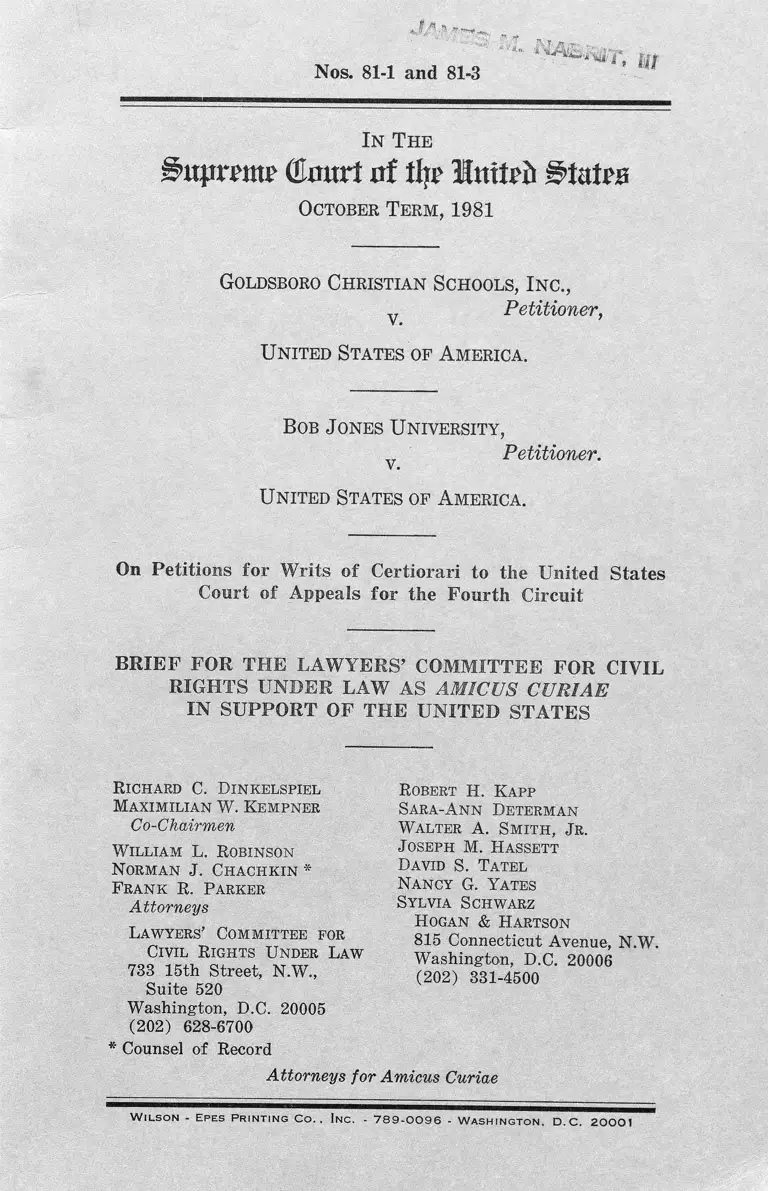

Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. v. United States Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc. v. United States Brief Amicus Curiae, 1981. 9acd538f-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/145a8c1b-df51-4698-a377-7c4db7896644/goldsboro-christian-schools-inc-v-united-states-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 81-1 and 81-3 Mr

I n T h e

^ u jrrm ? Gkrurt trf % M n tM J^tate

October Term, 1981

Goldsboro Ch r ist ia n S chools, I n c .,

y Petitioner,

U n it e d S tates of A m erica .

B ob J o n es U n iv er sity ,

Petitioner.

U n it e d S tates of A m erica .

On Petitions for Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF THE UNITED STATES

Richard C. Dinkelspiel

Maximilian W. Kempner

Co-Chairmen

William L. Robinson

Norman J. Chachkin *

Frank R. Parker

Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 15th Street, N.W.,

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 628-6700

* Counsel of Record

Robert H. Kapp

Sara-Ann Determan

Walter A. Smith , J r.

J oseph M. Hassett

David S. Tatel

Nancy G. Yates

Sylvia Schwarz

H ogan & Hartson

815 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

(202) 331-4500

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - 7 8 9 - 0 0 9 6 - W a s h i n g t o n . D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

Table of Authorities ........ ..................... .......................... ii

Interest of Amicus Curiae...........................- ................. 1

Summary of Argument------- ------------------------------- 3

Argument .......................... ....................... - ............... ....... 5

I. The Federal Government Is Constitutionally Pro

hibited from Granting Tax Benefits to Racially

Discriminatory Private Schools - ---- -------- --- 5

II. The Government’s Decision Not to Support

Racially Discriminatory Private Schools Does

Not Violate Petitioners’ First Amendment

R ights............-............ ............ .................... -......... 18

A. The Burden on Petitioners’ Free Exercise

Rights Is Not Significant ....................... ...... 20

B. The Governmental Interests at Stake Are

Compelling and Constitutionally Based...... 23

C. The Government’s Interests are Sufficiently

Compelling to Outweigh the Minimal Burden

on Petitioners’ Free Exercise R ights-------- 26

Conclusion.................... 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396

U.S. 19 (1969) ............. .................... ....... ............ 2

Board of Educ. v. Allen, 392 U.S. 236 (1968) ..... 15n

Bob Jones Univ. v. Johnson, 396 F. Supp. 597

(D.S.C. 1974), aff’d mem. 529 F.2d 514 (4th

Cir. 1975)__________ __________ __ ______ _ 29, 30

Bob Jones Univ. v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725 (1974).... 5n, 10,

11

Bob Jones Univ. v. United States, 639 F.2d 147

(4th Cir. 1980), cert, granted, 50 U.S.L.W.

3278 (U.S,, Oct. 13, 1981) _________________ 18n

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S, 497 (1954) ............... 7

Braunfeld v. Brown, 366 U.S. 599 (1961)......21, 22, 27n

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954).... 7, 8,

23, 25

Brown v. Califano, 627 F.2d 1221 (D.C. Cir.

1980)______ 18n

Brown v. Dade Christian Schools, Inc., 556 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977) (en banc), cert, denied,

434 U.S. 1063 (1978) ___________ ___ ____ 22n, 28n

Brumfield v. Dodd, 405 F. Supp. 388 (E.D. La.

1975) ____ 24n

Coffey v. State Educ. Fin. Comm’n, 296 F. Supp.

1387 (S.D. Miss, 1969) ........ ................ .............. 11,13

Coit v. Green, 404 U.S, 997 (1971) .......... ........ 4n, 5n, 6n

Committee for Public Educ. v. Nyquist, 413 U.S.

756 (1973) ................................... ..4,16,17

Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959), aff’g

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark.

1959) ........... ........... ......................... .......... ......... - 8n

Fiedler v. Marumsco Christian Schools, 631 F.2d

1144 (4th Cir. 1980) ......... ......... ...... .................. 26n

Flagg Bros., Inc. v. Brooks, 436 U.S. 149 (1978).. lOn,

18n

Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258 (1971) .......... ....... . 6n

Fusari v. Steinberg, 419 U.S. 379 (1975) ...... 6n

Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556

(1974) ...................................... ........... ..... ..17n, 18n, 24n

Page

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C.),

aff’d sub nom. Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997

(1971) ........... ..................... ....... 3, 4, 5, 6n, 7n, 9, 24n, 25

Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp. 1127 (D.D.C.),

appeal dismissed sub nom. Cannon v. Green, 398

U.S. 956 (1970) ......................... ........ ..... .......... 2, 11, 12

Green v. Kennedy, Civ. No. 1355-69 (D.D.C.) ..... 5n

Green v. Regan, Civ. No. 1355-69 (D.D.C.)............ 3

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) .......................... ...8n, 24n

Grove City College v. Harris, 500 F. Supp. 253

(W.D. Pa. 1980) ____ ____ ________ _____ _ 18n

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 197 F. Supp.

649 (E.D. La. 1961), aff’d 368 U.S. 515 (1962).. 24n

Harris v. McRae, 448 U.S. 297 (1980) .... ............ ..19, 20n

Hicks v. Miranda, 442 U.S. 332 (1975) ____ ___ 6n

Iron Arrow Honor Soc. v. Hufstedler, 499 F. Supp.

496 (S.D. Fla. 1980), aff’d 652 F.2d 445 (5th

Cir. 1981), pet. for cert, filed, 50 U.S.L.W. 3377

(Oct. 31, 1981) ....... ........... .......... ........ ............. 18n

Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S, 361 (1974) ______ 22n

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp.

