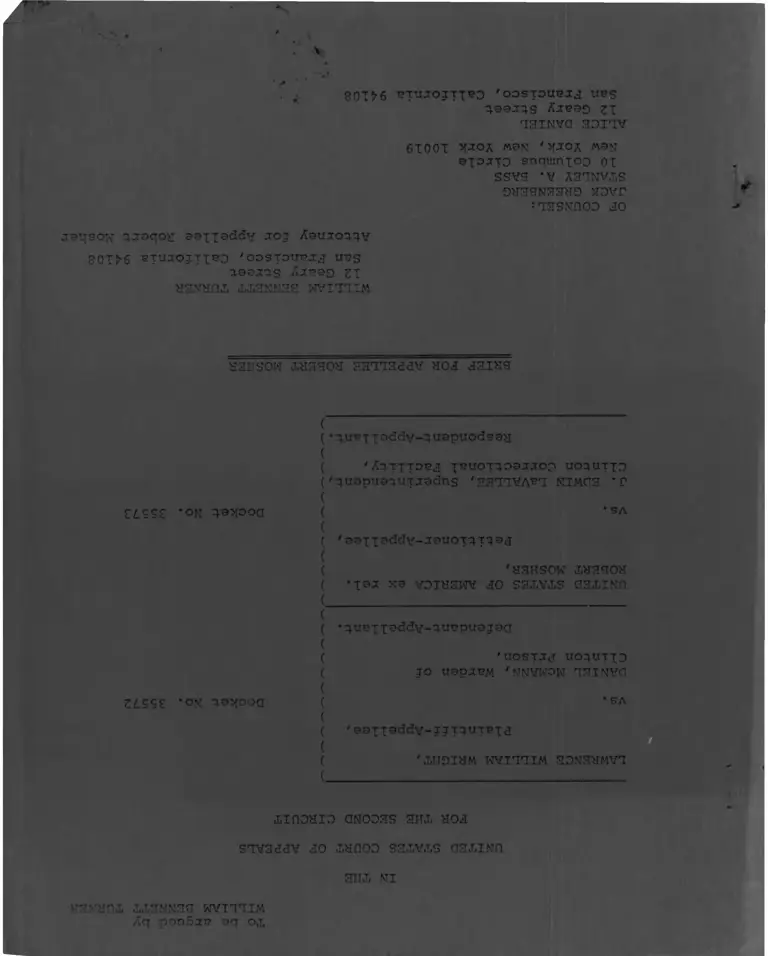

Wright v. McMann Brief for Appellee

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. McMann Brief for Appellee, 1971. b4c6b77e-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/13e0f5fd-6465-4ec3-acce-574f2f07dc6e/wright-v-mcmann-brief-for-appellee. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

801^6 ^TU^OJTX^D 'OOSTOUBJJ UPS

qaajrqs A.ZPS0 ZT

93INY0 30I3Y

61001 M9N 'VOA MSN

eXOJTD snqumxoo oi

SSY9 'V A33NY3,S

D339N333D 30Y0

: TEISNOOO 30

aqsow q^aqoH aaqqaddv :roj Aauaoqqv

S0I^6 ^xuao^TXBD 'oostoupjj u ps

qaaaqs A;n?ao ZT

333 3 0 3 333NN39 w i t i i h

33HS0H 333903 33993ddY 303 33133

(( •quPXiaddv-O-uapuodsaH

(( 'AqxxT^a XeuoT333^^O0 uoquxxo

('quapuaquTjadns '3333VA^3 MIMCI3 T

(

Z L Z Z Z * ON qs^ooa ( *SA

(( ' aaxxsd^V-J^uoTqTqad:

(( /H3HS0W 3,33903

( *X9J X9 Y0I33WY 30 S33Y3S 033IN0

(_________________________________________

(( • quuxi0<3dY-3UPpuag:aa

(( 'uostJd uoquxxo

( jo uapaPM 7 NNYKPW 93INYCI

(

Z L Z Z Z "OM qo^aoa (

(

( 'aaxx^ddv-jjxquxpxd

(( ' 3H0I3M WYI99IM 30N33MY9

(_________________________________________

iinodio o n o d o s 3H3 303

STY3ddY 30 3,3300 S33Y3S 033,130

3II3j MI

333303, 333NN39 WYI39IM

Aq ponBjp aq 03

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............................. iv

STATEMENT OF FACTS ................................ 1

1. Punitive Segregation ........................ 5

2. Disciplinary Procedures Leading To

Segregation Or Loss Of Good T i m e ............ 14

3. Psychiatric Observation Cells ............. 16

4. Prohibition Against Inmate

Legal Assistance............................ 18

5. Withholding And Censorship Of

Attorney-Client Correspondence ............. 18

QUESTIONS PRESENTED .............................. 19

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Properly Held That

Appellee Mosher Was Unconstitutionally

Punished.................................... 21

(1) Extraordinarily Severe Conditions

of Punitive Segregation ................ 22

(2) Excessively Long Period of Segregation . . 25

(3) Loss of "Good T i m e " .................... 26

(4) Lack of Any Justification for

the Punishment.......................... 27

II. The District Court Properly Ordered The

Restoration Of Mosher's Statutory Good Time

Lost By Reason Of Wrongful Punishment . . . . 33

III. Mosher's Extraordinary Punishments Were

Imposed In Violation Of Rudimentary

Procedural Due Process ....................... 26

Page

ii

Page

IV. The District Court Properly Enjoined

Use Of Psychiatric "Observation" Cells

For Disciplinary Purposes And Required

Appropriate Safeguards For Their

Future Use ..............................

V. The District Court Properly Enjoined

The Prison Officials From Censoring And

Interfering With Correspondence Between

Appellee Mosher And The Attorney Appointed

By The District Court To Represent Him

In This Action ..........................

VI. The District Court Properly Ordered The

Prison Officials To Permit Legal Assistance

Among Prisoners, Where The State Provides

No Alternative Means of Legal Assistance

To Prisoners ............................

CONCLUSION 53

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

Anderson v. Nosser, 438 F.2d 183

(5th Cir. 1971) 23,31

Ayers v. Ciccone, 303 F .Supp. 367

(W.D. Mo. 1969), aff'd, 431 F.2d 724

(8th Cir. 1970) 33

Barnes v. Hooker, No. R-2071

(D.,Nev. Sept. 5 , 19 69) 23

Barnett v. Rodgers, 410 F .2d 995

(D.C. Cir. 1969) 48

Beard v. Alabama Board of Corrections,

413 F.2d 455 (5th Cir. 1969) 52

Bearden v. South Carolina, F .2d ,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2231 (4th Cir.

June 10, 1971) 38

Bey v. Connecticut State Board of Parole,

F.2d , 39 U.S.L.W. 2695

(2d Cir. May 17, 1971) 39

Brooks v. Florida, 389 U.S. 413 (1967) 23

Brown v. Peyton, 437 F.2d 1228

(4th Cir. 1971) 48

Bundy v. Cannon, F.Supp. ,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2254 (D. Md.

May 26, 1971) 41

Candelaria v. Mancusi, Civ.No. 1970-491

(W.D. N.Y. Jan. 7, 1971) 48

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014

(S.D. N.Y. 1970) 31,34,35,36,

41,48,52

Carter v. McGinnis, 320 F.Supp. 1092

(W.D. N.Y. 1970) 31

Clutchette v. Procunier, F.Supp. ,

No. C-70 2497 AJZ (N.D. Cal.

June 21, 1971) 39,41

iv

Page

Coleman v. Peyton, 362 F.2d 905

(4th Cir.), cert, denied, 385 U.S.

905 (1966) 51

Coonts v. Wainwright, 282 F.Supp. 893

(M.D. Fla. 1968), aff'd, 409 F.2d 1337

(5th Cir. 1969) 52

Covington v. Harris, 419 F.2d 617

(D.C. Cir. 1969) 46

Dabney v. Cunningham, 317 F.Supp. 57

(E.D. Va. 1970) 31

Davis v. Lindsay, 321 F.Supp. 1134

(S.D. N.Y. 1970) 31

Dearman v. Woodson, 429 F.2d 1288

(10th Cir. 1970) 30

Edwards v. Schmidt, 321 F.Supp. 68

(W.D. Wis. 1971) 35

Escalera v. New York City Housing

Authority, 425 F.2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970) 40

Fortune Society v. McGinnis,

319 F.Supp. 901 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) 48

Fulwood v. Clemmer, 206 F.Supp. 370

(D. D.C. 1962) 30,48

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 (1970) 40

Hancock v. Avery, 301 F.Supp. 786

(M.D. Tenn. 1969) 23,30,35

Holmes v. New York Housing Authority,

398 F.2d 262 (2d Cir. 1968) 32

Holt v. Sarver, 300 F.Supp. 825

(E.D. Ark. 1969) 23

Holt v. Sarver, 309 F.Supp. 362

(E.D. Ark. 1970) 31

Houghton v. Shafer, 392 U.S. 639 (1968) 35

Hurtado v. California, 110 U.S. 516 (1884) 32

v

Page

Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F .2d 571

(8th Cir. 1968) 28,29,31

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529

(5th Cir. 1968) 29

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969) 34,52

Jones v. Robinson, 440 F.2d 249

(D.C. Cir. 1971) 41

Jordan v. Fitzharris, 257 F.Supp. 674

(N.D. Cal. 1966) 23,30,31

Katzoff v. McGinnis, 441 F.2d 558

(2d Cir. 1971) 35

Landman v. Peyton, 370 F .2d 135

(4th Cir. 1966) 21,27

Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137 (1803) 32

Marsh v. Moore, F.Supp. ,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2098 (D. Mass.

