Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Order on Plan of Desegregation

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education Order on Plan of Desegregation, 1966. 814c3b23-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/13f485c9-6081-4040-9406-c07eefbd15da/stell-v-savannah-chatham-county-board-of-education-order-on-plan-of-desegregation. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

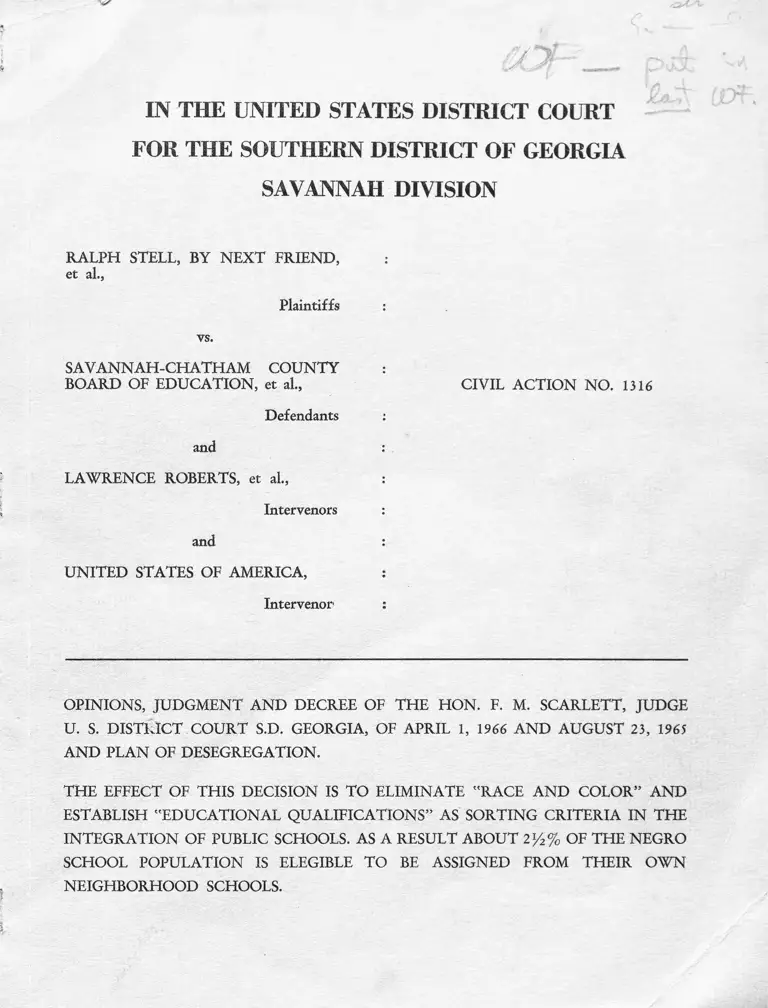

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SAVANNAH DIVISION

RALPH STELL, BY N E X T FRIEND,

et al.,

Plaintiffs

vs.

S A V A N N A H -C H A T H A M C O U N T Y :

BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al., CIVIL ACTION NO. 1316

Defendants

and

LAW REN CE ROBERTS, et al.,

and

Intervenors

U N ITED STATES OF AM ERICA,

Intervenor

OPINIONS, JUDGMENT AND DECREE OF THE HON. F. M. SCARLETT, JUDGE

U. S. DISTRICT COURT S.D. GEORGIA, OF APRIL 1, 1966 AND AUGUST 23, 1965

AND PLAN OF DESEGREGATION.

THE EFFECT OF THIS DECISION IS TO ELIMINATE "RACE AND COLOR” AND

ESTABLISH "EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS” AS SORTING CRITERIA IN TFIE

INTEGRATION OF PUBLIC SCHOOLS. AS A RESULT ABOUT iy2% OF THE NEGRO

SCHOOL POPULATION IS ELEGIBLE TO BE ASSIGNED FROM THEIR OWN

NEIGHBORHOOD SCHOOLS.

Paragraph 14 of the Plan of Desegregation promulgated by

Judge Scarlett provides that, T,no student shall have the right

to be assigned or transferred /out of his neighborhood/ to any

school or class the mean I.Q. of which exceeds the I.Q. of the

student” .

According to the undisputed evidence, paragraph 14 of the

Desegregation Plan promulgated by Judge Scarlett will limit the

assignment or transfer of Negro children in Savannah to schools

out of their own neighborhoods to about 2.7% of the Negro school

population, solely because of their low I.Q. or their low

"educational qualifications" (to use the words of the Supreme

Court in Brown), and not on account of race or color.

The undisputed evidence proved also without dispute or

explanation that Negro applicants for teaching positions in

Savannah are required to have a minimum score of only 400 on

the National teachers examination in order to be employed,

while White applicants must score a minimum of 500. It was

also proved without dispute or explanation that "the mean

yearly salary of Negro teachers markedly exceeded that of

White teachers". Such discrimination against White teachers

and intelligent children was stricken down by this decision.

The decision of August 23, 1965, upon which that of April

1, 1966, was based, and Desegregation Plan are also bound

herewith.

The foregoing summary is not a part of the official decision

by Judge Scarlett,

IH THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

RALPH STELL,

«t *1.,

SAVANNAH DIVISION

BT NEXT FRIEND,

Plaintiffs

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

FILED IN OFFICE

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _M„

APR 1 1966 — i9___

A/ -

Deputy Clerk

v s.

SAVANNAH-CHATHAM COUNTY BOARD

OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants

and

LAWRENCE ROBERTS, et al.,

Interveners

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Interveners

CIVIL ACTION NO. 1316

ORDER ON PLAN OF DESEGREGATION

FINDINGS OF FACT

(1) This action was commenced in January, 1962

(2) The plaintiffe are Negro school children attending the

Savannah-Chath&m County schools suing by next friend on behalf

of themselves and others®

(3) The defendants are the Board of Education for the City

of Savannah and County of Chatham, its members and officers, and

the Superintendent of Schools of Chatham County.

(4) The defendant interveners, Roberts, et al., are White

school children suing by their parents and next friend in their

own behalf and on behalf of other White children similarly

situated.

(5) This case wms tried on its merits in June, 1963, and

a decision rendered ©n June 28, 1963. (See 220 F.Supp. 667.)

(6) On August 23? 1965, this Court, after hearing, entered

an order on a plan of desegregation submitted by the defendant

Board of Education which, for the reasons stated in the opinion

of the Court of that date, was disapproved and disallowed.

(Raee Relations Law Reporter. Volume 10, Number 3, Fall, 1965,

page 1044). The parties wer® then ordered to prepare and submit

a plan of desegregation consistent with such order,

(7) On November 3, 1965, another hearing was held at which

a revised plan ©f desegregation approved by counsel for defendant

Board of Education and counsel for the White interveners was

submitted to the Court. At said time counsel for plaintiffs

requested additional time to study the proposed plan and to file

objections thereto if desired. Said request was granted.

» 2 ~

(8) Counsel for the plaintiffs thereafter filed no

objection to the plan submitted on November 3rd. However, on

November 12, 1965, Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, Attorney General

of the United States, moved to intervene in the case. Said

intervention was allowed without objection. The motion to

intervene was accompanied by objections to the plan for deseg

regation presented to the Court on November 3rd.

