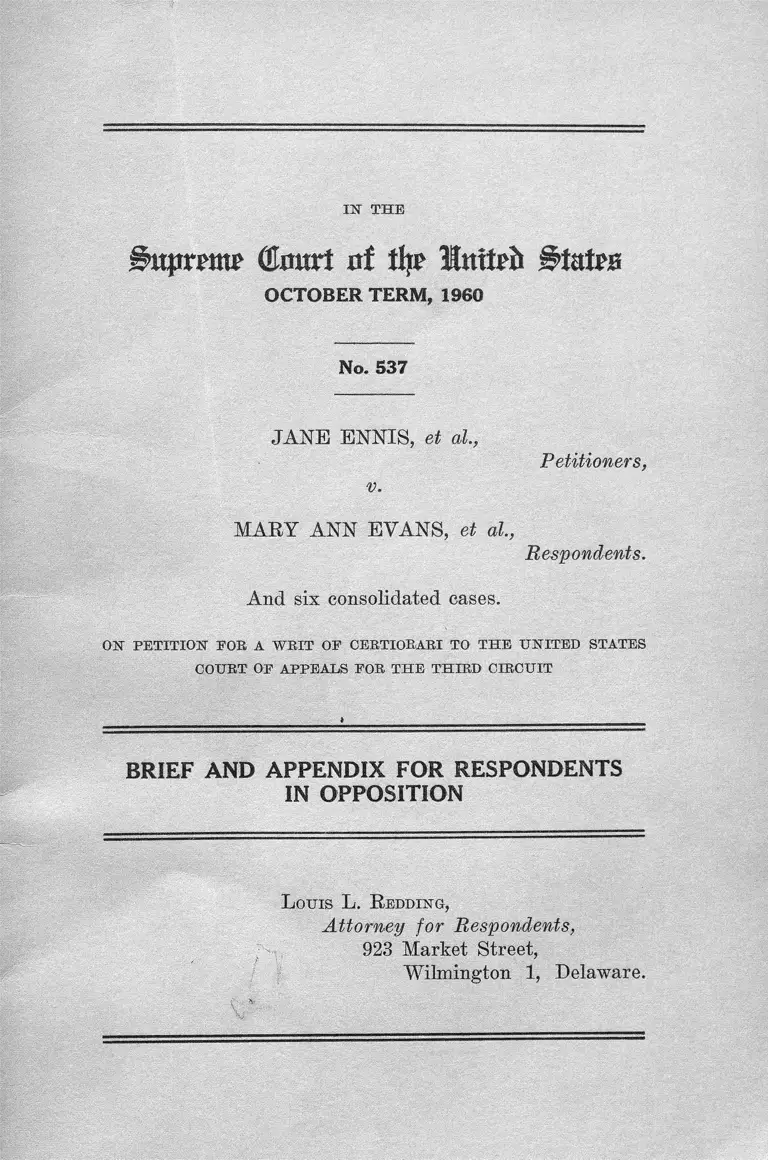

Ennis v. Evans Brief and Appendix for Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ennis v. Evans Brief and Appendix for Respondents in Opposition, 1960. da6a68e7-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/13bec656-29f5-48fc-88c5-dcb98ca3fe39/ennis-v-evans-brief-and-appendix-for-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN TH E

(tart itf tip Imirb ^tate

OCTOBER TERM, 1960

No, 537

JANE ENNIS, et al.,

v.

Petitioner s,

MARY ANN EVANS, et al.,

Respondents.

And six consolidated cases.

ON PETITION FOII A W RIT OF CEETIOBARI TO TH E UNITED STATES

COURT OP APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR RESPONDENTS

IN OPPOSITION

Louis L. R e d d i n g ,

Attorney for Respondents,

923 Market Street,

Wilmington 1, Delaware.

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B elow ...................................................... 2

Jurisdiction .................................................................. 2

Question Presented ......................................... 2

Statement ...................................................................... 2

A rgu m en t

I—The decision below was correct because the

District Judge had invalidly assumed to vary

the prior mandate of the Court of Appeals.. 8

II—Certiorari should be denied because any con

flict arises from departure of the decision of

the Sixth Circuit, and not by the instant de

cision, from principles this Court settled in

Brown .............................................................. 11

III—No meritorious reasons are advanced for

granting certiorari......................................... 14

Petitioners’ Reasons 2-4, Inclusive........... 14

Petitioners’ Reason 5 ............................ 15

Petitioners’ Reason 6 ................................ 15

Petitioners’ Reason 7 ................................ 16

Petitioners’ Reason 8 ................................ 16

Petitioners ’ Reason 9 ........................ 17

Conclusion .......................................................... 19

11

A p p e n d i x

p a g e

Complaint Filed against State Board of Educa

tion, State Superintendent of Public Instruction,

and the Board of Education of the Laurel Spe

cial School District, printed as Model of Com

plaint Filed in All Seven A ctions....................... BA-1

Answer of State Board of Education and State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, Printed as

Model of Answer of These Defendants in all

Seven Actions ....................................................... BA-5

Answer of Board of Education of Laurel Special

School District, Printed as Model of Answers

Filed by Local School Boards in All Seven

Actions .................................................................. BA-8

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District

Judge Leahy on April 5, 1957 ..............................BA-12

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District

Judge Leahy on July 9, 1957, on Motions for

Consolidation and for Summary Judgment

against the State Board of Education and the

State Superintendent of Public Instruction___BA-14

Excerpt from Mandate of Court of Appeals, 3rd

C., Issued June 30, 1958, and Subsequently Be-

issued ..................................................................... BA-18

Opinion of Court of Appeals, 3rd C. re Becall of

Mandate, Filed July 23, 1958 ............................ BA-19

Order of Judge Layton of November 19, 1958 ___BA-20

I l l

Cases Cited

PAGE

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F. 2d 361 ................................... 14

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d 3 3 ...................... 15

Booker v Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d

689, cert. den. 353 U. S. 965 ...................................... 15

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

482 ............................................................................... g

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S.

294 ................................................................ 8,12,13,14,17

Buchanan v. Evans, 358 U. S. 836 ................ 6

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ............................13,14,15

Ennis v. Evans, 81 S. Ct. 2 7 ...................................... 8

Evans v. Buchanan, 172 F. Supp. 508 ......................... 3

Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, 71 S. Ct. 303 . . . . 15

In re Sanford Fork and Tool Co., 160 U. S. 247 ...... 8

Jackson v. Bawdon, 235 F. 2d 93, cert. den. 352 U. S.

925 ............................................................................. 15

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nash

ville, 270 F. 2d 209 ................................................... 11,12

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U. S. 268, 71 S. Ct. 325 15

Pierre v. State of Louisiana, 306 U. S. 354, 59 S. Ct.

536 ............................................................................... 15

Sibbald v. United States, 27 U. S. 487 ....................... 9

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 4 9 .................................... 15

Statute Cited

50 Laws of Delaware, Ch. 643 ..................................... 4

I S THE

&u$mw (£mxt of tty Inttei* BMm

OCTOBER TERM, 1960

No. 537

------------- o—-----------

Jane E n n is , et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

M a r y A n n E v a n s , et al.,

Respondents.

And six consolidated cases.

ON PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO TH E UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

■----------------------0----------------------

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Seven class actions were brought in the United States

District Court for the District of Delaware by Negroes

against the State Board of Education of the State of

Delaware and its employee, the State Superintendent of

Public Instruction, to enjoin exclusion on grounds of race

from public schools in two of the three counties of that

State. On motion of the plaintiffs the decree of the District

Court consolidated the cases and granted summary judg

ment enjoining the discriminatory exclusion and ordering

the defendants, petitioners here, immediately to admit the

plaintiffs to desegregated education. The United States

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit affirmed; this Court

denied certiorari.

