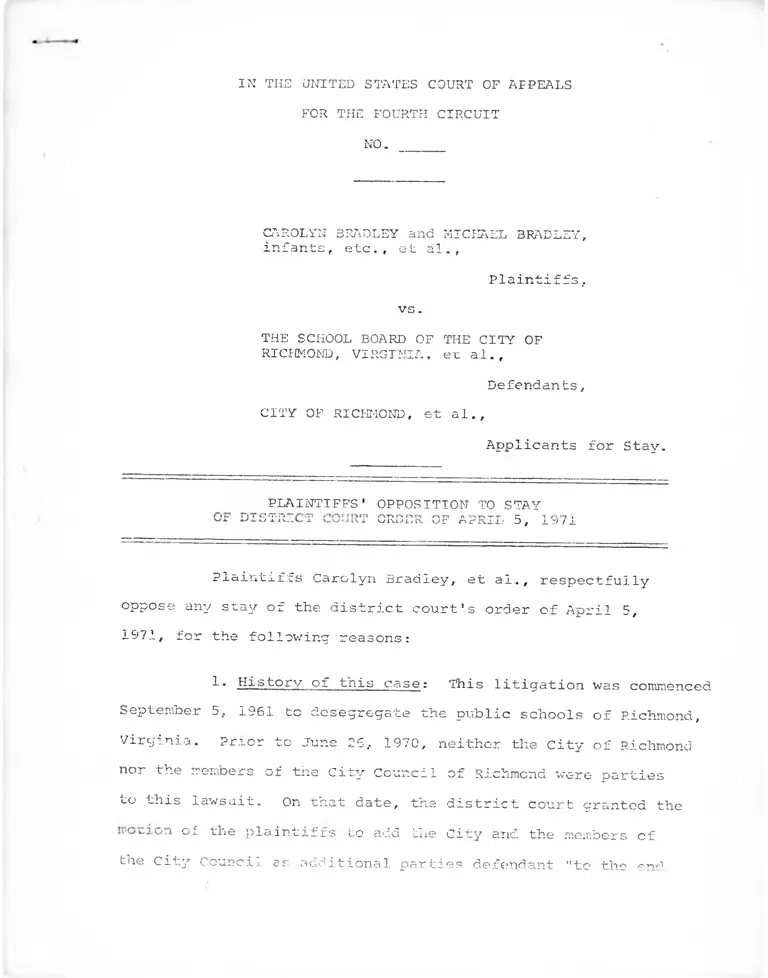

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Plaintiffs' Opposition to Stay of District Court Order of April 5, 1971; Motion of Defendant, School Board of the City of Richmond for Modification of the Order of This Court of April 5, 1971

Public Court Documents

April 5, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond Plaintiffs' Opposition to Stay of District Court Order of April 5, 1971; Motion of Defendant, School Board of the City of Richmond for Modification of the Order of This Court of April 5, 1971, 1971. efc9aac6-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/147a2731-5692-49df-9df9-8ce1e863fa6a/bradley-v-school-board-of-the-city-of-richmond-plaintiffs-opposition-to-stay-of-district-court-order-of-april-5-1971-motion-of-defendant-school-board-of-the-city-of-richmond-for-modification-of-the-order-of-this-court-of-april-5-1971. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF AFPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO.

CAROLYN BRADLEY and MICHAEL BRADLEY, infants, etc., at ai.,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OF

RICHMOND, VIRGTNIA, et a1.,

Defendants,

CITY OF RICHMOND, et al.,

Applicants for Stay.

PLAINTIFFS

7 rr.T-, m

j -L a.

OPPOSITION TO STAY

o r> T> «"> r sr ~ t a r-> t- r~ t «w i\ L V in \ o r r-v zr D t jl ~J / ±

Plaintiffs Carolyn Bradley, et al., respectfully

oppose any stay of the district court's order of April 5,

1971, for the following reasons:

1* History of tnis case: This litigation was commenced

September 5, 1961 to desegregate the public schools of Richmond,

Virginia. Prior to June 26, 1970, neither the City of Richmond

nor the members of the City Council of Richmond were parties

to this lawsuit. On that date, the district court granted the

o L th0 plaintiff its to add the Citv sue the members cf

tae City Council as additional parties defendant “to the <?nrl

that whatever injunctive order embodying a new plan of deseg

regation may be issued by this Court shall be binding on all

parties having responsibility for the Richmond public schools."