458 (M.D. Ala,), aff’d sub nom. Wallace v.

United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) ......... ......... 9

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1971) ........... 16

Louisiana Fin. Assistance Comm’n v. Poindexter,

389 U.S. 571 (1968), aff’g 275 F. Supp. 833

(E.D. La. 1967) ..... ......... ............ ............. ......... 8n

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967) ......... ...... 13n, 14n

Maher v. Roe, 432 U.S. 464 (1977) ........ 17n-18n

Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173 (1976) ............... 6n

McDaniel v. Paty, 435 U.S. 618 (1978)...... 26

McGlotten v. Connally, 338 F. Supp. 448 (D.D.C.

1972) ........ ....................... ......... ....... ..... 6n, 7n, 12n, 25n

McKeesport Area School Dist. v. Pennsylvania

Dept, of Educ., 446 U.S. 970 (1980) .................. 6n

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ....... 13n

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 256

F. Supp. 941 (D.S.C. 1966), rev’d in part, 377

F.2d 433 (4th Cir. 1967), modified and aff’d per

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

curiam, 390 U.S. 400 (1968) ............ ............... . 29n

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) ____ passim

O’Hair v. Paine, 312 F. Supp. 434 (W.D. Tex.

1969), appeal dismissed, 397 U.S. 531 (1970),

aff’d 432 F.2d 66 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

401 U.S. 955 (1971) _________ __ ________

Orleans Parish School Bd. v. Bush, 365 U.S. 569

(1961), aff’g 187 F. Supp. 42, 188 F. Supp. 916

(E.D. La. 1960) _____________ ______ ______

Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of City Trusts,

353 U.S. 230 (1957) ____ ______ ___ _______

Poindexter v. Louisiana Fin. Assistance Comm’n,

275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff’d 389 U.S.

571 (1968) ______ _____ _______ __________

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944)....

Radovich v. National Football League, 352 U.S.

445 (1957) _______________ _________ ___ _

Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1878).—

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)._6n, 8n, 17n, 25

St. Helena Parish School Bd. v. Hall, 368 U.S.

515 (1962), aff’g 197 F. Supp. 649 (E.D. La.

1961) ....... ........... ................... ............... ......... ..... 8n

Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) ........20n, 27, 28

Smith and United States v. North Carolina State

Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. 2572 (E.D.N.C., May 18,

1971) ____________ - __ ______________________ lOn

South Carolina State Bd. of Educ. v. Brown, 393

U.S. 222 (1968), aff’g 296 F. Supp. 199 (D.S.C.

1968) __ _______ ___ _____ _________ ___ __ _ 8n

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1880).. 8n

Thomas v. Review Bd., 101 S. Ct. 1425 (1981).... 27,28

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo

Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840

(1967) ________ __ - ................. ................... . 24n

19n

8n

8n

24n

29n

6n

29n

V

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES—Continued

Page

Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967),

aff’g Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267

F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967) ____ _______ 8n

Walz v. Tax Comm’n, 397 U.S. 644 (1970) .14, 15, 16, 19

West Virginia State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette,

319 U.S. 624 (1943)............. .......... ................ . 28

Whittenberg v. Greenville County School Dist.,

decided sub nom. Stanley v. Darlington County

School Dist., 424 F.2d 195 (4th Cir. 1970) ___ lOn

Widmar v. Vincent, 50 U.S.L.W. 4062 (U.S., Dec.

8, 1981) ____ _________ ______ ________ _____ 27

Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972) ........ 20, 21, 22,

27, 28

Statutes:

26 U.S.C. § 170 ............... .................................. In, 10, 12n

26 U.S.C. § 501 (c) (3) ..... .......... ........... ....... In. 10, 27-28

26 U.S.C. § 501 (i) _______ ______ _______ __ _ On

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...................... .......................... 8n. 25, 26n

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c-2000d-4 ...... .... ....... .......... ...... 25

42 U.S.C. § 2000d ______________ ____ _______ 25n, 29n

P.L. No. 96-74, 93 Stat. 559 (1979) ___________ 7n

L egisla tive M aterials:

S. Rep . No. 1318, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976),

reprin ted in [1976] U.S. Code Cong. & Adm .

N ews ............ ............. ................................ ...... ....... ....... 6n, 7n

125 Cong. Rec. (1979) ....... ......... ............ .......... . 7n

Part 3D: Desegregation Under Law, Hearings

Before the Select Committee on Equal Educa

tional Opportunity of the United States Senate,

91st Cong., 2d Sess. (1970) ...... .............. ......... . 24n

Tax-Exempt Status of Private Schools: Hearings

Before the Subcommittee on Oversight of the

House Committee on Ways and Means, 96th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1979) __________ ____ 7n, 12n, 13n

Regulations and A dm in istra tive M aterials:

Rev. Proc. 71-447, 1971-2 C.B. 230 .................. . 2n

44 Fed. Reg. 9451 (February 13, 1979) ........... ...... 7n

43 Fed. Reg. 37296 (August 22, 1978) ____ __ _ 7n

41 Fed. Reg. 35553 (August 23, 1976) ...... ...... 25n

Internal Revenue Service News Release, July 10,

1970, 7 Stand Fed. Tax Rep . (CCH) 6790

(1970)............................................... ..... ........ ...... 2n

Other A uthorities:

D. Bell, Race, Racism and A merican Law

(1973) ......... ............... *....... ........................ . 2 In

Bittker & Kaufman, Taxes and Civil Rights: “Con

stitutionalizing” the Internal Revenue Code, 82

Yale L.J. 51 (1972) ........................................... 25n

Brown, Academies: Many Parents Would Give

Children Bad Educations, South Today, Dec.,

1970 _______ ___ ______ __ ____ _______ ___ _ 24n

Brown, State Action Analysis of Tax Expenditures,

11 Harv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev. 97 (1976) ........ . 17n

Brown & Provizer, The South’s New Dual School

System.: A Case Study, New South, Fall, 1972.. 24n

Comment, Tax Incentives as State Action, 122 U.

Pa . L. Rev. 414 (1973) ___________________ 17n

Commentary, Civil Rights—42 U.S.C. 1981: Keep

ing a Compromised Promise of Equality to

Blacks, 29 U. F la . L. Rev. 318 (1977) ....... . 24n

Feldstein, The Income Tax and Charitable Contri

butions: Part I—Aggregate and Distributional

Effects, 28 Nat’l Tax J. 81 (1975) .................. lOn-lln

Instant Schools, N ew sw eek , Jan. 26, 1970 ........... 24n

Miles, Private Schools: Enrollment Almost Trip

les in Tarheel State, South Today, Dec., 1971.. 24n

N at’l Center for Educ. Statistics, U.S. Dept,

of E duc., P rivate Schools in A merican E du

cation (1981) _____ ____ ___ ____ ________ 28n

D. N evin & R. Bills, the Schools T hat F ear

B uilt— Segregationist A cademies in the

South (1976) _____ ____ __________ ___ ___ 24n

Note, Section 1981 after Runyon v. McCrary: The

Free Exercise Right of Private Sectarian Schools

to Deny Admission to Blacks on Account of Race,

1977 Duke L.J. 1219 ____ ______ ____ ___ ..._26n, 28n

Note, Segregation Academies and State Action, 82

Yale L.J. 1436 (1973)

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

24n

vu

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES—Continued

Page

Note, The IRS, Discrimination, and Religious

Schools: Does the Revised Proposed Revenue

Procedure Exact Too High a Price?, 56 N otre

Dame Law . 141 (1980) .............. .... ................ —. 28n

Note, The Judicial Role in Attacking Racial Dis

crimination in Tax-Exempt Private Schools, 98

Harv. L. Rev. 378 (1979) .............. lln

J. P erlman, F ederal Tax P olicy (3d ed. 1977)- lOn

Rice, Conscientious Objection to Public Education:

The Grievance and the Remedies, 1978 B.Y.U.

L. Rev. 847 .......... ....... ............ ......................... . 28n

Southern Regional Council, T he South and

Her Ch ild ren : School Desegregation 1970-

71 (1971) __ ______ ________ ___ ________ 2 In

Spratt, Federal Tax Exemptions for Private Segre

gated Schools, 12 W m . & Mary L. Rev. 1 (1970).. 12n

Surrey, Tax Incentives as a Device for Implement

ing Government Policy: A Comparison with

Direct Government Expenditures, 83 Harv. L.

