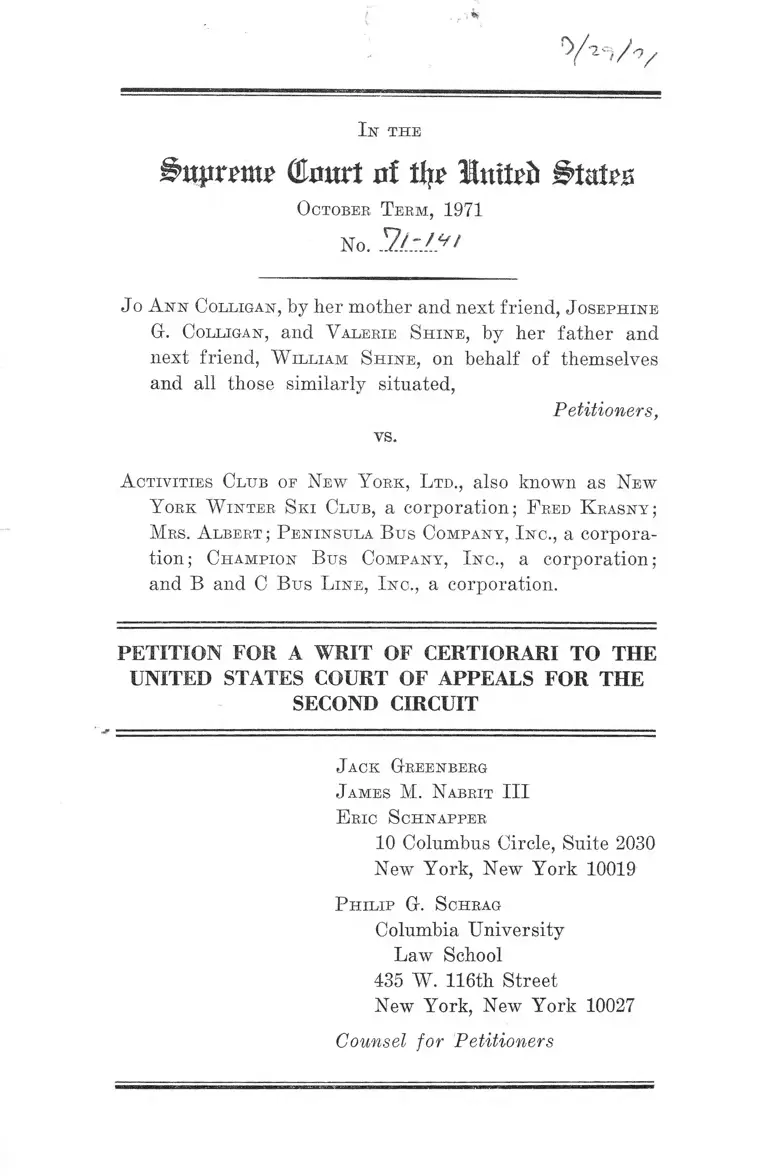

Colligan v. Activities Club of New York Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit

Public Court Documents

July 29, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Colligan v. Activities Club of New York Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, 1971. 7c1e29ed-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/13c5bec5-2362-4634-81ae-faa3906c0b6a/colligan-v-activities-club-of-new-york-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-second-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

V W - y

«

I n the

(&mxt iif ilrx lutfrfc States

Octobeb Teem, 1971

No..!hrjyi

Jo A nn Colligan, by her mother and next friend, Josephine

G. Colligan, and V alebie Shine, by her father and

next friend, W illiam Shine, on behalf of themselves

and all those similarly situated,

Petitioners,

vs.

A ctivities Club of New Y ork, Ltd., also known as New

Y ork W inter Ski Club, a corporation; F red K rasny;

Mrs. A lbert ; Peninsula Bus Company, I nc., a corpora

tion; Champion Bus Company, I nc., a corporation;

and B and C Bus L ine, Inc., a corporation.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SECOND CIRCUIT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit III

E ric S chnapper

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Philip G. S chrag

Columbia University

Law School

435 W. 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Counsel for Petitioners

I N D E X

Opinions Below .................................... ................... . 1

Jurisdiction ............................... ........... ............ ............ . 2

Questions Presented ............................................ ........... 2

Statutory Provision Involved ......................................... 3

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ .................... ............. 5

Conclusion ......................................... 16

Appendix ........................................................................... la

Opinion of the Court of Appeals ............................ la

Judgment of the Court of Appeals.......................... 17a

Opinion of the District Court ................................. 18a

Table op A uthorities

Cases:

American Medical Association v. United States, 317

U.S. 519 (1943) ............... 11

American Stevedores v. Porello, 330 U.S. 446 (1947)..11,12

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159 (1970)..........................2,10

Barr v. United States, 324 U.S. 83 (1945)...................... 12

Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 (1959)....... 7

Chicago, etc. R. Co. v. Acme Fast Freight, 336 U.S.

465 (1949)

PAGE

12

11

In re Camden Shipbuilding Co., 227 F. Supp. 751 (D.

Me., 1964) ....................................................................... 13

Data Processing Service v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970)

2,10

PAGE

General Atlas Carbon Co. v. Sheppard, 37 F. Supp. 51

(W.D. Tex. 1940) ............................................................ 13

Hall v. Coburn Corporation of America, 26 NY2d 281

(1970) ............................................................................. 15

International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 310

(1945) ................................................................................ 6

Masszonia v. Washington, 315 F. Supp. 529 (D.D.C.,

1970) .......................................... 14

Nigro v. United States, 276 U.S. 332 (1928).................. 11

Office of Communication of Church of Christ v. F.C.C.,

359 F.2d 994 (D.C. Cir., 1966) ........................................ 9

Price v. Forrest, 173 U.S. 410 (1899) ............................. 13

Robinson v. Difford, 92 F. Supp. 145 (E.D. Pa., 1950) 13

Samson Crane Co. v. Union Nat. Sales, 87 F. Supp.

218 (D. Mass., 1949) ..................................................... 6

Telephone Users Assn., Inc, v. Public Service Commis

sion of D.C., 271 F. Supp. 393 (D.D.C., 1967)........... 14

Tenants Council, etc. v. DeFranceaux, 305 F. Supp. 560

(D.D.C., 1969) 14

Ill

PAGE

United States v. Bowen, 100 U.S. 508 (1879).............. . 11

United States v. Oregon, 366 U.S. 643 (1961)................ 11

Vogel v. Tenneco Oil Co., 276 F. Supp. 1008 (D.D.C.,

1967) ................ ........................ - ................................... 14

Woods v. Bauhan, 84 F. Snpp. 243 (D.N.J., 1949)....... 13

Yazoo and Mississippi Valley R. Co. v. Thomas, 132

U.S. 174 (1889) ............. ................................................ 13

Young v. Ridley, 309 F. Supp. 1308 (D.D.C., 1970)....... 14

Statutes:

15 U.S.C. §1121 ............................................................... 3, 5

15 U.S.C. §1125 (a) ......................................................passim

15 U.S.C. §1127 ............................................................. 10,13

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ......................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1963 ............................................................... 7

46 Stat. 2907 ..................................................................... 10

Congressional Hearings:

Joint Hearings Before the Committee on Patents, 68th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1925) ............................ ..................... 10

Hearings Before the House Committee on Patents, 69th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1926) ................................................ 10

Hearings Before the Senate Committee on Patents,

69th Cong., 2d Sess. (1927) ......................................... 10

Hearings Before the Senate Committee on Patents,

78th Cong., 2d Sess. (1944) .................. ...................... 10

IV

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Improvements

in Judicial Machinery of the Senate Judiciary Com

mittee, 91st Cong., 1st Sess. (1969) ............................ 14

Hearings Before the Consumer Subcommittee of the

Senate Commerce Committee on S. 2246, 91st Cong.,

2d Sess. (1969) .............................................................. 6, 8

Gongressionall Reports:

House Rep. 944 (1939) 76th Cong., 1st Sess.................... 10

Senate Rep. 1562 (1940), 76th Cong., 3d Sess.............. 10

Senate Rep. 568 (1941) 77th Cong., 1st Sess.............. 10

House Rep. 2283 (1942) 77th Cong., 2d Sess.............. 10

House Rep. 603 (1943), 78th Cong., 1st Sess.............. 10

Senate Rep. 1303 (1944) 78th Cong., 2d Sess.............. 10

House Rep. 219 (1945) 79th Cong., 1st Sess.......... 10

Senate Rep. 1333 (1946) 79th Cong., 2d Sess.............. 10

Senate Rep. 91-1124 (1970) 91st Cong., 1st Sess............. 9

Periodicals:

