (maps). It is

clearly erroneous to say that the Third District represents a

significant sacrifice of compactness.

But even if some compactness were sacrificed in the

redistricting process, the district court was simply wrong to

conclude that compactness was sacrificed for racial reasons.

First, the relationship between minority representation and

compactness was not a one-way street. Unlike the other

plans that have come before this Court, Virginia sacrificed

some degree of minority representation to compactness; after

all, the General Assembly declined to draw a second majori

ty-black district or a black "influence" district. It makes no

sense to say that racial considerations predominated when

they in fact gave way to a substantial degree. Second, there

was a prominent alternative plan — introduced by Senate

Majority Leader Hunter Andrews — that drew a majority-

black district that had smoother boundaries. See Moon J.S.

App. at 80. Thus, even if some compactness was somewhat

subordinated to something, the district court erred in thinking

it had been subordinated to race, when the testimony at trial

shows that partisanship and incumbent protection underlay

the General Assembly’s decision. See Tr. at 349-51.

23

The district court’s treatment of the state’s policy

"considerations" is equally flawed. A few examples will

suffice. The decision to split Richmond between a Demo

cratic and a Republican district, or to split Newport News to

preserve Republican incumbent Herb Bateman’s seat while

nonetheless providing for a new, predominantly Democratic

district from which Bobby Scott could run reflects "tradition

al districting principles," even if it does not comport with

some platonic, judge-derived theory of how districting should

be done. Moreover, it is utterly inconceivable that Virginia

would have drawn a majority-black district if it had been

forced to sacrifice Tidewater area incumbents or the Demo

crats’ aspiration of picking up a new seat in Northern

Virginia. Indeed, the General Assembly decisively rejected

plans that would have produced that result.

Similarly, the district court’s observation that the Third

District lacks a "common interest," Moon J.S. App. at 18,

because it encompasses multiple cities and stretches over

"200 road miles of territory," is belied by the fact that even

the plaintiffs’ witness testified that people in the Hampton

Roads area travel among jurisdictions daily, Tr. at 216; that

seven of Virginia’s other ten districts are larger in area,

Defendants’ Exhibit 1, at 5; and that the Virginia Supreme

Court concluded in 1992 that two state senatorial districts that

each joined parts of the Third Congressional District with

areas 145 and 165 miles away and each split cities and

counties nonetheless adequately considered preservation of

communities of interest. See Jamerson, 244 Va. at 509, 515-

16. The self-contradictory nature of the district court’s view

of communities of interest is captured in the final sentence of

its discussion: "This conclusion is reinforced by the fact that

approximately two-thirds of the population are black Ameri

cans and approximately one-third are white or other Ameri

cans." Moon J.S. App. at 18. What can this sentence

possibly mean, other to suggest that the district court thinks

24

that only monoracial districts or majority-white districts can

"harbor a common interest," id. — both sentiments utterly

repugnant to the Constitution?

Of course, Virginia traded off some compactness and

some preservation of political subdivision lines and precinct

boundaries in drawing its 1991 statewide plan. But it also

sacrificed some maximization of black voting strength, some

political fairness, and one incumbent. Every criterion and

policy consideration except equipopulosity gave way some

what. It is simply impossible to distill from this complex,

deeply political process a conclusion that race was the

predominant factor driving the redistricting engine. And it

is far more plausible to conclude that when compactness and

political subdivision lines were sacrificed, they yielded, as

they had repeatedly done in the past, to the Commonwealth’s

nonracial political and economic interests. In short, the

district court erred in assuming that "[r]ace was the criterion

that, in the State’s view, could not be compromised," Shaw

II, 116 S.Ct. at 1901; race was simply one factor among

many and it was in fact compromised.

II. The Third District satisfies even strict scrutiny

because it is an appropriate response to Virginia’s

obligations under section 2 of the Voting Rights Act

The district court’s holding that the Third District could

not survive strict scrutiny was premised on its belief that the

Commonwealth had no basis for fearing liability under

section 2 of the Voting Rights A ct.10 This conclusion, in

10 The district court’s offhanded observation that the Justice

Department’s entirely appropriate disavowal of any "maximization"

policy meant it also would not bring a section 2 lawsuit if the state

clearly diluted black voting strength, Moon J.S. App. at 20-21,

illustrates the district court’s misunderstanding of voting rights law.

25

turn, rested on the court’s extraordinary and unsupportable

conclusion that section 2 plaintiffs would be unable to satisfy

the third prong of the test set out by this Court in Thornburg

v. Gingles, which asks whether "the white majority votes

sufficiently as a bloc to enable it — in the absence of special

circumstances ... - usually to defeat the minority’s preferred

candidate." 478 U.S. at 51. (The district court essentially

assumed for the sake of argument that section 2 plaintiffs

would be able to meet the remaining requirements for

establishing liability. See Moon J.S. App. at 21-22.) In

addition, the district court thought that the Third District was

not narrowly tailored because it did not overlap with mathe

matical precision the precise areas where voting rights

violations had occurred. As to the question of white bloc

voting, the district court’s factual findings were both clearly

erroneous and tainted by a misunderstanding of the relevant

legal standard. As to the question of the precise placement

of the Third District, the district court simply misunderstood

this Court’s directives in Shaw II and Vera.