April 8, 1971) 51

In re Medley, 134 U.S. 160 (1890) 24

Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967) 39

Meola v. Fitzpatrick, 322 F.Supp. 878

(D. Mass. 1971) 41,48,51

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) 39

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) 35

Morales v. Turman, Civ. No. 1948

(E.D. Tex. March 1, 1971) 51

Moreno v. Henckel, 431 F .2d 1299

(5th Cir. 1970) 35

Morris v. Tr^visono, 310 F.Supp. 857

(D. R.I. 1970) 41

Nolan v. Fitzpatrick, 326 F.Supp. 209

(D. Mass. 1971) 51

Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F .2d 548

(1st Cir. 1970) 41,48

vi

Pacie-

Palmigiano v. Travisono, 317 F.Supp. 776

(D. R.I. 1970)

Payne v. Whitmore, No. C-70 2727 ACW

(N.D. Cal. Jan. 14, 1971)

People v. Dorado, 62 Cal.2d 338,

42 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1965)

People v. Wainwright, ___ F.Supp. ___,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2038 (M.D. Fla.

March 15, 1971)

Rhem v. McGrath, ___ F.Supp. ___,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2038 (S.D. N.Y.

March 17, 1971)

Rivers v. Royster, 360 F.2d 592

(4th Cir. 1966)

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962)

Rodriguez v. McGinnis, ___ F.2d ___,

No. 34567 (2d Cir. 1971)

Smith v. Robbins, ___ F.Supp. ___,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2288 (D. Me.

June 18, 1971)

Smoake v. Fritz, __ F.Supp. ___,

No. 70 Civ. 5103 Cs.D. N.Y. 1970)

Sostre v. McGinnis, ___ F.2d ___

(2d Cir. 1971)

Stevenson v. Mancusi, ___ F.Supp. ___,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2175 (W.D. N.Y.

April 20, 1971)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education,, U.S. ,

9 S. Ct. 1267 (1971)

United States v. Wade, 383 U.S. 218 (1967)

United States ex rel. Campbell v. Pate,

401 F.2d 55 (7th Cir. 1968)

48,51

51

39

51

51

35

31

35

51

31

11,21,22,23,25,

28,29,30,31,33,

34,36,37,38,43,

46,47,48,49,50,52

52

45

39

26,34

v n

Page

United States ex rel. Hancock v. Pate,

223 F.Supp. 202 (N.D. 111. 1963) 26,31

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910) 30

Williams v. Robinson, 432 F.2d 637

(D.C. Cir. 1970) 46

Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519

(2d Cir. 1967) 23,35,44

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356,

6 S. Ct. 1064 (1886) 32

STATUTES, RULES AND REGULATIONS

28 U.S.C. Section 2254 34

42 U.S.C. Section 1983 34

Federal Bureau of Prisons,

Policy Statement 7400.5 (Nov. 28, 1966) 24

Federal Bureau of Prisons,

Policy Statement 7400.6 (Dec. 1, 1966) 42

New York Department of Correction,

7 N.Y.C.R.R. Part 300 et seĉ . 24

New York Department of Correction,

7 N.Y.C.R.R. Section 253.3 40

New York Department of Correction,

7 N.Y.C.R.R. Section 253.5 26

Office of Adult Corrections, State

Washington, Memorandum No. 70-5

(Nov. 6, 1970)

of

51

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Atty. Gen. Op. 409/70, Feb. 11, 1971;

8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2486 39

Hirschkop and Milleman, The

Unconstitutionality of Prison

Life, 55 Va. L. Rev. 795 (1969) 42,50

viii

\

Page

Manual of Correctional Standards,

American Correctional Association,

413 (1966) 24,25

Model Penal Code, proposed official

draft, Section 304.7(3) (1962) 25

President's Commission on Law Enforcement

and Administration of Justice, Task

Force Report, Corrections, 13 (1967) 41,42

Turner, Establishing the Rule of Law in

Prisons, 23 Stan. L. Rev. 473 (1971) 41,51

i

ix

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

) ■

)

)

)

)) Docket No. 35572

)

) ■

)

)

)

)

')

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ex rel. )

ROBERT MOSHER, )

)

Petitioner-Appellee, )

)vs ) Docket No. 35573

)

J. EDWIN LaVALLEE, Superintendent,)

Clinton Correctional Facility, )

)

Respondent-Appellant. )

)

LAWRENCE WILLIAM WRIGHT,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

vs.

DANIEL McMANN, Warden of

Clinton Prison,

Defendant-Appellant.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEE ROBERT MOSHER

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The material facts in Robert Mosher’s case are

1/not in dispute.

1/ The district court noted that the proposed findings of

fact submitted by appellees were "accurately keyec to the

record and exhibits" and were "helpful. . .for convenient

reference and as an aid to those who may be next to review

and consider this substantial record" (153a). Mosher's

proposed findings are printed in the Appendix at 98a-134a.

-1-

After pleading guilty to the crime of robbery,

appellee Mosher began serving his 40-60 year sentence at

y

Clinton Prison in July, 1964 (TM 1C06-8, 1199). He had

no disciplinary difficulties at all for over a year and, for

aught that appears, made a satisfactory adjustment to life

3/

at the prison (Exh. 2). During his first three years at

the prison, Mosher was charged with only four very minor

disciplinary offenses, one of which he disputed having

committed. He worked successfully in the prison industrial

program. He posed no danger to the security or order of

the institution. He has never, during his entire term of

incarceration, been accused of any act or threat of violence

or any conduct menacing the security or order of the

institution (TM 1045).

On March 28, 1967, Mosher was presented in the

prison weave shop with an industrial "safety sheet"

y(TM 1017-18, 1087). He had worked a full day in the shop

without incident, but the next morning an orficer confronted

2/ Citations to "TM" refer to the trial minutes submitted

— as Exhibit A on appeal.

3/ Exhibit E on appeal, which was Exhibit 14 at trial,

consists of the prison Daily Journal entries relating to

appellee Mosher. It contains all of the disciplinary

infractions that Mosher was charged with, and the

punishments meted out. It is also of interest as a

random sample of disciplinary actions taken at the prison,

since it includes actions taken with regard to other

prisoners as well.

4/ The safety sheet is Exhibit D on. appeal and was exhibit 11

at trial.

-2-

him with the sheet and told him to read and sign it (in

duplicate) and the officer would witness his signature (Id.).

The form states that a copy of the executed sheet will be

included in the prisoner's central file. Mosher read and

understood the safety rules listed on the sheet, and he was

ready and willing to work wherever assigned (TM 1071-72,

1019, 1061). He had previously worked for about three months

in the prison cotton shop, where inmates were not required

5/

to sign any such sheet (TM 1013). However, he felt that

the document could operate as a waiver of his right to relief

in case he were injured as a result of the State's negligence

in management of the shop (TM 1018-19, 1061, 1077, 1201).

The district court found as a fact that Mosher was sincere

in this belief and for that reason refused to sign the

6/

sheet. This resulted in a disciplinary charge against him.

5/ In civilian life Mosher was employed as a mechanic at a

switchboard manufacturing company, where he worked on

various machines and electrical equipment (TM 1008).

6/ Although the safety sheet (Exhibit D on appeal) does not

speak in explicit terms as a waiver, a layman might

reasonably have doubts about the legal consequences of

signing the form. Indeed, the attorneys and the trial

judge in this case were unsure of its effect (174a).

The requirement that the signature (in duplicate) be

witnessed by an officer indicates more formality than

reasonably associated with a simple list of safety rules.

Also, the fact that the sheet becomes a permanent part of

the prisoner's central file indicates that it might be

used for purposes other than merely informing the prisoner

of shop safety rules. Although the Warden testified that

no practical difficulties or undesirable consequences

would result from modifying the sheet clearly to indicate

that it does not constitute a waiver (TM 1518) , Mosher

was not given that option au the time but was required

to sign the sheet without alteration.

