Board of Education of the City of Bessemer v. Brown for a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Education of the City of Bessemer v. Brown for a Writ of Certiorari, 1967. 82390ec8-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/14eefa43-8800-4713-b672-bb085c5f24a9/board-of-education-of-the-city-of-bessemer-v-brown-for-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

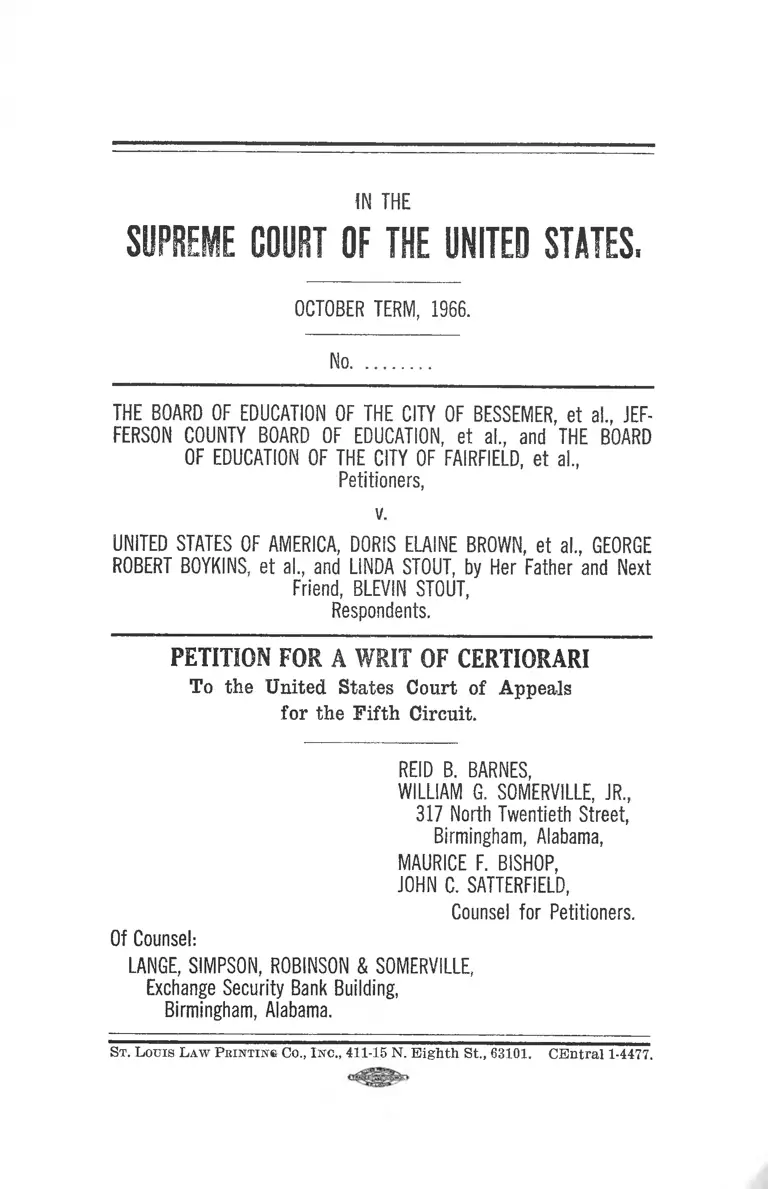

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1966.

No........................

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et a!., JEF

FERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al„ and THE BOARD

OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF FAIRFIELD, et al„

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, DORIS ELAINE BROWN, et al„ GEORGE

ROBERT BOYKINS, et al„ and LINDA STOUT, by Her Father and Next

Friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit.

REID B. BARNES,

WILLIAM G. SOMERVILLE, JR.,

317 North Twentieth Street,

Birmingham, Alabama,

MAURICE F. BISHOP,

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Of Counsel:

LANGE, SIMPSON, ROBINSON & SOMERVILLE,

Exchange Security Bank Building,

Birmingham, Alabama.

St. L ouis L aw P b in tin s Co., Inc., 411-15 N. E ighth St., 63101. C Entral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Prayer ........................................................................... 1

Citations to opinions below ......................................... 2

Jurisdiction ................. 2

Questions presented .................................................... 3

Constitutional and statutory provisions involved . . . . 4

Statement ..................................................................... 4

Reasons for granting the w r i t ...................................... 8

I. The requirement by the decision below of sub

stantial quantitative integration is erroneous

and conflicts with the decisions of the other

circuits ................................................................ 9

A. The decision imposes new constitutional

duties on the schools and on the students 9

B. The decision below conflicts with the deci

sions of the other circuits in its require

ments of mandatory quantitative integration 17

C. In holding that there is an absolute duty to

achieve substantial quantitative integration,

the decision below is erroneous and conflicts

with decisions of this court ............ 30

II. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not provide

authority for the decision .............................. 35

III. The requirement by the decision below of a

uniform detailed decree conflicts with the deci

sion of this court and other circuits .............. 38

Conclusion..................................................................... 39

Appendix A .................................................................. 41

Appendix B .................................................................. 46

Appendix C .................................................................. 48

11

Cases Cited.

Armstrong v. Board of Ed. of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d

333, 333 F. 2d 47 .................................................... 5,16

Bell v. School City of Gary, 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir.

1963), cert, denied, 377 U. S. 924

(1964) ................................................. 10,17,26,27,36,37

Board of Education of the Oklahoma City Public

Schools v. Dowell, F. 2d (8th Cir., January 23,

1967), cert, denied, 35 U. S. L. Week 3418 (IT. S.

May 29, 1967) ......................................................29,30

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 48 (5th Cir. 1960) __ 16

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City

County, Va., F. 2d (4th Cir., June 12, 1967) ......... 19

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310

(4th Cir.), vacated and remanded on other grounds,

382 U. S. 103 (1965) ......................................5,17,33,38

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C.

1955) ..............................................................17,19,21,36

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263 (1964) ................ 33

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School

Dist., 369 F. 2d 661 (4th Cir. 1966), rehearing de

nied, 374 F. 2d 569 (8th Cir. 1967) .......................21,37

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 IT. S. 1, 19 (1958) .................... 31

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Ed., 369 F. 2d 55 (6th

Cir. 1966) ............................................................... 24,27

Downs v. Board of Education of Kansas City, 336 F.

2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 380 IT. S.

914 (1965) ........................................................ 26,27,30

Goss v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville, 373

U. S. 683, 687, 689 (1963) ...................................... 33

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Va., F. 2d (4th Cir., June 12, 1967) ......................19-20

Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville,

270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959) 25

Ill

Lockett v. Board of Ed., 342 F. 2d 225 (5tli Cir. 1965) 5

Olson v. Board of Education of Malverne, N. Y., 250

F. Supp. 1000, 1006 (E. D. N. Y. 1966) ................ 32

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198 (1965) ...........................5,38

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Bd. of Ed., 358 U. S.

101 (1958) ............................................................... 33

Springfield School Committee v. Barksdale, 348 F. 2d

261, 264 (1st Cir. 1965) ........................................... 26

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 333 F. 2d 55, 59 (5th Cir. 1964) .................... 16

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202, 226-28 (1965) . . . . 34

Statutes Cited.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stats. 246, Sections 401,

407, 601, 602 and 604 ............................................ • 4

Constitution of the United States:

Fourteenth Amendment ........................................... 4

28 U. S. C., § 1254 (1) .............................................. 2

Textbooks Cited.

Bickel, “ The Decade of School Desegregation,” 64

Colum. L. Rev. 193, 213-15 (1964) ........................... 15

Dr. Max Wolff, “ The Educational Park,” Conference

on Education and Racial Imbalance in the City,

p. 4 (March, 1967) .................................. - ............ 27

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools (1967). .24, 26, 28, 34

Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

Border States, 1965-66 (Feb. 1966) ....................... 14

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1966.