The current proceedings commenced March 10, 1970

when plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further Relief alleging

that the "freedom of choice" plan of desegregation then

operative in Richmond had failed to create a unitary school

system. Following issuance of a "show cause" order, the

school board conceded at a pre-trial conference March 31, 1970

that "the public schools of the City of Richmond are not being

operated as unitary schools in accordance with the most recent

enunciations of the Supreme Court of the United States." The

district court also specifically found free choice constitu

tionally insufficient and vacated its prior order of March 30,

1966 approving freedom of choice; the school board was directed

to submit a new plan.

The first plan submitted by the board in 1970 was

drafted by representatives of the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare and was rejected by the district court

as equally insufficient as free choice to disestablish the

dual school system in Richmond. The second 1970 plan,

devised by the administrative staff of the school system, was

also found to be \iltimately insufficient by the court, but

it was ordered implemented for the 1970-71 school year as an

"interim plan." The City of Richmond and the School Board

of Richmond appealed from the district court's determination

- 2-

that the HEW plan was insufficient but. that appeal has not

yet been disposed of because of delays granted by this Court

at the instance of the City and the School Board, discussed

below and in the district court's April 5 opinion.

The City also sought a stay of the district court's

August 17, 1970 order requiring 1970-71 school year imple

mentation of the "interim plan" but its successive requests

for such a stay were denied by the district court [Chief

Judge Hon. Walter E. Hoffman] on August 27, 1970, by this

Court [Chief Judge Hon. Clement Haynsworth, Jr.] on August

28, 1970, and by the Supreme Court of the United States [Chief

Justice Hon. Warren E. Burger] on August 29, 1970.

The appeals by all parties from the district court's

August 17, 1970 order were docketed in this Court on October

19, 1970. On October 23, 1970, the City Council of Richmond

filed a motion in this Court to defer briefing and disposition

of the appeals until 40 days after the Supreme Court of the

United States rules in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ,, now pending on certiorari from this Court. A similar

motion was filed by the School Board of the City of Richmond;

although plaintiffs filed opposition to the motion, this Court

by order of November 6, 1970 did defer further consideration

of the appeals involving the "interim plar" until after the

Supreme Court rules. Plaintiffs sought rehearing en banc of

that order, whicf was denied on December 1, 1970.

-3-

The district court's opinion of August 17, 1970

specifically held that the "interim plan" was incapable of

creating a unitary school system in Richmond, and that more

would have to be done for the 1971-72 school year. The

accompanying order therefore directed the defendants

to file with this Court, within 90 days

from this date, a report specifically

setting out such steps as they may have

taken in order to create a unitary system

of the Richmond public schools and

specifying in said report the earliest

practical and reasonable date that any

such system could be put into effect..

The parties are reminded that the

approval referred to in paragraph 1 of

this order is not to be interpreted as

a finding that the implementation of that

plan results in a unitary system of schools.

Thus the City could have sought an expeditious determination

of its appeal from the August 17, 1970 order and in that manner

resolved the issue which it new7 suggests warrants a stay:

whether the further steps which the district court has now

ordered, even beyond the "interim plan", are legally required

to bring about a unitary school system in the City of Richmond.

Three new plans were filed in January, 1971 by the

School Board of Richmond to comply with the provisions of the

August order, each purportedly calculated to bring about a

unitary school system in Richmond upon their implementation in

the 1971-72 school year. Following further hearing in March,

1971, the district court entered the order of which stay is

sought on April 5, 1971, requiring implementation of one of

the plans submitted by the school board effective with the

beginning of the 1971-72 school year.

_4_

2. The present application for a stay attempts to

manufacture a legal issue which does not exist in this case,

as is amply demonstrated by the frivolous citation of Erie R.

Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64, in this non-diversity action

brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §1983 and 28 U.S.C. §1343. The

federal courts have general discretionary power to frame their

equitable relief in such a manner as to make the remedy

accompanying a declaration of rights effective. See, in

general, Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965).

Almost every desegregation decree ordered by any court has

involved the expenditure of public funds in order to overcome

the effects of past expenditures of funds to maintain and

preserve segregation. As early as 1946, the Supreme Court

said that

where federally protected rights have

been invaded, it has been the rule

from the beginning that courts will be

alert to adjust their remedies so as to

grant the necessary relief.

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678, 684; see also, Griffin v. County

School Bd. of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964);

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School Dist., 427 F.2d 319 (5th

Cir. 1970) ; Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United States,

415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969); United States v. School Dist. No.

