Robertson v Wegmann Brief of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1978

53 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Robertson v Wegmann Brief of Amicus Curiae, 1978. 84abfda4-c29a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/14a8dbd9-b27e-48cd-b424-c07f5d6c28ab/robertson-v-wegmann-brief-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

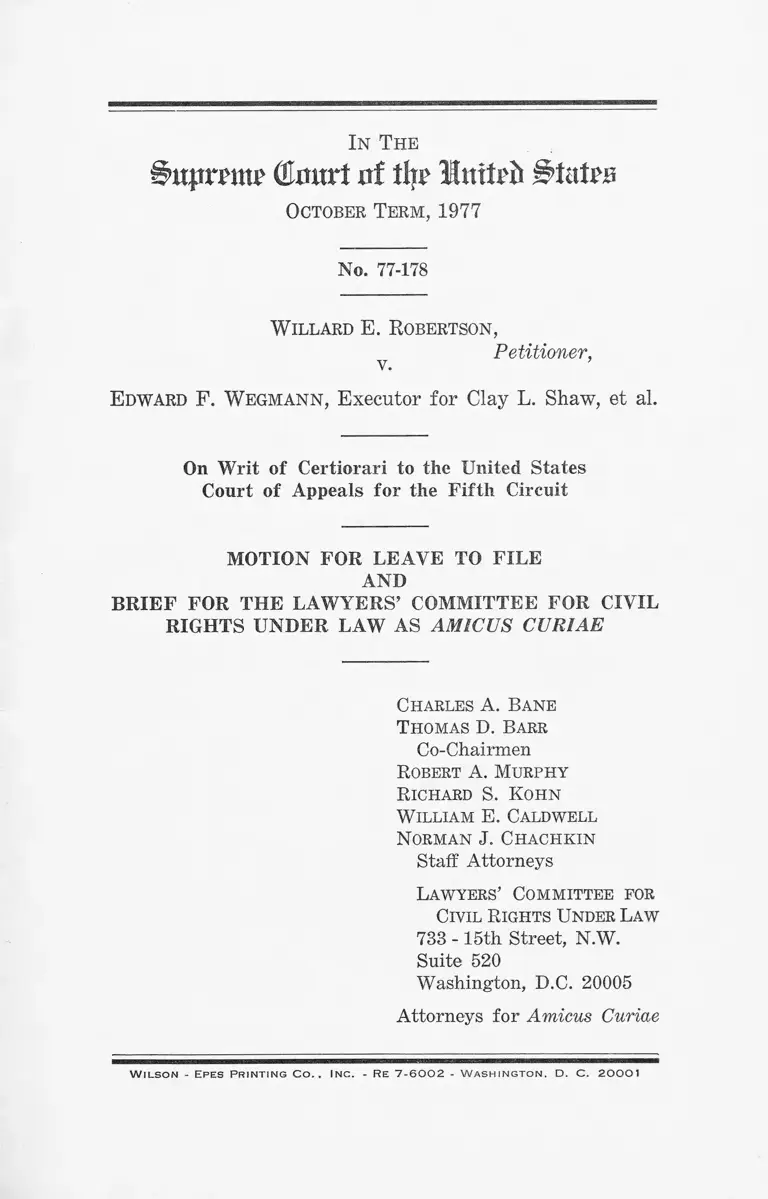

In T he

Bupmu? (tart nt tin' lutteft §1atrn

October Term , 1977

No. 77-178

W illard E. R obertson,

Petitioner, v. ’

E dward F. W egm ann , Executor for Clay L. Shaw, et al.

On Writ o f Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE

AND

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

Charles A . Ban e

T h o m as D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

R obert A. M u rph y

R ichard S. K o h n

W illiam E . Caldw ell

N orm an J. Ch a c h k in

Staff Attorneys

La w ye rs ’ Co m m ittee for

Civil R ights U nder L a w

733 - 15th Street, N W .

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W ilson - Epes Printing Co.. Inc. - Re 7-6002 - Washington, d . C. 20001

In T he

l&upmt? (ta rt m % United States

October Term , 1977

No. 77-178

W illard E. Robertson,

Petitioner, v. ’

E dward F. W egm ann , Executor for Clay L. Shaw, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

proposed amicus curiae herein, respectfully seeks leave

of this Court to file the attached brief in order to assist

the Court in resolving an important issue of survival of

actions brought under federal civil rights statutes. In

the attached brief, amicus discusses the varied authority

of federal courts to look beyond state law provisions in

order to achieve the ends of federal policy in suits to

enforce federal rights, in cases involving both civil rights

and other subject matter. The instant case presents the

sort of issue which arises frequently in civil rights litiga

tion, including particularly actions for damages suffered

by reason of police or other official misconduct, and this

Court’s ruling on the survival question presented here

will have an important bearing on the disposition of such

actions. Amicus does not believe that the generic nature

of the questions presented in this case will be adequately

addressed by the parties, because in the papers filed with

the Court to date, they have discussed only the narrow

problem created by Clay Shaw’s death, and because

neither party is represented by counsel who frequently

litigate civil rights actions, to the best of amicus’

knowledge.

The interest of amicus in this case grows out of its

longstanding concern with the problem of devising reme

dies that will secure the effective enforcement of federal

civil rights laws, and is more fully described infra pp. 1-3.

Amicus has sought consent of the parties to the filing

of this brief, without success.

WHEREFORE, the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law respectfully moves that its brief be

filed in this case.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles A . Ban e

T h om as D. Barr

Co-Chairmen

Robert A. M u rph y

R ichard S. K oh n

W illiam E. Caldw ell

N orm an J. C h a c h k in

Staff Attorneys

L aw ye rs ’ Com m ittee for

Civil R ights U nder L a w

733 - 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

INDEX

Page

Table of Authorities _____________ __ _________ _______ iii

Interest of Amicus Curiae............ ............................ —~ 1

Statement .... ...................... ................—.................... ......... 4

Summary of Argument........ ............................................ 5

ARGUMENT—

Introduction _____ ______ ______ ___________________ 6

I. Federal Courts Are Not Round To Apply Only

State Law To The Innumerable Procedural And

Remedial Questions Which Arise In The Course

Of Litigation But Which Are Not Specifically

Addressed By Federal Statute________________ 8

A. In civil rights actions, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 is an

explicit Congressional authorization to em

ploy that combination of federal and state

statutory and “ common law” which best

serves to fulfill the remedial and deterrent

purposes of federal civil rights statutes____ 8

B. The same flexibility characterizes the practice

of the courts in all federal question litigation

with respect to application of state law; this

flexibility is entirely consistent with the Rules

of Decision Act and inheres in the constitu

tional grant of jurisdiction___ _____________ 17

II. In This Case Louisiana’s Limited Survival Of

Actions Statute Was Properly Not Applied Be

cause To Do So Would Conflict With The Re

medial And Deterrent Purposes Of The Federal

Civil Rights A cts________ ____________________ 23

A. Factors bearing upon the choice of la w _____ 24

INDEX— Continued

Page

B. The remedial-deterrent purposes of the Civil

Rights A cts__________ ___—----------------------- 29

C. Abatement of this action by reason of Clay

Shaw’s untimely death would be inconsistent

with Congress’ purpose in creating the § 1983

cause of action ___________________________- 34

Conclusion __________________________________________ 41

ii

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Adickes v. S. H. Kress <& Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970).. 30

Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) _____________________________________8n, 30-31

Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. V. Wilderness Soc’y, 421

U.S. 240 (1975)______ 24n

Ambrose V. Wheatley, 321 F. Supp. 1220 (D. Del.

1971) ....... „ ______ ________________________ __ - 16

Atkins V. Schmutz Mfg. Co., 435 F. 2d 527 (4th

Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 932 (1 9 71 )-. 20n

Baker V. F&F Inv., 420 F. 2d 1191 (7th C ir.), cert.

denied, 400 U.S. 821 (1970)________ 12n

Bank of America V. Parnell, 352 U.S. 29 (1956)—. 26

Barry v. Edmunds, 116 U.S. 550 (1886) ------ -------- 32

Basista V. Weir, 340 F. 2d 71 (3d Cir. 1965)_____ 16

Bivens V. Six Unknown Named Agents, 403 U.S.