(9) After said objections became a part of the record,

the plan submitted on November 3rd was withdrawn, revised and

resubmitted to the Court. No formal objection to the revised

plan has been filed. The objections to the plan of November

3rd filed by the Attorney General in behalf of the Justice

Department were:

1. The plan fails t© eliminate the effect

©f past racial assignments.

2. The plan fails to provide for the

assignment of students entering the first,

seventh, and tenth grades without regard to

race.

3. The plan fails to provide for the non-

racial assignment of students who newly move

to Chatham County or who move from one district

to another within the system.

4. The plan fails to provide for the

desegregation ©f all 12 grades hy September

of 1966.

- 3 -

5. The plan fails to provide for the

desegregation and non-discriminatory hiring,

placing and retention of faculties and

administrative personnel.

6. The plan fails to provide for

transportation, facilities, and opportunity

for activities, without regard to race.

7. The plan fails to provide for

notice to individual parents, in simple

and clear language, of the rights and pro

cedures available tinder the plan.

(10) Apparently in response to objections 2, 3 and 4* the

revised plan completely eliminates race and color as determining

factors in the plan of desegregation and paragraph 12 requires

the desegregation of all school grades by September, 1966.

(11) The revised plan provided for the non-discriminatory

paying and retention of faculties but made no provision for

non-discriminatory hiring, which will be dealt with hereafter.

(12) In order to meet the seventh objection by the Justice

Department, the proposed plan was revised so as to require

publication of it in a newspaper of general circulation in

Chatham County, Georgia, within thirty days and thereafter at

least once each year.

(13) The Justice Department thereafter gave notice of the

taking of depositions of ten witnesses at the Office of the

4 -

Board of Education in Savannah on December 22, 1965, for use at

the hearing before the Court in Brunswick on December 27th (later

continued by consent of parties to December 29th). At the

hearing on December 29th in Brunswick, the following stipulation

was entered into in open court:

nAll parties agree that there shall be

submitted to Honorable F. M. Scarlett, United

States District Judge, the following questions

for determination in the above stated case:

1. The admissibility, particularly with

reference to Rule 26, of the depositions taken

in Savannah, Georgia on December 22, 1965, upon

notice by the Government and the Exhibits

referred to therein and if such depositions

are admitted then the questions as to relevancy

and materiality thereof;

2. All Motions pending in the above stated

case, including the motion filed by Plaintiff

to Dismiss the Defendants Intervenor as parties,

if such motion is still pending;

3. The approval of a plan for desegregation.

It is further agreed that briefs shall be

filed and served upon opposing Counsel not later

than January 20, 1966 and any reply briefs shall

be filed and served not later than January 31,

1966. "

- 5“

(14) Said stipulation was not made a formal order of Court

at that time but was subsequently approved and sanctioned by the

Court in order that the record might be brought to a close in

an orderly manner within time limits fixed by the Court* Within

the time allowed under the order of Court the Justice Department

filed with the Court a proposed plan for desegregation. The

Board of Education submitted the same plan as that disallowed

by the Court in its order of August 23rd. lo plan of desegre

gation has been submitted by the plaintiffs at anytime since

the pendency of this litigation.

(15) In addition to the testimony by depositions, Dr. Thord

M. Marshal, Superintendent of the Savannah-Chatham County Schools,

testified in person at the hearing in Brunswick. He testified

in effect that under the policy followed in Savannah White

applicants for teaching positions in Savannah were required to

have a minimum score of 500 on the National Teachers Examination

before they could be employed, but that a minimum score of only

400 is required of Negro applicants. No attempt was made to

explain the discrimination in favor of Negroes over Whites in

the employment practices of the Board. This undisputed evidence

of discrimination against White applicants for teaching positions

in Savannah has peculiar significance in view of the undisputed

facts developed in this case prior to the Court’s ruling of

August 23, 1965, to the effect that after employment, nthe mean

yearly salary of Negro teachers markedly exceeded that of the

- 6-

whit® teachers”, and that "Negro principals assigned relatively

lower competence ratings to the Negro teachers under their

supervision than the White principals assigned to the White

teachers under their supervision".

(16) The defendant Board of Education has given no indication

to the Court that it intends to cease discriminating against

White applicants and teachers in favor of Negro applicants and

teachers. Since its entry into this case the United States

Government has shown not the slightest concern over such

discrimination.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

The above stipulation delineates the questions with which

the Court is now concerned.

(1) Since the Justice Department of the United States

Government did not intervene in this case until November 12,

1965* it has no standing to question any actions or rulings in

the case prior to said date. It is the rule, applicable alike

to all parties, that:

"One who intervenes in a suit in equity

thereby becomes a party to the suit and

is bound by all prior orders and adjudi

cations of fact and law as though he had

been a party from commencement of suit."

Galbreath v. Metropolitan Trust Co. of

- 7-

California, et al.. 134 F.2d 569, and

cases cited.

(2) In the decision of August 23, 1965, disapproving and

disallowing the plan of desegregation submitted by the defendant

Board of Education, it was pointed out that there was "no

indication that integration is to be accomplished in any other

manner than congregating children because of race and color."

It was also pointed out that all of the evidence adduced in

the case at the trial on the merits was undisputed to the effect

that school children cannot be successfully educated under

conditions of massive integration without respect to age,

mental qualifications, learning capacity, educability and

intelligence in general. This Court then construed the law

as interpreted by the higher courts to mean that "separation

may not be accomplished by using race and color as sorting

criteria" but that age, mental qualifications, capacity to

learn, educability and intelligence in general are valid

sorting criteria, and that under the evidence the school

children of Savannah may and should be so classified in order

to provide the best possible education for all school children

with the largest possible benefit and the least possible

detriment to all. Since the order of August 23rd is binding

upon all parties in this case, and this order merely supplements

it, a copy is attached hereto for convenience.

(3) The first numbered paragraph of the above-quoted

stipulation raises a question as to the admissibility of the

-a-

depositions taken by the United States Government in Savannah on

December 22, 1965, for use at the hearing in Brunswick less than

100 miles away. The objection was as to the admissibility,

particularly with reference to Rule 26 of the Rules of Civil

Procedure. If admissible under that Rule, then objections were

as to the relevancy and materiality thereof.

Under Rule 26(d)(3):

"The deposition of a witness, whether or

not a party, may be used by any party for

any purpose if the court finds: - - -

2, that the witness is at a greater dis

tance than 100 miles from the place of

trial or hearing - -- ".

The Justice Department insists that such depositions are

admissible under the specific language of Rule 26(d)(2) which

provides that:

"The deposition of a party or of any one

who at the time of taking the deposition

was an officer, director, or managing agent

of a public or private corporation - - -

which is a party may be used by an adverse

party for any purpose.”

As a basis for its contention the Justice Department claims

that each of the witnesses whose depositions were taken in Savannah

was a "managing agent” within the meaning of said Rule. If each

of such witnesses was a "managing agent", Rule 26(d)(2) is without

meaning and is useless, if not harmful.

- 9-

The Justice Department relied on the maritime case of Warren

v. United States, 1? F.R.D. 3^9 (S.B. N.I. 1955), to sustain its

position. The Warren case involved a naval officer who was held

to be a "managing agent" of the United States. A number of

decisions of federal courts hold that the master of a ship is

a "managing agent" within the meaning of Rule 26 and may be

examined as such. See Aston v. American Export Lines. Inc.. DC,

11 FRD 442; Curry v. States Marine Corporation of Delaware. DC,

16 FRD 376; Fay v. United States. DC, 22 FRD 2S.

The specific question was answered recently in the case of

Southern Pacific Company v. Duncan. 230 Or, 179, 366 P2d 733,

96 ALR2d 617, where the Oregon Supreme Court, quoting Judge

Weinfield of the Southern District of Hew Tork in Krauss y.