Rev. 705 (1970)_____ ______ ______ _______ 17n

Tergen, Closeup on Segregation Academies, N ew

South, Fall, 1972 ....... ..... ..... ........... ................ . 24n

Tergen, Private Schools, Charleston Style, South

Today, Jan./Feb., 1971... ........ ..... 24n

U.S. Comm’n on Civil R ights, School Desegre

gation in Ten Communities (1973) _____ ___ 24n

U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, Southern School

Desegregation 1966-67 (1967) ......................... 24n

In The

dujjrmF Qlmtrt of % li&mtvb

October T er m , 1981

Nos, 81-1 and 81-3

Goldsboro Ch r ist ia n S chools, I n c .,

Petitioner,

U n ite d S tates of A m erica .

B ob J o n es U n iv er sity ,

Petitioner.

U n ite d S tates of A m erica .

On Petitions for Writs of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF THE UNITED STATES

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President

of the United States to involve private attorneys through

out the country in the national effort to assure civil

rights to all Americans. The Committee has over the

past eighteen years enlisted the services of thousands of

members of the private bar in addressing the legal prob

lems of minorities and the poor in voting, education,

housing, municipal services, the administration of jus

tice, and law enforcement. Since 1965 the Committee

has maintained an office in Jackson, Mississippi with

full-time staff attorneys to assist black citizens in that

state.

2

The Lawyers’ Committee has long had a strong inter

est in effective public school desegregation, particularly

in Mississippi. For example, it filed a brief amicus curiae

and its then Co-Chairman (now U.S. District Judge)

Louis F. Oberdorfer presented oral argument in support

of the petitioners in Alexander v. Holmes County Board

of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969). Following the Court’s

decision in that case, many new all-white, segregated

private schools were established, and existing all-white

schools expanded, in Mississippi. These schools provided

white students and their parents with an opportunity to

avoid public school desegregation and frustrated the

efforts of federal courts and the U.S. Department of

Health, Education, and Welfare to carry out this Court’s

Alexander mandate. Nevertheless, the Internal Revenue

Service considered these private schools’ racially discrim

inatory policies irrelevant to their status as charitable in

stitutions, and the Service recognized all of them, as

exempt from federal taxation pursuant to 26 U.S.C.

§ 501(c) (3), thus qualifying third-party gifts to the

schools as tax-deductible charitable donations. Accord

ingly, in 1969 the Committee’s Mississippi office filed

suit against the Service on behalf of a class of Missis

sippi black parents and schoolchildren. The Committee

has continued to provide counsel to the plaintiffs in that

case, in which proceedings are still pending in the U.S.

District Court for the District of Columbia, sub nom.

Green v. Regan, Civ. No. 1355-69.

After the plaintiffs obtained a preliminary injunction

in that suit in 1970, Green v. Kennedy, 309 F. Supp.

1127 (D.D.C.), appeal dismissed sub nom. Cannon v.

Green, 398 U.S. 956 (1970), the Internal Revenue Serv

ice announced that it could “no longer justify allowing

tax-exempt status to private schools which practice racial

discrimination nor can it treat gifts to such schools as

charitable deductions for income tax purposes.” 1 The

1 Internal Revenue Service News Release, July 10, 1970, 7 Stand.

Fed. Tax Rep. (CCH) 6790 (1970). The change of policy was

then codified in Rev. Proc. 71-447, 1971-2 C.B. 230.

three-judge court nonetheless granted the plaintiffs’ re

quest for injunctive relief to assure that the Service

effectuated its new policy, which the court held was the

only correct interpretation of the Internal Revenue Code.

Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C.), aff’d sub

nom. Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 (1971). Subsequently,

the district court has granted further injunctive relief

to carry out the 1971 decree. Green v. Regan, Civ. No.

1355-69 (D.D.C., May 5 and June 2, 1980).

In their petitions for certiorari and briefs, both Bob

Jones University and Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc.

not only raise First Amendment claims with respect to

the application of Green principles to religious institu

tions, but they also seek a determination from this Court

that Green itself was wrongly decided. Such a ruling

would directly undercut the judgments which Lawyers’

Committee attorneys have secured in Green, and it would

also seriously weaken anew the desegregation of Missis

sippi’s public schools. Because amicus believes that there

is no credible argument for an interpretation of the

Code which would have this tragic result and, indeed,

that the Green ruling is constitutionally compelled, we

file this brief in support- of the United States.8

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

There are two important issues raised by these cases :

whether the federal government can constitutionally con

fer tax benefits on racially discriminatory private

schools; and whether the First Amendment requires the

federal government to confer those benefits on such

schools if their discrimination is religiously based. The

first issue was effectively resolved in Norwood v. Har- 2 *

2 The parties’ letters of consent are being lodged with the Clerk

pursuant to Rule 36.1.

4

rison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973), in which a unanimous. Court

declared it unconstitutional for government to lend “tan

gible financial aid” to private discriminatory schools.

There is no doubt that the tax benefits at issue in these

cases constitute such “aid,” both as a matter of fact and

as a matter of law. See Committee for Public Educa

tion v. Nyquist, 413 U.S. 756, 790-91 (1973) ; Green v.

Connolly, supra.

The First Amendment issue requires a balancing of the

public’s interest in precluding tax-benefit support to

racially discriminatory schools against the right of those

schools which discriminate racially on religious grounds

not to be unduly penalized for conduct based upon reli

gious belief. Since the government’s obligation to preclude

the benefits is constitutionally compelled, and is, in addi

tion, premised on a constitutionally rooted national policy

against racial discrimination in education ; and since the

burden on religious exercise in the present case is

minimal, the public interest in precluding benefits must

prevail.3 8

8 The first question which petitioners raise in these cases is

whether sections 501(c)(3) and 170(a)-(c) of the Internal Reve

nue Code are properly read to bar the granting of tax benefits

to racially discriminatory private schools. As indicated above,

this has been the Service’s: consistent construction of the Code since

1970. It was upheld in 1971, Green v. Connally, supra, and has

been followed by every federal court which has considered it since

that time. We do not address the question separately in this brief

but fully support the government’s arguments. Based upon amicus’

experience, however, we wish to direct the Court’s attention to two

matters:

The first point we wish to make on the statutory construction

issue concerns this Court’s ruling in Cbit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997

(1971), which this Court has said “lacks the precedential weight

of a case involving a truly adversary controversy’’ since the Service

had “reversed its position while the case was on appeal to this

5

ARGUMENT

I. THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT IS CONSTITU

TIONALLY PROHIBITED FROM GRANTING TAX

BENEFITS TO RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY

PRIVATE SCHOOLS.

While we believe the IRS, the Green court, and now,

the Fourth Circuit- in the present cases, have all cor

rectly construed Sections 501 and 170 to authorize the

Court.” Bob Jones University v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725, 740 n .l l

(1974). Even though the case may not have been “truly adversary”

in the sense that the Service did not, before this Court, oppose

the Green plaintiffs' construction of the Code, nevertheless, as we

will explain, the case was an “adversary” proceeding as to the

statutory issue pressed by the present petitioners. Under well-

settled principles, the Court’s affirmance of Green therefore is a

holding on the merits of that issue not to be overturned lightly.

Following the issuance of the preliminary injunction, the Green

three-judge district court permitted certain interveners to enter

the case in January, 1970 as representatives of parents and children

who attended or supported private: racially discriminatory schools

in Mississippi. After the Service changed its position in July,

1970, see note 1 supra and accompanying text, the only issues

which the United States litigated in the lower court in Green were

the appropriate procedures for effectuating the denial of tax bene

fits to discriminatory schools and the necessity for any injunctive

relief. See Defendants’ Memorandum in Opposition to Plaintiffs’

Proposed Injunctive Decree, Green v. Kennedy, Civ. No-. 1355-69

(D.D.C., filed Jan. 25, 1971). The interveners, however, attacked

the statutory interpretation proffered by the plaintiffs and the

Service, and which was ultimately adopted by the three-judge

court. The interveners were also the parties adversary to the

plaintiffs and the United States before this Court in 1971. In their

papers, they described the federal questions before this Court as

whether the IRS could lawfully withdraw tax benefits from racially

discriminatory private schools, and whether such withdrawal vio

lated interveners’ First Amendment rights. Jurisdictional State

ment, Coit v. Green, supra, at 13-16. In response, both the United

States and the plaintiffs moved to dismiss the appeal, primarily

on the ground that the intervenors lacked standing to raise these

issues. However, the Green plaintiffs alternatively asked this Court

.6

withholding of tax benefits from racially discriminatory

private schools, the real issue here, in our view, is not

to affirm the lower court’s judgment. Motion to Dismiss or Affirm,

Coit v. Green, supra. The Court did, in fact, summarily affirm

rather than dismiss the appeal. For this reason, amicus has always

understood this Court’s affirmance in Green to have rejected inter

veners’ two contentions on their merits, and to have confirmed

the holding (if not necessarily the specific reasoning) of the lower

court. Mandel v. Bradley, 432 U.S. 173, 176 (1976) ; Hicks v.

