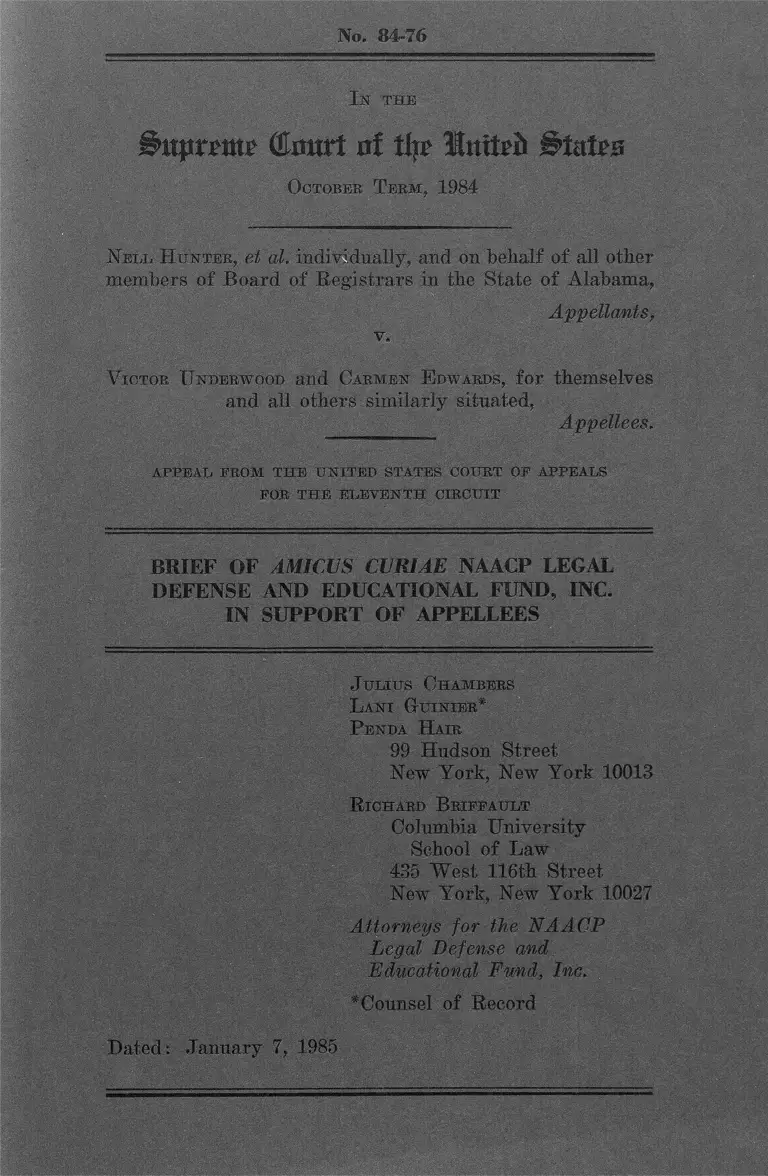

Hunter v. Underwood Brief of Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hunter v. Underwood Brief of Amicus Curiae in Support of Appellees, 1985. 3a8fe8b5-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/13f8acc4-3e4c-4599-ba2d-f4cb3b70b5db/hunter-v-underwood-brief-of-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 84-76

In THE

G I m tr l n i t t y I t t t t p f t f t t o t w

October T erm, 1984

Nell H unter, et al. individually, and on behalf of all other

members of Board of Registrars in the State of Alabama,

Appellants,

v.

V ictor U nderwood and Carmen E dwards, for themselves

and all others similarly situated,

Appellees.

APPEAR PROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEARS

POR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

J ulius Chambers

L ani Guinibr*

P enda H air

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

B ichard Brippault

Columbia University

School of Law

435 W est 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

Attorneys for the N AACP

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

* Counsel of Record

Dated: January 7, 1985

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities .............. iii

Statement of Interest of Amicus

Curiae ................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .............. 4

I. VOTING IS A FUNDAMENTAL

RIGHT WHICH MAY NOT BE

DENIED UNLESS NECESSARY TO

PROMOTE A COMPELLING STATE

PURPOSE ...................... 8

II. THE MISDEMEANANTS

DISENFRANCHISEMENT CLAUSE

WAS ADOPTED FOR INVIDIOUS

RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

REASONS IN VIOLATION OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT ........ 18

III. DISENFRANCHISEMENT OF

POOR WHITES BECAUSE OF

THEIR POLITICAL BELIEFS OR

LACK OF WEALTH VIOLATES THE

FIRST AND FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENTS .................. 26

!V. RICHARDSON v. RAMIREZ,

DOES NOT INSULATE THE MIS

DEMEANANTS ' DISENFRANCHISEMENT

CLAUSE FROM STRICT

SCRUTINY .................. 32

l -

V, THE TENTH AMENDMENT

PROVIDES NO PROTECTION FOR A

Page

STATE DISENFRANCHISEMENT

MEASURE WHICH VIOLATES THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT ......... 39

VI. THE MISDEMEANANTS

DISENFRANCHISEMENT CLAUSE

VIOLATES THE VOTING RIGHTS

ACT ......................... 40

CONCLUSION ....................... 42

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases;

Allen v. State Board of Elections,

Page

393 U.S. 544 (1969) ........ 2

Anderson v. Celebrezze, 460 U.S.

