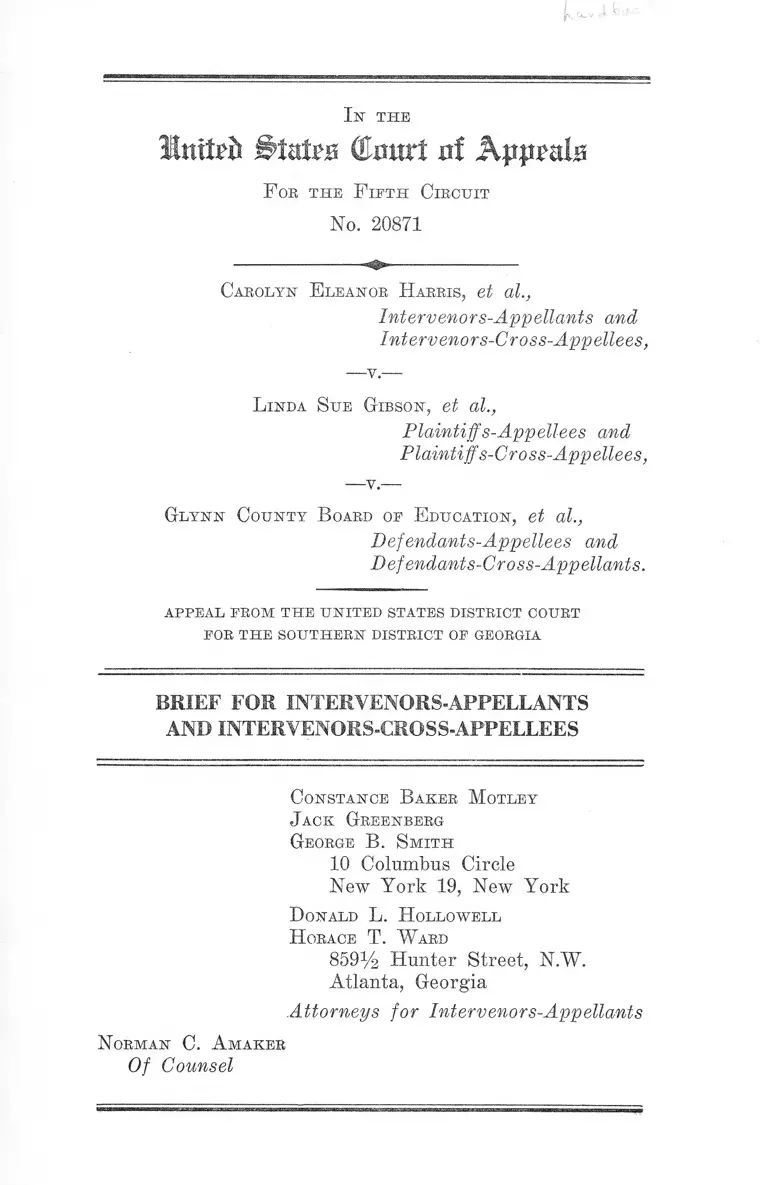

Harris v. Gibson Brief for Intervenors-Appellants and Intervenors-Cross-Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 31, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harris v. Gibson Brief for Intervenors-Appellants and Intervenors-Cross-Appellees, 1963. 283cfb6a-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1404561d-9ccc-4372-a6ed-843313d53a35/harris-v-gibson-brief-for-intervenors-appellants-and-intervenors-cross-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

United (to rt uf Appmhz

F oe t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 20871

Carolyn E leanor H arris, et al.,

Intervenors-AppeHants and

Interne,nors-Cr oss-Appellees,

— v .—

L inda S ue H ibson , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees and

Plaintiff s-Cross-Appellees,

Gl y n n C ounty B oard of E ducation , e t al.,

Defendants-Appellees and

Defendants-Cross-Appellants.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

AND INTERVENORS-CROSS-APPELLEES

C onstance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

George B . S m ith :

10 Columbus Circle

.New York 19, New York

D onald L. H ollowell

H orace T. 'Ward

859% Hunter Street, N.'W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Intervenors-Appellants

N orman C. A maker,

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PA G E

Statement of the Case ......................................... ......... 1

Specification of Errors ............................ ..................... 4

A r g u m e n t :

