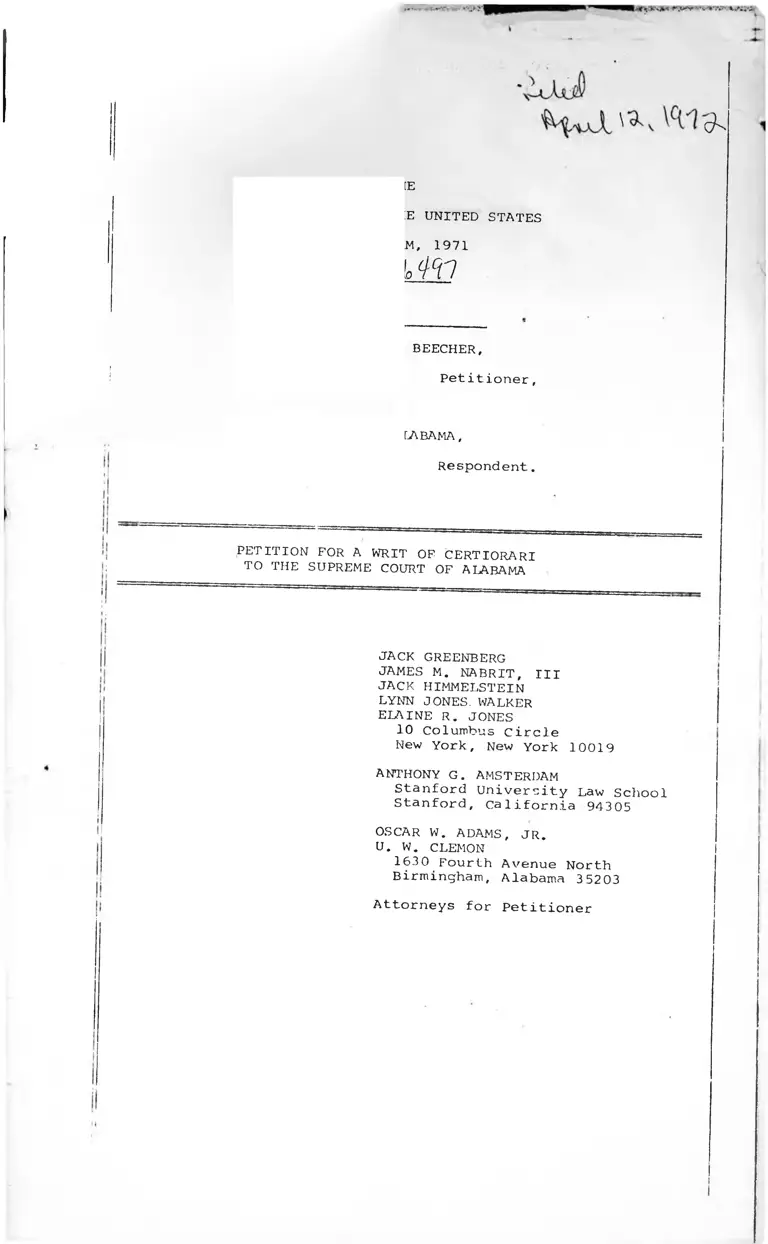

Beecher v. Alabama Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama

Public Court Documents

April 12, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Beecher v. Alabama Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Alabama, 1972. 3a75be24-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/128a84d8-d6b5-409d-87bf-a04a789b74f8/beecher-v-alabama-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-alabama. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

̂ cX

IN THE

SUPREME ’COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

NO. II- Ip M l

JOHNNY DANIEL BEECHER,

Petitioner,

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

JACK HIMMELSTEIN

LYNN JONES. WALKER

ELAINE R. JONES

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

OSCAR W. ADAMS, JR.

U. W. CLEMON

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Attorneys for Petitioner

INDEX

Opinion Below .................................

Jurisdiction ..................................

Questions Presented ...........................

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

Statement .................... ..........

A. Statement of the Circumstances Surrounding

Petitioner's confession ............. .........

B. Statement Respecting Petitioner's Witherspoon

Contention ...................................

How The Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

Belov/.......... '.....................................

A. The Confession Issues ........................

B. The Witherspoon Issue ........................

Reasons for Granting the Writ ........................

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted To Determine

Whether the Confession Used To Convict

Petitioner Was Obtained Under Inherently

Coercive Circumstances, In Violation Of

Kls Fourteenth Amendment Rights.............

A. On the Totality of the Circumstances

of This Case, Petitioner's Confession

Was Not Voluntary.......................

B. Petitioner's Confession Cannot Be

Sustained as Voluntary upon this

Record Because the Courts Belov/

Failed to Make An Adequate Inquiry

Concerning the Effects of the Dosage

of Morphine Administered to Petitioner...

II. Certiorari Should Be Granted To Determine

Whether An Indigent Capital Defendant's

Challenge Under Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 UoS. 510 (1968) To Selection Of His

Trial Jury can Be Rejected On The Basis

Of The Trial Judge's And Prosecutor's

Post-Trial Declarations That No Witherspoon

Error Occurred, Without Providing A Tran

script of The Voir Dire Or Showing That Such

A Transcript Cannot Be Provided...........

A. The Remand Hearing ...................

B. The Inadequacy Of The Record .........

C. The Right to a Transcript of the

Voir Dire.............................

Page

1

1

2

2

3

5

10

11

11

13

15

15

16

25

32

34

37

39

I

i

j

*

ii!

i

»

I

I

I

Conclusion 44

■ Tt-' • ■*'■-•** *.. fc.«7T ̂ ‘4A vr*s-. •-»- '■.•'■ . V'*■ ****¥<.'*'5 •-■•»•. • -,* */ . , w'i**'• *,» -• »,- *,•<'/ »- .. - • * **v,. •

TABLE OF CASES

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S. 143 (1944)............

Beecher v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 35 (1967)................

15,16,

Beecher v. State, __Ala.__, 256 So. 2d 154 (1971)......

Billingsley v. State, __Ala.__, 254 So. 2d 33(1971)....

Boulden v. Holman, 394 U.S. 478 (1969)..... ............

Boykin v. Alabama, 395 U.S. 238 (1969).................

Bram v. United States, 168 U.S. 532 (1879).............

Brown v. Commonwealth, 212 Va. 515, 184 S.E. 2d 786(1971)

Butler v. State, 285 Ala. 387, 232 So. 2d 631 (1970)...

Carnley v. Cochran, 369 U.S. 506 (1962)...............

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940)..............

Clewis v. Texas, 386 U.S. 707 (1967)..................

Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568 (1961)...........

Dannelly v. State, 254 So. 2d 434 (Ala. Ct. Crim. App.)

cert, denied, 254 .So. 2d 443 (Ala. 1971)...........

Darwin v. Connecticut, 391 U.S. 346 (1968)............

David v. State, 453 S.W. 2d 172 (Tex. Ct. Crim.App.

1970) ................. ........................

Davis v. Henderson, 330 F. Supp. 797 (W.D.La. 1971)....

Davis v. North Carolina, 384 U.S. 737 (1966)..........

Draper v. Washington, 372 U.S. 487 (1963).............

Duplessis v. Louisiana, 403 U.S. 946 (1971)...........

Edwards v. State, __Ala.__, 253 So. 2d 513 (1971).....

Entsminger v. Iowa, 386 U.S. 748 (1967)...............

Eskridge v. Washington State Board, 357 U.S. 214 (1958)

Evans v. State, 430 S.W. 2d 502(Tex.Ct.Crim.App. 1968).

Ex parte Bryan, 434 S. W. 2d 123 (Tex. Ct. Crim.App.

1968) ..........................................

Funicello v. New Jersey, 403 U.S. 948 (1971)..........

Gardner v. California, 393 U.S. 367 (1969)...'.........

Grider v. State, 468 S.W. 2d 393(Tex. Ct. Crim.App.

1971) .............................;.. ...........

Griffin v,. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956)...............

Hackathorn v. Decker, 438 F. 2d 1363 (5th Cir.1971) . . . .

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U.S. 503 (1963).............

Herron v. State, __Tenn.__, 456 S.W. 2d 873 (1970)....

In Re Anderson and Saterfield, 69 Cal. 2d 613, 73

Cal. Rptr. 21, 446 P. 2d 117 (1968)................

In Re Cameron, 67 Cal. Rptr. 529, __Cal. 2d __,

439 P. 2d 633 (1968) ................................

Jackson v. Beto, 428 F. 2d 1054 (5th Cir. 1970).......

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964).................

Jenkins v. Delaware, 395 U.S. 213 (1969)..............

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969).................

Joseph v. State, 442 S.W. 2d 123 (Tex. Ct. Crim. App.

1969) ..........................................

