Brazier v. Cherry Brief of Counsel for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brazier v. Cherry Brief of Counsel for Appellees, 1961. a3121a51-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/131bf1f1-91d9-4d42-a43c-bfcd412a63d6/brazier-v-cherry-brief-of-counsel-for-appellees. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

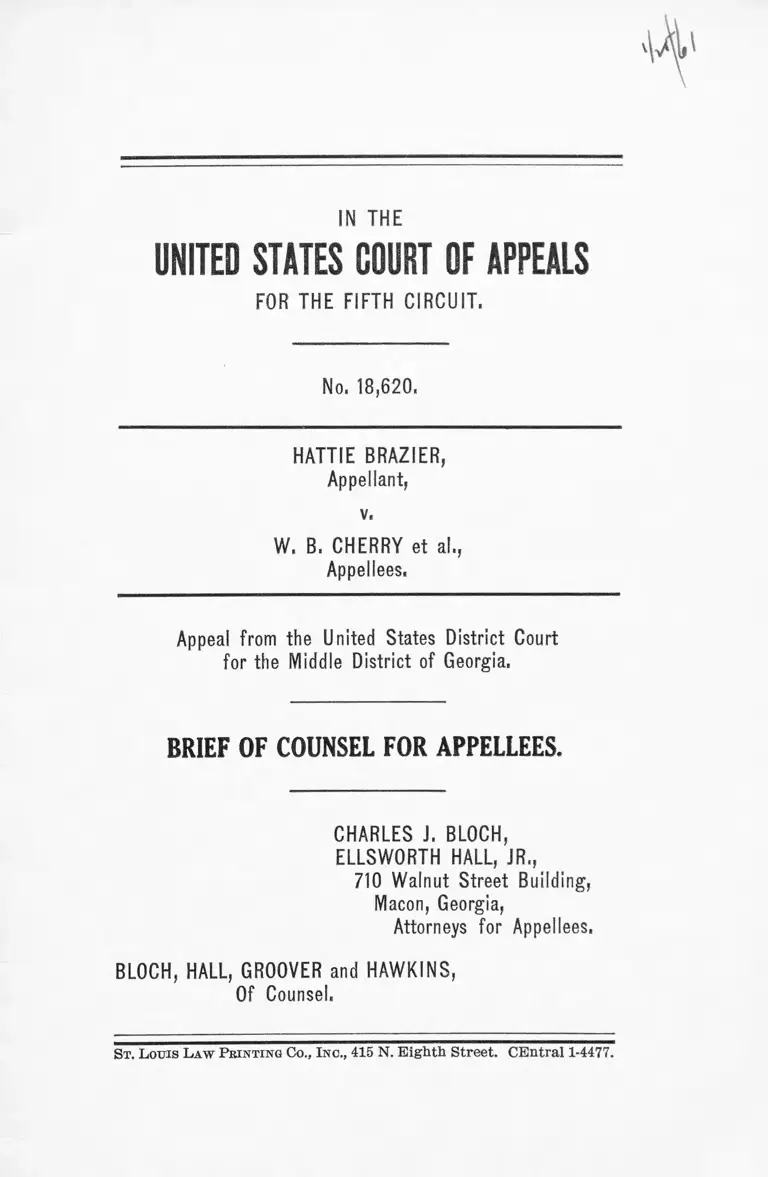

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT,

IN THE

No. 18,620.

HATTIE BRAZIER,

Appellant,

v,

W, B. CHERRY et a!.,

Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia,

BRIEF OF COUNSEL FOR APPELLEES.

CHARLES J, BLOCH,

ELLSWORTH HALL, JR.,

710 Walnut Street Building,

Macon, Georgia,

Attorneys for Appellees.

BLOCH, HALL, GROOVER and HAWKINS,

Of Counsel.

St, L ouis L a w Printing Co., Inc., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX,

[Page

Statement of the ease......................................................... 1

Argument ............................................................................ 7

I. Appellant does not have an action for wrongful

death under Title 42, U. S. C., 1981, 1983 or 1985.

Neither does any one of these sections provide

for a survival to her of any cause of action

which her husband may have had....................... 7

II. The survival provision in § 6 of the Civil Rights

Act of April 20, 1871 (42 U. S. C., § 1986), does

not authorize the institution and maintenance

of the suit at bar................................................ 11

III. Even if § 6 of the act of 1871 (42 U. S. C.,

§ 1986) should be construed to apply to actions

created under § 2 of the Act of 1871 [42 U. S. C.,

§ 1985 (3)], it would not be applicable to the

complaint in this action........................................ 16

IV. Appellant has no right of action under Georgia

wrongful death and survival statutes by virtue

of the provisions of Title 42, U. S. C., Section

1988 .......................................................................... 19

V. Georgia’s Death Statute (§ 105-1302) (appel

lant’s brief, page 14) gives no jurisdiction to the

Federal Courts of this action, diversity being-

absent ...................................................................... 22

VI. The District Court correctly dismissed the com

plaint against the corporate bonding company.. 23

Appendix ............................................................................ 25

CITATIONS.

Cases.

Barnes Coal Corporation v. Retail Coal Merchants

Assn., 128 F. 2d 645....................................................... 20

Cain v. Bowlby, 114 F. 2d 519 (2 ) ................................. 16

Dennick v. Railroad Co., 103 U. S. 11, 21..................... 7

Dyer v. Kazuhisa Abe, 138 F. Supp. 220 (Reversed

on other grounds, 256 F. 2d 728)............................. 21

Frasier v. Public Service Interstate Transportation

Co., 254 Fed. 132, 134..................................................... 10

Goodsell v. Hartforxl R. Co., 33 Conn. 55..................... 8

Hoffman v. Halden, 268 F. 2d 280 (38)......................... 19

In re Stnpp, Fed. Cases No, 13,563, 23 Fed. Cas. at

page 299............................................................................ 21

Lee v. Pure Oil Co., 218 F. 2d 711................................. 8

Martin v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, 151 U. S. 673,

674 .................................................................................... 21

Mejia et al. v. United States, 152 F. 2d 686, 6 8 7 .... 8

Michigan Central R. Co. v. Yreeland, 227 U. S. 59, 57

L. Ed. 417........................................................................ 22

Mobile Life Insurance Company v. Brame, 95 IT. S, 54. 7

Silverman v. Travelers Insurance Company, 277 F. 2d

257, 261 (1960)................................................................ 8

St. L., S. F. & T. R. Co. v. Seale, U. S. C. A., Title 45,

§51, note 1556................................................................ 17

The Harrisburg, 119 LT. S. 199......................................... 8

The Vessel M /V “ Tungus,” etc., et al. v. Skovgaard,

decided February 24, 1959, 358 U. S. 588, 79 S. Ct.

503 .................................................................................... 8

United States v. Bowen, 100 U. S. 508 (1) 513.......... 19

United States v. Durrance et al., 101 F. 2d 109, 110. . 8

United States v. Hirsch, 100 U. S. 33, 35....................... 19

i i

I l l

Statutes.