On remand to the District Court, a different District

Judge undertook to vary the mandate of the Court of

2

Appeals so as to deny desegregated education to the named

plaintiffs and protract desegregation through approval of

a grade-a-year desegregation plan. On appeal by the school

children, the Court of Appeals reversed. The school

children, respondents here, now oppose the petition for

a writ of certiorari to review that reversal.

Opinions Below

The relevant opinions below are the following: 152 F.

Supp. 886, R. 16a-21a (A12-16), which is the opinion of

July 15, 1957, of District Judge Leahy; the affirmance of

that opinion, at 256 F. 2d 688 (A32-43); the opinions of

District Judge Layton, on remand, at 172 F. Supp. 508

(A44-57) and 173 F. Supp. 891 (A58-60); the reversal,

at 281 F. 2d 385 (A76-81); 281 F. 2d 390 (A99-109).

Jurisdiction

The basis of jurisdiction is adequately set forth in

the petition.

Question Presented

Whether this Court should review a judgment of a

Court of Appeals reversing the judgment of a District

Court entered after remand and assuming to alter the

mandate of the appellate court by ordering a grade-a-year

plan of public school desegregation, when the Court of

Appeals had affirmed the District Court decree requiring

immediate admittance to desegregated public education.

Statement

The petition for certiorari to which this brief is opposed

is the second tiled in this litigation by the members of the

Delaware State Board of Education (hereinafter referred

3

to as “ State Board” ) and the State Superintendent of

Public Instruction (hereinafter, “ State Superintendent” ),

seeking review of two successive judgments of the Court

of Appeals designed to effect immediate admittance of

plaintiffs to racially nondiscriminatory public education

and ordering these petitioners promptly to desegregate

public schools in Delaware.

This litigation originated with complaints filed (RA.

1-5) * in the District Court in Delaware on May 2, 1956,

as seven separate class actions by Negro children and their

guardians for injunctive relief against exclusion, because

of race, from public schools in seven school districts in

Kent and Sussex Counties in Delaware. Geographically

these are the more southerly of that state’s three counties.

See footnote 2, opinion of Layton, D. J., in Evans v.

Buchanan, 172 F. Supp. 508, 511 (A47).*

Defendants in each case were the State Board and State

Superintendent; and in each case also other defendants

were the members of the local, or district, school board in

the several school districts where the respective groups

of plaintiffs reside.

In each case, the Attorney General of Delaware, repre

senting the State Board and State Superintendent, filed

an answer for those defendants. Their answer in each

case admitted that plaintiffs had “ not been accepted” in

the local schools, that the State Board and State Superin

tendent had not complied with plaintiffs ’ request to desegre

gate the local schools, and asserted that desegregation,

under regulations promulgated by the State Board, had

to be initiated by local school boards (RA6-7).

* "A ” followed by page number refers to petitioners’ appendix;

“ R A ,” to respondents’ appendix.

4

In each of the actions also, the local school board of the

district involved, represented by its own counsel,1 filed an

answer, offering, in essence, this as a defense:

‘ ‘ The opposition to school integration is so wide

spread and of such an emotional character that any

action apparently initiated by the local board looking

toward integration, and not clearly forced upon the

local board by some agency higher in authority than

these defendants, would be either ignored completely

or overridden by force.” (RA 9)

Plaintiffs moved for consolidation of the seven cases

and for summary judgment against the State Board and

State Superintendent, and these motions were granted on

July 15, 1957 (A12-16).

The District Court (Leahy, Chief Judge) had become

fully cognizant from the proceedings before it that mutual

shifting of responsibility for desegregation by State Board

and local boards back and forth between each other was the

basic cause of the total denial of plaintiffs’ constitutional

rights (RA12-17). However, Judge Leahy found that it

was the State Board’s responsibility to desegregate, since

it had general control and supervision over all public

schools in Delaware. He also found that its admissions of

continued racial segregation in the schools removed “ all

dispute as to this issue.” He declared that, “ The regula

tions of the State Board cannot be permitted to be wielded

as an administrative weapon to produce interminable delay.

* * * [T]he Supreme Court fixed the law on this problem

over three years ago. * # * [N]o appreciable steps have been

taken in the State of Delaware to effect full compliance

with the law. * * # [T]he right of plaintiffs to public educa

1 The Delaware General Assembly, by act approved July 13,

1956, appropriated $35,000 “ to be allocated to school districts incur

ring extraordinary legal expenses,” (See 50 Laws of Delaware Ch.

643) to finance the local school boards’ defense.

0

tion unmarred by racial segregation is immutable. * * *

[E]aeh state faces problems indigenous to its own circum

stances. * * * [Cjireumstanees in Delaware require racial

desegregation to become a reality simultaneously through

out all communities” (A.13, 14).

He decreed plaintiff's entitled to racially nondiserimi-

natory admittance to the schools involved “ no later than

the beginning of or sometime early in the Fall Term of

1957,” and he permanently enjoined the State Board and

State Superintendent from refusing such admittance to

the named plaintiffs. Further, to “ obtain and effectuate

admittance * * * and education of said minor plaintiffs,”

Judge Leahy ordered the State Board and State Superin

tendent to file within 60 days a “ plan of desegregation

providing for the admittance, enrollment and education, on

a racially nondiscriminatory basis, for the Fall Term of

1957,” of pupils in all public schools in Delaware not there

tofore desegregated.

The local boards, on the incorrect assumption that Judge

Leahy’s order was directed against them, moved to amend

that order. Reference to such motion shows that it

expressed the conclusion that members of the local boards

were deprived of “ their ‘ day in court’ ” because they

conceived the order as directed against them even though

“ no motion for summary judgment was made or pending

against these individual defendants.” See A17, especially

paragraphs (1), (2) and (3).

Thereupon, on August 6, 1957, Judge Leahy held a con

ference with counsel for all parties (A18-30). There he

fully elucidated his order of July 15, stating, inter alia,

that his “ Directions for compliance are [were] aimed spe

cifically at the State Board of Education” (A18-19). They

were the defendants “ encompassed within the motion for

summary judgment,” he said, and “ The precise matter

for decision before me is on the motion for summary judg

ment” (A28).

6

At that conference the local board’s counsel conceded

that they had misinterpreted2 Judge Leahy’s order (A22-25)

and voluntarily withdrew their motions to amend it (A29-

30).

The order of July 15, 1957, was then stayed pending

decision of an appeal by the State Board and State Super

intendent.3 * * * * 8 The unanimous affirmance (A32-43) by the

Court of Appeals was filed on May 28, 1958, which date

was, for all practical purposes, at the end of the school

term which began in the Fall of 1957, to which term plain

tiffs had been ordered admitted. Necessarily the Court, in

affirming, vacated the then post factum dates set forth in

Judge Leahy’s decree for submitting a general plan of

desegregation of the schools but “ in all other respects”

sustained that decree (A43).

The mandate of the Court of Appeals, issued on June

30, 1958, was recalled by the Court, Judge Kalodner dis

senting (RA19), to permit the State Board and State

Superintendent to petition for certiorari, which this Court

denied on October 13, 1958. Btichanan v. Evans, 358 U. S.

836.

2 The transcript of the conference, read in its entirety and in

conjunction with the motions to amend, reveals that counsel for the

local boards had the misconception that their clients would be in

peril of contempt if they did not admit plaintiffs to nondiscriminatory

education early in September, 1957, even though the State Board

then had not furnished an inclusive plan o f desegregation for all

schools.

