LDFA-13_4585.pdf

Public Court Documents

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. LDFA-13_4585.pdf, 9ffd9723-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/14d5288b-612a-4f39-a0e5-0029131f3a09/ldfa-13_4585pdf. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

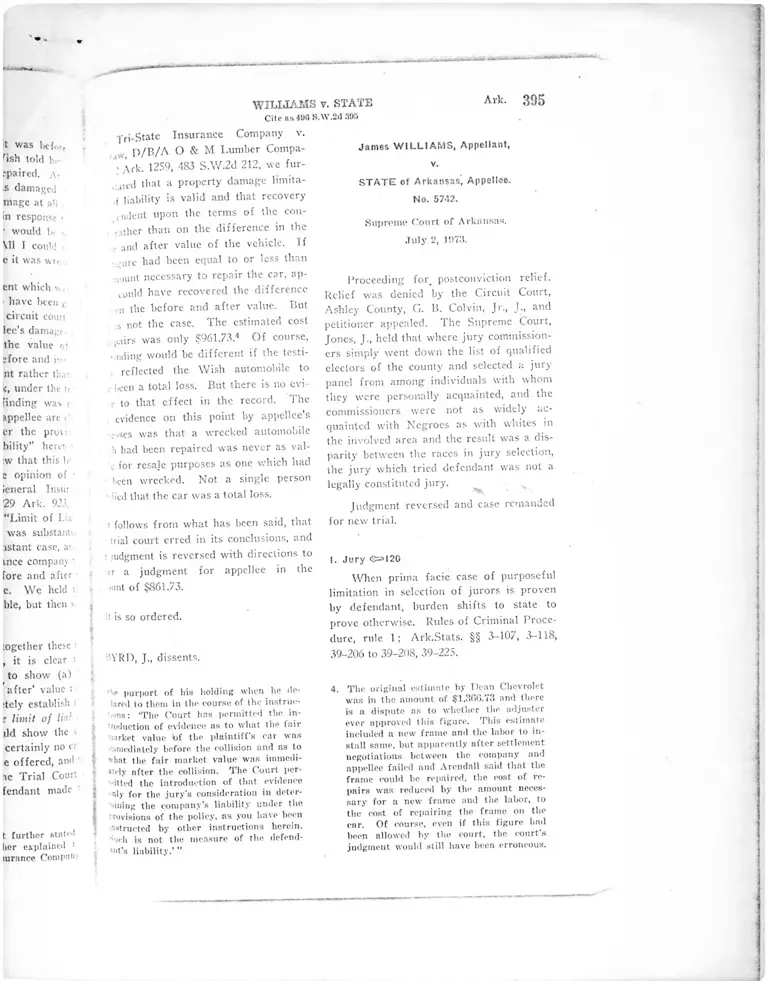

Ark. 395WILLIAMS v. STATE

Cite as 490 S.\V.2d 395

I'ri-State Insurance Company v.

D/B/A O & M Lumber Compa-

Ark. 1259, 483 S.W.2d 212, we fur-

i;lictl that a property damage limita-

,f liability is valid and that recovery

C,„jcnt upon the terms of the con-

■ r.ithcr than on the difference in the

. . anc] after value of the vehicle. If

• ..'lire had been equal to or less than

•launt necessary to repair the car, ap-

conld have recovered the difference

the before and after value. But

;5 not the case. The estimated cost

pairs was only $961.73A Of course,

• aiding would be different if the testi-

re fleeted the Wish automobile to

, |,ecu a total loss. But there is no evi-

•f to that effect in the record. The

evidence on this point by appellee’s

■ vsses was that a wrecked automobile

;h had been repaired was never as val-

'c for resale purposes as one which had

: been wrecked. Not a single person

:icd that the car was a total loss.

t follows from what has been said, that

■ trial court erred in its conclusions, and

• judgment is reversed with directions to

vr a judgment for appellee in the

•miit of $861.73.

It is so ordered.

i'.VRD, J., dissents.

the purport of Ills holding when he de-

hiroil to them in the course of the instruc-

■ ..«ns: ‘The Court has permitted the in-

'reduction of evidence as to what the fair

market value iof the plaintiff’s ear was

Mint'd lately before the collision and ns to

viiat the fair market value was immedi-

itely after the collision. The Court per

mitted the introduction of that evidence

' tily for the jury’s consideration in deter

mining the company’s liability under the

Provisions of the policy, as you have been

■nstrueted by other instructions herein.

Such is not the measure of the defend

ant's liability.’ ”

James WILLIAMS, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Arkansas', Appellee.

No. 5742.

Supreme Court of Arkansas.

July 2, KITH.

Proceeding for. postconviction relief.

Relief was denied by the Circuit Court,

Ashley County, G. B. Colvin, Jr., J., and

petitioner appealed. The Supreme Court,

Jones, J., held that where jury commission

ers simply went down the list of qualified

electors of the county and selected a jury

panel from among individuals with whom

they were personally acquainted, and the

commissioners were not as widely ac

quainted with Negroes as with whites in

the involved area and the result was a dis

parity between the races in jury selection,

the jury which tried defendant was not a

legally constituted jury.

Judgment reversed and case remanded

for new trial.