IT. S. C. A., 1 to 4, pages 3 and 4 ................................. 18

United States Code, Compact Edition, Complete to

December 3, 1928......................................... ................. 18, 20

28 U. S. C., § 1331................................................................ 2

28 U. S. C., § 1343 (1), (2), (3) and (4 ) ............................ 2

28 U. S. C., § 1391 ( c ) ......................................................... 4

28 U. S. C. A., Rule 69..................................................... 20

42 U. S. G., §1981............................................................... 2,5

42 U. S. U, § 1983............................................................... 3,5

42 U. S. C., § 1985 (3 ) .............................. 4,5,6,11,13,14,16

42 IT. S. C., § 1986.......................................... 5,6,11,14,16,17

42 U. S. C., § 1988........................................................ 5,6,19

Constitution.

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment,

Sec. 1................................................................................... 2

Texts.

16 American Jurisprudence, p. 35................................. 7

The Congressional Globe, April 19-20, 1871, p. 804.12,14,15

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT,

IN THE

No, 18,620.

HATTIE BRAZIER,

Appellant,

v,

W, B. CHERRY et al.,

Appellees,

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia,

BRIEF OF COUNSEL FOR APPELLEES.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

This is an appeal from a judgment of the United States

District Court for the Middle District of Georgia sustain

ing a motion to dismiss an action brought in that court

under the Civil Eights Acts. The appellant, individually

and as administratrix of her husband’s estate, sought

damages for his alleged beating by police officer defend

ants, and his consequent death. In the same action she

sought to recover $10,000.00 from the corporate surety for

one of the officers (R. 7).

9

We deem it important to call to the attention of this

Court at the outset the bases upon which jurisdiction of

the District Court was invoked (R. 2-3).

The first basis is Title 28, IT. S. § 1331.

The pertinent portion of this section is:

“ The district courts shall have original jurisdic

tion of all civil actions wherein the matter in contro

versy exceeds the sum or value of $10,000 exclusive

of interest and costs, and arises under the Constitu

tion, laws or treaties of the United States.”

Appellant alleged (R. 2) that this was “ a civil action

arising under the Constitution and laws of the United

States, to wit: The Fourteenth Amendment . . . Section

1, and Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981, wherein

the matter in controversy exceeds the sum of $10,000.00

exclusive of interest and cost.”

The next basis:

Title 42, U. S. C., §1981, is:

“ All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons and property as is enjoyed by wrhite citizens, and

shall be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties,

taxes, licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to

no other.” 1

The jurisdiction of the court was also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1343 (1), (2), (3)

and (4) (R. 2).

l Of that section, the District Judge said in his opinion: “ Section 1981

provides for equal rights under the law, but does not create any civil

action for deprivation o f such rights” (R. 27).

That Section is:

“ The district courts shall have original jurisdiction

of any civil action authorized by law to he com

menced by any person: (1) To recover damages for

injury to his person or property, or because of the

deprivation of any right or privilege of a citizen of

the United States, by any act done in furtherance of

any conspiracy mentioned in Section 1985 of Title 42;

“ (2) To recover damages from any person who

fails to prevent or to aid in preventing any wrongs

mentioned in Section 1985 of Title 42 which he had

knowledge were about to occur and power to prevent;

“ (3) To redress the deprivation, under color of any

State law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or

usage, of any right, privilege or immunity secured

by the Constitution of the United States or by any

Act of Congress providing for equal rights of citizens

or of all persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States.

“ (4) To recover damages or to secure equitable or

other relief under any Act of Congress providing for

the protection of civil rights, including the right to

vote. ’ ’2

It was next stated in the complaint (R. 2): “ This ac

tion is authorized by Title 42, United States Code, Sec

tion 1983 . . . ”

That section provides:

“ Every person who, under color of any statute, or

dinance, regulation, custom, or usage, of any State

or Territory, subjects, or causes to be subjected, any

citizen of the United States or other person within

2 Of that section, the D istrict Judge said in his opinion: “ This section

gives the district courts jurisdiction only o f civil actions ‘authorized by

law to be com m enced.’ Thus, the question arises whether the com plaint

sets forth an action ‘authorized by law to be com m enced’ ” (R. 27).

4 -

the jurisdiction thereof to the deprivation of any

rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Con

stitution and laws, shall he liable to the party injured

in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper

proceeding for redress.” (Emphasis supplied.)3

The jurisdiction of the Court was also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1391 (c) . . .

(R. 3).

That section is:

“ A corporation may be sued in any judicial dis

trict in which it is incorporated or licensed to do busi

ness or is doing business, and such judicial district

shall be regarded as the residence of such corporation

for venue purposes.”

The sole applicability of that section to this case would

be as to the phase of the controversy between the appel

lant and The Fidelity and Casualty Company of New

York, surety for one of the appellees.

Finally, appellant characterizes this action thus:

“ This is an action for redress pursuant to injury

to a citizen by virtue of a conspiracy, whereby a per

son is injured in his person and deprived of having

and exercising rights and privileges as a citizen, for

which damages in this suit are sought against one or

more conspirators” (R. 3).

To support the action thus characterized, she invoked

Title 42, United States Code, Section 1985 (3), the perti

nent portion of which is:

•'i Of this section and Section, 1985 which will be hereinafter alluded to,

the D istrict Judge said in his opinion: “ These sections which create

causes of action to redress deprivations of civil rights vest such causes

o f action in the party injured or deprived. Neither section provides for

the survival o f the right of action after the death of the 'party injured.’

Therefore, this court must answer the question whether, in the absence

of a statutory provision, for survival, a right of action for deprivation of

civil rights is extinguished by the death of the ‘party injured or de

prived’ ” (R. 28).

“ . . . in any case of conspiracy set forth in this

section, if one or more persons engaged therein do,

or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the

object of such conspiracy, whereby another is injured

in his person or property, or deprived of having and

exercising any right or privilege of a citizen of the

United States, the party so injured or deprived may

have an action for the recovery of damages, occa

sioned by such injury or deprivation, against any one

or more of the conspirators.” 4 (Emphasis added.)

We respectfully urge the Court to notice particularly

that neither in her complaint (R. 2-9), nor in the amend

ment thereto (R. 15-19), did the appellant invoke, rely

upon, or even mention Title 42, U. S. C., § 1986, or Title

42, U. 8, C., 1988.

The failure to invoke either of these sections becomes

the more important when the Court perceives that, prior

to the filing of her amendment, we, on behalf of the pres

ent appellees, had filed a motion to dismiss under Rule

12 (b) in which we asserted that the plaintiff had no

cause of action either under the Fourteenth Amendment

standing alone, or under Title 42, U. S. C., § 1981, or

under Title 42, II. 8. C., 1983, or under Title 42, U. S. 0.,

1985 (3) (R. 10-12).

