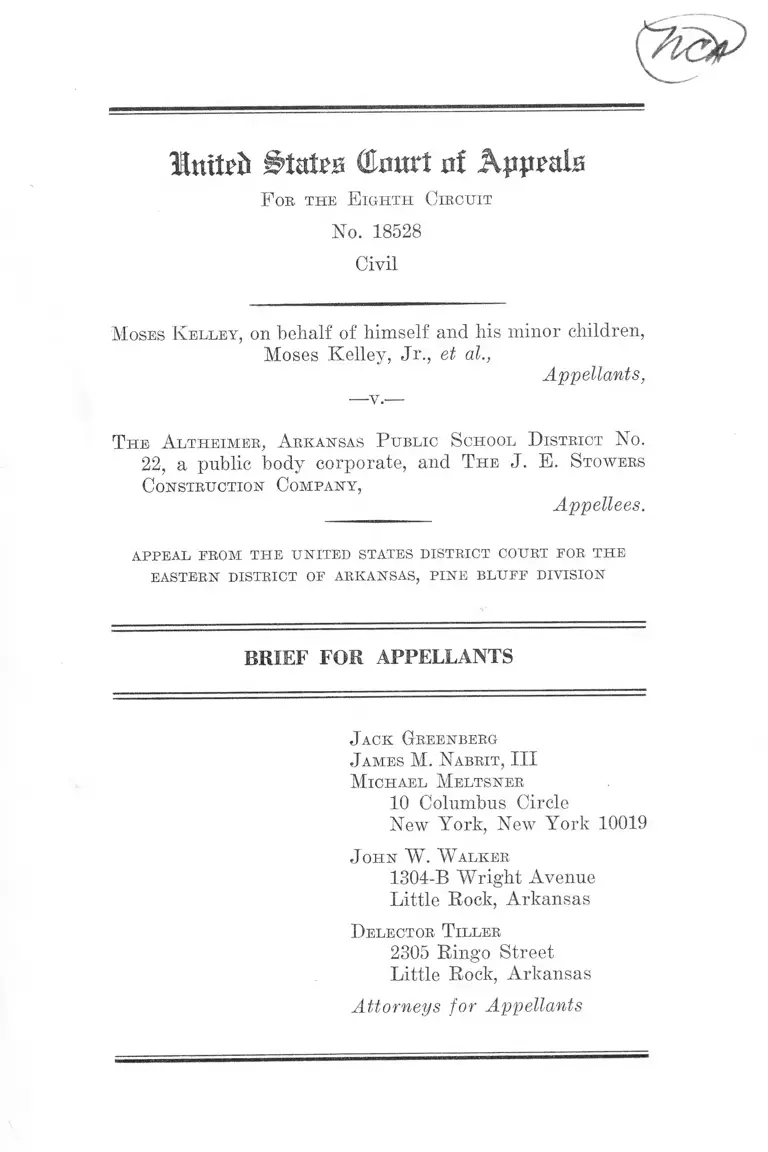

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22 Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22 Brief for Appellants, 1966. bb7b93c2-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/13a3b1b9-a85c-498f-9953-ea6b26883e39/kelley-v-the-altheimer-arkansas-public-school-district-no-22-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

llnxtth States (tort uf Kppmlz

F oe. the E ighth Circuit

No. 18528

Civil

Moses K elley, on behalf of himself and his minor children,

Moses Kelley, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

-v.-

The A ltheimeb, A rkansas P ublic S chool D istrict N o.

22, a public body corporate, and T he J. E. Stowers

Construction Company,

Appellees.

A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STATES D IST R IC T COURT FO R T H E

EA ST E R N D ISTR IC T OF A RK A N SA S, P IN E B L U F F D IV ISIO N

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit, III

Michael Meltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J ohn W. W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

D elector Tiller

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case .................................................. 1

I, The Altheimer School System and The Plan of

Desegregation .......................................... ............ 3

II. The Testimony of Dr. Myron Lieberman, Plain

tiff’s Educational Expert ..................................... 6

A. The Planning of the Replacement Construc

tion ..................................................... 7

B. The Inefficiency of the Dual School Structure 8

C. Perpetuation of Racial Segregation .............. 11

III. The Testimony of James D. Walker, Superinten

dent of Schools ............................. 12

A. The Past and Present Operation of the

Altheimer School System .................... 12

B. The Prospective Operation of the Plan of De

segregation ............................................. 14

Statement of Points to be Argued .............................. 17

A rgument

I. A School Board Has An Affirmative Duty to

Disestablish Segregation ..................................... 20

A. A School Board Has An Affirmative Duty to

Completely Re-organize a Segregated Dual

School System into a Unitary Integrated

School System ................ 20

PAGE

11

B. A School Board is Responsible for the Con

tinued Coercive Effects of the Tradition of

Segregation Which Its Previous Actions Es

tablished, and May Not Adopt Procedures

Which Perpetuate a Segregated Public School

System or Which Counteract the Desegrega

PAGE

tion Process ..................................................... 24

II. The “Freedom of Choice” Plan Approved By the

District Court is Fundamentally Inadequate to

Disestablish Segregation ..................................... 26

A. The District Court Erred in Holding that

“Freedom of Choice” Plans are Valid Regard

less of the Circumstances in Which They Op

erate and Regardless of Whether They Dis

establish Segregation ..................................... 26

B. The District Court Erred in Ignoring Over

whelming Evidence that the Replacement Con

struction Would Perpetuate Segregation, and

that the “Freedom of Choice” Plan Had No

Reasonable Probability of Disestablishing

Segregation in the System ............................ 30

III. The District Court Misconstrued the Power and

Duties of a Federal Court of Equity in Super

vising Desegregation and Granting Relief to Ac

complish that End ................................................ 33

Conclusion ................................................................... 39

\

X

111

Table oe Cases

p a g e

Board of Public Instruction of Duval Co., Fla. v.

Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir., 1964) ................. 37

Bowles v. Skaggs, 151 F.2d 817 (6th Cir. 1946) ...... 35

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U.S. 103 (1965) ......................................................... 31

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483

(1954); 349. U.S. 294 (1955) ................. 20, 22,Tt735, 38

\ / Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education, 253

F. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala., 1966) ................................ 36

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ............................23, 27

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir., 1960) ....23,25,27,

28, 32, 38

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp.

91 (W.D. Okla., 1965) ............................................ . 37

' / Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

. 373 U.S. 683 (1963) ................................................. 25, 27

• Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, Va.,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ...................................25,27,28,36

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2cl 14 (8th Cir., 1965) ....24, 26, 27,

29, 32, 33, 37, 38

Kier v. County School Board of Augusta Co., Va., 249

F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va., 1966) ............... ................ 31

Jifeo Feist, Inc. v. Young, 138 F.2d 972 (7th Cir. 1944) 35

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of

Memphis, 333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir., 1964)

^ Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) .23,27

IV

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S. 110

(1948) ......................................................................... 36

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir., 1966) ........................ 24

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School Dis

trict, No. 18,243 (8th Cir., 1966) .-..25, 26, 28, 30, 31, 32, 37

United States v. Bausch & Lomb Optical Co., 321 U.S.

707 (1943) .................................................................. 36

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319

(1947) ......................................................................... 36

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910) .... 36

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education, 346 F.2d

768 (4th Cir., 1965) ............. 37

PAGE

Inttefc States (Emtrt a! Appeals

F or the E ighth Circuit

No. 18528

Civil

Moses Kelley, on behalf of himself and his minor children,

Moses Kelley, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

-v.-

The A ltheimer, A rkansas P ublic S chool D istrict N o.