I. The “Pre-Trial Order” of the District Court

Is Appealable Under Section 1291 and Sec

tion 1292(a)(1) of Title 28, United States

Code.................................. ............................... 5

II. The District Court’s Order Wrongfully Re

quires That the Intervenors-Appellants Pur

sue State Remedies for Denial of the Federal

Right to Attend Desegregated Schools ........ 7

III. The Order Below Is Inconsistent With This

Court’s Holding in Stell v. Savannah-Chat-

ham County Board of Education....... ........... 9

IV. There Was No Justification for Delay in the

Desegregation of the Glynn County Schools .. 11

Conclusion ...................................................................... 13

A ppen d ix :

Ga. Code Ann. 32-910 ............................................... 15

Certificate of Service...... ........................................... ig

11

T able of Cases

page

Armstrong v. Board of Education of the City of Bir

mingham, 323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963) ...... 7,8,10,11

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962) ................................................. ..........8,12

Baltimore and Ohio R.R. Co. v. United Fuel Gas Co.,

154 F. 2d 545 (4th Cir. 1946) ................................ 5

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268 ................................ 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ....6, 7, 9,10,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 .................. 11

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U. S. 294 .......... 5

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(5th Cir. 1962) .............................................................8,12

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., 337 U. S.

541 ................................ ................................ ....... ....... 5

Cooper y . Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ...... ...................... .......... 6,11

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, Alabama, 322 F. 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1963) .... 11

Forgay v. Conrad, 6 How. (47 U. S.) 201..................... 5

Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 ............ .......... ..... . 7

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

246 F. 2d 913 (5th Cir. 1957), on second appeal, 272

F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) ........................................... 8

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683 ................................... ...................... ......6,11

Harris v. Gibson, 322 F. 2d 782 (5th Cir. 1963) ...... 5, 6,11

Hodges v. Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co., 310 F. 2d

438 (5th Cir. 1962) 5

PA G E

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm Beach

County, Florida, 258 F. 2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) .....8,11

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F . 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ........................................... 12

Kennedy v. Lynd, 306 F. 2d 222 (5th Cir. 1962) ....... 5

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ....................................... 7

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370

(5th Cir. 1960) ....................................... ..................... 8

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 .......... 7, 8

Missouri-Ivansas-Texas R.R. Co. v. Randolph, 182 F. 2d

996 (8th Cir. 1950) ..... ..................... ........................... 6

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167 ..................................7, 8

Northcross v. Board of Education, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th

Cir. 1962) ............................ ...................................... 12

Pan American World Airways v. Flight Engineers’

Int’l Ass’n, 306 F. 2d 840 (2nd Cir. 1962) .............. 6

Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690 (5th Cir. 1957) .......... 11

Sears, Roebuck and Company v. Mackey, 351 U. S. 427 .. 5

Sims v. Greene, 160 F. 2d 512 (3rd Cir. 1947) .......... 6

Stack v. Boyle, 342 IT. S. 1 ........ ............................ ...... 5

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963) ................. 9,10,11,12

Swift and Co. v. Compania Colombiana, 339 U. S. 684 .. 5

United States v. Wood, 295 F . 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) ... 5

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 ..................6,11

Woods v. Wright, ----- F. 2d —— (5th Cir. May 22,

1963)

Ill

5

I n t h e

llntteb Btuttz (Emirt nf Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 20871

Carolyn E leanor H arris, et al.,

Intervenors-Appellants and

Intervenor s-Cross-Appellees,

L inda S u e G ibson , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees and

Plaintiff‘s-Cross-Appellees,

—v.—

Gl y n n C ounty B oard of E ducation , et al.,

Defendants-Appellees and

Defendants-Cross-Appellants.

appeal from t h e u n ited states district court

FO R T H E S O U T H E R N D IST R IC T OF GEORGIA

BRIEF FOR INTERVENORS-APPELLANTS

AND INTERVENORS-CROSS-APPELLEES

Statement of the Case

Unlike the usual and customary school desegregation

case, this action was instituted below by parents of white

pupils enrolled in the Glynn County, Georgia public school

system to enjoin the local Board of Education from volun

tarily commencing school desegregation by the transfer of

2

six Negro high school students from the Negro high school

to Glynn Academy, the white high school, in August 1963.

This action was commenced on August 27, 1963, one day

before the opening of school. On that day, the District

Judge issued a temporary restraining order without no

tice enjoining the proposed transfers. The parents of the

six minor Negro pupils intervened in the action to protect

their rights and to secure desegregation of the entire school

system.