In that motion we contended:

# # # * * * #

(d) The Fourteenth Amendment, standing alone, does

not entitle the plaintiff to recover on the allegations of

her complaint;

(e) Title 42, U. 8. 0., §1981, creates no right of action

in appellant;

(f) The action was not authorized by Title 42, U. S. C.,

§ 1983, for that any right of action which may have been

4 See note 3, supra.

given to Brazier thereby, did not survive or inure to the

benefit of appellant;

(g) The action was not authorized by Title 42, U. S. C.,

§ 1985 (3), for that any right of action which may have

been given to Brazier thereby did not survive and inure

to the benefit of appellant (R. 10-11).

In that motion we explicitly set out that Title 42,

IT. S. C., 1983, and 1985 (3), were derived from the Act of

April 20, 1871, and that “ the only section of that Act

which provides for the survival of any cause of action

upon the death of any party due to alleged wrongful acts

of the nature alleged in the complaint is section 6, now

codified as Title 42, United States Code, Section 1986. If

the plaintiff has any cause of action under that section, it

would be limited to the recovery of $5,000.00 if com

menced within one year after the accrual of the cause of

action. This action was not so commenced” (R. 11-12).

Twenty-one days after we filed that motion, the plain

tiff-appellant filed an amendment to her complaint (R. 13-

19). But- neither in it nor elsewhere prior to the filing of

her brief in this Court did she “ invoke” Title 42, U. S. C.,

§ 1986, or any portion of it.

The Court granted our motion to dismiss the complaint

as amended. The grant was accompanied by an opinion

(R. 25-30).

Ten days later, plaintiff filed a “ Motion for Reconsider

ation” (R. 31-2). In it, she claimed no rights under Title

42, U. S. C., § 1986, or 42 U. S. C., § 1988.

This is true despite the fact that in our reply to the mo

tion for reconsideration, we again called attention to § 6 of

the Act of 1871 (42 U. S. C., § 1986) (R. 34-35).

The Court, two months later (August 11, 1960), filed a

second opinion and order denying appellant’s motion for

reconsideration (R. 39).

— 6 —

■— 7 •—

ARGUMENT,

T.

Appellant does not have an action for wrongful death

under Title 42, U. S. C., 1981, 1983 or 1985. Neither does

any one of these sections provide for a survival to her of

any cause of action which her husband may have had.

It is a general rule of the common law that no action

will lie to recover damages for the death of a human

being occasioned by the negligent, or other wrongful, act

of another, however close may be the relation between the

deceased and the plaintiff' and however clearly the death

may involve pecuniary loss to a plaintiff.5

The earliest expression of this rule by the Supreme

Court of the United States seems to have been in 1877 in

the case of Mobile Life Insurance Company v. Brame, 95

U. S. 54. There at page 56, the Court said:

“ The authorities are so numerous and so uniform

to the proposition that by the common law no civil

action lies for an injury which results in death, that

it- is impossible to speak of it as a proposition open to

question. ’ ’

And at page 759, is this statement: “ By the common

law, actions for injuries to the person abate by death, and

cannot be revived or maintained by the executor or the

heir.”

Three years later the Court said: “ The right to recover

for an injury to the person, resulting in death, is of very

recent origin, and depends wholly upon statutes of the

different States.”

Dennick v. Railroad Co., 103 U. S. 11, 21.

r> 16 Am erican Jurisprudence, p. 35.

-— 8 —

This Court is, of course, fully cognizant of the principle

having applied it frequently, e. g .:

In United States v. Durrance et ah, 101 F. 2d 109, 110:

“ Therefore, in cases like this, the right of recovery is

entirely dependent upon statutory law.”

In Mejia et al. v. United States, 152 F. 2d 686, 687, “ The

right to claim damages for death exists by statutory pro

visions alone.”

In Silverman v. Travelers Insurance Company, 277 F.

2d 257, 261 (1960): “ In the common law there was no

right of action for wrongful death.”

In The Vessel M/V “ Tungus,” etc., et al. v, Skovgaard,

decided February 24, 1959, 358 U. S. 588, 79 S. Ct. 503,

Justice Stewart, writing for the majority, began “ as did

the Court of Appeals with the established principle of

maritime law that in the absence of a statute there is no

action for wrongful death.”

He cited The Harrisburg, 119 U. S. 199—one of the

foundation stones. It had cited Goodsell v. Hartford R.

Co., 33 Conn. 55, in which the Court had said:

“ It is a singular fact, that by the common law

the greatest injury which one man can inflict on an

other, the taking of his life, is without a private

remedy. ’ ’

Justice Stewart, while on the United States Court of

Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, had written for the Court

in Lee v. Pure Oil Co., 218 F. 2d 711, and said:

“ The right to recover for wrongful death exists, if

it exists at all, by virtue of some statute, state or

federal. ’ ’

For this action to have been maintained in the Federal

Court there must have been a federal statute giving the

appellant a cause of action for the alleged wrongful death

of her husband. The District Judge said there was none

(R. 29) and hence dismissed the action (R. 30).

Counsel for the appellant filed their motion for recon

sideration bringing “ to the court’s attention for the first-

time in their brief submitted with their motion for recon

sideration a decision by Judge John P. Barnes, Chief

Judge of the United States District Court for the North

ern District of Illinois holding that ‘ party injured’ as

used in Section 1983 includes the administratrix of the

estate of one who was killed in violation of that section.

Davis v. Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572 (N. D. 111. 1955)” (R.

31; R. 39-40).

We filed a reply to this motion and to the brief with

respect to it. That reply appears in the record in full

(R. 32-39) so there appears no need to burden this brief

with a repetition of all that was said there.

Again the District Judge wrote an opinion (R. 39-43)

and denied the motion for reconsideration. In the course

of it he used these cogent sentences: “ The plaintiff, ad

mitting that there is no specific survival provision in the

civil rights act, claims that, as the result of a personal

tort committed against her husband resulting in his death,

her property has been injured. If she were legally cor

rect there would be no need for wrongful death statutes”

(R. 43).

In her brief here (pages 9-12), appellant reiterates this

position. She, referring to Section 1985 (3), continues to

assert that Congress had one situation in mind when it

used the phrase “ the party so injured or deprived.” As

the trial judge said: “ If she were legally correct there

would be no need for wrongful death statutes.”

She is seeking from this court not adjudication but

legislation.

— 9 •—-

10

She argues that “ every American jurisdiction has either

a wrongful death or survival statute . . . Indeed, the

prevalence of these statutes is so widespread that they

may now be said to constitute the general law.”

She would have the courts amend the civil rights acts

by adding to them what she considers to constitute the

“ general law.”

In Frasier v. Public Service Interstate Transportation

Co., 254 Fed. 182, 134, Judge Medina speaking for the

Court said:

“ The common law did not recognize any cause of

action arising from the death of a person due to the

negligent or wilful act of another, . . . but statutes

collected in note, 39 Iowa L. Rev. 494, 495, n. 5 (1954),B

and constitutional provisions adopted in some of the

states, see 16 Am. Jur., Death, § 51, have created a

right to sue and recover damages based on such a

wrongful death. . . . Similarly, the state statutes

creating an action for wrongful death differ in many

respects, the most important differences being found

in their provisions regarding who may bring the

action, the time limitation . . ., the method of

measuring damages, and the limitation on the amount

of damages reasonable . . . Because of the differ

ences among the state statutory provisions regarding

the damages recoverable in a wrongful death action,

the amount actually recovered is often dependent upon

the statute under which the action is brought.”