Mosher was summoned to a disciplinary "hearing"

before Deputy Warden DeLong. Although the only purpose of

the safety sheet is to assure that inmates know the snop

Vsafety rules (DeLong Dep. 35, 87; McMann Dep. 27-28),

DeLong would not allow Mosher to work without signing the

sheet and he summarily sentenced Mosher to punitive

segregation for an indefinite term (TM 1019-20, 1201).

DeLong1s position was that even where the prisoner had read

and understood the safety rules, and where he was ready and

willing to work wherever assigned, he must still sign the

form (DeLong Dep. 86, 88-89; TM 1200).

Although DeLong treated Mosher's refusal to sign

the safety sheet as a disciplinary matter requiring punitive

segregation, DeLong1s superior at the time, Warden McMann,

testified that refusal to sign the sheet would not call for

disciplinary action at all; a prisoner who refused to sign

would merely be assigned to the "idle" population, where he

would not work and earn industrial wages (McMann Dep. 28-29).

However, although McMann was warden when Mosher was sent to

segregation, he did not even know that DeLong had taken this

action (Id.)•

James V. Bennett, the former Director of the

Federal Bureau of Prisons, who testified as an expert for

7/ The designated depositions, introduced at trial, nave

been submitted as Exhibit B on appeal.

-4-

the prisoners in this case, stated that imposing punrtive

segregation on Mosher in these circumstances was

inappropriate as a matter of sound prison administration

(TM 243-47).

1. Punitive Segregation

As punishment for refusing to sign the safety

sheet, Mosher was confined to punitive segregation for about

five months in 1967; he was released to tne general population

on September 13, 1967 (TM 1031, 1202). On December 14, 1967,

without any intervening problems, Mosher was again reported

for refusing to sign the safety sheet and on December 18

was again sentenced to segregation for an indefinite term

(TM 1036-37). He was continuously confined in segregation

for a full year, until December, 1968. During that year,

he spent five months on "4 Section", uhe most severe kind

of punitive segregation (TM 1049), and for more than a month

his confinement was solitary, with no other inmates on tne

tier (TM 1087-88).

Punitive seareaation is the most severe punishment

8 /

meted out at the prison (McMann Dep. 24; DeLong Dep. 18):.

Nevertheless, at the time of Mosher's punisnment, ana at the

8/ Warden McMann testified that "of course, you could beat

a man with a club, you could hang him by his toes, but

that isn't done anymore, but I'd say [segregation] would

be the most serious punishment" (McMann Dep. 24).

-5-

time of trial of this case, the Department of Correction

did not provide any standards, substantive or procedural,

for the use of such segregation (McMann Dep. 19, 26, 47-48).

Although some of the more barbarous abuses found in the

Wright case had been terminated by the time of Mosher's

confinements in 1967 and 1968, conditions were still

extraordinarily severe. While inmates were normally given

underwear, beds, pillow, sheets ana blanket, these could oe

summarily taken away on the order of the deputy warden

(Belong Dep. 38-42, 48, 112; TM 1030-31, 1234). The deputy

warden had complete and unreviewable discretion to deprive

9/

an inmate of any or all of these basic amenities (id_. ) .

When an inmate was sent to punitive segregation,

his sentence was always indefinite, but he ordinarily spent

at least his first thirty days in "4 Section" (DeLong Dep. 20;

9/ Although Mosher's complaint is not based on squalid and

unsanitary conditions in segregation, it should be noted

that (a) segregation cells were not cleaned between

inhabitants (DeLong Dep. 69); (b) blankets and mattresses

were not changed between inhabitants (TM 174-75, 596;

Kennedy Dep. 20); (c) inmates were only allowed to shave

(with cold water) and shower very briefly once a week

(TM 1022-23, 354, 547-43); (d) toilets occasionally

became clogged, sinks were stained, rusty and dirty,

mattresses and blankets were stained and torn, floors

were dirty and nuisance insects were common (TM 491,

526, 544-45, 582, 610-11, 613-14, 652, 1537, 58-60, 128,

173-75, 1020-21, 1038, 1080); (e) inmates finding these

conditions upon being confined to a cell were not given

a broom, mop, plunger or other adequate means tor cleaning

up (TM 224/ 526 , 544-45, 582, 593, 653, 1021-22, 1170);

and (f) no segregation inmates had hot water, toilet

disinfectant or a comb and brush (TM 1021-22, 1239).

-6-

McMann Dep. 11; TM 1097, 1216). The cells on this tier were

physically no different from other segregation cells, except

that they had no light bulb or other artificial light of any

kind (TM 1081; Kennedy Dep. 18-19).

The living conditions of prisoners confined in

4 Section differed from conditions of life in the general

prison population in many respects:

(1) Prisoners spent 24 hours a day alone in their

small cells. They were not permitted any of the recreational

opportunities available to the general population; nor were

they even allowed to use the segregation exercise yard

(TM 1025, 196). Before June of 1968, 4 Section inmates were

not permitted to go to the small enclosed patio behind each

ceil (Kennedy Dep. 9; TM 62, 196, 546, 654, 1025, 1115).

They had no access to sunshine or fresh air. When the warden

discovered this practice during the pendency of this lawsuit,

he began allowing 4 Section prisoners to use the patio ror

an hour a day (Id.; TM 1475).

(2) The prisoners were barred from participation

in all rehabilitative programs and institutional activities,

including the opportunity to (a) work and earn money in the

industrial program (TM 1026-27, 198), (b) go to school and

participate in the educational program (Id.) and (c) attend

corporate religious services (Id.; TM 1027; McMann Dep. 41).

Moreover, they could not participate in any of the prison's

-7-

therapeutic programs (Id.; TM 1026-27, 1526-27). They could

not avail themselves of group counselling and they were not

visited by counsellors, psychologists, social workers or

psychiatrists (Id.; TM 207-8, 520, 1523; Freedman Dep. 6,

23 , 29, 44) .

(3) 4 Section prisoners were deprived of all

privileges enjoyed by the general inmate population,

including the following:

(a) 4 Section inmates were not permitted

to have their personal clothing but were issued

whatever clothing was available from the

segregation stock (TM 1024). They could not

have any of their personal belongings, inducing

personal toilet articles.

(b) They were not permitted to purchase

anything from the prison commissary except legal

materials; for example, they were not allowec to

buy or possess food to supplement their diet

(TM 1024-25, 197). They were prohibited from

receiving packages from home (TM 1242).

(c) They were not permitted to read

newspapers, watch television, listen to the

radio, or have movie privileges (TM 1025, 198;

Kennedy Dep. 18).

(d) Their correspondence was limited to

legal letters and one family letuer per week

-8-

(TM 1026, 197; DcLong Dep. 81). In addition

to the normal prison censorship, their mail was

read by segregation officers and personally by

the deputy warden (TM 1027; DeLong Dep. 78-79;

plaintiffs' Exhibit 18 at trial).

(e) They did not receive as much food as

prisoners in the general population (TM 199-200,

1028, 1240). They were not given fresh fruit

(TM 1029). They were sometimes put on short

rations as additional punishment (DeLong Dep.

107; TM 1235). The amount of food given a man

on short rations was determined by the deputy

warden, although by statute such rations were

supposed to be prescribed only by a physician

(compare former Correction Law Section 140 with

DeLong Dep. 52, 69, 106; TM 548-49, 1029; Peda

Dep. 11-12). In practice, short rations

consisted of half portions of segregation

servings (Kennedy Dep. 7). Appellee Mosher was

put on short rations even after Warden LaVallee

had ordered abandonment of that practice

(plaintiffs' Exhibit 42 at trial, pp. 77, 86).

(f) 4 Section inmates had no library

privileges except for legal materials (TM 1044),

and they were not allowed access to otner

reading material.

-9-

(g) 4 Section inmates were required to

stand at military attention at the bars of their

cells from 7:30 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. with lowered

eyes to show "respect" whenever any prison

employee was on that section (TM 1021, 69, 532,

597, 1234; DeLong Dep. 110, 133-34).

Inmates in punitive segregation but not in 4 Section

did not suffer all of the deprivations of 4 Section, but they

were still completely cut off from all normal prison activities

and programs, including the educational, vocational, religious

and therapeutic programs (DeLong Dep. 34; TM 1026-27, 1526-27).

The conditions imposed and privileges withheld in segregation

applied regardless of the individual inmate involved, his

background, or the disciplinary infraction he was charged

with (TM 1166, 1168, 1235-37, 1500-01). Appellee Mosher,

punished for refusing to sign a safety sheet, received the

same treatment as prisoners being punished for assault, theft,

escape, and other dangerous acts.