Crimes, “Control of Advertising in the United States

and Germany: Volkswagen Has a Better Idea,” 84

Harv. L. Rev. 1769 (1971) ........................................... 15

Starrs, “The Consumer Class Action—Part I : Consid

erations of Equity,” 49 Boston U. L.Rev. 211 (1969) 15

“Developments in the Law Competitive-Torts,” 77

Harv. L. Rev. 888 (1964) ........................................... 9

Comment, 114 U. Pa. L. Rev. 395 (1966)........................ 8

PAGE

V

PAGE

Miscellaneous:

President Nixon’s Message on the Protection of Inter

ests of Consumers, 91st Cong. 1st Sess. (1969)...... 14

92 Cong. Rec. 7522 (79th Cong. 2d Sess., 1946).............. 10

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders, 274-78 (1968) .............................................. 8

Moore Federal Practice .................................................. 8

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ................................. 14

I n t h e

drntrt of % United States

October T erm, 1971

No.............

Jo A nn Colligan, by her mother and next friend, Josephine

G. Colligan, and V alerie Shine, by her father and

next friend, W illiam Shine , on behalf of themselves

and all those similarly situated,

Petitioners,

vs.

A ctivities Club of New Y ork, L td., also known as New

Y ork W inter Ski Club, a corporation; F red K basny;

Mrs. A lbert ; Peninsula Bus Company, I nc ., a corpora

tion; Champion B us Company, I nc., a corporation;

and B and C Bus L ine, I nc., a corporation.

PETITION FOE A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SECOND CIRCUIT

The petitioners Jo Ann Colligan, by her mother and

next friend, Josephine G. Colligan, and Valerie Shine,

by her father and next friend, William Shine, respectfully

pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit entered in this proceeding on May 6, 1971.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, not yet reported,

appears in the Appendix hereto, p. la. The opinion of the

2

District Court for the Southern District of New York which

is not reported, appears in the Appendix hereto, p. 18a,

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit was entered on May 6, 1971 and appears in the

Appendix hereto, p. 17a. This Court’s jurisdiction is in

voked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

1. Whether section 43(a) of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C.

§1125(a), which explicitly authorizes actions for damages

and injunctive relief by “any person” damaged by false

representations regarding goods and services in commerce,

confers upon consumers injured by such false representa

tions a right to sue for actual damages and for injunctive

relief to prevent such false representations.

2. Whether consumers are within the zone which Con

gress sought to protect when it enacted section 43(a) of

the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. §1125(a), prohibiting false

representations regarding goods and services in commerce,

and therefore have standing to seek injunctive relief to

prevent such forbidden false representations even without

an express grant of standing, under the principles of Data

Processing Service v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970) and Bar-

low v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159 (1970).

3

Statutory Provisions Involved

United States Code, Title 15, §1125(a), 60 Stat. 441, c.

540 (1946) :

“Any person who shall affix, apply or annex, or use

in connection with any g*oods or services, or any con

tainer or containers for goods, a false designation

of origin, or any false description or representation,

including words or other symbols tending falsely to

describe or represent the same, and shall cause such

goods or services to enter commerce, and any person

who shall with knowledge of the falsity of such desig

nation of origin or description or representation cause

or procure the same to be transported or used in com

merce or deliver the same to any carrier to be trans

ported or used shall be liable to a civil action by any

person doing business in the locality falsely indicated

as that of origin or in the region in which said locality

is situated, or by any person who believes that he is

or is likely to be damaged by use of any such false

description or representation.”

United States Code, Title 15, §1121, 60 Stat. 440, c. 541

(1946):

The district and territorial courts of the United

States shall have original jurisdiction and the courts

of appeal of the United States shall have appellate

jurisdiction, of all actions arising under this chapter,

without regard to the amount in controversy or to

diversity or lack of diversity of citizenship of the

parties.

4

Statement of the Case

Petitioners, two parochial school children, by their par

ents and next friends, brought the instant action in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

New York alleging the following facts.

Petitioners and 151 of their classmates at the Sacred

Heart Academy of Hempstead, New York, contracted with

defendant, Activities Club of New York, Ltd. (the Club)

for a ski tour to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, to be

conducted during the weekend of January 24, 1970, for

which each of the students paid $44.75 in advance. The

tour was purchased in reliance on the Club’s representa

tions that each child would be provided with adequate ski

equipment and qualified instruction, that safe and reliable

transportation certified by the Interstate Commerce Com

mission would be provided between New York and Great

Barrington, and that all meal costs would be included in

the prepaid tour price. The Club further represented to

petitioners and the other children that it was a member

ship club rather than an ordinary commercial tour operator

and suggested, by means of flyers closely resembling those

of a major interstate firm known as National Ski Tours,

that the Club was affiliated with National. Some of these

representations were written, some were oral, and others

were disseminated by means of the United States mail.

Each of these representations was alleged to have been

false. Only 88 pairs of boots and skis were provided for

the 153 children. Only one qualified instructor was pro

vided, and he spent a substantial portion of his time fitting

the children with such skis and boots as were available.

Of the buses used to transport the children, one poured

exhaust fumes into its interior, another had faulty brakes

5

and only one headlight, a third broke down completely

stranding 40 children and two nuns on a country road in

the middle of the night. Neither the buses nor the Club

was licensed or certified by the Interstate Commerce Com

mission. One busload of children was forced to pay for

an extra meal because of the unsafe bus transportation,

the cost of which defendants refused to refund. The Club

was not a club at all, but a purely commercial venture,

and was in no way connected to National Sid Tours whose

literature it had simulated.

Petitioners brought this class action, on behalf of them

selves, their classmates, and all others similarly situated,

under section 43(a) of the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. §1125

(a)). Jurisdiction was based on section 39 of the Act, 15

U.S.C. §1121. Petitioners sought damages on behalf of

themselves and the other injured children as well as an

injunction forbidding defendants from continuing to make

the alleged misrepresentations.

The District Court dismissed the complaint on its own

motion, concluding that it lacked jurisdiction for the sole

reason that section 43(a) authorized actions by commercial

parties but not by consumers. The Court of Appeals af

firmed on the same ground. The Court of Appeals ac

knowledged that the instant case fell within the literal

language of section 43(a), and that the question was one

of first impression, but reasoned that the sole purpose of

the section was to protect businessmen and that only

businessmen could therefore bring an action thereunder.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

This case presents an important and recurring question

regarding the jurisdiction of federal courts over inter

state consumer fraud which has not been, and should be,

6

resolved by this Court. Without the exercise of federal

jurisdiction under section 43(a), consumers will be power

less to prevent or remedy false advertising, false labeling

or other misrepresentations in interstate commerce. The

Court of Appeals, in denying jurisdiction, rejected basic

maxims of statutory construction set out in the applicable

decisions of this Court.

Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act authorizes private ac

tions for damages and injunctive relief by any person

injured by false representations in connection with goods

or services in commerce. While the Act defines “ commerce”

as “all commerce which may lawfully be regulated by

Congress,” this definition is not all inclusive. “Business

essentially local in nature is still outside the scope of its

terms in the absence of some relationship to interstate

commerce sufficient to bring it within the limits of Congres

sional power.” Samson Crane Co. v. Union Nat. Sales, 87

F. Supp. 218, 221 (D. Mass., 1949). The need for federal

jurisdiction over interstate commerce, recognized by Con

gress in the passage of this law, is substantial. In a time

of rapid transportation and nationwide advertising cam

paigns, the ability of states to protect their citizens from

consumer fraud is seriously limited. Footloose vendors of

worthless merchandise can and do elude the jurisdiction of

state law when their practices are uncovered merely by

crossing “ the State line.” Hearings Before the Consumer

Subcommittee of the Senate Commerce Committee on S.

2246, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1969) 30, 43 (Remarks of Mrs.