Intervenors below (hereinafter intervenors-appellants)

are appealing from that part of an order of the District

Court entered on September 6, 1963 entitled “Pre-Trial

Order” (R. 55). That order, in effect, denied intervenors-

appellants’ motion to vacate the temporary restraining

order, thus barring the transfer of the six Negro pupils.

The order also referred the question of desegregation of the

Glynn County schools back to the Glynn County Board of

Education (hereinafter defendants-appellees) for exhaus

tion of an elaborate administrative procedure. Moreover,

the order below continued, in effect, a temporary restrain

ing order beyond the permissible statutory period making

it a preliminary injunction.

This case has been here before on a motion by the inter

venors-appellants for an injunction pending appeal. On

September 12, 1963 this court granted such a motion and

required defendants-appellees to transfer the six minor

Negro intervenors-appellants to the Glynn Academy be

ginning September 16, 1963 (R. 57). They have been trans

ferred.

On August 1, 1963 defendants-appellees announced plans

to commence desegregation of the schools of Glynn County,

Georgia during the 1963-64 school year by accepting the

transfer applications of the six minor Negro intervenors-

appellants. This intention was thwarted on August 27,

3

1963, the day before school opened, when plaintiffs-appel-

lees (parents of white pupils) obtained the temporary re

straining order. In their complaint (E. 1-21), plaintiffs-

appellees alleged that desegregation would be detrimental

to both races (see especially paragraphs 6-21 of their com

plaint, E. 5-16a) and asked for a preliminary and permanent

injunction, enjoining the operation of an integrated school

system in Glynn County or, in the alternative, a plan re

organizing the schools into a tertiary system—one part for

whites, another for Negroes, and a third for whites and

Negroes (E. 16a, 17).

On August 31, 1963 intervenors-appellants filed a com

plaint and motion for order to show cause praying the

court, inter alia, to allow them to intervene in the action,

to vacate and dissolve the temporary restraining order of

August 27, 1963, to require admission of the Negro students

to Glynn Academy, and to require the school board to sub

mit a plan for the reorganization of the entire school sys

tem on a nonracial basis (E. 29-31). They subsequently filed

a motion for preliminary injunction which is still pending

(E. 38).

No objection is made to that part of the order appealed

from permitting the intervenors-appellants to intervene

(E. 56). The order referring the whole matter of school

desegregation back to the school board cited an elaborate

state administrative and court procedure established by

Ga. Code Ann. §32-910 (see Appendix, p. 15, infra). Al

though the order ostensibly included a direction for the

formulation of a plan for reorganization of the Glynn

County schools “along nonracial lines” (E. 56), the only

specific requirement was that no transfer request be re

fused on the sole basis of race (E. 56). Thus, there was no

requirement to eliminate initial racial assignments, racial

attendance areas, or to desegregate teachers and other pro

4

fessional school personnel. Hearings were to be held by the

defendants-appellees, the school board, on the plan and the

plaintiffs-appellees given an opportunity to present evi

dence that desegregation would be detrimental to both

whites and Negroes (R. 57). After a decision by the school

board, an appeal would lie, under §32-910, to the State

Board of Education and, presumably, to the state courts.

All other matters were “held in abeyance” until these pro

cedures were completed (R. 58).

The intervenors-appellants immediately filed notice of

appeal and a motion with this court for an injunction pend

ing appeal. In granting such a motion on September 12,

1963, this court held that, “The ‘Pre-Trial Order’ of Sep

tember 6, 1963 was, in effect, the granting of a preliminary

injunction” (R. 61), as well as a “final” order (R. 62).

The orders of the district court were vacated and the six

minor Negro intervenors-appellants ordered into the Glynn

Academy (R. 63). All six entered the said school on Sep

tember 16, 1963 and are presently in attendance there.

Specification o f Errors

The district court erred in :

1. Enjoining the school authorities from transferring

the six Negro students to the Glynn Academy,

2. Referring the whole matter of school desegregation

back to the school board for elaborate state administrative

and court proceedings,

3. Permitting the contentions of the plaintiffs-appellees

that desegregation would be detrimental to both races to

delay the attendance of Negroes at the Glynn Academy,

5

4. In failing to require that the school hoard bring in

a plan for desegregation of the entire Glynn County school

system.

ARGUMENT

I

T he “ Pre-Trial O rder” o f the D istrict Court Is Ap

pealab le U nder Section 1 2 9 1 and Section 1 2 9 2 (a ) (1 )

of T itle 2 8 , U nited States Code.