A. Virginia had a strong basis in evidence for

believing there was legally significant

white bloc voting within the area where

it located the Third District

This Court’s decisions make clear that a state may have

a "strong basis in evidence" for taking race-conscious action

without first being held liable under section 2. See Shaw II,

Both the text of section 5 and the Department’s standard policy

expressly leave open the possibility that the Department will sue under

section 2 to enjoin a practice it precleared under section 5, and the

Department has done precisely that several times in the past.

Moreover, this Court’s recent decision in Reno v. Bossier Parish, 65

U.S.L.W . 4308 (May 12, 1997), suggests that would have been the

correct course for the Department to take.

26

116 S.Ct. at 1905 (assuming, for the sake of argument that

North Carolina had a strong basis in evidence, although there

had been no judicial finding); Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1970

(O’Connor, J., concurring) (explaining why Texas had a

strong basis in evidence for race-conscious districting in the

Dallas area). In her concurrence in Vera, Justice O ’Connor

pointed to these factors in explaining why Texas had a strong

basis for concluding "that the creation of a majority-minority

district was appropriate": prior judicial findings of racial vote

dilution within the relevant region; testimony regarding racial

bloc voting; and examples of reasonably compact, plurality-

black districts. Id. Virginia satisfies this test.

The district court’s conclusion to the contrary regarding

the presence of bloc voting was the linchpin of its analysis.

That conclusion rests on four glaring mistakes. First, the

district court completely ignored undisputed evidence

showing that the vast majority of white voters had refused,

in election after election, to vote for any black candidates.

Both plaintiffs’ and defendants’ experts agreed that on

average less than fifteen percent of the white electorate

within the area in which the Third District was located were

willing to vote for black candidates.

Second, the district court mistakenly relied on black

electoral success within majority black districts to find an

absence of white bloc voting. For example, the court

emphasized that 9 of the 91 members of the Virginia House

of Delegates were black. Moon J.S. App. at 22 n.7. But

every one of those delegates was elected from a majority-

black constituency. In fact, each of them was elected from

a constituency that was at least 57 % black (and several other

majority-black districts elected white delegates). Success

within such majority-black districts quite simply provides no

evidence for concluding blacks can win in majority-white

districts. See Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345, 365-67

27

(E.D.N.C. 1984) (three-judge court) (explaining that black

electoral success from majority-black election districts did not

undermine the conclusion that black candidates would lose in

majority-white jurisdictions), a ff’d, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).

Third, the district court seemed to think that black

electoral success in other parts of the state was somehow

relevant to whether black voters within the Third District

could elect the candidates of their choice. Judge Widener,

for example, repeatedly pressed the defendant’s expert on

racial bloc voting to explain why she had not taken into

account the electoral success of a black mayoral candidate in

Roanoke — a city on the other side of the Blue Ridge

Mountains and at least a three-hour drive from any part of

the Third District. See Tr. at 438. Black electoral success

for local office hundreds of miles away is legally irrelevant

to the question whether black voters in the Tidewater and

Richmond areas can elect the congressional candidates of

their choice. Cf. Shaw II, 116 S.Ct. at 1906 (pointing out

that "[t]he vote dilution injuries suffered by ... persons [in

one part of a state] are not remedied by creating a safe

majority-black district somewhere else"). To the contrary,

there is a strong basis in evidence - consisting of judicial

findings in Richmond, Norfolk, and Henrico County and

consent judgments in Hopewell and Newport News — for

concluding the opposite: that bloc voting has prevented

blacks from electing their preferred candidates in local

elections.

Fourth, the district court exaggerated the significance of

Douglas Wilder’s statewide success and Bobby Scott’s

success at the state legislative level. These two men are in

fact the only blacks in this century to have won major state

or federal office from a majority-white constituency in

Virginia. The court failed entirely to take into account the

unusual circumstances that had allowed them to win, or the

28

undisputed fact that, in the area where the Third District is

located, neither man in fact could have won election to office

from a majority-white constituency. For example, roughly

three-quarters of white voters within the Third District

supported W ilder’s opponents in his races for governor and

lieutenant governor. See Def. Exh. 1. And even this low

level of support paints an atypically rosy picture: Wilder

received an unprecedented share of the white votes cast.

Finally, the court gave no weight at all to the most probative

piece of evidence in this regard -- the fact that Bobby Scott

himself had been unable to win election to Congress from a

majority-white district in the same general area as the Third

District, receiving only 8% of the white votes, far fewer than

white Democratic nominees received in the succeeding two

elections.

B. The Third District satisfies this Court’s

requirement that a remedial district be

located where the potential section 2

violation is found

In Shaw II, this Court explained that narrow tailoring

requires that a remedial district be drawn "coincident" with

the potential section 2 violation whose remediation serves as

the compelling state interest. 116 S.Ct. at 1906.