Knauer, Senator Tydings). Thus the instant defendants,

if an injunction were obtained against their activities in

New York, could merely cross the Hudson and resume

their misrepresentations the next day in New Jersey. The

due process clause, as expounded in International Shoe Co.

v. Washington, 326 TJ.S. 310 (1945), and its progeny, lim

7

its the long arm jurisdiction of the states over persons

and corporations which do business within their boundaries

to transactions actually occurring within the state. Thus

in most cases fifty separate state lawsuits would be re

quired to enjoin a nationwide advertising campaign or to

obtain damages for a consumer fraud of national scope.

Even when in personam jurisdiction existed over the mer

chant, relief of a more than local nature could be obtained

only if injured consumers from each of the many states

concerned, with standing to seek enforcement of their own

state law under applicable conflict of law principles, could

be brought together to join in a civil action. Problems of

barratry aside, it would as a practical matter be virtually

impossible to organize such plaintiffs representing as many

as fifty different jurisdictions and, so far as is known, such

a x>roject has never been attempted or succeeded in any

state court. If the accuracy of representations must be

adjudicated in a multiplicity of lawsuits applying different

legal tests in a variety of states, a crazy-quilt pattern will

emerge, forbidding a label or advertisement in some states,

permitting it in others, and generating uncertainty in the

rest.

The exercise of federal jurisdiction affords the only solu

tion to these problems. The federal courts alone are

authorized to issue nationwide injunctions. Unlike state

courts, the District Courts can entertain as part of a class

action claims arising among parties and regarding trans

actions entirely outside their districts. Efficient national

enforcement of federally awarded damages can be ob

tained by merely registering the original judgment in any

federal court. 28 U.S.C. §1963. Resolution in the federal

courts of issues as to the accuracy of labels and representa

tions will assure the national uniformity of decisions in

the commercial area essential to the free flow of commerce

among the states. Compare Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines,

8

359 U.S. 520 (1959); 1 Moore Federal Practice §0.71 [3.-1],

p. 701.

The prevention and remedying of false advertising and

labeling is of paramount national importance:

[C]onsumer fraud is an insidious economic cancer

which eats at the very vitals of our society. The fact

that it continues to the extent that it does erodes the

respect of the individual, especially the poor, for law

enforcement. It rots their faith in the equal applica

tion of the law to the white-collar fraud robber and

to the family who cannot pay for shoddy merchandise

they were tricked into buying by that self-same op

erator. It withers our moral fiber. It misdirects our

economic resources. It saps the strength of our free

enterprise system. (Hearings before the Consumer

Subcommittee of the Senate Commerce Committee on

S. 2246, 91st Cong., 1st Sess., 15 (1969) (Remarks of

Mrs. Knauer, President Nixon’s Special Assistant For

Consumer Affairs).

Such consumer frauds involve billions of dollars worth of

goods and services every year, Comment, 114 U. Pa. L.

Rev. 395 (1966), and exploitation of poor consumers has

been one of the principal causes of the urban riots of the

last decade. Report of the National Advisory Commission

on Civil Disorders, 274-78 (1968). Even if the federal

agencies with responsibilities in this area overcome the

failures of the past noted by the Court of Appeals (Appen

dix, p. 16a, n. 37), their resources will continue to be

grossly inadequate to oversee a trillion dollar economy.1

1 “ The FTC and the Justice Department— the staffs and budgets

of which will inevitably remain limited— must therefore choose

from among the hundreds of thousands of potential consumer ac

tions only those limited number of cases which their systems of

priorities identify as germane to [the elimination of unfair and

9

The Court of Appeals below did not question the need

for federal jurisdiction over interstate consumer frauds,

but held that jurisdiction should be limited to actions

brought by commercial parties. Experience with section

43(a) demonstrates that business initiated actions under

the section will not stop the use of interstate commerce

for the distribution of misrepresented goods and services.

Since its enactment in 1946 there have been fewer than two

reported decisions a year under section 43(a) in the entire

country. “Developments in the Law-—Competitive Torts”

77 Harv. L. Rev. 888, 908 (1964). Businessmen have pre

ferred to respond to a competitor’s misrepresentations by

a countering advertising campaign, or by joining in the

misrepresentation. The losses to competitors caused by

such consumer fraud, and the incentive to sue, is gener

ally far less than that suffered by the defrauded consumers.

At times there may be “a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ of defer

ence to a fellow [businessman] in the hope that he will

reciprocate on a propitious occasion.” Office of Communi

cation of Church of Christ v. F.C.C., 359 F.2d 994, 1004

(D.C. Cir., 1966). Not surprisingly none of the tour com

panies deprived of plaintiff’s business by the defendant’s

misrepresentations have initiated any legal proceedings.

This Court has repeatedly held that, even without an

express grant of standing, individuals have standing to

deceptive acts and practices]. For example, the FTC might find

that a particular case involving notorious fraud, but affecting only

several thousand residents of a smaller city should be rejected in

favor of an action against the national advertiser whose product

claims are on the borderline of deception and hence require the

Commission’s expert delineation. The necessity to allocate legal

resources will necessarily leave unsatisfied hundreds, if not thou

sands, of valid cases in which consumers have suffered significant

damages but which the government might choose not to prosecute.”

S. Rep. No. 91-1124, 91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970).

10

sue to enforce a federal law, at least by means of injunc

tion, if they are arguably within the zone of interest to

be protected by the statute. Association of Data Processing

Service Organisations, Inc. v. Camp, 397 U.S. 150 (1970);

Barlow v. Collins, 397 U.S. 159 (1970). That the protection

of the public from imposition by the use of false trade

descriptions was one of the foremost purposes of section

43(a) was reiterated in eig’ht Congressional committee

reports,2 in hearings before the patent committees of both

houses of Congress,3 and on the floor of the Congress which

passed the Act by Congressman Lanham himself.4 Primary

among the treaty obligations which the Lanham Act was

intended to satisfy was a duty to provide a cause of action

for “ any party injured” by the use of false or deceptive

descriptions of goods §45. 15 U.S.C. §1127; Inter-American

Convention for Trademark and Commercial Protection,

§§20 and 21, 46 Stat. 2907 (1931).

In reaching its conclusion that section 43(a) gives a

cause of action to commercial parties only, the Court of

Appeals repeatedly and at times expressly disregarded

2 See e.g. Senate Rep. 1333, 79th Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 1-3 (1946);

Senate Rep. 1303, 78th Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 3-4 (1944); Senate Rep.

568, 77th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 1-2 (1941); Senate Rep. 1562, 76th

Cong., 3rd Sess., p. 1 (1940); House Rep. 219, 79th Cong., 1st Sess.,

pp. 2-3 (1945); House Rep. 603, 78th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 2-3

(1943); House Rep. 2283, 77th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 19 (1942); House

Rep. 944, 76th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 2-3 (1939).

3 Hearings Before the Senate Committee on Patents, 78th Cong.,

2d Sess., pp. 25, 50, 73 (1944) (remarks by Daphne Robert of the

A.B.A., W. T. Kelley, Chief Counsel of the Federal Trade Commis

sion, and Congressman Lanham); Hearings Before the Senate Com

mittee on Patents, 69th Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 70-71 (1927) (Letter

from Edward Rogers); Hearings Before the House Committee on

Patents, 69th Cong., 1st Sess., pp. 49-59 (1926) (Remarks of Ed

ward Rogers); Joint Hearings Before the Committee on Patents,

68th Cong., 2d Sess., p. 5 (1925) (remarks of William L. Symons).

4 92 Cong. Rec. 7522 (79th Cong., 2d Sess., 1946).

1 1

basic maxims of statutory construction laid down in the

decisions of this Court.

Section 43(a) provides a cause of action for “any person”

who is or believes himself likely to be “damaged” by a

misrepresentation. This language literally includes the

instant plaintiffs. This Court has consistently refused to

read into the broad phrase “any person” or the general

term “ damage” any unstated restriction as to the type

of person or injury covered. American Stevedores v.

Porello, 330 U.S. 446 (1947) (“damage” ) ; American Medical

Association v. United States, 317 U.S. 519 (1943) (“any

person” ) ; Nigro v. United States, 276 U.S. 332 (1928)

(“any person” ). The Court of Appeals read in just such

an unstated limitation (Appendix, pp. 6a-7a, 16a-17a).

The language of the section, which if read literally would

authorize jurisdiction in this case, involves, as the Court

of Appeals conceded, neither vague words nor inconsistent

phrases (Appendix, p. 6a). For almost a century this

Court has insisted that resort shall not be had in the

construction of a statute to its legislative history when

its language is clear and unambiguous. United States v.