Miranda, 422 U.S. 332, 344 (1975) ; Fusari v. Steinberg, 419 U.S.

379, 391-92 (1975) (Burger, C.J., concurring). The fact that the

Court treated its Green affirmance as both a decision on the merits

and a holding of some importance was evident in the holding two

years later in Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 463 & n.6 (1973),

discussed in Argument I infra.

We are not contending, of course, that the Court may not, upon

reconsideration of the Green holding, now reverse its previous

affirmance of that holding; nor do we suggest that there is not

more jurisprudential leeway for such a reversal in the case of a

prior summary affirmance. Bather, we mean only to- underscore

that it is in fact a reversal that is being sought, and that peti

tioners are now making essentially the same challenges to the same

1970 IBS construction which intervenors made over ten years ago>.

In such a situation, we submit that the Court should hesitate now

to reach a different outcome, see McKeesport Area School Dist. v.

Pennsylvania Dept, of Educ., 446 U.S. 970, 971-72 (1980) (White,

J., concurring). This is especially so in light of Congress’ accept

ance of the Green holding, see infra, and the long reliance by the

Service, the courts, and the private schools themselves, on the

previous affirmance. Cf. Bunyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160, 190-92

(1976) (Stevens, J., concurring) ; Flood v. Kuhn, 407 U.S. 258,

273-76, 278-79, 283 (1971); Badovich v. National Football League,

352 U.S. 445, 450-52 (1957).

Second, we believe that congressional action since the Service

announced its construction of the Code in 1970 has confirmed and

approved that construction. In 1976, the Congress enacted 26 U.S.C.

§501(i) to deny tax-exempt status to discriminatory social clubs.

As explained in the Senate Beport on the bill, its purpose was to

overturn MeGlotten v. Connally, 338 F. Supp. 448 (D.D.C. 1972),

which had held that discriminatory fraternal beneficiary societies

were not entitled to such status, but that social clubs were. S. Bep.

No. 1318, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 8 n.5 (1976), reprinted in [1976]

U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News 6057. The “reason for change” in

one of statutory authorization ; it is one of constitutional

command.

The constitutional prohibition of racial discrimination

in education was first articulated by this Court in Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) and Bolling

v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954) (companion case to

Brown applying prohibition against state-supported school

segregation to the federal government). In Brown the

Court noted that education is “perhaps the most im-

the law was that “[i]n view of national policy,” it was considered

“inappropriate” for a discriminatory “social club or similar organi

zation” to be accorded tax-exempt status. Id. at 6058. The Report

expressly noted that McGlotten had denied tax-exempt status to

racially discriminatory fraternal societies and that this Court had

affirmed the Green decision denying tax benefits to racially dis

criminatory educational institutions. Id. at 6058 n.5. We submit

that this legislative history demonstrates (a) Congress’ commit

ment to the national policy against racial discrimination; (b) that

the policy must be taken into account in determining eligibility for

tax benefits; (c) that Congress stands ready to amend section 501

to overturn judicial decisions at odds with this national policy; and

(d) that Congress was aware of, and approved, the decision in

Green.

These conclusions are further supported by events in 1979, after

the Service had published proposed procedures for identifying

racially discriminatory private schools not entitled to tax-exempt

status. 43 Fed. Reg. 37296 (August 22, 1978) ; 44 Fed. Reg. 9451

(February 13, 1979). See Tax-Exempt Status of Private Schools:

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Oversight of the House

Committee on Ways and Means, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. 5 (1979)

(statement of Jerome Kurtz) [hereinafter cited as “1979 Hear

ings”']. Although Congress adopted riders to Treasury Department

appropriations acts to prevent the effectuation of the new pro

cedures, see P.L. No. 96-74, §§ 103, 615, 93 Stat. 559, 562, 577, it

did not suspend the Service’s authority under its existing pro

cedures to withhold tax benefits from racially discriminatory private

schools. The supporters of the appropriations riders strongly en

dorsed the substance of the Service’s 1970 construction of the

Code. See, e.g., 125 Cong. Reg. H5883 (daily ed., July 13, 1979)

(remarks of Rep. Sensenbrenner); id. at H5884 (Rep. Hammer

schmidt), H5885 (Rep, Dickinson), H5982 (daily ed., July 16,

1979) (remarks of Reps. Doman, Goldwater, and Miller).

7

portant function of state and local governments” and,

further, that government-sponsored separation of stu

dents “from others of similar age and qualifications

solely because of their race generates a feeling of in

feriority as to their status in the community that may

affect their minds and hearts in a way unlikely ever to

be undone,” 347 U.S. at 493, 494. The Court also rec

ognized that “ [t]he impact is greater when it has the

sanction of the law; for the policy of separating the races

is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the

negro group,” id . at 494 (quoting with approval the find

ings of the district court in Brown) ,4 * Because the stigma

and harm are the same whenever black children are ex

cluded from educational opportunities on the basis of

race with governmental sanction,® this Court promptly

and consistently applied Brown to affirm lower court

rulings which enjoined programs of state-furnished as

sistance to “private” schools established to circumvent

public school desegregation.6

4 See Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303, 308 (1880) : the

Fourteenth Amendment protects blacks from “unfriendly legis

lation against them distinctively as colored; exemption from legal

discriminations, implying inferiority in civil society . . . .”

6 In Runyon v. McCrary, supra, this Court sustained Congress’

authority, in enacting 42 U.S.C. § 1981 to enforce the Thirteenth

Amendment, to bar racial discrimination by private schools whether

or not the institutions were, the recipients of government largesse.

16 Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959), aff’g Aaron v. McKinley,

173 F. Supp, 944 (E.D. Ark. 1959) ; Orleans Parish School Bd. v.

Bush, 365 U.S. 569 (1961) ; aff’g 187 F. Supp. 42, 188 F. Supp.

916 (E.D. La. 1960); St. Helena Parish School Bd. v. Hall, 368

U.S. 515 (1962), aff’g 197 F. Supp. 649 (E.D. La. 1961); Griffin

v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218

(1964) ; Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) ; aff’g Lee

v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala. 1967) ;

Louisiana Fin. Assistance Cornm’n v. Poindexter, 389 U.S. 571

(1968), aff’g 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967); South Carolina

State Bd. of Educ, v. Brown, 393 U.S. 222 (1968) ; aff’g 296

F. Supp. 199 (D.S.C. 1968); cf. Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors

of City Trusts, 353 U.S. 230 (1957).

9

These developments culminated in the decision in Nor

wood, v. Harrison, supra, which makes clear that govern

ment may not lend “tangible financial aid” to private,

racially discriminatory schools, even under a facially neu

tral program which benefits all private schools. There,

the Court reviewed the constitutionality of a Mississippi

statute which made free textbooks available to schoolchil

dren in both public and private schools, without regard

to whether the schools were racially discriminatory. On

reasoning clearly applicable to the present cases, the

Court declared the loaning of textbooks to racially dis

criminatory schools to be unconstitutional.

“Racial discrimination in state-operated schools,” said

the Court, “is barred by the Constitution and ‘[i]t is

also axiomatic that a state may not induce, encourage,

or promote private persons to accomplish what it is con

stitutionally forbidden to accomplish.’ ” 413 U.S. at 465

(quoting Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 267

F. Supp. 458, 475-76 (M.D. Ala.), aff’d sub nom. Wallace

v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967)). Hence, said the

Court, government may not provide “tangible financial

aid” to an educational institution “if that aid has a

significant tendency to facilitate, reinforce, and support

private discrimination.” Id, at 466.

The essential issue in Norwood, then, was whether the

textbooks amounted to “tangible aid” that had a “signifi

cant tendency” to “support” private discrimination in the

schools. The Court said they did, noting that textbooks

are “not legally distinguishable from the forms of state

assistance foreclosed by the prior cases.” Id. at 463. The

“prior cases” relied on were several of the lower court

decisions cited in note 6 supra, which “ [t]his Court has

consistently affirmed [,] . . . enjoining state tuition grants

to students attending racially discriminatory private

schools,” id., as well as Green v. Connolly, supra, the

very ease which prohibited the granting of the tax bene

fits at issue here.