780 ( 1 983) ................... 10

Anderson v. Martin, 365 U.S. 399

(1964) ....................... 2

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Dev. Corp., 429 U.S.

252 ( 1977) ...... . 18, 1 9,24,28,36

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134

( 1 972) ...................... 31

Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89

(1 965) ................ 29

Cipriano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S.

at 701 ( 1 969) ............... 30,32

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446

U.S. 55 ( 1 980) ........ 2,25,36,37

City of Rome v. United States, 446

U.S. 156 (1 980) ......... 25,39,40

Clements v. Fashing, 457 U.S. 957

(1982) 10

Page

Connecticut Citizen Action Group

v. Pugliese, No. 84-431 (WWF)

(D. Conn. Sept, 25, 1984),

stay den *d , F. 2d _____

(2d Cir. Oct~ 1, 1984) ...... 12

Dunn v® Blumstein, 405 U.S® 330

(19*72) 11,29

East Carroll Parish School Bd. v .

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636

( 1976) .................. O

Evans v. Cornman, 398 U.S. 419

( 1 970) ............. ......... 9,30

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S.

445 ( 1 976) ................... 40

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S.

339 ( 1 960) ................... 25

Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S.

347 ( 1 91 5) .............. . 23,25

Harris v . Graddick, 593 F.Supp.

128 (M.D. Ala. 1984) ........ 41

Harper v . Virginia Board of

Elections, 383 U.S. 663

( 1966) .... .................. 9,3 1

Illinois State Board of Elections

v . Socialist Workers Party,

440 U.S.■173 (1979) ......... 1 0

iv

Page

Kramer v. Onion Free School Dist.

No. 15, 395 U.S. 621

( 1969) ................... 5,10

Lassiter v. Northampton County Board

of Elections, 360 U.S. 45

(1959) ...................... 37

Lubin v. Panish, 415 U.S. 709

(1974) ..................... 31

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415

( 1 963) . 2

Personnel Administrator of Mass,

v. Feeney, 442 U.S. 256

(1979) ......... ......... .... 24

Phoenix v. Kolodziej ski, 399 U.S.

204 ( 1970) ......... 31

Project Vote! v. Ohio Bureau of

Employment Services, 578

F. Supp. 7 (S.D. Ohio

1 982) ....... 13

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533

( 1 964) . 9

Richardson v. Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24

(1974) .... 7,32-36,38

Rhode Island Minority Caucus,

Inc. v. Baronian, 590 F .2d 372

(1st Cir. 1979) ............. 1 2,1 3

v

Page

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613

(1982) ................... 2,25,37

Smith v. Allwright, 321 D.S. 649

(1944) ...................... 2

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. 301 (1966)...... 20,23,38,40

United Jewish Organizations v .

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) .. 2

United Public Workers v. Mitchell,

330 U.S. 75 ( 1 947) .......... 30

United States v. Marengo Co.

Comm'n , 731 F .2d 1546 (11th

Cir. 1984), appeal dismissed, 83

L.Ed.2d 311 (Nov. 5, 1984)(No.

84-243) .................. 1 1,41

United States v. State of Alabama,

252 F. Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala.

1966) (three judge court) ... 21,23

Voter Education Project v.

Cleland, No. 84—1181A

(N.D. Ga.) .....___ ......... 14

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 ( 1 976) ................... 20,36

Wesberrv v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1

( 1964) ....................... 9

vi

Page

White v. Regester, 412 U. S. 755

(1 973)' .................. 37

Williams v. Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23

( 1 968) ............... 10,39

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

( 1886) ................... 4

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

U.S. Const. First, Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments ........ Passim

U.S. Const. Tenth Amendment .... . 7,39,40

Voting Rights Act of 1965, 42

U.S.C. § 1973(a) Section 2

as amended in 1982 .......... 7,40

Ala. Const. of 1901, Section 182 Passim

Ga. Const. Art. 2 Sec. 1,

para. 3(a) ................... 35

Other Authorities

After the Voting Rights Act:

"""“""Registration ’ Barriers, Report of

the Subcommittee on Civil and

Constitutional Rights of the House

Committee on the Judiciary,

98th Cong., 1st Sess.

(October 1984) .............. 14,16

- vii

Page

Note, Restoring the Ex-Offender's

Right to Vote: Background

and Development, 11 AM,

Grim. L. Rev. 721 (1973) .... 34,35

P. Lewison, Race, Class and

Party 81 (1963) ............. 24

Schmidt, Principle and Prejudice:

The Supreme Court and Race in

the Progressive Era. Part 3:

Black Disfranchisement from the

KKK to the Grandfather Clause,

82 Colum. L, Rev. 835

( 1 982) ....___ .............. 21,27

Special Project, The Collateral

Consequences of a Criminal

Conviction, 23 Vand. L. Rev.