Bowen, 100 U.S. 508, 513 (1879), United States v. Oregon,

366 U.S. 643, 648 (1961). The Court of Appeals nonetheless

expressly resorted to such history to overturn the plain

meaning of the statute (Appendix, pp. 7a-10a).

Even if resort to the legislative history of the statute

were proper, the conclusions which the Court of Appeals

drew from that history were clearly erroneous. Both the

predecessor statute to section 43(a) and early drafts

thereof expressly limited civil actions to businessmen in

jured in their trade, but this limitation was dropped in

the final version of the bill. (See Appendix, pp. 9a-10a).

Under such circumstances this Court has held that the

inference to be drawn is that Congress intended to change

12

in this respect the restricted scope of the earlier statute

and drafts. American Stevedores v. Porello, 330 U.S. 446

(1947). The Court of Appeals not only declined to draw

such an inference, but reasoned to the contrary, that the

deletion of the restriction showed that Congress omitted

the restriction as surplusage and thus believed that the

same restriction was already implicit in the section (Ap

pendix, p. 10a).

During hearings before the House and Senate Patent

Committees an industry representative noted that the

proposed provision would authoi’ize suits by consumers

and suggested it be altered to exclude such actions; neither

Congressman Lanham nor the original drafter of the bill,

both present, disagreed with this construction, and the

suggestion was not adopted. This Court has held that,

where any inference can be drawn from the silence of

proponents in the face of a preferred construction, it is

that they concur in it. Chicago, etc. R. Co. v. Acme Fast-

Freight, 336 U.S. 465, 474-5 (1949). The Court of Appeals

held that in this case the silence of the bill’s proponents

showed they thought the construction so patently erroneous

as not to merit comment (Appendix, p. 9a).

Although the language of the statute literally covers the

instant case, the Court of Appeals urged that when the

Lanham Act was passed Congress did not foresee the con

sumer protection explosion or, by implication, the possi

bility that consumers might use the new law to protect

themselves (Appendix, pp. lla-12a). This Court has re

peatedly held that “ if Congress [has] made a choice of lan

guage which fairly brings a given situation within a stat

ute, it is unimportant that the particular application may

not have been contemplated by the legislatures.” Barr v.

United States, 324 U.S. 83, 90 (1945). The Court of Appeals

declined to follow this rule (Appendix, pp. 15a-16a).

13

This Court has repeatedly held that recitals of intent

enacted as part of a statute can only be used to interpret

statutory language which is ambiguous. Price v. Forrest,

173 U.S. 410 (1899); Yazoo v. Mississippi Valley R. Co. v.

Thomas, 132 U.S. 174 (1889).5 In the instant case section

45 of the Act, subject to the express caveat that it was

inapplicable if “the contrary is plainly apparent from the

context,” stated that the purposes of the Act were, inter

alia, to protect persons engaged in interstate commerce

from unfair competition, and, as noted above, to carry out

certain treaty obligations. 15 U.S.C. '§1127. The Court of

Appeals, disregarding the rule set out in Price and Yazoo,

the caveat to section 45, and the reference to treaty obli

gations which in fact included obligations to give consumers

rights of action, reasoned that the protection of business

men was the sole purpose of section 43(a) and refused to

permit the consuming public to sue under the section either

to protect themselves or under circumstances when such

suits might benefit the business community.

The Court of Appeals expressed understandable but

unwarranted concern as to the possible impact on the work

load of the federal courts of consumer actions under sec

tion 43(a). That section is limited to misrepresentations

of goods and services in commerce, and thus does not deal

with ordinary local business practices but concerns pri

marily regional or national sales and advertising which

the states lack adequate authority to effectively control.

5 For instances in which the lower federal courts refused to

depart from the clear meaning of an unambiguous provision in

order to give effect to a statement of purpose or policy enacted as

part of the statute at issue, see e.g. In re Camden Shipbuilding Co.,

227 F. Supp. 751, 752-3 (D. Me., 1964) ; Robinson v. Difford, 92

F. Supp., 145,148 (E.D. Pa., 1950); Woods v. Bauhan, 84 F. Supp.,

243, 244 (D.N.J. 1949); General Atlas Carbon Co. v. Sheppard, 37

F. Supp. 51, 54 (W.D. Tex., 1940).

14

Even where intrastate commerce is involved, individual

actions are unlikely:

The damage suffered by any one consumer would not

ordinarily be great enough to warrant costly, indi

vidual litigation. One would probably not go through

a lengthy court proceeding, for example, merely to

recover the cost of a household appliance.

President Nixon’s Message on the Protection of Inter

ests of Consumers, 91st Cong., 1st Sess., (1969).

Civil damage actions are only likely when a large group

of consumers have been victimized by fraudulent practices

so standardized as to meet the requirements of Rule 23,

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Since the last amend

ment to Rule 23 on July 1, 1966, only four of 424 reported

decisions in the District Court for the District of Columbia

involved local consumer initiated actions,6 even though

that District Court has the same plenary law and equity

jurisdiction of a base line state court. Vogel v. Tenneco

Oil Co., 276 F. Supp. 1008 (D.D.C., 1967). The President’s

Special Assistant for Consumer Affairs has advised the

Congress that the authorization of federal class actions

for all violations affecting commerce of federal and state

consumer protection laws—a grant of jurisdiction far

broader than that claimed here—would not impose any

great burden on the Federal judicial machinery. Hear

ings before the Subcommittee on Improvements in Judi

cial Machinery of the Senate Judiciary Committee, 91st

Cong., 1st Sess., 20 (1969) (Remarks of Mrs. Knauer).

The use of injunctions by consumer groups and public in

6 Telephone Users Assn., Inc. v .Pullic Service Comm, of D.C.,

271 F. Supp. 393 (1967); Tenants Council, etc. v. DeFranceaux, 305

F. Supp. 560 (1969); Young v. Ridley, 309 F. Supp. 1308 (1970);

Masszonia v. Washington, 315 F. Supp. 529 (1970).

15

terest law firms to prevent misrepresentations will serve

to reduce consumer fraud, and ultimately decrease the liti

gation growing out of such transactions.

The exercise of federal jurisdiction is especially appro

priate in the instant case, because it is only in the federal

courts that the instant plaintiffs have any hope of obtain

ing relief. Neither New York case law nor its statutes au

thorize consumers to obtain injunctions against business

frauds, as these plaintiffs seek to do. The Uniform De

ceptive Trade Practices Act, which the Court of Appeals

speculated might provide for such relief (Appendix p. 15a,

n. 35) has not been enacted in New York. Collection of

adequate damages for the 153 defrauded consumers is

also not feasible in state courts, since New York has effec

tively closed its courts to consumer class actions. Hall v.

Coburn Corporation of America, 26 N.Y. 2d 281 (1970).

Plaintiffs have already sought, without success, to obtain

assistance from the New York Attorney General and from

the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs

which referred them to private counsel. In short, plain

tiffs have brought this action in federal court, not, as the

Court of Appeals suggested, because they are “imagina

tive” (Appendix, p. 4a), but because they have no place

else to turn.

The use of section 43(a) by consumers victimized by

interstate consumer frauds continues to be urged within

the legal community. See e.g., Grimes, “Control of Adver

tising in the United States and Germany: Volkswagen Has

a Better Idea,” 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1769, 1774-6 (1971); Starrs,

“ The Consumer Class Action—Part I: Considerations of

Equity,” 49 Boston U. L.Rev. 211, 246-47 (1969). The

jurisdiction of the federal courts over such interstate frauds

and misrepresentations is a continuing problem which

should be finally resolved by this Court.

16

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Second Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit III

E ric Schnapper

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, N. Y. 10019

Philip G. Schrag

Columbia University

Law School

435 W. 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Counsel for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Court of Appeals

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the Second Circuit

No. 100—September Term, 1970.

(Argued October 8, 1970 Decided May 6, 1971.)

Docket No. 34737

Jo A nn Colligan, by her mother and next friend, Josephine

Gr. Colligan, and V alebie Shine, by her father and

next friend, W illiam Shine , on behalf of themselves

and all those similarly situated,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

—against—

A ctivities Club op New Y ork, L td., also known as New

Y ork W inter Ski Club, a corporation; F red K rasny;

Mbs. A lbert ; Peninsula B us Company, I nc., a corpora

tion; and B and C Bus L ine, I nc,, a corporation,

Defendants-Appellees.