338 (1971)........... .......... ............... .....- ............... ... 19

Board of County Comm’rs V. United States, 308

U.S. 343 (1939)____ 26

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F. 2d 401 (5th Cir. 1961) — 14, 35n

Brown V. City of Meridian, 356 F. 2d 602 (5th

Cir. 1966) ______________ 9n

Burnett V. New York Cent. R.R. Co., 380 U.S. 424

(1965) ________________________ _______ —........ 29n

Charles Dotvd Box Co. V. Courtney, 368 U.S. 502

(1961) ______________________ 27n

Chevron Oil Co. V. Huson, 404 U.S. 97 (1971)____ 24

Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363

(1943) ________________ l9.21n,25-26

Complaint of Cambria S.S. Co., 505 F. 2d 517 (6th

Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 420 U.S. 975 (1975)— 39

Cope V. Anderson, 331 U.S. 460 (1947)--------------- 28

Damico V. California, 389 U.S. 416 (1967)------------ 29-30

Davis V. Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572 (N.D. 111.

1955) _________ _____________ - _______________ 16,36

Dean V. Shirer, 547 F. 2d 227 (4th Cir. 1976)____ 15,16n

District of Columbia V. Carter, 409 U.S. 418

(1973) ....... ....... ................ - __ -.................... .......... 31n

IV

D’Oench Duhme & Co. V. FDIC, 315 U.S. 447

(1942) _ ............................................................... .... 26

Evain V. Conlisk, 364 F. Supp. 1188 (N.D. 111.

1973), ail’d without opinion, 498 F. 2d 1403 (7th

Cir. 1974) ........ 15n

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1880) --------- ----- 31n

Farmers Educ. Coop. Union V. WDAY, 360 U.S.

525 (1959) ................ 19

Francis V. Southern Pac. Co., 333 U.S. 445 (1948).. 27

Gore V. Turner, 563 F. 2d 159 (5th Cir. 1977)____ 29, 33n

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971)----- ----- 9

Hall V. Wooten, 506 F. 2d 564 (6th Cir. 1974)____ 15

Hodge V. Seiler, 558 F. 2d 284 (5th Cir. 1977)____ 28

Holmberg V. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392 (1946)------- 27

Holmes V. Silver Cross Hosp. of Joliet, 340 F. Supp.

125 (N.D. 111. 1972)............................................. 15n

Hughes V. Washington, 389 U.S. 290 (1967)-------- 24n

Hutto V. Finney, No. 76-1660 (pending)---- ---------- 2n

Illinois V. City of Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91 (1972)—. 19

IngramW. Steven Robert Corp., 547 F. 2d 1260 (5th

Cir. 1977) ________________ ___ ___________ ____ 15n, 28

International Union V. Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383

U.S. 696 (1966)_____________ -__ _________22n, 27n, 28

Jackson County V. United States, 308 U.S. 343

(1939) .........................................................-.......... 19

J.I. Case Co. V. Borak, 377 U.S. 426 (1964) ______ 19, 28n

Johnson V. Greer, 477 F. 2d 101 (5th Cir. 1973)....... 16

Jones V. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) _. 8n

Jones V. Hildebrant, 432 U.S. 183 (1977)______2n, 3 ,15n,

30n,36

Lee V. Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F. 2d 290

(5th Cir. 1970)------------------- ----- ---------------------- 16

Lefton V. City of Hattiesburg, 333 F. 2d 380 (5th

Cir. 1964).................................................................. . 9n

Local 17U V. Lucas Flour Co., 369 U.S. 95 (1962) ....19, 27n

Luker V. Nelson, 341 F. Supp. 113 (N.D. 111. 1972).. 19-20

Lynch V. Household Fin. Corp., 405 U.S. 538

' (1972) ........................... .......... ...................... -......... 23

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

V

Marbury V. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cr.) 137 (1803) „18n, 30n

McAllister V. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 357 U.S.

221 (1958).... ...................................-..............—19, 26n, 28

McNeese V. Board of Educ., 373 U.S. 668 (1963).... 30

Miller V. Smith, 431 F. Supp. 821 (N.D. Tex.

1977) ...................... ................. .................................29, 35n

Mitchum V. Foster, 408 U.S. 225 (1972).7n, 8n, 23, 30, 31n

Mizell V. North Broward Hosp. Dist., 427 F. 2d

468 (5th Cir. 1970)________ _____ _____________ 35n

Monell V. Department of Social Services, No. 75-

1914 (pending)..................... ...................... -........ —- 2n

Monroe V. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) ____ ____ 16n, 23, 30

Moor V. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973).- 8

Moragne V. States Marine Lines, 398 U.S. 375

(1970) ________ ____________ __________________ 3, 39

National Metropolitan Bank V. United States, 323

U.S. 454 (1945) .............. ......................................... 19

Neuman V. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ..................................................................— 8n

Northcross V. Board of Educ., 412 U.S. 427 (1973).. 8n

Pfizer, Inc. V. Government of India, 46 U.S.L.W.

4073 (January 11, 1978) ---- ---------------------- 33

Pierson V. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) _____________ 15n

Pollard V. United States, 384 F. Supp. 304 (M.D.

Ala. 1974)..................... .....................................— -28, 35n

Preiser V. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 475 (1973) ----------- 29

Pritchard V. Smith, 289 F. 2d 153 (8th Cir. 1961)- 14-15,

35n

Reconstruction Fin. Corp. V. Beaver County, 328

U.S. 204 (1946) ......_ _______________________ 26

Rizzo V. Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976) _____________ 2n

Robinson V. Campbell, 16 U.S. (3 Wheat.) 212

(1818) — ..................-_______ _______________18, 19, 27n

Rodriguez V. Taylor, No. 76-2609 (3d Cir., Decem

ber 27, 1977)................................ -.........-................. 34n

Runyon V. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976) ------------- lOn

Samuels V. Mackell, 401 U.S. 66 (1971)--------------- 4n, 38

Sanders V. Russell, 401 F. 2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968).. 9n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

VI

Sea-Land Services V. Gaudet, 414 U.S. 573 (1974)._ 39

Shaw V. Garrison, 391 F. Supp. 1353 (E.D. La.

1975), aff’d 545 F. 2d 980 (5th Cir. 1977), cert,

granted, 46 U.S.L.W. 3373 (December 5, 1977).. 5

Shaw V. Garrison, 328 F. Supp. 390 (E.D. La.

1971), aff’d 467 F. 2d 113 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 409 U.S. 1024 (1972)................... ................. . 4

Shaw V. Garrison, 293 F. Supp. 937 (E.D. La.),

aff’d 393 U.S. 220 (1968 )_____________ _______ 4, 38

Sola Elec. Co. V. Jefferson Elec. Co., 317 U.S. 173

(1942) ____ _______ _____ _____________________ 19,27

Spence V. Staras, 507 F. 2d 554 (7th Cir. 1974)....... 15

Steffel V. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974)------------- 23

Sullivan V. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229

(1969) _____________ __ - ......7, 8n, 10,12,16, 28, 30, 35

Textile Workers Union V. Lincoln Mills, 363 U.S.

448 (1957) ................... ....................... - ...... ...19, 25n, 27n

Tunstall V. Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210 (1944)____ ___ ______ 19

United States V. Carson, 372 F. 2d 429 (6th Cir.

1967) _____ ____ - ................................ ......- ........ 20

United States ex rel. Washington V. Chester County

Police Dep’t, 300 F. Supp. 1279 (E.D. Pa. 1969).. 16-17

United States V. Little Lake Misere Land Co., 412

U.S. 580 (1973) ____ ______________ 20, 21, 22, 2 In, 25n

United States V. May ton, 335 F. 2d 153 (5th Cir.

1964) ____ ______ _____________________________ 9n

United States V. 93.970 Acres of Land, 360 U.S.

