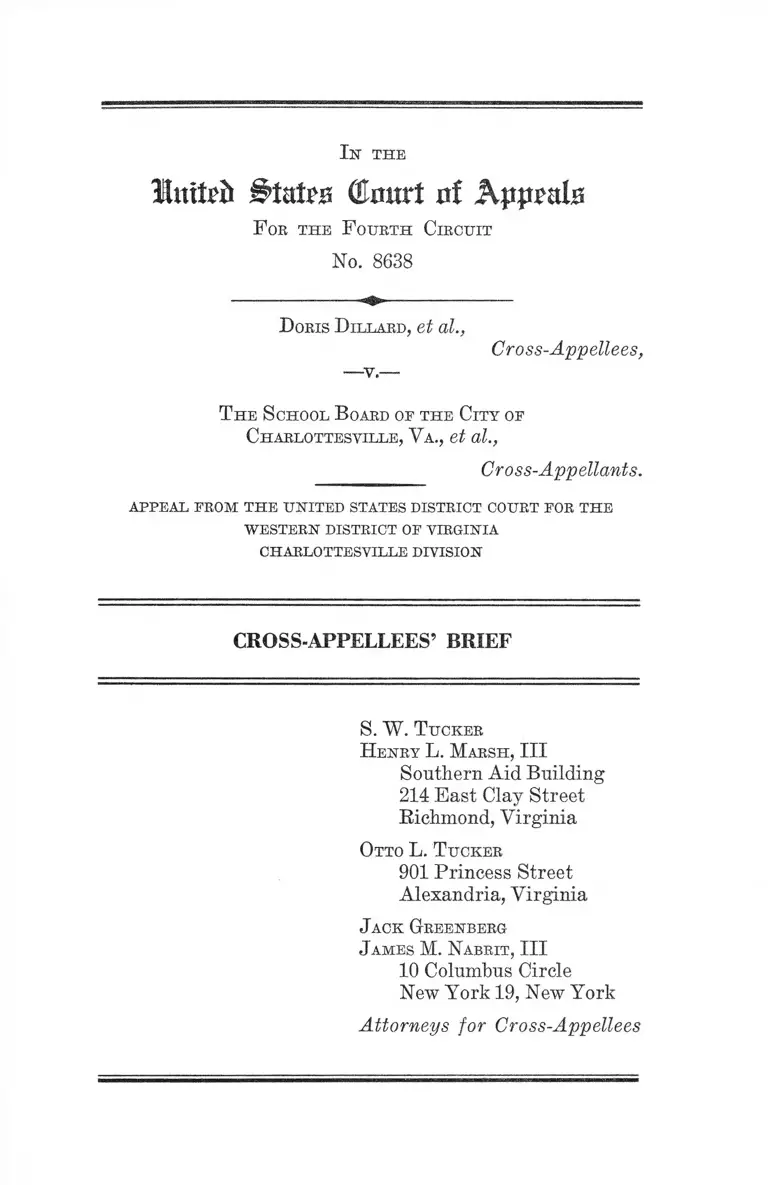

Dillard v. City of Charlottesville, VA School Board Cross-Appellees' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dillard v. City of Charlottesville, VA School Board Cross-Appellees' Brief, 1962. 9de1fae2-af9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/128b6fb1-fe46-4923-9efa-fe56f165bd82/dillard-v-city-of-charlottesville-va-school-board-cross-appellees-brief. Accessed January 29, 2026.

Copied!

lititefc dxmxt iif Kppmlz

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 8638

I n the

D oris D illard, et al.,

Cross-Appellees,

T he S chool B oard of the City of

Charlottesville, V a ., et al.,

Cross-Appellants.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

CHARLOTTESVILLE DIVISION

CROSS-APPELLEES’ BRIEF

S. W . T ucker

H enry L. Marsh, III

Southern Aid Building

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Cross-Appellees

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

Question Involved ............................................................ 3

Statement of the Facts .................................................... 3

Argument ........................................................................... 6

Conclusion ........ 9

T able oe Cases

Dodson v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir. 1961) ......................2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ........... 8