22, a public body corporate, and T he J. E. S towers

Construction Company,

Appellees.

A P P E A L PR O M T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FO R T H E

EA STER N D ISTR IC T OP A RK ANSAS, P IN E B L U F F D IV ISIO N

BRIEF FO R APPELLANTS

Statem ent o f the Case

This case originally involved a suit by Negro plaintiffs

against the Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District

No. 22 and the J. E. Stowers Construction Company1 to

enjoin them “from continuing plans to construct, and from

constructing, separate public elementary schools for white

and Negro elementary students” and “from continuing the

policy, practice, custom and usage of assigning pupils, fac

ulty and administrative staff on a racially discriminatory 1

1 Mr. Stowers had the contract for school construction which was

originally in issue. Apart from performing’ that contract, he had no other

direct interest in this lawsuit.

basis and from otherwise continuing any policy or practice

of racial discrimination in the operation of the Altheimer

School system” (R. 3).

In the complaint filed on February 15, 1966, plaintiffs

alleged that the school district had historically operated a

racially segregated system of public schools for Negro and

white pupils, that in 1965 it began a plan of desegregation

using the “freedom of choice” approach, but that it was

now about to have defendant J. E. Stowers Construction

Company construct new replacement facilities which would

perpetuate racial segregation (R. 4-5). Plaintiffs also

alleged that the “freedom of choice” plan of desegregation

now in use by defendant school district is incapable of

desegregating the district (R. 6) and sought a preliminary

and permanent injunction enjoining inter alia (a) “defend

ant Altheimer School District No. 22 and defendant J. E.

Stowers Construction Company from proceeding further

toward construction of separate elementary school facil

ities for Negro pupils and for white pupils” ; (b) “de

fendant Altheimer School District No. 22 from approving

budgets, making funds available, approving employment

contracts and construction programs, and other policies,

curricula and programs designed to perpetuate, maintain

or support a racially discriminatory school system” ; (c)

“defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 from con

tinuing its present ‘freedom of choice’ pupil desegregation

policy; and from any and all other policies or practices

established on the basis of the race or color of either the

teachers or pupils in defendant district” (R. 7-8).

Defendant Altheimer, Arkansas School District No. 22

in its answer admitted that prior to the 1965-1966 school

year it operated a racially segregated school system, but

alleged that its plan for desegregation using the “freedom

of choice” method had been approved by the Department

3

of Health, Education, and Welfare, and sought dismissal

of the case on the ground that plaintiffs had failed to state

a claim upon which relief could be granted (R. 12-13). De

fendant J. E. Stowers Construction Company also sought

dismissal of the case in a separate answer (R. 14-15).

The District Court denied the requested relief in an opin

ion dated June 3, 1966 (R. 227-248) and entered an order

dismissing the complaint (R. 249). In the course of that

opinion, the court concluded that plaintiffs’ basic attack

was not on the new construction per se, but on the “free

dom of choice” plan of desegregation itself. However,

the court dismissed the case on the basis that “free

dom of choice” plans had been upheld by appellate courts,

and that the United States Department of Health, Educa

tion, and Welfare now had primary responsibility for su

pervising school desegregation (R. 227-248).

Since the time of the filing of the suit, the new con

struction of which plaintiffs complained has taken place,

as the construction contract provided for completion by

August 15, 1966 (R. 194). However, plaintiffs continue

their basic attack on the adequacy of steps taken by the

board to achieve the Constitutionally required desegrega

tion of the school district.

I.

T he A ltheim er School System and T he P lan o f

D esegr egation.

The school district includes the town of Altheimer to

gether with a substantial rural area of Jefferson County

in the vicinity of the town (R. 227). It is a school district

of small population, having a total enrollment of 1,408

students in 1965-66, of whom 741 are elementary students

and 667 are junior and senior high school students (R.

28-29).

4

Prior to the commencement of the 1965-66 school year

the district had maintained racially segregated schools

(R. 228). Negro students were instructed in a complex of

buildings known as the Martin School, and white students

were taught in a complex of buildings known as the

Altheimer School. The sites of the two building complexes

are within six city blocks of each other (R. 179, 228).

Each site contains an elementary school consisting of the

first six grades and a combination junior-senior high

school consisting of grades 7-12 (R. 230). About midway

between the two sites there is another school building

in which vocational agriculture is taught (R. 228). About

two-thirds of the students at each school site arrive at

the school by school bus from outlying areas (R. 28-29,

179-180).

Also prior to the 1965-66 school year, the administrative

staff of the district was entirely white, except for the

principal of the Negro Martin School complex (R. 228).

The faculty was completely segregated, with white students

taught only by white teachers, and Negro students taught

only by Negro teachers (R. 228).

In response to the enactment of Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 and the promulgation of guidelines

by the United States Department of Health, Education,

and Welfare implementing Title VI, the Altheimer School

District submitted a voluntary plan of desegregation to

the United States Commissioner of Education in April,

1965, which, after amendment, was finally approved and

went into operation in September, 1965 (R. 229). The

method adopted for student desegregation was a “free

dom of choice” plan, under which students may express

choices for assignments to particular schools, the assign

ments to be honored as a matter of course unless this

would result in the overcrowding of a particular school.

5

In the event of overcrowding or a failure to exercise

choice, a student is supposed to be assigned to the school

nearest his home where space is available. The plan con

templated that freedom of choice would be afforded each

year after September, 1965 for all grades (R. 164, 230).

During the 1965-66 school year, two Negro elementary

students and four Negro high school students requested

assignment to the traditionally white Altheimer site. No

white students requested assignment to the traditionally

Negro Martin site. All six requests of the Negro students

were granted (R. 29, 231). Thus, six of the 1,001 Negro

students (or % of 1%) in the Altheimer school system

were in a desegregated school situation during the last

school year (R. 28-29). Apart from the three white teach

ers who have been assigned to the all-Negro Martin School,

the faculty of the school system remained segregated ac

cording to the race of the students which predominated

in each school complex (R. 231). No Negro teachers were

assigned to teach white students (R. 28-29).

After submitting its voluntary plan for desegregation to

the United States Office of Education in April 1965, the

Altheimer school board adopted a plan to construct two

new elementary classroom buildings containing a total of

sixteen (16) classrooms and related facilities to be located

on the traditionally Negro Martin site, and a single ele

mentary classroom building containing six (6) classrooms

and related facilities to be located on the traditionally white

Altheimer site (R. 229). The number of new classrooms at

each site is roughly in proportion to the distribution of

Negro and white elementary students in the system (543

Negro and 198 white) and to the present enrollments at

each site (541 Negroes at the Martin site and 2 Negroes

and 198 whites at the Altheimer site) (R. 28-29). The

board contracted with the J. E. Stowers Construction

6

Company on February 10, 1966 to undertake this construc

tion (R. 215), after having obtained approval of a bond

issue to finance the construction (R. 229). Five days later,

plaintiffs filed suit to enjoin this construction (R. 1).

II.

T he Testim ony o f D r. M yron L ieberm an, P lain tiff’s

E ducational E xpert.

Plaintiffs obtained the services of an educational expert,

Dr. Myron Lieberman, to analyze the planning for and the

educational soundness of the then proposed new construc

tion. Dr. Lieberman is Director of Education Research and

Development, and Professor of Education, at Rhode Island

College in Providence, Rhode Island.2 Dr. Lieberman made

a substantial field investigation of the Altheimer school

system, and surveyed the planning and impact of the con

struction proposal. He examined physical facilities at both

school complexes and interviewed the Superintendent of

Schools, James D. Walker, the principals of the two school

complexes, and a number of teachers and other adminis

trators in the school system. He was able to obtain rele

vant data from the school administration to allow him to

analyze the operation of the system (R. 40-42).