929 (1 970) ....... .......... 34-35

- viii

No. 84-76

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1984

NELL HUNTER, et al. INDIVIDUALLY,

AND ON BEHALF OF ALL OTHER MEMBERS

OF BOARD OF REGISTRARS

IN THE STATE OF ALABAMA,

Appellants,

VICTOR UNDERWOOD AND CARMEN EDWARDS,

FOR THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS SIMILARLY

SITUATED,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educa-

tional Fund, Inc. is a non-profit corpora

tion which was established for the purpose

2

of assisting black citizens in securing

their civil rights. It has been cited by

this Court as having "a corporate reputa

tion for expertness in presenting and

arguing the difficult questions of law

that frequently arise in civil rights

litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 O.S.

415, 422 (1963). The Legal Defense Fund

has appeared before this Court on numerous

occasions representing parties or as

amicus curiae in cases raising constitu

tional and statutory issues concerning the

1

right to vote.

See e.g., Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613

TT982) (amicus curiae); City of Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 O.S. 55 ( 198 0 ); United J ewi s h

Organizations v. Carey, 436 U.S. 144

(16^7); East Carroll Parish School Bd. v.

Marshall, 4njTTfTsT~?55"~(T976 );' Allen vT State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544

(19££); Anderion v. Mart fin, 375 U.S. 399

(1964); Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649

(1944).

3

This case presents intertwined

questions involving the grounds for

disenfranchisement of voters and the proof

and significance of racially invidious

intent. The Legal Defense Fund is

actively involved in challenging State

standards, practices and procedures which

abridge the right to vote. These State

restrictions fall with greatest weight on

blacks, other minorities, and the poor.

The Court’s resolution of the issues

presented by this case may materially

affect the ability of amicus to advance

its program of vindicating the right to

vote.

Letters consent ing to the filing of

this brief by both parties are being

lodged with the Clerk of Court.

4

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The issues raised by this case go to

the heart of American ' democracy — the

right to vote, and the right to be free

from invidious racial discrimination.

The right of suffrage, the right

which is "preservative of all rights,"

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 370

(1886), is the cornerstone of the American

political system. A state’s denial of the

right to vote to any member of the

community may be sustained as constitu

tional only if it is narrowly tailored to

promote a compelling state purpose.

The clause of Section 182 of the

Alabama Constitution of 1901 which the

court below declared violative of the

United States Constitution is precisely

the type of State restriction of the

franchise which this Court has stated must

receive "close and exacting examination."

5

Kramer v. Union Free School Dist. No, 15,

395 U.S. 621 , 626 ( 1969). The clause

completely denies the right to vote to

otherwise eligible citizens of Alabama

convicted of crimes not punishable by

imprisonment in the penitentiary — e.g. ,

misdemeanors — involving "moral turpi

tude." Such a denial of the right to vote

may be sustained only if it is necessary

to promote a compelling State purpose.

It is at the point of inquiry into

the State's purpose, however, that the

denial of the right to vote becomes joined

with an even uglier affront to American

democracy — invidious racial discrim

ination. The United States Court of

Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit found,

and the historical record fully supports

this finding, that the clause was adopted

for racially invidious reasons, as part of

a broad and thoroughgoing program of white

6

Alabamians to disenfranchise blacks.

Appellants, however, argue that the

clause may be sustained because it was

adopted as an element of a disfranchise

ment scheme aimed as well at "populists™

or "poor whites,™ not just blacks. This

argument, even if it were a correct

reading of the State's purpose, does not

help their case. The denial of the right

to vote on grounds of political belief or

socio-economic status is as impermissible

as disenfranchisement by reason of race.

Like discrimination against blacks,

discrimination against poor whites or

Populists cannot be a compelling state

interest.

Appellants remaining arguments are no

more than makeweights. While this Court

has held that the disenfranchisement of

felons does not, in and of itself, violate

the Equal Protection Clause of the

7

Fourteenth Amendment , Richardson v«

Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974), this case

does not involve the disenfranchisement

for commission of a crime s impl iciter.

Rather, this case turns on a disenfran

chisement clause adopted for constitu

tionally proscribed reasons — either

invidious racial animus as appellees

allege and the Eleventh Circuit found, or

political and wealth-based discrimination

as appellants contend. Richardson v.

Ramirez can provide no shelter for a

measure which was intended to deny the

franchise to a group of voters because of

the color of their skin, their lack of

assets, or their political beliefs. Nor

does the Tenth Amendment provide a shield

for a denial of the franchise in violation

of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.

8

Finally, the clause in question

violates section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. § 1973(a). As

amended in 1982, section 2 bars the use of

voter qualifications which result in a

denial of the right to vote on account of

race or color. Even if the adoption of

the clause is held not to have been the

product of invidious racial intent in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, it

surely results in a denial of the right to

vote on account of race or color.

I. VOTING IS A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT

WHICH MAY NOT BE DENIED UNLESS

NECESSARY TO PROMOTE A COMPELLING

STATE PURPOSE.

The Court has frequently emphasized

the central role played by the right to

vote in the American system of constitu

tional government. The right to vote "is

of the essence of a democratic society,

and any restrictions on that right strike

9

at the heart of representative govern

ment ." Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 555

(1964). "No right is more precious....

Other rights, even the most basic, are

illusory if the right to vote is under

mined ." We sherry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1,

17 (1964). See also Evans v, Cornman, 398

U.S. 419, 422 (1970).