I. Jury €=>120

When prima facie case of purposeful

limitation in selection of jurors is proven

by defendant, burden shifts to state to

prove otherwise. Rules of Criminal Proce

dure, rule 1; Ark.Stats. §§ 3-107, 3-118,

39-206 to 39-208, 39-225.

4. The original estimate by Dean Chevrolet

was in the amount of $1,366.73 and there

is a dispute as to whether the adjuster

ever approved this figure. This estimate

included a new frame and the labor to in

stall same, but apparently after settlement

negotiations between the company and

appellee failed and Arendall said that the

frame could be repaired, the cost of re

pairs was reduced by the amount neces

sary for a new frame and the labor, to

the cost of repairing the frame on the

car. Of course, even if this figure had

been allowed by the court, the court's

judgment would still have been erroneous.

396 Ark. 496 SOUTH WESTERN REPORTER, 2cl SERIES

2. Ju ry <2=120

Where individuals are selected for

jury service from tax lists, or from any

source, where separate race is indicated,

and where there is large percentage of Ne

groes as compared with whites who are

presumed to have legal qualifications to

serve as jurors, prima facie case of racial

discrimination is presented when jury com

missioners select those to serve.on juries

only from among the individuals with

whom they are acquainted and such proce

dure results in small percentage of Ne

groes as compared with whites being se

lected for jury service. Ark.Stats. §§ 3-

107, 3-118, 39-206 to 39-208, 39-225. U.

S.C.A.Const Amend, 14.

3. Ju ry O l 20

Prior or systematic exclusion of Ne

groes from jury service is admissible in ev

idence in support of claim of intentional

exclusion because of race in given case.

Rules of Criminal Procedure, rule 1 ; Ark.

Stats. §§ 3-107, 3-118, 39-206 to 39-208,

39-225.

4. Jury 0=33(1)

Defendant in homicide case had no

constitutional right to have Negroes on

jury before whom he was tried and no

constitutional right to have Negroes on

panel from which jury was selected but

was entitled to be tried before legally con

stituted jury, excluding any jury from

which members of any race were excluded

simply because of their race. Ark.Stats.

§§ 3-107, 3-118, 39-206 to 39-208, 39-225;

U.S.C.A.Const. Amend. 14.

5. J u ry 0=33 (1 )

Where jury commissioners simply

went down list of qualified electors of

county and selected jury panel from among

individuals with whom they were pcrsonal-

I. Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 83 S.Ct. 822

9 Ij.kM.2d 837; Townsend v. Sain, a i-

U.S. 293, S3 S.Ct. 745, 9 Tj.Ed.2d 770 and

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1, 83

S.Ct. 1068, 10 L.Ed.2d 148. See also ar-

ly acquainted, and commissioners v.

as widely acquainted with Negro, ,

whites in the area and result was <

between races in jury selection, jut

tried defendant was not legally

jury. Ark.Stats. §§ 3—107, 3—1 IS,

39-208, 39-225; U.S.C.A.Const. Ai

Walker, Kaplan & Mays, P.A.

Rock, and Jack Greenberg, No;

Chachkin, New York City, for app<4

Ray Thornton, Atty. Gen., by :

Ginger, Deputy Atty. Gen., Little lb-

appellee.

)ONES, Justice.

James Williams wras charged wit",

degree murder committed in the pr

tion of rape. He was found gu

charged at a jury trial in the Ashley

ty Circuit Court and on December »

he was sentenced to death by electro

His conviction and sentence were at;

by this court on appeal, Williams v.

239 Ark. 1109, 396 S.W.2d 834, and 1

ecution date was set by the Govcr:

July 22, 1966. Execution was stayed

order of this court entered on Ju

1966, to permit Williams to seek po

viction relief under Criminal Fro:

Rule No. 1 promulgated and adopt,

cause of the tremendous increase in

corpus petitions being filed in the sb>'

federal courts by convicted felons / '

authorized and permitted under 1

States Supreme Court decisions.1

Following the Rule No. 1 hearing

Ashley County Circuit Court on Nov

9, 1967, the petition was denied by f"

tier filed on May 25, 1971, and W

now appeals from the trial court ord

nying relief on his petition to vaca

former judgment of conviction. In

tide “Accommodating State Criin

Procedure and Federal Post Con\i‘

Review” by Daniel J. Meador in Amcr

Bar Association Journal, October,

vol. 50, p. 1928.

:e s

immissioners w<~

with Negroes :

id result was d

y selection, jure

not legally cor.

5-107, 3-118, 3'i

C.A.Const. Am.

& Mays, P.A., I

reenberg, Norm

: City, for appetU

itty. Gen., by 1!

. Gen., Little Roc.

vas charged with '

nitted in the peri.

was found guilt;

ial in the Ashley 1

i on December 9,

death by electro.'

sentence were aff.

peal, Williams v. .v

s.W.2d 834, and hi

:t by the Governor

;ution was stayed 1

t entered on July

iliams to seek post .