No.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF BESSEMER, et al., JE F

FERSON COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al., and THE BOARD

OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF FAIRFIELD, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, DORIS ELAINE BROWN, et al„ GEORGE

ROBERT BOYKINS, et al., and LINDA STOUT, by Her Father and Next

Friend, BLEVIN STOUT,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

To the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit.

The Board of Education of the City of Bessemer et al.,

Jefferson County Board of Education et al., and the Board

of Education of the City of Fairfield et al., pray that a

writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, en

tered in the above-entitled causes on March 29, 1967.

2 —

CITATIONS TO OPINIONS BELOW.

No opinions were written by the District Court,.1 Two

decisions were rendered by the Court of Appeals. The

original decision of a panel of the Court (Record, Vol. IV,

p. 6) is reported at 372 F. 2d 836, and is printed in Ap

pendix L to the petition in Caddo Parish School Board v.

United States, filed in this Court in June, 1967. The opin

ions on rehearing by the court en banc (Record, Vol. IV,

p. 12) is not yet reported, and also is printed in Appendix

L to the petition in Caddo Parish School Board v. United

States. Since the petitioners herein were consolidated in

the Court of Appeals for purposes of argument and de

cision with petitioner in Caddo Parish v. United States,

these petitioners ask leave to incorporate herein by refer

ence Appendix L to the petition in Caddo Parish,2

JURISDICTION.

The original judgments of the Court of Appeals were

entered on December 29, 1966 (Record, Vol. IV, pp. 7A-

7C). A timely petition for rehearing en banc (R. Vol. IV,

p. 8) was granted (R. Vol. IV, p. 9). The judgments of

the Court on rehearing en banc were entered on March

29, 1967 (R. Vol. IV, p. 13). The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C., §1254 (1).

1 The D istrict Court orders from which the appeals to the

Court of Appeals were taken are at the following pages of the

Transcript of R ecord: Jefferson County, Transcript Vol. I,

pp. 70-71; Bessemer, Transcript Vol. II, pp. 85-86; Fairfield,

Transcript Vol. I l l , pp. 65-66.

2 Citations herein to the opinions below will include refer

ences to page numbers of the slip opinions printed in Appen

dix L.

— 3 —

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

1. Whether the sole measure of the constitutional ad

equacy of a method of student assignment in public

schools is that it results in a prescribed number of per

centage of Negro children at schools with white children

or a progressive change in the racial ratios of students

ultimately removing racial imbalance or concentration.

2. Whether the Fourteenth Amendment imposes upon

Negro children who freely choose to attend certain schools

a duty to attend other schools in order to eliminate racial

concentrations or imbalances in the schools chosen by

them.

3. Whether a “freedom of choice” method of student

assignment whereby all children have the unrestricted

right to choose annually to attend any school in the sys

tem is rendered unconstitutional solely because it does

not achieve prescribed percentage or numerical results

reducing or removing racial imbalances or concentrations.

4. Whether an unrestricted “ freedom of choice”

method of student assignment must be combined with a

neighborhood school or geographic zone method of as

signment in order to be constitutionally adequate.

5. Whether there is a constitutional distinction between

the existence in Northern school systems of racially im

balanced schools under “ neighborhood” assignment plans

and the existence in Southern school systems of similarly

imbalanced schools under “ free choice” assignment plans

such as to require elimination of the imbalance in the

Southern schools but not in the Northern schools.

6. Whether the requirement by a court of appeals of a

detailed decree to be applied uniformly to every school

system in the circuit without affording an evidentiary

hearing as to the necessity or the effect of its provisions

— 4 —

on local educational and administrative functions un

related to race is consistent with Brown v. Board of Edu

cation and other decisions of this Court.

7. Whether questions concerning the validity and pro

priety of the Court of Appeals’ adoption of the so-called

“ 1966 Guidelines” of the Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare were properly before and appropriate

for decision by the Court of Appeals although the “ Guide

lines” were not issued until after the appeals were dock

eted, and, if so, whether such “ Guidelines” are valid and

within the Congressional intent of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964.

8. Whether it is proper for a federal appellate court to

adopt present and future regulations issued by the De

partment of Health, Education and Welfare for administra

tion of federal funds under Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 as the court’s constitutional standards in de

termining rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED.

The constitutional provision involved is Section I of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States. The statutory provisions involved are

Sections 401, 407, 601, 602, and 604 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 246. They are printed in Appendix

A, infra.

STATEMENT.

Each of the petitioners is a local school board in

Jefferson County, Alabama. These actions were com

menced by complaints filed in the spring of 1965.3 The

3 The Bessemer complaint was filed on May 24, 1965, the Je f

ferson complaint on June 4, 1965, and the Fairfield com

plaint on Ju ly 21, 1965.

5

District Court, per Judges Lynne and Grooms, granted

(with virtual consent of defendant’s counsel)4 the relief

as prayed and ordered the submission of desegregation

plans. The plans filed by the Boards several days there

after were considered by the District Court to be consist

ent with the requirements of the Fifth Circuit’s decisions

as of that time,3 and the objections of the plaintiffs and

the United States accordingly were overruled. Appeals

from these orders were taken in the Bessemer and Jeffer

son cases and on August 18, 1965, the Court of Appeals

remanded each for consideration in light of two recent

Fifth Circuit decisions. In accordance with the mandates

of the Court of Appeals, the plans in Bessemer and Jeffer

son were amended on August 27, 1965, and on the same

day the District Court held the amended plans to be in

compliance with the Fifth Circuit decisions and entered

orders overruling objections to them.6

The present appeals were taken by the United States

from the orders of overruling objections entered on Au

gust 27, 1965, in Bessemer and Jefferson, and on August

18, 1965 in Fairfield.7 The Negro plaintiffs never appealed

4 See, for example, Record, Vol. II, pp. 127-28.

5 And they were consistent with the F ifth Circuit decisions.

See, e. Armstrong v. Board of Ed. of Birmingham, 323 F.

2d 333, 333 F. 2d 47; Lockett v. Board of Ed., 342 F. 2d 225

(5th Cir. 1965).

e The plans contained no provision for faculty desegregation,

but they were filed and the present appeals were taken from

orders entered before this Court’s decision in Bradley v. School

Board of City of Richmond, 382 U. S. 103 (1965), and Rogers

v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198 (1965), and a t a time when the F ifth

Circuit did not require provisions for faculty desegregation, see

Lockett v. Board of Ed., supra.

" Because of this Court’s often expressed concern for time

in school cases, the considerable lapse of time between the date

of the orders appealed from and the date of the F ifth Cir

cuit’s decision now sought to be reviewed deserves an explana

tion. Much of the delay is attributable to the United States

— 6 —

from these orders. They moved to intervene, however,

when the appeals were set for argument.

These three cases were consolidated on appeal with

four cases involving Louisiana school boards, and a panel

of the Court of Appeals rendered a decision (with one

dissent) reversing all of the cases and directing the Dis

trict Courts to enter a uniform decree appended to its

opinion. A petition for rehearing en banc was granted

and on March 29, 1967, a majority of the court en banc

entered a per curiam opinion adopting the panel’s opinion

and decree with minor “ clarifying statements” . Three

members of the Court dissented and one concurred in the

reversal but disagreed with the substance of the opinion.

Although the two majority opinions discussed many

questions, their substance was that Southern school sys

tems have, by reason of their previous practice of segre

gation, a constitutional duty to achieve what the court

termed “ substantial-integration” , which is to be measured

by the numerical or percentage results obtained. Over

ruling its prior decisions holding that the Fourteenth

Amendment only prohibits enforced segregation but does

not compel actual integration, the court held further that

an unrestricted “ freedom of choice” plan is constitu

tionally inadequate unless it achieves the required results.