Page

16

3,5,

2 4 ;

40,43 '

34,40

14,32,:

33,38J39

24

35

37

36

I

39

18, 21

19

15,24

29

19,20

37

37

16,17,1

20,31 '

38,39^

41.42

38

33

42

38.42

37.40

37.42

37.41

38.42

37

42

37

17,18

37

35

24

37

24

20

42

37

31

11

I*.v.vw iw m s;t v *v <t' -ju."\ :x '\ ,v r r j i i .w v i • 'j v r q » i i 'T

r

Page

Ladetto v. Massachusetts, 403 U.S. 947 (1971) ........ 38

Ladetto v. Commonwealth,356 Mass. 541, 254 N.E. 2d 415

j (1969)..............................................

!| Lane v. Brown, 372 U.S. 477 (1963)....................

j! Lego v. Twomey, 30 L. ed. 2d 618 (1972)...............

;! Leyra v. Denno, 347 U.S. 556 (1954)...................

|l Liddell v. State, __ Ala.__, 251 So. 2d 601 (1971)

i! Logner v. North Carolina, 260 F. Supp. 970 (M.D. N.C.

[I 1966).................................... ..........

Lokos v. State, 284 Ala. 53, 221 So. 2d 689 (1969)....

jj Long v. District Court of Iowa, 385 U.S. 192 (1966)...

'! Lynum v. Illinois, 372 U.S. 528 (1963)................

, »

ij Marion v. Beto, 434 F. 2d 29 (5th Cir. 1971) cert.

denied, 402 U.S. 906 (1971)........................

| Mathis v. Alabama, 403 U.S. 948 (1971)................

j Mathis v. New Jersey, 403 U.S. 946 (1971).............

Mathis v. State, 283 Ala. 303, 216 So. 2d 286 (1968)...

| Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 U.S. 262 (1970)................

Ij Mayer v. City of Chicago, 30 L.Ed. 2d 372 (1971)......

i| Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966)...............

42

25,30,$ 1

21

33,34

37

39,42

15

I

41

13,32,33,37,41

43 i37 j

32,36 !

41,42

20

; Pate v. Holman, 341 F. 2d 764 (5th Cir. 1965).........

. Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375 (1966).................

i! Payne v. Arkansas, 356 U.S. 560 (1958)................

j| Payton v. United States, 222 F. 2d 794 (D.C. Cir. 1955) .

' People v. Floyd, 1 Cal. 2d 694, 82 Cal. Rptr. 608,

464 P. 2d 64 (1970)................................

Ij People v. Sears, 70 A.C. 485, 74 Ca] . Rptr. 872, 450

j P. 2d 248 (1969)....................................

I Pilkington v. State, 46 Ala. App. 716, 248 So. 2d 755

i (1971)...............................................

c Pinkney v. State, Cir. Ct. Palm Beach, Crim. No. 2490

Ij (July 17, 1971).....................................i I

•j Reck v. Pate, 367 U.S. 433 (1961).....................

Reddish v. State, 167 So. 2d 858 (Fla. 1964)..........

jj Reid v. State, 478 P. 2d 988 (Okla. Ct. Cr. App. 1970).

j1 Richardson v. State, 247 So. 2d 296 (Fla. 1971).......

ij Robinson v. Tennessee, 392 U.S. 666 (1968)............

ij Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534 (1961)...............

j Rouse v. State, 222 So. 2d 145 (Miss. 1969)...........

43

28

18, 21

17

35

35

33

37

15,16

24

37

37

19,23

19,30 ,j 34

37

i Seibold v. State, __Ala.__, 253 So. 2d 302 (1970).....

Sims v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 538 (1967)..................

Spencer v. Beto,398 F. 2d 500 (5th Cir. 1968).........

State v. Forcella and Funicello, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A.

2d 20 (1968)........................................

| State v. Graffam, 202 La. 869 (1943)..................

j State v. Hudson, 253 La. 992, 221 So. 2d 484 (1969)....

State v. Mathis, 52 N.J. 238, 245 A. 2d 20 (1968).....

State v. Pinkney, Cir. Ct. of Palm Beach, Fla.,

: i Crim. No. 2490 (July 9, 1971).......................

.j Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965)..................

') Swain v. State, 285 Ala. 387, 232 So. 2d 631 (1970)....i' ‘

I1 Tea v. State, 453 S. W. 2d 179 (Tex. Ct. Crim.App. 1970)

| Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293 (1963).................

ij Townsend v. Twomey/152 F. 2d 350 (7th Cir. 1972)......

37

17,19,

37,42

23

37

24

38

43

35

37

20,24,25,

30

37

li

i i i I

I

■ ■ . ■- ■' - - . .-J -. - . - '- ■* . '-r rV - m’'* * > - v

Page

United States ex rel. Weston v. Sigler, 308 F. 2d 946

(5th Cir. 1962).................................... 40,42

United States v. Robinson, 439 F. 2d 553 (D.C. Cir!l970) 24*

Wilson v. Florida, 403 U.S. 947 (1971).......... 3 8

Wilson v. State, 225 So. 2d 321 (Fla. 1969).!!!].’.*!!]]]] 38

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968)........ ]]]

2,4,10,i3,14,32,33,34,35

36,37,38,39,40,41,43

i Statutes:

Title 30, Ala. Code 1940 (Recompiled 1958), § 57

Title 15, Ala. Code 1940 (Recompiled 1958) § 382

Other Authorities:

Beaver, The Analgesic Effects of Morphine and Methadone,

8 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS 415 (Mav-June 1967)...........................................

B.BECKMAN, PHARMACOLOGY 226 (1961) ....!!!!!!!!!!!]]]]]]]

Comment, "Admissibility of Confessions and Denials Made

Under the Influence of Drugs," 52 N.W.L.Rev. 666,(1957)....................... .................. [

L. GOODMAN and A. GILMAN, THE PHARMACOLOGICAL BASIS OF

THERAPEUTICS 239-240 (3d Ed. 1965).................

A. GROLLMAN and E. GROLLMAN, PHARMACOLOGY AND THERA

PEUTICS (7th Ed. 1970)............................

J. LEWIS, AN INTRODUCTION TO PHARMACOLOGY, 392 (3rd*Ed! 1964)..............................

A. REYNOLDS and L. RANDALL, MORPHINE AND ALLIED DRUGS 21 (1957).................... .....................

Smith, .Subjective Effects of Heroin and Morphine’in’

Normal Subjects, 136 Journal of Pharmacology and

Experimental Therapeutics 47 (1962)................

T. SOLLMAN, A MANUAL OF PEJARMACOLOGY 293 (8th Ed]*i964)

2,32

1, 4

23

21

22

21

22

23

21,23

23

23

IV

i

' T ' N » . > . « < . » . T * r T - - » . - . - : s it... . d. tS*'.***--.- X 'UJ\,

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No.

w

Ii

JOHNNY DANIEL BEECHER,

Petitioner,

v .

STATE OF ALABAMA,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama, entered in this

cause on December 9, 1971, rehearing of which was denied on

January 13, 1972.

Opinion Below

The opinions of the Supreme Court of Alabama affirming

petitioner's murder conviction and death sentence, together

with the dissenting opinion of chief Justice Heflin joined by

Justice Lawson, are reported at __Ala. 256 So. 2d 154 (1972). !

They are set forth in the Appendix [hereinafter referred to j

as A.--], infra, pp. la-18a. j

|

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was entered

on December 9. 197!. and a motion for rehearrng was denied on

January 13. 1972. Pending filing and disposition of this petition

for writ of oertrorari, the Alabama Supreme Court on January 18.

1972. stayed execution of petitioner's death sentence.

I

'r i - . > w y * • » 9~*K*xr>*+ *»•*♦ > .• « 4 * .* ‘ . > ■ - ^ 5^- • * - ■ r ✓ .%•'> U 7 .V .5 ? K fc -r w * * , » r tA X P i* !'* * *< & ■ '< **^ 'jO T ¥ ^ ^ fV V ir \% .i^ p s U Br

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 j

i

U.S.C. § 1257(3), petitioner having asserted below and asserting

here deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the

United States.

Questions Presented

I* whether petitioner's confession was involuntary and its

introduction into evidence violated his rights under the Four-

j

teenth Amendment.

II* Whether petitioner's confession, following the adminis- i

tration of 1/2 grain of morphine, could properly be held voluntary

in the absenceof evidence that the drug exerted no influence on

petitioner's will.

III. Whether, following a remand to determine compliance

with Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 u.S. 510 (1968), the Alabama

Supreme Court erred in affirming this indigent petitioner's death:i

sentence upon a record containing only the prosecutor's and the !

trial judge's statement that no veniremen were excused for scruplies,

where the voir dire transcript was neither produced nor shown to j

be unavailable.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

____________INVOLVED

This case involves the Fifth, Sixth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the United States Constitution.

It further involves Title 30 , Ala. Code 1940 (Recompiled

1958), § 57:

On the trial for any offense which may

be punished capitally, or by imprisonment

in the penitentiary, it is a good cause of

challenge by the state that the person has

a fixed opinion against capital or penftentiary,

punishments, or thinks that a conviction should

not be had on circumstantial evidence; which

cause of challenge may be proved by the oath

of the person, or by other evidence.