Erie R. Company, 16 FRD 126, 127, said:

"A managing agent, as distinguished from

one who is merely ’an employee* is a person

invested by the corporation with general

powers to exercise his judgment and discretion

in dealing with corporate matters; he does not

act ’in an inferior capacity’ under close

supervision or direction of ’superior

authority’."

The Court specifically answered the contention similar

to that of the Justice Department in this ease to the effect

that since a ship master is a "managing agent", an assistant to

a school master should likewise be considered a "managing agent",

saying:

- 10 -

nNo one can quarrel with this conclusion

of the federal courts /that a ship master

is a nmanaging agent// for* it is common

knowledge that a ship is a wanderer to

many ports of call and thus more often

than not is far from the direct control

and supervision of its owner. Under these

circumstances the master must be fully

authorized agent of the owner to meet

the unforeseen demands of a voyage.

United States v. The Malek Adhel, 2 How.

210, 43 US 210, 11 L.Ed 239; Piedmont &

George’s Creek Coal Go. v. Seaboard

Fisheries Go., 254 US 1, 41 S.Ct. 1,

65 L.Ed 97."

The Oregon court thereupon rejected the idea that an employee

of a railroad company in charge of a train is a "managing agent"

and declared that no analogy can be drawn between such cases and

maritime cases.

For one to be a "managing agent" within the meaning of Rule

26, the interest of the corporation should be so close to his own

and to his heart that he could be depended upon in all events to

carry out his employer’s directions.

To the effect that a mere employee is not a "managing agent"

within the meaning of the Rule that depositions may be used in a

- 11 -

case when the witness is less distant than 100 miles from the

place of hearing, see, for further authority, ALR2d 632, 634,

637; 23 AmJur2d, Section 241, page 627.

The Court knows of no exceptions to Rule 26 in favor of

the Government. This ruling as to the inadmissibility of the

depositions taken in Savannah makes it unnecessary to rule on

the materiality or relevancy of such testimony.

(4) Dr. Thord M. Marshal, Superintendent of Schools of

Savannah-Chatham County, testified in person at Brunswick at

the hearing. No question has arisen as to the inadmissibility

of the testimony of Dr. Marshal. He was a "managing agent" for

the School Board and his testimony would have been admissible

if taken by deposition. While on the witness stand in Brunswick

he was asked by counsel for the intervening White children if

he heard the testimony of Donald M. Gray which had been taken

by deposition (now ruled inadmissible) earlier in the month.

Dr. Marshal testified that he did hear that testimony and that

he heard Donald M. Gray, Director of Personnel, testify "that

in the employment of teachers a minimum grade of 400 is set for

Negro teachers, 400 on National Teachers Examination, and a

minimum grade for white teachers is set at 500". When asked

how long that policy had been in effect, Dr. Marshal said:

"I don’t know how long that has been

going on."

- 12 -

The fact that a White applicant must make 500 on a scale

of 1,000 in order to be employed in Savannah while a Negro

applicant is only required to score 400 on a scale of 1,000

was thus established without dispute, without explanation.

It is contended by the Justice Department that if the deposition

of Dr. Gray is excluded no evidence remains in the record as to

discriminatory hiring by the defendants. We do not agree. It

is rather strange that the Justice Department of the United

States Government should exert its powers in an effort to

conceal or suppress facts as to discrimination against White

people on account of their race and color.

(5) It has been suggested that since my decision of

August 23rd several decisions have been rendered by the Fifth

Circuit Court of Appeals and by the Supreme Court that should

result in a revision of that decision. The Court is unable

to agree with that contention. Among the cases lately decided

by the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit is Singleton vs.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, et al.. decided on

January 26, 1966. That case discusses several previous cases,

including Stell vs. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education,

333 F .2d 55, and Jackson Municipal Separate School District.

et al. vs. Evers, then pending before the Court of Appeals and

decided by the Court on the same day. Neither in those cases

or in any other case called to the attention of the Court has

the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, or any other court, questioned

- 13-

the findings of fact by this Court in Stell or the findings of

fact by Judge Mize in Evers.

In the Evers case (No. 21&51, decided January 26, 1966), the

Court, citing and following Cahn, A Dangerous Myth in the School

Segregation Cases, 30 N.Y.U.L.Rev. 150 (1955), held that the

contention that Brown was decided for sociological reasons

untested in a trial was a bewitching and bewildering "myth” and

that Brown, not having been decided on facts, may not be over

turned on a contrary factual showing. It should appear quite

plainly to anyone with common intelligence that nothing said by

this Court on August 23rd and nothing said by this Court now in

any way tends to overturn the Brown decision. What this Court

decided on August 23rd and what this Court reiterates now is

that, consistently with and in accordance with Brown and the

decision of the Court of Appeals in this case (333 F.2d 55, 61,

62), school children may be assigned to particular schools ,!on

a basis of intelligence, achievement or other aptitudes upon a

uniformly administered program” provided race is not a factor

in making the assignment.

In Brown it was clearly pointed out that only school

children of ”similar age” and the "same educational qualifi

cations" are entitled to be grouped together in schools under

the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. How may

the age and mental qualifications of a child be determined?

How may the intelligence, achievement or other aptitudes of

- 14-

a child be determined? Is not evidence necessary in order to make

these determinations? Certainly no such determinations can be

made fairly and honestly without considering evidence.

The burden of Mr. Cahn's thesis is that he and everyone else

knew about the cruelty of segregation and the fact that the Court

considered evidence in Brown was merely evidence of the merciful

heart of the Supreme Court Justices. He would have courts draw

upon their imagination for their facts.

Apparently Mr. Cahn was of the opinion that segregation

whether by reason of race or color or by reason of intelligence

and mental qualifications is "cruelty” as far as the least

intelligent are concerned. See Vol. 30, page 159 (January 1955).

Mr. Cahn pointed out that it is not necessary "to prove a fact

that most of mankind already acknowledges, - - -" and that an

attempt to prove such a fact is "a rather bizarre spectacle".

Mr. Cahn described the basic approach of social psychologists

(such as those cited in Brown) to the question of segregation as

"liberal and egalitarian" (p. 16?). Quite appropriately, he

cautions: (p. 166)

"It is predictable that lawyers and scientists

retained by adversary parties will endeavor

more aggressively to puncture any vulnerable

or extravagant claims. Judges may learn to

notice where objective science ends and advocacy

begins. At present, it is still possible for

- 1 5 -

the social psychologist to ’hoodwink a judge \

who is not over wise’ without intending to do

so; but successes of this kind are too costly

for science to desire them.”

In the New York University Law Review for January 1956, Mr.

Cahn seems to make apologies for much that he said in 1955. ho©

Volume 31, p. 182, et.seq. Commenting upon the use of social

psychology in law cases (p. 194), he leetured courts and cautioned

against the use of the kind of psychological testimony admitted

in the eases underlying Brown. He concluded his later article

saying:

"But there is no substitute for the

vigilant exercise of critical intelli

gence. Where public justice is concerned,

an educator has no more right to play the

dupe than the deceiver.”

If the words of Professor Cahn are to guide us, maybe we

should swallow all of them— but slowly to see how they taste.