:r 1 Criminal Procc

Igated and adoptee

.dous increase in li

ng filed in the state

invicted felons pro '

irmitted under l

irt decisions.1

tie No. 1 hearing if '

;uit Court on Novo

was denied by fit'1

25, 1971, and Will-

the trial court ordi't

5 petition to vacate

f conviction. In ’

ating State Crii"':

cdcral Post Convii'1

l J. Meador in Anr'U'

Journal, October, 1 ‘

WILLIAMS

C ite as 49G S

eight years since Williams was

. lr|ed and convicted, his death sen-

was commuted to life imprisonment

executive clemency. The appellant now

. .,„|s that the trial court erred in deny-

•„js petition for post-conviction relief

reasons stated as fo llow s:

\u'iellant’s unrebutted evidence that

•x'r'roes were systematically excluded

or included in token numbers only

,.Kin the jury venires of Ashley County,

Arkansas established a denial of his

• mirtccnth Amendment rights.

Appellant’s trial was conducted under

i,lCh intimidating conditions and after

„.fh adverse, hostile and prejudicial pub

licity as to deny him a fundamentally

i ,ir hearing, and thus his rights under

:u. due process clause of the Fourteenth

\mendment were denied him.”

j be appellant’s second assignment was

, vented, argued and considered on lus

4 appeal and we do not reach it here

.uise we find we must reverse his convic-

n under the first assignment.

j 11 The constitutional prohibition

mist exclusion of members of any race

:a jury service because of race has nev-

' been questioned in Arkansas. Williams

State, 229 Ark. 1022, 322 S.W.2d 86;

,:sey v. State, 219 Ark. 101, 240 S.W.2d

; Green v. Stale, 222 Ark. 222, 258 S.

-M 56; Maxwell v. State, 217 Ark. 691,

’ S.\V.2d 982; Bailey v. State, 227 Ark.

■i. 302 SAV.2d 796. In Williams and

<sey we pointed out that the burden of

awing facts which permit an inference

i purposeful limitation for jury service

•'cause of race is on the defendant. It

ly follows that when a prime facie case

1 Purposeful limitation is proven by the

tendant, the bttrden then shifts to the

to prove otherwise. The state offered

’ evidence whatever in the case at bar, so

question before us is whether the ap-

'•int made out a prima facie case of pur-

efill exclusion of Negroes because of

r race from the jury panel in this case.

v. STATE Ark- 397

\V.2d 395

[2] There can be no question that this

court, as well as the trial courts of this

state, is bound by the decisions of the

United Slates Supreme Court concerning

rights and prohibitions under the provi

sions of the United States Constitution

and, there is no question that the United

States Supreme Court has spoken clearly,

and more than once, on the question of

racial discrimination in the selection of

juries in criminal cases. We shall not

attempt to cite all the Supreme Court de

cisions bearing on the subject nor shall

we quote extensively from any of them,

but the substance of these decisions is

simply this: Where individuals are se

lected for jury service from tax lists, or

from any source, where separate race is in

dicated, and where there is a large percent

age of Negroes as compared with whites

who are presumed to have the legal quali

fications to serve as jurors; a prima facie

case of racial discrimination is presented

when jury commissioners select those to

serve on juries only from among the indi

viduals with whom they arc acquainted and

such procedure results in a small percent

age of Negroes as compared with whites

being selected for jury service. Such pri

ma facie evidence may, of course, be rebut

ted by evidence that the comparatively

small percentage of Negroes selected was

not because of their race. The burden of

presenting'such evidence, however, rests on

the state. -

Wc need only mention in some detail

two United States Supreme Court decisions

from which the above rule is extracted.

They are Cassell v. Texas, 339 U.S. 282, 70

S.Ct. 629, 94 L.Ed. 839; Whitus v. Geor

gia, 385 U.S. 545, 87 S.Ct. 643, 17 L.Ed.2d

599. These decisions have been followed

by the Federal Courts of Appeals in many

cases but we deem it unnecessary to com

ment on more than two or three of them

including the case of Bailey v. Henslee, 8

Cir., 287 F.2d 936, which arose from this

state.

The background for the decision in Cas

sell v. Texas, supra, arose in two prior cas-

398 Ark. 496 SOUTH WESTERN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

es, Hill v. Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 62 S.Ct.-

1159, 86 L.Ed. 1559 and Akins v. Texas,

325 U.S. 398, 65 S.Ct. 1276, 89 L.Ed. 1692.

In Hill no Negro had ever been selected

for grand jury service in Dallas County,

Texas, and the jury comissioners testified

that they had summoned, for service on the

grand jury which returned the indictment,

members of the white race with 'whom they

were acquainted and whom they knew to

be qualified to serve. They said that they

considered Negroes for selection but did

not personally know a qualified Negro they

thought would make a good grand juror.

The Supreme Court held that the petitioner

had made a prima facie case of racial dis

crimination in the selection of jurors and

after referring to Pierre v. Louisiana, 306

U.S. 354, 59 S.Ct. 536, 83 L.Ed. 757, said:

“We thought, as we think here, that had

there been evidence obtainable to contra

dict the inference to be drawn from this

testimony, the State would not have re

frained from introducing it, and that the

evidence which was introduced suffi

ciently showed that there were colored

citizens of the county qualified and

available for service on the grand jury.

The Hill case was decided on June 1,

1942, and on June 4, 1945, the United

States Supreme Court handed down the

opinion in Akins v. Texas, supra, wherein

the Texas State Court, in attempting to

comply with the decision in Hill, selected

one Negro on a 16 men grand jury panel

from which 12 were chosen as a grand

jury. In upholding the jury selection in

Akins, the Supreme Court said:

“Purposeful discrimination is not sus

tained by a showing that on a single

grand jury the number of members of

one race is less than that race’s propor

tion of the eligible individuals. .