328 (1959) ________________ __________ ______- 25n

United States V. Price, 383 U.S. 787 (1966) ______ 9

United States V. Standard Oil Co., 332 U.S. 301

(1947) ________ _____ -___ ___ ________________ 24n, 25

United States V. Yazell, 382 U.S. 341 (1966) ..........20, 25n

Wallis V. Pan American Petroleum Corp., 384

U.S. 63 (1966) ___________ ___________________ 27

Worth V. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490 (1975) _________ 2n

Young V. ITT, 438 F. 2d 757 (3d Cir. 1971)_______ 16

Younger V. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971) .................. . 4, 38

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Constitution and Statutes Page

U.S. Const., art. Ill, § 2, cl. 1 ________ ______________ 17

18U.S.C. §242 __________ lOn

28 U.S.C. § 1652 ____________ ...____ ______________ 18n

28 U.S.C. § 2283_____ _____ _____________________ 8n, 30

29 U.S.C. § 185__________________________________ 27n

42 U.S.C. § 1981..................................... ______________ lOn, 17

42 U.S.C. §§ 1981-1986_____________ _____________ 7

42 U.S.C. § 1982 _______ _________________ 8n, lOn, 28, 29

42 U.S.C. § 1983____________ ___ __ _______ _____ passim

42 U.S.C. § 1986 __________ ___ ____________________ 35

42 U.S.C. § 1988........ ................... ................................passim

Rev. Stat. § 722 lOn

Act of May 8,1792, 1 Stat. 275 _____ ________ __ _____ 18n

Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act ______________ 20

Civil Rights Act of 1964___________________________ 8n

Civil Rights Act of 1866,14 Stat. 2 7 __ _________ 9,10,12

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fee Awards Act of 1976,

P.L. 94-559 (October 19, 1976), 90 Stat. 2641_„„. 9n

Clayton A c t_____________________________ 33

Death on the High Seas Act _________ _______ _____ 39

Emergency School Aid Act of 1972 ______________ 8n

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 140___ lOn

Federal Employers Liability A c t________________ 39

Judiciary Act of 1789__ ________ __ _____________ 6,18

Ku Klux Act of 1871 _____ ____________________6, 23, 29

Longshoremen’s and Harbor Workers’ Compensa

tion Act ___ 39

Rules of Decision A c t ........ .......... .................6,18, 19, 20, 24

Taft-Hartley A c t ....... ....... ......___................. ............... 27n

Rules

Sup. Ct. Rule, August, 1792, 2 U.S. (2 Dali.) 411-

14 ____________________________ ___—~___ _____ 18n

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. (1866) ...10-11,13,14

W. Blackstone, Commentaries________________ 18n

V ll

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

V ll l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Other' Authorities Page

Monaghan, The Supreme Court, 1974 Term— Fore

word: Constitutional Common Law, 89 Harv.

L. R ev. 1 (1975) ........... ..... .......-......._...................- 19

Niles, Civil Actions for Damages Under the Fed

eral Civil Rights Statutes, 45 T ex . L. R ev. 1015

(1967) .................................................... -................. 31n

Redish & Phillips, Erie and the Rules of Decision

Act: In Search of the Appropriate Dilemma, 91

H arv. L. R ev . 356 (1977)........................................ 20n

In T he

li’Kj.imtu* (Emnl itf tip? lint!?!* BluVes

October Term , 1977

No. 77-178

W illard E. Robertson,

Petitioner,v.

E dward F. W egm ann , Executor for Clay L. Shaw, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL

RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys through

out the country in the national effort to assure civil

rights to all Americans. The Committee’s membership

today includes two former Attorneys General, ten past

Presidents of the American Bar Association, two former

Solicitors General, a number of law school deans, and

many of the nation’s leading lawyers. Through its na

tional office in Washington, D.C., and its offices in Jack-

son, Mississippi, and eight other cities, the Lawyers’ Com

mittee over the past fourteen years has enlisted the serv

ices of over a thousand members of the private bar in

addressing the legal problems of minorities and the poor

in voting, education, employment, housing, municipal serv

ices, the administration of justice, and law enforcement.

2

The Lawyers’ Committee has been actively involved in

a wide variety of litigation on behalf of minority-race

persons seeking redress for unconstitutional conduct com

mitted under color of state law; the vast preponderance

of this litigation has been brought in federal courts pur

suant to the provisions of 42 U.S.C. § 1983.1 The Com

mittee’s experience is that broad principles of relief are

essential to the fulfillment of that statute’s goals: prin

cipally, the compensation of the victims of unconstitu

tional action and the deterrence of like misconduct in the

future.

Because the federal Civil Rights Acts do not furnish

standards for the disposition of every matter arising in

the course of the litigation which they authorize, his

torically the federal courts have engaged in interstitial

lawmaking through incorporation of state law or creation

of federal common law. This practice is given explicit

statutory sanction by 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

The flexibility which § 1988 affords federal trial courts

to shape their procedures and remedies in accord with the

underlying policy of the Civil Rights Acts is indispensable

to effective redress for constitutional wrongs. Amicus is

therefore concerned by the Petitioner’s suggestions that

§ 1988 should be given a cramped interpretation, restrict

ing federal courts to state law alone on matters of pro

cedure and remedy arising in civil rights suits.

Of particular importance to amicus is the availability

of an effective federal remedy for police misconduct and

brutality. This interest led the Lawyers’ Committee

(along with other amici) last Term to file a brief in

;l The Committee has also filed amicus briefs with this Court in

a number of § 1983 cases, including Huttto V. Finney, No. 76-1660

(pending); Monell v. Department of Social Services, No. 75-1914

(pending) ; Jones V. Hildebrant, 432 U.S. 183 (1977) ; Rizzo v.

Goode, 423 U.S. 362 (1976) ; and Worth v. Seldin, 422 U.S. 490

(1975).

3

Jones v. Hildebrant, 432 U.S. 183 (1977). There, the

mother of a youth shot and killed by a Denver policeman

sought to recover damages for his death in a state court

action based, alternatively, upon 42 U.S.C. § 1983. The

Colorado Supreme Court held that the state’s “ wrongful

death” statute would be “borrowed” in a suit on the fed

eral claim, but that as a result, any damage recovery

would be limited by Colorado’s “net pecuniary loss” rule

applied in state wrongful death suits. We argued that

the state’s limitation on damages was ill-suited to afford

complete justice as § 1983 required, and therefore it should

not be incorporated in any “borrowing” of the state’s

wrongful death statute under 42 U.S.C. § 1988. Alter

natively, we urged this Court to sustain a federal com

mon law of wrongful death in civil rights actions as it

had done in admiralty, in Moragne v. States Marine

Lines, 398 U.S. 375 (1970).2

The instant case involves a state “ survival” statute,

which can also play a major role in lawsuits to recover

damages for police misconduct which maims or causes

death. Acceptance of the argument which Petitioner ad

vances would have consequences extending far beyond the

facts of this case, which we discuss below. We file in this

matter, therefore, to emphasize the critical importance

of sustaining the federal courts’ authority to reject state

law, when to apply it would undermine substantial fed

eral concerns—whatever the merits of any particular

exercise of that authority. We are also satisfied that the

rejection of Louisiana’s survival statute in this case was

proper.

12 After oral argument, this Court dismissed the writ of certiorari

as improvidently granted, as it had become clear that the Petitioner

in Jones was not seeking damages for the injury to and killing of

her son, but rather damages for deprivation of her claimed parental

interest in the life o f her son. 432 U.S. at 189.

4

STATEMENT

The facts relevant to the issues presented to this Court

are few, and are not in any dispute. In March of 1967,

the original plaintiff in this action Clay Shaw was in

dicted by an Orleans Parish, Louisiana grand jury on

a charge of conspiracy to murder President John F. Ken

nedy. The indictment followed Shaw’s arrest and the

public announcement of the charge by then Parish Dis

trict Attorney Jim Garrison, one of the defendants in

this action, and a preliminary hearing in state court.

Shaw v. Garrison, 293 F.Supp. 937, 939 (E.D. La.),

aff’d 393 U.S. 220 (1968); id., 328 F. Supp. 390, 394

(E.D. La. 1971). In 1968 Shaw sued Garrison before a

three-judge federal district court, seeking declaratory and

injunctive relief to restrain his further prosecution on

the conspiracy charge. The Court granted Garrison’s

motion for summary judgment, holding that no grounds

for federal court interference with the pending state

prosecution had been alleged. Shaw v. Garrison, 293 F.

Supp. 937 (E.D. La.), aff’d 393 U.S. 220 (1968).3

On March 1, 1969, a state court jury unanimously

found Shaw not guilty of the conspiracy charge. Shaw

v. Garrison, supra, 328 F. Supp. at 399. The following

day, Garrison filed an information charging Shaw with

perjury. Id. at 399-400. Before that charge could be

tried, in 1971 Shaw sought and obtained a federal court

injunction against his further prosecution, based on an

explicit finding of bad faith by Garrison sufficient to bring

the case within the exceptional circumstances rule of

Younger v. Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971). Shaw v. Garri

son, 328 F. Supp. 390 (E.D. La. 1971), aff’d 467 F.2d

113 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1024 (1972).

3 The district court’s opinion declining- to entertain the 1968 action

correctly anticipated much of this Court’s reasoning in Younger v.

Harris, 401 U.S. 37 (1971) and Samuels V. Mackell, 401 U.S. 66

(1971).