Under what statute is this action brought?

She brings it individually and as administratrix of the

estate of James Brazier (E. 2).

What statute authorizes such?

« This is cited at page 9 of appellant’s brief.

— 11 —

She first sued for $170,448.00 (R. 4). By amendment

she increased that figure to $180,448.00 (R. 16-17).

She first sued for $120,448.00 for “ General Damages”

(R. 7). She amended so as to ask $10,000.00 additional

for the “ injuries upon the head, scalp and body of the

said James C. Brazier” (R. 18).

She sued for “ Smart Damages” in the sum of $50,000.00

(R. 14) (R. 19).

What, statute authorizes any such damages? What stat

ute authorizes the “ reasonable attorney’s fees for which

she sues” ? (R. 7, par. 15.)

II.

The survival provision in § 6 of the Civil Rights Act of

April 20, 1871 (42 U. S. C., § 1986), does not authorize the

institution and maintenance of the suit at bar.

Appellant’s counsel now argue: “ The survival provision

of § 1986 was intended by the framers also to cover Sec

tion 1985 as the legislative history clearly reveals.”

Before disputing and debating that premise let us say

that no such contention was made in the court below. The

District Judge decided the case on the basis of the plain

tiff having admitted “ that there is no specific survival

provision in the civil rights act.” Now the plaintiff-

appellant contends that the survival provision of § 6 of the

Act (Title. 42, U. S. C., §1986) applies to actions under

§ 2 of the Act [Title 42, U. S. G, 1985 (3)].

Some of counsel for the appellant here were of counsel

for appellees in Board of Supervisors, etc., v. Ludley et al.,

252 P. 2d 372, wherein this court said: “ Moreover, this

point was not urged in the court below and need not be

considered on this appeal” (op. cit. p. 377).

That decision, and those upon which it is based, per

haps will dispose of this contention of appellant.

We are not content to rest our opposition to it on that

basis alone.

The legislative history of the 1871 Civil Rights Act is

extensive.

It reveals that this Act had its origin in H. R. No. 320—•

42nd Congress. On April 20, 1871, the Senate and House

were in disagreement. One of the causes of the disagree

ment was what was called the “ Sherman amendment.” 7

It sought to impose liability on towns and counties in

certain events. There was no question “ before the House”

as to any survival provision or as to the creation of any

right of action in the event of the death of the person

injured or deprived (The Congressional Globe, April 19-

20, 1871, p. 804). Representative Poland rose “ for the

purpose of making a privileged report.” He presented

the report of conference on the disagreeing votes of the

two Houses on House bill No. 320.

In it, it was proposed “ that the two Houses agree to a

substitute for the twenty-first Amendment of the Senate,

as follows:

7 The Sherman Am endm ent was as follow s:

“ That if any house, tenement, cabin, shop, building, barn, or granary

shall be unlawfully or feloniously dem olished, pulled down, burned, or

destroyed, wholly or in part, by any persons riotously and tumultuously

assem bled together; or if any person shall unlawfully and with force and

violence be whipped, scourged, wounded, or killed by any persons riot

ously and tumultuously assem bled together; and if such offense was com

mitted to deprive any person o f any right conferred upon him by the

Constitution and laws of the United States, or to deter him or punish him

for exercising such right, or by reason of his race, color, or previous

condition of servitude, in every such case the inhabitants of’ the county,

city, or parish in which any of the said offenses shall be com m itted shall

be liable to pay full com pensation to the person or persons damnified by

such offense if living, or to his w idow or legal representative if dead;

and such com pensation may be recovered by such person or his repre

sentative by a suit in any court o f the United States of com petent juris

diction in the district in which the offense was com m itted, to be in the

name of the person injured, or his legal representative, and against said

county, city, or parish. And execution may be issued on a judgm ent ren

dered’ in such suit and may be levied upon any property, real or per

sonal, of any person in said county, city or parish, and the said county,

city, or parish may recover the full amount o f such judgment, costs and

interest, from any person o r persons engaged as principal or accessory

in such ’ riot in an action in any court of com petent jurisdiction .”

— 13 -

“ Sec. 6. And be it further enacted That any person or

persons having knowledge that any of the wrongs con

spired to be done and mentioned in the second section of

this act are about to be committed, and having power to

prevent or aid in preventing the same, shall neglect or

refuse so to do, and such wrongful act shall be committed,

such person or persons shall be liable to the person in

jured, or his legal representatives, for all damages caused

by any such wrongful act, which such first-named person

or persons by reasonable diligence could have prevented;

and such damages may be recovered in an action on the

case in the proper circuit court of the United States, and

any number of persons guilty of such wrongful neglect or

refusal may be joined as defendants in such action: Pro

vided, that such action shall be commenced within one

year after such cause of action shall have accrued. And

if the death of any person shall be caused by any such

wrongful act and neglect, the legal representatives of such

deceased person shall have such action therefor, and may

recover not exceeding $5,000 damages therein for the ben

efit of the widow of such deceased person, if any there be;

but if there be no widow, for the benefit of the next of

kin of such deceased person.” (Emphasis added.) (Ibid,

p. 804.)

At the outset let it be noted that the proposed section

6 in the language first hereinabove emphasized creates by

its very words a liability to the person injured or his legal

representative. On the contrary, section 2 of the act, now

codified as Title 42, U. S, C., 1985 (3) creates a right of

action only in favor of “ the party so injured or deprived”

omitting any mention there of the personal representative

of the party so injured or deprived.

Furthermore in section 6 the right of action created

in favor of legal representatives depends upon death hav

ing been caused not merely by “ any such wrongful act”

but by “ any such wrongful act and neglect” .

— 14

In section 2 as it appears in Chapter XXII, Forty-Second

Congress, Sess. 1, there is no right of action created except

in “ the person so injured or deprived” . In section 6, the

right is given to person injured or his legal representative.

(In an amount not exceeding Five Thousand Dollars.)

In the United States Code of 1926, section 2 appears as

Title 8, § 47. The only right of action conferred is on the

“ party so injured or deprived” . Section 6 appears as

Title 8, § 48. It follows the language of the 1871 act, and

continues the right of action under it, for the wrongful

act and neglect, not only in favor of party injured but also

in favor of his legal representatives. (Still limited in

amount to $5,000.00.)

These differences continue to this day as the act is codi

fied in Title 42, United States Code. Title 42, U. S. C.,

1985 (3) vests the right of action only in “ the party so

injured or deprived” ; Title 42, U. S. C., 1986 continues

the right of action (in an amount not. exceeding $5,000.00

damages) in the party injured, or his legal representative

if the death “ be caused by any such wrongful act and

neglect. ’ ’

Representative Poland made no mention in his state

ment of any reason for permitting a right in personal rep

resentatives in Section 6 actions but not in section 2 ac

tions.8 He did not refer to or discuss the subject.