2 He has a Bachelor’s degree in law and social scienee from the Uni

versity of Minnesota and Master’s and Ph.D. degrees in education from

the University of Illinois. In his graduate study, he concentrated in the

area of the “social foundation of education,” which involves analysis of

the influence of factors such as race, religion, tax structure, and other

cultural and social factors on the social institution of public education.

He taught in this area for 12 years. His present position requires him

to work with public agencies, private foundations, and various experts in

public planning fields. He has co-authored four books on school personnel

administration and other aspects of public school planning (R 37-40).

7

A. T he Planning o f the Replacem ent Construction

Dr. Lieberman discovered that the plans for these new

buildings were “a carryover from a plan that the Board

had considered some years [previously]” at a time when

“the unwavering policy of the Board had been to operate

its schools in a racially segregated manner” (R. 53-54). He

concluded that since school construction plans must logi

cally reflect such an overall basic policy of a board, the q L 0

construction plans “would almost inevitably be changed if

the Board had abandoned that policy” (R. 54). (This find

ing was confirmed by the testimony of Fred Martin, Prin

cipal of the Martin school complex, who stated that the

replacement facilities in controversy were planned as part

of a 10-year building program in 1957, at a time when no

thought was given by the school system administration

to other than segregated dual operation (R. 109-111).)

In his interviews with school officials, Dr. Lieberman

found that there were no educational reasons underlying

the Board’s decision to build sixteen new elementary class

rooms at one site and six new elementary classrooms at

the other site, rather than putting all of the new class

rooms at one complex, or eleven at each complex or some

other alternative. The Superintendent simply referred

to traditions in the community (R. 54) and the Board

never considered the alternative of a single elementary

facility at one complex and a single secondary facility at

the other complex (R. 56). Dr. Lieberman noted that this

was distinctly not in accord with standards of professional

educational administration practice, since it is an obliga

tion of school administrators to analyze the costs and the

advantages of various alternative possibilities of school

construction (R. 56-57).

j\Z°

j>-ckV'-&

f f h

(ri _

8

There was also no community involvement in the plan

ning of the new construction by the school board.3

B. T he Inefficiency o f the Dual School S tructure

As part of his analysis of the possible bases for the

school board’s program of replacement construction, Dr.

Lieberman considered the overall educational efficiency

and desirability of the present dual structure of the

Altheimer school system with two small school complexes.4

A crucial reason for the desirability of larger high

schools is to provide adequate teachers for specialized sub

jects. When the total enrollment of the school falls below

a certain number, the small percentage of the student

body who are apt to elect any one of a number of special

ized academic subjects will probably be so small that the

school system will not feel that the expense of providing

a teacher for that subject is justified. Thus, if there were

two schools in which only ten students in each elect a

particular subject, the school board might not provide a

teacher for that subject in either school and therefore all

20 of those students would be deprived of the opportunity

of taking that subject; however, if all 20 of those students

were in the same school and elected that subject, the school

3 Dr. Lieberman referred to several authorities on educational planning

procedures, in particular the National Council for School Construction,

and noted that these authorities called for thorough community involve

ment in the planning of new school construction in order to ascertain com

munity needs. (R. 52-53). Neither had a professional ed'ucafion~alconsultant

on the planning of facilities been utilized (R. 53). His general conclusion

was that planning for the new school construction was not in accord with

sound professional practice in the field of education (R. 54-55).

4 He based his analysis particularly on what he considered ‘‘the most

important study of secondary education that has been made in this coun

try,” Dr. James Bryant Conant’s Study of the American High School

(R. 44-45). He pointed out that in this work, Dr. Conant gives top

priority in educational planning to the elimination of small high schools

for various reasons (R. 47).

9

board would then feel justified in undertaking the expense

of a teacher for that subject (R. 47).

Li<r'

This type of analysis was applied by Dr. Lieberman

to other aspects of school operations at both the elemen

tary and high school levels. For instance, the Altheimer - n &

school system is operating two libraries for grades one . y l ' c

through 12 six blocks apart. If each library is to be ade- ^

quate and the facilities are to be equal, the school system L"

must buy duplicate copies of every book, and every time

duplicate copies of the same book are purchased where

one would be sufficient, this means there will be less money

to buy other different books that would be useful to students

(R. 45-46).

Dr. Lieberman noted that there is also the matter of

specialization of training among personnel. For instance,

it is most desirable for elementary students to have spe

cially trained elementary librarians and secondary students

to have specially trained secondary librarians. However, fl' A

if there are two libraries, each of which covers grades 1

through 12, and only one librarian at each one, then they

will either have to have an elementary librarian and the v

secondary pupils will suffer because the librarian is in

adequate for them, or vice versa. This would not be the

case if one school were an entirely elementary school and

the other school an entirely secondary school (R. 46).

Even where a school system does undertake to dupli

cate course offerings and services in each of two small

schools, Dr. Lieberman continued, it still cannot avoid

necessary resulting inefficiencies. For instance, schools

today perform a wide-range of functions in addition to

purely academic instruction, such as vocational guidance,

which require specialized personnel. If this special ser

vice or special type of course is offered at a small school,

A

10

it is not feasible for a specially trained teacher or other

such special service personnel to spend all his time doing

what he is a specialist in because there are too few pupils

to require his full-time services, and to that extent his

specialized training is wasted. The existence of such a

situation also makes it more difficult to attract such spe

cialized personnel, whose services are often difficult to ob

tain in the first place (R. 50).

Dr. Lieberman pointed out that the capital outlay for

equipment as well as the salary of specialized instructors

adds up to such a large figure in terms of the few enrolled

as to make many educational programs prohibitively ex-

f ( pensive in schools where the graduating classes have less

p UL* fg than one hundred (R. 47-48). Educational experts gen

erally assume that a school district which is capable of

eliminating small schools will do so. Dr. Lieberman con

cluded that it did not make sense that a district such as

Altheimer would maintain “two high schools, which even

combined, were less than the number needed to operate a

high school efficiently from an educational standpoint”

(R. 48). In reaching his conclusions, Dr. Lieberman said

that he had considered situations in which the construc

tion of separate facilities might be justified, such as the

children in the school district being so far apart that it

is not feasible to transport them to a central school, but

that none of these were applicable to the Altheimer case

(R. 50-51).

An additional element of the inefficiency which arises

from the operation of a dual school structure is the con

tinuing problem of maintaining equality of educational

opportunities between the two school systems. There are

many continuing difficult specific decisions to make, such

as how many books or how many teachers or what facili-

<o

t, $7I T

f

■fd

V 0>v

11

ties, etc., should be placed in one school or the other (R.

55-56).

C. P erpetuation o f Racial Segregation

Dr. Lieberman concluded that there was no educational ^

or financial justification for the perpetuation of a com- f i

pletely dual set of schools in the Altheimer school system

by the replacement construction. The operation of such a

dual system makes a sound educational program of “such

esorbitant cost that the school system is never going to

pay it and can’t pay it” (R. 49-50). He also said: “I

regard this as a major dis-service to the white students

as well as to the Negro students” (R. 48).

Dr. Lieberman pointed out that by building two school

complexes both of which run from grades one through

twelve the school board has perpetuated an element which

will divide the district for the indefinite future (R. 55).