B e f o r e :

M oore, Smith and A nderson,

Circuit Judges.

Appeal from an order of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of New York, Murphy, Judge,

dismissing an action brought by consumers seeking in

junctive relief and money damages under §43(a) of the

Lanham Act on the ground that they lacked standing to

maintain suit under the Act. Affirmed.

la

Appendix

Jack Greenberg, New York, N. Y. (Eric Schnap-

per, New York, N. Y., of counsel), for Plain

tiff s-Appellants.

Sidney J. Leshin, New York, N. Y., for Defen

dants-Appellees.

Moore, Circuit Judge:

This is an appeal from an order dismissing appellants’

class action for money damages, an accounting for profits

and an injunction brought under §43(a) of the Lanham

Act,1 on the ground that their claim failed to state a cause

of action. The district court ruled on its own motion that

the suit could not be maintained, because, as consumers, as

opposed to commercial plaintiffs, appellants lacked stand

ing to sue under §43(a). Without the benefit of any opposi

tion on appeal to appellants’ counsel’s able brief, which

sets forth the issues with beguiling simplicity, for the rea

sons stated below we nevertheless affirm.

USU.S.C. §1125(a).

Section 43(a) provides as follows:

“Any person who shall affix, apply or annex, or use in con

nection with any goods or services, or any container or con

tainers for goods, a false designation of origin, or any false

description or representation, including words or other sym

bols tending falsely to describe or represent the same, and shall

cause such goods or services to enter commerce, and any person

who shall with knowledge of the falsity of such designation of

origin or description or representation cause or procure the

same to be transported or used in commerce or deliver the same

to any carrier to be transported or used shall be liable to a

civil action by any person doing business in the locality falsely

indicated as that of origin or in the region in which said

locality is situated, or by any person who believes that he is or

is likely to be damaged by use of any such false description or

representation.”

3a

The two appellants, parochial school children, by their

parents and next friends, brought this suit on behalf of

themselves and as members of two classes: (1) 153 students

of the Sacred Heart Academy of Hempstead, New York,

who allegedly were deceived and damaged by “defendants’

use of false descriptions and representations of the nature,

sponsorship, and licensing of their interstate ski tour ser

vice” ;2 3 and (2) all high school students within the New

York metropolitan area who are likely to be deceived and

thereby injured by defendants’ similarly deceptive prac

tices in the future. The factual substance of the complaint

is summarized below.

Appellants and their 151 classmates prepaid defendant

Activities Club of New York, Inc. (the Club), $44.75 per

person as the full price for a ski tour to Great Barrington,

Massachusetts to be conducted during the weekend of Jan

uary 24, 1970, in reliance upon the Club’s representations

that: each child would be provided with adequate ski equip

ment and qualified instruction; safe, reliable and properly

certified transportation would be provided between New

York and Great Barrington; and all meal costs would be

included in the prepaid tour price.3 These representations

were conveyed by means of flyers, allegedly deceptively

similar to those of National Ski Tours, a well known and

reputable ski service, and by means of other written and

oral communications.

The ski weekend began as represented but was cut short

and proved otherwise unsatisfactory by the following de

Appendix

2 Complaint at 4a.

3 Complaint at 5a.

4a

velopments, which, for purposes of reviewing the dismissal

of a complaint we assume to be true: only 88 pairs of skis

and boots were provided for the 153 children; only one

“qualified” ski instructor was provided, who because of the

equipment shortage spent all of Saturday morning fitting

the children with such skis and boots as were available ;

the other “instructors” were high school and college stu

dents whose agreements with defendants provided for only

a few hours of instruction per day; one of the buses broke

down on a country road en route to Great Barrington,

stranding 40 children and two chaperones in the middle of

the night; another bus had faulty brakes and only one head

light and was ticketed by the Massachusetts police; another

bus en route back to New York poured exhaust fumes into

its interior; one of the bus drivers was intoxicated and

therefore unable ot drive his bus on the return trip to New

York; neither the buses nor the Club were licensed or cei'-

tified by the Interstate Commerce Commission; and one

busload of children was required to pay an unrefunded

total of $71.75 for an extra meal in Great Barrington due

to unsafe bus transportation.

In seeking redress of this apparently misfortune-strewn

ski weekend brought about by the Club’s misrepresenta

tions, appellants have sought to invoke the jurisdiction of

a federal court, rather than turning to traditionally avail

able state court forums and remedies and have appended

their state common law claims by way of invoking the

doctrine of pendent jurisdiction. Seemingly unable to bring

themselves within other federal statutes specially confer

ring federal court jurisdiction, and additionally unable to

meet the minimum monetary requirements of 28 U.S.C.

§1331 or 28 IT.S.C. §1332, appellants imaginatively have

Appendix

5a

brought this action pursuant to §§394 and 43(a) of the

Lanham Act.

The issue of consumer standing to sue under §43(a) is

one of first impression for this and apparently any federal

court. In concluding that it lacked jurisdiction, the dis

trict court below relied on Marshall v. Procter & Gamble

Mfg. Co.,5 6 which in turn relied without discussion on this

court’s per curiam opinion in the first reported §43(a) case,

Carpenter v. Erie B. C o5 Because both these cases are

clearly distinguishable from the issue at bar,7 and there

Appendix

415U.S.C. §1121.

Section 39 provides as follows:

“ The district and territorial courts of the United States shall

have original jurisdiction and the courts of appeal of the United

States shall have appellate jurisdiction, of all actions arising

under this chapter, without regard to the amount in contro

versy or to diversity of citizenship of the parties.”

5170 F. Supp. 828 (D. Md. 1959).

In Marshall, the district court concluded without discussion but

in very clear language that in an action under §43 (a) “ a member

of the public, as such, has no right of action under this section for

personal injuries based upon alleged misrepresentation,” that “ the

very broad language of Section 1125(a) [referring to 43 (a )’s use

of “ any person . . .” ] cannot be taken literally” and that “ the in

jury, to be actionable under the statute, must be one which occurs

in the area of commercial relations [though] the plaintiff . . . need

not be a direct competitor of the defendant.” 170 F. Supp. at 836,

n. 8.

6178 F.2d 921 (2d Cir. 1949), cert, denied, 339 U.S. 939 (1950).

7 Marshall is distinguishable because the court grounded its dis

missal on the inability of the plaintiff, suing in his capacity as an

inventor, to show the required commercial injury. Carpenter is

distinguishable on several grounds. First there were a number of

grounds for decision of which lack of standing under §43 (a) was

one ( “ [T]hat. section is applicable to no such circumstances as those

alleged in support of his claim” ), but a totally unnecessary one.

The statute of limitations on Carpenter’s previous claims had run

6a

fore not conclusive authority for the district court’s posi

tion, we find it necessary to explore in detail whether there

is any basis for appellants’ standing to sue under §§39

and 43(a).

Section 43(a) and “Plain Meaning”

Appellants’ principal contention is that the language of

§43(a), specifically the term “any person,” is so unambigu

ous as to admit of no other construction than that of per

mitting consumers the right to sue under its aegis. On

the face of the complaint all the prerequisites of §43(a)

seem to be met: (1) defendants are persons (2) who used

false descriptions and misrepresentations (3) in connection

with goods and services, (4) which defendants caused to

enter commerce; (5) appellants are also persons (6) who

believe themselves to have been in fact damaged by defen

dants’ misdescriptions and misrepresentations.

Viewing the terms of §43(a) in isolation there do not

appear to be any vague words or inconsistent phrases which

might permit any other inference than that which appel

lants would have us draw—i.e., that “ any person” means

exactly what it says.8 It is further suggested that if Con

Appendix

some ten years before the Lanham Act was enacted, and he was

“precluded from recovery in the present suit under the rule of res

judicata” 178 F.2d at 922. Finally, Carpenter, suing for “ mis

representation of services” in his capacity as an injured former

employee of the Brie Railroad, seems to have been a rather litigious

person; by the time he raised the §43 (a) claim, the court had grown

somewhat impatient with Carpenter’s reassertion of previously

barred claims, which the court said “ can never justify a recovery.”

Id.

8 We note that the key language in §43 (a) is not “ any person”

but “ any person who believes that he is or is likely to be damaged

by the use of any such false description or representation.” The

proper focus therefore is whether appellants’ claims partake of the

nature of the injury sought to be prevented and/or remedied by

Congress through §43 (a ).