5

In the meantime, Shaw had in February 1970 filed this

civil rights damages action against Garrison and other

co-defendants (including Petitioner Robertson) with

whom Garrison was alleged to have conspired to harass

Shaw and deprive him of his constitutional rights. Shaw

v. Garrison, 391 F. Supp. 1353, 1355 (E.D. La. 1975),

aff’d 545 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, granted, 46

U.S.L.W. 3373 (December 5, 1977). Before the action

was tried, Shaw died on August 15, 1974, “ survived by

neither spouse, children, parents, nor siblings.” Id., 391

F. Supp. at 1356. Several of the defendants, including

Petitioner, thereupon moved to dismiss the action on the

ground that under Louisiana law it abated with Shaw’s

death. Shaw’s executor sought to be substituted as plain

tiff.4 After receiving briefs, the trial court agreed that

the action would abate under Louisiana law, but held that

42 U.S.C. § 1988 authorized “ the creation of a federal

common law of survival in civil rights actions in favor

of the personal representative of the deceased” in order

to give effect to “ the policies underlying the civil rights

laws and [this] Court’s treatment of survival of actions

in analogous contexts.” Id., 391 F. Supp. at 1368. The

Fifth Circuit agreed, and its judgment affirming the trial

court’s denial of the motions to dismiss is the subject of

this Court’s present review.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

A. Where necessary to give effect to the congressional

purpose underlying the Reconstruction Civil Rights Acts,

42 U.S.C. § 1988 authorizes federal courts in civil rights

actions to look beyond the provisions of state laws gov

erning matters of remedy and procedure. The plain

4 Shaw left a valid will naming a friend as residuary legatee of

his estate. Petition for Certiorari, at 4.

6

language of the statute, the debates of the 39th Con

gress which enacted it, and the very justification for

affording a federal remedy for deprivations of constitu

tional rights, all support this power for the federal courts.

B. Even in circumstances where state law is generally

held to govern, this Court has consistently interpreted the

Rules of Decision Act (Section 34 of the first Judiciary

Act) and Section 1988 to allow the federal courts to look

beyond state law provisions when their application would

produce results inconsistent with the purposes of fed

eral law.

II

The lower court’s exercise of the authority in this

case is fully proper. Under either § 1988 or the inherent

choice-of-laws responsibility of federal courts, there is no

per se incorporation of state law. Rather, its applica

bility depends upon its appropriateness to give effect to

the underlying federal policies. Here, the deliberate ac

tion of the Reconstruction Congresses creating a federal

court cause of action in order to deter deprivations of

constitutional rights by those acting under color of state

law requires that Louisiana’s limitation on survival of

state-created claims be displaced.

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This case presents a relatively narrow issue: whether

the courts below correctly exercised their authority under

42 U.S.C. § 1988 by holding, as a matter of interstitial

federal common law, that this damage action under the

Ku Klux Act of 18715 survived after the plaintiff’s

15 The relevant portion of the Act is now codified at 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983.

7

death, in favor of his residuary legatee or executor. How

ever, the arguments made in Petitioner’s brief implicate

broader questions of federal judicial power under the

Reconstruction era civil rights statutes.10 It would be

inappropriate to consider these questions solely in the

factual context presented by the matter before the Court;

yet Petitioner’s analysis neither reserves nor fully treats

them. In the discussion which follows, we accordingly

show first, that federal courts are authorized, in civil

rights cases brought pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981-86, to

look beyond the law of the state in which the trial

court sits to discover applicable rules of law governing-

procedural and remedial questions not explicitly ad

dressed by these Reconstruction era statutes; and second,

that such authority was correctly exercised in the case

and on the issue presently before the Court. Even if

the Court were to disagree with our second point, there

fore, it should not announce any general limitation on the

power of federal trial judges to effectuate federal policy,

in appropriate cases, by selecting non-state procedural

or remedial legal doctrines which best fulfill the federal

purpose which gives rise to the cause of action. Cf.

Sullivan V. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969).

10 These questions recur frequently in federal civil rights litigation

but generally have not troubled the lower federal courts. Yet they

are central to the effectiveness o f the federal remedy for constitu

tional deprivations which is established by the Reconstruction era

civil rights statutes. See generally Mitchum v. Foster, 408 U.S. 225

(1972).

8

I

Federal Courts Are Not Bound To Apply Only State

Law To The Innumerable Procedural And Remedial

Questions Which Arise In The Course Of Litigation

But Which Are Not Specifically Addressed By Federal

Statute.

A. In civil rights actions, 42 U.S.C. § 1988 is an explicit

congressional authorization to employ that combina

tion o f federal and state statutory and “common law”

which best serves to fulfill the remedial and deter

rent purposes o f federal civil rights statutes.

As this Court has noted, federal civil rights statutes—

particularly those dating from the Reconstruction era—

lack all of the specific provisions necessary to delimit

precisely the contours of the remedial causes of action

which they have been held to create.

[I]nevitably existing federal law will not cover every

issue that may arise in the context of a federal civil

rights action.

Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693, 702 (1973).7

As a result, in such suits the courts themselves must

7 See Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 414 n.14 (1968)

(noting silence of 42 U.S.C. § 1982 with respect to recovery of dam

ages) ; Sullivan V. Little Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229, 238-40 (1969)

(creating damage remedy under § 1982 to provide “an effective

equitable remedy” ) ; Mitchum v. Foster, 407 U.S. 225 (1972) (hold

ing that 42 U.S.C. § 1983 is “ expressly authorized” exception to> 28

U.S.C. § 2283 despite absence o f specific statutory language on

point) ; cf. Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 413-21

(1975) (holding that plaintiffs in cases under Title VII of the 1964

Civil Rights Act who prove employment discrimination should or

dinarily receive back pay, although statute merely authorizes such

remedy) ; Northcross V. Board of Educ., 412 U.S. 427 (1973) (suc

cessful plaintiff in action to desegregate schools should “ ordinarily”

recover attorneys’ fees under provision of Emergency School Aid

Act of 1972 authorizing award in discretion of cou rt); Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968) (same; Title II of

Civil Rights Act of 1964).

9

provide answers to various procedural and remedial ques

tions as they arise. In so doing, the courts are guided

by the national policy expressed in the federal civil rights

laws, which are to be “ accord [ed] a sweep as broad as

[their] language.” Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88,

97 (1971), quoting from United States v. Price, 383 U.S.

787, 801 (1966). Federal courts are quick to adjust

their procedures to the task.8

42 U.S.C. § 1988 (originally Section 3 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1866, 14 Stat. 27) requires no less.0 It

instructs that in civil rights matters, whenever federal

statutes are “ deficient in the provisions necessary to fur

nish suitable remedies,” the courts shall apply the “ com

mon law” as modified by statutes of the forum state if it

is not “ inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the * 9

« E.g., Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) (admis

sion of out-of-state attorneys) ; Brown v. City of Meridian, 856

F.2d 602 (5th Cir. 1966) (acceptance of joint removal petitions) ;

Lefton V. City of Hattiesburg, 333 F.2d 380 (5th Cir. 1964) (same) ;

United States v. Mayton, 335 F.2d 153 (5th Cir. 1964) (registration

o f voters).

9 42 U.S.C. § 1988 provided as follows prior to its 1976 amendment

by the Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act, P.L. 94-559 (Oc

tober 19, 1976), 90 Stat. 2641, in respects not here relevant:

The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters conferred on the

district courts by the provisions o f this chapter and Title 18,

for the protection of all persons in the United States in their

civil rights, and for their vindication, shall be exercised and

enforced in conformity with the laws of the United States, so

far as such laws are suitable to carry the same into effect; but

in all cases where they are not adapted to the object, or are

deficient in the provisions necessary to furnish suitable reme

dies and punish offenses against law, the common law, as modi

fied and changed by the constitution and statutes of the State

wherein the court having jurisdiction of such civil or criminal

cause is held, so far as the same is not inconsistent with the

Constitution and laws of the United States, shall be extended to

and govern the said courts in the trial and disposition of the

cause, and, if it is of a criminal nature, in the infliction of

punishment on the party found guilty.

10

United States.” § 1988 has been construed by this Court

to permit resort to either federal or state rules on dam

ages, “whichever better serves the policies expressed in

the federal statutes,” Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park,

supra, 396 U.S. at 240. Thus, the plain language of the

statute and its construction by this Court support the

power questioned in this case, to look beyond Louisiana

law on survival of actions so as to fulfill the purposes

of the civil rights acts.10

There is nothing startling about this proposition when

§ 3 of the 1866 A ct11 is considered in the context of the

practices of many state courts at the time of its passage.