He concluded that “race is a factor because there’s a

complete absence of any other educational or financial or

professional justification for doing it” (R. 57). He em

phasized that this was not simply a matter of differences

between himself and the Altheimer School Board over ed

ucational practices, biff rather a complete absence of any

justification for the dual construction according to any

educational theory or practice based on his professional

knowledge (R. 57-581.

Kr

e ft '

fi

R * *

12

III.

T he Testim ony o f Jam es D. W alker, S uperin tenden t

o f Schools.

A. T he Past and Present Operation o f the

A ltheim er School System

F ^

In the course of his testimony, the superintendent in

dicated that for the year ending 1965 the per pupil cost

in the white Altheimer High School was approximately

$390.00, while in the Negro Martin High School it was

$192.00; and in the white Altheimer Elementary School

the per pupil cost was approximately $265.00, while in

the Negro Martin Elementary School it was approximately

$165.00 (R. 201-202). Some of this disparity was due to

the capital inefficiencies arising from the fact that the

white schools are substantially smaller than the Negro

schools (R. 219). The disparity in per pupil cost also

reflects in part the past tradition of the school system of

paying Negro teachers in the Negro schools somewhat less

for equivalent work than white teachers in the white schools

(R. 131-132,137). For instance, a number of Negro teachers

ranging in experience up to several years were compen

sated at the rate of four thousand dollars annually, while

the minimum, rate for a white teacher of no experience

was four thousand three hundred dollars (R. 131-132).

>/; C(

i 'U

/ i D Ifl{TP

The white Altheimer School complex is accredited by

the North Central Association (N.C.A.), which is the

highest rating of schools in its section of the nation, while

the Negro Martin School complex is not so accredited.

The Martin School has an A rating from the State of

Arkansas, which is considered not as desirable as ac

creditation by the North Central Association (R. 129-130).

Nevertheless, the Negro Martin High School is on the

13

whole newer and more modern in facilities than the white

Altheimer High School (R. 111). When questioned as to

why then the North Central Association has denied N.C.A.

rating to the Martin School while it has granted same to

the Altheimer School, the Superintendent stated that it

took a great amount of work over several years in sub

mitting applications and having inspections, etc., in order

to secure N.C.A. accreditation and that this simply had

not been done for the Martin School complex (R. 141-142).

The Superintendent indicated however, that there was a

substantial basis for the discrepancy in ratings of the two

school complexes over-all when elementary as well as high ^ ̂ m1' j) ifuj

school facilities are taken into account. He stated that he £ §->p

hoped to achieve the objective of substantially equal facili

ties as soon as possible (R. 218).

< ^ hf e e -

Of

The Altheimer School District has recently received a

substantial amount of Federal funds under the Public

Law 89-10 program of aid to culturally deprived students.

In order to secure its grant-in-aid, the district certified

that it had approximately eight hundred (800) students

in the culturally deprived category, of whom approxi

mately seven hundred (700) were Negroes and only one

hundred (100) were white (R. 145-147). In spite of the

fact that one of the deficiencies of the Negro Martin

School in North Central Association rating is the library,

the school district is undertaking to build a new library at

the Altheimer School, which serves almost exclusively

white students (R. 147-152). Refurbishment of the library

at the Negro Martin School is scheduled for the fiscal

year following the building of the new library at the white

Altheimer School (R. 191). The school district has also

hired some additional staff with the new Public Law 89-10

funds, and continued the practice of assigning Negro staff

members so hired to the Negro school and white staff mem

bers to the predominantly white school (R. 122-123).

■ Piuf tf

f f L

14

B. T he Prospective Operation o f the Plan

o f Desegregation

When questioned as to how the Altheimer Board pro

posed to eliminate the dual school system as they had

agreed to do by accepting Federal funds under Title VI,

the Superintendent said that the plan was to use “freedom

of choice” in all grades (R. 162). However, he conceded

that the Board was relying primarily on the Negro pupils

to desegregate the system for them, and indicated that

the Board had not given any thought to the problem of

how to change the system into an integrated one if Negro

pupils for any reason did not exercise choices which

achieved that result (R. 163). The Superintendent did not

expect a substantial amount of desegregation to take place:

he said “I would predict there will be several Negro chil

dren who will elect to go to the formerly all white school”

(emphasis supplied) when asked whether he anticipated

any substantial increase in the number of Negro pupils

choosing to go to the traditionally white school (R. 174).

He admitted that there was no reason, based on his experi

ence, and conversations with other school superintendents,

. to assume that any white students would choose to go to

-tile traditionally Negro school under the freedom of choice

plan (R. 182).

The Superintendent admitted that the construction plans

for elementary replacement facilities at the two school

complexes which were in issue in the case were rooted in

the traditional operation of the school system: Although

the supporting facilities such as a cafeterias, gymnasiums,

and auditoriums at both sites are equivalent and would

support equal-sized facilities, he said that the reason for

building a sixteen-classroom facility at the Negro Martin

site and a six-classroom one at the white Altheimer site

was “traditionally there have been more students in Martin

A . C oyr-,0 o r x

- - c_i'/ / A ^ v £ v ’S'1’ A

Elementary School than have been in the other school”

(R. 181-182). (There are 541 Negro elementary students at

the Martin site, and 198 white plus 2 Negro elementary

students at the Altheimer site (R. 28-29).) When asked if

all the pupils in the school district were white, would the

construction plans have been any different, the Superin

tendent replied “All the pupils are not white” (R. 181).

When asked how the plan of building a smaller school at

the traditionally white Altheimer site would facilitate the

movement of Negroes from the larger Martin School into

an integrated situation, assuming that whites will not

choose to go to the traditionally Negro Martin School,

the Superintendent stated simply: “I think the new guide

lines will do the facilitating that needs to be done” (R. 182).

He denied deliberately trying to create overcrowding at

the Altheimer site. However, he was unable to explain how

with approximately two hundred white elementary pupils

in the district and a replacement facility being constructed

of just about that capacity (assuming that whites will not

choose to go to the traditionally Negro school), there could

be any substantial desegregation without overcrowding (R.

183).

In discussing the relation of teacher desegregation to

the operation of a “freedom of choice” plan, the Superin

tendent admitted that if substantially all the teachers in

a particular school are of one race, the community tends

to identify that school as intended for that particular race

(R. 176-177), that past assignments in the system had been

on a racially segregated basis, and that reassignment to

the same position therefore perpetuates that segregation

(R. 170). Nevertheless, he stated that the teacher deseg

regation plan for 1966-1967 called only for the assignment

fkcu \j)£s

J f i ' U

f t C A M t f h

16

of one more white teacher to teach vocational agriculture

in the Negro school (E. 168). He said that as the super

intendent of schools, he has the authority to reassign

teachers, but even though the predominantly white school

would remain identified as a white school unless he as

signed some Negro teachers there, he was not going to

“reassign teachers just to be reassigning them” (E. 175).

17

Statement o f Points to be Argued

I.

A School Board Has An Affirmative Duty to

establish Segregation.

A. A School Board Has A n Affirm ative D uty to

Com pletely Re-organize a Segregated Dual

School System into a Unitary Integrated School

System--

Dis-

§ftf] £

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S.

483 (1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955);

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958);

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965);

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir., 1960);

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir., 1965);

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 355 F.2d 865 (5th Cir., 1966).

B. A School Board is Responsible fo r the C ontinued

Coercive Effects o f the Tradition o f Segregation

W hich Its Previous Actions Established, and May

Not A dopt Procedures W hich Perpetuate a Segre

gated Public School System or W hich Counteract

the Desegregation Process

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knox

ville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963);

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County,

Va., 377 U.S. 218 (1964);

Dove v. Parham, supra;

Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton School

District, No. 18.243 (8th Cir., 1966).

l ire-

18

II.

