Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

November 20, 1972

52 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1972. f6bd2ddd-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/141f57f7-71cb-4c21-ae92-8dcd96710e95/petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

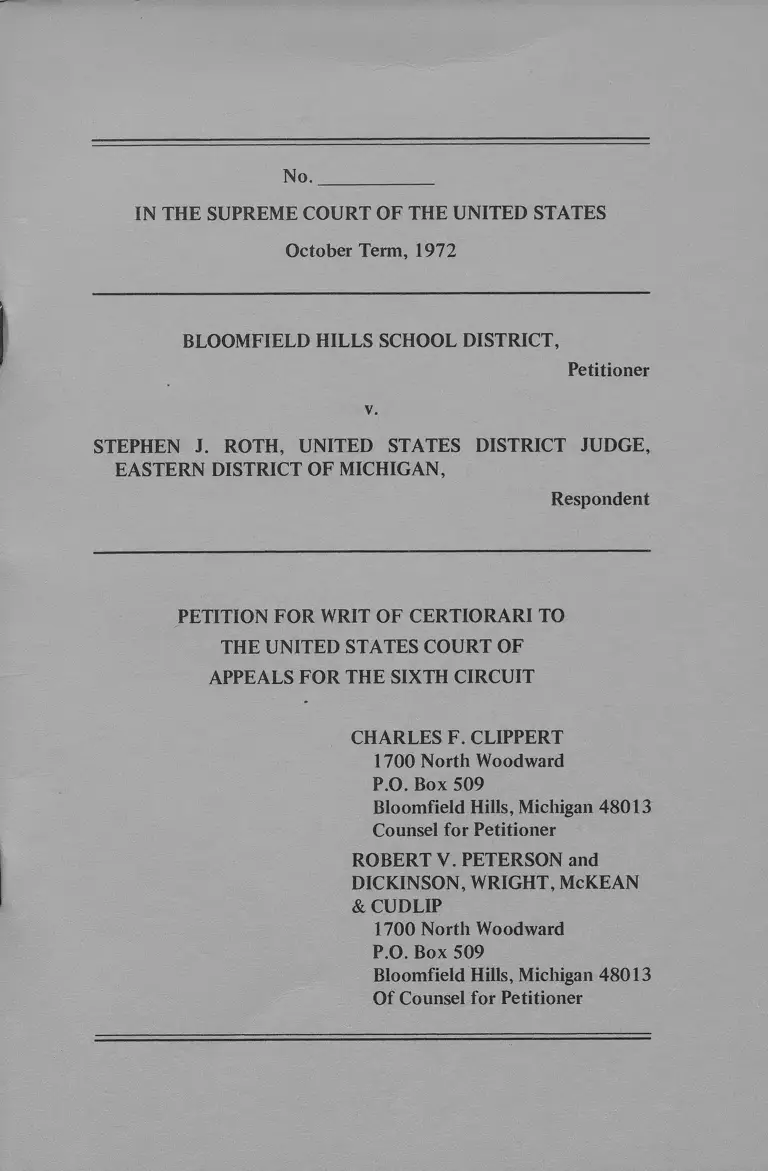

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1972

BLOOMFIELD HILLS SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Petitioner

v.

STEPHEN J. ROTH, UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE,

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN,

Respondent

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

CHARLES F. CLIPPERT

1700 North Woodward

P.O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Counsel for Petitioner

ROBERT V. PETERSON and

DICKINSON, WRIGHT, McKEAN

& CUDLIP

1700 North Woodward

P.O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Of Counsel for Petitioner

■ ■

‘

1

INDEX

Page

OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW . . . . . . . . . . . ----- . . . 1

JURISDICTION......... ......................................... .. 1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............................................. 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES AND

RULES INVOLVED .......................................................... 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................... .. 3

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT . . . ------------ - 4

I. The District Court Deprived Petitioner of Due Process

of Law by Subjecting Petitioner to the June 14, 1972

Ruling and Order in Bradley . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

II. The Imposition of the June 14 Ruling and Order

in Bradley Upon Petitioner Is Jurisdictionally Defect

ive Because of the District Court’s Failure To

Convene a Three-Judge Court in That Case ................ 6

III. The Court of Appeals Erred in Denying the Petition

fo r Issuance o f a W rit o f Mandamus and/or

Prohibition ................................................................... .. 8

CONCLUSION . . . . . . . . ----- . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

APPENDIX .................. ................... .. la

11

CITATIONS

Page

CASES

Allen v. State Board o f Elections 393 U.S. 544 (1969) . . . 6

Armstrong v. Manzo 380 U.S. 545 (1965) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.D.

Mich., 1 9 7 1 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ___ . . . . . . 3

Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al. 345 F. Supp. 914 (E.D.

Mich., 1972)............... 1,3

Board o f Managers o f Arkansas Training School v. George

377 F.2d 228 (C.A. 8, 1967) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Jenkins v. McKeithen 395 U.S. 411 (1969) ......................... 5

Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez 372 U.S. 144 (1963) . . . . . 6

Morrow v. District o f Columbia 417 F.2d 728 (C.A. D.C.,

1969) ............... 9

Muskrat v. United States 219 U.S. 346 (1911) . . . . . . . . . 9

Phillips v. United States 312 U.S. 246 (1941) .................... 6

Roche v. Evaporated Milk Association 3 19 U.S. 21 (1943) 8

Sailors v. Kent Board o f Education 387 U.S. 105 (1967) . 7

Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge 295 U.S. 89 (1934) . . 7

Stratton v. 56 ZowA S'. IV. Co. 282 U.S. 10 (1930) . . . 8

United States ex rel McNeill v. Tarumianz 242 F.2d 191

(C.A. 3, 1957) . . . . . . . . ___ . . . . . . . . . . ........ ............. 7

L.B. Wilson, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission

170 F.2d 793 (C.A. D.C., 1948) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Ill

CONSTITUTIONS Page

Art. VIII, Sec. 2, Mich. Const. 1963 ...................................... 2, 6

STATUTES

Title 28, U.S.C. §1254(1) ................... 2

Title 28,U.S.C. §1651 .......................................... 2 ,4

Title 28, U.S.C. §2281 ........................ .............................. 2, 6, 7, 8

MCLA 38.71, etseq. ............................................................... 7

MCLA 38.91 .......................... 2 ,7

MCLA 340.1,et seq............... 7

MCLA 340.77 ............................................................ • ........... 2 ,7

MCLA 340.352 .............................................• ........................ 2, 5

MCLA 340.356 ....................................................................... 2, 6

MCLA 340.569 .................. ................................................... 2, 7

MCLA 340.575 ....................................................................... 2, 7

MCLA 340.583 ....................................................................... 2> 7

MCLA 340.589 ....................................................................... 2, 6

MCLA 340.614 ............. 2 ,7

MCLA 340.882 ................................................................ .. 2, 7

MCLA 423.201, et seq.............................................................. 7

MCLA 423.209 ..................................................................... • 2 ,7

COURT RULES

Rule 21, F.R.A.P...................................................................... 2 ,6 ,8

Rule 19, F.R.C.P....................................................................... 2 ,4

1

N o .___________

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1972

BLOOMFIELD HILLS SCHOOL DISTRICT,

v.

STEPHEN J. ROTH, UNITED STATES

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN,

Petitioner,

DISTRICT JUDGE,

_______Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

The petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari be issued to review

an Order of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Cir

cuit entered in this proceeding.

OPINIONS AND ORDERS BELOW

The June 14 Ruling and Order of the District Court in Bradley,

et al. v. Milliken, et al. ( “Bradley”), which gave rise to the Petition

for Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition referred to below is re

ported at 345 F.Supp. 914 (E.D. Mich., 1972). The Ruling and

Order appears in the Appendix (10a to 20a).[ 1 ]

The Court of Appeals entered an Order on July 17, 1972 deny

ing p e t i t io n e r ’s application for Writ of Mandamus and/or

Prohibition. An Order denying Petition for Rehearing was enter

ed by the Court of Appeals on August 24, 1972. Neither Order has

been reported. Each order appears in the Appendix (21a and 31a).