To the e f f e c t that brown was decided on facta in the record-— not

on the imaga 1 nation of judges, see Taylor vs, Board af.,Educatign

of New Koehelle, 191 P .Supp. 181. (b.D. N.Y. 1961) ; Pahr and

Ojemarm, "The Use of Social and Behavioral Science Knowledge in

Law", 48 Iowa L.it. 59 (1962).

We adopt the l a s t quoted words of Professor Cahn: "there is

no s u b s t i t u t e for the vigilant exercise of critical intelligence”.

Where the j u s t i c e and particularly the welfare and education of

16-

children is concerned, a judge has no more right to play the dupe

that the deceiver.

As pointed out in my decision of August 23rd, a published

study entitled "Project Talent” (1963) was tendered and admitted

into evidence in this case. Since that Study investigated on

a national scale the same questions that were investigated by

the evidence in this case and in Evers and since that Study was

conducted in behalf of the Office of Education, U. S. Department

of Health, Education and Welfare, and since this Court has

declared that studies and findings made by the Office of Education

are entitled to great weight (see Singleton vs. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, No. 22527, decided January 26, 1966,

pp. 5 and 7), we feel justified in referring to it again. The

Study involved 773 public senior high schools in every section

of the United States involving some 500,000 students. That

Study found the facts to be almost exactly as found by this

Court in the trial on the merits and as found by Judge Mize in

Evers. It is, therefore, appropriate to refer to such Study in

more detail than was done in my decision of August 23, 1965.

"Project Talent” relates to the "educational achievement

of high school pupils in relation to percentage of Negroes in

school enrollment.” It was conducted by the Project Talent

Office of the University of Pittsburgh under the auspices of the

U. S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. George R.

Burket, who was in charge of the Study, is a nationally

- 17-

renowned authority in his field. He did not slant or color the

study so as to conform to any preconceived ideas or any national

policy. (A copy of it is now on file as a part of the record in

this case and is subject to inspection in the Office of the Clerk

of this Court.)

The purpose of one part of the survey was to display

"differences and similarities among schools having varying

proportions of Negro enrollment.”

The tests administered in the schools can be classified

as both aptitude and achievement tests. All of these tests are

highly related to school grades and hence are predictive of

school learning. Scores were not published for individual

White and Negro students. Scores were released, instead, for

classes having proportions of Negroes running from zero to 100

per cent. Intermediate steps are 1-9 per cent Negro, 10-19

per cent Negro, 20-29 per cent Negro, and 30-99 per cent Negro.

Thus, the zero classes are all-White. The 100 per cent

classes are all-Negro.

Tables incorporated in Project Talent are too voluminous

to be fully reproduced but essential trends can be summarized

as follows:

1) There is a strong tendency for average test scores to

decrease as the per cent of Negroes increases. The fall-off holds

for schools in the East, North and South and occurs in both

non-verbal (that is, abstract-reasoning) tests and in verbal

(that is, reading comprehension) tests. For instance, in the

-IS-

12th Grade classes of Southeastern States, results from 19 tests

show drops of from 20 per cent to SO per cent in average score

from zero per cent to 100 per cent Negro enrollment. That is,

the averages were 20 per cent to SO per cent below the averages

earned by all-White 12th Grade classes. The percentage decrease

was in ratio to Negroes enrolled, the more Negroes, the lower the

score.

In the mid-East, for the same tests, the drop is only

slightly less, from 16 per cent to 60 per cent in the averages.

2) Little difference in test scores was found between schools

in low-quality, medium-quality and high-quality housing areas.

In all-Negro schools, test means were actually higher in low-

quality housing than in medium and high-quality housing.

3) The larger the percent of Negroes in school, the higher

drop-out rate. Drop-out rates were lower in the Southeast than

in Eastern and Northern areas. (Note: The Southeast, the area

with the lowest percentage of drop-outs, it is worth noting,

historically has maintained segregated public-school systems.)

4) Absenteeism increased as the percentage of Negroes

increased; also per-pupil expenditure. It costs more to operate

an integrated school than a comparable segregated school.

To further summarize the "Project Talent" findings: Schools

integrated en masse in all areas of the United States evidence,

(a) lower academic performance, (b) more drop-outs, (c) greater

incidents of absenteeism, (d) higher costs, (e) fewer graduates

going to college, and (f) behavioral delinquency increased as

- 19-

the percentage of Negroes rises.

Without exception these unfavorable and unfortunate conse

quences occur in direct proportion to the number of Negroes

enrolled. It is apparent that this Study was originally

conceived and projected as "Project Talent" in the expectation

that it would vindicate the assumption of injury by segregation

and repudiate the assumption of injury by integration, as was

shown by proof in this case and in Evers. The honest, forthright

and objective findings disclosed by this Study involving a half

million high school students in nearly S00 high schools through

out the Nation are apparently the very reverse of that expected.

Why such a study should not receive wide publicity and renown

is mysterious. The Government that financed the Study has

apparently concealed it. It is now said to be "out of print".

An effective way to deal with stubborn or embarrassing facts is

to replace them with imaginary assumptions. To the equalitarian

all school children, all races and all men are equal and nothing

to the contrary may be considered. Nevertheless, the equalitarian

readily insists that the equalitarian holds first place among

equals while all others are on a lower level.

That which was predicted or found to be true in the trial

of this case and in the trial of the Evers case and that which

was found to be true by the United States Department of Health,

Education and Welfare in "Project Talent" is the same thing that

was found to be true in Washington, D.C. as a result of massive

- 20 -

integration. That fact was pointed out by a member of the Congress

in EverS. (232 F.Supp. 241, 245)

In an effort to soften the devastating effects of massive

integration, school authorities in Washington, D.C. and other

cities have adopted various devices designed to enable brighter

children to be classed with brighter children so that their

progress rate may not be seriously impaired. In Washington and

some other cities the "track system" of grouping children in

accordance with ability is now under violent attack from civil-

rights groups and the most sadistic equalitarians. The lead

editorial of the Wall Street Journal of December 27, 1965, tells

that story so well that the Court adopts it and makes it a part

of this opinion. It is as follows:

"A PREMIUM ON DULLNESS

In the schools of Washington, D.C., and some

other cities, the track system of grouping stu

dents according to ability is coming under

increasing attack from civil-rights groups.

The controversy strikes us as one more illus

tration of how snarled the whole theory of

equality can get in practice.

A track system usually embraces basic,

regular and honors classes or their equiv

alents, so that the better minds can advance

faster and confront a greater educational

challenge. In the nation’s capital, where

- 21 -

the school population is predominantly Negro,

the rights leaders charge that the set-up

cloaks anti-Negro discrimination in a garb

of academic respectability. Related ob

jections are that it is undemocratic and

develops snobbery.

Now there may well be grounds for justified

criticism of the track system as it has evolved

in Washington and elsewhere, but the argument

from discrimination is a remarkably poor one.

What the critics are saying, whether they

realize it or not, is that Negro children as

a group are slow learners. More broadly,

that all students should be taught on the

basis of the lowest common denominator.

The first thing to note about that

proposition is that it is anything but an

exercise in equality. By coincidence, the

current Columbia Teachers College Record

contains some useful thoughts on the subject

in the form of an article by Professor Paul

Nash of Boston University; it is concerned

not with the merits or demerits of any

particular track system but with the general

problem of equality in education.