The “Freedom of Choice” Plan Approved By the

District Court is Fundamentally Inadequate to D ises

tablish Segregation.

A. T he District Court Erred in H olding that “Freedom

o f Choice” Plans are Valid Regardless o f the

Circumstances in W hich T hey Operate and Regard

less o f W hether T hey Disestablish Segregation

Kemp v. Beasley, supra;

Brown v. Board of Education, supra;

Cooper v. Aaron, supra;

Rogers v. Paul, supra;

Goss v. Board of Education, supra;

Griffin v. School Board, supra;

Dove v. Parham, supra;

Smith v. Morrilton School District, supra.

B. The District Court Erred in Ignoring Over

w helm ing Evidence that the R eplacem ent Construe- j

tion W ould Perpetuate Segregation, and that the

“Freedom o f Choice” Plan Had No Reasonable

Probability o f Disestablishing Segregation in the

System ....... ____ __— -----____

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond,

382 U.S. 103 (1965);

Kier v. County School Board of August Co., Va.,

249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va., 1966);

Smith v. Morrilton School District, supra;

Dove v. Parham, supra;

Kemp v. Beasley, supra.

19

III.

The D istric t C ourt M isconstrued th e Pow er and

D uties o f a Federal C ourt o f E quity in Supervising D e

segregation and G ranting R elief to A ccom plish T hat

End.

Brown v. Board of Education, supra;

Bowles v. Skaggs, 151 F.2d 817 (6th Cir. 1946);

Leo Feist, Inc. v. Young, 138 F.2d 972 (7th Cir.

1944);

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334

U.S. 110, petition denied, 334 U.S. 809 (1948);

United States v. Bausch ds Lomb Optical Co.,

321 U.S. 707 (1943);

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S.

319 (1947);

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1

(1910);

Griffin v. School Board, supra;

Board of Public Instruction of Duval Co., Fla.

v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir., 1964);

Wheeler v. Durham City Board of Education,

346 F.2d 768 (4th Cir., 1965);

Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Educa

tion, 253 F. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala., 1966);

Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244

F. Supp 91 (W.D. Okla., 1965);

Smith v. Morrilton School District, supra;

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City

of Memphis, 333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir., 1964);

Dove v. Parham, supra;

Kemp v. Beasley, supra;

20

ARGUMENT

I .

A School Boai’d Has An Affirm ative D uty to Dis

estab lish Segregation.

A. A School Board Has A n A ffirm ative D uty to

Com pletely Re-organise a Segregated Dual

School System Into a Unitary Integrated School

System

The Supreme Court stated the rationale for outlawing of

segregation in public education in the original Brown de

cision as follows:

Segregation of white and colored children in public

schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored chil

dren. The impact is greater when it has the sanction

of law; for the policy of separating the races is usually

interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the negro

group. 347 U.S. at 494.

# * *

To separate them from others of similar age and

qualifications solely because of their race generates a

feeling of inferiority as to their status in the com

munity that may affect their hearts and minds in a

way unlikely ever to be undone. 347 U.S. at 494.

Thus the conclusion that the equality of all tangible factors

in the dual school systems is an illusory equality because

of the social contexts in which the systems operate, and

that segregated schools are “inherently unequal.” Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

21

There are several important premises in Brown which

are crucial to the working out of later problems arising in

implementing the decision. The Court recognized the vastly

differing positions of whites and Negroes generally in the

social and political structures of communities in which

segregation was practiced, for otherwise the conclusion (d7

that “equal” school systems were inherently unequal would ' gf> p''<’

not have made sense. By stating that the policy of segrega- crS ^ /y y.

tion denoted inferiority, the Court recognized that the in

stitutions of power in these communities were exclusively

controlled by whites, who generally believed that Negroes

wTere inferior and who acted on the basis of that belief in

their conduct of public policy. By this analysis, the Court

also recognized that the tradition and practice of segrega

tion was coercive to the Negro group: if Negroes and

whites had Teen regarded as being equally powerful, the

system of segregation might otherwise have been assumed

to be voluntary on the part of all concerned. Finally, the

Court recognized that the system of segregation had very

deep effects on all of the individuals involved and there

fore constituted a very durable tradition. It noted ex

plicitly that segregation had the effect of causing many

Negroes to believe that they were in fact inferior and that

the system of segregation was proper, and that these

beliefs would last for a lifetime. But the converse was

also implicit, that many whites in the segregated system

must have come to believe that they were superior to

Negroes as a class and, therefore, that segregation was

proper, and that these beliefs were deeply held and were

acted upon by such persons in positions of power.

The original Brown decision presupposed a major re

organization of the educational systems of the affected com-

22

munities, the extent of which is suggested by the fact

that the Court took an additional year to consider the

problem of relief. In the second Brown decision, 349 TJ.S.

294 (1955), the Court pointed out that “to effectuate this

interest may call for elimination of a variety of obstacles

in making the transition to school systems operated in

accordance with the constitutional principles set forth in

our May 17, 1954 decision.” 349 U.S. at 300.

The Court indicated the nature of the obstacles to be

overcome in the second Brown decision by its direction

to the courts supervising the re-organization of the school

systems to “consider problems related to administration,

arising from the physical condition of the school plant,

the school transportation system, personnel, revision of

school districts and attendance areas into compact units

to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws

and regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problems.” 349 U.S. at 300-301. This direction,

combined with the injunction that desegregation was to

be achieved “with all deliberate speed,” revealing an

expectation that completion of the process would take

some time, provides as clear an indication as possible

that a thorough and complete re-organization of the segre

gated school systems was envisioned. That the expecta

tion of time being required to carry out the decision was

related to the extensiveness of the re-organization of the

school systems envisioned, rather than to the hostility to

the changes which might be anticipated, was indicated

by the Court’s statement that “it should go without saying

that the vitality of these constitutional principles cannot

23

be allowed to yield simply because of disagreement with

them.” 1 349 U.S. at 300.

Recently, in Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.8 . 198 (1965), the

Supreme Court re-affirmed the completeness of the re

organization of the segregated school systems suggested

by the enumeration of factors in the second Brown deci

sion, by holding that students in a segregated system

had clear standing to challenge the racial allocation of

faculty personnel. The Court also clearly indicated that

the provision of transfers for Negro students who so

desired to schools with more extensive curricula from

which they had been excluded, was something substan

tially less than it envisioned as an adequate general plan

of desegregation, since it ordered the provision of such

transfers “pending” desegregation according to a general

plan.

This Court has construed Broivn as imposing an affirma

tive obligation on school boards in previously segregated

systems to disestablish segregation and provide integrated

school systems. In Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th

Cir., 1960), it said:

Placement standards and educational doctrines are

entitled to their proper play, but that play, as we

1 The Supreme Court subsequently made a clear statement in Cooper V.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958), that the Brown decisions imposed an affirma

tive obligation on school officials of segregated dual school systems to dis

establish segregation:

State authorities were thus duty bound to devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation and bringing about the elimination of racial

discrimination in the public school system. 358 U.S. at 7.

Although Cooper itself was a case of clear and direct defiance by state

officials, the Court looked forward to a time when attempts to perpetuate

segregation in public education might become more subtle, when it said

that the constitutional rights involved “can neither be nullified openly

and directly by state legislators or state executive or judicial officers, nor

nullified indirectly by them through evasive schemes for segregation

whether attempted ‘ingeniously or ingenuously.’ ” 358 U.S. at 17.