The district court committed serious legal and factual

error in applying this standard. It concluded that the Third

District "does not directly address the harm asserted,”

because some localities in which blacks experienced vote

dilution were not included within the district. Moon J.S.

App. at 21. That conclusion directly contradicts this Court’s

clear statement in Shaw II that the remedial siting require

ment "does not mean that a § 2 plaintiff has the right to be

placed in a majority-minority district once a violation of the

statute is shown. States retain broad discretion in drawing

29

districts to comply with the mandate of § 2." 116 S.Ct. at

1906 n.7. Moreover, the Court has also made clear that

states must have "leeway" about where exactly to place a

remedial district; they need not draw "the precise compact

district that a court would impose in a successful § 2 chal

lenge," but need only respect "their own traditional dis

tricting principles." Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1960 (opinion of

O ’Connor, J.) (emphasis added). Thus, the fact that some

black voters with potential section 2 claims are not included

in the Third District does not undermine the state’s narrow

tailoring.11

If one were to place a map of the places where credible

claims of vote dilution had been brought on top of a map of

the Third District, the overlap would be quite substantial.

Most of the land bridge tying these areas together consists of

intact counties such as Surry, Charles City, and New Kent.

The district court took exactly the wrong message from the

fact that only portions of five jurisdictions that had faced

meritorious section 2 lawsuits were included within the Third

District. Moon J.S. App. at 21. The parts of Newport

News, Henrico, Hopewell, Richmond, and Norfolk that were

included in the Third District were the places where the

victims of proven or recognized vote dilution lived. The

decision to split those jurisdictions was an integral part of

narrow tailoring, in precisely the same way that splitting

those jurisdictions into single-member districts for local

elections was narrow tailoring: such division was necessary

to remedy dilution through submergence.

11 To the contrary, the commonwealth’s refusal to stuff every

conceivable section 2 plaintiff into the Third District actually supports

the conclusion that the district is narrowly tailored, both because it

avoids unnecessary "packing" of black voters and because it allowed

the district to have more regular boundaries.

30

Put simply, Virginia had good reason to believe that

black voters in the Richmond and Tidewater areas could win

a section 2 challenge to the failure to draw a single majority-

black congressional district and it therefore drew such a

district while fulling respecting its "own traditional districting

principles," Vera, 116 S.Ct. at 1961 (emphasis added).

Conclusion

For the reasons stated above, the Court should note

probable jurisdiction of this appeal.

Respectfully submitted,

J. Gerald Hebert

Counsel o f Record

800 Parkway Terrace

Alexandria, VA 22302

(703) 684-3585/3586 (fax)

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Jacqueline A. Berrien

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Pamela S. Karlan

580 Massie Road

Charlottesville, VA 22903

(804) 924-7810/7536 (Fax)

M. Laughlin McDonald

Neil Bradley

Maha S. Zaki

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

Attorneys fo r Appellants

A p p e n d ix

Page A-l

Notice of Appeal, Dated March 7, 1997

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

RICHMOND DIVISION

DONALD MOON and ROBERT SMITH, )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

v. ) Civil No.

) 3:95CV942

M. BRUCE MEADOWS, )

)

Defendant, )

)

and )

)

CURTIS W. HARRIS; JAYNE W. )

BARNARD; JEAN PATTERSON BOONE; )

RAYMOND H. BOONE; WILLIE J. DELL; )

HENRY C. GARRARD, SR.; WALTER T. )

KENNEY, SR.; and GERALD T. ZERKIN, )

)

Defendant-Intervenors. )

___________ )

NOTICE OF APPEAL

NOTICE is hereby given that defendant-intervenors

Curtis W. Harris, Jayne W. Barnard, Jean Patterson Boone,

Raymond H. Boone, Willie J. Dell, Henry C. Garrard, Sr.,

Walter T. Kenney, Sr., Melvin R. Simpson, and Gerald T.

Zerkin, hereby appeal to the Supreme Court of the United

States pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1253 from the judgment and

Page A-2

order filed February 7, 1997, declaring the Third Congres

sional District in Virginia to be violative of the United States

Constitution and enjoining state officials in Virginia from

conducting any future elections

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

THEODORE M. SHAW

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JACQUELINE A.

BERRIEN

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educationa; Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, New York

10013

(212) 219-1900

PENDA HAIR

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 683-1300

[Certificate of

m that Congressional District.

Respectfully submitted,

__ _______ /s/

J. GERALD HEBERT

Attorney at Law

Virginia Bar No. 38432

800 Parkway Terrace

Alexandria, VA 22302

M. LAUGHLIN

McDo n a l d

NEIL BRADLEY

MAHA S. ZAKI

American Civil Liberties

Union Foundation, Inc.

44 Forsyth Street, N.W.

Suite 202

Atlanta, GA 30303

(404) 523-2721

PAMELA S. KARLAN

580 Massie Road

Charlottesville, VA 22093

(804) 924-7810

Service Omitted]