The decision and decree were intended to be applicable

uniformly to all school systems in the circuit.

The original desegregation plans and the facts appear

ing before the District Court are not only out-of-date but

which utilized through extensions the maximum permissible

time for noticing and docketing the appeals—thereby consum

ing a period of some seven months before the appeals were

docketed. The cases were argued before the panel on May 23,

1966, and another seven months elapsed before the decision

was rendered on December 29, 1966. Arguments on rehearing

en banc were heard on March 10, 1967, and the judgm ents on

rehearing entered on March 29.

7

are immaterial to the decision of the court below and to

the issues raised in this petition. They are out-of-date

because the appeals were taken immediately after adop

tion of the plans and before they could be administered

or their effects could be gauged. The record therefore

does not reflect the changes adopted by the Boards in

their administration and resulting in their liberalization.8

More important, the only facts either material to or men

tioned in the decision below were that the school systems

involved (as well as all other systems in the South) were

previously segregated by law and that the numerical

results of their plans were insufficient. The opinion was

not premised on any determination that the petitioners

were still operating “ de jure” segregated schools at the

time of the decision, but on the fact that they previously

had “ de jure” segregation. The decision did not pur

port to be merely based on or limited to any factual

circumstances peculiar to only the particular school

boards which were parties. It was based instead on

broad constitutional principles which are intended to

govern all school systems in the circuit without regard

to variations in details of factual circumstances. Like

wise, the existence of the good faith of the school boards

is immaterial to the decision. The only test of the con

stitutional adequacy of a board’s desegregation efforts is

the objective results, not whether the board has acted in

good faith. The opinion does not mention the existence

or absence of good faith by the petitioner boards, and the

records of the present cases in the District Court contain

nothing evidencing anything other than good faith.■*

8 As they have been administered since the appeals were

taken, the plans have afforded all students an annual righ t to

choose any school in the systems. This righ t has not been lim

ited by any tests or other criteria of any sort. So fa r as we

are aware, no student’s choice has been denied for any reason.

» The plans adopted by the petitioner boards at the time

of these appeals in 1965 were held by the District Court to eon-

form with the F ifth Circuit’s previous decisions.

— 8 —

Nor are the nature of the plans adopted in 1965 or the

evidence in the District Court material to the issues raised

by this petition.10 Petitioners do not contend now, and

did not maintain in the court below, that certain details

of those plans are now sufficient in the light of develop

ments in the law subsequent to the appeals, such as the

decisions concerning faculty desegregation. The points

raised here thus are not that the old plans are facially

adequate, but that the new constitutional standards re

quired by the Fifth Circuit are improper—particularly as

they relate to the student assignments.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT.

Petitioners are fully aware of the extent of the Fifth

Circuit’s experience with school desegregation suits. As

its opinions themselves recognize, however, its decision in

the present cases marks a far-reaching and substantial

departure from any previous decision by it or any other

federal appellate court. It admittedly establishes for this

circuit new concepts of the nature of the constitutional

standards and the forms of remedy which will govern

public schools. Particularly with regard to questions of

student assignment, it is believed that the constitutional

standard adopted by the Court of Appeals is based on a

misconception of the fundamental nature of the constitu

tional right established in Brown v. Board of Education.

In any event, however, the decision is in direct conflict in

this respect with recent desegregation decisions of the

10 There was evidence in the D istrict Court on behalf of the

respondents aimed at showing the physical inferiority of pre

dominantly Negro schools. Due to insufficient time, however,

the D istrict Judge was unable to allow the petitioner an op

portunity to present evidence in rebuttal (See Record, Vol. II,

pp. 259, 265, 267). Accordingly, when petitioners disputed on

appeal th a t the schools were inferior, counsel for the United

States, Mr. David Norman, acknowledged during the original

oral argum ent that the cases should be remanded for further

evidence on this question.

— 9 —

Fourth and Eighth Circuits and conflicts at least in prin

ciple with decisions of other circuits. Moreover, its im

portance is clear: the decision and the detailed decree

affect not only the petitioners but are expressly directed

by the court to be followed by every school system in the

six states comprising the circuit; and by reason of the

principles on which it is premised, it unquestionably

would apply to most of the school systems in the Fourth

and Eighth Circuits and should apply to school systems

in every other circuit in which schools with racial con

centrations now exist.

L

The Requirement by the Decision Below of Substantial

Quantitative Integration Is Erroneous and Conflicts

With the Decisions of the Other Circuits.

A. The Decision Imposes New Constitutional Duties on

the Schools and on the Students.

Despite its length and discussion of numerous subsid

iary questions, the decision of the court of appeals rests

on several fundamental points. The most basic is its

determination that the Fourteenth Amendment and deci

sions of this Court require the achievement of “ substan

tial-integration’ ’ in terms of favorable statistics showing

the numbers of Negro children who attend certain schools.

Corollarilv, it holds that a so-called freedom-of-choice

method of student assignment—and, indeed, any other

method of assignment—-is constitutionally insufficient in

Southern states unless it results in “ substantial-integra

tion.” A subsidiary but related point underlying the

decision is that the constitutional requirement of “ sub

stantial-integration” applies only to schools in states

which previously permitted or required school segregation

by law (characterized as “ de jure segregation” ) but not

— 10 —

to schools in states which in 195411 had no laws requiring

or permitting segregation (characterized as “ de facto

segregation” ). Also related is its reliance on Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as a congressional recog

nition of a requirement of substantial-integration in the

Southern school systems but not in the North. Another

major aspect is the decision for the first time in any

school case that a minutely detailed decree be dictated

by an appellate court for uniform use by all school sys

tems in the circuit without reference to or regard for

local differences and needs.

The main thrust and basis of the decision are that the

Fourteenth Amendment requires in the South “ substan

tial-integration” and that any means of student assign

ment in the South is unconstitutional if it does not meet

that requirement. Its keystone is the principle reiterated

throughout the opinion that, “ The only school desegrega

tion plan that meets constitutional standards is one that

works,” 12 and that, “ As the Constitution dictates, the

proof of the pudding is in the eating: the proof of a school

board’s compliance with constitutional standards is the

result.” 13 The nature of this constitutional duty and the

court’s meaning of one that “ works” is explained as be

ing that:14

[T]he law imposes . . . an absolute duty to integrate

in the sense that a disproportionate concentration of

Negroes in certain schools cannot be ignored; racial

11 Thus, it distinguishes Bell v. School City of Gary, 324 F.

2d 209 (7th Cir., 1964), on the ground th a t it involved “de

facto” segregation even though tha t school system had oper

ated segregated schools perm itted by law as late as 1949 (page

63; 372 F. 2d at 873).

12 Page 7; 372 F. 2d at 847.

18 Page 112; 372 F. 2d at 894.

14 Page 6, n. 5; 372 F. 2d at 846-47.

11

mixing of students is a high priority educational goal.

The law does not require a maximum of racial mix

ing or striking a racial balance accurately reflecting

the racial composition on the school population. It

does not require that each and every child shall at

tend a racially balanced school. This, we take it, is

the sense in which the Civil Rights Commission used

the phrase ‘ ‘ substantial-integration. ’ ’

The decision then predicates the achievement of “ sub

stantial-integration” and the constitutionality of a school

system on the attainment of prescribed percentages of

Negro students in attendance at schools with whites:15

In reviewing the effectiveness of an approved plan

it seems reasonable to use some sort of yardstick or

objective percentage guide. The percentage require

ments in the [HEW] Guidelines are modest, suggest

ing only that systems using free choice plans for at

least two years should expect 15 to 18 per cent of

the pupil population to have selected desegregated

schools.