JURISDICTION

The Order of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit denying

petitioner’s application for Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition

was entered on July 17, 1972. A timely petition for rehearing was

denied on August 24, 1972, and this petition for certiorari was

filed within 90 days of that date. This Court’s jurisdiction is in-

^ Parenthetical page references followed by the letter “a” refer to the

page of the printed Appendix hereto.

2

voked under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Did the District Court deprive petitioner of due process of

law and thereby usurp the jurisdiction vested in it by including

petitioner in its June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order in Bradley in dis

regard of the facts that petitioner was not a party to that action

and has never been found to have committed any act of de jure

segregation?

II. Did the District Court usurp the jurisdiction exclusively

vested by Title 28, U.S.C. §2281 in a United States District Court

of three judges by entering the June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order in

Bradley which restrains the enforcement, operation and execution

of various Michigan statutes?

III. Did the Court of Appeals err by denying the petition for

issuance of a writ of mandamus and/or prohibition?

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS, STATUTES

AND RULES INVOLVED

This case involves the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States; 62 Stat. 944, 63 Stat. 102, 28 U.S.C. § 1651(a);

62 Stat. 968, 28 U.S.C. §2281; Rule 21 of the Federal Rules of

Appellate Procedure; and Rule 19 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure. These are reprinted in pertinent part in the Appendix

at 32a to 33a.

Reference is made in this petition to the following provisions of

the Michigan School Code of 1955 which are reprinted in the

Appendix in pertinent part at 23a to 25a: MCLA 340.77; MCLA

3 4 0 .3 5 2 ; MCLA 340.356; MCLA 340.569; MCLA 340.575;

MCLA 3 4 0 .5 8 3 ; MCLA 340.589; MCLA 340.614; MCLA

340.882.

Reference is also made in this petition to Article VIII, Section 2

of the Michigan Constitution of 1963; MCLA 38.91 and MCLA

423.209. These are reprinted in pertinent part in the Appendix

at 33a to 34a.

3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioner is a school district located in Oakland County, Mich

igan, organized and existing under the Constitution and laws of

the State of Michigan. It is a body corporate under the law of

Michigan with independent legal status and possesses broad powers

with respect to educating approximately 9300 public school child

ren within its geographical boundaries.

On September 27, 1971, the Hon. Stephen I. Roth, U.S. Dis

trict Judge, issued a Ruling on Issue of Segregation in Bradley, et

al. v. Milliken, et al, (338 F.Supp. 582, 594, [E.D. Mich., 1971])

finding a “de jure segregated school system In operation in the

City of Detroit.” On June 14, 1972, Judge Roth entered an Order

in Bradley denominated Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order

for Development of Plan of Desegregation (345 F.Supp. 914 [E.D.

Mich., 1972]) which, inter alia, mandates pupil reassignment to

accomplish desegregation of the Detroit public schools within a

geographical area encompassing Detroit and some 53 additional

school districts (13a).

The June 14 Ruling and Order includes petitioner within the

geographic area which the trial judge deemed requisite for the

achievement of a racial mix to correct the segregated condition

found by him to exist in the Detroit public schools (14a). Petition

er was included within such area notwithstanding the facts that:

(1) Petitioner is not and never has been a party to the proceedings

in which the holding of de jure segregation relating to the Detroit

schools was made or which considered the appropriateness of a

metropolitan remedy, and (2) no claim or finding has been made

in Bradley or any other action that petitioner has committed any

act of de jure segregation.

Furthermore, the June 14 Ruling and Order restrains petitioner

in the enforcem ent, operation or execution of the powers

conferred and the duties imposed upon it by the Constitution and

laws of the State of Michigan. Illustrations of such restraints and

the statutes with respect thereto are set forth in the Appendix (4a,

5a and 23a-25a).

On June 29, 1972, petitioner filed a Petition for Writ of Manda

mus and/or Prohibition (2a) in the Court of Appeals pursuant to

4

the All Writs Statute (28 U.S.C. § 1651). The petition was denied

without a hearing by an Order entered July 17, 1972 (21a). A

Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Hearing In Banc (22a)

was filed in the Court of Appeals on July 27, 1972. The Petition

for Rehearing was denied without a hearing on August 24, 1972

(31a).

On July 20, 1972, the U.S. District Court in Bradley made a

determination of finality as to certain orders entered therein, thus

enabling the parties to that cause to take an appeal. Petitioner, a

non-party, had no right to appeal in Bradley.

The appeal in Bradley was argued in the Court of Appeals on

August 24, 1972 and briefs have been submitted by the parties.

The Court of Appeals has not yet rendered its opinion.

Disposition of the appeal in Bradley may render this petition

moot. It is respectfully requested, therefore, that this petition for

writ of certiorari be held in abeyance pending final action by the

Court of Appeals in Bradley. Petitioner will promptly advise the

Court of its desire to press this petition or withdraw it, depending

upon such final action by the Court of Appeals.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

L THE DISTRICT COURT DEPRIVED PETITIONER OF DUE

PROCESS OF LAW BY SUBJECTING PETITIONER TO

THE JUNE 14, 1972 RULING AND ORDER IN BRADLEY.

Petitioner is subjected to the June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order in

Bradley even though it is not and never has been a party to

Bradley. No claim or finding of de jure segregation has been made

against it. As a non-party, petitioner has had no opportunity to

examine or cross-examine any witnesses in Bradley or present

evidence or oral argument therein.

The naked inclusion of petitioner within the ambit of the June

14 Ruling and Order in Bradley contravenes Rule 19 F.R.C.P. but,

more importantly, is a brazen denial of petitioner’s right to

fundamental due process.

“The due process clause of the Fifth Amendment provides that

no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without

5

due process of law. An essential element of due process is an

opportunity to be heard before the reaching of a judgment. By

due process of law is meant ‘a law, which hears before it

condemns; which proceeds upon inquiry, and renders judgment

only after tr ia l’ Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward,

U.S. 1819, 4 Wheat. 518, 581, 4 L.Ed. 629 (Webster’s argu

ment). As said in Galpin v. Page, U.S. 1873, 18 Wall. 350, 368,

21 L.Ed. 959: Tt is a rule as old as the law, and never more to

be respected than now, that no one shall be personally bound

until he has had his day in court, by which is meant, until he

has been duly cited to appear, and has been afforded an oppor

tunity to be heard. Judgment without such citation and oppor

tunity wants all the attributes of a judicial determination; it is

judicial usurpation and oppression, and never can be upheld

where justice is justly administered.’ (Italics supplied).” L.B.

Wilson, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission, 170 F.2d

793, 802 (C.A. D.C., 1948)

“A fundamental requirement of due process is The opportun

ity to be heard.’ *** It is an opportunity which must be granted

at a meaningful time and in a meaningful manner.” Armstrong

v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545, 552 (1965)

“We have frequently emphasized that the right to confront

and cross-exam ine witnesses is a fundamental aspect of

procedural due process.” Jenkins v. McKeithen, 395 U.S. 411,

428(1969)

The June 14 Ruling and Order in Bradley constitutes a usurpation

of judicial power over petitioner. Consequently, the proceedings in

Bradley are void as to petitioner.

School districts in Michigan, which are recognized in the 1963

Michigan Constitution and established by the legislature, are

corporate bodies having independent legal status. MCLA 340.352

(24a). Petitioner, therefore, is independent of other defendants in

Bradley and is independently entitled to fundamental due process.

The subjection of petitioner, a non-party, to the ruling in

Bradley and, indeed, the imposition of a host of burdens upon

petitioner without any hearing or finding with respect to petition

6

er presents an extreme departure from the accepted and usual

course of judicial proceedings. The District Court’s departure was

sanctioned by the Court of Appeals through its refusal to even

grant a hearing on petitioner’s Rule 21 F.R.A.P. Petition for Writ

of Mandamus and/or Prohibition in that Court. The failure to

afford fundamental due process in these proceedings calls for this

Court’s exercise of its power of supervision.