151, 301 F. Supp. 201 (N.D. 111. 1969); Pettaway v. County

School Bd. of Surry County, 230 F. Supp. 480 (E.D. Va. 1964);

Hosier v. Evans, 314 F. Supp. 316 (D.V.I. 1970); cf. Sullivan

v. Little Hunting Park. 396 U.S. 229, 238-40 (1969); Jones

v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 414-15 n.14 (1968).

-5-

This Court in Swann v. Chariotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., 431 F.2d 138 (4th Cir. 1970) stated that "[o]pposition

to . . . bussing . . . cannot justify the maintenance of a

dual system of schools" and in that case approved a portion of

a desegregation plan which required additional transportation

of pupils and the consequent acquisition by the school board

of additional transportation facilities. This Court's language

in Swann that "[b]ussing is neither new nor unusual. It has

been used for years to transport pupils to consolidated schools

in both racially dual and unitary school systems" is echoed

by the district court's finding in this case that the School

Board of Richmond, an entity funded by the City Council of

Richmond, has in the past utilized busing for the purpose of

segregating students — a policy and practice of segregation

which traditionally required extra expenditures from public

funds for the operation of the public schools of Richmond.

3. It is significant to note that it is not the

School Board of the City of Richmond which here seeks to stay

the decision of the lower court. That party has sought some

modification of other provisions of the district court's order

in a motion filed with the district court [appended hereto

as Exhibit "A"], but in said motion it has specifically advised

the district court that it does not seek to stay the court's

order with respect to the requirement that buses be purchased.

It is also a fact: on this record that the School Board previ

ously purchased a similar number of buses for the purpose of

operating a complete school bus transportation system in an

- 6 -

are, formerly of Chesterfield County, recently annexed to the

City of Richmond. No opposition to that purchase was forth

coming from the City of Richmond; funds were made available

to the School Board for said purchase. It was contemplated

at that time that the majority of the pupils to be transported

would be white, and the transportation of said pupils would

be to predominantly white schools. Subsequent orders of the

district court have required the utilization of some of these

new vehicles to transport not only white children, but also

black children, as an aid to desegregation of the school

system of the City of Richmond.

4. The State may not decline to provide the funds

necessary to effectuate the Fourteenth Amendment right to

equal educational opportunity because of cost. See Shapiro

v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969).

5. The stay presently sought is for the purpose of

delaying desegregation of the Richmond schools. First of all,

should the Supreme Court in Swann establish lesser consti

tutional standards than this Court enunciated and the district

court applied in framing its order, as the court below put it

the expense and disruption of conversion

to a less costly program of integration

will in all probability be far less than

the cost of a hasty reorganization to

conform to current law, if such law

remains viable.

Furthermore, the City makes no representation of any irrep

arable injury resulting from the immediate execution of the

district court's order. In fact, counsel for the School Board

-7-

stated at the April 7 district court hearing on the stay

(transcrijjt of which has been ordered but is not yet avail

able) that if additional buses were purchased but the court's

order were not required to be implemented in September, the

new buses could be utilized anyway or be disposed of without

significant financial loss. Far more irreparable would be

the harm if a stay issued and the district court's order was

subsequently upheld, but because early orders were not placed,

buses to implement the order were not available in September.

A stay would lead to a recurrence of the situation which

required the district court to approve an unconstitutional plan

for 1970-71 on an "interim" basis.

6. On August 28, 1970 the City of Richmond applied

to the Chief Judge of this Court for a stay pending appeal

from the August 17 order of the district court directing

implementation of the "interim plan." It is significant that

the School Board did not at that time request such a stay.

Chief Judge Haynsworth, quoting from the opinion of Judge

Craven in Scott v. Winston-Salem/Forsvth County Bd. of Educ.

of August 20, denied the stay and said,

Prior decisions of the Supreme Court in

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Board, 396 U.S. 90 (1970) and Alexander

v. Holmes County Board of I:ducation, 3 96

U.S. 19 (1969) and of this court in

Stanley v. Darlington County School

District, 424 F.2d 195 (4th Cir. 1970)

leave no doubt that 'there remains no

judicial discretion to postpone immed-

iate implementation' of this plan. 424

F 2d at 196. The import of these cases

is clear. Plans effectuated by district

1 courts must be first implemented, then

- 8-

litigated. See Nesbit v. Statesville

City Board of Education, 418 F.2d 1040

(4t.h Cir. 1969). Any doubt that I

might, yet entertain with regard to my

lack of authority as a single circuit

judge to enter the stay order is

removed by the mandate of the Supreme

Court entered June 29 in Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

399 U.S. 926 (1970). In remanding to

the district court the Supreme Court left

undisturbed the judgment of the Fourth

Circuit 'insofar as it remands the case

to the district court for further

proceedings,' but the Supreme Court

ordered that 'the district court's

judgment is reinstated and shall remain

in effect pending those proceedings.'