10

On the remaining question, whether the provision of

the textbook aid had a “significant tendency” to “sup

port private discrimination,” the Court concluded that

since textbooks are “ [a]n inescapable educational cost,”

and since the state was bearing that cost, “the economic

consequence is to give aid to the enterprise; if the school

engages in discriminatory practices the state by tangible

aid in the form of textbooks thereby gives support to

such discrimination.” Id. at 464-65.7

We do not see how Norwood can be read other than to

declare unconstitutional the issuance of tax benefits to

racially discriminatory schools.

It can hardly be doubted that government benefits

made available under Sections 501 and 170 provide “tan

gible financial aid” to the schools. As this Court ex

plicitly recognized when Bob Jones was last before it,

“ [R]evocation of a § 501(c) (3) ruling letter and con

sequent removal from, the Cumulative List [approving

deductibility of donor contribution under Section 170]

is likely to result in serious damage to a charitable or

ganization.” Boh Jones University v. Simon, 416 U.S.

725, 730 (1974).8 “Many contributors simply will not

7 Significantly, Norwood did not require any showing that gov

ernment aid to private schools interfered with public school deseg

regation. See 413 U.S. at 465-66; cf. Flagg Bros., Inc. v. Brooks,

436 U.S. 149, 163 (1978). However, even if Norwood’s holding

were limited to situations in which government aid to segregated

private schools followed upon public school desegregation orders,

it would apply here. Bob Jones and Goldsboro are both located in

or near desegregating school districts. See Whittenberg v. Green

ville County School Dist., decided sub nom. Stanley v. Darlington

County School Dist., 424 F.2d 195 (4th Cir. 1970) ; Smith and

United States v. North Carolina State Bd. of Educ., Civ. No. 2572

(E.D.N.C., May 18, 1971) (consent decree providing for desegre

gation of Goldsboro city schools).

8 The considerable value of these tax benefits to educational and

other charitable institutions is demonstrated in numerous economic

studies. See, e.g., J. P erlman, F ederal Tax P olicy 88 (3d ed.

1977) and Feldstein, The Income Tax and Charitable Contributions:

11

make donations to an organization that does not appear

on the Cumulative List.” Id. Indeed, Bob Jones con

tended in that case that if it lost its tax exemption it

would lose all contributions from those who otherwise

take charitable deductions. See id. at 725 n.2. Consist

ently, in the present case evidence in the record shows

that, barely two weeks after Bob Jones’ tax exemption

was revoked, “as a result” the school experienced “a

decrease in the giving.” Joint Appendix in No. 81-3,

at 250.

The fact that- the tax benefits have consistently been

and continue to be of considerable tangible assistance

to private schools in general is well-documented. For

example, in Green v. Kennedy, supra, the court rested

its conclusion that federal tax benefits constituted “sub

stantial and significant” government support in part

upon the evidence, placed before it by the parties, which

was offered in an earlier federal court action involving

Mississippi private schools. In the earlier case, Coffey v.

State Educational Finance Commission, 296 F. Supp.

1387 (S.D. Miss. 1969), a three-judge court invalidated

a state law providing tuition grants to students attend

ing private, racially discriminatory schools. The Coffey

evidence showed that private discriminatory schools had

“flourished in the wake of desegregation rulings,” * 9 that

the schools were operated “on the thinnest financial

basis,” and that the tax benefits were an important, if

not indispensable, factor in the establishment and con

Part I—Aggregate and, Distributional Effects, 28 Nat’l Tax J. 81,

82 (1975), cited in Note, The Judicial Role in Attacking Racial

Discrimination in Tax-Exempt Private Schools, 93 Harv. L. Rev.

378, 387 n.50 (1979).

9 In this regard, evidence from the IRS demonstrated that while

no private school exemptions had been sought by Mississippi schools

prior to the state’s first desegregation suit (1963), such exemptions

were sought and applications were received steadily thereafter as

desegregation activity increased. Green v. Kennedy, supra, 309 F.

Supp. at 1135-36. See also note 23 at 23-24 infra.

tinued operation of the schools. Green v. Kennedy, supra,

309 F. Supp. at 1135.10 11 12

In addition, the court took special note that officials of

the private schools themselves regarded the tax benefits

as “psychological help to the school, from the public re

action to what was considered as approval by the Federal

Government.” Id.n Moreover, this federal “help” be

came of even greater importance to the schools after the

state tuition grants were eliminated. According to evi

dence relied upon by the court, solicitations for support

from the private schools stressed the loss of the state

grants, underscored the deductibility of contributions,

and stated that, in the absence of such deductible con

tributions, many students would be “forced” to return to

the public schools. Id, at 1135.18

Finally, the continuing importance of the tax benefits

to private schools was recently stressed by representa

tives of the schools in congressional hearings.13

10 For a summary of further evidence concerning the contribution

of the tax benefits to southern discriminatory private schools, see

Spratt, Federal Tax Exemptions for Private Segregated Schools, 12

Wm . & Mary L. Rev. 1, 3-5 (1970).

11 See McGlotten v. Connally, supra, 338 F. Supp. at 456, enjoin

ing the Secretary of the Treasury from granting tax exemptions

and deductibility of contributions to racially discriminatory fra

ternal organizations and their donors, in part because by ruling

that an organization is “charitable” under 26 U.S.C. § 170 “the

government has marked certain organizations as ‘Government Ap

proved’ with the result that such organizations may solicit funds

from the general public on the basis of that approval” ; see also

note 4 supra and accompanying text.

12 A solicitation letter quoted by the court stated that: “ [U]n-

less we receive substantial contributions to our Scholarship Fund

there will be many, many students, whose hands and bodies are

just as pure as any of their classmates and playmates . . . who for

financial reasons alone, will be forced into one of the intolerable

and repugnant ‘other schools,’ . . . or into dropping out of school

entirely . . . .” 309 F. Supp. at 1135.

l s E.g., 1979 Hearings at 555 (“Tax deductible contributions to

an independent religious school are critical in keeping tuition with-

12

is

Inasmuch as the tax benefits are, thus, of continuing

“tangible financial aid” to tax-exempt private schools,

and inasmuch as that aid is plainly used to finance vari

ous necessary expenses of operating those schools-—for

example, evidence in Coffey and in the cited hearing

statements indicates that tax-deductible contributions are

used to subsidize students’ tuition expenses—the “eco

nomic consequence” is, as the Court held in Norwood,

“to give aid” to those schools, 413 U.S. at 464. And if

any such school “engages in discriminatory practices,” as

the Court also held, the government through the aid nec

essarily “gives support to such discrimination.” Id. at

465.

There is no dispute in the present cases that through

the federal government’s conferral of tax benefits Bob

Jones and Goldsboro receive tangible financial aid which

is (or would be) used to meet continuing expenses of

those schools. Neither do those schools deny that they

engage in racially discriminatory practices which would

be constitutionally prohibited were they practiced in the

public schools.14 Instead, the two schools argue that the

in reach . . .”) (statement of Paul Kienel, Association of Christian

Schools International) ; id. at 388 (“Private schools are heavily

dependent on tax-free contributions”) (statement of W. Wayne

Allen, Chairman of the Board, Briarcrest Baptist School System,

Memphis, Tennessee) ; id. at 400 (tax-exemption and deductible

gifts are “of vital importance” for independent schools, accounting

for “23% of the operating budgets of our boarding schools and 11%

in our day schools”) (statement of John Esty, Jr., President, Na

tional Association of Independent Schools).

14 Before this Court, Bob Jones has abandoned its claim, urged

below, that its anti-miscegenation policies would be permissible if

enforced in the public schools. That such policies are racially dis

criminatory is well settled. Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967);

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964). As this Court said

in Loving: “There can be no doubt that restricting the freedom

to marry solely because of racial classifications violates the central

meaning of the Equal Protection Clause.” 388 U.S. at 12. The fact

that Bob Jones’ racial classifications apply to members of all races

14

federal aid supplied to them should not he constitution

ally prohibited by Norwood, since it amounts to only

an “indirect economic benefit” flowing from a “passive”

governmental decision not to tax the schools or the

schools’ contributors. Brief for Bob Jones at 20-21;

Brief for Goldsboro at 41-42. The schools’ sole support

for this claim is this Court’s decision in Walz p. Tax

Commission, 397 U.S. 644 (1970). Petitioners’ reliance

on that case is altogether misplaced.