Defendants under our criminal statutes

are not entitled to demand representa

tives of their racial inheritance upon ju

ries before whom they are tried. But

such defendants arc entitled to require

that those who are trusted with jury

selection shall not pursue a com

conduct which results in discrimi:

‘in the selection of jurors on

grounds.’ Hill v. Texas, supra, ■

316 U.S., 62 S.Ct. 1159. Our din.

that indictments be quashed \\Tie

groes, although numerous in the u

nity, were excluded from grand ju.

have been based on the theory thru

continual exclusion indicated discr;.

tion and not on the theory that :

groups must be recognized. Nor;

Alabama, supra, [294 U.S. 587, 55

579, 79 L.Ed. 1074]; Hill v. Tex a*

pra; Smith v. Texas, supra, [311

128, 6r S.Ct. 164, 85 L.Ed. 84], Tin :

fact of inequality in the number sc!

does not in itself show discriminatio:

purpose to discrimination mm:

present which may be proven by st

atic exclusion of eligible jurymen <

prescribed race or by unequal applies

of the law to such an extent as to

intentional discrimination. Cf. Snov.

v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1, 8, 64 S.Ct. K

L.Ed. 497.”

The opinion in Cassell v. Texas, St'

was rendered on April 24, 1950. In

case an all white grand jury panel

been selected and the Negro populate :

Dallas County was approximately 1:

There were 21 grand juries during tie

riod between the Hill decision and the

sell indictment, and of the 252 name-

the panels, 17, or 6.7%, were Negro,

payment of a poll tax was a qualifier

for jury service and 6.5% of the poll

payers were Negro. It was determini'

the court that as a matter of proport

percentages, a prima facie showing ot

cial discrimination had not been six

But in Cassell, the petitioner also coin

ed that subsequent to the decision in *

the grand jury commissioners, for 21 •

secutive lists, had consistently limited

groes selected for grand jury service t1

more than one on each grand jury, or

theory that such limitation was perm

under Akins provided the limitation r’

be approximately proportional to the

selection shall not pursue a course

conduct which results in discriinin.i:

‘in the selection of jurors on ra.

grounds.’ Hill v. Texas, supra, 4 0 ;

316 U.S., 62 S.Ct. 1159. Our dirccr

that indictments he quashed when ‘

groes, although numerous in the conn,

nity, were excluded from grand jury ;

have been based on the theory that t!

continual exclusion indicated discrin;-,:

tion and not on the theory that r,.,

groups must be recognized. Norris .

Alabama, supra, [294 U.S. 587, 55 S.i •

579, 79 L.Ed. 1074]; Hill v. Texas, ...

pra\ Smith v. Texas, supra, [311 V

128, 61 S.Ct. 164, 85 L.Ed. 84], The me:

fact of inequality in the number select

does not in itself show discrimination,

purpose to discrimination must 1

present which may be proven by sysU;

atic exclusion of eligible jurymen of t:

prescribed race or by unequal applicant

of the law to such an extent as to sho.

■ intentional discrimination. Cf. Snowdt

v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1, 8, 64 S.Ct. 397, :•

L.Ed. 497.”

The opinion in Cassell v. Texas, supra

■vas rendered on April 24, 1950. In that

:ase an all white grand jury panel ha..

>een selected and the Negro population i

Dallas County was approximately 15.5'

There were 21 grand juries during the pc

"iod between the Hill decision and the Car

'ell indictment, and of the 252 names or

he panels, 17, or 6.7%, were Negro. The

>ayment of a poll tax was a quali ficati.

dr jury service and 6.5% of the poll t.v-

>ayers were Negro. It was determined L

he court that as a matter of proportion

lercentages, a prima facie showing of n

:ial discrimination had not been show:

lut in Cassell, the petitioner also contend

d that subsequent to the decision in Hi-

he grand jury commissioners, for 21 con

ecutive lists, had consistently limited Nc

;roes selected for grand jury service to m

lore than one on each grand jury', on tin

heory that such limitation was permissil

indcr Akins provided the limitation shoo'

e approximately proportional to the nun

EPORTER, 2cl SERIES WILLIAMS

Cite as 49l> S

. „f Negroes eligible for grand jury

,i,e. In Cassell the Supreme Court

. 1 :

\n accused is entitled to have charges

.gainst him considered by a jury in the

Section of which there has been neither

..elusion nor exclusion because of race.

, lur holding that there was discrimina-

,c,n in the selection of grand jurors in

.his case, however, is based on another

,<round. In explaining the fact that no

N'egroes appeared on this grand-jury list,

(he commissioners said that they knew

u.r.o available who qualified; at the

■ une time they said they chose jurymen

only from those people with whom they

were personally acquainted. It may be

assumed that in ordinary activities in

Dallas County, acquaintanceship between

the races is not on a sufficiently familiar

basis to give citizens eligible for appoint

ment as jury' commissioners an opportu

nity to know the qualifications for

^rand-jury service of many members of

another race. An individual’s qualifica

tions for grand-jury service, however,

are not hard to ascertain, and with no

evidence to the contrary, we must as

sume that a large proportion of the Ne

groes of Dallas County rrjet the statutory

requirements for jury service. When

the commissioners were appointed as ju

dicial administrative officials, it was

their duty to familiarize themselves fair

ly with the qualifications of the eligible

jurors of the county without regard to

race and color. They did not do so

here, and the result has been racial dis

crimination. We repeat the recent state

ment of Chief Justice Stone in Hill v.

Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 404, 62 S.Ct. 1159,

1161, 86 L.Ed. 1559:

'Discrimination can arise from the action

of commissioners who exclude all ne

groes whom they do not know to be

qualified and who neither know nor seek

to learn whether there are in fact any

qualified to serve. In such a case, dis

crimination necessarily results where

v. STATE Ark. 399

,\V.2d 305

there are qualified negroes available for

jury service. With the large number of

colored male residents of the county who

are literate, and in the absence of any

countervailing testimony, there is no

room for inference that there are not

among them householders of good moral

character, who can read and write, quali

fied and available for grand jury serv

ice.’

The existence of the kind of discrimina

tion described in the Hill case does not

depend upon systematic exclusion con

tinuing over a long period and practiced

by a succession of jury commissioners.

Since the issue must be whether there

has been discrimination in the selection

of the jury that has indicted petitioner,

it is enough to have direct evidence

based on the statements of the jury com

missioners in the very case. Discrimina

tion may be proved in other ways than

by evidence of long-continued unex

plained absence of Negroes from many

panels. The statements of the jury com

missioners that they chose only whom

they knew, and that they knew no eligi

ble Negroes in an area where Negroes

made up so large a proportion of the

population, prove the intentional exclu

sion that is discrimination in violation of

petitioner’s constitutional rights.” (Our

emphasis).

In Whitus v. Georgia, supra, the Negro

population was 45% of the total population

in the area involved; 27.1% of the taxpay

ers were Negro and 42% of the males over

21 years of age were Negro. After the

jury list was revised under court order in

Whitus, only three of the 33 prospective

jurors were Negro and none served on a

19 member grand jury. The jury commis

sioners in that case made up the jury ve

nires from tax records which were kept on

a segregated basis and the jury commis

sioners selected prospective jurors on the

basis of personal acquaintance. Only sev

en of the 90 persons from which the petit

jury was selected were Negro and none

were accepted on the petit jury. While the

. i

400 Ark. 496 SOUTH WESTERN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

Whitus case contained elements not present

in the case at bar, the Supreme Court in

Whitus said:

“Under such a system the opportunity

for discrimination was present and we

cannot say on this record that it was not

resorted to by the commissioners. In

deed, the disparity between the' percent

age of Negroes on the tax digest (27.-

1%) and that of the grand jury venire

(9.1%) and the petit jury venire (7.7%)

strongly points to this conclusion. Al

though the system of selection used here

had been specifically condemned by the

Court of Appeals, the State offered no

testimony as to why it was continued on

retrial. The State offered no explana

tion for the disparity between the per

centage of Negroes on the tax digest and

those on the venires, although the digest

must have included the names of large

numbers of ‘upright and intelligent’ Ne

groes as the statutory qualification re

quired. In any event the State failed to

offer any testimony indicating that the

27.1% of Negroes on the tax digest were

not fully qualified. The State, there

fore, failed to meet the burden of rebut

ting the petitioners’ prima facie case.”

(Our emphasis).

In the case of Bailey v. Henslee, 287 F.

2d 936, above referred to, the Eighth Cir

cuit Court of Appeals in granting habeas

corpus said:

“In avoiding racial discrimination in the

selection of jurors it is not enough for

the jury commissioners or any other se

lecting agency to be content with persons

of their personal acquaintance. Smith v.

State of Texas, 311 U.S. 128, 132, 61 S.

Ct. 164, 85 L.Ed. 84; Hill v. State of

Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 404, 62 S.Ct. 1159,

86 L.Ed. 1559. It is ‘their duty to fami

liarize themselves fairly with the qualifi

cations of the eligible jurors of the

county without regard to race and color.’

Cassell v. State of Texas, supra, at page

289 of 339.U.S., at page 633 of 70 S.Ct.”

In the 1940 case of Smith v. Tex:,

U.S. 128, 61 S.Ct. 164, 85 L.Ed. 84, t;,

preme Court said:

“Where jury commissioners limi:

from whom grand juries are seic.

their own personal acquaintance

crimination can arise from comm:

ers who know no negroes as \u-

from commissioners who know but <

nate them. If there has been discri:

tion, whether accomplished ingem

or ingenuously, the conviction r,

stand.”

In Vanleeward v. Rutledge, 5 Cir.

F.2d 584, the court citing from the 1

Circuit case of Scott v. Walker, 358

561, said:

“ ‘It is plain from the record here

the commissioners put on the list

those personally known to them. 1

made no especial effort to ascer

whether there were qualified Negm

the parish for jury service. In faili.

do so they violated the rule, annou

by the Supreme Court through Mr,

tice Reed in Cassell v. Texas, when

was said, “When the commissioners v

appointed as judicial administrative

cials, it was their duty to farnil. -

themselves fairly with the qualified

of the eligible jurors of the county "

out regard to race and color. The;

not do so here, and the result has

racial discrimination.” 339 U.S. 2̂

289, [70 S.Ct. 629, 633, 94 L.Ed. 85

Returning now to the facts and evkk

in the case at bar; at the time of

liams’ trial, the payment of a poll tax

necessary' under the statute (Ark.Stat

§ 3-107 [Repl.1956]) to become a qua!

elector in Arkansas. Under Ark.Stat.