In order to secure fully our system

of democratic self-government, state

restrictions on the right to vote have

often been found constitutionally invalid

upon close examination. The right to

vote may not be taxed, Harper v. Virginia

Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966);

one person's vote may not be given less

we ight than any other person's, e.g .,

Reynolds v. Sims; Wesberry v. Sanders; and

the State may not unduly restrict the

ab ility of new parties or independent

cand idates to obtain positions on the

10

ballot. See, e.g., Anderson v. Cele-

brezze, 460 U.S. 780 (1983); Illinois

State Board of Elections v. Socialist

Workers Party;, 440 U.S. 173 (1979);

Williams v . Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23 (1968).

Cf. Clements v. Fashinq, 457 U.S. 957,

. r a a w o ™ — .m .» — a m .

964-65 (1982).

Burdens on the right to register and

cast a ballot, the heart of the constitu

tionally protected right to vote, are

subject to strict scrutiny. " [I]f a

challenged state statute grants the right

to vote to some bona fide residents of

requisite age or citizenship and denies

the franchise to others, the Court must

determine whether the exclusions are

necessary to promote a compelling state

interest." Kramer v. Union Free School

Dist. , supra. , 395 U.S. at 626-27. In

such a case, "the general presumption of

constitutionality afforded state statutes

11

and the traditional approval given state

classifications if the Court can conceive

of a 'rational basis' for the distinctions

made are not applicable." Id. at 627-28.

Rather, the state must show "substantial

and compelling reason" for the denial of

the franchise, Dunn v. Blumstein, 405 U.S.

330, 335 (1972) and must utilize the

"least restrictive means" to achieve that

goal. Id. at 353.

The lower federal courts have

recently decided or are currently con

sidering dozens of cases challenging

state-imposed barriers to voting under the

2

First and Fourteenth Amendments. The

The courts have recognized that

state administrative practices, such as

limitations on voter registration to

inconvenient times and locations, or dis

crimination in the appointment of voter

registrars on grounds of race or political

affiliation, can effectively abridge the

ability of citizens to register, and

therefore implicate the right to vote.

See, e.g., United States v. Marengo Co.

Convm'n, ^31 F. 2d 1569-70 (11th Cir.

12

ramifications of the arguments made in

this case go well beyond the narrow issue

of denying the franchise to certain mis

demeanants.

For example, in Connecticut Citizen

Action Group v. Pugliese, No. 84-431 (WWF)

(D. Conn. Sept. 25, 1984), stay den'd, ___

F. 2d _____ (2d Cir. Oct. 2, 1984), the Court

ordered the appointment of thirty special

assistant registrars to conduct registra

tion door-to-door and at various sites in

the community. That case involves the

claim that holding registration at only

one location in the city of Waterbury,

Connect icut violates the First and

Fourteenth Amendments.

1984); Rhode Island Minority Caucus, Inc.

v . Baronian, 5"§T5 FT 2cl 375 (1st Cir .

JT IW . —

13

In Rhode Island Minority Caucus, Inc,

v. Baronian, 590 F.2d 372 (1st Cir.

1979) t the Court held that allowing

registration drives to be conducted only

by members of the League of Women Voters

is unconstitu tional if racial animus

played a part in the decision. Several

courts have enjoined state and local

refusals to permit registration forms to

be distributed in public agency waiting

rooms. E.g. r Project Vote! v. Ohio Bureau

of Employment Services, 578 F. Supp. 7

(S.D. Ohio 1982).

Other cases challenging barriers to

voting are pending. In Georgia, for

example, citizens in many counties must

travel distances of 60 miles or more in

order to register at county courthouses

which are open only during normal business

hours -- when most citizens are at work.

The difficulty in registering is com

14

pounded by the fact that the state has no

rural public transportation. The failure

to permit registration at satellite

locations and during evening and weekend

hours is currently being challenged in the

case of Voter Education Project v. Cle-

1 and , No. 84-1181A (N.D. Ga.). Similar

registration barriers are at issue in

cases in Louisiana, Michigan, Arkansas,

Missouri, and Mississippi.

The devastating effect of such

barriers to registration was recently

documented by a congressional subcommit

tee . After the Voting Rights Act;

Registration Barriers, Report of the

Subcommittee on Civil and Constitutional

Rights of the House Committee on the

Judiciary, 98th Cong., 1st Sess. (October

1984). The subcommittee concluded:

15

A number of states limit regis

tration to a single central location

in a county, usually the county

courthouse. ...

Many registration offices are

open only on weekdays and during

normal business hours. Many offices

are closed during lunch hours. In

Virginia, most registration offices

only have regularly scheduled office

hours between 8 am—5 pm. Over half

are not open 5 days a week, and one

quarter are only open one or two days

a week. These limited hours conflict

with the working hours of most

people. Thus, working people must

take time off from work in order to

register.

... Courthouses are rarely

located in the minority community, so

minority citizens are required to go

to an unfamiliar part of town to

register.... [I]n rural areas, the

long distances to the courthouse

coupled with the lack of public

transportation turns getting to the

courthouse into a Herculean effort.

Third is the problem of intimi

dation. In Johnson County, Georgia,

the white sheriff makes a point of

stationing himself outside of the

door of the voter registration office

in the courthouse when blacks come to

register. ...

... In Shenandoah County,

Virginia, the registrar' s office is

located in the basement of the county

jail.