Our investigation of the legislative history of section 6

was prompted by a purported quotation from the Congres

sional Globe of remarks of Representative Shellabarger,

appearing on page 7 of appellant’s brief. The first eighteen

words of the quotation are: “ That if the death of a party

shall be occasioned, there shall still be a right of action.”

These words do not form a complete grammatical sentence.

Hence, we wondered. Fortunately, we had access, too, to

8 In the opinion o f the D istrict Judge (R . 42) the trial judge treats of

possible reasons for the differentiation.

this volume of the Congressional Globe. The Congres

sional Globe discloses that during Mr. Poland’s presenta

tion, Mr. Cox queried: “ How do you propose to measure

damages for presumed neglect!” During Mr. Shellabarg-

er’s remarks (p. 805) he said: “ Now, here my friend from

New York (Mr. Cox) asked how the damages should be

measured, and somebody replied, ‘ Let them be measured

in a hat.’ But there is one method of measuring damages,

as it exists in our State, to wit: that if the death of a party

shall be occasioned there shall still be a right of action.”

(Emphasis added.) That is the context of the eighteen

words. Then followed the balance of the quotation as it

appears on pages 7 and 8 of appellant’s brief in which he

gave his “ interpretation” — “ that this language operates

back upon the second section.” He was apparently not

questioned on the subject, and therefore he was not faced

with the utter differences between the language of the

second section and the language of the sixth to which

differences we have alluded.

The conference committee report was agreed to—yeas

93, nays 74, not voting 63 (Op. cit. p. 808).

The author of appellant’s brief deems the enactment of

the proposed legislation to have been a sustaining of Rep

resentative Shellabarger’s position. We daresay that what

the Representative was talking about when he said, “ 1

do not know that I will be sustained in that, that this

language (referring to the language of survival) operates

back upon the second section [1985]),” was a “ sustain

ing” by the courts.

His language denotes a doubt even in his mind as to his

opinion. No one else seems to have discussed that par

ticular question at that time.* It comes up now 90 years

later for apparently its first adjudication in court. We

* W e have not examined the entire volum e of the Congressional Globe.

— 16 —

respectfully submit that in adjudicating it, the Court

should give heed to those features which show the utter

differences in the language used by Congress in § 2 and

§6. Not only that but also—the statute is in derogation

of the common law and is therefore to be construed strictly.

Cain v. Bowlby, 114 F. 2d 519 (2).

ITT.

Even if § 6 of the act of 1871 (42 U, S. 0., § 1986) should

he construed to apply to actions created under § 2 of the

Act of 1871 [42 U. S. C., § 1985 (3)], it would not be ap

plicable to the complaint in this action.

Even if § 6 should be construed to apply to § 2, it would

not save the complaint in this action.

Praetermitting any present discussion of whether the

action must have been commenced within one year after

the cause of action accrued, it is perfectly clear that under

section 6 “ if the death of any person shall be caused by

any such wrongful act and neglect, the legal representa

tives of such person shall have such action therefor, and

may recover not exceeding five thousand dollars damages

therein, for the benefit of the widow of such deceased per

son, if any there be, or if there be no widow, for the bene

fit of the next of kin of such deceased person.”

Therefore, if there is any right of action for death oc

casioned by the injury alluded to in § 2, that right of action

is a statutory one, the complainant must be the personal

representative of the deceased, and damages are limited

to $5,000.00.

To paraphrase the language of Judge Hutcheson in

Roth v. Cox, 210 F. 2d 76, 81, if section 6 is now invoked,

must not the appellant ‘ ‘ take the statutory cause of action

cum onere, the bitter with the sweet” ?

-— 17 -

Even if these latest contentions of counsel for the appel

lant as to the application of § 6 to § 2 are correct, the

right of action which would thereby be created would be

one not declared upon by appellant nor relied upon in her

complaint. On the contrary, the complaint is brought by

Hattie Brazier, Individually and as Administratrix of the

estate of James Brazier, plaintiff. It seeks damages of

every conceivable nature plus attorneys’ fees (E. 7).

The situation may be analogized in some respects to a

suit under the Federal Employers’ Liability Act. Where

it is applicable, no one but the personal representative

can maintain the action, and the damages recoverable are

only those permitted by the statute.

St. L., S. F. & T. B, Co. v. Seale, U. S. C. A., Title 4b,

§ 51, note 1556.

We have thus far praetermitted any discussion of the

statute of limitations which is a part of the right of action

created by § 6 of the 1871 Act.

Of it, counsel for the appellant say in their brief: “ It

will be noted that the sentence following the survival pro

vision contains a one year statute of limitation. This,

however, refers to the section and not to the act, other

portions of which have been held to be controlled by the

appropriate state statute of limitation. See O’Sullivan v.

Felix, 233 U. S. 318; Johnson v. Yeilding, 165 F. Supp. 76.”

(Footnote, page 8)

The phrase “ this section” occurs in the codification of

§ 6 of the 1871 act (42 U. S. C., § 1986). It does not ap

pear in the original act. Section 6 of the original act

creates the liability for wrongful act and neglect and then

has this proviso: “ Provided, That such action shall be

commenced within one year after such cause of action shall

have accrued; and if the death of any person shall be

— 18 —

caused by any such wrongful act and neglect, the legal rep

resentatives of such deceased person shall have such action

therefor, and may recover not exceeding live thousand

dollars damages therein, for the benefit of the widow of

such deceased person, if any there be, or if there be no

widow, for the benefit of the next of kin of such deceased

person” (Emphasis added).

If the proviso should be carried forward so as to permit

a right of action for death under § 2, there must be carried

forward with it all limitations and provisions contained

in the proviso of the original act. (The original act ap

pears in full in the Appendix hereto.)

The Code of the Laws of the United States of America

(United States Code) was adopted by an act passed by the

Sixty-ninth Congress entitled “ An Act to Consolidate,

Codify and Set Forth the general and permanent laws of

the United States in force December seventh, one thousand

nine hundred and twenty-five.” That act appears in full

in U. S. C. A. 1 to 4, pages 3 and 4, and United States

Code, Compact Edition, complete to December 3, 1928,

page (1).

It provides in part:

“ In case of any inconsistency arising through omis

sion or otherwise between the provisions of any

section of this Code and the corresponding portion of

legislation heretofore enacted effect shall be given for

all purposes whatsoever to such enactments.”

That enactment is a legislative declaration of what the

Supreme Court had previously said with respect to the

older compilation known as the “ Revised Statutes,” to

w it:

“ It must be admitted that in construing any part

of the Revised Statutes it is admissible, and often

19 —

necessary, to recur to its connection in the act of which

it was originally a part.”

United States v, Hirsch, 100 IT. S. 33, 35.