The issue in Walz was whether granting property tax

exemptions to churches violated the Establishment Clause

of the First Amendment. Recognizing that the exemp

tions did, necessarily, “afford an indirect economic bene

fit” to the churches, id. at 664, the Court held that, for

purposes of Establishment Clause analysis, that fact in

itself was not controlling. Rather, the “judgment under

the Religion Clauses must . . . turn on whether particu

lar acts in question are intended to establish or inter

fere with religious beliefs and practices or have the effect

of doing so.” Id. at 669. As to the purpose of the

exemption, the Court relied on the historic, universally

approved tax exemption of churches in this country—an

approval that antedated the First Amendment itself—

and determined that this long practice was not based on

an effort by the state to support religion, but to assure

a “benevolent neutrality toward churches and religious

exercise generally . . . .” Id. at 676-77. Confirming this

“neutrality” of purpose was the fact that the tax exemp

tion was provided to various charitable institutions, not

solely to churches. Id. at 672-73. Regarding the second

issue, state “entanglement” with religion, the Court

determined that the tax exemption helped reduce rather

than increase the risk of such entanglement, since

“ [ejlimination of exemption would tend to expand the

involvement of government by giving rise to tax valua

does not make them any the less objectionable. Racial classifications

that are “even-handed” are nevertheless “repugnant to the Four

teenth Amendment.” Id. at 12 n .ll.

15

tion of church property, tax liens, tax foreclosures, and

the direct confrontations and conflicts that follow in the

train of those legal processes.” Id. at 674.

For at least four separate reasons, the Walz decision

is of no assistance to petitioners in the present cases.

First, the fact that aid, by way of a tax exemption, to

churches is permitted under the Establishment Clause

does not mean that a tax exemption (and other impor

tant tax benefits) can be granted to racially discrimina

tory schools consistent with the Equal Protection Clause.

Indeed, that is precisely what this Court held in Norwood:

The leeway for indirect aid to sectarian schools [for

Establishment Clause purposes] has no place in de

fining the permissible scope of state aid to private

racially discriminatory schools. “State support of

segregated schools through any arrangement, man

agement, funds, or property cannot be squared with

the [Fourteenth] Amendment’s command that no

State shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction

the equal protection of the laws.” Cooper v. Aaron,

358 U.S. 1, 19 (1958).

Norwood v. Harrison, supra, 413 U.S. at 464 n.7 (em

phasis supplied).

Second, while neutrality of purpose is the touchstone

of Establishment Clause analysis, and although in Walz

it was important that the tax exemption was afforded

to other charitable institutions, a. neutral and legitimate

governmental purpose will not validate a statute which

has the effect of supporting racially discriminatory

schools.15 As the Court said in Norwood, 413 U.S. at 466:

15 Thus, while a state may, consistent with the Establishment

Clause, make textbooks available to private religious schools if its

purpose is a “neutral” one, i.e., to make books available to all

schoolchildren in public and private schools alike, Board of Educ.

v. Allen, 392. U.S. 236 (1968), it cannot make those same books

available to private schools that are racially discriminatory, re

gardless of the “neutrality” of its purpose, Norwood v. Harrison,

supra, 413 U.S. at 466.

We need not assume that the State’s textbook aid to

private schools has been motivated by other than a

sincere interest in the educational welfare of all

Mississippi children. But good intentions as to one

valid objective do not serve to negate the State’s in

volvement in violations of a constitutional duty.

Third, even if neutrality of governmental purpose were

more important to a determination of the legitimacy of

the tax benefits in the present case than it is, Walz does

not control the outcome here. As stated above, that

decision rested in large measure on the long history of

tax exemptions accorded to churches and the “benevolent

neutrality” evidenced by that history. But, as the Court

has made explicit in cases examining other benefits to

sectarian schools, “ [w] e have no long history of state aid

to church-related educational institutions comparable to

200 years of tax exemptions for churches.” Lemon v.

Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602, 624 (1971). In fact, quite

the opposite is true of sectarian schools. “Strong opposi

tion has been evident throughout our history to the use

of the state’s taxing powers to support private sectarian

schools,” Id. at 642, 653-54 (separate opinion of Bren

nan, J.). “In sharp contrast to the undeviating accept

ance given religious tax exemptions from our earliest

days as a Nation, [citing Walz], subsidy of sectarian

educational institutions became embroiled in bitter con

troversies very soon after the Nation was formed.” Id.

at 645 (Brennan, J.).

Finally, if petitioners mean to argue, relying on Walz

and the Establishment Clause cases, that tax benefits are

not governmental aid at all because they are not a direct

payment to the schools, the argument is completely with

out foundation. As previously discussed, this Court indi

cated in Norwood that for constitutional purposes it con

siders tuition grants and tax benefits (which are used

to stimulate and indirectly pay for, among other things,

tuition expenses) to be identical. Moreover, in Com

mittee for Public Education v. Nyquist, supra, the Estab

16

17

lishment Clause ease decided the same day as Norwood,

the Court made explicit that governmental aid in the

form of tax benefits to sectarian schools is constitutionally

indistinguishable from direct governmental payments

made to those schools:

In practical terms there would appear to be little

difference, for purposes of determining whether . . .

aid has the effect of advancing religion, between the

tax benefit . . . and the tuition grant . . . . “ [I]n

both instances the money involved represents a

charge made upon the state for the purpose of

religious education.”

413 U.S. at 790-91 (quoting statement of Circuit Judge

Hays, dissenting below).

There is therefore no support in Walz and the Estab

lishment Clause cases for the view that “indirect” govern

ment aid by way of tax benefits can be excused when

“direct” aid would be constitutionally prohibited.16 In

deed, we submit that any other view of such aid would

flout the general principle, expressly applied in Norwood,

that government may not bring about indirectly what it

cannot constitutionally bring about directly: “a state

may not induce, encourage or promote private persons

to accomplish what it is constitutionally forbidden to

accomplish.” Norwood v. Harrison, supra, 413 U.S. at

465.

In sum, we submit that the Norwood decision—-which

has been consistently reaffirmed by this Court17 and by

16 For a further analysis of the constitutional and economic simi

larity between tax benefits and direct payments, see Brown, State

Action Analysis of Tax Expenditures, 11 H arv. C.R.-C.L. L. Rev.

97 (1976) ; Comment, Tax Incentives as State Action, 122 U. P a.

L. Rev. 414 (1973) ; cf. Surrey, Tax Incentives as a Device for

Implementing Government Policy: A Comparison with Direct Gov

ernment Expenditures, 83 Harv. L. Rev. 705, 711 (1970) (Mr.

Surrey was Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for Tax Policy

from 1961 to 1969).

17 See Gilmore v. City of Montgomery, 417 U.S. 556, 568-69

(1974); Runyon v. McCrary, supra, 427 U.S. at 171, 175-77; Maher

18

the lower courts in circumstances very similar to those

presented here “—compels the conclusion that the govern

ment’s conferral of the tax benefits at issue amounts to

unconstitutional support of Bob Jones’ and Goldboro’s

discrimination. We urge the Court to say so, unmis

takably, in these cases, .making clear beyond any doubt

whatever that the United States government cannot con

stitutionally support racially discriminatory practices, in

the schools of this nation.

II. THE GOVERNMENT’S DECISION NOT TO SUP

PORT RACIALLY DISCRIMINATORY PRIVATE

SCHOOLS DOES NOT VIOLATE PETITIONERS’

FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS.

Petitioners’ final contention is that the government’s

failure to support their schools with tax benefits violates

their rights under the Religion Clauses of the First

Amendment. They argue, first, that even if the govern

ment’s refusal to support racially discriminatory schools

is valid as a general rule, an exception to that rule must

be made in favor of those schools whose racial discrimina

tion is religiously based; otherwise, say petitioners, those

schools’ Free Exercise rights would be violated. Second,

petitioners argue that failure to make an exception for

their religiously based discrimination would violate the

Establishment Clause in that religions which do not

discriminate would be favored over those that do. Neither 18

V. Roe, 432 U.S. 464, 477 (1977) ; Flagg Bros., Inc. v. Brooks, supra,

436 U.S. at 163 (holding that the sovereign-function doctrine did

not support a finding that warehouseman’s proposed sale of goods

in storage was attributable to state and thus “state action” under

Fourteenth Amendment, but noting that its holding does not im

pair the precedential value of cases such as Norwood and Gilmore).