The debates in the 39th Congress contain repeated ref

erences—by both supporters and opponents of the bill—

to state statutes limiting or abrogating the testimonial

capacity of Black witnesses, or denying Blacks the right

to bring suit. See Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess.

478-79, 602, 1121-22, 1151-52, 1156-57, 1159, 1260, 1265,

1270, 1293, 1759, 1777, 1783, 1809, 1832-33, Appendix

10 Petitioner apparently concedes the point; the only distinction of

Sullivan urged in his brief is that in Sullivan there was an extant

“ federal rule” to choose, while Petitioner contends there was no

“ federal rule” applicable to this case until one was created by the

courts below. Pet. Br. at 18-19.

11 § 1 of the 1866 Act, declaring the rights of citizens, is now

codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982. § 2 of the Act made it a crim

inal offense to deprive persons of those rights under color of state

law, and is currently codified at 18 U.S.C. § 242. § 3 of the Act, in

its original version, provided for federal jurisdiction “ exclusively

of the courts of the several states” as to criminal cases brought

pursuant to § 2, and also provided for removal of cases from state

to federal court in specified circumstances; it then contained the

language now codified at 42 U.S.C. § 1988 and quoted in note 9

supra..

The entire 1866 Act was re-enacted, following passage of the

Fourteenth Amendment, by § 18 of the Enforcement Act of May 31,

1870, 16 Stat. 140. In 1874 the revisers (see generally Runyon v.

McCrary, 427 U.S. 160, 168 n.8 (1976)) made § 1988 applicable to

all civil rights legislation. Rev. Stat. § 722.

11

pp. 157-58, 182 (1866). This Act was clearly understood

to invalidate such laws and to authorize criminal prose

cution of state judges and other officials who sought to

enforce them:

I will not therefore attempt a full discussion of [the

Act] now, but content myself with briefly presenting

some of the grounds upon which I will again perform

the proudest act of my political life in voting to make

this bill the law of the land.

It is scarcely less to the people of this country than

Magna Charta was to the people of England.

It declares who are citizens.

It does not affect any political right, as that of suf

frage, the right to sit on juries, hold office, &c. This

it leaves to the States, to be determined by each for

itself. It does not confer any civil right, but so far

as there is any power in the States to limit, enlarge,

or declare civil rights, all these are left to the States.

But it does provide that as to certain enumerated

civil rights every citizen “shall have the same right

in every State and Territory.” That is whatever of

certain civil rights may be enjoyed by any shall be

shared by all citizens in each State, and in the Terri

tories, and these are:

1. To make and enforce contracts.

2. To sue, to be sued, and to be parties.

3. To give evidence.

4. To inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey

real and personal property.

5. To be entitled to full and equal benefit of all laws

and proceedings for the security of person and prop

erty.

Id. at 1832 (Rep. Lawrence).

12

In these circumstances, it would be little short of as

tounding if Congress were to have intended by § 3 of the

Act to require that the federal courts adopt, and be

bound by, the very discriminatory state practices which

the legislation was intended to invalidate. Rather, the

conditional phrase, “so far as the same is not inconsistent

with the Constitution and laws of the United States,” was

designed to guard against this result. The language was

purposefully inserted into § 3 of the Act to authorize the

creation of such federal law as might be necessary to

carry out the broad purposes of the statute, as this

Court recognized in Sullivan.1*

Petitioner apparently would reduce this language, and

Congress’ understanding of it, to a nullity, for his brief

says:

The referral to and adoption of state law under the

second part of Section 3 was never the subject of any

debate whatever, [footnote omitted] since obviously

it was deemed to constitute a recognition of the law

of the forum state as controlling. What a furor

would have resulted if any member of Congress had

even suggested that a federal court could refuse to

apply the pertinent state law under Section 3, and

instead formulate a federal common law of survivor

ship of actions under the Civil Rights Act!

Pet, Br. at 12-13. Not only is this interpretation of the

statute inconsistent with the very thesis of the 1866

Civil Right Act, as demonstrated above, but it is also

factually inaccurate. The “ federal common law” aspects

of § 3 may not have been the focus of debate, but they

did not go unnoticed by opponents of the bill. When it

1)2 It is precisely in this sense, we submit, that § 1988 “was de

signed to supplement but not supplant the Rules of Decision Act.”

Baker V. F&F Inv., 420 F.2d 1191, 1196 (7th Cir.), cert, denied,

400 U.S. 821 (1970). Even under that statute, as we show infra

pp. 17-22, federal courts are not bound to apply state law which

is inconsistent with federal interests.

came before the House of Representatives, Representative

Kerr attacked the provision bitterly:

I might go on and in this manner illustrate the prac

tical working of this extraordinary measure. But I

have said enough to indicate the inherent viciousness

of the bill. It takes a long and fearful step toward

the complete obliteration of State authority and the

reserved and original rights of the States. . . . Then

the things attempted to be prohibited are in them

selves so extraordinary and anomalous, so unlike any

thing ever attempted before by the Federal Govern

ment, that the authors of this bill feared, very prop

erly too, that the system of laws heretofore adminis

tered in the Federal courts might fail to supply any

precedent to guide the courts in the enforcement of

the strange provisions of this bill, and not to be

thwarted by this difficulty, they confer upon the

courts the power of judicial legislation, the power to

make such other laws as they may think necessary.

Such is the practical effect of the last clause of the

third section, which reads as follows:

. . . [text of statute omitted]

That is to say, the Federal courts may, in such cases,

make such rules and apply such law as they please,

and call it common law.

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1271 (1866) (empha

sis in original). Indeed, this was one of the grounds

upon which President Andrew Johnson vetoed the mea

sure, although his action was subsequently overridden by

the Congress.

It is clear that in States which deny to persons whose

rights are secured by the first section of the bill any

one of those rights, all criminal and civil cases affect

ing them, will, by the provisions of the third section,

come under the exclusive cognizance of the Federal

tribunals. It follows that if, in any State which de

nies to a colored person any one of all those rights,

13

14

that person should commit a crime against the laws

of the State, murder, arson, rape, or any other crime,

all protection and punishment through the courts of

the State are taken away, and he can only be tried

and punished in the Federal courts. How is the crim

inal to be tried? If the offense is provided for and

punished by Federal law, that law, and not the State

law, is to govern.

It is only when the offense does not happen to be

within the purview of the Federal law that the Fed

eral courts are to try and punish him under any

other law. Then resort is to be had to “ the common

law, as modified and changed” by State legislation,

“ so far as the same is not inconsistent with the Con

stitution and laws of the United States.” So that

over this vast domain of criminal jurisprudence, pro

vided by each State for the protection of its own citi

zens, and for the punishment of all persons who vio

late its criminal laws, Federal law, wherever it can

be made to apply, displaces State law.

Veto Message of President Andrew Johnson, printed in

id. at 1680 (1866).

Notwithstanding these protestations, the 1866 Act

became law, in part for the purposes of avoiding re

liance on state courts to enforce federal rights. See, e.g.,

id. at 602 (Sen. Lane).

Unquestionably, as Petitioner observes, § 1988 directs

federal courts in civil rights actions to examine state law

provisions upon an initial determination that federal

statutes, or rules promulgated pursuant to federal stat

ute, do not address procedural or remedial issues arising

in those actions. And where state law is adequate to

vindicate fully the constitutional rights which are the

subject of the litigation, § 1988 clearly authorizes its

use. But this is not the limit of § 1988; nor does the fact

that state survival statutes were found adequate in

Brazier v. Cherry, 293 F.2d 401 (5th Cir. 1961); Pritch

15

ard v. Smith, 289 F.2d 153 (8th Cir. 1961); Hall v.

Wooten, 506 F.2d 564 (6th Cir. 1974) ; Dean v. Shiver,

547 F.2d 227 (4th Cir. 1976); and Spence V. Staras, 507

F.2d 554 (7th Cir. 1974) indicate any conflict between

those decisions and the ruling below in this case, as

Petitioner suggests. Petition for Certiorari, at 6-10; see

Pet. Br. 16-17.13 In numerous cases, federal courts have

13 Petitioner has cited no case in which state survival laws were

applied to defeat a federal civil rights action. The description in

Pet. Br. 15 n .ll is simply in error. Holmes V. Silver Cross Hasp, of

Joliet, 340 F. Supp. 125 (N.D. 111. 1972) was a suit against a court-

appointed conservator, a hospital, and doctors on its staff, alleging

infringement of plaintiff’s freedom of religion by administration of

a blood transfusion without his consent. The court concluded that

the survival of the action under Illinois law depended on whether

the defendants were acting “ under color of state law.” 340 F.