Finally, if these quantitative results are not achieved, the

decision requires the adoption of whatever means are

necessary to accomplish them. The panel’s opinion thus

concludes:16

If school officials in any district should find that

their district still has segregated faculties and schools

or only token integration, their affirmative duty to

take corrective action requires them to try an alter

native to a freedom of choice plan, such as a geo

graphic attendance plan, a combination of the two,

the Princeton plan, or some other acceptable substi

tute, perhaps aided by an educational park.

15 Page 95; 372 F. 2d at 115.

16 Page 115; 372 F. 2d at 895-96.

Adopting the panel opinion, the rehearing opinion added

with regard to the percentage requirements:

The percentages are not a method for setting

quotas or striking a balance. If the plan is inef

fective, longer on promises than performance, the

school officials charged with initiating and adminis

tering a unitary system have not met the constitu

tional requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment;

they should try other tools.

The substance of the decision, then, is that while the

achievement of a perfectly proportionate balance is not

necessarily required, yet the elimination of imbalance

and the achievement of a certain prescribed degree of

“ racial mixing” (“ substantial-integration” ) is constitu

tionally mandated.17

In the context of an unrestricted “ free choice” plan,

the concomitant to this requirement is that a similar duty

is constitutionally required equally of the children

(colored and white) as of the school officials and that the

achievement of “ substantial-integration” is required

without regard to—and, indeed, notwithstanding—the stu

dents’ individual choices and preferences. School officials

are required to compel all children to attend certain

schools to the end that “ substantial-integration” may be

achieved, notwithstanding that the children have affirma

tively chosen the schools they attend. If their choices

do not measure up to the court’s concept of “ substantial-

integration,” a means of assignment must be adopted

which will force them elsewhere. Realizing this effect of

its decision, the rehearing opinion concludes: “ A school

child has no inalienable right to choose his school.” This

17 Of course, whether the percentage requirements are char

acterized as a “rule of thum b” or as a strict condition is im

m aterial to the fundamental constitutional question which they

raise—whether the Fourteenth Amendment requires quantita

tive results.

13

conclusion evidently is based upon the court’s reading of

the Brown decisions and the Fourteenth Amendment as

subordinating the rights of individual Negro students to

a theoretical group right of “ Negroes as a class” to an

integrated education.18

These principles not only form the basis of the de

cision, but also are manifested in certain provisions of its

uniform decree. Thus, Section II (d) of the decree al

ready requires the replacement of freedom of choice with

a geographic zone or a neighborhood school assignment

plan subject to a right of transfer through exercise of the

choice procedures; it requires assignments by residence

unless a student affirmatively chooses to go elsewhere.19

The practical effect of blindly requiring quantitative

integration without regard to other considerations can be

demonstrated by the results of the choices made in the

Bessemer system for the 1967-68 school year—which will

be the third year Bessemer has used freedom of choice.

The choice period was held from May 1 to June 1, 1967,

and all of the requirements of publicity, letters, forms,

etc., dictated by the Fifth Circuit’s uniform decree were

followed. All grades were included. Of the total Negro

enrollment of 5,127 in the Bessemer schools, the number

of students returning their choices was 3,348. Of that

number, only 146 chose to attend predominantly white

schools. A total of 3,202 Negro students affirmatively

18 This view of Brown as a governing basis of the decision

is evident throughout the panel’s opinion and is discussed

there in detail a t pages 46-59, 372 F. 2d a t 866-70. For example,

it maintains tha t the “righ t of the individual plaintiffs must

yield to the overriding righ t of Negroes as a class to a com

pletely integrated public education.” I t is never explained who

comprises this class if it is not the individual Negroes.

19 Section II (d) provides in pertinent p art th a t:

“Any student who has not expressed his choice of school

within a week after school opens shall be assigned to the

school nearest his home where space is available. . . .”

14 —

chose to remain in their former schools. The percentage

“ results” are: only 4.17% of the students in Bessemer

have selected desegregated schools.20 Since this of course

falls far short of the Court’s concept of “ substantial-

integration” as demanding that “ 15 to 18 percent” of

the pupils select desegregated schools in systems using

free choice plans for two years, the decision expects the

Bessemer system to adopt now another method of assign

ment which will accomplish the required results. In

doing so it presumably will override the expressed choices

of the 3,202 Negro students who elected to remain in their

present schools and compulsively assign them elsewhere.

In assessing the meaning of this, it is to be noted that

the personal reasons actually motivating the students’

choices are not revealed anywhere in these cases, were not

considered or mentioned by the Court of Appeals, and

indeed are rendered altogether irrelevant by its deter

mination that the quantitative result is the only consti

tutional concern. It seems impossible to read any such

meaning into Brown unless the Court of Appeals is inter

polating a conclusive presumption that the choices made

by the Negro children were caused solely by fear, in

timidation, or other extraneous pressures. But there is

not the slightest indication in fact that the choices made

by students in the petitioner systems have been influenced

by anything except genuine preference. On the contrary,

a recent report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights21 reveals that reasons given by Negro children in

actual interviews included the desire to remain with their

friends, to continue their participation in school activi

ties, and a feeling of identification with and pride in a

particular school for the usual reasons any student identi-

20 This includes 67 other students who attended predom

inantly white schools last year and will return next fall.

21 Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

Border States, 1965-66 (Feb. 1966).

15 —

lies himself with the school he attends.22 However unim

portant these reasons might seem in comparison with

other educational purposes, it hardly seems proper for a

court to arrogate to itself, especially under the guise of

enforcing constitutional rights, the authority to determine

that the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a child from

associating with his friends. Since there has been no

opportunity for any evidentiary determination as to

whether freedom of choice in the present school systems

does not in fact serve the preferences and interests of

the students, no one (including the court below) is in a

position now to adequately appreciate or anticipate the

actual effect which the court’s requirement of quantita

tive results will have on the students themselves.23

22 See also, Bickel, “The Decade of School Desegregation,”

64 Colum. L. Rev. 193, 213-15 (1964).

28 The danger of such precipitate action by an appellate

court on the basis of theoretical concepts and without con

sideration of individual factual circumstances is illustrated by

an occurrence this spring in the school system of Okaloosa

County, Florida. There, in accordance with a desegregation

plan adopted pursuant to H. B. W. requirements, the school

system closed a formerly all Negro high school (Combs) and

assigned all its 107 Negro students to a formerly all white

high school for the 1966-67 school year. On May 9th, the Civic

League of F ort W alton Beach, a Negro organization, petitioned

the school board to reopen the closed Negro high school and

to allow the re tu rn of its Negro students. The Negro spokes

man explained th a t they were “not fighting integration, but

rather wanted each student to have the right to attend what

ever school he wishes.” F ort W alton Beach, Florida, “P lay

ground Daily News,” May 10, 1967, p. 1, eol. 4. The basis of

their request, as set forth in the petition, wTas th a t of the 107

Negro students who had previously attended Combs school but

were required to attend a different school this year, 46 had

dropped out of school as of March 3 (Page 30 of the Petition

filed with the Board of Public Instruction of Okaloosa County,

Florida). This was stated by the Negroes’ petition to represent

an increase of 2,033% in the number of dropouts in the Negro

students formerly attending Combs High School during the

1966-67 school year as compared with the school years from

1962 to 1966. Ibid. The Negro organization submitted to each

of the 46 dropouts questionnaires which revealed th a t all 46

wanted a high school education and wanted to re tu rn to Combs

— 16 —

In order to reach its conclusion that the Constitution

absolutely compels quantitative integration, it was neces

sary for the Fifth Circuit to expressly overrule previous

decisions which until then had consistently interpreted

Brown as meaning that, “ The equal protection and due

process clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment do not

affirmatively command integration, but they do forbid

any state action requiring segregation on account of their

race or color of children in the public schools.’’24

The court recognized that in doing so it was departing

from its previous concept of the controlling constitu

tional standards: “ Expressions in our earlier opinions

distinguishing between integration and desegregation

must yield to this affirmative duty we now recognize.”23

The importance of this departure to the decision is in

dicated by the fact that the opinion devotes no less than

35 pages26 to an attack on its prior interpretation of

High School. Id,., a t 22, 23. This information and a copy of

the petition were obtained on May 22 from the attorney for

the Board of Public Instruction of Okaloosa County, Florida,

Mr. Erwin Fleet of F ort W alton Beach. I t is difficult to see

how the “educational opportunity” of these 46 children was

improved by their compelled attendance at the predominantly

white school.