II. THE IMPOSITION OF THE JUNE 14 RULING AND

ORDER IN BRADLEY UPON PETITIONER IS JURIS-

D IC T IO N A L L Y D EFECTIV E BECAUSE OF THE

DISTRICT COURT’S FAILURE TO CONVENE A THREE-

JUDGE COURT IN THAT CASE.

Reduced to its essence, Title 28 U.S.C. §2281 prohibits a one-

judge district court from enjoining the enforcement, operation or

execution by state officials of state statutes of general application

upon the ground that such statutes violate the Constitution of the

United States. The purpose of §2281 is “to prevent a single fed

eral judge from being able to paralyze totally the operation of an

entire regulatory scheme.. .by issuance of a broad injunctive order’’

Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 154 (1963), and to

provide “procedural protection against an improvident state-wide

doom by a federal court of a state’s legislative policy,” Phillips v.

United States, 312 U.S. 246, 251 (1941). While it is true that

§2281 must be strictly construed (Allen v. State Board o f Elec

tions, 393 U.S. 544, 561 [19691), all of the statutory requisites

were present in Bradley when the June 14 Ruling and Order was

issued.

The June 14 Ruling and Order in Bradley interdicts petitioner

in the enforcement, operation or execution of powers conferred

and duties imposed upon it by the 1963 Constitution and statutes

of Michigan. Illustrative of the injunctive effect of that Order are

the restraints imposed upon petitioner in carrying out the follow

ing responsibilities:

(a) The provision of educational opportunities to resident

pupils within the school district. Art. VIII, Sec. 2, Const.

1963; MCLA 340.356, 340.589. (See, 13a).

(b) The employment and allocation of teaching and adminis

7

trative staff to educate resident pupils upon terms satis

factory to the school district. MCLA 340.569, 423.209,

38.91. (See, 15a).

(c) The construction, expansion and use of school facilities.

MCLA 340.77. (See, 16a).

(d) The establishment of curriculum, activities and standards

o f conduct and providing for the safety of students,

faculty, staff and parents within the school district. MCLA

340.575, 340.583, 340.614, 340.882. (See, 16a).

The effect of the June 14 Ruling and Order upon statutes of

statewide application within the “desegregation area” is well

summarized in the interim report filed by the Michigan Super

intendent of Public Instruction in the District Court in Bradley

(29a, 30a).

It is clear that the June 14 Ruling and Order enjoins statutes of

statewide application rather than statutes which are local in

application. Sailors v. Kent Board o f Education, 387 U.S. 105

(1967). The school board of petitioner is composed of “state

officers” within the meaning of §2281 because the board is

charged with the duty of enforcing policies of statewide concern

as set forth in the 1963 Michigan Constitution, the Michigan

School Code of 1955 (MCLA 340.1 et seq.), Teachers’ Tenure Act

(MCLA 38.71 et seq.) and Public Employment Relations Act

(MCLA 423.201 et seq.) within the geographical Emits of each

school district. See, Spielman Motor Sales Co. v. Dodge, 295 U.S.

89 (1934).

The June 14 Ruling and Order in Bradley is predicated upon a

finding that the Michigan statutory educational structure is un

c o n s titu tio n a l. I t would be a “contradiction o f reason, a

usurpation o f power” to attempt to enjoin the enforcement of a

statute and at the same time not pass upon the constitutionality of

the statute. United States ex rel. McNeill v. Tarumianz, 242 F.2d

191, 195 (C.A. 3, 1957); Board o f Managers o f Arkansas Training

School v. George, 377 F.2d 228, 231 (C.A. 8, 1967).

Clearly, it is a “contradiction of reason” to restrain petitioner

by the June 14 Ruling and Order from the enforcement, operation

8

and execution of the powers granted to it under the 1963 Mich

igan Constitution and nonsegregative statutes of the State of Mich

igan, thereby nullifying the Michigan educational system as

defined by legislative enactments and not pass upon the cons

titutionality o f such legislative enactments. Under the mandate of

§2281, only a three-judge district court may determine the cons

titutionality of such laws, enforcement of which is interdicted in

the one-judge June 14 Ruling and Order.

An Order entered by a single district judge where a three-judge

court should have been convened is void as being beyond the

court’s jurisdiction. Stratton v. St. Louis S.W. Ry. Co., 282 U.S.

10 (1930). The June 14 Ruling and Order was entered without

jurisdiction in the District Court and therefore such an order

cannot be binding upon petitioner. It constitutes a departure from

the accepted and usual course of judicial proceedings. The Court

of Appeals sanctioned such a departure by the District Court

through its refusal even to grant a hearing on petitioner’s Rule 21

F.R.A.P. Petition for Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition. The

failure to set aside the June 14 Ruling and Order in Bradley, as it

applied to petitioner, calls for this Court’s exercise of its power of

supervision.

HI. THE COURT OF APPEALS ERRED IN DENYING THE

PETITION FOR ISSUANCE OF A WRIT OF MANDAMUS

AND/OR PROHIBITION.

The Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition sought by petitioner

in the Court of Appeals is the writ traditionally used to confine an

inferior court to a lawful exercise of its prescribed jurisdiction.

Roche v. Evaporated Milk Association, 319 U.S. 21, 26 (1943). By

the June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order in Bradley, the District Court

has exceeded its jurisdiction in two respects:

(a) Petitioner has never been a party to the proceedings in

Bradley. No claim or finding has been made with respect to

petitioner in that action. Petitioner has been afforded no hear

ing. Absent these basic requirements of due process, the District

Court is without jurisdiction over petitioner.

(b) The June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order enjoins the oper

ation of numerous provisions of state law on the ground of the

9

unconstitutionality thereof. The one-judge District Court was

without jurisdiction to enter such an Order.

The District Court’s failure to afford due process to petitioner is

of vital concern not only to petitioner but to every school district

in Michigan and the pupils, teachers, staff and residents thereof. A

m a tte r o f such “ pub lic im portance” makes this a “case

appropriate for the extraordinary writs.” Morrow v. District o f

Columbia, 417 F.2d 728, 736, 737 (C.A. D.C., 1969).

Notwithstanding the foregoing, petitioner is subjected to the

June 14 Ruling and Order in Bradley. This novel and unprecedent

ed usurpation of judicial power by the District Court was un

checked by the Courrt of Appeals in proceedings brought by peti

tioner before it. This Court, therefore, should grant the within

petition to the end that judicial power in these proceedings once

again becomes “the power of a court to decide and pronounce a

judgment and carry it into effect between persons and parties who

bring a case before it for decision. ” Muskrat v. United States, 219

U.S. 346, 356 (1911) (emphasis supplied).

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above (but subject to the request set

forth in the STATEMENT OF THE CASE to hold this petition in

abeyance), petitioner prays for the issuance of a writ of certiorari

to the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

CHARLES F. CLIPPERT

1700 North Woodward

P.O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Counsel for Petitioner

ROBERT V. PETERSON and

DICKINSON, WRIGHT, McKEAN & CUDLIP

1700 North Woodward

P.O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Of Counsel for Petitioner

APPENDIX

la

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Petition for Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition . . . . . 2a

Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for

Development of Plan of Desegregation (Exhibit A

to Petition)........................ 10a

Letter dated July 12, 1972 supplementing Petition . . . . 19a

Order entered July 17, 1972 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21a

Petition for Rehearing and Suggestion for Hearing

In Banc ........................................ 22a

Order Denying Petition for Rehearing entered

August 24, 1972 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31a

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Rules Involved . . 32a

2a

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BLOOMFIELD HILLS SCHOOL DIS

TRICT,

Petitioner

vs.