Whatever my own viewpoint may be about

the common sense of putting into effect

complicated changes in a school system

prior to final adjudication, I am

convinced by the authorities cited that

the question is not one I may properly

considered. The motion for stay pending

appeal is therefore denied.

7. The Supreme Court of the United States has

consistently refused to postpone school desegregation by issu

ing stays or declining to vacate such stays when granted by

lower courts. See, e.g., Lucy v. Adams, 350 U.S. 1 (1955);

Houston Independent School Dist. v. Ross, 364 U.S. 803 (1960);

Danner v. Holmes, 364 U.S. 939, 5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1092 (1961)

(refusing to reinstate a stay dissolved by Chief Judge Tuttle

of the Fifth Circuit in Holmes v. Danner, 5 Race Rel. L. Rep.

1091 (1961)); Boomer v. Beaufort County Bd. of Educ. (August

30, 1968)(unreporeed order of Mr. Justice 3lack, vacating

stays granted by this Court). Recent actions of the Supreme

Court, both before and after oral argument in Swann, make it

clear that the Court did not intend to vitiate the rule of

-9-

Alexander when it granted review in Swann. E.g. , Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd, of Educ., No. 281, O.T. 1970 (August

25, 1970) (unreported order of full court denying requested

stays, pending disposition of Swann on meri'es, of school

desegregation in Charlotte, Winston-Salem, Fort Lauderdale

and Miami); Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ. of Nashville and

Davidson County v. Kelley (February 3, 1971)(unreported order

of Mr, Justice Stewart, denying application for stay, pending

certiorari, of requirement that proceedings in school

desegregation case continue); Cotton Plant School Dist. No. 1

v. United States (February 10, 1971)(unreported order of Mr.

Justice Blackmun, denying stay pending certiorari of district

court order requiring immediate implementation of desegregation

plan); Eckels v. Ross (March 1, 1971) (unreported order of full

Court denying stay, pending certiorari, of modifications to

desegregation plan ordered by United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit).

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs respectfully pray that the

stay be denied.

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

LOUIS R. LUCAS

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JAMES R. OLPHIN

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

M. RALPH PAGE

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginra 23219

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

- 10-

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EOR TilE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

CAROLYN BRADLEY and MICHAEL )

BRADLEY, infants, etc., ct al ))v. ) CIVIL ACTION

) No. 3353

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY )

OF RICHMOND, VIRGINIA, et al )

MOTION OF DEFENDANT, SCHOOL BOARD OF THE

CITY Pi' RICHMOND ?(T MODIFICATION OF THE ORDER

OF THIS COURT OF APRIL 5, 19~7I

Defendant School Board of the City of Richmond, by counsel

moves this Court to modify its Order of April 5, 1971, and as

grounds therefor states that it believes a compelling reason for

the timing of the Court's Order of April 5, 1971, was the assur

ance that there would be adequate time for the acquisition of

transportation facilities required to implement Plan III.

In view of the Court's emphasis that defendants take

immediate steps to obtain sufficient transportation facilities,

the School Board respectfully represents unto the Court as follows

1. It will forthwith request of the City Council of the

City of Richmond sufficient funds to purchase what the School

Board determines to be the necessary number of buses for the

beginning of the school year 1971-72, said buses to be available

for use no later than September 1, 1971, and in^no event shall the

number of buses be less than .56.

2. The orderly implementation of Plan III can be accom

plished within a period of 60 days.

In view of the foregoing representations, the Richmond

School Board requests this Court to modify its Order of April 5,

1971, and as further support thereof states the following:

;

1. The modification of the Court's Order of April 5,

| 1971, would eliminate t.he necessity of an additional appeal at

the present time when all counsel are engaged in active and

detailed preparation for extended hearings before this Court

commencing April 26, 1971. Such a modification, in light of this

defendant's representations, would not prejudice the rights of

the plaintiffs to the relief afforded by the Court's latest Order.

2. Additional time would be available for this Court and

the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals to receive expected guidelines

from the Supreme Court concerning the law of desegregation, thus

enabling all Orders and plans to be reviewed and modified with

greater accuracy and assurance. The awaiting of such guidelines

for an additional sixty (60) days would not prejudice the rights

of the plaintiffs to the relief afforded by the Court's latest

Order.