7 a

gress had desired, it could and would have limited or nar

rowed the class of protected plaintiffs to commercial parties

merely by saying so. We reject this line of maxims of

statutory construction in favor of Judge Learned Hand’s

more practical instruction that “ [wjords are not pebbles

in alien juxtaposition,” 9 and therefore turn first to §43(a)’s

legislative history.

Appendix

Legislative H istory

We agree with appellants that “ [t]he Lanham Act of

1946 has a very long and convoluted legislative history,” 10

9 NLRB v. Federbush Company, Inc., 121 F.2d 954, 957 (2d Cir.

1941).

10 Br. at 16.

For bills containing versions of the measure ultimately enacted,

see H.R. 8637, 68th Cong., 1st Sess., S. 2679, 68th Cong., 2d Sess.;

H.R. 6348, 69th Cong., 1st Sess.; S. 4811, 69th Cong., 2d Sess.; H.R.

13486, 69th Cong., 2d Sess.; H.R. 6683, 70th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R.

11988, 70th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R. 2828, 71st Cong., 2d Sess.; H.R.

9041, 75th Cong., 3rd Sess.; H.R. 4744, 76th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R.

6618, 76th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R. 102, 77th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R.

5461, 77th Cong., 1st Sess. S. 895, 77th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R. 82,

78th Cong., 2d Sess.; H.R. 1654, 79th Cong., 2d Sess.

Congressional hearings on a trademark bill were held on 14

occasions. See Joint Hearings Before the Committees on Patents,

68th Cong., 2d Sess. (1925) ; Hearings Before the House Committee

on Paterits, 69th Cong., 1st Sess. (1926); id., 69th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1927) ; Hearings Before the Senate Committee on Patents, 69th

Cong., 2d Sess. (1927) ; Hearings Before the House Committee on

Patents, 70th Cong., 1st Sess. (1928); id., 71st Cong., 2d Sess.

(1930) ; id,., 72nd Cong., 1st Sess. (1932) ; id., 75th Cong., 3rd Sess.

(1938) ; id., 76th Cong., 1st Sess. (March 1939); id., 76th Cong., 1st

Sess. (June 1939) ; id., 77th Cong., 1st Sess. (1941); Hearings

Before the Senate Committee on Patents, 77th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1942) ; Hearings Before the House Committee on Patents, 78th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1943) ; Hearings Before the Senate Committee on

Patents, 78th Cong., 2d Sess. (1944).

The various versions of the trademark bill were discussed in nine

committee reports. See H.R. Rep. 944, 76th Cong., 1st Sess. (1939) ;

8a

which with respect to §43(a) we find to be inconclusive

and therefore of little or no help in resolving the issue de

cided today. We are cited by counsel to certain statements,

actions and inactions and are asked to make certain causal

connections among them and then to draw a set of pre

ferred inferences therefrom. Counsel lay stress, for ex

ample, on the following statement made before a joint con

gressional committee in 1925 by a representative of the

U.S. Trademark Association with respect to the language

of a bill’s provision, which, in substantially modified form,

became §43(a):

“It provides that any person who is damaged by the

false description may start the suit. Obviously the

purchaser might claim that he has been misled and

damaged and start suit. At any rate, if it is intended

to limit the right to start such a suit, that limitation

should be stated.” 11

None of the committee members or draftsmen of §30 of the

1925 bill expressed any disagreement with this statement,

and the provision remained unchanged, containing no ex

press limitation barring consumer suits.

We are asked to conclude from this ancient history that

the committee’s silence, followed by its inaction with respect

to amending this portion of the bill, must mean that Con

gress clearly intended to create standing for consumers

Appendix

S. Rep. 1562, 76th Cong., 3rd Sess. (1940); S. Rep. 568, 77th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1941); H.R. Rep. 2283, 77th Cong., 2d Sess. (1942); H.R.

Rep. 603, 78th Cong., 1st Sess. (1943); S. Rep. 1303, 78th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1944); H.R. Rep. 219, 79th Cong., 1st Sess. (1945) ; S. Rep.

1333, 79th Cong., 2d Sess. (1946); Conf. Rep. 2322, 79th Cong., 2d

Sess. (1946), for which see 92 Cong. Rec. 7522.

11 Joint Hearings Before the Committee on Patents, 68th Cong.,

2d Sess., 127-128 (1925) (statement of Arthur W . Barber).

9a

under the 1946 Act. On this flimsy record, it would be self-

serving for us to invoke the doctrine of “ silence as ac

ceptance” as a. basis upon which to draw any consequential

inference with respect to §43(a)’s legislative history.12 We

believe it more likely that the committee members evidenced

no disagreement or agreement with the interpretation given

§30 by the above-quoted statement because neither was

necessary; the committee members probably were suffi

ciently confident of their own interpretation that they felt

that no clarification by way of reply and/or amendment

was needed to implement their intention to confer standing

solely upon commercial plaintiffs.

It is also suggested that since the statutory predecessor

of §43 (a), §3 of the Trademark Act of 1920,13 was addressed

solely to the prohibition of false designations of origin and

authorized suit only by persons, corporations, etc., “ doing

business in the locality falsely indicated as that of origin

[emphasis supplied],” 14 and since this type of language

12 Compare Chicago, M., St. P. B. Co. v. Acme Freight, Inc., 336

XJ.S. 465, 474-475 (1949), in which the Supreme Court gave substan

tial weight to the unchallenged and uncontradicted statement of a

ranking minority congressional committee member who spoke in

behalf of the bill [of which he was a principal draftsman and sup

porter] and presented the only extended exposition of its provi

sions” on the floor of the House in clear contradiction of the com

mittee’s report.

13 41 Stat. 534,104, §3.

14 This provision, although relevant for purposes of this discus

sion was in fact deemed to be a “ dead letter,” due principally to

the requirement of proof of wilfulness or intent to deceive, a defect

corrected by successor draft bills and ultimately by §43(a). See

Parkway Baking Co. v. Freihofer Baking Co., 255 F.2d 641, 648

n 7 (3d Cir. 1958); California Apparel Creators v. Weider of

California, 162 F.2d 893 (2d Cir.), cert._ denied, 332 U.S. 816

(1947); see also Derenberg, Federal Unfair Competition Law at

the End of the First Decade of the Lanham A ct: Prologue or Epi

logue, 32 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 1029,1035 (1957) (hereinafter Derenberg).

Appendix

XOa

was preserved in several early drafts of what became

§43(a)1E but was ultimately dropped by the A.B.A. Trade-

Mark Committee in favor of a provision permitting suit by

“any person, firm or corporation who is or is likely to be

damaged by the use of any false description or representa

tion,” 15 16 we should conclude that the A.B.A. rejection of the

earlier colorably restrictive language and the congres

sional acceptance of the colorably broader A.B.A. language

“ clearly indicates an intent [attributable to Congress]17

not to restrict the provision to actions by businessmen and

tradesmen,” and “a [congressional] concern to expand the

class and type of person authorized to sue.” 18 We, on the

other hand, construe the deletion of the phrase “ in his trade

or business” from the earlier A.B.A. drafts to be equally

consistent with a clearly expressed congressional purpose19

to create a federal statutory tort of unfair competition

sui generis,20 thus rendering the subject phrase to the status

of mere surplusage.

15 For example, an initial draft submitted by Mr. Edward S.

Rogers to the A.B.A. Trade-Mark Committee authorized suit by

“ any person . . . who is or is likely to be damaged in his trade or

business by any false description . . . [emphasis supplied]” Mise.

Bar Ass’n Reps., v. 22, item 26, §27, Ass’n of the Bar of N.Y. catal.

no. BA Misc. 681, v. 22.

16 Id., item 27, §27 (Rogers Preliminary Draft with Revisions)

item 28, §27 (Committee Preliminary Draft, Second Revision) ;

item 25, §30 (Committee final d ra ft); item 29, §30 (Version ap

proved by A.B.A. House of Delegates).

17 Cf. Shapiro v. United States, 335 U.S. 1, 12 n. 13 (1948).

18 Br. at 21.

19 See 15 U.S.C., §1127, to be diseussedm/ra.

20 Gold Seal Co. v. Weeks, 129 F. Supp. 928, 940 (D.D.C. 1955),

aff’d sub nom, S. C. Johnson & Son, Inc. v. Gold Seal Co., 230 F.2d

832 (D.C. Cir. 1956), cert, denied 352 U.S. 829 (1956) ; see also

Maternally Yours v. Your Maternity Shop, 234 F.2d 538 (2d Cir.