STEPHEN J. ROTH, UNITED

STATES DISTRICT JUDGE,

Respondent

No. 72-1651

PETITION FOR WRIT OF MANDAMUS

AND/OR PROHIBITION

NOW COMES Bloomfield Hills School District, a Michigan body

corporate, Petitioner, and petitions this Court, pursuant to the All

Writs Statute (28 U.S.C. § 1651), to issue a writ of mandamus

and/or prohibition directing Respondent Stephen J. Roth, Judge

of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of

Michigan, to:

(i) Delete the geographical area encompassed by Petitioner’s

boundaries from the “desegregation area described in Paragraph

II A of Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling on Desegregation Area

and Order for Development of Plan of Desegregation! (“June 14,

1972 Ruling and Order”) in Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al., Civil

Action No. 35257, United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Michigan, Southern Division; and

(ii) Refrain from enforcing each provision of Respondent’s

June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order which restrains Petitioner from

exercising the powers conferred and discharging the duties

imposed upon it by the 1963 Constitution and statutes of the

State of Michigan.

FACTS SUPPORTING THIS PETITION

1. Petitioner is a Michigan school district classified by the

Michigan School Code of 1955 (MCLA §§ 340.1, et secj.) as a

1 See copy attached as Exhibit A.

3a

fourth class district. Based upon data collected for the 1971-72

school year, Petitioner has a pupil enrollment of 9,353 students.

Approximately 45.25% of these students are enrolled in K-6

elementary schools. In 1970-71, Petitioner ranked 45th in pupil

enrollment among the 527 K-12 local school districts in Michigan.

Approximately 86% of the taxable property in the school district

is residential and 80.5% of Petitioner’s school operating budget is

derived from local sources of revenue. Petitioner’s staff consists

of: (i) 42 instructional and non-instructional administrative

personnel; (ii) 474 teachers and teacher aides who are represented

by Bloomfield Hills Education Association and are employed

under a contract covering wages, hours and conditions of

employment which will expire on August 28, 1973; (iii) 236

support service employees who are represented by American

Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (Locals

1384A and 1883A) and are employed under contracts covering

wages, hours and conditions of employement which will expire on

August 31, 1973 and December 31, 1973. Petitioner owns 16

classroom school buildings located within the district and has a

bonded indebtedness at the date hereof of $22,930,000, having

maturities from July, 1972 through 1996.

2. Bradley v. Milliken was commenced on August 18, 1970, by

the filing of a complaint which alleged the unconstitutionality of a

Michigan statute which was applicable only to the City of Detroit

school district and further claimed that plaintiffs’ constitutional

rights were violated because of the segregated pattern of pupil

assignments and racial identifiability of schools within the City of

Detroit school system. The complaint has never been amended and

at no time have the pleadings alleged that any school system other

than the Detroit system has failed to maintain a unitary system of

schools. A trial on the question of de jure segregation in the

Detroit schools was held in Respondent’s court and concluded on

July 22, 1971. On September 27, 1971, Respondent entered his

Ruling on Issue of Segregation which was limited to the finding

that illegal segregation exists in the public schools of the City of

Detroit. Plans of desegregation involving only the Detroit schools

as well as plans involving the metropolitan area school districts

were subsequently filed with Respondent. Respondent received

evidence from the original parties and intervenors relating to such

plans. New intervenors (certain school districts, not including

4a

Petitioner) participated in the proceedings on the restricted basis

outlined in Respondent’s March 15, 1972 Order. On March 24,

1972, Respondent ruled that he could properly order a

metropolitan plan to accomplish desegregation of the Detroit

schools. On June 14, 1972, Respondent entered his Ruling and

Order. That Order includes Petitioner within the geographic area

that Respondent deemed necessary to achieve the racial mix

required to correct the segregated conditions he found to exist in

the Detroit schools.

3. Petitioner is not and never has been a party to the

proceedings in which the holding of de jure segregation relating to

Detroit was made or which considered the appropriateness of a

tri-county remedy, nor has any claim ever been made tnat

Petitioner has commited any act of de jure segregation.

4. A motion to join Petitioner, together with other school

districts in the tri-county area, as a party defendant, was filed by

intervening defendants Denise Magdowski, et al., on July 12,

1971, but Respondent has refused to act upon their motion.

5. The first paragraph of Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of Ruling on

Desegregation Area and Development of Plan specifically states

that Respondent “has taken no proofs with respect to . . . the

issue of whether, with the exclusion of the City of Detroit school

district, such school districts [all 86 school districts, including

Petitioner, located within Wayne, Oakland and Macomb Counties!

have commited acts of de jure segregation.”

6. Among the powers conferred and duties imposed upon

Petitioner by the Michigan School Code of 1955 are the following:

(i) To sue and be sued in its name, (ii) to purchase personal and

real property for educational purposes, (iii) to employ a

superintendent, administrative personnel and teachers for the

education of its pupils, (iv) to establish courses of studies and

select text books to be utilized therein, and (v) otherwise to

establish policies for the education of the pupils residing within its

corporate limits.^

2 See MCLA §§ 340.353; 340.77; 340.66; 340.569; 340.583; 340.882;

340.575; 340.578; 340.613; 340.614 as illustrative of the powers and duties

set forth.

5a

7. Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order restrains

Petitioner in the enforcement, operation or execution of the

powers conferred and the duties imposed upon it by the 1963

Constitution and statutes of the State of Michigan in the following

respects:

(a) The allocation of Petitioner’s staff or other services and

the expenditures therefore. (11 I C)

(b) The enrollment in and attendance at Petitioner’s schools

only of children who are residents, (11 II B, C, D, E)

(c) The employment of qualified teachers to educate

resident pupils upon terms satisfactory to Petitioner. ( f

II F, G)

(d) The use of Petitioner’s school facilities. (11 II H)

(e) The construction or expansion of school facilities. (11 II

I)

(f) The curriculum, activities and standards of conduct; the

dignity and safety of Petitioner’s students, faculty, staff

and parents. (11 II K)

Like restraints are imposed upon the other 53 school districts

included within Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order.

8. Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order restrains the

Michigan State Board of Education and the Superintendent of

Public Instruction in the enforcement, operation or execution of

the powers conferred and the duties imposed upon each of them

by the 1963 Constitution and statutes of the State of Michigan in

the following respects:

(a) The construction of new school facilities and the

expansion of existing facilities. (11 III)

(b) The training and use of faculty and staff and the

conduct of extra-curricular activities. (11 II L)

ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Did Respondent deprive Petitioner of due process of law

and thereby usurp the jurisdiction vested in him as a United States

6a

District Judge by subjecting Petitioner to his June 14, 1972 Ruling

and Order in disregard of the facts that Petitioner was not a party

to the action and was not found to have committed any act of de

jure segregation?

2. Did Respondent usurp the jurisdiction exclusively vested by

Title 28, USC § 2281 in a United States District Court of three

judges by entering the June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order which

restrains the enforcement, operation and execution of various

Michigan statutes?

REASONS WHY WRIT SHOULD ISSUE

I. As a non-party, Petitioner cannot appeal Respondent’s June

14, 1972 Ruling and Order. That order has immense impact upon

the 9,300 children being educated by Petitioner and upon the

770,000 other children being educated within the 54 districts the

order affects. The totally unknown effects which massive

tri-county busing may have upon the education and safety of these

children as well as the undeterminable cost in time and dollars of

the order’s implementation make this a matter of “public

importance” and a “case appropriate for the extraordinary writs.”

Morrow v. District o f Columbia, 417 F.2d 728 (C.A. D.C. 1969) at

736,737.

II. Petitioner seeks the writ traditionally used to confine an

inferior court to a lawful exercise of its prescribed jurisdiction.

Roche v. Evaporated Milk Association, 319 U.S. 21 (1943) at 26.

Petitioner is not and never has been a party to Bradley y.Milliken.

Only parties who have been properly subjected to a federal court’s

in personam jurisdiction, and those who have been shown to have

acted in concert with such parties, can be legally subjected to the

provisions of its injunctive orders. FRCP, Rule 65(d), specifically

states: “Every order granting an injunction. . .is binding only upon

the parties to the action, their officers, agents, servants,

employees, and attorneys, and upon those persons that act in

concert or participation with them. . . . ”

The evils prohibited by this provision of Rule 65 were

articulated by Judge Learned Hand in Alemite Manufacturing

Corporation v. Staff, 42 F.2d 832, 833 (2d Cir. 1930), as follows:

7a

. .no court can make a decree which will bind anyone but a

party; a court of equity is as much so limited as a court of

law; it cannot lawfully enjoin the world at large, no matter

how broadly it words its decree. If it assumes to do so, the

decree is pro tanto brutum fulmen, and the persons enjoined

are free to ignore it. It is not vested with sovereign powers to

declare conduct unlawful; its jurisdiction is limited to those

over whom it gets personal service, and who therefore can

have their day in court.