The Court may recur to the original statutes “ when

necessary to construe doubtful language used in the re

vision. ’ ’

United States v. Bowen, 100 IT. S. 508 (1) 513.

So, even if the court should deem section 6 applicable

to section 2, there would thereby be created a statutory

action for death to be instituted by the personal represent

ative of the deceased within one year after the cause of

action accrued, with recovery limited to live thousand

dollars. The action under review meets no one of the

tests.9

We have not overlooked Hoffman v. Halden, 268 F. 2d

280 (38) which we do not deem controlling. The court

there said: “ The problem of the statute of limitations is

very much in the case . . . neither appellant nor respond

ents have adequately analyzed or briefed the problems

pertaining to such issue.”

Additionally, the question at issue here was not an issue

there.

IV.

Appellant has no right of action under Georgia wrongful

death and survival statutes by virtue of the provisions of

Title 42, U. S. C., Section 1988.

That section is set out in full at page 13 of appellant’s

brief. It is derived from Acts April 9, 1866, c. 31, §3, 14

Stat. 27; May 31, 1870, c. 114, § 18, 16 Stat. 144.

9 James Brazier’s injuries were allegedly sustained April 20-21, 1958

(Complaint, § 7, R. 5 ); he died April 25, 1958 (R. 4 ); the action was insti

tuted April 19, 1960 (R. 2).

— 20

In the “ United States Code, Compact Edition, complete

to December 3, 1928“ it appeared as Title 28, § 729 under

Chapter 18—Procedure. It so remained in the 1946 Edition

of the United States Code. That this section does not en

compass substantive rights but merely procedural matters

may be demonstrated by the note of the Advisory Com

mittee under Rule 69, 28 U. S. C. A.

The section does not create a right of action. It merely

provides for the enforcement of such rights of action and

causes of action as may have been created by the Congress.

In Barnes Coal Corporation v. Retail Coal Merchants

Assn., 128 F. 2d 645, at page 649, Circuit Judge Parker

speaking for the court said:

“ . . . it is well settled that with respect to a cause

of action created by act of Congress, the question of

survival is not one of procedure but one which depends

‘ on the substance of the cause of action.’ Schreiber

v. Sharpless, 110 U. S. 76, 80, . . .; Martin’s Admr.

v. Baltimore & 0. R. Co., 151 U. S. 673, 692 . . . And,

unless the cause of action as so created by Act of Con

gress survives, it does not survive by reason of state

law. Michigan Central R. Co. v. Vreeland, 227 U. S.

59, 67; 33 S. Ct. 192, 57 L. Ed. 417; . . . ” (Emphasis

added).

In the Schreiber case, supra, at page 80, the court said:

“ If the cause of action survives, the practice, pleadings

and forms and modes of proceedings in the courts of the

State may be resorted to in the courts of the United States

for the purpose of keeping the suit alive and bringing in

the proper parties. Rev. Stat. § 914. But if the cause of

action dies with the person, the suit abates and cannot be

revived” (Emphasis supplied).

“ The question whether a cause of action survives

to the personal representative of a deceased person,

— 21 —

is a question not of procedure, but of right; and,

when the eause of action does not arise under a law

of the United States, depends upon the law of the

State in which the suit is brought.”

Martin v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, 151 U. S.

673, 674 (Emphasis added).

It follows that if the cause of action does arise under a

law of the United States, the question of survival does not

depend upon the law of the State in which the suit is

brought.

It follows, too, that if the cause of action involved in the

complaint here does not arise under a law of the United

States, the Federal Court in which it was instituted had no

jurisdiction.

“ Congress does not have to provide a federal forum

for every statutory right it creates, but recovery or

relief cannot be had in Federal District Court under

the Civil Rights Act without existence of jurisdictional

basis in statute defining original jurisdiction of the

Federal District Courts. 28 U. S. C. A.., §1343 (3),

42 U .S .C . A., §1983.”

Dyer v. Kazuhisa Abe, 138 F. Supp. 220 (Reversed

on other grounds, 256 F. 2d 728).

At pages 228-9 of the opinion in the case just cited is:

“ . . . Fourteen Stat. 27, as amended, 42 U. S. C. A., § 1988,

does not aid plaintiff in this regard. It has reference to

procedure, not jurisdiction.”

“ . . . section 722 (now Title 42, U. S. C., § 1988)

manifestly has reference not to the rules of decision,

but to the forms of process and remedy.”

In re Stupp, Fed. Cases No. 13,563, 23 Fed. Cas.

at page 299.

— 22 —

y .

Georgia’s Death Statute (§ 105-1302) (appellant’s brief,

page 14) gives no jurisdiction to the Federal Courts of

this action, diversity being absent.

This proposition is squarely decided by the Supreme

Court in Michigan Central R. Co. v. Vreeland, 227 U. S.

59, 57 L. Ed. 417, which we cited to the District Judge. In

his original opinion in this case, he quotes from it:

“ The statutes of many of the states expressly pro

vide for the survival of the right of action which the

injured person might have prosecuted if he had sur

vived. But unless this Federal statute which declares

the liability here asserted provides that the right of

action shall survive the death of the injured employee,

it does not pass to his representative, notwithstanding

state legislation. The question of survival is not one

of procedure, ‘ but one which depends on the substance

of the cause of action’ . . . Nothing is> better settled

than that, at common law, the right of action for an

injury to the person is extinguished by the death of

the party injured. The rule, ‘ actio personalis moritur

cum persona’ applies, whether the death from the

injury be instantaneous or not” (R. 28-29).

The District Judge was quoting from page 67 of the

opinion.

The fourth headnote of this opinion as it appears 227

U. 8. 59, is: “ A Federal statute upon a subject exclusively

under Federal control must be construed by itself and

cannot be pieced out by state legislation. If a liability does

not exist under the Federal Employers’ Liability Act of

1908, it does not exist, by virtue of any state legislation on

the same subject.”

In their discussion of this phase of the case, counsel for

the appellant have not even alluded to the Vreeland case.

It is apt and controlling.

— 23 —

VI.

The District Court correctly dismissed the complaint

against the corporate bonding company.

It is not alleged that the bonding company was guilty of

any violation of any Civil Eights Act with respect to

James Brazier.

Therefore any right which the plaintiff may have to sue

the bonding company in the Federal Court arises from the

diversity jurisdiction of the court.

With respect to that issue, the District Judge said in

his opinion:

“ Plaintiff also attempts to invoke the diversity

jurisdiction of this court, alleging that defendant

Fidelity and Casualty Company of New York is a

New York corporation. But this court does not have

diversity jurisdiction unless all defendants are citizens

of states diverse from the state of plaintiff’s citizen

ship. Russell v. Basila Mfg. Co., 246 F. 2d 432 . . .