24

have emphasized, is subordinate to the duty to move

forward, by whatever means necessary, to correct the

existing constitutional violation with “all deliberate

speed.” 282 F.2d at 261.

In Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir., 1965), this

Court rejected the well-known Briggs v. Elliott dictum

(construing’ the school desegregation decisions restric-

tively) that the Constitution does not require “integra

tion” but merely forbids “discrimination” :2

The dictum in Briggs has not been followed or adopted

by this Circuit and it is logically inconsistent with

Brown and subsequent decisional law on this subject.

352 F,2d at 21.

B. A School Board is Responsible fo r the C ontinued

Coercive Effects o f the Tradition o f Segregation

W hich Its Previous Actions Established, and May

Not A dopt Procedures W hich Perpetuate a Segre

gated Public School System or W hich Counteract

the Desegregation Process

The Supreme Court has recognized the continued coer

cive potency of the tradition of segregation in the com

munities in which it had existed as a compulsory legal

requirement, in several cases which prohibit school offi

cials from establishing procedures which permit private

2 The Fifth Circuit, in its most recent general decision on school desegre

gation, Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 355 F.2d

865 (5th Cir., 1966), agrees:

The Constitution forbids unconstitutional state action in the form of

segregated facilities, including segregated public schools. School au

thorities, therefore, are under the constitutional compulsion of furnish

ing a single, integrated school system. . . .

This has been the law since Brown v. Board of Education . . .

Misunderstanding of this principle is perhaps due to the popularity

of an over-simplified dictum that the constitution “does not require

integration.” 355 F.2d at 869

25

individuals to perpetuate the segregated school system.

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, 373

U.S. 683 (1963).3 In Griffin v. School Board of Prince

Edward County, Va., 377 U.S. 218 (1964), the Court found

the closing down of the public schools to permit private

individuals to continue a segregated school system to be

inconsistent with a school board’s affirmative duty to over

come the effects of the tradition of segregation.

This Court has affirmed the extensiveness of the respon

sibility of school officials for the coercive effects of the

tradition of segregation which their previous actions helped

establish, in a series of cases in which policies on their

face non-discriminatory were nevertheless invalidated be

cause of a context of a community tradition of segrega

tion in which they were held to operate to perpetuate

that tradition. In Dove v. Parham, supra, this Court pro

scribed the application of what would otherwise have

been regarded as an educationally valid system of place

ment standards by a school system in a plan of desegre

gation, which resulted in the school system remaining as

effectively segregated as before.4 In Smith v. Board of

3 In (?oss, the Court struck down a “minority to majority” transfer

plan, under which students initially assigned by a unitary geographic zone

plan, were permitted to transfer out of their assigned school if their race

was in the minority at that school back to their former segregated school,

on the ground that their race would there be in the majority. The Court

noted that “it is readily apparent that the transfer system proposed lends

itself to perpetuation of segregation” since “the effect of the racial trans

fer plan was (to permit a child (or his parents) to choose segregation

outside of his zone but not to choose integration outside of his zone.’ ”

373 U.S. at 686-687.

4 This Court said:

If placement standards, educational theories, or other criteria used

have the effect in application of preserving a created status of con

stitutional violation, then they fail to constitute a sufficient remedy

for dealing with the constitutional wrong.

Whatever may be the right of these things to dominate student

location in a school system where the general status of constitutional

violation does not exist, . . . in the remedying of the constitutional

26

Education of Morrilton School District, No. 18,243 (8th

Cir., 1966) this Court explicitly reaffirmed the basic prin

ciple of the Dove case and applied a comprehensive view

of causation, where the adoption of a plan of desegrega

tion had resulted in the closing of a Negro school and

the board had dismissed the entire all-Negro faculty.* 6 It

held that the dismissals were a consequence of segregation

and were therefore racially motivated.

II.

T he “ F reedom o f Choice” P lan A pproved By the

D istric t C ourt is Fundam entally Inadequate to D ises

tab lish Segregation.

A. The District Court Erred in H olding that “Freedom

o f Choice” Plans are Valid Regardless o f the

Circumstances in W hich They Operate and Regard

less o f W h e th er They Disestablish Segregation

This Court accepted the validity of the concept of “free

dom of choice” plans of desegregation in Kemp v. Beasley,

wrong-, all this has a right to serve only in subordinancy or adjunc-

tiveness to the task of getting rid of the imposed segregation situation.

282 F.2d at 259.

6 This Court said:

We recognize the force of the Board’s position that the discharge

of the Sullivan staff upon the school’s closing was only consistent with

the action taken by the Board in connection with eleven other school

consolidations, and consequent closings, in the past. . . .

But on this record these dismissals do not stand alone. This Board

maintained a segregated school system . . . The employment and as

signment of teachers during this period were based on race. . . .

The use of the freedom-of-choice plan, associated with the fact of a

new high school plant, produced a result which the superintendent

must have anticipated . . . All this reveals that the Sullivan teachers

did indeed owe their dismissals in a very real sense to improper racial

considerations. No. 18,243 at pp. 13-14.

* * *

Under circumstances such as these, the application of the policy (al

though that policy is nondiscriminatory on its face and is based upon

otherwise rational considerations) becomes impermissible. No. 18,243

at p. 16.

supra, but at the same time recognized that such plans could

be inconsistent with decisions of the Supreme Court and

this Court as outlined above. The “freedom” in a “freedom

of choice” plan may be just as illusory for Negroes as was

the “equality” in the “separate but equal” doctrine struck

down by the Supreme Court in the original Brown decision.

To hold otherwise is to dispute the fundamental premise of

Brown that segregation had very deep and long term effects

on both whites and Negroes who grew up in the system, and

that the tradition of segregation was coercive to Negroes.

We need only recall that it is individuals who were brought

up in that system who are now required to exercise the

choices as parents in a “freedom of choice” plan to change

the system—and Negroes who were brought up to believe

that they were not supposed to step out of “their place”

and put themselves in positions of equality with whites, and

whites who were brought up to believe that it was improper

for Negroes to be in any situation of equality with them, just

might not exercise choices in such a way as to bring about

desegregation.

We submit that a “freedom of choice” plan may be in

consistent with the affirmative duty of a school board to

completely re-organize the school system from a dual segre

gated system into the unitary integrated system which

would have existed but for the establishment of the practice

of segregation, Brown v. Board of Education, supra, Cooper

v. Aaron, supra, Rogers v. Paul, supra, Dove v. Parham,

supra, Kemp v. Beasley, supra. A “freedom of choice” plan

may be inconsistent with the prohibition on school boards

from establishing procedures which permit private indi

viduals to perpetuate a substantially segregated school

system whether by direct physical or_economic coercion or

by~suff£Ie'"indirect hostility which may nevertheles be effec

tive in so doing, Cross v. BoarJ of Education, supra, Griffin

28

v. School Board, supra. A “freedom of choice” plan may be

inconsistent with the principle that policies which may be

valid outside the context of a community tradition of segre

gation may nevertheless be invalid within that context if

their effect is to perpetuate segregation, and that school

boards are responsible for the coercive effects of the tradi

tion of segregation which they established, such as par

ticular schools continuing to be identified as “Negro” schools

or “white” schools in the minds of the community, Dove v.

Parham, supra, Smith v. Morrilton School District, supra.

Most important, a “freedom of choice” plan may be incon

sistent with Brown because it does not or cannot actually

work to desegregate the system.