§ 3-118 (Repl.1956) the tax collector

required to file with the county chr>

list containing the correct names, alp!

ically arranged (according to the p«‘

or voting townships, and according t(i

or) of all persons who have up to am

eluding October 1st of that year pa"1

<

t

I

4

<1

■' t

. .W * .

ic 1940 case of Smith v. Tex

!8, 61 S.Ct. 164, 85 L.Ed. 84,

Court said:

ere jury commissioners limit

whom grand juries are select

own personal acquaintance

:nation can arise from commi

who know no negroes as « ,,-

commissioners who know hut

them. If there has been discn:

whether accomplished ingei:

lgenuously, the conviction c.v

If

anleeward v. Rutledge, 5 Car.,

>4, the court citing from the 1

case of Scott v. Walker, 358 i

d:

is plain from the record here :

ommissioners put on the list i

personally known to them, 'P

no especial effort to ascer:

ter there were qualified Negroc

Irish for jury service. In failiu

i they violated the rule annou:.

e Supreme Court through Mr. i

leed in Cassell v. Texas, where

aid, “When the commissioners \\t

nted as judicial administrative of

it was their duty to familiar:,

elves fairly with the qualificatu

; eligible jurors of the county w '

;gard to race and color. They

□ so here, and the result has h

discrimination.” 339 U.S. 283 ■

70 S.Ct. 629, 633, 94 L.Ed. 839.]"

ning now to the facts and evide:

case at bar; at the time of V,

rial, the payment of a poll tax w

y under the statute (Ark.Stat.A1

[Repl.1956]) to become a qualii'

n Arkansas. Under Ark.Stat.A:

(Repl.1956) the tax collector v.

. to file with the county clerk

aining the correct names, alpha!

■ranged (according to the polite

g townships, and according to c

ill persons who have up to and 1

October 1st of that year paid t

TER, 2d SERIES WILLIAMS

Cite as 400 S

assessed against them respective-

;he county clerk was then required

d the list in a bound book and to

. same to the county election com-

, (.ri for use in ascertaining the qual-

lectors as they appeared at polling

(,,r casting ballots.

statutory qualifications for grand

tit jurors under Ark.Stat.Ann. §§

,, 10 39-208 (Repl.1962) required that

[E] lectors of the county

persons of good character, of

•.■roved integrity, sound judgment and

„aable information. . . . ”

circuit judge was required to select

.: jury commissioners of statutory qual-

uiotis whose duty it was to select the

I and petit juror list. Ark.Stat.Ann. §

V5 (Repl.1962) provided that any per-

- who served on the regular panel of the

: jury would be ineligible to serve on a

rijuent panel for a period of two years,

'cquently, the jury commissioners in

at bar followed the usual and cus-

>ry procedure of using the poll tax list

:Sc most convenient and accurate aid in

nmining who are “electors of the coun-

m selecting jury veniremen and also

i prior jury lists in determining who is

. edified by recent prior service.

. i j Returning now to the selection of

>uy panel in this case, it was stipulat

'd the Rule No. 1 hearing that the

-1 65 poll tax list used by the jury com

biners in selecting the jury panel for

i!,64 October term of the circuit court

Ashley County, contained the names of

6 qualified electors and that 25% of

’ were Negro. The jury panel for the

' her 1964 term of court here involved

■:sted of 60 members. Four of the

'diet's, or 6.67% of the panel, were Ne

llie important, question then is

'’her this disparity between the 25%

’ died Negro electors in Ashley' County

’he 6.67% selected for jury service,

’he result of excluding Negroes from

S.W.2d—26

v. STATE Ark. 401

,W.2d 395

jury service because of their color or race.

Of course, unexplained prior, or “systemat

ic,” exclusion of Negroes from jury serv

ice would leave the inference they were

excluded because of their race if no other

explanation is given; consequently, prior,

or systematic, exclusion is admissible m ev

idence in support of a claim of intentional

exclusion because of race in a given case.

Tire evidence on this point, in the case-at

bar, includes the percentage of Negroes on

the jury panels for a ten year period prior

to the October 1964 term here involved.

These percentages vary from none in two

adjourned March 1960 terms to 24% in one

adjourned March term, but they average

only 9.42%.

The three jury commissioners who se

lected the jury panel from which the jury

was selected in this case were called by the

appellant and testified at his Rule No. 1

hearing. On direct examination all thi ec

were questioned on collateral matters ap

parently aimed at bringing to the surface

any personal feeling that could be inter

preted as racial prejudice, such as to their

membership in the NAACP or any pre

dominately Negro civic and social organi

zations, and as to whether the membership

of the churches to which they belong were

predominately' black or white. As to the

actual question involved on this appeal, we

deem it unnecessary to set out the testimo

ny of the commissioners in detail but, Mr.

Charles Grassi, one of the commissioners,

testified that in selecting the jury panel the

commissioners were furnished a list of the

jurors for the past several years which

they used in determining who was eligible

to serve. lie testified that they were also

furnished with a county poll tax list and

that as he recalls, the poll tax list did des

ignate the race beside the name of each of

the qualified electors. He then said:

“Of course, there was three of us. We

went down the lists and if one or three

of us knew -the man that was under dis

cussion and knew who he was, we would

see if he was qualified, a registered vot

er.”