It affirmatively appears from plaintiff’s complaint that

plaintiff is a citizen of Georgia, and the individual

defendants, being public officers of Dawson or Terrell

County, Georgia, are obviously citizens of this state

also. Therefore, diversity jurisdiction is lacking. Even

if Fidelity and Casualty Company of New York were

the sole defendant named, the court would still lack

jurisdiction for the reason that plaintiff’s complaint

affirmatively shows that the bond executed by Fidel

ity as surety is limited to $10,000, while the jurisdic

tional amount required in a diversity action is more

than $10,000” (R, 29-30).

While appellant’s brief asserts (p. 17) that the District

Court wrongfully dismissed the complaint against the cor

porate bonding company, and her assertion is briefly dis-

— 24

cussed, there is nothing in it to warrant a different con

clusion from that reached by the District Court, bolstered

by the authority cited.

We respectfully assert that, the judgment of the Court

below was correct and should be affirmed.

ELLSWORTH HALL, JR.,

710' Walnut Street Building,

Macon, Georgia,

Attorneys for Appellees.

BLOCH, HALL, GROOVER & HAWKINS,

Of Counsel.

This is to certify that I have this day served copies of

this brief on (1) Donald L. Hollowell, Esq., (2) C. B. King,

Esq., (3) Jack Greenberg and Tliurgood Marshall, Esq.,

by mailing copies to them by first class mail, postage pre

paid, addressed to them at the following addresses re

spectively :

(1) Cannolene Building (Annex)

859% Hunter Street, N. W.

Atlanta, Georgia

(2) 221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

(3) 10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Certificate of Service.

T h is ..........day of January, 1961.

— 25 —

F O R T Y -S E C O N D CONGRESS. Sess. I. Ch . 22. 1871. 13

a re United States,

&c.;

CHAP. XXII. — An Act to enforce the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the April 20, 1871.

Constitution of the United States, and for other Purposes. Any person

Be it enacted by the Senate and House o f Representatives o f the United any ĥiw.'&V.'of

States o f America in Congress assembled, That any person who, tinder any State, de

color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage o f any o?«nygright &e

State, shall subject, or cause to be subjected, any person within the secured by the

jurisdiction of the United States to the deprivation of any rights, privi- ^ n(jj1,i't1' i(°n of

leges, or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United States, states,"made

shall, any such law, statute, ordinance, regulation, custom, or usage of liable to the pnr-

the State to the contrary notwithstanding, be liable to the party injured typ"^eedingsto

in any action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for be in the courts

redress ; such proceeding to be prosecuted in the several district or cir- °f 5ilc United

cuit courts of the United States, with and subject to the same rights of St̂ 6' c[li 81

appeal, review upon error, and other remedies provided in like cases in Vol. xiv. p. sr.

such courts, under thSL.provisi.ons o f the act o f the ninth of April, eigh- 1>en“ !,y !?r

teen hundred and sixty-six, entitled “ An act to protect all persons m the force to put

United States in their civil rights, and to furnish the means of their vin- down thezovern-

dication ” ; and the other remedial laws of the United States which — me,lt ot tlle

in their nature applicable in such cases.

Sec. 2. That if two or more persons within any State or Territory of , or t0 hm!ier ,TT . , ... . , ‘ J J the execution ofthe United Mates shall conspire together to overthrow, or to put down, any law of the

or to destroy by force the government of the United States, or to levy United States;

war against the United States, or to oppose by force the authority of the propertyTf'the7

government of the United States, or by force, intimidation, or threat to United States;

prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States, or 10 Prev!:nt

or by force to seize, take, or possess any property of the United States hofd,ngTfflcc7m

contrary to the authority thereof, or by force, intimidation, or threat to under the

prevent any person from accepting or holding any office or trust or place f|5uc#

of confidence under the United States, or from discharging the duties any officer to

thereof, or by force, intimidation, or threat to induce any officer of the leave the Sta,ei

United States to leave any State, district, or place where his duties as or to injure

such officer might lawfully he performed, or to injure him in his person him in person or

or property on account of his lawful discharge of the duties o f his office, F'mPer,-v

or to injure his person while engaged in the lawful discharge of the duties TCntghb"don%

of his office, or to injure his property so as to molest, interrupt, hinder, his duty;

or impede him in the discharge o f his official duty, or by force, intimida-

tion, or threat to deter any party or witness in any court of the United witness from at-

States from attending such court, or from testifying in any matter pend-

ing in such court fully, freely, and truthfully, or to injure any such party 1 y"18 ert’

or witness in his person or property on account o f his having so attended or to injure

or testified, or by force, intimidation, or threat to influence the verdict,

presentment, or indictment, o f any juror or grand juror in any court of fying;

the United Slates, or to injure such juror in his person or property on “ infloenco

account of any verdict, presentment, or indictment lawfully assented to a„y juror*;* **'

by him, or on account of his being or having been such juror, or shall or to injure

conspire together, or go in disguise upon the public highway or upon the couitof hisacts"

premises of another for the purpose, either directly or indirectly, o f de- &o. ’

priving any person or any class of persons of the equal protection of the Penalty for

laws, or of equal privileges or immunities under the laws, or for the pur- go!,*| m îsguise

i ipse of preventing or hindering the constituted authorities of any Stale upon the publio

from giving or securing to all persons within such State the equal pro- highway, &c. t»

teetion of the laws, or shall conspire together for the purpose o f in any tonor clots of*"

manner impeding, hindering, obstructing, or defeating the due course o f equal rights, &e.

justice in any State or Territory, with intent to deny to any citizen o f the ^o^to prevent’

United States the due and equal'protection of the laws, or to injure any the State au-

person in his person or his property for lawfully enforcing the right o f ! rotectTr.̂ oJl in

any person or class of persons to the equal protection of the laws, or by their equal0 ”

force, intimidation, or threat to prevent any citizen of the United States rights,

lawfully entitled to vote from giving his support or advocacy in a lawful °̂rob_

struct, &c. the

14 FORTY-SECOND CONGRESS. Sess. I. Cn. 22. 1871.

due course of

justice, &c. in

any State with

intent to deny to

any citizen his

equal rights

under the law;

or, by force,

fee. to prevent

any citizen en

titled to vote

from advocating

in a lawful man

ner the election

ofanv person,

as, &c.

Courts.

Punishment.

Any conspira

tor doing, &c.

any act in fur

therance of the

object o f the

conspiracy, and

thereby injuring

another, to be

liable in dam

ages therefor.

Proceedings to

ba in courts of

the United

States.

1866, ch. 81.

Yol. xiv. p. 27.

What to be

deemed a denial

<by any State to

any class of its

people o f their

equal protection

uuder the laws.

When the due

execution o f the

laws, &c. is ob

structed by vio

lence, &c. the

President shall

do what he may

deem necessary

to suppress

such violence,

See.

Persons ar

rested to be de

livered to the

m irshal.