All inmates in segregation were barred rrom earning

statutory "good time" to reduce their term of imprisonment

(TM 1026, 1231; plaintiffs' Exhibit 10 at trial, pp. 4-5;

plaintiffs' Exhibit 12 at trial, p. 30). New York prison

inmates may, by law, earn good behavior time to advance their

eligibility for parole and reduce their sentence by one-third

(Id.; DeLong Dep. 17); but no "good time" may be earned while

-10-

the inmate is confined to segregation (Id.). Thus,

segregation operates to delay eligibility for parole and

prolongs the inmate's overall period of imprisonment

(TM 1214, 1231). The district court found that appellee

Mosher had lost 616 days of statutory good time because of

his confinements in punitive segregation, and ordered this

10/

amount restored to him (175a, 179-180a).

Unlike the prisoner in Sostre v. McGinnrs, ___

F.2d (2d Cir. 1971), Mosher was given no option to be

released from segregation by participating in group therapy

or agreeing to conform to prison rules. There was no group

therapy or similar program in Clinton Prison's segregation.

At one point, Mosher was told that he could get out of

segregation if thirty days passed without a disciplinary

10/ While in segregation, Mosher was charged with an array

of minor disciplinary infractions, including yelling to

fellow inmates (4 charges); "insolence" or loudness (5

charges); possession of "contraband" including innocent

items like tobacco, gum and fruit, possession of which

is not prohibited by any written rule (e.g. DeLong

Dep. 106), throwing four slices of bread out the window

and refusing to stand at military attention whenever any

prison employee passed (8 charges) (Exhibit E on appeal) .

As punishment for these alleged offenses, none or which

involved any violence or threat to the institution,

Mosher lost practically all of the few privileges

available in segregation, was put on short rations and

forfeited 350 days of earned good time (Id.; TM 1231).

For example, on one occasion he was punished for

possession of a banana, his first in a long time, which

he received from a friend (TM 1029-30); for this-, he lost

10 days of his liberty (Exhibit E, entry dated May 7,

1968). The district court found as a fact that these

minor violations were clearly linked to being wrongrully

confined in segregation and determined that Mosher was

entitled to restoration of all the good time he had lost

by- reason of segregation (174-175a).

-11-

offense, but was also informed by Deputy Warden DeLong that

in order to be released he would have to "crawl" (TM 10S8).

Mosher requested release in writing, but the deputy warden's

response was only "not this time," without any explanation

or indication of how Mosher might gain release by altering

his behavior (TM 1070; plaintiffs' Exhibit H on appeal).

Another request thirty days later received no reply at all,

despite the fact that Mosher had not been charged with any

more infractions in the interim (TM 1071).

When Mosher was punished, and at the time of trial,

there was no limit on the time a prisoner couid be held in

segregation, and he was not told how long he would spend

there (TM 122, 521-22, 1071, 1203, 1216; DeLong Dep. 20).

A prisoner could be held in segregation for a year, or two

years, or even for the duration of his sentence (DeLong

Dep. 165; McMann Dep. 26). There were no ascertainable

standards for determining the duration of confinement in

segregation (McMann Dep. 26; DeLong Dep. 160; LaVallee Dep.

31). This was completely within the discretion of the deputy

warden (DeLong Dep. 122, 160, 165; TM 520-21, 1071, 1133,

1299, 1473). Prisoners have in fact been confined to

4 Section of segregation for periods ranging up to two years

(TM 1328) . Doubtless because segregated inmates have none

of the outlets for relieving normal frustrations, confinement

to segregation tends to be self-perpetuating inmates

-12-

experience all or almost all of their disciplinary problems

while in segregation, and this affects the possibility of

release from segregation (TM 1068-69, 1497-99, 521, 548;

Exhibit E).

James V. Bennett, former Director of the Federal

Bureau of Prisons, testified as an expert that the duration

of segregated confinement should be carefully limited,

because prolonged segregation jeopardizes the well-being of

the inmate (TM 288; see also plaintiffs' Exhibits 28 and 30

at trial). At Alcatraz, which housed the federal system's

most recalcitrant prisoners (TM 313), punitive segregation

was not used for more than ten days; if results were not

forthcoming in that period, other techniques were tried

(TM 308-09, 313-14).

Dr. Joseph Satten, of the Menninger Foundation in

Topeka, Kansas, testified as a psychiatrist with extensive

experience in the corrections field that punitive segregation

can lead to mental illness in vulnerable individuals

(TM 425-27, 450). Even a period as short as three weeks

can break down a weak, disturbed individual, as many prisoners

with disciplinary problems are, and any individual can be

broken down by prolonged social isolation or segregation

(TM 427, 451). The expert testimony presented on behalf of

the prisoners stands uncontradicted in the record. Even the

prison officials recognized that any inmate may become more

-13-

suicidal or more violent because he is in segregation

(TM 1501, 1173). One official testified that regardless

of any trace of suicidal tendency in an inmate's background,

every initiate confined to 4 Section becomes a potential

suicide (TM 1169-70, 1173).

2. Disciplinary Procedures Leading To

Segregation Or Loss Of Good Time

The disciplinary procedures at Clinton Prison

afforded none of the safeguards normally comprehended by due

process. Although inmates were "charged" with "offenses,"

were required at "court" to "plead" guilty or not guilty,

and were "sentenced" to segregation or some other punishment

(e.g. TM 181-85), they were not provided with prior notice

of the charges, they were not permitted to confront or

cross-examine witnesses against them, they were not permitted

to call witnesses on their behalf, they were not permitted

the assistance of counsel or counsel substitute, there was

no adequate record of the proceedings and there was no formal

procedure for appeal from the decision (e.g. DeLong Dep.

15-16, 77-78, 96; TM 181-85). On many occasions, prisoners

were not permitted to explain their version of the events,

even where the facts were disputed (TM 120-22, 183, 561-62,

1052).

There were no recognizable standards for the

imposition of punitive segregation as a disciplinary

-14-

punishment (McMann Dep. 19, 26; DeLong Dep. 126, 154;

LaVallee Dep. 14). Segregation was imposed for a wide range

of offenses, seemingly without regard to their severity or

frequency (see Exhibit E; plaintiffs' Exhibit 15 at trial;

DeLong Dep. 113, 115-17). Although segregation was imposed

for very serious offenses, such as assault with a deadly

weapon (Exhibit E, entry dated March 28, 1967), it was also

imposed for minor offenses such as refusing to sign the

industrial safety sheet. Its imposition was also erratic.

The same day that Robert Mosher was sent to segregation

for refusing to sign the safety sheet, another inmate who

refused to work at all and who had more prior offenses than

Mosher merely lost his yard privileges for 15 days (Exhibit E,

entry dated March 28, 1967). The same day that Mosher was

charged the second time with refusing to sign the sheet,

another inmate who refused to work merely lost his commissary

privileges (Id., entry dated December 14, 1967). Inmates

were sent to segregation for conduct which did not violate

any written rule of the institution (TM 1222). Inmates

were not given notice of the kinds of conduct that risked

segregation as a punishment and prison officials did not

communicate this information to them; an inmate would not

know that his conduct would risk segregation until he was

so punished (DeLong Dep. 24-26; McMann Dep. 19-20; LaVallee

Dep. 18).

-15-

3. Psychiatric Observation Cells

In addition to being confined to segregation,

appellee Mosher was twice confined in a psychiatric

"observation" cell (TM 1031, 1053—56). Seven such cells

are located in the hospital wing of the prison (DeLong

Dep. 58, 60; TM 188). Their official purpose is to observe

mentally disturbed inmates and determine whether they are

psychotic (DeLong Dep. 62). In practice, however, the

observation cells were often used for disciplinary purposes

and some inmates were sent there not for psycniatric

observation but as disciplinary punishment (Freedman Dep.

11-13, 15, 18; Peda Dep. 26-28; TM 504-05, 511-12, 539-42,

554, 561; Exhibit F on appeal, para. 3). The disciplinary

inmates were not treated or diagnosed by.the prison

psychiatrist (Freedman Dep. 12, 15, 18, 20, 32; TM 507,

540-41).