- 22 -

TIf a slow child,’ writes Mr. Nash, ’is

given a program that fully stretches and

challenges him intellectually, and a bright

child is given the same program, which bores

and stupefies him, they do not enjoy equal

opportunities.’ In fact, no way of producing

equality is known if that term is taken to

imply that all children should somehow come

out of the educational process equal.

What, then, are attainable goals of

equality? Certainly equal access to the

schools to the extent feasible, and fair

treatment within them. Beyond that,

paradoxically enough, inequalities can be

reduced precisely by ’undemocratic’ methods

like grouping according to ability or

variable standards.

As Mr. Nash explains, ’we may demand

that an able student achieve a higher level

of work in order to pass than a less able

student. The passing grade really signifies

’performance in relation to ability’, and

the pass of the able student represents a

higher measure of achievement than the pass

of the less able student. We might defend

this by arguing that the same absolute standard

for all would mean that the weak students would

not enjoy equal opportunities because they would

be constantly penalized by failure•’

For our part, we doubt that furnishing

intellectual challenges to capable pupils

actually is undemocratic except in an unrealistic

sense, or that it makes many snobs; those it

does have that effect on would probably suffer

the same affliction anyway. Far more important

to recognize, it seems to us, is that several

other values besides equality are involved in

education and that sometimes they will be in

at least apparent conflict.

One is the principle, which we believe valid,

that the child should be permitted to absorb as

much learning as he is able to, and this

principle need not run counter to any reasonable

definition of equality. Another consideration

is the value of the gifted, or at any rate

better than average, student to the society in

the future.

Like it or not, it is evident that the future

is going to require a lot of highly educated

people, including many with specialized skills

or talents. It will be well if the schools can

- 24-

give them a broad cultural background to

buttress their narrower specializations, but

in any case it is no service to the nation

to discriminate against the children with the

best brains.

Finally, a value that can be viewed quite

apart from pragmatic concerns is the quality

of education itself. Generally speaking we

think the quality has been improving in the

wake of growing disenchantment with the per

missive theories of progressive education

and a return to emphasis on basic subjects

and high academic standards. The track

experiments are one important manifestation

of that search for excellence.

Those who put an arbitrary and illusory

equality ahead of excellence are, we believe,

trapped in an intellectual confusion. By

putting a premium on dullness they could, if

their theories prevailed, set back the prom

ising recent course of education.”

That which has occurred in Washington, D.C. has been found

to be true in cities throughout the United States. The facts

are reported in common news media with greater frequency than

ever before. Writing in the Mew York Times Magazine of May 2,

- 25-

1965, Martin Mayer, a student of public schools and of American

education, revealed and commented upon the same kind of facts

evident in Washington, D.C. and that appear in the record of

this case. While writing about New York, he accurately portrayed

that which may be expected in Savannah if school children are

integrated en masse on a common plane and are not classified in

accordance with their intelligence and educability. In part he

said:

nPublic confidence in the (New York City)

school system is fearfully low and dropping:

White children are leaving the city public

schools at a rate of 40,000 a year." (The

Allen report, Mr. Mayer says, predicts a rate

of 60,000 annually).

” . . . Normal parents of any color need

not be racist to refuse to send their children

into classes where the tone is set by the low

expectations the schools have derived from

their experiences with minority ’groups’ . . . ”

’’Indeed, it is difficult to fathom the thought

process of people who insist that there will

be gains in the racial attitudes of Whites or

(gains in) the self-image of Negroes from daily

experiences which visibly proclaim that dark-

skinned children are ’dumber’ than pale-skinned

children.”

- 26-

"Not long ago, many of us felt that a large

share of the Negro failure in the schools was

itself the product of segregation; but almost

nobody whose opinion is worth considering

believes it today." (Emphasis supplied by

cour^)

"A year ago, for example, with a burst of

publicity, New York announced the abandonment

of the group IQ test, on the grounds that it

was culture-biased and discriminated against

Negroes. But the reading test that was sub

stituted slots children almost exactly where

they were in the abandoned IQ test— and what

difference there is works against the Negroes"

. . . "The real result of the acclaimed

abandonment of the IQ test, then, is that

Negro children in 1964-65 are more likely to

be in the bottom classes of 'integrated schools’

than they were in 1963-64."

"The tradition of success is almost gone— in

increasing numbers, teachers and principals live

with the expectation of failure and weave a

safety net of excuses."

" . . . The decline will be fairly precipitous

but no one will be able to mark the place where

- 27-

the system fell over the cliff and became a

custodial institution for children who have

no future.”

The massive intelligence test data collected in the Savannah-

Chatham County Schools is easily accessable. The Supreme Court

and the Court of Appeals left the defendants free in this case to

use their intelligence in applying or making use of such data.

It is too late for the defendants "to weave a safety net of

excuses" for further impairing the educational opportunities of

little children. It is too late "to weave a safety net of

excuses" for discrimination against white applicants for teaching

positions and against white teachers in their scale of pay.

No evidence has been presented to this Court to justify any

conclusion or assumption that children with average I.Q.’s of

SO can be equalized with children with average I.Q.'s of 100.

All of the evidence points to injury to the brighter children

and psychological shock to the slower children. Those who would

sacrifice or render useless the talents of a nation in a vain

attempt to accomplish the impossible should be restrained by

government and not encouraged.

ORDER AND DECREE

(1) It is ordered that the defendants, their agents, officers,

successors in office, and all persons in active concert with them,

be and each such person is hereby enjoined from maintaining in the

operation of the Savannah-Chatham County School System any

distinctions based upon race or color, but they are enjoined and

required to maintain and enforce distinctions based upon age,

mental qualifications, intelligence,achievement and other apti

tudes upon a uniformly administered program.

(2) It is specifically ordered that colored and white school

teachers shall hereafter be employed in accordance with identical

standards and it is specifically ordered that the employment of

Negro school teachers with a minimum grade of 400 on the National

Teachers Examination while requiring White applicants to have a

minimum grade of 500 on the National Teachers Examination shall

be immediately terminated. It is further ordered that the

defendants shall, on or before May 15, 1966, abolish every rule

or policy under which colored applicants for school teacher

positions or colored school teachers are accorded preference over

white applicants or teachers as a result of race and color.

(3) Pursuant to the decision of this Court on August 23,

1965, discrimination in favor of Negro teachers and against

White teachers with greater competence, as to pay, shall be

terminated on or before the beginning cf the school year 1966-67.

The defendants shall, on or before May 15, 1966, file with this

Court a detailed plan for the non-discriminatory hiring and

payment of teachers without regard to race and color and in

whieh intelligence, experience, competence and merit shall be

controlling factors in the future employment and retention of

teachers. Said plan shall also recite steps taken and to be

taken to correct the injustices resulting from past discrimination.

- 29-

(4) All questions relating to the integration of teaching

staffs are deferred for a further hearing and order after the

desegregation order set forth herein is put into effect and

discrimination in the employment and pay of teachers shall have

been terminated.

Except as herein modified, the revised plan of desegregation

submitted by the intervening White children and approved by

counsel for the defendant School Board is hereby allowed and

approved and it is made a part hereof.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that a copy of this decree with the

revised plan of desegregation shall be served upon each member

of the Savannah-Chatham County School Board, upon the Superin

tendent of Schools and upon counsel for all of the parties, and

defendants shall cause a complete copy to be published in a

newspaper in Savannah.