* * *

“This is far from being a formal distinction; it goes deep

into powers of a court of equity. . . .It is by ignoring such

procedural limitations that the injunction of a court of

equity may by slow steps be made to realize the worst fears

of those who are jealous of its prerogative.”

In addition, Respondent has acknowledged that he has taken no

proofs as to whether Petitioner or the other affected school

districts (with the exception of the Detroit school district) have

committed acts of de jure segregation. Absent such a finding,

Respondent’s remedial powers cannot extend to Petitioner. Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971);

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (1971), a ff’d. 92 Sup. Ct.

707 (1972).

III. The aim of Congress in creating United States district

courts of three judges was to erect “procedural protection against

an improvident state-wide doom by a federal court of a state’s

legislative policy.” Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246, 251

(1940). The legislative history of Title 28 USC § 2281 indicates

that the section was “enacted to prevent a single federal judge

from being able to paralyze totally the operation of an entire

[state] regulatory scheme by issuance of a broad injunctive

order.” Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 154 (1962).

Other decisions of the United States Supreme Court represent

“unmistakable recognition of the congressional policy to provide

for a three-judge court whenever a state statute is sought to be

enjoined on grounds of federal unconstitutionality. . . .” Florida

Lime Growers v. Jacobsen, 362 U.S. 73, 81 (1959).

8a

Where such circumstances are present, the case is one that is

‘required by. . .Act of Congress to be determined by a district

court of three judges.’ 28 USC § 1253. (Emphasis added.)

Florida Lime Growers, supra, at 85.

It is manifest that Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and

Order enjoins Petitioner (and 53 other tri-county school disctricts)

from exercising and discharging a veritable host of powers and

duties conferred upon each of them by the Michigan School Code

of 1955. See paragraphs 7 and 8 of Facts, supra. Beyond all this,

Respondent baldly orders the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction to ignore state law in his recommendations to

Respondent, if such law “conflicts with what is necessary to

achieve the objectives of” Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and

Order. If ever an order of an individual United States District

Judge “paralyzes” or “dooms” a state’s legislative policy, the

order in question is it. One can scarcely imagine a clearer case for

application of the principle enunciated in Phillips, supra. The

780,000 school children residing in the affected geographic area,

together with their parents, teachers and school administrators, are

without doubt entitled to the procedural protection afforded, m

Congress’ wisdom and through its mandate, by a court of three

judges. The convictions, and indeed prejudices, of an individual

judge, no matter how learned, must be tempered when an

injunction having the disruptive and dismantling effects of

Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order is at issue.

INTERIM RELIEF REQUESTED

To implement the Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition sought

herein by Petitioner, Petitioner prays this Court to stay or suspend

forthwith the proceedings, at least to the extent they affect

Petitioner, contemplated by Respondent’s June 14, 1972 Order

and Ruling until such time as the ruling relative to this Petition has

occurred.

9a

ULTIMATE RELIEF REQUESTED

Issuance of the writ herein requested.

DICKINSON, WRIGHT, McKEAN & CUDLIP

By: /s/ Fred W. Freeman

I/s/ Charles F. Clipper!

/s/ Robert V. Peterson ' *

A ttorneys for Petitioners

Bloomfield Hills School District

1700 North Woodward Avenue

P. O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

(313) 646-4300

Dated: June 26, 1972

10a

EXHIBIT A

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

and

D E T R OIT FEDERATION OF

TEACHERS, LOCAL 231, AMER

ICAN FEDERATION OF TEACH-

CIVIL ACTION

No. 35257

ERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-

et al.

Intervenor

RULING ON DESEGREGATION AREA

AND

ORDER FOR DEVELOPMENT OF PLAN OF DESEGREGATION

On September 27, 1971 the court made its Ruling on Issue of

Segregation, holding that illegal segregation exists in the public

schools of the City of Detroit as a result of a course of conduct on

the part of the State of Michigan and the Detroit Board of

Education. Having found a constitutional violation as established,

on October 4, 1971 the court directed the school board

defendants, City and State, to develop and submit plans of

desegregation, designed to achieve the greatest possible degree of

actual desegregation, taking into account the practicalities of the

situation. The directive called for the submission of both a

11a

“Detroit-only” and a “Metropolitan” plan.

Plans for the desegregation of the Detroit schools were

submitted by the Detroit Board of Education and by the

plaintiffs. Following five days of hearings the court found that

while plaintiffs’ plan would accomplish more desegregation than

now obtains in the system, or which would be achieved under

either Plan A or C of the Detroit Board of Education submissions,

none of the plans would result in the desegregation of the public

schools of the Detroit school district. The court, in its findings of

fact and conclusions of law, concluded that “relief of segregation

in the Detroit public schools cannot be accomplished within the

corporate geographical limits of the city,” and that it had the

authority and the duty to look beyond such limits for a solution

to the illegal segregation in the Detroit public schools.

Accordingly, the court ruled, it had to consider a metropolitan

remedy for segregation.

The parties submitted a number of plans for metropolitan

desegregation. The State Board of Education submitted six -

without recommendation, and without indication any preference.

With the exception of one of these, none could be considered as

designed to accomplish desegregation. On the other hand the

proposals of intervening defendant Magdowski, et al., the Detroit

Board of Education and the plaintiffs were all good faith efforts to

accomplish desegregation in the Detroit metropolitan area. The

three plans submitted by these parties have many similarities, and

all of them propose to incorporate, geographically, most-and in

one instance, all-of the three-county area of Wayne, Oakland and

Macomb.

The hearing on the proposals have set the framework, and have

articulated the criteria and considerations, for developing and

evaluating an effective plan of metropolitan desegregation. None

of the submissions represent a complete plan for the effective and

equitable desegregation of the metropolitan area, capable of

implementation in its present form. The court will therefore draw

upon the resources of the parties to devise, pursuant to its

direction, a constitutional plan of desegregation of the Detroit

public schools.

12a

Based on the entire record herein, the previous oral and written

rulings and orders of this court, and the Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law filed herewith, IT IS ORDERED:

I.

A. As a panel charged with the responsibility of preparing and

submitting an effective desegretation plan in accordance with the

provisions of this order, the court appoints the following:

1. A designee of the State Superintendent of Public

Instruction;*

2. Harold Wagner, Supervisor of the Transportation Unit in

the Safety and Traffic Education Program of the State

Department of Education;

3. Merle Henrickson, Detroit Board of Education;

4. Aubrey McCutcheon, Detroit Board of Education;

5. Freeman Flynn, Detroit Board of Education;

6. Gordon Foster, expert for plaintiffs;

7. Richard Morshead, representing defendant Magdowski, et

ah;

8. A designee of the newly intervening defendants;*

9. Rita Scott, of the Michigan Civil Rights Commission.

Should any designated member of this panel be unable to serve,

the other members of the panel shall elect any necessary

replacements, upon notice to the court and the parties. In the

absence of objections within five days of the notice, and pending a

final ruling, such designated replacement shall act as a member of

the panel.

*The designees of the State Superintendent of Public Instruction and newly

intervening defendants shall be communicated to the court w ithin seven days

of the entry of this order. In the event the newly intervening defendants

cannot agree upon a designee, they may each submit a nominee within seven

days from the entry of this order, and the court shall select one of the

nominees as representative of said defendants.