11/ It appears likely that the observation cells had taken

the place of the "dark cells" previously used as

disciplinary punishment. The dark cells were located

in the segregation building. In them, inmates were held

in complete darkness behind a solid steel door; they were

completely naked; they had no furniture or furnishings

at all, no bed or blanket, and at least one of the cells

had neither a toilet or a sink; they received only a

diet of bread and water, with one meal every three days

(TM 1175-78, 1229-30, 1040; Kennedy Dep. 12-13; Peda

Dep. 17-18; DeLong Dep. 53-54). Although_Warden McMann

was not aware that the dark cells were being used

(continued on next page)

barbaric. There were no11/

The conditions in the observation cells were

furnishings in the cells, and

-16-

perhaps only a plastic mat to sleep on; two of the cells

had no toilet or sink at all; there was an artificial light,

but not controlled by the inmates; inmates were usually kept

completely naked; they were not given any of the rudiments

of personal hygiene — e.g. toothbrush, toothpaste, soap,

towel, toilet paper, etc.; the walls and door of the cells

were solid; and inmates were completely cut off from all

other inmates and all prison programs (TM 189, 190, 193, 195,

506, 511, 518, 540, 542, 554, 647, 1033-34, 1123; DeLong

Dep. 60-61; Freedman Dep. 7, 18-19, 21). One inmate was

held in an observation cell in these conditions for

disciplinary purposes for 65 days in 1968 (TM 504-513); he

was completely without clothing for nearly a month (TM 507).

There were no procedural or substantive safeguards governing

the use of the observation cells. The deputy warden, not

the psychiatrist, made the decision to confine a man to sucn

a cell (DeLong Dep. 56-57). Use of the observation cells

for disciplinary purposes was even more capricious than

segregation. No accusation of misconduct was a prerequisite

to their use and prisoners sent there did not even have the

summary "hearing" as for segregation.

11/ (continued)(McMann Dep. 13-14), his deputy wardens repeatedly placed

inmates in dark cells (see plaintiffs' Exhibits 38 and 39

at trial) ' (Cells 13 and 26 were the dark cells. TM 1393).

The doors were taken off the dark cells during pendency

of this action and only a few weeks before trial

(LaVallee Dep. 26; TM 519, 1040).

-17-

4. Prohibition Against Inmate Legal Assistance

Appellee Mosher was twice punished for infractions

of the prison policy prohibiting inmates from assisting each

other in the preparation of legal papers or giving legal

advice (TM 1044-45; Exhibit E on appeal, entries dated

July 21 and July 15, 1967). Despite the prohibition of

inmate legal assistance, the prison has not provided any

alternatives for legal assistance to prisoners (LaVallee Dep.

44-45; DeLong Dep. 93). Moreover, inmates have frequently

been subjected to ridicule and threats by officers concerning

their legal work and have been told that they have no rights

which the court will protect (TM 55, 117, 126, 150-60, 564,

646-47) .

5. Withholding And Censorship Of

Attorney-client Correspondence

On June 5, 1968, during the pendency of this action,

appellee Mosher wrote to the attorney who had been appointed

by the district court to represent him, describing conditions

in 4 Section and an incident involving the beating of a fellow

inmate (TM 1063; Exhibit G on appeal). The letter was

intercepted and was not permitted to leave the prison. Mosher

received a slip from a censoring officer stating thai_ the

letter "contains prison news which is untrue" (Id.). However,

the incident described by Mosher was testified to under oat..,

without contradiction, by the other prisoner at the trial oi

this action (TM 551-54; cf. Peda Dep. 19).

-18-

This interference with attorney-client communication

occurred pursuant to a prison policy requiring the censorship

of all outgoing and incoming correspondence, and a special

policy requiring that in addition to the usual censorship,

mail from segregation inmates may be read by segregation

officers and personally by the deputy warden (TM 1027;

DeLong Dep. 78-79; plaintiffs' Exhibit 18 at trial).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the extraordinary punishment of

appellee Mosher by prolonged punitive segregation and loss

of statutory "good time," without any justification in

light of the needs of prison security, was properly held

unconstitutional by the district court.

2. Whether the district court properly ordered

the restoration of Mosher's statutory good time lost by

reason of wrongful punishment.

3. Whether Mosher's extraordinary punishments

were imposed in violation of rudimentary procedural due

process and, if so, whether the safeguards ordered by the

court below were appropriate to protect appellee in future

such cases.

4. Whether the district court properly enjoined

use of psychiatric "observation" cells for disciplinary

-19-

purposes and required appropriate safeguards for their

future use.

5. In a case where prison officials intercepted

and withheld correspondence between Mosher and the attorney

appointed by the district court to represent him, on the

ground that such correspondence contained "prison news"

deemed "untrue" by the officials, whether the court below

properly enjoined censorship and interference with such

correspondence.

6. Whether the district court properly ordered

the prison officials to permit legal assistance among

prisoners, where the State provides no alternative means

of legal assistance to prisoners.

-20-

ARGUMENT

I. The District Court Properly Held That

Appellee Mosher Was Unconstitutionally Punished.

As this Court noted in Sostre v. McGinnis, ___

F.2d (2d Cir. 1971), "our constitutional scheme does not

contemplate that society may commit lawbreakers to the

capricious and arbitrary actions of prison officials" (slip

op. 1673). Accord, Landman v. Peyton, 370 F.2d 135, 141

(4th Cir. 1966). In other words, prison officials, like all

other administrative officials under our system, are

accountable to principles of law, and may not detrimentally

affect the lives of citizens by vindictive, standardless or

arbitrary action. If prisoners are entitled to any protection

at all against arbitrary and excessive punishment, the

district court's holding of unconstitutional punishment must

be affirmed.

In reviewing the holding of unconstitutional

punishment, the Court should consider (1) the extraordinarily

severe conditions of punitive segregation to which Mosher was

subjected, (2) the excessively long period of segregation,

(3) the loss of nearly two years of statutory "good time" and

(4) the lack of any legitimate penal justification for the

punishment.

-21-

(1) Extraordinarily Severe Conditions

of Punitive Segregation

No one can dispute the district court's finding

that appellee Mosher was kept in extremely severe conditions.

By its very nature, punitive segregation takes away the few

comforts and institutional privileges that can make prison

life tolerable for a flexible man. In segregation, the

prisoner is cut off from all normal prison activities and

12/

paces out monotonous days in his isolated cell.

In Sostre v. McGinnis, ___ F.2d ___ (2d Cir. 1971),

this Court stated that segregation is "onerous indeed"

(slip op. 1668). The Court pointed out, however, that there

were certain ameliorative conditions of punitive segregation

at Green Haven Prison that raised it "several notches above

those truly barbarous and inhumane conditions" held

12/ Moreover, the record in the present case is replete with

evidence of the petty tyranny that prevailed in punitive

segregation. While appellee Mosher himself was never

beaten, he knew of physical abuses testified to, largely

without contradiction, by other inmate witnesses. While

he was never teargassed, he was threatened with gas.

While he tried to "stand" at military attention with

humbly lowered eyes as long as he could, he at last

stopped and then was severely punished for failing to

show proper "respect". While he tried to keep his cell

clean, he experienced the same poor sanitary conditions

that were common in segregation. And, of course, he

was subjected to numerous "informal" punishments —

like the loss of sheets, bed, etc. -- meted out by the

deputy warden in his absolute discretion.

-22-

Amongunconstitutional in other cases (slip op. 1664).

the factors explicitly referred to by the Court were:

(1) the prisoner there "aggravated his isolation by refusing

to participate in a 'group therapy1 program offered each

inmate in segregation" (slip op. 1648, 1664), and thus

greatly prolonged the duration of his segregation; (2) the

prisoner in Sostre was permitted an hour of exercise a day

in an exercise yard "open to the sky" (Id. at 1649 , 1663-64) ;

(3) the prisoner enjoyed a diet consisting of 2800-3300

calories a day (Id.); and (4) the prisoner had "the constant

possibility of communication with other segregated prisoners"

(Id. at 1664).

None of these ameliorative conditions is present

in the instant case: There was no group therapy or similar

program offered to Mosher; when Mosner was on 4 Section,

prisoners were not permitted any exercise period at all, and

were never permitted any exercise in the open air; Mosher

was put on "short rations" for a period of five weeks, during

which time he did not receive the normal prison diet; and for

13/

13/ Cases holding conditions of punitive segregation or

solitary confinement to be unconstitutional include

Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519 (2d Cir. 1967); Hancock

v. Avery, 301 F.Supp. 786 (M.D. Tenn. 1969); Holt v.

Sarver, 300 F.Supp. 825 (E.D. Ark. 1969); Barnes v.

Hocker, No. R-2071 (D. Nev. Sept. 5, 1969); Jordan v.

Fitzharris, 257 F.Supp. 674 (N.D. Cal. 1966); cf. Brooks

v. Florida, 389 U.S. 413, 415 (1967); Anderson v. Nosser,

438 F.2d 183 (5th Cir. 1971).

-23-

at least a month Mosher was all alone on 4 Section, with no

14/

possibility of communication with any other prisoner.