- 2

STATEMENT

I

This case is here for a second time. Petitioner, an

indigent Black man, was originally, in September 1964, convicted !

and sentenced to death for the murder of a white woman This

«

Court reversed that conviction and sentence of death on the

ground that a confession introduced in evidence against petitioned

was "the product of gross coercion," there having been no "break j

an the stream of events" from petitioner's initial oral confessioiji

I

to his confession five days later while "still in pain, under thej

influence of drugs, and at the complete mercy of the prison j

hospital authorities." Beecher v. A labama, 389 U.S. 35, 38 (1967)| .

I*

The opinion sets forth the following facts based on petitioner's

testimony.

I

"The uncontradicted facts of the record are I

these. Tennessee police officers saw petitioner

as he fled into an open field and fired a bullet

into his right leg. He fell, and the local Chief \

of Police pressed a loaded gun to his face while

another officer pointed a rifle against the side

of his head. The Police Chief asked him whether

he had raped and killed a white woman. When he

said that he had not, the Chief called him a liar

and said, 'if you don't tell the truth I am going j

to kill you.’ The other officer then fired his

rifle next to the petitioner's ear, and the

petitioner immediately confessed. Later the same

day he received an injection to ease the pain in

his leg. He signed something the Chief of Police

described as 'extradition papers' after the officers

told him that it would be best . . . to sign the

papers ̂ before the gang of people came there and \

^itlod him. He was then taken by ambulance from

Tennessee to the Kilby Prison in Montgomery, Alabama.

By June 22, the petitioner's right leg, which was

later amputated, had become so swollen and his

wound so painful that he required an injection of

morphine every four hours. Less than an hour after1

one of these injections, two Alabama investigators

visited him in the prison hospital. The medical

assistant in charge told the petitioner to'cooperatd'

and, in the petitioner's presence, he asked the in-,

vestigators to tell him if petitioner did not 'tell

them what they wanted to know.' The medical assistant

then left the petitioner alone with the State's in

vestigators. In the course of a 90-minute'conversa-

tion, the investigators prepared two detailed state

ments similar to the confession the petitioner had I

given five days earlier at gunpoint in Tennessee.

Still in a 'kind of slumber* from his last morphine j

injection, feverish, and in intense pain, the peti- !

tioner signed the written confession thus prepared

for him." Beecher v. Alabama, 289 U.S. 35, 36-37 '

(1967) -3- ’ i

»• '■* , .-. » ... -:r -• •- V r ;-*i> . :#> •' a f - ..’• ‘

on January 26. 1968 petitioner was re-indicted by a

' JaCkS°n County-Alabama Grand Jury on one count of murder.(Trial

Record.in Transcript on Appeal before the Supreme Court of Alabama

[hereinafter cited as R. l.pp. 1-2.) petitioner was indigent

and counsel was appointed rrVir> trial ,PFujnvea. The trial occurred the following

February 4-5, 1969.

«

Petitioner's confession was again the major piece of

evidence upon which petitioner was convicted and sentenced j

to death in a brief jury trial.~

An automatic appeal pursuant to Ala. Code 1940 (Recompiled ! 1 9 5 8 ) . Tit. 15. § 382 (1) followed. m the Supremo Court of Ala- !

bama. petitioner was represented by appointed counsel. (R. 9 .) !

On October 7. 1971. that court 1) remanded the case to the trial |

court for hearing to determine the state of the record with regard!

to a claim arising under Witherspoon v . Illinois 391 u . s . 510 I( 1 9 6 8 ) , and 2) rejected each of petitioner's other federal consti-j

tutional claims. (A. la-16a.) After the hearing on remand, the j

Alabama Supreme Court on December .9, 1971 affirmed the conviction |

and sentence of death. (A. 17a-18a.) Petitioner's timely motion

for rehearing was denied on January 13, 1 9 7 2 .

unpagina ted ̂ in1 Record^J^Therea f ter a°Januaryk 2 7^1968 inthe°c^Sel#'

o?Up t i S ^ menta 1 ̂ xaminati on

z s s ^ i s - i f ~ : r s . a„di

for change of venue to Cherokee Tr C 10-2w T " m°ti0n

ttea]u^?nSCriPt reflects ^ than forty pages of testimony

~ 4 -

x*m *1 mt*

I

-W-- ■■ • -■ • *Wi*vn>*'+*mk.v+1e«*r V;«AH»

i, .... _.... . a ____ r

it!

I

i

i»

I j

A. Statement of the Circumstances Surrounding Petitioner's

Confession.

At the retrial, the prosecution sought to escape the

impact of this Court's earlier decision in Beecher I in two

ways. First, it presented the testimony of the Tennessee Police

Chief who took petitioner's initial confession. Second, it intro

duced into evidence,not petitioner's initial oral statement to

Ii

the Police Chief nor his written confession given five days later j

which this Court invalidated in Beecher I, but an intervening

statement made by petitioner to a Tennessee doctor. The facts

at the retrial were as follows: IjIOn the morning of June 15, 1964, petitioner, a 31-year-old |

Black convict previously convicted of rape and serving a sentence ;

at Camp Scotsboro near Hollywood, Alabama, escaped from a convict 1i

road gang. (R. 228-231.) The camp was located approximately 8/10's

of a mile from the home of Mrs. Martha Chisenall. (R. 231.) Mrs.

Chisenall's dead body was found by a police search party on June

16, between 9:30 and 10:00 a.m., some distance from her home.

(R. 235-236.) 1

Petitioner was captured on June 17 at approximately 5:00

a.m. in South Pittsburgh, Tennessee, by Tennessee police officers >

who had been alerted by Alabama authorities to be on the lookout

! for him in their vicinity. (R. 265-267.) A search party or "mob,"

to use the expression of South Pittsburgh Police Chief Burroughs,

had come up from Alabama and had been hunting for petitioner in

the border area most of the day; but they had returned to Alabama

prior to petitioner's capture, while the Tennesse Police continued

the search. (R. 267.) ;

i

5

Police Chief Burroughs first spotted petitioner walking on1 ■

| a railroad track. (R. 267.) Petitioner jumped from the track

j and fled into a field. (R. 268.) The Chief shouted to petitioner

I

, to halt and, when he did not, told one of his officers to shoot

I • «petitioner. (R. at 268.)

i' "So, I told this officer to shoot him,

stop him which I told them all not to

shoot to kill. We didn't know whether

it would be the right one or not. In

other words, I didn't want to shoot

somebody to stop them and maybe it was

some small crime a running . . . .

(R. 268.) •

The officer then fired his rifle at petitioner who fell to the

ground and was still (R. 268), his leg almost blown off. (R.276,I '

, 317). The officers approached him where he lay, the one with his

rifle, the Chief with drawn gun. (R. 268.) Petitioner was silent'

and motionless. (R. 268.)

I, Within the span of the next 60 minutes, petitioner is said

to have "confessed" his crime twice, once to Police Chief

Burroughs and once, shortly thereafter, to the Tennessee doctor

to whom the arresting officers took petitioner for emergency i

treatment before transporting him back to Alabama.

The evidence as to what happened in the field is now the

! | subject of conflicting testimony. At the retrial, petitioner

testified substantially as he had at the first trial: he was

cut down by a rifle bullet while running through the field (R. |

i289); he was in "extreme pain" with the "bone . . . out of the

leg" (R. 290); the Chief came over and said "This is the one

we are hunting. . . Why did you kill that white woman?"; the

Chief put his pistol on petitioner's nose, while the officer

who shot him had his rifle against petitioner's shoulder, fired

into the ground by petitioner's ear (R. 289), and, in petitioner's

'' words, "asked me did I believe that he would kill me." (R. 299.) i!i I| I :Petitioner further testified that he was scared, and that the I

!

Chief asked him:

6

III

• • *<\ \' v*v* **-*-■* "-i1 '»*

ji

"’Did you kill her?’ and I said, ’Yes, I killed her.’

. . . And he said, ‘How many times you raped her?'

and I said, 'Twice -- I raped her twice.'“

(R. 291.)