16

In Waterbury, Connecticut ...

the registrar refuses to deputize any

volunteers. In other places,

deputization is done selectively. In

Worcester, Massachusetts, the

registrar does not deputize volun

teers from the poor side of town ....

The technicalities of the form

also raise barriers. In New York,

signatures are required on both sides

of the form, otherwise the registra

tion is invalid. Other states

require the form to be notarized.

This requires the registrant to find

a notary public, and usually involves

a fee for the service. In effect,

this may work as an illegal poll tax.

Dual registration is yet another

barrier to full electoral participa

tion. This requires citizens to

register separately for both city and

county elections....

Purge laws, while not facially

objectionable, may operate unfairly.

Seven states purge voters without

individual notice. In Alabama,

selected counties with a higher

percentage of black voters have been

purged. Subcommittee Report at

4 - 1 0 .

Acceptance of appellant's argument

that the states have absolute, unreview-

able control over voting requirements and

17

qualifications would permit the continued

existence of several barriers and ob

stacles to voting, such as those described

above. Yet, these modern-day versions of

the poll tax are no more constitutionally

acceptable than their historic predeces

sors. Preservation of the precious right

to vote requires that all barriers to

voting be subjected to strict constitu-

tional scrutiny and permitted only when

justified by compelling governmental

interests.

In this case, appellants have failed

to offer any compelling state interest

which could justify the denial of the

franchise effected by the challenged

clause of Section 182. On either appel

lants' or appellees' theory of the

purposes of the framers of the Alabama

Constitution of 1901, the clause was

18

adopted for a constitutionally proscribed

reason and not to serve a compelling state

interest.

II, THE MISDEMEANANTS DISENFRAN

CHISEMENT CLAUSE WAS ADOPTED FOR

INVIDIOUS RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

REASONS IN VIOLATION OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

The Court of Appeals found that the

misdemeanants disenfranchisement clause of

Section 182 of the Alabama Constitution

was adopted with the intent, and has had

the effect, of disenfranchising blacks,

(J . S . at A-6 through A-141.) The court

properly applied the test for determining

discr iminatory intent set forth by this

Court in Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp,, 429 U.S. 252

( 1 977) , and its conclusion is amply

supported by the legal and historical

record.

19

In Arlington Heights, the Court

identified the factors which may be used

to prove that a law, while fair on its

face, was adopted for an invidiously

discriminatory purpose: "The historical

background of the decision is one eviden

tiary source, particularly if it reveals a

series of official actions taken for

invidious purposes." 429 U.S. at 267.

"The legislative or administrative history

may be highly relevant, especially where

there are contemporary statements by

members of the decisionmaking body,

minutes of its meetings, or reports." Id.

at 268. "The impact of the official

action -- whether it 'bears more heavily

on one race than another,1... — may

provide an important starting point.

Sometimes a clear pattern, unexplainable

on grounds other than race, emerges from

the effect of the state action even when

20

the governing legislation appears neutral

on its face.'5 Id. at 266, quoting

Washington v . Davis, 426 U. S. 229, 242

{ 1976) .

The Eleventh Circuit properly relied

on each of these factors in reaching its

determination that the disenfranchisement

clause in this case was adopted for

racially discriminatory purposes.

The ''historical background" to

Section 182 is clear: " [B]eginning in

1890, the States of Alabama, Georgia,

Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina,

South Carolina, and Virginia enacted tests

still in use which were specifically

designed to prevent Negroes from voting."

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S.

301, 310 (1966). The Alabama Consti

tutional Convention of 1901 "assembled

largely, if not principally, for the

purpose of changing the 1875 Constitution

21

so as to eliminate Negro voters." United

States v. State of Alabama, 252 P. Supp.

9 5, 98 (M.D. Ala. 1966) (three-judge

court). "'What they want is a scheme pure

and simple which will let every white man

vote and prevent any Negro from voting, '

reported the Birmingham Age-Herald about

the delegates at the Alabama Constitu-

tional Convention of 1901." Schmidt,

Principle and Prejudice: The Supreme

Court and Race in the Progressive Era.

Part 3; Black Disfranchisement from the

KKK to the Grandfather Clause, 82 Colum.

L. Rev. 835, 846 (1982).

The legislative history is also

clear. "Delegate after delegate took the

floor eager to be put on record as

favoring ’the absolute disfranchisement of

the Negro as a Negro'.... The Journals of

the Convention leave absolutely no doubt

as to what the delegates of the white

22

citizens of Alabama wished the Convention

to accomplish: ... 'it is our intention,

and here is our registered vow to dis

franchise every Negro in the state..,''"'

United States v. Alabama, supra, 252 F.

Supp. at 98, quoting comments by conven

tion delegate reported in the Official

Proceedings.

In developing their program of

disenfranchisement, the delegates took

care to avoid the strictures of the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Instead of directly curtailing the

franchise on grounds of race, the suffrage

committee "made resort to facially neutral

•tests that took advantage of differing

social conditions. Disenfranchisement for

commission of specified misdemeanors is in

pari materia with the "grandfather

clause," the poll tax, and the literacy

test -- a clear pattern of measures

23

neutral on the surface but adopted for the

purpose and having the effect of disen

franchising blacks,, and which were

subsequently declared invalid for that

reason. See, e.g., Guinn v. United

States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915) (grandfather

clause), South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

supra, 383 U. S. at 312, 33 3-34 (literacy

test), United States v. State of Alabama,

supra, (poll tax).