Moreover, all parties here, including the prison

officials, agreed that the kind of segregation used at

Clinton Prison can be dangerous. James V. Bennett and

Dr. Joseph Satten testified for the prisoners that punitive

segregation is a potent weapon and may have disastrous

15/consequences. Dr. Satten testified that prolonged

segregation can cause mental illness and break down even

14/ The unnecessarily harsh nature of the conditions to

which Mosher was subjected is demonstrated by the new

regulations for segregated confinement that have been

adopted by the New York Department of Correction,

effective October 19, 1970. 7 N.Y.C.R.R. Part 300

et seq. The new regulations outlaw many of the

practices to which Mosher was subjected. The regulations

seem to accord with the standards for segregated

confinement in federal prisons. See Policy Statement

No. 7400.5, November 28, 1966 (plaintiffs' Exhibit 28

at trial). These provisions show that there was no

legitimate penal interest requiring the extraordinary

deprivations to which Mosher was subjected.

15/ It has long been recognized that solitary confinement

or segregation cannot be considered a mere regulation

as to the safe custody of prisoners, and that it can

cause mental illness, induce suicidal tendencies and

interfere with the possibility of rehabilitation.

See In re Medley, 134 U.S. 160, 167-68 (1890).

The American Correctional Association recognizes that

segregation can be both dangerous to the prisoner and

self-defeating in terms of improving discipline:

"Perhaps we have been too dependent on isolation or

solitary confinement as the principal method of handling

the violator of institutional rules. Isolation may

bring short-term conformity for some, but brings

increased disturbances and deeper grained hostility to

more." Manual of Correctional Standards, 413 (1966).

-24-

well adjusted individuals. The testimony by these eminent

authorities was not disputed by any prison authorities, who

acknowledged that prisoners at Clinton could become suicidal

or violent because of their confinement to segregation.

(2) Excessively Long Period of Segregation

In 1967, appellee Mosher was held in segregation

for five months. His second confinement, in 1963, lasted

an entire year, of which five months was spent in 4 Section,

the most severe kind of segregation. He spent over a month

alone on that tier, in true solitary confinement. Unlike

the prisoner in Sostre, he had no option to participate in

group therapy and thereby effect his early release.

This prolonged punishment vastly exceeds the

limits set by accepted prison authorities. James V. Bennett

testified that even at Alcatraz, punitive segregation was

never used for more than ten days. The Missouri prison

system also sets ten days as the upper limit (plaintiffs'

Exhibit 29 at trial, p. 7). The American Correctional

Association states that a few days of punitive segregation

is usually sufficient and that it should never exceed 30 days.

Manual of Correctional Standards, 418 (1966). The Model Penal

Code would allow segregation "for serious or flagrant breach

of the rules" for a period not exceeding 30 days. Proposed

official draft, Section 304.7(3) (1962). Indeed, the

excessive length of Mosher's segregation has now been

-25-

recognized by New York prison officials themselves, and

under their new regulations segregation is limited to 60

days. 7 N.Y.C.R.R. Section 253.5. The officials in this

case made no attempt to justify the excessive length of

16/

Mosher's segregation.

(3) Loss of "Good Time"

As a result of his confinement to segregation,

Robert Mosher lost 616 days of statutory "good time". This

has delayed his eligibility for parole and prolonged his

overall period of imprisonment. His confinement to

segregation resulted in effect in the same treatment

incarceration in a state prison for more than a year as

that accorded a man convicted of a felony. Yet this was

accomplished without judge, jury or any of the protections

17/

of the due process clause.

16/ James V. Bennett and Dr. Satten testified that where

prisoners do not respond quickly to segregation, other

techniques should be tried — more exposure to treatment

personnel, experimentation with privileges and incentives,

transfer to a different institution, etc. Prolonged

segregation is not only counter-productive, but tends to

embitter the inmate and diminish the likelihood of his

rehabilitation. Mindless prolongation of segregation

is gratuitously cruel unless the officials attempt to

get at the root of the inmate's problem and the reasons

for his behavior.

17/ The loss of good time and consequent deferral of parole

consideration alone persuaded the Seventh Circuit Court

of Appeals that a prisoner's complaint of arbitrary

disciplinary punishment must be heard. See United States

ex re1. Campbell v . Pate, 401 F.2d 55 (7th Cir. 1968);

see also, United States ex rel. Hancock v. Pate, 223

F.Supp. 202 (N.D. 111. 1963).

-26-

(4) Lack of Any Justification for the Punishment

Robert Mosher never assaulted anyone, or threatened

insurrection, or plotted escape, or endangered in any way

the security of the institution. He merely refused to sign

the industrial "safety sheet". Whether he was right or wrong

about its amounting to a waiver is beside the point, because

his sincerity was unquestioned and was accepted by the prison

officials and by the district court.

If, as the officials asserted, the safety sheet

was intended merely to assure that an inmate knows and

understands safety precautions, certainly refusal to sign

it creates no major disciplinary problem. Indeed, Warden

McMann testified that refusal to sign the sheet would not

call for disciplinary punishment at all; he would merely

assign the man to an "idle" company where he could not work

and earn prison wages. Although Warden McMann was in charge

of the institution both times when Mosher was sent to

segregation, he apparently did not know of these actions

w

taken by his deputy warden. Since the officials had no

objection to putting specific non-waiver language in the

safety sheet and since the sheet is not even required rn

many of the prison's shops, clearly it was inappropriate to

18/ As Judge Sobeloff stated in a similar context, "Where

the lack of effective supervisory procedures exposes men

to the capricious imposition of added punishment, due

process and Eighth Amendment questions inevitably arise."

Landman v. Peyton, 370 F.2d 135, 141 (4th Cir. 1966).

-27-

treat Mosher as though he had committed a major disciplinary

infraction. James V. Bennett testified that such action by

the deputy warden was inappropriate as a matter of prison

administration. In short, Mosher's punishment was not

justified by any legitimate penal consideration.

We do not question the right of prison officials

to segregate prisoners who in fact present a "credible threat

to prison security." Sostre v. McGinnis, ___ F.2d ___

(2d Cir. 1971) (slip op. 1665). We recognize that some form

of isolation may be needed to control prisoners who are

actually disruptive or who threaten disorder or violence.

However, appellants failed to offer any justification

whatever for the extrerae and extraordinary deprivations

visited on appellee Mosher. Let us be specific. Appellants

offered nothing at all, not even their own opinions, to show

that Mosher created any danger whatever to prison oraer.

Furthermore, they offered no evidence that alternative means

of either discipline or treatment would have been

19/ . ,ineffective. Even wher*e some showing of the neecs Oi

19/ The record does not show that the officials either tried

or considered the more humane methods of dealing with

difficult inmates suggested by appellee's expert

witnesses and the Manual of Correctional Stanoards.

Cf. Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571 (8th Cir. 1968),

holding unconstitutional the use of the strap as

disciplinary punishment. There, whipping was "the

primary disciplinary measure used" and the waraen made

a showing that facilities for alternative measures were

limited. Furthermore, the officials testified that

whipping was actually needed to preserve discipline and

(continued on next page)

-28-

prison discipline is made,

"acceptance of the fact that incarceration,

because of inherent administrative problems,

may necessitate the withdrawal of many

rights and privileges does not preclude

recognition by the courts of a duty to

protect the prisoner from unlawful and

onerous treatment of a nature that, of

itself, adds punitive measures to those

legally meted out by the court." Jackson

v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529, 532 (5th Cir. 1968).

We recognize that in light of this Court's decision

in Sostre v. McGinnis, the conditions of segregation to which

appellee Mosher was subjected may not, standing alone, be

20/

deemed by the Court to be unconstitutional punishment.

But considering all the circumstances, Mosher's punishment

was unconstitutional because it was unnecessarily cruel in

view of any proper purpose. It is well established that

"a punishment may be considered cruel and

unusual when, although applied in pursuit

of a legitimate penal aim, it goes beyond

19/ (continued)

that it was effective in meeting this need. One of

the important circumstances considered by the court

(Blackmun, J.) in striking down the practice as

unconstitutional, relying on the testimony of James V.

Bennett, was that the disciplinary measure involved

there "frustrates correctional and rehabilitative goals."

404 F .2d at 580. The court rejected the warden's

proffered justification (not even attempted in the

instant case) that "the state needs this tool for

disciplinary purposes and is too poor to provide other

accepted means of prisoner regulation." Id.

20/ The Court did note in Sostre that "In some instances,

depending on the conditions of the segregation, and

the mental and physical health of the inmate, five days

or even one day might prove to be constitutionally

intolerable" (slip op. 1663, n.23).

-29-

what is necessary to achieve that aim; that

is, when a punishment is unnecessarily cruel

in view of the purpose for which it is used."