13a

B. As soon as possible, but in no event later than 45 days after

the issuance of this order, the panel is to develop a plan for the

assignment of pupils as set forth below in order to provide the

maximum actual desegregation, and shall develop as well a plan for

the transportation of pupils, for implementation for all grades,

schools and clusters in the desegregation area. Insofar as required

by the circumstances, which are to be detailed in particular, the

panel may recommend immediate implementation of an interim

desegregation plan for grades K-6, K-8 or K-9 in all or in as many

clusters as practicable, with complete and final desegregation to

proceed in no event later than the fall 1973 term. In its

transportation plan the panel shall, to meet the needs of the

proposed pupil assignment plan, make recommendations, includ

ing the shortest possible timetable, for acquiring sufficient

additional transportation facilities for any interim or final plan of

desegregation. Such recommendations shall be filed forthwith and

in no event later than 45 days after the entry of this order. Should

it develop that some additional transportation equipment is

needed for an interim plan, the panel shall make recommendations

for such acquisition within 20 days of this order.

C. The parties, their agents, employees, successors and all others

having actual notice of this order shall cooperate fully with the

panel in their assigned mission, including, but not limited to, the

provision of data and reasonable full and part-time staff assistance

as requested by the panel. The State defendants shall provide

support, accreditation, funds, and otherwise take all actions

necessary to insure that local officials and employees cooperate

fully with the panel. All reasonable costs incurred by the panel

shall be borne by the State defendants; provided, however, that

staff assistance or other services provided by any school district,

its employees or agents, shall be without charge, and the cost

thereof shall be borne by such school district.

II.

A. Pupil reassignment to accomplish desegregation of the

Detroit public schools is required within the geographical area

which may be described as encompassing the following school

districts (see Exhibit P.M. 12), and hereinafter referred to as the

“desegregation area” :

14a

Lakeshore Birmingham Fair lane

Lakeview Hazel Park Garden City

Roseville Highland Park North Dearborn Heights

South Lake Royal Oak Cherry Hill

East Detroit Berkley Inkster

Grosse Pointe Ferndale Wayne

Centerline Southfield Westwood

Fitzgerald Bloomfield Hills Ecorse

Van Dyke Oak Park Romulus

Fraser Redford Union Taylor

Harper Woods West Bloomfield River Rouge

Warren Clarenceville Riverview

Warren Woods Farmington Wyandotte

Clawson Livonia Allen Park

Hamtramck South Redford Lincoln Park

Lamphere Crestwood Melvindale

Madison Heights Dearborn Southgate

Troy Dearborn Heights Detroit

Provided, however, that if in the actual assignment of pupils it

appears necessary and feasible to achieve effective and complete

racial desegregation to reassign pupils of another district or other

districts, the desegregation panel may, upon notice to the parties,

apply to the Court for an appropriate modification of this order.

B. Within the limitations of reasonable travel time and distance

factors, pupil reassignments shall be effected within the clusters

described in Exhibit P.M. 12 so as to achieve the greatest degree of

actual desegregation to the end that, upon implementation, no

school, grade or classroom be substantially disproportionate to the

overall pupil racial composition. The panel may, upon notice to

the parties, recommend reorganization of clusters within the

desegregation area in order to minimize administrative inconven

ience, or time and/or numbers of pupils requiring transportation.

C. Appropriate and safe transportation arrangements shall be

made available without cost to all pupils assigned to schools

deemed by the panel to be other than “walk-in” schools.

D. Consistent with the requirements of maximum actual

desegregation, every effort should be made to minimize the

numbers of pupils to be reassigned and requiring transportation,

the time pupils spend in transit, and the number and cost of new

transportation facilities to be acquired by utilizing such techniques

as clustering, the “skip” technique, island zoning, reasonable

15a

staggering of school hours, and maximization of use of existing

transportation facilities, including buses owned or leased by school

districts and buses operated by public transit authorities and

private charter companies. The panel shall develop appropriate

recommendations for limiting transfers which affect the

desegregation of particular schools.

E. Transportation and pupil assignment shall, to the extent

consistent with maximum feasible desegregation, be a two-way

process with both black and white pupils sharing the responsibility

for transportation requirements at all grade levels. In the

determination of the utilization of existing, and the construction

of new, facilities, care shall be taken to randomize the location of

particular grade levels.

F. Faculty and staff shall be reassigned, in keeping with pupil

desegregation, so as to prevent the creation or continuation of the

identification of schools by reference to past racial composition,

or the continuation of substantially disproportionate racial

composition of the faculty and staffs, of the schools in the

desegregation area. The faculty and staffs assigned to the schools

within the desegregation area shall be substantially desegregated,

bearing in mind, however, that the desideratum is the balance of

faculty and staff by qualifications for subject and grade level, and

then by race, experience and sex. In the context of the evidence in

this case, it is appropriate to require assignment of no less than

10% black faculty and staff at each school, and where there is

more than one building administrator, every effort should be made

to assign a bi-racial administrative team.

G. In the hiring, assignment, promotion, demotion, and

dismissal of faculty and staff, racially non-discriminatory criteria

must be developed and used; provided, however, there shall be no

reduction in efforts to increase minority group representation

among faculty and staff in the desegregation area. Affirmative

action shall be taken to increase minority employment in all levels

of teaching and administration.

H. The restructuring of school facility utilization necessitated

by pupil reassignments should produce schools of substantially

like quality, facilties, extra-curricular activities and staffs; and the

16a

utilization of existing school capacity through the desegregation

area shall be made on the basis of uniform criteria.

I. The State Board of Education and the State Superintendent

of Education shall with respect to all school construction and

expansion, “consider the factor of racial balance along with other

educational considerations in making decisions about new school

sites, expansion of present facilties * * and shall, within the

desegregation area disapprove all proposals for new construction

or expansion of existing facilties when “housing patterns in an

area would result in a school largely segregated on racial * * *

lines,” all in accordance with the 1966 directive issued by the

State Board of Education to local school boards and the State

Board’s “School Plant Planning Handbook” (see Ruling on Issue

of segregation, p. 13.).

J. Pending further orders of the court, existing school district

and regional boundaries and school governance arrangements will

be maintained and continued, except to the extent necessary to

effect pupil and faculty desegregation as set forth herein;

provided, however, that existing administrative, financial,

contractual, property and governance arrangements shall be

examined, and recommendations for their temporary and

permanent retention or modification shall be made, in light of the

need to operate an effectively desegregated system of schools.

K. At each school within the desegregated area provision shall

be made to insure that the curriculum, activities, and conduct

standards respect the diversity of students from differing ethnic

backgrounds and the dignity and safety of each individual,

students, faculty, staff and parents.

L. The defendants shall, to insure the effective desegregation

of the schools in the desegregation area, take immediate action

including, but not limited to, the establishment or expansion of

in-service training of faculty and staff, create bi-racial committees,

employ black counselors, and require bi-racial and non-discrimin-

atory extra-curricular activities.

III.

The State Superintendent of Public Instruction, with the

17a

assistance of the other state defendants, shall examine, and make

recommendations, consistent with the principles established

above, for appropriate interim and final arrangements for the (1)

financial, (2) administrative and school governance, and (3)

contractual arrangements for the operation of the schools within

the desegregation area, including steps for unifying, or otherwise

making uniform the personnel policies, procedures, contracts, and

property arrangements of the various school districts.

Within 15 days of the entry of this order, the Superintendent

shall advise the court and the parties of his progress in preparing

such recommendations by filing a written report with the court

and serving it on the parties. In not later than 45 days after the

entry of this order, the Superintendent shall file with the court his

recommendations for appropriate interim and final relief in these

respects.

In his examination and recommendations, the Superintendent,

consistent with the rulings and orders of this court, may be

guided, but not limited, by existing state law; where state law

provides a convenient and adequate framework for interim or

ultimate relief, it should be followed, where state law either is

silent or conflicts with what is necessary to achieve the objectives

of this order, the Superintendent shall independently recommend

what he deems necessary. In particular, the Superintendent shall

examine and choose one appropriate interim arrangement to

oversee the immediate implementation of a plan of desegregation.

IV.

Each party may file appropriate plans or proposals for inclusion

in any final order which may issue in this cause. The intent of this

order is to permit all the parties to proceed apace with the task

before us: fashioning an effective plan for the desegregation of the

Detroit public schools.