1956) (concurring opinion of Chief Judge Clark).

Appendix

11a

Purpose op §43(a) and P ublic P olicy

Appellants urge that under the test of Association of

Data Processing Serv. Org. v. Camp,21 they as consumers

have standing under the Lanham Act because they have

demonstrated injury in fact and that they come within a

group “ arguably within the zone of interests to be pro

tected” 22 by the Act. Although the scope and effects of

Data Processing have not yet been clearly delimited,23 we

hold that that case does not bring these appellants under

its protective wing.

The congressional statement of purpose of the Act24 * 26 is

contained in §45,26 which in pertinent part states: “The

intent of this chapter . . . is to protect persons engaged

in such commerce against unfair competition.” In this,

the only phrase referring to the class of persons to be

protected by the Act, as defined by their conduct and the

source of the injuries sought to be protected against, no

mention at all is made of the “public” or of “consumers.”

The legislative history of the Act, such as it is, adds

nothing. We do know to a reasonable certainty, however,

that the consumer protection explosion and the wholesale

displacement (though not preemption) of traditional state

statutory and common law remedies—matters pregnant

with manifold consequences of great importance—-were

never considered or foreseen by Congress prior to the

21 397 U.S. 150 (1970).

22 397 U.S. at 153.

23 See Jaffe, Comment, Standing Again, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 633,

634 (1971).

24 See Cousaw Mining Co. v. South Carolina, 144 U.S. 550, 563

(1892).

2615 U.S.C. §1127.

Appendix

12a

enactment of §43(a). We conclude, therefore, that Con

gress’ purpose in enacting §43(a) was to create a special

and limited unfair competition remedy, virtually without

regard for the interests of consumers generally26 and al

most certainly without any consideration of consumer

rights of action in particular. The Act’s purpose, as defined

in §45, is exclusively to protect the interests of a purely

commercial class against unscrupulous commercial con

duct.26 27 28

This view is supported by the leading case of L’Aiglon

v. Lana Lobell, Inc.,M which, while expanding the statu

26 See Standard Brands, Inc. v. Smidler, 151 F.2d 34, 37-43 (2d

Cir. 1945) (concurring opinion of Judge Frank) for a learned

discussion of the historical-legal relationship between protection of

commercial interests and consumer interests under the rubric of

unfair competition, which relationship comprises the background

against which Congress enacted §43(a).

27 The court in Gold Seal Co. v. Weeks, 129 F. Supp. 928, 940

(D.D.C. 1955), succinctly stated the import of §43 (a) :

“ It means that wrongful diversion of trade resulting from false

description of one’s products invades that interest which an

honest competitor has in fair business dealings— an interest

which the courts should and will protect . . . It represents,

within this area, an affirmative code of business ethics whose

standards may be maintained by anyone who is or may be

damaged by this segment of the code. In effect it says: you

may not conduct your business in a way that unnecessarily or

unfairly interferes with and injures that of another; you may

not destroy the basis of genuine competition by destroying the

buyer’s opportunity to judge fairly between rival commodities

by introducing such factors as false descriptive trademarks

which are capable of misinforming as to the true qualities of

the competitive products.”

Although the language of the Gold Seal court would seem to

permit the interpretation suggested by appellants, it seems very

clearly the other way when read in the light of Judge Frank’s

concurring opinion in Smidler.

28 214 F.2d 649, 651 (3d Cir. 1954).

Appendix

13a

torily protected class by giving an expansionary reading

to the substantive content of §43(a), still limited the pro

tected class to commercial, though not necessarily com

petitive,29 plaintiffs.30 Although admittedly the L’Aiglon

court was not presented with the question of consumer

standing under §43(a), we deem the court’s opinion in con

text to set the outer limits of the class of §43(a) plaintiffs

contemplated by Congress. As the court noted, although

§43(a) was intended to create a federal unfair competition

count, since “the Lanham Act was not intended to bring

all unfair competition in commerce within federal juris

diction,” 31 it was intended to be a special, limited one cov

Appendix

29 Gold Seal Co. v. Weeks, 129 F. Supp. 928 (D.D.C. 1955), aff’d

siob nom. S. C. Johnson & Son. Inc. v. Gold Seal Co., 230 F.2d 538

(D.C. Cir. 1956), cert, denied, 352 U.S. 829 (1956); Yameta Co. v.

Capitol Records, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 582, 586 (S.D.N.Y. 1968).

30 Appellants also rely on the famous passage in Chief Judge

Clark’s concurring opinion in Maternally Yours v. Your Maternity

Shop, 234 F.2d 538, 546 (2d Cir. 1956), that “ the bar has not yet

realized the potential impact of this statutory provision.” We con

strue that statement in context to refer to the federal courts’ re-

lucance at that time to broaden the substantive scope of §43(a), as

that section represented in Chief Judge Clark’s view an oppor

tunity and an invitation to create a federal law of unfair competi

tion, 'which embraces far more than mere “ passing off,” the unduly

narrow application of the provision prevalent at that time. See 234

F.2d at 546-547.

31214 F.2d at 654.

The Lanham Act originally included a specific section which

read: “All acts of unfair competition in commerce are declared

unlawful.” This language was later dropped because it was re

garded as “ dangerously broad.” Derenberg at 1063. This court

has rejected the view that the Lanham Act, through §44(i), 15

U.S.C. §1126 (i), creates independent federal jurisdiction over the

entire field of unfair competition. See American Auto. Ass’n v.

Speigal, 205 F.2d 771, 774 (2d Cir.), cert, denied, 346 U.S. 887

(1953) ; approved, Derenberg at 1061; compare Stauffer v. Exley,

184 F.2d 962 (9th Cir. 1950).

14a

Appendix

ering only those cases in which false description and/or

false designation of origin are alleged.82 Since Congress

deliberately excluded from coverage virtually all categories

of unfair competition but for false advertising, it could

not have intended to create a whole new body of substan

tive law completely outside the substantive scope of unfair

competition. Yet this is what appellants would have us

find, under the guise of granting them standing, for the

question of consumer standing and that of the creation of

wholly new federal common law of consumer protection

under §43(a) cannot be disentwined.32 33

Moreover, consumers’ use of §39 of the Act, which re

quires the allegation of neither a minimum monetary

amount in controversy nor diverse citizenship, in combina

tion with the expansive jurisdictional delineation given the

phrase “in commerce,” 34 * and the procedural advantages of

bringing suit in federal court, would lead to a veritable

flood of claims brought in already overtaxed federal dis

trict courts, while adequate private remedies for consumer

protection, which to date have been left almost exclusively

to the States, are readily at hand. Great strides are now

32 Chief Judge Hastie stated, “ This statutory tort bears closest

resemblance to the . . . tort of false advertising to the detriment of

a competitor, as formulated by the ALI . . which tort makes

clear that consumers must rely on other sections. Section 761 of the

Restatement of Torts in pertinent part provides as follows:

“ One who diverts trade from, a competitor by fraudulently rep

resenting that the goods which he markets have ingredients

which in fact they do not have but which the goods of the com

petitor do have, is liable to the competitor . . .” [emphasis,

supplied].

33 See Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills, 353 U.S. 448

(1957) (dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice Frankfurter).

34 See Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964) and its

progeny.

15a

being made in this area to expand the already numerous

remedies available in state courts,35 and this court has no

desire to interfere with that process by an unprecedented

interpretation of longstanding federal law.36

One of appellants’ arguments favoring a literal inter

pretation of “any person” is that “ [h]ad Congress desired

to limit actions under section 43(a) to those brought by

competitors or by commercial concerns generally, it could

and would have so provided.” Our analysis requires that

the manner in which this issue be posed is precisely the

reverse: had Congress contemplated so revolutionary a de-

Appendix

36 State authorities have been far from lethargic in responding

to the current consumer protection explosion. See, e.g., the Revised

Uniform Deceptive Practices Act in Handbook of the National

Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws 306-315

(1966), which was initially approved by the Commissioners on Uni

form State Laws and by the A.B.A. House of Delegates in 1964,

and which has been adopted by eight- states (Connecticut, Deleware,

Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, New Mexico and Oklahoma). Sec

tion 3(a) of the Uniform Act has been construed unofficially to

confer standing on defrauded consumers seeking injunctive relief

(no money damages are provided) although the Uniform Act

“ originated as an effort to reform the law of business torts, not

consumer torts.” See Dole, Consumer Class Actions Under the

Uniform Deceptive Practices Act, 1968 Duke L.J. 1101, 1107, 1109.