I

I

Police Chief Burroughs, however, now contradicted petitioner

testimony in some respects. He said that after he approached i

petitioner, found him still and observed no weapon in petitioner'^

, |

hands, the Chief stuck his gun back into his holster while the j

other officer kept his rifle out. The two of them eased peti- I

tioner up to be sure that he had no concealed weapons. (R. 268-

269, 309.) The officer, standing somewhat more than two or i

three feet from petitioner, did then fire his rifle into the jI

ground twice -- but only as a signal to summon the rest of the

search party. Nothing was said to petitioner, however, when

these shots were fired. (R. 309-310.) The Chief asked petitioner

his name and petitioner answered, "Johnny Beecher." (R. 269.) I

The Chief asked, "Are you the man they are hunting in Alabama?"

s

! to which petitioner replied with this full confession: "Yes, I

, am . . . i raped and killed this woman. I know I have to give

I

a life by taking one, but please don’t let that mob get me." i

(R. 269.) Petitioner"kept repeating,'Don't let the mob get me,'"'1

j and the Chief said, You are under arrest. I will put you under

arrest and it is my job to protect you and I will." (r . 269.) Ij

A truck was then driven into the field, and petitioner was put j

on the flat back and transported to the nearby hospital at

i‘ 3/ j

South Pittsburgh for treatment. (R. 269-270.) According to the, i

Chief, at no time did he or his officers threaten petitioner •

Il■ " i

2S Petitioner testified upon voir dire examination out of the

jury's presence that he was "slung up" on the truck by the

officers and that he had to hold on to a chain on the back of

it to keep from rolling off in transit. (R. 291.) He stated

that when he arrived at the hospital, the officers were "fixing

to throw . . .[him] off on the ground" until the people from the

hospital stopped them. (R. 291-292.) The Police Chief denied

that petitioner had to hold on to any chain to keep from rolling off the truck. (R. 307-308.)

7

-v *■ v;-.-'*v v * • - v . * » ’k-j r:?-.'* V*~

the Chief did not put his gun in petitioner's face and saw no

one else do so. (R. 269-270.)

Petitioner's confession in the field was not presented

! ito the jury, as the trial court explained, "because of the ruling 1l

of the United States Supreme Court." (R. 271.) Rather, it was

an ensuing statement, made within the hour to the physician who

treated petitioner at the local hospital, which the jury heard.

I

This physician, Doctor Headrick, testified on voir dire

ithat he first saw petitioner in the emergency room approximately

15 minutes after petitioner had been wounded on June 17. (R. 276,

279-) Petitioner "had a gunshot wound of the leg and the tibia

was shattered . . . ." (R. 276.) The leg "was practically shot

i

off and Beecher was experiencing great pain." (R. 317.) He was j

in a great deal of pain. (R. 279-280.) The doctor gave him iItwo shots of morphine, each 1/4 of a grain, one intravenously

|

and one muscularly, to ease his pain. (R. 278.) The doctor then ;

began to give petitioner "first aid" (R. 319), consisting of

cleansing, packing and wrapping the wound so that he could be

transported. (R. 276.) i

"[H]e was going to be transported to

Kilby Prison, that was the word that was

given to me. I was not to take him to the

operating room and to start to work on the

leg." (R. 281.)

During "most of [the] . . . conversation" when petitioner

made the incriminating statements to Dr. Headrick, only Dr.

Headrick and his nurse were with petitioner (R. 277); but accord

ing to the doctor, "[tjhere were policemen all over the place"

(R. 280), including in the hall and at the door" (R. 279); and

the doctor could "hear all sorts of voices as many policemen

were concerned." (R. 281.)

- 8 -

I

Dr. Headrick testified that he gave the petitioner food

because "he hadn't eaten in some time" (R. at 281), and water

and cigarettes. (R. 277.) He did not make any threats or

promises to petitioner and was not asked to question petitioner

by the police. (R. 277.) The doctor at first could not remember

if he asked petitioner any specific questions about Mrs.

Chisenall's murder before petitioner started telling him

(R. 277, 281), although he recalled asking petitioner "why did

he do it." (R. 281.) Testifying before the jury, he was clear:

"Q [by the prosecuting attorney]. Was a statement

you made -- did you -- you didn't ask him any

questions to get him to make the statement, did

you?"

A. As I remember I asked him why he did it.

Q. Prior to that time, did he make a statement

of what he did?

A. No, sir. " (R. 315.)

Petitioner then (as described by Dr. Headrick to the jury):

"started off by more or less telling me his life

history, the fact his mother had died when he was

young and his father left the family and he had

always had a hard time even existing as far as

food and what not was concerned. Then, he said

that he had seen this lady on her front porch

on several occasions . . . . He said he made up

his mind he was going to get some of that no

matter what it cost him and then he told me he

raped her three times . . . . He said he did

not want to kill her but they were in a little

cove or thicket and she wouldn't quit screaming.

He had to kill her because there were people

coming up the mountain." (R. 316.)

Concerning the effect of the morphine administered to peti

tioner, the doctor stated in response to the Court's inquiry that

"morphine will relieve pain and make a patient have a feeling of

well being," but that it wouldn't affect mental capacity "unless

you get a tremendous overdose where it suppresses respiration

- 9 -

• &*+sanv ss " -»nr*« ■.■■an’rys ■ sf: wv*.v',v-Murom* .. . ** '■<> ■/• ■ ";•>*»> 1 ' * '.< <•'■*'«■- *y/i

j| or ^kes them unconscious ." (R. 278.) In the doctor's opinion,

ji ^titioner knew "what he was talking about, " knew "the meaning"

jj of what he was saying and "realized it." (R. 278.) The dosage

of morphine was not large enough to completely relieve allI j

ji Petitioner's pain, particularly if petitioner moved. (R. 278-

'' 280.)

!i

Petitioner testified that the pain from the wound was

j, extreme, as "the bone was out of the leg" (R. 295), and he was

very afraid. (R. 294.) He could remember only receiving one

, shot. (R. 293.) The drug put him "at ease." "it kindly [sic]

>' made me feel like I wanted to love somebody, you know, took the

pain awaV and made me feel relaxed." (R. 296.) Petitioner could

j: n°t remember what he said or how he acted after receiving the

morphine. (R. 301-304.) He "didn't have control of [his].

| mind" after the injection. (R. 302.)* , i'!i The record is clear that petitioner was not offered an

attorney, advised by anyone of his right to have an attorney,

or told that he need not make any statement. (R. 295.) At some

point while at the hospital, apparently after being treated, !

i ' i

petitioner "signed to come back" to Alabama (R. 272, 294). He >

j

was returned to Kilby Prison by ambulance the same morning. .j

(R. 272, 291.)

l' |

j

ji B. Statement Respecting Petitioner's Witherspoon Contention. j

jBecause the voir dire examination of petitioner's jury

venire was not transcribed or made a part of the trial record

on the automatic appeal, the Supreme Court of Alabama remanded !

to the trial court, on October 7, 1971, noting "that the record

!

does not contain a transcript of the proceedings when the jury

|

- 1 0 -

;•* y

,.* ^r^yjy^^'firh. W fM *n* v ^ \ x -rjo ^ v w v / ^ v ^ u ^

venire was qualified.Therefore we are unable to determine whether 1

l

the jury which convicted Beecher was constitutionally selected." j

, (A- 10a*) 0n the remand,the trial court was directed to determine!

j whether any jurors were challenged because of their affirmative *

I :

I answers to a general question as to a fixed opinion against

. 5 capital punishment . . . ." (a . 11a )

ii i

The remand hearing was held on October 21, 1971, before the

trial court, the Circuit Court of Cherokee County, Alabama.

(TranscriPt of Remand Hearing [hereinafter cited as Remand Tr. ], '

ji P ‘ 6 *̂ Petitioner's original court-appointed counsel appeared

for him and asked for a continuance to allow petitioner to

contact counsel of his own choosing." (Remand Tr. 8-11.) The

II court denied the motion. (Remand Tr. 11.) Thereafter, testimony

'.was taken and proceedings were conducted as described at pp. 34-36,1

j'infra. !

11l HOW THE FEDERAL QUESTIONS WERE RAISED i

I _ AND DECIDED BET.OW 'r — --------------------- !

I, A. The Confession Issues:l!

Defense counsel objected at trial to the admission of

petitioner's statement. (R. 310-311, 315.) The trial judge over

ruled the objections, concluding that the statement was "voluntary .j "

’ | I

!■ Referring to this Court's earlier decision, he ruled:

"Their only purpose in making that decision

i; and the only decision they could legally make

j was whether or not at that time that confession

down at Kilby Prison when he was questioned by

, a State Investigator or Detective under the j

conditions he was questioned under was admissible.

They held it wasn't and then they made another I

statement which was not necessary about the i

decision about the breaking of the chain of

events and even if it were a part of the decision

which was substantial, now that there is contra

diction in the evidence as to what happened there I

at that time there their decision could very well j

different because they had a one sided case at that time." (R. 287.)

I think there is a great distinction between i

the confession that is contained [sic] in the

penitentiary by a State detective and a voluntary

- 11 -

!

■ \ r v • v «'-■ W - t v V * » * » * V > ‘wx- •--''.V, “ J ' , ' T V ' K V x V :

statement which is made by a man to a doctor without

questioning, without any association with the State

and without any showing that it was done at the

instigation of the State. . . ." (r . 3 H.)

in his brief on appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court, petitioner

again challenged the voluntariness of his confession:

The admission of this confession violated

the rights guaranteed to the defendant by the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

the United States Constitution, it violated

the holding in Beecher v. Alabama, 389 U.S. 35

U967)." (Defendant-Appellant‘s Brief on Appeal to the Alabama Supreme Court, pp. 16-17.)