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke,------F. 2d

------ (4th Cir., No. 8534, May 22, 1961) .................. 6, 8

Hamm. v. County School Board of Arlington, 264 F. 2d

945 (4th Cir. 1959) ......... 6

Hill v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473

(4th Cir. 1960) ................................................................ 6

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d

77 (4th Cir. 1960) ........................................................ 6

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370

(5th Cir. 1960) ........................... 6

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir. 1951) 8

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) ....... 6, 8

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1956), cert. den. 353 U. S. 910 2

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

263 F. 2d 295 (4th Cir. 1959) 2

I n the

luttefc #tate (Unitrt of Kppmls

F oe the F ourth Circuit

No. 8638

D oris D illard, et al.,

Cross-Appellees,

— y.—

T he S chool B oard oe the City of

Charlottesville, Va., et al.,

Cross-Appellants.

appeal from the united states district court for the

WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

CHARLOTTESVILLE DIVISION

CROSS-APPELLEES’ BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This cross-appeal was taken by the defendants School

Board of the City of Charlottesville, Va., et al., from an

injunction entered December 18, 1961 (59a).1

The defendants’ cross-appeal is from the portions of the

December 18th order relating to high school pupil assign

ments (e.g., the first two paragraphs on 60a). The issues

involved on plaintiffs’ appeal from the portions of this

order relating to elementary school pupils are discussed

in a separate “Appellants’ Brief” previously filed herein.

1 The appendix references herein are to pages in the Appellants’

Appendix filed herein on the appeal by plaintiffs below unless other

wise indicated.

2

Various aspects of this school segregation case have been

before this Court on several prior occasions. See School

Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen, 240 F. 2d 59

(4th Cir. 1956), cert, den. 353 U. S. 910; Id,, 263 F. 2d 295

(4th Cir. 1959); and same case sub nom. Dodson v. School

Board of City of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d 439 (4th Cir.

1961). The injunction involved in this cross-appeal resulted

from further proceedings in the trial court following this

Court’s decision in Dodson, supra. On August 11, 1961,

twenty-five Negro pupils (8 high school students and 17

elementary pupils) filed a motion for further relief (16a)

attacking the Charlottesville School Board’s pupil assign

ment practices as racially discriminatory and seeking ad

mission to various predominantly white schools for the

1961-62 term. One additional high school pupil was per

mitted to join the motion subsequently (21a). The trial

court allowed those pupils not already parties to the case

to intervene and held a trial on October 23-24, 1961.

On December 18, 1961, the District Court filed an opinion

(48a). With regard to the high schools the Court held that

“ it is plain that the practices in force cannot be approved

in the light of the Court of Appeals’ opinion in Dodson v.

School Board” (54a). The Court held that since “white

pupils are allowed to attend Lane High School without

regard to where they live in the city and without regard

to their scholastic attainments or prospects” this “ same

privilege must be accorded to Negro students” (57a). Find

ing that the school authorities were continuing the same

practices with respect to high school pupils which had been

previously held to be discriminatory by this Court in the

Dodson opinion, supra, the Court ordered the defendants

to admit the 9 Negro plaintiffs who had applied to Lane

High School to that school, enjoined the defendants “ from

denying admission to Lane High School to any child in the

3

City of Charlottesville, situated similarly to such plaintiffs

and intervenors, by the application of any criteria which do

not apply to white children attending that school” (60a).

The trial court stayed its order pending appeal (61a).

The School Board filed its notice of cross-appeal on Janu

ary 16, 1962. Subsequently, the School Board withdrew its

appeal as to two of the high school plaintiffs whose appli

cations were opposed only on the ground that they lived

closer to the all-Negro Burley School than to Lane High

School (see School Board’s Brief herein, p. 21), and this

portion of the cross-appeal was dismissed on May 8, 1962.

Question Involved

Can the school authorities exclude Negro pupils from

a predominantly white (formerly all-white) high school, to

which every white high school pupil in the City is assigned

automatically, on the basis of academic standards not ap

plied to any white pupils assigned to this school.

Statement of the Facts

The facts relating to this cross-appeal are relatively

simple and are uncontradicted. The trial court’s finding

that no significant change has been made in the high school

assignment practices since this Court’s opinion in Dodson

v. School Board, 289 F. 2d 439, 433 (4th Cir., April 14,1961),

is not challenged in the Board’s brief. The material facts

are set forth in the following quoted portions of the opinion

below:

The two high schools in the city are Lane, the school

for white pupils, and Burley, the school for Negroes.