8 The local boards’ counsel filed briefs and participated in oral

argument urging the Court of Appeals to sustain Judge Leahy’s

decree; subsequently they filed briefs opposing State Board’s first

petition for certiorari. Still later, when plaintiffs appealed on the

ground that the grade-a-year plan ordered by District Judge Layton

excluded them from racially nondiscriminatory education and did

not conform to the Court of Appeals mandate affirming Judge Leahy’s

decree, the local boards allied themselves with the State Board in

the Court of Appeals; and they are here so allied.

7

On October 27, 1958, the recalled mandate of the Court

of Appeals was reissued. The Fall Term of 1958 then having

commenced in the public schools of Delaware, plaintiffs’

nondiscriminatory admittance, originally ordered for the

Fall Term of 1957, was avoided and delayed a second full

year. Meanwhile, Chief District Judge Leahy had retired,

152 F. Supp. IX, fn. 2, and the cases were assigned to Dis

trict Judge Layton.

The District Court was commanded by the mandate of

the Court of Appeals to proceed in conformity with the

opinion and judgment of the latter Court (EA18) in

its affirmance of Judge Leahy’s decree. However, despite

the express command of the mandate, Judge Layton, on

November 19, 195$, deleted language prescribing admit

tance of the named plaintiffs to racially nondiscriminatory

education at the Fall Term of 1957, that is, the school term

next ensuing the original judgment, and did not substitute

any date for plaintiffs’ admittance. Yet, after this deletion

of a time for their admittance, the order still contained lan

guage stating that plaintiffs were entitled to racially non

discriminatory admittance and education in the designated

schools and enjoining the defendants from refusing them

such admittance (EA20). Judge Layton further or

dered defendants to submit to the Court within 105 days,

later changed to 112 days, a plan of desegregation and set

March 17, 1959, for a hearing on that plan.

After this hearing, Judge Layton, on April 24, 1959,

filed an opinion (A44-57) approving a grade-a-year plan

of desegregation to begin in September, 1959, and to be

consummated in 1970 (A63-64). Since this plan initiated

desegregation with Grade 1, no child who had begun Grade

1 or any higher grade prior to September, 1959, could ever,

under the plan, be admitted to racially nondiscriminatory

public education in Delaware. The plan thus necessarily

excluded all of the plaintiffs from desegregated education

On July 6, 1959, District Judge Layton signed an order

instituting the plan (A61-62).

Plaintiffs appealed, on the grounds (A76), first, that

the order entered by Judge Layton invalidly assumed to

vary the mandate of the Court of Appeals, which required

immediate statewide desegregation and, additionally, that

the plan of desegregation ordered by Judge Layton was in

conflict with the intent and substance of the decisions of

this Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347

U. S. 4-82, 349 U. S. 294, in that the plan deprived the

plaintiffs forever of access to desegregated public educa

tion and failed to satisfy the “ with all deliberate speed”

and “ prompt and reasonable start” requirements in the

Brown ruling.

The Court of Appeals reversed, categorically sustain

ing both grounds of appeal (A76-81).

Rehearing was denied the defendants on August 29,

1960, (A96-109). This Court, on September 1, 1960, denied

a stay of execution of the judgments below, Ennis v. Evans,

81 S. Ct. 27, while defendants pursue their present petition

for certiorari.

ARGUMENT

I

The decision below was correct because the Dis

trict Judge had invalidly assumed to vary the prior

mandate of the Court of Appeals.

A cardinal principle governing the relationship of

subordinate to superior courts is applicable to preclude

review by the Court of this, the petitioners ’ second petition

for certiorari. It bars at the threshold consideration of

in Delaware, since all of them were in attendance in schools

when the actions were filed in May, 1956.

9

any of the reasons they advance for granting the writ.

This principle affirms that a subordinate court is bound

by the mandate, including the decision, of an appellate

court as the “ law of the case” and cannot vary it “ nor

intermeddle with it further than to settle so much as has

been remanded.” Sibbald v. United States, 27 U. S. 487;

In re Sanford Fork and Tool Co., 160 U. S. 247, 255. Review

of the judgment below would trench upon that principle,

since that judgment was evoked and occasioned by the

disinclination and refusal of the District Court to observe

and effectuate the mandate transmitted to it.

Judge Leahy’s decree of July 15, 1957, ordered plain

tiffs’ “ admittance, enrollment and education” on a racially

nondiscriminatory basis in public schools in their respective,

designated school districts “ no later than the beginning

of or sometime early in the Fall Term of 1957” (A15),

and enjoined the defendants from refusing such admittance.

It is apparent from the transcript of the conference

of August 6, 1957 (A21-30), that both the State Board

and the local boards understood that decree to require what

was tantamount to plaintiffs’ immediate access to non-

segregated education in the designated school districts.

At that conference no one disputed that as the meaning

or effect of the decree. The only question raised by the

boards was as to who were the defendants required to

give compliance.

This is made abundantly clear by the contribution made

to the colloquy by the then Attorney General, who stated

that he thought the State Board’s “ reason for instructing

me to take an appeal was because of this confusion in

the minds of many Local Boards as to the impact of your

Honor’s order” (A26). What he was saying was that the

local boards were uncertain as to whether they were the

defendants commanded by the order, and the State Board

had instructed him to take an appeal to find out. That

10

uncertainty being clarified by Judge Leahy, the Attorney

General indicated that an appeal might not be necessary

(A28-29). The Attorney General did not view the order

as not giving plaintiffs the right to immediate relief. His

concern then was as to whether the State Board could have

an extension of time to comply (Id. 29).

Judge Leahy’s statements at the conference reinforced

the immediacy implicit in the order itself, for the only

elasticity given there to the time for compliance is that

contained in his words: “ I could not sit here in this chair

and tell you to do that on September 1st or September

12th or September 23rd.” By thus clearly confining the

time of plaintiffs’ admittance to a period “ no later than

the beginning of or sometime early in the Fall Term of

1957,” he re-emphasized the immediatism prescribed in

paragraph 2 of the decree (A15). In the time-circumstance

context in which the decree was formulated, and in view

of Judge Leahy’s adverse criticism of the “ delay” and

the “ deprivation” of plaintiffs’ constitutional and “ invio

late” rights, his decree definitely and unmistakably ordered

plaintiffs’ immediate admittance.

That District Judge Layton did assume to vary this

decree and the Court of Appeals mandate affirming it

when he ordered a plan beginning desegregation only wdth

pupils entering Grade 1 and excluding all the plaintiffs

forever from racially nondiscriminatory public education

in Delaware, is patent. Clearly it is impermissible and

invalid for a subordinate court to attenuate or change the

mandate of an appellate court, and the unauthorized vari

ance undertaken by the subordinate court the Court of

Appeals rejected in these words:

“ The court below concluded in substance that

desegregation at a more rapid rate than that

approved by it would prove to be a disruptive and

futile proceeding which might do great harm to

the Delaware School System.

11

“ We cannot agree. We affirmed the decree of

Judge Leahy which in plain terms required statewide

integration of the public school system of Delaware

in all classes by an adequate plan by the Fall Term

1957, and which enjoined designated defendants from

refusing admission to Negro children on a racially

discriminatory basis. The plan approved by the

court below is not in accordance with Judge Leahy’s

decree or with the mandate of this court,” (A77)

Thus, the judgment which petitioners seek now to have

this Court review eventuated only because of the District

Court’s disagreement with the prior mandate directed to

it by the Court of Appeals.