The majority opinion of the Alabama Supreme Court first

considered whether the morphine administered to petitioner

immediately prior to his confession constituted a constitutionally

impermissible influence. it found:

• . . that the able trial judge correctly

ruled that the confession given by the defendant

•0^Jr* ^eadrick in the emergency room, considered independently, meets the test of voluntariness

subscribed to in this State, as well as that

proscribed [sic] by Federal constitutional provisions ." (A. 7a .)

The basis of that conclusion was that:

There is nothing in the record tha t satisfies

this court that the administering of morphine

in this case either overbore 'defendant’s will '

or that his confession was not 'the product of a

rational intellect and a free will.'"(a . 6a.)

Second, the court found that the circumstances surrounding

petitioner's initial apprehension and confession to Police Chief

Burroughs did not render the later statement involuntary.

"The State did not offer this confession in

evidence but the trial judge did admit the

confession of Dr. Headrick . . . . The 'no

break in the stream of events' contention was

buttressed by so-called 'uncontradicted' facts

in the first trial, but in this' trial this was

not true. This court holds that the ’no break

m the stream of events' contention in this

12

I'-'i V"-* ' 't■'•••» *-■>><*•• ;▼ .»'.-*« •I

instance is without merit." (A. 8a.)

justices (Heflin, C.J. and Lawson, J.) dissented "from

the portions of the majority opinion concerning the admissibility

of the confession." (A. 11a.) Directing themselves to the in

fluence of the morphine upon petitioner's will to confess, they

wrote: «

It must be concluded that expert testimony

to the effect that a drug did not cause an

impairment of the mental processes or have any

effect on mental capacity merely goes to establish

'coherency' and there must be further evidence

that the confession was the product of a rational

intellect and a free will in all aspects before

it is admissible." (A. 13a.)

B. The Wi therspoon Issue:

At the October 21 remand hearing directed by the Alabama ilSupreme Court to determine the constitutionality of the voir dire !

examination of petitioner's trial jury under Witherspoon v. Illinois,

391 U.S. 510 (1968), and Mathis v. Alabama, 403 U.S. 948 (1971), j

counsel for petitioner objected to the failure of the State to

have "the entire voir dire examination . . . in the transcript." '

(Remand Tr. 32.) At a minimum, counsel urged that petitioner

was entitled to an "explanation . . . as to why this [the transcript]

was not in the record." (Remand Tr. 32.) Defense counsel further

took the position "that it is the affirmative duty of the State

to show that none [scrupled veniremen] were challenged for cause."

i(Remand Tr. 29.) I

The trial court ruled that the state "has met any burden on

it" (Remand Tr. 31); and in itsformal findings, the trial court

concluded: ,

"1. No juror was challenged at the trial of

the defendant-appellant because of an affirmative

answer to a general question as to a fixed opinion i

against capital punishment." (Remand Tr. 35.)

In its December 9 opinion after remand, the Alabama Supreme

Court summarized the remand proceedings and affirmed petitioner's

sentence of death:

13

/ *'X W* ' *■ - .r-' *» •*'»«■. • 4 - «*

"The findings of the [trial] court are

I' overwhelmingly supported by the evidence.

!i Such facts precluded any possible applica

tion or operative influence of the doctrine

enunciated in Witherspoon and Boulden, supra "(A. 18a.) -- --'

4/

December 23, 1971, new counsel for petitioner filed a

. . _ i

; Petition for rehearing and brief in support of the petition for«

rehearing, arguing:

"We respectfully submit to this Court that

Witherspoon does not allow loose practices i

in the State's affirmative duty to prove

that no scrupled juror was challenged for

cause. A practice whereby participants in i

a trial are recalled and asked to speculate

as to what they remember at the time of the

trial can not be substituted for a transcript j

of the voir dire of the jurors . . . .

"The state thus failed to meet its burden of

making 'unmistakably clear' the fact that

no jurors were excused because of opposition

to the death penalty." (Defendant-Appellant's

Brief in Support of Petition for Rehearing,

pp. 10-11.)

Rehearing was denied without opinion.

4/ Following the October 21 remand hearing, petitioner was success-

ful in securing the aid of counsel whose participation he had I

sought by his request for an adjournment of that hearing. See [

sopra, p. 11. After entering the case, new counsel filed a

Motion for Leave to File Brief in the Alabama Supreme Court, which ■

reached and was filed in the Alabama Supreme Court on December 10, i

1971, one day after that court's decision had been rendered.

- 14 -

I

i

i

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted To

Determine Whether The Confession

Used To Convict Petitioner Was

Obtained Under Inherently Coercive

Circumstances, fn Violation Of His

Fourteenth Amendment Rights.

The constitutional precondition for admissibility of any

challenged confession is voluntariness. "The question in each

case is whether a defendant's will was overborne at the time

he confessed." Reck v. Pate, 367 U.S. 433, 440 (1961); see

Lynumn v. Illinois, 372 U.S. 528, 534 (1963). As Mr. Justice

Frankfurter put it;

"Is the confession the product of an

essentially free and unconstrained choice

by its maker? If it is, if he has willed

to confess, it may be used against him.

If it is not, if his will has been overborne

and his capacity for self-determination

critically impaired, the use of his confession

offends due process." (Culombe v. Connecticut.

367 U.S. 568, 602 (1961). -----------

In its earlier Beecher decision, this Court reviewed the

voluntariness of petitioner's confession and found:

"The petitioner, already wounded by the

police, was ordered at gunpoint to speak

his guilt or be killed. From that time

until he was directed five days later to

tell Alabama investigators 'what they wanted

to know,' there was 'no break in the stream

of events,' Clewis v. Texas, 386 U.S. 707,

710 * * * : For he was then still in pain,under the influence of drugs, and at the

complete mercy of the prison hospital

authorities." Beecher v. Alabama, 389 U S 35, 38 (1967). -------

On the present record, neither the testimonial differences

that the State now contends made petitioner's initial confession

to Police chief Burroughs voluntary nor the fact that the

State chose to use a confession obtained closer in time to

that initial confession than the one condemned by this Court

in Beecher I should lead to a different result. Both distinc

tions were suggested by a majority of the Alabama Supreme Court

15

•******■, ?s *%:r-:m.. y-.v+rr’*’- ■ .*. >.'•"• :-v ;*■>*■ **7?*v .lu -*». ., - •--■• . rr*\"'■• ■»•*-- '«? :.»>':■ • «■

!!

I ■ . ■ •* ) .-• ••■•• . .:..

IIII

j in confining Beecher I to its precise facts. But, as this

! Court expressly pointed out, the facts of a case may "differ

j in some respects from those in previous cases where we have

j ! held confessions to be involuntary. . . . fcl onstitutional

jj inquiry into the issue of voluntariness 'requires more than ar

Jj mere color matching of cases' Reck v. pate, 367 U.S. 433, 442

;; . . . Beecher v. Alabama 389 U.S. 35, 38 (1967) . And any

I "realistic appraisal of the circumstances in this case" (ibid

j emphasis in original) makes it plain (as two Justices below

■ concluded) that the State has failed to show petitioner's state

‘ I

ii ments here used to convict him were in fact voluntarily made.

! ’ A. On the Totality of the Circumstances of This Case,

Petitioner's Confession Was Not Voluntary.

|

The circumstances surrounding petitioner's initial "con

fession" are detailed at pp. 5-10, supra. Even if all con-

I ,

' tradictions in the evidence are resolved in favor of the State,

jj there remains a "total combination of circumstances ' . . .so

|! inherently coercive that its very existence is irreconcilableji

j with the possession of mental freedom. . . .'" Reck v. Pate,

ij

i 367 U.S. 433, at 442 (quoting Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U.S.

il

jj 143, 154 (1944) .)i

First, it is undisputed that petitioner was "physically

I weakened and in intense pain" (Reck v. Pate, supra, at 442)

. f

j after being felled by the rifle bullet. His right leg,

amputated five days later, was almost severed from his body.

Even though the force used to apprehend petitioner is not

challenged as unreasonable, the fact remains that petitioner

_5_/

h was suffering severely. A wound of this severity, at the

jj _5_/ Compare Davis v. North Carolina, 384 U.S. 737, 746 (1966)

in which this Court attached significance to the fact that Davis

had been given an extremely limited diet by the police, thus

j weakening his condition, even though "the record . . . [did)not

j show any deliberate attempt to starve Davis." And in Reck v.

j1 Patj;, 367 U.S. 433, 440 (1961), this Court proceeded on the

16

- ■ •• • ••» -•*?.. *%*»/

very least, disorients the exercise of normal judgment; and,

in petitioner's case, placed him wholly at the mercy of his

captors for both relief from pain and medical care. Operating

on a man who had been on the run for two days and "hadn't

eaten in some time, pain and helplessness "can be expected to

have had a significant effect on . . . [petitioner's] physical

strength and therefore his ability to resist." Davis v. North

Carolina, 384 U.S. 737, 746 (1966). See also Sims v. Georgia.