Although the clause at issue purports

to utilize a racially neutral criterion

misdemeanors involving moral turpitude —

moral turpitude was intentionally defined

to bring about the disenfranchisement of

blacks, The suffrage committee of the

Constitutional Convent ion chose offenses

that were believed to be peculiar to

blacks' low income and social status, such

as petty property offenses, and minor

sex-related crimes. (J . S. at A-10,

24

citing P. Lewison, Race, Class and Party

81 (1963).) Appellants' own expert, Dr.

Thornton, acknowledges that the disquali

fying crimes were those “associated in the

public mind with the behavior of blacks."

Joint App. at A-23.

The brunt of the non-penitentiary

offenses clause was, and still is, borne

by blacks. Joint App. at A-26 j J.S. at

A — 1 1. Thus, the elements of proving

racally invidious discrimination identi-

fied in Arlington Heights — historical

background, legislative history, pattern

of discriminatory enactments, and dis

parate racial impact -- are all present

3

here. Taken together they prove the

3 Therefore, this case differs significantly

from the veteran's preference upheld in

Personnel Administrator of Mass. v ■

Feeney”, 4 42 U. S. 25(> ( 1979). Unlike

Feeney, in which the worthy and legitimate

goals behind the veteran's preference were

stipulated, the classification here is

neither rationally based, traditionally

justified nor beneficent. Indeed,

25

"'insidious and pervasive evil* of racial

discrimination in voting." City of Rome

v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 174

(1980). A state restriction on the right

to vote adopted for racially invidious

reasons violates the Equal Protection

Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, Rogers

v. Lodge, 458 D.S. 613, 621-22 (1982),

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U. S. 55,

66-67 (1980) (plurality opinion), as well

as the Fifteenth Amendment. City of

Mobile, supra, Gomillion v, hightfoot, 364

U. S . 339 (1 960), Guinn v. United States,

supra.

appellants concede racial antipathy behind

the misdemeanant exclusion clause, and

proof of its discriminatory purpose,

contrary to the plaintiff' s case against

the Massachusetts veteran's preference, is

not solely based on inferences from its

disproportionate impact.

26

III. DISENFRANCHISEMENT OF POOR

WHITES BECAUSE OF THEIR POLITICAL

BELIEFS OR LACK OF WEALTH VIOLATES

THE FIRST AND FOURTEENTH .AMENDMENTS

Appellants contend that the misde

meanants exclusion clause of section 182

was not adopted solely because of anti-

black racial animus, but rather was

adopted for "political reasons,” to

d isenfranchise as well "poor whites" or

"populists ." (Brief for Appellants at

9-10, 12). Appellants' theory is prob

lematic as an interpretation of the 1901

Alabama Constitutional Convention, but

even if appellants' theory were true it

could not save the disenfranchisement

clause.

Appellants' theory assumes that the

"racial'1 and "political" purposes of the

Alabama Constitutional Convention were

distinct. To the contrary, in turn-of-

the-century Alabama and throughout the

27

Deep South at that time politics and race

were largely intertwined. See Schmidt,

Principles and Prejudices, supra, 82

Colum. L . Rev. at 842-47. Even appel

lants' expert Dr. Thornton, acknowledges

that the Constitutional Convention

delegates sought to achieve their "politi

cal ," anti-Populist, goal by "eliminating

the black vote that had — the courting of

which had represented the principal threat

from the po int of view of conservative

white democrats." (Joint App. at A-19.)

Moreover, in order to find that

section 182 was "political" and not

"racial" , the court must ignore most of

the historical record. Appellants urge the

Court "not to be misled by reading or

analyzing the proceedings of the Conven-

tion." (Brief for Appellants at 18.) The

speeches and debates of the delegates, the

anti-black statements, and the avowal of

28

anti-black purposes were all a "public

relations gesture," (Joint App. at A-23,

A-27). Appellants* expert acknowledges

that " [ i] f you read the four volumes of

the official proceedings — a fate I

wouldn' t wish on anyone --but if you

happen to? you will come away with the

sense that race simply dominates the

proceedings of the Convention." (Id, at

A-27). His solution is to ignore the

statements and actions of the delegates

and rely solely on their unstated inten

tions? as he divines them. Thus would

appellants have the Court ignore the

approach for identifying intent set forth

in Arlington Heights and pursued by the

Eleventh Circuit.

Most importantly? however? appel

lants' version of history cannot save the

misdemeanants d i sen f ranch isement clause

from invalidation. On appellants' theory

29

the clause is constitutional because it

was adopted with the intent to discrimi

nate against "poor whites’* or "Populists."

Such a contention would be laughable if it

were not so offensive. The franchise may

no more be denied on grounds of political

belief or lack of wealth than it may be

for racial animus.