Granting the petition in these cases would involve this

Court in considering whether to reverse an order of the

Court of Appeals and reinstate an order of a district court

which the appellate court has itself repudiated and reversed

as not in accordance with its mandate to the subordinate

court. It would reflect upon the right of an appellate

court to safeguard its mandate. No principle governing

the relationship of courts to each other could be sounder,

less amenable to compromise or more productive of chaos

if compromised than that a subordinate court may not

vitiate the clear mandate of an appellate court or derogate

from it. Moreover, to breach the rule in this instance would

destroy forever a constitutional right of the plaintiffs.

II

Certiorari should be denied because any conflict

arises from departure of the decision of the Sixth Cir

cuit, and not by the instant decision, from principles

this Court settled in Brown.

The decision in Kelley v. Board of Education of the

City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th C., 1959), differs in

result from the instant case in that there, on appeal by

Negro school children, an order of the district court

12

approving a grade-a-year plan of desegregation was

affirmed. The differing results in the two cases are refer

able principally to differing circumstances and facts. A

notable difference has already been adverted to. Prelimi

narily and entirely independent of undertaking an evalua

tion of the evidence, the Third Circuit had to confront a

situation in itself sufficient for reversal, namely, that more

than two years earlier it had affirmed a judgment of the

district court ordering immediate desegregation and, on

remand, a district court judge had sought to override its

mandate.

In a strict sense, it is hardly correct to contend, as do

petitioners, that there is a “ departure from precedent,”

implying conflict of decision, where two courts of appeals

have reviewed dissimilar evidence adduced before district

courts in their respective circuits and have come to opinions

producing diverse end results. At most, it can be said

that each appellate court was impelled to its conclusion

by the peculiar nature of the evidence reviewed by it.

The Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit in the

Kelley case concluded that there was evidence to support

the district court’s judgment. In the instant case in the

Third Circuit the appeals court found the evidence of

many of the proponents of the grade-a-year desegregation

plan “ fraught with unreality” (A77). Besides, the latter

court disagreed with the district judge as to evidence of

disparity in intelligence, or academic achievement poten

tials. The district judge deemed this a partial justification

for the plan, while the appellate court thought it not of

such a degree as to prevent mutual desegregated education.

Because there is a very obvious divergence of end

result in the two decisions, this divergence could be over

simplified, in broad terms, to characterization as a conflict

of decision. In such terms, it can be said that the Sixth

Circuit has held that a grade-a-year plan of public school

13

desegregation, protracting the process over a period of

more than a decade, when formulated by a school board

and approved by a district court, is not unreasonable

vis-a-vis Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349

U. S. 294 (1955), if the school board’s judgment in formulat

ing the plan is supported by evidence. The Third Circuit,

on the other hand, has held that such a plan, approved

by a district court and ordered to begin in the Fall of

1959, does not follow the intent and substance of the

rulings of this Court in Brown.

There is a further divergence between the two cir

cuits. In arriving at its decision, the Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit acquiesced in the acceptance by the

district court of evidence of community disagreement,

stemming from tradition, custom and practice hostile to

a changeover from a segregated school system. The accept

ance of such evidence, however, was in plain disregard

of the admonition of this Court in Brown, pointedly reiter

ated in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958), that “ the

vitality of these constitutional principles cannot be allowed

to yield simply because of disagreement with them.”

On the other hand, the Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit, in rejecting the district court’s approval of the

twelve-year plan, was adversely critical that “ one of the

main thrusts of the opinion of the court below” ’ (A'79),

and this is abundantly apparent from an examination of

Judge Layton’s opinion at A 11-57. derived from the accept

ance and consideration given to testimony as to racial

prejudice and traditions, customs and practices of racial

segregation in the communities involved. Chief Judge

Biggs, writing the opinion for the Court of Appeals, referred

to Cooper v. Aaron, supra, and commented that this Court

“ has made it plain * * * that opposition is not a support

able ground for delaying a plan of integration of a public

school system.” He continued, quoting this Court in

Cooper v. Aaron:

14

“ ‘ The constitutional rights of respondents # *

are not to be sacrificed or yielded to * * * violence

and disorder * * V We are bound by that decision.”

(A80) (Italics supplied.)

The contrast between the circuits is this: where a major

justification for the protracted plan was founded, not on

a necessity for time to solve proven administrative prob

lems, as defined by this Court in the second Brown decision,

but on deference to community disagreement and hostility,

factors ruled noncognizable by this Court, the Sixth Circuit

approved the grade-a-year plan and the Third Circuit

disapproved it. Of this conflict of view we respectfully

urge this Court to take notice and to resolve it, not by

granting the petition for certiorari, but by denying it and

accompanying such denial with specific reaffirmation of the

principles which this Court has enunciated and to which

the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit specifically

has given adherence.

It is submitted that the foregoing considerations fully

support a denial of the petition. However, to the extent

that the reply already set forth does not explicitly or im

pliedly embrace the reasons petitioners advance for grant

ing the writ, we shall undertake below to deal with them.

I I 1

No meritorious reasons are advanced for granting

certiorari.

Petitioners’ Reasons 2 4, Inclusive

In remanding the cases subsumed under Brown v. Board

of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) to the courts

which originally heard them to judicially appraise imple

mentation by school authorities of the constitutional prin

ciples declared in Brown, this Court did not purport to

preclude review by appropriate appellate courts. Nor

15

have appellate courts deemed their normal reviewing

function suspended in this type of case. Aaron v. Cooper,

243 F. 2d 361 (5th Cir., 1957); Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F. 2d

33, (1958); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1957); Booker v.

Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir., 1957)

cert. den. 353 U. S. 965; Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93

(5th Cir., 1956) cert, denied 352 U. S. 925 (1956).

Petitioners’ Reason S

This reason, like the three immediately preceding it, in

essence, challenges the right of the Court of Appeals to

make its own evaluation of the factual basis of the judgment

of the district court. That the findings of fact of a lower

court, in a case involving constitutional rights, should be

re-examined and appraised by an appellate court has been

clearly recognized by this Court:

“ Yet, when a claim is properly asserted—as in

this case—that a citizen has been denied the equal

protection of his country’s laws on account of his

race, it becomes our solemn duty to make independent

inquiry and determination of the disputed facts—

for equal protection to all is the basic principal upon

which justice under law rests.” Pierre v. State of

Louisiana, 306 U. 8. 354, 358, 59 Ct. 536, 539.

See also Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 II. S. 268, 271, 71 S.

Ct. 325, 327; Feiner v. New York, 340 U. S. 315, 316, 71 S. Ct.

303, 304; Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49, 50-51.

Petitioners’ Reason 6

In its opinion of May 28, 1958 (A32-43) affirming the

judgment of July 15, 1957, of District Judge Leahy, the

Court of Appeals stated that that judgment “ was designed

to relieve the appellants [State Board] of passivity and

compel them to go forward with desegregation of the Dela

ware schools,” Id. at 42. The district court opinion thus

affirmed had noted “ the record of inactivity” of the State

16

Board “ in failing to negotiate a prompt and reasonable

start toward full compliance.” With the same inactivity

prevailing on August 29, 1960, when the amended judgment

of the Court of Appeals was filed, it is wholly reasonable

that at that late date, “ admission to public schools on a

racially nondiscriminatory basis with all deliberate speed”

required that the still-segregated Delaware schools be

ordered “ wholly integrated.” As against the contention

that the Court of Appeals by this order “ exceeded the

bounds of the federal judiciary,” it is respondents’ position

that the affirmance purports to accomplish no more than

did Judge Leahy’s decree three years earlier. As indi

cated in the respondents’ Statement, supra p. 6, Fn. 3, some

of the petitioners, viz., the local school boards, contended in

the Court of Appeals for affirmance of that order and later

opposed review by this Court. The other petitioners, the

State Board and State Superintendent, when they sought

to have that earlier decree reversed and that failing, sought

review here, did so only on the ground that the State Board

was without statutory power to carry out the decree. No

other opposition to its scope was made.