The Court retains jurisdiction of this cause to amend or

modify this decree and to permit amendments or modifications

of the desegregation plan adopted as a part of this decree and

to issue such further orders as may be necessary or appropriate.

The costs incurred in this proceeding to date are not taxed

against any party.

This _J___ day of

UNITED STATES DlfiT&ICt JUDGE

- 30 -

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SAVANNAH DIVISION U. S. DISTRICT COURT

FILED IN OFFICE

RALPH STELL, BT NEXT FRIEND, et al.,

Plaintiffs

vs.

SAVANNAH-CHATHAM COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants

and

‘.WHENCE ROBERTS, et al.,

Interveners

CIVIL ACTION NO. 1316

ORDER ON PLAN OF DESEGREGATION

SUBMITTED BY DEFENDANTS____

QUESTIONS FOR DECISION

The above case was tried on its merits and a decision rendered

on June 28, 1963. 220 F.Supp. 667. The decision was appealed to

che Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals and the following order entered:

"The judgment is reversed and the case

remanded for further proceedings not in

consistent herewith" (333 F.2d 55, 66).

In its decision the Court of Appeals ordered that:

"any plan hereafter promulgated must be

carefully inquired into by the District

Court with close attention being paid to

the burden of proof that is on the school

board to justify delay." (333 F.2d 55, 64).

As noted by the Court, the defendant School Board had already

instituted & plan of integration and no question of delay has arisen*

The issues before the Court on the trial and before the Court

on appeal are set out in the cited decisions. The uncontrovertod

evidence adduced on the trial of the case is in the Transcript of

Hearing and is set forth in most essentials in the decision by

this Court. In its decision the Court of Appeals pointed out that:

"the only question left - - - concerns the

manner in which it /Integration/ is to be

accomplished, and the time allowed for that

purpose." (333 F.2d 55» 62)

The decision by this Court was construed by the Court of

Appeals as one requiring continued segregation by race and color

in the Savannah schools in violation of the equal protection

clause of the 14th Amendment, as construed by the Supreme Court

in Brown vs. Board of Education. 347 U.S. 463. The Court held

further:

"In this connection, it goes without

saying that there is no constitutional

prohibition against an assignment of

- 2 -

individual students to particular schools

on a basis of intelligence, achievement

or other aptitudes upon a uniformly ad

ministered program but race must not be

a factor in making the assignments. How

ever, this is a question for educators and

not courts." (333 F.2d 55, 61, 62)

Thus, the Court of Appeals necessarily left open for this Court

to determine "the manner in which it /Integration/ is to be

accomplished". If it may be accomplished by the "assignment of

individual students to particular schools on the basis of

intelligence, achievement or other aptitudes upon a uniformly

administered program" without race being a factor in the making

of the assignments, such assignments may be made and, under the

willevidence in this case, should be made. Such- assignments/consist

with the Constitution, the Brown case and the decision of the Court

of Appeals in this case.

The Court takes judicial notice of the fact that in all

wall regulated school systems at all times school children in

general and regardless of race are permitted to progress on a

basis of intelligence, ability, achievement or other aptitudes.

In no case called to the Courtfs attention has it been held that

there is any constitutional requirement that children differing

in ages and qualifications be educated together. In Brown it

was held that only school children of "similar age" and the "same

educational qualifications" are entitled to be classed together in

schools under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

- 3 -

Where facts are fully developed and the evidence is undisputed

or without material conflict, a final judgment may be rendered ©r

directed by the reviewing court. (5B C.J.S. 425). Instead of

directing this Court as to what judgment should be rendered or as

to "the manner in which integration should be accompliaaied", as

the Court of Appeals had previously done in Stell vs. Ssvaaanh-

Chatham County Board of Education. 3lB F.2d 425» before hearing

any evidence, the Court of Appeals, after seeing a Tran,script of

the evidence, remanded the case to this Court for a dotarain&tion

of the manner in which integration should be accomplished. In

order to reach an intelligent and upright decision as to "the

manner in which integration is to be accomplished", without regard

to race, this Court must base that decision on law and the evidence

adduced upon the trial. The evidence adduced at the trial on the

merits in this case serving as guide lines for such purpoga was

undisputed, credible and convincing ,?£tnd was not questioned either

by the plaintiff or the Circuit Court.

*

THE MANNER IN WHICH INTEGRATION

IS TO BE ACCOMPLISHED______

The Intervenors alleged the following in paragraph 5(a) of

their plea in this case:

"(a) Existing ethnic group differences in

educational achievement and psychometric

intelligence are of such a magnitude that

extensive* racial integration will seriously

impair the academic standards and educational

-4“

opportunities for the petitioners and other

White children of Savannah-Chatham County.

The mean mental age of White school children

in Savannah-Chatham County ranges from two

to four school years ahead of the mean mental

age of Negro school children in Savannah-

Chat ham County. If the Negro and White

children are educated in the same schools

and in the same rooms with the same teachers

and all are grouped on the basis of academic

achievement the White students will average

from two to four years younger in chron

ological age than the Negro students. On

the other hand if such children are grouped

on the basis of chronological age, existing

academic standards in the now all-White

schools cannot be maintained and the system

of education for the White children will be

virtually destroyed, without any corresponding

benefit to the academic progress of the Negro

students.”

* The word ’'extensive" or major was arbitrarily defined in

paragraph 9 as "around 20c/o of the school population".

- 5“

The testimony of Dr. R. T. Osborne of the University of Georgia,

based on the testing of a large representative sample of negro and

white students in Savannah over a six year period, referred to in

220 F.Supp. 667, and more fully set forth in a monogram introduced

in evidence as an appendix in this case, entitled "Racial Difference

in School Achievement", established:

"On group achievement tests designed to evaluate

the degree of success in learning the basic subjects

taught in public schools the American Negro with

rare exception is unable to keep pace with established

grade norms. In most subjects the average Negro

child falls behind the norm group at the rate of

almost one-third of a grade per year, until by

the time he graduates from high school he is in

some areas four full years below the twelfth grade

standard.” (Appendix, p. 3)

It was revealed with respect to Savannah pupils: (p. &)

"Growth patterns of mental ability grade place

ment for the two groups are seen in Figure 3 •• The

difference in mental maturity of over two years at

the sixth grade (1954-) whs slightly attenuated at

the eighth grade testing (1956), but by the second

semester of the tenth grade (1958) the means of

the two groups are separated by over three years.

The same relative position of the two corves was

maintained through the last testing period of the

-6-

experiment, twelfth grade (I960). By the time

the students were examined at the tenth grade

there was practically no overlap in I.Q.; that

is, only one tenth grade child in the white

group earned an I.Q. below the median I.Q. of

the Negro children in the same grade. At the

tenth grade only one per cent of the Negro

pupils equalled or exceeded the median I.Q.

of the whites (Table I).n (Appendix, p. 8)

In summarizing his results of the studies of the Savannah

schools, Dr. Osborne dealt with the specific question that now

concerns this Court. He said:

"If public schools are ordered to integrate

en masse there appear to be three possible courses

of action:

1. Lower the educational standards and level

of instruction in the white schools to the

present passing level in the Negro schools.

The net result of this would be to maintain

for Negro pupils standards now existing in

their schools, but lower expectations for

the white children two to four years be!

their present grade norm. If this plan were

adopted, there would be few if any failures

or repeaters among the white children because

they would almost never do so poorly as to

- 7-

fail by present Negro standards. It goes

without saying that no reasonable citizen

would sanction such a plan to lower our

educational standards at a time when there

is a world-wide attempt to strengthen

teaching and up-grade education at all

levels.