Section 1291 of Title 28, United States Code, provides

that the courts of appeals shall have “jurisdiction of ap

peals from all final decisions of the district courts of the

United States.” The “final” decision clause has long been

given a practical rather than technical construction. Brown

Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U. S. 294, 306; For gay v.

Conrad, 6 How. (47 U. S.) 201, 202; United States v. Wood,

295 F. 2d 772, 778 (5th Cir. 1961); Baltimore and Ohio

R.R. Co. v. United Fuel Gas Co., 154 F. 2d 545, 546 (4th

Cir. 1946). Thus the “pre-trial order” of the district court

falls within the rule of United States v. Wood, supra, at

778, permitting appeals from an order “determining sub

stantial rights of the parties which will be irreparably lost

if review is delayed until final judgment. . . . ” 1

1 Other decisions have permitted appeals from orders not tech

nically final where irreparable harm would render worthless a

delayed appeal. Harris v. Gibson, 322 F. 2d 782 (5th Cir. 1963);

Woods v. W right,---- F. 2 d --------(5th Cir. May 22, 1963) ; Stack

v. Boyle, 342 U. S. 1, appeal possible from denial of motion to

reduce bail ; Sw ift and Co, v. Compania Colombiana, 339 U. S. 684,

appeal from an order vacating the attachment of a ship in a libel

action for lost cargo; Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp.,

337, U. S. 541, appeal from the denial of a request to require

the plaintiff to give security for reasonable expenses and counsel

fees in a stockholder’s derivative action. See also Sears, Roebuck

and Company v. Mackey, 351 U. S. 427; Forgay v. Conrad, 6 How.

(47 IT. S.) 201; Kennedy v. Lynd, 306 F. 2d 222 (5th Cir. 1962) ;

Hodges v. Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co., 310 F. 2d 438 (5th

Cir. 1962).

6

The minor intervenors-appellants were irreparably-

harmed by being barred from the all-white Glynn Academy,

since the exclusion of Negroes from public schools solely

on the basis of race is a flagrant violation of their consti

tutional rights. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S.

483; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1; Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526; Coss v. Board of Education of the

City of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683.

The “pre-trial order” of September 6, 1963 was also

appealable as an order granting a preliminary injunction

under §1292(a)(l). Since that order in effect extended the

temporary restraining order of August 27 past the statu

torily permissible period, the temporary restraining order

became a preliminary injunction. Harris v. Gibson, supra

at 781, Sims v. Greene, 160 F. 2d 512 (3rd Cir. 1947) (a

temporary restraining order enjoining interference with

the plaintiffs as presiding bishop of a district of the African

Methodist Episcopal Church held a preliminary injunction

when continued past the statutorily permissible period);

Missouri-Kansas-Texas R. Co. v. Randolph, 182 F. 2d 996

(8tli Cir. 1950) (temporary restraining order enjoining the

cancellation of a collective bargaining agreement held a pre

liminary injunction when a motion to dissolve it was de

nied) ; Pan American World Airways v. Flight Engineers’

Int’l Ass’n, 306 F. 2d 840 (2nd Cir. 1962) (a temporary re

straining order against a strike which had twice been ex

tended held a preliminary injunction).

In Sims the court said (at page 517):

When a restraining order, purporting to be Tempo

rary’ is continued for a substantial length of time past

the period prescribed by §381 of 28 U. S. C. A. without

the consent of the party against which it issued and

without the safeguards prescribed by Eule 65(b) it

ceases to be a Temporary restraining order’ within

7

the purview of that section and becomes a preliminary

injunction which cannot be maintained unless the court

issuing it sets out the findings of fact and the conclu

sions of law which constitute the grounds for its action

as required by Buie 52(a).

II

The D istrict Court’s Order W rongfu lly R equires That

the Intervenors-A ppellants P ursue State Rem edies for

Denial o f th e Federal R ight to A ttend Desegregated

Schools.

It is now too clear for argument that the attendance by

Negro students at schools free of discrimination based

solely on color is a federal right. Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, supra; McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S.

668, 10 L. Ed.. 2d 622, 626; Armstrong v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333, 336 (5th

Cir. 1963). Claims of denial of that right are entitled to

be adjudicated in the federal courts without first seeking

relief from state administrative bodies or courts. McNeese

v. Board of Education, supra; Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S.