Fifteen days after the filing of the reports required herein,

hearings will begin on any proposal to modify any interim plan

prepared by the panel and all other matters which may be incident

to the adoption and implementation of any interim plan of

desegregation submitted. The parties are placed on notice that

they are to be prepared at that time to present their objections,

18a

alternatives and modifications. At such hearing the court will not

consider objections to desegregation or proposals offered

“instead” of desegregation.

Hearings on a final plan of desegregation will be set as

circumstances require.

DATE: JUNE 14, 1972.

/s/ Stephen J. Roth

United States District Judge

19a

DICKINSON, WRIGHT, McKEAN & CUDLIP

COUNSELLORS AT LAW

1700 North Woodward Avenue

P.O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Telephone (313) 646-4300

July 12, 1972

The Honorable Judges of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

609 Post Office Building

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Re: No. 72-1651, Bloomfield Hills School District,

Petitioner, v. Honorable Stephen J. Roth,

United States District Judge, Eastern District

of Michigan, Respondent

Dear Sirs:

On June 29, 1972, the Petition for Writ of Mandamus and/or

Prohibition of Bloomfield Hills School District was docketed by

the Clerk of your Court. The Petition relates to the June 14, 1972

Ruling and Order of the Honorable Stephen J. Roth, Respondent

to such Petition, in the so-called Detroit school desegregation case

(Bradley, et al. v. Milliken, et al, Civil Action No. 35257, United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan). In

compliance with Rule 21, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, a

copy of such June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order is attached to the

Petition.

Thereafter, on July 10, 1972, Judge Roth entered an oral Order

directing the Detroit School District to purchase 295 buses for the

purpose of implementing his June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order. The

State defendants in Bradley v. Milliken, namely, the Governor and

Attorney General of Michigan, the State Board of Education and

the State Superintendent of Public Instruction, were ordered to

pay for such buses. To implement such payment, the Treasurer of

Michigan was added as an additional State defendant.

The bus purchase order further evidences Judge Roth’s intention

20a

to put his June 14, 1972 metropolitan desegregation busing order

into effect as of the opening of school the first week in

September, less than 60 days from now.

During the course of the hearing preceding the entry of Judge

Roth’s bus purchase order, he candidly stated as follows:

“To my knowledge the propriety of going to a

metropolitan plan has not been decided by the United States

Supreme Court except in the language used in Brown in

1954, where they in broad outline said you can do anything

in order to achieve the job including dealing with school

districts. They said that in ’54. That is what 1 am relying on

and they never said otherwise but they never have had a

school case such as this where an order for metropolitan

desegregation is the issue.”

The entry of the bus purchase order underscores the urgency of

immediate consideration by this Court of Bloomfield Hills School

District’s Petition. Accordingly, we respectfully request this Court

to take such Petition under immediate advisement, to enter an

order directing Judge Roth to answer such Petition immediately,

and to set a date for hearing on the Petition as soon as possible

thereafter. In this connection, we reiterate the prayer contained in

the Petition that, in the interim, a stay of the proceedings

contemplated by Judge Roth’s June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order be

entered.

Respectfully submitted,

DICKINSON, WRIGHT, McKEAN & CUDLIP

By: /s/ Fred W. Freeman

/s/ Charles F. Clippert

/s/ Robert V. Peterson

A ttorneys for Petitioners

Bloomfield Hills School District

FWF:mak

21a

#72-1651

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BLOOMFIELD HILLS SCHOOL DIS

TRICT,

Petitioner

V . ORDER

STEPHEN J. ROTH,

United States District Judge,

Respondent **

Before: PHILLIPS, Chief Judge, EDWARDS and PECK, Circuit

Judges

Upon consideration, IT IS ORDERED that the application for

writ of mandamus and prohibition is denied and the petition is

dismissed.

This order is entered without prejudice to the right of the

petitioner School District to file application to intervene in the

case of Bradley v. Milliken now pending in the Eastern District of

Michigan.

Entered by order of the Court.

/s/ James A. Higgins

Clerk

Filed July 17, 1972

James A Higgins, Clerk

22a

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

IN THE COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BLOOMFIELD HILLS SCHOOL DIS

TRICT,

Petitioner,

vs.

STEPHEN J. ROTH, UNITED STATES

DISTRICT JUDGE, EASTERN DIS

TRICT OF MICHIGAN,

Respondent.

No. 72-1651

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND

SUGGESTION FOR HEARING IN BANC

L Events Occurring Subsequent to Filing o f Petition for Writ o f

Mandamus and/or Prohibition.

A. The Petition for Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition filed

by Bloomfield Hills School District (Petitioner) on June 29, 1972

alleged that the Honorable Stephen I. Roth, Respondent, (i)

usurped the jurisdiction vested in him as a United States District

Judge by subjecting Petitioner to his June 14, 1972 Ruling and

Order in disregard of the facts that the Petitioner was not a party

to the action and was not found to have committed any act of de

jure segregation and (ii) usurped the jurisdiction exclusively vested

by Title 28 U.S.C. I 2281 in a District Court of three judges by

entering his June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order, which restrains the

enforcement, operation and execution of various Michigan

statutes. This Court denied that petition on July 17, 1972.

B. While no reasons for this Court’s action were given, the

order stated that the denial was without prejudice to the right of

Petitioner to file an application to intervene in the case of Bradley

v. Milliken pending in the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Michigan.

C. The intervening school district defendants in Bradley v.

23a

Milliken filed an emergency application for stay with Respondent

on July 12, 1972. A jurisdictional attack on Respondent's June

14, 1972 Ruling and Order under § 2281 comprised one of the

grounds for such emergency application. On July 19, 1972,

Respondent denied that application without responding to such

jurisdictional attack.

D. On July 20, 1972, Respondent made a determination of

finality as to the following orders in Bradley v. Milliken under

Rule 54(b), F.R.C.P., and certified the issues presented therein

under the provisions of 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b):

1. Ruling on Issue of Segregation, September 27, 1971;

2. Ruling on Propriety of Considering a Metropolitan

Remedy To Accomplish Desegregation of the Public

Schools of the City of Detroit, March 24, 1972;

3. Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-only

Plans of Desegregation, March 28, 1972;

4. Ruling on Desegregation Area and Development of Plan,

and Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support

Thereof, June 14, 1972; and

5. Order of Acquisition of Transportation, July 11, 1972.

E. On July 20, 1972, this Court entered an order which, inter

alia, advanced the appeal of Bradley v. Milliken on its docket and

scheduled a hearing therein for August 24, 1972.

F. Petitioner reiterates its assertion that Respondent’s June 14,

1972 Ruling and Order has the effect of enjoining the

enforcement, operation and execution of a number of Michigan

statutes of which the following are illustrative:

1. MCLA 340.77

The board of any school district governed by the

provisions of this chapter is authorized to locate, acquire,

purchase or lease in the name of the district such site or

sites within or without the district for schoolhouses,

libraries, administration buildings, agricultural farms,

athletic fields and playgrounds, as may be necessary; to

24a

purchase, lease, acquire, erect or build and equip such

buildings for school or library or administration or for

use in connection with agricultural farms, athletic fields

and playgrounds, as may be necessary; to pay for the

same out of the funds of the district provided for that

purpose; to sell, exchange or lease any real or personal

property of the district which is no longer required

thereby for school purposes, and give proper deeds or

other instruments passing title to the same . . .

2. MCLA 340.352

Every school district shall be a body corporate under the

name provided in this act, and may sue and be sued in its

name, may acquire and take property, both real and

personal, for educational purposes within or without its

corporate limits, by purchase, gift, grant, devise or

bequest, and hold and use the same for such purposes,

and may sell and convey the same as the interests of such

district may require, subject to the conditions of this

act contained . . .

3. MCLA 340.356

All persons, residents of a school district not maintaining

a kindergarten, and at least 5 years of age on the first day

of enrollment of the school year, shall have an equal right

to attend school therein.