385 U.S. 538 (1967) .

Second, petitioner was fearful of mob violence, a con

clusion that is inescapable in the face of his constant pleas

to the arresting officers not to let "the mob" get him.-̂ The

risk of mob violence has consistently been considered a critical

circumstance "furnishing an atmosphere tending to subvert

petitioner's rationality and free will," Haynes v. Washington.

!l

5 / (Con't.)

°ffiCerS dld *"«*<* deliberate physical

Gir S? 9 ^ 1S° £ayt0n V* ^l-ted States, 222 F.2d 794, 796-97 (D.C Cir 1955), where a confession obtained "within an hour"

following violence necessarily inflicted by a police officer

involuntaryfGn^an*" Pr°CeSS °f his aPP™hansion was held

"We assume the officers had authority to use

the force reasonably necessary to effect the

arrest and confinement. But when a confession

is elicited so soon after the use of violence

upon the prisoner, resulting in bloodshed,

the compelling inference is that the confession

is not the free act of the prisoner. it is

immaterial that other coercion did not occur

at the moments he was questioned and signed the

statement. Violence at the hands of the police

admittedly had occurred within about an hour."

~ The testimony elicited on petitioner's motion for a change

venue (R. at 14-215) from Jackson County where the murder

,. Urr?d establishes that Mrs. Chisenall's murder and peti-

tioner s escape generated vast publicity in the press and o t h o r

friaht thJfc I?3?7 pe°ple in Alabaraa and Tennessee^l ike were

parses of f S Petitioner was at large; and that huge search parties of armed citizens ranged the Alabama and Tennessee

untryside searching for petitioner. The Chief of Police also

confirmed that a "mob" had been searching for petitioner

- 17 -

•J

» r a *

r

*

373 U.S. 503, 523 (1963)(dissenting opinion). See Chambers

v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227 (1940); Payne v. Arkansas. 356 U.S.

560 (1958).

Third, petitioner was also undoubtedly fearful of the

arresting officers who had shot him down. They approached with

guns at the ready; and although the Police Chief testified that*

he put away his gun after finding petitioner unarmed and that

neither officer pressed his gun against petitioner's nose, it

remains undisputed that the officer who shot petitioner kept

his rifle out at all times. it is also undisputed that the

officer fired the rifle into the ground twice close to

petitioner. Petitioner testified that he took this as a

threat. The Chief explained that the shots were a pre-arranged

signal, but admitted that nothing was said to petitioner to

explain that fact. At that point, according to the chief, he

demanded of petitioner, "Are you the man they are hunting in

Alabama?" and petitioner admitted that he was and that he had

raped and killed Mrs. Chisnenall. clearly these circumstances

were enough "to fill petitioner with terror and frightful

misgivings." Chambers v. Florida, 309 U.S. 227, 239 (1940).

The petitioners in Chambers found themselves "surrounded by

. . • accusers . . interrogated by men who held their very

lives — so far as these ignorant petitioners could know --

in the balance," 309 U.S., at 240. So did this petitioner.

Summarily, then, the record shows petitioner severely

wounded, hunted and hungry, in "intense pain," and in fear for

his life. He was lying helpless on the ground when the officers

reached him, fired shots into the ground near him, and demanded

whether he was the man being hunted in Alabama. On this record,

it would belie all human understanding to say that petitioner's

initial confession in the field was "essentially the product of j

a free and unconstrained will."

18 -

The State chose, of course, n

confession, but upon petitioner's ;

Dr. Headrick within the hour. Bot'

confession to the physician admiss

or applying the rule announced in !■

curring opinion in Darwin v. connec

approved by the full Court in Robin

666 (1968), that "when the prosecuf

uttered after an earlier one not ft

. . . the burden of proving not oni

was not itself the product of imprc

coercive conditions, but also that

by the existence of the earlier co:

Since the Alabama courts "applied -t'

case," ibid. — that is, failed to

the problem of multiple confession;:.'1

stitutiona1 grounds, bd., at 350 —

infected with fatal error and revet;

See Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 53

the full extent of the error because

tional standards are applied to the

record, petitioner's confession to j

not be held admissible consistently

Clewis v. Texas, 386 U.S. 707, 710 (

U.S. 538 (1967), 389 U.S. 404 (1967)

at 38.

Petitioner’s second confession

evidence at the trial now sought to ;

as much in "'the stream of events,'"

confession, made five days later at

Alabama, which Beecher I held inadmi

circumstances of the second confess:'

fully the influence of the first. N

- 19 -

rely upon this initial

quent statement made to

rts below held the

without considering

istice Harlan's con-

391 U.S. 346 (1968),

v. Tennessee. 392 U.S.

eeks to use a confession

o be voluntary, it has i

t the later confession

hreats or promises or

s not directly produced

on." 391 U.S., at 351.

ong standard in this

the "proper approach to

I

llenged on federal con- j

judgment below is

upon that account alone.

61). But that is not

-e the proper constitu-

ntested facts of this

eadrick plainly could

the principles of

) ; Sims v. Georgia, 38 5

:i Beecher I, 389 U.S.,

he one admitted into

•;viewed — was surely

I- , as his third

rison hospital in

e. Indeed, the

speak far more force-

ly did it follow by

• ■'s»‘'jfnw - - •

j one hour, rather than five days, the shooting of petitioner and

l his confession in the field; not only was it made to the

| physician who was giving petitioner first aid for a nearly

•I severed leg; but in Beecher I this Court noted that, prior to

I1 .j the confession there invalidated, the state investigators

'! testified that "they had told the petitioner. . . that he was

jj under no obligation to speak and that anything he said could be

j| used a9ainst him." 389 U.S., at 37, n. 4. in sharp contrast,

" ■*■*' ■'■s undisputed that, prior to his statement to Dr. Headrick

i!jl petitioner was not advised either of his right to be silent

i i

| or of his right to counsel. Although no claim is or could be

i 7 /

I made here under Miranda v. Arizona. 384 U.S. 436 (1966),

the absence of any constitutional warnings is nonetheless

!i .j, relevant to the issue of voluntariness, Davis v. North Carolina.

J; 384 u*s* 737, 740-741 (1966), and a fortiori to the issue

ij whether petitioner's second confession was "directly produced jj h y t h e existence of (hisl . . . earlier confession." Darwin

|| v* Connecticut, 391 U.S. 346, 351 (1968) (opinion of Mr. Justice| i •jj Harlan) .

j

Upon this record, both the conclusions that petitioner's

first confession impermissibly influenced his second and that

the second itself was involuntary cannot be avoided. The two

confessions were made within the span of one'hour, separated

only by petitioner’s ride to the hospital in the back of a

flatbed truck while severely wounded, and petitioner's receipt

Q /

of two injections totaling a half grain of morphine. The

pressure on petitioner was continuous, part and parcel of the

_7_/ Jenkins v. Delaware. 395 U.S. 213 (1969).

noted by this Court in Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293

308 n. 4 (1963) the determination of whether a" drug "caused"

an accused to confess is to be made in the context of the

"relevant circumstances."

- 20 -

* •- • ---- * ... -

same transaction as it affected petitioner's state of mind —

the critical determinant for resolution of the constitutional

issue. All were simply parts of one continuous process."

Leyra_ y. Denno, 347 U.S. 556, 561 (1954).

When petitioner arrived at the hospital, he was weakened,

wounded and in intense pain. Dr. Headrick described him:

"I felt sorry for this man. He looked

almost like an animal. i was trying in

the best way i could to make him comfortable,

of course, to relieve his pain, offer him

cigarettes and that sort of thing to make

him comfortable. He hadn't eaten in some

time either." (r . 281.)

Two quarter-grain shots of morphine, as the Supreme Court of

Alabama acknowledged, were "not enough to alleviate all of

defendant's pain." (A. 5.) At the hospital, there were

numbers of policemen "all over the place"; one could "hear

all sorts of voices as many policemen were concerned." And

the haunting fear of mob violence was about . . . in an

atmosphere charged with excitement and public indignation."

^fflbers v* E-lorida, 309 U.S. 227, 240 (1940). cf. Payne v.

Arkansas, 356 U.S. 560 (1958).

Most significantly, petitioner was given a very substan

tial dose of morphine. Morphine has the capacity to induce a

confession by weakening and clouding a person's ability to

make self-interested judgments, rationally to appraise his

circumstances and to weigh the consequences of admitting guilt.

3-/ Petitioner was given \ grain subcutaneously and % grain

intravenously. The average adult subcutaneous dosage il k grain

. BECKMAN, PHARMACOLOGY 226 (1961). Alternatively, "Mlntra-

venous administration of 10 mg. [1/6 grain] will give quicker and

somewhat greater relief. . . . » ibid. See also L. GOODMAN and

.GILMAN, THE PHARMACOLOGICAL BASIS OF THERAPEUTICS 239-240

DRUGS 21 ^1957) A * REYN0LDS 3nd L* RANDALL, MORPHINE and ALLIED

21

The authorities list among the effects of morphine "difficulty-

in thinking," "mental clouding," "depression of inhibitory

mechanisms," "freedom from . . . restraining conditions,"

JL £ /"uninhibited" and "trustful." Dr. Headrick testified that

the drug gives one a "feeling of well being."