Supp. at 129. It dismissed the court-appointed conservator from

the lawsuit on the ground that he shared in the Illinois courts’

judicial immunity in a § 1983 lawsuit (see Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S.

547 (1967)). 340 F. Supp. at 131. All other defendants were

found to have acted under color of state law, and the court con

cluded that by applying Illinois survival statutes the action could

be maintained by decedent’s administrator. Id. at 134, 135-36.

In Evain V. Conlisk, 364 F. Supp. 1188 (N.D. 111. 1973), aff’d

without opinion 498 F.2d 1403 (7th Cir. 1974), the decedent’s

daughter brought a § 1983 action to recover damages for the al

leged wrongful killing o f her father by Chicago police officers.

The court held that the complaint stated no cause of action on behalf

of the plaintiff individually, for the same reasons given by this

Court in dismissing the writ of certiorari last Term in Jones v.

Hildebrant, supra. (The court did not hold, as Petitioner suggests,

that there was such a claim but that it did not survive under

Illinois law.) Further, the court recognized that Illinois’ “wrongful

death” statute permitted “ survival” of an action on behalf of de

cedent’s estate for damages. However, it held that plaintiff could

not maintain the suit because the appropriate statute of limitations

period had long passed before litigation was commenced. Id. at 1191.

See Ingram V. Steven Robert Corp., 547 F.2d 1260, 1262 (5th Cir.

1977) for an instructive comparison of policies applied under § 1988

with respect to statutes of limitation and survival or wrongful death

statutes.

It is true that in Holmes and some of the cases cited in text,

there is dictum to the effect that state law is controlling on ques

tions of wrongful death and survival. However, in all o f these eases,

16

exercised the power granted by § 1988 to utilize pro

cedural and remedial rules other than those embodied in

state law.

For example, in Davis v. Johnson, 138 F. Supp. 572,

575 (N.D. 111. 1955), the court found in § 1988 a direc

tive to extend “ suitable remedies,” and—relying in part

on maritime precedents—construed § 1983 to permit an

action by the administratrix of a decedent whose death

resulted from the alleged constitutional violation. In

Basista v. Weir, 340 F.2d 71, 86-87 (3d Cir. 1965), the

court held that punitive damages could be awarded in a

§ 1983 action under federal common law principles, al

though unavailable in a state court action. Similarly,

following this Court’s ruling in Sullivan, supra, the court

in Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp., 429 F.2d 290, 294

(5th Cir. 1970) held that punitive damages could be

awarded in a § 1982 cause of action without examining

state law on the question. See also, Johnson v. Greer,

477 F.2d 101, 106 (5th Cir. 1973) (referring to “ the

prevailing view [of tort law on proximate cause] in this

country” to determine proper federal rule in § 1983

case) ; Young v. ITT, 438 F.2d 757, 760 (3d Cir. 1971)

(damages available in § 1981 employment discrimination

suit); Ambrose v. Wheatley, 321 F. Supp. 1220, 1221 n.l

(D. Del. 1971) (punitive damages); United States ex rel.

Washington v. Chester County Police Dep’t, 300 F. Supp.

either state law was found adequate to permit federal civil rights

actions to be pursued, or some other ground for dismissal was

present. The courts have recognized that the breadth o f interests

protected by § 1983 extend beyond narrow state law tort and con

tract categories, and require generous interpretation of state sur

vival statutes. E.g., Dean v. Shirer, supra, 547 F.2d at 229-30. Cf.

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167, 196 (1961) (Harlan, J., concurring).

In many cases, including those cited in the following paragraph in

text, courts have freely ventured beyond state law to give effect

to the underlying policies of the civil rights acts. There is little

support in the lower court holdings for Petitioner’s confined reading

of § 1988.

17

1279, 1282 (E.D. Pa. 1969) (§ 1981 damage action for

police brutality; alternative holding).

The sum of the existing jurisprudence is that § 1988

requires no slavish adherence to provisions of state law

but permits its rejection, and the fashioning or applica

tion of interstitial federal common law, in order to pro

vide complete justice under the Civil Rights Acts.

B. The same flexibility characterizes the practice o f the

courts in all federal question litigation with respect

to application o f state law; this flexibility is entirely

consistent with the Rules o f Decision Act and inheres

in the constitutional grant o f jurisdiction.

Even without § 1988, and its explicit conditional lan

guage, state law would serve as a reference point in fed

eral question litigation on matters not controlled by

federal rule or statute; however, its use would not be

obligatory but would depend on the circumstances and the

effect on federal interests. This relationship between

state and federal law follows logically from the limited

constitutional grant of jurisdiction to the Courts of the

United States, the uniquely federal linkage of states and

nation, and the function of state law as a source of rules

governing primary conduct.

The Constitution provides for the judicial Power of the

United States, extending, inter alia, to “ all Cases, in Law

and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of

the United States, and Treaties made------ ” U.S. Co n s t .,

art. Ill, § 2, cl. 1. Inherent in this grant of judicial au

thority to the national government is the power to deter

mine the principles of law applicable to cases upon which

the judicial Power acts. Thus, in the absence of statute,

federal courts would have been obliged to exercise the

interpretive authority of a court of common law to deter

mine questions arising in the course of federal case liti

18

gation.14 This power was limited by § 34 of the Judiciary

Act of 1789, 1 Stat. 92 (the Rules of Decision Act), which

provided that

. . . the laws of the several states, except where the

constitution, treaties, or statutes of the United States

shall otherwise require or provide, shall be regarded

as rules of decision in trials at common law in the

courts of the United States in cases where they

apply.1®

However, the Rules of Decision Act has never been inter

preted to mandate unswerving application of state law

to every matter not explicitly determined by federal stat

ute or rule.16

In Robinson v. Campbell, 16 U.S. (3 Wheat.) 212

(1818), an ejectment action arising under an interstate

compact, this Court held that the Rules of Decision Act

had to be construed in accordance with other provisions

of federal law. Since Congress had provided for federal

court proceedings in equity in the first Judiciary Act,

the Court refused to apply state law, inconsistent with

1,4 Similarly, in the absence o f statute, the Courts of the United

States would possess inherent judicial authority to regulate their

own procedures. For example, although the Judiciary Act o f 1789

did not grant explicit rulemaking authority to this Court ( com

pare §2, Act of May 8, 1792, 1 Stat. 275, 276, authorizing this

Court to prescribe forms and modes o f proceedings to district and

circuit courts), in August of 1792 the Court announced that it

“ consider[ed] the practice of the courts of King’s Bench and

Chancery in England, as affording outlines for the practice of this

court; and that, [it] will, from time to time, make such alterations

therein, as circumstances may render necessary.” 2 U.S. (2 Dali.)

411-14 (1792).

15 The Rules of Decision Act is now codified at 28 U.S.C. § 1652.

1,6 In Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. (1 Cr.) 137, 162-63 (1803),

Chief Justice Marshall relied upon Blackstone’s COMMENTARIES

to imply the existence of a judicial remedy from a United States

statute considered to grant a legal right, but silent on the subject

of remedy.

19

equity jurisdiction, pursuant to the Rules of Decision

Act. Id. at 222-23 (alternative holding). Since then, in

innumerable cases involving federal questions, this Court

has determined that the substantive principles of federal

law require, in exception to the Rules of Decision Act, the

development and application of “ interstitial” federal com

mon law. E.g., Illinois v. City of Milwaukee, 406 U.S. 91

(1972) ; Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents, 403 U.S.

338 (1971); J.I. Case Co. v. Borak, 377 U.S. 426 (1964) ;

Local 17L v. Lucas Flour Co., 369 U.S. 95 (1962) ;

Farmers Educ. Coop. Union v. WDAY, 360 U.S. 525

(1959) ; McAllister v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., 357 U.S.

221 (1958) ; Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills, 363

U.S. 448 (1957) ; National Metropolitan Bank v. United

States, 323 U.S. 454 (1945) ; Tunstall v. Brotherhood of

Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen, 323 U.S. 210 (1944);

Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, 318 U.S. 363

(1943) ; Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec. Co., 317 U.S.

173 (1942) ; Jackson County v. United States, 308 U.S.

343 (1939) ; see generally Monaghan, The Supreme Court,

197U Term—Foreword: Constitutional Common Law, 89

Harv. L. Rev. 1 (1975).