Mr. Dole was a consultant to the Special Committee on Unfair

Competition of the National Conference of Commissioners on Uni

form States Laws from 1962 to 1965. See also the recently amended

Massachusetts “ Regulations of Business and Consumer Protection

Act,” Mass. Acts, ch. 690, ch. 814 (1969), amending Mass. Ann. L.

ch. 93A, §§1-8 (Supp. 1968); Goodman, An act to Prohibit Unfair

and Deceptive Trade Practices, 7 Harv. J. Legis. 122, 146-153

(1969).

36 Cf. Phillips v. Rockefeller, 435 F.2d 976, 980 (2d Cir. 1970)

(construction of the Seventeenth Amendment).

16a

parture implicit in appellants’ claims, its intention conld

and would have been clearly expressed.37

Affirmed.

Appendix

37 Cf. Herpich v. Wallace, 430 F.2d 792, 809 (5th Cir. 1970)

(scope of §10 (b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934) • 2 L.

Loss, Securities Regulation 902-903 (2d ed. 1961) (scope of SEC

power under §14 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934).

Although we hold that consumers have no right of action under

§43(a), we note that the federal government through the Federal

Trade Commission has intervened in the marketplace and in the

courts to vindicate the rights of the consuming public. Chief Judge

Clark in his concurring opinion in the California Appeal case

stated:

“ So far as the consumer is concerned, he is not dependent upon

the private remedial actions brought by competitors for the

remedies under the Federal Trade Commission A c t . . . are now

extensive . . . ”

162 F.2d 896; accord, 1 R. Callman, Unfair Competition, Trade

marks and Monopolies §18.2 (b ), at 626 (3d ed. 1967). That Chief

Judge Clark’s faith in the FTC perhaps has proved excessive, see

e.g., A.B.A. Committee to Study the Federal Trade Commission

Report (1969); E. Cox, R. Fellmeth & J. Schulz, The Nader Report

on the Federal Trade Commission (1969); Baum, The Consumer

and the Federal Trade Commission, 44 J. Urb. L. 71 (1966), does

not derogate from our conclusion that commercial and consuming

classes intentionally have been provided separate remedies.

Judgment of the Court of Appeals

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the Second Circuit

At a Stated Term of the United States Court of Appeals,

in and for the Second Circuit, held at the United States

Courthouse in the City of New York, on the sixth day of

May one thousand nine hundred and seventy-one.

P r e s e n t :

H on. L eonard P. M oore,

H on. J. Joseph Smith ,

H on. R obert P. A nderson

Circuit Judges.

Jo A nn Colligan, by her mother and next friend, Josephine

G. Colligan, V alerie Shine, her father and next friend,

W illiam S hine, on behalf of themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

A ctivities Club of New Y ork, L td., also known as New

Y ork W inter Ski Club, a corporation, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York.

This cause came on to be heard on the transcript of

record from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York, and was argued by counsel.

On c o n s i d e r a t i o n w h e r e o f , it is now hereby ordered,

adjudged, and decreed that the order of said District Court

be and it hereby is affirmed.

A. Daniel F usaro

Clerk

17a

18a

Opinion of the District Court

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Southern D istrict of New Y ork

69 Civ. 2194

Jo A nn Couligan, by her mother and nest friend, Josephine

G. Colligan, and V alerie Shine , by her father and

next friend, W illian Shine, on behalf of themselves

and all others similarly situated,

— against-

Plaintiffs,

A ctivities Club of New Y ork, L td., also known as New

Y ork W inter Ski Club, a corporation; F red K rasny;

Mrs. A lbert ; Peninsula B us Company, I nc., a corpora

tion, Champion Bus Company, I nc., a corporation;

and B and C Bus L ines, Inc., a corporation,

Defendants.

M urphy, D. J.

Plaintiffs move for an order pursuant to Rule 23(c)

of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure declaring that

this action may be maintained as a class action, defining the

represented classes and subclasses, and declaring that said

classes and subclasses have standing to maintain the action.

The action is brought pursuant to sections 39 and 43(a)

of the Lanham Act of 1946 (15 U.S.C. §§1121 and 1125(a)).

The two infant petitioners by their parents and next

friends bring suit on behalf of themselves and as members

of two classes: (1) 153 students of the Sacred Heart

Academy, Hempstead, New York, who were allegedly

19a

deceived and damaged by defendants’ false representa

tions as to the rendering of the defendants’ services, and;

(2) all high school students within the New York metro

politan area who may be deceived in the future by the

alleged false representations of the defendants.

The plaintiffs and 151 others students of the Sacred Heart

Academy, a parochial high school, purchased the services

of the defendants pursuant to an advertisement. Three

of the named defendants are ski tour operators, and the

other three defendants are bus line companies. Each of

the 153 students paid $44.75 for a ski tour. The plaintiffs

allege that false representations were made by the defen

dants and that they did not receive all of the services

promised them.

The plaintiffs, as representatives of all high school

children in the New York area, seek to enjoin the ski tour

defendants from making further misrepresentations of

goods or services in commerce and from using flyers

imitating those of a competitor, and the bus company

defendants from participating in any misrepresentations.

Assuming, without deciding, that the requirements of

Rule 23(a) and (b) are met, we feel constrained to resolve

first the question whether such an action is authorized

under the Lanham Act (15 TT.S.C. §1125(a) which provides

in part:

“Any person who shall . . . use in connection with any

goods or services . . . any false description or

representation, including words or other symbols

tending falsely to describe or represent the same, and

shall cause such goods or services to enter into com

merce, and any person who shall with knowledge or the

falsity of such . . . description or representation cause

Appendix

20a

or procure the same to be transported or used in com

merce or deliver the same to any carrier to be trans

ported or used, shall be liable to a civil action by any

person doing business in the locality falsely indicated

as that of origin or in the region in -which said locality

is situated, or by any person who believes he is or is

likely to be damaged by the use of any such false

description or representation. (Emphasis added.)

and section 39 which provides:

“ The district and territorial courts of the United States

shall have original jurisdiction and the courts of appeal

of the United States shall have appellate jurisdiction,

of all actions arising under this chapter, without regard

to the amount in controversy or to diversity or lack

of diversity of the citizenship of the parties.”

It is the plaintiffs’ submission that “ [t] he clear language

of this statute gives a right of action to a consumer or

potential consumer who is damaged or likely to be damaged

by misrepresentation of goods or services in interstate

commerce” and concedes that there is little judicial au

thority confirming consumer standing to invoke the statute.

They point out that in the only two cases in which a non

commercial plaintiff unsuccessfully attempted to invoke

the Act the issue of consumer standing was not reached.

Carpenter v. Erie R.R., 178 F.2d 921 (2d Cir. 1949) ;

Carpenter v. Rohm & Wass Co., 109 F.Supp. 739 (D.Del.

1952), aff’d, 201 F.2d 671 (3 Cir. 1953).

It is undoubtedly true that section 1125(a) creates a

limited new federal statutory tort and does not merely

codify the common law principles of unfair competition.

L’Aiglon Apparel, Inc. v. Lana Lobell, Inc., 214 F.2d 649

Appendix

21a

(3d Cir. 1954); The American Eolex Watch Corp. v. Jack

Laufer & Jan Voort, Inc., 176 F. Supp. 858 (EJD.N.Y. 1959);

Mutation Mink .Breeders Ass’n v. Lou Nierenberg Corp.,

23 F.E.D. 155 (S.D.N.Y. 1959).

Judge Hastie, however, did observe in L’Aiglon :

“ This statutory tort is defined in language which differ

entiates it in some particulars from similar wrongs

which have developed and have become defined in the

judge made law of unfair competition. Perhaps this

statutory tort bears closest resemblance to the already

noted tort of false advertising to the detriment of a

competitor, as formulated by the American Law In

stituted out of materials of the evolving common law

of unfair competition. See Torts Eestatement, Section

761, supra. But however similar to or different from