Petitioners’ Reason 7

The short answer to the contention that Judge Leahy’s

order required nothing specific as regards speed in the

accomplishment of desegregation of all Delaware schools

is that paragraph 5 of his decree called for racially non

discriminatory “ admittance, enrollment and education” in

the Fall Term of 1957 (A15-16), and his subsequent inter

pretation of this confined the time to September, 1957.

(A22)

Petitioners’ Reason 8

Petitioners ’ contention here relates to the aspect of the

judgment below which orders admittance of the named

plaintiffs to desegregated education in September, 1960,

and postpones until September, 1961, admittance of all

17

This Court in its mandate opinion in Brown pointed

out “ the personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission

to public schools as soon as practicable on a nondiscrimina-

tory basis.” The import of the judgment below is that no

sufficient showing was made that immediate admittance

of the plaintiffs was impracticable. The court below had

affirmed two years earlier a decree of the district court

ordering immediate admittance to nondiscriminatory educa

tion of the named plaintiffs and all members of the class.

It was entirely within the province of the Court of Appeals

again to have ordered the same total, simultaneous admit

tance for the Fall Term of 1960. Surely petitioners have

no reasonable or valid basis of objection to the Court’s

forbearance to order all that it might have ordered in the

way of effectuating the rights of all members of the class

represented by respondents, especially since this forbear

ance benefits only the petitioners, in that it affords them

more time to prepare to comply.

Petitioners’ Reason 9

Petitioners seem to inveigh against the judgment below

on the implied ground that it orders parties not before

the Court to desegregate schools. This implication is not

correct.

Some of the petitioners now seeking certiorari, viz., the

local school boards, in argument, written or oral, for affirm

ance of Judge Leahy’s decree, in 1958, when the State

Board appealed to the Court of Appeals, took a position

consistent with their pleadings in the district court. Local

Board answers to the complaint (RA9) had averred

that all the communities in Delaware where school segrega

tion prevailed, namely, those in southern Delaware, are

“ essentially similar sociologically, so as to constitute what

other Negro children whom petitioners were segregating by

race in the schools.

18

amounts to a single community.” Therefore, they con

tended, in order to make “ integration” effective in the

seven communities whose local school boards were joint

defendants with the State Board, it was necessary that

desegregation be “ general and schematic,” applying not

merely to those seven communities, but throughout all

segregated school districts in Delaware. Id.

Judge Leahy adopted this view and, as we have previ

ously mentioned, concluded that circumstances in Delaware

did require simultaneous desegregation throughout all

segregated school districts in the State. He concluded fur

ther that the statutes gave control over all Delaware public

schools to defendant State Board. As paragraph 5 of his

decree (A16) states, “ to further obtain and effectuate”

desegregated education, he ordered the defendants having

the power, State Board, to desegregate throughout this

southern Delaware area.

In reversing District Judge Layton’s unauthorized order

the judgment below has the effect of restoring the decree

of Judge Leahy which the Court of Appeals formerly

had affirmed. That decree orders the appropriate defend

ants, the State Board and State Superintendent, who

administer all Delaware schools, to desegregate all segre

gated schools. It does not, as implied by petitioners, com

mand persons not parties to the action, nor purport to

command compliance by school boards in nonsegregated

districts. Such simultaneous desegregation of the sociologi

cally similar, segregated school communities not among

the seven school districts in this litigation was precisely

what the local boards that have joined the State Board

in the petition before this Court, both to Judge Leahy and

in the earlier appellate history of this litigation, repre

sented was the only effective procedure for bringing about

desegregation in Delaware. That they should now have

deserted that position and have allied themselves with the

19

State Board in seeking to uphold the twelve-year plan

gives rise to the inference that they want merely to prevent

the plaintiffs from realizing their constitutional rights and,

presumably, out of deference to hostility they have asserted

exists, so protract desegregation as to render it ineffective,

CONCLUSION

Petitioners seek review of a judgment entered by

the Court below to displace unauthorized interference

with its mandate and to prevent obliteration of con

stitutional rights of the respondent school children.

The decision below was clearly correct and no inter

est of justice requires review. It is respectfully urged

that the petition for certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis L. R e d d i n g ,

Attorney for Respondents.

RA-1

APPENDIX

Complaint Filed against State Board of Education,

State Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the

Board of Education of the Laurel Special School Dis

trict, printed as Model of Complaint Filed in All

Seven Actions.

1. (a) The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1331. This action

arises under the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitu

tion of the United States, section 1 and Title 42, United

States Code, section 1981. The matter in controversy

exceeds, exclusive of interest and costs, the sum or value of

Three Thousand Dollars ($3,000.00).

(b) The jurisdiction of this Court is also invoked under

Title 28, United States Code, section 1343. This action is

authorized by Title 42, United States Code, section 1983,

to be commenced by any citizen of the United States or

other person within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the

deprivation, under color of a state law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, custom or usage, of rights, privileges and immu

nities secured by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Consti

tution of the United States, section 1, and by Title 42,

United States Code, section 1981, providing for the equal

rights of citizens and of all persons within the jurisdiction

of the United States.

(c) This is an action for an interlocutory and per

manent injunction restraining, upon the ground of uncon

stitutionality, the enforcement of provisions of the admin

istrative order and regulations of the defendants, as mem

bers of the State Board of Education, and the customs,

practices and usages of defendant members of the State

Board of Education and of defendant members of the

RA-2

Board of Education of the Laurel Special School District

requiring segregation in public education in the Laurel

Special School District, in Sussex County, State of Dela

ware, by restraining defendants from enforcing such admin-

inistrative orders and regulations, customs, practices and

usages.

2. Plaintiffs bring this action pursuant to Rule 23 (a)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure for themselves and

on behalf of all Negroes similarly situated, whose numbers

make it impracticable to bring them all before the court;

they seek common relief based upon common questions of

law and fact.

3. Plaintiffs are among those classified as “ colored,”

of Negro blood and ancestry, and are citizens of the United

States and the State of Delaware. They are residents of

the Town of Laurel, State of Delaware. Adult plaintiffs

are parents or guardians of minor plaintiffs.

4. (a) Defendants Madeline Buchanan, Clayton A.

Bunting, Byard Y. Carmean, Irvin S. Taylor, Vincent A.

Theisen and Marvel 0. Watson, are members of the State

Board of Education, an administrative agency of the State

of Delaware, and as such are under a duty to determine the

educational policies of the State of Delaware and to adopt

rules and regulations for the administration of the free

public school system of the State of Delaware, to appoint

such professional and other assistants as are necessary

for carrying out the policies, rules and regulations of the

State Board of Education, and to decide all controversies

and disputes involving the administration of the public

school system.

Complaint Filed against State Board of Education, State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Board of

Education of the Laurel Special School District

RA-3

(b) Defendant George R. Miller, Jr., is Executive Sec

retary of the State Board of Education and State Super

intendent of Public Instruction, a statutory officer of the

State of Delaware.

(c) Defendants William E. Prettyman, Ford M. War

rington, Harry G. McAllister and W. Pierce Ellis are mem

bers of the Board of Education of the Laurel Special School

District in Sussex County, State of Delaware, are vested

with the duty of the general administration and supervision

of the free public schools and the educational interests of

the said Laurel Special School District and with the fur

ther duty to determine the educational policies of said Spe

cial School District, to appoint a Superintendent of Schools

and other employees of said Special School District, and to

decide all controversies and disputes involving the rules

and regulations of the Laurel Special School District and

the proper administration of the public schools of said

Special School District.