10/ See Comment, "Admissibility of Confessions and Denials

Made Under the Influence of Drugs," 52 N.W.L. REV. 666, 667

(1957) :

"The opiate drugs, the most common of which

are opium, heroin, morphine and codeine,

cause drowsiness, inability to concentrate,

difficulty in thinking and sometimes

hallucinations."

A. GROLLMAN and E. GROLLMAN, PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS

(7th Ed., 1970) :

"The action of morphine consists mainly of

a descending depression of the central nervous

system. Its apparent stimulant effects are

attributable to depression of inhibitory

mechanisms . . . In addition to its action in

abolishing pain, morphine induces a sense of

well-being (euphoria) and facilitates certain

mental processes while retarding others. There

is a feeling of freedom from the restraining

conditions which previously limited activity;

the imagination is untrammeled by its usual

controls. . . ." (Ij3. at 103).

L. GOODMAN and A. GILMAN, supra at 250:

"Morphine also produces mental clouding

characterized by drowsiness and inability

to concentrate, difficulty in mentation,

apathy . . . and lethargy. Mental and

physical performance is impaired . . . .

Morphine and related drugs rarely produce the

garrulous, silly, and emotionally labile

behavior frequently seen with alcohol and

barbiturate intoxication."

The discussion notes that no slurred speech or significant

loss of motor coordination is noticeable in a person under

the influence of morphine because the central depressant action

of morphine is unlike that of the inhalation of anesthetics

or barbiturates. See also H. BECKMAN, supra at 225, noting

that even though a patient may be conscious after taking

morphine, he is still "likely to be mentally clouded":

" [Morphine] apparently introduces awareness

of pleasant things to shove aside awareness

of what is not wanted . . . I t seems actually

to make the individual indifferent to the pain

he perceives." (I_d. at 2 26).

?"r4 ci,*vw.'.̂, **. -.**•< - .3* **'•'. *t*r~''%*??i*i 'H'-M-a.'t ■..

II I

Immediately prior to the morphine shots, petitioner --

so weary and wounded that he "looked almost like an animal" --

was apparently not talkative, said nothing to Dr. Headrick. |

The shots put him "at ease", made him feel "relaxed" and like

he "wanted to love somebody." it was then that Dr. Headrick ', , . . 11 / asked petitioner why he committed the crime, and petitioner

I Q _ / (Con ’ t.)

See also Smith, Subjective Effects of Heroin and Morphine in

Normal _Sub jects_, 13 6 JOURNAL OF PHARMACOLOGY AND E X P E R I M E N T A L

THERAPEUTICS 47 (1962)(in which the author lists the following

as effects reported by subjects under the influence of morphine

mental clouding," "mental inactivity," "obliging attitude,"

"mentally slow," "trustful," "uninhibited," "contented,"

"carefree," "talkative," "light-headed"); t . SOLLMAN, A MANUAL

OF PHARMACOLOGY, 293 (8th Ed. 1964)("Free imagination but

confused intelligence"); A. REYNOLDS and L. RANDALL, supra at

21 22; J. LEWIS, AN INTRODUCTION TO PHARMACOLOGY, 392 (3rd Ed

1964); Beaver, The _An_algesic Effects of Morphine and Methadone!

8 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND THERAPEUTICS 415 (May-June' 1967)~T~

The above effects are described as incident to normal dosage. See supra, n. 9.

jyV The Alabama Supreme Court's conclusion that "[i]n fact,

is noh clearly established that the doctor even questioned

defendant" (A. 5a) is plainly erroneous upon the whole record.

It is true that in one instance, the doctor related: "I am not

exactly sure if I asked him specific questions but he told me

quite a bit about it," and that "[i]n another place, the doctor I

indicated I think I asked him why did he do it." (A. 4a, 6a). |

But the doctor also testified unambiguously in response to the

State s questioning that he asked petitioner "why lie did it,"

and that prior to that time petitioner had made no statement

as to what he had done. ( R . 315.) See supra, p . 9 . j

The trial court also relied heavily on the fact that Dr.

Headrick was not an employee of the police or acting at their

behest ( R . 311); and the Alabama Supreme Court made the same

point (A. 6a)„ But petitioner was brought to the hospital by

the arresting officers for treatment; he was never out of their

control; Dr. Headrick treated him at their request; and their

presence dominated the atmosphere. Although there were

apparently no police officers in the treatment room itself at

the time of the confession, "there were officers all over the

place, and in the hall and at the door." Petitioner was

unquestionably in police custody, and was in no physical or

mental state to make fine distinctions concerning the character j

of the surrounding personnel. Under these circumstances, the

fact that the doctor was a "private" individual does not lessen ,

his contribution to the totality of factors that rendered peti

tioner s convession involuntary. See Sims v. Georgia, 385 U.S.

533 (1967), 339 U.S. 404 (1967)(confession made after defendant i

was abused by private physician while in police custody)•

Robinson v. Tennessee, 392 U.S. 666 (1963)(confession made to

23

4- f • " '

told the doctor, a complete stranger, his entire life history-

in addition to confessing an offense which would cost him his

life. The fact that petitioner was under the "influence of

drugs," Beecher v. Alabama. 389 U.S. 35, 38 (1967) — a factor

that this Court has repeatedly held significant in assessing

the voluntariness of a confession, Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S.

12/293 (1962); Jackson -v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 (1964) -- here

combined with other coercive circumstances to cross "the line13./of distinction" and vitiate petitioner's will.

11/ (Con't.)

reporters following earlier confession extracted by police). 1

This case therefore does not present the question (long 1

settled in the affirmative, in any event) whether an involuntary

confession extracted by a private person is constitutionally

inadmissible in a criminal prosecution. See Bram v. United

States, 168 U.S. 532 (1879) ; United States v. Pobinsoiu 439

F.2d 553 (D.C. Cir. 1970), and cases cited in note 8 therein. !

12./ !n Jackson, Mr. Justice Black (concurring and dissenting)

would have ruled the drug-affected confession inadmissible

because "given under circumstances that were 'inherently

coercive,' . . . and therefore . . . not constitutionally

admissible under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments." 378

U.S., at 409. I

See also Logner v. North Carolina. 260 F. Supp. 970

(M.D.N.C. 1966)(defendant under influence of alcohol and

amphetamine, Syndrox; confessions while in police custody held

involuntary); In re Cameron. 67 Cal. Rptr. 529, ___ Cal.2d ,

439 P.2d 633 (1968) (defendant under influence of alcohol and

tranquilizer, Thorazine; confessions while hospitalized held

involuntary); Reddish v. State. 167 So.2d 858 (Fla. 1964)

(wounded defendant given demerol to ease pain; confession held i

involuntary, the Court commenting that demerol "appears to be

in usage as a substitute for morphine, perhaps somewhat less

likely to produce psychic effects but nonetheless in a class

with the opiates. . . . " (167 So.2d,at 861)) ; State v. Graffam, 1

202 La. 869, 13 So.2d 249 (1943)(wounded defendant in hospital

given morphine and other drugs; confession held involuntary).

13/ Culombe v. Connecticut, 367 U.S. 568, 602 (1961)(opinion

of Mr. Justice Frankfurter): "The line of distinction is that

at which governing self-direction is lost and compulsion, of

whatever nature or however infused, propels or helps to propel the confession."

- 24

B. Petitioner's Confession Cannot Be Sustained as Voluntary

upon this Record Because the Courts Below Failed to Make

An Adequate Inquiry Concerning the Effects of the Dosage

of Morphine Administered to Petitioner.

There is an additional weighty reason why petitioner's

confession to Dr. Headrick fails to satisfy the requirements

for constitutional admissibility. Upon the record before the

courts below, and now before this Court, there is insufficient

evidence or inquiry concerning the properties of morphine and

its effect upon petitioner to sustain the State's burden of

showing voluntariness of a confession made following adminis

tration of the drug. it was for this reason that the two

dissenting Justices below concluded that "the confession by

the defendant to Dr. Headrick in the case at bar fails to meet

the necessary standard of voluntariness as required by this

Court's decisions and controlling decisions by the Supreme Court

of the United States." (A. 16a.)

"rw]hen a confession is challenged as involuntary and is

sought to be used against a criminal defendant at his trial,

he is entitled to a reliable and clear-cut determination that

the confession was in fact voluntarily rendered," Lego v.

Twomey, 30 L.Ed.2d 618, 627 (1972); and the burden is on the

State to prove voluntariness by a preponderance of the evidence,

ibid. Here, the evidence disclosed that petitioner confessed

immediately following the injection of two quarter-grain shots

of morphine. If the morphine so affected petitioner that "his

confession was not 'the product of a rational intellect and a

free will,' his confession is inadmissible. . . . " Townsend

v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293, 307 (1963). The courts below were

therefore required, as a constitutional prerequisite for

admission of this confession, to inquire and determine upon an

adequate evidentiary record the extent to which the quantity

of morphine that petitioner received affected his will to

confess.