The standards of § 1988 as well as the Rules of De

cision Act were perceptively summarized in this language

from a § 1983 decision:

. . . our Court of Appeals has concluded that § 1988

was designed to supplement but not supplant the

Rules of Decision Act and is applicable only when

federal substantive law is not suitably adapted or

sufficient to provide an appropriate remedy and the

states have remedial provisions of law which, if ap

plied, will help achieve the goals desired by the Civil

Rights Act. Baker v. F&F Investment Company, 420

F.2d 1191, 1193-1197 (7th Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

Universal Builders, Inc. v. Clark, 400 U.S. 821, 91

S. Ct. 40, 27 L. Ed. 2d 49 (1970). After reviewing

the legislative history behind the Rules of Decision

2 0

Act and § 1988, the Court there concluded that the

Rules of Decision Act requires the application of

state law in federal question suits where Congress

has not specifically legislated on the particular aspect

of law covered by the state law and where no uniform

federal common law is felt by the courts to be re

quired, and if application of the state law does not

deny or conflict with the very right to relief created

by the federal law.

Luker v. Nelson, 341 F. Supp. 113, 116 (N.D. 111. 1972)

(emphasis in original). Thus, it is the nature of federal

interests affected in any instance which determines the ex

tent to which state law shall apply, not any mechanical ap

plication of the Rules of Decision Act. Compare United-

States v. Yazell, 382 U.S. 341 (1966) (Texas law of cov

erture applies to Small Business Administration loan

agreements) ivith United States v. Carson, 372 F.2d 429

(8th Cir. 1967) (Tennessee limitation on damages would

not be applied to government suit for conversion of prop

erty secured by mortgage executed in connection with

Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act loan).

Just a few Terms ago, this Court reemphasized the

choice-of-law authority allowed courts in federal question

litigation 17 by the Rules of Decision Act. In United States

v. Little Lake Misere Land Co., 412 U.S. 580 (1973),

the government brought an action to quiet title to parcels

of land in Louisiana. The issue decided by this Court was

whether Louisiana law applied to determine the validity

or extinguishment of prior reservations of mineral rights

in the act of sale and judgment of condemnation by which

17 Existence of the same authority under the Rules of Decision

Act in diversity cases has been suggested. See Atkins v. Schmutz

Mfg. Co., 435 F.2d 527 (4th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S. 932

(1971) and discussion of the case in Redish and Phillips, Erie and

the Rules of Decision A ct: In Search of the Appropriate Dilemma,

91 H arv . L. Rev. 356, 378-80, 391-92 n.189 (1977). That question

is neither presented nor implicated in the case before the Court,

21

the government acquired the land. State law has always

had a singular importance with respect to real property

matters, and the Court of Appeals had accepted applica

tion of the Louisiana rule, finding that it was nondis-

criminatory with respect to the United States as a

party to a land transaction. Id. at 584-85. In his opinion

reversing that judgment, the Chief Justice observed:

. . . The Court of Appeals [’] . . . opinion seems to

say that state law governs this land acquisition be

cause, at bottom, it is an “ ordinary” “ local” land

transaction to which the United States happens to be

a party. The suggestion is that this Court’s decision

in Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U.S. 64 (1938),

compels application of state law here because the

Rules of Decisions Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1652, requires

application of state law in the absence of an explicit

congressional command to the contrary. We disagree.

The federal jurisdictional grant over suits brought by

the United States is not in itself a mandate for apply

ing federal law in all circumstances. This principle

follows from Erie itself, where, although the federal

courts had jurisdiction over diversity cases, we held

that the federal courts did not possess the power to

develop a concomitant body of general federal law.

. . . It is true, too, that “ [t]he great body of law in

this country which controls acquisition, transmission,

and transfer of property, and defines the rights of

its owners in relation to the state or to private par

ties, is found in the statutes and decisions of the

state.” Davies Warehouse Co. v. Boivles, 321 U.S.

144, 155 (1944). Even when federal general law

was in its heyday, an exception was carved out for

local laws of real property. . . .

Despite this arguable basis for its reasoning the

Court of Appeals in the instant case seems not to

have recognized that this land acquisition, like that

in Letter Minerals, is one arising from and bearing

heavily upon a federal regulatory program. Here,

22

the choice-of law task is a federal task for federal

courts, as defined by Clearfield Trust Co. V. United

States, 318 U.S. 363 (1943). Since Erie, and as a

corollary of that decision, we have consistently acted

on the assumption that dealings which may be “ ordi

nary” or “ local” as between private citizens raise

serious questions of national sovereignty when they

arise in the context of a specific constitutional or

statutory provision; particularly is this so when

transactions undertaken by the Federal Government

are involved, as in this case. In such cases, the Con

stitution or Acts of Congress “ require” otherwise

than that state law govern of its own force.

There will often be no specific federal legislation gov

erning a particular transaction to which the United

States is a party; here, for example, no provision of

the Migratory Bird Conservation Act guides us to

choose state or federal law in interpreting federal

land acquisition agreements under the Act. But si

lence on that score in federal legislation is no reason

for limiting the reach of federal law, as the Court

of Appeals thought in Letter Minerals. To the con

trary, the inevitable incompleteness presented by all

legislation means that interstitial federal lawmaking

is a basic responsibility of the federal courts. “At

the very least, effective Constitutionalism requires

recognition of power in the federal courts to declare,

as a matter of common law or ‘judicial legislation,’

rules which may be necessary to fill in interstitially

or otherwise effectuate the statutory patterns enacted

in the large by Congress. . . .”

Id. at 590-93 (footnotes omitted).18

18 “ [S]tate law is applied [under the Rules of Decision Act] only

because it supplements and fulfills federal policy, and the ultimate

question is what federal policy requires.” International Union v.

Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383 U.S. 696, 709 (1966) (White, J., dis

senting) .

23

That it is federal rights protected, and federal reme

dies afforded, by 42 U.S.C. § 1983, is beyond dispute. See,

e.g., Steffelw. Thompson, 415 U.S. 452 (1974) ; Lynch v.

Household Fin. Corp., 405 U.S. 538 (1972) ; Mitchum V.

Foster, supra; Monroe v. Pape, supra, 365 U.S. at 196

(Harlan, J., concurring). The federal interests thus es

tablished by the Civil Rights Acts would, even in the ab

sence of § 1988, therefore, have to be taken into account

in deciding whether to apply state law in Civil Rights

Acts suits. Accordingly there can be no doubt of the

power of federal courts to disregard state law in such

suits if that course is deemed necessary to “effectuate the

statutory pattern enacted in the large by Congress,” and

we turn to a consideration of the circumstances in which

the exercise of the power is appropriate.

II

In This Case Louisiana’s Limited Survival Of Actions

Statute Was Properly Not Applied Because To Do So

Would Conflict With The Remedial And Deterrent Pur

poses Of The Federal Civil Rights Acts.

We have shown above that courts entertaining federal

civil rights actions are not invariably required to follow

the provisions of state law on matters as to which the fed

eral Civil Rights Acts are silent. Accordingly, we contend,

the judgment below must be sustained unless this Court

determines that the courts below used the wrong stand

ards to decide whether Louisiana’s survival statute should

be applied to this case. We proceed, therefore, to articulate

first, the considerations relevant to the choice-of-law de

cision; second, the policies and purposes which underlie

the federal Civil Rights Acts in general, and the Ku Klux

Act of 1871 (42 U.S.C. § 1983) in particular; and third,

the reasons why we believe the correct result was reached

in this case.

24

A. Factors bearing upon the choice o f law.

It is worth reiterating, as a preliminary matter, that

the authority to apply or reject state law is presented

under either § 1988 or the Rules of Decision Act only on

an interstitial basis, where federal statutory law is in

complete and silent about the source of decisional rules

to fill any gaps. Neither we nor this case invite the Court

to sanction, as it has consistently refused to do, a general

common law. Where federal statutes direct uncondi

tionally— as neither § 1988 nor the Rules of Decision Act

do— that state law is to be incorporated as federal law,

that is the end of the matter; there is no room nor need

for “ interstitial” federal common law. Chevron Oil Co.

v. Huson, 404 U.S. 97 (1971).19

Analysis of this Court’s choice-of-law rulings reveals

two general categories of facts and circumstances which

are taken into account.20 The first may be called the

“nature of the national interest.” This encompasses such

matters as: the presence of the United States, or an

agency of the United States, as a party;21 whether the

substantive questions in the lawsuit involve the validity or

consequences of activities of the United States or its

agencies;22 whether the decision of the substantive ques

^ Cf. Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. V. Wilderness Soc’y, 421 U.S.