3. The pending appeals of this Court's Order of August

17, 1970 could be processed in logical sequence, including the

predictable course that following the High Court decision, all

such existing appeals will be remanded for reconsideration con-

j sistent with the Supreme Court's directives.

4. There is a distinct liklihood that a definitive order

may be forthcoming from this Court prior to June 30, 1971 on the

question of consolidation of the school systems of the City of

Richmond and the Counties of Chesterfield and Henrico. While

such a consideration cannot and did not influence the Court in

deciding the relief granted on April 5, (as noted in the Court’s

memorandum opinion), such a determination is extremely important

to all of the parties most directly affected by the Order of

April 5 and deserves the Court's consideration in light of the

representations made.

- 2 -

' ! "

i

L

Wherefore, the School Board of the City of Richmond

requests the Court to modify its Order of April 5, 1971, to

require that the School Board of the City of Richmond and the Cit '

Council of the City of Richmond take immediate action to acquire

by purchase or lease the number of buses which the School Board

determines to be necessary for the opening of schools in

September, 1971, and in no event less than 56 buses, and that

such acquisition of buses not cause any reduction in educational

effort or the discontinuance or reduction of courses, services,

programs, or extra-curricular activities which traditionally are

offered, and that the necessity of further steps toward implemen

tation of Plan III be deferred until further order of this Court,

either sua sponte, or on motion of any party.

Respectfully submitted,

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE CITY OFRICHMOND

George B. Little

Browder, Russell, Little & Morris 1510 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Conard B. Mattox, Jr.

City Attorney

402 City Hall

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J. Edward Lawler

615 Mutual Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

CERTIFICATE

I hereby certify that Norman J. Chachkin, counsel of

record for the plaintiffs was notified on April 6, 1971, that the

3

defendant Richmond School Board would present the foregoing

Motion to the Court on April 7, 1971/ and that copies of this

Motion were mailed thereafter to all counsel of record this

7th day of April/ 1971, as follows:

James R. Olphin, Esquire

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Frederick T. Gray, Esquire 510 United Va. Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Walter E. Rogers, Esquire

510 United Va. Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia 23219

John S. Battle, Jr., Esquire 1400 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

R. D. Mcllwaine, III, Esauire P. O. Box 705

Petersburg, Virginia 23803

Louis R. Lucas, Esquire

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Oliver D. Rudy, Esquire

Commonwealth Attorney of

Chesterfield County

Chesterfield, Virginia 23832

J. Mercer White, Jr., Esquire County Attorney for

Kcnrico County

P. 0. Box 27032

Richmond, Virginia

M. Ralph Page, Esquire

420 North First Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J. Segar Gravatt, Esquire

105 East Elm Street

Blackstone, Virginia

Edward S. Hirschler, Esquire

Everett G. Allen, Jr., Esquire

Massey Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Hon. Andrew P. Miller

Attorney General of Virginia

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Norman J. Chachkin, Esquire

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

William G. Broaddus, Esquire

D. Patrick Lacy, Jr., Esquire

Assistant Attorneys General

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

L. Paul Byrne, Esquire

701 East Franklin Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

4

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this tenth day of

April, 1971, I mailed a copy of

the foregoing Plaintiffs' Opposition to Stay of District Court Order

of April 5, 1971

via United States mail, first class, postage pre-paid to each of

the following counsel herein:

Walter E. Rogers, Esq.

510 United Virginia Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia 23219

John S. Battle, Jr., Esq.1400 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Conrad B. Mattox, Jr.

City Attorney 402 City Hall

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Hon. Andrew P. Miller

Attorney General of Virginia

Supreme Court Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

R. D. Mcllwaine, III, Esq.

P. O. Box 705

Petersburg, Virginia 23803

Oliver D. Rudy

Commonwealth Attorney of

Chesterfield County

Chesterfield, Virginia 23832

L. Paul Byrne, Esq.

7th and Franklin Office Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Edw. S. Hirschler, Esq.

E. G. Allen, Jr., Esq,

2nd Floor, Massey Building

4th and Main Streets

Richmond, Virginia 23219

George B. Little, Esq.

1510 Ross Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Edward Lawler, Esq.

615 Mutual Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Frederick T. Gray, Esq.

510 United Va, Bank Bldg.

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J. Segar Cravatt, Esq.

105 East Elm Street

Blackstone, Virginia

J. Mercer White, Jr.

County Attorney for Henrico County

P. O. Box 27032

Richmond, Virginia