2. Raise educational standards required of

the Negro child to those required of white

children and maintain the present level of

instruction and rate of failures. This

alternative would result in a 40 to 60 per

cent Negro failure rate in intermediate

grades. At the high school level where

achievement differences are of the magni

tude of three to four years, failure rate

for the Negro student would be 80 to 90

per cent with larger and larger numbers

of Negro children piling up in the lower

grades.

3. The final alternative would be to maintain

the two existing levels of instruction and

to apply differential marking and evaluation

systems to the two groups. This alternative

would result in de facto segregation because

for teaching efficiency learners within each

school are grouped according to achievement

and learning ability.

- C -

"None of the proposed alternatives represents

a real solution to the problem and e^ch would result

in educational chaos and confusion and bring about

an over-all weakening of the educational system.

The school administrator who has the responsibility

of providing meaningful educational experiences for

all children must have an instructional program

that will provide realistic educational goals for

all boys and girls regardless of race.

"In regions of the United States where the Negro

population is relatively small there may bo no

problem of balancing the schools in terms of race.

However, in the South-eastern United States where

upwards of 30 per cent of the population is Negro,

racial differences in school achievement can no

longer be ignored. Attempts to explain the reasons

for the differences on the basis of environmental

or genetic conditioning will not solve the problem.

Regardless of etiology, racial differences in

school achievement do exist and must be reckoned

with." (Appendix, pp.17, 18.)

Since the original Brown case, 347 U.S. 483, held that only

children of "similar age" and the "same educational qualifi

cations" are entitled to be classed together in schools under the

equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment, this Court was

free to find and did find upon the unchallenged and unquestioned

evidence that in order for school children to be effectively

- 9 .

educated in S&v&nn&h-Chathaa County they Bust he separated sad

classified as to age and educational qualifications. Facts thus

established are final and are not subject to reversal. It is the

law of this case and the law of the land that separation may not

be accomplished by using race and color as sorting criteria, but

the law leaves school authorities free to educate school children

efficiently without regard to race or color.

In addition to the evidence in the record on appeal, a piece

of newly .discovered evidence was introduced before the Court at the

hearing. It is a published study entitled "PROJECT TALENT" (1963).

which is an official report of a research study based on conditions

found in 773 public senior high schools in all sections of the

United States. It was made as a part of a Research Program conducted

by the University of Pittsburgh and financed by and conducted in

behalf of the Office of Education, u. S. Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare, (the agency now charged by law with enforce

ment of the desegregation provisions of the Civil Rights Act of

1964). It reports that the indiscriminate integration of school

children by race without regard to diversities of ages and mental

qualifications tends to deprive fast learners of opportunities for

advancement and to decrease the mean scores of all school children

while increasing drop-out rates of slow learners and decreasing

chances of college entry by average learners, regardless of the

environment of such children. (Project Talent (1963) pp. 4-6)

No effort was made by the plaintiff or the defendant to

refute or disparage this additional evidence. Indeed, the

plaintiff in this case has not at any time assumed any position

contrary to the findings of this Court from the evidence and

from the findings made at the behest of the United States

- 1 0 -

Department of Health, Education and Welfare. The stipulation made

by Mrs. Motley during the trial of this case and while Dr. Henry E.

Garrett, formerly of Columbia University and now of the University

of Virginia, was on the stand, has never been withdrawn and must be

accepted as true, to-wit:

"negroes, generally, on achievement tests, do

not perform as well as whites - - - we will

stipulate that. He doesn’t have to testify

to it. We will agree to that."

"The Court: Agree to what?

"Mrs. Motley: That these tests, which have

been administered, show that negroes, generally,

do not perform on the achievement tests as well

as whites. Now, if that is all he is going to

show, we will stipulate that, because the other

witness /Sr. Osborne/ has already said that."

(Transcript of Proceedings, p. 134)

In the plan filed by the defendant School Board now before the

Court for consideration, there is no indication that integration is

to be accomplished in any other manner than congregating children

because of race and color. In fact, the plan takes no account of

age and qualifications and the es&ex permissible criteria for

classification, other than race or color, pointed out by the

Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. To do so, it is urged by counsel

for defendant in support of the plan tendered,

"would tend to develop ’superiority complexes’

among those of high intelligence and aptitudes,

-11

and 'inferiority complexes' among those of

lower intelligence and aptitudes who would

be placed in what could well be regarded as

'schools for the dumb' or 'schools for the

retarded'; such encouragement in a public

school system operated in a democracy would

be unthinkable”.

Such a contention is itself "unthinkable”. To restrain bright

children in order to keep "dumb” children from experiencing the

urge that goes with an "inferiority complex” would subvert and

nullify the educational process. Excellence is not to be penalized

in order to exalt mediocrity.

It requires no considerable amount of intelligence for anyone

to discover that a six or a sixteen year old child is not mature

enough to change the culture and improve the weaknesses of another

individual or race. The advancement of one should not be retarded

on the theory that by doing so those dissimilar in age and

qualifications will profit by such repression of talent.

IT IS ORDERED that the plan filed by defendants be and the

same is disapproved and disallowed and defendants are hereby ordered

promptly to prepare and submit a plan of desegregation not

inconsistent with but which will accord with (1) the unquestioned

and undisputed facts adduced at the trial and subsequent hearing

of this case; (2) the decision of the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals; and (3) the decision of the Supreme Court in Brown, to

the end that race or color will not be factors. The plan should

assure that integration may be accomplished in such a manner as to

- 1 2 -

provide the best possible education for all school children with

the greatest benefits to all school children without regard to

race or color* but with regard to similarity of ages and qualifi

SCHOOL TEACHERS

The plaintiffs prayed in their petition for- integration of

teachers but stated at the last hearing that they would not new*

insist upon it. Intervenors stated that they would insist upon

white teachers being no longer discriminated against in favor of

negro teachers.

It having been made to appear upon the trial of this case

(Appendix, p. 16) that in Savannah "The mean yearly salary of

Negro teachers markedly exceeded that of the White teachers',"

and that "Negro principals assigned relatively lower competence

ratings to the Negro teachers tinder their supervision than the

white principals assigned to the white teachers under their

supervision®;

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the plan shall provide that

discrimination in favor of Negro teachers and against Unite

teachers shall be terminated.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED that the defendant School Board shall

continue to collect and shall give effect to test results so tha

race and color as such shall play no part in the assignment of

school children or teachers and so that classifications accord!;-

to age and mental qualifications may be made intelligently, fair

and justly.

ORDERED FURTHER that all objections inconsistent herewith

e overruled.

This day of e—, 1965.

stEIUTTSIIrt

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

- 14-

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

SAVANNAH DIVISION

RALPH STELL, By Next Friend, et al.,

Plaintiffs

vs.