" 1 Fencing out' from the franchise a

section of the population because of the

way they may vote is constitutionally

impermissible. ’ [T]he exercise of rights

so vital to the maintenance of democratic

institutions, 1 ... cannot be obliterated

because of a fear of the political views

of a particular group of bona fide resi

dents." Carrington v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89,

94 (1965) " ' [D]ifferences of opinion* may

not be the basis for excluding any group

or person from the franchise." Dunn v_.

Blumstein, supra, 405 U.S. at 355, quoting

30

Cipriano v. City of Houma, supra,, 395

0.S. at 7 0 5 - 0 6 . Accord, Evans v. Cornman,

398 U.S. 41 9, 422 (1970). As this Court

observed in another contest, "Congress may

not 'enact a regulation providing that no

Republican, Jew or Negro shall be ap

pointed to federal office.'" Un i t ed

Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75,

100 ( 1 9 4 7 ). These cases clearly establish

that where the right to vote is at stake,

political minorities as well as racial

minorities — "popul ists" as well as

blacks -- are protected by the Equal

Protection Clause. The desire to vanquish

one's political opponents or "fence out"

citizens hold ing unorthodox beliefs has

never withstood strict scrutiny or been

found to serve a compelling state interest

to justify the denial of the franchise to

the disfavored group. Indeed, a finding

that section 182 was adopted out of an

31

tipopulist or anti-poor white animus would

compel the determination that it violates

the Fourteenth Amendment,,

"Wealthy like race, creed, or color,

is not germane to one's ability to

participate intelligently in the electoral

process. Lines drawn on the basis of

wealth or property, like those of race ...

are traditionally disfavored" where the

franchise is at stake. Harper v. Virginia

Board of Elections, 383 U. S. 663, 668

(1 9 6 6). This Court has consistently held

unconstitutional under the Equal Protec

tion Clause wealth-based restrictions on

the franchise, such as the poll tax.

Harper, supra, excessive filing fees,

Lubin v. Panish, 415 U.S. 709 (1974),

Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972),

and statutes restricting to taxpayers the

right to vote on bond issues, Phoenix v.

Kolodziej ski, 399 U.S, 204 ( 1970), Cipri-

32

ano v. City of Houma, 395 U.S. 701 (1969).

The right of suffrage of "poor whites"

like that of blacks is protected by the

Constitution and may not be denied by

measures aimed at them because of their

lack of wealth.

IV. RICHARDSON v. RAMIREZ DOES NOT

INSULATE THE MISDEMEANANTS* DISEN

FRANCHISEMENT CLAUSE FROM STRICT

SCRUTINY.

Appellants contend that the misde

meanants disenfranchisement provision of

section 182 is insulated from Equal

Protection Clause review by virtue of this

Court's decision in Richardson v. Ramirez,

418 U. S . 2 4 (1974). In Richardson, the

Court cons idered that port ion of section 2

of the Fourteenth Amendment wh ich limited

the penalty of reduced state representa-

t ion in Congress to denials of the

franch i se "except for participation in

rebel 1 ion, or other crimes." The Court

- 33 -

concluded that this provision gave

'’affirmative sanction” to "the exclusion

of felons from the vote,” Id» at 54.

The case sub judice differs from

Richardson in two significant ways. First,

the disenfranchising crimes in Richardson

were felonies whereas the present case

concerns an invidiously selected list of

non-felonies. Richardson was predicated in

part on an examination of the historical

background of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Court noted that at the time of the

Fourteenth Amendment's ratification most

States had provisions in their constitu

tions which prohibited, or authorized

their legislatures to prohibit, the

exercise of the franchise by persons

convicted of felonies. Congress, in

readmitting the seceded states to the

Union, authorized those states to deny the

franchise for" 'participation in the

34

rebellion or for felony at common law*."

418 U.S. at 48,49. There was, however, no

similar finding that the "historical

understanding of the Fourteenth Amendment"

confirmed the disenfranchisement of

misdemeanants. Richardson has never been

applied to uphold a disenfranchisement of

non-felons.

Indeed, those states which disenfran

chise citizens for criminal convictions

have generally limited that penalty to

convictions of election-related offenses,

some subset of serious felonies, or at

most all felonies and "infamous crimes."

See generally Note, Restoring the Ex-

Offender’s Right to Vote; Background and

Developments, 11 AM. C r i m . L. Rev. 7 2 1 ,

727-29, 758-70 ( 1 9 7 3 ) ; Special Project,

The Collateral Consequences of a Criminal

Convict ion , 23 Vand. L. Rev. 9 2 9 , 9 7 5 - 7 7

(1970). According to these two surveys,

3 5

published in the early 1970’s, only two

states, Alabama and Georgia disenfran

chised for specified non-felony offenses,

defined as involving moral turpitude.

Note, supra, 11 Aits, Crim, L. Rev. at

758-6 1 and 766 n. 217? Special Project,

supra., 23 Vand. L. Rev. at 976 n.251. The

current Georgia Constitution disenfran

chises only persons convicted of "a felony

involving moral turpitude." GA. Const.

Art 2, sec. 1 para 3(a). {emphasis

supplied). Consequently, Alabama may be

the only state which today disenfranchises

any category of non-felons.