167,183; Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903, aff’g 142 F, Supp.

707, 713 (M. D. Ala. 1956); Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268,

274; Armstrong v. Board of Education, supra at 336, 337;

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957). The Su

preme Court made this principle clear in McNeese where

Negro students sought to enter desegregated schools in

Illinois (supra at pp. 624-625):

“We have previously indicated that relief under the

Civil Rights Act may not be defeated because relief

was not first sought under state law which provided a

remedy. We stated in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167,

183, 5 L. ed. 2d 492, 503, 81 S. Ct. 473:

8

‘It is no answer that the State has a law which if

enforced would give relief. The federal remedy is

supplementary to the state remedy and the latter

need not be first sought and refused before the fed

eral one is invoked.’

(At pp. 626, 627)

“It is immaterial whether respondents’ conduct is

legal or illegal as a matter of state law. Monroe v.

Pape, supra (365 TJ. S. 171-187). Such claims are en

titled to be adjudicated in the federal courts.”

This language was cited with approval by this Court in

Armstrong v. Board of Education, supra at 336, 337. Mc-

Neese, however, only added support to previous decisions of

this court holding it unnecessary, in a school desegregation

case, to exhaust state administrative remedies before seek

ing relief in the federal courts. Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 308 F. 2d 491, 499-501 (5th Cir. 1962);

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862, 869

(5th Cir. 1962); Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction,

277 F. 2d 370, 372, 373 (5th Cir. 1960); Holland v. Board

of Public Instruction of Palm Beach County, Florida, 258

F. 2d 730, 732 (5th Cir. 1958); Gibson v. Board of Public

Instruction' of Dade County, 246 F. 2d 913, 914 (5th Cir.

1957), on second appeal 272 F. 2d 763, 767 (5th Cir. 1959).

The pre-trial order of the district court flies in the face

of these decisions by referring the issue of school desegre

gation back to the defendant-appellee school board for ex

tended proceedings under Ca. Code Ann. 32-910. Not only

does §32-910 require hearings and a decision by the school

board, but it also requires an appeal to the State Board of

Education and, presumably, to the state courts. The order

of the district court is no less a requirement of exhaustion

because the transfer applications of the intervenors-appel-

lants were accepted by the school board. The crucial factor

9

is that the district court has required the intervenors-ap-

pellants to begin anew in their quest for constitutional

rights and to begin with state remedies.

Ill

The Order Below Is Inconsistent With This Court’s

Holding in Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of

Education.

In Stell v. Savannah-CIiatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963), a suit by Negro students

seeking to desegregate the schools of Savannah-Chatham

County, Georgia, the trial court permitted intervention by

certain white persons whose only purpose was to introduce

evidence to support the thesis that compliance with Brown

v. Board of Education, supra, would be detrimental to both

white and Negro students. On the basis of this evidence

the motion by the Negro students for a preliminary injunc

tion was denied. In reversing the lower court, this court

held (at p. 247):

“ . . . [T]he trial court permitted an intervention by

parties whose sole purpose for intervening was to

adduce proof as a factual basis for an effort to ask the

Supreme Court to reverse its decision in Brown v.

Topeka Board of Education. The court then permitted

evidence in support of this approach by the inter-

venors, and denied the appellants’ motion for prelimi

nary injunction solely on the basis of such evidence,

which, briefly stated, tended to support the thesis that

compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision would

be detrimental to both the Negro plaintiffs and to

white students in the Savannah-Chatham County

School system.

The district court for the Southern District of

Georgia is bound by the decision of the United States

10

Supreme Court, as we are. Unless and until that court

overrules its decision in Brotvn v. Topeka, no trial court

may, upon finding the existence of a segregated school

system, refrain from acting as required by the Su

preme Court merely because such district court may

conclude that the Supreme Court erred either as to its

facts or as to the law.

See also Armstrong v. Board of Education, supra at 219,

220, rejecting a similar contention.

Here, seeking to forestall the imminent desegregation of

the Glynn Academy, plaintiffs-appellees filed an original

complaint, making the same allegations as those found in

St ell. (See particularly paragraphs 6-21 of their complaint,

R. 5-16a.) On the basis of these allegations the court below

issued a temporary restraining order (R. 21) and a pre

trial order requiring that the plaintiffs-appellees be given

“full opportunity” to introduce evidence in support of their

contentions (R. 57). Just as it was error for the district

court to deny the motion for preliminary injunction and

delay desegregation of schools in Stell on the basis of such

allegations, it was error here.