No areas of residence have been fixed for attendance

at these schools, and before this litigation began all

4

white pupils in the city went to Lane and all Negroes

to Burley. As a result of court action in recent years

some Negroes have been admitted to Lane while all

white students continue to go there. However, in deter

mining attendance at Lane different rules are applied

as between white and Negro children. Any white child

who finishes elementary school may enter Lane High

School automatically—i.e. without being subject to any

test or condition as to residence or academic qualifica

tion. On the other hand, in order to attend Lane,

Negroes must live closer to that school than to Burley

and must also satisfy certain tests touching their scho

lastic advancement and intelligence (54a-55a).

# * # *

The curriculum at Lane is about the same as the aver

age white high school, designed to prepare students

to enter the standard college and pursue their educa

tion there. At Burley more attention is given to manual

training and studies aimed to furnish the student a

means of livelihood at some manual or domestic em

ployment upon finishing high school. Some of the col

lege preparatory courses given at Lane are absent from

Burley. Speaking of this the Superintendent of Schopls

said that Burley “ can take better care of children whose

competences don’t lie in the academic realm.” This

condition lends encouragement to the practice which

the school authorities have exercised of considering the

academic record and prospects of pupils in assigning

them to one school or the other. Negroes displaying

good records and high intelligence may be, and some

have been, assigned to Lane. But those of less promise

are sent to Burley (56a).2

2 See also testimony at pp. 35-36, School Board’s Appendix.

5

Prior to the 1961-62 school term, 9 Negro plaintiffs (4

of whom were appellants in Dodson) applied for Lane and

were denied admission (School Board’s Appendix, 33-34);

10 other Negroes were admitted to Lane this year (School

Board’s Appendix, 41). A total of 16 Negro pupils attended

Lane during the current term (Id.).

The achievement and intelligence test scores and teach

ers’ comments for the high school applicants who were

denied transfer on the basis of the academic criterion ap

pear in the record (School Board’s Appendix, 11-14, 16).

The four plaintiffs who had been appellants in Dodson

were rejected on the basis of the same academic records

presented to the Court in 1960. Similar test scores were

presented with respect to the others, except plaintiff George

W. King, III, with respect to whom no information was

presented. As the court below stated, these pupils were

rejected on the basis of the school superintendent’s belief

that they “would not do satisfactory work if allowed to

enroll in the white school” (55a-56a).

As indicated above, the defendants have withdrawn their

appeal as to the two pupils who were denied admission to

Lane only because they lived closer to Burley High School.

The defendants’ brief indicates that they are now prepared

to abandon this residence requirement and propose to

screen Negro pupils applying to Lane only on the basis of

the academic standards, stating that “any Negro child in

the City of Charlottesville can qualify for enrollment in

Lane as far as geographical factors are concerned” (p. 23,

“ Brief of Appellees and Cross-Appellants” ).

6

Argument

The single issue involved in this cross-appeal has been

decided repeatedly against the contention made by the

School Board by this Court in this3 and other cases,4 5 as

well as by other appellate courts.6 The consistent line of

decisions hold that the application of transfer or assign

ment criteria to Negro pupils and not to white pupils is a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. This same issue

was before this Court in this ease just a year ago and was

decided against the School Board’s claim. At that time the

Court ruled in unequivocal language that the defendants’

application of its assignment plan with respect to high

schools was “ offensive to. the constitutional rights of Ne

groes” (Dodson, supra at 443). This Court stated that it

was not reversing the trial court judgment which had re

fused to enjoin these practices, as it “would normally be

required to” do, because the “ school authorities have not

attempted to defend the present method of assigning pupils

as a permanent assignment system” and the procedures

were “ designed to be temporary measures only” (Id. at

444). The Court observed that the District Judge could

“ re-examine the situation prior to the opening of schools

in the coming year” (Id.). The present appeal is the prod

uct of that re-examination. The trial judge properly con-

3 Dodson v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, 289 F. 2d

439, 443 (4th Cir. 1961).