What unlaw

ful combinations

to be deemed a

rebellion against

the government

o f the United

States.

manner towards or in favor o f the election o f any lawfully qualified per

son as an elector of President or Vice-President ot the United Slates,

or as a member of the Congress of the United States, or to injure any

such citizen in his person or property on account of such support or advo

cacy, each and every person so offending shall he deemed guilty o f a

high crime, and, upon conviction thereof in any district or circuit court

of the United States or district or supreme court of any Territory of the

United Slates having jurisdiction of similar offences, shall be punished by

a line not less than live hundred nor more than five thousand dollars, or

by imprisonment, with or without hard labor, as the court may determine,

for a period of not less than six months nor more than six years, as the

court may determine, or by both such fine and imprisonment as the court

shall determine. And if any one or more persons engaged in any such

conspiracy shall do, or cause to be done, any act in furtherance of the

object of such conspiracy, whereby any person shall be injured in his

person or property, or deprived of having and exercising any right or

privilege of a citizen of the United States, the person so injured or

deprived of such rights and privileges may have and maintain an action

for the recovery of damages occasioned by such injury or deprivation of

rights and privileges against any one or more of the persons engaged in

such conspiracy, such action to he prosecuted in the proper district or

circuit court of the United States, with and subject to the same rights

of appeal, review upon error, and other remedies provided in like cases

in such courts under the provisions of the act of April ninth, eighteen

hundred and sixty-six, entitled “ An act to protect all persons in the

United States in their civil rights, and to furnish the means of their

vindication.”

S ec. 3. That in all cases where insurrection, domestic violence, un

lawful combinations, or conspiracies in any State shall so obstruct or

hinder the execution of the laws thereof, and of the United States, as

to deprive any portion or class of the people of such State of any of the

rights, privileges, or immunities, or protection, named in the Constitution

and secured by this act, and the constituted authorities of such State

shall either be unable to protect, or shall, from any cause, fail in or re

fuse protection of the people in such rights, such facts shall be deemed a

denial by such State Of the equal protection of the laws to which they are

entitled under the Constitution o f the United States; and in all such

cases, or whenever any such insurrection, violence, unlawful combination,

or conspiracy shall oppose or obstruct the laws o f the United States or

the due execution thereof, or impede or obstruct the due course of justice

under the same, it shall be lawful for the President, and it shall be his

duty to take such measures, by the employment o f the militia or the

land and naval forces of the United States, or o f either, or by other

means, as he may deem necessary for the suppression of such in-merec

tion, domestic violence, or combinations; and any person who .-ball be

arrested under the provisions of this and the preceding section shall he

delivered to the marshal of the proper district, to be dealt with according

to law.

S ec. 4. That whenever in any State or part of a State the unlawful

combinations named in the preceding section of this net shall be organ

ized and armed, and so numerous and powerful as to be abba by vio

lence, to either overthrow or set at defiance the constituted authorities

of such State, and of the United States within such State, or when the

constituted authorities are in complicity with, or shall connive at the

unlawful purposes of, such powerful and armed combinations; and

whenever, by reason of either or all of the causes aforesaid, the convic

tion of such offenders and the preservation of the public safety shall be

come in such district impracticable, in every such case such combina

tions shall be deemed a rebellion against the government of the United

FORTY-SECOND CONGRESS. S ess. I. Ch. 22. 1871. 15

Slates, and during the continuance of such rebellion, and within the

limits of the district which shall be so under the sway thereof, such limits witlfin êrtain

to be prescribed by proclamation, it shall be lawful for the President of limits, thePreai-

the United States, when in his judgment the public safety shall require <**”)jr{jjf4rit of

it, to suspend the privileges of the writ of habeas corpus, to the end that Kbe»*'rarpu*0

such rebellion may he overthrown : Provided, That all the provisions of Provision* of

the second section of an act entitled “ An act relating to habeas corpus, *ggg cj, gj ̂2

and regulating judicial proceedings in certain cases,” approved March Vol.’xii. p.’76ti’

third, eighteen hundred and sixty-three, which relate to the discharge of made applicable

prisoners other than prisoners of war, and to the penalty for refusing to 11 pr0(jamatinn

obey the order of the court, shall be in full force so far as the same are to be fir»t made,

applicable to the provisions of this section: Provided further, That the &y o, . 424

President shall first have made proclamation, as now provided -by law, Vol. xii. p” 282.

commanding such insurgents to disperse : And provided also, That the S « PP s-w-wn.

provisions of this section shall not be in force after the end of the next notto*tMbn°tirce

regular session of Congress. after, &c.

S ec. 5. That no person shall be a grand or petit juror in any court of

the United States upon any inquiry, hearing, or trial of any suit, pro- Certain per-

ceeding, or prosecution based upon or arising under the provisions o f 'certain

this act who shall, in the judgment of the court, be in complicity with case*,

any such combination or conspiracy ; and every such juror shall, before Juror* to take

entering upon any such inquiry, hearing, or trial, take and subscribe an oatl1'

oath in open court that he has never, directly or indirectly, counselled,

advised, or voluntarily aided any such combination or conspiracy; and False swear-

each and every person who shall take this oath, and shall therein swear ihfs oatMo be

falsely, shall be guilty of perjury, and shall be subject to the pains and perjury,

penalties declared against that crime, and the first section of the act Repeal of first

entitled “ An act defining additional causes of challenge and prescribing sectioI> of «ct

an additional oath for grand and petit jurors in the United States courts,” Vol.6xU.hp !« ’o

approved June seventeenth, eighteen hundred and sixty-two, be, and the

the same is hereby, repealed.

S ec. 6. That any person or persons, having knowledge that any of Any person

the wrongs conspired to be done and mentioned in the second section of certain''wro ŝ

this act are about to be committed, and having power to prevent or aid are about™be

in preventing the same, shall neglect or refuse so to do, and such wrong- done, and having

ful act shall be committed, such person or persons'shall be liable to the Pneg-

person injured, or his legal representatives, for all damages caused by lects’so to do,

any such wrongful act which such first-named person or persons by “n.y ®uch

reasonable diligence could have prevented ; and such damages may be hmafienabie’for

recovered in an action on the case in the proper circuit court of the all damages

United States, and any number of persons guilty of such wrongful “ suliL'therefor

neglect or refusal may be joined as defendants in such action: Provided, in court* of the

That such action shall he commenced within one year after such cause Tmted State*,

o f action shall have accrued ; and if the death of any person shall be joined'L™efend-

caused by any such wrongful act and neglect, the legal representatives ant-,

o f such deceased person shall have such action therefor, and may {fXathta

recover not exceeding five thousand dollars damages therein, for the caused by such

benefit o f the widow of such deceased person, if any there be, or if there wrongful act,

be no widow, for the benefit o f the next of kin o f such deceased person. MntartvMof'de-

S e c . 7. That nothing herein contained shall be construed to supersede ceased may

or repeal any former act or law except so far as the same may be repug- JjJ"^"j"f0arctioni

nant thereto; and any offences heretofore committed against the tenor who*e benefit,

o f any former act shall be prosecuted, and any proceeding already com- Former laws,

menced for the prosecution thereof shall be continued and completed, the not repealed,

same as if this act had not been passed, except so far as the provisions Former offen-

of this act may go to sustain and validate such proceedings. ce* be Profe-

A pfroved , April 20, 1871.