24 Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 48 (5th Cir. 1960) (Rives,

C. -J.). The en banc opinion lists nine of its former decisions

which it overruled, and there are others to the same effect

which it did not list. Similar examples of statem ents in the

F ifth Circuit decisions a r e : “Nothing contained in this opinion

. . . is intended to mean tha t voluntary segregation is unlaw ful;

or that the same is not legally permissible.” Armstrong v. Board

of Education of City of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333, 339 (5th

Cir. 1963) (Rives, J .) ; “No court has required a ‘compulsory

racially integrated school system’ to meet the constitutional

m andate tha t there be no discrimination on the basis of race

in the operation of public schools. . . . The interdiction is

against enforced racial segregation.” Stell v. Savannah-Chat-

ham County Board of Education, 333 F. 2d 55, 59 (5th Cir.

1964) (Bell, J .) .

25 Rehearing opinion, p. 5.

2« pp. 28-73; 372 F. 2d at 861-78.

— 17

Brown as similarly expressed (and still adhered to) in

decisions of other jurisdictions—such as Briggs v. Elliott,

132 F. Supp. 776 (E. I). S. C. 1955), and Bell v. School

City of Gary, 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963), cert, denied,

377 U. S. 924 (1964). Inasmuch as the central issues and

principles of the decision relate to the definition of the

essential nature of the rights and duties decreed by

Brown I rather than mere remedial details, the decision’s

impact and application extend beyond this circuit.

B. The Decision Below Conflicts With the Decisions of

the Other Circuits in Its Requirements of Mandatory

Quantitative Integration.

Both in its governing constitutional principles and in

each of its fundamental requirements discussed above27

the decision of the Fifth Circuit is in conflict with the

decisions of every other circuit which has considered

these questions.

1. Fourth Circuit. In Bradley v. School Board of Rich

mond, 345 F. 2d 310 (4th Cir.), vacated and remanded

on other grounds, 382 U. S. 103 (1965), a majority of the

Fourth Circuit sitting en banc approved without quali

fication a freedom-of-choice method of assignment which

the court below now rejects.28 The Negro appellants

27 That the Fourteenth Amendment requires “substantial in

tegration” measured by quantitative re su lts ; th a t the only

constitutionally adequate method of student assignment is one

which achieves such “results” ; th a t a freedom-of-choice method

of assignment is inherently inadequate and must be abandoned

if it has failed to achieve those results; and tha t freedom of

choice is permissible only if superimposed on geographical

zones.

28 The Richmond plan, as described in 345 F. 2d at 315,

provided “for a freedom-of-choice by every individual in the

Richmond School system as to the school he attends. There

also is a requirement th a t the choice be affirmatively exercised

by every pupil entering the system for the first time and by

every other pupil as he moves from one level to another.” It

is the same plan which petitioners unsuccessfully urged the

F ifth Circuit to approve in the present cases.

18 —

urged that it be rejected for reasons similar to those on

which the decision of the Fifth Circuit is based. In reply

to the appellants’ insistence that the plan was unconsti

tutional because the preferences of Negro parents for pre

dominantly Negro schools “ result[ed] in the continuance

of some schools attended only by Negroes,” the Fourth

Circuit concluded (Id. at 316):

It has been held again and again, however, that

the Fourteenth Amendment prohibition is not against

segregation as such. The proscription is against

discrimination. . . . There is nothing in the Consti

tution which prevents his voluntary association with

others of his race or which would strike down any

state law which permits such association. The pres

ent suggestion that a Negro’s right to be free from

discrimination requires that the state deprive him of

his volition is incongruous. . . . There is no Pint [in

Brown] of a suggestion of a constitutional require

ment that a state must forbid voluntary associations

or limit an individual’s freedom of choice except to

the extent that such individual’s freedom of choice

may be affected by the equal right of others. A

state or a school district offends no constitutional

requirement when it grants to all students uniformly

an unrestricted freedom of choice as to schools at

tended, so that each pupil, in effect, assigns himself

to the school he wishes to attend.

To their contention that a freedom of choice plan is ade

quate only if it is combined with geographic assignments

based on residence, as provided in Section II (d) of the

Fifth Circuit’s decree, the Fourth Circuit concluded (Id.,

at 318-19):

We find, however, that an underlying geographic

plan is not a prerequisite to the validity of a freedom

of choice plan. A system of free transfer is an ac

ceptable device for achieving a legal desegregation

— 19 —

of schools. Its acceptability is not dependent upon

the concurrent use of some other device which also

might be adequate. . . . Imposed discrimination is

eliminated as readily by a plan under which each

pupil initially assigns himself as he pleases as by a

plan under which he is involuntarily assigned on a

geographic basis. . . . The other means [in addition

to geographic zoning] of abolishing the dual zone

system was to do away with zones completely. From

the point of view of the ultimate objective of elim

inating the illegal dual zoning, dezoning seems the

obvious equivalent of rezoning and, administratively,

far easier of accomplishment when the School Board

intends ultimate operation to be founded upon the

free choice of the pupils.

For its holding, the Fourth Circuit relied explicitly on

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955),

which the Fifth Circuit concluded to be inconsistent with

the constitutional requirements imposed by Brown. The

completely opposite results were reached by the Fourth

and Fifth Circuits in factual circumstances that were

identical insofar as they are material to the decision.

The basis of the Fifth Circuit’s decision that there is a

constitutional duty throughout the Fifth Circuit to achieve

“ substantial integration” is that everywhere in the South

(including Richmond, Virginia), due to “ formerly de

jure” segregation, “ the separation originally was racially

motivated and sanctioned by law.”29

Demonstrating more clearly its direct conflict with the

decision below are the Fourth Circuit’s recent en banc

decisions in Bowman v. County School Board of Charles

City County, Va., F. 2d (4th Cir., June 12, 1967), and

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, Va.,

29 See, e. g., Panel Opinion, page 77; En Banc Opinion, page

5, n. 1.

— 20 —

F. 2d (4th Cir., June 12, 1967), which are printed as

Appendix B, infra. None of the school systems involved

in those cases adopted any plan of desegregation until

after the commencement of suits in 1965. As the result

of those suits, each board adopted a freedom of choice

plan identical to that approved in Bradley—providing

only for permissive choices except when a student ini

tially entered the system or progressed to another school

level. It is evident from the opinions that the Negro

appellants challenged the adequacy of the plans on the

same grounds on which the Fifth Circuit’s decision is

based. Directly contrary to the decision below, a ma

jority of the Fourth Circuit held:

In this school case, the Negro plaintiffs attack, as

a deprivation of their constitutional rights, a “ free

dom of choice” plan, under which each Negro pupil

has an acknowledged, “ unrestricted right” to attend

any school in the system he wishes. They contend

that compulsive assignment to achieve a greater in

termixture of the races, notwithstanding their indi

vidual choices, is their due. We cannot accept that

contention . . .

If each pupil, each year, attends the school of his

choice, the constitution does not require that he be

deprived of his choice unless its exercise is not free.

This we have held and we adhere to our holdings.