SAVANNAH-CHATHAM COUNTY BOARD OF

EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants

LAWRENCE ROBERTS, et al.,

Intervenors

ORDER ON DESEGREGATION PLAN

The Desegregation Plan previously submitted by the Defendant,

The Board of Public Education for the City of Savannah and County

of Chatham, with the additions and deletions contained in the Plan

set forth below is hereby allowed and approved as in full compliance

with this Court’s Order of August 23rd, 1965:

DESEGREGATION PLAN

1. In the assignment, transfer, or continuance of pupils

among and within the schools, or within the classroom and other

facilities thereof, the following factors, in addition to those

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 1316

which are normally considered in these respects, shall be con

sidered with respect to the individual, (1) choice of the pupil

or his parents or guardians, (2) availability of space and

facilities in and for the school chosen, (3) proximity of the

school to the place of residence of the pupil, and (4) the age

and mental qualifications of the pupil. In such connection,

no consideration shall be given to the race of the pupil. Where

space and facilities are not available for all, priority shall

be based on proximity, except that for justifiable educational

reasons and in hardship cases other factors not related to race

may be applied. Administrative assignments or reassignments

may be made in cases of overcrowding, in hardship cases, in cases

of inability to keep up with the progress rate of his or her

class, and for disciplinary reasons. When such administrative

assignments are made they shall also be based on relative

proximity and available facilities, giving consideration to

pupil choice where possible.

2. Subject to supervision and review by the Board, the

Superintendent of Schools shall have authority and be charged

with responsibility with respect to the assignment (including

original and all other admissions to the school system) transfer

and continuance of pupils among and within all public schools

operated under the jurisdiction of The Board of Public Education

for the City of Savannah and the County of Chatham.

3. The Superintendent shall have authority to establish

each school year attendance areas which shall be based upon

- 2-

all pertinent and relevant factors, except race may not be

considered, so that choice of schools for pre-registration and

final registration may be made in a reasonable and orderly

manner. All existing school assignments shall continue without

change until or unless transfers are directed or approved by

the Superintendent or his duly authorized representative.

4. Assignments and transfers of pupils shall be made on

forms which will be available at the office of the Superin

tendent of Education, 208 Bull Street, Savannah, Georgia, and

the choice of the pupil shall be stated at the pre-registration

or if the pupil does not pre-register, then at the final

registration dates as determined by the Superintendent for

all students.

5. A separate application must be filed by each pupil

desiring assignment or transfer to a particular school and no

joint application will be considered.

6. Applications for assignment or transfers of pupils

must be filled in completely and legibly, and must be signed

by the parent or the legal guardian of such child for whom

application is made.

7. Action taken by the Superintendent on each appli

cation shall be mailed to the parents or guardian at the

address shown on the application within 15 days thereafter,

and such action shall be final unless a request in writing

is made to the Board within 10 days thereafter for a hearing.

£. A parent or guardian of a pupil may file in writing

with The Board of Public Education for the City of Savannah

- 3 -

and the County of Chatham objections to the assignment of the

pupil to a particular school, or may request by petition in

writing assignment or transfer to a designated school or to

another school to be designated by the Board. Unless a hearing

is requested, or unless the Board deems a hearing .necessary,

the Board shall act upon the same within a reasonable time

stating its conclusions. If a hearing is requested or if the

Board deems a hearing necessary with respect to the Superin

tendent’s conclusion on an application, the parents or guardian

will be given at least ten days written notice of the time and

place of the hearing. The hearing will be begun within twenty

days from the receipt by the Board of the request or the

decision by the Board that a hearing is necessary. Failure

of the parent or guardian to appear at the hearing will be

deemed withdrawal of the application.

9 . The Board may conduct such hearing or may designate

not less than three of its members to conduct the same and

may provide that the decision of the members designated or a

majority thereof shall be deemed a final decision by the Board.

The Board of Education may designate one or more of its members

or one or more competent examiners to conduct any such hearing,

take testimony, and report the evidence with its recommendation,

to the entire Board for its determination within ten days after

the conclusion of such hearing. In addition to hearing such

evidence relevant to the individual pupil as may be presented

on behalf of the petitioner, the Board shall be authorized to

- 4 -

conduct investigations as to any objection or request, including

examination of the pupil or pupils involved, and may employ such

agents and others, professional and otherwise, as it may deem

necessary for the purpose of any investigations and examinations.

10. Unless postponement is requested by the parents or

guardian, the Board will notify them of its decision within ten

days after its receipt of the report of the examiner, or the

conclusion of any hearing before the Board. Exceptions to the

decision of the Board may be filed, within five days of notice

of the Board’s decision, and the Board shall meet promptly to

consider the same; provided, however, that every appeal shall

be finally concluded before November 1st of each year hereafter.

Provided further that nothing herein contained shall be construed

to deprive any person dissatisfied with the final decision of

the Board of the right to appeal to the State Board of Education

as provided by law.

11. If, from an examination of the record made upon

objections filed to the assignment of any pupil to a particular

school, or upon an application on behalf of any pupil for assign

ment to a designated school, or another school to be designated

by the Board, or from an examination of such pupil by the Board

or its authorized representative, or otherwise, the Board shall

determine that any such pupil is between his or her seventh and

sixteenth birthdays and is mentally or physically incapacitated

to perform school duties, or that any such pupil is more than

sixteen years of age and is maladjusted or mentally or otherwise

- 5-

retarded so as to be incapable of being benefited by further

education of such pupil is not justified, the Board may assign

the pupil to some available vocational or other special school,

or terminate the public school enrollment of such pupil altogether.

12. Student assignments and transfers shall be made in

accordance with the rules and regulations stated herein and

without regard to race or color. The original Plan, which is

amended hereby, provided for the desegregation for the School

Year 1963-1964 of students in the 12th grade, and thereafter, in

each successive year, to the immediate lower grade, and the 12th

and 11th grades, therefore, were desegregated under the original

Plan; such Plan is now amended to include all grades for 1966-67.

13. Nothing contained in this Plan shall be construed to

prevent the separation of boys and girls in any school or grade,

or to prevent the assignment of boys and girls to separate schools.

14. In addition to the criteria hereinbefore set forth,

the Defendant Board shall in making or granting assignments and/or

transfers take into consideration the similarity of.mental quali

fications, such as intelligence, achievement, progress rate and

other aptitudes, such to be determined upon the basis of Nationally

standardized tests. No student shall have the right to be assigned

or transferred to any school or class the mean I.Q. of which exceeds

the I.Q. of the student, nor shall a student be assigned or

transferred to any school or class, the mean I.Q. of which is less

than that of the student, without the consent of the parent or

guardian. New students coming into the system or moving from one

- 6-

district to another shall he assigned to their normal neighborhood

school. If a new student is not satisfied with his school

assignment, then his case will be handled as that of any other

student requesting a transfer.

15. Salaries' paid to teachers by said Board shall be based

on their mental qualifications, capabilities, merit and competence

as determined by the results of Nationally standardized teacher

examinations and the judgment of supervisors as to their performance,

in which race and color shall play no part.

16. If any paragraph of these rules and procedure shall be

held by any court of competent jurisdiction to be invalid for any

reason, the remaining paragraphs shall continue of full force and

effect. If any portion, clause or sentence of any paragraph shall

be held by any court of competent jurisdiction to be invalid for

any reason, the remainder of any such paragraph shall continue of

full force and effect.

FURTHER ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that said Defendant Board

put this Plan into operation not later than the school year 1966-67,

and publish it in a Newspaper of general circulation in Chatham

County, Georgia within thirty (30) days from this date, and

thereafter at least once each year.

FURTHER ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that this Court retain

jurisdiction of this case for the rendering of any additional

Orders and Judgments which the Court may deem proper.

In Open Court, this November , 1965.

JUDGE, UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT,

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

- 7-