240 (1975) (Congressional enactment of various specific authoriza

tions for the award o f attorneys’ fees by federal courts, against

background o f general statutory limitation of power to award fees,

precluded judicial adoption o f broad “ private attorney general”

theory).

2,0 “ . . . whether state law is to be applied . . . ‘necessarily is de

pendent upon a variety of considerations always relevant to the

nature of the specific governmental interests and to the effects upon

them of applying state laws.’ ” United States v. Little Lake Misere

Land Co., supra, 412 U.S. at 595, quoting from United States V.

Standard Oil Co., 332 U.S. 301, 309-10 (1947).

21 E.g., Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, supra.

22 E.g., Hughes V. Washington, 389 U.S. 290 (1967).

25

tions will likely have a wide effect upon the conduct of

a national regulatory or assistance program; 23 whether

the litigation itself has been explicitly or implicitly sanc

tioned by the Congress as a means of effectuating national

policy,24 etc.

In general, the “ stronger” the federal interest, the

less likely it is that state laws will be found to apply.

This does not mean, however, that state law is barred

from consideration. The presence of an important fed

eral interest is usually stated to be sufficient to require

that “ federal law” be applied to the substance of the case,

but even then, as this Court has said, “ [i]n our choice

of the applicable federal rule we have occasionally selected

state law.” Clearfield Trust Co. v. United States, supra,

318 U.S. at 367. In some cases this is justified on the

assumption “that Congress has consented to application of

state law . . . [a]nd in still others state law may fur

nish convenient solutions in no way inconsistent with

adequate protection of the federal interest.” United States

v. Standard Oil Co., 332 U.S. 301, 309 (1947).

The second set of factors relates to the impact of apply

ing state law: both its impact upon the case at hand and

upon the federal interests which are involved in and af

fected by it. Aspects of this inquiry include: the ability

of the national government to anticipate and meet state

law requirements in the normal operations of its pro

grams ; 25 the availability of alternative mechanisms to

satisfy the federal interest which are unaffected by the

state law (including their likely effectiveness and the

access of the parties to them );26 the degree to which

23 E.g., United States V. Little Lake Misere Land Co., supra, 412

U.S. at 597.

24 E.g., Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln Mills, supra.

25 E.g., United States v. Yazell, supra.

2,(5 See United States V. 93.970 Acres of Land, 360 U.S. 328 (1959).

2 6

application of state law would abort, rather than merely

alter, proceedings in the pending lawsuit,27 etc.

These variegated concerns underscore our earlier point

that the choice of law determination is far from automatic

or mechanical. Diverse results flow from rational analysis

of competing values in these cases. Distinctions are often

founded upon the intensity of the national interest and

the effect of state law upon the national policy, as the

following examples illustrate.

We consider first suits directly touching or implicating

governmental activities. In Clearfield Trust Co. v. United

States, supra, the Court concluded that the interest of

the government in a uniform national definition of its

rights and duties was so great that federal, and not state,

law would be applied to its transactions in commercial

paper. This interest was found to be much more attenu

ated in Bank of America v. Parnell, 352 U.S. 29 (1956)

(a diversity case) ; since there the Court also viewed ap

plication of state law to private transactions in commer

cial paper as having little impact upon the federal govern

ment, it rejected the Clearfield doctrine.

Similarly, in D’Oench Duhme & Co. v. FDIC, 315 U.S.

447 (1942), the Court inferred from various statutes a

protective policy toward the federal agency involved in

the case, which it held required the application of federal

and not state law. But where no need for such special

solicitude was evidenced in federal legislation (or the

Constitution or treaties), state law rules were permitted

to determine, for example, the tax liability of a national

agency in Reconstruction Fin. Corp. v. Beaver County,

328 U.S. 204 (1946) and the availability of interest on

tax payments improperly exacted from Indians, which the

United States sued to recover in Board of County

Comm’rs v. United States, 308 U.S. 343 (1939).

27 E.g., McAllister v. Magnolia Petroleum Co., supra.

27

A like pattern obtains in litigation between private

parties in which important federal interests become en

tangled. In Sola Elec. Co. v. Jefferson Elec. Co., supra (a

diversity action), this Court ruled that a state estoppel

rule could not be given effect to prevent presentation of

a defense of illegality under the Sherman Act. On the

other hand, no important federal policy issues were af

fected by the application of state law to determine the

relations of private parties under a federal mineral lease

in Wallis v. Pan American Petroleum Corp., 384 U.S. 63

(1966). Federal law was held to govern tort liability in

Francis v. Southern Pax;. Co., 333 U.S. 445 (1948) by

virtue of an implied Congressional approval of the pre-

statutory common law rule; and to prescribe available

defenses in Holmberg v. Armbrecht, 327 U.S. 392 (1946)

because the underlying claim was a federally created

equitable right held not subject to state rules of limita

tions.218

Statutes of limitations cases form a distinct body of

law, primarily because the impact of applying state limi

tations (if any) is ordinarily confined to the litigation, 28

28 Cf. Robinson v. Campbell, supra. The law applied in suits

brought pursuant to § 301 of the Taft-Hartley Act, 29 U.S.C. § 185,

also illustrates the point well. In Textile Workers Union v. Lincoln

Mills, supra, 353 U.S. at 456, this Court announced that federal law,

“which the courts must fashion from the policy of our national

labor laws,” would be the substantive law applied in suits under

§ 301 to enforce agreements to arbitrate between labor unions and

management. Charles Dowd Box Co. v. Courtney, 368 U.S. 502

(1961) allowed such suits to be brought in state, as well as federal,

courts— but in such instances, the Court held that same Term in

Local 17U V. Lucas Flour Co., 369 U.S. 95 (1962), federal law must

be applied. Yet even in this area in which federal concerns seemed

to be paramount, the Court has ruled that there is room for flexi

bility, for diverse state laws. State statutes of limitation, the Court

said in International Union v. Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383 U.S. 696,

701-03 (1966), could be applied in §301 suits because “ [l)ack of

uniformity in this area is . . . unlikely to frustrate in any important

way the achievement of any significant goal of labor policy.” Id. at

702.

28

and does not affect federal interests or ongoing federal

programs. See, e.g., Cope v. Anderson, 331 U.S. 460, 463-

64 (1947) (state limitations period would be applied to

equitable action to enforce federally created assessments

on shareholders of insolvent national bank, although com

mencement of period is question of federal law) ; Inter

national Union v. Hoosier Cardinal Corp,, supra n. 28;

but see McAllister V. Magnolia Petroleum Co., supra (state

limitation period could not be applied to unseaworthiness

claims where it was shorter than federal Jones Act period,

since federal law requires that both claims be prosecuted

in a single action).

These choice-of-law principles are applicable to suits

brought under the federal Civil Rights Acts. As we dis

cuss in the next section, these statutes create important

federal interests, recognized by this Court’s ruling in

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, supra, 396 U.S. at 239,

that “ [cjompensatory damages for deprivation of a fed

eral right are governed by federal standards, as pro

vided by Congress in 42 U.S.C. § 1988 . . . .” 29 See Hodge

v. Seiler, 558 F.2d 284, 287-88 (5th Cir. 1977) (as a

matter of federal law, at least nominal damages must be

awarded for violation of § 1982 right) ; Pollard v. Uniteo.I

States, 384 F. Supp. 304, 307 n.2 and accompanying text

(M.D. Ala. 1974) (state limitations period applies, but

in determining commencement of period, federal— not

state— rule with respect to fraudulent concealment gov

erns) ; Ingram v. Steven Robert Corp., supra, 547 F.2d

at 1262 n.2 and accompanying text (distinguishing be

tween state statutes of limitation and survival statutes 29

29 Compare J.l. Case Co. v. Borak, supra, 377 U.S. at 434: “ But

we believe that the overriding federal law applicable here would,

where the facts required, control the appropriateness of redress

despite the provisions of state corporation law, for it ‘is not un

common for federal courts to fashion federal law where federal

rights are concerned.’ Textile Workers V. Lincoln Mills . . . .”

29

based upon their im pact);30 Gore v. Turner, 563 F.2d

159, 164 (5th Cir. 1977) (in § 1982 action, court should

have awarded punitive damages based upon “ evaluation

of the nature of the conduct in question, the wisdom of

some form of pecuniary punishment, and the advisability

of a deterrent to future illegal conduct” ) ; Miller v. Smith,

431 F. Supp. 821 (N.D. Tex. 1977) (state tolling rule

would not be followed in § 1983 case if its application

would be inconsistent with purposes underlying federal

cause of action).