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 370

(1910); Dearman v. Woodson, 429 F.2d 1288,

1290 (10th Cir. 1970); Hancock v. Avery,

301 F.Supp. 786, 791 (M.D. Tenn. 1969);

Jordan v. Fitzharris, 257 F.Supp. 674, 679

(N.D. Cal. 19 66)".

Here, of course, the punishment was not even arguably

justified by a legitimate penal aim, and there was no showing

that the gratuitous punishments visited on Mosher were

necessary to any penal interest.

Furthermore, the punishment imposed on Mosher was

wholly disproportionate to Mosher's conduct, which did not

violate any prison rule or present any "credible threat to

prison security." Sostre, supra, slip op. at 1665.

Accordingly, the district court properly held that the

punishment was unconstitutionally disproportionate. This

is in accord with the "precept of justice that punishment

for crime should be graduated and proportioned to offense."

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 367 (1910). Just as

James V. Bennett testified below that the theory of

rehabilitation as opposed to punishment in penology carries

over to a prison's disciplinary system (TM 243), so does the

precept of justice expressed in Weems. This has been

recognized in prisoners' rights decisions:

"A prisoner may not be unreasonably punished

for the infraction of a rule. A punishment

out of proportion to the violation may bring

it within the bar against unreasonable

punishments." Fulwood v. Clemmer, 206

F.Supp. 370, 379 (D. D.C. 1962).

-30-

1968); Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y.

1970) (Mansfield, J.); Holt v. Server, 309 F.Supp. 362

(E.D. Ark. 1970); Jordan v. Fitzharris, 257 F.Supp. 674,

679 (N.D. Cal. 1966); United States ex rel. Hancock v. Pate,

223 F.Supp. 202, 205 (N.D. 111. 1963); cf. Robinson v.

California, 370 U.S. 660, 676 (1962); Anderson v. Rosser,

438 F .2d 183, 193 (5th Cir. 1971).

In Sostre, this Court stressed the seriousness of

the charges against the prisoner there and expressly left

open the constitutionality of segregated confinement if

imposed for lesser offenses than those attributed to the

prisoner (slip op. 1665-66, n.28). The governing consideration

in Sostre and in the present case is whether the prisoner's

conduct poses a "credible threat to the security of the

21/

prison" (slip op. at 1665). Since appellee Mosher's

conduct posed no threat whatever to prison order, since the

warden did not consider his conduct a disciplinary matter at

See also Jackson v. Bishop, 404 F.2d 571, 577-78 (8th Cir.

21/ A similar approach has been taken by a number of federal

district courts. See, e.g., Dabney v. Cunningham, 317

F.Supp. 57 (E.D. Va. 1970) (prisoner ordered released

from punitive segregation because the officials made no

showing of a factual basis to justify such confinement);

Smoake v. Fritz, F.Supp. , No. 70 Civ. 5103

(S.D. N.Y. 1970); Carter v. McGinnis, 320 F.Supp. 1092,

1097 (W.D. N.Y. 19701 (segregation justified only "if

substantial evidence indicates a danger to the security

of the inmates or the facility"); Davis v. Lindsay,

321 F.Supp. 1134 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) (no proof of actual

threats of either disruption or danger to the prisoner

or to other prisoners).

-31-

all, since Mr. Bennett's testimony established that his

punishment was completely inappropriate as a matter of prison

administration, and since the punishment was so vastly

excessive, the district court was plainly correct in holding

the punishment unconstitutional. A contrary determination

would sanction mindless arbitrariness and arrogant use of

power by prison officials, a position totally alien to our

22/

system of law. In the present case, the record reveals

an intolerable abuse of power by lower level prison officials.

Although in light of reforms made during the pendency of this /

suit it may be unlikely to be repeated, clearly the district

court was correct in its finding of unconstitutional

punishment.

22/ Ours is a "government of laws, not of men", Marbury v.

— Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 163 (1803). "Arbitrary power,

enforcing its edicts to the injury of the persons and

property of its subjects, is not law, whether manifested

as the decree of a personal monarch or of an impersonal

multitude." Hurtado v. California, 110 U.S. 516, 535-36

(1884). See also Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356,

6 S. Ct. 1064, 1071 (1886') . As this Court said in

another context, "The existence of an absolute and

uncontrolled discretion in an agency of government. . .

would be an intolerable invitation to abuse." Holmes

v. New York Housing Authority, 398 F.2d 262, 265

(2d Cir. 196 8)'.

-32-

II. The District Court Properly Ordered The

Restoration Of Mosher's Statutory Good Time

Lost By Reason Of Wrongful Punishment.

Appellee Mosher did not seek money damages in the

district court. He did seek, by way of relief, restoration Oi

the statutory "good time" lost by reason of his confinement to

segregation. Having found that Mosher was unconstitutionally

punished, the district court ordered as a remedy that such

good time be restored to him. This was both necessary and

appropriate as a matter of equitable relief. Indeed, this

Court's decision in Sostre v. McGinnis is dispositive here.

In Sostre, the Court squarely held that since the prisoner

was unlawfully confined to punitive segregation, the good

time he lost must be restored to him. Said the Court:

"Sostre may not be penalized because of his time in

segregation by remaining incarcerated longer or by becoming

eligible for parole later than he otherwise would" (slip op.

23/

1686). See also Ayers v. Ciccone, 303 F.Supp. 367

23/ The Court rejected the speculation that the prisoner

might not have earned good time credit if he had -remained

in the general population, stating that since his

constitutional.rights had been violated, any doubt would

be resolved in his favor and noting that "this is the

only feasible way to ensure that Sostre is not again

unlawfully penalized by arbitrary action" (slip op. 1686).

Even if the Court were reluctant to hold that Mosher's

punishment was wrongful at the time it was imposed, it

is now clear that the punishment was completely

inappropriate, as established by the testimony of Warden

McMann and Mr. Bennett. Accordingly, there is no reason

to continue the punishment by withholding the good time

lost by Mosher and thereby prolonging his period of

imprisonment.

-33-

(W.D. Mo. 1969), aff'd, 431 F.2d 724 (8th Cir. 1970). In

Ayers, the court held that disciplinary punishments imposed

for activities found to be protected by the Supreme Court's

decision in Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969), specifically

including the deprivation of "good time," were unconstitutional.

The court ordered the prisoner's good time restored. Accord,

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970)

(Mansfield, J.); cf_. United States ex rel. Campbell v. Pate,

401 F.2d 55 (7th Cir. 1968).

This case does not, of course, present any question

of exhaustion of state remedies pursuant to the federal

habeas corpus statute, 28 U.S.C. Section 2254. This case,

like Sostre, was brought as a civil rights action under

42 U.S.C. Section 1983. In Sostre, this Court left open the

question "whether a claim for relief grounded solely on the

contention that good time credit was unconstitutionally

withheld or forfeited would, standing alone, support an action

under 42 U.S.C. Section 1983" without exhaustion of state

remedies (slip op. 1686, n.50). The Court was apparently

concerned about using Section 1983 to effect release from

state custody and circumventing the exhaustion requirement

of the habeas statute.

The present case clearly is not grounded "solely"

or even primarily on the deprivation of good time, but seeks

injunctive relief from a number of unconstitutional practices.

-34-

Moreover, the restoration of Mosher's good time would not

result in his release from custody, because he has many

years of his long sentence yet to serve. Accordingly, this

case is not governed by the decisions in Katzoff v. McGinnis,

441 F.2d 558 (2d Cir. 1971), and Rodriguez v. McGinnis, ___

F.2d ___, No. 34567 (2d Cir. 1971). In Katzoff and Rodriguez,

panels of this Court held that since restoration of good

time would result in immediate release from custody, the

prisoner must exhaust state remedies before bringing a

federal suit under Section 1983. The reasoning was that

otherwise the exhaustion requirement of the habeas statute

would be circumvented. No such consideration is present in

24/

this case.

24/ While it is true that release from custody is more

commonly associated with habeas corpus than with a

civil rights action, the mere possibility of release

if a prison administrative decision is held

unconstitutional does not implicate the habeas policy

considerations of federal non-interference with state

judicial decisions and criminal convictions. If the

administrative decision was wrongful under the federal

Constitution, but holding it so would upset neither a

criminal conviction nor a state judicial decision, no

purpose is served by requiring the prisoner to exhaust

whatever remedy might be theoretically available under

state law. Cf. Houghton v. Shafer, 392 U.S. 639 (1968) ;

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (i961) ; Moreno v. Ker.ckel,

431 F.2d 1299 (5th Cir. 1970); Wright v. McMann, 387

F.2d 519, 524 (2d Cir. 1967); Rivers v. Royster, 360

F .2d 592, 594 (4th Cir. 1966); Edwards v. Schmidt, 321

F.Supp. 68 (W.D. Wis. 1971); Carothers v. Follette,

314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970)(Mansfield, J.);

Hancock v. Avery, 301 F.Supp. 786 (M.D. Tenn. 1969).