Two witnesses testified concerning the effects of the

jmorphine upon petitioner: petitioner himself and Dr. Headrick,

ij Petitioner testified, as noted at p. 10 supra, that after the‘I

l| morphine, he felt "at ease," "relaxed, " "like. . .[he] wanted to

ilove somebody;" that he did not lose consciousness but "didn't

have control of [his] . . . mind;" and that he could not rememberI!

|‘ the contents of his subsequent conversation with Dr. Headrick.

Dr. Headrick's relevant testimony, elicited upon voir dire exami-

j'nation, was as follows:

ij Q- [hy the prosecuting attorney] : I will ask

you, doctor, did you administer any treat

ment to him at that time?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. What was that?

A. He had a gunshot wound of the leg and the tibia

was shattered and the leg was cleansed and

packed with gauze and he was given a medication

for pain and the wound wrapped and strapped so

he could be transported.

Q. What kind of medication did you give him?

A. Morphine. (R. 276.)* * *

The Court: How much morphine did you give him?

A. I gave him a quarter of a grain intravenously

and a quarter of a grain muscularly.

The Court: What effect would it have on his mental

capacity?

A. Well, morphine will relieve pain and make a

patient have a feeling of well being. it

doesn t - - unless you get a tremendous over

dose where it suppresses respiration or makes

them unconscious - -

The Court: This particular case, in your opinion

did he know what he was talking about?

A

•/ *r*f. . ■■■■’■'■-.A>- ••<-‘v* .. . j î V v* «* .«. ,.-■■*.••• • * *-■ V Vv'* **

A. Yes, sir.

The Court: And know the meaning of it?

A. Yes, sir.

The Court: Realized it?

A. This dosage was not even big enough to

completely relieve all of his pain.

The Court: All right. Go ahead. (R. at 278.)* * *

"Q. [by defense counsel]. And you then -- you

administered morphine?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. Intraveneously [sic] and muscularly?

A. Yes, sir.

0. Did you give him anything else for pain?

A. No, sir, that is all.

Q. You say the dosage administered to him was not

completely enough to alleviate him of all the

pain [sic]?

A. Yes, sir, he still had pain to try to move

him." (R. 280.)

After the trial court had ruled the confession voluntary

and admissible. Dr. Headrick further testified before the jury,

to the following effect:

* * j

."Q. [by the prosecuting attorney]. Now, doctor,

you said you gave him some morphine. What

effect would the morphine that you have -- that

you gave him have on him?

A. Ease his pain, make him have a feeling of well

being, relax him.

Q. It wouldn't effect [sic] his mental capacity

in any way?

•J■\ Y

27

; • 9K-TW t » < \ « ft- M 1 r

i **i

\' ■

i

i| A. No sir, not unless he became unconscious,

jl If he had had an overdose of course, respira-

tion would be effected [sic] and he would be

unconscious.

i Q * Did you give him anything besides morphine?

The Court: Let me interrupt. You didn't give

*

;i an overdose, did you?

l! A. No, sir." (R. 314-315.)•j

This is literally all of the evidence in the record con-

|j cerning the impact of the two morphine shots upon petitioner's

ii critical confession, which followed immediately after their

|j

!| administration. The trial court made no specific findings of fact

’ I

jj relating to the drug. Clearly, its inquiry on the subject was

i j inadequate. For, even putting aside what is medically known about!

jj morphine (see pp. 21-24 supra) because no information of the sortif i

was introduced in the trial court by either the prosecution or the |I j

indigent petitioner's court appointed defense counsel, the court

was uncontestably confronted with a confession following injection'II |

of a drug sufficiently potent to make a man whose leg was nearly j

i I

severed feel like he "wanted to love somebody" and tell a strange

doctor his life history. These facts alone put the court oni !

i' inquiry, c_£. Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375 (1966), that the ;

drug's effect upon petitioner's will was a material issue going to

the voluntariness of his confession. Nevertheless, the court

confined its inquiry to petitioner's "mental capacity" and | '

lucidity -- whether he "did know what he was talking about" and

"know the meaning of it" — and entirely failed to explore the

effect of the drug upon voluntariness. The prosecution, which

had the burden of proof of voluntariness, did no more.

The Supreme Court of Alabama filled this gap of inquiry

(in the words of the dissenting Justices below) by "wrongfully

28

(A. 15a.)[placing]. . . the burden of proof on the defendant."

The majority opinion begins by recognizing that "extrajudicial

confessions are prima facie involuntary and inadmissible" and

that the court must be satisfied of their voluntariness before

' admitting them. (A. 3a.) But it sustains the admission of peti

tioner's confession upon the express ground that:

;j "There is nothing in the record that satisfies

the court that the administering of morphine

ji in this case either overbore 'defendant's

will' or that his confession was not 'the ij product of a rational intellect and a free

will.' " (A. 6a.)

Obviously, the Courts below neither did nor could find upon this

;| record that the State met its burden of proof on the confession 14/

j issue. Rather, to quote once more from Chief Justice Heflin's

iM/ In this connection it should bd noted that, within a few

days of the filing of the Beecher opinion, the Alabama Supreme

jjCourt denied certiorari to the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals

j in another drug-affected confession case. Dannelly v. State,

254 So.2d 434 (Ala. Ct. Crim. App.), cert, denied, 254 So.2d 443

i; (Ala. 1971) . in that case, the record revealed that defendant

i| had been given an unspecified dosage of tranquilizers (Sparine

and Mellaril) prior to his confession. The Court of Criminal

Appeals concluded

: . .from the pattern of cases that tranquilizers

| not administered with other potentiating drugs are

prima facie innocuous as affecting the rational and

volitive faculties. In other words, the defense has

the onus of persuasion to show an overbearing of the

will." (254 So.2d, at 440.)! i

;i Chief Justice Heflin concurred in the decision of the Alabama

•Supreme Court to deny certiorari but stated:

"• • -I want it clearly understood that I do

not approve all of the language contained in

the opinion of the Court of Criminal Appeals.

My position concerning drug-affected confessions

j was set forth in a dissenting opinion in Beecher

v. State, . . ." (254 So.2d at 443.)

29

- •

||dissenting opinion in the Alabama Supreme Court, the evidence

ijregarding the nature and effect of morphine, viewed

jl „I,1 . . . m its most favorable light for the State,

• . . merely showed that the defendant knew what

|| he was talking about; knew the meaning of what

he said; realized what he was saying; and the

morphine did not affect his mental capacity."(A • 1 2a •) i

j! "It be concluded that [the] expert testimony

[ m this case] to the effect that, a drug did not

cause an impairment of the mental process or have

any effect on mental capacity merely goes to

establish 'coherency' and there must be further

Ij evidence that the confession was the product of

■! a rational intellect and free will in all aspects

before it is admissible." (A. 13a.)

It is also the teaching of this Court’s cases that neither

.coherency (Townsend v. sain, 372 u . s . 293 (1963) > “ '"nor reliability

■ (Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U.S. 534 (1961) ) is the benchmark of a

jconstitutionally admissible confession. Therefore, whether the j

courts below fai^cd to apply these principles (See Rogers v.

Richmond, supra), or misassigned the burden of proof connected

15/ This is not to deny that coherency is relevant to the

question whether an accused's will is overborne. Certainly where

the hallmark of a particular drug is that it distorts speech and

cognitive and emotional reactions, the presence of incoherent

speec may indicate impaired mental and emotional functions and

the extent of a particular drug's effect on volition? B^tSere

is absolutely nothing in the record of this case to establish

such a linkage between coherency of speech and the effect of

morphine upon defensive and cognitive processes in a subject

Judicially noticeable materials noted supra at np. 21-24 i

no such a correlation where morphine is concerned. ' ej

I1|/ As difficult as such tasks may be to accomplish, the judge

j is . . .duty-bound to ignore implications of reliability in

facts relevant to coercion and to shut from his mind any internal

evidence of authenticity which a confession itself may bear "

(Leg° v - Twomey, 30 L.ed 2d 618, 625 (1972).) Y

17/ The Alabama Supreme Court is at great pains to confine

this Court s decisions in both Beecher I and Townsend v. Sain

supra, to their particular factiT (A. 3a-4a,~6a, 7a-8a )

- 30 -

* * * * * O t o * 5 * .S 5 r ? * k '* W ■"'■'■ * * * '• * . ,& l.4 L i? . ; .-%;■■?■ * .'.. - • • -- - V v . - . . . . •* . »• ' v ~ "• . # * ■ ' " • ■ -•' ^ * * . * » \ .. ' t v ,~ ■-. • V

jwith them (see Lego v. Twomey, 30 L.ed 2d 618 (1972)), or mis- (| |