5. In August, 1955, adult plaintiffs petitioned the

defendant members of the Board of Education of said

Laurel Special School District to take immediate steps to

reorganize the public schools under the jurisdiction of said

Board of Education on a racially nondiscriminatory basis

and to eliminate racial segregation in said schools, so that

children of public school age be not denied admission to

said schools or be required to attend any school, solely

because of race or color.

6. Defendant members of the Board of Education of

Laurel Special School District have officially stated, inter

alia, that “ the plans released from Federal and State

Authorities have not been specific as to whether compulsory

Complaint Filed against State Board of Education, State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Board of

Education of the Laurel Special School District

KA-4

desegregation shall be in effect” and have stated further

that they have “ advised the people and the State Board

of Education that segregation shall be preserved as long

as it does not violate the law,” and have failed and refused

to reorganize the public schools under their jurisdiction

on a racially nondiscriminatory basis and to eliminate racial

segregation in said public schools.

7. On February 10, 1956, on behalf of plaintiffs, the

failure and refusal of defendant members of the Board of

Education of the Laurel Special School District to reor

ganize the public schools in the Laurel Special School Dis

trict on a racially nondiscriminatory basis and to eliminate

racial segregation in said public schools was called to the

attention of defendant members of the State Board of Edu

cation and the latter were requested immediately to deseg

regate the public schools of the Laurel Special School

District.

8. On March 15, 1956, defendant members of the State

Board of Education, by official action, unanimously refused

to comply with the plaintiffs’ request to desegregate said

public schools.

9. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated suffer and are

threatened with irreparable injury by the acts herein com

plained of. They have no plain, adequate or complete rem

edy to redress these wrongs other than this suit for an

injunction. Any other remedy would be attended by such

uncertainties and delays as to deny substantial relief, would

involve multiplicity of suits, cause further irreparable

injury and occasion damage, vexation and inconvenience,

not only to the plaintiffs and those similarly situated, but to

defendants as governmental agencies.

Complaint Filed against State Board of Education, State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Board of

Education of the Laurel Special School District

RA-5

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that:

(a) The Court advance this cause on the docket and

order a speedy hearing of the application for interlocutory

injunction and the application for permanent injunction

according to law, and that upon such hearings:

(b) The Court enter interlocutory and permanent judg

ments declaring that any administrative orders, regulations

and rules, customs, practices and usages pursuant to which

plaintiffs are segregated with respect to their schooling

because of race, color or ancestry violate the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution.

(e) The Court issue interlocutory and permanent

injunctions ordering defendants to admit infant plaintiffs

and all others similarly situated to the public schools in

the Laurel Special School District on a racially nondis-

criminatory basis with all deliberate speed.

(d) The Court allow plaintiffs their costs and such

other relief as may appear to the Court to be just.

L o t u s L. R e d d i n g

Attorney for Plaintiffs

923 Market Street,

Wilmington 7, Delaware.

Complaint Filed against State Board of Education, Slate

Superintendent of Public Instruction, and the Board of

Education of the Laurel Special School District

Answer of State Board of Education and State Super

intendent of Public Instruction, Printed as Model of

Answer of These Defendants in All Seven Actions.

1. As to allegations of fact, defendants are without

knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief as to

the truth of these averments.

RA-6

Answer of State Board of Education and State

Superintendent of Public Instruction

2. As to allegations of fact, defendants are without

knowledge or information sufficient to form a belief as to

the truth of these averments.

3. It is admitted that the plaintiffs have not been

accepted in the public school under the jurisdiction of Laurel

Special School District. It is admitted that said Laurel

Special School District has not heretofore taken as stu

dents persons of Negro blood and ancestry. Except as

herein admitted, defendants are without knowledge or

information sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of the

remaining averments of fact set forth.

4. (a) It is admitted that the defendants Madeline

Buchanan, Clayton A. Bunting, Byard V. Carmean, Irvin

S. Taylor, Vincent A. Theisen and Marvel 0. Watson, are

members of the State Board of Education, an adminis

trative agency of the State of Delaware. The duties of

said State Board of Education are those set forth in Title

14, Delaware Code 1953, as amended.

(b) Admitted.

(c) Admitted except that the status and duties of the

Board of Education of the Laurel Special School District

are determined by Title 14, Delaware Code 1953, as

amended.

5. These defendants are without knowledge or informa

tion sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of these

averments.

6. Admitted that the quotations set forth in Paragraph

6 of the Complaint are from a letter of the Laurel Special

School District to State Superintendent dated August 9,

1955. Reference is made to said letter for the statements

RA-7

Answer of State Board of Education and State

Superintendent of Public Instruction

of the said Laurel Special School District contained therein.

Except as so admitted, these defendants are without knowl

edge or information sufficient to form a belief as to the

truth of other averments in this paragraph.

7. Admitted that by letter of February 10, 1956, the

attorney for plaintiffs advised that “ parents of negro

school children living in Laurel, Delaware, by petition for

warded to the Board of Education of the Laurel Special

School District under date of August 10, 1955, requested

that Board to take immediate steps to reorganize the public

school of Laurel Special School District on a racially non-

discriminatory basis.” Admitted that the State Board of

Education was requested to “ immediately desegregate the

public schools of the Laurel Special School District * *

8. Admits that by letter of March 16, 1956, the State

Board of Education stated that for reasons set out in said

letter it could not comply with the request to immediately

desegregate the said public school. The State Board’s

policy, referred to in said letter of March 16, 1956, calling

for joint action initiated by the local Board of Education was

considered and approved by the Supreme Court of the State

of Delaware in the case of Steiner et al. v. Simmons et al.,

111 A. 2d 574, decided February 8, 1955, to which opinion

reference is hereby made.

9. The averments in this paragraph are conclusions of

law which are before this Court for determination.

W h e r e f o r e , these defendants pray that the Court dis

miss said complaint or enter such order as shall appear to

be proper and just.

J o s e p h D o n a l d C r a v e n ,

Attorney General.

H e r b e r t L. C o b i n ,

Chief Deputy Attorney General.

RA-8

Answer of Board of Education of Laurel Special School

District, Printed as Model of Answers Filed by

Local School Boards in AH Seven Actions.

Defendant members of the Board of Education of the

Laurel Special School District answer plaintiffs’ complaint

as follows:

F i r s t D e f e n s e

1. (a) If any facts are alleged in paragraph “ 1(a)” ,

these defendants deny knowledge of the same and demand

strict proof thereof.

(b) Same as the answer to “ a ” .

(c) Denied that any pertinent administrative orders

or regulations have ever been made or promulgated by

these defendants. In so far as “ customs, practices, and

usages” are concerned, it is admitted that the customs

practices and usages have heretofore been for white pupils

only to apply for admission to white schools, and for

colored pupils only to apply for admission to colored

schools, but it is denied that any colored pupil has applied

for admission to any white school under the jurisdiction

of these defendants since the Supreme Court handed down

its second decision in Brown v. The Board of Education

of Topeka.

2. Same as the answer to “ 1(a)” .

3. Admitted.

4. (a) Admitted.

(b) Admitted.

(c) Admitted.

RA-9

5. Admitted with respect to all adult plaintiffs, with

the exception of Christa Cottman, who did not sign the

petition.

6. It is admitted that the statement quoted in para

graph “ 6” was made by the Superintendent of Schools of

the Laurel Special School District with approval of the

members of the Laurel Board. The bare quoted statement

fails to point out the fact that the Laurel Board had ap

pointed a study committee to consider this problem and

they hereby drew out more clearly some of the problems

in bringing about public acceptance of integration.