The district court in its decision determined that “the

basic complaint of plaintiffs goes not so much to the con

struction and location of the new buildings but rather to

the whole concept of freedom of choice as a means of

bringing segregation to an end” (R. 232). The court said

that it understood that plaintiffs’ argument that freedom

of choice could not bring unlawful segregation to an end

was based on two premises: “(1) That white students will

not request assignments to Negro schools. (2) That the

general run of Negro students wfill not apply for assign

ments to formerly all white schools because of fear of vio

lence or economic reprisals” (R. 235-236). The court agreed

with the first premise, but said that the second premise

“may or may not have some basis in fact, and may or may

not have some validity from a purely sociological stand

point. The Court does not think it necessarily valid from

a legal and constitutional viewpoint” (R. 236). The court

then held:

,, " '''MFifee-^doors of the formerly all white schools are

freely opened to Negro students so that they can go

there when and if they choose, and if they are per

mitted to go back to their original schools if dissatisfied

with the transferee schools, it would seem to the Court

that the Constitutional requirement of the 14th Amend

ment has been met. Cf. Briggs v. Elliot, supra. If a

person is given freedom of action, the Court does not

know that he is being subjected to discrimination in

the Constitutional sense merely because he may be

afraid or reluctant to exercise his right of choice

(R. 236-237).

The court also adopted the Briggs v. Elliott view that it

is going further than the Constitution requires to order

the elimination of dual school facilities (R. 234). [The

court also stated that it knew that in some other Arkansas

districts substantial numbers of Negro students had re

quested assignments to formerly all white schools (R. 237).]

We submit that this view that “freedom of choice”

plans are inherently valid regardless of the circumstances

in which they operate and regardless of whether they dis

establish segregation of the school system is fundamentally

inconsistent with the limited approval given by this Circuit

to the “freedom of choice” concept in Kemp v. Beasley,

supra, in which the Briggs v. Elliott view was explicitly

rejected. It is, moreover, fundamentally inconsistent with

the general Supreme Court and Eighth Circuit jurispru

dence on school desegregation outlined above. It is also

obvious error to hold, as did the district court (R. 237),

that because “freedom of choice” plans may have produced

some desegregation in some districts other than the one

involved in this case, such a plan is therefore necessarily

it(*ceuialilc-ni--tlns..dis.li.'.i{;j, w1 iqt.j.1 b e d shows, inter alia,

that virtually no desegregation has taken place] (R. 28-29,

'... .. , ... .., _̂»—***"*

B. T he District Court Erred in Ignoring Over

w helm ing Evidence that the R eplacem ent Construc

tion W ould Perpetuate Segregation, and that the

“Freedom o f Choice” Plan Had No Reasonable

Probability o f Disestablishing Segregation in the

System

The district court erred fundamentally, in ignoring the

relevance of the new replacement construction of the

nearby dual school plants to the issue of the “freedom”

in the “freedom of choice” plan. The nature of the con-

structi<m—that new dual elementary schools were built

practically next door to each other on the traditional segre-

gated sites, that their capacities were of almost exactly the

respective numbers of whites who traditionally attended

the white site and of Negroes who traditionally attended

the Negro site, and that there was no rational educational

purpose apparent behind such dual construction (E. 28-29,

228-229)—was not susceptible to any other interpretation

by the community 'than..'fEat the school board would con- ,

UHUtJ LU iMihlam a dual segregated school system, with v

one school'.thfendeiMbT^wffifes” and the other school in

tended for Negroes. This was just as unambiguous an act

as re-writing the word “white” over the door of the

Altheimer School and the word “Negro” over the door of

the Martin School—and is just as coercive to the Negroes

who have traditionally been informed by the segregated

system that they were not wrnnted in “white” institutions,

and to whites who have been informed that it was not

proper for them to be in “Negro” institutions. The school

board is clearly responsible for the community tradition of

segregated schools which it established which causes the

replacement construction as planned to be regarded as the

perpetuation of segregated schools. Smith v. Morrilton

School District, supra. The replacement construction here

has precisely the same effect on the “freedom” in a “free

dom of choice” plan as does the maintenance of all-white

31

and all-Negro faculties at various schools in a system. Cf.

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382 U.S.

103 (1965); Kier v. County School Board of Augusta Co,,

Va,, 249 F. Supp. 239 (W.D. Va., 1966) at 246. The differ

ence is that the coercive effect of the permanent construc

tion is not solvable within the framework of a “freedom of

choice” plan as is the faculty problem by compulsorily in

tegrating the faculty.

The court also erred in its finding that the replacement

construction plan was not contaminated by a desire or ef

fect to perpetuate segregation (R. 246) under the stan

dards set forth by this Court in Smith v. Morrilton School

District, supra. The undisputed testimony by the Superin

tendent, James D. Walker, the Principal of the Martin

School, Fred Martin, and plaintiffs’ educational expert,

Dr. Myron Lieberman, established that planning for the re

placement construction was done at a time when the school '

system was completely segregated and had no plans to alter

the practice (R. 53-54, 109-111, 181-182). The Superin

tendent admitted that the plans were directly based on

the “traditions” of the community and directly related to

the number of students who had attended each school under

segregated operation, and that the planning was affected

by the fact that some students were white and some were

Negro (R. 181-182). Dr. Lieberman testified that there

were no educational policy reasons which were ascer

tainable for the extraordinary plan of building two very

small school plants so close together, that having two such

small units rather than one larger one was positively in

jurious to all the students, and that the only possible rea

son for this strange plan was to perpetuate a dual segre

gated school system (R. 48-50, 55-58). The district court

said it “is not concerned here with whether it is wise or

economical for the District to maintain the two sites or to

32

construct elementary classroom buildings on both sites”

(R. 246), but the court ignored the fact that actions may

be so unwise and so uneconomical according to any rational

standard as to indicate that there is some other factor be

sides mere ignorance or incompetence at work in the situa

tion. See Smith v. Morrilton, supra. We believe the record

demonstrates that the court also erred in finding the good

faith intent of the school board to achieve desegregation

under a “freedom of choice” plan, which is critical to the

adequacy of such a plan (R. 246).

The court also erred in ignoring the fact that there is no

reasonable probability that the plan will produce substantial

desegregation as required under Dove v. Parham and Kemp

v. Beasley, supra. The Superintendent testified that he

expected only a few Negro pupils to elect to go to the for

merly all-white school, that he expected no white pupils to

elect to go to the still all-Negro school, and that he and

the school board had given no thought to how to achieve

desegregation of the system if the “freedom of choice”

plan did not work (R. 163, 174, 182). More importantly, he

was unable to explain how substantial desegregation could

possibly take place within the confines of the school system

as newly constructed even if large numbers of Negroes did

undertake the burden of desegregation, for if the white

pupils continued to elect to go to the predominantly white

school this would exhaust almost the entire capacity of

that school (R. 182-183). His statement that “the new

guidelines will do the facilitating that needs to be done”

suggests a mere pro forma reliance upon H.E.W. ap

proval of the “freedom of choice” plan in the abstract rather

than an actual intention to achieve substantial desegrega

tion. It additionally overlooks the problem that in a school

system with only two school sites which are for all prac

tical purposes right next to each other, and in which most

33

of the students live at some distance from either site, the

H.E.W. requirement that overcrowding be solved by assign

ment to the school closest to the pupil’s home is perfectly

compatible .witllrfhe, continued assignment of all whites to

thê . white, site .and substantially all Negroes to the Negro

site. Under Kemp v. Beasley, supra, the availability of suf

ficient facilities to allow substantial desegregation by'the

exercise of choices, and of a workable and factually non-

racial system of assignment in the absence of exercise of

choices by pupils or in the case of overcrowding, are critical

factors in the adequacy of a “freedom of choice” plan of

desegregation. As the matter now stands there is no space

for Negro pupils to attend the “white” complex if they wish

to do so. The boards’ reconstruction plan has insured that

unless this Court acts, significant desegregation will be

literally impossible for generations.