11

IV

There Was No Justification for Delay in the Desegre

gation of the Glynn County Schools.

In 1954, the United States Supreme Court announced for

the first time that the operation of public schools on a ra

cially segregated basis deprived Negro children of their con

stitutional rights. Brown v. Board of Education, supra. In

1955, the court stated that while administrative problems

might be taken into consideration, the public schools must

be desegregated “with all deliberate speed.” Brown v.

Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294. In Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, the Supreme Court clarified the

concept of all deliberate speed by reaffirming the principle

that deprivation of constitutional rights called for prompt

rectification and emphasizing that plans or programs for

desegregation of public schools which might have been

sufficient eight years ago might not be so today. See also

Goss v. Board of Education, supra at 636. This court has

consistently followed these principles by refusing on

several occasions to delay integration of schools. Harris v.

Gibson, supra; Armstrong v. Board of Education, supra;

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

Alabama, 322 F. 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1963); Stell v. Savannah-

Chatham County Board of Education, supra.

By accepting the transfer applications of the six Negro

students, the defendants-appellants recognized that no

administrative problems justified further delay in school

desegregation. Primary responsibility for desegregation

was in their hands. Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

294, 298; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7; Armstrong v.

Board of Education, supra at 337; Davis v. Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 63, 64; Holland v. Board of Public Instruc

tion, supra at 733; Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690, 693

12

(5th Cir. 1957). Since the district court issued its orders

on the basis of allegations unconnected with administrative

problems, it abused its discretion in overruling the decision

of the school board. St ell v. Savannah-Chatham County

Board of Education, supra.

Delay would be unjustified even if the reorganization

plan called for by the district court required desegregation.

It does not, however, do this. The pre-trial order of the

district court stated (B. 56):

Defendants shall prepare and submit to the court

with reasonable promptness a plan for reorganization

of the schools subject to their jurisdiction along non-

racial lines which shall not exclude from transfer

between schools any applicant, therefore (sic), solely on

the grounds of color or other criterion unrelated to the

educational and physical advancement and well being

of the children concerned.

The only provision clearly required in the plan is one

that no transfer request be refused on the sole basis of

race. But the acceptance of transfer requests cannot serve

as a means of implementing desegregation for, “Negro

children cannot be required to apply for that to which they

are entitled as a matter of right.” Northcross v. Board of

Education, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962). Without a provi

sion eliminating initial assignments and school attendance

lines on the sole basis of race, the plan ordered by the

lower court could not meet constitutional requirements.

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, supra at 499;

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, supra at 869;

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis,

supra at 823; Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexan

dria, 278 F. 2d 72, 76 (4th Cir. 1960).

13

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the decision below should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

C onstance B aker M otley

J ack Greenberg

George B . S m it h

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

D onald L . H ollo w ell

H orace T. W ard

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Intervenors-Appellants

N orman C. A maker

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Gta. Code A n n . 32-910 Powers of County or other local

boards as school court.

The county, city or other independent board of education

shall constitute a tribunal for hearing and determining any

matter of local controversy in reference to the construction

or administration of the school law, with power to summon

witnesses and take testimony if necessary, and when such

board has made a decision, it shall be binding on the par

ties: Provided however, either party shall have the right

to appeal to the State Board of Education, which appeal

shall be made through the local superintendent of schools

in writing and shall distinctly set forth the question in dis

pute, the decision of the local board, a transcript of the

testimony and other evidence adduced before the board

certified as true and correct by the local superintendent,

and a concise statement of the reasons why the decision be

low is complained of. This section shall apply to all county,

city, or independent school systems in this State, regard

less of when created. The State Board shall provide by

regulation for notice to the parties and hearing on the

appeal. (Acts 1919, p. 324, 1947, pp. 1189, 1190; 1961, p.

39.)

16

Certificate o f Service

This is to certify that on the 31st day of January, 1964

I served copies of the foregoing Brief for Intervenors-Ap-

pellants upon Attorney for Plaintiffs-Appellees, Alan B.

Smith, P. 0. Box 518, Brunswick, Georgia and upon At

torney for Defendants-Appellees, B. N. Nightingale, P. 0.

Box 1496, Brunswick, Georgia, by depositing copies ad

dressed to them as indicated herein in the United States

Mail, airmail, postage prepaid.

Attorney for Intervenors-Appellants

3 8