402 Ark. 496 SOUTH WESTERN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

Mr. Grassi testified that they tried to

pick the members of the jury panel from

different sections of the county, and that

he was acquainted with Negroes who lived

in and around Crossett. He said that he

did not know them personally but knows

them by name and when he sees them. He

said he did not know them well enough, to

know what occupation they were engaged

in but did know 20 or 25 of them well

enough to know their general character,

lie said that the trial judge instructed the

commissioners to select people of sound

judgment, proven integrity and reasonable

information, and that the jurors should be

selected without regard of race, creed or

color. He said that in determining the

qualifications of the members of the jury

panel he based his opinion mainly on his

personal observations of the ones selected.

He testified that he made no effort to

familiarize himself with the character,

judgment and integrity of the Negroes in

the county with whom he was not already

personally acquainted. He said he was

personally acquainted with perhaps 20 or

25 Negroes and perhaps 250 white people

in and around Crossett well enough to ac

curately estimate their character.

Mr. Allen Cameron, another one of the

commissioners, testified that he had lived

in Ashley County since 1953 and is person

ally acquainted with 40 or 50 Negroes who

live outside the city of Crossett, and that a

majority of these individuals work for the

same company he works for. He said he

is acquainted with perhaps six or 12 Ne

groes who live inside the city of Crossett.

He said he is personally acquainted with

150 or 200 white people living in Ashley

County outside the city of Crossett and

perhaps 1,000 living inside Crossett. He

said he had no knowledge of the education

or qualifications of the Negroes he knows

in Crossett and does not know whether any

of them have criminal records or not. He

testified that he made no particular effort

to ascertain the qualifications of Negroes

or whites living in the community with

whom he was not already acquainted.

Mr. Ray Phillips, the third coir

testified that he is a general men

ing in Fountain Hill, and had bee:,

chant in Ashley County for 42 y<

er being asked if the member

church were all white or all N,

Phillips readily admitted that he

believe in white and black people .

school or eating in cafes together,

Mr. Phillips just as readily testifu

lows:

“Q. So, you tell me whether y

a negro man or a number of

should be able to sit in judgm

white man accused of a capita'

A. Well, if he is qualified, IV

soon have him as some of the

The substance of the remainder

Phillips’ testimony was to the ei‘

he knew the people in his comma:

assumed that the other two comm

knew the people in their respect:

munities; that he recommended

service the ones from his comm;

knew to be high class citizens and

the other commissioners did likeu

From the overall testimony of

missioners there is no question

procedure they followed in selc<'

jury panel in this case. They s:t

amined the list of qualified electoi

lected the jury panel from among

viduals on the list some membra

commission knew. When they wc

to a name of a person one of the

sioners knew, that individual's

tions (other than being a qualifier'

would be discussed by the three

sioners and he would either be

for jury service or passed over,

commissioners would then contm

the list to the next person with "

of them was acquainted.

Crossett precinct is by far the r

ulated precinct in the county conic

names of 4,420 qualified electors 1

16.0% were Negro according to h"

list in evidence. There were 2.i "

_____ __2______— _UfiM «___ A v t d M k

R, 2d SERIES

V Phillips, the third commi

hat he is a general mere!',

untain Ilill, and had been

Ashley County for 42 yearv

asked if the members ,

ere all white or all Meg?

eadily admitted that he 4

white and black people at!

eating in cafes together, h

ps just as readily testified

>, you tell me whether you '

i man or a number of n>

be able to sit in judgment

tan accused of a capital c-

ell, if he is qualified, I’d ji

ve him as some of the oil

:ance of the remainder oi

estimony was to the effect

:he people in his communit;.

hat the other two commissi

people in their respective

that he recommended for

e ones from his communit

e high class citizens and as*

commissioners did likewise.

le overall testimony of the

there is no question as t

they followed in selecti:

1 in this case. They simpl;

5 list of qualified electors ar

jury panel from among the

i the list some member o:

n knew. When they would

of a person one of the cor

tew, that individual’s qua!

:r than being a qualified elc

discussed by the three cor.

id he would either be acc>;

service or passed over, and

tiers would then continue !

the next person with whom

is acquainted.

precinct is by far the most

:inct in the county container

4,420 qualified electors of

e Negro according to the v

lence. There were 25 whin

WILLIAMS v. STATE

Cite as 498 S.W.2d 393

. , ,1 jurors selected from this town-

going down the list” in selecting

mors from this township, the com-

i(!> started with R. L. Brooks, a

,. and ended with Richard Ro-

is Negro. From the name of R.

, ks as it alphabetically appears on

list, to and including Richard

there are 2,414 white and 475 Ne

stors listed. Consequently, the num-

electors the commissioners were

• to have considered between the

, t){ R. L. Brooks and Richard Rogers

(td nf slightly less than 13% Negro

:-iuly more than 87% white. Of the

hviduals selected 25 were white and

...u, Negro, making slightly less than

Negro and slightly more than 96%

vviburg is the next largest voting pre-

• containing 1,720 qualified electors of

; 11.3 were Negro. By the same proc-

■ ctween the first and last name select-

tn this township, the commissioners

• iutind to have considered the names of

- white and 180 Negro electors, making

v.d of 1,555 individual names of whom

vdy less than 12% were Negro and

:iy more than 8S% were white. There

• 15 jurors selected from this precinct

f whom were white.

here was a total of 322 qualified elec-

> listed in Fountain Hill precinct of

:n 44, or 13.7%, were Negro. There

c 12 members of the jury panel selected

'n this precinct, all of whom were

;e. The remaining seven jurors were

' ted from Wilmot, Boydell, Portland

1’arkdale precincts, with two Negroes

two whites being selected from Wilmot

met which contains 143 listed white

'ors and 122 Negro electors.