-35-

III. Mosher's Extraordinary Punishments Were Imposed

In Violation Of Rudimentary Procedural Due Process.

This Court should conclude, as did the district

court, that the extraordinary punishment of appellee ivlosher

was not constitutionally justified and for that reason his

good time should be restored. As a separate and independent

ground for relief, the district court found that adequate

procedural safeguards "might have averted or corrected this

improper punishment" and held that the punishment had been

imposed in violation of procedural due process (174a).

Accord, Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y.

2_5_7

1970) .

In Sostre v. McGinnis, this Court reversed a

holding that enumerated "trial-type" protections were

constitutionally mandated in "every" prison disciplinary

proceeding. The Court nevertheless acknowledged that a

prisoner facing a serious sanction is entitled to some due

process and stated that in disciplinary proceedings the

facts should be "rationally determined" and the prisoner

should be given "adequate notice," an opportunity to reply

25/ "We believe that such serious punishments should not

be allowed to stand, at least until disciplinary

procedures are adopted that will meet rudimentary

standards of due process under the conditions

encountered. A proceeding pursuant to sucn standards

may then well result in a much lighter.punishment

than segregation." 314 F.Supp. at 1029 (Mansfield, J.).

-36-

to the charge and a "reasonable investigation into the

26/

relevant facts" (slip op. 1673, 1683).

In the present case, the standards of Sostre were

not met. Appellee Mosher was not given adequate notice of

the charge against him. There was no prior notice, either

in writing or oral, that his conduct would be deemed a

disciplinary violation or that segregation and loss of good

time might be consequences flowing therefrom. Indeed, the

conduct for which he was punished did not violate any

specific prison rule. Moreover, the disciplinary procedures

at Clinton did not require that the accused prisoner be

given any advance notice of a disciplinary hearing.

Furthermore, it can in no way be said that the

facts were "rationally determined" by the deputy warden or

that there was any "reasonable investigation into the

relevant facts." The deputy warden refused to inquire into

Mosher's reason for failing to sign the industrial "safety

sheet"; he obdurately insisted that the sheet be signed

regardless of the fact that Mosher was ready ana willing to

work wherever assigned and the crucial fact that he in good

faith believed that he was being forced to waive his legal

rights in case of injury on the job.

26/ Judge Waterman, concurring, noted that "decision as to

what are wholly acceptable minimum standards is left

for another day through case-by-case development"

(slip op. 1690, n.2).

-37-

It is apparent that the deputy warden and Mosher

were at loggerheads and could not communicate about what was

really at stake. The deputy warden probably thought Mosher

was refusing to work and apparently never inquired whether

Mosher was actually willing to work wherever assigned. On

the other hand, Mosher thought he was being forced to sign

a document that might forfeit an important legal right, but

he was unable to communicate this to the deputy warden.

What was needed was the intercession of someone who could

bring to light the actual positions of the administration

and the prisoner and dispel the misunderstandings. What was

needed, in order to protect against the grossly unfair

punishment that resulted from the "hearing", was a person

to represent Mosher and assure a "reasonable investigation

into the relevant facts," so that the matter could be

"rationally determined." In short, Mosher needed counsel.

We recognize that in Sostre the Court disapproved

a requirement that prisoners be afforded a right to counsel

where serious punishment might be imposed. However, we do

not read the Court's opinion in Sostre to preclude a district

court from holding, in a proper case, that some kind of

27/

counselling or representation is required. We understand

27/ The Fourth Circuit has recently held, in an analogous

context, that whether counsel is required in parole

revocation hearings should be determined on a case-by

case basis; counsel may be mandated in some but not all

cases. See Bearden v. South Carolina, __ F .2d ___

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2231 (4th Cir. June 10, 1971).

38-

the Court's reasoning that disciplinary proceedings do not

require, for example, that points be preserved for appeal.

But there are other important functions of counsel, quire

apart from whether the proceedings may be viewed as

"adversarial". Not only can counsel bring out the

"occurrence or nonoccurrence" of the relevant facts, but he

can investigate all the circumstances and suggest

"alternatives less severe" than the most serious measure in

the prison's range of disciplinary controls. Cf. Bay v.

Connecticut State Board of Parole, F.2d , 39 U.S.L.W.

287

2695 (2d Cir. May 17, 1971).

We do not contend that Mosher had a constitutional

29/

right to an attorney. In this case, and in most cases,

28/ In both United States v. Wade, 383 U.S. 218, 238 (1967),

and Mempa v. Rhay, 389 U.S. 128 (1967), the Supreme

Court held that the presence of counsel was required,

even though neither line-ups nor sentencings are

"adversarial".

29/ However, in disciplinary cases where the prisoner is

charged with conduct constituting a crime, Miranda v.

Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) requires that the prisoner

either be afforded an attorney or not be disciplined^

The Attorney General of New York has rendered an opinion

stating that Miranda applies to prison disciplinary

proceedings and that the warnings required by that

decision must be given. Atty. Gen. Op. 409/70, Feb. 11,

1971; 8 Cr. L. Rptr. 2486. See also People v. Dorado,

62 Cal.2d 338, 42 Cal. Rptr. 169 (1965). A federal

district court recently held that unless an attorney is

provided for the disciplinary hearing, the prisoner may

not be disciplined, because he would be "stripped of

any possible means of defense." Clutchette v. Procur.ier,

F.Supp. , No. C-70 2497 AJZ (N.D. Cal. June 21,

1971).

-39-

the "appropriate representation" required by the court

below can be supplied by the procedures outlined in the new

New York regulations described in appellants' brief at

pages 38-43. Under such procedures, a prison employee is

designated to assist the accused prisoner in preparing his

case (7 N.Y.C.R.R. Section 253.3). The employee ascertains

the facts, investigates any reasonable factual claim made

by the inmate and makes a written report of his investigation

(brief for appellants, p. 41). We believe that the employee

must also be present at the disciplinary hearing to provide

representation there, and this would not seem to conrlict

30/

with the new regulations. In the present case,

representation of this kind would likely have completely

avoided the grave consequences,suffered by Mosher as a

result of the hasty encounter with the deputy warden.

The reality must be recognized that certain

disciplinary proceedings, like the ones here, involve such

"grievous loss" for the accused prisoner that rudimentary

due process is required. Cf. Goldberg v. Kelly, 337 U.3.

254 (1970); Escalera v. New York City Housing Authority,

30/ The presence of the representative at the hearing is

obviously essential where the accused inmate is

illiterate, inarticulate or inexpert in English.

-40-

Although, lesser punishments425 F.2d 853 (2d Cir. 1970).

may not require elaborate procedures, imposition of punitive

segregation or loss of good time is sufficiently serious to

require protection against error or arbitrariness in the

32/

fact-finding process. As the district court said in this

case, the Clinton Prison proceedings were "practically

judicial," and the consequences radically altered the status

of Mosher's imprisonment. In these circumstances, minimal

procedural safeguards — appropriate to the proceeding

were essential.

"The necessity of procedural safeguards should

not be viewed as antithetical to the treatment concerns of

corrections." President's Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, Task. Force Report, Correc ̂ ions, 13

31/

31/ See Clutchette v. Procunier,___F.Supp. ____,

No. C-7 0 2497 AJZ (N.D. Cal'. June 21, 1971) , where

Judge Zirpoli's exhaustive opinion adopts the Goldberg

approach for disciplinary proceedings in a California

prison. See also, Bundy v. Cannon, ___ F.Supp. ___,

9 Cr. L. Rptr. 2254 (D. Md. May 26, 1971); Meola v.

Fitzpatrick, 322 F.Supp. 878 (D. Mass. 1971); Carothers

v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970) (Mansfield,

J.); cf. Jones v. Robinson, 440 F .2d 249 (D.C. Cir. 1971);

Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1970); Morris

v. Travisono, 310 F.Supp. 857 (D. R.I. 1970).

32/ See generally, counsel's article on this and other

issues in this case, in Turner, Establishing the Rule

of Law in Prisons, 23 Stan. L. Rev. 473, 496-501 (1971).

-41-

(1967). James V. Bennett testified in this case that

the Clinton Prison procedures used to punish Mosher were

not proper from the point of view of sound prison

34/

administration (TM 272-73).

Having found, properly we submit, that rudimentary

due process had been violated in Mosher's case, the district

court ordered that before the prison officials could again

confine Mosher to punitive segregation or subject him to

the loss of good time credit, they must afford him minimal

due process protections (17o-79a). Since the entry of the

district court's decree, the New York Department of

Correction has promulgated new procedural regulations for

disciplinary proceedings (appellants' brief, pp. o9-42).