Discovery Schedule Order

Public Court Documents

July 9, 1998

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Discovery Schedule Order, 1998. 9680487f-dd0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/14769d2e-3916-4523-a7ae-6819db29218e/discovery-schedule-order. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

v JUL-27-88 MON 10:01 NAACP LDF DC OFC FAX NO. 2026821312 oh O2/b

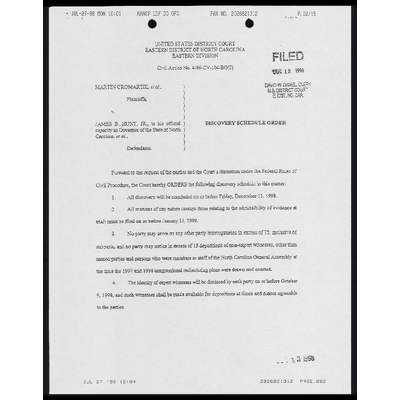

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

TERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLTN A

EASTERN DIVISION FLEE 5

Civil Acton No. 4-56-CV-104-BO(3)

Yuk 18 1998

MARTIN CROMARTIE, #i al. ) DAVID W. DANIEL, CLERY MARTIN CROMARTIE, 2 0. DISTRIC: COURT

Plainuffs 3 = TST. NC. CAR.

)

V. )

)

JAMES B. HUNT, JR.. in kis official ) DISCOVERY SCHEDULE CRDER

capacity a3 Govemor of the State 0S North }

Cerclina. eral, )

)

Defendants. }

Pursuant 10 the request of tae vargas aad the Court's discregon under he Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, the Court hereby ORDERS tae foilowing discovery scheduic w thas mauer:

i All discovery will be coucluded on or before Friday, December 11. 1998.

e.0 Al motiaps of 2ny mame (axcspt those relating to the admissibility of evidence at

wal must o2 filed on or befere Jamuary 15. 1999.

s. No party may sarva on any other party inerogatories 2 excess of 73. mclusive ¢i

suboarts, anf no party mzy notice ir. excass of 15 depositions of non-expert wimesses, oder than

named parties and persons who weze members or sta of the North Carolina General Assembly at

the ame the 1927 and 1956 congressional redistricting plecs were drawn and enacted.

4. The idexticy of expert witnesses will o< disclosed by each party on or before October

a, 1998, and such witnesses shall be made available Sor dzpositions at timzs and places agreeable

to the partes.

JUL 27 88 10:84 2026821312 PRGE .282

. JUL-27-88 MON 10:01 Sri NAACP LDF DG OFC FAX NO, 2026821312 P. 03/15

< The parses Saal make a good fzith etfort to disclose the idzosty of all inal witnesses

on Or heroes Dczober 16, 1998. ogeder viith a brief stetomett of What a party prepoases 10 establish

pv hell esumony.

6. A final nre-trial conference and trix will be scnedzled by susequent ordaT.

0 ORDERED.

yr

This ine dav of Lady 1698.

For the Cow:

PERRENCE W. BOYLE

CHIEF UNITED STATES Di CT COURT JUDGE

)

JUL 27 '88. 18:84 2826821312 PAGE .BBA3