The Court, however, need not resolve

the applicability of Richardson to the

exclusion of misdemeanants because what

clearly sets this case apart from Richard

son is not the felony/non-felony distinc

tion but the finding of inv idious dis-

cr iminatory intent. There was no conten

36

tion in Richardson that the disenfran

chisement provision at issue was adopted

for racially discriminatory purposes, or,

for that matter, out of a political or

wealth-based animus. Richardson con

sidered only the question whether the

denial of the right to vote to felons was

per se unconstitutional.

The presence of discriminatory intent

is central to this Court's interpretation

of the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. See, e ,g. , City of

Mobile v. Bolden, supra, Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp,,

supra, Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

(1976). Particularly where the right to

vote is at stake, state laws or practices

which would be constitutional if they were

adopted for a legitimate purpose have been

held unconstitutional if they were adopted

for a constitutionally proscribed reason.

37

Thus, in City of Mobile v. Bolden,

supra, and White v. Regester, 412 U.S.

755 (1973) the Court held that multi-mem

ber or at-large election districts are a

constitutional voting mechanism. When

such a system, neutral on its face, "is

subverted to invidious purposes," it

violates the Fourteenth Amendment. Rogers

v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 621-22 ( 19 82)?

White v. Regester, supra, 412 U.S. at

765-70. Similarly, in Lassiter v.

Northampton County Bd. of El., 360 U.S.

45 ( 1959), this Court held that a State's

use of a literacy test to qualify voters

is consistent with the Fourteenth Amend

ment. Yet, in South Carolina v. Katzen-

bach, supra, the Court held that where

literacy tests "have been instituted with

the purpose of disenfranchising Negroes,

have been framed in such a way as to

f acil itate this aim, and have been

38

administered in a discriminatory fashion,"

1 iteracy tests violate the Constitution.

383 U.S. at 333-34.

In other words, even if Richardson v,

Ramirez is interpreted to authorize the

State of A1abama, for legitimate reasons,

to disenfranchise persons convicted of

non-felonies involving moral turpitude,

the case does not support such action when

taken for a constitutionally proscribed

purpose. Appellees allege and the Court

below found that the State acted out of

racial animus, which the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibits. Appellants contend

that the State acted out of wealth-based

or pol it ical animus, which are also

constitutionally forbidden justifications.

Appel 1 ants have alleged no constitution-

ally permissible reason for the disen

franchisement of non-felons, let alone a

compelling state purpose. Under these

39

circumstances, the Court must affirm the

Court of Appeals' conclusion that the

disenfranchisement clause violates the

Fourteenth Amendment.

V. THE TENTH AMENDMENT PROVIDES NO

PROTECTION FOR A STATE DISENFRAN

CHISEMENT MEASURE WHICH VIOLATES THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

Appellants argue that the State of

Alabama has broad power secured by the

Tenth Amendment to grant or deny the

suffrage. But "no State can pass a law

regulating elections that violates the

Fourteenth Amendment...." Williams V.

Rhodes, 393 U.S. 23, 29 (1968). The

Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth

Amendments "were specifically designed as

an expansion of federal power and an

intrusion on state sovereignty." City of

Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 179

(1980). Particularly in the area of

voting rights the Civil War Amendments

4 0

"supersede contrary exertions of state

power." South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383

U.S. at 325. The principles of Tenth

Amendment federalism articulated in

National League of Cities v. Usery, 426

D. S. 833 (1 976), do not constrain the

Fourteenth Amendment. Fitzpatrick v.

Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445, 451-56 (1976). See

also City of Rome v. United States, supra,

446 U.S. at 178-80 (National League of

Cities does not limit the Fifteenth

Amendment). In short, the Tenth Amendment

provides no independent justification for

a state disenfranchisement measure which

violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

VI. THE MISDEMEANANTS DISENFRAN

CHISEMENT CLAUSE VIOLATES THE VOTING

RIGHTS ACT.

As amended in 1982, section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act, 4 2 U.S.C. § 19 73(a)

bars the use of any "voting qualification

41

or prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure....which results in

a denial or abridgement of the right to

vote of any citizen of the United States

on account of race or color.” The section

prohibits not only official action taken

or maintained for a racially discrimina

tory purpose, but also any official action

that results in the impairment or denial

of the right to vote of any citizen on

account of race. United States v. Marengo

County Commission, 731 P. 2d 1546 (11th

Cir. 1984) appeal dismissed, 83 L.Ed.2d

311 (Nov. 5, 1984)(No. 84-243). Thus,

"discriminatory intent need not be shown

to establish a violation." Id. at 1564.

Section 2 plainly applies to State

restrictions on the right to register, as

well as to districting schemes that dilute

minority voting strength. Harris v.

Graddick, 593 F. Supp. 128, 132 (M.D. Ala.

4 2

1984). As the court below found, the

disenfranchisement of misdemeanants

disproportionately affects blacks (J. S.

at A - 1 1 ) . Consequently, a prima facie

case of a "voting qualification” which

results in a denial of the right to vote

on account of race is made out.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the decision

of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eleventh Circuit should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

JULIUS CHAMBERS

LANI GUINIER *

PENBA HAIR

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

RICHARD BRIFFAULT

Columbia University

School of Law

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10027

43

Dated:

Attorneys for the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educa

tional Fund, Inc.,

Amicus Curiae *

*Counsel of Record

J a n u a r y 1 , 1 9 8 5

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— >200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— -(212) 966-4177