III.

T he D istric t C ourt M isconstrued th e Pow er and

D uties o f a F ederal C ourt o f E quity in Supervising D e

segregation and G ranting R elief to A ccom plish T hat

End.

Overwhelming evidence showed that the present plan of

desegregation of the Altheimer School District is the one

least calculated to produce any desegregation at all. Be

cause of the very simple configuration of this small dis

trict, it is rather apparent that the district has a clear-cut

choice between a system composed of one reasonably-sized

integrated elementary school and one reasonably-sized inte

grated high school, or a system composed of two inefficiently-

small segregated combination elementary and high schools.

The perpetuation of segregation as well as the educa

tional inefficiency and undesirability of the dual schools

34

(R. 44-56, 63-65) provides a clearly reasonable basis for

an order consolidating the schools, and providing thaLone

site, shall be used for an elementary school and the other

site for a secondary school. While it might have" beeii

somewhat easier to carry out such an order if appellants

: ; original request for an injunction against the replace

ment construction had been granted, nevertheless the new

buildings as constructed are adaptable to changed usages

(R. 196) and there is substantial additional land available

at both sites (R. 198). Whatever additional cost might be

involved in alteration can be balanced against the continued

extra operating cost of the inefficient dual system. Fur

thermore, the school board should not be allowed to defeat

Constitutional rights of another generation of Negro chil

dren on the basis that it might cost something additional

to vindicate those rights after it had previously sought

to defeat them.

In the course of its opinion, the district court said: “It

must be remembered that when two school sites rather than

one were established, the maintenance of dual school sys

tems was generally if not universally considered to be

constitutional, and there is nothing in the Constitution

which says that the District must now abandon one of its

sites” (R. 245). We submit that this statement by its

absolute form indicates a too narrow view of the power

and duties of a federal court of equity in supervising the

desegregation process and granting the relief required by

the Constitution. It is to be recalled that the enumeration

of administrative problems of re-organizing dual school

systems into unitary ones which the district courts were

directed to consider in the second Broivn decision specifi

cally included physical facilities and attendance areas.

This direction was intended to recognize not only that the

configuration of physical facilities in a school system might

prevent complete desegregation in the short run, but also

that substantial alteration of the configuration of physical

facilities might be necessary to achieve eventual complete

desegregation in the long run. It hardly needs to be added

that twelve years after the original Brown decision is the

“long run” and not the “short run”—it is exactly one whole

generation of public school students later. In this regard,

the district court’s approval of the “freedom of choice”

plan on the ground that it is an acceptable “transitional”

device even though “unconstitutional discrimination exists”

(R, 235) completely misses the point that the time at which

replacement construction is due clearly marks the end of

the “transitional period.” The Supreme Court explicitly

held that cognizable “transitional” problems referred to

administrative problems such as building capacity, and not

to minimizing the rate of desegregation simply because of

community hostility. Brown v. Board of Education, supra.

The Supreme Court, in the second Brown decision, di

rected that “in fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles.” 349 U.S. at

300. The general equity principle is that equity suffers no

right to be without a remedy or, alternatively, that in

equity jurisprudence there is no wrong without a remedy.

Leo Feist, Inc. v. Young, 138 F.2d 972 (7th Cir., 1944).

Because of this inherent general power and duty of a court

of equity to remedy a wrong, equity courts have broad pow

er to mold their remedies and adapt relief to the circum

stances and needs of particular cases. Bowles v. Skaggs,

151 F.2d 817 (6th Cir., 1946). The inherent power and duty

of federal courts of equity to effectively remedy wrongs is

graphically demonstrated by the construction according to

classical equity jurisprudence given by those courts to

their jurisdiction under 15 U.S.C. §4 to restrain violations

of the Sherman Antitrust Act. The test of the propriety

36

of measures adopted by the court is whether the required

remedial action reasonably tends to dissipate the effects

of the condemned actions and to prevent their continuance.

United States v. Bausch <£ Lomb Optical Co., 321 U.S. 707

(1943); United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319

(1947). Where a corporation has acquired unlawful

monopoly power which would continue to operate as long

as the corporation retained its present form, effectuation

of the Antitrust Act has been held even to require the com

plete dissolution of the corporation. United States v.

Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1 (1910); Schine Chain Theatres

v. United States, 334 U.S. 110 (1948).

Numerous decisions have indicated that the federal courts

construe their power and duties in the supervision of Con

stitutionally required school desegregation to require as

effective relief as in the antitrust area. While the initial

discretion in proposing a plan of desegregation remains

with the school board which administers the system, a fed

eral court of equity obligated to provide effective relief

for a Constitutional wrong cannot fail to order such relief

simply because the school board is unwilling to propose

any plan which will effectively desegregate the system.

The courts were directed in the second Brown decision to

consider the “adequacy” of all components of a proposed

desegregation plan, the implication of which is that if a

plan proposed by a school board is completely inadequate,

the court must itself determine and order an adequate plan.

In Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, Va.,

supra, the Supreme Court ordered a public school system

which had been closed to avoid desegregation to be re

opened. In Carr v. Montgomery County (Ala.) Board of

Education, 253 F. Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala., 1966), the court

ordered twenty-one (21) small inadequate segregated

schools to be closed over a two-year period and the stu-

37

dents reassigned to larger integrated schools. In Dowell

v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.D.

Okla., 1965), the court ordered the attendance areas of

pairs of six-year junior-senior high schools in adjacent

neighborhoods consolidated, with one school in each pair

to become the junior high school and the other to become

the senior high school for the whole consolidated area.

The Fifth Circuit has held that a district court has power

to enjoin “approving budgets, making funds available, ap

proving employment contracts and construction programs

. . . designed to perpetuate, maintain or support a school

system operated on a racially segregated basis.” Board of

Public Instruction of Duval Co., Fla. v. Braxton, 326 F.2d

616 (5th Cir., 1964) at 620. The Fourth Circuit has hehi

that a school construction program might be so directed

as to perpetuate segregation, and is therefore an appropri

ate matter for court consideration in spite of the possible

complexities involved. Wheeler v. Durham City Board of

Education, 346 F. 2d 768 (4th Cir., 1965). (It is to be noted

that such complexities are usually considerably less than

those involved in an anti-trust suit against a substantial

corporation.) And compare the manner in which this Court

fashioned relief in Smith v. Morrilton School District,

supra.

The district court very clearly indicated in its opinion

that it now regarded the United States Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare as having primary respon

sibility for supervising school desegregation (E. 238-245).

This is completely at odds with the general principle that

the vindication of Constitutional rights cannot depend upon

Executive action (or inaction) and with the specific hold

ing of this Court in Kemp v. Beasley, supra. Furthermore,

while H.E.W. Guidelines may be entitled to substantial

weight as general propositions of school desegregation

38

law, and as minimum standards for court-ordered desegre

gation plans because of problems which would otherwise

result, H.E.W. administrative approval of a particular de

segregation plan in a particular school district is entitled

to much less weight because it cannot be assumed that the

Department is able to ascertain all of the relevant facts

about the context of an individual school district’s desegre

gation plan in the way that a local court hearing is able

to do. Kemp v. Beasley, supra. Finally, appellants com

plained of a violation of their Constitutional rights; not