Compliance with Court Order of November 5, 1971 and Request for Hearing

Public Court Documents

December 3, 1971

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Compliance with Court Order of November 5, 1971 and Request for Hearing, 1971. 069d8192-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1512ca1a-56a7-4955-ab3c-ca2735016d73/compliance-with-court-order-of-november-5-1971-and-request-for-hearing. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

--- -

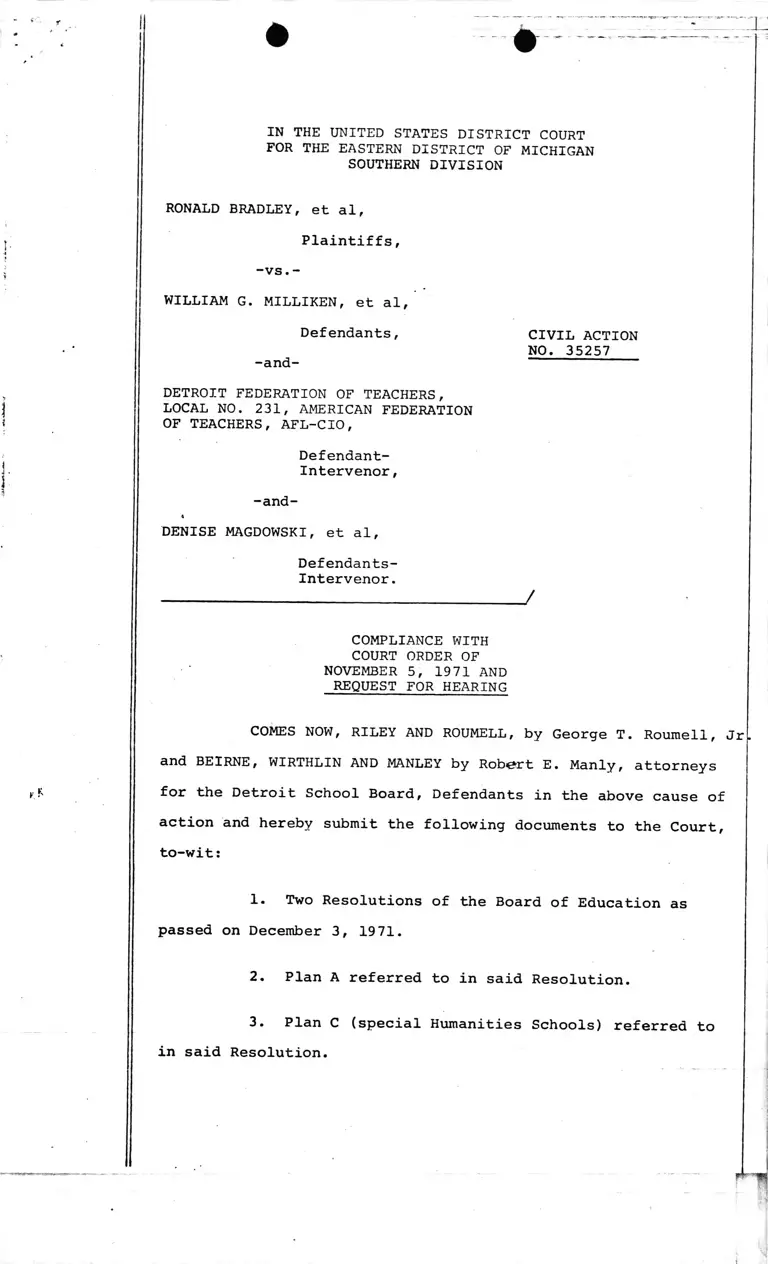

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

Plaintiffs,

- v s . -

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al,

Defendants,

-and-

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL NO. 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor,

CIVIL ACTION

NO. 35257

-and-

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al,

Defendants-

Intervenor.

------- ---------------------------------------- /

COMPLIANCE WITH

COURT ORDER OF

NOVEMBER 5, 1971 AND

REQUEST FOR HEARING

COMES NOW, RILEY AND ROUMELL, by George T. Rouraell, Jr.

and BEIRNE, WIRTHLIN AND MANLEY by Robert E. Manly, attorneys

for the Detroit School Board, Defendants in the above cause of

action and hereby submit the following documents to the Court,

to-wit:

1. Two Resolutions of the Board of Education as

passed on December 3, 1971.

2. Plan A referred to in said Resolution.

3• Plan C (special Humanities Schools) referred to

in said Resolution.

r " i i

$

Plan.

4. A statement concerning Metropolitan Desegregation

The Detroit School Board Defendants hereby requests at

a time to be set at the Court's discretion the opportunity to

present oral argument and testimony concerning the above-named

plans.

RILEY AND ROUMELL

By:

'George Ro'umell', J'r

Attorneys for Defendant -ty

The Board of Education

the School District of

the City of Detroit

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

962-8255

Dated: December 3, 1971

BEIRNE, WIRTHLIN AND MANLEY

RobertE.Manley

Attorneys for Defendant -

The Board of Education

of the School District of

the City of Detroit

3312 Carew Tower

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

CERTIFICATION OF SERVICE

STATE OF MICHIGAN)

) SS.

COUNTY OF WAYNE )

I, GEORGE T. ROUMELL, JR., hereby certify that copies

of the above Compliance with Court Order of November 5, 1971

and Request for Hearing of Detroit Board of Education Defendants

have been served on the following attorneys for the parties

in the above-entitled case by depositing same in envelopes,

postpaid first class,

-2-

in the United States Mail at Detroit, Michigan, addressed as

follows on December 3, 1971.

Louis R. Lucas, Esq.

William E. Caldwell, Esq.

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Nathaniel Jones, General Counsel

N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. Winter McCroom, Esq.

3245 Woodburn

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

Theodore Sachs, Esq.

Rothe, Marston, Mazey, Sachs,

O'Connell, Nunn & Freid

1000 Farmer Street

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Intervening Defendants

Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General

Seven Story Building

Lansing, Michigan 48902

Eugene Krasicky, Assistant Attorney

General

725 Seven Story Building

Lansing, Michigan 48902

Gerald F. Young

Assistant Attorney General

3007 Hillcrest

Lansing, Michigan 48910

Attorneys for State Defendants

Bruce Miller and Lucille

Watts

Attorneys for Legal Redress

Committee

N.A.A.C.P. - Detroit Branch

2460 First National Buildinc

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Alexander B. Ritchie, Esq.

Fenton, Nederlander, Dodge

& Barris, P.C.

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

RILEY AND ROUMELL

trict of the City of Detroit

Subscribed and sworn to before me

this^ 3rd day of December, 1971.

LINDA M. BESTENI, NOTARY PUBLIC

Wayne County, Michigan

My Commission Expires: 8-14-73

3-