18 See, e.g., Brown v. Califano, 627 F.2d 1221, 1235 (D.C. Cir.

1980) ; Bob Jones University v. United States, 639 F.2d 147, 152-53

(4th Cir. 1980), cert, granted, 50 U.S.L.W. 3278 (U.S., Oct. 13,

1981) ; Iron Arrow Honor Soc. v. Hufstedler, 499 F. Supp. 496,

505-06 (S.D. Fla. 1980), aff’d 652 F.2d 445 (5th Cir. 1981), pet.

for cert, filed, 50 U.S.L.W. 3377 (Oct. 31, 1981); Grove City College

v. Harris, 500 F. Supp. 253, 267-68 (W.D. Pa. 1980).

19

of these arguments is in accord with the controlling stand

ards announced by this Court. The acceptance of either

would compromise the constitutionally rooted national

policy against racial discrimination in the country’s

schools. We treat only the Free Exercise claim here.

Before addressing this contention, however, we make

the following two observations about the assumptions

underlying petitioners’ arguments. If either assumption

is in error, then the petitioners’ Religion Clause argu

ments must fail.

First, if petitioners’ Walz argument—that the tax bene

fits disputed in this case cannot be deemed tangible

government aid for Equal Protection Clause purposes-—

were correct, then a fortiori the withdrawal of the schools’

tax-exempt status by the Service involves the loss of

such inconsequential assistance as not to trigger Free

Exercise or Establishment Clause concerns.1® As the

Court held in Norwood, “ [hjowever narrow may be the

channel of permissible state aid to sectarian schools, it

permits a greater degree of state assistance than may be

given to private schools which engage in discriminatory

practices that would be unlawful in a public school sys

tem,” 413 U.S. at 470 (emphasis supplied) (citations

omitted). We therefore proceed in this Argument on

the basis that the tax benefits at issue here do con

stitute “tangible government aid” to the schools.

Second, while we are also assuming in this discussion

that the withdrawal of benefits was in fact a “penalty”

upon petitioners’ exercise of a constitutional right, that

assumption may not be correct. In H am s v. McRae,

448 U.S. 297, 314-17 (1980), the Court distinguished

a refusal by government to finance a constitutionally

protected activity from a penalty imposed by government

upon the activity itself. In Harris the Court held that *

w See, e.g., O’Hair v. Paine, 312 F. Supp. 434, 437 (W.D. Tex.

1969), appeal dismissed, 397 U.S. 531 (1970), aff’d 432: F.2d 66

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 955 (1971).

20

the government could choose to subsidize certain medical

services, intentionally excluding abortions, even though

the right to an abortion is constitutionally protected.20

Similarly, the government here has chosen to support only

certain charitable institutions, excluding those that are

racially discriminatory; the excluded institutions may

have a constitutional right to be discriminatory, but they

have no constitutional right to receive government sup

port for that discrimination.

We are in general agreement with petitioners con

cerning the basic elements to be considered in reviewing

their claim that the government’s refusal to grant them

tax benefits has unconstitutionally interfered with their

Free Exercise rights: (1) the nature of the burden, if

any, which has been placed on their right; (2) the nature

of the governmental interest at stake; and (3) an as

sessment whether, on balance, the governmental interest

is sufficiently compelling to justify the particular burden

placed upon the Free Exercise right. See Brief for

Goldsboro at 33; Brief for Bob Jones at 23. We differ

with petitioners, however, concerning the nature of the

burden, the nature of the governmental interest, and

the appropriate balancing of the two.

A. The Burden on Petitioners’ Free Exercise Rights

Is Not Significant.

The most comprehensive description of the showing

necessary to demonstrate that a significant burden has

been placed upon Free Exercise rights was given by

this Court in Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972).

20 The result would be different, said the Court, analogizing- to

Sherbert v. Verner, 874 U.S. 398 (1963), if the government chose

to withdraw all medical benefits from a woman because she chose

to have an abortion; such withdrawal would be similar to the with

drawal of all employment benefits from Mrs. Sherbert because she

chose not to work one day per week on her Sabbath. 448 U.S. at

317 n.19. The present cases, we believe, are much more like Harris

than Sherbert.

A comparison of this case with Yoder illustrates how

minimal a burden on their religious beliefs and practices

has been suffered by Goldsboro and Bob Jones.

In Yoder, members of the Amish religion challenged

the constitutionality of a statute which required them

to send their children to public schools through age 16.

This Court acknowledged the state’s considerable interest

in the education of its citizens but concluded that the

Amish had carried their burden of overcoming that

interest:

Aided by a history of three centuries as an iden

tifiable religious sect and a long history as a success

ful and self-sufficient segment of American society

the Amish in this case have convincingly demon

strated the sincerity of their religious beliefs, the

interrelationship of belief with their mode of life,

the vital role that belief and daily conduct play in

the continued survival of Old Order Amish commu

nities and their religious organization, and the haz

ards presented by the State’s enforcement of a

statute generally valid as to others. Beyond this,

they have carried the even more difficult burden of

demonstrating the adequacy of their alternative mode

of continuing informal vocational education in terms

of precisely those overall interests that the State

advances in support of its program of compulsory

high school education.

406 U.S. at 235. The Court’s opinion underscored four

factors important to its decision.

First, the burden of the challenged statute on the

Amish practices was “not only severe, but inescapable,”

in that it directly compelled them to violate their reli

gious beliefs. In this respect, the Court indicated that

the Amish burden was greater than that presented in

Braunfeld v. Brown, 366 U.S. 599, 605 (1961), where

no such compulsion was presented, but merely a state

regulation which made religious practices more expensive.

Second, the Court stressed the importance of the fact

that the case was “not one in which any harm to the

physical or mental health of the child or to the public

21

22

safety, peace, order, or welfare has been demonstrated

or may be properly inferred. Id. at 230. “A way of life

that is odd or even erratic but interferes with no rights

or interests of others is not to be condemned because it is

different.” Id. at 224. Third, the Court stated that “ [i]t

cannot be overemphasized that we are not dealing with

a way of life and mode of education by a group claim

ing to have recently discovered some ‘progressive’ or

more enlightened process for rearing children for mod

ern life.” 406 U.S. at 235. Finally, the Court made

plain that since the state’s educational interest is a

“strong” one, it is important that the courts move with

“great circumspection” before requiring that exemptions

be made from that interest, and that the entitlement to

an exemption demonstrated by the Amish was one that

“few other” religious groups could make. Id. at 235, 236.

Quite unlike Yoder, Bob Jones and Goldsboro are

unable to demonstrate that racial discrimination is at

the heart of their religious beliefs.21 Even more signifi

cant, neither school suffers a direct, inescapable burden

upon its religious practices. Rather, as was true in

Braunfeld v. Brown, supra, the government’s decision

not to confer tax benefits on those schools which are

racially discriminatory has merely made operation of

petitioners’ schools more expensive. It is clear that this

is a lesser burden than would be a direct governmental

compulsion forbidding Bob Jones’ or Goldsboro’s dis

criminatory practices.22

We submit, therefore, that the burden on petitioners’

Free Exercise rights is not substantial. They have shown

21 See Brown v. Dade Christian Schools, Inc., 556 F.2d 310, 314,

321-22 (5th Cir. 1977) ( en banc) (Goldberg, J., concurring), cert,

denied, 434 U.S. 1063 (1978).

22 In fact, the Braunfeld plurality specifically listed, as an exam

ple of an indirect burden on free exercise, a limitation on the tax

deductibility of a religious contribution. 366 U.S. at 606. See also

Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361, 385 (1974) (denial of veterans’

benefits to conscientious objector who performed alternative service

imposed only indirect burden on free exercise).

nothing more than that the exercise of one particular

religious practice has become somewhat more costly. We

do not say that this is no burden at all. We do say,

however, that the burden has not been shown to be sig

nificant under the standards set by this Court.

B. The Governmental Interests at Stake are Com

pelling and Constitutionally Based.

Bob Jones contends in its brief (at 29) that the only

governmental interest furthered by the withdrawal of tax

benefits is “an indefinitely stated federal policy respecting

race.” Goldsboro goes even further and claims (at 38)

that “the policy against racially discriminatory admis

sions practices based on the sincere religious beliefs of

sectarian schools has not been mandated by either Con

gress or the courts but rather has been independently

formulated by the IRS itself.” These assertions are sim

ply not true. The public interest being furthered in these

cases has been explicitly and repeatedly articulated by the

Congress and by this Court. The source of this interest

is most certainly not the IRS’ independent, open-ended

view of public policy; rather, it is derived from the Con

stitution itself. Thus, affirmance of the judgment below

does not confer upon the Service unbridled discretion to

define “the national interest” and to deny or withdraw

tax exemptions on that basis.