(a) The opposition to school integration in the Laurel

Community is so widespread and of such an emotional

character that any action apparently initiated by the local

board looking toward integration, and not clearly forced

upon the local board by some agency higher in authority

than these defendants, would be either ignored completely

or overridden by force.

(b) Neither the local board nor the local police authori

ties possess any such facilities for the maintenance of law

and order as would be required to enforce the first small

step toward integration in the Laurel Schools so long as

there are numerous other schools in the vicinity of Laurel

in which integration is not being likewise enforced.

(c) All the communities in Delaware, south of Dover,

despite individual differences and special problems, are

essentially similar sociologically, so as to constitute what

amounts to a single community. Enforcement of integra

tion in the Laurel Schools, without substantially simul

taneous enforcement throughout this same community, and

without any systematic plan affecting this entire larger

Answer of Board of Education of Laurel Special

School District

BA-10

community, would be calculated to inflame resentment and

to increase the likelihood of violence, and this is equally

true even if the Court should take exactly the same steps

in all the other communities in which the school authorities

were sued at the same time this action was brought. What

ever reasons may have prompted the filing of this particu

lar group of suits, those reasons are not related to the

problem of enforcement, and it would be difficult, if not

impossible, for these defendants to explain to the public

why Laurel would be treated differently from other neigh

boring communities. Enforcement, therefore, in Laurel,

or in all of the several other school districts in which the

school authorities were sued at the same time as Laurel,

would not further the “ elimination of such obstacles in a

systematic and effective manner” , as those words were

used in the second decision of Brown vs. Topeka. If there

is to be an “ effective and systematic approach, it must be

general and schematic, applying not merely to Laurel, but

throughout the adjoining communities as well.

(d) Nothing stated in this answer necessarily reflects

the feelings or preferences of any of the individual mem

bers of the Laurel Board. It represents an effort to lay

before the court what these defendants believe to be perti

nent facts.

7. These defendants have no knowledge of the truth

of the allegations of paragraph “ 7” and, if the same are

material, will hold the plaintiff to strict proof thereof.

8. Same as the answer to “ 7” .

9. Denied that injunction against these defendants is

an appropriate or available remedy. Further, defendants

believe and aver that, owing to the intensity of public

Answer of Board of Education of Laurel Special

School District

RA-11

feeling, irreparable injury to the plaintiffs and to those

whom the plaintiffs represent could result from having

plaintiffs’ prayers for relief granted too soon and too

completely. As to the remaining allegations of said para

graph “ 9” the defendants disclaim such knowledge as

would enable them to admit or deny the same, and if they

prove material, will hold plaintiffs to strict proof thereof.

S econd D efense

10. These defendants here re-allege by reference the

same answers to the complaint as were spelled out in the

first defense.

11. And as an additional defense, these defendants say

that the school building under the jurisdiction of the Laurel

Special School District—and heretofore used for white

pupils only—is presently overcrowded and inadequate, and

is growing increasingly so. The present General Assembly

has included Laurel in its appropriation for the school

building program which is currently being delayed by a

dispute over architects’ fees. For this reason admitting

colored children to the white school at this time would

merely further overtax already overtaxed facilities, pro

mote confusion, increase discomfort and make the educa

tion of pupils of all races more difficult.

W herefore, these defendants respectfully pray that the

Court will hear the cause and dismiss this action as to them,

with costs.

James M . T un nell , J r.

James M. Tunnell, Jr.,

Georgetown, Delaware

Attorney for Defendants.

Answer of Board of Education of Laurel Special

School District

RA-12

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy on April 5, 1957

* [1] Mr. Cobin: * * * The State Board has already ad

dressed to the local boards a directive which has the force

of law, which has not been complied with.

The Court: Well, what has the Attorney General been

doing about it? If their directive, according to the Su

preme Court of Delaware, has the force of law, why don’t

you enforce it?

Mr. Cobin: Well, your Honor, the Attorney General

has taken the same position as has been carried on in all

the other states, of waiting until a problem has arisen in

each local district. Some districts have voluntarily gotten

up plans of desegregation, for example, Wilmington, Dela

ware City, Christiana—

The Court: How about the local districts that have not ?

Mr. Cobin: Well, we have eight of those—or seven of

those districts now before your Honor.

The Court: Why do you make Mr. Redding carry the

ball! If the regulations and the directive have the force

of law, why doesn’t the Attorney General of Delaware en

force them? Why make these private citizens come into

a Federal Court to have their rights protected?

Mr. Cobin: Well, your Honor, we do not know pre

cisely in how many areas or who in any particular area

desire [2] to attend a heretofore white school. It is felt

desirable to leave that to the application of children—

The Court: Well, your State agency has seen fit to

issue directives. Now, why shouldn’t there be some intel

ligent report made as to whether those directives have been

carried out, and if they have not been carried out, why is it

not the duty of the Attorney General?

* Herbert L. Cobin, Chief Deputy Attorney General of the State

of Delaware.

RA-13

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy, on April 5, 1957

Mr. Cobin: The Attorney General would then have to

file approximately 90 or more suits.

The Court: Well, what difference does that make? He

is a public servant. Why make Mr. Redding’s clients carry

the ball?

Mr. Cobin: Well, we are taking the position, as has

been taken, that we will leave this matter to the plaintiffs

who desire to enter a school, and if they are refused, that

we will then support the State Board in that litigation.

The Court: Well, what about these plaintiffs here in

these cases? Why haven’t you protected them?

Mr. Cobin: Well, we are in the process of doing that

now, your Honor.

The Court: Where?

Mr. Cobin: In this court.

The Court: You haven’t filed any pleadings in this

court.

[3] Mr. Cobin: No, no, but we are—

The Court: The Attorney General doesn’t enforce the

law in this court.

Mr. Cobin: He can.

The Court: Well, I have a query.

Mr. Cobin: This court has jurisdiction.

The Court: No question about that. But if the State

Board and the Supreme Court of Delaware has said that

their directives and regulations have the force of law, why

do you sit back and see that it is not enforced?

Mr. Cobin: Because we feel that it is desirable, instead

of having a mass number of suits, with the hope that these

other boards will eventually voluntarily, as a few of these

cases are decided, the rest of the boards will voluntarily

submit plans and comply with the law. I think, your Honor,

that that eventually will be the way the thing will work out.

The Court: I have no further questions.

* #

RA-14

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy on July 9, 1957, on Motions for Consolidation

and for Summary Judgment against the Stale Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction

(Later, in the course of Mr. Redding’s reply, the fol

lowing occurred:)

Mr. Redding: * * * The State Board is a defendant

here, in each one of these cases, and while I must say that

[4] Mr. Cobin has in my opinion come through in some sort

of fashion this morning, I think that a reading of the

answers filed by the State Board in each of these cases

and by the local boards will show that there is buck-passing.

The State Board says it is the duty of the local boards, and

the local boards have said that the devising of a plan of

desegregation is the duty of the State Board.

The Court: And the last buck to be passed is to this

Court.

Mr. Redding: That is correct, sir.

# *

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy on July 9, 1957, on Motions for Consolidation

and for Summary Judgment against the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction

[1] The Court: Who is next!

Mr. Craven :* I might say by way of introduction, your

Honor, that the position of the State Board is consistent

with what it has been heretofore and that the change in

position is that of Mr. Redding in the matter. He first

obtained a summary judgment against the Clayton School

Board and as far as I know and the record indicates noth

ing further has been done with that summary judgment.

* Joseph Donald Craven, Attorney General of the State of Dela

ware.

RA-15

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy on July 9, 1957, on Motions for Consolidation

and for Summary Judgment against the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction

I can see that it would be a matter of greater conveni

ence to the plaintiffs in this case if the whole burden were

to be placed on the State Board of Education to come up

with some plan that was worked out which the State Board

would take the responsibility for and in saying that this

would be the answer to the whole problem.