Although the majority opinion of the Fourth Circuit con

sidered its decision to be consistent with the requirements

of the decree formulated by the Fifth Circuit in the pres

ent cases, it clearly did not purport to adopt the objective

of substantial quantitative integration as a constitutional

duty, and the concurring opinion of Judges Sobeloff and

Winter leaves no doubt that the Fourth Circuit’s decision

conflicts with the decision below in every major constitu

tional point which petitioners now raise regarding pupil

assignment. Most notably, it is pointed out that the

Fourth Circuit’s decision does not require mandatory an

nual choices with provision for compulsive assignments

“ to the school nearest his home” in event of a student’s

failure to exercise a choice, that it does not contemplate

that the sufficiency of a free choice plan be measured by

consideration of quantitative results, and that it does not

require that freedom of choice be replaced if it does not

result in actual integration. The concurring opinion also

points out that the Fourth Circuit continues to follow and

apply the principles in Briggs v. Elliott, in determining

the constitutional adequacy of desegregation plans. In

short, there is absolutely no way the Fourth Circuit’s de

cisions can be squared with that of the Fifth.

2. Eighth Circuit. The Eighth Circuit recently has ex

pressly rejected each of the major premises which the

Fifth Circuit sustained. Clark v. Board of Education of

Little Rock School Dist., 369 F. 2d 661 (4th Cir. 1966),

rehearing denied 374 F. 2d 569 (8th Cir. 1967). The as

signment features of the plan approved by the Eighth Cir

cuit in Clark were the same as those in the Fourth Circuit

decisions: an unrestricted freedom-of-choice plan with no

provision for geographic assignments on failure to make

a choice. The court rejected the contention that the con

stitutionality of a plan depends upon whether it “ works”

in achieving numerical results (369 F. 2d at 666):

Thus, they [plaintiffs] argue that the “ freedom of

choice” plan is not succeeding in the integration of

the schools.

Though the board has a positive duty to initiate

a plan of desegregation, the constitutionality of that

plan does not necessarily depend upon favorable sta

tistics indicating positive integration of the races.

. . . The system is not subject to constitutional ob-

— 22 —

jections simply because large segments of whites and

Negroes choose to continue attending their familiar

schools.

# # # #

In short, the constitution does not require a school

system to force a mixing of the races in schools ac

cording to some predetermined mathematical formula.

Therefore, the mere presence of statistics indicating

absence of total integration does not render an other

wise proper plan unconstitutional.

Regarding the validity in general of a freedom-of-choice

plan of the sort which petitioners urged the Fifth Circuit

to allow, the Eighth Circuit concluded:

Notwithstanding the H. E. W. Guidelines and the

recent opinion of the Fifth Circuit [in Jefferson

County], when a student is given a well publicized

annual right to enter the school of his choice, coupled

with periodic mandatory choices as set forth in the

Board’s amended plan, we can find on the face of it

no unconstitutional state action. We find no state act

that results in discrimination against Negroes [374

F. 2d at 571].

# # # # # # #

Therefore, if in fact all the students wishing to

transfer were fully accommodated, the constitution

would unquestionably be satisfied . . . [374 F. 2d

at 572].

# # # # # # #

If all of the students are, in fact, given a free and

unhindered choice of schools, which is honored by

the school board, it cannot be said that the state is

segregating the races, operating a school with dual

attendance areas or considering race in the assign

ment of students to the classrooms. We find no un

lawful discrimination in the giving of students a free

choice of schools [369 F. 2d at 666].

— 23

With respect to the contention that a free choice plan

must provide for a mandatory annual choice with geo

graphic assignments on failure to choose, the Eighth Cir

cuit stated:

They are afforded an annual right to transfer

schools if they so desire. The failure to exercise this

right does not result in the student being assigned

to a school on the basis of race. Rather, the student

is assigned to the school he is presently attending, by

reason of a choice originally exercised solely by the

student [369 F. 2d at 668].

# # # # % # #

On its face, we believe that the plan, as approved by

us, is proper and constitutional, and appellants have

made no showing that this non-mandatory freedom

of choice plan to laterally transfer schools has in

fringed their constitutional rights [374 F. 2d at 571].

It is true that in rejecting the Fifth Circuit’s present

decision, the Eighth Circuit commented that the “ factual

situation” was different in that the Fifth Circuit was

“ still dealing with dual attendance zones” and that “ a

much greater degree” of integration has been achieved

in Arkansas than the states “ directly concerned” in the

Jefferson County decision. However, the Fifth Circuit’s

decision was based upon much broader grounds than any

factual differences between Arkansas and the six states

comprising the Fifth Circuit—namely, that racial con

centrations in Southern schools (including those in Ar

kansas) were originally caused by legally enforced dual

school systems, and that Southern schools therefore have

an affirmative duty to do whatever is necessary to elimi

nate the disproportionate concentrations which are deemed

to be vestiges of the dual system. The Fifth Circuit’s

decision was not based on any notion that the petitioner

Boards continue now to have “ de jure” segregation, but

— 24 —

on the theory that all “ cases in this circuit involve

formerly de jure segregated schools” (E . g., Panel Opin

ion, p. 39). The Fifth Circuit’s decision was not based on

and did not involve dual attendance zones, which admit

tedly are eliminated by freedom of choice plans, but was

concerned solely with what it considered to be vestiges of

the dual school system. Further, the degree of integra

tion in Arkansas schools generally and in Little Rock

specifically is not so “ much greater” as to avoid appli

cation of the Fifth Circuit’s decision. Appendix A 1 to

the Eeport of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, Racial Isolation in Public Schools (1967), lists the

following as the percentages of total Negro elementary

students attending schools with 90 to 100 per cent Negroes

in sample Arkansas cities: Little Rock, 95.6%; Forrest

City, 98.3%; Helena, 99.5%; Jonesboro, 98.6%; Marvell,

98.1%; Pine Bluff, 98.2%; Hot Springs, 90.6%. Quite

plainly, none of the Arkansas schools approach achieve

ment of the “ substantial-integration” (15% to 18% after

two years) required by the Fifth Circuit’s decision. More

over, the Fifth Circuit’s decision is made expressly appli

cable to every school system in this Circuit, including

states and communities in which the degree of percentage

integration is equivalent to or quite substantially larger

than that in Arkansas.30

3. Sixth Circuit. The petitioners in Deal v. Cincinnati

Board of Education, No. 1358, October Term, 1966, assert

in their petition for certiorari that the Sixth Circuit’s

decision in Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Ed., 369 F. 2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), is in conflict with the Fifth Circuit’s deci

sion below. We agree. The Deal decision rests on that

circuit ’s interpretation of Brown as holding that the very

so p or example, the 1966-67 statistical summary compiled by

the Southern Education Reporting Service shows for the 1966-67

school year th a t the percentage of Negro enrollment in schools

with whites was 44.9% in Texas, 22.3% in Florida.

25 —

right which is accorded constitutional protection is the

individual student’s freedom of choice, and that the Four

teenth Amendment operates only to prohibit “ enforced

segregation” impinging on that freedom of choice.31

The decision of the Fifth Circuit, to the contrary, is

based on the totally inconsistent interpretation of Brown

resulting in its conclusion that “ freedom of choice is not

a goal in itself” and that “ a school child has no alienable

right to choose his school,” and indeed that in order to

effectuate a goal of “ substantial-integration” the Consti

tution affirmatively requires restriction on freedom of

choice for the individual by compelling his assignment to

other schools. See also Kelley v. Board of Education of

City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), where

the Sixth Circuit applied the same principles in the con

text of a desegregation plan adopted by a school system

which previously had a “ de jure” segregated system.

4. Other Circuits. A number of other circuits have held

uniformly that neither the Fourteenth Amendment nor this

Court’s decisions require school systems to eliminate or

relieve racial concentrations or imbalances in certain

schools not shown to result from purposeful and enforced

31 The Sixth Circuit thus concluded in Deal:

“The principle thus established in our law [by Brown

and subsequent decisions] is that the State may not erect

irrelevant barriers to restrict the full play _ of individual

choice in any sector of society. Since it is freedom of

choice that is to be protected, it is not necessary th a t any

particular harm be established if it is shown tha t the

range of individual options had been constricted without

the high degree of justification which the Constitution re

quires.”