’■ is obvious that in selecting a jury ve-

f of 60 from a list of 8,656 qualified ju-

■' in a county, there are many times

rt individuals eligible for jury service

• there are positions to be filled. It is,

course, a matter of common knowledge

Ark. 4 0 3

that there are many reasons why many

qualified electors would be passed up for

jury service‘in preference to the ones se

lected. It may be that jury commissioners

would pass up some individuals for jury

service for economic reasons in recognition

of unusual hardships in individuals sacri

ficing their daily wages for the amount

paid for jury service. It is entirely possi

ble that persons working in industry who

have the qualifications for good juror

would also be working at jobs on which

other jobs depend and in many instances

jobs not easily filled by temporary assign

ment while the regular employee serves on

a jury. It may be that jury commissioners

take into consideration the handicap to the

employer as well as to the employee in

such cases in requiring the individual to

leave his job and serve on juries. The

same situation may apply in agricultural

sections of the state in the so-called "busy

season” of the year (planting and harvest

time) and, of course, many legally quali

fied electors may not possess the education,

sound judgment, experience or tempera

ment to sit as jurors and intelligently apply

the law as given in instructions to intricate

and complicated facts and render a fair

and impartial verdict in a given case. Be

that as it may, no such reasons were given

for excluding anyone for jury service in

the case at bar. As a matter of fact the

substance of the commissioners’ testimony

in the case at bar places them squarely

within the prohibition announced in the

cases above cited. They simply went down

the list of the qualified electors of the

county and selected the jury panel from

among the individuals with whom they

were personally acquainted. As already

pointed out, this procedure has been con

demned by the United States Supreme

Court when it results in considerable dis

parity between the races. Consequently,

when jury commissioners select jury panels

only from the people with whom they are

acquainted, they should he prepared to

show that they are as widely acquainted

with one race as with the other in the in-

404 Ark. 496 SOUTH WESTERN REPORTER, 2d SERIES

volved area; and when they select a high

percentage of white jurors from a list con

taining the names of a high percentage of

Negroes, the state must be prepared to ex

plain the discrepancy and affirmatively

show why the names of eligible Negroes

were passed over in preference of eligible

whites. I his was not done in the case at

bar.

BEN M. HOGAN COMPANY, cy,

Appellants,

v.

Will E. NICHOLS ct al., A ppr

No. 5-GI68.

Supreme Court of Arkan .i

July 2, 1973.

[4, Sj We regret that at this late date

Ashley County must be put'to the expense,

inconvenience and ordeal of again trying

Williams for that county’s most brutal

crime which occurred more than eight

years ago. The question of whether Wil-

Hams was guilty of the crime for which he

was convicted, or whether he was tried by

a fair and impartial jury, or whether his

rights were prejudiced by a trial before an

all white jury, is not involved on this ap

peal. Williams Jiad no constitutional right

to have Negroes on the jury before whom

he was tried and he had no constitutional

right to have Negroes on the panel from

which the jury was selected for his trial.

He was, however, entitled to be tried be

fore a legally constituted jury and a jury

from which members of any race have

been excluded simply because of their race,

is not a legally constituted jury.

It is clear that under the United States

Supreme Court decisions, supra, a prima

facie case of racial discrimination appears

on the face of the record in this case and

there was no evidence offered to rebut it.

Therefore, it is also clear, that we have no

other alternative, under the United States

Supreme Court decisions, than to reverse

the judgment in this case because of unre

butted. evidence of racial discrimination in

the selection of the panel notwithstanding

the fact that the selection was made under

a jury selection system that has now been

abandoned by appropriate legislation in Ar

kansas.

The judgment is reversed and this case

remanded for a new trial.

Subcontractor’s'employee’s t:

action against general contractor

other. A judgment was entered

defendants in the Franklin Circa

Ozark District, David Partain, ]..

defendants appealed. The Suprcnr

Foglcman, J., held that where the

plaintiff’s attorney had referred •

to a medical expert, not for treatte

the expert’s medical examination \

ducted in the presence of the j>\

wife and his attorney, and the ex;

quiries were answered in part by ::

and attorney, the expert’s opinion !

substantial part on such hearsay ,r

serving information was inadmissf

was specially prejudicial where the :

physician did not testify. The Co.:

held that admission of the terms

general contractor’s liability policy

ror.

Judgment reversed and cause r

ed.

I. Evidence <2=128

Generally, statements by injur

diseased person as to his current or

and symptoms, or as to past condit:

symptoms, made to physician cor.

examination for purpose of qualify

expert witness, and not for treatmc:

inadmissible.

2. Evidence <2=550(2), 555

Medical expert may base his <

as to prognosis of injury based up"

mony given at trial by another physic