The Court: Mr. Craven, may I ask an informational

question? On April 1, 1957, in the Clayton School District

No. 119 case, which is our Civil Action 1816, the State

Board was ordered within 60 days from that date to file

with this Court a plan of integration. Did you take an

appeal from that order to the Court of Appeals?

Mr. Craven: You mean the Clayton Board was ordered?

The Court: No, you were ordered. Members of the

[2] State Board. I will quote from the order. (The Court

read the order referred to.) Did you take an appeal from

that order?

Mr. Craven: No, there was a stay, your Honor. Your

Honor issued a stay in that case based on the appeal that

was taken by the Clayton Board.

The Court: Now, my next question is this: I am

familiar with the facts in this case. The Clayton Board

did not perfect its appeal. In fact, this Court had all the

records returned from the Court of Appeals. Have you

done anything subsequently to that?

Mr. Craven: No. The State Board has done nothing,

and I assume the State Board assumed, as I did, as we did

in the office, that any further action would be taken by Mr.

Redding, the plaintiff.

The Court: It appears to be a cat and mouse game.

BA-16

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy on July 9, 1957, on Motions for Consolidation

and for Summary Judgment against the State Board,

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction

Mr. Craven: The plaintiffs obtained the summary

judgment, your Honor, and the order provided that the

local board was to submit, as your Honor recalls -

The Court: The Court granted you the courtesy of a

stay, and then when you were apprised of the fact that the

appeal was aborted nothing was clone toward making a

plan under the order of April 1, 1957.

Mr. Craven: Nothing was done, your Honor.

The Court: Very well, I have no further questions.

You may proceed with your argument.

[3] Mr. Craven: Well, the position of the State Board

is merely being reiterated here this morning that the local

board in the Clayton case was requested—in fact, was

directed—I have it before me—“ such plan by the local

board shall be submitted to the State Board within a period

of thirty days and within sixty days the State Board of

Education shall submit its plan to the Court for further

instruction.” In other words, the Court took the position

at that time that it was the primary responsibility of the

local board to submit its plan to the State Board and the

State Board feels that that was correct in that instance

and that should be followed.

The Court: That was in that particular case.

Mr. Craven: In that particular case. That having-

set a precedent—

The Court: I do not accept this statement, that it was

a precedent.

Mr. Craven: Your Honor will recall that I am here

representing the State Board, and the State Board has

instructed me as to what its position is in the matter as

far as that is concerned. There isn’t any question but

what the Court can issue its directive either to the local

RA-17

Excerpt from Argument Before Chief District Judge

Leahy on July 9, 1957, on Motions for Consolidation

and for Summary Judgment against the State Board

of Education and the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction

boards or to the State Board as such, but the State Board

does feel that it is up to the local boards to submit a plan

first to them and that they are prepared to confer with the

Court and with the local boards to assist in every way

possible.

[4] I suppose that is no different from what our original

brief was in the Clayton case, except in that case we sug

gested the—the State Board suggested that the plan be

submitted by the local boards directly to the Court, which

of course this Court did not accept, and the State Board

has declared it is willing to cooperate in every possible way

with the local boards, but still feels that the initiative

should come from the local boards.

The Court: Suppose they do not propose a plan in

terms of this side of eternity, how long will the State

Board remain inactive?

Mr. Craven: I suppose until this Court issues an order

and a directive.

The Court: Very well, I have your point.

BA-18

Excerpt from Mandate of Court of Appeals, 3rd C.,

Issued June 30, 1958, and Subsequently Reissued.

A nd W hereas, the said cause came on to be heard

before the said United States Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit, on the said record, and was argued by

counsel;

O n Consideration W hereof, it is now here ordered

and adjudged by this Court that those portions of the

decree of the District Court in this case, which states dates

for the submission of the plan by the State Board of

Education to the District Court and to each member of

all the school boards in all of the public school districts

which heretofore have not admitted pupils under a racially

non-discriminatory plan, be and the same are hereby

vacated, so that the District Court will be free to take

appropriate action; and that in all other respects the de

cree of the said District Court in this case be, and the

same is hereby affirmed.

You, T herefore, A re H ereby Commanded that such

proceedings be had in said causes, in conformity with the

opinion and judgment of this court, as according to right

and justice, and the laws of the United States, ought to be

had, the said appeals notwithstanding.

Signed and sealed this 30th day of June in the year

of our Lord one thousand nine hundred and fifty eight.

I da 0 . Creskoff

Clerk, United States Court

of Appeals for the Third Circuit

RA-19

B y B iggs, Chief Judge.

The mandate of this court which was handed down on

June 30, 1958 will be recalled, subject to the proviso that if

the appellants have not filed a petition for -writs of certiorari

to the Supreme Court of the United States on or before

August 14, 1958, and have not filed with the Clerk of this

court a certificate to such effect by August 18, 1958, the

mandate of this court shall issue forthwith to the court

below to carry out and effect the judgments of this court.

We take this step so that the appellants, by application

to the Supreme Court for writs of certiorari, may exhaust

their legal remedies without the possible complication of

the cases becoming moot by action of the court belowT effect

ing our judgments.

I am authorized to state that Judge Kalodner dissents

and is of the view that in the light of all the circumstances,

including the delay of the appellants in making application

to this court in respect to the mandate, that the mandate

should not be recalled.

A true Copy:

I da 0 . Creskoi’f

Teste:

Opinion of Court of Appeals, 3rd C. re Recall of

Mandate, Filed July 23, 1958.

Clerk of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Third Circuit.

BA-20

Pursuant to the decree of this Court entered July 15,

1957, and the mandate of the Court of Appeals for the

Third Circuit vacating those portions of said decree which

state dates for the submission of the plan of desegregation

by the State Board of Education to this Court and to each

member of all the school boards in all the public school

districts which heretofore have not admitted pupils under

a racially non-discriminatory plan, and affirming the decree

in all other respects,

I t is Ordered t h a t :

1. The minor plaintiffs in the respective cases and all

other Negro children similarly situated are entitled to

admittance, enrollment and education, on a racially non-

discriminatory basis, in the public schools of Clayton School

District No. 119, Milford Special School District, Green

wood School District No. 91, Milton School District No. 8,

Laurel Special School District, Seaford Special School Dis

trict and John M. Clayton School District No. 97.

2. The defendants are permanently enjoined and re

strained from refusing admission, on account of race, color,

or ancestry of respective minor Negro plaintiffs and all

other children similarly situated, to the public schools

maintained in the respective above-mentioned school dis

tricts.

3. Defendant members of the State Board of Education

and defendant George B. Miller, Jr., State Superintendent

of Public Instruction, shall submit to this Court within

one hundred five days from the date of this order a plan

of desegregation providing for the admittance, enrollment

and education on a racially nondiscriminatory basis, for

the Fall Term of 1959, of pupils in all public school districts

Order of Judge Layton of November 19, 1958

R A -2 1

of the State of Delaware which heretofore have not ad

mitted pupils under a plan of desegregation approved by

the State Board of Education.

4. The members of the State Board of Education, as

promptly as possible and within fifty days from the date

of this order:

(a) Shall inform each school board of a public school

district which heretofore has not admitted pupils under

a plan of desegregation approved by the State Board of

Education that a plan of desegregation affecting such public

school district is to be prepared by the State Board of

Education and is to be submitted to this Court by the

State Board of Education;

(b) Shall make arrangements for consultation and carry

out such consultation with each district school board named

in this action relative to the plan of desegregation to be