# # # # # # *

“The element of inequality in Brown was the unnecessary

restriction on freedom of choice for the individual, based

on the fortuitous, uncontrollable, arb itra ry factor of his

race.

# * * # =& * «=

“We read Brown as prohibiting only enforced segrega

tion” [369 F. 2d at 59, 60],

— 26 —

segregation by the school boards. Springfield School Com

mittee v. Barksdale, 348 F. 2d 261, 264 (1st Cir. 1965);

Bell v. School City of Gary, 324 F. 2d 209 (7th Cir. 1963),

cert, denied, 377 U. S. 924 (1964); Downs v. Board of

Education of Kansas City, 336 F. 2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 380 U. S. 914 (1965). That several of these

cases involved school systems operated on a neighborhood

school basis rather than freedom of choice does not lessen

the conflict in controlling constitutional principle or in

deed in fact. To conveniently distinguish them with the

facile label of “ de facto” segregation is not only overly

simplistic but avoids the fundamental principles of con

stitutional interpretation on which the Fifth Circuit’s

decision is based. The Fifth Circuit’s decision is not based

on any finding that the petitioners or other school systems

in this circuit continue now to operate “ de jure” segre

gated schools or that they now engage in purposeful seg

regation or discrimination. And it could not have been,

since unrestricted free choice plainly is not legally en

forced segregation. Rather, it held that a duty to achieve

“ substantial-integration” to eliminate “ disproportionate

racial concentrations” extended to them because of their

“ formerly de jure” segregation.32 Its constitutional theory

is that despite freedom of choice, the existence of schools

with racial imbalances can be traced to past practices of

segregation. The court below accordingly recognized the

similarity between what is termed “ pseudo de facto segre

gation in the South,” in the form of continued isolation

caused by the students’ choices, and what it called “ actual

de facto segregation in the North.”33 Yet, the similar

degree of racial imbalance in northern schools can be

traced to the same or similar causes. Indeed, the Civil

Rights Commission observes in its most recent report:33®

32 Panel Opinion, pp. 14, 39.

33 Panel Opinion, p. 68.

33a Eacial Isolation in the Public Schools, p. 42 (1967).

— 27 —

“ These cases [involving Northern schools] appear

to be the legacy of an era, recently ended in some

places in the North, when laws and policies explicitly

authorized segregation by race. State statutes au

thorizing separate-but-equal public schools were on the

books in Indiana until 1949, in New Mexico and

Wyoming until 1954, and in New York until 1938.

Other Northern states authorized such segregation

after the Civil War and did not repeal their author

izing statutes until early in the 20th century.”

The Civil Eights Commission report goes on to cite

examples in a number of states and cities, including Cin

cinnati, Ohio, Illinois, Kansas, New Jersey and other

places where segregated schools were operated by law or

custom, some as recently as 1952 and 1954—the very places

involved in the Deal, Bell, Downs, and other cases cited

above. As the dissenting opinion of Judge Gewin in the

present cases points out, the principles on which the deci

sion below is based apply equally to the circumstances in

Bell v. School City of Gary, supra, since, as the district

court there observed (213 F. Supp. at 822), Gary, Indiana,

had operated a segregated dual system until 1949. The

only real distinction between those cases and this one is

that involved school systems which assigned students to

neighborhood schools, whereas here the students have

freedom of choice. However, it has been observed that

the relatively recent creation of neighborhood schools in

the North was racially motivated from the outset. As

stated by Dr. Max Wolff, Senior Research Sociologist for

the New York Center for Urban Education:34

“ The neighborhood school concept arose in the

twenties of this century, responding to the widespread

migration of Negroes to the North after World War I .”

34 Dr. Max Wolff, “The Educational Park ,” Conference on

Education and Racial Imbalance in the City, page 4 (March,

1967).

28

There simply is no distinction in constitutional prin

ciple between the segregation existing in the North and

that in the Fifth, Fourth, and Eighth Circuits. Every

where, North and South, school segregation is the result

of a complex variety of socio-economic causes and condi

tions including, both North and South, past official policy

and practices of school segregation.35 Certainly to a

greater degree than free choice methods of assignment in

the South, strictly administered neighborhood school poli

cies in the North involve official participation by school

officials in the creation and perpetuation of schools with

“ disproportionate racial concentrations.”36 The Fifth Cir

cuit’s decision now holds that there is a constitutional

duty applicable to all school systems in the South to

eliminate racial imbalance resulting from choices made

by students. Meanwhile, Northern cities with equally dis

proportionate racial concentrations in their schools37 and

with substantially equivalent or greater disparities in

physical facilities and pupil-teacher ratios as in the

South38 remain untouched by any duty under the Four

teenth Amendment to achieve the quantitative integration

35 United States Commission on Civil Rights, Racial Isolation

in the Public Schools, pages 200-02.

36 The Civil Rights Commission thus concludes that, “geo

graphical zoning, the most commonly used form of student as

signment in Northern cities, has contributed to the creation

and maintenance of racially and socially homogenous schools.”

Id., a t 202.

37 See Appendix A. 1, Report of U. S. Commission on Civil

Rights, Racial Isolation in the Public Schools (1967).

38 See Southern Education Report, page 4 (May; 1967),

setting forth a comparison of the physical characteristics of

.schools attended by Negro and white students in the whole na

tion and in the South, compiled from Table 2, page 11, of the

U. S. Office of Education Report, Equality of Educational Op

portunity (1966). It is revealed there, for example, that

whereas the average pupils per room in the whole nation is 34

for Negro students and 31 for white, in the metropolitan South

it is only 30 for Negro students and 34 for white.

29 —

which the Fifth Circuit now requires of the South. We

do not believe the Constitution is capable of such sec-

tionalization. If there exists any constitutional duty to

achieve “ substantial integration” , there is no basis in

fact or principle why the same duty does not govern

Northern school systems with segregated schools resulting

from substantially the same causes and having substan

tially the same characteristics as those in the South. We

submit, therefore, that the decision of the Fifth Circuit

is in conflict in both principle and fact with the decisions

of other circuits involving so-called “ de facto” segrega

tion. The conflict is compounded by the fact that all of

these decisions of other circuits expressly rely on the con

stitutional principles in the prior decision of the Fifth

Circuit which are now expressly overruled by the decision

below.

The Tenth Circuit’s recent decision in Board of Educa

tion of the Oklahoma City Public Schools v. Dowell,

F. 2d (8th Cir., January 23, 1967), cert, denied, 35 U. S. L.

Week 3418 (U. S. May 29, 1967), does not remove or les

sen this conflict. Dowell involved a strictly enforced geo

graphic zoning method of assignment, not freedom of

choice. The district court’s order did not require or con

template the achievement of “substantial integration” and

did not compel any student to attend a school for the

purpose of achieving integration. Indeed, the major in

novation by the district court was a form of free choice

—“ majority to minority” transfer provision which merely

permitted students to choose a school outside of

their zone. The district court’s order was based upon an

expressed finding of bad faith and a detailed evidentiary

study of the propriety of the plan it adopted to the pe

culiar circumstances of the Oklahoma City system; it was

not based on the broad concept of a constitutional duty

applying uniformly to all school systems in the circuit

regardless of good faith and local circumstances, as was

— 30 —

the decision of the Fifth Circuit. The Tenth Circuit’s af

firmance was predicated expressly on the district court’s

finding of bad faith, and it was on this ground that it

distinguished its former decision in Downs. The Tenth

Circuit’s decision in Dowell was very narrow and did not

purport to establish any new concept of constitutionnal law

consistent with that adopted in the present cases by the

Fifth Circuit. On the contrary, it expressly re-affirmed its

decision in Downs, where it had said:

Appellants also contend that even though the Board

may not be pursuing a policy of intentional segre

gation, there is still segregation in fact in the school

system and under the principles of Brown v. Board

of Education, supra, the Board has a positive and

affirmative duty to eliminate segregation in fact as

well as segregation by intention. While there seems

to be authority to support that contention, the better

rule is that although the Fourteenth Amendment pro

hibits segregation, it does not command integration

of the races in the public schools and Negro children

have no constitutional right to have white children

attend schools with them.