4. MCLA 340.569

The board of every district shall hire and contract with

such duly qualified teachers as may be required . . .

5. MCLA 340.575

The board of every district shall determine the length of

the school term. The minimum number of days of

student instructions shall be not less than 180. Any

district failing to hold 180 days of student instruction

shall forfeit 1/180th of its total state aid appropriation

for each day of such failure . . .

25a

6. MCLA 340.583

Every board shall establish and carry on such grades,

schools and departments as it shall deem necessary or

desirable for the maintenance and improvement of the

schools; determine the courses of study to be pursued

and cause the pupils attending school in such district to

be taught in such schools or departments as it may deem

expedient. . .

7. MCLA 340.589

Every board is authorized to establish attendance areas

within the school district.

8. MCLA 340.614

Every board shall have authority to make reasonable rules

and regulations relative to anything whatever necessary

for the proper establishment, maintenance, management

and carrying on of the public schools of such district,

including regulations relative to the conduct of pupils

concerning their safety while in attendance at school or

en route to and from school.

9. MCLA 340.882

The board of each district shall select and approve the

textbooks to be used by the pupils of the schools of its

district on the subjects taught therein.

On June 29, 1972, Dr. John W. Porter, Superintendent of

Public Instruction, in response to paragraph III of Respondent’s

June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order, filed his written report with the

District Court. At pages 33 and 34 of the June 29 report, Dr.

Porter discussed the implications of Respondent’s June 14, 1972

Ruling and Order with respect to certain provisions of the

constitution and statutes of Michigan. Pertinent portions of pages

33 and 34 of that report are annexed hereto as Appendix A.

II. Reasons For Granting Petition For Rehearing.

A. The manifest purpose of Congress in enacting Title 28,

U.S.C. § 2281 was to prevent one federal judge from enjoining the

26a

operation of state laws. The applicability of § 2281 to

Respondent's June 14, 1972 Ruling and Order has been presented

to Respondent and to this Court. To date neither court has

discussed this jurisdictional issue on its merits. Petitioner is

aggrieved by the refusal of the courts to address the merits of this

issue.

Moreover, the July 20, 1972 Order of Respondent makes moot

the possibility that Petitioner can obtain redress from Respondent

through the procedure suggested by this Court, namely, the filing

of an application to intervene in Bradley v. Milliken. Thus, this

Petition for Rehearing constitutes the only effective remedy

available to Petitioner.

This Court has already scheduled an August 24, 1972 hearing

for the appeal in Bradley v. Milliken. Without adversely affecting

the rights of the parties in that appeal, the August 24 hearing can

be readily expanded to give Petitioner its day in court with respect

to the issues raised in its Petition for Writ of Mandamus and/or

Prohibition.

B. While it is clear that Respondent based his June 14, 1972

Ruling and Order upon the language contained in Brown II, 349

U.S. 294 (1955), which discusses the breadth of equitable powers

available to a district court in a school desegregation case, it is also

clear that de jure acts of segregation violative of the Fourteenth

Amendment of the United States Constitution are the

jurisdictional sine quo non for the entry of a remedial decree. It

appears beyond dispute that Respondent’s decree which interdicts

the wide-spread operation of state statutes can be justified only

upon the ground that the operation of such statutes conflicts with

the Fourteenth Amendment. The convening of a three judge

district court under § 2281 is mandatory when that conflict

arises. Notwithstanding the opinion of Judge Merhige, {Bradley v.

School Board o f City o f Richmond, Virginia, 324 F. Supp. 396

[1971]), it is contrary to the manifest purpose and unambiguous

language of § 2281 to suggest, on the one hand, that the validity

of state laws under the United States Constitution never arises

when a decree in a school desegregation case is being fashioned,

and to justify, on the other hand, a decree enjoining the operation

of those laws on the ground that acts of de jure segregation in

27a

violation of the United States Constitution have occurred.

C. Bradley v. Milliken was not a three judge court case when

initially filed. Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897 (1970), n. 2, p.

900. It becomes a three judge court case when an injunction is

issued which restrains the operation of state statutes affecting 54

local school districts, 780,000 students and several thousand

teachers and local school administrators upon the ground of

unconstitutionality. Even the jurisdiction of this Court to hear an

appeal upon issues beyond the scope of the Detroit school district

is burdened by § 2281. Stratton v. St. Louis S. W. Ry. Co., 282

U.S. 10(1930).

The argument in the appeal in Bradley v. Milliken will be heard

in less than one month. Neither Respondent nor this Court has, as

yet, responded to the merits of the jurisdictional questions raised

by § 2281. The most efficient and practical way of promptly

resolving the § 2281 question as well as other questions raised in

the Petition for Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition is to hear

Petitioner’s arguments with respect thereto in this Court on

August 24, 1972, when arguments on the issues in Bradley v.

Milliken are presented.

RELIEF REQUESTED

Petitioner prays this Court to:

a. Take this Petition for Rehearing under immediate

advisement;

b. Restore this cause to the calendar and set August 24,

1972 as the time for hearing the Petition for Writ of Mandamus

and/or Prohibition;

c. Order Respondent to file an Answer to the Petition for

Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition in accordance with Rule

21, F.R.A.P., and order the filing of briefs in compliance with

the schedule set forth in this Court’s Order of July 20, 1972, in

the appeal in Bradley v. Milliken.

SUGGESTION FOR HEARING IN BANC

It is respectfully suggested that in the event the appeal in

28a

Bradley v. Milliken is heard by this Court in banc pursuant to Rule

35, F.R.A.P., the Petition of Bloomfield Hills School District for

Writ of Mandamus and/or Prohibition be heard in banc.

Respectfully submitted,

DICKINSON, WRIGHT, McKEAN & CUDLIP

By: /s/ Fred W. Freeman

/s/ Charles F. Clippert

/s/ Robert V. Peterson

A ttorneys for Petitioners

Bloomfield Hills School District

1700 North Woodward

P.O. Box 509

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

(313) 646-4300

Dated: July 27, 1972

29a

APPENDIX A

ABSTRACT OF DR. PORTER’S REPORT

OF JUNE 29, 1972

Implications for the Interim Period

Effective implementation of the desegregation plan during the

interim period may require the following actions:

1. Amendment of, or a moratorium on, the provisions o f

Article IX, Section 6, o f the Michigan Constitution,

which sets a 15 mill limit on the property tax.

2. Amendment o f A ct 62, Public Acts o f 1933, the Proper

ty Tax lim itation Act.

3. Amendment o f A ct 31, Public Acts o f 1966, which

deals with the assessing and collecting o f taxes within a

city.

4. Amendment o f A ct 190, Public Acts o f 1962, which

deals with adoption o f special education millage on an

intermediate district basis.

5. Amendment of, or a moratorium on, certain provisions

o f the School Code o f 1955 which deal with the powers

and duties o f local school districts.

6. Amendment of, or a moratorium on, certain provisions

o f A ct 336, Public Acts o f 1947, the Public Employees

Relations Act.

7. Amendment of, or a moratorium on, certain provisions

o f A ct 4, Public Acts o f 1937, the Teacher Tenure Act.

8. Amendment o f Act 36, Public Acts o f 1945, the Public

School Employees Retirement Act.

9. Amendment o f the Rules and Regulations Governing

the Certification o f Teachers.

10. Amendment o f Federal Statutes and Guidelines as

embodied in Title I o f the Elementary and Secondary

Education A ct o f 1965, which provides approximately

30a

$25 million annually to districts in the desegregation

area, and is based on concentrations o f children from

low income families.

Implications for the Period o f Full Implementation

It appears almost certain that the period of full implementation

will have direct implications for the possible amendment of all the

constitutional, statutory, and administrative provisions outlined in

the above section dealing with the interim period. In addition, it

appears the following statutes may require amendment:

(1) The State School Aid Act.

(2) Those provisions o f the School Code o f 1955 dealing

with the establishment or creation o f school districts.

(3) Act 320, Public Acts o f 1968, which deals with the

establishment o f area vocational centers.