4 Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, not yet reported

(4th Cir., No. 8534, May 22, 1961); Jones v. School Board of City

of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, 77 (4th Cir. 1960); Hill v. School

Board of City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473 (4th Cir. 1960); Hamm v.

County School Board of Arlington County, 264 F. 2d 945, 946

(4th Cir. 1959).

5 Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 803, 806-809 (8th Cir.

1961); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370

374-37 (5th Cir. 1960).

7

eluded that under this Court’s opinion it was bound to find

the assignment procedures to be discriminatory (58a), and

it enjoined their continued use.

The pattern of discrimination is very clear. All white

students in Charlottesville who complete the elementary

grades are automatically assigned to Lane High School.

But Negro pupils have again been required, as they have

in the past, to meet special geographic and academic

standards to enter Lane. Otherwise, they are assigned

to the all-Negro Burley High School. The School Board’s

belated withdrawal of the geographic requirement pending

this appeal cannot bolster up the discriminatory academic

requirements still sought to be imposed on Negro pupils

entering Lane. This Court made it clear in Dodson, supra,

that both the academic and geographic criteria were being

applied improperly in the Charlottesville High Schools,

stating (289 F. 2d at 443):

All white students are automatically assigned initially

to Lane High School, regardless of their place of resi

dence or level of academic achievement. All white

public high school students in the city presently attend

Lane. Absolutely no assignment criteria are applied

to them. On the other hand, residence and academic

achievement criteria are applied to Negro high school

pupils. As the plan is presently administered, if a

coloted child lives closer to Burley than to Lane, lie

must attend Burley High School. Moreover, even if a

Negro student does live closer to Lane, he may not be

permitted to attend it unless he performs satisfactorily

on scholastic aptitude and intelligence tests—a hurdle

white students are not called upon to overcome.

Such administration of public school assignments is

patently discriminatory. As pointed out previously,

the law does not permit applying assignment criteria

to Negroes and not to whites.

8

The present cross-appeal is a manifest attempt to reliti

gate the same issues previously decided herein. The School

Board’s request that the holding in Dodson, supra, be over

ruled is accompanied by an argument that the plaintiff

high school pupils have academic deficiencies so serious

and test scores so low that they cannot do successful work

at Lane and that it would be to their detriment to be trans

ferred as they request. The District Court answered this

argument in a manner consistent with the rulings of this

Court, stating at one point during the trial:

The Court: However good reason that might be

in its appeal to the school authorities, however their

experience in handling the school children and so forth,

that fact is that this child and her parents, or his

parents, whichever it is, didn’t regard that as a reason

for not applying for admission to the white school.

Now, if they had a constitutional right to go to that

school, then the judgment of the school authorities

shouldn’t be set up to bar that right, now how un

fortunate the exercise of it might turn out to be

(School Board’s Appendix, p. 49).

On May 22nd of this year, this Court made a similar

holding in Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, not

yet reported (4th Cir., No. 8534), stating:

The board’s explanation that this special requirement

is imposed on Negroes to assure against any “who

would be failures” is no answer. The record discloses

that no similar solicitude is bestowed upon white pupils.

See Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256, 258 (8th Cir. 1960);

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798, 809 (8th Cir. 1961); and

cf. McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949, 953-954 (4th

Cir. 1951), all rejecting the same argument that Negroes

9

should be retained in segregated schools because this would

be in their best interests as determined by state authorities.

It may be noted, in conclusion, that the School Board

no longer defends this criterion as a temporary measure

which is part of a desegregation plan. Certainly no specific

timetable6 for eliminating this requirement has ever been

proposed by the School Board. In this circumstance the

court below was plainly correct in enjoining this practice.

The court also properly retained jurisdiction of the case

for any appropriate further proceedings (61a).

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that those portions of the

judgment below which relate to the defendants’ practices

in assigning the plaintiffs who are high school pupils

and others similarly situated should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W . T ucker

H enry L. Marsh, III

Southern Aid Building

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Cross-Appellees

6 Cf. Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, not yet re

ported (4th Cir., No. 8534, May 22, 1962); Hill v. School Board

of City of Norfolk, 282 F. 2d 473, 475 (4th Cir. 1960).

o ^ l p » 38