C. In Holding That There Is an Absolute Duty to

Achieve Substantial Quantitative Integration, the De

cision Below Is Erroneous and Conflicts With Decisions

of This Court.

The Fifth Circuit’s decision seems to be bottomed on

an interpretation of this Court’s decisions as establishing

a “ governmental objective of . . . educational opportuni

ties on equal terms to all”38 which imposes upon the

students and schools alike a duty to benefit Negroes as a

class39 even if it requires the subordination of the rights

88 Bn banc Opinion, page 6.

30 B. g., Panel Opinion, pages 47, 50, 51.

— 31 —

and preferences of individual Negro students to the as

sumed right of the class. Insofar as the decision looks

toward the attainment of equal educational opportunities

and requires to this end that the dual system be elimi

nated through elimination of racial distinctions in faculty

assignments, activities, and facilities, petitioners have no

fundamental quarrel. Insofar as this objective is con

sidered to embrace a duty on children and schools to

achieve “ substantial-integration”, however, petitioners

believe the Fifth Circuit has misconstrued the funda

mental substance of this Court’s decisions.

First, it would seem quite basic that this Court in

Brown I was concerned with and determined only the

rights of individuals, as distinguished from any obliga

tions of individual Negro students to either their class or

to public education generally. Of course it is true that,

as the decision below stresses at considerable length,

Brown was a class action, but the clear intent of Brown

was to confer the same personal right to all members of

the class to the attendance of a school without regard to

race—not that the class as a distinct corporate body it

self has any right which transcends and subordinates the

individual rights of its members. Subsequent decisions

of this Court have expressed the personal nature of the

right thus conferred upon individual Negroes as members

of the class. In Brown II, 349 U. S. 294, 300 (1955), it

was observed that, “ at stake is the personal interest of

plaintiffs in admission to public schools as soon as prac

ticable on a non-discriminatory basis.” In Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 19 (1958), the Court similarly spoke

of “ the right of a student not to be segregated.” No

subsequent decision has ever intimated that the individual

right is in any way limited by a theoretical right of the

class. Underscoring the individuality of the bases of its

decision is the important finding in Brown I that separa

tion of children “ solely because of their race generates

— 32 —

a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community

that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely

ever to be undone.” 347 U. S. at 494. But it did not

decide “ that there must be coerced integration of the

races in order to accomplish an educational equality, for

this also would require an appraisal of the effect upon the

hearts and minds of those who were so coerced.”40 A re

quirement of “ substantial-integration” by which the con

stitutionality of a desegregation plan is measured by the

quantitative results necessarily has the effect of trans

forming the rights of the individual students as decreed

by Brown I into an obligation to be assigned to a par

ticular school in order to accomplish educational benefits

for the class.

Secondly, an unrestricted freedom of choice plan, if

fairly and properly administered, constitutes “ a system

of determining admission to the public schools on a non-

racial basis,” which Brown II defined as the ultimate

object of the remedies to he fashioned for pupil assign

ment. 349 U. S. at 300-01.41 It also effectively eliminates

any constitutional objection, as expressed in Rogers v.

Paul, 382 U. S. 198, 199 (1965), based on the fact that

students might have been previously “ assigned to a

Negro . . . school on the basis of their race.” For under

a freedom of choice plan, their assignments are based

solely on their personal choice. Thus, the 3,348 Negro

students in the Bessemer system who have made choices

for the 1967-68 school year will be attending certain

schools not because of “ constitutionally forbidden” assign-

40 Olson v. Board of Education of Malverne, N. Y., 250 F.

Supp. 1000, 1006 (E. D. N. Y. 1966).

41 Of course, we do not mean to contend tha t there might

not be other aspects of school operations, apart from the man

ner of student assignment, for which other requirements might

be imposed in order to comply fully with Brown II. We are

speaking here solely of freedom of choice as a constitutionally

adequate method of student assignment.

— 33

ments based on race but because of their affirmative

choices. It likewise effectuates the elimination of “ dual

school systems,” since the school boards no longer main

tain a dual system based on race but a system of schools

attended by the children who select them. If the choices

made by the students result in “ disproportionate concen

trations of Negroes in certain schools,”42 there may be

a racial imbalance but on its face it is not an imbalance

caused by school officials. In requiring that a freedom

of choice method of assignment must be abandoned as

constitutionally inadequate solely because it does not

achieve certain preconceived results, the Fifth Circuit has

imposed a duty wholly different from and far exceeding

anything contemplated by the decisions of this Court.

There is not the slightest intimation in any decision of

this court that a freedom of choice method of student

assignment is not constitutionally adequate. On the con

trary, however, in the few instances in which the Court

has had occasion to consider or discuss the adequacy of

free choice plans, it has conveyed a distinct impression

that they constitute sufficient means of desegregation re

gardless of the numerical results of their operation—

an impression which has been a basis for the consistent

approval of similar plans by circuits other than the Fifth

Circuit.43 See Goss v. Board of Education of City of

Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683, 687, 689 (1963); Calhoun v. Lati

mer, 377 U. S. 263 (1964); cf. Shuttlesworth v. Birming

ham Bd. of Ed., 358 U. S. 101 (1958); Bradley v. School

City of Richmond, 382 U. S. 103 (1965).

Moreover, although the decision below requires the

adoption of another means of assignment, there was no

42 Panel Opinion, p. 6.

43 See, c. g., Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

345 F. 2d 310, 318 (4th Cir. 1965), vacated and remanded on

other grounds, 382 U. S. 103 (1965).

34 —

evidence before the court that any other method, such as

geographic zoning, would be as effective. Due to resi

dential racial isolation, it is likely that in the South as

now in the North a geographic approach will tend only to

accentuate racial concentrations in the schools.44 Indeed,

the Civil Rights Commission does not find freedom of

choice to be improper if it is properly administered.45

Finally, in the context of an unrestricted free-choice

plan, the percentage results of themselves evidence neither

the state action nor the discrimination necessary to the

assertion by the court below of authority under the Four

teenth Amendment to compel a change in the method of

assignment. Unless it be shown that the choices made by

the students are influenced in some way by school of

ficials or that they do not reflect the students’ actual

preferences, any resulting racial imbalance is due to the

students’ actions. In its conclusion that percentage results

constitute a sufficient basis for determining the constitu

tional inadequacy of a plan, the Fifth Circuit followed

the jury exclusion cases in which it has been held that

disproportions constitute presumptive evidence of pur

poseful discrimination.46 But that rule of evidence is

manifestly inapplicable in the context of a free-choice

plan since, as in the case of peremptory jury challenges,

the selection process is not “wholly in the hands of state

officers.” Swain v. Alabama, 380 IJ. S. 202, 226-28 (1965).

On the contrary, the selection process is wholly in the

hands of the children. Yet, there was absolutely no evi-

44 As observed in Rep. U. S. Comm, on Civil Rights, Racial

Isolation in the Public Schools, p. 60 (1967), “since residen

tial segregation generally is as intense in Southern and border

cities as in Northern cities, the racial composition of Southern

and border city schools substantially reflects the pattern of

residential segregation.”

45 Id., a t 66-70.