As we described earlier, the constitutionally based na

tional policy against racial discrimination in education

was first given recognition by this Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, supra. It extends to private schools

both because black children excluded from such schools

on the basis of race suffer the same injury and humilia

tion as black children excluded from public schools on

the basis of race, and because the growth of discrimina

tory private schools tends to undermine governmental

efforts to end racial discrimination in the public schools.23 28

28 The relationship between public school desegregation and the

creation or expansion of segregated private schools—as well as the

detrimental effects of such schools on constitutionally mandated

23

As described in the previous Argument, beginning in the

late 1950’s and culminating in the 1973 decision in

Nonvood v. Harrison, the federal courts gave specific

public school desegregation—has been well documented. For exam

ple, the Fifth Circuit noted as early as 1966:

Private schools, aided by state grants, have mushroomed in

some states in this circuit. The flight of white children to

these new schools and to established private and parochial

schools promotes resegregation.

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.2d 836, 848-

49 (1966), aff’d en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub

nom. Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840

(1967) (footnote omitted). See also U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights,

Southern School Desegregation 1966-67 71 (1967).

Many others have documented the relationship between the de

velopment of private academies and public school desegregation.

See, e.g., D. Bell, Race, Racism and A merican Law 496-97 (1973);

D. N evin & R. Bills, T he Schools That F ear Built— Segrega

tionist Academies in the South 12 (1976); Southern Regional

Council, T he South and H er Children : School Desegregation

1970-71 69-70 (1971) ; U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights, School De

segregation in Ten Communities 17, 29, 36, 80 (1973); Part 3D:

Desegregation Under Law, Hearings Before the Select Committee

on Equal Educational Opportunity of the United States Senate, 91st

Cong., 2d Sess. (1970); Commentary, Civil Rights—i2 U.S.C. 1981:

Keeping a Compromised Promise of Equality to Blacks, 29 U. F la.

L. Rev. 318, 324 n.40 (1977) ; Note, Segregation Academies and

State Action, 82 Yale L.J. 1436, 1445-46 (1973) ; Brown, Acade

mies: Many Parents Would Give Children Bad Educations, South

Today, Dec., 1970, at 12; Brown & Provizer, The South’s New Dual

School System: A Case Study, New South, Fall, 1972, at 59; Miles,

Private Schools: Enrollment Almost Triples in Tarheel State, South

Today, Dec., 1971, at 5-6; Tergen, Closeup on Segregation Acade

mies, N ew South, Fall, 1972, at 50; Tergen, Private Schools,

Charleston Style, South Today, Jan./Feb., 1971, at 1; Instant

Schools, N ew sw eek , Jan. 26, 1970, at 59.

Courts have also long recognized the relationship between private

academies and public school desegregation. See, e.g., Gilmore v.

City of Montgomery, supra-, Norwood v. Harrison, supra-, Griffin v.

County School Bd. of Prince Edward County, supra-, Brumfield v.

Dodd, 405 F. Supp. 338 (E.D. La. 1975); Green v. Connally, supra-,

Coffey v. State Educ. Fin. Comm’n, supra; Poindexter v. Louisiana

Fin. Assistance Comm’n, 275 F. Supp. 833 (E.D. La. 1967), aff’d

389 U.S. 571 (1968) ; Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 197

F. Supp. 649 (E.D. La. 1961), aff’d 368 U.S. 515 (1962).

24

application to this clear national policy against private

discrimination in education. Some of the decisions were

premised on the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

Others, such as Green v. Connolly, supra, were premised

on the nation’s policy against racial discrimination as

reflected in civil rights statutes and the pronouncements

of this Court.24

The Congress ratified the Brown holding and rein

forced the ban on federal support for segregated educa

tion in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000c-

2000d-4. This statute, which rests upon Congress’ power

under the Fourteenth Amendment, has been construed to

prohibit recipients of federal assistance from permitting

students attending racially discriminatory private schools

to participate in federally funded programs.25 The Con

gress also exercised its Thirteenth Amendment power to

prohibit all racial discrimination in education, whether

or not supported with federal funds. 42 U.S.C. § 1981;

see Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976).26 * 28

24See also Bittker & Kaufman, Taxes and Civil Rights: "Con

stitutionalizing” the Internal Revenue Code, 82 Yale L.J. 51, 76

(1972) (“There is. an abundance of evidence supporting the Green

theory that segregated educational facilities contravene public

policy; while public rather than, private schools are the primary

focus of this emphasis on racially open education, in Green the

court was able to muster a number of earlier judicial decisions

extending the same principle to private education”).

26 See 41 Fed. Reg. 35553 (August 23, 1976). Section 601 of

the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 2000d, provides that racial discrimination

cannot be practiced in “any program or activity receiving Federal

financial assistance.” Tax benefits to private schools are included

within this prohibition. See, e.g., McGlotten v. Connally, supra,

338 F. Supp. at 460-61, in which the three-judge court held that

assistance provided through the tax system is “Federal financial

assistance” within the meaning of the Act.

28 In an effort to lend support to its contentions that the IRS

is the sole source of our nation’s policy against racial discrimina

tion in private schools, Goldsboro argues that Runyon is irrelevant

to the present case because it reserved the question of the appro

priate application of § 1981 to a school that discriminates on

religious grounds. Brief for Goldsboro at 39. But this is not so.

Even if in a particular case the First Amendment might give rise

25

26

In summary, we submit that this nation has a strong,

clearly defined, constitutionally rooted policy against

racial discrimination in all schools of this country, and

has a constitutional ban against any governmental sup

port for such discrimination. The sources of this policy

and ban are the Fifth, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth

Amendments to our Constitution. As is next discussed,

petitioners have not shown themselves to be entitled to

an exemption from these compelling governmental in

terests.

C. The Government’s Interests are Sufficiently Com

pelling to Outweigh the Minimal Burden on P eti

tioners’ Free Exercise Rights.

We agree with petitioners that resolution of their

Free Exercise claim requires a balancing of their in

terests against those of the public. This Court has

recently indicated that such a balancing is a “delicate”

process, McDaniel v. Paty, 435 U.S. 618, 628 n.8 (1978),

one that requires a “sensitive and difficult accommodation

of the competing interests involved.” Id. at 635 n.8

(Brennan, J., concurring in the judgment). It is for

this reason that the inquiry into the precise nature of

to a defense sufficient to defeat § 1981’s application to a sectarian

school’s racial discrimination, it would not be because § 1981 and

the government’s constitutionally rooted policies did not apply to

that school. Rather, it would be because § 1981 and its underlying

policies were overridden by a more important policy. Fiedler v.

Marumsco Christian Schools, 631 F.2d 1144, 1150 (4th Cir. 1980)

(holding that in a § 1981 action, “the sectarian nature of the school

is important only insofar as it may give rise to a constitutional

defense to the claim [of racial discrimination]”). See Note, Section

1981 after Runyon v. McCrary: The Free Exercise Right of

Private Sectarian Schools to Deny Admission to Blacks on Account

of Race, 1977 Duke L.J. 1219, 1252 [hereinafter cited as “1977

Duke L.J.”] (“Although Runyon’s holding was limited to non

sectarian schools, this governmental interest remains unchanged

when a sectarian school asserts a free exercise claim as a defense

to a section 1981 action. The only difference is that the courts

must now determine whether the government’s . interest is sufficient

to outweigh the opposing first amendment claim”).

27

each of the competing interests—including an examina

tion of the ramifications of preferring one or the other

interest—must be as thorough as that undertaken by

this Court in Yoder. In our view, petitioners have

either overlooked or misjudged most of the important

elements in this balancing process.

First, petitioners have woefully mischaracterized the

government’s interest. As we have shown above, what

is at stake here is not a vaguely conceived, unsupported

IRS view of public policy, but rather, constitutionally

rooted and constitutionally compelled public interests of

the highest order—interests that have been given explicit

voice and definition by this Court, and the Congress.

There can be no doubt that the government’s interest

in carrying out constitutional obligations is a “com

pelling” one, even in the face of a First Amendment

claim. See Widmar v. Vincent, 50 U.S.L.W. 4062, 4064

(U.S., Dec. 8, 1981).

Second, quite unlike the cases heavily relied on by

petitioners—Sherbert v. Vemer, 374 U.S. 398 (1963)

and Thomas v. Review Board, 101 S.Ct. 1425 (1981)27—

here the government’s interest is enhanced still further

by the number of other exemptions that may have to be